#taiping rebellion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Women warriors in Chinese history - Part 1

“In the nomadic tribes of the foreign princesses from the Steppes northwest to the northeast of the Chinese borders, women habitually rode horses and were frequently also skilled militarily. They had to be able to survive on their own and defend themselves when their men left camp to herd animals for months on end. Thus, unsurprisingly, many daughters of nomadic and semi-nomadic tribal chiefs were also capable fighters. Madam Pan 潘夫人 of “barbarian origins” during the Wei dynasty, the semi-barbarian Princess Pingyang 平陽公主 who helped establish the Tang dynasty, and the “barbarian queen,” Empress Dowager Xiao, are historical examples of this category of female generals.

While the barbarians to the north were known as fan 番, those belonging to peripheral areas from the southwest to the southeast were known as man 蠻. Like the nomadic princesses, these women of non-Chinese or Chinese ethnic minority groups did not bind their feet and could thus become formidable opponents. Indeed, the female battle units within the Taiping 太平 rebel forces that actually entered combat – rather than merely providing labour as most of the female units did –were reportedly made up in the main of women from the Miao 苗 tribes, aside from the Hakka (Kejia 客家) women of Guangxi.

Female bandit leaders or daughters and sisters of bandit leaders who occupied mountains or established strongholds in marginal lands are almost indistinguishable from the man barbarian princesses of tribal chieftains in novels and shadow plays. Such barbarian women generals and female bandit leaders were rarely privileged enough to be recorded by the historians. The three found most frequently, Madam Xi 洗夫人 (502– 557), Madam Washi 瓦氏夫人 (1498–1557),95 and Madam Xu 許夫人 (1271–1368), were all pro-Chinese. While the first two cooperated with the Chinese government, the third joined Chinese forces against the Mongols. A certain Zhejie 折節 or Shejie 蛇節, a female leader of the Miao tribe, also led a rebellion against Mongol troupes, but she eventually surrendered to them and was subsequently executed.

Real enemies of the Chinese empire, such as the Trv’vy sisters of Vietnam, are hardly ever mentioned by the Chinese, even though they are first recorded in the Han dynastic history. Even under such circumstances, of the women commanders in Chinese history studied by Xiaolin Li, a hefty per cent were from “minor nationalities.”

Female rebel leaders and women warriors in rebel forces tended to rise from peasantry and marginal groups such as families of itinerant performers, robbers, boatmen, and hunters. Many of them are beautiful and charismatic. Most of the rebel groups were basically bandits (known as haohan 好漢, “bravos” euphemistically) – how else could they have survived without a continuous source of income? Many of the bandit groups, like the sworn brothers of the Water Margin, lived in mountains and marshlands, awaiting a chance to start or join in an uprising with the hope of gaining power and legitimacy through either pardon (when they posed too great a threat to the state) or founding a new dynasty. Many had sisters, wives, or daughters who were also capable of leading armies.”

Chinese shadow theatre: history, popular religion, and women warriors, Fan Pen Li Chen

#history#women in history#warrior women#women's history#historyblr#warriors#quotes#women warriors#china#chinese history#asian history#Princess Pingyang#empress dowager chengtian#lady washi#taiping rebellion#trung sisters

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

HONG XUANJIAO // GENERAL

“She was a Chinese female general and rebel leader during the Taiping Rebellion. She was said to be the younger sister of the leader of Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, Hong Xiuquan, and is the wife of Xiao Chaogui, the West King. She led women into the battlefield against the Qing dynasty for the Taiping cause.”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're not big into martial arts, you might not have heard of sanda, originally created as CQC for Chinese soldiers. It's often decried by just about everyone as being, essentially...just MMA rather than having roots in traditional Chinese kung fu.

That's only half-accurate. I'll explain why, but I need to catch you up the nearly one hundred years before it's creation for context.

(CW for war crimes, brief mention of sexual assault, mention of Native American oppression, and political cartoons with a racist depictions of Asians - and as always, if someone knows better, please correct me)

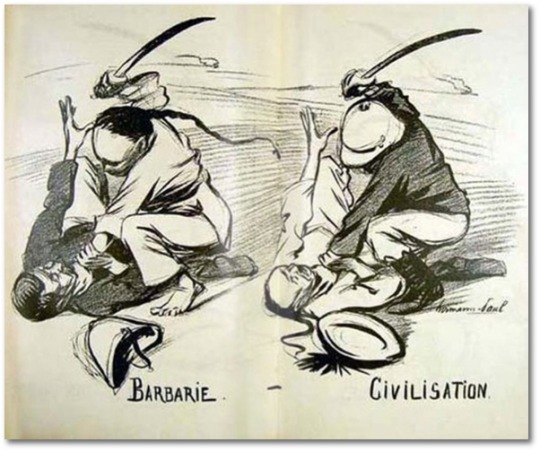

The first thing you need to understand is the Century of Humiliation, a concept in Chinese historiography. The premise is that China was regularly fucked over from the 1840s to the 1940s when the communists took full control of the mainland. While this is a narrative heavily pushed by Chinese nationalism, it's not exactly wrong - they had it pretty bad, and thought not exclusively the fault of foreigners, a lot of it was, including the two Opium Wars where England and France wrecked China's shit for the right to keep the drug trade going. The Second Opium War is where the UK first got Kowloon, which would be followed later by the rest of what would become Hong Kong.

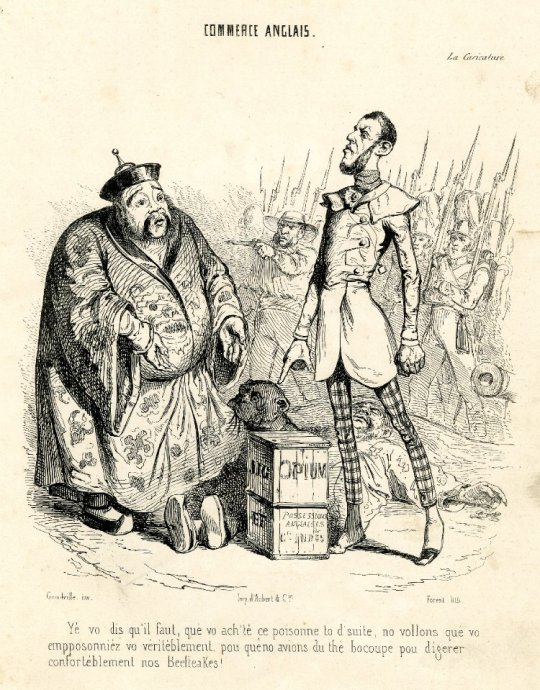

English Commerce

I tell you to immediately buy the gift here. We want you to poison yourself completely, because we need a lot of tea in order to digest our beefsteaks.

The Taiping Rebellion, from 1850 to 1864, is estimated to have cost up to about 30 million lives, compared to the American Civil War's 700 thousand. And let me tell you, it's crazy we don't talk more about the Taiping Rebellion, not only because of the devastation but because the rebels were a very strange branch of Chinese Christian that believed their leader to be the brother of Jesus Christ. Which...well, I guess that's also technically the West's fault, although Western Christians were heavily divided on how they felt about the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, and ultimately after some indecision and putting feelers out to the rebels, the West chose to back the Qing.

For the people who love the DDR because their enforcement of laws were not always necessarily the worst in the entire world for queer folk: the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was spectacularly feminist for it's time, way more than East Germany was pro-queer! Maybe consider switching over to Chinese Christofascism?

(I'm sorry, I'm going to be angry about that literally forever)

China would go on to badly lose the Sino-French War and Japanese-Sino War, the two together resulting in China losing suzerainty (essentially control of foreign affairs) over Vietnam and Korea, and a lot of their influence outside their own borders.

At this point, you can start to see how China was being treated by the West...and Imperial Japan, who, as we've discussed, were great big westaboos. Everyone wanted a piece, and it was a race to get the biggest. They didn't think in terms of what China wanted, they hardly considered themselves in opposition with China, but rather each other.

Putting His Foot Down Uncle Sam: Gentlemen, you may cut up this map as much as you like, but remember that I'm here to stay, and you can't cut me up into spheres of influence!

Needless to say, the Chinese were...not pleased with how things were going.

The traditional narrative is that the Qing's modernization efforts were, at best, a very mixed-success. There's been more questioning of that, though, since "modernization" is inherently kinna a Eurocentric term with arbitrary values. Just before the Japanese-Sino War, everyone was pretty certain "modernization" had gone great and they were going to crush Japan like ants. The Qing did face issues with corruption and firing shells that had their high-explosives siphoned to be sold off, but considering Russia has had to deal with essentially the same problem in Ukraine finding their reserve tanks to be hollow tin cans, I'd say that's fairly modern.

Social instability would continue to rapidly worsen after losing the First Sino-Japanese War, during which Japanese acts of brutality were enough, as I mentioned in my previous historical post, to elicit at least temporary scandal among the Western Powers Imperial Japan hoped so desperately to impress. Tensions were especially high with Christian missions, culminating in an incident in which two German missionaries were killed in an attempt to kill a third accused of rape. That led to Germany invading and taking away yet another piece of China's sovereign territory. Not helping things was that, because of special protections for the practice of Christianity forced on China by treaties from those prior conflicts, many bandits were "converting" or claiming to have done so in order to escape the law. And all of this is in the midst of serious natural disasters ruining lives and leaving people with nothing.

So that brings us to 1899, the main point of this post, and something you may have only heard of before in a throwaway line on Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I'm talking about the Boxer Rebellion.

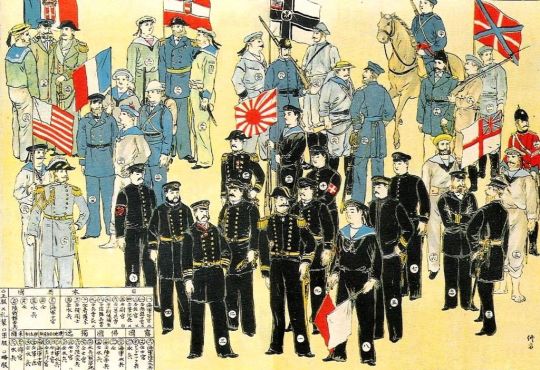

It was then that an escalating series of murders against Christians (missionaries and converts) and attacks on telegraph wires and railroads blossomed into something like but not quite a revolution, the most notable event being the Siege of Peking (Beijing), where over two thousand Christians and foreign civilians took refuge until the formation of the Eight-Nation Army, an alliance of Italy, Russia, the United States, the UK, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Japan, Germany, and France, invaded to rescue them.

You might assume that "Boxer" came from someone's name, or a major location, or something like that, right? The name actually conceals the reason I find the Boxer Rebellion so interesting, and why we're talking about it today. See, back then, kung fu was referred to as "Chinese boxing" in the West.

The Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists were just one extralegal organization that flourished in late 1800s thanks to the Qing slowly losing their grip on governing even within some parts of their own territory. They weren't just anti-foreigners, they started out pissed at the Qing for the ongoing troubles, and fighting government control is where they got their start. Yet, they famously used the battle cry "support the Qing, destroy foreigners" - hey, wasn't this supposed to be a rebellion by an extralegal organization?

Ha - well - while she initially condemned them, Empress Dowager Cixi would later throw in with the Fists, at least partly because the prince stanned them so hard he met with her wearing one of their uniforms. This, it seemed, was a legitimate path to expelling all foreigners.

So, right now you're probably thinking back to where this post started. The natural conclusion at this point is that the Fists surely lost, but their martial arts were impressive, right? And then that became sanda?

Well.

No.

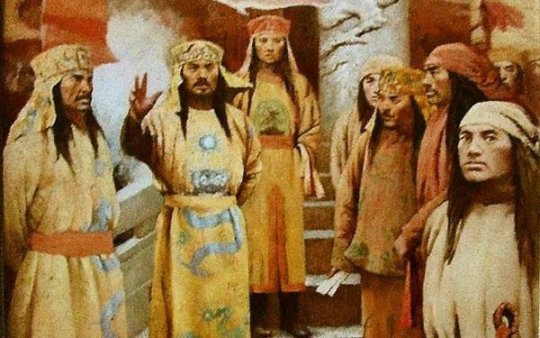

The movie Boxer Rebellion (1975) depicts martial artists jumping into crowds of armed soldiers and devastating them with the awesome power of kung fu. You might expect this to exaggeration typical of action movies, and it is, kinna. It's also only half of what the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists thought they were capable of.

The Fists believed their kung fu made them invulnerable to blades and bullets, including cannonballs. They thought they could fly. They thought ghost warriors would descend from the sky to help drive out foreign armies. Though they had some firearms, they were mostly armed with blades if anything at all. The Empress ordered the Qing military to assist them, but generals wisely chose to do the bare minimum or outright ignore the command entirely.

Even stranger was the legends that grew around the Red Lanterns. You can think of the Lanterns as a kinna women's auxiliary to the Fists, who spurned women lest they "pollute" their masculine magic kung fu and cause it to fail. The Lanterns were divided by age between Black Lanterns (older women), Blue Lanterns (middle-aged women), and most famously, the Red Lanterns, who were eleven to seventeen.

Like the Fists, Red Lanterns possessed magical powers. They could fly, but also, unlike the Fists, walk on water and stop guns, among other things. When Catholic women were accused of making that masculine kung fu magic fail by exposing themselves, the Fists resolved to wait for the Red Lanterns to arrive, since their magic would be immune to corrupting femininity.

I want to take a moment to say I know how all this sounds, and I've tried to keep my language serious at least in this section because I don't mean to paint the Fists as "stupid" for the things they believed. It's important to keep in mind the Fists were largely peasants driven by nationalistic fervor and desperation from how bad things had gotten thanks to foreigners, natural disasters, and the Qing's own corruption and internal failures. It's depressingly reminiscent of ghost shirts, which just ten years prior had failed to stop bullets during Wounded Knee. The population was despondent and angry, with little still left to lose. That led them to kill innocent people prior to dying themselves to an enemy they never had a chance against. People like Mark Twain, Leo Tolstoy, and others outright took the Fists' side at least in terms of "who started it".

More often than not, history is sad.

So the Boxers lost, badly. Empress Dowager Cixi was given a pass for siding with them because she was more useful on the throne than off it, but the Qing would fall about a decade later in the middle of trying once again to further "modernize". China fell a free-for-all between warlords, ultimately coming down to the Kuomintang's Republic of China and the Chinese Communist Party. The two would (barely) work together to resist Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War, which quickly became part of World War II. Soon after they fell back into conflict, with the Kuomintang forced to retreat to Taiwan and still claims independence that the PRC still denies.

In Taiwan is the Republic of China Military Academy, which was known as the Whampoa Military Academy when it developed sanda in the mid-20s. It is, basically, MMA. Traditional martial artists certainly played a part in it's early history, but they were doing what Bruce Lee would fiercely advocate for decades later - "absorb what is useful, discard what is not". Foreign combat sports, like Muay Thai and (actual, Western) boxing were worked in as well. Like in MMA, a background in traditional martial arts can be helpful going in, but you're going to have to learn a lot more and probably unlearn several things as well. The biggest influence was actually the lei tai, raised platforms where Chinese brawlers engaged brutal and often fatal matches, sometimes with weapons even. Like, people had organs come out on the lei tai, it was nuts.

The reason MMA and sanda look so similar is that that's just what comprehensive and effective fighting looks like. It's the same reason England doesn't use gyroget ammo for their guns while Germany equips their soldiers with fully automatic crossbows. In video games, which I love with all my heart, fighting styles as diverse as sumo and capoeira are presented as more or less equally balanced, with different advantages and disadvantages. That's not how it works. We solved the optimal way to hold your arms and it's not like this.

You may have heard of Xu Xiaodong, a Chinese man trained in sanda who has a history of fighting and handedly winning against supposed masters of kung fu. The PRC hates him for that because, like with pseudoscientific traditional Chinese medicine, kung fu is a useful promoter of nationalism, and it's better at that if it keeps it's mystique as impenetrable as possible.

I would probably like a lot of modern Chinese martial arts movies if not knowing that they were bankrolled to be propaganda for the PRC, like the first Ip Man, which exists to further the myth of wing chun and remind everyone that Japan sucks for what happened during WWII. I don't think they're making many movies about the Boxer Rebellion.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

wonder if china freaks out whenever anyone mentions jesus because he gets flashbacks to hong xiuquan.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

We've had a lot of books based on Christian mythology with angels and Lucifer and shit

I want one based on Taiping Christian mythology. I want to see Confucius as a villain leading humanity astray

I want Jesus' Chinese brother to come down from heaven and murk some dudes.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ah yes, hong xiuquon, the man who failed his exams so badly that he became convinced he was the younger brother of jesus fucking christ

#china#chinese history#hong xiuquon#qing dynasty#taiping rebellion#this feels like a crackfic#but nope#it's real#talk about overcompensation#jfc

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a fun history thing I found out recently!

It's often said that "WW2 was the most deadly war in history! Totally and absolutely there is no doubt about this don't even look it up!"

However this is only maybe true!

It's possible that WW2 was only the second most deadly war in history, possibly rivaled by the Taiping Rebellion of 1850.

As far as I can tell it's hard to say exactly how many people died in the Taiping Rebellion, but the higher estimates reach up to 70 million people. Possibly betting WW2's death toll of 60 million by a full 10 million people.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

REVIEW: God's Chinese Son - The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan (1996)

A Book by Jonathan Spence The Nineteenth Century was a tumultuous time in Chinese history, marked by a series of significant events that ultimately led to the collapse of the Qing Dynasty only a few years into the following century. These events, such as the appearance of Christian missionaries in China, encroaching Western Imperialism, the numerous Opium Wars, the Boxer Rebellion and more…

View On WordPress

#(1996)#book#book review#China#Chinese#Chinese History#Class Assignment#Games#Gods#heavenly#History#hong#Jonathan Spence#kingdom#Review#son#Taiping#Taiping Rebellion#the#xiuquan

0 notes

Text

I fucking love learning about Chinese history because on one hand it's reading the coolest battles ever, and on the other, it's reading about some general that did the most wildest and backward strategic decision that has ever graced upon this earth and ended up actually working.

#Chinese history#Do NOT ask me about the Taiping Rebellion because you cannot convince me everybody that startes it was bullshiting their way throughout#and it all ended up working

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

SU SANNIANG // REBEL

“She was a Chinese rebel during the Taiping Rebellion. The leader of a band of outlaws, she joined the rebellion with a band of 2000 soldiers.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was ABSOLUTELY NOT a metaphor. Hong Xiuquan claimed to be the second son of God.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

貴方だけを憶えている 雲の影が流れて往く 言葉だけが溢れている 想い出は夏風、揺られながら

#今日の気分は#songs about having a weird relationship with someone's memory in the summer!!!!#aka the topic of pretty much yorushika's entire discography#today the person whose memory I'm having a weird relationship with is Hong Xiuquan :)#'the leader of the Taiping Rebellion?' yeah I'm making syllabi. being super hinged and normal#(I will take any excuse to talk about the Taiping Rebellion as my students can attest)#music#yorushika#music video

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love when the ancient apocalypse weirdos are also like 'and the bible is literally true and everything in the bible literally happened' everything? even the stuff that contradicts the chinese annals?

#.din#.txt#okay i just googled it. in fairness it is. sigh.#in fairness. noah did his thing apparently RIGHT BEFORE yu the great quelled the flood. so.#new theology: the bible is literally true its just that the other half is in china.#taiping rebellion...........two!

0 notes

Note

Are you planning to cover occult traditions in China or Chinese alchemy at all, in the book? Because there's stuff like the Taiping Rebellion and the White Lotus societies where the occult has heavily figured into Chinese history?

I want to learn about eastern religions more, but to cover them in the book would effectively add +4 years of research and development.

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

I see people are finding out about the Taiping Rebellion for the first time in the notes of that Falun Gong post so yes, there really was a civil war in China started by a Christian millenarian cult led by a guy who said he was Jesus' baby brother that killed half as many people as WW2 and 10-20% of the population of China in pre-industrial warfare. 30 million people killed with muskets, cannons, swords, and knives. As far as I can tell there isn't even a single photograph of it. It's one of the most traumatic events and destructive wars in human history and basically nobody knows about it outside of China. It's nuts.

925 notes

·

View notes