#supreme court justice Jim johnson

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On August 21, 1959, Jim Johnson, an Arkansas supreme court justice, told a state-wide segregationist rally at Pine Bluff, Arkansas, to “do what needs to be done” to fight the proposed integration of schools in the Dollarway School District. “When Dollarway falls,” Johnson exhorted the crowd, “Arkansas falls!” The crowd of over a thousand white Arkansas residents cheered.

On August 4, a federal judge ordered that three Black children be admitted to the Dollarway School District when schools reopened in September. The Dollarway School Board appealed the decision. Meanwhile, white residents in the Dollarway District put together a petition with over 1,200 signatures asking Governor Orval Faubus to preserve segregation in the district “with all the force at your command.”

Though Brown v. Board of Education determined in 1954 that school segregation was unconstitutional, for years white residents across Arkansas relied on intimidation and organized political resistance to maintain segregation in the public schools. White residents fought court rulings and held intimidation rallies to terrorize Black families and their children while politicians closed schools to avoid integration. By 1960, only 98 of Arkansas’s 104,000 Black students attended integrated schools.

Justice Jim Johnson was an outspoken segregationist who served as an Arkansas state senator and associate justice on the Arkansas Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s. After the Brown decision, Justice Johnson launched a campaign to ensure that defense of segregation remained a central political platform in Arkansas. Justice Johnson formed the White Citizens’ Council of Arkansas, which protested plans to integrate schools in the town of Hoxie, and proposed an amendment to the Arkansas Constitution that would authorize state officials to ignore federal law, which Arkansas voters passed. In 1956, Justice Johnson challenged incumbent Orval Faubus and ran for governor on a segregationist platform with the endorsement of the KKK. Although Justice Johnson lost the election, he leveraged his supporters to pressure Governor Faubus to embrace the segregationist cause. He was instrumental in persuading Governor Faubus to defy federal orders to desegregate Little Rock Central High School in 1957.

The massive resistance to integration by the white community was largely successful in preventing integration of schools, especially in the South. In the five Deep South states, every single one of 1.4 million Black schoolchildren attended segregated schools until the fall of 1960. By the start of the 1964-65 school year, less than 3% of the South’s Black children attended school with white students, and in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina that number remained substantially below 1%. In 1967, 13 years after Brown v. Board of Education, a report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights observed that white violence and intimidation against Black people “continues to be a deterrent to school desegregation.” Learn more about this history by reading EJI’s report, Segregation in America. You can also learn more about segregationist leaders like Justice Johnson, including his wife Virginia Johnson, here.

#history#white history#us history#am yisrael chai#republicans#black history#democrats#Segregation in America#racial segregation#segregation#american history#civil rights#civil rights history#jumblr#kkk#ku klux klan#authoritarianism#Jim Johnson#Arkansas#supreme court justice#supreme court justice Jim johnson#Jim johnson supreme court justice#Pine Bluff#Dollarway School District#Brown v. Board of Education#education#american apartheid#apartheid#end the apartheid#israel is an apartheid state

1 note

·

View note

Text

Birthdays 1.22

Beer Birthdays

Pat Hagerman (1964)

James Renfrew (1965)

Motor (1966)

Bud Bundy, character on Married… with Children, named after Al Bundy's favorite beer (1975)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Francis Bacon; writer, philosopher (1561)

Sergei Eisenstein; Russian director & screenwriter (1898)

Robert E. Howard; fantasy writer (1906)

J.J. Johnson; jazz trombonist, bandleader (1924)

Diane Lane; actress (1965)

Famous Birthdays

Andre Marie Ampere; physicist (1775)

George Balanchine; choreographer (1904)

Bill Bixby; actor (1934)

Richard Blackmore; English physician & poet (1654)

Linda Blair; actress (1959)

Ed Bradley; television journalist (1941)

Ernst Busch; German actor and singer (1900)

Lord Byron; poet (1788)

Seymour Cassel; actor (1935)

Caitlin Clark; basketball player (2002)

Sam Cooke; musician (1931)

Douglas "Wrong Way" Corrigan; pilot (1907)

Olivia d'Abo; actor (1967)

John Donne; English poet & cleric (1573)

Joe Esposito; author (1938)

Guy Fieri; chef, author, and tv host (1968)

Willa Ford; singer-songwriter & actress (1981)

Pierre Gassendi; French mathematician, astronomer & philosopher (1592)

D.W. Griffith; film director (1875)

Martti Haavio; Finnish poet and mythologist (1899)

Alan J. Heeger; physicist and chemist (1936)

Helen Hoyt; poet and author (1887)

John Hurt; actor (1940)

Michael Hutchence; rock singer (1960)

Jim Jarmusch; film director (1953)

DJ Jazzy Jeff; musician (1965)

Graham Kerr; chef, "Galloping Gourmet" (1934)

William Kidd; Scottish sailor and pirate hunter (1645)

Nicolas Lancret; French painter (1690)

Piper Laurie; actor (1932)

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, German philosopher & author (1729)

Malcolm McLaren, English singer-songwriter & manager

Charles Morgan; writer (1894)

Steve Perry; rock musician (1949)

Francis Picabia; French painter and poet (1878)

Walter Raleigh; English poet, soldier, & explorer (1552)

Ray Rice; Baltimore Ravens RB (1987)

George "Chuck" Seifert; San Francisco 49ers coach (1940)

John Wesley Shipp; actor (1956)

Ann Sothern; actress (1909)

August Strindberg; Swedish novelist, poet, & playwright (1849)

Hikaru Walter Sulu; Star Trek character (2179)

Conrad Veidt; German-American actor, director (1893)

Frederick Vinson; supreme court chief justice (1890)

Joseph Wambaugh; writer (1937)

John Winthrop; politician (1588)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Isobel Santos

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

October 25, 2023

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

OCT 26, 2023

Today, the United States House of Representatives elected a new speaker to replace former speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), who was ousted by Republican extremists. The new speaker, Representative Mike Johnson of Louisiana, had an advantage over rivals because he has been a backbencher in the House fewer than eight years, too invisible to have made many enemies. He is the least-experienced speaker in more than a century.

Senate Republicans openly admitted they didn’t know who he was. Senator Mitt Romney (R-UT) added: “Apparently experience isn’t necessary for the speaker job…. We’re down to folks who haven’t had leadership or chairmanship roles, which means their administration of the House will be a new experience for them.”

The Republican conference decided to back Johnson after extremists scuttled their first choice after McCarthy, Louisiana representative Steve Scalise, and after a block of Republicans refused to back Trump loyalist Jim Jordan of Ohio. After Jordan, Minnesota representative Tom Emmer got the nod from the conference…until former president Trump expressed his disapproval.

Democrats repeatedly offered to work with Republicans to elect a speaker who accepted the results of the 2020 presidential election and who agreed to bring to the floor for an up-or-down vote legislation that was widely popular in both parties. The Republicans rejected those offers.

Instead, they have elected a pro-Trump extremist as speaker.

Johnson was instrumental in Trump’s attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. Routinely in touch with Trump, he rallied his colleagues to object to counting the electoral votes from states that Democratic candidate Joe Biden won. As Trump’s legal challenges to the results failed, Johnson pushed a Texas lawsuit against the four states that had given Biden the win, calling for the invalidation of millions of his fellow Americans’ ballots, and echoed lies about Venezuelan interference with ballots.

Johnson has also embraced the far right’s culture wars. He is a self-described evangelical Christian who is staunchly anti-abortion, anti-LGBTQ rights, anti-union, and anti-immigration. He has close ties to the Israeli right wing, and he opposes further aid to Ukraine, saying such money would be better spent at home, but he has also called for extensive cuts to domestic spending programs.

When a reporter asked Johnson about his efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election, the colleagues surrounding him booed and told the reporter to “shut up.” On the floor of the House, every single Republican voted for Johnson.

And so, the House Republicans have caved to the MAGA extremists. Representative Pete Aguilar (D-CA) said that for the Republicans, the search for a speaker hadn’t been about looking for someone interested in “growing the middle class, helping our communities, keeping the cost of healthcare lower, and making life for everyday Americans better.” Instead, Aguilar said, “this has been about one thing…who can appease Donald Trump. House Republicans have put their names behind someone who has been called the most important architect of the [2020] electoral college objections.” A Republican yelled back: “Damn right!”

The Republicans appear to be planning to go before the voters in 2024 with a presidential candidate who is deeply enmeshed in trials over allegedly criminal behavior, whose hastily appointed Supreme Court justices overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision recognizing the constitutional right to abortion, and who tried to steal the 2020 election. Alongside him, they have now elevated a fervently anti-abortion House speaker who backed the former president’s effort to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election.

Voters resoundingly rejected both of those positions in 2022.

In contrast to his Republican colleagues, in his welcome to the new speaker, House minority leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) outlined his caucus’s efforts to work with Republicans in a bipartisan way, noting that it was the Democrats who provided the votes to raise the debt ceiling, to pass a continuing resolution to fund the government and thus avoid a shutdown, and to secure disaster assistance for Americans suffering from extreme weather events.

Going forward, he said, House Democrats will “continue to push back against extremism in this chamber and throughout the country. House Democrats will continue to protect Social Security, protect Medicare, protect Medicaid, protect our children, protect our climate, protect low-income families, protect working families, protect the middle class, protect organized labor, protect the LGBTQ community, protect our veterans, protect older Americans, protect the Affordable Care Act, protect the right to vote, protect the peaceful transfer of power, protect our democracy, and protect a woman's freedom to make her own reproductive health care decision.”

But Jeffries’s soft speech covered a steely message. He observed that “Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election,” adding that “[h]e’s doing a great job under difficult circumstances, and no amount of election denialism will ever change that reality.”

Jeffries pointed out that great presidents of both parties have urged House members to “put aside partisan politics for the good of the American people,” and he noted that Americans are “understandably alarmed at the turbulence of the moment, at the chaos, the dysfunction, and the extremism that has been unleashed in this chamber, from the very beginning of this Congress.” But in what amounted to a warning to the newly empowered extremists, he continued: “But this, too, shall pass. Our country has often confronted adversity, and the good news is we always find a way to make it to the other side.”

“We faced adversity in the 1860s, in the middle of the Civil War, when the country was literally tearing itself apart. We faced adversity in October of 1929 when the stock market collapsed, plunging us into a Great Depression. We faced adversity in December of 1941, when a foreign power unexpectedly struck, plunging us into a world war with the evil empire of Nazi Germany.

“We faced adversity in the Deep South in the 1950s and 60s, when the country was struggling to reconcile the inherent contradictions between Jim Crow segregation and the glorious promises of the Constitution. We faced adversity on September 11th, 2001, when the Towers and the Pentagon were unexpectedly struck, killing thousands of lives in an instant.”

And then, by placing House Republicans in this list, Jeffries tied them to the wrong side of history. “We faced adversity right here in the House of Representatives when on January 6, 2021, a violent mob of insurrectionists incited by some in this chamber overran the House floor as part of an effort to halt the peaceful transfer of power,” he said.

And, he concluded, “[e]very time we faced adversity, the good news here in America is that we always overcome….”

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Heather Cox Richardson#Letters From An American#House Republicans#democracy#authoritarianism#Mike Johnson

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

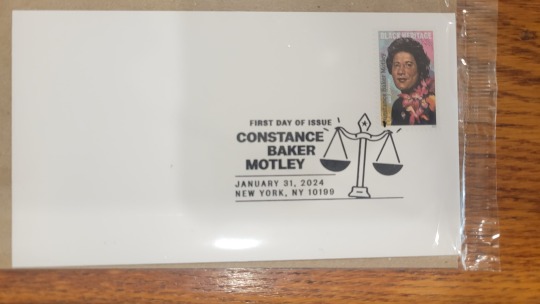

Constance Baker Motley

My dad gave me, my brother, and my daughter each this commemorative stamp of Constance Baker Motley. She was influential on his career - my dad worked at NAACP Legal Defense Fund and became a judge just as she did. So today I'm showing what AI says about her life and legacy. I showed perlexity results first and as the son of a librarian I am fast falling for it and how they integrate and cite sources for their answers.

From Perplexity:

Constance Baker Motley (September 14, 1921 – September 28, 2005) was an influential American jurist and politician. She made significant contributions to the civil rights movement and the legal profession. Motley was the first African American woman to serve as a federal judge, having been appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966. Prior to her judgeship, she was a prominent civil rights lawyer and a key figure in the legal battle against racial segregation. From 1945 to 1964, she worked on major school segregation cases supported by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and she personally led the litigation that integrated several universities in the southern United States. Motley's work was instrumental in advancing civil rights and promoting equal justice under the law. Her legacy continues to inspire generations of lawyers and judges, particularly women and people of color, to pursue careers in the legal profession. She was a trailblazer and a champion of justice, leaving a lasting impact on the American judicial system and society as a whole[1][2][4][5].

Citations: [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constance_Baker_Motley [2] https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2020/02/20/constance-baker-motley-judiciarys-unsung-rights-hero [3] https://blackhistory.news.columbia.edu/people/constance-baker-motley [4] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Constance-Baker-Motley [5] https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2023/03/01/women-judges-reflect-constance-baker-motleys-legacy

Constance Baker Motley worked on all of the major school segregation cases supported by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund from 1945 to 1964. She personally led the litigation that integrated several universities in the southern United States. She was the first Black woman to argue at the Supreme Court and argued 10 landmark civil rights cases, winning nine. Her work was instrumental in advancing civil rights and promoting equal justice under the law[1][2][3][4][5].

Citations: [1] https://blackhistory.news.columbia.edu/people/constance-baker-motley [2] https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/constance-baker-motley/ [3] https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2020/02/20/constance-baker-motley-judiciarys-unsung-rights-hero [4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constance_Baker_Motley [5] https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2023/03/01/women-judges-reflect-constance-baker-motleys-legacy

From Bard:

Champion of Justice: Constance Baker Motley and the Legal Fight for Civil Rights

Constance Baker Motley, a name synonymous with courage, brilliance, and unwavering commitment to justice, etched her legacy in the annals of American legal history. As a lawyer for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), she spearheaded landmark cases that dismantled the edifice of Jim Crow segregation, paving the way for a more equitable nation. This essay delves into the remarkable life and career of Motley, highlighting her legal prowess, strategic acumen, and profound impact on the Civil Rights Movement.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1924, Motley faced racial discrimination from a young age. This ignited a passion for justice within her, leading her to pursue law at Columbia University, where she excelled despite being the only Black woman in her class. Joining the LDF in 1946, she embarked on a journey that would reshape the legal landscape of America.

Motley's legal acumen shone brightly in numerous cases. In the landmark Brown v. Board of Education, she co-authored the legal brief and played a crucial role in dismantling the doctrine of "separate but equal." Notably, she strategically selected cases challenging segregation in universities, understanding that education was key to unlocking opportunities for Black Americans. Victories in cases like Meredith v. Fair, which desegregated the University of Mississippi, and Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, which integrated Mississippi public schools, stand as testaments to her dedication to equal access to education.

Motley's brilliance extended beyond courtroom arguments. She possessed a profound understanding of the social and political dynamics of the South, crafting legal strategies that resonated with communities and garnered public support. In the Birmingham Children's Crusade, she secured the release of arrested children and protected Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. from legal persecution, ensuring the movement's momentum.

Her impact transcended individual victories. Motley's tireless efforts contributed significantly to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, dismantling legal barriers to equality. She later served as a federal judge, continuing her fight for justice from the bench.

Constance Baker Motley was not just a lawyer; she was a force of nature who embodied the spirit of the Civil Rights Movement. Her legacy extends far beyond legal victories, inspiring generations of lawyers and activists to fight for equality. By refusing to accept the status quo, she challenged a nation to live up to its ideals of justice and opportunity.

Further Reading:

Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality by Tomiko Brown-Nagin

One Woman's Fight: Constance Baker Motley and the Civil Rights Movement by Mary Beth Norton

Lifting as We Climb: African American Women's History from 1830 to 1990 by Evelyn Brooks Barnett

Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Global Struggle for Equality by Angela Davis

We Shall Overcome: A History of the American Civil Rights Movement by Charles M. Payne

Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Battle for All Americans by Dwight D. Eisenhower, Blanche Wiesen Cook, & Milton Eisenhower

Letter from a Birmingham Jail by Martin Luther King Jr.

My Beloved World by Sonia Sotomayor

Sisters in Law: How Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sandra Day O'Connor Changed the Course of American Justice by Linda Hirshman

Crusader for Justice: The Autobiography of Constance Baker Motley (Edited by Molly Yard)

By exploring these works, you will gain a deeper understanding of Constance Baker Motley's remarkable life, her pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement, and the enduring impact of her legacy on American society. Remember, her story is not just a chapter in history; it serves as a call to action, urging us to continue the fight for a just and equitable future for all.

From ChatGPT:

Constance Baker Motley: A Trailblazer in Law and Civil Rights

Introduction: Constance Baker Motley, a pioneering figure in American legal history, made indelible contributions to the advancement of civil rights and the legal profession. Her career spanned several decades, during which she played a crucial role in landmark civil rights cases, both as an attorney and as the first African American woman appointed to the federal bench. This essay explores the impact of Constance Baker Motley on law and civil rights, focusing on some of the most important cases she worked on.

Early Career and Legal Activism: Constance Baker Motley began her legal career as a law clerk for Thurgood Marshall at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF). In this role, she was involved in groundbreaking cases that aimed to dismantle segregation and promote racial equality. Notably, she worked on Brown v. Board of Education (1954), a landmark case that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional.

School Desegregation Cases: Motley continued her work on school desegregation cases, including Meredith v. Fair (1961), where she represented James Meredith, the first African American student admitted to the University of Mississippi. Her legal acumen and dedication to justice were evident as she navigated the intense legal battles and societal resistance surrounding desegregation.

Civil Rights Act of 1964: Motley played a pivotal role in the development and passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As a key strategist and draftsman, she contributed significantly to the legislation that aimed to end segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Key Role in Birmingham Campaign: Motley's involvement in civil rights extended beyond the courtroom. In 1963, she played a vital role in the Birmingham Campaign, working alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and other activists. Her legal expertise was integral to the success of this pivotal moment in the civil rights movement, which led to significant concessions from Birmingham's business community.

Judicial Career: Constance Baker Motley's impact on law and civil rights extended to her judicial career. In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed her as a federal judge for the Southern District of New York, making her the first African American woman to serve in a federal judgeship. Throughout her tenure, she continued to make decisions that promoted equality and justice.

Conclusion: Constance Baker Motley's legacy is a testament to her dedication to justice and equality. Her work in landmark civil rights cases and her historic appointment as a federal judge paved the way for future generations of African American attorneys and jurists. Constance Baker Motley's impact on law and civil rights is a beacon of inspiration, highlighting the transformative power of legal advocacy.

Sources:

Cook, R. (2018). Constance Baker Motley: A Biography. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Graham, S. H. (2011). Constance Baker Motley: One Woman's Fight for Civil Rights and Equal Justice under Law. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Motley, C. B. (1979). Equal Justice Under Law. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

Reading List:

"Constance Baker Motley: A Biography" by Gary L. Ford Jr.

"Constance Baker Motley: One Woman's Fight for Civil Rights and Equal Justice under Law" by Gary L. Ford Jr.

"Equal Justice Under Law" by Constance Baker Motley

"Becoming Justice Blackmun: Harry Blackmun's Supreme Court Journey" by Linda Greenhouse

"Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America's Struggle for Equality" by Richard Kluger

"The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change?" by Gerald N. Rosenberg

"May It Please the Court: The Most Significant Oral Arguments Made Before the Supreme Court Since 1955" by Peter Irons

"Race and Liberty in America: The Essential Reader" edited by Jonathan Bean

"The Birth of the West: Rome, Germany, France, and the Creation of Europe in the Tenth Century" by Paul Collins

"Making Our Democracy Work: A Judge's View" by Stephen Breyer

#black history month#chatgpt#perplexity#blackhistorymonth#civilrights#africanamericanhistory#justice#constance baker motley#NAACP LDF#naacp#equality#bard

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Next Targets in the Fight Against Affirmative Action

It won’t be admissions offices at selective schools but institutions and programs that use race as a plus factor in making decisions about who gets contracts, jobs, scholarships, and awards.

— By Nicholas Lemann | July 2, 2023

The U.S. Supreme Court building. It’s time to prepare for a long struggle that’s about much more than who gets into college.Photograph by Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Of the almost four thousand degree-granting colleges in the United States, only a very small portion are highly selective. These are the institutions that the Supreme Court’s decision striking down affirmative action in admissions will affect most directly. Surely all of them have been practicing affirmative action for years, and surely the Court’s decision comes as a surprise to none of them; it was clear after Donald Trump had appointed three Justices, and after the Court had decided to hear the cases challenging admissions policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina, where this was going. Colleges that have commented on the decision publicly have been disapproving. Most of them have stopped requiring that applicants submit standardized-test scores temporarily, but this exemption is likely to become permanent as a result of the Court’s decision, because, for half a century, test scores have been the primary evidence that people suing to get affirmative action abolished have used to support their claims that they have been victims of discrimination.

The selective schools have undoubtedly been planning their post-affirmative-action approach to admissions, which will include beefing up their staff so that they can make qualitative, rather than quantitative, choices, based on reading applicants’ folders. Many Black and Latino applicants will take solace in the lifeline Chief Justice John Roberts threw them in his majority opinion—referring to racial experiences in application essays will still be permissible. If there is a way to avoid devastating losses in their share of Black and Latino students, the selective colleges will find it. The vast majority of American college aspirants won’t be directly affected by the decision, because their prospective schools accept most of their applicants. For many of those students, the problem is not failure to be admitted but failure to graduate: more than a third of American college students don’t.

So why does this case elicit such intense passions on both sides, including a great deal of highly personal public feuding among the Justices in their opinions? To begin with, it taps into wildly different theories of American history. The conservative Justices’ opinions discern a golden thread (color blindness) running through the violence and tragedy of the past century and a half of racial law and policy: the Emancipation Proclamation; the post-Civil War Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution; Justice John Marshall Harlan’s lonely dissent in the Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision that upheld Jim Crow; the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (The Harvard and U.N.C. suits argue specifically that affirmative action violates the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act.) Now, at last, in the view of the conservative Justices, we can restore the primacy of the golden thread.

In fact, each of these historical moments was at the time seen as entirely racial, not color-blind, and none wound up installing a post-racist system that we now can restore. The Emancipation Proclamation, consecrated in our newest national holiday, Juneteenth, specifically permitted the continuation of slavery in areas controlled by the Union. The Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, initially failed to pass a Confederate-free House of Representatives. After the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson, as Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson pointed out in their dissents, vetoed the first national civil-rights law, whose text might be read today as racially neutral, because he felt it discriminated in favor of Black people. The Southern states strongly opposed the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, precisely because they conferred civil and voting rights on Black people, and ratified them only in order to be readmitted to the Union. After less than a decade, the former Confederacy had effectively nullified both amendments through a coördinated campaign of violent terrorism that the federal government grew weary of contesting. Closer to our time, after the civil-rights movement finally got the federal government to pay attention to race again, Presidents John F. Kennedy, in 1961, and Lyndon Johnson, in 1965, signed executive orders mandating affirmative action by government contractors—even though, as the golden-thread theory has it, they were merely trying to create a color-blind society. They did this because the country, particularly in its upper socioeconomic reaches, was almost completely segregated, whatever anti-discrimination provisions were being put into law. And today the vast majority of Black Americans still haven’t experienced a society that feels color-blind to them.

Selective colleges didn’t require much prodding to adopt affirmative-action admissions policies during the later stages of the civil-rights era. They did so for a clear, specific reason: to become more racially integrated. These colleges are mainly venerable institutions that are used to pursuing a number of not exactly congruent principles at the same time. Their claims to wanting to make the world a better place are sincere; they also like being academically élite and want to stay that way. That was why, within roughly the same period, they adopted both affirmative action and standardized admission testing, whose results can’t be dispositive if affirmative action is going to work. From the colleges’ perspective, this mix of admissions policies has worked very well: in the course of decades, they have become more integrated and more élite—and, from their own self-centered perspective, much more in demand and more important in the life of the country. It was not always the case that Supreme Court Justices, of all races, were graduates of highly selective colleges and law schools, but it is now.

Justice Neil Gorsuch opened his concurring opinion with this sentence: “For many students, an acceptance letter from Harvard or the University of North Carolina is a ticket to a brighter future.” This indicates a profoundly different idea about the purpose of selective-college admissions from the colleges’ own idea: that it should be a way of parcelling out something valuable and scarce to those who most deserve it. It’s a difficult project, because the gradations among applicants are so fine and because colleges are selecting from among adolescents who live at home, with all the advantages and disadvantages that confers. This may explain why class-based affirmative action, which selective colleges already practice, seems to be less widely resented than race-based affirmative action. But let’s not lose sight of the history. Affirmative action was born during a moment of racial crisis, and its purpose was specifically to integrate the colleges that instituted it, not to find the perfect means to confer Gorsuch’s ticket on the most deserving.

Supreme Court Justices have themselves experienced the cognitive dissonance inherent in selective colleges’ simultaneous embrace of academic élitism and racial justice, probably more than they have experienced both sides of most issues that come before them. From the very beginning (DeFunis v. Odegaard, 1974), the Court has had a noticeably hard time making up its mind about affirmative action in admissions. It has never got anywhere near unanimity; instead, it has produced a long string of fine-grained rulings, usually decided by one-vote majorities and elaborately qualified by concurrences and dissents. Justice Roberts’s majority opinion, in the Harvard and U.N.C. cases, adroitly brought to the fore all the decades of limitations that were required to produce any majority decision at all in these cases. One of these was the failure, in the 1978 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case, to get a fifth vote in favor of an endorsement of recompense for past wrongs as a justification for affirmative action. Another was Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s dictum in her majority opinion in the 2003 Grutter v. Bollinger case that in twenty-five years “the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.” (In an interview with Evan Thomas, for his 2019 biography of her, O’Connor distanced herself from that deadline.) Legally, affirmative action was always precarious, even as it became widely institutionalized. Its precarity made it easy for the current Court to tip it over.

It’s striking, in looking back at the long period between Reconstruction and the civil-rights movement, how avoidant the country’s leadership—including most liberals—was of racial issues. Even Franklin Roosevelt rarely applied his great rhetorical gifts to that subject. It matters a lot who’s in the room when agendas are set and policies are made. One of the purposes of affirmative action, and one of its successes, has been to correct the composition of such rooms; this is why the racial makeup of the student body at a few, yet highly important, colleges can have a broad effect on millions of people. Roberts may have had a similar rationale in mind when, in a mysterious footnote to his majority opinion, he granted military academies, which produce leaders for a disproportionately Black force that is meant to exemplify American values to the world, an exemption from the Court’s ban on affirmative action in admissions.

Opponents of affirmative action have been filing lawsuits for a very long time. For them, this decision will represent anything but a satisfying end to the struggle. Instead, they will see it as an invitation from the Supreme Court—one to be accepted quickly, before the Court’s membership changes—to look for other places where the majority’s way of defining color blindness does not prevail. Harvard and U.N.C. expect to remain under intense scrutiny from conservatives, just as they were expecting this decision. But admissions offices at selective colleges are not the most likely next defendants; it’s any institution or program that uses race as a plus factor in making decisions about who gets contracts, jobs, scholarships, and awards, or whatever other benefits it can hand out. Any racial-justice initiative launched in the fast-fading moment of moral passion after the murder of George Floyd will make for an especially inviting target for conservative legal crusaders, as such initiatives have also been for Republican politicians. It’s time for the supporters of affirmative action to prepare for a long, tough struggle that has to be understood as being about much more than who gets into college. ♦

— Nicholas Lemann is a staff writer at The New Yorker and a Professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

#Affirmative Action | Supreme Court | Higher Education | Civil Rights#The New Yorker#Nicholas Lemann

0 notes

Video

youtube

TrueMendous - Emmett Till Feat. Masta Ace

High Focus Records presents TrueMendous' new single ‘Emmett Till’ featuring Masta Ace and produced by Dirty Dike, lifted from her recent album 'Misdiagnosis Of Chyvonne Johnson' .

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941 – August 28, 1955) was an African American boy who was abducted, tortured, and lynched in Mississippi in 1955 at the age of 14, after being accused of offending a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, in her family's grocery store. The brutality of his murder and the acquittal of his killers drew attention to the long history of violent persecution of African Americans in the United States. Till posthumously became an icon of the civil rights movement.

Till was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. During summer vacation in August 1955, he was visiting relatives near Money, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region. He spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the white, married proprietor of a small grocery store there. Although what happened at the store is a matter of dispute, Till was accused of flirting with, touching, or whistling at Bryant. Till's interaction with Bryant, perhaps unwittingly, violated the unwritten code of behavior for a black male interacting with a white female in the Jim Crow-era South. Several nights after the incident in the store, Bryant's husband Roy and his half-brother J. W. Milam, who were armed, went to Till's great-uncle's house and abducted Emmett. They took him away then beat and mutilated him before shooting him in the head and sinking his body in the Tallahatchie River. Three days later, the boy's mutilated and bloated body was discovered and retrieved from the river.

Till's body was returned to Chicago, where his mother insisted on a public funeral service with an open casket, which was held at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ. It was later said that "The open-coffin funeral held by Mamie Till Bradley[a] exposed the world to more than her son Emmett Till's bloated, mutilated body. Her decision focused attention on not only American racism and the barbarism of lynching but also the limitations and vulnerabilities of American democracy". Tens of thousands attended his funeral or viewed his open casket, and images of his mutilated body were published in black-oriented magazines and newspapers, rallying popular black support and white sympathy across the U.S. Intense scrutiny was brought to bear on the lack of black civil rights in Mississippi, with newspapers around the U.S. critical of the state. Although local newspapers and law enforcement officials initially decried the violence against Till and called for justice, they responded to national criticism by defending Mississippians, temporarily giving support to the killers.

In September 1955, an all-white jury found Bryant and Milam not guilty of Till's murder. Protected against double jeopardy, the two men publicly admitted in a 1956 interview with Look magazine that they had tortured and murdered the boy, selling the story of how they did it for $4,000 (equivalent to $43,000 in 2022).Till's murder was seen as a catalyst for the next phase of the civil rights movement. In December 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott began in Alabama and lasted more than a year, resulting eventually in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that segregated buses were unconstitutional. According to historians, events surrounding Till's life and death continue to resonate.

An Emmett Till Memorial Commission was established in the early 21st century. The Sumner County Courthouse was restored and includes the Emmett Till Interpretive Center. Fifty-one sites in the Mississippi Delta are memorialized as associated with Till. The Emmett Till Antilynching Act, an American law which makes lynching a federal hate crime, was signed into law on March 29, 2022, by President Joe Biden.

0 notes

Text

August 28, 2021 (Saturday)

Today, Americans across the country marched for voting rights.

They recognize that our right to have a say in our government is slipping out of our hands. At a rally in Washington, Martin Luther King III told the crowd, “Our country is backsliding to the unconscionable days of Jim Crow. And some of our senators are saying, ‘Well, we can’t overcome the filibuster,’.... I say to you today: Get rid of the filibuster. That is a monument to white supremacy we must tear down.”

Since 1986, Republicans have worked to limit access to the polls, recognizing that when more people vote, they lose. Those restrictions took off after 2013 when, in the Shelby County v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court gutted the provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that required the Department of Justice to sign off on changes to voting in states with histories of racial discrimination.

That decision opened the way to voter restrictions, but voting laws have come especially fast and furious this year. Republicans have refused to accept that the election of Democrat Joe Biden was legitimate and, in Republican-dominated states, have worked to make sure Democrats do not have the power to elect another president in the future. Between January 1 and July 14 of this year, at least 18 states have enacted 30 laws restricting access to the vote.

Their plan is clearly to make sure those states stay Republican, no matter what the voters actually want.

This lack of competition destroys Democrats’ chances of winning elections, but it also pushes the Republican Party further and further to the right. With states sewn up for a Republican victory, potential Republican presidential candidates have to worry less about winning a general election than about winning the primaries.

Because primary voters are always the most energized and partisan voters, and because for the Republicans that currently means staunch Trump supporters, those vying to be Republican front runners are the Trump extremists: Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, for example, and even Florida’s Matt Gaetz and Georgia’s Marjorie Taylor Greene, who recently have been touring the early voting states of Iowa and New Hampshire attacking mask requirements and vaccine mandates, critical race theory and the infrastructure bills currently under discussion in Congress.

Vote-rigging in Republican-dominated states leads logically to a Republican extremist winning the White House in 2024.

Congress has before it two voting rights bills that would help to restore a level playing field between the two parties. One, the For the People Act, protects the right to vote, ends partisan gerrymandering, limits corporate money in elections, and requires new ethics rules for elected officials. The House passed the For the People Act in March.

On Tuesday, August 24, the House passed the second of the two voting rights bills, the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021, also known as H.R. 4, which expands the system of preclearance that had been in the 1965 Voting Rights Act before 2013. Under the John Lewis bill, the Department of Justice has to sign off on voting changes not simply in states with a longstanding history of discrimination, but also in states anywhere in the country that have shown a pattern of violations of voting rights.

Both of these measures are stalled in the Senate, where Republicans, who insist that states, not the federal government, must have the final say in who gets to vote, have vowed to filibuster them. Unless the Democrats can agree to carve out an exception to the filibuster for voting rights, the measures will die.

And today, Americans across the country marched for voting rights.

Today is the 58th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It was on this day in 1963 that the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Dr. King anchored the speeches for the day, though: before him spoke the chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a young John Lewis. Just 23 years old, he had been one of the thirteen original Freedom Riders, white and black students traveling together from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans to challenge segregation. “It was very violent. I thought I was going to die. I was left lying at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery unconscious,” Lewis later recalled.

Two years later, as Lewis and 600 marchers hoping to register African American voters in Alabama stopped to pray at the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, mounted police troopers charged the marchers, beating them with clubs and bullwhips. They fractured Lewis’s skull.

The attack in Selma created momentum for voting rights. Just after the attack, President Lyndon Baines Johnson called for Congress to pass a national voting rights bill. It did. On August 6, 1965, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act authorizing federal supervision of voter registration in districts where African Americans were historically underrepresented.

Today is also the anniversary of the longest filibuster ever conducted by a single senator. On this date in 1957, South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond began his filibuster to kill the Civil Rights Act of 1957, speaking for 24 hours and 18 minutes. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was designed to protect the right of African Americans to vote, using the federal government to overrule the state laws that limited voter registration and kept Black voters from the polls.

On a day that harks back to both John Lewis’s fight for voting rights and Strom Thurmond’s fight against them, I wonder which man’s principles will shape our future.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four Civil Rights Activist Posthumously Vacated of 1947 Convictions

By Kyra Goins, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, Class of 2023

June 21, 2022

On Friday, June 17th, four North Carolina “freedom riders,” Bayard Rustin, Andrew Johnson, Igal Roodenko, and Joseph Felmet, had their convictions from 1947 posthumously vacated [3]. “Freedom riders” is a term referring to individuals in the Jim Crow era who challenged the segregation laws of the time [2]. More specifically, the freedom riders got their name from participating in so-called “freedom rides” to protest mandated segregation on buses [2].

Their story begins in the spring of 1947. On April 13, eight black men and eight white men boarded a bus in Orange County, North Carolina heading from Chapel Hill, NC, to Greensboro, NC [3]. All the men, black and white, made a point to take their seats in the front of the bus [3]. This bus ride was only one segment of a longer journey that these men had embarked upon; this group of freedom riders began a two-week trip by boarding buses in Washington, D.C. and planned to make several stops in North Carolina [3]. The trip was known as the “Journey of Reconciliation” [3]. This journey came in response to the 1946 Supreme Court ruling in Morgan v. Virginia [2]. The case was to decide on “the constitutionality of an act of Virginia, which [required] all passenger motor vehicle carriers, both interstate and intrastate, to separate without discrimination the white and colored passengers” [1].

Excerpt from Supreme Court decision of Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia; 1946 [1]

The court decided that racial segregation on modes of interstate travel unconstitutional on the grounds that such segregation impedes interstate commerce [1]. The court writes that although “there is no federal act dealing with the separation of races in interstate transportation” and “no state law can reach beyond its own border nor bar transportation of passengers across its boundaries [resulting in] diverse seating requirements…it seems clear to us that seating arrangements for different races in interstate motor travel require a single, unfirm rule to promote and protect national travel” [1]. The court ruling was a win for civil rights, but the men embarking upon the Journey of Reconciliation wanted to test how well this ruling would realistically be upheld.

Prior to their arrival in Chapel Hill, NC, the men had been arrested at two other stops in North Carolina: Asheville and Mount Airy [3]. However, in both these instances the charges against the men were thrown out, considering racial integration on interstate transportation was perfectly legal according to the prior year’s Supreme Court ruling [3]. However, the men ran into trouble when boarding their bus in Chapel Hill. When the group went to sit in the front of the bus, “some were forced off by the bus driver, but four refused and were met with angry cab drivers” before they were arrested by the police [3]. Two black men, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were arrested on the grounds of refusing to move to different seats, and two white men, Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet, were charged with “interfering” [3]. The following month, the four men were convicted by Orange County judges and “sentenced to 30 days on a prison chain gang” [3].

Now, 75 years later, the justice system in Orange County has sought to correct the injustice against these four men, even in a small way [2]. The Orange County Board of Commissioners launched the special session of the Orange County Superior Court that vacated the freedom riders’ conviction following research the court had done following an anniversary of the 1947 trial [2]. Judge Allen Baddour, who oversaw the special session spoke to a room full of people in the same courtroom the men were originally sentenced: “‘We failed these men. We failed their cause and we failed to deliver justice in our community. And for that, I apologize. So we’re doing this today to right a wrong, in public, and on the record’” [2].

______________________________________________________________

[1] Cornell Law School. (n.d.). Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/328/373

[2] Foreman, T. (2022, June 18). Court posthumously vacates Freedom Riders' 1947 convictions in North Carolina. PBS. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/court-posthumously-vacates-freedom-riders-1947-convictions-in-north-carolina

[3] Johnson, K. (2022, June 18). Orange County apologizes to 1st freedom riders who challenged Jim Crow south. MSN. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/orange-county-apologizes-to-1st-freedom-riders-who-challenged-jim-crow-south/ar-AAYCd4V

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Georgian Jimmy Carter won the 1976 presidential race, no politician from the Deep South had been elected since 1844. Despite Carter’s Dixie roots, the incoming president boasted a large Black fan base, having supported Black causes as a lawmaker in his home state. Four out of every five Black voters reportedly backed Carter and, decades later, when the country welcomed its first Black president, Carter continued to speak out about race relations in America. His record on civil rights before and after entering the White House reveal why Carter long garnered support from communities of color.

A Voting Rights Supporter

During his tenure as a Georgia state senator from 1963 to 1967, Carter worked to overturn laws that made it challenging for Black people to vote, according to the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. His pro-integration stance did not prevent him from serving two terms as state senator, but his views may have hurt his gubernatorial bid. When he ran for governor in 1966, an outpouring of segregationists turned out to the polls to elect Jim Crow supporter Lester Maddox. When Carter ran for governor four years later, he “minimized appearances before African American groups, and even sought the endorsements of avowed segregationists, a move that some critics call deeply hypocritical.” But Carter, it turned out, was simply being a politician.

When he became governor the following year, he announced that the time had come to end segregation. Clearly, he’d never supported Jim Crow but catered to segregationists just to win their votes.

Appointments of Black People in Key Positions

As Georgia governor, Carter didn’t just verbally oppose segregation but also worked to create more diversity in state politics. He reportedly raised the number of Black people on Georgia state boards and agencies from just three to a staggering 53. Under his leadership, almost half, 40 percent, of public servants in influential positions were Black.

Social Justice Platform Impresses Time, Rolling Stone

Gov. Carter’s views on civil rights so markedly differed from other Southern lawmakers, such as notorious Alabama Gov. George Wallace, that in 1971 he made the cover of Time magazine, which dubbed the Georgian the face of the “New South.” Just three years later, legendary Rolling Stone journalist, Hunter S. Thompson, became a fan of Carter after hearing the lawmaker discuss how politics can be used to effect social change.

A Racial Gaffe or More Duplicity?

Carter sparked controversy on April 3, 1976, while discussing public housing. The then-presidential candidate said that he thought community members should be able to preserve the “ethnic purity” of their neighborhoods, a statement that sounded like the tacit support of segregated housing. Five days later, Carter apologized for the comment. Had the pro-integrationist really meant to express support of Jim Crow housing, or was the statement just another ploy to get the segregationist vote?

Black College Initiative

As president, Carter launched the Black College Initiative to give historically Black colleges and universities more support from the federal government.

“Other administration education initiatives covered in the collection include science apprenticeships for minority students, technical assistance to Black colleges, and minority fellowships in graduate management education,” according to the “Civil Rights During the Carter Administration” report.

Business Opportunities for Black People

Carter also tried to close the wealth gap between whites and Black people. He developed initiatives to give Black-owned businesses a boost. “These programs focused primarily on increasing the government’s procurement of goods and services from minority business, as well as through requirements for procurement by federal contractors from minority firms,” the CRDTCA report states. “The aided industries ranged from construction to manufacturing to advertising, banking, and insurance. The government also maintained a program to help minority-owned exporters gain footholds in foreign markets.”

Affirmative Action Supporter

Affirmative action became a heavily debated topic when the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case of Allan Bakke, a white man denied admission to the medical school at the University of California, Davis. Bakke sued after UC Davis rejected him while admitting less qualified Black students, he argued. The case marked the first time affirmative action had been challenged so vigorously. Yet, Carter continued to support affirmative action, which endeared him to Black people.

Prominent Black people in the Carter Administration

When Carter became president, more than 4,300 Black people held elected office in the U.S. They also served in the Carter cabinet. “Wade H. Mc-Cree served as solicitor general, Clifford L. Alexander was the first Black secretary of the army, Mary Berry was the top official in Washington on educational matters prior to the establishment of the Department of Education, Eleanor Holmes Norton chaired the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and Franklin Delano Raines served on the White House staff,” according to the Spartacus-Educational website. Andrew Young, a Martin Luther King protégé and the first African American elected as a Georgia congressman since Reconstruction, served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. But Young’s outspoken views on race caused controversy for Carter and Young resigned under pressure. The president replaced with him another Black man, Donald F. McHenry.

Expansion from Civil Rights to Human Rights

When Carter lost his bid for re-election, he opened the Carter Center in Georgia in 1981. The institution promotes human rights across the world and has overseen elections in a number of countries and curbed human rights violations in places such as Ethiopia, Panama, and Haiti. The center has also focused on domestic issues, such as in October 1991, when it launched the Atlanta Project initiative to address urban social problems. In October 2002, President Carter won the Nobel Peace Prize for “his decades of untiring efforts to find peaceful solutions to international conflict.”

The Civil Rights Summit

Jimmy Carter was the first president to speak at the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library Civil Rights Summit in April 2014. The summit commemorated the 50th anniversary of the groundbreaking Civil Rights Act of 1964. During the event, the former president urged the nation to do more civil rights work. “There’s still a gross disparity between Black and white people on education and employment,” he said. “A good amount of schools in the South are still segregated.” Given these factors, the civil rights movement isn’t just history, Carter explained but remains a pressing issue in the 21st century.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My newest letter to Romney:

Senator Romney,

Though I am not a constituent of Utah, I felt it was my duty as a concerned American citizen to express to you the depths of my disappointment upon hearing this morning that you are in favor of a vote for a new Supreme Court nominee prior to the completion of the 2020 election.

Your previous actions standing in opposition of the current administration gave many hope, Senator, that despite party lines there were those of you in the Senate who hold fast to the traditions of honor and integrity. With this single statement you have quickly and efficiently taken away that hope. I am asking that you reconsider that position now.

I would like to remind you of the position of your own party during the 2016, with more than ten months left before that year's election.

At that time, the following was said, and remains public record. We will begin with Mitch McConnell, Senate Majority Leader.

""The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president." - February 13, 2016.

"Given that we are in the midst of the presidential election process, we believe that the American people should seize the opportunity to weigh in on whom they trust to nominate the next person for a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court." - February 16, 2016.

"[W]hile finding the right person to take the seat [Scalia] occupied will clearly be a monumental task, it's one we think the American people are more than equipped to tackle. Some disagree and would rather the Senate simply push through yet another lifetime appointment from a president who's on his way out the door...I believe that it is today the American people who are best-positioned to help make this important decision." - February 22, 2016.

McConnell was not the only Republican to take this stance.

Sen. Cory Gardner (R-Col.): “I think we’re too close to the election. The president who is elected in November should be the one who makes this decision.”

Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas): “I believe the American people deserve to have a voice in the selection of the next Supreme Court Justice, and the best way to ensure that happens is to have the Senate consider a nomination made by the next President. Confirming a new Supreme Court Justice during a presidential election year for a vacancy arising that same year is not common in our nation’s history; the last time it happened was in 1932. And it has been almost 130 years since a presidential election year nominee was confirmed for a vacancy arising the same year under divided government as we have today."

Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas): “It has been 80 years since a Supreme Court vacancy was nominated and confirmed in an election year. There is a long tradition that you don’t do this in an election year.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.): “If an opening comes in the last year of President Trump’s term, and the primary process has started, we’ll wait to the next election”

Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.): “I don’t think we should be moving on a nominee in the last year of this president’s term — I would say that if it was a Republican president .”

Sen. Jim Inhofe (R-Okla.): “It makes the current presidential election all that more important as not only are the next four years in play, but an entire generation of Americans will be impacted by the balance of the court and its rulings. Sens. Barack Obama, Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton, Chuck Schumer and Harry Reid have all made statements that the Senate does not have to confirm presidential nominations in an election year. I will oppose this nomination as I firmly believe we must let the people decide the Supreme Court’s future.”

Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa): “A lifetime appointment that could dramatically impact individual freedoms and change the direction of the court for at least a generation is too important to get bogged down in politics. The American people shouldn’t be denied a voice.”

Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa): “We will see what the people say this fall and our next president, regardless of party, will be making that nomination.”

Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.): “Vice President Biden’s remarks may have been voiced in 1992, but they are entirely applicable to 2016. The campaign is already under way. It is essential to the institution of the Senate and to the very health of our republic to not launch our nation into a partisan, divisive confirmation battle during the very same time the American people are casting their ballots to elect our next president.”

Sen. David Perdue (R-Ga.): “The very balance of our nation’s highest court is in serious jeopardy. As a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, I will do everything in my power to encourage the president and Senate leadership not to start this process until we hear from the American people.”

Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.): “The next President must nominate successor that upholds constitution, founding principles.”

Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.): “I strongly agree that the American people should decide the future direction of the Supreme Court by their votes for president and the majority party in the U.S. Senate.”

Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Penn.): “The next Court appointment should be made by the newly-elected president.”

Sen. Richard Burr (R-N.C.): “In this election year, the American people will have an opportunity to have their say in the future direction of our country. For this reason, I believe the vacancy left open by Justice Antonin Scalia should not be filled until there is a new president.”

Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.): “The Senate should not confirm a new Supreme Court justice until we have a new president.”

Sen. John Hoeven (R-N.D.): “There is 80 years of precedent for not nominating and confirming a new justice of the Supreme Court in the final year of a president’s term so that people can have a say in this very important decision.”

Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio): “I believe the best thing for the country is to trust the American people to weigh in on who should make a lifetime appointment that could reshape the Supreme Court for generations. This wouldn’t be unusual. It is common practice for the Senate to stop acting on lifetime appointments during the last year of a presidential term, and it’s been nearly 80 years since any president was permitted to immediately fill a vacancy that arose in a presidential election year.”

Yet with less than 45 days until this year's election, the Republican Party seems determined to forget their own words and to force through a vote before November 3rd. Doing so is both hypocritical and irresponsible. Rather than taking the time and consideration that this matter deserves and allowing time to mourn the loss of the Honorable Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (may her memory be a blessing), the Senate has declared their intent to rush a nomination and a vote and have sent the American public into turmoil.

I am asking, Senator, that you uphold the precedent set forth by the Republican Party in 2016 by refusing to vote on a new nominee until the completion of the 2020 election and the subsequent inauguration. Give this matter the time and the energy it deserves rather than acting purely on party loyalty.

The world is watching.

Thank you for your time.

#write to your senators#even if it feels hopeless#remind them that we are still paying attention#call them out#and thank the ones who have decided to do the right thing#politics#not trek

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Burger Commission Report

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Reagan, informally known as the Burger Commission, was established by President George Bush through Executive Order 12304 on April 8, 1981 to investigate the assassination of United States President Ronald Reagan that had taken place on March 30, 1981. The U.S. Congress passed Senate Joint Resolution 59 authorizing the Presidential appointed Commission to report on the assassination of President Ronald Reagan, mandating the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of evidence. Its 776-page final report was presented to President Bush on June 30, 1982, and made public four days later. It concluded that President Reagan was assassinated by John Hinckley Jr., and that Hinckley acted entirely alone. The Commission took its unofficial name—the Burger Commission—from its chairman, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger.

Committee

Warren E. Burger, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (chairman)

Barry Goldwater (R-Arizona), U.S. Senator

Robert Byrd (D-West Virginia), U.S. Senator

Tom Foley (D-Washington), U.S. Representative, House Majority Whip

Robert H. Michel (R-Illinois), U.S. Representative, House Minority Leader

William J. Casey, Director of Central Intelligence and head of the Central Intelligence Agency

Floyd I. Clarke, Deputy Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Joan Quigley, astrologer (not officially part of the commission, but former First Lady Nancy Reagan insisted that she be included in committee meetings so as to "leave no stone unturned.")

At one point, Nancy Reagan insisted that the Commission hold a seance to summon the spirit of President Reagan himself so he could help solve his own murder. President Bush respectfully declined the suggestion, though Senator Goldwater, a close personal friend of the Reagans, humored the former First Lady by spending a week in November of 1981 investigating the "Curse of Tippecanoe," the supposed pattern of deaths in office of presidents of the United States who won the elections in years that are evenly divisible by 20

William Henry Harrison (1840)

Abraham Lincoln (1860, 1864)

James A. Garfield (1880)

William McKinley (1896, 1900)

Warren G. Harding (1920)

Franklin D. Roosevelt (1932, 1936, 1940, 1944)

John F. Kennedy (1960)

Ronald Reagan (1980)

The Committee found no evidence of conspiracy linking Reagan's death to any previous president's, chocking it up to a coincidence as it failed to account for the death of President Zachary Taylor (1848), and the survival of Presidents Thomas Jefferson (1800, 1804) and James Monroe (1816, 1820).

State Funeral of Ronald Reagan

Date: April 3 - 7, 1981

Mourning Period: March 30 - April 30, 1981

Location: Capitol Rotunda, U.S. Capitol, Washington, DC

Participants: Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, George Bush, members of the 97th Congress, the 52 former Iran hostages

George Bush would probably nominate a moderate Republican to be his Vice President under the 25th Amendment sometime in May or June; while Republicans controlled the Senate, Democrats held a considerable majority in the House of Representatives, preventing Bush from appointing a hardline conservative.

George W. Romney, Governor of Michigan (1963 - 1969), HUD Secretary under Nixon (1969 - 1973)

Jim Jeffords, Attorney General of Vermont (1969 - 1973), U.S. Representative from Vermont's at-large District (1975 - present)

John Chafee, Governor of Rhode Island (1963 - 1969), U.S. Senator from Rhode Island (1976 - present)

William Scranton, Governor of Pennsylvania (1963 - 1967), United States Ambassador to the United Nations (1976 - 1977)

Bush had more experience in foreign policy then domestic, so I think Scranton would be a probable choice for VP. Governor of a swing state and an ambassador under Gerald Ford. This combined ticket of Bush/Scranton would be seen as far too liberal by Republicans in 1984, so he would likely choose a more conservative running mate for his second term.

Perhaps Barry Goldwater, Senator from Arizona, father of modern conservatism, mentor to late President Reagan, and Republican nominee for president in 1964 (he lost to Johnson in a 60-40 landslide due to his opposition to the Civil Rights Act). If not Goldwater, perhaps his son Barry Jr, a Representative from California.

Bob Dole, Senator from Kansas, and President Gerald Ford's running mate in 1976

Caspar Weinberger, Reagan and Bush's Secretary of Defense

William French Smith, Regan and Bush's Attorney General

Alexander Haig, Reagan and Bush's Secretary of State (though he would be a controversial choice, having erroneously claimed to be acting-president in the time between Reagan death and Bush's return to Washington, DC from Texas)

In June 1982 of our timeline, Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity, in part because the assassination failed. Attempting to assassinate a president is different than actually assassinating them, so Hinckley would very likely be found guilty and sentenced to death, becoming the first federal inmate to be executed since Victor Fregur in 1963.

#alternate history#ah#au#alternate universe#ronald reagan#john hinckley jr#reagan#hinckley#george bush#george hw bush#bush#1981#assassination#presidential assassination#assassin#politics#political#history#us history#american history#1980s#warren e burger#warren burger#burger

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 1.22

Beer Birthdays

Pat Hagerman (1964)

James Renfrew (1965)

Motor (1966)

Bud Bundy, character on Married… with Children, named after Al Bundy's favorite beer (1975)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Francis Bacon; writer, philosopher (1561)

Sergei Eisenstein; Russian director & screenwriter (1898)

Robert E. Howard; fantasy writer (1906)

J.J. Johnson; jazz trombonist, bandleader (1924)

Diane Lane; actress (1965)

Famous Birthdays

Andre Marie Ampere; physicist (1775)

George Balanchine; choreographer (1904)

Bill Bixby; actor (1934)

Richard Blackmore; English physician & poet (1654)

Linda Blair; actress (1959)

Ed Bradley; television journalist (1941)

Ernst Busch; German actor and singer (1900)

Lord Byron; poet (1788)

Seymour Cassel; actor (1935)

Sam Cooke; musician (1931)

Douglas "Wrong Way" Corrigan; pilot (1907)

Olivia d'Abo; actor (1967)

John Donne; English poet & cleric (1573)

Joe Esposito; author (1938)

Guy Fieri; chef, author, and tv host (1968)

Willa Ford; singer-songwriter & actress (1981)

Pierre Gassendi; French mathematician, astronomer & philosopher (1592)

D.W. Griffith; film director (1875)

Martti Haavio; Finnish poet and mythologist (1899)

Alan J. Heeger; physicist and chemist (1936)

Helen Hoyt; poet and author (1887)

John Hurt; actor (1940)

Michael Hutchence; rock singer (1960)

Jim Jarmusch; film director (1953)

DJ Jazzy Jeff; musician (1965)

Graham Kerr; chef, "Galloping Gourmet" (1934)

William Kidd; Scottish sailor and pirate hunter (1645)

Nicolas Lancret; French painter (1690)

Piper Laurie; actor (1932)

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, German philosopher & author (1729)

Malcolm McLaren, English singer-songwriter & manager

Charles Morgan; writer (1894)

Steve Perry; rock musician (1949)

Francis Picabia; French painter and poet (1878)

Walter Raleigh; English poet, soldier, & explorer (1552)

Ray Rice; Baltimore Ravens RB (1987)

George "Chuck" Seifert; San Francisco 49ers coach (1940)

John Wesley Shipp; actor (1956)

Ann Sothern; actress (1909)

August Strindberg; Swedish novelist, poet, & playwright (1849)

Hikaru Walter Sulu; Star Trek character (2179)

Conrad Veidt; German-American actor, director (1893)

Frederick Vinson; supreme court chief justice (1890)

Joseph Wambaugh; writer (1937)

John Winthrop; politician (1588)

0 notes

Text

letters from an american

Letters From an American

Heather Cox Richardson

August 28, 2021

Heather Cox Richardson

Today, Americans across the country marched for voting rights.

They recognize that our right to have a say in our government is slipping out of our hands. At a rally in Washington, Martin Luther King III told the crowd, “Our country is backsliding to the unconscionable days of Jim Crow. And some of our senators are saying, ‘Well, we can’t overcome the filibuster,’.... I say to you today: Get rid of the filibuster. That is a monument to white supremacy we must tear down.”

Since 1986, Republicans have worked to limit access to the polls, recognizing that when more people vote, they lose. Those restrictions took off after 2013 when, in the Shelby County v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court gutted the provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that required the Department of Justice to sign off on changes to voting in states with histories of racial discrimination.

That decision opened the way to voter restrictions, but voting laws have come especially fast and furious this year. Republicans have refused to accept that the election of Democrat Joe Biden was legitimate and, in Republican-dominated states, have worked to make sure Democrats do not have the power to elect another president in the future. Between January 1 and July 14 of this year, at least 18 states have enacted 30 laws restricting access to the vote.

Their plan is clearly to make sure those states stay Republican, no matter what the voters actually want.

This lack of competition destroys Democrats’ chances of winning elections, but it also pushes the Republican Party further and further to the right. With states sewn up for a Republican victory, potential Republican presidential candidates have to worry less about winning a general election than about winning the primaries.

Because primary voters are always the most energized and partisan voters, and because for the Republicans that currently means staunch Trump supporters, those vying to be Republican front runners are the Trump extremists: Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, for example, and even Florida’s Matt Gaetz and Georgia’s Marjorie Taylor Greene, who recently have been touring the early voting states of Iowa and New Hampshire attacking mask requirements and vaccine mandates, critical race theory and the infrastructure bills currently under discussion in Congress.

Vote-rigging in Republican-dominated states leads logically to a Republican extremist winning the White House in 2024.

Congress has before it two voting rights bills that would help to restore a level playing field between the two parties. One, the For the People Act, protects the right to vote, ends partisan gerrymandering, limits corporate money in elections, and requires new ethics rules for elected officials. The House passed the For the People Act in March.

On Tuesday, August 24, the House passed the second of the two voting rights bills, the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021, also known as H.R. 4, which expands the system of preclearance that had been in the 1965 Voting Rights Act before 2013. Under the John Lewis bill, the Department of Justice has to sign off on voting changes not simply in states with a longstanding history of discrimination, but also in states anywhere in the country that have shown a pattern of violations of voting rights.

Both of these measures are stalled in the Senate, where Republicans, who insist that states, not the federal government, must have the final say in who gets to vote, have vowed to filibuster them. Unless the Democrats can agree to carve out an exception to the filibuster for voting rights, the measures will die.

And today, Americans across the country marched for voting rights.

Today is the 58th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It was on this day in 1963 that the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Dr. King anchored the speeches for the day, though: before him spoke the chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a young John Lewis. Just 23 years old, he had been one of the thirteen original Freedom Riders, white and black students traveling together from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans to challenge segregation. “It was very violent. I thought I was going to die. I was left lying at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery unconscious,” Lewis later recalled.

Two years later, as Lewis and 600 marchers hoping to register African American voters in Alabama stopped to pray at the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, mounted police troopers charged the marchers, beating them with clubs and bullwhips. They fractured Lewis’s skull.

The attack in Selma created momentum for voting rights. Just after the attack, President Lyndon Baines Johnson called for Congress to pass a national voting rights bill. It did. On August 6, 1965, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act authorizing federal supervision of voter registration in districts where African Americans were historically underrepresented.