#so many new verbs and nouns and adjectives...

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

mr. asım tanış don't you think this is a little overwhelming.

#two whole pages total of new words. sir#🌙rambling#''Epeyce yeni kelime verdik ama korkmaya gerekçe yok. Hepsini en azından otuz kırk sayfada inceleyeceğiz.#Böylece her sayfa başına üç dört yeni söz düşer ki bu da italyanca öğrenmek isteyen sizler için çok sayılmaz.#Kelimesiz yalnızca dilbilgisi kurallarıyla bir dili öğrenmenin‚ uygulamanın‚ olanayacağını söylemek gerekmez.''#sir! sir please you don't understand#(<-he'll be fine)#they are at least mostly words i know or can figure out due to similiar roots in english/turkish. i won't die its fine im being dramatic#but on god. sir its two whole pages of new vocabulary#so many new verbs and nouns and adjectives...#an adverb in there too.#well! these all look like words that will be necessary in the future and things i'd have to learn regardless.#so i can see where mr asım tanış is coming from#on the other hand. sir

0 notes

Text

silly and weird tom hcs

a/n: the last ones got deleted for some reason so I'm making a new one!

• this mf steals your food all the time. hes always munchin on something so if you have something that looks good, he's taking it. especially if it's watermelon. he loves watermelon 🍉

• he doesn't tell anybody, but he gets his nails done. he gets pedicures and manicures and loves it so much. you found out one day when he kept going off and not telling anybody where he was going. so you followed him and saw his finger and feet soaking in water 💀

• when you walked in you were trying so hard to hold in a laugh and he was so fucking embarrassed when he saw you. you thought it was extremely ironic because he always called mani-pedis "girly"

• now you two go all the time, and you're way better at making excuses than he was.

• he got high on edibles and thought his feet weren't attached to his body anymore so he started screaming 💀

• over indulges on gushers when he's high

• you guys know those Chinese finger traps? Idk if that's what they're called but you put two fingers in them and they're like really hard to get out of. he LOVES them for some reason, he thinks they're so much fun

• he loves the snow so much, and especially loves snowball fights. it's so much fun, and he also gets to wear extra layers of clothing because of the cold

• during the winter, he gets a bunch of different kinds of hot chocolates and when anybody asks what he's drinking he swears by it that it's black coffee 💀

• he loves watching futurama and says that he strives to be bender 💀 (have yall seen the new episode? I actually really liked it, ik a lot of people said they didn't but I did.)

• gets on his knees while begging (not sexually 🤨) and will even fake cry. he's a master manipulator 💀

• when you guys go to the beach he's always asking you to come play in the water with him

• for any reason if you guys happen to be at a hospital, he goes and looks at all the little newborn babies. they're so cute and he gets all smiley just looking at them.

• he loves romance movies. mf will deny it till the day he dies when anybody asks but you've seen his collection of vhs tapes and dvds. plus bill even admitted tom cried during The Notebook.

• he tries to balance random objects on his head while walking to see it he can do it. he'll add on a object every time he does it.

• he's weirdly amazing at solving Rubix cubes?

• he loves making balloons animals and he always makes the sword ones. he will literallt sword fight with anybody.

• he eats bowls and bowls of cereal so he can get to the prize at the bottom of the box. (I full-heartedly believe he's a little kid at heart)

• he tries to make home-made pizza but ends up burning it 90% of the time.

• he's extremely ticklish on his armpits, stomach and feet and will literally die laughing if you tickle him

• he also loves kids cartoon movies like fox and the hound, Anastasia, Mulan, James and the Giant Peach, etc.

• he loves slap bracelets and has an entire collection of them.

• it wouldn't be the first time you've caught him dancing and singing to Britney spears.

• tom loves everything bathes. on camera he says he prefers showers but in reality he likes bathes better. With candles, dimmed lights, bath salts, face masks, etc.

• do you guys know that episode of Friends where Monica convinces Chandler to take a bath and he ends up loving it and shit? he's just like that. if you don't know what I'm talking about here's some clips.

clip 1

clip 2

• he tried on one of your thongs one time because you dared him to wear it the whole day.

• you also dared him to get his legs waxed and he ended up doing it and he was crying the whole time

• he loves those little stories where you add in words to them. I can't remember what they're called but it asked you for like an adjective, plural noun, verb ending in ing, etc. etc. (I hope yall know what I'm talking about, I think it starts like a m or something someone tell me please 😭)

taglist: @hearts4kaulitz @burntb4bydoll @spelaelamela @bored0writer @fishinaband @billsleftnutt @tokiiohot @bluepoptartwithsprinkles @saumspam @5hyslv7 @killed-kiss @memog1rl @80s-tingz @billybabeskaulitz @victryzvv9 @banshailey

#tokio hotel#tom kaulitz#tokio hotel x reader#tokio hotel smut#fluff#smut#tokio hotel edits#tokio hotel fanfics#tokio hotel fanfic#tokio hotel imagine#tom kaulitz x reader#tom kaulitz fanfics#tom kaulitz smut#tom kaulitz x reader#tom kaulitz headcanons#kaulitz twins#kaulitz twins tokio hotel#tokio hotel tom kaulitz

647 notes

·

View notes

Text

WWW: What's the "reflexive indicative"?

I've been meaning to write this for a while, but I wasn't sure what it really meant and now I have a theory. I am a professional linguist. I teach translation, so grammar/syntax is something I have spent a lot of time on.

Now, brace yourselves, because I'm going to be explaining modern English grammar and most schools in the English-speaking world are still teaching traditional grammar. I don't know how well versed BLeeM is in modern grammar, but we'll give him the benefit of the doubt.

Let's start with the basics. Indicative is a grammatical mood. Moods effect the reality or truth of a clause. The indicative mood is one of the realis moods, meaning that the clause is true in the tense. (Irrealis moods can make the clause possible, hypothetical, desired, etc.) The other realis mood in English is declarative. The difference is that a declarative clause uses a verb as its predicate and an indicative clause uses a noun or adjective as its predicate.

In modern grammar, the predicate is the word or phrase with the most important meaning. To put it another way, the predicate is the word or phrase that the rest of the sentence "depends" on (see: Parse Tree). So, "I am running" is declarative and "There is a shotgun in the drawer" is indicative.

Whatever magic's "reflexive indicative" is, it's roughly equivalent to "a thing exists" or "a thing is [adjective]".

Next, reflexive is term used in grammar to refer to anaphoric nouns. An anaphor is a word that refers back to another word or concept. In "we climbed a mountain and said mountain was tall", the participial adjective 'said' marks the following noun as an anaphor. Anaphoric nouns are usually analyzed as pronouns; e.g. "itself". Some English pronouns are only sometimes reflexive, like "that".

This means that the "reflexive indicative" has to be a couple things. First, we know it's somatic, so sign language basically. Second, it's a full clause. One gesture for a full clause isn't difficult. In many languages, there are verbs that do not need any nouns to be satisfied. Consider: "It is raining". 'It' is a dummy pronoun; it doesn't mean anything. In ASL, it is a single gesture. However, a reflexive indicative clause must have a noun. In short, the somatic gesture most likely means "a thing mentioned before exists".

My theory is that the reflexive indicative is used as a kind of anchor. It may be a conjunction between two magical actions: "Control the edges of the tear. Those edges are there. Bring them together." It might also be used as punctuation to end an action: "Bring the edges of the tear together. That tear does not exist." or "Connect the edges of the fabric. That fabric is whole."

If this is true, I would theorize that early in the development of wizardry, the reflexive indicative was used either 1) to assist the wizard in their focus (assuming that WWW's magic is the manifestation of will) or 2) doing magic this way was so new that it was "low context". Low context communication involves a lot of specifics and reflexive nouns are more frequent in low than high context communication. Insulated communication systems tend to become higher context over time.

Brennan mentioned that the more people who know a particular spell, the less potent it becomes; hence the Citadel tightly controlling who has access to spells. However, more people knowing a spell might also increase the level of context the spell has, thus making the reflexive indicative unnecessary.

This would make even more sense if magic was always an interaction with the spirit world. Whatever spirit is making Mending possible has become so familiar with it that the reflexive indicative is understood.

But at this point, we are into untethered speculation. That's the theory. We'll see what info Brennan drips out next and if my theory holds up.

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tag Game Instructions and Ediquette

This post is for anyone who wants to get involved in tag games but isn't sure how they work. I hope this helps<3

Instructions for some popular games and other things to keep in mind are beneath the cut.

If you guys could share this around to help some friends out that would be great!

Last Line Tag

Share the last line you wrote for a WIP. "Line" is a pretty lose term, it can mean anything from a paragraph to a sentence depending on your personal definition, or depending on how much you feel like sharing. It can also come from any WIP, and normally people share prose but sometimes if they haven't written prose recently you'll see them sharing bullet points from outlines or worldbuilding documents.

Heads Up Seven Up

Pretty much the same as Last Line Tag but, instead of one line, you share the last seven you wrote. Once again, a "line" can be anything from a paragraph to a sentence, they can come from any WIP (you could even have, say 3 lines from one WIP and 4 from another if you want to share both), and it is normally prose but sometimes you'll see people sharing outlines or worldbuilding. It is also very informal. If you want to share eight lines or five lines instead of seven you are completely welcome to do so.

Six Sentence Sunday

Another similar tag. On a Sunday (in your time zone), share the last six sentences you wrote. Again, they can come from any WIP (or multiple WIPs), it is normally prose but can be from other things, and you can share three sentences or ten sentences instead if it please you.

Find the Word Tag

The person who tagged you will have given you four words to find in your manuscript. Ctrl+F your document for instances of those words and share one (if there is more than one) of the lines where they appear. If you don't have the word, you can change it to something similar (for example, you can change giggle to laugh if you don't have giggle in your document) or you can just say you did not have the word and leave it blank. You'll need to pick for new words for the people you tag to find. Try to pick common words, but not too common. Everyone will have a bajillion "said" in their draft but will likely have only two or three "screamed". Pick a mix of nouns, adjectives, and verbs, and an adverb if you want to be spicy.

A few last things about tag game etiquette:

You are under no obligation to do any of the tags you've been tagged in. You are allowed to save them for a month from now, do them tomorrow, or just ignore them entirely. No one is holding you accountable to it.

When tagging someone, especially newer writeblrs, it is generally good etiquette to specify that they are under no pressure to do your tag. Something like "tagging (but no pressure)" is fine.

Generally try to make sure someone is open to tag games before you tag them. If you aren't sure, it is okay to tag them once to see what happens but if they don't respond assume no. Some people will specify in their bio or intro post if they like tag games. You can also make a post asking others to interact if they want to be tagged.

Make your own post to respond to the tag. Don't reblog the post that tagged you with your own response.

You can link to the post that tagged you by copying the post link and pasting it into yours. Press the three dots at the top of the post that tagged you and select "Copy Link". On your own post, select a word and press "Paste" or Ctrl+V. The word will be underlined. Anyone who presses it will be hyperlinked back to the other post, like this.

It is polite to like, reblog, and/or leave a comment on a post of the person that tagged you.

Put particularly long posts beneath a Read More.

You can tag as few or as many people as you would like, or you can leave an open tag for anyone who sees the post and wants to participate. You can also tag people and leave an open tag.

That's all Folks! And have fun with the tag games!!

341 notes

·

View notes

Text

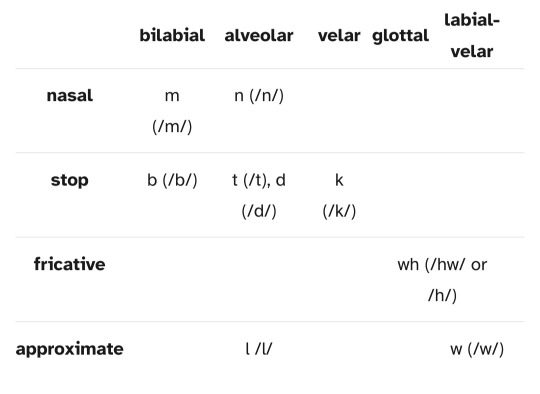

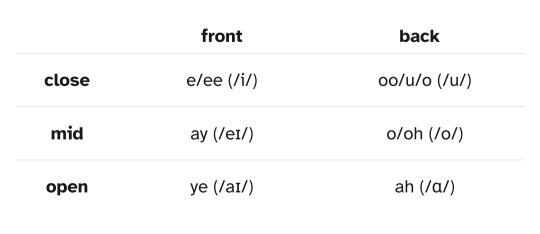

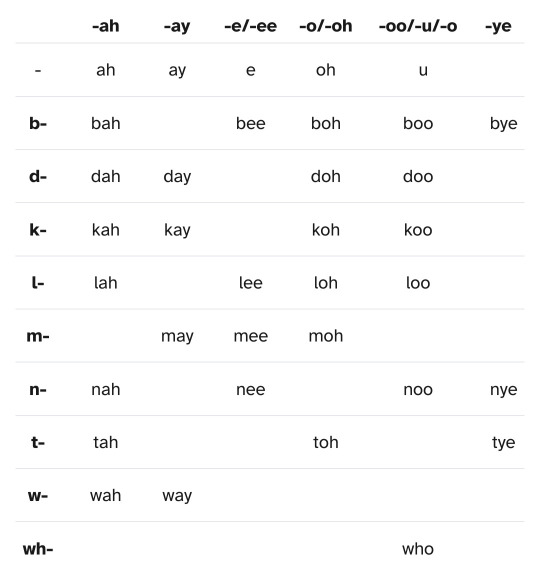

Furbish From a Linguistic Perspective

hi! if you're familiar with furbies you probably know the very short conlang (a sketch fictlang in particular) furbish! furbish is the language furbies speak before you "teach" them english by taking care of them. i will only be covering the '98 language, as the 2005 and 2010 language updates break some of the language rules the '98 version sets up, and I don't want to deal with that atm. also, do note i'm not a linguist, i just watch a lot of conlang critic

Phonology

Consonants

furbish has 9 consonants, with one digraph (wh) counting as a consonant for simplicity's sake. these consonants are /m/, /n/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, /hw/ or /h/, /l/, and /w/.

Vowels

furbish has 6 vowels (including 2 dipthongs): /i/, /u/, /eɪ/, /o/, /aɪ/, and /ɑ/.

Syllables

syllables are made up of vowels and consonants, shown in this chart. There are a total of 35 syllables in furbish.

Morphology

to make a word, syllables are put together using dashes, though some words are syllables on their own. additionally, new words can be created by putting a dash in between two existing words; like "ay-ay-lee-koo" (listen), a compound of "ay-ay" (look) and "lee-koo" (sound).

Grammar/Syntax

furbish seems to work almost the same as english grammar-wise, with a few differences. like many languages, it follows the subject–verb–object word order. for example, "i love you" would be "kah may-may u-nye". verbs have no conjugations and there are no tenses in furbish, along with there being no distinction between a singular and plural noun. most adjectives and nouns in furbish also work as verbs, and a word/phrase equivalent of "to be" does not exist. verbs have no conjugation, and adverbs go in front of the verb. it has two final particles, "doo" as a way to express that a question is being asked (similar to "ka" in japanese) and "wah" as a way to express excitement.

Proposals (Non-Canon)

i have a few proposals to make furbish a fuller language. for starters, making more syllable combinations for coining new words. secondly, a furby alphabet. each letter would represent a furbish syllable. another thing is filler words. i believe "ah" would be a great filler word, as furbies tend to say it a lot while being played with. i also suggest "doo", which could work as the furbish speaker questioning what they should say. finally, i've come up with a canon name for furbish in furbish. "kah-lee-koo", a compound of "kah" (me) and "lee-koo" (sound). roughly translated it means "my sound".

I'm autistic about furbies and conlangs fascinate me, so I had to make this!! I hope you all enjoyed :]

#furby#furbish#conlang#linguistics#conlanging#furby fandom#vurr.txt#autism off the charts#i wrote this a while ago but am JUST posting it now

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mando’a tense/aspect/mood

This is where I’m currently at with my reinterpretation of Mando’a TAM. I’m not 100% satisfied yet (there are still a number of open questions like if and how the tenses combine, how exactly should fronting the particles be interpreted, etc.) so I might continue changing things later, but I figured I’d throw this out here on the off chance of getting some opinions or thoughts. I’d especially like to hear if you think something doesn’t work.

This post is something of a continuation of this previous post about TAM systems in creole languages and how they compare to Mando’a. And obliquely this one where I lament the fact that Mando’a doesn’t have a perfective/completive aspect. But then I had the thought that many languages conflate certain tenses and aspects. Like languages typically don’t have a gazillion different tenses and moods and different particles or conjugations for each. Instead they usually have a handful of different tenses/aspects/moods that make certain salient distinctions, but conflate others. Perfect tense/aspect is maybe the most familiar example, conflating past tense and perfective/completive aspect. So instead of coming up with new tenses, I started thinking about how the canon ones work and all the different ways natural languages combine and distinguish tenses/aspects/moods.

And just to be clear, this is me thinking about possible ways to do TAM in my version of Mando’a grammar, not an analysis of canon Mando’a. My goals are to make it

at least superficially compatible with canon (i.e. to not overtly contradict the canon corpus or how Mando’a speakers have already learned to do things)

not a code for English (because that’s boring)

more fully functional grammar (that allows expressing more complicated ideas)

My current (re)interpretation is that Mando’a has five tenses (one unmarked and four marked) and four moods (one unmarked and three marked). Like many natural languages (including English), Mando’a somewhat conflates tense and aspect. TAM are expressed by preverbal particles, many of which can attach to not just verbs, but adjectives and nouns as well. They can also be fronted, and so they’re not very tightly bound to the verbs.

Tense

English tenses situate an event relative to the time of the speech act (frame of reference). When I say “I ran���, I mean I ran before the time of speaking about it just now. This is called absolute tense, i.e. it’s absolute in time. However, Mando’a tenses are relative: they situate an event relative to the frame of reference, i.e. time is relative to the topic I’m talking about, not the time when I’m talking. If I’m talking about what happened yesterday and I say “I ran”, I mean I ran before whatever happened yesterday. And if I’m talking about something that happens tomorrow and say “I ran”, I mean I will have run before whatever happens tomorrow.

Why? Because what Traviss says about Mando’a tenses (that colloquially mandos don’t use tenses and tenses were invented to deal with aruetiise) doesn’t make sense—mandos wouldn’t be making business deals with outsiders in Mando’a. However, this interpretation would produce exactly the kind of confusion with and seemingly optional usage of tenses that Traviss describes.

Present (unmarked)

The present tense is unmarked. In English, it can be translated as present or simple past, or even simple future. “I am leaving”, “I left”, and “I will leave” can all be expressed by the present tense. This is why outsiders might think Mando’a colloquially doesn’t use tenses or that tenses in Mando’a are optional.

Ni ba’slana. I am leaving.

Ni ba’slana kar’tuur. I left yesterday.

Ni ba’slana nakar’tuur. I will leave tomorrow.

The present tense can also refer to an ongoing event that is still relevant to the present moment:

Ni ratiin kar’tayli kaysh sa ruusaanyc. I have always known them to be reliable (and this is still true).

Past (ru, r)

Or technically, anterior tense or relative past. The anterior tense places the event before the frame of reference. In Mando’a, it is used for things that happened before the frame of reference or things in the past that are relevant now. The closest English translation would be “had done” or “had been doing”.

It is somewhat conflated with perfective/completive aspect. The completive aspect marks an event that is complete(d) or a past event that’s relevant to the current topic. They share at least some semantic overlap, which is how the conflation of past and perfective = perfect happens in many languages.

The relevance to the topical time could be resultative:

Ni epa tiingilar. I am eating tiingilar. Or, I ate (some) tiingilar.

vs.

Ni r’epa tiingilar vaal val olaro. I had already eaten the tiingilar when they arrived. (implication: and there was none left)

Ru’pitati. It has been raining. (implication: and it’s now wet)

Tion gar r’epa? Have you eaten yet? (Implication: are you hungry now?)

Perhaps even: Kaysh ru’nari’bat beskar’gam. He’s wearing beskar’gam, lit. “he has put on beskar’gam (and is still wearing it).”

The past tense can also express completion (especially when combined with adjectives):

Kai r’epayc. The food has been eaten up. (Implication: and there’s no food left)

Jetiise droten ru’trattoko. The Republic has fallen.

Tion gar vaabi bic? Did you do it? — Ni vaabi bic, a… I was doing it, but… vs. Ni ru’vaabi bic. I have done it. (Implication: and it is finished.)

Or an experiential sense:

Ni ru’seni. I have flown (I have done it before).

Ni r’akaani, ru’tal’onidi, ru’pir’ekulo par ibic—nu draar ba’slana ni. I have fought, worked my ass off and shed tears for this—I’m not leaving for anything.

Future (ven)

Or technically, posterior or relative future marks events that happen after the frame of reference. In Mando’a, it describes events that will happen in near future or are about to happen; future that’s relevant to the present, immediate, or known to be certain or inevitable.

It is somewhat conflated with inceptive/prospective aspect. The inceptive is the mirror of the perfect aspect: it marks a future event that is relevant to the present moment. In English, the future tense could be translated as “going to”, the inceptive as “start to”, the prospective as “about to”.

Val ven’olaro. They are coming. (Implication: they are already on their way.) / They will come. (Implication: I know they will.)

Ni ven’ba’slan’at bora. I’m about to leave for work. (Implication: so be quick about it because I’m in a hurry.)

Ni ven’kyramu gar. I’m going to kill you. (Implication: and that is a promise.)

Ven’pitati. It is starting to rain. / It will rain (soon). / It’s going to rain (later).

Vaal ni sirbu jii, gar ven’viini. When I say now, you will start running.

The future tense can also be used to express inevitable, natural or logical consequences:

Ca ven’shekemi tuur. Night will follow day.

Distant past (wer)

Something that happened long ago and is no longer relevant; something that used to be true but no longer is; also stories and myths that aren’t necessarily historical facts. Best translated as “long ago”. Rarely used, mostly in some stock expressions and storytelling.

Using wer as a distant past particle (like in wer’cuy) would nicely mirror ret as a distant future. There’s no immediately useful and logical aspect to conflate it with though, so perhaps it’s rare in everyday use.

Wer’cuy. It was ages ago. (Cuyi on it’s own beginning a sentence is translated as “there is…” or “it is…”). Also used in the sense of “once upon a time…” literally “a long time ago there was…”

Ay, ni wer borari ogir. Oh, I worked there ages ago. (Implication: and I no longer do & it’s no longer relevant to the present moment.)

Wer’cuy kih gi’ka. Gi’ka ane kihne be gise o’r ani sho’cye… Once upon a time, there was a tiny little fish. The little fish was the smallest one of all the fish in the entire sea…

Wer’cuy ni bal ner vod hiibi ibic bora—bal iba’bora… Ages ago me and my mate took this job—and what a job it was…

Wer’laar, myth, song of the eons past (lit. “eon-song” or “song of eons”)

Wer’uliik, mythosaur (lit. “long-ago beast”), the long-extinct megafauna of the planet Mandalore

Distant future (ret, re)

Far off, uncertain future; conflated with irrealis mood. Events that might or might not happen or have happened, including the far off future. Conflating these two senses (uncertainty/irrealis and far future) comes from my interpretation of Traviss’s statements about the nomadic mindset of uncertain future and canon expressions like ret’urcye mhi.

Basically mandos consider anything that isn’t imminent to be not written in stone yet. Another way to look at it would be to say they have two future tenses that are differentiated by the certainty of the event happening or the speaker’s degree of belief in it: ven for certain future, ret for uncertain future.

Ret’urcye mhi. Maybe we’ll meet again.

Ni ret slana. Maybe I will go / I could go / I would go / I might go one day.

Mood

Insert some mnemonic about 4 i’s.

Indicative (unmarked)

The unmarked tense that expresses realis mood i.e. things that are real or factual in some way.

Indicative/present tense is also used for expressing general truths:

Par ibic jorbe gar nu kyranu mando’ade, aruetii. For this reason you cannot wipe out Mandalorians, outsider.

Irrealis (ret, re)

Expresses things that aren’t known to be true. Literally “maybe, perhaps”, but can also be translated as might, could, etc. See above.

Ret ni slana. I might go.

Tion’ad ven slana? Who’s going to go? — Ret ni slana. I could go. (Or just ret ni, I could.)

Re’tracyuuri, ret’nu’tracyuuri—nu’baati ni. Shoot or don’t shoot, it’s no concern of mine. (The re’ form would be used before oral stops, I think.)

Imperative (ke, k)

Expresses commands and exhortations. Mando’a uses the direct imperative much more liberally than English—it isn’t considered rude at all.

Ke davaabi ke’gyce rol’eta resol! Execute order sixty-six!

Ke’dinui’ni paak, gedet’ye. Pass me the salt, please.

Direct commands can be very clipped:

Ke’mot! Halt! (lit. “stand!”)

Ke’serim! Take aim! (lit. “be accurate!”)

Ke buy’cese! Helmets on! (lit. “helmets!”)

The imperative can express direct commands, but it can also be used (especially in first/third persons) to express exhortation or jussive mood, similarly to English “let”, “should” or “ought”.

Ke mhi slana. Let’s go. (lit. “let us go”)

Ret mhi ke’slana. Perhaps we should go.

Ke slana, ad’ika! Go on, lad!

It can also be used to express commands to a third person. Formal imperative in third person would be common in written orders & legislation.

Ke kaysh vaabi bic. Have him do it.

Kaysh k’olaro. He should come. / He ought to come.

It’s also used in some subjunctive expressions:

Cuyi jaonyc kaysh ke’vaabi bic. It is important that he do it.

Not entirely sure if it shouldn’t be ke kaysh vaabir bic & cuyi jaonyc kaysh ke’vaabir bic… When exactly should the infinitive/conjugated verb be used is one of those unanswered questions of mine at this point.

Desiderative expressions:

(K’)Oya Mand’alor! Long live the king!

Ke’cin’ciri! Let (it) snow!

And it can be used in conditional if-then statements:

Meh ni mand’alor, ke ni toryc. If I were Mandalore, I would be just. (lit. “I should be just”)

Par cuyir rang, ke’cuyir tracyn. In order for there to be smoke, there has to be a fire.

In questions it could be translated as should:

Tion ni ke’ba’slana? Should I leave?

Fronting the imperative particle usually makes an exhortation:

Ke mhi slana. Let’s go.

Ke mhi gal’gala. Let us drink to that.

Ke kaysh olaro. Let him come.

Interrogative (tion)

Forms questions. Note that the interrogative particle doesn’t affect word order—no need to invert word order like in English.

Tion gar slana? Are you going?

Tion’ad slana? Who’s going?

Tion’vaii gar slana? Where are you going?

Tion’vaabi gar? What are you doing?

Tion’ad gar kyramu? Who did you kill?

Tion’ad nyni gar? Who hit you?

All the examples we have from canon front the interrogative particle, but I wonder if you couldn’t optionally insert it in place of the word it’s replacing in the sentence, like Mandarin does:

Gar slana tion’vaii? You’re going where?

Gar tion’vaabi? or Gar vaabi tion? What are you doing?

Gar kyramu tion’ad? You killed who?

Nominal TAM

And since Mando’a can attach verbal prefixes also to nouns, here are some nominal examples:

Riduur is your spouse, ven’riduur is the person you are going to marry and is understood to refer to a specific person and impending marriage vows. Ret’riduur however would be more like a hypothetical spouse, the person who would be your spouse if you were ever going to marry someone, or perhaps someone you haven’t discussed marriage with yet (and don’t know their answer).

Buir is your parent, dar’buir is the person who is no longer your parent, and wer’buir is your ancestor (one who you’ve never met—if you had personally known them, you’d use ba’buir or even ori’ba’buir instead).

#long post#I’ll put the rest of it in another post…#mando’a#mandoa#mando'a#mando’a language#Ranah talks mando’a#Mando’a syntax#mando’a grammar#mando’a linguistics#Mando’a tenses#Mando’a tense

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Qunlat 5/12: Nouns and Pronouns

⭅ Previous =⦾ Index ⦾= Next ⭆

Having talked about the aesthetics and phonology of Qunlat in our previous entries, we now begin diving into grammar. This will cover the basics of how nouns and pronouns work, and a special guest appearance by verbs!

Yes, I am excited about this! Grammar is one of the most fun parts of making a language for me. Prepare yourselves!

So, the first rule of thumb: Canon Qunlat’s grammar is simpler than English, or Indo-European languages in general. There are so many words and fiddly bits that these languages insist on that Qunlat does not use. This is sometimes to its detriment, and can limit what we can express in Qunlat, but it makes it easier to learn the canon.

First! There is no distinction between “the thing” and “a thing” in Qunlat. In English, ��The” is a definite article, referring to a specific object, while “a” refers to any, indefinite single object: “the cake is on a table” versus “a cake is on the table” gives you a different feel, right? The first one is a specific cake, put… somewhere table-ish. The second is an unfamiliar or generic cake sitting on a particular table.

“Sten ash noms” could mean “Sten looks for a cake” or “Sten looks for the cake”. Doesn’t matter! There are also no clearly defined words for “this” or “that”. However, we do have a potential way to get more specific, which I’ll talk about when we get to pronouns.

Many languages don’t have the distinction between “the” and “a”. Latin, Sanskrit, Japanese, Polish, and Swahili don’t have them, to name just a few. Qunlat doesn’t either. The one article Qunlat arguably does have is one we don’t talk about very often: the negative article.

“Maraas itwasit.”

“Nothing go-out.it”

“No one is going out”

Maraas is technically a pronoun in most of its uses, primarily meaning “nothing”, but it has been used flexibly enough to also be used as a negative article. Anywhere that English would say “No [noun] [verb]...” should probably use maraas in Qunlat.

Moving on to plurals, or rather, the total lack thereof: Qunlat doesn’t really distinguish between singular and plural the way most European and North African languages do. While English demands you use tide and tides, Qunlat has only one form: meraad. Even stuff that seems to imply plurality actually doesn’t: -ari as a suffix is referred to in the Fandom wiki dictionary as denoting a group, but this is inaccurate. It means either “person” or “people” depending on context. Qunari is both singular and plural–A person of the Qun, or people of the Qun. The same goes for Ashkaari, Bessrathari, Imekari, and all the rest.

There are many real life languages that lack this feature or consider it optional–hell, English has a lot of words that have no plural or no singular form. One fish, two fish, red fish, an ambiguous number of blue fish. But many parts of the language still cue you into the number: “the red fish is swimming, the blue fish are resting.” Other languages have plural and singular forms for adjectives as well. But some languages don’t care about this plural nonsense.

In particular, New Guinean and Australian languages may not have any plural noun forms, while languages like Japanese, Chinese, Korean and Malay have ways to make nouns function as plural, but don’t require them. In such cases, you’d either count the number of objects (“five friend” “五个朋友”), or use a less specific description (“many friend” “很多朋友”). Or, as long as context is clear, you don’t need those markers at all. The word for “friend” can also mean “friends”.

Qunlat, due to its small dictionary, has limited ways to do this. We have no numbers to work with. Thanks to the term Ben-Hassrath (“Heart of the Many”), we can reconstruct that rath is likely how you’d say “many”: “rath kadan” would mean “many friends”. But you don’t need to do this. You could speak about any number of friends by simply saying kadan. Does that seem vague? Well, East Asian languages get along just fine like that. But Qunlat gives us a second way to specify how many people we’re talking about: Plural pronouns!

Pronouns in Qunlat follow a very Indo-European style.

Ala - I, me Ara - you Asit - she, he, him, it, they (singular) Assam - we, us Ost - you (pural), y’all Adim - they, them (plural)

There’s a couple things to note right off the top.

First: There are no gendered third person pronouns in Qunlat. None. And there’s no distinction between a person or any other thing either, so no “it” equivalent either. This is similar to colloquial Finnish, where every single person and object can be referred to with se.

Second: There is a distinction between singular and plural “you”. Ost and ara are words the games don’t always use right. English-speakers who have no “y’all” or “ye” or “yinz” in their dialect need to be careful around this. Ara is calling one person “you”, while ost is calling two or more people “you”. They are not interchangeable. When an assassin says to Bull “Ebost Asala, Tal Vashoth!”, it’s wrong. Bull is big, but he’s not plural big. He is not two smaller tal-vasoth in a trenchcoat.

Third: There is no distinction by grammatical case–no “She” versus “her” or “I” versus “me”. English and many other Indo-European languages consider this to be absolutely essential for fluent speech: “Me looks for he” or “Him look for I” sounds wrong, it has to be “I look for him” and “he looks for me”.

In Qunlat? “Ala ash asit” and “Asit ash ala.” They do not change. The verbs also do not change–you may have noticed that it’s “I look” but “he looks”: Indo-European languages often alter the verb depending on who’s doing an action (but not always–jeg elsker deg, Norsk!).

Qunlat doesn’t really do this, but it does do something interesting.

Ala ash asit. Ashala asit.

These both mean “I look for it”. The subject of a sentence–usually the participant doing the action–can be stuck onto the end of the verb. This is a simple form of “verb person marking”. It’s a fun feature that allows Qunlat sentences to be restructured based off of what flows best.

When you want to explicitly name the subject of a sentence, you can use person marking, or not bother:

Sten ash noms. Sten ashasit noms.

Both mean “Sten looks for cake”. Simple! Flexible! …With a couple irregularities.

Dragon Age II and Philliam, a Bard! agree on one bit of irregularity to verb person marking: rather than “ebara” for “you are”, it appears to be spoken and subtitled as “ebra”. “Ebasaam” also gets rendered as “ebsaam”. The others are unchanged. However, Trespasser lists “ebasaam” in a viddathari’s conjugation practice, so I’d consider -ara and -asaam to be the “dictionary” versions of the suffixes, while -ra and -saam are used as appropriate by fluent speakers.

In one of the very first sentences of Qunlat we hear in the games, we appear to have an irregular third person pronoun: “The tide rises, the tide falls” is said as “Meraad astaarit, meraad itwasit.” This is found nowhere else in the language, it’s entirely a one-off. In WoT2, astaar appears unconjugated, indicating the original intention was that the verbs would be astaar and itwas. Either the third person pronoun would have an abbreviated form like (a)ra and (a)saam, or it would just be, well, “it”. …But given the two facts that “asit” unambiguously shows up throughout the rest of the series and is never abbreviated, and that one of English’s third person pronouns is “it”, I’m not a fan of that! I like “aarit” as an alternate form. That’s my decision, it might not be everyone’s, that’s how conlanging goes.

So, I want to demonstrate a couple of options one could take at this stage, to give you a flavor of the choices one makes while conlanging:

Aarit could be an alternate form of asit used next to certain sound combinations like “ast”, avoiding the repetition of astasit. That could make things feel better if we used any verbs ending in -s: resaarit instead of resasit, for example. We have some words that work like that in English: “a cat”, “an alligator”. Given the flexibility of -ara and -asaam, this is possible.

Alternatively, this mystery pronoun could be used to differentiate between individual things: some languages don’t just have a third person pronoun, they have a fourth person pronoun. In English, a sentence like “She looks for him, and she finds him” could mean one person finds one other, but context could change that! It could be saying “Sarah looks for Muneer, and Asli finds him”. Or it could mean “Sarah looks for Muneer, and she finds Steve.”

In our example Qunlat sentence, “meraad” is the subject for both verbs, but who’s to say the Qunari think of each tide as being the same object? They’re qualitatively different each time. Asit appears to be the default pronoun in simple contexts, but Arit may be wheeled out to refer to a first subject that might be confused with any others you intend to talk about. Complicated? Yes. Languages can be like that sometimes.

That’s what makes them fun, and makes them really fun to build. You can make something subtle and expressive using little decisions like that.

Tune in next time for verbs!

⭅ Previous =⦾ Index ⦾= Next ⭆

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conlang: Folaevesh

Vae Y' Laeza folaeden Folavesh. Na Y' Folaeden Shae' Flaerean, Temerith, Nyrv, Nyrean. Vae Y' Pomaen vy' Folaeden I am creating the language Folaevesh. It is the language of Flaerean, Temerith, Nyrv and Nyrean. I am proud of my language.

This language is for my ttrpg BloodFell and will be fleshed out and speak-able. I will leave you some of my progress here.

Phonetic Sounds:

Syntax: Folaevesh uses the SVO syntax. Words are not categorized into adjectives, verbs and nouns but rather can be used as any of them. For example, you can use Folaede, the word for mouth, as a noun when talking about a mouth as an object, as an adjective when saying someone talks alot and as a verb to describe the action of someone talking. Which one of these a word is is defined by their location in the sentence structure. here is a small selection of some words so far:

Det - [dət] - Opposite

Lae - [le] - “Bloodflow/life”

Defae - [dəle] - “Death”

Shy - [ʃai] - “many”

Fly - [fli] - “hope”

Phool - [p̪ful] - "good"

Dephool - [dəp̪ful] - "bad"

Fophool - [fɞp̪ful] - "truth"

Defophool - [dəfɞp̪ful] - "lie"

Laeph - [lep̪f] - "Animal"

Mae - [me] - “Human”

Dae - [de] - “Dwarve”

Felae - [fəle] - “Cat”

If anyone wants to comment a sentence that you want me to translate to my language go ahead!!! The prompts will help me make new words.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

「V〜方」と「V方法」の違いは何?

what’s the difference between 「V〜方」 and 「V方法」?

hi everyone! today i wanted to make a post explaining an intermediate grammar concept about the two different ways to say “way/method” with a verb in japanese! just as quick note, i won’t be glossing most of the kanji i use in this post, so be sure to use jisho or turn on rikaikun/chan if you need help reading. without further ado, 行こう!

V〜方(かた) = “how to V”

first, let’s learn how to add 〜方 to a verb:

start with plain present (dictionary) form

create 〜ます form

remove 〜ます and add 〜方

let’s try it with an ichidan verb (食べる) and a godan verb (作る).

食べる/作る

食べます/作ります

食べ方/作り方

easy, right? make sure you’re brushed up on your godan conjugation rules! now, how can we use these new forms?

first, it’s important to note that we’ve transformed the verb into a noun by adding 〜方. that means that instead of を, which attaches before verbs, V〜方 is often preceded by の.

❌ 石鹸(せっけん/soap)を作り方

⭕️ 石鹸(せっけん/soap)の作り方 = how to make soap

週末は石鹸の作り方をググって台所をひどく散らかしちゃった。 = this weekend so i googled how to make soap and made a huge mess of the kitchen.

in the above example, V〜方 refers to the actual, physical manner of doing something (in this case, making soap). you can think of it like an instruction manual or a recipe.

日本人の友達に箸の使い方を教えてもらった。 = i learned how to use chopsticks from my japanese friend.

卵の茹で方、わかってるの? = do you know how to boil eggs?

with する verbs, のし方 is used with the verbal noun. this means の is used twice in the phrase:

❌ 車の運転し方がわからない。

⭕️ 車の運転のし方がわからない。 = i don’t know how to drive a car.

pretty straightforward so far! let’s add one more thing to this topic: V〜方をする.

V〜方をする = “to V in a certain way”

this phrase is useful in describing the particular ways people perform certain actions. by using an adjective, ような, or a noun + の, you can characterize their V〜方.

林田先生は厳しい教え方をする。 = hayashida-sensei has a strict way of teaching.

誰にもわかるような書き方をした本だ。 = the book is written so anyone can understand it.

吉田くんは乱暴(らんぼう)な運転のし方をする。 = yoshida-kun has a reckless way of driving.

getting the hang of it? let’s move onto V方法 now.

V方法(ほうほう) = “a way to V”

V方法 gets a little less literal and a little more conceptual than V〜方. let’s look at how to form it.

start with plain present (dictionary) form

add 方法 to the end

that’s it—even easier than V〜方! in japanese, when you put a plain form verb before a noun, you’re kind of using that verb like an adjective; so this time, the whole phrase has become a noun phrase.

let’s see some examples of V方法:

毎日勉強することが試験に備える(そなえる)方法だと思っている人は多い。 = many people believe studying every day is the way to prepare for exams.

困難(こんなん)から逃げる方法はない場合もある。 = in some cases there is no way to escape hardship.

do you notice how the feeling here is less “instruction manual” and more “means to an end”? it’s a subtle difference, but it’s there. compare these two sentences:

この料理の食べ方は何?お箸で? = how do you eat this dish? with chopsticks?

健康を保って(たもって)食べる方法は何? = what’s a way to eat healthy?

the context for each is a little different, but the nuance of 食べ方 vs. 食べる方法 comes across clearly. the former addresses the physical manner in which a food item is eaten (see, for example, this article about okonomiyaki). the latter, on the other hand, refers to the concept of eating with a goal in mind (i.e., staying healthy). in a word, the difference is this: V〜方 implies a specific/correct way to perform an action, while V方法 expresses a method to attain some goal. make no mistake, there is some overlap between the two—but there may always be a slightly different feeling that comes with each.

and that’s that on that! just kidding, i’m sure there are way more resources out there on this topic, and it’s always a great idea to ask native speakers what they think. as always, feel free to shoot me an ask with any questions or let me know if you found any mistakes! お疲れ様 and またね!! 💮

sources:

dictionary of intermediate japanese grammar (日本語文法辞典中級編) by seiichi makino and michio tsutsui

how to use 方 by maggie sensei

some sentences adapted from jisho

113 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ciao, I have a few questions:

what is the difference between lesbica and lesbiche?

Also, if I wanted to list my pronouns (he/she/xe) in Italian, what would I say?

Which kinda a follow up- are there neopronouns in Italian?

grazie, buono giornata!

Ciao!

lesbica = lesbian, singular; lesbiche = lesbians, plural I'm leaving you a few links about the lgbtq+ vocabulary, just in case you need: Lgbtqa Vocabulary | Lgbt+ | non binary (writing)

for pronouns I suggest you to read here (and other posts in the grammar masterpost in the pronomi section, right after pronomi diretti/indiretti). Btw personal pronouns are: I = io, You = tu, He/She = egli/lui, ella/lei (there's no specific agender pronoun as far as I know but check point n.3) We = noi You = voi They = essi/loro, esse/loro The pronouns I "deleted" are the ones taught in school for declaring verbs conjugations while studying, but not much used in common language. The fact that English provides the 2 forms pronouns (eg. they/them), doesn't need to be applied in Italian too: you can simply write he=lui / she=lei / they=loro as necessary.

Italian is a pretty gendered language, every noun has its gender to which you need to conjugate articles, adjectives and sometimes other parts of speech. Eg. you wrote "buono giornata": that's grammatically wrong cause "giornata" is a feminine word, so the adjective "buono" -masculine- is not correct; you should use "buona" -feminine- -> "buona giornata". We're still kinda behind with neopronouns, so when talking it gets a bit difficult. You can call a person by their name or be formal before asking how they rather be called (formal speech needs you to use a general "Lei", which has nothing to do with the person's gender despite seeming feminine -we recognize you're being formal cause you need to use verbs at the 3rd singular person too); or you can use the noun "persona" = person. Persona is a feminine noun, but you can use it no matter the gender of the person you're talking with cause it's just the noun itself being feminine. When writing you can add an */u/ə/ä at the end of the noun, instead of the "gendering" vowel when it comes to other nouns/adjectives and so on: eg. sono alt* = I'm tall (no gender specified). You can try using "u" when talking too (eg. sono altu), I heard it once so... yeah, you can try. It really reminds me of Sardinia tbh (Regional stereotypes, sorry) but if it works... I'm no one to tell y'all otherwise. Not saying we're not working on finding a solution, but it's a tough research and translating from English, a language that has a different grammar from ours, is pretty impossible. I've been researching a bit online and I noticed that English neologisms are probably to be used in Italian as well so: “ze/hir”, “xe/xem”, “ey/em”, “ve/ver”... just go with what makes you feel better anyway. You can still explain what you mean if someone doesn't get it (it doesn't have to be a bad/rude person, it's just that is something new for many of us, especially the elders, that are not so much online or informed about this kind of pronouns/changes). BTW you can try watching tonight's show about the Diversity Media Awards, maybe you'll get some more recent news on that matter too (IDK).

Hope this helps somehow, please feel free to ask for further infos if you need!

#it#italian#langblr#italiano#italian language#italian langblr#language#languages#parole words#traduzioni#lgbtq+#vocabs#vocabulary#italian vocabs#italian vocabulary

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

My chinese listening skill may be lower than hoped ;-;

So, if I'm listening to something I already know the plot of, like an audiobook of something I've read? Then I understand bits of main plot and some chunks of details on a first listen, then all of the main plot on a second listen and some full details and some chunks, then eventually all of the main plot and many full details, and then detail understanding keeps increasing with more listens.

If it's a new audiobook? That has a plot I do not know? Then on the first listen, I understand 80%+ of the dialogues, and a ton of random chunks of details but its hit or miss whether that results in me grasping enough chunks of main plot to follow the bigger storyline. Then on a second listen, I pick up More chunks of details and some full details, usually enough to figure out the main overall plot going on. But then it will take a few more listens to grasp the full main plot information, and to understand Many full details instead of just hit or miss chunks/sentence understanding.

Basically, for first listens, I am relying super hard on the dialgoues (which are usually words I know), and key verbs and nouns (smile, drive, run, said, replied, killed, report, left, came, gives, work, school, home, when, where, why, happened, discovered, doorway, car, mom, dad, police, boss, outside, serious, relaxed, relax, case, girl, weird, bitter/painful, soft etc) and a few writing turns of phrase im very familiar with (再说,看了一眼,and just certain things like crossed their arms, nodded, stared a X, gazed at X). But since I'm catching only key words and chunks, and still getting used to the new author's word choices and sentence structurr, I am recognizing everything slower as I hear it and figuring out the basics of whats going on slower. I do eventually get the main plot... but with stuff Ive read before, I get that understanding the first time around.

Anyway. I just read some SCI, and compared it to the 1 hour I listened to yesterday and what I thought I heard. I totally did not realize 4 things were names when listening! And somehow confused Bai YuTang with his brother Bai JinTang, as if they were 1 person (i should've caught that). I also had thought Bai YuTang was the psychologist, but reading the book its Zhan Zhao so I did not hear the psychologist stuff well apparently... and I figured out a lot of places/emotions in the plot, but I also made a lot of guesses of what was going on that was wrong (I assumed in the opening bai yutang and zhan zhao were fighting in elevator, and then boss summoned them to tell the two of them to work on a case... but reading SCI it was Wang and another character in the elevator? So im not sure what happened, except maybe i was guessing some names were adjectives or something.)

Anyway. Want to practice listening? I'm listening to 木马 today! No idea what it's about, I'm making a guess its BL since bilibili recommended it to me. It's definitely a crime mystery story, because I keep picking that kind of story since I know more words in crime mystery genre. This one has chinese subtitles, if you want to practice reading too. But I'm just listening.

#rant#chinese audiobook#audiobook#october progress#progress#i am literally just catching BITS of the description and then 80% of all the dialogues. and its frustrating me so much#trying ro figure out whats going on Only from the dialogue

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

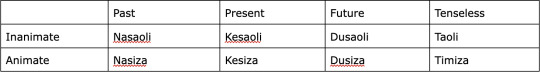

Conlang Year Days 206–258

...That's a rather long span of time. I suppose it makes sense because this post is going to cover All The Clauses. I'm not sure if this is my longest Conlang Year post (though it's probably the longest timespan), but it's a big one.

As you will see, the following sections are incredibly nonsequential. To the point where even if I weren't playing catch-up, I still would have had to wait the full fifty-three days before posting.

Days 206–212 and 252–255: Relative Clauses

Relative clauses follow the nouns they modify and are structured in the same way as full sentences, using a relative pronoun. This pronoun is always used with a case particle (similar to demonstrative pronouns) and conjugates for subjective tense.

(Note: Despite having been doing things with -iza vs. -u/oli pronouns for months, I somehow managed to swap the inanimate and animate sets of pronouns and only caught it much later. Hopefully I'm managing to catch any errors that might find their way into the examples I'm putting into this post, but...)

The verb of a relative clause is almost always left tenseless, unless its objective tense is necessary to clarify.

Koikesio ne ja siza zasi tio nasiza ne ja zacio duoko. I see the person who repaired my time machine.

Nesui tio jia gate sage natia deitei ne taoli dio jikata. The birdmeat that you wanted to eat is over here.

Relative clauses always have heads.

Kateiko sou lui keda katu tia sou taoli. I will go anywhere you go. (lit. I will go to any place that you go to.)

Days 214–222: Phrasal Modifiers

Days 215 and 219: Adposition Phrases

Adposition phrases can be as simple as an adposition phrase placed immediately after the noun they modify:

Kai tio ja siza da Kesiniju ne ki jilulu kainanu. The person from Kesiniju gave them (sg.) flowers.

In some cases, context or order makes the meaning clear—while all arguments save the subject can come in any order, placing, say, a locative argument between the subject and object would usually not happen unless it's meant to modify the subject. Of course, there can be ambiguity:

Lena tiona ja siza da Kesiniju sou ja miedegako. The person from Kesiniju came to the library. OR The person came to the library from Kesiniju.

And you can always use a relative clause to convey the same information in an unambiguous way:

Lena tiona ja siza nai timiza da Kesiniju sou ja miedegako. The person who is from Kesiniju came to the library.

Days 216–217 and 220: Active and Passive Participial Modifiers

This is not a feature present in Lecizao. Relative clauses are to be used instead.

Here's a passive relative clause, to prove that they exist:

Kitulano ne jia gate teinai tio nasaoli kao ja juoci duosia. I made the birdmeat that was eaten by your friend. (I'm looking back at my lexicon and I actually don't think kitule is supposed to mean "make" as in "create," but rather exclusively "make" as in "cause"... this can be a problem for later down the line. I'm too tired to create new vocabulary today.)

Days 218 and 221: Infinitival Modifiers

Infinitives can be placed as noun modifiers in the same manner as adjectives (i.e. after the noun). That's, ah, that's it.

Tetesio ne talouli deitei. I have many things to eat.

Days 223–224 and 235–239: Noun Clauses

My entire section on noun clauses is just a reference to the section on embedded clauses.

Clauses (with infinitive verbs) can be treated as nouns by applying a particle to them. This is something I neglected to include when first working on embedded clauses, but in retrospect makes more sense than the alternative. So that's been adjusted.

Gakani ne deisage naneju deitei ne jia gate. They (sg.) said they (sg.) wanted to eat birdmeat.

Koigano ne deitei tiona Keiti ne ja nene. I saw Katie eating the onion.

(Accusative particle underlined in both examples)

Clauses can be put under any case that makes sense. Here are examples where clauses are given nominative and instrumental marking:

Nai tio deikitule kalo naneju ne deitei tiona Keiti ne ja nene. It is wrong that they (sg.) made Katie eat the onion. (That they (sg.) made Katie eat the onion is wrong.) (Check that adjective placement!)

Lenano nalako sie naneju sou Tanu Dato kao deilio. We (excl.) came to Tanu Dato by walking.

Day 225: Subjunctives

There is no specific subjunctive marking in Lecizao.

Tenesio ne deisuonai lako dio jikata. I wish I weren't here.

Days 226, 228–229, and 231–232: Evidential Marking and Communication/Cognition

See: Embedded clauses. Again.

Sidesio ne deitei tiona Keiti ne ja nene. I know Keiti ate the onion. Gakani ciako ne deitei tiona Keiti ne ja nene. They told me Keiti ate the onion. Midani ne deitei tiona Keiti ne ja nene. They lied that Keiti ate the onion. Denano ne deitei tiona Keiti ne ja nene. I thought that Keiti ate the onion.

(Fun fact: Lecizao now has a canonical word for "onion." It's nenetono. But I've been making Katie/Keiti eat onions to show off embedded clauses for a while, and nene can cover almost all edible plant parts, including whatever an onion is [don't know nor care], and I really don't feel like going through and replacing all of them now or ever.)

Days 227, 229, 233, and 248: Conditionals and Reason/Condition Clauses

I posted part of the conditional documentation out of context a while back. Here's a condensed version of the whole thing:

Conditionals are formed in different ways depending on whether the verb is tenseless or tensed. Tenseless verbs just take a prefix ni-:

Miju tiokesi Keiti. Keiti is sleeping. Nimiju tiokesi Keiti. Keiti would be sleeping right now. (Note that there is a tense in this sentence, but it's attached to the case particle.)

Tensed verbs use an infix instead. Whenever possible, the infix is reduced simply to -n-, coming between the full verb and the reduced suffix. Otherwise (which is to say, in 3.5th and 4th person), the infix is -ni- and comes between the full verb and the suffix.

Mijesio. I am sleeping. Mijunesio. I would be sleeping. Mijusipeke. The Time Worm is sleeping. Mijunisipeke. The Time Worm would be sleeping.

Irregular verbs are treated as regular in this construction:

Neiso lako lakui. I am afraid. Nainesio lako lakui. I would be afraid. (The most literal translation of these sentences would actually be "Afraid me exists." This is how adjectives work.)

The word niu pretty straightforwardly means "if." It can be used to indicate external information that a conditional is dependent on, either before or after the conditional:

Niu neisia zunoma, mijunesio. If you were quiet (right now), I would be sleeping. Mijunesio, niu neisia zunoma. I would be sleeping if you were quiet (right now).

Or it can be used to indicate unknown information:

Nemulesio niu deimiju tio Keiti. I do not know if Keiti is sleeping.

Reason clauses are led in with the word node, and follow the clause they give reason for. As you will soon see, this is very typical.

Nemulano ne ja zeneino, node nano kui jia Kamama Taitesi. I didn’t hear about the pandemic, because I was in the Taitesi Mountains. Nemulano ne deigana nanejui, node mijano diaci kogakatia ne goduili. I didn’t know they left, because I was asleep when you said so.

Days 243–245: Clausal Coordination

I already did this.

Days 246–247, 249–251, and 256–258: Adverb Clauses

Adverb clauses are generally formed with conjunctions. There are sequential conjunctions, conjunctions for indicating time and place... and those are all the ones I've already made.

Mijano sezela tei dio gainoudu. I slept after eating in the evening. Zaseiko ne ja zacio duoko seku gana. I will repair my time machine before leaving. (Or: I will repair my time machine, and then leave.)

Mijeiko diaci konai ne la zatuiza. I will sleep when I’m dead. (lit. I will sleep when I’m a person that dies.) Nemulano ne la keni nai tio timiza daida kokimo tio ja dolo. I didn’t see a path at the start of the river. (lit. I didn’t see a path that was where the river begins. [Implying you may have seen one elsewhere]) Galani ne la degako diaci kopasi se la nulo. They read a book while sitting at a desk. (lit. They read a book when sat at a desk.)

That's it. I think. If it isn't, well, I've spent enough time on this post. If I've made a mistake on the days I'm attributing to each category, or forgotten something important, or written something particularly silly, I don't care until at least tomorrow and at most until I've managed to scrape together a full night of sleep, which at the rate I've been going might not happen for a month or several or ever.

And I'm still eleven days behind on Conlang Year and counting. Hopefully I can catch up before September en—before October st—before too long. That's a realistic goal because it cannot be defined.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

🏃♂️Suffix -하다

click the read more for a more detailed explanation :) Here's the link to our instagram post!

When you learn Korean, you may come across the word “하다” a lot. However, you may find that sometimes it works as a verb by itself while others seem combined with other words.

하다 is usually used as a verb, meaning “to do something”.

나는 매일 운동을 한다. (I exercise every day.)

나는 어제 공부를 열심히 했다. (I studied very hard yesterday)

To translate more literally word-by-word, the sentences above would look a bit more like “I do exercise every day” or “I did study very hard yesterday”.

However, you can also combine -하다 as a suffix to nouns to make various verbs and adjectives. Basically, -하다 can make nouns into something that has the quality of a verb, which can become a predicate.

Examples for -하다 verbs: 비행하다, 공부하다, 노래하다, 집중하다, 사랑하다

Examples for -하다 adjectives: 건강하다, 순수하다, 중요하다, 유용하다, 가난하다

(check the images above for each meaning and pronunciation!)

So what is the difference between a verb and an adjective in Korean? Well, adjectives, or 형용사, in Korean, aren’t very similar to adjectives in English, which usually refers to words used to describe nouns. In Korean, 형용사, or adjective describes the state or condition of the subject. If you check the meanings for the -하다 adjectives in the images above, you will notice most of them start with “to be”, which is the main difference between the verbs.

A commonly known adjective would be “예쁘다”, which means “pretty” (to be pretty). While both can be conjugated and act as predicates in a sentence there are some key grammatical differences, which is why in Korean we differentiate these two parts of speech. For example, adjectives cannot combine with the word ending -ㄴ다 (present tense ending).

Example:

나는 공부한다. (I study) (O)

나는 예쁘다 (I am pretty) (O) / 나는 예쁜다 (X)

-하다 not only combines with nouns but can also be combined with adverbs or onomatopoeic words, and sometimes other words as well. It even combines with certain dependent nouns too!

하다 as a verb also has many more meanings than just doing something, and it is an extremely versatile word. It can mean “to make” or “to dress/wear” in certain contexts, or could even refer to causation. It’s also used as another auxiliary/assistant verb (보조 동사), usually as the form -게 하다, which makes causatives(사동 표현). However, these are more advanced uses and aren’t the focus of this post, but perhaps in the future we can dive deeper into the various uses of the word “하다”.

Additionally, if you are an advanced learner and know quite a lot about Korean grammar, you may be questioning whether -하다 itself is a suffix or -하- is the suffix while -다 should be seen as a simple ending (종결어미). After all, when you conjugate -하다 words like 공부하다 into 공부하니, 공부하여, you will find that -하- is the suffix adding the new meaning while -다 is just the ending for the base form.

According to 국립국어원(the National Institute of Korean language) -하- is the suffix that makes nouns into verbs while -다 is an ending, but sometimes dictionaries such as the 표준국어대사전 mark it as -하다 (the whole) as a suffix which can be a source of confusion. Since I didn’t want to explain too much about the grammar behind the conjugation of endings, I simply referred to the suffix as -하다 in this post. Of course, this distinction does not have much use for foreigners learning Korean but may be an interesting tidbit for advanced learners or native speakers who are interested in advanced grammar!

Thank you for reading! Please leave a like and reblog if you enjoyed :)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

y’know i was thinking about it and i don’t actually know how many of my followers (if any) know what some of the pride stuff i stuff about means, so! here’s a quick post to go over a few things.

tertiary attraction - we all know about romantic and sexual (also sometimes referred to as physical, but i’m not the one to ask on whether or not these are actually the same thing) attraction. all other forms of attraction (such as platonic, aesthetic, preisen, etc.) are referred to under the large umbrella term that is tertiary attraction.

neopronouns vs xenopronouns - neopronouns, meaning ‘new pronouns’, refer to any pronouns that aren’t he/she/they/it/we/you etc. examples will be listed below. xenopronouns are pronouns that can only be explained through concepts and/or cannot be understood through human languages. i’ve seen both these definitions used in tandem for xenopronouns.

neogenders vs xenogenders - neogenders, meaning ‘new genders’, are exactly that. new genders. xenogenders are genders that can only be explained through concepts (for example, a gender connected to a specific melody or a gender connected to thorns and flowers).

neo-agabs - agab, meaning ‘assigned gender at birth’. neo-agabs are self-assigned agabs, that can be used by anyone for any reason, including no reason at all. some examples are assigned genderless at birth, assigned monster at birth, assigned dead at birth, assigned xenic at birth, etc.

types of neopronouns - these likely aren’t all of them, since i’m just going off memory here. big section ahead!

neopronouns such as xe/e/vir/thon/one etc. aren’t listed under any specific type as far as i’m aware.

noun pronouns are exactly what they sound like, though they can also include adjectives, verbs, etc. just a few examples are claw/clawself, jest/jestself, stim/stimself, screech/screechself, bug/bugself, and livid/lividself.

emoji pronouns are also self-explanatory. examples: 🦕/🦕self, 🦑/🦑self, 🤕/🤕self, and 🏳️⚧️/🏳️⚧️self.

text pronouns are anything that involves text functions. this includes emoticons and leetspeak. some examples are sh3/h1m, :D/:Dself, and ᕕ( ᐛ )ᕗ/ᕕ( ᐛ )ᕗself.

mirror pronouns are pronouns that mirror whoever one is with. for example, if you use mirror pronouns and are with someone that uses ze/she/him, then you, in that moment, use ze/she/him. if you leave and spend time with someone that uses it/gore, then you, in that moment, use it/gore.

Name pronouns are pronouns that use one’s name. For example, Creek/Creekself for someone named Creek, or Jacobi/Jacobiself for someone named Jacobi.

No pronouns are often grouped under neopronouns. some folks don’t use any pronouns.

okay, onto the next section!

aldernic - an umbrella term for folks that have, or wish to have, a body that deviates from what is expected in society or typical human notions. examples of aldernic labels: one who has or wishes to have a body that’s the ocean, one that has or wishes to have eyes with tapetum lucidum, one that has or wishes to have prismatic feathers, etc.

that’s all i can think of for now! lemme know if you’ve got questions and/or anything you think i should add

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking about how most nb people i know irl are either transfem or transmasc and use he/him or she/her as their main or only pronouns. The few people I know who go exclusively by gender neutral pronouns here are all artists who navigate mainly through queer circles - and still they face a lot of misgendering. Every space for nb people here has to be carved out of a language that does not leave space for us - and that’s thinking of pronouns only. That fact alone, though, molds so much of our identities.

There’s no understanding or respect to be gained on a larger scale, at least I can’t see it happening. I think that’s true for queer people in the whole world, of course, in a million different ways. Here, among other things, it’s about language - moreso than in many other places.

A language that genders everything leaves little space for imagining things outside of the binary, and makes people who aren’t queer (and a lot of queer people too) completely reject anything of the sort. Sometimes I feel nb people here have to be especially creative and imaginative and brave to make way for the world to fit us somehow. I imagine people feel this way all around the world, but still, it’s a lonely feeling.

Talking about me now... Ideally, I’d much prefer to use gender neutral pronouns only, but they change so much of the language it’s too overwhelming. It’s nouns, adjectives, verbs. Whole sentences are suddenly different and new and changed and I can barely think of opening myself up to anyway - I can’t deal with it all. I don’t want to announce my uncomformity in every word I use, I don’t want that to be in the first and last word I exchange with people.

With time, I’ve understood, or decided, that being all and being nothing can be almost the same to me, when it comes to language. What matters is the incapturability. In deciding to use all pronouns, I face that I won’t be understood or perceived as I am (which is, again, a fact of life for everyone, but which seems to sting so hard here). I can be a lot of things to so many people, and none of those facets are lies. They’re more or less whole, but not exactly untrue, never. I can pretend to be like water, and that all places recognize some part of me, somehow, even when I’m treated badly... I’m not water, though, I’m flesh and bone. There’s no total satisfaction to be felt here, I can only try.

I wonder if other people from here feel similarly. I get the impression that they do - even if my experiences and that makes sense to be comes from this body who is still well accepted most places I pass through in life (from being white, and skinny and my looks easily dismissed as “cute” or “boyish” from people who’d frown at gnc people normally).

#just saying v basic stuff that i'm thinking about constantly#it's hard#i think part of why ive grown so much more reclusive (not really but more) is the separation i got from coming to terms with myself#in a country that isn't welcoming in any way#for me#and that includes my so called friend groups who are all made of lgb people who mock gender neutral language all the time#sigh#and also there's the career and academy i got to built and how i cld never come out as nb rn and find employment#oh well#é a vida#life in the swamp

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

English pronouns have had some interesting developments over the past few centuries

In the second person, the old singular thou has been lost almost entirely (there's apparently still a few dialects that preserve it, and of course it retains some religious use), and the old plural you is developing a specifically singular meaning in many dialects, while in others it remains non-number-specific. But even in many dialects where you can be used regardless of numbers, a specifically plural form has arisen, with different dialects coming up with different terms, such as y'all, youse, yinz, you guys, you folks, etc. It seems quite likely that this development will continue and a future stage of English will be left with you being specifically singular and some other form as a plural. The only real question is whether one of the competing dialectal forms will win out in all dialects, or whether there'll remain dialectal variation in the 2nd person plural (both are plausible scenarios I think)

In the third person, they has recently acquired a use as a singular specific pronoun. It has long had a singular indefinite usage going all the way back to Middle English - that is, being used to refer to an unknown or unspecified individual (e.g., "someone left their umbrella behind"), but it's recently come to be used to refer to a specific known individual. I've even heard some people using they as a general-use pronoun, including for cis people and animals. It's conceivable - though by no means certain! - that it will eventually replace he and she, and future English will have two 3rd person singular pronouns - an animate pronoun they and an inanimate pronoun it. This leaves the 3rd person plural without a dedicated pronoun, so I suspect that, similar to the 2nd person plural, some form of new plural will develop. My guess as to what would be the most likely development is those ones (possibly shortened to just those or some other contraction like "those-uns" or "tho'nes" or something) being extended to personal use, but other possibilities exist (conceivably even something like they-all → th'all by analogy with y'all)

I also wonder if agreement might change in the future with singular they. At present singular they still takes plural verb agreement - they are not they is, despite singular nouns and other third-person singular pronouns (including neopronouns like xe!) take the singular. It seems probable to me that singular agreement might, at some point, come to be used with singular they, so that future generations might happily say "they is" for singular they, just as "themself" has come to be accepted for many speakers

(Side note: I would love to read a study of child language acquisition focusing on singular they and verbal agreement - there are plenty of families today where children are growing up with a parent or other relative or close family friend who uses singular they, I would be fascinated to see if children in such contexts have difficulty using plural agreement with singular they)

The 1st person, meanwhile, has been pretty stable in most dialects since the Old English period, with only changes in pronunciation and the loss of the OE dual, and there's no reason to suspect that that will change anytime soon (especially outside of any broader changes like loss of case distinctions in pronouns in general - which has happened in some dialects already!) (there are some specific contexts where "we" is used in place of "I" or "you", but I don't see that being likely to spread outside of those contexts)

I suspect that future linguists will describe these changes in the pronoun system as a characteristic of what we now call Modern English (which they'll presumably give some other label to), perhaps even using the conclusion of that process to define the cutoff between our stage of English and the next stage. Middle English saw the loss of grammatical gender, adjective agreement, and the near-complete loss of the case system outside of pronouns, while Modern English saw the loss of the old 2nd and 3rd person (animate) singular pronouns and the replacement of the old male-female-inanimate distinction with a new animate-inanimate distinction, along with the development of new 2nd and 3rd person plural pronouns

6 notes

·

View notes