#surrender of ulm

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Allegory of the Surrender of Ulm, 20th October 1805

Artist: Antoine François Callet (French, 1741–1823)

Date: n. d.

Medium: Oil painting

Description

Allegorie de la Reddition d'Ulm; General Karl Mack (1752-1828) surrendering to Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821); capitulation of Austrian army to French.

#allegorical art#allegorical scene#oil painting#painting#general karl mack#napoleon bonaparte#austrian army#surrender#artwor#fine art#narrative art#chariot#horses#bright light#male figures#female figures#sword#shield#army#warriors#capitulation#french culture#french art#antoine francoise callet#european art

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 8.19 (before 1930)

295 BC – The first temple to Venus, the Roman goddess of love, beauty and fertility, is dedicated by Quintus Fabius Maximus Gurges during the Third Samnite War. 43 BC – Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, later known as Augustus, compels the Roman Senate to elect him Consul. 947 – Abu Yazid, a Kharijite rebel leader, is defeated and killed in the Hodna Mountains in modern-day Algeria by Fatimid forces. 1153 – Baldwin III of Jerusalem takes control of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from his mother Melisende, and also captures Ascalon. 1458 – Pope Pius II is elected the 211th Pope. 1504 – In Ireland, the Hiberno-Norman de Burghs (Burkes) and Cambro-Norman Fitzgeralds fight in the Battle of Knockdoe. 1561 – Mary, Queen of Scots, aged 18, returns to Scotland after spending 13 years in France. 1604 – Eighty Years War: a besieging Dutch and English army led by Maurice of Orange forces the Spanish garrison of Sluis to capitulate. 1612 – The "Samlesbury witches", three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury, England, are put on trial, accused of practicing witchcraft, one of the most famous witch trials in British history. 1666 – Second Anglo-Dutch War: Rear Admiral Robert Holmes leads a raid on the Dutch island of Terschelling, destroying 150 merchant ships, an act later known as "Holmes's Bonfire". 1692 – Salem witch trials: In Salem, Province of Massachusetts Bay, five people, one woman and four men, including a clergyman, are executed after being convicted of witchcraft. 1745 – Prince Charles Edward Stuart raises his standard in Glenfinnan: The start of the Second Jacobite Rebellion, known as "the 45". 1745 – Ottoman–Persian War: In the Battle of Kars, the Ottoman army is routed by Persian forces led by Nader Shah. 1759 – Battle of Lagos: Naval battle during the Seven Years' War between Great Britain and France. 1772 – Gustav III of Sweden stages a coup d'état, in which he assumes power and enacts a new constitution that divides power between the Riksdag and the King. 1782 – American Revolutionary War: Battle of Blue Licks: The last major engagement of the war, almost ten months after the surrender of the British commander Charles Cornwallis following the Siege of Yorktown. 1812 – War of 1812: American frigate USS Constitution defeats the British frigate HMS Guerriere off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada earning the nickname "Old Ironsides". 1813 – Gervasio Antonio de Posadas joins Argentina's Second Triumvirate. 1839 – The French government announces that Louis Daguerre's photographic process is a gift "free to the world". 1848 – California Gold Rush: The New York Herald breaks the news to the East Coast of the United States of the gold rush in California (although the rush started in January). 1854 – The First Sioux War begins when United States Army soldiers kill Lakota chief Conquering Bear and in return are massacred. 1861 – First ascent of Weisshorn, fifth highest summit in the Alps. 1862 – Dakota War: During an uprising in Minnesota, Lakota warriors decide not to attack heavily defended Fort Ridgely and instead turn to the settlement of New Ulm, killing white settlers along the way. 1903 – The Transfiguration Uprising breaks out in East Thrace, resulting in the establishment of the Strandzha Commune. 1909 – The Indianapolis Motor Speedway opens for automobile racing. William Bourque and his mechanic are killed during the first day's events. 1920 – The Tambov Rebellion breaks out, in response to the Bolshevik policy of Prodrazvyorstka. 1927 – Patriarch Sergius of Moscow proclaims the declaration of loyalty of the Russian Orthodox Church to the Soviet Union.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Detail from The Surrender of Ulm, 20th October, 1805 - Napoleon and the Austrian generals, 1815

Artist: Charles Thevenin

0 notes

Text

War and Peace 30/198 -Leo Tolstoy

PART SECOND

21

1805, Tsar Alexander I ruled Russia after his father, the mad Tsar Paul, was assassinated in 1801, he has taken the lead to stop Napoleon. His allies are emperor Francis of the dying Holy Roman Empire, King Gustavus of Sweden, and Britain. As the land campaign begins Lord Nelson’s fleet at Trafalgar freed Britain from the threat of invasion in October of 1805. Now Napoleon invades Austria and under General Kutuzof the Russian force moves south. (if they think European politics were a clusterfuck now just wait about a century)

1805 the Russian army was quartered in towns in Austria putting the inhabitants under heavy burden. (this is why America has this as our Third Amendment) A new regiment arrived outside the city waiting to be received, along the highway came a Viennese carriage and Croatians. Kutuzof and the Austrian general were in conversation, Kutuzof stepped out of the carriage and gave command and inspected the men. The twenty men of his suite followed Kutuzof including his aide Prince Andrei and messmate Nesvitsky.

At the third company Prince Andrei reminded him of Dolokhof, who stepped out to ask a favor to be given the chance to wipe out his fault and show his devotion. Kutuzof already knew it was all a bore to him and went back to the carriage. The regiment broke into companies and marched to quarters, Zherkof had once belonged to a wild set in Petersburg that Dolokhof was in charge of now, an officer with Kutuzof, setting example he went up to him like a friend. Dolokhof refuses to drink or play until he is promoted, Zherkof tells him the staff will help, Dolokhof laughs, he won't ask for help and they depart.

22

In the short time Andrei left Russia he changed a lot, the appearance of a man who no longer had the time to worry about impressions. Kutuzof treated him with more distinction then his other aides and trusted him with the most important duties. Kutuzof sent letters to his friend, Andrei’s father, that he’s fortunate to have such an assistant. (you’re son’s the best gopher I’ve ever had) Andrei told the aide Kozlovsky to draw up an account for not advancing, no news of Mack either. Then an imposing German general, who’s head was wrapped in bandages arrives, they try to prevent him from seeing Kutuzof, when he does, he’s recognized as Mack. The Austrians were defeated, the army surrendered at Ulm, within half an hour aides were flying, giving out orders to the Russian army to meet the enemy. Andrei was the uncommon staff officer who was interested in the operations of war, on seeing Mack he knew half the campaign was lost and pictured the fate of the Russians but still felt delight of Austria’s defeat. “But be feared lest Bonaparte’s genius should show itself superior to all the valor of the Russian troops, and at the same time he could not bear the thought of his hero’s suffering disgrace.”p.83

23

The Pavlohrad hussars were camped two miles from Braunau, Nikolai Rostof’s squadron was in Salzeneck and squadron commander, Captain Vaska, was assigned the next best house in the village. The day when Mack’s defeat was known the squadron was still going about its life, that morning Rostof went to see Denisof but he was gone, probably losing at cards. Ten minutes later Denisof walked home followed by his Lieutenant Telyanin, he was removed from the Guards before the campaign, he conducted himself decently but wasn’t liked, Rostof got Telyanin to leave.

When he returned the quarter master was there for his money and Denisof he couldn’t find his purse. Denisof blames his footman Lavrishka, but Rostof says he knows who took it and went to Telyanin’s rooms, but he went to headquarters two miles away. Rostof went out and found Telyanin’s horse at a tavern and saw him with a purse of coins. (ah I see why no one likes him) Rostof took it as a pretext of admiring it but didn’t give it back until Telyanin took it back. Then Rostof quietly accused him of theft. Telyanin grew scared and began to beg, Rostof asks how he could have done such a thing and left the tavern.

That evening some officers had a discussion in Denisof’s rooms, the calvary captain Kirsten told Rostof to apologize to the regimental commander. Rostof refused to be called a liar, he can do anything to him but he won't apologize. It’s not his fault the conversation took place in front of other officers, maybe it was for the best. (they’re seriously protecting the thief because Rostof inadvertently insulted the commander when he acted insubordinate as called out Telyanin) Kirsten says that’s not the point, he said foolish things to Bogdanitch, so must apologize, he won't. Denisof says he won't be in the regiment next year what's the difference, but Rostof says it’s for honor, but he is to blame but he cannot apologize, Kirsten warns Bogdonitch is spiteful. Telyanin already reported himself ill so won't be on duty tomorrow, (the coward) Denisof says if he sees him hell kill him. Then Zherkof comes in to report Mack was defeated, it’s up to them now and the regiment was ordered to break camp the next day.

24

Kutuzof retreated to Vienna destroying bridges they crossed, at the Enns bridge it rained through it, Russian troops could be seen plodding along in masses. (in war mud is your worst enemy) The general called the bridge to be burned after they crossed it, (at least they crossed it before burning their bridge) the last of the infantry hurriedly marched and Denisof’s command were left at the end to face the enemy but could not see them. Then at the opposite road the French arrived, the space between them two thousand feet and the gap between two hostile forces could be felt. “One step beyond the line, which is like the bourn that divides the living from the dead, and there is the unknown of suffering and of death. And what is there? Who is there? There, beyond that field, beyond that tree, and that roof, glittering in the sun? No one knows, and no one wishes to know, and it is terrible to pass across that line, and I know sooner or later I shall have to cross it, and shall know what is there on that side of the line, just ad inevitably as I shall know what is on the other side of death.”p.91

He is young but every man there and feel the same even if they don’t have words for it. A canon ball flew over their heads and the hussars looked to their commander for orders as more cannons fired. Denisof offered to attack but the officer had him order his squadron back across the bridge, the regimental commanders took over Denisof’s squadron. Rostof watched and concluded Bogdonitch (I hate foreign names only for the fact autocorrect keeps telling me they're misspelled and I don't know if it really is or autocorrect's not familiar with them) was going to send the squadron into forlorn hope just to punish him then later give him a reconciliation hand in honor of the wound. (really you’d sacrifice troops during war not even for strategy purposes but to get back at someone you felt slighted by was this back when you were promoted because of nepotism not for merit)

Zherkof told the colonel he’s ordered to burn the bridge later, Nesvitsky himself rode up complaining he hadn't followed orders, the colonel told him he said no such thing as to who would burn it. He rides off and orders the squadron to do it under the command of Denisof. Rostof no longer looked at the commander, he was afraid to be left behind by the hussars and saw nothing but said hussars riding by him. Behind him someone called for stretchers, Rostof didn’t think what they meant, only focused on the advance until he slipped in the mud and fell (see I told you) the others dashing ahead of him. Rostof got up glancing at the commander Bogdanitch, who didn’t notice who it was, called for him to take the right side. Now the other officers saw the advancing French army wondered if the hussars had time to set the bridge on fire. The French fired cannons and men fell as Rostof remained on the bridge not knowing what to do as men died and injured were carried off. “The terror of death and of the stretchers, love for the sun and for life, all mingled in one painfully disturbing impression.”p.96 Rostof starts praying, admits he’s a coward. Zherkof celebrated the splendid report and his potential promotion. The colonel has him send out the report that it was his orders to burn the bridge and the loss as a trifle, two wounded one dead. “said he, with apparent joy, and scarcely refraining from a contented smile as he brought out with ringing emphasis is the happy word, dead.”p.96 (you’re a ghoul)

25

The Russian army, thirty-five thousand under Kutuzof, were pursued by the French under Napoleon, met unfriendly natives suffering under the war, no provisions, filed down the Danube. Vienna couldn’t be defended unless he sacrificed his troops, he’ll have to affect a juncture with troops on their way from Russia. In November, Kutuzof’s army crossed the left bank and finally halted. On November tenth he defeated Mortier taking some cannons and generals, but now they were exhausted and reduced by a third. During the battle Andrei was sent to send the news of victory to the Austrian court at Brunn, insuring a promotion. He imagined meeting Emperor Franz but at the entrance, being only a courier, the official sent him round back to the war minister who didn’t acknowledge him for several minutes. Andrei concluded with all the interests of war, Kutuzof’s army was the least. finally, he looks at Andrei and says he hopes its good news, but reading the report called it a misfortune, the death of Schmidt but a cost for victory, his majesty will probably see him tomorrow.

26

Andrei stayed with his friend Bilibin, after all he’s been through once again enjoyed luxuries he's had since childhood. Bilibin was on the road to success in diplomacy, starting at sixteen now had a very responsible post at thirty-five. Andrei tried but couldn’t understand, maybe he doesn’t get the diplomatic subtleties, but Mack destroyed a whole army and the Archdukes Ferdinand and Karl keep making mistakes and when Kutuzof makes a victory the war minister isn’t interested. Bilibin says the victory is too late as the French now occupy Vienna and Napoleon is at Schonbrunn. Bilibin believes Austria will take revenge and he suspects they are being duped. “I suspect dealings with the France and a project of peace, a secret peace, separately concluded.”p.100 (so France and Austria are trying to make political back door deals) Whoever lives will learn the truth. (well yes but history is written by the winners) Andrei is advised to lie about the provisions to the Emperor and in bed he felt the battle he reported far away but could still hear it in his dreams.

Seeing the Emperor, Andrei recounted the battle and answered questions, but the Emperor was not interested in the answers. After leaving the audience chamber courtiers surrounded him and invitations and congratulations were given overwhelming him. Returning to Bilibin’s found him packing, they have to move, the French crossed the Thabor bridge, no one knows why it wasn’t destroyed. Andrei, finding out it was hopeless for the Russians decided it was his job to rescue them to the path of glory. Bilibin goes on saying there is an armistice and France decided to conference with Napoleon and Prince Auersperg, he calls it all lies. Auersperg will be so dazzled and bewitched by the French Marshalls he’ll forget what to point at the enemy. Andrei suspects the Thabor bridge is treason Bilibin says it’s not treason or stupidity, it’s the same as Ulm, they are like Mack, Andrei leaves for the army immediately. Bilibin says he’s been thinking of him, and one of two things will happen to him,either there will be peace by the time he gets there or hell await disgrace with Kutuzof’s force, Andrei says he’s going to save the army, Bilibin calls him a hero.

27

On November thirteenth, Kutuzof learned that his army was in an almost unextractable position, the French were advancing on Zaim in Kutuzof’s line of retreat. If they reached Zaim before the French, there’s hope, but if not the disgrace of surrender or destruction. That night Kutuzof sent four thousand to occupy the road and if needed Bagration would hold back the French if they must. He went without rest for twenty-four hours, exhausted but made it. After this success Murat thought to try a similar deception. Finding Bagration’s feeble contingent, thought it was the whole army, but to leave no doubt waited a few days but the armistice prevented unnecessary bloodshed. This gave Kutuzof time, he sent Winzengerode to the hostile camp to accept the armistice and terms. Napoleon read Murat’s report and saw through the hoax and sent a letter back to end it unless the Russian Emperor ratifies it, but it is a trick march and destroy the army. The Austrians were duped of the Vienna bridge and so Murat was duped by the Russians as Napoleons sent out the letter he also moved towards the field.

28

Andrei reached Grund by four and reported to Bagration, the battle hadn't begun yet giving him a choice be present during the battle or to be in the rear for retreat. An officer offered to show him around, in the down time the men become complacent and left their posts, Andrei scolds them back to their places. After riding out the entire line Andrei went to the battery and overheard the officers discussing what will come, they can expect death and are afraid of it, what comes after, but they were cut off by a whiz of a cannon ball. The French were starting to move, Murat received the letter and Andrei rode to warn Bagration.

29

The right wing retreated from the charge of the Sixth Jaegers. Tushin’s battery set the village of Schongraben on fire and gave time for the Russians to retreat but no demoralization, but the left wing was defeated under the French. Zherkof became cowardly and fearful and didn’t go to the front and didn't deliver Bagration’s order of retreat. The command of the left wing devolved leading to misunderstandings as the battle came upon them the infantry general begged the Pavlohrad Commander to meet the charge, the general took the refusal as a challenge. (the Russian army and it’s leaders are completely undisciplined)

The general and colonel looked at each other for signs of cowardice, both won the test they would have stood longer if the war sounds didn’t close in behind them in the forest. (the army is in chaos and being fired upon as these two are having a staring contest) Now it’s impossible for them to retreat with the infantry, now they had to fight through. Rostof’s squadron faced the enemy between them, the gap of the unknown, dividing living from dead. Denisof ordered them forward and Rostof felt the charge becoming more and more exciting now that he passed the line. “But now he had passed beyond it and there was not only nothing terrible about it, but everything seemed ever more and more jolly and lively.”p.110 (that’s the adrenalin kicking in) He dashed his horse, Grachik, farther and readied to strike when his horse is thrown back wounded. (no not Grachik) He wondered where the line separating the armies was as his arm felt numb and sees Russians running towards him, he wonders why they are going to kill him, everybody loves him. “He recollected how he was beloved by his mother, his family, his friends, and the idea that his enemies might kill him seemed incredible.”p.111 As a Frenchman came near him with a bayonet, he threw his pistol at him (that’s not how to use it) and he fled into the thicket.

30

Tushin’s battery was forgotten until the end of the engagement, Bagration sent Andrei to order them to retire, they had held back the French that were convinced the Russians were concentrated at the center. Their delight in that caused them not to notice the French to the right until their guns were blown out, after an hour seventeen of forty gunners were disabled. Tushin spotted the staff officer arriving calling out they were told to retire twice; Tushin’s response was cut off by a cannon ball landing by him. The soldiers laughed at his order to retreat until Andrei came with the same message. Andrei saw the bloodshed and dodged canon fire, telling himself not to be afraid and helped dismantle as the French continued to fire. When he and Tushin said goodbye and separated Tushin didn’t know why he had tears.

NEXT

0 notes

Text

The Surrender of Ulm, 20 October 1805 by René Théodore Berthon

Napoleon takes the surrender of General Karl Mack von Leiberich and the Austrians at Ulm on 20 October

#napoléon bonaparte#napoleon bonaparte#art#rené théodore berthon#surrender#capitulation#ulm#france#austria#battle of ulm#europe#european#napoleonic wars#history#ulm campaign#french empire#habsburg monarchy#austrian#french#germany#emperor#napoleon#bonaparte#soldiers#battle#landscape#napoleonic#marengo#napoléon

111 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This painting looks familiar but I can’t remember what it is (saw on pinterest). It looks like surrender at Ulm.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

This chapter is very short, so I’ll just go paragraph by paragraph:

“A few squares of the Guard, standing motionless in the swash of the rout, like rocks in running water, held out till night. They awaited the double shadow of night and death, and let them surround them. Each regiment, isolated from the others, and no longer connected with the army which was broken on all sides, died where it stood. In order to perform this last exploit, they had taken up a position, some on the heights of Rossomme, others on the plain of Mont St. Jean. The gloomy squares, deserted, conquered, and terrible, struggled formidably with death, for Ulm, Wagram, Jena, and Friedland were dying in it. When twilight set in at nine in the evening, one square still remained at the foot of the plateau of Mont St. Jean. In this mournful valley, at the foot of the slope scaled by the cuirassiers, now inundated by the English masses, beneath the converging fire of the hostile and victorious artillery, under a fearful hailstorm of projectiles, this square still resisted. It was commanded by an obscure officer of the name of Cambronne. At each volley the square diminished, but continued to reply to the canister with musketry fire, and each moment contracted its four walls. Fugitives in the distance, stopping at moments to draw breath, listened in the darkness to this gloomy diminishing thunder.”

The simile of “rocks in running water” is kind of beautiful for something so gruesome? I don’t have very concrete thoughts on it, I just think Hugo chose a nice image there. However, it does represent another example of Hugo’s interest in water metaphors, which recurs later in the paragraph as the English “inundate” the valley. I think his word choice there is really effective. There’s something terrifying about being trapped in a flooding valley, where the landscape makes escape impossible, and having that be where the French are stuck heightens the sense of panic.

This paragraph also makes numerous references to darkness: the “double shadow of night and death;” “twilight;” and “listened in the darkness to this gloomy diminishing thunder.” While most references to darkness so far have been metaphorical, here, this darkness is very literal (night is falling) even as it represents death. The simple language used to describe it makes it more impactful. This darkness is not about the struggle within a person, or between a person and fate, which merits lengthy paragraphs; this is simply the darkness of night and the darkness of death.

“When this legion had become only a handful, when their colors were but a rag, when their ammunition was exhausted, and muskets were clubbed, and when the pile of corpses was greater than the living group, the victors felt a species of sacred awe, and the English artillery ceased firing. It was a sort of respite; these combatants had around them an army of spectres, outlines of mounted men, the black profile of guns, and the white sky visible through the wheels; the colossal death's-head which heroes ever glimpse in the smoke of a battle, advanced and looked at them. They could hear in the twilight gloom that the guns were being loaded; the lighted matches, resembling the eyes of a tiger in the night, formed a circle round their heads. The linstocks of the English batteries approached the guns, and at this moment an English general,—Colville according to some, Maitland according to others,—holding the supreme moment suspended over the heads of these men, shouted to them, "Brave Frenchmen, surrender!"”

Hugo again leans on the horrific aspects of defeat. The reference to the “pile of corpses” is the most brutal part of this, highlighting the extent of French losses during the battle, but the way he describes the English contributes to this as well. They are “spectres” who appear in black and white, partly because of the darkness and partly because of their ghostliness. Even though the French can see some things, most of the details here are about what they hear. They can’t see well enough to make out every detail, and thus have to rely on their other senses while surrounded by these armed spectres (which again, is terrifying to imagine). That everything is in black and white also makes the events seem graver and more extreme, as all the soldiers see is in absolute contrasts rather than in an array of colors.

It’s also intriguing that Hugo says the matches of the English resembled “the eyes of a tiger in the night.” On the one hand, tigers are predators, making this an apt comparison for a force endangering the lives of these French soldiers. On the other, Hugo typically employs feline imagery for the masses and the downtrodden (Valjean, the people of Paris, etc). If this was against Napoleon, perhaps this would fit this pattern, as his downfall is linked to divine retribution on behalf of the populace. Here, though, all of the French soldiers present are fairly ordinary rank-wise. Even Cambronne is only an “obscure officer.” Consequently, this big cat comparison may really just be for the predatory image.

Another detail that’s emphasized here is the courage of these soldiers. Hugo calls them “heroes,” and even the English address them as “brave Frenchmen.” This could be a formulaic way of seeming respectful on the battlefield, so it might not be unusual, but it also could be a way of making sure the French are praised even in defeat.

Cambronne answered, "Merde!"

So this is what the next chapter will be about!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Surrender of Ulm, 20 October 1805 (detail)

Charles Thévenin

#Charles Thévenin#ulm#ulm campaign#napoleonic#napoleonic wars#3rd coaltion#war of the 3rd coalition#napoleonic era#19th century#first french empire#french empire#austria#austrian empire#habsburg#habsburgs#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Francis ii#holy Roman Empire#Germany#history

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Allegory of the Surrender of Ulm, 20 October 1805, and

Allegory of the Battle of Austerlitz, 2 December 1805

by Antoine-François Callet, 1806

in the collection of the Palace of Versailles

#19th century art#allegorical painting#glorification of Napoleon Bonaparte#neo-classicism#lots of drama

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Biography of Marshal Ney (Part 2)

The next four parts will be about Ney’s military campaigns, as I’m strictly following the Sénat’s format. But first, this short passage, which I forgot to translate from yesterday’s post. It is significant, because it demonstrates that Ney was not an enthusiastic partisan of Bonaparte’s imperial ambitions. This ought to have appeared right after the mention of Bernadotte:

His participation in numerous battles earned him several serious wounds: in the arm at Mayence in December 1794, in the thigh at Winterthur in May 1799, where he had to prevent the Austrians and Russians from joining forces under Masséna's orders.

He was temporarily put to rest in his estate at La Malgrange, near Nancy. There he learned of Bonaparte's coup d'état on 18 Brumaire (9 November 1799), which marked the advent of the Consulate, to which he adhered with reservations: he devoted himself "to his country and not to the man it had chosen for its governance."

His valour and his cavalry exploits earned him the nickname of "the Indefatigable" by his men, the "Taker of cCities" following the capitulation of well-guarded and fortified Forsheim in August 1796, but also earned his being taken prisoner by the Austrians in April 1797.

And now for the next instalment. To keep things reasonably brief, I will omit the French text I am about to translate, but for those who would like to read the original, here is the link:

https://www.senat.fr/evenement/archives/D26/le_marechal_ney/sous_lempire.html

Campaigns in Germany, Austria and Russia (1805-1807)

The Empire was in great need of victories against the European coalitions, which led the country into endless wars.

In 1805, England, Russia and Austria formed the third coalition against France. The Grande Armée therefore had to leave the shores of the Channel for the Rhine. Appointed commander of the Sixth Corps, Ney could tolerate with great difficulty being under Murat's orders.

He pleased Napoleon by taking Elchingen on 14 October, placing himself at the head of his tired troops. This battle was decisive in the surrender of the fortress of Ulm on 20 October 1805. Ney was then ordered by Napoleon to occupy the Tyrol, which kept him away from the march to the Danube, and the battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805.

On 26 December 1805, a peace treaty was signed in Presburg, but a fourth coalition was formed in the summer of 1806. Marshal Ney then contributed to the victory of Jena on 14 October 1806, to the capitulation of the citadel of Magdeburg on 8 November, and to the difficult victory of Eylau (a veritable carnage) on 8 February 1807 against the Prussians and the Russians.

In June 1807, the Russians resumed the offensive. Marshal Ney was forced to retreat to Gutstadt. This very difficult manoeuvre then became one of his strong points: he managed to hold out against the enemy while saving a maximum number of his troops. At Friedland, on 14 June, the Russian army was annihilated. The Bulletin de la Grande Armée dscribed Ney to be the architect of this victory: "Marshal Ney, with a coolness and intrepidity that is peculiar to him, was in front of his troops, directed the smallest details himself and set an example for his corps, which has always been distinguished even among other corps of the Grande Armée." This victory was a prelude to the treaties of Tilsit (July 1807), which put an end to the fourth coalition. Soldiers then nicknamed Ney the "Bravest of the Brave", a nickname taken up by Napoleon to refer to him.

However, his difficult, intemperate and volatile character could play to his disadvantage. He was not reputed to be a fine strategist. He could even be capricious and misinterpret orders, or even fail to obey them. Napoleon spoke thus about Ney: "Easily offended, irritable, overly impressionable, extremely volatile. He was a man who only lived in the moment. As much as he was firm, laconic and resolute on the battlefield, he was weak, verbose and indecisive in political matters."

In 1808, Napoleon nevertheless made him Duke of Elchingen. After Friedland, Ney received an annual pension of twenty-six thousand francs, as well as a bonus of six hundred thousand francs, to be paid for by the defeated.

The interval from September 1807 to August 1808, about a year, was spent in Paris, in his hotel in the rue de Lille. Not truly happy in Paris, he also acquired a huge property in Eure-et-Loir, Les Coudreaux, near Châteaudun. He was then the father of three boys aged two, four and five (he had four in total).

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

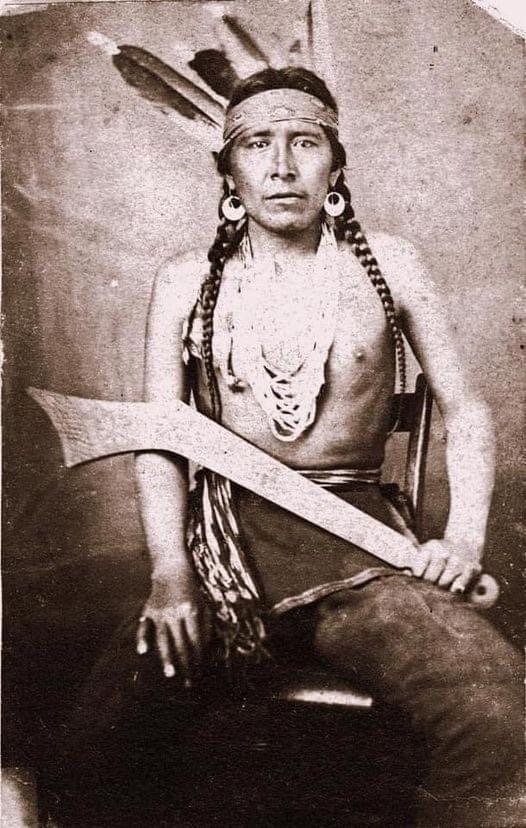

Chief Big Eagle 🦅 (1827-1906)

Mdewakanton Dakota Chief; during the US-Dakota War of 1862, he commanded a Mdewakanton Dakota band of two hundred warriors at Crow Creek in McLeod County, Minn. His Dakota name was "Wamdetonka," which literally means Great War Eagle, but he was commonly called Big Eagle. He was born in his Black Dog's village a few miles above Mendota on the south bank of the Minnesota River in 1827. When he was a young man, he often went on war parties against the Ojibwe and other enemies of the Dakota. He wore three eagle's feathers to show his coups. When his father Chief Grey Iron died, he succeeded him as sub-chief of the Mdewakanton band.

In 1851, by the terms of the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota, The Dakota sold all of their land in Minnesota except a strip ten miles wide near the Minnesota River. In 1857, Big Eagle succeeded his father, Grey Iron, as Chief. In 1858, the remaining land was sold through the influence of Little Crow. That same year, Big Eagle went with some other chiefs to Washington D. C. to negotiate grievances with federal officials. Negotiations were unsuccessful. In 1894, he was interviewed about the Dakota War and its causes. He spoke about how the Indians wanted to live as they did before the treaty of Traverse des Sioux – to go where they pleased and when they pleased; hunt game wherever they could find it, sell their furs to the traders and live as they could. He also spoke of the corruption among the Indian agents and traders, with no legal recourse for the Dakota, and the way they were treated by many of the whites: "They always seemed to say by their manner when they saw an Indian, 'I am much better than you,' and the Indians did not like this. There was excuse for this, but the Dakotas did not believe there were better men in the world than they..."

In 1862, Big Eagle's village was on Crow Creek, Minn. His band numbered about 200 people, including 40 warriors. As the summer of 1862 advanced, conflict boiled among the Dakota who wanted to live like the white man and the majority who didn't. The Civil War was in full force and many Minnesota men had left their homes to fight in a war that the North was said to be losing. Some longtime Indian agents who were trusted by the Dakota were replaced with men who did not respect the Indians and their culture. Most of the Dakota believed it was a good time to go to war with the whites and take back their lands. Though he took part in the war, he said he was against it. He knew there was no good cause for it, as he had been to Washington and knew the power of the whites and believed they would ultimately conquer the Dakota people.

When war was declared, Chief Little Crow told some of Big Eagle's band that if he refused to lead them, they were to shoot him as a traitor who would not stand up for his nation and then select another leader in his place. When the war broke out on Aug. 17, 1862, he first saved the lives of some friends - George H. Spencer and a half-breed family - and then led his men in the second battles at Fort Ridgely and New Ulm on August 22 and 23. Some 800 Dakota were at the battle of Fort Ridgely, but could not defeat the soldiers due to their defense with artillery. They retreated and a few days later, he and his band trailed some soldiers to their encampment at Birch Coulee, near Morton in Renville County. About 200 of the Dakota surrounded the camp and attacked it at daylight. After two days of battle, General Sibley arrived with reinforcements and the Dakota eventually retreated. He and his band participated in a last attempt to defeat the whites at the battle of Wood Lake on September 23. However, they were once again defeated when their hiding place for ambush was discovered prematurely by some soldiers who went foraging for food

Soon after the battle, Big Eagle and other Dakotas who had taken part in the war surrendered to General Sibley with the understanding they would be given leniency. However, he was one of about 400 Dakota men who were tried by a Military Commission for alleged war crimes or atrocities committed during the war. After a kangaroo court trial, Big Eagle was sentenced to ten years in prison for taking part in the war. At his trial, a great number of witnesses were interviewed, but none could say that he had murdered any one or had done anything to deserve death. Therefore, he was saved from death by hanging. He was released after serving three years of his sentence in the prison at Davenport and the penitentiary at Rock Island. He believed his imprisonment for that long of a time was unjust because he had surrendered in good faith. He had not murdered any whites and if he killed or wounded a man, it had been in a fair, open fight.

The translators who interviewed him in 1894 described him as being very frank and unreserved, candid, possessing more than ordinary intelligence, and deliberate in striving to speak the truth. When speaking of his imprisonment, he said that all feeling on his part about it had long since passed away. He had been known as Jerome Big Eagle, but his true Christian name was "Elijah." For years, he had been a Christian and he hoped to die one. "My white neighbors and friends know my character as a citizen and a man. I am at peace with every one, whites and Indians. I am getting to be an old man, but I am still able to work. I am poor, but I manage to get along." He lived his final years in peace at Granite Falls, Minn.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Allegory of the Surrender of Ulm, 20th October 1805

Artist: Antoine François Callet (French, 1741–1823)

Medium: Oil painting

Description

Allegorie de la Reddition d'Ulm; General Karl Mack (1752-1828) surrendering to Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821); capitulation of Austrian army to French.

#allegory#surrender#antoine francois callet#capitulation#austrian army#napoleon#horses#army#soldiers#19th century#history#european#key#eagle#austria#france#french#french painter

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 10.19 (before 1950)

202 BC – Second Punic War: At the Battle of Zama, Roman legions under Scipio Africanus defeat Hannibal Barca, leader of the army defending Carthage. 439 – The Vandals, led by King Gaiseric, take Carthage in North Africa. 1386 – The Universität Heidelberg holds its first lecture, making it the oldest German university. 1453 – Hundred Years' War: Three months after the Battle of Castillon, England loses its last possessions in southern France. 1466 – The Thirteen Years' War between Poland and the Teutonic Order ends with the Second Treaty of Thorn. 1469 – Ferdinand II of Aragon marries Isabella I of Castile, a marriage that paves the way to the unification of Aragon and Castile into a single country, Spain. 1512 – Martin Luther becomes a doctor of theology. 1579 – James VI of Scotland is celebrated as an adult ruler by a festival in Edinburgh. 1596 – The Spanish ship San Felipe runs aground on the coast of Japan and its cargo is confiscated by local authorities. 1649 – New Ross town in Ireland surrenders to Oliver Cromwell. 1781 – American Revolutionary War: The siege of Yorktown comes to an end. 1789 – John Jay is sworn in as the first Chief Justice of the United States. 1791 – Treaty of Drottningholm, between Sweden and Russia. 1805 – War of the Third Coalition: Austrian General Mack surrenders his army to Napoleon at the Battle of Ulm. 1812 – The French invasion of Russia fails when Napoleon begins his retreat from Moscow. 1813 – War of the Sixth Coalition: Napoleon is forced to retreat from Germany after the Battle of Leipzig. 1847 – The novel Jane Eyre is published in London. 1864 – American Civil War: The Battle of Cedar Creek ends the last Confederate threat to Washington, DC. 1864 – American Civil War: Confederate agents based in Canada rob three banks in Saint Albans, Vermont. 1866 – In accordance with the Treaty of Vienna, Austria cedes Veneto and Mantua to France, which immediately awards them to Italy in exchange for the earlier Italian acquiescence to the French annexation of Savoy and Nice. 1900 – Max Planck discovers Planck's law of black-body radiation. 1912 – Italo-Turkish War: Italy takes possession of what is now Libya from the Ottoman Empire. 1914 – World War I: The First Battle of Ypres begins. 1921 – The Portuguese Prime Minister and several officials are murdered in the Bloody Night coup. 1922 – British Conservative MPs vote to terminate the coalition government with the Liberal Party. 1935 – The League of Nations places economic sanctions on Italy for its invasion of Ethiopia. 1943 – The cargo vessel Sinfra is attacked by Allied aircraft at Crete and sunk. Two thousand and ninety-eight Italian prisoners of war drown with it. 1943 – Streptomycin, the first antibiotic remedy for tuberculosis, is isolated by researchers at Rutgers University. 1944 – United States forces land in the Philippines. 1944 – A coup is launched against Juan Federico Ponce Vaides, beginning the ten-year Guatemalan Revolution.

0 notes

Text

Prince Bagration Makes a Cameo Appearance

Another excerpt from the longest-running histfic draft. This is for Tairin. I hope I did her prince justice, small though it may be.

Jean’s staff found a two-story house large enough for them all in a northern Viennese suburb. General Compans ordered the portly, red-faced owner and his large family to leave, slipping him a fistful of gold coins before he could protest. Mariana couldn’t tell how many coins constituted a fistful, but they produced an incredulous expression on the man’s face and then a deep bow that revealed his blindingly bald, pink pate. There must be a secret source of gold coins that only Compans and Thomières knew about, perhaps hidden away in a sturdy oak box labeled Bribes. She had seen these coins appear whenever Jean wanted to sleep somewhere other than a barn or outside on the ground for several days. She also knew only a very few marshals and generals bothered to compensate the people whose lives they disrupted or even thought to do so.

“Don’t wreck the place,” Compans ordered them after the Viennese family had bustled out the door, their personal belongings tied up in large, unwieldy bundles.

“Why would we?” she asked Joseph as two adjutants added more wood to a fire in the large stone hearth. She wondered how much food she might find in the kitchen cupboards and the spacious pantry leading from the kitchen. Indeed, the life expectancy of the well-fed hens she’d seen in the dooryard was measured in minutes.

“It was a pro forma reminder,” Joseph replied. “We’ve never been a horde of Vandals or Huns, and the marshal knows it.” He grinned at her and stretched so much that he almost slid out of his chair. “I can’t say the same about Prince Murat’s cavalry or anyone in Marshal Augereau’s VII Corps. Now there’s a collection of seasoned plunderers—as bad as one of the plagues of Egypt, but not, I think, as dedicated to looting as Marshal Masséna.”

Later that evening, with a cold November wind safely outside and warmth and food inside, she sipped her second cup of rich coffee laced with cream from the black and white cow standing up to her knees in hay in the barn. “After ages in Purgatory, I’ve been given my reward.”

“Savor your taste of Paradise, Gabriel, while you can. We’re leaving in a couple of days,” Jacques said, unhooking his cloak and shaking sleet from it.

“Why? The Austrians surrendered at Ulm almost four weeks ago, and we’re north of Vienna with no Austrians anywhere that I can see. There isn’t anyone to fight.”

Jacques poured coffee from a porcelain pot and backed up to the fire. “Don’t you read the dispatches, Gabriel?”

“Not often—they’re boring.”

“Well, you should. We hadn’t seen the Austrian army because it left Vienna right before we arrived. Now they’ve gone further north, with General Kutuzov’s Russians.”

“Who’s Kutuzov?” she asked, trying not to yawn in his face. She really should pay more attention to the dispatches and reports. If Jean ever asked her about the campaign's minutia, she had better know enough to answer. She’d seen what happened when an officer couldn’t tell Jean what he wanted to know and didn’t want to subject herself to the humiliation of a profanity-laced public rebuke.

“Some clever Russian general, older than God. He’s heading for Moravia, though, not Mother Russia.”

Mariana remembered Jacques’s words three days later. Ejected from the warm stone house before dawn, she bundled up in her heavy cloak and gloves and rode out of Vienna with the rest of V Corps. Now, close to midnight, she didn’t think Moravia was anywhere close or warmer than Russia. It was full dark when they rode into a tiny hamlet so small they would have missed it if the scouts and leading edges of Oudinot’s grenadiers hadn’t literally stumbled over it. Snow topped with a thin layer of rime covered the cottage roofs, garden walls, the rough pathway serving as a street, and stubble in the surrounding fields. The inhabitants had shuttered every window, but thin cracks of pale yellow light escaped from some of them.

“They’re more afraid of the Russians than they are of us,” Jean said in response to her question. Each word came out on a small puff of white, as her own had done. Soon it might be too cold to talk. “If you looked in those barns, you’d find nothing but old straw. There’s nothing of value in the cottages, either. If the villagers had enough warning, they would have hidden everything, and if not, the Russians have it all now.”

Mariana had never seen a hamlet this small before or so eerily deserted. The barrenness she saw in the faint snow light and that Jean had described made her shiver. This time the cold struck deep in her bones.

“We’ll be sleeping outside, gentlemen, on the other side of Hollabrünn and eating whatever we have with us. It will be a short night anyway—the enemy’s less than six miles ahead.” Jean spurred his horse forward over the little village track, and the rest followed, riding close enough to brush each other’s stirrups. Mariana wrapped the reins around one wrist and massaged her hands and fingers inside her gloves, afraid to take them off. The idea of trying to sleep on the frozen, iron-hard ground was dreadful. If the Russians were so close, and if Jean meant to attack them in the morning, she might as well sit up all night. If she didn’t freeze before dawn, then a brisk encounter with the enemy, even hand to hand, would warm her up nicely. “Aunt Lucrezia, you would be appalled,” she whispered through stiff lips cracked and bleeding from the cold.

Despite her plan to sit up all night, Mariana had just fallen asleep, curled into a tight ball, knees drawn up nearly beneath her chin, when Joseph shook her into befuddled wakefulness. “Get up, Gabriel,” he said, peeling her cloak away. We’re leaving now.”

She staggered to her feet, grabbed her cloak back from Joseph, and buttoned it up tight. “No breakfast?”

“No time for any. There’s a small Russian rear-guard ahead. We have to eliminate it before it reaches Kutuzov.”

Mariana didn’t mind not eating as much as she minded not having something hot to drink. However, the worst prospect was having to do the necessary at the edge of the forest to her left. She still thought it was manifestly unfair that lately, she nearly froze whenever she pissed, while her comrades did not. An inequality, however, that she was powerless to alter one whit.

Having concluded her business in the forest, she hurried to untie Odysseus from the picket line, tighten his girth, and climb into the saddle. She trotted off to join the aides, who waited in a nearly silent group, close together, their horses impatiently stamping the hard ground. Without a word, they swung around and fell in behind Jean and General Compans. She wanted to know how far away the Russian rear-guard was and how many Russians comprised a rear-guard, but she couldn’t make her lips move.

General Thomières saved her the trouble. “Excellency, how many troops does Bagration have ahead of us?”

While she wondered who Bagration was, Jean slowed his horse to respond to his senior aide. “Fewer than I have, even though I’m short two divisions and even shorter of supplies. Neither the weather nor the ground is good for much but a short skirmish.”

The air was so silent and frigid that Mariana heard the intonation beneath his words that often meant more than the words themselves. He sounded confident rather than cocky or foolhardy. A short skirmish, he’d said, and that was fine with her.

The encounter between Bagration’s rear-guard and V Corps’ grenadiers, reinforced at the last possible moment by a squadron of Murat’s heavy cavalry, was not a skirmish. Mariana thought it was more like a brawl in some wayside tavern, loud, fast, and disorganized. It ended before she’d had a chance to do anything and because Bagration told Prince Murat that he had just learned about a truce. The prince believed him, dismounted, told Jean to order his troops to cease fire, and went inside a slightly shell-shocked villa that had been some Moravian aristocrat’s summer home.

“A truce? What the fuck is he talking about? I had the damn Russians on their arses, and he rides in and orders me to stop!” Jean was livid, his expression as hard as granite. Mariana worried what he might do when he jumped from his horse, leaving the reins to trail in the snow, and stomped after Murat. Acting on instinct, aides, chief of staff, and a few senior adjutants closed around him like a protective wall and entered the villa together.

Intended for soft summer breezes, the villa struggled to combat the mid-November cold. Fires burned in hearths at either end of the reception chamber’s black and white tiled floor. Clear glass bottles filled with colorless liquid stood among scores of crystal glasses on heavily carved tables in the center of the room. Someone had shoved chairs and settees against the walls. Officers in uniforms Mariana had never seen before crowded around the tables, opening bottles, pouring liquid into glasses, and handing them around. She watched Prince Murat take a sip, then drain it and hold it out for someone to fill. She watched Jean barrel forward, his expression still thunderous, until a tall officer with the face of a young eagle and enough medals on his chest to blind half a dozen men stepped forward and intercepted him. Together they moved away from Murat and his entourage and stood by one of the double windows, heads bent close together, talking. Another officer approached them, two glasses on a silver tray, and quickly left when they took the glasses and continued their conversation. When Major Guéhéneuc tried to insinuate himself into the conversation, Jean turned on him like an enraged wasp. The major scuttled away, staring at the floor, his face scarlet. Mariana rocked back on her boot heels, a smirk spreading across her face.

As voices rose around her, followed by the rank odor of damp wool and unwashed males, Mariana felt the beginnings of a headache. To take her mind off it, she asked Thomières, “What are they talking about? And who is that Russian?”

He laughed, a soft sound but not derisive. She was glad since she rarely spoke to him at length. “I haven’t the slightest idea what they’re talking about, but that’s Prince Pyotr Ivanovich Bagration the marshal’s talking to.” He laughed again, this time even softer as if he worried someone might overhear. “Talking now, fighting later. Fine looking general, though, don’t you think?”

“Indeed he is,” Mariana said. With his chiseled features and thick, dark hair, the tall, slender Russian looked a little like Jean. Big rooster and bantam rooster, she thought, and almost hooted with laughter. When she could trust herself to speak, she asked, “What’s in the bottles?”

“Vodka. Have you never tasted it?”

“I’ve never even heard of it.”

“Then allow me, lieutenant,” Thomières said and escorted her to the nearest table. Rummaging among the glasses, he found two relatively clean ones and filled them from one of the bottles. “Salut,” he said, threw back his head, and drank it down.

She sniffed at the clear liquid. It had no odor. Since Thomières was still standing, how dangerous could it be? She drank hers in a single gulp, and the alcohol burned all the way to her stomach, where it exploded. Tears flooded her eyes, she sneezed and then coughed. One cough led to several until Thomières pounded her on the back and filled her glass.

“Quick—drink this.”

She did and stopped coughing. This time the vodka felt smooth as silk, and she grinned at the senior aide. “You should have warned me.”

“And miss your reaction?” He filled her glass for the third time, but before she could drink it, four Russian officers joined them at the table, clutching their glasses filled to the brim and sloshing onto their dingy white gloves. Their faces were clean-shaven except for amazingly full side-whiskers, their cheeks brick red in the candlelight. Raising their glasses, they shouted in unison, “Za vashe zdorovye!” When they had downed every last drop, they tossed their glasses toward the fireplace. The sound of shattering crystal brought to a halt every conversation in the spacious room, and then other Russians began throwing their empty glasses to the floor.

“Why not?” Thomières said and threw his glass toward the hearth.

“Indeed!” Mariana replied and threw hers, too.

Whatever Jean and Bagration may have been discussing, or whatever Prince Murat may have believed about the alleged truce, or whatever the French and Russian officers thought about the prospect of imminent hostilities between them, everything disappeared beneath the sharp-edged sound of crystal shattering and the roars of toasts in French and Russian. Mariana linked arms with Thomières to keep from reeling and tried to get her tongue around the consonant-laden Russian words. Somehow, they sounded more satisfactory than light, polite French phrases and better suited to the vodka, of which she had become quite fond in no time at all.

Jean summoned aides and staff officers with a sharp whistle that penetrated the merriment and stalked out of the villa and into the icy, starlit night. The sudden cold jolted Mariana from her torpor, and the sharp air stung her eyes and nose. Her comrades showed similar symptoms of waking from a muddled sleep, and she wondered what might have happened had they stayed and emptied all those bottles.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

While in August and September 1805 Max Joseph and Montgelas were still trying to enter into an alliance with France without making an enemy of the Austrians, a certain Colonel Beaumont was travelling through southern Germany scouting out the situation for Napoleon. This friendly gentleman might seem familiar to some, for he looked something like this:

And, would you believe it, it seems he managed to slip through completely incognito, then met with Napoleon in Strasbourg and took command of the cavalry of the Grande Armée, heading off on its triumphant march. Empress Josephine and Foreign Minister Talleyrand stayed behind in Strasbourg.

In Würzburg, Max Joseph still acted the innocent - especially to his spouse - but not for much longer. The reports by French envoy Otto from Würzburg to Talleyrand are sometimes pretty exhilarating. You can really see how frustrated the poor fellow is because, as he puts it, he cannot “make a hero out of a prince who has neither the disposition nor the inclination to become one".

Max Joseph certainly did not want to become a hero. But when he received the Austrian ambassador in Würzburg innocently and in a friendly manner, despite the fact that the Austrians had occupied Munich in the meantime, even Montgelas was on the verge of handing in his resignation.

The whole thing ended rather abruptly on 27 September, when this gentleman's army corps, coming from Hanover, arrived in Würzburg:

Now Max Joseph had to do two things: sign the alliance treaty with France - and come clean with Electress Karoline. After that, marital relations in the Wittelsbach household were somewhat strained for a while.

Bernadotte rallied the 24,000 Bavarian soldiers and marched off - through neutral Prussian Ansbach - to liberate Munich, evacuated by the Austrians without a fight.

On top of everything, Max Joseph's son Ludwig (still travelling, still opposed to Napoleon) contacted him from neutral Switzerland and asked for instructions: should he report to Austrian headquarters right away? Because his dear Papa surely wasn't going to...

Unfortunately, dear Papa had. And Electoral Prince Ludwig, rather than joining the Austrian commander-in-chief Mack, was sent to Strasbourg to see Empress Josephine. To his luck. Mack was forced to surrender in Ulm on October 20, and Josephine was thrilled to meet her son's potential future brother-in-law - even if she didn't say a syllable about any marriage.

Less enthusiastic was Electress Karoline, who now had serious worries about her stepdaughter Auguste with regards to this Beauharnais fellow. Even though her husband still maintained that he would never agree to such a shameful marriage for his daughter. Together with Auguste's governess, a Baroness von Wurmb, Karoline devised a plan to send Auguste to Max Joseph's sister, the Electress of Saxony. Due to the uncertain situation (Prussia also began to adopt a hostile attitude towards France), the plan did not come to fruition.

#napoleon#max joseph#karoline von bayern#joachim murat#colonel beaumont#auguste von bayern#eugene de beauharnais#eugene's marriage#montgelas#louis-guillaume otto#bavaria#1805#Third Coalition War

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: Who are some women in history that would be comparable to Napoleon or Alexander? Women who rose to power because they sought greatness and not because they used the feminine form to seduce for an easier life? How can the feminine mind come out of the mentality of being “the weaker sex”?

The short answer is that there are no women in history comparable to Napoleon or Alexander but equally I would quickly add that there are no other men in history either. These two contrasting men are unique. Alexander and Napoleon share similarities in their warfare, and how they used it to conquer and establish new lands. Both left legacies in which their very name has been equally loathed and loved down the ages. But they were unique.

Both were outsiders whose personal qualities rose above obstacles. Alexander was Macedonian and the Greeks looked down upon him as uncultured barbarian in the same way Napoleon was Corsican nobility and the old French aristocracy pulled up their noses in snobbish superiority. And yet able to rise through the grit of discipline and learning, luck and skill.

Both were great battle field commanders with a greater understanding of how to use one’s forces at hand to the terrain. Both were not quite true innovators as many might imagine. Alexander's military brilliance is beyond dispute but the groundwork for his superior tactics and strategies were laid by his father Philip of Macedon. Much of Napoleon’s greatness relied on the conscription model that the French revolutionary wars ushered in.

Alexander used new technology in new ways, invented new formations, and used his battlefield successes to accomplish his strategic goals with the innovative use of propaganda that was unseen before. Alexander was very unmatched in winning battles against much larger enemy formations as he was often outnumbered 2:1. He was a tactical genius in finding the weakness in the enemy’s lines and making the surgical strike necessary to ensure victory. He was quick witted at being able to make quick tactical decisions in the thick of the battle.

He was able to snatch victory from the claws of certain defeat, time and again, always against overwhelming enemy superiority in numbers, always in a terrain that his enemies had carefully chosen to maximise their advantages.

Any city he ever attacked he conquered. His own father the great Philip II failed to take Byzantium, and was defeated by Thracian tribesmen, but not Alexander. He made land out of a sea and conquered the heavily fortified island city of Tyre, and he used rock climbers to take the Sogdian Rock in Bactria/Afghanistan, an impregnable citadel that was compared to an eagle’s nest. Moreover he never lost a battle.

Napoleon was a brilliant general and even in his time earned grudging respect from his enemies. Napoleon was very successful in most of his military campaigns, and that laid the foundation necessary for his political achievements.

He fought 60 battles in his career, losing only 8 with two being considered “tactical victories” only (Second Bassano and Aspern-Esseling) . Nevertheless in the vast majority of his defeats (as well as victories) he was horrendously outnumbered, logistical suffocated, or betrayed by his allies.

He was exceptionally talented both strategically and tactically. In campaign after campaign he defeated larger armies with a smaller force, through methods like moving boldly and quickly, defeating them in detail, cutting off their lines of retreat, and doing what his enemies least expected.

Less glamorously but even more important he was great at logistics. One of his most famous maxims is that, “An army marches on its stomach.” If troops are not well equipped and well fed, they can not be expected to fight well. Napoleon had his armies live off the land, and marched faster than his enemies. While Napoleon still had supply lines, much of the food, clothing, and pay for his men was looted from conquered territory. This allowed him to march faster, and he often did forced marches where his men would march twice as far each day as the enemy predicted.

His opponents were often shocked at how quickly he outmanoeuvred them. At Ulm he surrounded an enormous Austrian army and forced them to surrender - while they thought he was over a hundred miles to the west and were waiting for reinforcements. Again, another thing that got him into trouble in Russia: the Russians retreated even faster, and burned everything in their wake, so there was nothing to loot.

He was innovative too in his use of light horse artillery - smaller cannons were pulled by fast horses, ridden by their crew - who could get into position rapidly and move into a new area when required. Napoleon loved these guys and used them in combination with his slower artillery to great effect often in support of heavy artillery.

Both were inspirational leaders of men in battle. In Alexander’s case he almost killed himself jumping into the Indian city of the Malians alone, a wound which weakened his body and eventually probably contributed to his death. He was simply fearless. Like the Carthagenian Hannibal, and all ancient Greek military leaders, Miltiades, Epameinondas, Philipos II, etc, and Romans, like Caesar, Alexander was always leading from the front line. In Napoleon’s case he too was fearless At Arcole he tried to inspire his men to attack, by grabbing a flag and stood in the open on the dike about 55 paces from the bridge. Both were loved by their men and their very presence on the battlefield was an inspiration to their fighting men.

Both were superb political strategists who were able to build on military gains with statecraft skills. Alexander the Great’s strong perseverance and incredible battle strategies led to increase his power over his empire. Napoleon used his intelligence and skill of manipulation to earn respect and support from the French people, which gained him great power.

For all this, they were both losers in the end. Both lost because they failed the most valuable lesson history can give: success is a bad teacher. Their military victories made them increasingly cocky and their political gains made them overreach. In the end their own personal qualities that brought them so much unprecedented success was the harbinger of their downfall.

So we are left with the question: what is greatness? The judgement of history seems to suggest that glory is fleeting but true greatness lasts the test of time.

There are simply too many women to list that would be worthy of anyone’s attention to show that women have achieved greatness throughout history.

Here is a good basic list of warrior women in recorded history https://www.rejectedprincesses.com/women-in-combat

Indeed one doesn’t have to stray too far from antiquity to show that women as warriors did make an impact.

I shall just focus on a few from antiquity that stand out for me and and a few more modern choices that are very personal to me.

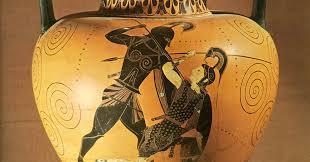

Penthesilea

I had heard of Penthesilea and the Amazons before as a small girl. But the first time I really understand just how impressive and unusual it was in the ancient world to be a woman who “fights with men” was when I was taking Latin at my English girls’ boarding school. Contrary to popular belief, Penthesilea’s story isn’t actually told in the Iliad (which ends with Hector’s funeral, before the Amazons arrive), but in a lost ancient epic called Aethiopis. This poem continued the story of Achilles’ great deeds, which included the killing of several famous warriors—Memnon, King of Aethiopia, and Penthesilea most prominent among them.

The Amazons had a number of famous Queens, but Penthesilea is perhaps the most storied. She was a daughter of the war-god Ares, and Pliny credits her with the invention of the battle-ax. She was also sister to Hippolyta, who married the hero Theseus, after being defeated by him in battle. Penthesilea ruled the Amazons during the years of the Trojan war—and for most of that time stayed away from the conflict. However, after Achilles killed Hector, Penthesilea decided it was time for her Amazons to intervene, and the group rode to the rescue of the Trojans—who were, after all, fellow Anatolians. Fearless, she blazed through the Greek ranks, laying waste to their soldiers.

During the battles, Penthesilea was not a queen who sat by and watched the men fight. She was a warrior in the truest sense. It is said that she blazed through the Greeks like lightning, killing many. It is written that she was swift and brave, and fought as valiantly and successfully as the men. She wanted to prove that the Amazons were great warriors. She wanted to kill Achilles to avenge the death of Hector, and she wanted to die in battle. I love Vergil’s glorious description of her in battle: “The ferocious Penthesilea, gold belt fastened beneath her exposed breast, leads her battle-lines of Amazons with their crescent light-shields…a warrioress, a maiden who dares to fight with men.”

Although Penthesilea was a ferocious warrior, her life came to an end, at the hands of Achilles. Achilles had seen her battling others, and was enamored with her ferocity and strength. As he fought, he worked his way towards her, like a moth drawn to a flame. While he was drawn to her with the intention of facing her as an opponent, he fell in love with her upon facing her. However, it was too late.

Achilles defeated Penthesilea, catching her as she fell to the ground. Greek warrior Thersites mocked Achilles for his treatment of Penthesilea’s body after her death. It is also said that Thersites removed Penthesilea’s eyes with his sword. This enraged Achilles, and he slaughtered Thersites. Upon Thersites’ death, a sacred feud was fought. Diomedes, Thersite’s cousin, retrieved Penthesilea’s corpse, dragged it behind his chariot, and cast it into the river. Achilles retrieved the body, and gave her a proper burial. In some stories, Achilles is accused of engaging in necrophilia with her body. In other legends, it is said that Penthesilea bore Achilles a son after her death. Yes, I agree, that does feel creepy.

Penthesilea’s life and death were tragic. She is portrayed as a brave and fierce warrior who was deeply affected by the accidental death of her sister. This grief, compounded with her desire to be a strong warrior who would die an honourable death on the battlefield, led her to Troy, where her tragic death weakened Troy, but also led to unrest in the Greek camps due to her death’s impact on Achilles and his revengeful acts. In the end, she died the ‘honorable’ death on the battlefield that she had longed for, at the hands of the legendary Achilles, no less.

The heroines of Greek mythology tend towards thoughtfulness, fidelity and modesty (Andromache, Penelope), while the daring and headstrong personalities generally go to the antagonists–Medea, Clytemnestra, Hera. But Penthesilea is something else entirely: a woman who meets men on her own terms, as their equal. Perhaps in honour of this, Virgil doesn’t give her the standard heroine epithet of “beautiful.” For him, it is her majesty and obvious power that make her notable, not her looks.

By the way, the word that Virgil uses for warrioress is bellatrix, the inspiration for Bellatrix Lestrange’s name in the Harry Potter books. So she lives on in immortality through our modern day Virgil, J.K. Rowling (just kidding)

Cynane (c. 358 – 323 BC)

Cynane was the daughter of King Philip II of Macedon and his first wife, the Illyrian Princess Audata. She was also the half-sister of Alexander the Great. Audata raised Cynane in the Illyrian tradition, training her in the arts of war and turning her into an exceptional fighter – so much so that her skill on the battlefield became famed throughout the land. Cynane accompanied the Macedonian army on campaign alongside Alexander the Great and according to the historian Polyaenus, she once slew an Illyrian queen and masterminded the slaughter of her army. Such was her military prowess. Following Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, Cynane attempted an audacious power play. In the ensuing chaos, she championed her daughter, Adea, to marry Philip Arrhidaeus, Alexander’s simple-minded half-brother who the Macedonian generals had installed as a puppet king. Yet Alexander’s former generals – and especially the new regent, Perdiccas – had no intention of accepting this, seeing Cynane as a threat to their own power. Undeterred, Cynane gathered a powerful army and marched into Asia to place her daughter on the throne by force.

As she and her army were marching through Asia towards Babylon, Cynane was confronted by another army commanded by Alcetas, the brother of Perdiccas and a former companion of Cynane. However, desiring to keep his brother in power Alcetas slew Cynane when they met – a sad end to one of history’s most remarkable female warriors. Although Cynane never reached Babylon, her power play proved successful. The Macedonian soldiers were angered at Alcetas’ killing of Cynane, especially as she was directly related to their beloved Alexander. Thus they demanded Cynane’s wish be fulfilled. Perdiccas relented, Adea and Philip Arrhidaeus were married, and Adea adopted the title Queen Adea Eurydice.

Olympias and Eurydice

The mother of Alexander the Great, Olympias was one of the most remarkable women in antiquity. She was a princess of the most powerful tribe in Epirus (a region now divided between northwest Greece and southern Albania) and her family claimed descent from Achilles. Despite this impressive claim, many Greeks considered her home kingdom to be semi-barbarous – a realm tainted with vice because of its proximity to raiding Illyrians in the north. Thus the surviving texts often perceive her as a somewhat exotic character.

In 358 BC Olympias’ uncle, the Molossian King Arrybas, married Olympias to King Philip II of Macedonia to secure the strongest possible alliance. She gave birth to Alexander the Great two years later in 356 BC. Further conflict was added to an already tempestuous relationship when Philip married again, this time a Macedonian noblewoman called Cleopatra Eurydice.

Olympias began to fear this new marriage might threaten the possibility of Alexander inheriting Philip’s throne. Her Molossian heritage was starting to make some Macedonian nobles question Alexander’s legitimacy. Thus there is a strong possibility that Olympias was involved in the subsequent murders of Philip II, Cleopatra Eurydice and her infant children. She is often portrayed as a woman who stopped at nothing to ensure Alexander ascended the throne. Following Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, she became a major player in the early Wars of the Successors in Macedonia. In 317 BC, she led an army into Macedonia and was confronted by an army led by another queen: none other than Cynane’s daughter, Adea Eurydice.

This clash was the first time in Greek history that two armies faced each other commanded by women. However, the battle ended before a sword blow was exchanged. As soon as they saw the mother of their beloved Alexander the Great facing them, Eurydice’s army deserted to Olympias. Upon capturing Eurydice and Philip Arrhidaeus, Eurydice’s husband, Olympias had them imprisoned in squalid conditions. Soon after she had Philip stabbed to death while his wife watched on.

On Christmas Day 317, Olympias sent Eurydice a sword, a noose, and some hemlock, and ordered her to choose which way she wanted to die. After cursing Olympias’ name that she might suffer a similarly sad end, Eurydice chose the noose. Olympias herself did not live long to cherish this victory. The following year Olympias’ control of Macedonia was overthrown by Cassander, another of the Successors. Upon capturing Olympias, Cassander sent two hundred soldiers to her house to slay her.

However, after being overawed by the sight of Alexander the Great’s mother, the hired killers did not go through with the task. Yet this only temporarily prolonged Olympias’ life as relatives of her past victims soon murdered her in revenge.

Artemisia I of Caria (5th Century BC)

Named after the Goddess of the Hunt (Artemis), Artemisia was the 5th century BCE Queen of Halicarnassus, a kingdom that exists in modern-day Turkey. However, she was best known as a naval commander and ally of Xerxes, the King of Persia, in his invasion of the Greek city-states. (Yes, like in the action movie 300: Rise of an Empire.) She made her mark on history in the Battle of Salamis, where the fleet she commanded was deemed the best against the Greeks. Greek historian Herodotus wrote of her heroics on this battlefield of the sea, painting her as a warrior who was decisive and incredibly intelligent in her strategies. This included a ruthless sense of self-preservation. With a Greek vessel bearing down on her ship, Artemisia intentionally steered into another Persian vessel to trick the Greeks into believing she was one of them. It worked. The Greeks left her be. The Persian ship sank. Watching from the shore, Xerxes saw the collision and believed Artemisia had sunk a Greek enemy, not one of his own.

For all of this, her death was not one recorded in a great battle, but in legends written by the victors, the Greeks - so one must obviously be skeptical of accepting what they said as 100% truth. It's said that Artemisia fell hard for a Greek man, who ignored her to his detriment. Blinded by love, she blinded him in his sleep. Yet even with him disfigured, her passion for him burned. To cure herself, she set to leap from a tall rock in Leucas, Greece, which was believed to break the bonds of love. Instead, it broke Artemisia's neck. She's said to be buried nearby.

But much like Penthesilea, she lives on in our modern culture, but arguably more dubiously through Hollywood in the sub-par action movie 300: Rise of an Empire. Now I forever think of Artemisia as the beautiful and sultry French actress, Eva Green.

Boadicea (also written as Boudica)

Boadicea was a Celtic queen who led a revolt against Roman rule in ancient Britain in A.D. 60 or 61. As all of the existing information about her comes from Roman scholars, particularly Tacitus and Cassius Dio, little is known about her early life; it’s believed she was born into an elite family in Camulodunum (now Colchester) around A.D. 30.

At the age of 18, Boudica married Prasutagas, king of the Iceni tribe of modern-day East Anglia. When the Romans conquered southern England in A.D. 43, most Celtic tribes were forced to submit, but the Romans let Prasutagas continue in power as a forced ally of the Empire. When he died without a male heir in A.D. 60, the Romans annexed his kingdom and confiscated his family’s land and property. As a further humiliation, they publicly flogged Boadicea and raped her two daughters. Tacitus recorded Boudicca’s promise of vengeance after this last violation: “Nothing is safe from Roman pride and arrogance. They will deface the sacred and will deflower our virgins. Win the battle or perish, that is what I, a woman, will do.”

Like other ancient Celtic women, Boadicea had trained as a warrior, including fighting techniques and the use of weapons. With the Roman provincial governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus leading a military campaign in Wales, Boadicea led a rebellion of the Iceni and members of other tribes resentful of Roman rule. After defeating the Roman Ninth Legion, the queen’s forces destroyed Camulodunum, then the captain of Roman Britain, and massacred its inhabitants. They went on to give similar treatment to London and Verulamium (modern St. Albans). By that time, Suetonius had returned from Wales and marshaled his army to confront the rebels. In the clash that followed–the exact battle site is unknown, but possibilities range from London to Northamptonshire–the Romans managed to defeat the Britons despite inferior numbers, and Boadicea and her daughters apparently killed themselves by taking poison in order to avoid capture.

In all, Tacitus claimed, Boadicea’s forces had massacred some 70,000 Romans and pro-Roman Britons. Though her rebellion failed, and the Romans would continue to control Britain until A.D. 410, Bouadicea is celebrated today as a British national heroine and an embodiment of the struggle for justice and independence.

Queen Zenobia