#tectonics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

are there any pokemon fans with a special interest in geology or tectonics out there? for nerd reasons, i need to know how Mt. Coronet formed, what its vague characteristics might be, and generally what this implies for the geography of Sinnoh as a whole. thank you!

#pokemon#pokemon legends arceus#pokemon dppt#pla#pokémon diamond#pokémon pearl#pokemon platinum#pokémon platinum#pokemon diamond#pokemon pearl#pokemon bdsp#brilliant diamond#shining pearl#tectonics#Geology#Mt. Coronet#Mount Coronet

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

this bad boy took me forever to make and was such a pain... but i'm glad i finished it. a flow chart to show the tectonic history! i basically named all the different major islands and continents (as seen in this video), and charted out how they split (when arrows come from a name) and collide (when arrows point to a name). red landforms exist in the "modern" period!

#worldbuilding#world building#worldbuilder#speculative worldbuilding#writers of tumblr#writers on tumblr#writing#writeblr#plate tectonics#tectonics#geology#geography

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nickelus F - Tectonics

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tectonic shifting

#art#artist#artists on tumblr#modern art#contemporary art#abstract#abstract art#abstraction#abstract composition#mosaic#tectonics#tectonic shifts#plate tectonics

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Förstberg Ling clads "introspective" extension with charred pine)

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Incredible Footage of the Volcanic Eruption in Iceland

On December 18, a volcano surfaced on Iceland's Reykjanes peninsula, near Grindavik and the Blue Lagoon. This event marked the awakening of volcanoes in the region after an eight-century dormancy.

The emergence was triggered by the movement of the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates pulling apart.

Preceding the eruption, the area had been experiencing earthquakes for two months. Due to concerns that the volcano might surface under Grindavik, a town with nearly four thousand residents, evacuation measures were implemented on November 10.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tectonic plate under Tibet may be splitting in two | Science | AAAS

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

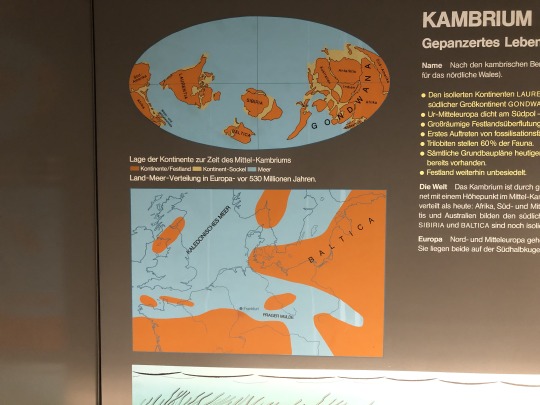

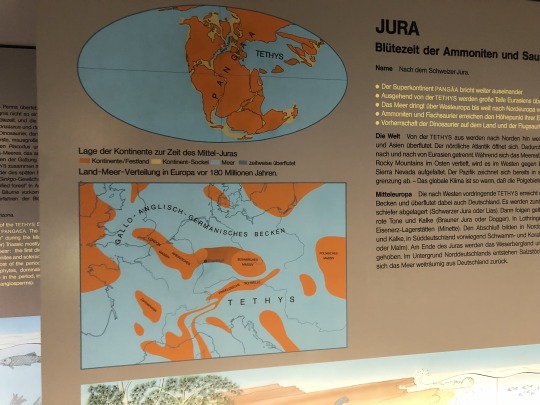

World maps and local maps of northwestern Europe from across the Phanerozoic. This room also had a big world map on a screen with a kind of ship's wheel you could turn to go back and forth in time. It went all the way back to 750 million years ago (a little while before the first Snowball Earth) and all the way forward to 250 million years hence (when all our continents will have collided and formed Pangea Proxima).

#tectonics#maps#palaeoblr#senckenberg museum#continental drift#it's really cool to see what my home area was like over different times#it's kind of funny that they made sure to tactically crop spain out of the local maps#if you look at the global maps you can see it was 'broken off' from the rest of europe before the late cretaceous

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coupling of Tectonics, Climate, and Lithology in Orogenic Systems: Insights From Cosmogenic 10Be Erosion Rates and River Profile Inversion Modeling in the Talesh Mountains, NW Iranian Plateau

Key Points

Tectonics, and to a lesser extent climate, control erosion rates, which are twice as high on the wetter eastern flank of the Talesh Mountains

Low-erodibility rocks favored the preservation of relict landscapes, while high-erodibility rocks led to equilibrated landscapes

Rock uplift rates increased at ∼12–10 Ma, peaking at ∼4 Ma during the Caspian Sea base-level fall due to thrusting and mantle inflow processes

#Topography#rainfall#wedge#increased rainfall can lead to a stationary huh....#Tectonics#Climate#Lithology#climate change#Iranian#Plateau#research

0 notes

Text

Lewerentz, Technician

The architecture of Sigurd Lewerentz is usually understood as almost uniquely powerful and meaningful among the work of the modernist period. His buildings, particularly the two late churches of the 1960s, St Mark's and St Peter's, are seen as highly idiosyncratic and enigmatic. The landscape of the Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm is also seen as evidence of his genius. He spoke little about his work, preferring not to deviate from the architect's established sacred route between drawing board and building site. He has been talked about because of his silence; mythologization of his persona started before his death, and he can now be said to be famous for being famous, apart from anything else.

I want to argue that, rather than creating buildings that are full of symbolism and meanings waiting to be discovered, Lewerentz had a spirit which is best described as technical. His work is consistently concerned with components, systems and technique, from the way he articulated classical elements at the Chapel of the Resurrection, to the unorthodox brick construction methods of the late churches, and finally to his transformation of plain electrical wiring into an ornamental motif in the flower kiosk at the cemetery in Malmo. In each case he worked by carefully manipulating the disposition of predetermined components. This way of working is reflective of modernity, the aesthetics of mass production and the new realities of building craft over Lewerentz's lifetime.

Colin St John Wilson noted the very slight adjustment that Lewerentz made to the orientation of the portico of the 1925 Uppståndelsekapellet, claiming that it made a crucial difference between a "formally very banal" plan and one that is architecturally successful. Wilson's comment is plausible, but, as others have pointed out, the "banal" option is the one taken by the one of the canonical (if somewhat aberrant) buildings of classicism, the Erechtheion on the Acropolis. What is more, the slight angle Lewerentz created between the portico and body of the chapel is barely perceptible from ground level (another early Lewerentz chapel has been described as having "a skewed plan form. ... the skew is clear on the floor plan but barely perceptible in reality."

Peter Blundell Jones describes the situation as follows:

The noble portico, set on the axis of the Way of Seven Wells, the longest straight route on the site, is detached from the chapel, whose orientation follows the axis of the sunken west garden. The two axes are not normal but 2° out, and rather than concealing this fact like most architects, Lewerentz played it up through the skewed disjunction of the two buildings. This gesture makes all the difference, for it shows that the parts are separate entities, their relationship not self-contained but given by the place.

There is in fact a story behind the alignment which illustrates Lewerentz's stubbornness.

An earlier, rejected design for the chapel had entirely aligned on the north-south axis, with entrances at both ends. This peculiar pipeline principle (enter from the north, exit to the south) combined with the unorthodox orientation of the chapel (most Christian churches and chapels are aligned east-west with the altar at the east end) was considered too innovative.

So I don't think we should attribute this rotation of one of the components of the chapel to its material program (to the concept). Lewerentz wasn't making an articulated object for the sake of it. Instead, I see the rotation and skewing of the plan as being determined by an overarching concern for alignment with the axes of the cemetery landscape in which the chapel sits. The alignment is "given by the place". It should be seen as evidence of resistance, of a refusal to give up on the original plan.

It has been observed that Asplund (Lewerentz's collaborator on the Woodland Cemetery) was interested in the "formal attributes of individual species of plants" while Lewerentz focused "on the contrasting moods evoked by each [tree] type". Lewerentz here is cast as someone more concerned with the grid of a plantation, with the intervals between the rows of trees, with the space between the trunks rather than the shape of a bud or leaf. From someone with such a focus, aligning the elements of a building with the lines implicit in a planted landscape is a very understandable move.

This aspect of Lewerentz's design philosophy is evident in the cemetery at Kvarnsveden. In this two-page spread, the drawing shows exquisitely delineated grids of burial plots defining an orientation of the space around the chapel, which itself resembles an Asplund design of a couple of years earlier.

It is clear that Lewerentz's early work evidenced a concern with defining and conforming to grids and orientations. In contrast with Asplund's "quick and intuitive" design process, Lewerentz was said (by Hakon Ahlberg) to be "more systematic".

The extant drawings reveal their contrasting working methods: while Lewerentz engaged in a lengthy process of methodically studying alternative proposals, probing details and avoiding final decisions, Asplund pursued a more intuitive approach that was at once quick and well organized.

An emblematic difference between the two designers is the shape of the internal space in Asplund's Woodland Chapel and Lewerentz's chapel at Kvarnsveden. The former is a perfect hemispherical dome, the latter an equally precise cylindrical barrel vault. As Janne Ahlin puts it "Asplund's appealing, not to say persuasive art of fabulation is replaced with a cool, sharply delineated quality—mute, and enclosed." Asplund is made to look like a charismatic traditionalist in comparison with Lewerentz's hard-headed modern precision. What is surprising is that Asplund is understood here to be the one interested in morphology, while Lewerentz is concerned more with psychology. Both are formalists, to a degree—we're aware that we are in the presence of architecture as a product of the drawing board.

In the middle years of his career, Lewerentz was engaged in designing and manufacturing metal windows. He did not design buildings in this period, but it doesn't take much looking to discern a "cool, sharply delineated quality" in the Idesta windows for which he was responsible.

When Lewerentz returned to architectural practice, late in life, he undertook a challenging project of reforging the tectonics of brick construction. The first product of this endeavour was the church of St Mark at Björkhagen.

Much is made of the fact that Lewerentz freely chose to restrict himself to only using whole bricks of a standard size. The bricks were to be used intact, without cutting. This constraint was a spur to creativity. I'm tempted to contextualise it with a remark that was made about a ship designed around the same time:

"Such a departure from common practice, such a refusal to accept precedent for convention's sake shows great confidence and courage."

It was certainly a bold move—although the fact that Lewerentz also gave himself a new freedom by allowing the width of the mortar joints to vary made his task easier.

The wide perpends, full of mortar, caused Florian Beigel to describe this type of construction as a concrete with bricks as the aggregate. I don't think this metaphor, or the geological terms conglomerate or breccia, capture the discipline Lewerentz had established for himself. What is evident throughout the church of St Mark is that the surface of the building is flat and defined by the faces of bricks. The vaulted roof, which essentially uses the jack arch technique, is composed of developable surfaces (surfaces with single curvature). Just as Lewerentz chose a cylindrical vault instead of a dome at Kvarnsveden, he avoided double-curved surfaces in St Mark's. This flatness, the quality of all surfaces being curved in such a way that they could be wallpapered, has a penetrating effect on the architecture of the church. It results in a kind of stiff spatial logic, and, to me at least, the feeling of a technical exercise rather than a great achievement; a minor excellence rather than a magnum opus. Commentators who see the building as full of "effects" and "solutions" seem to be ignoring this pervasive structural quality. (There is an exception to this regime of developed surfaces, in the form of the lone beehive dome that was constructed in the trees a few tens of meters away the church.)

The church of St Peter in Klippan, built a few years later, is a more fully developed example of Lewerentz's new brick architecture. Here the essential constraints of the brick system are fully worked out and exhibited. The difficulties manifest themselves most strongly when building something with a dimension of between 2 and 3 brick lengths. A set of four skylight towers are executed in contrasting styles: a matrix-like grid and an interlaced bond. On one level this is just pattern-making; on another Lewerentz is poetically expressing the problems of his self-inflicted constructional system.

It's impossible not to invoke Mies van der Rohe's observation:

“How sensible is this small handy shape, so useful for every purpose! What logic in its bonding, pattern, and texture! What richness in the simplest wall surface! But what discipline this material imposes!”

For every constraint, Lewerentz seems to allow himself a counterbalancing freedom. The perpends (vertical joints between horizontally laid bricks) are allowed to skew from one course to the next, creating an effect not unlike knitting. In fact, the overall materials aesthetic of the late churches should be compared with chunky knitwear or thick corduroy. It is a matter of fashioning, in a positive sense, not a frivolous one.

The slightly decorative profile of the vaults at Klippan might be compared to the profile of a bundt cake. The building is a block, apparently carved (or machined) from a single material, according to a strict description (no double curvature, unlike the cake tin which produced this cake!)

The jack arch brick vaults in St Peter's do not span the whole space. They need two huge steel purlins to support them near the centre. These purlins are supported in turn by a T-shaped structure made of girders, which has something of the appearance of a temporary prop used in mining or tunnelling. Why did Lewerentz choose this structural strategy? We don't know.

Tony Fretton, one of the most intelligent, serious and straight-talking British architects of the last few decades, has quoted Colin St John Wilson's perceptive commentary on this design feature. For Wilson and Fretton, Lewerentz's building is not inexplicable and enigmatic. The result may be mysterious (all architecture is) but the story of its construction is not. Wilson writes:

The strange instinct by which Lewerentz, apparently only concerned with the dogged working out of an issue of building construction, arrives at the figure, pregnant with symbolic meaning, its form irresistibly evoking the form of the cross with a harshness for which we are completely unprepared.

This is admirably accurate and direct. Admittedly, Wilson does allow himself to mystify Lewerentz's process, but stresses the "fact" that it involved a technical requirement, rather than an enigmatic will to art:

The fact is that a technical requirement is transformed into a haunting metaphor, and how this is brought about is unfathomable.

Elsewhere, he writes of the T-shaped structure as

[A] form that irresistibly recalls the central symbol of both the New and the Old Testament — the Tree of Knowledge and the Cross of Redemption.

Now there's one symbol instead of two. Only a theologian could say whether this polysemy is liturgically sound. Since I'm not interested in meanings,I don't believe it is a necessary aspect of the architecture. The other major feature of St Peter's, a gap in the swelling brick floor which marks the baptismal font, seems to elude such explanations. It is just what it is.

Any clerical assessment of Lewerentz's work is a matter of opinion. Churchmen are human, susceptible to vanity and elitism in their desire to build for posterity. The decision to build Lewerentz's brutalist church was controversial at the time. Compare Claude Parent and Paul Virilio's contemporary Sainte-Bernadette-du-Banlay in Nevers. According to Virilio, the commissioner, Monseignor Vial, chose it because it was hated by the public:

“The other project being considered,” he told me, “is a small chapel with little angels, but there is so much hatred for your project, this pile of concrete, that I am going to choose it.”

In Lewerentz's case, the thesis (Adversus Populum) of the priest Lars Riddenstedt (who was involved in the commissioning of both of the late brick churches) is advanced by defenders as evidence of the appropriateness of his buildings as churches. Most architects, though, don't care, and seem to be more interested in sacrilegiously worshipping the architect.

Lewerentz did not call himself a brutalist, but his late work resembles brutalism in one very important respect. The term was adopted by architects as "something between a slogan and a brickbat flung in the public's face". It has resulted in lasting public confusion (people thinking it is a derogatory term), attesting to the obscure motivations behind it. In short, it was a measure intended to combat vapidity in architecture, and this is the characteristic it seems to share with Lewerentz's work. It's ironic that so much of the 21st century appreciation of his late buildings is itself vapid, concerned only with the wholegrain aesthetics of his work. What I find interesting is that this focus on the superficial seems to comport perfectly with a view of Lewerentz as concerned primarily with technique. Lewerentz's reticence might come from a similar attitude to Andy Warhol's: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There's nothing behind it.”

It's not right to categorize Lewerentz's late work as either joyless (a morose exercise in the machine aesthetic), nor cheesy (a "medieval" masterpiece of "divine darkness"). Both characterizations attribute more of a definite mood to his designs than they actually contain. They attribute to his work the significance of existential seriousness ot high religious art.

The reality of the work is best illustrated by a detail of his last project, the flower kiosk for the cemetary in Malmo.

The detail in question is the way Lewerentz makes a precise pattern on the concrete wall using standard electrical wire and plain light fittings. The mundane materials, mass-produced (just like the bricks at Klippan and Björkhagen) are arranged to create an infrastructural gesture. The bare lightbulbs are not pretty (there's no chance of kitsch in Lewerentz's world) and the result is not representative of anything. The diagram created on the wall is not unlike the primary route in the Woodland Cemetery, the Way of the Seven Wells. Here we have lightbulbs instead of wells, connected by wires instead of a path. Their multiplicity is pragmatic and they are interchangeable. There's no meaning, just a poetics of technical construction.

0 notes

Link

In this episode of SpaceTime, we delve into the latest findings that are reshaping our understanding of how Earth's continents formed, a major breakthrough in subatomic particle measurements, and a new SpaceTime telescope set to study the cosmic dawn and the ultimate fate of our universe. Join us for these fascinating updates and more! 00:00:00 - This is spacetime series 27, episode 99 for broadcast on the 16 August 2024 00:00:45 - New study pokes holes in leading theories of continental formation 00:03:49 - Neutrinos are fundamental to the standard model of particle physics 00:05:53 - Scientists have detected high energy neutrinos from the Large Hadron Collider 00:16:37 - The World Health Organisation has issued a warning about a new superbug 00:18:39 - Reports growing that UK is running out of ghosts For more SpaceTime, visit our website at www.spacetimewithstuartgary.com www.bitesz.com Become a supporter of this podcast: https://www.spreaker.com/podcast/spacetime-with-stuart-gary--2458531/support

#archean#collider#continents#cosmic#dawn#earth's#formation#grace#hadron#interactions#large#measurements#nancy#neutrino#particle#plate#roman#subatomic#tectonics#zircons

0 notes

Video

youtube

Nickelus F Bars On I-95 Freestyle

youtube

Nickelus F - Tectonics

youtube

NICKELUS F - DUMP YOU IN A RIVAH (official video) - FEATURING THE STUDIO 4 DANCE AGENCY.

0 notes

Text

#conner kent#clark kent#superman#kal el#kon el#superfam#fic rec#tectonics series by selkienight60#You’re the freakin’ sun and I’m just some space rock pulled in by accident

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

markhelly nation, we're eating SO GOOD next week

#RAGE! BETRAYAL!#this being a tectonic reveal for mark!#markhelly#severance#severance spoilers#adam scott#britt lower#mark s#helly r#mark scout#helena eagan#mimi.txt#markhelena#markhellyna

496 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Architect Fredrik Nilsson clads his Los Angeles house in oiled cedar)

13 notes

·

View notes