#spinners and weavers united

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It finally dropped *-*

#pagan music#indie music#local music#spooky#viking#asatru#mystical#johnny hexx#spinners and weavers united#pagan lgbtq art#trance#pagan trance#pagan devotional music#tuneful pagan howling#tribal drums#bardic#new music#Spotify

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Historical Society of Rockland County Invites You to Join Us for

Historic Fiber and Textile Arts

A Special Presentation by Celeste Sherry

When: Thursday, April 20, 2023, 7:00 pm SHARP

Where: Community Room, HSRC History Center, 20 Zukor Road, New City

Admission: $FREE (Reservations are required and donations are appreciated)

Before the industrial revolution, fiber and textile arts were a vital part of farmwork for families like the Blauvelts. Celeste Sherry, an expert spinner and living historian, as she discusses the history of spinning and textiles from the Stone Age to the 19th century.

Following a demonstration of fiber spinning on her antique and reproduction spinning wheels, attendees can try their hand at wool picking, combing, carding, and spinning with a variety of natural fibers.

About the presenter: Celeste brings more than forty years of experience in history and fiber spinning, as well as a career teaching English literature at two local Rockland County colleges. She is a member of the Palisades Guild of Spinners abd Weavers; Mid-Atlantic Fiber Association (MAFA); 4th Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers, Living History Unit; and the Brigade of the American Revolution Living History Organization. She lives in West Nyack.

TO RESERVE YOUR SEAT FOR THIS PRESENTATION visit EVENTBRITE:

Or you can email us at info@rockland history, or call us at (845) 634-9629.

***

Historical Society of Rockland County

20 Zukor Road

New City, NY 10956

Phone: (845) 634-9629

Please note: Space is limited for this lecture. Reservations are required. A waiting list will be compiled, and available spaces will be filled on a first-come, first-served basis.

***

The Historical Society of Rockland County is a nonprofit educational institution and principal repository for original documents and artifacts relating to Rockland County. Its headquarters are a four-acre site featuring a history museum and the 1832 Jacob Blauvelt House in New City, New York. www.RocklandHistory.org.

1 note

·

View note

Note

i see you have discovered history professor bret deveraux, my beloved. i highly recommend his battle of helm's deep and pelennor fields series if you want to learn about historical battlefield tactics (and operations and strategies) and his fremen mirage series if you want to learn about the facist view of history and why it's complete and utter bullshit. his series on sparta is also phenomenal

I'm having such a good time working through his back catalogue. AGreatDivorce on Youtube has recorded audio versions of many of his posts, which is a godsend for me.

The Fremen Mirage series was a balm to my soul after having to deal with SO many "military history buffs" and SFF reply guys who think that violence is the pinnacle of human achievement, and therefore acknowledging the personhood of anyone but the apex warriors is like, taking resources away from the war effort or something.

For the uninitiated, the "Fremen Mirage" is what Devereaux calls a "pop theory of history" that believes:

that a lack of wealth and sophistication leads to moral purity, which in turn leads to military prowess, which consequently produces a cycle of history wherein rich and decadent societies are forever being overthrown by poor, but hardy ‘Fremen’ who then become rich and decadent in their turn. Or, as the meme, originally coined by G. Michael Hopf puts it, “Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. And weak men create hard times.”

And then in his series he applies rigorous historical analysis to this idea, and takes it apart like Christmas wrapping. It's almost as fun as the Sparta series, where he demonstrates that Spartans would hate their modern fanboys, and also aren't actually as special or amazing as they're made out to be.

After a while, though, I got tired of the military side of things, and gone wandering. What I've found most refreshing this week were posts that take a step back from direct pop culture criticism and just simply lay out the material realities of life in the past. The really basic building blocks that help us get in tune with the daily life of the past. Stuff like the Lonely City series.

Or the clothing series! I said that I've been trying to figure out just how rare or common looms were, and while I've been looking at archeological evidence of loom types, he's just found the numbers that let me calculate it.

I'm using a base unit of 5 yards of cloth, which is, with a generous hand wiggle, enough to make one person's outfit, maybe two.

According to these estimates:

In the early middle ages, using a hand spindle and warp-weighted loom, that might take about 70 hours of weaving and, at a low estimate, 500 hours of spinning. If someone devoted eight hours a day to nothing but spinning yarn, it would take them over two months to have enough to weave with.

In the Late Middle Ages, with the invention of the spinning wheel and horizontal loom, that figure would go down to 180 hours of spinning and 30 hours of weaving. The change in technology reduces the time down to almost a third of what it was before!

This really settles for me the question I had about my early-medieval fantasy setting, which is that there would be a lot of looms, a loom in every household, and that it would not at all be out of place for even aristocratic women to spin and weave on a regular basis.

Which like, to be cranky about fantasy heroines who hate sewing: In that kind of world, embroidery is a luxury. Weavers and spinners have to bust their butts just to put clothes on everybody's backs. Spinning and weaving that much is gruelling work that I would absolutely understand hating. However, it is not stupid, silly, or useless. Being able to embroider—to do something primarily decorative and artistic, just because it looks good and feels nice—is likely to be more of an escape from drudgery than the drudgery itself.

It really can't be overstated, how much the Industrial Revolution was a textile revolution. Our relationship to cloth and clothing has transformed out of all recognition over the last 300 years. There are undeniable advantages to this, because it frees us to do so many other things with our time. But it also makes it tough to look back into the past clearly, because it's so easy to forget that the burdens we've shed still existed back then.

619 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...A lone woman could, if she spun in almost every spare minute of her day, on her own keep a small family clothed in minimum comfort (and we know they did that). Adding a second spinner – even if they were less efficient (like a young girl just learning the craft or an older woman who has lost some dexterity in her hands) could push the household further into the ‘comfort’ margin, and we have to imagine that most of that added textile production would be consumed by the family (because people like having nice clothes!).

At the same time, that rate of production is high enough that a household which found itself bereft of (male) farmers (for instance due to a draft or military mortality) might well be able to patch the temporary hole in the family finances by dropping its textile consumption down to that minimum and selling or trading away the excess, for which there seems to have always been demand. ...Consequently, the line between women spinning for their own household and women spinning for the market often must have been merely a function of the financial situation of the family and the balance of clothing requirements to spinners in the household unit (much the same way agricultural surplus functioned).

Moreover, spinning absolutely dominates production time (again, around 85% of all of the labor-time, a ratio that the spinning wheel and the horizontal loom together don’t really change). This is actually quite handy, in a way, as we’ll see, because spinning (at least with a distaff) could be a mobile activity; a spinner could carry their spindle and distaff with them and set up almost anywhere, making use of small scraps of time here or there.

On the flip side, the labor demands here are high enough prior to the advent of better spinning and weaving technology in the Late Middle Ages (read: the spinning wheel, which is the truly revolutionary labor-saving device here) that most women would be spinning functionally all of the time, a constant background activity begun and carried out whenever they weren’t required to be actively moving around in order to fulfill a very real subsistence need for clothing in climates that humans are not particularly well adapted to naturally. The work of the spinner was every bit as important for maintaining the household as the work of the farmer and frankly students of history ought to see the two jobs as necessary and equal mirrors of each other.

At the same time, just as all farmers were not free, so all spinners were not free. It is abundantly clear that among the many tasks assigned to enslaved women within ancient households. Xenophon lists training the enslaved women of the household in wool-working as one of the duties of a good wife (Xen. Oik. 7.41). ...Columella also emphasizes that the vilica ought to be continually rotating between the spinners, weavers, cooks, cowsheds, pens and sickrooms, making use of the mobility that the distaff offered while her enslaved husband was out in the fields supervising the agricultural labor (of course, as with the bit of Xenophon above, the same sort of behavior would have been expected of the free wife as mistress of her own household).

...Consequently spinning and weaving were tasks that might be shared between both relatively elite women and far poorer and even enslaved women, though we should be sure not to take this too far. Doubtless it was a rather more pleasant experience to be the wealthy woman supervising enslaved or hired hands working wool in a large household than it was to be one of those enslaved women, or the wife of a very poor farmer desperately spinning to keep the farm afloat and the family fed. The poor woman spinner – who spins because she lacks a male wage-earner to support her – is a fixture of late medieval and early modern European society and (as J.S. Lee’s wage data makes clear; spinners were not paid well) must have also had quite a rough time of things.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of household textile production in the shaping of pre-modern gender roles. It infiltrates our language even today; a matrilineal line in a family is sometimes called a ‘distaff line,’ the female half of a male-female gendered pair is sometimes the ‘distaff counterpart’ for the same reason. Women who do not marry are sometimes still called ‘spinsters’ on the assumption that an unmarried woman would have to support herself by spinning and selling yarn (I’m not endorsing these usages, merely noting they exist).

E.W. Barber (Women’s Work, 29-41) suggests that this division of labor, which holds across a wide variety of societies was a product of the demands of the one necessarily gendered task in pre-modern societies: child-rearing. Barber notes that tasks compatible with the demands of keeping track of small children are those which do not require total attention (at least when full proficiency is reached; spinning is not exactly an easy task, but a skilled spinner can very easily spin while watching someone else and talking to a third person), can easily be interrupted, is not dangerous, can be easily moved, but do not require travel far from home; as Barber is quick to note, producing textiles (and spinning in particular) fill all of these requirements perfectly and that “the only other occupation that fits the criteria even half so well is that of preparing the daily food” which of course was also a female-gendered activity in most ancient societies. Barber thus essentially argues that it was the close coincidence of the demands of textile-production and child-rearing which led to the dominant paradigm where this work was ‘women’s work’ as per her title.

(There is some irony that while the men of patriarchal societies of antiquity – which is to say effectively all of the societies of antiquity – tended to see the gendered division of labor as a consequence of male superiority, it is in fact male incapability, particularly the male inability to nurse an infant, which structured the gendered division of labor in pre-modern societies, until the steady march of technology rendered the division itself obsolete. Also, and Barber points this out, citing Judith Brown, we should see this is a question about ability rather than reliance, just as some men did spin, weave and sew (again, often in a commercial capacity), so too did some women farm, gather or hunt. It is only the very rare and quite stupid person who will starve or freeze merely to adhere to gender roles and even then gender roles were often much more plastic in practice than stereotypes make them seem.)

Spinning became a central motif in many societies for ideal womanhood. Of course one foot of the fundament of Greek literature stands on the Odyssey, where Penelope’s defining act of arete is the clever weaving and unweaving of a burial shroud to deceive the suitors, but examples do not stop there. Lucretia, one of the key figures in the Roman legends concerning the foundation of the Republic, is marked out as outstanding among women because, when a group of aristocrats sneak home to try to settle a bet over who has the best wife, she is patiently spinning late into the night (with the enslaved women of her house working around her; often they get translated as ‘maids’ in a bit of bowdlerization. Any time you see ‘maids’ in the translation of a Greek or Roman text referring to household workers, it is usually quite safe to assume they are enslaved women) while the other women are out drinking (Liv. 1.57). This display of virtue causes the prince Sextus Tarquinius to form designs on Lucretia (which, being virtuous, she refuses), setting in motion the chain of crime and vengeance which will overthrow Rome’s monarchy. The purpose of Lucretia’s wool-working in the story is to establish her supreme virtue as the perfect aristocratic wife.

...For myself, I find that students can fairly readily understand the centrality of farming in everyday life in the pre-modern world, but are slower to grasp spinning and weaving (often tacitly assuming that women were effectively idle, or generically ‘homemaking’ in ways that precluded production). And students cannot be faulted for this – they generally aren’t confronted with this reality in classes or in popular culture. ...Even more than farming or blacksmithing, this is an economic and household activity that is rendered invisible in the popular imagination of the past, even as (as you can see from the artwork in this post) it was a dominant visual motif for representing the work of women for centuries.”

- Bret Devereaux, “Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part III: Spin Me Right Round…”

9K notes

·

View notes

Photo

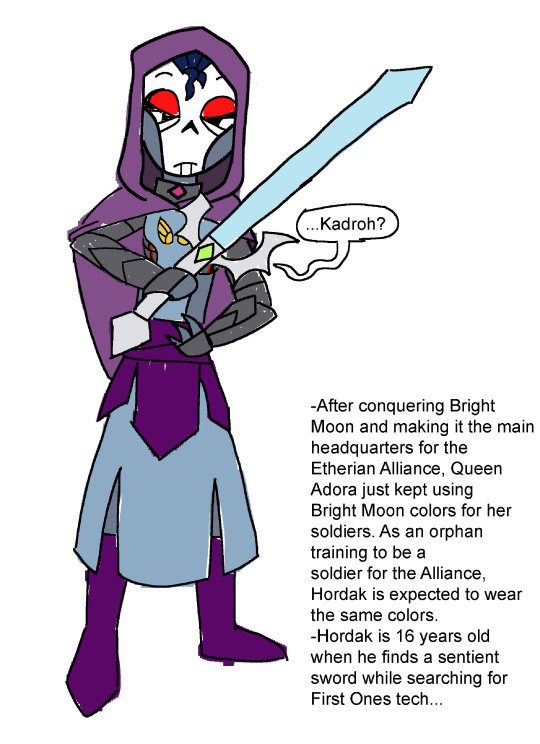

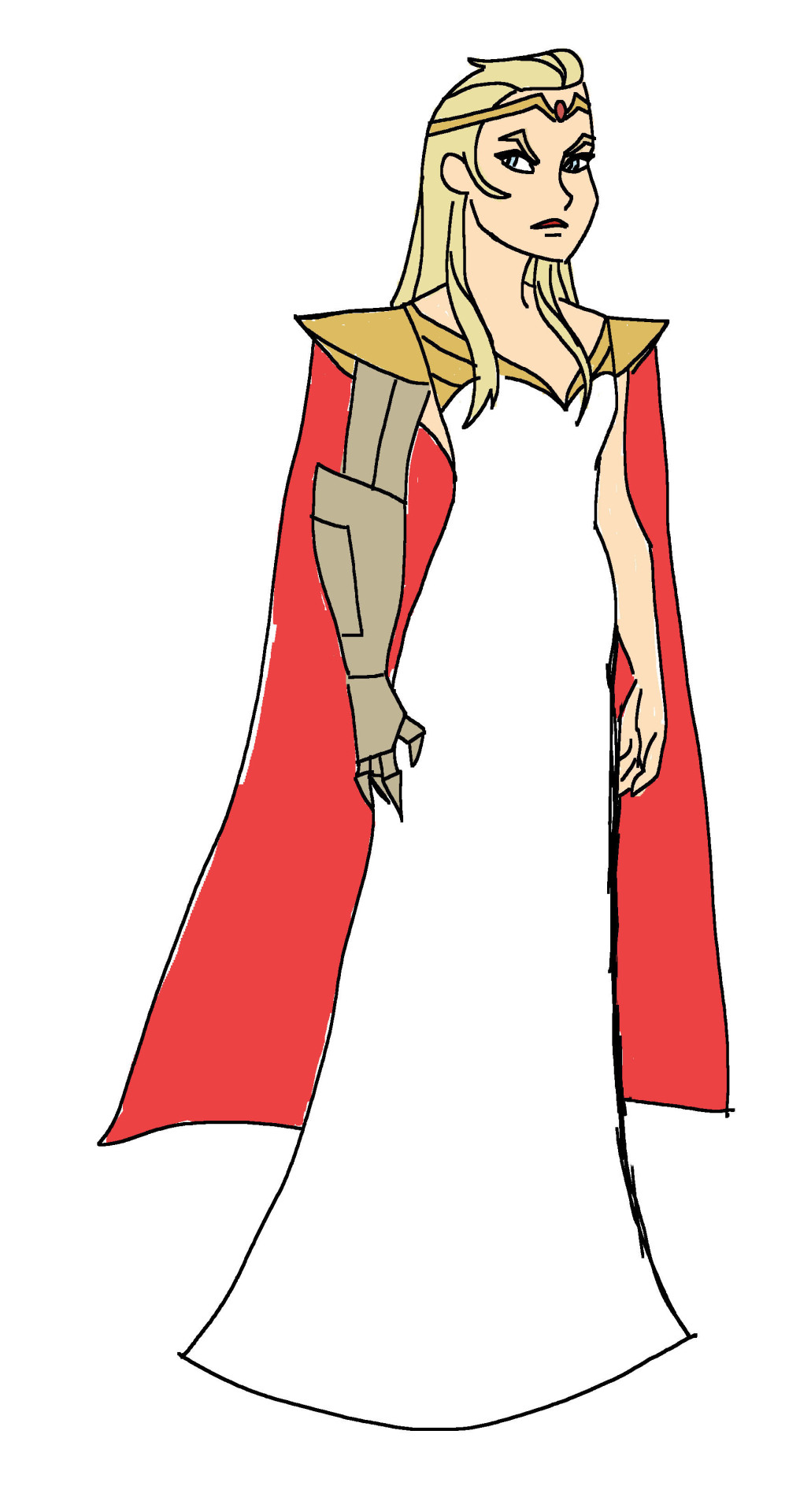

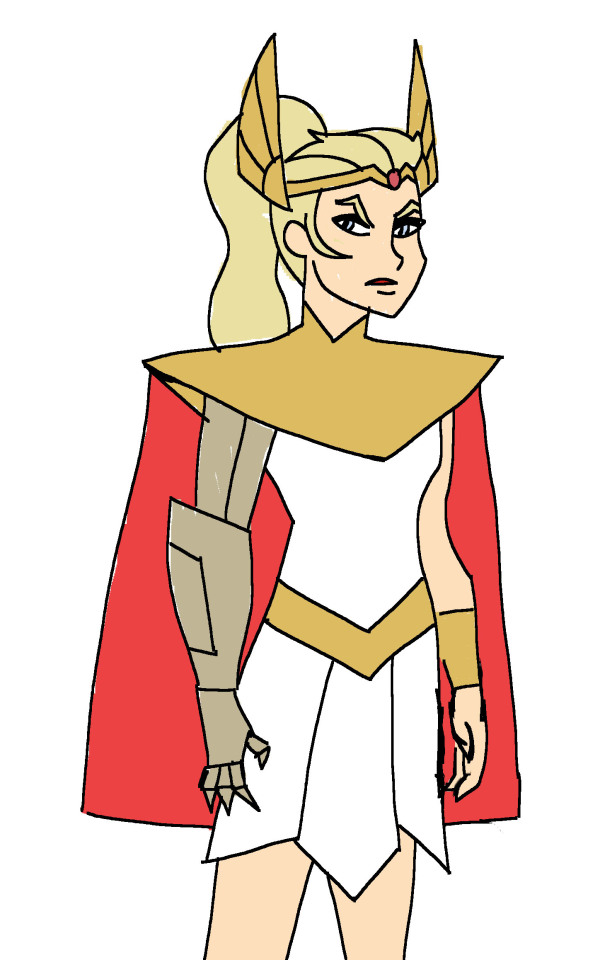

Interesting meta from cruelfeline and others inspired my idea for a role swap AU where the main swap is between Hordak and Adora! There are other character swaps in the AU too, or swap variations.

Hordak is the latest Prim-Al, a living weapon that a First Ones faction clones over and over again each time one perishes in battle. FO created Prim-Al in response to their magitech AI Light Hope going rogue and constructing her own army of androids she calls the She-Ra.

More under the cut, including Queen Adora, leader of the Etherian Alliance and stranded android still loyal to her creator, and her discovery of a baby Hordak (Content Warnings: ableism; child abuse; Catra is a villain and completes her transformation into a Shadow Weaver-like figure, and the implications of that):

But first, a little more summed up detail on Prim-Al’s deal, because there’s more to it:

-Hordak’s genetic template is a mysterious Subject A. The FO took preserved samples of Subject A to continually make clones of him for Prim-Al.

-FO also made a digital copy of Subject A’s mind, a magitech AI named Prime. As a digital clone of an organic mind, much of him acts like an organic mind. Though FO has added some heavy programming and other alterations, they’ve tried to leave much of the organic-based behavior intact for multiple reasons--as an ongoing experiment in digital clones of minds, as an attempt to deter another rogue AI by trying to make this AI more aligned with organics (in contrast, RS!Light Hope was generally not based on an individual’s organic mind, she is not a digital clone like RS!Prime).

(Magitech is what it sounds like--a typically powerful fusion of magic and technology.)

-AI Prime is contained in the RS!Sword of Protection, and is actually the key to its power.

-The clones are actually vessels that channel magitech AI Prime through the sword. When a clone holds the sword, they sync with AI Prime inside, and together they essentially fuse and transform into Prim-Al.

-Prim-Al occurs in two stages. The first stage has some boost in power, some physical changes in body and clothes. The last stage has a greater boost in power and more physical changes--aged up (to a certain point), more muscular, longer hair, clothes, etc.

-AI Prime will only grant power to the clones/can only sync with the clones because they share a blood connection to the organic mind he was based on. This reaction is largely rooted in AI Prime’s magitech nature.

-Despite the death of Subject A, FO was able to preserve his mind and DNA to continue weaponizing him via biological and digital cloning. (The reasons for the FO’s focus on Subject A are also classified, though one can infer that Subject A possessed a power FO wanted to preserve and control....)

-AI Prime/the Sword of Protection is passed down through multiple iterations of Prim-Al.

-One of AI Prime’s functions is to also serve as a living archive of information, and so AI Prime remembers every Prim-Al. He is supposed to have this information available for new clone vessels to access.

-The clones do get names, but as they mature FO generally uses them less and refers to them as Prim-Al more. FO generally mistreat Prim-Al/clone vessels/AI Prime, seeing them as just weapons to keep under control.

FO doesn’t create a clone army because they’re honestly paranoid about creating another powerful enemy; they think that just one Prim-Al under selective limitations will grant them better control and avoid another Light Hope debacle. There are other classified reasons for this too. Also a FO faction created Prim-Al; the entirety of FO are embroiled in a civil war among each other as well as the war with Light Hope and other enemies.

The FO also put limitations on AI Prime for similar reasons, and all the more so because he’s an AI--they don’t want AI Prime to be another rogue AI like Light Hope.

Feel like sharing some design/tone notes:

Besides playing around with fusing traits from both Hordak and Horde Prime, I was also influenced by Link and the Master Sword in Breath of the Wild, as well as the Drifter in Hyper Light Drifter.

(Above: Base Form!RS!Adora is partly a drawover of a show image.)

The She-Ra units are magitech androids with a base form and a more powerful form they can transform into. This transformation is rooted in their magitech nature.

Gonna try to keep these notes on the art as more of a summary for now, and may reveal more specific details about the role swap AU later in separate text posts or even just keep it to later fic--also, still brainstorming, so material in the sketches and the text may change later; and also just felt like this art needed more context/clarification/background info:

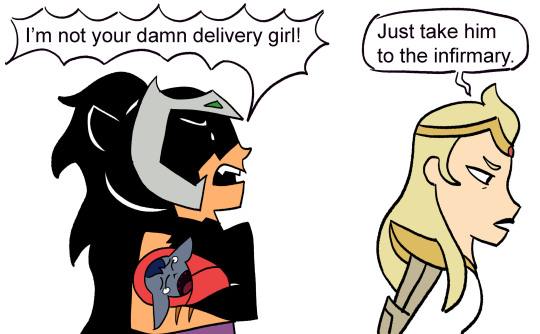

(Baby!RS!Hordak is supposed to resemble canon!Imp, thanks to fic from/talking with @revasnaslan. More info on that is below. Also yes, RS!Adora wrapped baby!RS!Hordak in her cape. :3)

FO preferred raising/training/indoctrinating the Prim-Al clone vessels from infancy, thinking this would give them greater control. They also thought it would make Prim-Al feel even more connected to organics and avoid sympathizing with any rogue AI like Light Hope.

RS!Adora finds the alien baby stranded on Etheria due to a wayward portal (like her situation), and she names him “Hordak” based on the little data she gets from the wrecked escape pod she finds him in. The data had only been text that read “Predecessor: Kadroh,” and she just reversed that name for the boy. RS!Adora names him as part of his paperwork, intending to have him sent to the infirmary with the other orphans, she can’t spend anymore time on him.

RS!Adora fought the Prim-Al before Hordak, but never knew his name was Kadroh. She doesn’t immediately see a resemblance between Hordak and Prim-Al because Hordak is a baby and she’s never really thought about Prim-Al being an organic infant before. Another significant thing is that like in @revasnaslan ‘s Where One Fell-verse fic, infants/children of Hordak’s species start completely blue, and then their faces turn white as they mature; also as @revasnaslan pointed out to me, there’s Imp, baby/child-like clone of Hordak without a white face. So RS!Adora slowly starts seeing the resemblance between Hordak and Prim-Al as Hordak’s growing up and his face starts turning white, and she honestly starts internally freaking out because by this point, between having to provide him medical assistance for his defect and having to spend more time with him than intended and watching him grow up more closely than she planned, RS!Adora is attached enough that the implications of Hordak somehow being the latest Prim-Al is distressing for her and provides a serious conflict with her loyalty to RS!Light Hope...

(Also just feel like saying that while I’m brainstorming that RS!Adora is kind of an android that’s been around for a while/like 1000+ years, I’m more in the camp that thinks that canon Hordak is actually quite young/not centuries old, even though he might have the potential for that/he can get that old later.)

There are more details on how baby RS!Hordak ends up on Etheria and the unique situation behind his birth, but that’s for another text post or fic.

RS!Adora passes herself off as an organic (even a native) while on Etheria. One metal arm is left exposed due to a minor glitch there that messes up the regen protocol for her synthetic skin; she pretends it’s just armor mainly for aesthetic/ceremonial purposes. But this is equivalent to a superficial scar, and it does not hinder or cause RS!Adora any great pain. Before Etheria she was considered one of RS!Light Hope’s perfect androids, and a random portal just plucked her from routine combat duty. (Light Hope didn’t really notice; any missing She-Ra units were assumed to be casualties of battle, and she had plenty more She-Ra units to replace any losses.)

RS!Catra is a commander in RS!Adora’s Etherian Alliance. RS!Adora and RS!Catra have grown estranged while nominally on the same side. (I’ve been brainstorming RS!Adora/RS!Scorpia down the line after quite a few things go down.)

RS!Catra learned magic in Mystacor and RS!Light Spinner was her most influential mentor. RS!Catra’s specialty was transforming into a large predatory feline and other spells to strengthen her body. (I just keep getting more intrigued by original ‘80s Catra.)

When RS!Light Spinner roped RS!Catra into helping her with the Spell of Obtainment, things turned disastrous. The spell backfire warped RS!Catra, scarring her with a shadowy substance and granting her new shadow-like powers that made her vastly stronger, but the abrupt and traumatic change wrought by magic led to an initial period of insatiability and loss of control that resulted in RS!Catra transforming into an even larger, shadow-constructed feline that killed/devoured Light Spinner and other sorcerers investigating the commotion. RS!Catra flees Mystacor after this and eventually gains control over her new power, but grows more corrupt with it too, and is also left with a new hunger. Years later RS!Catra throws her lot in with the Alliance of monarchs and RS!Adora to solidify/take control of Etheria. (At the moment there’s tentatively another complicating factor with the Spell of Obtainment in this AU, but gonna leave that for another post or fic while I spend more time privately brainstorming it first.)

(Also RS!Catra’s design is very much based on her S3 finale corrupted form because I thought that was neat and that it could work in this AU. I also liked the idea of just using shadow magic to wrap around her and transform her into a large predatory shadow feline as a callback of her original ‘80s incarnation.)

Though RS!Adora is at the head of the Etherian Alliance with RS!Catra as her commander and essentially right hand, most of its high command is made of princesses and other monarchs/nobles who wished to tighten their control over Etheria. However, the Scorpion kingdom, Bright Moon, and Dryl resisted this agenda, and the Alliance considered them enemies and part of the rebels.

RS!Catra actually does just drop RS!Hordak off at the infirmary with the other orphans, complying with RS!Adora’s orders. Despite sensing some strong magic from RS!Hordak, RS!Catra’s content to leave him with the other orphans and just keep an eye on him for now.

(The magic RS!Catra’s sensing from RS!Hordak is something that can only be really triggered once he has the Sword of Protection.)

But when Hordak’s around four years old, his body starts breaking down/his defect becomes apparent. Many in the Alliance give up on the boy’s use as a soldier-in-training (or even use as a servant) and consider casting him out, despite RS!Adora’s insistence that they have enough resources to spare on providing the boy with ongoing medical assistance. (RS!Adora is motivated by a variety of things, including honoring Light Hope’s precept that all creatures have a place under her reign (until she orders otherwise); and at this point RS!Adora still feels some connection to her fellow portal traveler stranded on Etheria and feels compelled to try to help in this situation.) It’s then that RS!Catra steps in and takes in RS!Hordak as her ward. She still thinks he has use (she can still sense great magic from him) and sees this as an opportunity to position herself as the boy’s “savior” and really secure his loyalty.

Though the relationship between RS!Adora and RS!Catra is gradually deteriorating, the nature of RS!Catra’s true motives for taking in RS!Hordak is essentially lost on RS!Adora. While largely everyone in the Alliance had spurned the idea of keeping RS!Hordak around any longer now that he was defective--something RS!Adora found rather discouraging--RS!Catra’s the only one other than RS!Adora to express some interest in the boy. In the face of that much rejection, RS!Adora thinks that if RS!Catra wants to take RS!Hordak as her ward, she should have him.

RS!Adora constructs RS!Hordak’s first set of assistive armor. This eventually includes surgery and giving him ports for a closer/better connection to the armor. RS!Adora continues to treat RS!Hordak and maintain his armor, and helps educate him on how it works when he expresses interest in it and science/technology in general.

RS!Catra is not a good adoptive mother to RS!Hordak. She trains him brutally, pushes him as far as his defect will allow, telling him he needs to work harder to make up for his defect and keep up with everyone else. Her harsh words encourage his self-loathing, and she does aim to break him down to keep him compliant. She’s basically partly swapped with Shadow Weaver in this AU (partly since RS!Light Spinner isn’t really swapped, she’s partially in a “what if she was really on the wrong end of the Spell of Obtainment and was killed by its backfire like those Mystacor sorcerers were,” and also “what if Catra was her student at Mystacor instead of Micah.”)

For a long time RS!Hordak believes he deserves RS!Catra’s harsh treatment, and is afraid that she’ll cast him out if he’s not good enough. He’s aware that there’s no one else in the Alliance that would really take him in. He worries that RS!Adora would just withdraw her mercy and assistance if she realized how weak he really was, so he often tries to hide as much of that as he can from her, including signs of RS!Catra’s abusive treatment. RS!Catra sometimes softens with RS!Hordak--for example, she taught him how to drive a skiff and those were calm lessons, with RS!Catra less demanding and less harsh than when she trains him in combat--but she does not provide him with consistent care and continues to emotionally/verbally/mentally/physically abuse him.

(Above: Definitely referenced a screenshot from the show. Not pictured: Probably RS!Prime losing his shit immediately after this and cursing RS!Catra out and maybe breaking out a recording of one of RS!Adora’s tongue-lashings to unsettle her.)

RS!Catra is furious when RS!Hordak finally runs away in his teens. Her relationship with him has become somewhat less business and more dangerously personal; she has developed a twisted affection for him as her adopted son, and that makes her reactions even more volatile and harsh when he runs away. RS!Catra does not react well to RS!Hordak’s attempts to escape her.

(When RS!Hordak leaves the Etherian Alliance, he’s a little younger than canon!Adora when she leaves the Etherian Horde due to some reasons that’ll be saved for another text post or fic.)

RS!Hordak isn’t used to getting encouragement from an authority figure/older adult, it always startles him whenever it happens.

(Playing around with role swap AU--also felt like having RS!AI Prime be softer than both canon!Light Hope and canon!Horde Prime, and that’s included him being more supportive/encouraging and even more snarky/playful as another sketch comic indicated above [though part of his humor is just like a result of--he’s pretty old, some inhibitions have just dropped over time and he’s seen quite a few things just repeat over and over, and part of his response to that is to sometimes act more flippant].)

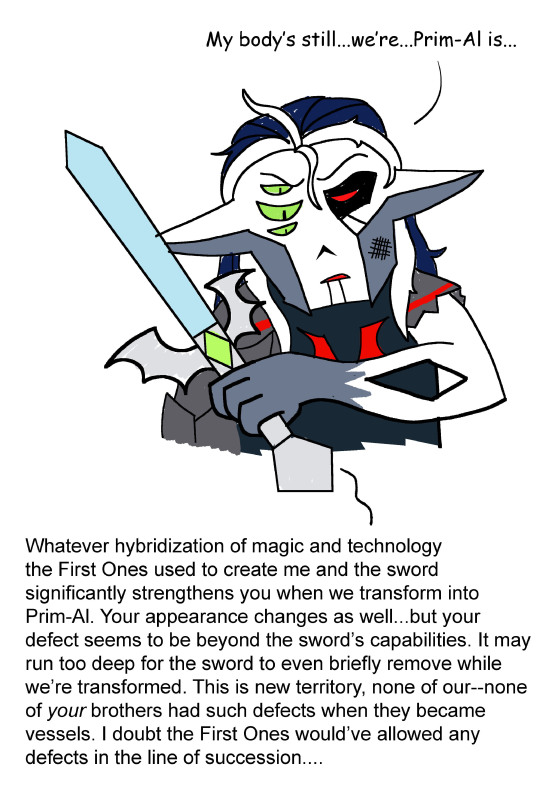

While previous Prim-Al have had some slight variations in appearance depending on the individual clone vessel’s clothing/scars/etc., Hordak’s Prim-Al transformation is the most drastically different. All of his older clone-brothers have had white hair and yellow eyes, and so their Prim-Al transformations have had long white hair and one yellow eye, while the rest turned green and gained visible pupils. Hordak has blue hair and red eyes, and so his Prim-Al transformation reflects that more--the red eye stays, and Prim-Al now has blue hair with a few streaks of white. He has clothes with a primary color scheme of black-and-red instead of black-and-white. Hordak’s Prim-Al is slightly shorter than previous Prim-Al. Hordak’s Prim-Al has more armor, since they shield his defect--which Prim-Al now has since Hordak has it. Due to this, Hordak’s Prim-Al, while gaining a significant boost in power/etc., is typically not as strong as his brothers’ Prim-Al transformations. (However, Hordak’s determination and tolerance for pain is regularly equal to his older brothers’ own determination and tolerance for pain.)

Though the defect remains, the use of AI Prime to trigger the Prim-Al transformation again provides greater power. It also does have some effect on appearance and structure. A closer examination of Prim-Al should show this: Prim-Al looks more like someone recently scarred/mutilated/afflicted with a defect, rather than someone who’s grown up with it. And so, though defective, Prim-Al’s arms look less withered and retain more muscle, and generally look better than Hordak’s usual arms. (And again, they still have a magitech boost going on.)

While FO did program AI Prime to have some regard for the clone vessels, he started caring more than they had planned. AI Prime grew to genuinely care for every clone vessel for Prim-Al, and saw them more as brothers. This now includes Hordak. And though he values his brothers and means well, AI Prime’s cynicism and (remnant) programming can sometimes get in the way of his attempts to help. His own deep-seated trauma can be a factor too.

With every new clone, AI Prime initially tries to distance himself to avoid further pain, because he grieves the loss of every clone--but he ultimately always admits to seeing them as brothers. (With his long life and the FO and Light Hope and other external factors trapping him in this cycle, AI Prime somewhat copes by comparing the whole thing to the passing of seasons. He’ll be passed down to a new clone-brother, he’ll try to resist caring about the clone-brother, he’ll grow to care about the clone-brother anyway, clone-brother dies, he’s alone until the next clone-brother comes, and then the whole thing starts again.)

Though AI Prime is a digital clone of Subject A’s mind, he doesn’t have complete access to his mental template’s memories due to FO intervention. The FO also did not tell AI Prime everything.

Yep the LUVD crystal is there, RS!Entrapta should be another sketch post or fic. She’s gone from like the oldest princess to the youngest princess in this AU, and is around the same age as RS!Hordak.

Thanks for checking this out, hope you enjoyed this AU! Hope to have more about this up later.

Forgot to add: Yep RS!Kadroh is that Kadroh, he’s RS!Wrong Hordak in this AU.

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

congratulations wyn ! we are so very thrilled to have CLOTHO join the fray. your interpretation is both lovely and strong in its depiction of sisterly loyalty and the recognition of her responsibilities as the weaver. we can’t wait to see how she and ATROPOS witness the cursed deities. please join us with your first faceclaim choice: ABIGAIL COWEN.

☆゚*・゚ OOC INFO.

wyn, 24, she/her, cst, and I enjoy angst filled storylines

☆゚*・゚ DEITY — GENDER. AGE RANGE.

CLOTHO MOIRAI— FEMALE. 20 - 24

☆゚*・゚ MORTAL NAME. JOB/OCCUPATION. BOROUGH/NEIGHBORHOOD.

Catalina Ripley. Surgeon, Medical Records Administrator at Ridgeview Clinic. Queens, New York/Jackson Heights

☆゚*・゚ FACE-CLAIM.

abigail cowen

☆゚*・ HOW WOULD YOU PLAY THEM?

PAST the fates are an enigma in creation, origins are unknown but they are there always, ever since the titans and it’s been suspected even beyond that. Clotho is the youngest yet gives no childlike quality to her personality, she knows the workings of the world and could be considered someone with the ability of emotion manipulation given how well she reads into the people around her, laying bare and raw to the world the insides of mortals and immortals alike no matter how ugly. She weaved their thread on the tapestry of life after all. Clotho is a nurturer, sweet hearted, offering advice or a gentle touch when needed. She however is not indulgent, the decisions made even if the fates had a hand in it will be met with cold indifference or tears. She is enigmatic, eloquent, a chooser of when a person is born and when they die along with her sisters so some breaking of mentality was bound to happen. losing so many many “ children ” to death becomes harder, difficult to handle and occasionally fits of not being wholly there occur in her skull. but sisters are capable of picking up the pieces once she returns to herself.

Atropos’s word is law, she values and loves her sister to much to deter loyalties yet they all have had their quarrels they work as a trio, a unit of unshakable faith in one another.

NOW

with memories encased in a snowglobe of her mind Clotho now known as Catalina Ripley is gentler and friendly than her other half and more sound of mind. Catalina prefers to help others, to lend a helping hand without a darker motive which was why ever since she was a child the medical field called her name. she adores working at the clinic or doing outpatient tasks, it makes her warm and happy to assist those around her. just the feeling of life in people if only a little at a time is breathtaking.

on the other hand Catalina pushes herself back from certain emotions, shoves them down into a part of herself and makes certain they never are addressed. she has a problem with that, shutting down in favor of analyzing an issue and decides that going through it is too much, prefers to run away from it. sometimes she will, mechanical smiles and friendly speech are a sign that she’s still not there. still not as open as people perceive her to be.

she’s more like her “father” in that regard than she wants to admit, he could build friendships/allies but wasn’t emotionally there, could easily watch a “friend” die or what he did to the woman known as her mother in this life, play a loving spouse but not really getting close. emotionally closed off. especially when it comes to fights or arguments she’d take that, flinch or get scared but then bury her feelings and cut it out. pull back from the person as after all they were never a friend to begin with. She struggles with opening up, becomes paranoid when it comes to the care of the woman she refers to as mother in her despondent state of mind as her sire is no longer in the picture. poisoned and laid out on the glass kitchen table like a feast in their old hometown with enemies and allies ever watchful.

answer these questions:

1. would you like your character to be entering the roleplay at this stage in the plot, with or without their memories?

I would like her to have memories without, makes things interesting don’t you think?

2. are they more likely to stand with the pantheon or against it? ( if you are choosing a god they may endeavour to dismantle it for whatever reason )

stand with the pantheon, to whatever end the fates only know but not all loyalties last.

3. what is their stand on mortals?

given she is the spinner of the thread she has gentle feelings towards mortals, refers to them as her own children despite that not being the case but she does care for them immensely, weeps when they enter a hardship or dies, cheers them on when overcoming disaster. yet that does not deter her from being stern with them, to almost show near callous attitude if they overstep. clotho knows her place and knows her duty, knows that the mortals die in a cycle with her sisters’s shears echoing in her ears. so despite motherly temperament she shows signs of detachment

☆゚*・ GIVE US A SAMPLE OF YOUR WRITING!CHOOSE AT LEAST ONE OF THE FOLLOWING OPTIONS

The baby was cherubic, pinchable chubby cheeks and eyes that reminded her of endless forests, a sea of green with a wide gummy smile. a baby girl, who yet had to bare a name, a tie to this world and to the beginning of her life. “ what will you call her? “ Clotho turned her gaze from the fragile form in her arms to the mother still laying on the bed, a sheen of sweat covering her form but alive, the fates had no need to cut her thread that day but nonetheless would be in this same position again with altered task and opened shears.

Both parents remainded silent, different reasons each but she could taste them on her tongue and in the air. given the history of first borns she should have been a he, a male heir in such a time was celebrated yet clotho was not one for such a mindset. " a name please, or have you decided that our choice was wrong? " pretty smile filled with glittering feral, hungry teeth, softness from before no longer apparent. truth etched in form but the baby girl held close still didn’t cry out at the change.

Father went pale when gaze and words noticed to be directed his way, fear clouding his form and sweat soon formed on his brow as if he had been the one to give birth. he didn’t let it pass his lips the unfortunate truth of not wanting it, to ask them to take the child away and perhaps he’d forget about his choice. move on try again. they didn’t work that way however.

" I-Ilythiya, that’s her name. ”

Clotho hummed, as if the name hadn’t already designed itself in skull, crafted a life laid out on a tapestry her hands would soon take up to continue the path. “ beautiful. " light steps took her back to the mother’s side after introducing her sisters to the newly named Iilythiya. gently handing her over and patting the girls head with soft smile. " you will do wonderful things little one. ”

☆゚*・ ANYTHING ELSE?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

PRE FACE: Or How to Begin at the End - Amy Ireland

http://ah-journal.net/issues/01/pre-face-or-how-to-begin-at-the-end - As in a woven image or pattern, the course taken from discrete threads to the emergence of a represented, recognisable object or product, is a nonlinear one. Once enough threads have been put into place, a motif emerges, but it is always in terms of a retrochronic legibility, premised on a process that is necessarily primary: the construction of the hardware and the programming of the software that execute the patterns of intrication presiding over the warp and weft of the threads which form the image. The lesson—one which would fascinate Plant—that can be taken from this is that recognition, conceptual identification and negation are always secondary. In this sense, the primary process of weaving is a future coincident with the present’s past. The moment of identification and appearance always arrives behind the functioning of the process which assembles it as its object—whether this is an industrial product, a historical phenomenon, or indeed, a self. Ada Lovelace’s writings testify to an intuitive apprehension of this fundamental delay. Rebuffed from admission into the Royal Society of London because of her sex, but convinced that her pioneering work would one day be understood for what it was, she did not even bother to append her name to the Menebrea footnotes, confiding to Babbage, ‘I do not wish to proclaim who has written it’.5 In both the conscious maintenance of her anonymity and her contribution to the technologisation of the processes of production that would link computation and weaving together, Ada Lovelace conspired with the primary process immanent to all representation—invisible, patient and quietly anticipating the long term effects of her work, lagging far behind their imperceptible, perpetually futural, initiation.

Women and machines, Plant argues, have historically shared the ghostlike position of the intermediary. They are nonetheless ‘the very “possibility of mediation, transaction, transition, transference”’.6 Man’s ‘go-betweens’, the ‘anonymous editors, secretaries, copyists, and clerks’, those who

took his messages, decrypted his codes, counted his numbers, bore his children, and passed on his genetic code. They have worked as his bookkeepers and his memory banks, zones of deposit and withdrawal, promissory notes, credit and exchange, not merely servicing the social world, but underwriting reality itself. Goods and chattels. The property of man.7

Apocalypse or salvation only appear as legitimate endpoints to a subjectivity premised on integral stasis and an inherently binarising logic that is dialectally subsumed into a temporal linearity produced via a double reference to an inaccessible origin and a fear of death (united in the word ‘matrix’), both of which must be appropriated, mastered and overcome. To usurp the position of authority and channel—through obfuscation, anonymity, intelligence and cunning, the weaving of a coded message or a riddle—the course of history, via the technology of prophecy is also, in its disturbance of telos, a practice of weaving time.

‘Women have always spun, carded and weaved, albeit anonymously. Without name. In perpetuity. Everywhere yet nowhere,’ writes Plant.11 To prophesy is to complicate, pleat, loop or fold time. One is said to ‘weave’ a spell or a charm, knotting a virtual future into the obscure unfolding of the present and its written past. There is a connection, emphasised by Plant, between weaving, magic, prophecy and secrecy, who notes (quoting Mircea Eliade’s Rites and Symbols of Initiation) that, ‘The moon “spins” Time and weaves human lives. The Goddesses of Destiny are spinners.”’12 When Eliade looks at the traditional tribal ‘seclusion of pubescent girls and menstruating women, often the occasion for the spinning of both actual and fictional yarns’, she continues, ‘he detects “an occult connection between the conception of the periodical creations of the world … and the ideas of Time and Destiny, on the one hand, and on the other, nocturnal work, women’s work, which has to be performed far from the light of the sun and almost in secret’.13

As the link between the ancient, feminised labour of weaving and the dawn of accelerating computation technologies, Ada Lovelace is a cyborg, and a prophet. She is in good company. Among such figures always, significantly, feminised, trans- or poly-gendered, are the many, mad monstrosities of mythology and cultural history. These pathologised and frightful seers arrive consistently from outside and approach Read Only Memory history simultaneously from what it understands as a before and an after, the past and the future, always and at once infiltrating from beneath and from afar, like the Sphinx, Tiresias, or the Eumenides that haunt the narrative of Sophocles’ Oedipus plays. The sphinx is a cyborg or a hybrid—part woman, part eagle, part lion—who dispatches a prophecy concealed in a riddle (What goes on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three legs in the evening?) to which Oedipus, thinking he has solved it, responds with the answer ‘Man’.16 Tiresias, a transgendered prophet, figured in T.S. Eliot’s indictment of a tragic modernity, The Waste Land as ‘blind / throbbing between two lives / Old man with wrinkled female breasts’ is, according to a footnote, the poem’s ‘most important personage’.17 It is Tiresias who ‘perceives the substance of the poem’ (the seer’s role in the text emerges, interestingly, in relation to the scene concerning two feminised labourers: the secretary and the clerk), and who delivers to Oedipus, in Oedipus Rex, the terrible prophecy of patricide and incest that, precisely in trying to avoid, Oedipus unwittingly fulfils.18 The Eumenides, Erinyes or Fates, ‘daughters of the earth, of the dark!’ preside over Oedipus’ death or disappearance in the enigmatic final scene of Oedipus at Colonus in which, fated to expire in the Eumenides’ sacred grove, Oedipus vanishes, with only the king of Athens and a confused messenger looking on, the latter proclaiming as he returns from the mysterious site, ‘Oedipus is dead! But no short speech could explain what happened’, an utterance reprised moments later in the question of the Chorus, ‘What? What happened?’19 The Fates are traditionally goddesses of time and, infamously, weavers—like Ariadne who is connected with both the weaving and unweaving of the Athenian labyrinth, particularly enigmatically in Nietzsche, as Deleuze points out in Nietzsche and Philosophy, claiming that, ‘Ariadne is Nietzsche's first secret’, the double of Dionysus, who recursively completes nihilism in affirming the Dionysian affirmation.20 The etymology of ‘Sphinx’ in ancient Greek derives from the verb σφίγγω (sphíngō), meaning ‘to squeeze’ or ‘tighten up’ (Plant: ‘[K]nitting is a matter of making loops. At its simplest, it is done with a single, continuous thread, which loops around and intricates itself’) and as Robert Graves recounts in The White Goddess, ‘Sphinx means “throttler” … in Etruscan ceramic art she is usually portrayed as seizing men, or standing on their prostate figures’.21 The concept corresponding to fate in Anglo-Saxon culture is ‘wyrd’ (Shakespeare renders the Greek Fates as the—again, transgendered—Wyrd Sisters of Macbeth), its Norse cognate is Urðr, connected to the Norns, or weaving female deities who control the destinies of men, and both words are derived from the root wert, ‘to turn’, ‘to spin’ or ‘to wind’.

What is it about this fearful link between women, weaving, and temporal power that transforms them into such sick and monstrous creatures in the collective imagination?22 Is it the fact that they are always either partial or multiple—‘at least two’—and thereby intractable to the rules of identity, straddling both sides of being, the transcendental and its objects?23 Or that they index—for the identity that comes to reflect upon them—a primary alienation, from the 'matrix', matter or ‘mother’ that begets it? Representation is always in the thrall of something monstrous it cannot perceive. For Oedipus, for Babbage and his colleagues, for those who speak the language of history, the unrepresentable arrives first, but also last. These threshold beings of the future and the past, presiding over the fragile threads integrating life and death inhabit both edges of time and enfold everything within their trap, secreted in the present. They are at once the secret ‘origin’ of an obscure—because nonlinear—production, and the prophetesses of the ‘end'. ‘There are only two answers to the question “which comes first” and both of them are female,’ writes Plant, 'the male element is simply an offshoot from a female loop’.24 Zeros + Ones itself closes with the casting of a prophecy. Plant writes of the processes she has been describing that they are ‘a code for the numbers to come’.25

En "The Infra-World", un pequeño tratado sobre lo imperceptible en el arte y la cultura, François J. Bonnet resalta un raro fragmento en prosa titulado ‘Heracles 2 or The Hydra,’ encontrado en la obra de Heiner Müller de 1972, "Cement".

‘Heracles 2 or The Hydra’ narra las vicisitudes de su protagonista, guerrero y masculino, Heracles, a medida que se adentra más y más en una jungla desorientadora en busca de una bestia mítica y feminizada que habrá de confrontar y matar en batalla, la Hidra. Mientras persigue al animal que cree estar cazando, siguiendo un rastro de sangre, [...] el abundante follaje de la retorcida vegetación le impide ver el cielo, su única fuente para la navegación temporal, y se encuentra con repeticiones de configuraciones de ramas particulares que alteran y distorsionan ya por completo su impresión de estar avanzando en el espacio. Llevado por un sentimiento de creciente desesperación, Heracles acelera su paso pero no puede distinguir si camina más rápido o más despacio que antes. Peor aún, la jungla parece estar animada por algún tipo extraño de consciencia y él comienza a creer que está poniéndole a prueba. Se olvida de su nombre y comienza a disociarse de su propio sentido de auto-consciencia y de su sentido de integridad corporal.

A medida que el espacio de la jungla cambia a su alrededor "solo él, el innombrable, se había mantenido igual en su largo y costoso camino a la batalla. ¿O era aquello que caminaba sobre sus piernas en el cada vez más rápido suelo danzante también algo diferente a lo que él era? Todavía estaba pensando en ello, cuando la jungla, una vez más, lo atrapó".

[...] Lentamente, lo que queda de Heracles, se da cuenta de que el rastro de sangre que ha estado siguiendo es la suya propia, y que la bestia mítica que creía estar cazando no es otra que la jungla misma:

"No avanzó más, la jungla le seguía el ritmo… y él entendió, con creciente pánico: la jungla era la Hidra, hacía tiempo que la jungla que creía estar atravesando era la bestia, era quien le llevaba en el ritmo de sus pasos, las ondas del suelo eran su jadeo y el viento su respiración, el rastro que había seguido era el de su propia sangre, de la que la selva, que era la bestia, se llevaba buena parte (¿cuánta sangre tiene un ser humano?); y también entendió que siempre lo había sabido, aunque no pudiese nombrarlo".

[...] Mientras él intenta combatirla, se da cuenta de que los golpes se vuelven hacia él, en una confusión entre usuario y herramienta (la separación que permitía su maestría), la compostura y el control se desangran entre los restos en descomposición del suelo nauseabundo de la jungla. [...] Heracles se ha encontrado con la forma del secreto

1 note

·

View note

Text

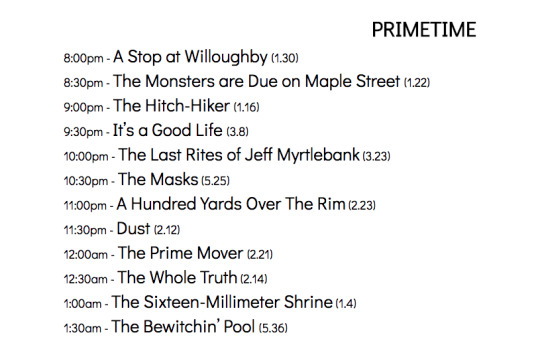

24-Hours in The Twilight Zone

When I learned that a certain cable network isn’t doing their annual Twilight Zone marathon this year...

I decided to plan out a 24-hour block of Twilight Zone episodes myself. I limited myself to episodes that reflected on American life or American history to fit the holiday. (In other words, don’t come at me if your favorite episodes aren’t on this list. All of mine aren’t either!)

All episodes included are available streaming through Netflix and Amazon Prime. The full guide with episode numbers is below the jump, but here’s a Primetime preview:

Happy Viewing!

6:00am - The Shelter (3.3)

Things get ugly when a birthday party in a peaceful suburb is interrupted by a civil defense alert.

6:30am - The Old Man in the Cave (5.7)

In 1974, the survivors of nuclear apocalypse try to stay alive with the aid of a mysterious man in a cave at the outskirts of town. (Starring James Coburn & John Anderson)

7:00am - Two (3.1)

Two lone soldiers from opposing armies find one another in the shambles of main street. (Starring Charles Bronson & Elizabeth Montgomery)

7:30am - The Silence (2.25)

An cranky rich old man bets a boisterous rich young man to stay silent for an entire year. (Starring Franchot Tone)

8:00am - A Thing About Machines (2.4)

Man versus all machines. (Starring Richard Haydn)

8:30am - Static (2.20)

A nostalgic old man tunes in for a second chance. (Starring Dean Jagger)

9:00am - Young Man’s Fancy (3.34)

A newlywed isn’t ready to leave behind his childhood home to his new wife’s chagrin.

9:30am - Nightmare as a Child (1.29)

A teacher is haunted by a peculiar and demanding child.

10:00am - Walking Distance (1.5)

A stressed out ad man tries to go home again. (Starring Gig Young)

10:30am - The Big Tall Wish (1.27)

A small boy makes a big wish for his friend, a washed-up boxer, to win a fight. (Starring Ivan Dixon)

11:00am - The Mighty Casey (1.35)

The Hoboken Zephyrs bring in a ringer. (Starring Jack Warden)

11:30am - I Sing the Body Electric (3.35)

A grieving family turns to Facsimile Ltd. to fill the void in their lives. (Starring Josephine Hutchinson)

12:00pm - Mirror Image (1.21)

A woman has a ticket to start a new life in a new town, if she can ever leave the bus station. (Starring Vera Miles)

12:30pm - The After Hours (1.34)

Sometimes you just want to buy a simple, undamaged gold thimble for your mother’s birthday and then the fabric of reality begins to fray. (Starring Anne Francis)

1:00pm - The Passersby (3.4)

Around the end of the Civil War, the wife of a Confederate soldier awaits his return.

1:30pm - An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (5.22)

An adaptation of the Ambrose Bierce story. A man is executed for sabotage.

2:00pm - Back There (2.13)

A man gets the chance to test out his theories on time travel. (Starring Russell Johnson)

2:30pm - Long Live Walter Jameson (1.24)

A close colleague discovers the true reason Walter Jameson is such a good history teacher. (Starring Kevin McCarthy)

3:00pm - Still Valley (3.11)

A Confederate soldier thinks black magic might turn the tides of the Civil War. (Starring Gary Merrill & Vaughn Taylor)

3:30pm - The 7th is Made Up of Phantoms (5.10)

National Guardsmen running exercises discover the Battle of Little Bighorn is still being waged.

4:00pm - The Grave (3.7)

A hired gun visits the grave of his latest victim. (Starring Lee Marvin, Lee Van Cleef, & James Best)

4:30pm - The Hunt (3.19)

A day of hunting doesn’t go as planned for a man and his dog.

5:00pm - Black Leather Jackets (5.18)

When a bunch of motorcycle riding delinquents move in, the aftermath isn’t quite what the townspeople expect. (Starring Shelley Fabares)

5:30pm - Ring-A-Ding Girl (5.13)

A warm welcome is planned for the Ring-A-Ding girl when she returns to her hometown.

6:00pm - The Mind and the Matter (2.27)

A New Yorker fed up with people exercises his psychic abilities. (Starring Shelley Berman)

6:30pm - Hocus-Pocus and Frisby (3.30)

The town yarn spinner attracts the attention of extraterrestrial visitors. (Starring Andy Devine)

7:00pm - The Brain Center at Whipple’s (5.33)

A factory owner is on a mission to fully automate his factory. (Starring Richard Deacon)

7:30pm - The Changing of the Guard (3.37)

In the face of retirement, an elderly professor contemplates his past and future. (Starring Donald Pleasance)

Primetime!

Enjoy a six-hour block of episodes that cross the United States while you avoid your neighbors who shouldn’t be trusted with fireworks.

8:00pm - A Stop at Willoughby (1.30)

A New York ad man is overwhelmed by the stresses of modern city life and dreams of a simpler life, in a simpler place, with simpler people. (Starring James Daly)

8:30pm - The Monsters are Due on Maple Street (1.22)

A friendly suburb descends into paranoia and chaos with little motivation. (Starring Claude Akins & Jack Weston)

9:00pm - The Hitch-Hiker (1.16)

A school teacher hits a snag on a cross-country trip. (Starring Inger Stevens)

9:30pm - It’s a Good Life (3.8)

A small town (once located in middle America) is plagued by a two-eyed, two-legged, 3-foot-tall monster. (Starring Bill Mumy, Cloris Leachman, & John Larch)

10:00pm - The Last Rites of Jeff Myrtlebank (3.23)

When Jeff Myrtlebank wakes up at his own funeral, he causes quite a stir. (Starring James Best & Sherry Jackson)

10:30pm - The Masks (5.25)

On the night of Mardi Gras, an old man holds a strange party for his greedy, self-centered relatives. (Starring Robert Keith)

11:00pm - A Hundred Yards Over The Rim (2.23)

A father travels an impossible distance in the New Mexico desert to find help for his son. (Starring Cliff Robertson)

11:30pm - Dust (2.12)

On the day of a young man’s execution, a con man tries to charge for salvation. (Starring John Larch, Thomas Gomez, & Vladimir Sokoloff)

12:00am - The Prime Mover (2.21)

A telekinetic short-order cook gets taken for a ride by his best friend. (Starring Buddy Ebsen)

12:30am - The Whole Truth (2.14)

A cursed (or enchanted) car passes through the lot of an unscrupulous used car salesman. (Starring Jack Carson)

1:00am - The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine (1.4)

A faded film star isn’t ready to let go of her past. (Starring Ida Lupino & Martin Balsam)

1:30am - The Bewitchin’ Pool (5.36)

Two children, distressed by their parents’ troubled marriage, escape to a magic swimming hole at the bottom of their pool. (Starring Mary Badham)

2:00am - The Fugitive (3.25)

The unlikely friendship of an old man and a disabled child is even more unlikely than it seems.

2:30am - The Midnight Sun (3.10)

A painter and her landlady try to stick in out in New York City as the earth slowly closes in on the sun. (Starring Lois Nettleton)

3:00am - People Are Alike All Over (1.25)

A nervous astronaut finds life on Mars (Starring Roddy McDowall)

3:30am - Third from the Sun (1.14)

In the face of certain destruction, two men and their families launch a daring interplanetary escape. (Starring Fritz Weaver)

4:00am - Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up? (2.28)

A diner crowded in with bus passengers finds there may be a Martian in their midst.

4:30am - Mr. Garrity and the Graves (5.32)

Bringing people back from the dead ain’t all it’s cracked up to be. (Starring John Dehner)

5:00am - I am the Night - Color Me Black (5.26)

The sun doesn’t rise over a town where a man is about to be executed for killing a bigot. (Starring Michael Constantine)

5:30am - In Praise of Pip (5.1)

A lone shark gets to thinking about his life after he learns his son was wounded while serving in the army abroad. (Starring Jack Klugman & Bill Mumy)

Added note: If you’re in the US and have a TV antenna, the network Decades is also running a marathon!

#Twilight Zone#the twilight zone#twilight zone marathon#fouth of july marathon#Rod Serling#marathon#netflix#amazon#amazon prime#television#tv#1960s

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

how the fashion industry operates

Our clothes have gone on a long journey before reaching the shop floor or our computer screens. Our clothes will pass through the hands of farmers, spinners, weavers, dyers, sewers and so many others that work almost invisibly in the supply chains of the fashion industry.

Take a simple T-shirt as an example, of which estimates suggest 2 billion are made and sold every year. If the T-shirt is made of cotton, its journey will have started as a seed, planted in the soil by farmers somewhere around the world such as India, Brazil or the southern United States. The raw cotton is sent to a gin where its seeds are separated from the chaff, which is like a husk or case. Then the cotton goes to a spinning facility where it is carded (separated into loose strands), combed and blended before being knitted on a loom into fabric. The fabric is then sent through a series of ‘wet processes’, which require washing, heating and treatments of various chemicals such as bleaching, printing, dyeing and fire-retardants or others that help achieve a desired softness or performance. The finished fabric then will be sent to a manufacturing facility, which will cut the fabric, sew the T-shirt, trim the threads, check for quality and pack for shipment.

What makes it so complex is that throughout and between these various stages of production, there are distributors, sourcing agents and middlemen who facilitate the buying and selling of inputs. Plus, each process will likely happen in different cities and countries, meaning a simple T-shirt would have been sent across the world several times before even reaching shoppers. Furthermore, garment manufacturing is rife with subcontracting. A fashion brand might place an order with one supplier, who in turn subcontracts the work to another facility if they need to meet a short deadline or require a special process to be done.

Major fashion brands may work with hundreds or even thousands of suppliers and garment factories at any given time. The vast majority of today’s fashion brands do not own their manufacturing and textile supplier facilities, making it challenging to monitor or control working conditions and environmental impacts across the supply chain. The fashion industry is regarded as one of today’s most globalised industries , involving complex, multinational and fragmented networks of producers, buyers, sellers and consumers all over the world.

There are other people involved in the making of a T-shirt who are not directly involved in manufacturing. The T-shirt would have needed designers who decide what it looks like, the fabric, fit, colour, print and trims. There will be people working in fashion brands that are responsible for sourcing the fabrics and finding the factories where the products are made. The T-shirt will require merchandisers, marketers and retailer workers who ensure the T-shirt is sold. There are people working in warehouses where the T-shirt will be stored and transport workers who deliver the T-shirt wherever it needs to go. There are business planners, financial managers, lawyers, investors and so many others who make the business of selling that T-shirt possible.

Today, fashion — comprising garments, textiles and footwear — is one of the world’s most labour intensive industries, directly employing at least 60 million people and likely more than double that are indirectly dependent on the sector — an estimated 80 million people in China alone . Women represent the overwhelming majority of today’s garment workers and artisans. Meanwhile, Fairtrade Foundation estimates that as many as 100 million households are directly engaged in cotton production and that as many as 300 million people work across the cotton sector in total.

In fact, as a result of fashion’s growing importance to the global economy, the apparel and footwear market was worth over $1.7 trillion in 2019 according to Euromonitor. Clothing manufacturing and textile production has a very long industrial history, credited with kickstarting modern industrialisation in developing economies since the 18th and 19th centuries and built from systems of exploitation and oppression from very early on, where black slaves were used to harvest cotton in the American South and poor, working-class and often migrant women and children fuelled the growth of newly mechanised mills and factories across Britain.

What’s markedly different today about the fashion industry is the scale and speed at which it operates. Factories around the world are continuously being pushed to deliver ever-larger quantities of clothing faster and cheaper. As a result, factories routinely make employees work extra hours, often without overtime pay or other benefits in return. The pressure on factories to deliver is so intense that workers are often subjected to intimidation, harassment, coercion and violence, and may even be restricted from taking short breaks to the toilet. The people who make our clothes are very unlikely to be paid fairly through this process. The same systems of oppression and exploitation we saw fuel the industrialisation of clothing still exist in today’s fashion industry. This is the often-grim reality that it takes to deliver our desire for ‘choice’ when we’re out shopping.

0 notes

Text

The last two paragraphs are very much my own feelings on the matter. Perhaps my "favorite" is the Scorpion kingdom, since wee mainly have friendahip-loving, assumes-the-best+grew-up-on-propaganda Scorpia and Light Spinner/Shadow Weaver qho is...well, morally grey at the best of times) on what happened. Frosta's, and Perfuma's, and other characters' parents are another big one. There's these subtle little gaps that are easily filled in with" Evil Hordak Did It" and not really even realizing this isn't actually a solid piece of canon. Then there's all the fun #Very Serious War Drama shenanigans and double-standards.

But then, I also love me some "nothing unites people like a common enemy" and Us vs Them othering going on. It's certainly possible Etheria was in perfectly balanced harmony up until Hordak rolled in (and how did that portal happen in the first place...?), but that doesn't suit this series' deep and complex exploration of abuse cycles and gray-and-gray morality so well. Add in the Fire Princess comic and, well...

Yeah, no, seriously, though: is Hordak, or the Horde, killing Frosta’s parents an actual canonical thing?

I don’t remember them ever being mentioned… did I miss something?

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Cloth fibers could be dyed at several points during production (though again, note above that dyeing was far more common for wool than for linen). Assuming wool was scoured after shearing, it could be dyed at that point (thus the phrase ‘dyed in the wool’) though unscoured wool will not generally take a dye because the natural oils of the wool will prevent the dye from setting into the cloth. Alternately, wool might be spun and then dyed either as thread or as finished woven cloth. In the early modern period, undyed woven fabrics fit for dying were called ‘whites’ and might either be dyed locally or in some cases shipped significant distances to be dyed elsewhere (in no small part because, as we’ll see, the availability of dye colors was regionally dependent).

Today, we are used to the effectively infinite range of colors offered by synthetic dyes, but for pre-modern dye-workers, they were largely restricted to colors that could be produced from locally available or imported dyestuffs. If you wanted a given color of fabric, you needed to be able to find something in the natural world which, when broken down could give you a chemical pigment that you could transfer to your fabric in a durable way. That put real limits on the colors which could be dyed and the availability of those colors.

Some colors simply couldn’t be produced this way – a good example were golden or metallic colors. If something in a dress was to be truly golden (and not merely yellow), the only way to do that prior to synthetic dyes and paints was to use actual gold, weaving small strands of ultra-thin gold wire into the cloth or embroidering designs with it. Needless to say, that was something only done by the very wealthy. Alternately, if the dye for a given hue or color came from something rare or foreign or difficult to process (for instance, in all three cases, Tyrian or royal purple, which came from the murex sea snails – if you have ever wondered why no country has purple as a national color this is why, before synthetic dyes, coloring your flags and uniforms purple would have been bonkers expensive), then it was going to be expensive and rare and there just wasn’t much you could do about that.

What dyes were available thus varied based on where you were and how much you could afford to import. Determining ancient dye availability is often tricky, since fabric so rarely survives, but we know that the Romans prized a wide range of colors; Pliny gives us some clues as to some of the more expensive dyes in his Natural History (such as saffron for a rich yellow), along with more common colors like blue (from woad), red (from madder), brown (from walnuts), and a cheaper yellow from weld. Similar sets of dyes were available in the Middle Ages, J.S. Lee notes the principal dyestuffs in use in England were woad (blue), madder (red), weld (yellow), ‘grain’ red (scarlet, this is kermes dye), cinnabar (vermillion), saffron (yellow) and various other vegetable and fruit dies (op. cit. 62). Many of these were imported; madder and weld from Germany, France and the Baltic, kermes and woad from the Mediterranean, Cinnabar from the Red Sea area. Madder, weld and woad in particular were the cheapest and most common dyes and served as the foundation for clothing color in the ancient and medieval Mediterranean (which is, consequently, why colors that can be produced by those dyes, or by mixing them, are so common in medieval artwork depicting clothing).

Eventually (‘true’) indigo blue dye came all the way from India (it was known to the Greeks and the Romans) but because of its imported nature it was an expensive luxury product in Europe prior to European colonial expansion. Indigo is a particularly good example, however, of how a dye (and its associated color, the deep blue) could be relatively inexpensive and available in one place and a rare luxury good used as a status symbol in others. While the dyes available were somewhat restricted, dyers could of course combine pigments to get composite colors, giving a fairly wide range of colors, assuming one had the money for the pigments...

The actual dying process varied based on the pigment being used and there were likely local craft differences as well. Still the process could be complex, with dyestuffs often needing to be ground down or broken up and then often heated (sometimes boiled) in order to get the pigments ready before the cloth would be immersed in the dye.

...Other dyes might require a mordant, a fixing agent which enabled the pigment to set on the fibers of the fabric. Alum was often used; in the Middle Ages it was sourced from Asia Minor and so needed to reach Europe via Mediterranean trade (although Italian sources of alum were found in 1462; it was only produced domestically in England in the 17th century and after). In other cases, as with the use of dyes produced from wood, tannic acid might be used as the mordant. Each dye had its own unique preparation process to produce the dye; some involved boiling, others fermenting, some grinding down the products and so on. Dyers needed access to quite a lot of water, both for the processes of making dye, but also to discharge the various effluent from the process – spent dye mixtures and waste water. Once the dye was made, the fibers, which might be unspun wool, spun wool thread or woven wool cloth, were immersed in the dye and then agitated; the agitation was done with a ‘dyer’s posser’ and introducing or removing the cloth was done with tongs.

...Now it is necessary to caveat this upfront: in terms of raw amounts of cloth produced, household textile production is likely to have outstripped commercial textile production until the start of the industrial revolution, so while commercial textile production is more visible to us (in part because rich businesses tend to leave records and their owners tend to be the sort of people to be literate and write things like wills which we can read) they weren’t the majority of production. So while clothiers and cloth merchants and professional weavers often get more attention in the sources (and consequently may get more attention in some modern treatments) they were likely a minority of cloth workers and cloth production prior to the early modern period.

At the same time, it is clearly wrong to think of the household production chain as being completely divorced from the commercial production chain; the two were clearly intermingled. Fullers and dyers seem to have represented a point where the two production systems converged; fulling and dying were difficult to do at household scale and required special skills and so it seems that even a household producing its own textiles would have a use for the fuller and the dyer to finish those clothes (because, again, people liked to look nice). Moreover, as we’ve discussed already, commercial clothiers often sourced the spinning and weaving they needed through the putting out system, paying domestic spinners and weavers (mainly women) on a wage or piece-work basis (that is, per-unit of thread or fabric).

...But of course there were also purely commercial workers making cloth, including elements of production that couldn’t be brought into the household (like fulling and dyeing) but also producers who worked primarily for the market. The emergence of large-scale textile production for markets – what we might term commercial production – seems closely connected to the rise of large cities, presumably because those cities contained both elites who might want to buy more (or finer) fabrics than their household could produce as well as poorer workers whose households (which might just be themselves) lacked the ability to produce textiles at all. Long distance trade was also clearly a factor that drove the emergence of large-scale cloth production; wool products were major exports as early as third millennium BC Summer (on this, note several of the chapters in C. Breniquet and C. Michel, op. cit.)

In both cases, we can see that dyers tend to be rather more highly paid than other textile workers, while second place goes to fullers (in the second chart, note that fulling, cleansing and finishing were all done in a fullery; it is the last task, I think, that would be done by the fuller himself (or herself) rather than paid workers or – in the Roman context – enslaved workers), with skilled professional weavers in the third place. The range of tax paid though gives a real sense of how there might be a considerable separation between the earning power of small-scale producers (or apprentices and other hired workers in a larger operation) and producers working at a larger scale (or making elite products).

Dyeworks (and fulleries in the medieval period) tended to be located just outside of urban centers, in part because of the smell (both kinds of work tend to smell quite bad). Because both dyeing and fulling made use of bad smelling mixtures, older scholars often assumed that the workers in these occupations were low status individuals and looked down upon. And while it is true that there does seem to have been some sense that these places were not terribly sanitary, more recent scholarship tends to show little evidence that the people who worked there – particularly the skilled, professional dyers and fullers – were low-status themselves.

In terms of the social position of cloth-makers, one indicator we can look to is professional associations and guilds. In the Roman world, professional associations (collegia) of fullers seem to have been quite common and Miko Flohr (op. cit.) argues persuasively that Roman fullers were respectable professionals, similar to other artisans – well below the political and social elite (whose wealth was in large landholdings), but not disreputable. Fuller’s collegia could be significant politically though; Flohr notes that Roman fullers seem to have been politically active, for instance, in Pompeii’s local politics (most famously dedicating a statue of Eumachia, a local aristocratic woman, outside of the ‘building of Eumachia’ the purpose of which is still under some dispute (but perhaps a market-place for fabric?)).

...So while the landed elite will have looked down their nose as textile workers (they looked down their nose at everyone), skilled professional textile workers represented fixtures in what we might see as a lower-middle-class of sorts in pre-modern cities. Because there were so many of them (and because they were attached to cloth merchants who might be truly wealthy) they often exerted a significant political and cultural pull. Thus there is an enormous range in the status of cloth-workers, from the well-to-do dyer who might be a respected professional artisan to the poorly paid spinner working in the ‘putting out’ system in her spare time when she wasn’t making clothing for her relatively poor farming family.”

- Bret Devereaux, “Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part IVa: Dyed in the Wool.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SECTION 1THE TWO FACTORS OF A COMMODITY:

USE-VALUE AND VALUE

(THE SUBSTANCE OF VALUE AND THE MAGNITUDE OF VALUE)

The wealth of those societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails, presents itself as “an immense accumulation of commodities,”[1] its unit being a single commodity. Our investigation must therefore begin with the analysis of a commodity.