#Chinese history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Haha isn't it so interesting that regimes in Chinese history have had a 250-year upper limit before needing a hard reset of some kind in the form of rebellions or capital sackings. Also ANYONE can receive the new Mandate of Heaven and become the new emperor, even peasants.

(Some dynasties will appear to have lasted like 400 or 700 years upon surface-level Googling, but look deeper and you'll find that they're always split up, like Western / Eastern Han or Western / Eastern Zhou)

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hanfu in the style of the Tang dynasty. This hanfu makes me want to dance and whirl around :-)

chinese hanfu by 重回汉唐

#A Full Moon & Blooming Flowers#actress#cdrama#chinese drama#chinese historical clothing#chinese clothes#chinese historical clothes#chinese actress#cdramaedit#chinese actor#hanfu aesthetic#chinese aesthetic#china#cdramasource#chinese drama aesthetic#chinese history#ancient china#ancient chinese clothes#ancient chinese clothing#chinese clothing#chinese aesthetics#hanfu aesthetics#hanfu#tang dynasty#tang dynasty aesthetic#tang dynasty hanfu#tang dynasty clothes#tang dynasty clothing#chinese fashion#guzhuang

462 notes

·

View notes

Text

-listening from behind the curtain- aka honey are you HEARING this? me: do you think empress dowager lü zhi utilized girl power?

me 2.0: hell yeah!

me: do you think empress dowager lü zhi effectively utilized girl power by killing political rivals on her husband's behalf, brutally mutilating her husband's consort in a jealous rage, poisoning said consort's son, and usurping her own children/grandchildren's throne to rule as the first (defacto) female empress in chinese history, an act which eventually snowballed into the lü clan uprising and almost destroyed the fledgling empire she helped her husband build?

me 2.0: god forbid women do anything U_U the more that i think about it, the more im convinced it will be more impactful if we never see lü zhi's face at all. it pulls double-duty in representing the societal attitudes towards warring states women, where they are both hidden treasures to be jealously guarded by men, and also forced into the obliterating void of obscurity by those same men who smother their talents and ignore their achievements. well-behaved women rarely make history, and sister, lü zhi is about to have her name engraved in stone...

right: Lacquerware screen of Prince of Nanyue (reconstruction), China, Han dynasty left: Mawangdui lacquer screen, China, Han dynasty. han dynasty screens were made of wood not silk, so im evoking artistic license: _________________________________ | Artistic Liscence | | Name: its-not-a-pen | | Valid until: 4/28 | | the holder is entitled to [3] | | anachronisms per year | ----------------------------------——-- close ups and wips (the thing liu bang is holding in his hands are carved walnut shells, basically ye olde fidget toys)

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

《苦昼短》 唐 · 李贺

飞光,飞光,劝尔一杯酒。

吾不识青天高黄地厚,唯见月寒日暖,来煎人寿。

食熊则肥,食蛙则瘦。

神君何在,太一安有?

天东有若木,下置衔烛龙。

吾将斩龙足,嚼龙肉,使之朝不得回,夜不得伏。

自然老者不死,少者不哭。

何为服黄金,吞白玉?

谁似任公子,云中骑碧驴。

刘彻茂陵多滞骨,嬴政梓棺费鲍鱼。

(punctuation added by me)

"Short Bitter Days" Tang Dynasty, Li He

Oh fleeting time, may you drink this cup of wine. I do not know how high the blue sky, nor how thick the yellow earth, I only see the cold of the moon and warmth of the sun (the days and seasons passing), wearing away our lifetimes.

Those who eat bear grow fat, those who eat frogs become thin.

Where are the gods, is there truly a heavenly emperor?

In the east of the sky there is a celestial arbor*, beneath it the zhulong**.

(*) borrowing this translation from hsr because hsr chinese also sometimes uses 若木 to refer to the 建木 as both terms refer to a massive mythical tree

(**) mythical dragon that controls the day night cycle

I shall cleave the dragon's feet, and eat the dragon's flesh, so it cannot fly during the day nor rest at night.

Thus the old will not die, and the young will not weep.

What use is there in eating yellow gold or swallowing white jade?

Who can be like Master Ren, riding through the clouds on a white/green* donkey? (*) there exists some debate on if this is supposed to be white or green in this line

Liu Che's* grave at Maoling is full of withered bones, Ying Zheng's** catalpa coffin wasted many abalone.

(*) Liu Che was the 7th emperor of the Han Dynasty, living from 156 to 87 BCE, and his gravesite is called Maoling. He was interested in seeking immortality.

(**) Ying Zheng was the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty, and really the first emperor in Chinese history, responsible for uniting all the warring states and establishing the imperial system that would last for over two millennia after his life from 259 to 210 BCE. He died while touring the nation, suspected foul play by one of his sons trying to usurp the throne, and to keep his death hidden while they were returning to the capital his coffin (emperor's coffins were traditionally made of catalpa wood) was covered in abalone to hide the stench of his slowly rotting corpse.

Another poem I had previously read but didn't understand fully. Li He wrote this poem during the Yuanhe era (806-820 CE) of the Tang Dynasty's Xianzong Emperor Li Chun's rule. At the time Li Chun was extremely obsessed with obtaining immortality himself, to the point where he even famously appointed an alchemist as a provincial governor. Naturally whatever the emperor is interested in, the entire court is interested in in order to gain his favor. Knowing this historical background it's very clear what Li He was criticizing.

I also think this poem is a good concrete example of the Chinese attitude towards divinity. I believe @999-roses at one point showed a xhs post in which a Chinese user was asking why Westerners didn't have any stories about fighting their gods, whereas Chinese mythology is full of examples of characters fighting against the highest gods, most famously the three "rebels of heaven" Sun Wukong (the Monkey King), Nezha, and Yang Jian (Er Lang Shen). Many coastal regions had temples to the dragon kings who were believed to control the rain, however during long droughts people in some regions have a tradition of taking the dragon king's statue out of the temple and exposing it to the harsh sunlight, and even whipping it to give the offending gods a taste of the pain they inflict on the people by denying them rain. In this poem Li He is proclaiming he will slay and eat the dragon that controls the day night cycle (and by extension the normal passage of time) and bring immortality to all.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok guys am i stupid for feeling like folding chairs were a modern thing? i saw this folding chair from the 16th century in the ming dynasty and it's blowing my mind

not that they'd be difficult to manufacture im sure they could've made one a thousand years ago, thinking about it now. it's just like, in my dumb lizard brain you'd never invent the folding chair without first inventing the enormous auditorium conference hall for mediocre businessmen yk

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

I can feel the spring vibes already by enjoying the soft colors of this beautiful hanfu :-)

shan qun by 香染衣罗传统服饰

#A Full Moon & Blooming Flowers#actress#cdrama#chinese drama#chinese historical clothing#chinese clothes#chinese historical clothes#chinese actress#cdramaedit#chinese actor#hanfu aesthetic#chinese aesthetic#china#cdramasource#chinese drama aesthetic#chinese history#ancient china#ancient chinese clothes#ancient chinese clothing#chinese clothing#chinese aesthetics#hanfu aesthetics#hanfu#tang dynasty#tang dynasty aesthetic#tang dynasty hanfu#tang dynasty clothes#tang dynasty clothing#guzhuang#chinese fashion

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Bronze Sword With An Inlaid Rock Crystal, Turquoise and Gold Hilt Warring States Period, Circa 4th - 2nd Century B.C.

#Chinese Bronze Sword With An Inlaid Rock Crystal Turquoise and Gold Hilt#Warring States Period#Circa 4th - 2nd Century B.C.#bronze#bronze sword#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient china#chinese history#chinese art#art

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Men's beauty practices in imperial China

English added by me :)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

So. My Chinese History prof just stopped in the middle of his lecture, stared at all of us, and just asks "Does anyone here listen to The Magnus Archives?" and proceeded to use TMA and Smirke's 14 *TO EXPLAIN NEO-CONFUCIANIST THOUGHT DURING THE SOUTHERN SONG.* When I tell you I jumped I'm?????????????????

#tma#the magnus archives#tma podcast#tma shitpost#china#chinese history#southern song#history#confucianism#confucius#i never thought i would have to tag tma and confucius in the same post but here we are i guess

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some cute autumn vibes...

CHEN ZHUOXUAN 陈卓璇 in hanfu | 2024 National Style Ceremony

Chen Zhuoxuan: more photos here 2024 National Style Ceremony: more photos here

#A Full Moon & Blooming Flowers#actress#cdrama#chinese drama#chinese historical clothing#chinese clothes#chinese historical clothes#chinese actress#cdramaedit#chinese actor#hanfu aesthetic#chinese aesthetic#china#cdramasource#chinese drama aesthetic#chinese history#ancient china#ancient chinese clothes#ancient chinese clothing#chinese clothing#chinese aesthetics#hanfu aesthetics#hanfu#tang dynasty#tang dynasty aesthetic#tang dynasty hanfu#tang dynasty clothes#tang dynasty clothing#chinese fashion#guzhuang

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Porcelein turtle vessel, China, early 16th century

from The Ayala Museum, Manila

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

The "Empress Regnant Wu killed her own baby to frame a rival" allegation is so annoying to defend against because it's not even that I want to be like "NO SHE WOULD NEVER KILL A BABY!!" but because the story makes no sense. The earliest historical records just say the baby died suddenly and yet tellings of it CENTURIES later start gaining in detail and character motivation?

Also even if she did kill the baby, male emperors kill their children all the time and nobody blinks, yet we're supposed to be so extra scandalized when a female emperor does it that it becomes the defining event of her life?

#empress regnant wu#chinese history#chinese history thoughts#> becomes the only female emperor in Chinese history#> everyone remembers you for an obviously fake baby killing story#smh heavens forbid women have hobbies

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Luohan Temple 罗汉寺 is a Buddhist temple located in Chongqing city, China. It is the site of the Buddhist Association of Chongqing.

This temple was built by a prominent monk Zuyue 祖月 in the Zhiping period (1064–1067) of the Song Dynasty (960–1276). At that time it was called "Zhiping Temple".

The temple was renovated and expanded in the following Ming and Qing dynasties, and also during the ROC and PRC eras.

#china#🇨🇳#chinese heritage#chinese culture#chinese architecture#Sichuan#Chongqing#Sichuan province#chinese#people’s republic of china#prc#chinese history#sino#Chinese temples#Chinese Buddhism#Chinese Buddhist temple#temples#Chinese Buddhist architecture#Chongqing architecture#Sichuan architecture#Buddhism#song dynasty#architecture#han chinese#chinese houses

547 notes

·

View notes

Text

--Written Chinese vs English--

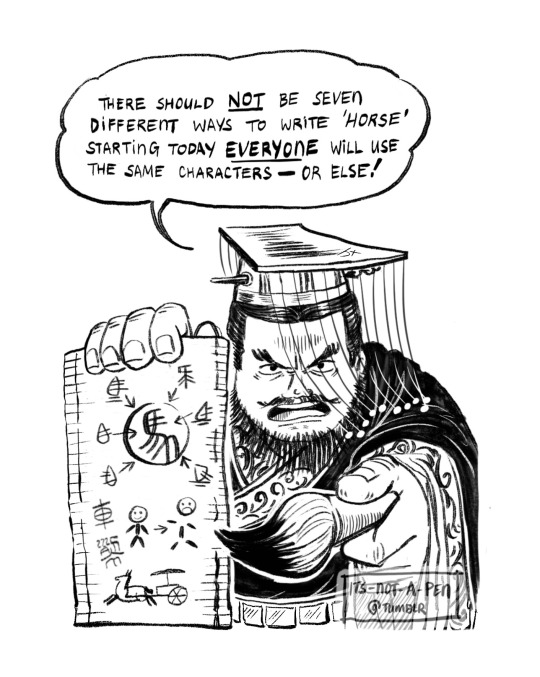

[ID: A comic titled "Evolution of Written Chinese vs English". On the left, emperor Qin Shi Huang holds up a scroll and angrily points an ink brush at the viewer and shouts, "There should not be seven different ways to write 'horse'. Starting today everyone will use the same characters-- or else!" On the right, William Shakespeare laughs gleefully while holding a skull and quill and exclaims, "The first rule of English is to have fun and to thine own self be true!" Every word uses a non-standard spelling. Below the cut are full versions of the the panels and a blank version of the Chinese one. End ID]

I'm fascinated by the evolution of chinese and english "spelling." I grew up on hard-to-read Ye Olde English, and assumed all languages were like that. Imagine my shock when I discovered the chinese language had been standardised since 221BC, and I can read words written in the Han Dynasty.

full versions:

notes under the cut

For much of it's history, the English language played it fast and loose with spelling. (No one can spell things wrong if no one can spell things right!) Standardisation only began in the late 15th century as the use of the printing press spread across Europe.

I thought the best person to show this carefree attitude was the Bard himself; Willy Shakes. We have six surviving examples of Shakespeare's signature, and none of them are spelled the same way twice.

In comparison, Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, standardised the writing system as early as 221 BC. He had conquered the six warring states and decided to do away with their writing systems. This made the administration of a centralised government easier, and it served as a demonstration of his absolute authority. The writing on the book* is "horse", and "torn apart by carriage".

**That scroll he's holding is actually called a book in Chinese, it is made up of bamboo slips, like a big sushi mat!

All designs are available on redbubble: I thought it would be fun to include a blank version of qin shi huang, so you can write stuff on him.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Beijing through the eyes of Bruno Barbey. 1970-80s.

485 notes

·

View notes