#soviet christmas music

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

some Christmas music cause tis the season

youtube

youtube

youtube

#joyful cheer#joyus whimsy#christmas time#christmas#christmas music#christmas songs#holiday music#christmas carols#xmas music#soviet christmas music#red army choir#choir#anuc7777#chestnuts roasting on an open fire#feliz navidad#jose feliciano#happy holidays#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

STRANGE SANTAS!

"Santa vs Godzilla," (Cinema Sewer Calendar, 2005)

"Santa vs Dracula," (Cinema Sewer Calendar, 2006)

"Superbrat vs Santa, (Max Fish Calendar, 1996)

"Santa vs Frankenstein," (poster for Electric Frankenstein, 2008)

"Santa vs Satan," (NYPress Gift Guide cover, 2004)

"Santa vs Freemasonry," (cover for Oddfellow Magazine, 10/28/05)

"Stoop Santa," (holiday card for The Onion, 10/2/08)

"Al Goldstein, Times Square Santa," SCREW Magazine Holiday Card, 1995"

"Metal Santa," (illustration for Seattle Met, 10/28/19)

"Soviet Superbrat vs St Nicholas," (Max Fish Calendar, 2000)

"Weird Band," (illustration for BOSTON PHOENIX, 11/7/06)

"Swingin' Santa," (cover for BRUTARIAN, 10/27/00)

#santa#holiday#christmas#comics#illustration#illustrator#screw#timessquare#freemason#masonry#satan#devil#lucifer#hammer#swinger#swinging#metal#pikeplace#seattle#soviet#revolution#SaintNicholas#music#band#godzilla#mothra#ghidorah#kaiju#dracula#frankenstein

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 4: Executed Jews

By Dara Horn, excerpted from People Love Dead Jews

ALA ZUSKIN PERELMAN AND I HAD BEEN IN TOUCH ONLINE before I finally met her in person, and I still cannot quite believe she exists. Years ago, I wrote a novel about Marc Chagall and the Yiddish-language artists whom he once knew in Russia, all of whom were eventually murdered by the Soviet regime. While researching the novel, I found myself sucked into the bizarre story of these people's exploitation and destruction: how the Soviet Union first welcomed these artists as exemplars of universal human ideals, then used them for its own purposes, and finally executed them. I named my main character after the executed Yiddish actor Benjamin Zuskin, a comic performer known for playing fools. After the book came out, I heard from Ala in an email written in halting English: "I am Benjamin Zuskin's daughter." That winter I was speaking at a literary conference in Israel, where Ala lived, and she and I arranged to meet. It was like meeting a character from a book.

My hosts had generously put me up with other writers in a beautiful stone house in Jerusalem. We were there during Hanukkah, the celebration of Jewish independence. On the first night of the holiday, I walked to Jerusalem's Old City and watched as people lit enormous Hanukkah torches at the Western Wall. I thought of my home in New Jersey, where in school growing up I sang fake English Hanukkah songs created by American music education companies at school Christmas concerts, with lyrics describing Hanukkah as being about "joy and peace and love." Joy and peace and love describe Hanukkah, a commemoration of an underdog military victory over a powerful empire, about as well as they describe the Fourth of July. I remembered challenging a chorus teacher about one such song, and being told that I was a poor sport for disliking joy and peace and love. (Imagine a "Christmas song" with lyrics celebrating Christmas, the holiday of freedom. Doesn't everyone like freedom? What pedant would reject such a song?) I sang those words in front of hundreds of people to satisfy my neighbors that my tradition was universal — meaning, just like theirs. The night before meeting Ala, I walked back to the house through the dense stone streets of the Old City's Jewish Quarter, where every home had a glass case by its door, displaying the holiday's oil lamps. It was strange to see those hundreds of glowing lights. They were like a shining announcement that this night of celebration was shared by all these strangers around me, that it was universal. The experience was so unfamiliar that I didn't know what to make of it.

The next morning, Ala knocked on the door of the stone house and sat down in its living room, with its view of the Old City. She was a small dark-haired woman whose perfect posture showed a firmness that belied her age. She looked at me and said in Hebrew, "I feel as if you knew my father, like you understood what he went through. How did you know?"

The answer to that question goes back several thousand years.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The teenage boys who participated in competitive athletics in the gymnasium in Jerusalem 2,200 years ago had their circumcisions reversed, because otherwise they wouldn't have been allowed to play. In the Hellenistic empire that had conquered Judea, sports were sacred, the entry point to being a person who mattered, the ultimate height of cool — and sports, of course, were always played in the nude. As one can imagine, ancient genital surgery of this nature was excruciating and potentially fatal. But the boys did not want to miss out.

I learned this fun fact in seventh grade, from a Hebrew school teacher who was instructing me and my pubescent classmates about the Hanukkah story — about how Hellenistic tyranny gained a foothold in ancient Judea with the help of Jews who wanted to fit in. This teacher seemed overly jazzed to talk about penises with a bunch of adolescents, and I suspected he'd made the whole thing up. At home, I decided to fact-check. I pulled a dusty old book off my parents' shelf, Volume One of Heinrich Graetz's opus History of the Jews.

In nineteenth-century academic prose, Graetz explained how the leaders of Judea demonstrated their loyalty to the occupying Hellenistic empire by building a gymnasium and recruiting teenage athletes — only to discover that "in uncovering their bodies they could immediately be recognized as Judeans. But were they to take part in the Olympian games, and expose themselves to the mockery of Greek scoffers? Even this difficulty they evaded by undergoing a painful operation, so as to disguise the fact that they were Judeans." Their Zeus-worshipping overlords were not fooled. Within a few years, the regime outlawed not only circumcision but all of Jewish religious practice, and put to death anyone who didn't comply.

Sometime after that, the Maccabees showed up. That's the part of the story we usually hear.

Those ancient Jewish teenagers were on my mind that Hanukkah when Ala came to tell me about her father's terrifying life, because I sensed that something profound united them — something that doesn't match what we're usually taught about what bigotry looks or feels like. It doesn't involve "intolerance" or "persecution," at least not at first. Instead, it looks like the Jews themselves are choosing to reject their own traditions. It is a form of weaponized shame.

Two distinct patterns of antisemitism can be identified by the Jewish holidays that celebrate triumphs over them: Purim and Hanukkah. In the Purim version of antisemitism, exemplified by the Persian genocidal decrees in the biblical Book of Esther, the goal is openly stated and unambiguous: Kill all the Jews. In the Hanukkah version of antisemitism, whose appearances range from the Spanish Inquisition to the Soviet regime, the goal is still to eliminate Jewish civilization. But in the Hanukkah version, this goal could theoretically be accomplished simply by destroying Jewish civilization, while leaving the warm, de-Jewed bodies of its former practitioners intact.

For this reason, the Hanukkah version of antisemitism often employs Jews as its agents. It requires not dead Jews but cool Jews: those willing to give up whatever specific aspect of Jewish civilization is currently uncool. Of course, Judaism has always been uncool, going back to its origins as the planet's only monotheism, featuring a bossy and unsexy invisible God. Uncoolness is pretty much Judaism's brand, which is why cool people find it so threatening — and why Jews who are willing to become cool are absolutely necessary to Hanukkah antisemitism's success. These "converted" Jews are used to demonstrate the good intentions of the regime — which of course isn't antisemitic but merely requires that its Jews publicly flush thousands of years of Jewish civilization down the toilet in exchange for the worthy prize of not being treated like dirt, or not being murdered. For a few years. Maybe.

I wish I could tell the story of Ala's father concisely, compellingly, the way everyone prefers to hear about dead Jews. I regret to say that Benjamin Zuskin wasn't minding his own business and then randomly stuffed into a gas chamber, that his thirteen-year-old daughter did not sit in a closet writing an uplifting diary about the inherent goodness of humanity, that he did not leave behind sad-but-beautiful aphorisms pondering the absence of God while conveniently letting his fellow humans off the hook. He didn't even get crucified for his beliefs. Instead, he and his fellow Soviet Jewish artists — extraordinarily intelligent, creative, talented, and empathetic adults — were played for fools, falling into a slow-motion psychological horror story brimming with suspense and twisted self-blame. They were lured into a long game of appeasing and accommodating, giving up one inch after another of who they were in order to win that grand prize of being allowed to live.

Spoiler alert: they lost.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I was in graduate school studying Yiddish literature, itself a rich vein of discussion about such impossible choices, when I became interested in Soviet Jewish artists like Ala's father. As I dug through library collections of early-twentieth-century Yiddish works, I came across a startling number of poetry books illustrated by Marc Chagall. I wondered if Chagall had known these Yiddish writers whose works he illustrated, and it turned out that he had. One of Chagall's first jobs as a young man was as an art teacher at a Jewish orphanage near Moscow, built for children orphaned by Russia's 1919-1920 civil war pogroms. This orphanage had a rather renowned faculty, populated by famous Yiddish writers who trained these traumatized children in the healing art of creativity.

It all sounded very lovely, until I noticed something else. That Chagall's art did not rely on a Jewish language — that it had, to use that insidious phrase, "universal appeal" — allowed him a chance to succeed as an artist in the West. The rest of the faculty, like Chagall, had also spent years in western Europe before the Russian revolution, but they chose to return to Russia because of the Soviet Union's policy of endorsing Yiddish as a "national Soviet language." In the 1920s and 30s, the USSR offered unprecedented material support to Yiddish culture, paying for Yiddish-language schools, theaters, publishing houses, and more, to the extent that there were Yiddish literary critics who were salaried by the Soviet government. This support led the major Yiddish novelist Dovid Bergelson to publish his landmark 1926 essay "Three Centers," about New York, Warsaw, and Moscow as centers of Yiddish-speaking culture, asking which city offered Yiddish writers the brightest prospects. His unequivocal answer was Moscow, a choice that brought him back to Russia the following year, where many other Jewish artists joined him.

But Soviet support for Jewish culture was part of a larger plan to brainwash and coerce national minorities into submitting to the Soviet regime — and for Jews, it came at a very specific price. From the beginning, the regime eliminated anything that celebrated Jewish "nationality" that didn't suit its needs. Jews were awesome, provided they weren't practicing Jewish religion, studying traditional Jewish texts, using Hebrew, or supporting Zionism. The Soviet Union thus pioneered a versatile gaslighting slogan, which it later spread through its client states in the developing world and which remains popular today: it was not antisemitic, merely anti-Zionist. (In the process of not being antisemitic and merely being anti-Zionist, the regime managed to persecute, imprison, torture, and murder thousands of Jews.) What's left of Jewish culture once you surgically remove religious practice, traditional texts, Hebrew, and Zionism? In the Soviet Empire, one answer was Yiddish, but Yiddish was also suspect for its supposedly backwards elements. Nearly 15 percent of its words came directly from biblical and rabbinic Hebrew, so Soviet Yiddish schools and publishers, under the guise of "simplifying" spelling, implemented a new and quite literally antisemitic spelling system that eliminated those words' Near Eastern roots. Another answer was "folklore" — music, visual art, theater, and other creative work reflecting Jewish life — but of course most of that cultural material was also deeply rooted in biblical and rabbinic sources, or reflected common religious practices like Jewish holidays and customs, so that was treacherous too.

No, what the regime required were Yiddish stories that showed how horrible traditional Jewish practice was, stories in which happy, enlightened Yiddish-speaking heroes rejected both religion and Zionism (which, aside from its modern political form, is also a fundamental feature of ancient Jewish texts and prayers traditionally recited at least three times daily). This de-Jewing process is clear from the repertoire of the government-sponsored Moscow State Yiddish Theater, which could only present or adapt Yiddish plays that denounced traditional Judaism as backward, bourgeois, corrupt, or even more explicitly — as in the many productions involving ghosts or graveyard scenes — as dead. As its actors would be, soon enough.

The Soviet Union's destruction of Jewish culture commenced, in a calculated move, with Jews positioned as the destroyers. It began with the Yevsektsiya, committees of Jewish Bolsheviks whose paid government jobs from 1918 through 1930 were to persecute, imprison, and occasionally murder Jews who participated in religious or Zionist institutions — categories that included everything from synagogues to sports clubs, all of which were shut down and their leaders either exiled or "purged." This went on, of course, until the regime purged the Yevsektsiya members themselves.

The pattern repeated in the 1940s. As sordid as the Yeveksiya chapter was, I found myself more intrigued by the undoing of the Jewish Antifascist Committee, a board of prominent Soviet Jewish artists and intellectuals established by Joseph Stalin in 1942 to drum up financial support from Jews overseas for the Soviet war effort. Two of the more prominent names on the JAC's roster of talent were Solomon Mikhoels, the director of the Moscow State Yiddish Theater, and Ala's father Benjamin Zuskin, the theater's leading actor. After promoting these people during the war, Stalin decided these loyal Soviet Jews were no longer useful, and charged them all with treason. He had decided that this committee he himself created was in fact a secret Zionist cabal, designed to bring down the Soviet state. Mikhoels was murdered first, in a 1948 hit staged to look like a traffic accident. Nearly all the others — Zuskin and twelve more Jewish luminaries, including the novelist Dovid Bergelson, who had proclaimed Moscow as the center of the Yiddish future — were executed by firing squad on August 1952.

Just as the regime accused these Jewish artists and intellectuals of being too "nationalist" (read: Jewish), today's long hindsight makes it strangely tempting to read this history and accuse them of not being "nationalist" enough — that is, of being so foolishly committed to the Soviet regime that they were unable to see the writing on the wall. Many works on this subject have said as much. In Stalin's Secret Pogrom, the indispensable English translation of transcripts from the JAC "trial," Russia scholar Joshua Rubenstein concludes his lengthy introduction with the following:

As for the defendants at the trial, it is not clear what they believed about the system they each served. Their lives darkly embodied the tragedy of Soviet Jewry. A combination of revolutionary commitment and naive idealism had tied them to a system they could not renounce. Whatever doubts or misgivings they had, they kept to themselves, and served the Kremlin with the required enthusiasm. They were not dissidents. They were Jewish martyrs. They were also Soviet patriots. Stalin repaid their loyalty by destroying them.

This is completely true, and also completely unfair. The tragedy — even the term seems unjust, with its implied blaming of the victim — was not that these Soviet Jews sold their souls to the devil, though many clearly did. The tragedy was that integrity was never an option in the first place.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Ala was almost thirteen years old when her father was arrested and until that moment she was immersed in the Soviet Yiddish artistic scene. Her mother was also an actor in the Moscow State Yiddish Theater; her family lived in the same building as the murdered theater director Solomon Mikhoels, and moved in the same circles as other Jewish actors and writers. After seeing her parents perform countless times, Ala had a front-row seat to the destruction of their world. She attended Mikhoel's state funeral, heard about the arrest of the brilliant Yiddish author Der Nister from an actor friend who witnessed it from her apartment across the hall, and was present when secret police ransacked her home in conjunction with her father's arrest. In her biography, The Travels of Benjamin Zuskin, she provides for her readers what she gave me that morning in Jerusalem: an emotional recounting, with the benefit of hindsight, of what it was really like to live through the Soviet Jewish nightmare.

It's as close as we can get, anyway. Her father Benjamin Zuskin's own thoughts on the topic are available only from state interrogations extracted under unknown tortures. (One typical interrogation document from his three and a half years in the notorious Lubyanka Prison announces that the day's interrogation lasted four hours, but the transcript is only half a page long — leaving to the imagination how the interrogator and interrogatee may have spent their time together. Suffice it to say that another JAC detainee didn't make it to trial alive.) His years in prison began when he was arrested in December of 1948 in a Moscow hospital room, where he was being treated for chronic insomnia brought on by the murder of his boss and career-long acting partner, Mikhoels; the secret police strapped him to a gurney and carted him to prison in his hospital gown while he was still sedated.

But in order to truly appreciate the loss here, one needs to know what was lost — to return to the world of the great Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem, the author of Benjamin Zuskin's first role on the Yiddish stage, in a play fittingly titled It's a Lie!

Benjamin Zuskin's path to the Yiddish theater and later to the Soviet firing squad began in a shtetl comparable to those immortalized in Sholem Aleichem's work. Zuskin, a child from a traditional family who was exposed to theater only through traveling Yiddish troupes and clowning relatives, experienced that world's destruction: his native Lithuanian shtetl, Ponievezh, was among the many Jewish towns forcibly evacuated during the First World War, catapulting him and hundreds of thousands of other Jewish refugees into modernity. He landed in Penza, a city with professional Russian theater and Yiddish amateur troupes. In 1920, the Moscow State Yiddish Theater opened, and by 1921, Zuskin was starring alongside Mikhoels, the theater's leading light.

In the one acting class I have ever attended, I learned only one thing: acting isn't about pretending to be someone you aren't, but rather about emotional communication. Zuskin, who not only starred in most productions but also taught in the theater's acting school, embodied the concept. His very first audition was a one-man sketch he created, consisting of nothing more than a bumbling old tailor threading a needle — without words, costumes, or props. It became so popular that he performed it to entranced crowds for years. This physical artistry animated his every role. As one critic wrote, "Even the slightest breeze and he is already air-bound."

Zuskin specialized in playing figures like the Fool in King Lear — as his daughter puts it in her book, characters who "are supposed to make you laugh, but they have an additional dimension, and they arouse poignant reflections about the cruelty of the world." Discussing his favorite roles, Zuskin once explained that "my heart is captivated particularly by the image of the person who is derided and humiliated, but who loves life, even though he encounters obstacles placed before him through no fault of his own."

The first half of Ala's book seems to recount only triumphs. The theater's repertoire in its early years was largely adopted from classic Yiddish writers like Sholem Aleichem, I. L. Peretz, and Mendele Moykher Seforim. The book's title is drawn from Zuskin's most famous role: Senderl, the Sancho Panza figure in Mendele's Don Quixote-inspired work, Travels of Benjamin the Third, about a pair of shtetl idiots who set out for the Land of Israel and wind up walking around the block. These productions were artistically inventive, brilliantly acted, and played to packed houses both at home and on tour. Travels of Benjamin the Third, in a 1928 review typical of the play's reception, was lauded by the New York Times as "one of the most originally conceived and beautifully executed evenings in the modern theater."

One of the theater's landmark productions, I. L. Peretz's surrealist masterpiece At Night in the Old Marketplace, was first performed in 1925. The play, set in a graveyard, is a kind of carnival for the graveyard's gathered ghosts. Those who come back from the dead are misfits like drunks and prostitutes, and also specific figures from shtetl life - yeshiva idlers, synagogue beadles, and the like. Leading them all is a badkhn, or wedding jester — divided in this production into two mirror-characters played by Mikhoels and Zuskin — whose repeated chorus among the living corpses is "The dead will rise!" "Within this play there was something hidden, something with an ungraspable depth," Ala writes, and then relates how after a performance in Vienna, one theatergoer came backstage to tell the director that "the play had shaken him as something that went beyond all imagination." The theatergoer was Sigmund Freud.

As Ala traces the theater's trajectory toward doom, it becomes obvious why this performance so affected Freud. The production was a zombie story about the horrifying possibility of something supposedly dead (here, Jewish civilization) coming back to life. The play was written a generation earlier as a Romantic work, but in the Moscow production, it became a means of denigrating traditional Jewish life without mourning it. That fantasy of a culture's death as something compelling and even desirable is not merely reminiscent of Freud's death drive, but also reveals the self-destructive bargain implicit in the entire Soviet-sponsored Jewish enterprise. In her book, Ala beautifully captures this tension as she explains the badkhn's role: "He sends a double message: he denies the very existence of the vanishing shadow world, and simultaneously he mocks it, as if it really does exist."

This double message was at the heart of Benjamin Zuskin's work as a comic Soviet Yiddish actor, a position that required him to mock the traditional Jewish life he came from while also pretending that his art could exist without it. "The chance to make fun of the shtetl which has become a thing of the past charmed me," he claimed early on, but later, according to his daughter, he began to privately express misgivings. The theater's decision to stage King Lear as a way of elevating itself disturbed him, suggesting as it did that the Yiddish repertoire was inferior. His own integrity came from his deep devotion to yiddishkayt, a sense of essential and enduring Jewishness, no matter how stripped-down that identity had become. "With the sharp sense of belonging to everything Jewish, he was tormented by the theater forsaking its expression of this belonging," his daughter writes. Even so, "no, he could not allow himself to oppose the Soviet regime even in his thoughts, the regime that gave him his own theater, but 'the heart and the wit do not meet.'"

In Ala's memory, her father differed from his director, partner, and occasional rival, Mikhoels, in his complete disinterest in politics. Mikhoels was a public figure as well as performer, and his leadership of the Jewish Antifascist Committee, while no more voluntary than any public act in a totalitarian state, was a role he played with gusto, traveling to America in 1943 and speaking to thousands of American Jews to raise money for the Red Army in their battle against the Nazis. Zuskin, on the other hand, was on the JAC roster, but seems to have continued playing the fool. According to both his daughter and his trial testimony, his role in the JAC was almost identical to his role on a Moscow municipal council, limited to playing chess in the back of the room during meetings.

In Jerusalem, Ala told me that her father was "a pure soul." "He had no interest in politics, only in his art," she said, describing his acting style as both classic and contemporary, praised by critics for its timeless qualities that are still evident today in his film work. But his talent was the most nuanced and sophisticated thing about him. Offstage, he was, as she put it in Hebrew, a "tam" — a biblical term sometimes translated as fool or simpleton, but which really means an innocent. (It is the first adjective used to describe the title character in the Book of Job.) It is true that in trial transcripts, Zuskin comes out looking better than many of his co-defendants by playing dumb instead of pointing fingers. But was this ignorance, or a wise acceptance of the futility of trying to save his skin? As King Lear's Fool put it, "They'll have me whipp'd for speaking true; thou'lt have me whipp'd for holding my peace." Reflecting on her father's role as a fool named Pinia in a popular film, Ala writes in her book, "When I imagine the moment when my father heard his death sentence, I see Pinia in close-up . . . his shoulders slumped, despair in his appearance. I hear the tone that cannot be imitated in his last line in the film — and perhaps also the last line in his life? — 'I don't understand anything.'"

Yet it is clear that Zuskin deeply understood how impossible his situation was. In one of the book's more disturbing moments, Ala describes him rehearsing for one of his landmark roles, that of the comic actor Hotsmakh in Sholem Aleichem's Wandering Stars, a work whose subject is the Yiddish theater. He had played the role before, but this production was going up in the wake of Mikhoel's murder. Zuskin was already among the hunted, and he knew it. As Ala writes:

One morning — already after the murder of Mikhoels — I saw my father pacing the room and memorizing the words of Hotsmakh's role. Suddenly, in a gesture revealing a hopeless anguish, Father actually threw himself at me, hugged me, pressed me to his heart, and together with me, continued to pace the room and to memorize the words of the role. That evening I saw the performance . . . "The doctors say that I need rest, air, and the sea . . . For what . . . without the theater?" [Hotsmakh asks], he winds the scarf around his neck — as though it were a noose. For my father, I think those words of Hotsmakh were like the motif of the role and — I think — of his own life.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Describing the charges levied against Zuskin and his peers is a degrading exercise, for doing so makes it seem as though these charges are worth considering. They are not. It is at this point that Hanukkah antisemitism transformed, as it inevitably does, into Purim antisemitism. Here Ala offers what hundreds of pages of state archives can't, describing the impending horror of the noose around one's neck.

Her father stopped sleeping, began receiving anonymous threats, and saw that he was being watched. No conversation was safe. When a visitor from Poland waited near his apartment building to give him news of his older daughter Tamara (who was then living in Warsaw), Zuskin instructed the man to walk behind him while speaking to him and then to switch directions, so as to avoid notice. When the man asked Zuskin what he wanted to tell his daughter, Zuskin "approached the guest so closely that there was no space between them, and whispered in Yiddish, 'Tell her that the ground is burning beneath my feet.'" It is true that no one can know what Zuskin or any of the other defendants really believed about the Soviet system they served. It is also true — and far more devastating — that their beliefs were utterly irrelevant.

Ala and her mother were exiled to Kazakhstan after her father's arrest, and learned of his execution only when they were allowed to return to Moscow in 1955. By then, he had already been dead for three years.

In Jerusalem that morning, Ala told me, in a sudden private moment of anger and candor, that the Soviet Union's treatment of the Jews was worse than Nazi Germany's. I tried to argue, but she shut me up. Obviously the Nazi atrocities against Jews were incomparable, a fact Ala later acknowledged in a calmer mood. But over four generations, the Soviet regime forced Jews to participate in and internalize their own humiliation - and in that way, Ala suggested, they destroyed far more souls. And they never, ever, paid for it.

"They never had a Nuremberg," Ala told me that day, with a quiet fury. "They never acknowledged the evil of what they did. The Nazis were open about what they were doing, but the Soviets pretended. They lured the Jews in, they baited them with support and recognition, they used them, they tricked them, and then they killed them. It was a trap. And no one knows about it, even now. People know about the Holocaust, but not this. Even here in Israel, people don't know. How did you know?"

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

That evening I went out to the Old City again, to watch the torches being lit at the Western Wall for the second night of Hanukkah. I walked once more through the Jewish Quarter, where the oil lamps, now each bearing one additional flame, were displayed outside every home, following the tradition to publicize the Hanukkah miracle — not merely the legendary long-lasting oil, but the miracle of military and spiritual victory over a coercive empire, the freedom to be uncool, the freedom not to pretend. Somewhere nearby, deep underground, lay the ruins of the gymnasium where de-circumcised Jewish boys once performed naked before approving crowds, stripped of their integrity and left with their private pain. I thought of Benjamin Zuskin performing as the dead wedding jester, proclaiming, "The dead will rise!" and then performing again in a "superior" play, as King Lear's Fool. I thought of the ground burning beneath his feet. I thought of his daughter, Ala, now an old woman, walking through Jerusalem.

I am not a sentimental person. As I returned to the stone house that night, along the streets lit by oil lamps, I was surprised to find myself crying.

#People Love Dead Jews#Dara Horn#Soviet Jewry#Soviet antisemitism#antizionism is not antisemitism#jumblr

342 notes

·

View notes

Text

July 13, 1985 - Chrissie Mullen May and baby Louisa May, Brian May's wife and daughter, can be seen onstage during the "Live Aid" concert finale, where big stars such as George Michael, Freddie Mercury, Paul McCartney, David Bowie and Bono, sang "Do They Know it's Christmas?".

Live Aid was a multi-venue benefit concert held on Saturday 13 July 1985, as well as a music-based fundraising initiative. The original event was organised by Bob Geldof and Midge Ure to raise further funds for relief of the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia, a movement that started with the release of the successful charity single "Do They Know It's Christmas?" in December 1984. Billed as the "global jukebox", Live Aid was held simultaneously at Wembley Stadium in London, attended by about 72,000 people, and John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia, attended by 89,484 people.

On the same day, concerts inspired by the initiative were held in other countries, such as the Soviet Union, Canada, Japan, Yugoslavia, Austria, Australia, and West Germany. It was one of the largest satellite link-ups and television broadcasts of all time; an estimated audience of 1.9 billion, in 150 nations, watched the live broadcast, nearly 40 percent of the world population.

#Chrissie Mullen#Chrissie Mullen May#Chrissie May#Louisa May#Live Aid#1985#1985 Chrissie#1980s#1980s Chrissie#George Michael#Paul McCartney#Freddie Mercury#Bono#David Bowie#muse#Bob Geldof#Howard Jones

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

This song is called Shchedryk. This is a traditional Ukrainian folk arranged and staged in the classical European polyphonic choral style in Kyiv by the composer Mykola Leontovych, presented with the final edition in 1919.

In 1918 Ukraine finally gained independence between the collapse of the Russian Empire and the Soviet occupation. It was difficult to gain recognition of independence for an individual nation in a time when the world was ruled by empires. Therefore the Ukrainian government organized multi-level diplomatic missions which included a concert tour with classical and traditional Ukrainian art to show the world that Ukraine has its own culture and identity. The purpose of this mission was to counter Russian propaganda that claimed Ukraine and Ukrainian culture did not exist.

During 1919-1923 the tour with Shchedryk traveled through Europe, North and South America. American audience was impressed with this fresh exotic from an unknown country. The concerts in New York and San Francisco were praised by newspaper columnists who noted the special relationship between Ukrainians and music and the enthusiastic reaction of the audience to Shchedryk's performance.

In 1936 a Ukrainian American Peter J. Wilhousky working for NBC radio created an English adaptation of the song known today as Carol of the Bells. Shchedryk's original lyrics in Ukrainian do not mention Christmas or Jesus's birth and belong to the pre-Christian cultural tradition. The original text talks about good news and joy, mentions the birth of a domesticated animal and how to be happy with what you have. Art historians say that Shchedryk is more typical for a spring song, because the lyrics mention swallows that come only in early spring when the Ukrainian New Year began in the pre-Christian era and in general Ukrainian culture is mainly based on the cult of spring. So Shchedryk's winter vibe is the merit of the Christmas's commercial success.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sherlockian Wednesday Watchalongs: 🎅 HoHoHolmes

🎶🎄 Deck the halls with all the Sherlocks, fa la la la la, la la la la! 🎄🎶

Wednesday, December 6 Sherlock Holmes: The Blue Carbuncle (1968 TV episode) Peter Cushing finishes out his run on this series with a mystery found inside a Christmas goose.

Wednesday, December 13 The Blue Carbuncle (1979 movie) Just when you thought you'd seen all the Soviet-era musical comedy Holmes adaptations, you find out about The Other One.

Wednesday, December 20 Tales from Dickens: A Christmas Carol (1959 TV episode) You know Basil Rathbone from his portrayal of one of the most famous characters in British literature, but now you'll see him… do that. Except with Scrooge this time.

December 24–26: 🎁 Bonus Holmes for the Holidays watchalong marathon! 🎁

Wednesday, December 27 The Great Mouse Detective (1986 movie) It's time for our annual visit with Basil of Baker Street.

Here’s the deal: Like Sherlock Holmes? You’re welcome to join us in The Giant Chat of Sumatra’s #giantchat text channel to watch and discuss with us. Just find a copy of the episode or movie we’re watching, and come make some goofy internet friends.

Keep an eye on my #the giant chat of sumatra tag and the calendar for updates on future chat events. We'll be having more special bonus events at the end of the year!

#the giant chat of sumatra#sherlock#bbc sherlock#sherlock holmes#sherlock holmes 1965#the blue carbuncle 1979#a christmas carol 1959#the great mouse detective#watchalong#holiday special#finalproblem.tumblr.com/chat

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

last night we watched this fun hour-long film that is about fantastical events in a small village on Christmas eve, and I highly recommend it. fun editing style, lots of sequences of music and action that are almost like a ballet. tonight we are going to make salad olivier, pelmeni, etc and watch the irony of fate, because I love traditions, festivity, etc and did not grow up in that kind of family so I have to borrow my new years traditions from Intermediate Russian 1, Unit 3: Celebrations in the Soviet Union

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

my sister gave me a cheapo record player for christmas, and i'm so excited because now i can listen to all my stupid music again, including:

an album of fairground organ music from a missouri tourist trap called "gay 90s village"

a jan and dean album whose gimmick is that all the song titles are names of cities

multiple swiss and bavarian folk records

the soviet national anthem (on an lp for some reason)

a 78 i bought for the sole reason that it seemed like it would be cool to have a 78

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm gonna show you my Beatles-themed stuff collection bc why not

Firstly, the wonderful yellow submarine poster that hangs on my door

My mom got it for me :)

Some books:

A John Lennon biography in German (which I haven't gotten around to read yet, to be honest), Get Back which my dad got for me for New Year's after the series came out in 2021, and a Beatles biography which I can recommend because it has a lot of interesting information and funny stories about the Beatles.

A book of piano notes from my mom's childhood, it's a soviet edition so all the songs in there have russian translations which are quite funny to read

This book actually was the thing that properly introduced me to the Beatles (I had heard about them before that of course, but I didn't really know their music) – my mom was playing Honey Pie once and I liked the song, so I started learning it with the notes from here. Then I went and listened to the original and slowly started to listen to other songs of theirs.

A pin which I'm wearing on one of my favourite vests, it's the most recent addition to my collection actually

Vinyls!!

I've got A Hard Day's Night, Rubber Soul, A Taste of Honey and Let It Be from my grandparents, these are soviet editions and have been lying around at their house for ages. Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour were gifts from my dad and Beatles For Sale was a gift from a friend of mine

And now my favourite item: this yellow submarine sweater :D

I got it for New Year's two years ago (my family is Russian/Belarusian, so we get presents on New Year instead of Christmas)

That's all, hope you enjoyed this :)

#you can tell I've been a beatlemaniac for a long time#well it was the first music fandom I've entered so#misha talks#the beatles#Spotify

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

wait, people actually listen to Pokemon reviews?? Usually I just get the games for Christmas or my birthday. I just form my own opinion and don’t share it online 💀

the Pokemon fandom is quite toxic to!!! That’s why I don’t really interact with it much. It’s pretty bad. This is coming from a long term Pokemon fan. Usually I just buy the games for fun stuff and just try to look at the bright side.

Also what’s your favorite music bands?? Mine is: Kino (Soviet band), Oasis, The Cure, Twin Tribes, Molchat Doma, The Sisters of Mercy, Bauhaus and many more!! :D

ooooh i have sooo many favourite bands are you sure u wanna hear them all?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Certain rituals and traditions that are fixtures in the annals of your life simply mean something by virtue of their existence. For me, the traditions that hold the most weight almost always have to do with food.

My family came to this country from the former Soviet Union in the late ’70s. New Year’s was the biggest holiday of the year in the U.S.S.R. for all people, including Jews. For post-Soviet Jewish immigrant families around the world, New Year’s, or Novy God, is still one of the most important holidays of the year. Traditionally, there’s feasting, dancing, music, the gathering of family and friends, and often you’ll find a New Year’s tree, too. That tree is not to be confused with the exactly identical-appearing Christmas tree. Yes, even my grandparents had a New Year’s tree during my childhood. Like many other Soviet Jews they didn’t know it as anything other than an entirely secular joyous winter tradition. I remember having to keep the fact that we had a tree a secret. This was before the term “Hanukkah Bush” became a thing, and I knew enough from attending Jewish day school to recognize that Jews having a tree in their home might be taboo.

The tree wasn’t ever as important as the food we ate. My grandmother loved to make a four-course meal, and the first course featured a variety of salads, smoked fish and red caviar. I can’t remember a first course New Year’s feast without salad Olivier on our table. salad Olivier, or Russian potato salad, is an extremely popular Russian dish, and it is nearly synonymous with Novy God. You’ll be hard pressed to find a Soviet-style New Year’s celebration without it. While it’s considered celebratory, the salad is made with humble ingredients: boiled potatoes and carrots, peas, pickles, hard-boiled egg, mayonnaise and often some kind of meat like a Mortadella or smoked ham.

The salad was first prepared by Lucien Olivier in the 1860s. Olivier was the French chef of a famous restaurant in Moscow called The Hermitage; hence the very French name for this now-popular Russian salad. Also, Russians were obsessed with French culture at that time. Salad Olivier was an immediate hit, and it became the restaurant’s signature dish. Originally, it was made with crayfish, capers and even grouse. After the revolution, simpler and easier-to-come-by ingredients were more commonly adapted into the recipe. These ingredients are also all conveniently available in the dead of winter.

The popularity of the salad spread beyond Russia to Eastern Europe, the Balkans and even to Iran and Pakistan. In fact, in our family we call this dish salad de boeuf (pronounced as “de beff”), which is what this salad is inexplicably called in Romania and Western Ukraine. Boeuf means “beef” in French, and this salad contains no beef at all.

In each geographic locale, the salad might differ slightly. Sometimes the potatoes are mashed instead of cubed, or there’s shredded chicken instead of smoked meat, or sometimes there’s no meat at all, as was the custom in our family. What makes this type of potato salad uniquely a salad Olivier is the presence of potatoes combined with carrots, peas, pickles and hard-boiled eggs. Everything should be chopped to roughly the same size. The appeal of something seemingly odd and vaguely average is ultimately mysterious, but the combination of hearty firm potatoes, sweet cooked carrots, crisp pickles, earthy peas and silky eggs in a creamy tangy dressing just works. The ingredients meld together, each losing its own particular edge to combine to make a complete range of salty, sweet, tangy, satisfying tastes in each bite. I think this salad’s enduring and far-reaching popularity proves that it’s eaten for more than tradition’s sake.

If you’re going to attempt to make this for the first time there are a few things to know. For one, this recipe reflects how my family likes this dish. If you’ve had this before, it might be slightly different from what you’re used to. More importantly, the quality of each ingredient matters to the overall success of the dish. I like to use Yukon Gold potatoes because they hold up well and have a pleasant rich sweetness, but you can definitely try it with your favorite potatoes. Taste the carrots before you cook them; they should be sweet and flavorful, not the dull astringent variety you sometimes find in the supermarket. The best pickles for this dish are ones that come from the refrigerator section, that still have a crunch, and are brined in salt with zero vinegar added. They’re also known as “naturally fermented” pickles. The type of mayonnaise you use is also key, and I swear by Hellmann’s/Best Foods.

While our family assimilated to American life in all kinds of ways and happily observed all of the Jewish holidays, celebrating New Year’s was an unspoken honoring of our past. My family loves America; they are proud they could come here and offer their children a better life, which included being able to be openly Jewish and free from religious persecution. And yet, there will always be a meaningful connection to their place of origin, particularly to the food they ate as children, and to a life that formed their identity. Whether we acknowledge that or not, or even fully realize it, eating salad Olivier at the new year offers that link to our past.

Notes:

You can cook the potatoes and carrots up to two days in advance, and store in the refrigerator.

This salad need to sit for 1 hour before serving, and can be made up to a day in advance.

This salad stores well for two days. You can also make this without the dressing up to three days in advance, then add the dressing before serving.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! I’m an insane Russian studies student and your posting about music that reminds you of winter as a kind of christmas music reminded me of my favorite old Soviet song in that genre: Siberian Waltz (1954) with soloist Leonid Kostritsa :) please enjoy a song that feels to me like sitting by the window with a cup of hot tea and watching the snow http://www.sovmusic.ru/m/sibveche.mp3

hi! I love that thank u for sharing!! 😁

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comfort Movie Tag

rules: post 10 of your favorite comfort movies and then tag 10 people

Tagged by : @chaoticcoffeequeen and @starstrucksnowing thank you ✨✨✨

Comfort Movies (no particular order)

1) Moulin Rouge!

2) Evita

3) Sweeney Todd (yeah, I know, but the movie rewired my synapses). It also does not escape my notice that the first movies in this category I'm thinking of are musicals. :))

4) Any Marvel movies with Thor & Loki

5) The Star Wars movies

6) Inglourious Basterds - I would list this as my favourite movie for the longest time. Seen it more times than I can count.

7) Atonement - lives were changed when this dropped

8) There's a filmed version of Hamlet starring David Tennant from 2008 that's just extraordinary.

9) Come to think of it, The Hollow Crown series the BBC did a few years ago was top notch (all 7 parts)

10) There are a few animations that have great rewatch value and are comforting to think of, like The Nightmare Before Christmas, How The Grinch Stole Christmas, The Last Unicorn, Sleeping Beauty (Disney) or The Snow Maiden (Snegurochka, 1952, Soviet animation)

Gently tagging (feel free to ignore): @moroslavklose @b-rainlet @duxbelisarius @branwendaughterofllyr @stargazing-sapphire @ladybug023 @hellshee @hellsbellschime @slayhousehightower @notbloodraven

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating Russia National Day: Festivities, Traditions and Culture

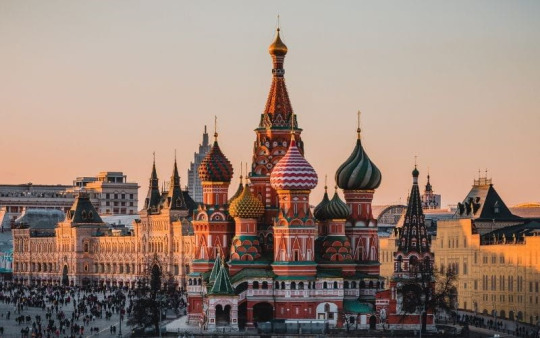

Russia is renowned for its intricate web of customs, and its holidays show a strong bond with both historical events and religious holidays. The nation provides a vast range of cultural activities from large-scale summer music festivals and winter events to Easter and Christmas celebrations. The most important of these is Russia National Day which is observed on June 12 each year. Today is the anniversary of the Russian Federation's Declaration of Sovereignty which represents the country's path toward freedom after the Soviet Union broke up in 1990.

Russia's National Day celebrations are a presentation of the nation's dynamic culture, solidarity and patriotism not just a reflection of historical pride. This is a holiday that draws in both locals and visitors with its grand parades breath-taking fireworks and exciting community events. Russia National Day Tour Packages offer the best chance for individuals looking to fully immerse themselves in this exceptional experience to view the splendour of Russian culture and take part in the national celebrations up close.

Here are the Celebrating Russia National Day: Festivities, Traditions and Culture

1. Festivities across the Nation

Russia National Day is lavishly observed in many of the nation's cities, with Moscow serving as the focal point of the celebrations. Official celebrations, featuring speeches by prominent politicians usually start the day. These are followed by military parades that highlight Russia's might and sense of patriotism. One of Moscow's most recognizable sites, Red Square, serves as the hub for festivities, which include both traditional and spectacular entertainment. The sky is illuminated with breath-taking fireworks displays as night falls, bringing people together in a festive mood.

Beyond Moscow, with distinctive regional festivals places like St. Petersburg, Novosibirsk and Vladivostok also join in the celebrations. Every community adds its own unique flair to the festivities from outdoor music and folk dances to regional exhibits and food markets. During this countrywide event both residents and visitors can enjoy the vibrant and joyous atmosphere while learning about the depth of Russian history and tradition.

2. Cultural Traditions and Russian Pride

Russia National Day is a chance for the country to consider its illustrious past and accomplishments therefore cultural pride is a big part of the festivities. Numerous communities host museum events, exhibitions and educational initiatives that highlight Russia's contributions to a variety of disciplines including science, music, literature and the arts. These gatherings give locals and guests the chance to engage with Russia's rich cultural heritage, which includes everything from the exquisite Tchaikovsky compositions to the literary writings of famous authors like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.

During this time, traditional Russian customs are also promoted. High flags are hoisted, people sing the national song together and a number of religious and cultural rights are carried out. These introspective moments serve as a reminder of the nation's perseverance and solidarity throughout its history. In this sense Russia National Day is an occasion to appreciate the ideals that have molded the country into what it is now rather than just to celebrate.

3. The Spirit of Togetherness and Patriotism

Fundamentally Russia National Day unites people from all walks of life in a celebration of solidarity and patriotism. In parks city centers and public squares, families and friends congregate to celebrate and partake in the day's festivities. Public areas are frequently turned into hive centers of activity complete with kid-friendly games, live music acts and food vendors serving traditional Russian fare. People are more likely to feel united and supportive of one another when there is a strong sense of community present during the festivities.

On this day, many Russians consider how strong and resilient their country is which is another potent way for them to display their patriotism. People can be seen enthusiastically donning national colours waving flags and taking part in events that pay tribute to their nation's history and future throughout the day. As people celebrate not only their independence but also their common identity and hopes for a bright future the celebration fosters a strong sense of connection to the country.

Conclusion:

Russia National Day is a holiday that aptly captures the pride, solidarity and cultural legacy of the nation. This celebration provides an in-depth look at Russian customs, history and patriotism from the great parades in Moscow to the lively communal events held in many localities. The celebrations highlight the nation's rich heritage while looking forward to a promising future allowing both locals and tourists to reflect on the country's incredible journey. For those who want to experience the essence of Russian culture up close this is a must-see event as the streets come alive with colour, music and happiness on this particular day.

Russia National Day Tour Packages offer a fantastic way for visitors to immerse themselves in the celebrations and enjoy the finest of this national holiday. These packages are made to put you right in the middle of all the action from seeing the famous Red Square procession to indulging in regional specialties and traditional Russian performances. A memorable celebration of a great and tenacious nation, Russia National Day offers something for everyone regardless of your interests in history, culture or just the excitement of a fantastic event.

0 notes

Text

Eurovision 2006 - Number 61 - Millenium – "Cred în steaua mea"

youtube

The history of Formația Millenium (yes, one 'n') resembles a K-pop band formed of Soviet child musician heroes. They've had different generations of members, recruited in their teens to sing, record, perform everything from rock to pop to Christmas carol compilation LPs. They rehearsed and recorded in the basements underneath Chisinau State Circus, an abandoned Soviet monument to entertainment where they would freeze in winter and boil in summer. Their leader, impresario, and mentor was Vlad Gorgos.

The first incarnation started in the late 1990s and consisted of a group of kids including Vlad's own son. That band was 'replaced' in 2003 by a new brood of teenagers and students from the Chisinau music academy. They could sing, play instruments, perform - it was a modern day musical circus production line and I truly hope the conditions had improved by then.

It's this second generation of Millenium that found themselves on the second try that TRM had a national final in 2006. I'm not entirely sure which members of the band are on stage as there were more than six of them in the band at the time, but I'm fairly certain that the woman violinist and singer is Olga Gorcinschi. Until very recently one of their members had been a certain Natalia Gordienko - but she had other plans this year...

There was a semi-final and a final on TV. They sang Cred în steaua mea (I Believe in My Star) a turbo-folk fuelled rock workout started by a man cracking a whip. An allusion to their circus based home. It's a song sung by wide-eyed youngsters dreaming of a big, bright futures. They're fit, tanned and profess their belief in love just a little bit too much.

They cruised through the semi-final and the fun, young, vibrant group appealed both to the judges on the jury, who placed them second of the thirteen songs in the final and to the watchers at home who placed them fourth. That put them on seventeen points. Unfortunately for them, the three winners tied for first place, on eighteen points. Millenium were one point away from success!

Or so it seemed. That tie proved problematic for TRM. In order to resolve it, the took the unusual step of cancelling the entire national final after it had happened and scheduling a second one at short notice. They did invite the three bands who won, but only one of them agreed to take part. A completely new slate of another four acts were also invited to join in and it was one of those new acts (including former Millenium member Natalia Gordienko) that won. Obviously there were complaints, accusations of fixing and worse, but the new result stood.

The band were so close! As you might expect for a group managed by others, this wasn't going to be their final attempt and since 2006 they've taken part in two more Moldovan finals and one Romanian one. They've also continued to perform, record and churn out music with a line-up that has increasingly stayed static. Even now their members and former members release music under the Millenium banner. Olga Gorcinschi has even released a single on their YouTube channel within the last two months.

youtube

#esc 2006#esc#eurovision#eurovision song contest#Athens#Athens 2006#Youtube#national finals#Moldova#O melodie pentru Europa 2006#Formația Millenium#Millenium#Natalia Gordienko#Olga Gorcinschi

0 notes

Text

Foo Fighters Tour In Hershey PA On July 23 2024 Unisex T Shirt

Emma Curtis Kentucky Is Worth Fighting For Shirt

Voting For The Prosecutor Not The Criminal Shirt

Limp Bizkit At Ruoff Music Center Noblesville IN On July 2024 Unisex T Shirt

Official July 23 2024 Fenway Park Boston MA Blink 182 Shirt

Forever a Brooklyn Nets fan win or lose yesterday today tomorrow forever shirt

Cincinnati In Color Shirt

We Share One Heart One Home Trump Quote Shirt

Keep Kamala And Carry On Shirt

Kash’d Out Key West Weekend August 17 2024 Key West Theater In Key West FL Unisex T Shirt

Texas Hippie Coalition Shirt

Foo Fighters Tour In Hershey PA On July 23 2024 Unisex T Shirt

You can find lists of holidays everywhere in the Foo Fighters Tour In Hershey PA On July 23 2024 Unisex T Shirt so I will tell a bit more about the days. Christmas is celebrated by the Orthodox Church on 7 January. It is a public holiday but it is not commercialized like in the west. In the Muslim calendar only Kurban Ait is celebrated. In the former Soviet Union countries New Year is celebrated with lights, trees, presents and big parties. Nauruz or the Asian New Year is celebrated in March. This is the start of spring and is a big celebration with lots of traditional foods, dances, sports etc. and a time when families get together. There are the usual political holidays, Independance Day, Constitution Day, Day if the First President etc. and some patriotic celebrations such as Defenders Fay and Victory Day commemorating the end of the Great Patriotic War (WWII).

0 notes