#the fact that this was an adolescence-defining movie for me explains a lot about me

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

So today I was reminded that the remake of The Crow is happening, and got sad and pissed off about it. Like, I really enjoy Bill Skarsgård as an actor, but... he is not and will never be someone that I can recognize as Eric Draven.

But I shall refrain from trying to ruin other people's enjoyment of it. I refuse to carry on like those dudes who think the all-woman Ghostbusters remake ruined their entire childhoods. Even if I really want to.

The original still exists, and I can enjoy that, and marvel at how a movie released in 1994 about people who wear all black in Grimdark Detroit at night is somehow better lit that a bunch of more recent stuff. It never once becomes a blur of shapes. I can always see exactly what and where the action is, and the lighting perfectly highlights what the viewer's supposed to pay attention to, and so many filmmakers don't seem to understand that this is, in fact, important.

#the fact that this was an adolescence-defining movie for me explains a lot about me#i still love it#even though it needs so many trigger warnings#so many fucking trigger warnings#like jesus christ#it's... a lot#and there's a lot that could be said about the way the plot centers on a guy getting revenge for his fridged girlfriend#but i will forgive the crow because the original comic was literally james o'barr trying to cope with his wife's death#the man fucking opened a vein and bled onto the page#it wasn't fridging a character so the protagonist could get cool manpain#the pain was real#and i've gotta respect that

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Utopia and Apocalypse: Pynchon’s Populist/Fatalist Cinema

The rhythmic clapping resonates inside these walls, which are hard and glossy as coal: Come-on! Start-the-show! Come-on! Start-the-show! The screen is a dim page spread before us, white and silent. The film has broken, or a projector bulb has burned out. It was difficult even for us, old fans who’ve always been at the movies (haven’t we?) to tell which before the darkness swept in.

--from the last page of Gravity’s Rainbow

To begin with a personal anecdote: Writing my first book (to be published) in the late 1970s, an experimental autobiography titled Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (Harper & Row, 1980), published in French as Mouvements: Une vie au cinéma (P.O.L, 2003), I wanted to include four texts by other authors—two short stories (“In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” by Delmore Schwartz, “The Secret Integration” by Thomas Pynchon) and two essays (“The Carole Lombard in Macy’s Window” by Charles Eckert, “My Life With Kong” by Elliott Stein)—but was prevented from doing so by my editor, who argued that because the book was mine, texts by other authors didn’t belong there. My motives were both pluralistic and populist: a desire both to respect fiction and non-fiction as equal creative partners and to insist that the book was about more than just myself and my own life. Because my book was largely about the creative roles played by the fictions of cinema on the non-fictions of personal lives, the anti-elitist nature of cinema played a crucial part in these transactions.`

In the case of Pynchon’s 1964 story—which twenty years later, in his collection Slow Learner, he would admit was the only early story of his that he still liked—the cinematic relevance to Moving Places could be found in a single fleeting but resonant detail: the momentary bonding of a little white boy named Tim Santora with a black, homeless, alcoholic jazz musician named Carl McAfee in a hotel room when they discover that they’ve both seen Blood Alley (1955), an anticommunist action-adventure with John Wayne and Lauren Bacall, directed by William Wellman. Pynchon mentions only the film’s title, but the complex synergy of this passing moment of mutual recognition between two of its dissimilar viewers represented for me an epiphany, in part because of the irony of such casual camaraderie occurring in relation to a routine example of Manichean Cold War mythology. Moreover, as a right-wing cinematic touchstone, Blood Alley is dialectically complemented in the same story by Tim and his friends categorizing their rebellious schoolboy pranks as Operation Spartacus, inspired by the left-wing Spartacus (1960) of Kirk Douglas, Dalton Trumbo, and Stanley Kubrick.

For better and for worse, all of Pynchon’s fiction partakes of this populism by customarily defining cinema as the cultural air that everyone breathes, or at least the river in which everyone swims and bathes. This is equally apparent in the only Pynchon novel that qualifies as hackwork, Inherent Vice (2009), and the fact that Paul Thomas Anderson’s adaptation of it is also his worst film to date—a hippie remake of Chinatown in the same way that the novel is a hippie remake of Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald—seems logical insofar as it seems to have been written with an eye towards selling the screen rights. As Geoffrey O’Brien observed (while defending this indefensible book and film) in the New York Review of Books (January 3, 2015), “Perhaps the novel really was crying out for such a cinematic transformation, for in its pages people watch movies, remember them, compare events in the ‘real world’ to their plots, re-experience their soundtracks as auditory hallucinations, even work their technical components (the lighting style of cinematographer James Wong Howe, for instance) into aspects of complex conspiratorial schemes.” (Despite a few glancing virtues, such as Josh Brolin’s Nixonesque performance as "Bigfoot" Bjornsen, Anderson’s film seems just as cynical as its source and infused with the same sort of misplaced would-be nostalgia for the counterculture of the late 60s and early 70s, pitched to a generation that didn’t experience it, as Bertolucci’s Innocents: The Dreamers.)

From The Crying of Lot 49’s evocation of an orgasm in cinematic terms (“She awoke at last to find herself getting laid; she’d come in on a sexual crescendo in progress, like a cut to a scene where the camera’s already moving”) to the magical-surreal guest star appearance of Mickey Rooney in wartime Europe in Gravity’s Rainbow, cinema is invariably a form of lingua franca in Pynchon’s fiction, an expedient form of shorthand, calling up common experiences that seem light years away from the sectarianism of the politique des auteurs. This explains why his novels set in mid-20th century, such as the two just cited, when cinema was still a common currency cutting across classes, age groups, and diverse levels of education, tend to have the greatest number of movie references. In Gravity’s Rainbow—set mostly in war-torn Europe, with a few flashbacks to the east coast U.S. and flash-forwards to the contemporary west coast—this even includes such anachronistic pop ephemera as the 1949 serial King of the Rocket Men and the 1955 Western The Return of Jack Slade (which a character named Waxwing Blodgett is said to have seen at U.S. Army bases during World War 2 no less than twenty-seven times), along with various comic books.

Significantly, “The Secret Integration”, a title evoking both conspiracy and countercultural utopia, is set in the same cozy suburban neighborhood in the Berkshires from which Tyrone Slothrop, the wartime hero or antihero of Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), aka “Rocketman,” springs, with his kid brother and father among the story’s characters. It’s also the same region where Pynchon himself grew up. And Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon’s magnum opus and richest work, is by all measures the most film-drenched of his novels in its design as well as its details—so much so that even its blocks of text are separated typographically by what resemble sprocket holes. Unlike, say, Vineland (1990), where cinema figures mostly in terms of imaginary TV reruns (e.g., Woody Allen in Young Kissinger) and diverse cultural appropriations (e.g., a Noir Center shopping mall), or the post-cinematic adventures in cyberspace found in the noirish (and far superior) east-coast companion volume to Inherent Vice, Bleeding Edge (2013), cinema in Gravity’s Rainbow is basically a theatrical event with a social impact, where Fritz Lang’s invention of the rocket countdown as a suspense device (in the 1929 Frau im mond) and the separate “frames” of a rocket’s trajectory are equally relevant and operative factors. There are also passing references to Lang’s Der müde Tod, Die Nibelungen, Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, and Metropolis—not to mention De Mille’s Cleopatra, Dumbo, Freaks, Son of Frankenstein, White Zombie, at least two Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals, Pabst, and Lubitsch—and the epigraphs introducing the novel’s second and third sections (“You will have the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood — Merian C. Cooper to Fay Wray” and ���Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas any more…. –Dorothy, arriving in Oz”) are equally steeped in familiar movie mythology.

These are all populist allusions, yet the bane of populism as a rightwing curse is another near-constant in Pynchon’s work. The same ambivalence can be felt in the novel’s last two words, “Now everybody—“, at once frightening and comforting in its immediacy and universality. With the possible exception of Mason & Dixon (1997), every Pynchon novel over the past three decades—Vineland, Against the Day (2006), Inherent Vice, and Bleeding Edge—has an attractive, prominent, and sympathetic female character betraying or at least acting against her leftist roots and/or principles by being first drawn erotically towards and then being seduced by a fascistic male. In Bleeding Edge, this even happens to the novel’s earthy protagonist, the middle-aged detective Maxine Tarnow. Given the teasing amount of autobiographical concealment and revelation Pynchon carries on with his public while rigorously avoiding the press, it is tempting to see this recurring theme as a personal obsession grounded in some private psychic wound, and one that points to sadder-but-wiser challenges brought by Pynchon to his own populism, eventually reflecting a certain cynicism about human behavior. It also calls to mind some of the reflections of Luc Moullet (in “Sainte Janet,” Cahiers du cinéma no. 86, août 1958) aroused by Howard Hughes’ and Josef von Sternberg’s Jet Pilot and (more incidentally) by Ayn Rand’s and King Vidor’s The Fountainhead whereby “erotic verve” is tied to a contempt for collectivity—implicitly suggesting that rightwing art may be sexier than leftwing art, especially if the sexual delirium in question has some of the adolescent energy found in, for example, Hughes, Sternberg, Rand, Vidor, Kubrick, Tashlin, Jerry Lewis, and, yes, Pynchon.

One of the most impressive things about Pynchon’s fiction is the way in which it often represents the narrative shapes of individual novels in explicit visual terms. V, his first novel, has two heroes and narrative lines that converge at the bottom point of a V; Gravity’s Rainbow, his second—a V2 in more ways than one—unfolds across an epic skyscape like a rocket’s (linear) ascent and its (scattered) descent; Vineland offers a narrative tangle of lives to rhyme with its crisscrossing vines, and the curving ampersand in the middle of Mason & Dixon suggests another form of digressive tangle between its two male leads; Against the Day, which opens with a balloon flight, seems to follow the curving shape and rotation of the planet.

This compulsive patterning suggests that the sprocket-hole design in Gravity’s Rainbow’s section breaks is more than just a decorative detail. The recurrence of sprockets and film frames carries metaphorical resonance in the novel’s action, so that Franz Pökler, a German rocket engineer allowed by his superiors to see his long-lost daughter (whom he calls his “movie child” because she was conceived the night he and her mother saw a porn film) only once a year, at a children’s village called Zwölfkinder, and can’t even be sure if it’s the same girl each time:

So it has gone for the six years since. A daughter a year, each one about a year older, each time taking up nearly from scratch. The only continuity has been her name, and Zwölfkinder, and Pökler’s love—love something like the persistence of vision, for They have used it to create for him the moving image of a daughter, flashing him only these summertime frames of her, leaving it to him to build the illusion of a single child—what would the time scale matter, a 24th of a second or a year (no more, the engineer thought, than in a wind tunnel, or an oscillograph whose turning drum you can speed or slow at will…)?

***

Cinema, in short, is both delightful and sinister—a utopian dream and an apocalyptic nightmare, a stark juxtaposition reflected in the abrupt shift in the earlier Pynchon passage quoted at the beginning of this essay from present tense to past tense, and from third person to first person. Much the same could be said about the various displacements experienced while moving from the positive to the negative consequences of populism.

Pynchon’s allegiance to the irreverent vulgarity of kazoos sounding like farts and concomitant Spike Jones parodies seems wholly in keeping with his disdain for David Raksin and Johnny Mercer’s popular song “Laura” and what he perceives as the snobbish elitism of the Preminger film it derives from, as expressed in his passionate liner notes to the CD compilation “Spiked!: The Music of Spike Jones” a half-century later:

The song had been featured in the 1945 movie of the same name, supposed to evoke the hotsy-totsy social life where all these sophisticated New York City folks had time for faces in the misty light and so forth, not to mention expensive outfits, fancy interiors,witty repartee—a world of pseudos as inviting to…class hostility as fish in a barrel, including a presumed audience fatally unhip enough to still believe in the old prewar fantasies, though surely it was already too late for that, Tin Pan Alley wisdom about life had not stood a chance under the realities of global war, too many people by then knew better.

Consequently, neither art cinema nor auteur cinema figures much in Pynchon’s otherwise hefty lexicon of film culture, aside from a jokey mention of a Bengt Ekerot/Maria Casares Film Festival (actors playing Death in The Seventh Seal and Orphée) held in Los Angeles—and significantly, even the “underground”, 16-millimeter radical political filmmaking in northern California charted in Vineland becomes emblematic of the perceived failure of the 60s counterculture as a whole. This also helps to account for why the paranoia and solipsism found in Jacques Rivette’s Paris nous appartient and Out 1, perhaps the closest equivalents to Pynchon’s own notions of mass conspiracy juxtaposed with solitary despair, are never mentioned in his writing, and the films that are referenced belong almost exclusively to the commercial mainstream, unlike the examples of painting, music, and literature, such as the surrealist painting of Remedios Varo described in detail at the beginning of The Crying of Lot 49, the importance of Ornette Coleman in V and Anton Webern in Gravity’s Rainbow, or the visible impact of both Jorge Luis Borges and William S. Burroughs on the latter novel. (1) And much of the novel’s supply of movie folklore—e.g., the fatal ambushing of John Dillinger while leaving Chicago’s Biograph theater--is mainstream as well.

Nevertheless, one can find a fairly precise philosophical and metaphysical description of these aforementioned Rivette films in Gravity’s Rainbow: “If there is something comforting -- religious, if you want — about paranoia, there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long.” And the white, empty movie screen that appears apocalyptically on the novel’s final page—as white and as blank as the fusion of all the colors in a rainbow—also appears in Rivette’s first feature when a 16-millimeter print of Lang’s Metropolis breaks during the projection of the Tower of Babel sequence.

Is such a physically and metaphysically similar affective climax of a halted film projection foretelling an apocalypse a mere coincidence? It’s impossible to know whether Pynchon might have seen Paris nous appartient during its brief New York run in the early 60s. But even if he hadn’t (or still hasn’t), a bitter sense of betrayed utopian possibilities in that film, in Out 1, and in most of his fiction is hard to overlook. Old fans who’ve always been at the movies (haven’t we?) don’t like to be woken from their dreams.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Footnote

For this reason, among others, I’m skeptical about accepting the hypothesis of the otherwise reliable Pynchon critic Richard Poirier that Gravity’s Rainbow’s enigmatic references to “the Kenosha Kid” might allude to Orson Welles, who was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Steven C. Weisenburger, in A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion (Athens/London: The University of Georgia Press, 2006), reports more plausibly that “the Kenosha Kid” was a pulp magazine character created by Forbes Parkhill in Western stories published from the 1920s through the 1940s. Once again, Pynchon’s populism trumps—i.e. exceeds—his cinephilia.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review #1 | Carry On by Rainbow Rowell

“Half the time, Simon can’t even make his wand work, and the other half, he sets something on fire. His mentor’s avoiding him, his girlfriend broke up with him, and there’s a magic-eating monster running around wearing Simon’s face. Baz would be having a field day with all this, if he were here—it’s their last year at the Watford School of Magicks, and Simon’s infuriating nemesis didn’t even bother to show up.” [official synopsis of the book]

Full title: “Carry On: The rise and Fall of Simon Snow.”

Or, as I often refer to it, the death of me.

I can already hear my friend A. complaining that I read this book at least twice a year – which is odd, I get it, but I also can't help it. She says that I'm obsessed with it...

... She’s right. But there's a reason if the motto of my brand new blog is "H for Honesty", so I promise that I won't let my obsession take over the review. Scout's honor!

Anyway, we have to straighten some things out before we settle down to work, since I know that there are people out there who are not appealed by this book because of its similiarities with the Harry Potter Saga.

The Chosen One and the prophecy themes, the analogies between characters such as Penelope Bunch and Hermione Granger, the Drarry vibes, the English school of magic...

So if you want to complain about these similiarities, then stop reading, watching tv shows and movies or even breathing because, guess what?, it's literally impossible not to be influenced by others, especially if you are a writer.

I think that inspiration is good; it means that you've reached the heart of your readers and left a permanent mark on it. As a wanna-be writer I can only aspire to do such a great thing as inspiring someone to the point that they want to share their own stories.

Speaking of Rainbow Rowell being inspired by Jk Rowling, well, it doesn't mean that she plagiarised her work – far from it. Rainbow's World of Mages is something fresh, modern, unexplored. It has cliches just like any other great story, but instead of running in circles it goes beyond them.

This is why the first character I want to introduce is Agatha Wellbelove, who’s supposed to play the role of the protagonist’s love interest. I’m gonna be honest with you guys – I didin’t like her at first, like not at all.

It’s hard to explain without spoiling the book but I’ll try my best, alright?

Agatha is the only daughter of one of the richest and most important families of the world of mages. Her father is a doctor and her mother is very invested in the social part of their community, hence the charity works such as having poor, orphan Simon stay at their house during Christmas break.

Beautiful, popular, kind. She had to be all these things for her whole life because everything had already been set up for her. Even her relationship with Simon was inevitable. I know it’s silly but think of Shrek: like Fiona, she had to play the role of the damsel in distress locked in the highest tower of the castle, awaiting for her knight in his shiny armour... only to be his reward at the end of the story, when the magical war is over... if he manages to survive.

But Agatha is more than that.

“Lucy disappeared?” I say.

“Worse,” Mum says. “She ran away. From magic. Can you imagine?”

“Yes,” I say, then, “no.”

She wants to spend time with her normal friends, go to a normal school, be a normal person without the burden of magic on her shoulders. But she can’t, of course, because everyone would think that she’s insane, so she’s stuck in a world where she doesn’t belong.

Magic is a religion.

But there’s no such thing as not believing – or only going through the motions on Easter and Christmas. Your whole life has to revolve around magic all the time. If you’re born with magic, you’re stuck with it, and you’re stuck with other magicians, and you’re stuck with wars that never end because people don’t even know when they started.

I honestly didn’t understand her character at first, because c’mon, if someone came to me and told me that I could attend Hogwarts/Watford and have magical powers if I wanted, I wouldn’t even hesitate to answer hell, yeah. But this is another matter, ofc.

The point is that Rainbow Rowell’s characters are what I’d like (and dare) to define «the apotheosis of relatability». They are not just fictional characters. When they think, when they talk, when they act... they seem extremely human in my head, they seem to bloody exist, as if they weren’t made of paper...

I think that this effect is mostly due the fact that the book was written in first person singular. Yeah, I know that most people avoid this type of point of view like the plague, but believe me when I say that Carry on is 100% worth it.

Every chapter mirrors the thoughts of the main characters, from Simon’s to the Mage’s, and is shaped by them. For instance:

When Simon is talking, his words are articulated in short and/or mostly broken sentences.

He doesn’t reply – he must still be working up to a bluster.

Snow blusters like no one else. But! I mean! Um! It’s just! It’s no wonder he can never spit out a spell.

When he’s thinking, the pages are filled with long and elaborated phrases, which can be seen especially in the first chapters of the book;

Baz, on the other hand, has the opposite problem. He comes up with the most complex sentences when he’s speaking, while his thoughts are often interrupted by the use of round brakets, which is undoubtedly of my favourite features of his chapters.

So even though he seems this cool and charming and extremely confident and super duper talented and handsome magician, this is just his façade. In reality, he’s the type of guy who would rather be alone during meals because he’s too self-conscious and doesn’t want his family to see the fangs that come through when he’s eating.

It’s no secret that Baz is very secretive when it comes to his feelings or anything that concerns his private sphere, as he always weighs his words before he speaks up. But when the crosstalk is between him and Simon, there’s literally nothing in the world that Baz loves more than teasing him.

“I know what you are,” I snarled.

His eyes locked onto mine. “Your roommate?”

I shook my head and squeezed the hilt of my sword.

Baz stepped into my reach. “Tell me,” he spat.

I couldn’t.

“Tell me, Snow.” He stepped even closer. “What am I?”

I growled again and raised the blade an inch. “Vampire! I shouted. He must have felt the force of my breath on his face.

He started giggling. “Really? You think I’m a vampire? Well, Aleister Crowley, what are you going to do about that?”

I love the dynamics between Baz and Simon because their relationship is so genuine and thriving, absolutely compelling. You can see the deep impact that they have on each other from page one. Yes, they are roommates (oh my god, they are roommates), but they are enemies too, so they don’t really know how to deal with each other beyond their rivalry, especially when they have to team up against a common enemy.

These dynamics are way funnier when you consider that they concern a third character too. Yes, this is the moment I introduce you to the person that was recently hospitalized due to severe back pains caused by the burden of carrying Simon Snow’s bullshit on her shoulders from day one: Penelope Bunce.

She told me later that her parents had told her to steer clear of me at school. “My mum said that nobody really knew where you came from. And that you might be dangerous.”

“Why didn’t you listen to her?” I asked.

“Because nobody knew where you came from, Simon! And you might be dangerous!”

“You have the worst survival instincts.”

“Also, I felt sorry for you,” she said. “You were holding your hand backwards.”

As you can see, I love Penny. She’s clever, she’s talented, she’s this amazing young woman who is not afraid to walk with you toward eternal damnation or help you hide a corpse or do both at the same time. Because she’s all that – and more than that. She’s everything.

Penny is the kind of person who, right after you say that “curiosity killed the cat”, would rejoin that “satisfaction brought it back”. She is exactly the character that I needed as a role model during both my childhood and my adolescence: stubborn, curious, terribly ambitious... For some time I had been convinced that these were negative traits, but it’s mostly thanks to Penny that I’ve started to realise that they are good qualities instead.

I see a lot of myself in Penelope, and I could never thank Rainbow Rowell enough for creating her characters.

I could never thank Rainbow enough for writing about this amazing world and sharing it with us. And I will never stop thanking her for deciding to give us a sequel, Wayward son.

In the meanwhile, thank you. Yes, you: the person reading this review. I hope you enjoyed it! If so, follow me for new pieces :)

With love,

M.C.

P.S. I apologise for the inappropriate use of the editor but it appears that tumblr hates me.

P.P.S. My friend A. says hi – and wants you to know that the only reason she can stand the Mage is because his name is David... you know, like David Dobrik. I can’t even.

#carryon#carry on#simon snow#baz pitch#rainbow rowell#rainbowrowell#world of mages#waywardson#penny bunce#the mage#magic#review#spoiler free#snowbaz#chosen one#fantasy#lgbtq#drarry#harry potter#hogwarts

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blue, the Warmest Color? Or the Most Profitable Color?

youtube

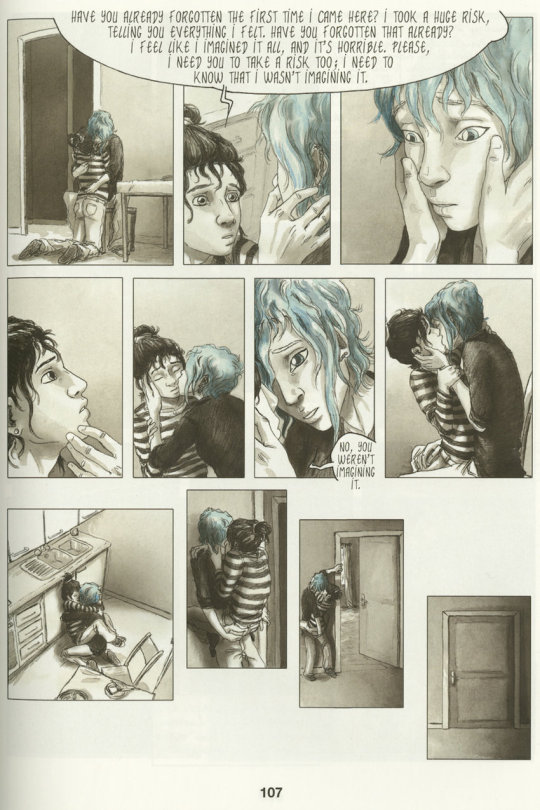

Blue Is the Warmest Color is a 2013 French movie directed by Abdellatif Kechiche, which won a lot of rewards including the Palme d'Or and the FIPRESCI Prize. This is a three-hour film about the romance story of a 15-year-old high school girl, Adèle (starring Adèle Exarchopoulos) and a female artist Emma (starring Léa Seydoux). The entire story depicts carefully about Adèle’s growth from adolescence to middle age, accompanied by confusion and struggle for her sexual identity.

At the beginning of this story, Adèle was dating a boy, Thomas. Once they were dating, Adèle passed by a blue-haired girl when crossing the road. After this encounter, Adèle woke up in a dream about making love with this girl. She was confused and embarrassed by this fantasy. When her best friend Valentin, an openly gay man found her unhappy, he took her to a gay bar for fun. But later, Adèle came out and entered a lesbian bar by chance, where she met (again) and started getting to know the blue-haired girl, Emma. Adèle and Emma became friends and hung out with each other frequently. And their romance relationship confirmed by a shared kiss when picnic. A few years later, Adèle realized her dream to become a primary school teacher; Emma was preparing her art exhibition, and their relationship was not passionate like it used to be. Adèle had a sexual relationship with her male colleague Antoine because of Emma’s indifference. After this was known by Emma, she drove Adèle out of the home immediately and refused her apology. Although Adèle expressed her love for Emma again a few years later, could not recover the relationship. And Emma had formed a new family with her first love, Lise.

At the end of the film, when Adèle attended Emma’s art exhibition and saw many portraits of her own, she chose to leave quickly, which also marked the complete end of this relationship. In general, this film records the whole story of Adèle and Emma in a very delicate way, trying to present the audience with true lesbian life detail. And the goal of making the audience get involved in the real-life of the LGBTQIA community can contribute to the sympathy and understanding of them to a certain extent, which is conducive to the diversity of the media. But I critic that this film is still unable to break away from the use of lesbian love as the strategy “for creating ‘edgy’ programming and attracting a wide range of viewers” (Kohnen, 2015). And many descriptions in this film deepen the audience’s misunderstanding of the lesbian group.

Firstly, this film does a great job of recording Adèle’s life detail. For example, she always has a messy hair, she will open her mouth when sleeping, and she loves biting the bottom of the pen when she reads. When she gets lost or drunk, the film’s scene will shake and be a blur, just as seen from Adèle’s perspective. When she in the literature class, the shots keep switching to the teacher’s lecture and the students’ distraction because of the boring content. As a viewer, I can also feel that this content was very boring. The film recorded all these tiny details by using this first-person perspective technique to make Adèle just like a friend in our own life, or actually, she is ourselves. I believe to depict a character on a very personal level is a great strategy to promote the audience’s understanding. And this method also mentioned in the Goltz’s article for finding an effective term to refers to gay or lesbian in Kenyan language context, that one man focus on “there was more to him than his sexuality and that he was ‘beyond being homosexual or being a gay man’ ” and “ ‘to come out as me and not to highlight his sexuality, preferring to ‘talk about me, about my life, not about my queer life” (Goltz et al, 2016).

The tricky thing is that even though this film wants to show the real-life of lesbian, it almost becomes the most controversial lesbian movie because of the ten-minute (or even longer) lesbian sex scene. In fact, I was super embarrassed when I watch this scene because I invited all my roommates to watch this film together as a celebration of the weekend. I am not an extremely conservative person, I mean, the sex scene in this film is simply porn-level, so that we had to turn down the volume and made some jokes to cover up our embarrassment. Firstly, there was no background music in this scene, only big gasps instead and the sound of skin rubbing. Secondly, the scene boldly shows female whole body, without cover. In addition, the two actresses are very good in shape, without flaw or even pubic hair. This is the most confusing place for me. On the one hand, the director wants to present the most authentic lesbian life, which even refuses the background music at the sex scene; on the other hand, it idealizes the female body just as the male gaze, the flawless body, and the perfect shape.

Interestingly, the original author of this story, Julie Maroh expressed the same shock as me. She rated the most lacking in this film is lesbian, and aired her suspicion that there were no lesbians present onset (Romney, 2013). And “a brutal and surgical display, exuberant and cold, of so-called lesbian sex, which turned into porn” (Sciolino, 2013). Maroh replied in the interview, “everyone was giggling. Heterosexuals laugh at because they don’t understand it and find the scene ridiculous. The gay and queer people laughed because it’s not convincing, and find it ridiculous; and among the only people (who) we didn’t hear giggling were guys too busy feasting their eyes on an incarnation of their fantasies on screen” (Sciolino, 2013). When I learned that the director and both two actresses are straight, this makes more sense.

Director Kechiche labels himself as an unconditional devotee of realism. “I don’t want it to look like life,” he says of his cinema. “I want it to actually be life. Real moments of life, that's what I’m after” (Romney, 2013). But at the same time, he also admitted that his purpose is to idealize the female body (Sciolino, 2013). He explained, “Like paintings, or sculptures” (Romney, 2013). Ms. Seydoux counters the Kechiche’s use of the so-called real lesbian sex scene as an eyebrow-raising directly. When the reporter used “several unsimulated sex scenes” to ask Ms. Seydoux, she interrupted immediately, “Be careful, they are simulated. We were wearing prostheses” (Sciolino, 2013). Ms. Exarchopoulos used the word manipulation to describe the director's guidance for them. For both actresses, the filming process was horrible and indicated that they would no longer work with Kechiche (Stern, 2013).

(Léa Seydoux, Adèle Exarchopoulos, and Abdellatif Kechiche won the Palme d'Or.)

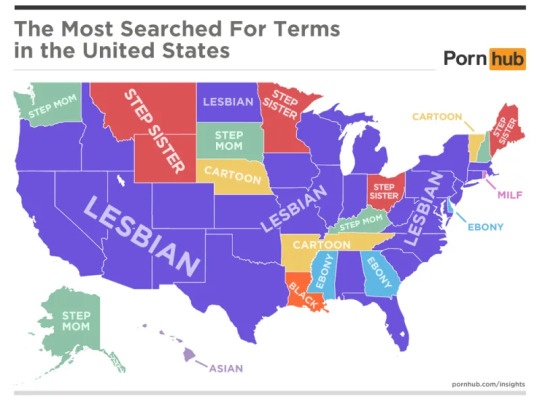

It can be said that this film is successful in regards to cultural diversity as brand management. This movie has received a high honor, people should know it is the first film to have the Palme d'Or awarded to both the director and the (two) lead actresses (RFI, 2013). Not only that, but the film also performed not bad at the box office. It can be said that this is a work that has gained a good reputation and attracted the audience through brand management of cultural diversity. But as Kohnen mentioned, “the strategic use of LGBTQ content to signify edginess has not disappeared” (2015). Lesbian movies, especially those including so-called real lesbian sex scenes, are not only targeting the group that supports LGBTQIA and cultural diversity but also a straight (especially male) group who wants to satisfy their own sexual fantasies. Although shocked, it is important to know that Lesbian has been the most popular porn search term for porn sites (Lufkin, 2016).

So I have been thinking about whether lesbian movies are the most cost-effective thing. Due to the brand management of cultural diversity, LGBTQIA films can gain a good social reputation, because more or less they are showing/facilitating the spread of cultural diversity. On the other hand, this type of film caters to the Queer Market, as we mentioned the homonormativity, “depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption” (Duggan, 2002). In addition, a large number of heterosexual groups who want to satisfy their sexual fantasies/curiousness are attracted to the cinema.

The toughest point is that, as mentioned above, the director's purpose is to idealize the female body. And the two actresses clarified their heterosexual identity immediately after the processing of the film. Everyone has made a profit from this lesbian-themed film, but everyone is trying to getting rid of any suspicious of homosexuality identity after making a profit.

As an Asian (I used to believe myself as) straight woman, I have to admit that this film started to make me doubt my own sexual orientation. When I was watching this film, I would involuntarily introduce myself to Adèle’s role, and I found Emma to be a very charming woman. In the film, Emma's hair is blue in the first half and light brown in the second half of the film. The blue hair period is the sweetest time for her and Adèle. I think that Emma was really attractive at that time. And the second half with the light brown hair is the period that her relationship with Adèle is about to burst. I think this is why the film's name is Blue Is The Warmest Color. In fact, in the original comics, all the scenes are black and white, except that Emma's hair is blue, and the intuitive contrast that comic can present can more express this theme.

I have always lived in a heterosexual culture community. The heteronormative in Asian culture is more ingrained than Western culture, so I never thought about my sexual orientation. It’s like I also cannot figure out the sexual orientation of Adèle. She did not show any love for women other than Emma, and she had an affair with a man, not a woman. By watching this film, I am rethinking whether it is a wise choice to define sexual orientation based on gender. I love a person because of the gender of that person, or because that person is that person.

In general, I would think this film is a good movie, especially from the contribution that made me rethink my own identity. But when I know more about the story behind this film, the harder it is for me to evaluate it from the work itself. Everything became complicated when lesbian-themed movies/televisions connect with cultural diversity brand management, homonormativity, Queer Market, and even male sexual fantasy.

Reference:

Duggan, L. (2002). Equality, Inc. The Twilight of Equality? (PP. 43-66). Beacon Press, Boston.

Goltz, D. B., Zingsheim, J., Mastin, T., & Murphy, A. G. (2016). Discursive negotiations of Kenyan LGBTI identities: Cautions in cultural humility. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 9(2).

Kohnen, M. (2015). Cultural Diversity as Brand Management in Cable Television. Media Industries Journal, 2(2).

Lufkin, B. (2016). The Most Popular Porn Searches in Every State. Gizmodo.

RFI. (2013). Blue is the warmest color team win Palme d'Or at Cannes 2013. archive.org. https://web.archive.org/web/20130608102433/http://www.english.rfi.fr/culture/20130526-wins-palme-dor-cannes-2013

Romney, J. (2013). Abdellatif Kechiche interview: 'Do I need to be a woman to talk about love between women?'. the Guardian.

Sciolino, E. (2013). Darling of Cannes Now at Center of Storm. Nytimes.com.

Stern, M. (2013). The Stars of ‘Blue is the Warmest Color’ On the Riveting Lesbian Love Story. The Daily Beast.

#blue is the warmest color#queer media studies#QueerMovieAnalysis#léa seydoux#adèle exarchopoulos#abdellatif kechiche

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mental Health Awareness Week: My Story

Hi to anyone who’s reading this!

My name is Lauren and this is my first personal post on my Tumblr (which I’m using because I am a granny who can’t be arsed to work out the basics of Wordpress). My intention in making this blog was ultimately to talk about mental health and fashion and things that interest me and I suppose I knew that ultimately I was going to make a post like this but I just didn’t realise it would be so soon. But then Theresa May lit up Downing Street and it was Mental Health Awareness week and Borderline Personality Disorder Awareness month and I realised, best to just get this out of the way before I can start making excuses to put it off until the end of time. It’s a hard post to make because I don’t exactly know who the audience will be; I’m writing it for the mental health community and anybody who’s interested in what Borderline Personality Disorder is/looks like but I’m also conscious of the fact that one day my family and friends and even potential employers could be reading this. How much detail am I supposed to go into? A lot of people still feel uncomfortable discussing topics like this; they start seeing you a different way when they know you suffer from a mental illness, even though you’re the same person you’ve always been. It’s also hard to know where to start when I’m talking about my mental health. I feel like other posts of a similar nature tend to have a clear start, beginning, and end. A clear cause or inciting incident, one self-explanatory, well-understood diagnosis, and a clear pathway to recovery. I don’t have a single, defining trauma I can pinpoint anything to, and I don’t think I have complex PTSD (which is often conflated with BPD but as I understand it, not always the same thing). I have a family history of mental illness and a series of less significant events that in hindsight might have affected me more than I originally thought, but until I became able to think about concepts such as “mental health” and self-image and relationships in the abstract, I believed that I generally had a pretty happy childhood. My family did their very best and they loved me and we always had a roof over our heads and food on our plates. When I did start to conceptualise my mental health, I kind of thought of it as a wave of depression and insecurities and anxieties that hit me when I was in my early teens. I think this is the same for a lot of people. Only when I got a diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder (which I will shorten to BPD for the purpose of making this easier to read, lol!) in October 2018 did I question that.

I’ve done a lot of questioning since I got the diagnosis, the same kind of questions that make this post hard to write. Am I really that ill? Am I not just being dramatic? Do I have any right to feel like this given the privilege I have? When in reality, this deep-rooted gut instinct to doubt who you are and what you have a right to feel is an intrinsic part of BPD.

There are 9 key symptoms involved in the disorder, 5 of which must be experienced to a degree that is severe enough to affect your day to day functioning in order to receive a diagnosis. My formal assessment which took place during my stay at an inpatient psychiatric ward in October 2018 revealed I was just on the cusp of receiving a diagnosis; in 5 of the 9 categories I scored highly enough that the symptom was impairing my ability to function, thus I only just qualified (lucky me!). That’s what mental illness is really, a collection of ingrained and/or inherited behaviours that are inhibiting one’s day to day life. With regards to BPD, these 9 behaviours or symptoms are as follows:

1. Fear of abandonment (check).

2. Unstable relationships.

3. Unclear or shifting self-image (check).

4. Impulsive, self-destructive behaviours (check).

5. Self-harm (check).

6. Extreme emotional swings (check).

7. Explosive anger.

8. Dissociative experiences (check).

9. Chronic feelings of emptiness (check, check, CHECK).

See, when the diagnosis was first suggested to me informally by a community mental health nurse in June of 2018, I was a bit like…what?! That can’t be me! I don’t have outbursts (it’s okay if you do and you’re working on it)! I don’t scream and throw things (again, okay if you do and are working on it)! And I’m definitely not manipulative (any person can be manipulative so I don’t even know where this one comes from)! That was, like, all I knew about BPD. Stereotypes. Think Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction type bullshit, we’re talking the woman that coined the phrase bunny boiler. I didn’t know that BPD can present in a million different ways, based on the person who’s suffering with it, because I thought BPD was the person. The widespread consensus on BPD isn’t the most humanising. So I hope me explaining how it’s affected my life and the way its presented itself over the years helps in turning the tide, which so many amazing people have already begun to do by sharing their stories. My aim is to do the same.

I’ve had a lot of time to think about the areas in which BPD has affected my life since my formal assessment, in which I felt I learnt a lot more about the disorder. In particular, the idea that I was always this happy child that got hit by a wave of inexplicable, crippling depression once I hit my teenage years. I remember during the assessment, the doctor asking me to talk about my early relationships and it kind of struck me at that moment that I’d been going through this pattern of switching between extreme attachment towards versus extreme devaluation of my relationships with the closest people in my life for as long as I could remember. My first real best friend of several years basically stopped speaking to me (and in hindsight, I do not blame her, lmao!) when we were about 12 because I can only imagine she was sick of me either picking a fight or desperately seeking her reassurance every time she dared to hang out with another friend. I remembered how it felt when she did choose to spend time with somebody else rather than me: “oh my god, she likes them more, she finds me boring, she hates me and she doesn’t want to be friends with me anymore! Everything’s over! I’ll never find anyone who loves me like she does because why would they? I can’t go on with my life until I know that she isn’t going to leave me!”. I think at that age, everyone has that shrill inner voice that doesn’t exactly consider logic or react in the most sensible way, but instead of my shrill inner voice going away, it just faded to more of a constantly niggling monotone that continued to affect the way I behaved around other people for years to come. This was just one of the signs that things weren’t as they should be from an early age. I think I was around 13 when the Child Adolescent Mental Health Services (otherwise known as the dreaded CAMHS), whom my parents had initially got me referred to for sleeping problems, diagnosed me with generalised anxiety and social phobia. Social phobia, despite this being its DSM name, is more commonly known as social anxiety. This came about after I had undergone successful CBT for said sleeping problems and thought I’d just drop it in, as you do, that basically, every social interaction felt like I was putting on a desperate show to keep the few remaining people left in the theatre from walking out. I told them that school was emotionally exhausting me. Whilst after the first couple of rocky years of transitioning from primary to secondary school I had developed a close group of friends, I still felt like aside from the closet few of them, absolutely nobody liked me. That was definitely true of some people, but likely not to the extent I envisioned it. I had come to feel, I suspect due to a combination of genes and a few environmental factors, like I was inherently unloveable and annoying, and even though I’m in a good place right now, these are things I continue to struggle with. When you’ve believed these things for so long, to act according to them is second nature.

The thing about BPD is that it’s hard to determine what is a co-morbidity and what is part of The Disorder™. I’m still not quite sure whether my social anxiety was in and of its own issue or if it was driven by the borderline symptom of fearing abandonment. Even recently, during a period of relative stability, I went back to my GP about dysmorphic thoughts concerning my body and appearance as I believe they go beyond the threshold of what is to be expected as part the unstable self-image facet of BPD. Whilst I can accept, for example, that the self-harming and binge eating I began indulging in around the same time I received my anxiety diagnoses were my way of coping with the mood swings and chronic feelings of emptiness I was also experiencing (get me working in the checklist of symptoms here, I imagine this is how film writers feel when they namedrop the movie in the characters’ dialogue), I have a feeling the image issues I have would exist regardless of the influence of the unstable self-image part of BPD. I mean, would perfectionism alone take me to the extremes of punishing myself for missing out on all A*s by an A or two at GCSE and A-level, forcing myself to do a degree I had no particular interest in just because the university was in the single digits in the international league tables, or at one point eating only apples for 10 days until I could barely stand up because I wanted to look like those girls on 2013 emo black and white Tumblr? Probably not. But you don’t need to have an unstable self-image to latch onto the idea that only the very best will do in today’s world, lol (typed with a totally straight face)! Yeah, if the niche that is socialist twitter has taught me anything it’s that, that’s like, late-stage capitalism for you. It’s hard to look at myself and know what is a good quality, or just a character trait, and what is disordered. I think when you call a mental illness a personality disorder, the people who are labelled with it are inevitably going to have that problem.

Surprising absolutely no-one, trying to fit into these ideals I had created and emotionally detaching myself from my friends and family didn’t do any good for my wellbeing. I gave into self-destructive impulses with increased frequency and as I went into sixth form and drifted even further away from the few people I did feel close to, I began to experience derealisation (not depersonalisation, though this is something a lot of people with BPD do experience). This would come under the dissociative experiences symptom of the BPD. It was like my eyes were glass windows and I was just watching life unfold in front of me from the other side. It’s not as if I didn’t have control of my actions, I did, I threw myself into revision, but it all just felt slightly unreal, like I was going through the motions, almost robotically, detached from everyone around me. Everything was muted. Generally, I find that my mood swings between 5 different states: lethargic depression, extreme distress, anxious irritability, an almost mania like sense of confidence and purpose, and a more pleasant calmness. The best way to explain how I experience this switch is that I can almost physically feel the gear of my brain shift, with this change of energy then flowing down to the rest of my body. My thoughts take on a different tone of voice, my body feels heavier, or if I’m going up, it’s like I can feel electricity running and crackling through me. It can happen in a split second, and it can be random, though often it’s triggered by something as small as a phone call or how much I’ve eaten. If multiple plans fall apart at the same time, it can be enough to make me angry at the world and distrustful of everyone in my life, closed off and weighed down. However, back when I was experiencing this derealisation, I remember only really switching back and forth between feeling numb and feeling passively suicidal; I feel like I lost my teenage years to this big, grey cloud of meh-ness that fogged up my brain and obfuscated my ability to regularly feel any positive emotion. To use a cliche, there was this void inside of me that nothing would fill and I had learnt that trying to use relationships to do this was dangerous for me because without sounding melodramatic, it hurt too much when I felt they weren’t reciprocating my love (what a John Green line, lmao).

My fear that people didn’t like me morphed into paranoia that even the people I was supposed to be friends with were ridiculing me the second I left the room; please don’t laugh when I say my greatest pleasure during this time was to go home at lunchtime to avoid having to spend an hour sat with them so I could eat Dairy Milk Oreo, nap and listen to The Neighbourhood (careful, don’t cut yourself on that edge!). I put on a lot of weight due to binge eating, would often leave sixth form early or skip it altogether, and saw my GP, who reestablished my anxiety diagnoses now with an exotic side order of depression. When it comes to NHS services where I live, I’ve kind of won the postcode lottery. There’s a large, conservative elderly population which I’m assuming is the reason our area receives a lot more funding than other, debatably more deserving other areas, and this meant that along with prescribing me the first of many SSRIs I was to try, I was also referred back to CAMHS. I’d been discharged from them about 2 years prior, and what had back then been about a 1 or 2-month waiting list to be seen had doubled in longevity since. I say I won the postcode lottery because, in a lot of places, it’s not uncommon for people to still be waiting to be seen by their local mental health team over a year after they’re first referred. Even so, the help I was offered was very minimal; I met a counsellor once every couple of months that didn’t really specialise in any particular kind of therapy and would kind of just talk at me for the hour I saw her. This was in spite of me expressing suicidal feelings and regularly self-harming.

That being said, by the time I left sixth form, I had finally found an SSRI that worked to blunt the intensity of my social anxiety. I was attending my “perfect” university with my “perfect” grades and (prepare yourself for the twist of the century) I finally managed to get my lazy arse to the gym, and get to that “perfect” weight. I was forming emotional connections with people for the first time in years. On a shallow level, in my first year of uni, things were finally beginning to look up, and yet I was experiencing worse mood swings than ever, becoming more dependent on drugs and alcohol to function through these, and throwing myself into intense friendships where anything less than utmost enthusiasm on the other end of the relationship would send me back into that “oh my god, I’ll never make another friend in my life, I’ll always be alone, I can’t deal with this, the only way to deal with this pain is to end it!” mode. I don’t know why things got so drastic so suddenly. Maybe it was being away from my parents, or maybe it’s just that late teens/early twenties are a time when negative emotions do tend to get more serious after being repressed for years and consequently accumulating. The whole having to be the smartest person in the room to maintain a sense of self shtick was also taking a bit of a hit because university is bloody hard and everyone’s bloody smart and bloody passionate and here I was not even understanding what the assigned reading was trying to say let alone having any brilliant ideas about it to contribute; I was so quiet in one of my seminar groups the lecturer forgot I existed in a class with a grand total of 9 students. Big fish in a little pond to little fish in a big pond syndrome or maybe just more simply put, imposter syndrome, is a real thing and when you struggle with your identity anyway, it’s enough to throw you off completely. I finished that year with a first but I told myself it probably wouldn’t happen again. A couple of days later, feeling shit and overwhelmed, I did what I’d taken to doing to manage my emotions, and got high. The delusional episode ended me up in A&E for self-harm, and when they let me go the next day, I travelled back to my family home and pretended nothing was wrong.

The whole “act like everything’s fine” approach doesn’t work in the long term. 10/10 would not recommend. Without my parents around, when I went back to uni in September, everything fell apart again. I was using drugs every day, either not eating at all or binge eating, self-harming, binge drinking regularly, skipping all my lectures. Honestly, when I think back to that time it’s like I’m watching myself from outside my body. I was feeling very done with the dumpster fire (how very American of me) that was my brain. I was done with the constant 100mph up and down internal monologue. I was done with trying to cope and to hold myself together. I intentionally overdosed multiple times and after one sent me to A&E, my dad brought me home from university. It was a horrible shock for my parents: they knew I was a worrier that could be a little closed off and miserable sometimes, and they were the ones who’d first taken me to CAMHS when I was younger, but they’d struggled with that, and so from then on I’d tried to keep my issues to myself. To be honest, I don’t blame them at all for not realising anything was drastically wrong. I did a pretty good job of hiding my problems; everyone had their own things to deal with and so I became quite adept at internalising my feelings and acting “inwards” rather than outwards. It was also definitely a case of things escalating whilst I was away. With all this in mind, the overdose kind of came out of nowhere for them, but I was so detached from reality I didn’t even consider this at the time. Thankfully, I can’t really remember how they actually reacted either. Benzodiazepines do that to you, a little tidbit of information that all these teen rappers and social media personalities hyping up Xanax fail to mention. I think my dad made the decision to bring me home rather than have me stay in hospital in London, as was offered, because he thought that would be better for me. However, a few days later, after numerous, distressing visits from the crisis team (another name that will be regrettably familiar to anyone who has experienced severe mental health problems before), where I can only assume a lack of time and recourses on their part forced me to repeat what had happened over and over again to the revolving door of staff members, I took another overdose. I had become paranoid that they were out to get me and falsely believed that I was too much of a burden on my family, who were having to take time off work to look after me. This time from A&E, I went on to stay in a psychiatric ward where I was given the formal diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder I mentioned earlier. And it’s here that my life changed forever, I believe for the better.

It changed my life for many reasons. Firstly, it was incredibly validating. To learn that I didn’t have a plethora of different problems but rather one problem, the different facets of which can present themselves in many different ways and affect multiple areas of your life, was so, so reassuring. It not only gave me a clear treatment path but helped me to understand that there was a reason all this was happening. Additionally, the events forced me to open up to my parents and for them to grasp the severity of the situation. After all these years, I finally felt like I had a support system. My parents had always been there before but I had emotionally distanced myself from everyone, and being a “typical teenager” I believed they didn’t understand me (get that angst). I think in retrospect they didn’t understand me because I wasn’t using the right words. I didn’t want to sound dramatic so whenever I spoke to either of my parents about how I felt, I downplayed it a lot. My mum, who works so incredibly hard and has a lot on her plate herself, had a tough upbringing so her approach to me being miserable was pretty much telling me to be grateful for what I had. Had she known what I was really getting at, I know that she wouldn’t have reacted like this to what I was saying. The minute I got my diagnosis, she went out and bought every (mildly offensively titled) book on how to support someone with BPD out there and I learnt today has even been trying to bring an emphasis on mental health into her workplace! She is a wonderful person.

With all this being said, my main piece of advice for other people who are newly diagnosed with BPD or just suffering from any kind of mental health condition is to be brutally honest with the trusted people around you about what you’re dealing with. It will be uncomfortable but I can promise it’ll be worth it. With something like BPD, having a support system who know exactly what you’re dealing with, minus the vagueness and the bullshit, is so, so important. I say this because, despite Theresa’s green lights, neither she nor her party are doing much in the way of providing the funding for professional help. When I first came out of hospital, I had a lot of nights where I felt incredibly depressed, almost as depressed as I did before I went in. Prior to my family knowing about my BPD diagnosis, I would have dealt with these feelings in unhealthy ways but this time, I could go to my mum and stay with her and just cry it out until the feeling passed. That is also a useful sentiment to remember, that the feelings will pass. It’s in the nature of BPD to swing around, when I’m not experiencing a period of depression, and that’s something I find it helpful to remember. I personally really like the Youper app to track my moods because when I do get suicidal, feel anxious or wired, I have something to look at objectively to remind myself that I did feel like this before, in fact, I felt like this yesterday, but a few hours later I told the app I felt okay again. It also helps you to dissect your irrational thought processes and identify “thinking traps”. Meditation, ASMR and CBD are big parts of my life and stability, though I would recommend doing some research into the latter before trying it yourself.

On a less subjective, more physiological level, I notice that my medication really aids my emotional stability; when I have been off it, my mood swings are a lot more intense. So whilst medication isn’t for everyone, it can be something to consider talking to your GP about to see if it could be beneficial for you. Another help is the DBT skills course I completed in March, DBT being the abbreviation of dialectical behavioural therapy, the treatment specifically developed for BPD by Marsha Linehan. If you have time, she’s a great person to do some research into. She herself was diagnosed with what doctors called an “incurable” case of BPD yet she’s gone on to do the most incredible things and help so many people also suffering from the disorder. Not only did DBT provide me with a skill set of more functional coping mechanisms for both interpersonal insecurities and individual struggles, but I liked the fact that once a week I got to be with a group of people who really understood what I’m dealing with and didn’t judge. Even if you can’t find a DBT group, it’s worth checking to see if there are any mental health peer support groups in your area for this reason. I found that being around people who are dealing with similar issues helped me to see my own struggles more objectively; it reminds you that what you’re experiencing is not about you personally and that whilst you may feel isolated, you’re not. The world hasn’t got it out for you. It’s a condition that many people experience. In terms of the feelings of emptiness BPD causes, I have found that since my diagnosis, I’ve actually had more of a sense of purpose in life. On a practical level, having therapy along with a year out of uni and the presence of a constant support system has had me time to get back into writing properly. What I’ve found to be even more rewarding, however, is my participation in the online mental health community.

Something I wasn’t made aware of prior to my diagnosis was the amount of stigma there is still towards mental health issues, Borderline Personality Disorder especially. It really is one of the most demonised mental health issues in and outside of the healthcare system and that’s a hard fact to learn, because it’s a difficult enough condition to learn to manage already without knowing that there are people out there who think you’re a monster for it and are going to judge everything you do through a certain lens. Whilst we are a lot more accepting as a society of conditions like depression and anxiety, conditions such as bipolar, schizophrenia and personality disorders are still greatly misunderstood by wider society who have largely taken their understandings of these illnesses from ill-informed media portrayals and shallow, surface-level observations of a sufferer’s behaviour. I doubt the name “personality disorder” helps matters; it’s hardly the most flattering description of what we’re dealing with I’ve ever heard. I’ve found that even mental health professionals and other mental illness sufferers have a negative bias towards BPD. There’s a widespread view that we are dangerous, manipulative individuals who choose to be difficult and act erratically, that our behaviour is not “organic” like that produced by other mental health problems. I have no idea where the latter assumption comes from. Most experts on the condition tend to agree that the mood swings, impulsive, destructive behaviour, and irrational thinking originate in the hypothalamus and come from a faulty fight-flight response or other atypical brain structures; in other words, BPD has a biological basis. Whilst I agree that we can learn to change our coping mechanisms, the idea that they are as a result of anything other than pure desperation and mental anguish is incredibly puzzling and dehumanising. Simply looking the causes of the condition up online or doing a small amount of research from a credible source debunks all the common BPD stereotypes, yet people like to speak about it as if they know everything about the condition just because they’ve heard a few horror stories. There are nasty people in the world. Some of them have BPD, but that doesn’t mean everyone with BPD is a nasty person, and the bottom line is that most people suffering from Borderline Personality Disorder will hurt themselves before they hurt anyone else. We are so hypersensitive to any changes in our relationships in the first place that the last thing we want to do is damage them. When we say something feels like the end of the world, that’s because the emotional dysregulation part of BPD really makes it feel like it is. We’re not being dramatic or trying to get your attention. In fact, I can say for certain that despite feeling this way on a daily basis for about 7 years, I rarely actually voiced the sentiment. I still don’t. But I should be able to. To give the example of one person suffering from physical illness and one suffering from a mental illness, where both publicly talk about the pain they’re experiencing, why is only the latter of the two called an attention seeker? If the former tweeted about how much pain they were in, nobody would bat an eyelid. Why is this? When so many people experience mental health problems? When the gender who are typically expected by society to repress their feelings accounted for over 70% of suicide victims in the UK last year? It’s clear that keeping our feelings to ourselves and suffering in silence doesn’t do us any good, so why are so many so eager for us to continue doing so? I think being open about mental health simply needs to be normalised, and that once it is, hopefully, this sentiment will die out. I find that by being open about my mental health on social media (still quite selectively, I must admit! I can’t see myself making a post about BPD on Facebook any time soon!) has given me a sense of purpose because I do feel like I’m helping to normalise this kind of honesty. With regards to the stigma that surrounds BPD specifically, I feel that my presence online and my support of others helps to show that we’re just human beings who are struggling, not the awful mythos that surrounds us.

To finish, one of my main goals in my recovery is to be more compassionate to myself. BPD is a hard enough diagnosis to have without constantly internally doubting and questioning it. I find that as the months go by, I am feeling more and more stable, and this leads me to question if I was ever sick, especially since I only displayed 5/9 of the borderline traits in the first place, which meant that I only just met the diagnostic criteria. I don’t have psychotic rage or complete blackouts and tend to act inwards rather than outwards. I am what is considered within the mental health community to be a “quiet” borderline. I know theoretically that this doesn’t make my condition any less valid, but for this reason, part of me fears moving towards being “well”. Because if I’m well, then I feel like I’ve lost part of an already fragile identity. Of course, I’d rather not have BPD. But because I’ve been expressing symptoms for so long, I worry what’s left of me without it. At the same time, I fear going back to a place where my BPD is so severe that I have to go back to hospital. So really, it’s like you’re stuck between a rock and a hard place. It’s a double-edged sword. Is that enough cliches? The thing that I wish more people could understand is that mental illness in itself is traumatic and that even when you’ve moved on, what you experienced will always be a part of you. You still need that support. I’m not going to lie, resisting the urge to indulge in old coping mechanisms and habits is hard, and whilst the sense of pride I feel every time I don’t, or every time I use responsibly something I’m used to abusing is rewarding, there are days where waiting for the need to use them to pass is very long and very hard. I need to stop telling myself that just because I am feeling better than I did, I don’t deserve that support anymore. I do. I still deserve compassion. I still deserve a safety net. I still deserve a sense of understanding from the people around me. I deserve all of it, as does everyone else. I also deserve to be proud of how far I’ve come already instead of berating myself for not having come far enough. As I write this I haven’t self-harmed in 169 days, have been at my current job for coming up to 6 months, have an interview for a psychology course at the uni I came to love in a week’s time. I’m finally somewhat healthily managing my weight for the first time in years! I have also decided that once I do return to university, my reason for being there is not contingent on me maintaining firsts; my mental health, and what I do with the degree is much more important. I would ultimately like to go into clinical psychology and do as much as I can in that area to help people going through similar issues. With the current state of the mental health (and healthcare, in general) system in the UK, it’s definitely easy to get disheartened that the services it provides will never be adequate due to funding issues. However, in the meantime, I think the more of us with lived experience that can get into mental health care, the better the service that eventually is provided can be. Every week I’m thinking of new things I’d like to research once I have the footing, epigenetic and intergenerational trauma and the use of psychedelics and the benefit of peer support groups. There’s always a way to turn the negative into a positive, even if it takes time to learn how to do so and I think after all these years, I’m finally getting the hang of it. If my brain has been a “dumpster fire” for the last however many years, then I don’t want to let the ashes go to waste. I’m going to make them into some really morbid confetti! As I sit here writing this, I can firmly say I am happier than I’ve ever been. Game of Thrones is pissing me off (might do a post how identity and attachment issues lead to a correlation between BPD and obsessive character fixations at some point because BOY has that been driven home to me this week!) but tomorrow I’m going to an ABBA party with uni friends, Yvie Oddly is smashing drag race, and my cat is lying next to me purring. It gets better. The hard days become less frequent and they get easier to cope with too; you can learn to ride the waves and find reasons to continue doing so, regardless of how tiring it might be sometimes.

My pipe dream for this time next year is that we have people in government who really care about the invisibly ill of this country. That Downing Street can do more than turn green. I hope that we get to see more realistic and sympathetic portrayals of BPD in the media that draw attention to the issue without glamourising or romanticising it and that we get more portrayals of queer, disabled and POC experiences of mental illness too as it’s not just skinny caucasian girls that deal with this shit! Most importantly, I also hope that I continue to flourish, and wish the same for everyone struggling with mental illness/any kind of turmoil. Anybody who reads this ’til the end, wow! Thank you! It was a bit of an essay but what do you expect coming from an ex-history student and wannabe author, lol! Please let me know if there is something you’d like to see me post about on this Tumblr, such as any specific BPD symptoms and how they might present, how I deal with social anxiety and body image, or even anything completed unrelated to mental health! God knows I love the sound of my own…prose? Is that the right word to use?

I hope you enjoyed reading!

Lauren x

#mentalhealthawareness#mentalhealth#borderline personality disorder#borderlne#bpd#bpdrecovery#social anxiety#socialphobia#bpdprobz#body dysmorphia#recovery#addiction

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The desert of adolescence is dry and brutal. Dunes and murderous heat engulf the eyes and heart with unwavering repetition. Walk for months and you may only inch closer to enlightenment. But there, in the distance, is an oasis. An understanding and all enriching moment of freedom within the drivel of growing up. For any, this is oasis is personally founded in their art, experiences and ideologies. But in this generation, not a single youth’s oasis is complete without Surf Curse; not complete without their generational ability to connect.

It’s known that if you’re a teen and with the opportunity to see Surf Curse live, you simply must. Having been a pair of blinded youth at one point, Nick and Jacob have grown to a point of personal understanding. They began as idealistic 18-year-olds, similar to their fans, but now stand as formed individuals who grasp their inner values and principles. Mirrored in their new album, Surf Curse have come to terms with what it means to grow and the beauty that exists in the process. While terrifying, the desert is gorgeous in its grandiose novelty.

But here and now, at the oasis, Surf Curse is delivering a message of hope. Their body of work, so far, can be seen as the journey of self-discovery that now culminates with a catharsis of teenage moon dreams and film history. They want all youth to have the freedom they were able to attain through creating their art. And in creating that freedom, Surf Curse is cementing an opportunity for normality for young lives of turbulence. From now on, the oasis will never die and, due to their efforts, will be able to speak to limitless bleeding hearts. - How’s your day been going so far and how have you been as of late?

Nick: My day’s going pretty good so far, just started honestly as I had a bit of a late night. Both of us did. I was up until 5 in the morning just having a good chat with some friends. Got only like 4 hours of sleep.

With the new work finally coming into the foreground after a while of planning and rollout, what is the most overwhelming feeling in your life right now? The one that defines you emotionally.

N: I guess this release has been so different from everything else we’ve done. It’s very well organized and the record is well produced. There’s been a lot of money, time and effort put into it. I think it's the most organized it's ever been. There are no surprises which is really nice, but you do get the feeling of a large stakes situation. It's just anxiety hoping that everything goes well. We’re both very confident in it though. I’d also say it's just a lot of waiting. The records been done for over half a year now so we’re just excited to see everything rolling out.

Through this last year, what do you look back on as your favorite memory and almost a time that defined this entire few months for you?

N: I really do think recording this last album was such a great experience. We usually record so DIY but this time around, with the label backing, we were able to go into a studio with an engineer. It was such a special experience after over 10 years of home recordings to be able to go into a studio and make a professional sounding project. I know for Jacob and I, it was one of the best experiences of our lives. Every day was such a blessing.

When you look back at the early days of this band in 2013, how do you compare your artistic vision from then to now and do you think you are in a place of satisfaction with it?

N: I really love where it is now. I think there’s been a lot of growth and it’s hard to anticipate growth really, it just comes naturally. We were fortunate that as we've had a lot of time to sit with ourselves and write freely. This last record is one of the things I’m most proud of and it's a very obvious change in our sound and style. But again, that’s been a natural progression. Any musician or artist goes through that. It’s not a conscious effort either, it just progresses. When we wrote those first songs we were both 19, but now we’re each 27.

You did mention working with a new producer and really having it all be a tighter and more professional effort. But how do you feel that is visible within the songs and how do you feel seeing it all come into fruition in a professional sense.

Jacob: I think the production of it changed a lot of our songwriting. We had a bunch of demos but only in entering the studio did we realize the true capabilities we had. I think the original songwriting is still there but there was just a feeling we could make it much more true to life. As we were recording we noticed how cinematic and grand it is as well. We noticed it was a large cathartic experience. That, in some places, was a result of being able to add strings to something or having someone come in to create larger harmonies. It influences the songwriting in that you have to write with something truly grand in mind.

In the run-up for this project, there’s been a lot of talk about the influence that came from old cult film and the idea of peering into adolescence through film. With some songs like Midnight Cowboy the influence is obvious, but what other films do you feel achieved that vision you pulled from?

N: I think it's funny because there's a lot that is very on the head. We have some films that pretty directly translate to the song. Usually, a song is just a melting pot of so many ideas that it is never limited to one thing. I think with the song ‘Opera’ it is very clearly about Dario Argento’s Opera in the style and structure. But the themes are more relevant to our lives and what is going on within them. With the entire album’s feel as a whole, we were trying to make something like the movie ‘The American Friend’. Before we shot the album art we watched it with the photographer just to get a general vision for it. I really do feel it is so many different films that we consumed. Even when we were recording we had VHS’ playing constantly in the background. You can look at the tracklist and breakdown a lot of the obvious influences.

If you could personally take any film in history and strip its soundtrack, thus replacing it with this album, which do you think it’d fit with best?

J: I don't even know if we can. I think we'd have to make the movie go with it.

Then what would the plotline of that film be?