#so. the first and only time i played this it was for a coffeehouse gig towards the end of my first yr in uni

Text

#so. the first and only time i played this it was for a coffeehouse gig towards the end of my first yr in uni#totally fucked up mostly bc i didn't know the music but thankfully people didn't care lol#anyway the point is: it was for a group of fourth/fifth years who were weeks away from graduating#and people were crying after and i didn't get it so much but like being in that position now and not knowing what to do after graduation#and having to say goodbye to this part of my life at least in some capacity#this hits sooo different. we're all embarking on a journey to the unknown!!!#who can say if i've been changed for the better!! but because i knew you i have been changed for good!!!!!!#wicked musical#for good#jukebox

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coffeehouse Mouse

I was the Coffeehouse Mouse.

For many years when I was younger I played acoustic guitar and traveled up and down the east coast playing and singing in bars, lounges, and coffeehouses.

To be clear, a bar and a lounge are not much different. But there IS a difference. A bar is a neighborhood thing. Same clientele nearly every day.

A lounge, however (at least in my experience), is usually part of something else like a hotel or a restaurant or an airport.

Then there was the Rathskeller.

I think in Germany a Rathskeller is similar to what we would call a tavern. You know, it's a bar but, for whatever reason, it is also a meeting place and probably even a restaurant.

Kind of like social media before there WAS social media.

Robin tells me there are a LOT of taverns in Milwaukee. One day I'd like to spend some time in that town.

Colleges, at least in the northeast, had a LOT of Rathskellers. Well, they they did in those days when I was looking to make a buck with my guitar. Maybe they still do. I don't know.

And college Rathskellers were ALWAYS looking for a guy with a guitar who could sing for one night.

Did you catch those last two words? ONE NIGHT!

No residency gigs for the working musician at a college.

So, for a few years, I did a LOT of driving. I would play a college gig in Bridgeport, Connecticut one day and Baltimore, Maryland, the next. I was horrible at planning my gigs. If I was hired, I would go. It was as simple as that.

Coffeehouses were beginning to become popular in colleges at that time. This thing called "Starbucks" was getting a lot of attention on the West Coast and it was definitely influencing the schools I was being hired at.

So, Rathskellers were suddenly re-branding themselves as Coffeehouses.

Ah. Like Cinderella, I finally had a shoe that fit!

Yes. See, as a singer and a songwriter, I didn't REALLY fit in with the bar scene (I wasn't grungy enough), I didn't really fit in with the lounge scene (I wasn't Sammy Davis, Jr. or Frank Sinatra enough), and Rathskellers seemed to be searching for an identity (some were really just beer joints, others were like small cafeterias).

In fact, I remember speaking to the activities director at the University of Bridgeport and when I referred to the "Rathskeller" she informed me that they had changed their name to the Campus Coffeehouse.

Since I had a lot of time to think about stuff while driving hundreds of miles from gig to gig, I toyed with the idea of labeling myself as the "coffeehouse mouse." I'm sure the thought stemmed from the fact that the word "Rathskeller" always sounded like "Rat Cellar" to me.

The coffeehouse scene fit me well. The music that was in demand the most was soft acoustic music. Exactly what I had been playing. Think Cat Stevens, Donovan, Paul Simon, Jim Croce, Harry Chapin.

My song list had titles like, "Moonshadow," by Cat Stevens, "The Boxer," by Paul Simon, "Blossom," by James Taylor. You get the picture.

I had my song list printed out nicely. I had the songs memorized but I needed the song list. The song list told me the title of the song, the artist/writer, and the first chord.

I had my song list with me EVERYWHERE. I was always changing it and always adding to it.

But I was never adding my own songs to it.

Maybe I was shy. Maybe I was insecure. Maybe I felt the other songwriters would go over with the college students better than introducing them to something new written by me.

My song list was always on my clipboard.

Then, one day, in Philadelphia, I stopped at a Denny's before heading to my next college gig (I think it was Villanova University), and I must have left my clipboard on the roof of my car (I only know that because I found the clipboard in the Denny's parking lot after I returned from my gig).

When I got to the school, and it was time for me to play, I panicked! I can still feel the sweat as I type this. I had no play list! And, do you think I could remember ALL the songs on that list? The answer is "no." My show was an hour long. Oh man, I was so stressed.

I remember Carly Simon talking about stage fright and, while I always had a little stage fright before every gig, THAT DAY I was paralyzed with stage fright.

The school was beautiful, by the way. I remember the stage in their coffeehouse had red and blue foot lights, the stage looked like a mini Broadway set, and they even had a curtain! Wow.

And here I was with NO PLAY LIST.

One step at a time.

That's what I told myself.

Maybe if I play one song I'll remember the next, and so on.

I was waiting in the wings (Yes, they even had a BACK STAGE AREA!)

The Activities Director spoke to me for a moment, thanked me for coming, and then she went onto the stage and took the microphone.

After a few announcements, she introduced me.

Oh man.

I'm reliving it right now as I write this. I was SO NERVOUS.

There was a wooden chair waiting for me with two microphones. One for the guitar and one for my voice.

I walked to the microphones (funny, I must have had new sneakers because I remember thinking "my shoes are SO WHITE"), and I sat with my guitar in that wooden chair.

Every eye was on me.

Oh. My. Gosh.

At first I didn't play anything. I just talked. I thought, "I'll just tell them. I'll tell them I lost my play list."

I didn't talk much in my shows before that night. But talking seemed to work for me.

I got a laugh when I asked, "Do my shoes look REALLY REALLY white to you?"

I got a laugh when I said, "I think I left my song list under the maple syrup at Denny's."

Then, one of the students yelled, "Play something you wrote."

Really?

You sure?

I didn't realize they had been playing my record on the campus radio station. But they had.

And these students knew that one song.

Good thing I didn't start with that song, though. Because, as every recording artist knows, you end with your hit.

Not that I actually had a hit. But, at that time, in that place, I had an established audience. And I didn't even realize it!

So I started playing my own stuff. Since I wrote the songs I knew the stories behind them. So I talked a lot between songs.

It was working out so well.

I didn't just talk to the audience. I chatted with them. I did most of the talking but there were times when someone would ask a question or make a comment.

Unlike the hecklers that would often disrupt a set in a bar, these students were attentive, kind, and interested in everything I was doing.

At one time I said, "I'm liking this new coffeehouse thing the schools are doing. How do you like it?"

Ah. I stumbled on another trick of the trade. Ask a question.

Suddenly there was no separation between the stage and the audience. There was no "me" and "them." We were all in the same room, all part of the same experience, all enjoying each other.

That gig changed my shows completely. I began talking more, I began playing more of my own songs, I even made sure to send the schools tapes so they could play them on their campus radio stations as a way to promote my shows.

This was an important time in my life. It was a time when I discovered three things:

1. Be yourself

2. Allow others to get to know you.

3. Never wear white sneakers on a stage.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Making It In New York: Jeff Buckley

by Jim Testa

May 2, 1993

New Jersey Beat

[This interview was originally published in New Jersey Beat Magazine, 1993.]

A famous father, drop dead good looks, talent up the wazoo, a major label deal after just two years of playing gigs… Some guys have all the luck.

Jeff Buckley certainly seems to have been touched by providence, which may be why he titled his debut album ��Grace”. But life hasn’t been all lollipops and daffodils. Buckley barely knew his father, folksinger Tim Buckley, who died when Jeff was still in grammar school. Jeff Buckley came to New York with an acoustic guitar and a pile of songs he’d written in Los Angeles, and started playing every coffeehouse, open mike, cocktail lounge, and folk club he could find. Barely two years later, he was signed to Columbia Records and releasing his first record, the CD5 Live at Sin-é. Who says you can’t make it in New York? The question is, how? So we asked.

Q: Are you from New York originally? Or were you one of those guys who just showed up at the Port Authority one day carrying your suitcase and guitar?

Jeff Buckley: Well, in my case, it was more like JFK airport. But I was living in California, in Los Angeles, before I came to New York. That was 1990. But I didn’t really start gigging in New York until ’92, maybe late ’91.

Q: And that’s when you started playing at Sin-é?

Jeff: [corrects my pronunciation] Shin-AY. Right. And other places too. First Street Cafe, Cornelia Street Cafe, Bang On, Tramps, the Knitting Factory. Anything I could find, basically. Over and over and over and over again. So I don’t know what I can tell you. The only way to really make it — anywhere — is to put every bit of your being into the thing that only you can provide. The only angle is the art that you choose, that only you can provide. And to do that, you have to be quiet for a long time and find out what you bring forth. You have to know what’s in yourself — all your eccentricities, all your banalities, the full flavor of your woe and your joy. What does it look like? What does it feel like? What makes it different from everybody else’s. It’s totally subjective. You’re just given the task of bringing it up.

It’s like going up to some girl with a guitar and saying, “you are the only one, right now, who can make your music.” Right now. You don’t even know how to play the guitar. You’ll find it, you’ll find that chord, if you express your hear, now. You’ll find that small inner platinum mine, that reservoir. It’s something that’s there, you just have to dig deep and find it. But it’s something you have to do yourself. It’s not something that can be pulled out of you by any teacher, not any that I’ve ever met. None. Close friends can tell you when you’re finding. Other people who are out there doing it, they’re good to talk to. But you have to find it yourself.

Q: The thing you hear all the time from bands is “there’s no place to play in New York.” When, of course, there are lots of places to play in New York, there just aren’t a lot of places where you can play to a decent-sized audience and make any money on a regular basis.

Jeff: There are a thousand places to play in New York.

Q: Your experience would suggest that it doesn’t really matter where you play, it’s the playing itself that counts.

Jeff: That’s it exactly. You can make a very sacred place out of The Speakeasy (a decrepit old Lower East Side bar.) If you put enough heart into it. Or you an turn it into a complete circus. You can do anything you want, anything. I’ve seen it all. You can blame the sound system sometimes. If you’re a band, and the sound system sucks, there’s nothing you can do, you’re fucked. But if the sound system sucks, then you just mix yourselves on the stage, you turn up or turn down until you make it sound okay, and you use what little you have. There are always angles around technology, around managers, around people. But when you put the music forth, when you put the art forth, the performance piece, whatever, the heart of what you do speaks for itself. And that’s what you go with. You lead with that. Each time. Every time. Every second. Sure, you need to be aware of technical things, and take care of them whenever possible, but your salvation lies in what you and your friends together have. What, you’re going to blame the Pyramid for not getting a record deal? Your band broke up because the soundman at CBGB was in a bad mood last week?

The thing is, I never went and pursued a record deal. Ever. It’s too funny to even talk about. It’s like playing craps in Vegas. You know the odds belong to the house. You’ll always lose. If that’s why you’re up there doing it, forget it. You’re already fucked.

Q: Unfortunately, I’ve started seeing that more and more. You find these bands and you talk to them, and the only reason they want to be in a band is because they want to get signed. It’s like they don’t even know why they’re making music.

Jeff: Really? That’s sad. That happens all the time in Los Angeles, so I’m sort of used to that being the standard by which bands are measured – by how ambitious they are about getting a deal.

Q: I think Los Angeles was always more up-front about it being a place where bands would go and play the Strip and get signed. New York never used to have that mentality.

Jeff: That’s true. Although on the upside, even thought they’re a lot farther down in the underground, there are bands in Los Angeles who have nothing left in their lives except their music. But in New York, there’s more of an expectation of hunger – ravenous, and angry – for originality.

Sure, there are always people who are only there because they want to get signed. And in a way, that’s not a bad way to go, because the laws that govern the music business sort of point you in that direction anyway. It’s like everything is set up for the people who want to be most famous. And if that’s the place for you, baby, then go for it. But otherwise, it’s a complete 24 hour a day dilemma. And let me just say that this is a very hard thing to judge from the outside. It’s really difficult to just hang a label on someone and say that they’re only in it to be rich and famous. Because it is a completely confusing universe.

Q: Okay, but let’s take a band that’s in it for all the right reasons. They’re competing with hundreds of other local, unsigned bands who live in that area. And they’re also competing with hundreds of bands from all over the world who come through New York on tour. So it seems almost impossible for any one band to get itself noticed in that total melee. And having watched your career, it seems to me like your approach to that wasn’t any gimmicks, and you just kind of separated yourself from the pack by being good at what you do.

Jeff: Yes, I guess you could say that. And that’s a tremendous compliment. But how do you think those (industry) people got there? It was because of my association with one industry person. Somewhere down the line, even if it’s something you don’t actively pursue, it has to be somebody who knows you. One person, two people. The people who will always be my joy were the people who were there at the beginning. And we’ve had a dialogue since dirt was invented. And that’s my audience. And one of those people happened to be music business people, and once that circuit gets started, it’s like a huge chain reaction, a domino effect, all those clichés. They come either to dispel the rumor that what their friend is seeing is good, or to totally get on it, so they can be a part of it. That’s not real, though. Those aren’t real people. Because that industry thing, that buzz, that can always be taken away. But what real people feel, that’s there. Don’t get me wrong, there are record company people who are real people, who really love music. But the aspect of those people that represents their role in the music business, that can come or go. What’s real is the people who come to see you just because they’re into what you’re doing. And who get into music to experience it, not to judge it. They will always be there, as long as you keep your heart open and strong.

Q: To be honest, I’ve been around the music business for about ten years, and I really do think that the kind of people who are working in the music business now are much more into music, and less into the business end of it, than people in those jobs would have been, say, ten years ago.

Jeff: That’s true. It is a very, very different environment today. I’ve been watching it for a long time, and it is a different place. The people I deal with at Sony are just like me. They’re there because they like the music and they just happen to have a job there. It’s communicating, and agreeing or disagreeing with people, that’s all it comes down to. In the music business, ideas are like cigarettes in prison. People sell them, people steal them, they’re gold. Even if you don’t smoke.

Q: What sort of experiences did you have with the local press before your album came out? One common complaint is that none of the local papers in New York have any interest in writing about the local scene.

Jeff: Good. I think that’s good. Are you kidding? The last thing I want in my neighborhood are a bunch of people who are down there because they think they should be down there. People should come of their own volition, not because some guy in the paper says it’s cool to go.

Q: But doesn’t that just make it that much harder for bands to get noticed, to separate themselves from the throng?

Jeff: I don’t know. New York Newsday said I was stealing from the black man, and I was failing at it whereas Michael Bolton was succeeding. So fuck ’em. The Village Voice…they don’t know what’s going on. The press doesn’t matter unless the people on the staff love you. Then, yeah, they can help your career. People on the staffs of the dailies here don’t love me, so who cares… But anyway, you can’t judge yourself through the eyes of journalists anyway, because they will always be on the outside of the process, and never know anything, deeply, about your art, even though they will continue to make pronouncements about it. If they ask you questions and you tell ’em, then fine, that’s accurate. And yeah, press helps. It does help. But if you’re looking for humanism in it, forget it, it ain’t gonna exist.

#jeff buckley#New Jersey Beat Magazine#1993#jeff buckley interview#Making It In New York: Jeff Buckley#Jim Testa#may 2nd 1993#new jersey beat

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Last of the Red Hot Mamas

The Queen of Jazz

Sophie Tucker was a singer and comedienne whose powerful voice and brassy wit delighted audiences for over six decades.

Sophie’s Jewish parents had to escape from Russia in 1886 after her father had deserted the Russian military, and she was born on the boat to America. The family settled in Hartford, Connecticut where they ran a kosher boarding house and restaurant. Sophie and her three siblings worked hard in the family business, waking up at 3 am every day to peel and chop vegetables before school. After Sophie got home she waited tables and washed dishes.

From almost the moment of birth, Sophie had a huge and magnetic personality. She was confident, sassy, and uninhibited. Jewish vaudeville stars often stayed at her family’s boarding house and she was fascinated by them and their lives. She always knew she was destined for a life in show business. Her parents absolutely forbade her to join the paskudnyaks (rascals) who stayed at their rooming house. Sophie still found a way to perform – she started singing for their guests as she served them. “I would stand up in the narrow space by the door and sing with all the drama I could put into it. At the end of the last chorus, between me and the onions there wasn’t a dry eye in the place.”

Desperate to leave home, she eloped in 1903 with local beer truck driver Louis Tuck. When they returned, her parents organized a traditional Orthodox wedding for them. They had a son, Burt, in 1906, and lived with her family, where she was back to her old role of cooking, cleaning, and serving customers. Meanwhile a frequent guest was Willie Howard, a popular vaudeville comedian and the first to use openly Jewish content in his act. He was impressed by Sophie’s natural talent as an entertainer, and he urged her to move to New York and break into show business. Sophie’s husband Louis did not share her enthusiasm for the stage and after she told him she wanted to move to New York, he took off. Soon, Sophie left Burt with her family, telling them she was going to New Haven for a short vacation. Instead, she moved to New York and never returned. She was 19 years old. Burt was raised by Sophie’s family, and Sophie kept in frequent contact with them over the years.

Sophie arrived in New York with a letter of introduction to a famous composer from Willie Howard, but the composer wasn’t impressed by her singing. She was quickly able to find work singing at coffeehouses and saloons. At the German Village, a popular beer garden, she sang 50-100 songs a night for $15 a week. She was such a hit that she was soon making over $150 a week in pay and tips.

Sophie was generous with her money. She sent most of what she made to her family, and lived in a shabby boarding house where the other residents were prostitutes. A nice Jewish girl from Hartford, Sophie had never encountered this type of woman before, but she wasted no time making friends with her neighbors, and started a longtime practice of giving free women-only concerts in bordellos. Sophie shared her money and belongings with the call girls, and hid the money they made from their pimps. She later said, “Every one of them supported a family back home, or a child somewhere.”

At the time, $150/week was an impressive salary for a single woman, but it wasn’t enough for Sophie, who wanted to get out of the restaurant business once and for all and make it big in vaudeville. She got her first break in 1907: a chance to audition for impresario Chris Brown’s Amateur Night. After her audition she overheard Brown say, “This one’s so big and ugly, the crowd out front will razz her. Better get some cork and black her up.” He told Sophie that she passed the audition and would be featured in the show. However, she had to do it in blackface. Sophie was aghast at the suggestion, but Brown and the other producers insisted that her only chance for a career in show business was in blackface. She agreed to do it.

Sophie’s first vaudeville gig was at Tony Pastor’s on the Bowery where she was booked for a pre-show before the matinee. When she took the stage, the theater was empty. She started singing, but as people entered the room they completely ignored her, chatting noisily as they awaited the main event. She suddenly stopped the show, and started berating the audience for being so rude to her. Sophie had what Jews call chutzpah – audacious self-confidence – and she displayed so much humor and spirit that the audience fell in love with her. Nobody made a peep for the rest of the show, and they demanded three encores.

She was booked onto the New England Vaudeville circuit to sing African-American spirituals, and got rave reviews everywhere she went. It wasn’t just her big voice audiences loved, it was also her big personality, her confident swagger combined with self-deprecating humor. Sophie had a sharp wit and a voice that didn’t need a microphone to fill a room.

Audiences adored Sophie’s minstrel act, but she hated performing in blackface. Finally, at a performance in Boston, she’d had enough. She told the producer that her blackface makeup and costume were lost in transit, and before he could argue she marched onstage as herself. She told the shocked audience, “You-all can see I’m a white girl. Well, I’ll tell you something more: I’m not Southern. I’m a Jewish girl and I just learned this Southern accent doing a blackface act. And now, Mr. Leader, please play my song.” She never performed in blackface again.

Some of Sophie’s songs were bawdy, filled with innuendo and double entendre, while others were sentimental. Her most popular songs included “Some of These Days” and the Jewish favorite, “My Yiddishe Mama.” Initially Sophie only performed “Yiddishe Mama” in front of mostly Jewish audiences since much of the song was in Yiddish, but she soon found that all audiences loved the song. Even if they didn’t understand all of the words, they could appreciate her heartful singing about her devoted mother.

Sophie did a European tour in the 1920’s which was a huge success. When she arrived in England in 1922, she was greeted by fans with a huge sign reading “Welcome Sophie Tucker, America’s Foremost Jewish Actress!” Looking back at her career later in life, she described that sign as her proudest moment. Sophie performed for King George V and Queen Mary at the London Palladium in 1926. She greeted the monarch with a hearty “Hiya King!” The Daily Express described Sophie as “a big fat blond genius, with a dynamic personality and amazing vitality.” Yiddishe Mama became an international hit, and she was asked to perform the song in Berlin by the Berlin Broadcasting Company in 1931. Two years later, when Hitler came to power in 1933, all copies of the recording were destroyed.

Comedy writer Bruce Vilanch saw Sophie Tucker perform when he was a child. He remembered, “She’d make you laugh like crazy. She would belt. She still could blow the roof off the joint. Then she would do something incredibly schmaltzy, she would turn on a dime and make the audience weep… As soon as you were done crying, she would turn around and do some bawdy song… Everything she said was with the force of a judge making a sentence. She didn’t speak, she made policy statements.”

Throughout her career, Sophie chose songs mostly written by black and Jewish songwriters from Tin Pan Alley, including young Irving Berlin. She was close friends with her fellow Vaudeville performer Bill Robinson, known as Bojangles. When Sophie invited Bill to her sister’s wedding in the 1920’s, the doorman wouldn’t let him in, telling him to go through the kitchen. Sophie heard this and immediately pushed the doorman out of the way, closed the front door, and told the guests, “OK everybody goes through the kitchen.”

Despite her act’s raciness, she said “I’ve never sung a single song in my whole life on purpose to shock anyone. My ‘hot numbers’ are all, if you will notice, written about something that is real in the lives of millions of people.” Her songs included, “I May Be Getting Older Every Day (But Younger Every Night),” “I’m The Last of the Red-Hot Mamas,” “I Ain’t Takin’ Orders From No One,” and “When They Start to Ration my Passion, It’s Gonna Be Tough on Me.” She often made fun of her size, calling herself a “perfect 48.”

She kept improving her act, and after a decade as a solo performer, she created a back-up band of black jazz musicians called the “Kings of Syncopation.” They recorded several albums together, all of which were hits, and toured the country playing to enthusiastic crowds. In Chicago they played 15 weeks at the Palace and then at every other theater in town. Crooner Tony Bennett called Sophie “the most underrated jazz singer that ever lived.”

After a few years as the self-styled “Queen of Jazz,” Sophie re-imagined herself again, as a cabaret performer, accompanied by piano player Ted Shapiro. He became part of her act as they developed a snappy banter. Over the years she did some film, radio and TV work but what she loved most was interacting with a live audience.

Sophie married two more times, but neither husband liked being “Mr. Sophie Tucker” and both marriages failed. She said, “Once you start carrying your own suitcase, paying your own bills, running your own show, you’ve done something to yourself that makes you one of those women men like to call ‘a pal’ and “a good sport,’ the kind of woman they tell their troubles to. But you’ve cut yourself off from the orchids and the diamond bracelets, except those you buy yourself.” Throughout her life, Sophie was known for her generosity, and she gave away much of what she made to a variety of philanthropic causes. She established the Sophie Tucker Foundation in the early 1950’s, and endowed hospitals, synagogues, actors guilds, and several charitable organizations in Israel.

Sophie continued performing until the end of her life, even after getting lung cancer. While undergoing treatment she was still doing two shows a night. Sophie died at age 80 in 1966, during a months-long theater engagement. As she lay on her death bed, she asked the nurse to “bring me my chiffon hanky, bring me my wig” and she did bits from her act until she took her last breath. Thousands of mourners attended her funeral at Emanuel Synagogue Cemetery in Wethersfield, Connecticut. Known as the “Last of the Red-Hot Mamas,” Sophie’s act inspired later female performers such as Mae West and Bette Midler.

For entertaining audiences around the world for sixty years and giving generously to others, we honor Sophie Tucker as this week’s Thursday Hero.

Accidental Talmudist

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

So @lesbian-space-ranger and I accidentally created a new Zosan AU that we’ve been talking about since last night. A note: half of this is me summarizing, half of it is pulled directly from Discord because Cas (lesbian-space-ranger) has such great ideas.

This is a long post. I don’t feel like putting it under a read more. So. Enjoy. Or keep scrolling. Either works.

So this post happened

These roles just came to me. Didn’t need to give it much thought because Sanji has the appearance and demeanor of a lead singer and I like the idea of him using his skilled hands to play piano at the same time.

I also watched the movie Rocketman earlier in the week. You know, that Elton John biopic. I adored it and it’s been heavy on my mind lately and I liked the idea of Sanji giving a high energy performance from the piano. (Sir Elton John’s music comes into play later.)

And as for Zoro, I find the bass and/or the beat the sexiest part of the music in a song and, naturally, I can see him rocking at either.

So I asked Cas if she had any other headcanons for this AU and this thing is too good to not share.

Yeah, so Zoro and Sanji are in a boy band with Usopp and Luffy. Luffy started the band. Luffy does guitar, Zoro is on bass, Usopp is on drums, and Sanji is on keyboard and vocals.

Nami is their manager. She works them hard and has taken a 40% cut of the profits because of the guys’ naivete and inexperience. But she’s why they took off. She booked their gigs at every venue she could manage, no matter how small.

They got their big break when Nami met Vivi, who’s a talent scout for the record label Baroque Works. Nami insisted that Vivi had to see the boys perform because they’re something else and Vivi’s heard that a thousand times, but she agreed because Nami is cute. Nami and Vivi are dating. Also, re Baroque Works: Crocodile looks like a sleazy music producer, doesn’t he? So does Doflamingo.

So Sanji is the pretty one, Luffy is the funny one, Zoro is the quiet/broody one, and Usopp is the smart one.

Zoro has a lot of deals with fitness brands, but secretly finds the famous life unfulfilling. This comes back later, so keep that in your back pocket.

Robin runs their social media. She’s so good at her job, running all of their accounts and tweeting simultaneously, you’d swear she had four sets of hands. Wink.

Franky does pyrotechnics/lighting.

Brook is their stylist.

Chopper was their first real fan. He and Zoro grew up in the same neighborhood and Chopper just always idolized him. He followed them before anyone knew their names. He was their hype man, saying encouraging things like "I know you guys are gonna be great!" He believed in them even when they didn't believe in themselves.

Usopp set up their recordings before they got signed because he’s savvy. And then Chopper would sell their crappy CDs. At these tiny gigs. Like coffeehouses and stuff.

Sanji can play keyboard because his parents forced him to play piano as a kid. They had this idea that classical music would teach him discipline and make him smarter. This is how he meets Zeff. Zeff’s your typical stern instructor, but he’s the first adult to ask Sanji what he actually wants and likes. Zeff sees Sanji’s not into it so he asks him what music he likes and Sanji tells him he likes pop, so Zeff gives Sanji a more rounded education. This includes Elton John because I say so. It did inspire me to put Sanji on keyboard, after all.

But other than being Sanji’s piano instructor, Zeff becomes the one positive adult figure in young Sanji’s life and he becomes something of a mentor figure for him. Zeff has a garden and he lets Sanji work in it with him. This garden is how Sanji gets his “little eggplant” nickname. Sanji pulls an eggplant out before it’s ready and it’s so small and pitiful and Zeff won’t let him live it down. Like, Sanji keeps in touch with Zeff even into adulthood and after he makes it big and he still calls Sanji little eggplant.

Zoro and Sanji are always doing that, "Kind of flirting, not really” thing on stage. Sanji is always like walking up to Zoro on stage and acting like he's going to kiss him but pushing him away at the last moment. And it's this huge mystery whether they're actually an item or not. This comes from Nami. Sanji and Zoro have this natural chemistry with each other that leads to speculation and Nami, knowing how boy band fan bases work, saw dollar signs. But it’s not just pragmatism on her part; she knows that one cannot simply go up to Zoro and Sanji and say “You obviously like each other. You should date.” So she makes money and helps her friends find happiness.

Usopp has speculation going on as well. People are always confused as to who he’s dating. Tabloids keep being like "Usopp dumped Nami and is now dating Luffy!" "Luffy Scorned?" "Luffy ditches Usopp and steals his girl!" And they just think the entire thing is hilarious. They collect headlines. The answer is Usopp is dating Luffy and Nami and Luffy and Nami just become really affectionate with each other after dating Usopp long enough. Also Nami is dating Vivi, like I mentioned, and sometimes Nami brings her on as a plus one.

Sanji and Zoro keep giving conflicting answers about their relationship status. Like they'll tell one person they hate each other and another person they're gonna get married someday. Sanji has to walk this fine line of being "in love" with all of his female fans and also "in love" with Zoro. Or not. Who knows? Like Sanji enjoys the attention but he really really plays shit up for his fangirls. This makes Sanji even more popular. Just picture pages upon pages of Sanji/Reader and “Zanji” fics on Wattpad. Nami is one smart lady. "I am the smartest, prettiest, most clever person alive."

Zosan getting together really is just a bunch of Fake Dating tropes. At first it really is just to get more press for the band. Nami schemes with Usopp and Robin to push them together. Robin's a social media genius and knows how to craft tweets and Instagram posts that fans will overanalyze.

Meanwhile eventually Zoro and Sanji admit to each other they have actual feelings and one day Usopp finds Sanji sleeping in Zoro's bed, both of them completely tuckered out. But they don’t know Nami crafted this. They just come clean and hope she won't be mad and she's like, "Yes! Finally!" and they're like "What?" and she's like, "I've been waiting for you two to realize you have actual feelings. Did you really think I'd just use you for profit like that?" and they're both like "Yes" "Of course"

Zoro’s mad at her for meddling. Secretly he’s grateful, but he doesn’t want to give her the satisfaction and he’s yelling until Sanji grabs his hand and he just calms down.

And to bring Elton John back into the picture, just picture Sanji doing a cover of “Your Song” and uploading it online and thinking about Zoro. Naturally the comments are abuzz with people speculating that he’s singing about Zoro. And like. Onstage Sanji does his rendition and sends these small glances Zoro’s way, partially because he knows it’ll get the band a lot of attention, partially because that song is sweet and beautiful and it’s such a simple way to explain his feelings. (There is a reason why Moulin Rouge included it!!) I imagine this happens before they come clean to each other. Like, Zoro comes to him and is all “I keep thinking about that song you did...” And they go from there.

And eventually the band comes to its natural end.

Usopp goes solo and flourishes, working as a songwriter and a producer. He wrote the band’s songs and he’s had a drum kit since he was, like, ten and he can make his own beats. He’s not the singing type (though he is good at it and could reach new heights if he came out of his shell), so he’s the kind of artist who makes the beat and then gets super famous pop singers to feature on his tracks. But he also writes songs for other singers and is so good at it and produces other artists’ tracks. I also like the idea that he’s taught himself to play multiple instruments, but he prefers the drums/percussion. He totally played percussion in school and was in marching band. I was in marching band for one year. I loathed every second of it, but I know he’d be phenomenal in drum corps.

Luffy isn’t much in music anymore, but he keeps himself busy. He’s something of an influencer, the kind of celebrity who gets paid to wear fashion brands’ clothing. He’s also Usopp’s trophy husband, living off the money he made off the band. Usopp grew wise to Nami’s antics and made sure he and Luffy would live comfortably for the rest of their lives, even if Usopp were to retire. Luffy also is secretly a Buzzfeed journalist because it’s fun for him to write these hit articles and people not know it’s him because he’s writing on this super bland pseudonym.

And then there’s Zosan. They have a falling out after the band splits and go their separate ways.

Sanji quits being a professional singer because he’s tired of the prying into his personal life, but he still mentors and/or teaches. He has a string of girlfriends and finds no fulfillment in those relationships because the women are only interested in his celebrity.

And they aren’t Zoro.

Zoro tried branching off into commercials for fitness, but his heart wasn’t in it. He kind of takes up ranching on a whim and learns that he’s really good at it. He likes the physical labor, the quiet, being away from it all, nobody knowing his name. He doesn’t pursue anyone after Sanji because he feels like if it’s meant to be, someone will appear.

And Sanji does.

Sanji finds out where Zoro is through Luffy. So he makes his way to the ranch and finds Zoro and Sanji is all “Come back. I miss you.”

And there’s just a lot of soft Zosan content during Sanji’s visit. Sanji’s always been afraid of horses, but he’s not afraid when he’s with Zoro, and Zoro teaches him they can be gentle creatures, it’s just that you just have to respect them. (Ha. Get it?) Zoro takes Sanji on a ride and they go out and he takes him up the mountain and shows him how beautiful the view is. Sanji's watching the sunset and he's like, "Damn that's the prettiest thing I've ever seen." And Zoro is looking at Sanji and he says, "It sure is." And Sanji's like, "you're not... even looking." And Zoro's like, "No, I'm looking alright. Prettiest thing I've ever seen for sure."

More soft things like Zoro taking off his cowboy hat and putting it on Sanji. Them sitting by the fire, Zoro playing acoustic while Sanji sings. Whenever people see them they’ll ask them if they’re musicians and they share a knowing smile and say “Yeah. Something like that.”

And Zoro convinces Sanji to move out there with him. The others come to visit. Luffy and Chopper are obsessed with the cows and horses and the chickens. Luffy wants, like, eight pet chickens. Usopp is skeptical. Doesn’t believe Lu can look after a pet.

And it kind of ends there. It was us going back and forth, oftentimes out of chronological order, and so here I am putting it all together because it’s too good not to share. But it was a lot of fun.

#zosan#zoro#sanji#lusona#luffy#usopp#nami#robin#franky#chopper#brook#vivi#namivivi#long post#music au

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Celebrity Status’

Superstar fashionista. Pop idol. Professional Huntress. Official badass. Many adjectives and titles could describe the fantastically famous Coco Adel. She was staggeringly successful and wanted for almost nothing. She had her best friends with her most of the time, as Fox and Yatsuhashi played music with her. She had legions of adoring fans who loved her style, her music, and her clothing collections.

A cutie to share all of it with would be the icing on her coffee cake.

She had yet to find such a lady. Not for lack of trying, of course. She always talked to this girl or that girl, but most of them seemed to think she wasn't approachable. She would positively LOVE to throw her latest fashion ideas on a lady friend... and then tear them right back off of her. She had broken many girls' hearts without even trying.

She broke men's hearts as well, but only about as often as she broke their kneecaps. She quite enjoyed breaking their kneecaps.

Coco had dated her fair share of women, but becoming a celebrity had changed the dating scene a lot for her. It was more difficult to meet people when they were terrified of speaking to you. Being on a pedestal was fine with Coco until it came to meeting women. Oh well, one of these days the perfect girl would come along.

These coffeehouse gigs were a fun way to meet fans of her music. The clothes and the fighting were amazing, and fashion was always her strong suit, her music was her passion. She would make a sample with her keyboard synthesizer, and Fox would create sultry sounds with his guitar strings. Yatsuhashi made a beat, Moonstone added a bit on the low end, and a masterpiece was born.

Moonstone wasn't performing with them tonight, and he might not perform with them ever again. He was having some family issues at the moment. A new bassist wouldn't be that tough to find. Another girl in the band would be fantastic, Coco thought.

"What's this place called again?" Coco asked no one in particular. She knew the place was in Vale, near From Dust Til Dawn, but she forgot the name again.

"Jumping Beans, or so the sign says." Yatsu stretched and yawned as he answered. They were traveling low-key for this show, and sleeping in a van was not fun for the extravagantly tall man. He pointed to a sign across the street from their hotel. Coco nodded, tossing her beret off her head and checking her hair in the mirror.

"You look perfect, Coco!" Fox told her. She rolled her brown eyes at him.

"You say that every single time, yet I somehow still don't believe you." She replied, and the two of them laughed. They filed out of the van and entered the hotel, checking in at the counter and retiring to their room for now. They had a few hours before the concert, so they might as well rest up.

\/\/\/\/\/

Coco stood in the backstage area, which was more or less just the back of the coffeehouse, practicing her set in her mind. Her most popular song, 'Coffee' was not on the setlist, but she might perform it for an encore.

She glanced out at the packed coffee shop. Her audience was chomping at the bit for this show and the autograph signing afterward. In the small sea of faces, she locked eyes with a faunus woman holding a camera. Her chocolatey eyes melted Coco instantly. She had the cutest pair of rabbit ears atop her head. Brown hair framed her adorable face and cascaded down to her collarbones.

The woman tried to maneuver her way through the crowd toward Coco, flashing a badge and calling "News Crew" at everyone that stepped in front of her. Coco longed to run toward her and pose for a photo, and even more to chat the gorgeous rabbit girl up, but someone called for Coco to come to the stage. She waved to the photog and pointed at the stage.

Rabbit Ears nodded back, pushing her way toward the small stage.

Coco took the stage in her usual extravagant fashion, smashing a key on her keyboard and kicking outward when it produced an explosion sound. "Welcome to Jumping Beans Coffee Shop! I'm your hostess for the evening, the forever fabulous fashion queen, COCO ADEL!!!" She yelled into her microphone. The crowd roared for her.

She grinned at them all and jumped right into her first song, 'Girl is a Gun'. It was a bit different acoustic, but she still pulled it off with aplomb. She jumped around and danced away as she sang, her fingers effortlessly dancing across her keyboard. Coco kept her eyes on the photog with the rabbit ears.

"Yo, Rabbit Ears! Come closer to the stage! Be sure to get Fox and Yatsu in the pictures, too!" She called out between vocal lines. The photog's eyes turned to stars.

"Did you just talk to me?" She yelled, awestruck.

"Yeah, you're the one with bunny ears and a camera! Come closer! I don't bite! Well, not without permission, at least." She joked. The bunny girl moved right up next to the stage. Coco could hear her singing along to the song they were playing. She reached forward and tickled one of the girl's rabbit ears.

She lost it at that. "OH, MY GODS COCO ADEL JUST TOUCHED ME!!" She shrieked happily.

"You've got a pretty decent voice there, Honey Bunny. You want to come and sing one with us?" Coco offered. Hearts poured out of the girl's eyes at the remark.

"Gods, YES! Could we do 'Coffee' please?" The cutie asked her. Coco was hoping to save that one for later, but who was she to deny her beauty the song she wanted? Coco played the opening sequence on her keys, Fox and Yatsu filed in, and the two women sang into Coco's microphone. Coco took her hand and danced with her after the singing finished, the rabbit girl enjoying herself.

"Meet me after the show and the signing! I'd like to see your photos! Also, sorry for grazing your bum with my hand..." Coco told the photog after the song was over.

"It's fine, really! You're my favorite person in the world, so you can touch my arse all you like!" Rabbity smirked and winked.

A few more songs came and went, and Coco and the crew went on to sign autographs. The whole signing, Coco could hardly take her eyes off that woman on the multicolored couch. She snagged up a crew pass for their upcoming full band show with Weiss Schnee and her band and signed the back, leaving her phone number and a winky face.

"Hey there, Babbity Rabbity!" Coco said with a smirk as she plopped onto the couch, scooching as close to the girl as possible. Bunny blushed at that. "So what's your name, Miss Daily Dust?"

"Velvet Scarlatina..." The girl answered breathlessly. Coco smiled.

"Well, Velvet Scarlatina, can I please see your photographs?" Velvet pulled out her camera and scrolled through the shots from the concert and the signing. "Wow, you must be the best photographer at your newsstand! A regular Peter Parker, I'd say." Coco smiled even wider as Velvet turned ten shades of red. "You should totally take photos at our next show! It'll be a full band affair at the Rooster's Teeth!"

"I tried getting tickets, but it sold out ages ago. I also don't think my boss will send me to a show that size." Velvet frowned.

"Well I'd love to see you again, so take this. It should get you in with no questions. If anyone gives you any attitude, send them to me and I'll tear them apart." She winked.

"Thank you so much!" Velvet tried to say as she stood, though it came out as a jumble of syllables. Coco smiled and stood up, hugging her new friend.

Velvet let out an 'EEP' as she felt a squeeze at her rear. Coco smirked hard at her as she left the coffeehouse. She could hear Velvet cheering from outside. She must have enjoyed the squeeze, or perhaps the phone number was the cause of her happiness.

Her Scroll lit up with a message from her new favorite girl.

\/\/\/\/\/

\/\/\/\/\/

\/\/\/\/\/

Day 5: Team CFVY Member

Do you guys remember ‘Coffee’? I wrote it ages ago. Well, this is kind of a parallel to that fic. The same concert from Coco’s POV.

#fanfic#mine#Crosshares#Coco x Velvet#Velvet x Coco#Chocolate Bunny#Coffee Cake#RWBY#RWBY Fanfiction#RWBYAC 2019#Coco Adel#Fatal Fashionista#Velvet Scarlatina#The Fluffy Photog#Crosshares for the win#they're so cute#Zwei The Penguin With A Pen#Daily Dust#a Daily Dust fic#Coco is a Pop Idol AU#AU#Velvet is a News Photographer AU

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coffeehouse Chic: Tony Padilla x Female Reader

Request: Can you write a tony fluff with a female reader where she sings and plays piano and he’s just all fluffy and comes to her concerts and stuff. Thank you!!!!! Love you!!!

.

Your hand pulled at your hair roughly and absentmindedly as your elbow rested on the table in front of you. You twirled your pencil around, scratching out words and musical phrases you didn’t like. The words and music flowed perfectly in your head, but you couldn’t seem to make it work on paper. The plastic cup of coffee clicked loudly under your fingernails as you tapped on it with your free hand.

“Thought I might find you here.”

You stared up, eyes burning from looking at the papers too closely for hours. Tony made it halfway across Monet’s, sitting down at your table. He gazed across at all the various noted computer papers and manuscript papers in front of you.

“Well, yeah,” you mumbled to your boyfriend softly. “I come here all the time to work on this.”

Tony nodded with a soft smile as you stared back down at your papers. “Have anything new?”

You shrugged. You weren’t trying to ignore Tony, you were just more focused on your work- and you also knew the boy wasn’t taking it personally. “Maybe. If I can finish editing the music itself by tomorrow, I might put it in Friday’s setlist.”

“Can I see?” Tony leaned over, knowing with a grin that you never let him look at your new projects. You pulled the paper in your hand back, hitting his leather-clad shoulder lightly with a grin.

“Fuck off,” you gave a soft laugh to him, leaning back.

Tony leaned back again with a gentle smile, straightening his jacket. “Can I get you another latté?”

You sighed, shaking your head. “I’ve already had four. More coffee is the last thing I need right now.”

When Friday night came, you had arranged your setlist and organized everything you needed. It was a basic and general performance- a regular-sized café, a grande piano in the middle, even a large area around the various tables where people mingled briefly.

Tony sat next to you at a back table, holding onto your hand gently as you spoke to the owner of the café. The man confirmed how much he was paying you, when, and how he would. He nodded, left the table, then encouraged you to be up on the small stage by eight.

"Will I be hearing your newest project tonight?" Tony leaned against the back of his seat with a small smile.

"First on the setlist," you declared softly back. You leaned towards the Latino boy, gently pressing your lips against his. He kissed you back, then watched you with a gentle smile as you pulled back.

"I should go get ready. I only have ten minutes." You stood from the table, brushing your hand against Tony's arm.

Tony gave a small nod. "I'll see you after, Gatito."

Nearly fifteen minutes later, you were sitting up at the front of the large room, the owner of the live-music-café introducing you. You started off your setlist of songs- all written by you. Your hands flowed gently across a few chords of the piano.

"Throwing my feelings out the window,

I can see no other way.

They've hurt me so bad,

And the glass ain't so far away.

Throwing my feelings out the window,

Send them reeling into space.

Just gotta undo the hatch and feel the breeze in my face."

.

When you came down to meet Tony again, your throat was beginning to get sore and your fingers cramped- a usual happening after your gigs. The short Latino boy met you with a smile, wrapping one arms around your shoulders gently. "You sounded beautiful, Gatito."

You held onto Tony's hand with a small smile. "Thanks. You say that every time," you added with a small laugh.

"Because you do everytime," You turned to face Tony once you were standing outside on the sidewalk with him. You gave a gentle smile before pausing, then he leaned in closer to you. You pulled yourself forward, kissing him back gently.

"Let's go back to my place," Tony decided out loud. "We can... Celebrate there."

You turned your head down in the dark with a quiet laugh. "All right. Let's go."

A/N: I wrote this on my phone in the emergency room ahahaha but those lyrics are from my own song called "Out The Window." It'll be on Spotify, Google, and YouTube on June 11 under the label Oli Katai with the album "Overlay". Until then, you can search up my music for my first published EP called "Basic Bitch" and a single called "Ways To Say I Love You"

#13 reasons why#13 reasons why tony#13 reasons why ryan#13 reasons why imagines#13 reasons why imagine#13rw#13rw imagine#13rw imagines#13rw fanfic#13rw spoilers#13rw tony#13rw tony padilla#tony padilla x reader#tony padilla imagines#tony padilla imagine#tony padilla

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pearl is an extraordinary album for more reasons than meet the eye and ear. It was the last album Janis Joplin made before she left us, too soon, the victim of an accidental drug overdose at the age of 27. To her, this album represented the best music she had made in her life, and Janis was, first and foremost, a dedicated musician, serious about her art. From her earliest appearances on-stage in small bars and coffeehouses in her home state of Texas, her career was a quest, a restless search for the music that could exercise the full range of her voice, demand all the shades of its tone, express all the motions she experienced — the music that would fulfill her and make her whole.

No single style of music could do that, of course — not the country blues or bluegrass, not folk, rhythm and blues, or rock and roll. And so, she had to keep searching, testing each of the established forms until she realized that she would have to decline her own music in her own way.

Her explorations began in earnest when she arrived in San Francisco in 1966 to join Big Brother & The Holding Company, one of the seminal bands that contributed to what became known as the San Francisco Sound. Big Brother’s music probed the outer limits of the known forms in American music; it was spacey, innovative, unfettered, sometimes outrageous, rooted in the blues and powered by the solid backbeat of rock and roll.

With Big Brother, Janis took the San Francisco Sound and made it her own. She became the darling of the local fans and then, suddenly, at the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967, of a much wider audience. The following year, she and Big Brother toured the L. S. and put out a gold album for Columbia Records, but the abrupt rush of stardom didn’t satisfy Janis questing nature. Instead, it impelled her to test the limits of what she could do on her own.

She left Big Brother and hired a back-up band with horns, to give her more of a soul sound. She toured Europe and triumphed in Paris and Copenhagen, Stockholm, Amsterdam, Frankfurt, and London, «here she sold out the Royal Albert Hall. The album she recorded with this band, I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama!, reached number five on Billboard’s Top 100 album chart, but this success, like the others before it, only encouraged Janis in her quest. Life on the road with the Kozmic Blues Band was never smooth; there were personal and musical conflicts in the band, and it was a lar cry from the family-band feeling of Big Brother & The Holding Company.

At the end of 1969, Janis disbanded the Kozmic Blues Band. She took some time off. She went to Rio de Janeiro for Carnaval. She backed off from the alcohol and drug use that had sometimes affected her performances with Kozmic Blues. She cleaned up her act. And during those reflective months, her luck changed. In her first year as the leader of her own band, she had learned a lot. Now she was ready to put those lessons to use.

The Kozmic Blues Band had been assembled for her by musical advisers. In putting together her next band, Janis was involved every step of the way. She kept two members of Kozmic Blues — Brad Campbell on bass, and John Till, who had finished up the ‘69 tour on lead guitar. She and her manager, Albert Grossman, went out, listened to musicians, and recruited three more-Clark Pierson on drums, Richard Bell on piano, and Ken Pearson on organ. Before this group played their first gig they were christened with a name that expressed all the hopes Janis had for the new band: Full Tilt Boogie.

I had worked for Janis for two years as her road manager but 1 quit during the last weeks of Kozmic Blues because it wasn’t fun anymore. I came back for the summer tour in 1970, and after two weeks on the road I knew Janis had another winner. From the start, this collection of musicians was a band. The Full Tilt boys liked Janis and she loved them both on-stage and off. She was the leader now, for real, and the boys followed where she led them. Even before the tour began, she was comfortable enough with the band to consult them about a nickname for herself. She wanted a name that would emphasize the aspect of her personality that wore gold hooker pumps and picked up pretty boys in bars. What about “Rose,” or “Ruby,” she offered, or “Pearl”? What “Pearl” became, to her delight, was a name that those closest to her used when they were speaking to her with special love and affection.

The summer tour took us from Miami to Honolulu and Toronto to L.A. Janis sang in Shea Stadium and Harvard Stadium, and the tennis stadium at Forest Hills. I had never seen her so happy in her music. When it was time to record, her good luck held. For the first time, she got the record producer of her dreams. Paul Rothchild had produced the Butterfield Blues Band. He had produced The Doors. He couldn’t carry a tune, but he knew how to talk to musicians, and he could top anybody’s rap. Janis had a pretty good rap of her own and she found that she loved to talk with Paul. They talked in the studio and they talked in the bars after hours. And Janis began to learn from Paul Rothchild something she never expected to learn: how to sing in a new way, without holding back-she would never give a song less than everything she could-but in a way that would allow her to sing for years to come. For Janis, this was a revelation. She had taken it for granted that at some point she’d blow out her voice and retire to run a bar in Marin County. Through working with Paul, her future opened up before her, without limits.

For Paul, every day with Janis was a revelation: “Of all the lead singers that I know, or have worked with, she was the most workable,” he recalled a fess years after those sessions. “She was a producer’s dream, for me. It was a perfect union. I mean there is rarely a week, now, that goes by when I don’t mourn the passing of Janis not just for Janis but for me loo, because it was perfect. To me it was as if my entire career was pointed at working at that record- working on that record and working with Janis.”

Four weeks into the sessions with Pull Tilt Boogie, when the album was three-quarters done, Janis died suddenly, unexpectedly, tragically. She started fooling around with heroin again, thinking she could control it, but her luck turned, and she died. From that moment, there could be no other title for the album but Pearl. And the miracle of Pearl is that it’s not some half-baked collection issued after her death as a sentimental tribute; it’s exactly what Janis and Paul intended it to be from the start — her best album ever. Because Janis had recorded just enough vocal tracks to finish the album.

Paul and the Full Tilt Boogie Band worked for weeks, day and night, constructing entirely new instrumental tracks behind Janis’ existing vocals. Bassist Brad Campbell remembered it as one of the most intense periods of his life. “You’ve got to realize something, from the standpoint of playing to the voice. It was really something. Really something. It’s not like, well, you can do it tomorrow or you can do it the next day. It was just like, ‘This has got to be the one. I can’t really explain it, because it was a super fecling. The voice was the only thing that was entering my head.” Paul Rothchild agreed: “We froze a moment, a mood, a great thing. And we were able to sustain ourselves emotionally based on our previous good time.”

Pearl is a testimonial to Janis and her hand’s mutual admiration and love. Janis’ joy in the Full Tilt boys, in the material, in her life, comes through in every song, even in Nick Gravenites’ “Buried Alive In The Blues, which he wrote for Janis, and which was the only song for which she had not yet recorded a vocal. Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee” became a number one single. The album made it to the top spot as well and stayed there for nine weeks. Among the top 100 albums of the years 1955-1996, Pearl ranks number eighty. It is Janis’ most successful album. “I think it is Janis’ best album. I think it is possibly my best at bun. I think it’s one of the great records to come out of the Sixties. I think it’s wonderful.” Paul A. Rothchild

— John Byrne Cooke; a novelist and screenwriter. from 1967-1970 he was Janis Joplin’s Road Manager.

0 notes

Text

Interview with Brandon Jenner

We had the pleasure of interviewing Brandon Jenner over Zoom video!

Brandon Jenner’s music feels like a lot of different things—often all at once. In some ways, it’s like your childhood best friend disclosing an important truth by the glow of a beach bonfire. In other ways, it’s like the moment you stop worrying about what other people think and can laugh and smile anywhere without apology.

However, the Los Angeles-born singer, songwriter, and producer describes what his music feels like best.

“I try to make it feel like a warm, cozy blanket,” he laughs. “I hope I’m able to be that way in life as well!”'

Music always gave him this warmth. With a singer-songwriter mom, he went from “being a fly on the wall” in his stepdad’s studio (just Google his stepfather!) to developing his own relationship with music when Ben Harper’s “Forever” got him through his first true breakup. After a pair of EPs and major syncs as one half of Brandon & Leah, he launched his solo career with the independent Burning Ground EP in 2016. The title track amassed over 26.5 million Spotify streams as he claimed coveted real estate on popular playlists such as Your Favorite Coffeehouse, License to Chill, and more. In between touring with the likes of Rachael Yamagata and Joshua Radin, he unveiled the Face The World EP [2018], Plan On Feelings EP [2019], and So Childish EP [2020]. After a whirlwind of gigs around the world, marriage, and the birth of his twin sons, he personally wrote, recorded, and produced his Nettwerk debut EP, Short of Home, in the middle of the Global Pandemic.

Coupling life changes with a lifetime devoted to music thus far, he opened up like never before.

“I think I’ve gotten better at giving myself the license to be truly vulnerable,” he admits. “It’s about what the songwriter is willing to let the listener in on. I’m not trying to overcompensate for the blessings in my life anymore. I’m writing about the changes in my life. I wanted to go back to what got me to play music in the first place, which is singer-songwriters with songs that make you think and feel deeply. For the first time in a long time, I have a label partner too, and I’m really excited about that.”

He introduces Short of Home with “Something About You.” Faintly plucked acoustic guitar wraps around his intimate delivery as he delivers a love letter to his wife.

“The lyrics just seemed to roll out like a runaway train,” he says. “It was an overwhelming feeling that brought me to tears. I’m so happy and grateful. It captures my first impression of my wife and my love for her.”

Originally penned in some “hipster-y hotel in New York,” slide guitar echoes underneath dusty verses on “There You Are” as his high-register hypnotizes on the hook.

“It’s mostly about how society forces us to lose sight of the fact the only thing we have is the present,” he admits. “We spend so much of our time planning for the future—which causes stress—that we spend very little time in the present. It’s a reminder we have lungs that work and hearts that beat. You’ve got to silence the noise of society and be in the moment.”

“Give It All You’ve Got” rides along on upbeat guitar towards an affirmation to “live life without filtering yourself through the opinions of others.” Then, there’s “Life For Two.” Written at the request of a dying fan in Denmark, he gives her two children “a song about what their mom went through.” Everything culminates on “Wolves.” A piano-laden rumination, he croons a heartbreaking refrain, “No, you’re not special to me anymore.”

“It’s the moment when you’re over someone,” he comments. “It was written with a lot of emotion because it’s what I was going through at the time. It’s honest. I’m not trying to do anything other than express myself. I found myself in an energetic shift that needed to take place.”

In the end, Brandon Jenner’s music really feels like home.

“In the past, I just wanted people to respect me as a musician,” he leaves off. “With my last name, it was something I was hung up on. I don’t care so much about that anymore. What I really want is for somebody to feel the emotion I did—to feel better, safer, more inspired, and like the world has meaning. I went through so many challenges and changes and found relief. If you do as well, it’s all worth it.”

We want to hear from you! Please email [email protected].

www.BringinitBackwards.com

#podcast #interview #bringinbackpod #BrandonJenner #Jenner #zoom #aspn #americansongwriter #americansongwriterpodcastnetwork

Listen & Subscribe to BiB

Follow our podcast on Instagram and Twitter!

source https://www.spreaker.com/user/14706194/interview-with-brandon-jenner

0 notes

Text

“Up Close and Personal - That’s What Sharing Music is All About.” An Interview with Dennis Taylor

An Interview With Dennis Taylor, North Country Primitive, 20th April 2015

New age music is a much maligned beast. By and large, it has still to receive the critical reappraisal given to other styles and genres that developed in the 1970s. Maybe this is because its peak followed the year zero swagger of punk, and its expansive, meditative soundscape was the diametric opposite of punk’s short, sharp shock; or maybe because it was seen as the final swansong of the old hippies and baby boomers – mellow music for mellow people; or maybe because at its most soporific, it always contained within it the risk of moving a little too close to elevator music. Of course, such sweeping statements are patently unfair – the new age movement contained within its ranks many questing, exploratory musicians who were willing to incorporate the influences of Indian and world music, folk and minimalist composition into their sonic palettes. And by the early 80s, the new age movement was the natural home – in many ways, the only home - for fingerstyle guitarists influenced by Fahey, Kottke, Basho and the Takoma school of players.

Whilst John Fahey noisily denounced any attempts to include him as part of the new age movement, Robbie Basho found a home on Windham Hill, the leading new age label. The label’s founder, William Ackerman, was a fingerstyle guitarist whose debut album, In Search of the Turtle’s Navel, slyly acknowledges Fahey’s influence in its title. By the early 80s, American Primitive guitar was part of the new age pantheon, even if, as another Takoma alumnus, Peter Lang, has observed, the style was too folk for new age and too new age for folk. In any case, you only need to listen to the 2008 Numero Group compilation, Wayfaring Strangers: Guitar Soli, where many of the featured artist were associated with or influenced by Windham Hill, to understand that the new age movement, or at the very least the acoustic guitar aspect of it, is ripe for re-evaluation.

All of which brings us to Dennis Taylor, whose sole album, 1983’s Dayspring, was released on CD for the first time earlier this year by Grass Top Recording, who have also brought us new editions of two of Robbie Basho’s later albums, as well as showcasing contemporary players with their roots in the American Primitive tradition. Dennis is unabashedly a graduate of the new age movement and over the years his music has incorporated many of the diverse strands that make up the new age sound, which is, after all, less a genre and more a statement of intent – he has incorporated fingerstyle guitar, wind synths, looping, Indian classical music and world fusion into his oeuvre. Dayspring, however, is a solo acoustic guitar album, and although it is clearly at one with the new age, it is also steeped in the Takoma tradition Dennis had been drawn to at the start of the 70s.

Dennis’s musical journey began in typical fashion for many young Americans growing up in the late 50s and early 60s, even in such far-flung corners of the States as small town Nebraska. “Like a lot of kids my age,” he recalls, “I first became aware of the guitar through the singing cowboys on TV and the early rock ‘n’ rollers. The Everly Brothers, with their twin acoustics, come to mind. I also saw Johnny Cash at my first big time concert when I was 8 years old. I think it was about that time that I asked my folks for a guitar and lessons.” By the time he was entering his teenage years, The Beach Boys and The Beatles were riding high, and he was caught up in the swell of excitement they generated. He adds, “I also had a love of pop guitar instrumentals, which meant The Ventures and surf guitar music were big for me. My friend and I taught ourselves to play with the help of a record and book set, Play Guitar with The Ventures. We learned the popular surf guitar tunes and moved on from there to starting a band and learning the rock songs of the era. I was also taking drum lessons, so I started in the band on drums, but then switched to rhythm guitar when we got a drummer with a full drum set. My main function throughout most of the eight years we had the band was lead vocalist. Instrumentally, I switched between guitar and bass, as members came and went.”

By the time Dennis was starting college, he was developing what was to become an enduring interest in acoustic guitar. “I became aware of the acoustic side of artists like Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Paul Simon, Crosby, Stills and Nash and the newer artists like James Taylor and Cat Stevens. So by now, I was splitting my time between playing electric music with the rock band and acoustic rock with my trio or sometimes solo.”

A pivotal moment came when he became involved in sing-a-longs at a local church youth group. He remembers, “It was there that an older friend taught me the basic ‘Travis-picking’ that got me started on fingerstyle guitar, although at this stage it was still as an accompaniment to vocals. I also had started listening to the acoustic guitar soloists I had discovered at a local record store, the Takoma guitarists - John Fahey, Leo Kottke and Robbie Basho. I learned a couple of their instrumental songs and started writing my own first guitar instrumental, the song that evolved into Reflection of the Dayspring. But mostly I was still writing singer-songwriter acoustic music with vocals.”

His rock band, The People, had folded by the time Dennis finished college. By now, he was married and had a child on the way. In order make enough of a living to support his new family, he began to seek restaurant gigs as a solo singer and guitarist, whilst playing in Top 40 club bands and teaching guitar at a local music store. “As it was, the only real steady money to be made was by going on the road with a band every weekend. I ended up doing that full time for the next few years. At the same time, I continued to pursue my acoustic music on the side and did occasional park and downtown outdoor concerts, keeping a hand in on the acoustic side, both solo and with a couple of friends.”

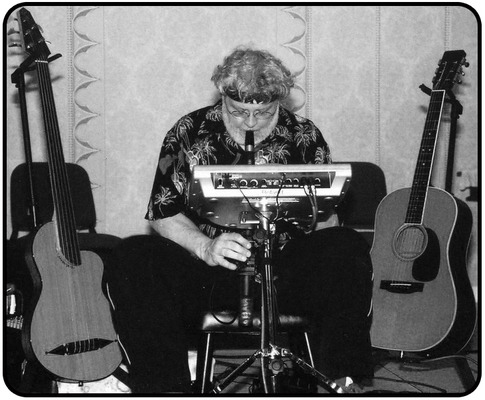

Life on the road became increasingly incompatible with family life. ”I quit the road band business in the mid-late 70s to be able to stay at home. I tried to do this by taking on guitar students at home and also teaching and working at music store. By now, I was seriously writing solo guitar instrumentals and I was starting to get enough original guitar pieces to perform solo at a few coffeehouses and concerts.”

Around this time, Dennis and his family moved out of the city for a quieter life in a small Nebraskan town, where he continued to teach guitar and work in a music store. It was whilst living in this community that several of the pieces that found their way onto Dayspring first emerged. “We had a small artist’s community,” Dennis recalls, “And I lived right across the street from a good friend, Ernie Ochsner, who was a visual artist. He was painting giant murals for a local museum and other landscape pieces, as he was getting pretty well known across the country through art shows and such. Ernie and I would hang out every day in his studio on the third floor of a downtown building in the town square - he would paint, while I would play the guitar. Many of the early Dayspring pieces evolved from those sessions. Before I moved back to Lincoln, I played my first official solo guitar concerts at the local art museum and the following year, I played my guitar pieces live on the radio for the first time.”

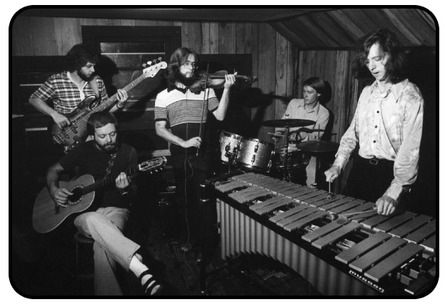

By 1979, following a spell developing his fretless bass chops with a jazz-rock band and by now living back in Lincoln and still working at a music store, Dennis joined The Spencer Ward Quintet, a band playing a hybrid of jazz fusion, world music, folk and semi-classical music. “It was all original music, written primarily by the leader, who was a nylon-string guitarist. The band consisted of classical guitar, vibes, flute, violin and drums. I sat in with them on fretless bass and convinced them that it would really fill out the sound of the music. At the same time, I was still pursuing my now all-instrumental solo guitar music, doing solo guitar gigs in many of the same clubs in Lincoln where the band would play. I was also still doing park concerts and outdoor downtown lunchtime concerts as a solo guitarist.”

The bandleader had visited Portland, Oregon in the Pacific Northwest, where some of the local musicians convinced him that their acoustic/electric fusion would find an appreciative audience. As they had already built a large and loyal following in Lincoln, the move seemed like the next logical step in the band’s evolution. “The band moved to Oregon in the spring of 1980. A couple of months later, in the summer, I joined them out there, but I was uncomfortable with the big city aspect. The other members all had day jobs, but so far, gigs were not happening. I made a quick decision to move down to Eugene, Oregon, a small college town that was more the size of city I was used to. As it turned out, there were a lot good musicians in Eugene, but work was very scarce, both musically and even for day jobs. Within a few months, my money had run out and I was not even close to gaining any kind of musical foothold. So, I packed up and headed back to Lincoln, a place where I had already established my self as a solo guitarist through clubs concerts and doing live radio at a local station. I came home to Nebraska determined to not get distracted musically again from my solo guitar work and to make a record of my solo guitar music before I turned 30 years old.”

“I started putting the music of Dayspring together, started teaching guitar at a music store again, played my solo gigs and also took the opportunity to put a jazz piano trio together with two friends, with me on fretless bass, working a lot of the same clubs and concerts I was playing as an acoustic guitarist.”

Encouraged by Terry Moore, the owner of Dirt Cheap Records, the foremost independent record store in Lincoln, Dennis went into the studio to record Dayspring. “Terry was an alternative icon in Lincoln,” he recalls. “He had also helped to start and mostly funded our local whole food co-op store and KZUM, our listener-owned, volunteer programmed radio station. He so loved and believed in the music I was doing for Dayspring, that after it was recorded and I had got to the point where I’d decided to release it independently, he offered to pay for a small pressing of LPs himself, which I would repay through sales. As it turned out, I was able to pay for the records on my own, but he helped promote Dayspring through his record shop and in fact had me do a release debut by playing live all afternoon in the front window of the store - a truly fun event for everyone!”