#stem cell research center

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why GMP Compliance Is Paramount For High-Quality Mesenchymal Stem Cell?

The past twenty years have witnessed a fascinating unboxing of the mesenchymal stem cells. These microscopic marvels hold the potential to revolutionize how we approach disease. These mesenchymal stem cells are extracted from adult cells, and hence, they rarely receive any ethical backlash. Unlike most stem cells, mesenchymal ones boast remarkable versatility and can morph into diverse cell types, from bone to blood vessels. These cells carry several regenerative and anti-inflammatory prowess, which has propelled them to the forefront of stem cell therapy. The use in therapeutic applications has ignited a surge in demand that outpaces our current production capabilities.

Given the surge in demand for MSCs for research, providing researchers with high-quality stem cells for reproducible research is necessary. Enter the realm of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), our roadmap towards building factories for these cellular powerhouses, ensuring not just quantity but unparalleled quality and safety. Buckle up, science researchers, for we’re about to delve into the intricate dance of scaling up MSC production while upholding the highest standards, paving the way for a future where these microscopic maestros weave their magic on a grand scale.

#Mesenchymal Stem Cells#MSCs#GMP Compliance Is Paramount For High-Quality Mesenchymal Stem Cell#Challenges With Mesenchymal Stem Cells#Cell culture#customized primary cells#primary cells#biotech company#stem cells#exosomes#stem cell research center#regenerative medicine#bioengineering#Kosheeka

0 notes

Text

youtube

Stem Cell Treatment For Fibromyalgia | Orthopedic Disease Treatment | Pain | Regenerative | Cells |

https://www.globalstemcellcare.com/orthopedic/stem-cell-treatment-for-fibromyalgia/

#Fibromyalgia#Chronic Pain#Fibromyalgia Awareness#Pain Management#Chronic Fatigue#Stem Cell Therapy#Stem Cells for Fibromyalgia#Fibromyalgia Treatment#Fibro Healing#Stem Cell Research#Stem Cells#Fibromyalgia Care#Alternative Fibromyalgia Treatment#Innovative Fibro Treatment#Exosome#Exosome Therapy#Best Stem Cell Hospital in India#Best Stem Cell Center in Delhi#Orthopedic Disease Treatment#Pain Relief#Pain Management.#advanced stem cell treatment#Youtube

0 notes

Note

Do you see a future where we can give a trans person a shot and have their body start making the correct sex hormones (eg testes change to make E, or ovaries change to make T)? How far off? What things need to be accomplished to achieve it, and what tools do we already have?

Disclaimer that none of this is gonna be all that scientifically robust, the terms used are gonna be descriptive rather than technical, and that I'm just woke up and these are the ravings of a woman gone mad.

A single shot is ambitious, but I could see a course of several months or a couple years that, after those several months, lasts a lifetime.

How far off? I mean, wildly dependent on funding and focus. Unfortunately, nothing related to trans healthcare is gonna see a serious push I would think. With an actual, serious push, I would give it a few decades of research (if that)(this is blisteringly fast btw) until it's punted over to the FDA. At that point it's outside of my knowledge to know how far things would move forward.

But honestly, it's part politics, part luck of the draw on what people research and push forward. Might happen in our lifetime, but don't hold your breath. Research is grindingly slow.

This is mostly based around the possibility of inducing transdifferentiation. Tldr:

-stem cells are exciting bc they can become any cell type. They haven't "locked in" their cell fate yet.

-most research on cellular differentiation centers around deprogrammed differentiated cells, reverting them to stem cells, and then reprogramming them into something else. The deprogramming is actually well studied (shoutout Yamanaka factors) but I don't see something like this reaching a medicinal, in vivo use soon.

-in extremely rare and induced cases, however, you can force a fully differentiated cell type to become another fully differentiated cell type *without* that intermediate. This is likely way easier to pull off in vivo, even though the initial molecular triggers are much, much rarer and more difficult to study.

Which brings us to the two theoretical dots that we can use here: prostatic metioplasias as a result of testosterone (for transmascs) and the role of DMRT1 for transfemmes.

Broad tldr of each of these points:

-there was a study that studied vaginal lining of transmascs who had been on T for several years and gotten hysterectomies. They found some prostate tissue intercalating the vagina.

-removal of a particular gene (DMRT1) allowed testes to slowly become ovarian tissue and produce estrogens. This gene is responsible for maintaining testes cell fate- keeping the lock, locked.

Neither of these provides a direct basis for actual medication. They show avenues for what will work, however. What's necessary here is to understand the upstream signals that control the expression of genes like DMRT1, which can then be exploited to force expression or stop expression in vivo, in a human.

Basically, the way transdifferentiation would work here is blasting the appropriate cells with enough of these signals, over enough time to ensure that everything actually undergoes TD, to reprogram everything you want to reprogram.

(yes, I know about the crispr transfemme who targeted DMRT1. No, I don't think that's real. I've posted about that before.)

You don't have to bother reading these, but here's the primary sources I'm talking about for anyone interested:

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved on our archive

Some interesting science analyzed

BY BROOKS LEITNER

Imagine lying back in an enclosed chamber where you bask for 90 minutes in a sea of pure oxygen at pressures two to three times that felt at sea level. This is the world of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), a technology that’s been around for decades and is now being explored as a possible treatment for Long COVID.

"The silence on the inside is deafening at first,” says John M.,* who has undergone dozens of HBOT treatments for his persistent Long COVID symptoms. Fortunately, there is a television outside the chamber in view, and it is easy to communicate with the provider if needed. While the potential protocol is still being refined, patients may undergo up to 40 HBOT sessions to address some of the most problematic, lingering symptoms of this complex condition.

HBOT is a therapeutic process that has been widely used to treat such conditions as decompression sickness in scuba divers, carbon monoxide poisoning, and diabetic foot ulcers. In HBOT, the body is exposed to 100% oxygen, a significant increase from the 21% oxygen concentration we typically breathe. The therapy takes place in an enclosed chamber where the air pressure is elevated above normal levels. The combination of high-pressure and high-oxygen conditions enhances the amount of oxygen that can reach the body's tissues. The hope is that this therapy can provide the same relief and healing to people with Long COVID that it does for those with other conditions.

According to John M., HBOT was the first treatment that helped with his sleep and reduced his heart palpitations. “At one point after hospitalization, my Long COVID symptoms were so bad that I could barely walk or talk. HBOT was a great tool that really assisted with my recovery,” he said. John added that he hopes the medical community will achieve a better understanding of how HBOT can help relieve suffering for patients with Long COVID and that more research will increase access to this innovative therapy.

Does HBOT improve Long COVID symptoms? One key observation from the work of Inderjit Singh, MBChB, an assistant professor at Yale School of Medicine (YSM) specializing in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine, is that Long COVID patients often experience debilitating fatigue. Based on Dr. Singh’s previous Long COVID research, the exhaustion is thought to be linked to the muscles’ inability to efficiently extract and utilize oxygen.

To picture how HBOT might work, you can think of your muscles as engines sputtering, struggling to get the fuel they need. If oxygen is the gas that fuels the muscles, it’s as if you are trying to complete your daily routine while the gas tank is running on “empty.” By aiming to directly address this oxygen utilization impairment, HBOT may be a potential solution.

A systematic review by researchers at the China Medical University Hospital noted that HBOT could tackle another major factor in the Long COVID puzzle: oxidative stress. This relates to the body's struggle to maintain balance when harmful molecules, known as free radicals, run amok, causing chronic inflammation.

Research co-authored by Sandra K. Wainwright, MD, medical director of the Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Wound Healing at Greenwich Hospital in Connecticut, suggests that HBOT, with its high-oxygen environment, might dampen this chronic inflammation by improving mitochondrial activity and decreasing production of harmful molecules. Other potential benefits of HBOT in the treatment of Long COVID may include restoration of oxygen to oxygen-starved tissues, reduced production of inflammatory cytokines, and increased mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells—primary cells that transform into red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

HBOT for Long COVID: Current and ongoing research Several small-scale reports have indicated that HBOT is safe for patients with Long COVID.

To address this question, a trial that followed the gold standard of modern medical research—a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind design—assigned 73 Long COVID patients to either receive 40 sessions of HBOT or a placebo of only 21% oxygen. The study observed positive changes in attention, sleep quality, pain symptoms, and energy levels among participants receiving HBOT. In a longitudinal follow-up study published in Scientific Reports, the authors at the Tel Aviv University found that clinical improvements persisted even one year after the last HBOT session was concluded. In a second study, the same authors focused on heart function, measured by an echocardiogram, and found a significant reduction in heart strain, known as global longitudinal strain, in patients who received HBOT.

In another study, 10 patients with Long COVID underwent 10 HBOT treatments over 12 consecutive days. Testing showed statistically significant improvement in fatigue and cognitive function. Meanwhile, an ongoing trial at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden has reported interim safety results wherein almost half of the Long COVID patients in the trial reported cough or chest discomfort during treatment. However, it was unclear whether HBOT exacerbated this symptom or if this adverse effect was due to the effort of participation by patients suffering from more severe Long COVID symptoms.

Is HBOT currently available as a treatment for Long COVID? For HBOT to become a mainstream treatment option for Long COVID, several critical priorities must be addressed. First, there is currently no established method for tailoring HBOT dosages to individual patients, so researchers must learn more about the specific features or symptoms that indicate potential benefits from HBOT. At the same time, we need to identify factors that may be associated with any adverse outcomes of HBOT. And finally, it’s important to determine how long these potentially beneficial effects last in a larger cohort. Will just a few HBOT trials be enough to restore patients to their baseline health, or will HBOT become a recurring component of their annual treatment regimen?

For now, HBOT remains an experimental therapy—and as such is not covered by insurance. This is a huge issue for patients because the therapy is expensive. According to Dr. Wainwright, a six-week course of therapy can run around $60,000. That’s a lot to pay for a therapy that’s still being studied. In the current completed studies, different treatment frequencies and intensities have been used, but it’s unclear how the treatment conditions affect the patient’s outcome.

“I have had some patients notice improvements after only 10 or 15 treatments, whereas some others need up to 45 treatments before they notice a difference,” notes Dr. Wainwright. “I think that HBOT is offering some promising results in many patients, but it is probably a strong adjunctive treatment to the other spectrum of things Long COVID patients should be doing, like participating in an exercise, rehab, and nutritional program.”

Dr. Singh notes that “a major challenge for research is the heterogeneity of Long COVID. It is hard to determine which symptoms to treat and enroll patients into trials based on them.”

Perhaps treatments that target multiple issues caused by Long COVID, like HBOT, may help overcome this challenge.

*Not his real name.

Brooks Leitner is an MD/PhD candidate at Yale School of Medicine.

The last word from Lisa Sanders, MD: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) is just one of the many existing treatments that are being looked at to treat Long COVID. We see this with many new diseases—trying to use a treatment that is effective in one set of diseases to treat another. And there is reason for optimism: We know that HBOT can deliver high levels of oxygen to tissues in need of oxygen. That’s why it’s used to treat soft tissue wounds. If reduced oxygen uptake is the cause of the devastating fatigue caused by Long COVID, as is suggested by many studies, then perhaps a better delivery system will help at least some patients.

Studies referenced:

bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-023-08002-8

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8806311/

www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-53091-3

www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-15565-0

www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1354088/full

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11051078/#:~:text=Proposed%20Mechanism%20of%20HBOT%20o

#long covid#hbottherapy#HBOT#hyperbaric oxygen therapy#mask up#covid#pandemic#wear a mask#public health#covid 19#still coviding#wear a respirator#coronavirus#sars cov 2

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

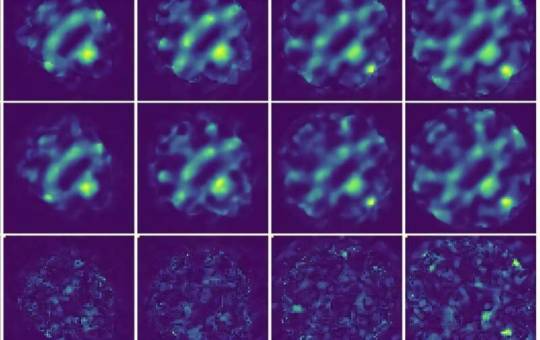

AI model improves 4D STEM imaging for delicate materials

Researchers at Monash University have developed an artificial intelligence (AI) model that significantly improves the accuracy of four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy (4D STEM) images. Called unsupervised deep denoising, this model could be a game-changer for studying materials that are easily damaged during imaging, like those used in batteries and solar cells. The research from Monash University's School of Physics and Astronomy, and the Monash Center of Electron Microscopy, presents a novel machine learning method for denoising large electron microscopy datasets. The study was published in npj Computational Materials. 4D STEM is a powerful tool that allows scientists to observe the atomic structure of materials in unprecedented detail.

Read more.

#Materials Science#Science#Materials Characterization#Computational materials science#Electron microscopy#Monash University

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Developing Zone

A method for creating human brain organoids – lab-grown mini brain models – with a compartment of cells called the outer subventricular zone closely matching the processes involved in development of the brain's neocortex in life

Read the published research article here

Video from work Ryan M. Walsh, Raffaele Luongo and Elisa Giacomelli, and colleagues

Center for Stem Cell Biology and Developmental Biology Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; Institute of Oncology Research (IOR), Bellinzona Institutes of Science (BIOS+), Bellinzona, Switzerland

Video originally published with a Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial – NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Published in Cell Reports, April 2024

You can also follow BPoD on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

japanese scientists have created a hydrogel that reverts cancer cells back to cancer stem cells in 24 hours

#technology#future#latest news#technology news#google#artificial intelligence#new techs#smart#tech#future of health care#health and wellness#healthcare#breast cancer#cancer#scientist#science#stem#treatment#development

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Low gravity in space travel found to weaken and disrupt normal rhythm in heart muscle cells

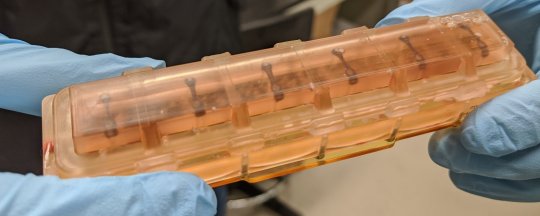

Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists who arranged for 48 human bioengineered heart tissue samples to spend 30 days at the International Space Station report evidence that the low gravity conditions in space weakened the tissues and disrupted their normal rhythmic beats when compared to Earth-bound samples from the same source.

The scientists said the heart tissues "really don't fare well in space," and over time, the tissues aboard the space station beat about half as strongly as tissues from the same source kept on Earth.

The findings, they say, expand scientists' knowledge of low gravity's potential effects on astronauts' survival and health during long space missions, and they may serve as models for studying heart muscle aging and therapeutics on Earth.

A report of the scientists' analysis of the tissues is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Previous studies showed that some astronauts return to Earth from outer space with age-related conditions, including reduced heart muscle function and arrythmias (irregular heartbeats), and that some—but not all—effects dissipate over time after their return.

But scientists have sought ways to study such effects at a cellular and molecular level in a bid to find ways to keep astronauts safe during long spaceflights, says Deok-Ho Kim, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering and medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Kim led the project to send heart tissue to the space station.

To create the cardiac payload, scientist Jonathan Tsui, Ph.D. coaxed human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to develop into heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes). Tsui, who was a Ph.D. student in Kim's lab at the University of Washington, accompanied Kim as a postdoctoral fellow when Kim moved to Johns Hopkins University in 2019. They continued the space biology research at Johns Hopkins.

Tsui then placed the tissues in a bioengineered, miniaturized tissue chip that strings the tissues between two posts to collect data about how the tissues beat (contract). The cells' 3D housing was designed to mimic the environment of an adult human heart in a chamber half the size of a cell phone.

To get the tissues aboard the SpaceX CRS-20 mission, which launched in March 2020 bound for the space station, Tsui says he had to hand-carry the tissue chambers on a plane to Florida, and continue caring for the tissues for a month at the Kennedy Space Center. Tsui is now a scientist at Tenaya Therapeutics, a company focused on heart disease prevention and treatment.

Once the tissues were on the space station, the scientists received real-time data for 10 seconds every 30 minutes about the cells' strength of contraction, known as twitch forces, and on any irregular beating patterns. Astronaut Jessica Meir, Ph.D., M.S. changed the liquid nutrients surrounding the tissues once each week and preserved tissues at specific intervals for later gene readout and imaging analyses.

The research team kept a set of cardiac tissues developed the same way on Earth, housed in the same type of chamber, for comparison with the tissues in space.

When the tissue chambers returned to Earth, Tsui continued to maintain and collect data from the tissues.

"An incredible amount of cutting-edge technology in the areas of stem cell and tissue engineering, biosensors and bioelectronics, and microfabrication went into ensuring the viability of these tissues in space," says Kim, whose team developed the tissue chip for this project and subsequent ones.

Devin Mair, Ph.D., a former Ph.D. student in Kim's lab and now a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins, then analyzed the tissues' ability to contract.

In addition to losing strength, the heart muscle tissues in space developed irregular beating (arrhythmias)—disruptions that can cause a human heart to fail. Normally, the time between one beat of cardiac tissue and the next is about a second. This measure, in the tissues aboard the space station, grew to be nearly five times longer than those on Earth, although the time between beats returned nearly to normal when the tissues returned to Earth.

The scientists also found, in the tissues that went to space, that sarcomeres—the protein bundles in muscle cells that help them contract—became shorter and more disordered, a hallmark of human heart disease.

In addition, energy-producing mitochondria in the space-bound cells grew larger, rounder and lost the characteristic folds that help the cells use and produce energy.

Finally, Mair, Eun Hyun Ahn, Ph.D.—an assistant research professor of biomedical engineering—and Zhipeng Dong, a Johns Hopkins Ph.D. student, studied the gene readout in the tissues housed in space and on Earth. The tissues at the space station showed increased gene production involved in inflammation and oxidative damage, also hallmarks of heart disease.

"Many of these markers of oxidative damage and inflammation are consistently demonstrated in post-flight checks of astronauts," says Mair.

Kim's lab sent a second batch of 3D engineered heart tissues to the space station in 2023 to screen for drugs that may protect the cells from the effects of low gravity. This study is ongoing, and according to the scientists, these same drugs may help people maintain heart function as they get older.

The scientists are continuing to improve their "tissue on a chip" system and are studying the effects of radiation on heart tissues at the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory. The space station is in low Earth orbit, where the planet's magnetic field shields occupants from most of the effects of space radiation.

IMAGE: Heart tissues within one of the launch-ready chambers. Credit: Jonathan Tsui

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

What are Fibroblast Cells?

he pig genome is three times closer to our genome that that of mice. Take the example of cystic fibrosis, the introduction of the mutation responsible for the disease in mice has not shown the exact course of the disease however, recent reports show the successful recapitulation of the disease in pig models. As there is a similarity between the cardiovascular system, the gastrointestinal tract, and the pancreas between pigs and humans, research on diseases and toxicology can be carried out on these models with Swine Fibroblast Cells (Walters et al, 2013).

#pig cell#fibroblast cells#pig stem cells#porcine cells#pig cells#what are fibroblast cells#what type of cells are fibroblasts#pig dna vs human dna#human and pig dna similarity#Cell culture#customized primary cells#primary cells#biotech company#stem cells#exosomes#stem cell research center#regenerative medicine#bioengineering#Kosheeka

0 notes

Text

Voting over abortion rights shows how naive and clueless you are. Natural abortifacients grow all around you. Cultures that aren’t centered around scamming each other have been using them for thousands of years. Your body will tell you when you are pregnant. Relying on doctors for any of this is a childish cry for attention. Every girl I’ve known that made a big deal over pregnancy was an attention seeking narcissist that conjured up scenarios to exploit for sympathy, attention, and resources they had no need for. They acted like they rely on doctors for all of this while telling people they’re pregnant without any medical confirmation that they’re actually pregnant. Mature intelligent women tell the least amount of people necessary and already know how to handle it themselves if they are not in the place to raise a child. Aborted babies are sold to “research companies” to sell the blood and stem cells to superstitious rich people obsessed with immortality and eternal youth.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Washington Post:

Scientists found a major clue why 4 of 5 autoimmune patients are women By Mark Johnson and Sabrina Malhi February 1, 2024 at 11:02 a.m. EST

An international team led by scientists at Stanford University has discovered a probable explanation for a decades-old biological mystery: why vastly more women than men suffer from autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

Women account for about 80 percent of the people afflicted with autoimmune diseases, a collection of more than 100 ailments that burden a combined 50 million Americans, according to the nonprofit Autoimmune Association. In simple terms, these illnesses manipulate the body’s immune system to attack healthy tissue.

In a paper published Thursday in the journal Cell, researchers present new evidence that a molecule called Xist — pronounced like the word “exist” and found only in women — is a major culprit in these diseases.

Better understanding of this molecule could lead to new tests that catch autoimmune diseases sooner and, in the longer term, to new and more effective treatments, researchers said.

Women typically have two X chromosomes, while men usually have an X and a Y. Chromosomes are tight bundles of genetic material that carry instructions for making proteins. Xist plays a crucial role by inactivating one of the X chromosomes in women, averting what would otherwise be a disastrous overproduction of proteins.

However, the research team found that in the process Xist also generates strange molecular complexes linked to many autoimmune diseases.

Although scientists conducted much of their work in mice, they made an intriguing discovery involving human patients: The Xist complexes ― long strands of RNA entangled with DNA and proteins ― trigger a chemical response in people that is a hallmark of autoimmune diseases.

Discovery of the role played by the Xist molecule does not explain how men get these diseases, or why a few autoimmune diseases, such as Type 1 diabetes, have a higher incidence among men.

“Clearly there’s got to be more, because one-tenth of lupus patients are men,” said David Karp, chief of the division of rheumatic diseases at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “So it’s not the only answer, but it’s a very interesting piece of the puzzle.”

A tale of two X’s

An illustration shows one of the two X chromosomes typically found in women being disabled to ensure the right levels of protein production. (Emily Moskal/Stanford Medicine) Autoimmune diseases have long proved difficult to address. Treatments are limited, and many of the diseases are chronic, requiring lifelong management. Most have no cure, leaving millions of Americans hoping that science will eventually offer better explanations for these ailments.

Stephanie Buxhoeveden was 25 when she began experiencing vision problems in her left eye and found herself unable to hold a syringe in her left hand — a critical tool for her nursing job. The reason: multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune condition in which the immune system attacks the protective covering of the brain, spinal cord and optic nerves.

“I was overwhelmed and scared because I knew there was no cure,” the Virginia resident said. “All of these things that I had laid out, planned and worked really hard for all of a sudden were completely up in the air and no longer guaranteed.”

Previous theories had suggested that the gender imbalance in these diseases might be caused by the main female hormones, estrogen and progesterone, or by the mere presence of a second X chromosome.

A tantalizing clue stemmed from men who have two X chromosomes and one Y chromosome, a rare condition called Klinefelter syndrome. These men run a much higher risk of suffering from autoimmune diseases, suggesting that the number of X chromosomes plays an important role.

Howard Y. Chang, senior author on the Cell paper and professor of dermatology and genetics at Stanford, said he began thinking about the ideas that led to the new discovery when he identified more than 100 proteins that either bind directly to Xist or to other proteins that bind to Xist. Looking at those collaborator proteins, he noticed that many had been linked to autoimmune diseases.

Chang and his team engineered male mice that produced Xist to test whether males that made the molecule would also have higher rates of autoimmune diseases.

Since Xist by itself is not sufficient to cause an autoimmune disease, the scientists used an environmental trigger to induce a lupus-like disease in these mice. They observed that male mice then produced Xist at levels close to those of regular female mice, and well above those of regular male mice.

In humans, genetics and environmental factors, such as a viral or bacterial infection, can also help trigger autoimmune diseases.

The scientists obtained serums from human patients with dermatomyositis, a rare autoimmune disease that causes muscle weakness and skin rash. Serum is the part of the blood that contains antibodies that fight disease. They found that in these patients, Xist complexes produce what are called autoantibodies. Instead of defending the body from invaders, as an antibody would, the autoantibody targets features of the body.

Inactivation of the second X chromosome remains an important process “that you don’t necessarily want to get rid of or tinker with too much,” said Karp of UT Southwestern.

“But this work takes it in a totally different direction, and says that the mechanism that is needed to turn off the second X chromosome, that mechanism in itself might be responsible for generating autoimmunity,” Karp said.

A better understanding of the mechanisms in these diseases would be significant if researchers can use it to develop new diagnostic tools, he added: “We are still using laboratory tests that were developed in the 1940s and ’50s and ’60s because they were easy to do, and they detected the most robust autoimmune responses.”

A long road to new treatments

Jeffrey A. Sparks, an associate physician and director of immuno-oncology and autoimmunity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who was not involved in the study, said that it will be interesting to see how the treatment options available now might fit into this newfound mechanism.

“The sky’s the limit here,” Sparks said, adding, “I think once you understand the fundamental mechanisms, you could think about developing therapies, early detection and preventions.”

Major advances in treatment, though, may be years away, according to Keith B. Elkon, an adjunct professor of immunology and associate director at the Center for Innate Immunity and Immune Diseases at the University of Washington.

Still, he said, scientific breakthroughs in the past 20 years have prolonged the lives of many people with autoimmune conditions.

“In 1950, if you’ve got a diagnosis of lupus, it would have been as bad as getting a diagnosis of cancer,” Elkon said. “But over the last 15, 20 years there’ve been really striking breakthroughs in understanding disease. It’s at the cusp of now being manageable.”

Buxhoeveden, who is now 36 and a PhD candidate in nursing, is using immunosuppressants to manage her MS. She said she was encouraged by the fact that “we’ve made progress like this study to better understand what it is that triggers it.”

#washington post#autoimmune disorder#80 percent of sufferers are women#no wonder the research too so long

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old news, but something people should remember

Never let them tell you "We didn't know covid was so bad" or "It's mild for kids." We knew.

Also preserved on our archive

By John Anderer

PHILADELPHIA, Pa. — The news about coronavirus and children just got a lot worse. A troubling study by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia reports a “high proportion” of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 show elevated levels of a biomarker tied to blood vessel damage. Making matters worse, this sign of cardiovascular damage is being seen in asymptomatic children as well as kids experiencing COVID-19 symptoms.

Additionally, many examined children testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 are being diagnosed with thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). TMA leads to clots in small blood vessels and has been linked to severe COVID symptoms among adult patients.

“We do not yet know the clinical implications of this elevated biomarker in children with COVID-19 and no symptoms or minimal symptoms,” says co-senior author David T. Teachey, MD, Director of Clinical Research at the Center for Childhood Cancer Research at CHOP, in a media release. “We should continue testing for and monitoring children with SARS-CoV-2 so that we can better understand how the virus affects them in both the short and long term.”

The complex connection between kids and COVID It’s fairly well established at this point that most children who contract coronavirus experience little to no symptoms. However, a small portion of young patients develop major symptoms or a post-viral inflammatory response to COVID-19 called Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C).

TMA in adults has a connection to more severe cases of COVID-19. Scientists believe the component of the immune system called “complement cascade” helps to mediate TMA in adults. The complement cascade is supposed to enhance and strengthen immune responses when a threat is present, but it can also backfire and lead to more inflammation. Up until now, the role of complement cascade during childhood TMA hadn’t been investigated.

To research the topic of “complement activation” in kids with SARS-CoV-2, researchers analyzed a group of 50 pediatric COVID-19 patients between April and July 2020. Among the group, 21 showed minimal to no symptoms, 11 experienced severe symptoms, and 18 developed MIS-C.

To search for complement activation and TMA among each patient, researchers used soluble C5b9 (sC5b9) as a biomarker. Scientists have used this substance for quite some time to assess the severity of TMA after stem cell procedures. In brief terms, the higher the level of sC5b9 in a transplant patient, the greater their mortality risk.

No symptoms doesn’t mean there’s no problem Study authors discovered elevated levels of C5b9 in both patients with severe COVID-19 and MIS-C. While this didn’t surprise researchers, they did get a shock from seeing high levels of C5b9 among even asymptomatic youngsters.

Some of the lab data regarding TMA had to be obtained after the fact. This meant researchers didn’t have a complete dataset to work with for all 50 studied patients. Among 22 patients researchers did have complete data for, 86 percent (19 children) were diagnosed with TMA. Every child had elevated levels of sC5b9, even those without TMA.

“Although most children with COVID-19 do not have severe disease, our study shows that there may be other effects of SARS-CoV-2 that are worthy of investigation,” Dr. Teachey concludes. “Future studies are needed to determine if hospitalized children with SARS-CoV-2 should be screened for TMA, if TMA-directed management is helpful, and if there are any short- or long-term clinical consequences of complement activation and endothelial damage in children with COVID-19 or MIS-C. The most important takeaway from this study is we have more to learn about SARS-CoV-2. We should not make guesses about the short and long-term impact of infection.”

The study is published in Blood Advances.

Study Link: ashpublications.org/bloodadvances/article/4/23/6051/474421/Evidence-of-thrombotic-microangiopathy-in-children

#mask up#covid#pandemic#covid 19#wear a mask#public health#coronavirus#sars cov 2#still coviding#wear a respirator

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 July 2017 | Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge and Prince William, Duke of Cambridge arrive for a visit of the German Cancer Research Center on the second day of their visit to Germany in Heidelberg, Germany. The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge will meet researchers including Nobel Prize winner prof. Dr. Harald zur Hausen, and visit the stem cell research lab. The royal couple are on a three-day trip to Germany that includes visits to Berlin, Hamburg and Heidelberg. (c) Thomas Niedermueller/Getty Images

#Catherine#Duchess of Cambridge#Princess of Wales#Prince William#Duke of Cambridge#Prince of Wales#Britain#2017#Thomas Niedermueller#Getty Images

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

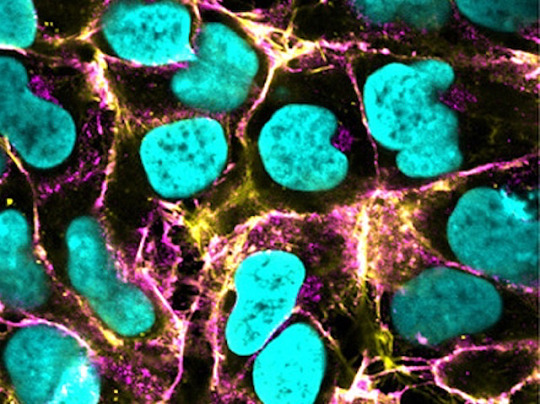

Abnormal Vessel

Faulty vessels (vascular malformations) are a feature of many human diseases. Here, anomalous vessel cells grown in the lab from manipulated human pluripotent stem cells provides a model to study their characteristics and potential treatments

Read the published research article here

Image from work by Zihang Pan and Qiyang Yao, and colleagues

Department of Physiology and Pathophysiology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, State Key Laboratory of Vascular Homeostasis and Remodeling, Clinical Stem Cell Research Center, Peking University Third Hospital, Peking University, Beijing, China

Image originally published with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Published in Cell Stem Cell, November 2024

You can also follow BPoD on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In April, researchers in China reported that they had initiated pregnancies in monkeys through a procedure seemingly much like in vitro fertilization (IVF), in which embryos created in a dish were implanted in the uteruses of cynomolgus monkeys. There seemed nothing remarkable about that—except that this was not genuine IVF, because the embryos had not been produced by fertilization. They had been constructed from scratch from monkey embryonic stem cells, with no egg or sperm involved. They were not real embryos at all, but what many researchers call embryo models (or sometimes “synthetic embryos”).

The multi-institutional team of researchers, led by Zhen Lu at the State Key Laboratory of Neuroscience in Shanghai, grew the embryo models in vitro to a roughly nine-day stage of development, making them equivalent to what is called a blastocyst in normal embryos. Then they transferred the models into eight female monkeys. In three of the monkeys, the models successfully implanted in the uterus and continued to develop. None of the pregnancies lasted more than a few days, however, before spontaneously terminating.

Meanwhile, other research groups showed last year just how far these embryo models made from stem cells can develop toward whole organisms. Teams led by Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz at the University of Cambridge and by Jacob Hanna at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, both made them from mouse stem cells and grew them in rotating glass bottles filled with nutrients, which acted like a kind of crude artificial uterus. After about eight days, it was possible to make out the central axis that would, in a normal embryo, become a spinal column, along with the bulbous blob of the nascent head and even a primitive beating heart. You’d need to be an expert to distinguish these living entities from real mouse embryos at a comparable developmental stage.

No one is entirely sure what embryo models are—biologically, ethically, or legally—or what they could ultimately become. They could be immensely useful for research, revealing aspects of our developmental processes previously beyond the reach of experiments. They might someday even be used to provide tissues and miniature organs for surgical transplantation. But they also raise profound ethical and philosophical questions.

Until recently, embryo models bore only a sketchy resemblance to real embryos, and then only at the very earliest stages of growth. But the latest experiments by Zernicka-Goetz, Hanna, and others, including the implantation experiments in Shanghai, now force us to wonder how well and how far these entities can reenact the growth of natural embryos. Even if it is currently a distant hypothetical prospect, some researchers see no reason why embryo models might not eventually have the potential to develop all the way into a baby.

There is no clear scientific or medical reason to allow them to do that, and plenty of ethical and legal reasons not to. But even their use as experimental tools raises urgent questions about regulating them. How far should embryo models be allowed to develop before we call a halt to the work? There are currently no clear regulations constraining their creation, nor any consensus on what new regulations should look like. Promising as embryo models are, they raise concerns that the research is running ahead of our ability to decide on its ethical limits.

“Embryo models hold the promise, or threat, of not just creating a realistic model of the development of some parts of important human organs, but of leading to realistic models for all human organs and tissues,” said Hank Greely, a law professor and chair of the steering committee for the Center for Biomedical Ethics at Stanford University—“and potentially, of creating new babies.”

But beyond ethical concerns, embryo models raise questions about the very definition of personhood and what counts as human. They challenge how we think about what we are.

Rethinking the 14-Day Rule

Textbooks confidently describe how a fertilized human egg gradually progresses from a uniform ball of cells to a shrimp-shaped implanted embryo to a recognizably human fetus. But we know disturbingly little about that process because some details of it can’t be studied in the womb without compromising the safety of the embryo. And in many countries, it is legal for human embryos to be grown and studied in vitro for only up to 14 days, after which they must be terminated.

That two-week point is when one of the most crucial stages of development occurs, called gastrulation. As the developmental biologist Lewis Wolpert put it, “It is not birth, marriage, or death, but gastrulation which is truly the most important time in your life.” That is when the rather featureless blob of embryonic cells starts to fold and rearrange itself to acquire the first hints of body structure. The cells begin to specialize into the tissues that will form the nerves, internal organs, gut, and more. A central furrow called the primitive streak develops as the precursor to the spinal column, defining the nascent body’s central axis of bilateral symmetry.

In 1990, following reports from the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare and the UK Warnock Committee years earlier, many countries decided that the formation of the primitive streak at 14 days should mark the limit for how long human embryos could be sustained in vitro. This 14-day rule was subsequently implemented in the guidelines of the International Society for Stem Cell Research, which are widely followed by scientists worldwide. For decades, it was a comfortable restriction, since human embryos generally stopped growing in vitro after only five to six days, around the stage when they would normally implant in the uterine lining.

In 2016, however, Zernicka-Goetz’s team at Cambridge and the developmental biologist Ali Brivanlou at Rockefeller University and his colleagues showed that they could grow IVF mouse embryos all the way up to the gastrulation stage, using a soft polymer gel matrix as a kind of uterine surrogate.

Hanna and his coworkers showed in 2021 that they could grow natural mouse embryos in vitro far beyond gastrulation. Using their rotating bioreactor, in which the embryos were sustained in a nutrient solution and an atmosphere with precisely controlled oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, the team grew mouse embryos for 12 days, half of the full gestation period for mice. Hanna thinks the technology could also work with human embryos and could perhaps grow them for many weeks—if the aims of the science justified the project responsibly and the law did not forbid it.

Recognizing the new potential for finding out useful information about how human embryos develop post-gastrulation, the International Society for Stem Cell Research revised its guidelines in 2021. It now recommends that the 14-day limit on human embryo research be relaxed on a case-by-case basis if a good scientific case can be made for extending it. No country has yet modified its laws to take advantage of that latitude.

Embryo models might offer a way to go down that path with even fewer legal and ethical restrictions. They are not legally considered to be embryos because they do not have the potential to grow into viable organisms. So even under present guidelines and regulations in many countries, if embryo models can be grown through gastrulation and beyond, it could become legal for the first time to experimentally study human development and perhaps lead to a better understanding of defects that cause miscarriages or deformities.

But if embryo models can indeed grow that far, at what point do they stop being models and become equivalent to the real thing? The better and further along the models get, the blurrier the biological and ethical boundaries become.

That dilemma was hypothetical when embryo models could only recapitulate the very earliest stages of development. It isn’t anymore.

Turning Stem Cells Into Embryos

Embryo models are generally made from embryonic stem cells, “pluripotent” cells derived from early embryos that can develop into every tissue type in the body. By the time an embryo has reached the blastocyst stage—around day 5 or 6 in human development—it consists of several cell types. Its hollow shell is made of cells that will form the placenta (called trophoblast stem cells, or TSCs) and the yolk sac (the extra-embryonic endoderm, or XEN cells). The pluripotent cells that will become the fetus are confined to a blob on the inside of the blastocyst wall, and it is from them that embryonic stem cells can be cultured.

Experiments in the 1990s and early 2000s showed that embryonic stem cells extracted from one blastocyst and transferred into another can still become an embryo capable of developing all the way to full-term birth as a healthy animal. But the support provided by TSCs and XEN cells is essential—embryonic stem cells alone can’t get past the first few days of development unless they are in a blastocyst.

More recent research, however, shows that embryo-like structures can be made from scratch from the respective cell types. In 2018, Zernicka-Goetz and her colleagues showed that assemblies of embryonic stem cells, TSCs, and XEN cells from mice could self-organize into a hollow form shaped like a peanut shell and comparable in appearance to a regular embryo undergoing gastrulation. As gastrulation proceeded, some of the embryonic stem cells showed signs of getting more specialized and mobile as a prelude to the development of internal organs.

But those early embryo models were flawed, Zernicka-Goetz said, because the added XEN cells were at too late a developmental stage to wholly fulfill their role. To solve that problem, in 2021 her group found a way to convert embryonic stem cells into early-stage XEN cells. “When we placed [embryonic stem cells], TSCs, and these induced-XEN cells together, they could now undergo gastrulation properly and initiate development of organs,” she said.

Last summer in Nature, Zernicka-Goetz and her collaborators described how they had used a rotating bottle incubator to extend the growth of their mouse embryo models by another crucial 24 hours, to day 8.5. Then the models formed “all regions of the brain, beating hearts, and so on,” she said. Their trunk showed segments arising for development into different parts of the body. They had a neural tube, a gut, and the progenitors of egg and sperm cells.

In a second paper published around the same time in Cell Stem Cell, her group induced embryonic stem cells to become TSCs, as well as XEN cells. Those embryo models, cultivated in the rotating incubator, developed to the same advanced stage.

Meanwhile, Hanna’s team in Israel was growing mouse embryo models in a similar way, as they described in a paper in Cell that was published shortly before the paper from Zernicka-Goetz’s group. Hanna’s models too were made solely from embryonic stem cells, some of which had been genetically coaxed to become TSCs and XEN cells. “The entire synthetic organ-filled embryo, including extra-embryonic membranes, can all be generated by starting only with naive pluripotent stem cells,” Hanna said.

Hanna’s embryo models, like those made by Zernicka-Goetz, passed through all the expected early developmental stages. After 8.5 days, they had a crude body shape, with head, limb buds, a heart, and other organs. Their bodies were attached to a pseudo-placenta made of TSCs by a column of cells like an umbilical cord.

“These embryo models recapitulate natural embryogenesis very well,” Zernicka-Goetz said. The main differences may be consequences of the placenta forming improperly, since it cannot contact a uterus. Imperfect signals from the flawed placenta may impair the healthy growth of some embryonic tissue structures.

Without a better substitute for a placenta, “it remains to be seen how much further these structures will develop,” she said. That’s why she thinks the next big challenge will be to take embryo models through a stage of development that normally requires a placenta as an interface for the circulating blood systems of the mother and fetus. No one has yet found a way to do that in vitro, but she says her group is working on it.

Hanna acknowledged that he was surprised by how well the embryo models continued to grow beyond gastrulation. But he added that after working on this for 12 years, “you are excited and surprised at every milestone, but in one or two days you get used to it and take it for granted, and you focus on the next goal.”

Jun Wu, a stem cell biologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, was also surprised that embryo models made from embryonic stem cells alone can get so far. “The fact that they can form embryo-like structures with clear early organogenesis suggests we can obtain seemingly functional tissues ex utero, purely based on stem cells,” he said.

In a further wrinkle, it turns out that embryo models do not have to be grown from literal embryonic stem cells—that is, stem cells harvested from actual embryos. They can also be grown from mature cells taken from you or me and regressed to a stem cell-like state. The possibility of such a “rejuvenation” of mature cell types was the revolutionary discovery of the Japanese biologist Shinya Yamanaka, which won him a share of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Such reprogrammed cells are called induced pluripotent stem cells, and they are made by injecting mature cells (such as skin cells) with a few of the key genes active in embryonic stem cells.

So far, induced pluripotent stem cells seem able to do pretty much anything that real embryonic stem cells can do, including growing into embryo-like structures in vitro. And that success seems to sever the last essential connection between embryo models and real embryos: You don’t need an embryo to make them, which puts them largely outside existing regulations.

Growing Organs in the Lab

Even if embryo models have unprecedented similarity to real embryos, they still have many shortcomings. Nicolas Rivron, a stem cell biologist and embryologist at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology in Vienna, acknowledges that “embryo models are rudimentary, imperfect, inefficient, and lack the capacity of giving rise to a living organism.”

The failure rate for growing embryo models is very high: Fewer than 1 percent of the initial cell clusters make it very far. Subtle abnormalities, mostly involving disproportionate organ sizes, often snuff them out, Hanna said. Wu believes more work is needed to understand both the similarities to normal embryos and the differences that may explain why mouse embryo models haven’t been able to grow beyond 8.5 days.

Still, Hanna is confident that they will be able to extend that limit by improving the culture device. “We can currently grow [IVF] mouse embryos ex utero until day 13.5—the equivalent for human embryos will be around day 50 to 60,” he said. “Our system opens the door.”

He added, “When it comes to studying early human development, I believe this is the only possible way.”

Marta Shahbazi, a cell biologist at Cambridge who works on embryogenesis, agrees. “For humans, an equivalent system [to mouse embryo models] would be really useful, because we don’t have an in vivo alternative to study gastrulation and early organogenesis,” she said.

Already, both Zernicka-Goetz and Hanna are making rapid progress with human embryo models. On June 15, their two groups simultaneously posted preprints describing the growth of such structures derived entirely from human pluripotent stem cells that they claimed to develop in vitro all the way to a stage equivalent to that of a normal embryo 13 to 14 days after fertilization. The researchers say that their human embryo models show some of the key developmental features of natural ones at this same stage, although those claims have yet to be peer-reviewed. At this rate of advance, it will surely soon be possible in principle to grow these entities beyond the widely observed 14-day legal limit—forcing the question of whether we should.

In theory, human embryo models grown to an advanced stage of development could become sources of organs for transplants and research. “Although the synthetic embryoids we make are distinguishable from natural embryos,” Hanna said, “they still have all [nascent] organs, and in the right position.”

Embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells in vitro can currently be guided to grow into rudimentary miniature organs (or “organoids”) of pancreatic, kidney, and even brain tissue. But organoids typically fail to reproduce the structure of real organs accurately, probably because they lack essential signals and multicellular components that would arise naturally in real embryos. “We anticipate that these defects might be corrected by generating structures that recapitulate natural processes occurring in development,” Zernicka-Goetz said.

Hanna thinks that embryo models could also be used to identify drug targets and screen for novel therapeutics, particularly for reproductive problems, such as infertility, pregnancy loss, endometriosis, and preeclampsia. “This is providing an ethical and technical alternative to the use of embryos, oocytes, or abortion-derived materials and is consistent with the latest ISSCR guidelines,” he said. He has already founded a company to test potential clinical applications of human embryo models.

But Alfonso Martinez Arias, a developmental biologist at Cambridge and Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona who studies the role of embryonic stem cells in mammalian development, stresses that such applications remain unproven. He thinks it is hard to see how much could be understood about questions of real embryo growth from the development of such a distorted version.

Besides, he said, none of this has yet been shown in humans. “I do not think we should advance a field through wishful thinking, but with facts,” he said.

The Ethical Frontier

As long as embryo models remain just models, their use in research and medicine may not arouse much controversy. “A basic ethics principle called subsidiarity stipulates that a scientific or biomedical goal should be achieved using the least morally problematic way,” Rivron said. For research on global health concerns, such as family planning, he said, studies of embryo models seem like a less ethically challenging alternative than work on IVF embryos.

“We should remember that synthetic embryos are not real embryos,” Hanna said. So far, they lack the crucial potential to grow into a true fetus, let alone a baby: If they are implanted in mice, they don’t develop further.

But the capacity for further development is central to the ethical status of the embryo models, and there’s no guarantee that their current inability to yield fetuses and live births will persist.

Rivron agrees that the work on embryo models that he and others are doing could lead to a new reproductive technology. “We can foresee that the most complete embryo models will at some point tip over to become embryos, giving rise to individuals,” he said. “I believe these individuals should be fully entitled as beings, independent of the way they formed.”

For that reason, he is working with ethicists to shape an ethical framework for these studies. “Attempting to use human embryos formed from stem cells for assisted reproduction might become possible one day,” he said, “but it would require an exhaustive prior discussion and evaluation on whether it is safe, socially and ethically justifiable, and desirable.”

But the ethical issues don’t kick in only if the technology is used for human reproduction. Greely believes that “if an embryo model is ‘similar enough’ to a ‘normal’ human embryo, it should be treated as a human embryo for statutory and regulatory purposes, including, but not limited to, the 14-day rule or any revision of it.”

What counts as similar enough? That criterion would be met, he said, “if the embryo model has a significant probability of being able to produce a living human baby.”

The trouble is, it could be very hard to know for sure whether that’s the case, short of implanting a human embryo model in a uterus. The only way to determine the ethical status of such an entity might then be unethical.

Work like that of the Chinese team with monkey embryo models, however, might foreclose that uncertainty. If these embryo-like entities can induce pregnancies and someday yield offspring in monkeys, we might reasonably infer that equivalent human embryo models could too. In a commentary on that work, Insoo Hyun, the director of research ethics at Harvard Medical School’s Center for Bioethics, wrote: “It is at this point that human embryo models could be deemed to be so accurate that they would amount to being the real thing functionally.”

Such a result, even if only in monkeys, might lead regulators to decide that human embryo models deserve to be treated like embryos, with all the attendant restrictions. Some researchers feel that we urgently need a new definition of an embryo to offer clarity and keep pace with the scientific advances. If there is good reason to suppose an embryo model has the potential to generate viable offspring, we will need to either accept the regulatory implications or find ways to nullify that potential.

These are the dilemmas of a technique that could blur our old ideas about what qualifies as human, and about how people are created. Bartha Maria Knoppers, a professor and research chair at McGill University in Canada and an authority on research ethics, wrote a commentary for Science with Greely in which they described developments like embryo models as “nibbling at the legal definition of what a human is.” The more we discover about how we are made and how we could be, the less clear it is that science can bring clarity to that question.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Innovative Non-Surgical Treatments for Chronic Back Pain and Arthritis in Mumbai

Introduction

Chronic back pain is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal issues affecting individuals of all ages. Whether caused by aging, injury, arthritis, or spinal degeneration, persistent back pain can severely impact quality of life. Traditionally, patients often resorted to invasive surgical procedures or long-term medication regimens to manage their condition. However, with significant advancements in regenerative medicine, non-surgical alternatives are becoming increasingly popular—and effective.

In cities like Mumbai, cutting-edge therapies such as PRP Therapy for back pain, Stem Cell Therapy for back pain Arthritis, and other forms of non-surgical back pain treatment are now readily accessible. These innovative techniques offer promising relief to patients who want to avoid the risks and downtime associated with surgery.

Understanding Back Pain and Arthritis: Causes and Impact

Back pain can stem from various underlying causes, including:

Degenerative Disc Disease (DDD)

Facet Joint Syndrome

Herniated Discs

Spinal Stenosis

Osteoarthritis or Rheumatoid Arthritis

In Mumbai, with its fast-paced urban lifestyle, many individuals experience mechanical strain or degenerative changes that contribute to chronic pain. Arthritis of the spine, particularly osteoarthritis, leads to inflammation and stiffness in the vertebral joints, significantly reducing mobility and comfort.

The Need for Non-Surgical Back Pain Treatment in Mumbai

With the rising demand for minimally invasive treatment options, there has been a significant shift toward non-surgical back pain treatments in Mumbai. These approaches focus on:

Preserving native tissue

Stimulating the body’s natural healing response

Minimizing recovery time

Avoiding dependency on pain medications

Among the leading therapies, Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) and Stem Cell Therapy stand out for their regenerative potential and growing clinical evidence.

PRP Therapy for Back Pain in Mumbai

PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) Therapy is a revolutionary treatment that uses the patient’s own blood to promote healing. After drawing a small sample of blood, it is processed to concentrate the platelets, which are then injected into the damaged area of the spine or surrounding tissues.

Benefits of PRP Therapy:

Reduces inflammation and pain

Improves tissue repair and regeneration

Minimally invasive with low risk of complications

Short recovery time

In Mumbai, many orthopedic and pain management clinics now offer PRP Therapy for back pain, particularly for conditions such as:

Lumbar facet joint pain

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

Muscle injuries and tendon inflammation

Patients often report reduced pain levels within a few weeks and sustained improvement over several months.

Stem Cell Treatment for Back Pain and Arthritis in Mumbai

Stem Cell Therapy represents the frontier of regenerative medicine. It involves harvesting mesenchymal stem cells (usually from the patient’s bone marrow or adipose tissue) and injecting them into damaged spinal discs or arthritic joints.

These stem cells have the unique ability to:

Differentiate into cartilage, bone, or soft tissue cells

Modulate inflammation

Support long-term structural repair

Indications for Stem Cell Therapy:

Chronic lower back pain

Disc degeneration

Arthritic changes in the spine

Many patients who undergo stem cell treatment for back pain in Mumbai report substantial improvements in mobility, reduction in pain, and enhanced quality of life—without needing surgery.

Why Mumbai is Becoming a Hub for Regenerative Orthopedic Care

Mumbai boasts a number of advanced orthopedic clinics and research-driven hospitals offering regenerative therapies. Patients benefit from:

Internationally accredited medical centers

Experienced orthopedic surgeons and pain specialists

Availability of autologous (patient-derived) stem cell and PRP procedures

State-of-the-art imaging and guided injection techniques

Additionally, the cost of Stem Cell Therapy for back pain Arthritis in Mumbai is often more affordable compared to western countries, making the city a medical tourism destination for non-surgical back pain treatments.

Patient Outcomes and Clinical Insights

A growing body of research supports the effectiveness of PRP and stem cell treatments. Clinical trials and observational studies show that regenerative therapies can:

Delay or eliminate the need for spinal surgery

Provide significant pain relief in arthritic spine conditions

Enhance disc hydration and joint flexibility

Reduce dependency on opioid medications

Mumbai-based clinics often integrate these therapies into comprehensive pain management programs, which may also include physiotherapy, chiropractic care, and ergonomic rehabilitation.

Is Regenerative Therapy Right for You?

Not all patients are immediate candidates for PRP or stem cell therapy. An initial evaluation typically includes:

Detailed medical history and physical examination

Imaging (MRI, X-ray, or CT scan)

Pain scoring and functional assessment

Ideal candidates include those with moderate to severe back pain due to degenerative changes, arthritis, or disc-related conditions who are not responding to conservative treatments.

Conclusion

With technological advancement and medical innovation, non-surgical back pain treatment in Mumbai has reached new heights. PRP Therapy for back pain and Stem Cell Therapy for back pain Arthritis are transforming the landscape of orthopedic care—offering pain relief, improved mobility, and enhanced quality of life without the risks associated with traditional surgery. If you or a loved one is struggling with chronic back pain, consult a regenerative medicine specialist in Mumbai to explore these groundbreaking treatment options.

#back pain#back pain treatment#stem cell therapy#prp treatments#non-surgical orthopedic solutions#regenerative orthopedic treatments

0 notes