#that are written in languages that English pillages from

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

hello!! ⭐, I saw that your order section was open and yesterday I read your story of buggy with the Roger effect and Jessica Rabit and I loved it, and I would like to know if you could do a one shot or something shorter if you prefer showing how they met and they decided to get married I love your stories and I think that, like your buggy, he is my favorite character. If you don't like this request or you think it's not good to do it, you can just ignore it, it won't be a bad thing 😸 thank you and have a good day!! 💗✨ (pd. English is not my first language so sorry if something is not written well😔)

Deal! I love this little idea

Buggy x FemReader

Small angst + Fluff

Heart on my Sleeve

Prequel Of Roger and Jessica Rabbit Effect

Wanna Buy me a Ko-Fi ☕️

• Your village was one of the poorest villages in the East Blue, the taxes from the World Goverment crippling your home to be a starving wasteland.

• Mainly to the wealthy Governor who lived above your town.

• You owned a fabric shop but the fabrics you owned were old and starting to rot from the lack of buissness. The moths having more use put of your fabrics then you did-

• The newest pirate on the scene Buggy the Clown shows up to your village ready to pillage it, in his early 20s with a fresh faced crew. However they did not expect the village to look worse then before they arrived.

• "I thought you said this place had money?" Buggy asked as he looked at the place. Lowering his blades as it looked like this place- it was in shambles. Like it had been pillaged to time then a pirate

• You had walked out of your shop, seeing if maybe the baker had just enough flour so you could feed yourself. Turning to see the group of pirates that seemed better off then you and your people.

• Buggy stared hard at you and matched forward, seeing that you were quite pretty in his eyes as he stood before you.

• "You! Tell me what the hell is wrong with this place! We heard it was rich here!" He said angrily, clearly upset at not getting to a small village that at least had a few Berries.

• You looked up at the pirate, noting the far too big of clothes for his frame and his painted face- Not liking he was putting such an unflattering green around his watercolor eyes. His face twisting up in anger as he caught you staring at his face.

• "What are you staring at!? You looking at my nose!" He yelled angrily, his fingers going to the inner part of your coat where you assumed some weapon would be.

• "No your shirts too big for your frame and that shade of green doesn't compliment your eyes well" You said truthfully, At this point a knife or bullet being a kinder death then starving anyway-

•"U-Uh- What?" He said confused, Unsure how to answer. You reaching forward and putting your arms around his frame to pull back the shirt. Taking a pin from your pocket and pinning the shirt back so it fit properly.

• "See- Your shirt is too big. It looks better fitted like that" You pointed out, His faze looking down at the pinned back shirt. His face red at how close you got to him, or that you'd touched him at all.

• "As for money we have non. The governor has the taxes so hide no one here can even feed themselves" You said truthfully, The young clown blinking at you in surprise.

• "Er- Y-Youre making fun of me somehow right? Like my Nose" He tried to yell again grabbing the front of your dirty shirt- clearly not used to someone trying to give him kind useful advice without some sort of motive.

• "I would never make fun of your nose, it looks fine to me anyways" You snap back and slap his hand away calmly. He blinked at you surprised and released your hand- His eyes going up the hill of the village and seeing the grand governors house hidden in some trees.

• He huffed and shoved you hard, you falling into the mud as him and his crew marched past up to the Governors home.

• However what did surprise you was the next Morning the Captian and his Crew stood in the village square and announced he now owned the village. Saying he was Buggy the Clown- and that he was now in charge.

• Before starting to hand out some stolen treasure??? Giving some supplies he had 'liberated' from the Governors house.

• You also noticed how his eyes lingered on you as he did this.

• It had been a few months like this, he would stop by randomly pay for the village. He wasn't taking taxes but instead paying things- it was improving greatly, the cracks of the pavements on the streets getting repaired, new paint on the building and new businesses flourishing-

• But you noticed how he would pay extra attention to your shop- Getting all his things from you. How you got extra rolls of fabric delivered to your door or how he would pay for all these extra accessories to his costumes.

• "You seamstress I want another coat!" He yelled as he invaded your shop.

• Buggy was there again, asking for another ridiculous costume. You couldn't help but notice how often he was coming by- claiming he wanted new costumes by you and wanting to be measured everytime he came in.

• How he would blush when you measured around his chest. "You know, I noticed you always come through here and stop specifically at my shop for new outfits when you wear the same coat" You tease, watching him blush at you pointing this out.

• "So what!" He yelled out, his face as red as a cherry. You look at him and raise a brow at him, Not even having to say a word as Buggy deflated.

• "...I uh wanted to take you on a date" He grumbled, finally admitting what his plans were. You smiled at this, Setting the tape aside.

• "Now please do tell me, Why should I accept your offer for someone who not only yelled in my face but pushed me in mud-" You point out, even though you knew he most likely made up for it by him saving your village.

• "..I am sorry about that.." He forced out, you could tell he wasn't used to apologizing and was trying his hardest.

• "I forgive you, But that doesn't mean I'll forget" You say calmly. Smiling softly as you saw him looking ready to flip put at the rejection but you held a hand to him-

• "I know- So why don't we make a deal. Since I can tell you're really sorry why don't we agree to dinner and go from there? Its not a date per say but its a start" You said with a smile, his eyes lit up at hearing this at the prospect of getting to win you over.

• "Really!?" He says excitedly, Jumping up and down like a school boy as he blushed and giggled into his gloved hands like a kid. You couldn't help but find it adorable-

• For the next year Buggy would send gifts, love letters, help rebuild the village. Do everything to get in your good graces and ask for a official date every time he visited.

• Buggy would essentially own the Village at the point, 30% of his money went to the village to get it on its feet and keep it a small strip of paradise the very limited taxes he implimented later affer the village was florishing acted as a small form of secondary income. Mainly making sure people knew the place was protected by him as his reputation grew through time.

• Him even showing his unique Devil fruit abilties- Which you often abused for him to float up and grab the more expensive rolls of fabric or hang up finished cloths.

• The village also being a popular tourist destination for the friendly locals and nice scenery. So for Buggy it was worth the investment since originally put in.

• After that 'probation' year you would finally agree to officially date him and he was over the damn moon.

• While he would be secretive about you, his love language was strong. He is both physically and verbally affectionate- While he still throws his fits you know how to handle him well. Loving him both for his strengths and flaws.

• It would be 1 years of dating before Buggy would start planning how to pop the question.

- You were closing up shop for the day, humming along to a made up tune when you heard the back door of your shop being unlocked. You didn't have to look to know who it was, only one other person had the key to it.

"Hey Buggy Boo" You call out, smiling as you heard Buggy grumble and peel off his boots to leave them by the front door.

"That is still such a bad nickname" He grumbled before walking behind you and kissing your cheek and wrapping his arms around you. He smelled like the sea, clearly having just gotten off his shop to visit you. He had been taking more time out to see, wanting to get his bounty higher. Currently proud of his 5,000,000 berry bounty which for a early 20s pirate was fairly good he claimed.

"Ah you love it" You giggle which earned a adorable chuckle from the man.

"You know (Y/N)- I uh really like you and Want to spend my.."

"So I wanted us to have dinner tonight- I know you like that place down the street and want us to go there" He said, his voice very soft- Much softer then normal.

Smiling you turn around and kiss him on the lips.

"I'd love to" You say cheerfully, earning a crooked smile from him as he held you close.

As promised, that night Buggy took you to your favorite restaurant. Having gotten a private table in the back, you two spending hours just talking and sharing a meal together.

Buggy even pulling out a box of your favorite candies he had gotten out from his last adventure.

After dinner he lead you away to the more scenic parts of your Village a small meadow pass that had the most beautiful blue and white flowers, under the moonlight it looked so magical. You saw Buggy reach in his pockets and turn to face you, nervousness painted on his face as he shuffled his feet. Clearly prepared to get on one knee-

"You stole my Thunder!!" He cried in faux anger, you laughing hard as he ranted about how you knew so quickly, happy tears running down your cheeks as you smiled and his face turned deep red.

"Yes I will!" You said with a wide smile, your excitement getting the best of you as you slapped your hands over your own mouth. His jaw dropping in shock.

"I've been planning this for 4 months!!" He whined, face so red his nose was glowing as he stared at you.

"Im so sorry Baby, You just- You talk in your sleep my Love." You reveal with a smile, His face twisting up as he realized you'd known the whole time and let him try to have his moment anyway. You had just got too excited and answering too quickly-

As this sunk in he smiled widely and started to laugh, he couldn't help it! You were just too perfect for him! Despite everything you still let him have the spotlight. He kissed your lips eagerly and held you close, rocking the two of you side to side in pure joy.

"I.. I love you (Y/N)..So much- I cant wait for you to be my wife.." He said as he pressed his face into your neck- You could feel the warmth of tears hitting your skin exposed. Your arms wrapped tightly around him as you hug him close and cried against him in joy.

Pulling the both of you to the ground with a loud laugh as you two laid in the flowers- Laughs leaving you both as tears stilled from both of your eyes.

"I love you too Buggy Boo"

#x reader#one peice x reader#one piece#one peice live action#buggy one piece#buggy the clown x reader#buggy x reader#buggy thoughts#op buggy#buggy x female reader#buggy x wife reader

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes when i work on my poetry and research for my (final year high school) extension ii english, i feel like such a fraud and a failure. i write naturally and i write for fun, and especially recently getting extremely addicted to fanfiction the stuff im reading and influencing myself with is easy and simple, maybe not in plot but in its use of language. its not dense and fanciful like the classics, its not teeming with extended metaphors and symbolism to shatter your mind and link with postmodernism and contextual concerns

it’s just writing.

i write poorly and worry it’s not good enough for my teacher, for the markers who will put a number on my page. they who have been studying literature and language for years, decades, judging the work of i who have not yet reached one score in age.

i feel like i’m being asked to reinvent the wheel, when all i really want to do is ride in the cart

and maybe it’s all right to say fuck it and just hop on. writing is FUN. if it makes people feel things i’ve already won. my work doesn’t need to be dissected and broken down and analysed as perfection. it’s not fair.

fanfiction has helped me realise that I think. i never used to read it, some sort of dignity thing. even now i have to fight the shame when i tell people im reading fanfic, but at the end of the day this writing has so much heart. it makes me excited to write, it makes me so excited to READ. it traps me in its joyful escapism like any book could. I read the whole lotr in less than three weeks, i read a fanfic 100,000 words longer in three *days*. this kind of reading is FUN. sharing stories should be FUN!!

anyways, here’s my most favourite poem of all those i’ve ever written. it has no deliberate techniques, it does not follow a particular form, its rhythm is wobbly as best, its concepts are not earthshakingly deep. it’s about wanting to run away and be a pirate, just because it’s fun.

and fuck if it’s not better than those i wrote to be scrutinised. it has more of my soul than i fear those ever will. does that make me a bad writer? i hope not, but maybe id be ok with being bad if it meant i never had to give up the fun of it.

Dear Pirates,

Way out on the wide blue sea

Deep and dark beyond belief

You are all the things I long to be

O pirates on the great blue sea

From shore to town to shore once more

You pillage and plunder and break down the doors

You run and you sail away from the moors

O pirates with ships filled with treasure galore

Your tables are stained with blood and with beer

And though you are hunted there’s no time to fear!

You’ve places to be, not too far or near

O pirates, I dream that your ships will dock here

Great waves part around you, except when they don’t

And people surround you! Except when they won’t

All creatures, they run from your tattered black cloaks

O pirates, you run right on back to your boats

You sail straight off from all that is right

You look out for towns that gleam in the night

Where’s mischief, there’s money, and money you like

O pirates, for money you’ll put up a fight

And glory you love! And name-making too,

And name-taking just spells out more fun for you

So tell me you’re looking for somebody new

O pirates, let me be your newest recruit

And in spite of all the wet clothes that you’re wringing

You leap down! Your ropes fly, your cutlasses swinging!

Both quiet and loud, your sea-shanty singing,

And back to your ships your men keep on bringing

Great piles and rucksacks and chests filled with gold

And stories of danger, of recklessness bold

Your name piles with legends, with glory untold!

O pirates, does glory keep you from the cold?

If I were a pirate, I’d be ever so brave

And with crewmates and treasure there’s something to save

So even when pirates seem ever so grave

There’s safety and welcome, a home on the waves

anyway the actual point of fandom is to inspire each other. reading each other's fics and admiring each other's art and saying wow i love this and i feel something and i want to invoke this in other people, i want to write a sentence that feels like a meteor shower, i want to paint a kiss with such tenderness it makes you ache, i want to create something that someone else somewhere will see it and think oh, i need to do that too, right now. i am embracing being a corny cunt on main to say inspiring each other is one of the things humanity is best at and one of the things fandom is built for and i think that's beautiful

53K notes

·

View notes

Text

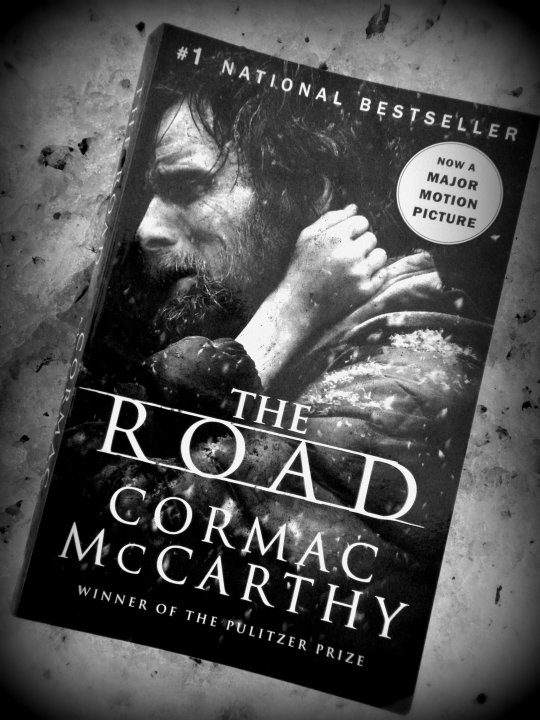

A Review of Cormac McCarthy’s 'The Road'

In the winter of 2009, I watched a dramatic film set in a post-apocalyptic era where a father and son travel on a long road. They anticipate a haven to live out their remaining days on Earth. The film stars Viggo Mortensen as the father and Kodi Smit-McPhee as the son. Although the story moves at a slower pace than other films of recent years, a definable mood is overwhelmingly present within the film’s storytelling. After reading the book on which the movie is based, I have discovered the origin of the dark mood that surrounds the story of survival and last hope. The Road is a dramatization written by Cormac McCarthy.

His other written work has also been adapted into films such as No Country for Old Men and All the Pretty Horses. The prose written on the page within his books is intentionally simple and, on several occasions, defies the basic grammatical rules of the English language. Why would “cant” be written without an apostrophe when “he’s” has been written into the same paragraph and included one? This quirky behavior is a rare treat for successfully published writers. The only other author with a sense of writing style would be Hubert Selby, Jr., who has the notorious style of placing the forward-slash symbol (/) as the permanent replacement for an apostrophe, alongside ignoring the rules for other punctuation symbols. However, there is more to The Road than the nuance of the author’s punctuation style.

The book's structure does not comply with the traditional narrative of fiction storytelling. It strays from the usual methods by describing brief moments in time that appear as fragmented memories. The primary characters, a father and a son, exist in the present tense. Their daily travel down the road is written as a daily log of what they do and what they discover. The father recalls memories of their former life with his wife, but it is told in brief flashes of memory. Nothing is ever referenced with an explanation for what happened to the world that would leave so many people wandering the Earth as vagrants.

Despite the lack of a traditional arc that would build an emotional and character development as the reader is accustomed to witnessing, there is an ongoing tension of survival for the two main characters. They must avoid the cannibals, find shelter from the rain to comfortably sleep every night, pillage for edible food and clean water as often as possible, and grasp every ounce of hope that could be mustered up.

Only speaking of my personal experience with reading the book, it is more entertaining to watch the film adaptation than it was for me to read the book. Comparing the book and movie, a couple of changes were made to the story I would contemplate an improvement. The flashback scenes include more information about the mother. Why was she willing to abandon her family? The movie attempts to explain her reasoning behind the decision.

In addition, a few scenes from the book have been intentionally misplaced in the film’s timeline. The decision was clear to me that the movie wanted to build upon a growing tension within the character development and emotional story. In my opinion, the changes to the timeline are minor, as the story draws a more satisfying development arc.

youtube

#Cormac McCarthy#dystopian#books#books and reading#book recommendations#book review#review#The Road#Hubert Selby Jr.#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Does anyone know if there is a version of the phrase persona non grata that refers to objects instead of people? I need a way to describe the Modern Quilt Guild’s attitude towards quilts which it considers “derivative” and won’t let be entered in their competitions.

“Obiectus” is object in Latin; would it just be obiectus non gratis?

#I do not know any of the grammatical rules of latin#I am just good enough at pattern recognition that I can use etymology to parse out a lot of root words and get the gist of things#that are written in languages that English pillages from

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

How did English get so many Latin words ? It’s a Germanic language right?

Hello! Thank you so much for that question and providing enrichment to the tiny linguist in my brain.

English is indeed a Germanic language. It doesn't behave very much like one these days but it's actually kind of Double Germanic because it has it's roots in the Angles, Saxons and Jutes who settled Britain and influence from the Vikings, who tried pillaging the British Isles and then settled there.

Before these groups arrived, the British Isles were a Roman colony (and Celtic before that), which left some influences. The Roman baths in Bath are a physical example. But Latin entered into English in other ways too, especially since Latin wasn't really anyone's first language anymore by the time the Old English started to exist.

Firstly, the ancestor of Old English already had some contact with Latin.

Secondly, Latin was a high prestige language. It's much easier for prestigious languages to influence others (this is why English didn't borrow many words from Celtic languages). Latin was the language of religion and scholarship - the Bible and all church services were in Latin at the time and any educated person would have written and read Latin texts.

Thirdly, some of those words entered English through French. You see, French is a Romance language related to Latin so sometimes it's difficult to know when a word was borrowed at a first glance. But when the Normans took over Britain a lot of Norman French entered the vocabulary (again because as the ruling class they had prestige) and now you have a Double Germanic language with Double Romance influences.

And last but not least some Latin words are more modern. Because Latin and Greek were already high prestige language connected with scholarship they kind of just stayed that way and the West decided that if you're naming something (scientifically) it should be derived from Latin and/or Greek. (shout out to my favourite phenomenon where some plant or animal gets a name and it's a Latin/Greek word followed by the name of a scientist with a Latin suffix attached eg Lophophora Williamsii).

I hope this explanation made sense!

If you want to learn more about Old English you can also check out A History of Early English by Keith Johnson which I have uploaded in my MEGA folder of language resources.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Exploration Into Minecraft and Language.

I’m breaking this into sections and doing this literally just because I did a bunch of early human language stuff as review and I need a way to. Make my brain stop thinking about history. But I’ll start with canon knowledge first and slowly break into less official stuff from there!

Everything’s under the cut, because this got very long.

Early Language:

Pictograms are written languages where an image represents a thing and specifically just that thing, an expansion on pictogram languages are ideogram languages, in which an image represents multiple things. Likely the most well known pictogram/ideogram language (as it evolved as the need to say more did) was Hieroglyphics. Hieroglyphs were modeled after specific things but eventually grew to have many different meanings.

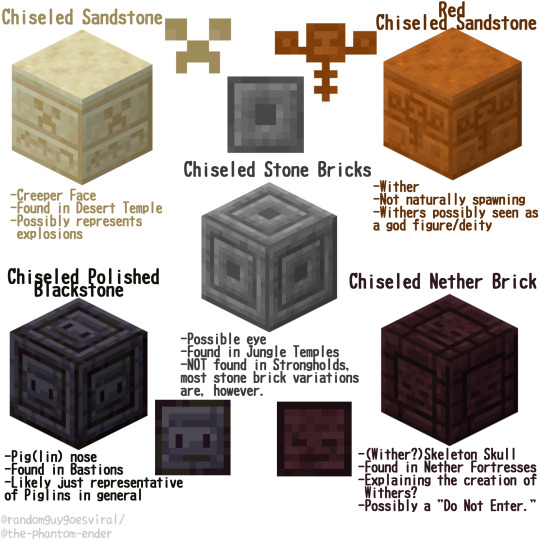

What’s the reason for the history lesson, I hear you asking? There’s evidence of a pictogram/ideogram language in Minecraft, of course! Chiseled sandstone (both normal and red) have images on them that highly seem to imply that there’s language and meaning behind them! Sandstone has a creeper face (which as well as being obviously a nod to creepers, could also mean explosions, as these blocks are found in Desert Temples), and red sandstone has a depiction of the wither (it wasn’t uncommon to have drawings of god-figures in pictograms so there’s a chance that withers were a deity of sorts).

There’s also chiseled stone bricks, but that’s a much more abstract shape. Perhaps it’s meant to symbolize an eye, though, and therefore the end, as stone bricks are often found in Strongholds, but that’s much more speculative. Chiseled stone bricks themselves also naturally generate in Jungle Temples. Chiseled polished blackstone seems to have a face on it of sorts (resembling the nose of a Piglin, most notably), and chiseled nether brick resembles that of a skeleton skull.

The only two major minecraft structures that don’t seem to have chiseled variants with symbols on them are the End City (purpur) and the Ocean Monument (prismarine). Ocean Monuments aren’t easily livable spaces, so it makes sense that language wouldn’t be a major factor, though. For the End, however, perhaps the lack of a symbol block is because there was already written language.

(above is a chart with all blocks mentioned in this section, listing their names, the symbols that appear on them, where they generate, and what they may represent)

Development of Language:

Here we get into full written alphabets. There are several types of alphabet, but “true” alphabets are those with distinct characters for both consonants and vowels. The most widely used modern day true alphabet is the Latin/Roman alphabet. Minecraft items in general adhere to the language the player is playing, so for the sake of things, the language you speak doesn’t play a factor here.

As many people know, there’s actually a true alphabet present in the game! That is, of course, Standard Galactic! There’s no official words tied to it, but it is the script used in the enchanting table and various other smaller details in the game! Now one thing to note about the Galactic in the enchantment table is that if you actually take the time to sit down and translate the words present, they don’t translate exactly. Most of the time, they will be a word similar to the enchantment, but not the same. Sometimes it’s just entirely gibberish.

(above is a chart of the Standard Galactic Alphabet, with the scripts corresponding Latin letters)

What this means is that, talking about translation wise, Galactic and English (or whatever language you play in) don’t translate directly into each other. So it isn’t simply just English words but different letters. At least not exactly. Perhaps this is the language Villagers speak, as they can and do trade enchanted books and items.

What people may not know, however, is that there’s actually another script present in Minecraft! Or… at least kind of. There’s six letters of a different script present in the game. And unlike Standard Galactic, it doesn’t appear in any other sources, so we will likely never know how it works in its entirety. What we do know, though, is that there are symbols on the End Crystals! And, digging into those textures, we can translate a word out from them by messing with them a bit! That word is… Mojang. It’s probably meant to just be an easter egg used to fill space, that one.

(above is a visualization of how the symbols present on End Crystals can translate into the word Mojang)

That being said, though, lore-wise, it can have a bigger impact! Remember how I said that End Cities are lacking in a pictogram? This can serve as an explanation! Perhaps the Enderman developed with language, even as far as having wide-spread Galactic (as there are enchanted books and armor in End City structures), but upon entering the end, after many years, they broke away from the standard script. Development of a new written alphabet and even more different languages is certainly possible, it’s happened plenty in the real world. Isolation creates new advancements. So the Enderman create the language present on the crystals at some point, eventually.

Additional Concepts and Less Canon Tidbits:

Here we get into wild speculation and fun ideas that don’t really hold any weight! If you don’t want that, that’s entirely fair!

Obviously, Villagers have what is technically the most advanced society economically. They trade for goods, have various jobs and artisans, and have an item that they value costs at (emeralds). They also have the most concrete communities, having villages, obviously. Villagers also have domesticated animals! Both in the sense of farm animals and also cats.

There’s also Pillagers- which I haven’t mentioned much here. They have giant mansions which seem a lot like manors. They don’t do trade, but they’re skilled fighters and have trained war animals, as well as people who have specific combat styles. They’re plenty advanced, especially because they have potions and therefore understand medicine at least to some degree, but much more war-oriented.

Piglins are essentially wandering tribes. They don’t trade, they barter, most of their structures are in ruins and the structures they do have are very heavily guarded because they contain riches. The Piglins seem to follow animals that they use (hoglins), but are also seemingly in the process of domesticating them. They also don’t seem to have much more in the way of language than pictograms (though there is Galactic present and they do seem to understand enchanting and brewing to an extent). Piglins seem to be midway in advancement, really.

Enderman are… complicated. Because yes, they do have written language and they do have cities and communities and means of transportation, they don’t exactly… interact. They don’t trade. They’re technologically advanced beyond any other groups in the game, but they are mostly isolated. So they’ve advanced entirely alone, building off only themselves.

There are also Nether Fortresses but that’s… complicated. Those tied exclusively to these structures are Wither Skeletons and Blazes. These are very different creatures, however. There’s also the fact that Blazes spawn almost exclusively from spawners. It’s hard to tell if Wither Skeletons or Blazes are the proper inhabitants of the area, but it could be both. Wither Skeletons likely originated from traditional Skeletons adapting to the environment of the nether. They’re undead and therefore it isn’t impossible that they may have, at least in the past, known how to build structures. Eventually losing that ability as the Nether degraded them.

Nether Fortresses provide no trade but there are chests that can contain loot! And some of that loot suggests a knowledge of places outside of the Nether (horse armor, most notably). Wither Skeletons/Skeletons generally may have also descended from people fearing a god figure called the “Wither” and therefore, the blackened skeletons were made out to be part of what would summon the creature. So they were kept in the Nether to avoid something like that reaching the Overworld.

There’s also… Ocean Monuments. I have no idea with those. Elder Guardians are likely a figure that’s revered. Giant structures were built for them to appease them or something of the sort. They might be told to keep the seas at peace or something of the sort. Not an active civilization, however. A structure built to pay respect to something powerful.

There’s probably plenty of things I blanked on mentioning, but yeah! This has been fun! I don’t know why this is my definition of fun.

#phantoms membrane#minecraft#mineblr#minecraft theory#minecraft analysis#minecraft language#aaaaa i dont know what to tag this#please reblog it though!#i spent. quite literally all day on this ;^^#like i had fun but also!!!! it was a lot of work!!

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Fayette in Les Misérables

Les Misérables is one of my absolute favourite books. I never get tired of it – funny coincidence, La Fayette is also in there. I have read the book in three different languages now and noticed that the amount of La Fayette varies in the different versions. The French original sets the precedent of course. The English translation (or, as there are of course several different translations, the English translation I read) featured La Fayette ten times (just as often as the French original). My two German translations feature La Fayette less often than the French and my English one. With that being said, I present to you the La Fayette-szenes in Les Misérables (Les Misérables by Victor Hugo, translated by Lee Fahnestock and Norman MacAfee, based on the translation by C. E. Wilbour, published by Signet Classics, 1987)

Courfeyrac had a father whose name was M. de Courfeyrac. One of the false ideas of the Restoration in point of aristocracy and nobility was its faith in the particle. The particle, we know, has no significance. But the bourgeois of the time of La Minerve considered this poor de so highly that men thought themselves obliged to renounce it. M. de Chauvelin became M. Chauvelin,.M. de Caumartin was M. Caumartin, M. de Constant de Rebecque simply Benjamin Constant, M. de Lafayette just M. Lafayette. Courfeyrac did not wish to be backward, and called himself simply Courfeyrac. (Marius, book four, The Friends of the ABC, p. 653)

So the bourgeoisie, as well as the statesmen, felt the need for a man who would say "Halt!" An Although-Because. A composite individuality signifying both revolution and stability; in other words, assuring the present through the evident compatibility of the past with the future. -This man was found ready-made. His name was Louis-Philippe d'Orleans. The 221 made Louis-Philippe king. Lafayette undertook the coronation. He called it "the best of republics." (Saint-Denis, book one, A few Pages of History, p. 829)

I can not give you a direct written example where La Fayette said “the best of republics” but the statement mirrors his early impressions on Louis-Phillipe’s reign perfectly.

These memories associated with a king fired the bourgeoisie's enthusiasm. With his own hands he had demolished the last iron cage of Mont-Saint-Michel, built by Louis XI and used by Louis XV. He was the companion of Dumouriez, he was the friend of Lafayette; he had belonged to the Jacobin Club; Mirabeau had slapped him on the shoulder; Danton had said to him, "Young man!" (Saint-Denis, book one, A few Pages of History, p. 834)

These doctrines, these theories, these resistances, the unforeseen necessity for the statesman to consult with the philosopher, confused evidences half seen, a new politics to create, in accord with the old world, and yet not too discordant with the ideal of the revolution; a state of affairs in which Lafayette had to be used to oppose Polignac, the intuition of progress glimpsed through the riots, the chambers, and the street, rivalries to balance around him, his faith in the Revolution, perhaps some uncertain eventual resignation arising from the vague acceptance of a definitive superior right, his desire to remain in his lineage, his family pride, his sincere respect for the people, his own honesty-all of this preoccupied Louis-Philippe almost painfully, and at times strong and as courageous as he was, overwhelmed him under the difficulties of being king. (Saint-Denis, book one, A few Pages of History, p. 841)

The distress of the people; laborers without bread; the last Prince de Conde lost in the darkness; Brussels driving away the Nassaus as Paris had driven away the Bourbons; Belgium offering herself to a French prince, and given to an English prince; the Russian hatred of Nicholas; at our back two demons of the south, Ferdinand in Spain, Miguel in Portugal; the earth quaking in Italy; Mettemich extending his hand over Bologna; France bluntly opposing Austria at Ancona; in the north some ill-omened sound of a hammer once more nailing Poland into its coffin; throughout Europe angry looks peering at France; England a suspicious ally, ready to push over anyone leaning and throw herself on anyone fallen; the peerage sheltering itself behind Beccaria to deny four heads to the law; the fteur-de-lis erased from the king's carriage; the cross tom down from Notre-Dame; Lafayette weakened; Lafitte ruined; Benjamin Constant dead in poverty; Casimir Perier dead from loss of power; the political disease and the social disease breaking out in the two capitals of the realm, one the city of thought, the other the city of labor; in Paris civil war, in Lyons servile war; in the two cities the same furnace glare; the flush of the crater on the forehead of the people; the South fanaticized, the West uneasy; the Duchesse de Berry in La Vendee; plots, conspiracies, uprising, cholera, added to the · dismal mutter of ideas, the dismal uproar of events. (Saint-Denis, book one, A few Pages of History, p. 843)

In an instant the little fellow was lifted, pushed, dragged, pulled, stuffed, crammed into the hole with no time to realize what was going on. And Gavroche, coming in after him, pushing back the ladder with a kick so it fell onto the grass, began to clap his hands, and cried, "Here we are! Hurrah for General Lafayette! Brats, my home!” Gavroche was in fact home. (Saint-Denis, book six, Little Gavroche, p. 956-957)

Hence, if insurrection in given cases may be, as Lafayette said, the most sacred of duties, émeute may be the most deadly of crimes. (Saint-Denis, book ten, June 5, 1832, p. 1052)

A circle was drawn up around the hearse. The vast assemblage fell silent. Lafayette spoke and bade farewell to Lamarque. It was a touching and noble moment, all heads uncovered, all hearts throbbed. Suddenly a man on horseback, dressed in black, appeared in the midst of the throng with a red flag, others say with a pike surmounted by a red cap. Lafayette looked away. Exelmans left the cortege. This red flag raised a storm and disappeared in it. From the Boulevard Bourdon to the Pont d'Austerlitz a roar like a surging billow stirred the multitude. Two prodigious shouts arose: "Lamarque to the Pantheon! Lafayette to the Hotel de Ville!" Some young men, amid the cheers of the throng, took up the harness and began to pull Lamarque in the hearse over the Pont d'Austerlitz, and Lafayette in a fiacre along the Quai Morland. In the cheering crowd that surrounded Lafayette, a German was noticed and pointed out, named Ludwig Snyder, who later died a centenarian, who had also been in the war of 1776, and who had fought at Trenton under Washington and under Lafayette at Brandywine. Meanwhile, on the left bank, the municipal cavalry was in motion and had just barred the bridge; on the right bank the dragoons left the Celestins and deployed along the Quai Morland. The men who were pulling Lafayette suddenly saw them at the bend of the Quai, and cried, "The dragoons!" The dragoons were advancing at a walk, in silence, their pistols in their holsters, their sabers in their sheaths, their muskets at rest, with an air of gloomy expectation. At two hundred paces from the little bridge, they halted. The fiacre bearing Lafayette made its way up to them, they opened their ranks, let it pass, and closed again behind it. At that moment the dragoons and the multitude came together. The women fled in terror. (Saint-Denis, book ten, June 5, 1832, p. 1059-1060)

Ludwig Snyder was a historical person who indeed existed and not a person that Hugo made up.

Alarming stories went the rounds, ominous rumors were spread. "That they had taken the Bank" ; "that, merely at thencloisters of Saint-Merry, there were six hundred, entrenched and fortified in the church"; "that the line was doubtful"; "that Armand Carrel had been to see Marshal Clausel and that the marshal had said, 'Have one regiment in place first,' " ; "that Lafayette was sick, but that he had said to them, 'I am with you. I will follow you anywhere that there is room for a chair' "; "that it was necessary to keep on their guard; that at night people would pillage the isolated houses in the deserted neighborhoods of Paris (the imagination of the police was recognized here, that Anne Radcliffe element in government)" ; "that a battery had been set up in the Rue Aubry-le-Boucher" ; "that Lobau and Bugeaud were conferring; and that at midnight, or daybreak at the latest, four columns would march at once on the center of the emeute, the first coming from the Bastille, the second from the Porte Saint-Martin, the third from La Greve, the fourth from Les Hailes"; "that perhaps the troops would evacuate Paris and fall back on the Champ de Mars"; "that nobody knew what might happen, but that certainly, this time, it was serious." (Saint-Denis, book ten, June 5, 1832, p. 1067-1068)

I could not find any historical reference about the chair-quote and I am pretty sure that Hugo made that up - however, it sounds very much like something that La Fayette would say - and Hugo and La Fayette probably knew each other, although superficially. Toward the end of La Fayette’s life, when Hugo was still a young men, there were different salons in Paris that both attended and it is quite likely that they both ran into each other during one of these meetings.

At this moment the bantam rooster voice of little Gavroche resounded through the barricade. The child had climbed up on a table to load his musket and was gaily singing the song then so popular:

En voyant Lafayette

Le gendarme repete

Sauvons-nous! Sauvons-nous! Sauvons-nous ! (Saint-Denis, book fourteen, The Grandeur of Despair, p. 1143)

This scene is not featured in my German version. It is mentioned that Gavroche sang a song but the text is not given in that translation.

They take you, they hold on to you, they never let go of you. The truth is, there was never any amour like that child. Now, what do you say of your Lafayette, your Benjamin Constant, and of your Tirecuir de Corcelles, who kill him for me ! It can't go on like this." (Jean Valjean, book three, Mire, but Soul, p. 1317)

La Fayette did not made it into the musical version of Les Misérables (neither in the French Original nor in the more popular English version) although he would have fit perfectly in there. I also have never seen him featured in any of the countless movie or TV adaptations - officially at least. Some adaptations that feature the funeral of General Lamarque have some extras running around that I sometimes turn into La Fayette - that was not the intended casting but it worked out for me nonetheless :-)

#lafayette#la fayette#marquis de lafayette#general lafayette#french revolution#french history#american history#american revolution#georges danton#louis philippe#victor hugo#les miserables#les miz#les mis#the brick#gavroche#louis xi#louis xv#mirabeau#1987#1776#brandywine#ludwig snyder#books#france#musical#general lamarque

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

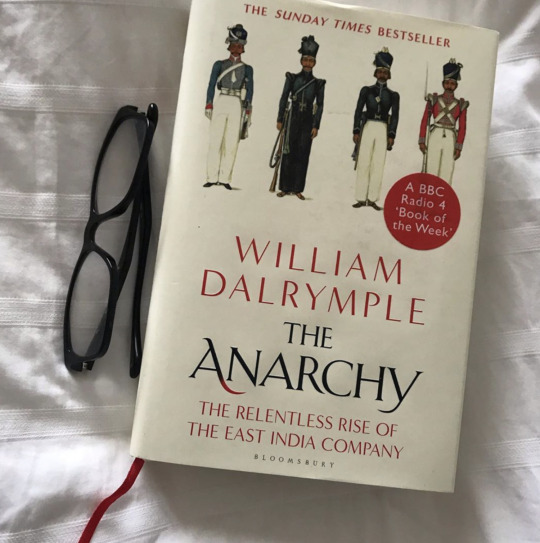

Treat Your S(h)elf: The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise Of The East India Company (2019)

It was not the British government that began seizing great chunks of India in the mid-eighteenth century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London, and managed in India by a violent, utterly ruthless and intermittently mentally unstable corporate predator – Clive.

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise Of The East India Company

“One of the very first Indian words to enter the English language was the Hindustani slang for plunder: loot. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this word was rarely heard outside the plains of north India until the late eighteenth century, when it became a common term across Britain.”

With these words, populist historian William Dalrymple, introduces his latest book The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. It is a perfect companion piece to his previous book ‘The Last Mughal’ which I have also read avidly. I’m a big fan of William Dalrymple’s writings as I’ve followed his literary output closely.

And this review is harder to be objective when you actually know the author and like him and his family personally. Born a Scot he was schooled at Ampleforth and Cambridge before he wrote his first much lauded travel book (In Xanadu 1989) just after graduation about his trek through Iran and South Asia. Other highly regarded books followed on such subjects as Byzantium and Afghanistan but mostly about his central love, Delhi. He has won many literary awards for his writings and other honours. He slowly turned to writing histories and co-founding the Jaipur Literary Festival (one of the best I’ve ever been to). He has been living on and off outside Delhi on a farmhouse rasing his children and goats with his artist wife, Olivia. It’s delightfully charming.

Whatever he writes he never disappoints. This latest tome I enjoyed immensely even if I disagreed with some of his conclusions.

Dalrymple recounts the remarkable rise of the East India Company from its founding in 1599 to 1803 when it commanded an army twice the size of the British Army and ruled over the Indian subcontinent. Dalrymple targets the British East India Company for its questionable activities over two centuries in India. In the process, he unmasks a passel of crude, extravagant, feckless, greedy, reprobate rascals - the so-called indigenous rulers over whom the Company trampled to conquer India.

None of this is news to me as I’m already familiar with British imperial history but also speaking more personally. Like many other British families we had strong links to the British Empire, especially India, the jewel in its crown. Those links went all the way back to the East India Company. Typically the second or third sons of the landed gentry or others from the rising bourgeois classes with little financial prospects or advancement would seek their fortune overseas and the East India Company was the ticket to their success - or so they thought.

The East India Company tends to get swept under the carpet and instead everyone focuses on the British Empire. But the birth of British colonialism wasn’t engineered in the halls of Whitehall or the Foreign Office but by what Dalrymple calls, “handful of businessmen from a boardroom in the City of London”. There wasn’t any grand design to speak of, just the pursuit of profit. And it was this that opened a Pandora’s Box that defined the following two centuries of British imperialism of India and the rise of its colonial empire.

The 18th-century triumph and then fall of the Company, and its role in founding what became Queen Victoria’s Indian empire is an astonishing story, which has been recounted in books including The Honourable Company by John Keay (1991) and The Corporation that Changed the World by Nick Robins (2006). It is well-trodden territory but Dalrymple, a historian and author who lives in India and has written widely about the Mughal empire, brings to it erudition, deep insight and an entertaining style.

He also takes a different and topical twist on the question how did a joint stock company founded in Elizabethan England come to replace the glorious Mughal Empire of India, ruling that great land for a hundred years? The answer lies mainly in the title of the book. The Anarchy refers not to the period of British rule but to the period before that time. Dalrymple mentions his title is drawn from a remark attributed to Fakir Khair ud-Din Illahabadi, whose Book of Admonition provided the author with the source material and who said of the 18th century “the once peaceful realm of India became the abode of Anarchy.” But Dalrymple goes further and tells the story as a warning from history on the perils of corporate power. The American edition sports the provocative subtitle, “The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire” (compared with the neutral British subtitle, “The Relentless Rise of the East India Company”). However I think the story Dalrymple really tells is also of how government power corrupts commercial enterprise.

It’s an amazing story and Dalrymple tells it with verve and style drawing, as in his previous books, on underused Indian, Persian and French sources. Dalrymple has a wonderful eye for detail e.g. After the Company’s charter is approved in 1600 the merchant adventures scout for ships to undertake the India voyage: “They have been to Deptford to ‘view severall shippes,’ one of which, the May Flowre, was later famous for a voyage heading in the opposite direction”.

What a Game of Thrones styled tv series it would make, and what a tragedy it unfolded in reality. A preface begins with the foundation of the Company by “Customer Smythe” in 1599, who already had experience trading with the Levant. Certain merchants were little better than pirates and the British lagged behind the Dutch, the Portuguese, the French and even the Spanish in their global aspirations. It was with envious eyes that they saw how Spain had so effectively despoiled Central America. The book fast-forwards to 1756, with successive chapters, and a degree of flexibility in chronology, taking the reader up to 1799. What was supposed to be a few trading posts in India and an import/export agreement became, within a century, a geopolitical force in its own right with its own standing army larger than the British Army.

It is a story of Machiavels from both Britain and India, of pitched battles, vying factions, the use of technology in warfare, strange moments of mutual respect, parliamentary impeachment featuring two of the greatest orators of the day (Edmund Burke and Richard Sheridan), blindings, rapes, psychopaths on both sides, unimaginable wealth, avarice, plunder, famine and worse. It is, in particular – because of the feuding groups loyal to the Mughals, the Marathas, the Rohilla Afghans, the so-called “bankers of the world” the Jagat Seths, and local tribal warlords – a kind of Game Of Thrones with pepper, silk and saltpetre. And that is even before we get to the British, characters such as Robert Clive “of India”, victor at the Battle of Plassey and subsequent suicide; the problematic figure of the cultured Warren Hastings, the whistle-blower who became an unfair scapegoat for Company atrocities; and Richard Wellesley, older brother to the more famous Arthur who became the Duke of Wellington. Co-ordinating such a vast canvas requires a deft hand, and Dalrymple manages this (although the list of dramatis personae is useful). There is even a French mercenary who is described as a “pastry cook, pyrotechnic and poltroon”.

When the Red Dragon slipped anchor at Woolwich early in 1601 to exploit the new royal charter granted to the East India Company, the venture started inauspiciously. The ship lay becalmed off Dover for two months before reaching the Indonesian sultanate of Aceh and seizing pepper, cinnamon and cloves from a passing Portuguese vessel. The Company was a strange beast from the start “a joint stock company founded by a motley bunch of explorers and adventurers to trade the world’s riches. This was partly driven by Protestant England’s break with largely Catholic continental Europe. Isolated from their baffled neighbours, the English were forced to scour the globe for new markets and commercial openings further afield. This they did with piratical enthusiasm” William Dalrymple writes. From these Brexit-like roots, it grew into an enterprise that has never been replicated “a business with its own army that conquered swaths of India, seizing minerals, jewels and the wealth of Mughal emperors. This was mercenary globalisation, practised by what the philosopher Edmund Burke called “a state in the guise of a merchant””.

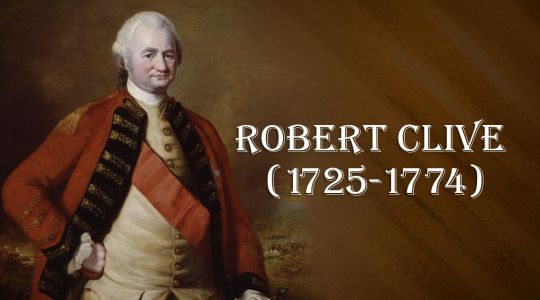

The East India Company’s charter began with an original sin - Elizabeth I granted the company a perpetual monopoly on trade with the East Indies. With its monopoly giving it enhanced access to credit and vast wealth from Indian trade, it’s no surprise that the company grew to control an eighth of all Britain’s imports by the 1750s. Yet it was still primarily a trading company, with some military capacity to defend its factories. That changed thanks to a well-known problem in institutional economics - opportunism by a company agent, in this case Robert Clive of India, who in time became the richest self-made man in the world in time.

Like many start-ups, it had to pivot in its early days, giving up on competing with the entrenched Dutch East India Company in the Spice Islands, and instead specialising in cotton and calico from India. It was an accidental strategy, but it introduced early officials including Sir Thomas Roe to “a world of almost unimaginable splendour” in India, run by the cultured Mughals.

The Nawab of Bengal called the English “a company of base, quarrelling people and foul dealers”, and one local had it that “they live like Englishmen and die like rotten sheep”. But the Company had on its side the adaptiveness and energy of capitalism. It also had a force of 260,000, which was decisive when it stopped negotiating with the Mughals and went to war. After the Battle of Buxar in 1764, “the English gentlemen took off their hats to clap the defeated Shuja ud-Daula, before reinstalling him as a tame ruler, backed by the Company’s Indian troops, and paying it a huge subsidy. “We have at last arrived at that critical Conjuncture, which I have long foreseen” wrote Robert Clive, the “curt, withdrawn and socially awkward young accountant” whose risk-taking and aggression secured crucial military victories for the Company. It was a high point for “the most opulent company in the world,” as Robert Clive described it.

So how was a humble group of British merchants able to take over one of the great empires of history? Under Aurangzeb, the fanatic and ruthless Mughal emperor (1658-1707), the empire grew to its largest geographic extent but only because of decades of continuous warfare and attendant taxing, pillaging, famine, misery and mass death. It was a classic case of the eventual fall of a great power through military over-extension.

At Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, a power struggle ensued but none could command. “Mughal succession disputes and a string of weak and powerless emperors exacerbated the sense of imperial crisis: three emperors were murdered (one was, in addition, first blinded with a hot needle); the mother of one ruler was strangled and the father of another forced off a precipice on his elephant. In the worst year of all, 1719, four different Emperors occupied the Peacock Throne in rapid succession. According to the Mughal historian Khair ud-Din Illahabadi … ‘Disorder and corruption no longer sought to hide themselves and the once peaceful realm of India became a lair of Anarchy’”.

Seeing the chaos at the top, local rulers stopped paying tribute and tried to establish their own power bases. The result was more warfare and a decline in trade as banditry made it unsafe to travel. The Empire appeared ripe to fall. “Delhi in 1737 had around 2 million inhabitants. Larger than London and Paris combined, it was still the most prosperous and magnificent city between Ottoman Istanbul and Imperial Edo (Tokyo). As the Empire fell apart around it, it hung like an overripe mango, huge and inviting, yet clearly in decay, ready to fall and disintegrate”.

In 1739 the mango was plucked by the Persian warlord Nader Shah. Using the latest military technology, horse-mounted cannon, Shah devastated a much larger force of Mughal troops and “managed to capture the Emperor himself by the simple ruse of inviting him to dinner, then refusing to let him leave.” In Delhi, Nader Shah massacred a hundred thousand people and then, after 57 days of pillaging and plundering, left with two hundred years’ worth of Mughal treasure carried on “700 elephants, 4,000 camels and 12,000 horses carrying wagons all laden with gold, silver and precious stones”.

At this time, the East India Company would have probably preferred a stable India but through a series of unforeseen events it gained in relative power as the rest of India crumbled. With the decline of the Mughals, the biggest military power in India was the Marathas and they attacked Bengal, the richest Indian province, looting, plundering, raping and killing as many as 400,000 civilians. Fearing the Maratha hordes, Bengalis fled to the only safe area in the region, the company stronghold in Calcutta. “What was a nightmare for Bengal turned out to be a major opportunity for the Company. Against artillery and cities defended by the trained musketeers of the European powers, the Maratha cavalry was ineffective. Calcutta in particular was protected by a deep defensive ditch especially dug by the Company to keep the Maratha cavalry at bay, and displaced Bengalis now poured over it into the town that they believed offered better protection than any other in the region, more than tripling the size of Calcutta in a decade. … But it was not just the protection of a fortification that was the attraction. Already Calcutta had become a haven of private enterprise, drawing in not just Bengali textile merchants and moneylenders, but also Parsis, Gujaratis and Marwari entrepreneurs and business houses who found it a safe and sheltered environment in which to make their fortunes”. In an early example of what might be called a “charter city,”

English commercial law also attracted entrepreneurs to Calcutta. The “city’s legal system and the availability of a framework of English commercial law and formal commercial contracts, enforceable by the state, all contributed to making it increasingly the destination of choice for merchants and bankers from across Asia”.

The Company benefited by another unforeseen circumstance, Siraj ud-Daula, the Nawab (ruler) of Bengal, was a psychotic rapist who got his kicks from sinking ferry boats in the Ganges and watching the travelers drown. Siraj was uniformly hated by everyone who knew him. “Not one of the many sources for the period — Persian, Bengali, Mughal, French, Dutch or English — has a good word to say about Siraj”. Despite his flaws, Siraj might have stayed in power had he not made the fatal mistake of striking his banker. The Jagat Seth bankers took their revenge when Siraj ud-Daula came into conflict with the Company under Robert Clive. Conspiring with Clive, the Seths arranged for the Nawab’s general to abandon him and thus the Battle of Plassey was won and the stage set for the East India Company.

In typical fashion, Dalrymple devotes half a dozen pages to the Company’s defeat at Pollidur in 1780 by Haider Ali and his son, Tipu, but a few paragraphs to its significance (Haider could have expelled the Company from much of southern India but failed to pursue his advantage). The reader is not spared the gory details.

“Such as were saved from immediate death,” reads a quote from a British survivor about his fellow troops, “were so crowded together…several were in a state of suffocation, while others from the weight of the dead bodies that had fallen upon them were fixed to the spot and therefore at the mercy of the enemy…Some were trampled under the feet of elephants, camels, and horses. Those who were stripped of their clothing lay exposed to the scorching sun, without water and died a lingering and miserable death, becoming prey to ravenous wild animals.”

Many further battles and adventures would ensue before the British were firmly ensconced by 1803 but the general outline of the story remained the same. The EIC prospered due to a combination of luck, disarray among the Company’s rivals and good financing.

The Mughal emperor Shah Alam, for example, had been forced to flee Delhi leaving it to be ruled by a succession of Persian, Afghani and Maratha warlords. But after wandering across eastern India for many years, he regathered his army, retook Delhi and almost restored Mughal power. At a key moment, however, he invited into the Red Fort with open arms his “adopted” son, Ghulam Qadir. Ghulam was the actual son of Zabita Khan who had been defeated by Shah Alam sixteen years earlier. Ghulam, at that time a young boy, had been taken hostage by Shah Alam and raised like a son, albeit a son whom Alam probably used as a catamite. Expecting gratitude, Shah Alam instead found Ghulam driven mad. Ghulam Qadir, a psychopath, ordered a minion to blind Shah Alam: “With his Afghan knife….Qandahari Khan first cut one of Shah Alam’s eyes out of its socket; then, the other eye was wrenched out…Shah Alam flopped on the ground like a chicken with its neck cut.” Ghulam took over the Red Fort and after cutting out the eyes of the Mughal emperor, immediately calling for a painter to immortalise the event.

A few pages on, Ghulam Qadir gets his just dessert. Captured by an ally of the emperor, he is hung in a cage, his ears, nose, tongue, and upper lip cut off, his eyes scooped out, then his hands cut off, followed by his genitals and head. Dalrymple out-grosses himself with the description of Ahmad Shah Durrani, the Afghan invader of India, dying of leprosy with “maggots….dropping from the upper part of his putrefying nose into his mouth and food as he ate.”

By 1803, the Company’s army had defeated the Maratha gunners and their French officers, installed Shah Alam as a puppet back on his imitation Peacock Throne in Delhi, and the Company ruled all of India virtually.

Indeed as late as 1803, the Marathas too might have defeated the British but rivalry between Tukoji Holkar and Daulat Rao Scindia prevented an alliance. “Here Wellesley’s masterstroke was to send Holkar a captured letter from Scindia in which the latter plotted with Peshwa Baji Rao to overthrow Holkar … ‘After the war is over, we shall both wreak our full vengeance upon him.’ … After receiving this, Holkar, who had just made the first two days march towards Scindia, turned back and firmly declined to join the coalition”.

For Dalrymple the crucial point was the unsanctioned actions of Robert Clive and the bullying of Shah Alam in the rise of the East India Company.

The Jagat Seths then bribed the company men to attack Siraj. Clive, with an eye for personal gain, was happy attack Siraj at the behest of the Jagat Seths even if the company directors had no part in this. They “consistently abhorred ambitious plans of conquest,” he notes. Clive’s defeat of Siraj at Plassey and the subsequent chain of events that led to Shah Alam giving tax-raising powers to the company in 1765 may be history’s most egregious example of the principal-agent problem.

Thus, the East India Company acquired by accident the ultimate economic rent — a secure, unearned income stream. Company cronies initially thwarted attempts at oversight in London, but a government bailout in 1772 following the Bengal Famine and the collapse of Ayr Bank confirmed the crown’s interest in the company, which had now become Too Big to Fail. Adam Smith called the company’s twin roles of trader and sovereign a “strange absurdity” in Book IV of The Wealth of Nations (unfortunately, Smith’s long condemnatory discussion of the company receives only a cursory reference from Dalrymple).

As part of the bailout, Parliament passed the Tea Act to help the company dump its unsold products on the American colonies by giving it the monopoly on legal tea there (Americans drank mostly smuggled Dutch tea). This, of course, led to the Boston Tea Party and the American Revolution.

By 1784, Parliament had set up an oversight board that increasingly dictated the company’s political affairs. The attempted impeachment of Governor-General Warren Hastings by the House of Lords in 1788 confirmed that the company was no longer its own master. By that stage, the company was an arm of the state. Dalrymple’s coverage of the subsequent racist policies of Lord Cornwallis and the military adventures of Richard Wellesley make for compelling reading, but they are not examples of unfettered corporate power.

Overlaid on top of luck and disorder, was the simple fact that the Company paid its bills. Indeed, the Company paid its sepoys (Indian troops) considerably more than did any of its rivals and it paid them on time. It was able to do so because Indian bankers and moneylenders trusted the Company. “In the end it was this access to unlimited reserves of credit, partly through stable flows of land revenues, and partly through collaboration of Indian moneylenders and financiers, that in this period finally gave the Company its edge over their Indian rivals. It was no longer superior European military technology, nor powers of administration that made the difference. It was the ability to mobilise and transfer massive financial resources that enabled the Company to put the largest and best-trained army in the eastern world into the field”.

Dalrymple pretty much loses interest once the Company gains full control. “This book does not aim to provide a complete history of the East India Company,” he writes. He skips past one mention of Hong Kong, which the East India Company seized after the opium wars in China. A few sentences record the 1857 uprising of Indian soldiers that led to the British government taking India from the Company and establishing the Raj that lasted until Indian independence in 1947.

The author makes passing reference to the fact that the struggle for American independence was underway for much of the period about which he writes. He notes that It was British East India Company tea that patriots dumped into Boston harbor in 1773. American colonists were so grateful that the Mysore sultans tied up British forces that might have been deployed in America, they named a warship the Hyder Ali. Lord Cornwallis provides a connection, having surrendered to George Washington at Yorktown in 1781, an event confirming American independence, and turning up in 1786 in India as governor-general, taking Tipu Sultan’s surrender in 1792.

That reference raises an interesting side question that may someday deserve closer examination - Why were American colonists successful in driving off their British overlords. At the same time, Indian aristocracy and the masses over whom they ruled were unable to rid themselves of the British East India Company and the British Raj for another century?

No heroes emerge from Dalrymple’s expansive account that is rich, even overwhelming in detail. He covers two centuries but focuses on the period between 1765 and 1803 when the Company was transformed from a commercial operation to military and totalitarian — to use an appropriate term derived from Sanskrit - juggernaut. Among the multitude of characters involved in this sordid story are a few British names familiar in general history, Robert Clive of India, Warren Hastings, Lord Cornwallis, and Colonel Arthur Wellesley, who was better known long after he departed India as the Duke of Wellington. None - with the exception of Hastings - escape the scathing indictment of Dalrymple’s pen.

At the core of the story we meet Robert Clive, an emblematic character who from being a juvenile delinquent and suicidal lunatic rose to rule India, eventually killing himself in the aftermath of a corruption scandal. In particular Robert Clive comes in for much criticism by Dalrymple. After putting down one rebellion, Clive managed to send back £232 million, of which he personally received £22m. There was a rumour that, on his return to England, his wife’s pet ferret wore a necklace of jewels worth £2,500. Contrast that with the horrors of the 1769 famine: farmers selling their tools, rivers so full of corpses that the fish were inedible, one administrator seeing 40 dead bodies within 20 yards of his home, even cannibalism, all while the Company was stockpiling rice. Some Indian weavers even chopped off their own thumbs to avoid being forced to work and pay the exorbitant taxes that would be imposed on them. The Great Bengal famine of 1770 had already led to unease in London at its methods. “We have murdered, deposed, plundered, usurped,” wrote the Whig politician Horace Walpole. “I stand astonished by my own moderation,” Clive protested, after outrage intensified when the Company had to be bailed out by the British government in 1772. Clive took his own life in disgrace.

Warren Hastings, whom Dalrymple portrays as the more sensitive and sympathetic Company man, was first made governor general of India for 12 years and later endured seven years of impeachment for corruption before acquittal. Hastings showed “deep respect” for India and Indians, writes, Dalrymple, as opposed to most other Europeans in India to suck out as much as possible of the subcontinent’s resources and wealth. “In truth, I love India a little more than my own country,” wrote Hastings, who spoke good Bengali and Urdu, as well as fluent Persian. “(Edmund) Burke had defended Robert Clive (first Governor General of Bengal) against parliamentary enquiry, and so helped exonerate someone who genuinely was a ruthlessly unprincipled plunderer. Now he directed his skills of oratory against Warren Hastings (who was finally impeached), a man who, by virtue of his position, was certainly the symbol of an entire system of mercantile oppression in India, but who had personally done much to begin the process of regulating and reforming the Company, and who had probably done more than any other Company official to rein in the worst excesses of its rule,” Dalrymple writes. At his public impeachment hearing in 1788, Burke thundered: “We have brought before you…..one in whom all the frauds, all the peculation, all the violence, all the tyranny in India are embodied.’ They got the wrong man but, by the time he was cleared in 1795, the British state was steadily absorbing the Company, denouncing its methods but retaining many of its assets.

Dalrymple has a soft spot for a couple of Indian locals. “The British consistently portrayed Tipu as a savage and fanatical barbarian,” Dalrymple writes, “but he was in truth a connoisseur and an intellectual…” Of course, Tipu, Dalrymple confesses a bit later, had rebels’ “arms, legs, ears, and noses cut off before being hanged” as well as forcibly circumcising captives and converting them to Islam.

Emperor Shah Alam (1728-1806) is contemporary for much of the time Dalrymple covers. “His was…a life marked by kindness, decency, integrity and learning at a time when such qualities were in short supply…he…managed to keep the Mughul flame alive through the worst of the Great Anarchy….” Dalrymple portrays a most intriguing figure in Emperor Shah Alam, a man attracted to mysticism and yet as prepared as his contemporaries to double-deal; someone who endures exile and torture and who outlives, albeit in a melancholy fashion, his enemies. Despite his lack of wealth, troops or political power, the very nature of his being emperor still, it seems, inspired affection.

Part of Dalrymple’s excellence is in the use of Indian sources – he takes numerous quotes from Ghulam Hussain Khan, acclaimed by Dalrymple as “brilliant,” who threads the story as an 18th-century historian on his untranslated works, Seir Mutaqherin (Review of Modern Times). Dalrymple has used a trove of company documents in Britain and India as well as Persian-language histories, much of which he shares in English translation with the reader. However he does this a bit too often and portions of his account can seem more assembled than written.

These pages are also brimming with anecdotes retold with Dalrymple’s distinctive delight in the piquant, equivoque and gory: we have historical moments when “it seemed as if it were raining blood, for the drains were streaming with it” (quoted from a report c1740 regarding events that preceded Nadir Shah’s infamous looting of the peacock throne) as well as duels between Company officials so busy with their in-fighting that it’s a miracle they could perform their work at all; there’s also homosexuality, homophobia, sexual torture, castrations, cannibalism, brothels and gonorrhoea.

The principal protagonists of the “Black Hole of Calcutta” incident are both, naturally, certified pervs: Siraj ud-Daula is a “serial bisexual rapist” while his opponent Governor Drake is having an “affair with his sister”. And one particular Mughal governor liked to throw tax defaulters in pits of rotting shit (“the stench was so offensive, that it almost suffocated anyone who came near it”). All this gives one a rough idea of what historically important people were up to according to Dalrymple. But all things considered, Dalrymple’s research is solid and heavily annotated.

However entertaining and widely researched using unused Urdu and Persian sources, Dalrymple’s overall approach doesn’t tell us very much about the general tendency in eighteenth-century imperial activity, and particularly that of the British, that we didn’t already know. And other things he downplays or neglects. Thus, the East India Company was one of a series of ‘national’ East India companies, including those of France, the Netherlands and Sweden. Moreover, for Britain, there was the Hudson Bay Company, the Royal African Company, and the chartered companies involved in North America, as well, for example, as the Bank of England. Delegated authority in this form or shared state/private activities were a major part of governance. To assume from the modern perspective of state authority that this was necessarily inadequate is misleading as well as teleological. Indeed, Dalrymple offers no real evidence for his view. Was Portuguese India, where the state had a larger role, ‘better’?

Secondly, let us look at India as a whole. There is an established scholarly debate to which Dalrymple makes no ground breaking contribution. This debate focuses on the question of whether, after the death in 1707 of the mighty Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707), the focus should be on decline and chaos or, instead, on the development of a tier of powers within the sub-continent, for example Hyderabad. In the latter perspective, the East India Company (EIC) emerges as one and, eventually, the most successful of the successor powers. That raises questions of comparative efficiency and how the EIC succeeded in the Indian military labour market, this helping in defeating the Marathas in the 1800s.

An Indian power, the EIC was also a ‘foreign’ one; although foreignness should not be understood in modern terms. As a ‘foreign’ one, the EIC was not alone among the successful players, and was not even particularly successful, other than against marginal players, until the 1760s. Compared to Nadir Shah of Persia in the late 1730s (on whom Michael Axworthy is well worth reading), or the Afghans from the late 1750s (on whom Jos Gommans is best), the EIC was limited on land. This was part of a longstanding pattern, encompassing indeed, to a degree, the Mughals. Dalrymple fails to address this comparative context adequately.

Dalrymple seems particularly incensed at “corporate violence” and in a (mercifully short) final chapter alludes to Exxon and the United Fruit Company. Indeed Dalrymple has a pitch ” that globalisation is rooted here, albeit that “the world’s largest corporations…..are tame beasts compared with the ravaging territorial appetites of the militarised East India Company.”

It is an interesting question to ask: How might the actions of these corporate raiders have differed from those of a state? It’s not clear, for example, that the EIC was any worse than the average Indian ruler and surely these stationary bandits were better than roving bandits like Nader Shah. The EIC may have looted India but economic historian Tirthankar Roy explains that: “Much of the money that Clive and his henchmen looted from India came from the treasury of the nawab. The Indian princes, ‘walking jeweler’s shops’ as an American merchant called them, spent more money on pearls and diamonds than on infrastructural developments or welfare measures for the poor. If the Company transferred taxpayers’ money from the pockets of an Indian nobleman to its own pockets, the transfer might have bankrupted pearl merchants and reduced the number of people in the harem, but would make little difference to the ordinary Indian.”

Moreover, although it began as a private-firm, the EIC became so regulated by Parliament that Hejeebu (2016) concludes, “After 1773, little of the Company’s commercial ethos survived in India.” Certainly, by the time the brothers Wellesley were making their final push for territorial acquisition, the company directors back in London were pulling out their hair and begging for fewer expensive wars and more trading profits.

So also for eighteenth-century Asia as a whole. Dalrymple has it in for the form of capitalism the EIC represents; but it was less destructive than the Manchu conquest of Xinjiang in the 1750s, or, indeed, the Afghan destruction of Safavid rule in Persia in the early 1720s. Such comparative points would have been offered Dalrymple the opportunity to deploy scholarship and judgment, and, indeed, raise interesting questions about the conceptualisation and methodologies of cross-cultural and diachronic comparison.

Focusing anew on India, the extent to which the Mughal achievement in subjugating the Deccan was itself transient might be underlined, and, alongside consideration, of the Maratha-Mughal struggle in the late seventeenth century, that provides another perspective on subsequent developments. The extent to which Bengal, for example, did not know much peace prior to the EIC is worthy of consideration. It also helps explain why so many local interests found it appropriate, as well as convenient, to ally with the EIC. It brought a degree of protection for the regional economy and offered defence against Maratha, Afghan, and other, attacks and/or exactions. The terms of entry into a British-led global economy were less unwelcome than later nationalist writers might suggest. Dalrymple himself cites Trotsky, who was no guide to the period. To turn to other specifics is only to underline these points.

After Warren Hastings’ impeachment which in effect brought to an end the era when “almost all of India south of [Delhi] was…..effectively ruled by a handful of businessmen from a boardroom in the City of London.” It is hard to find a simple lesson, beyond Dalrymple’s point that talk of Britain having conquered India ‘disguises a much more sinister reality’.

One of the great advantages non-fiction has over fiction is that you cannot make it up, and in the case of the East India Company, you cannot make it up to an extent that beggars belief. William Dalrymple has been for some years one of the most eloquent and assiduous chroniclers of Indian history. With this new work, he sounds a minatory note. The East India Company may be history, but it has warnings for the future. It was “the first great multinational corporation, and the first to run amok”. Wryly, he writes that at least Walmart doesn’t own a fleet of nuclear submarines and Facebook doesn’t have regiments of infantry.