#smithsonian conservation biology institute

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

National Zoo's Cheetah Cubs Go Outside for the First Time by Smithsonian's National Zoo Via Flickr:

#Species: jubatus#Genus: Acinonyx#Family: Felidae#Order: Carnivora#Class: Mammalia#Phylum: Chordata#Kingdom: Animalia#Cubs#SCBI#CRC#Front Royal#VA#USA#Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute#National Zoo#cheetah cubs#cheetah#Zazi#Amani#cross-foster#flickr

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Once thought to be extinct, black-footed ferrets are the only ferret native to North America, and are making a comeback, thanks to the tireless efforts of conservationists.

Captive breeding, habitat restoration, and wildlife reintegration have all played a major role in bringing populations into the hundreds after near total extinction.

But one other key development has been genetic cloning.

In April [2024], the United States Fish and Wildlife Service announced the cloning of two black-footed ferrets from preserved tissue samples, the second and third ferret clones in history, following the birth of the first clone in December 2020.

Cloning is a tactic to preserve the health of species, as all living black-footed ferrets come from just seven wild-caught descendants. This means their genetic diversity is extremely limited and opens them up to greater risks of disease and genetic abnormalities.

Now, a new breakthrough has been made.

Antonia, a black-footed ferret cloned from the DNA of a ferret that lived in the 1980s has successfully birthed two healthy kits of her own: Sibert and Red Cloud.

These babies mark the first successful live births from a cloned endangered species — and is a milestone for the country’s ferret recovery program.

The kits are now three months old, and mother Antonia is helping to raise them — and expand their gene pool.

In fact, Antonia’s offspring have three times the genetic diversity of any other living ferrets that have come from the original seven ancestors.

Researchers believe that expanded genetic diversity could help grow the ferrets’ population and help prime them to recover from ongoing diseases that have been massively detrimental to the species, including sylvatic plague and canine distemper.

“The successful breeding and subsequent birth of Antonia's kits marks a major milestone in endangered species conservation,” said Paul Marinari, senior curator at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute.

“The many partners in the Black-footed Ferret Recovery Program continue their innovative and inspirational efforts to save this species and be a model for other conservation programs across the globe.”

Antonia actually gave birth to three kits, after mating with Urchin, a 3-year-old male ferret. One of the three kits passed away shortly after birth, but one male and one female are in good health and meeting developmental milestones, according to the Smithsonian.

Mom and babies will remain at the facility for further research, with no plans to release them into the wild.

According to the Colorado Sun, another cloned ferret, Noreen, is also a potential mom in the cloning-breeding program. The original cloned ferret, Elizabeth Ann, is doing well at the recovery program in Colorado, but does not have the capabilities to breed.

Antonia, who was cloned using the DNA of a black-footed ferret named Willa, has now solidified Willa’s place as the eighth founding ancestor of all current living ferrets.

“By doing this, we’ve actually added an eighth founder,” said Tina Jackson, black-footed ferret recovery coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in an interview with the Colorado Sun.

“And in some ways that may not sound like a lot, but in this genetic world, that is huge.”

Along with the USFWS and Smithsonian, conservation organization Revive & Restore has also enabled the use of biotechnologies in conservation practice. Co-founder and executive director Ryan Phelan is thrilled to welcome these two new kits to the black-footed ferret family.

“For the first time, we can definitively say that cloning contributed meaningful genetic variation back into a breeding population,” he said in a statement.

“As these kits move forward in the breeding program, the impact of this work will multiply, building a more robust and resilient population over time.”"

-via GoodGoodGood, November 4, 2024

#ferret#ferrets#mustelid#black footed ferret#conservation#endangered species#conservation biology#biodiversity crisis#dna#genetics#cloning#good news#hope#hope posting#hopecore#hopepunk

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Walnut the Crane dead at 42

White-naped Crane Walnut and her keeper/husband, Chris Crowe, in 2021. (Photo: Roshan Patel via NZCBI)

Internet sensation Walnut the Crane became ill on January 2, 2024 and passed away at age 42 at her home at the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute (NZCBI) campus in Front Royal, VA. A necropsy revealed the cause of death to be renal failure. Walnut far outlived the average life expectancy for White-naped Cranes in captivity, which is 15 years. She leaves behind her husband, zookeeper Chris Crowe, with whom she had 8 offspring, including two housed at the NZCBI: daughter Brenda, age 18, and a granddaughter, age 1.

“Walnut was a unique individual with a vivacious personality,” Crowe said. “She was always confident in expressing herself, an eager and excellent dancer, and stoic in the face of life’s challenges. I’ll always be grateful for her bond with me. Walnut’s extraordinary story has helped bring attention to her vulnerable species’ plight.” (x)

White-naped Cranes are native to Mongolia, northeast China and southeast Russia, wintering in the Korean DMZ, Japan, and China. Habitat loss to agriculture, development, and ongoing droughts are factors in their decline, leaving them classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN. Walnut was an important contributor to efforts to restore the species.

Edit: for those unaware, I refer to the zookeeper as her husband because Walnut was imprinted on humans, meaning she considered him her mate and performed displays and courtship for him. As a zookeeper he was responsible for artificially inseminating the bird. This and more was the source of her viral fame.

#walnut the crane#conservation#crane husband#birds#white-naped crane#smithsonian#I visited the NZCBI last year and could hear various crane calling on campus

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Abaia

Imagine, if you will, that you’ve gone on a quiet vacation to the islands of Fiji. Feel the sand under your toes, the sun on your skin, the smell of saltwater. You take an excursion, and find a beautiful, deep lake, surrounded by lush greenery. It’s a sweltering day, and the lake looks so inviting.

You walk into the lake, the cool water stinging pleasantly as you go deeper. Eventually you’re floating, unable to feel the ground beneath you. It’s calm, soothing. The local birds sing, the breeze rustles the leaves… you’re relaxed enough to let your eyes close and just drift…

Your feet touch a slippery rock, slick with grime from centuries of being submerged. You pay it no mind… until you notice the layer of grime is thick enough to give, making the rock feel almost squishy. You open your eyes. The birds have stopped singing.

You realize that you aren’t touching the rocking. It’s touching you.

The Abaia. A massive eel of Melanesian mythology, said to live at the bottom of freshwater lakes. The legend comes from the Fiji, Vanuatu, and Solomon Islands, though the exact location varies. There’s not really a specific size given, but, for an idea of what we’re talking about, the average American Eel is 16-33 inches long and about 2.5 pounds. So… bigger than that. Much bigger.

The legend of the Abaia poses it as the guardian of the lake it dwells in, protecting the inhabitants from humans looking to harm them. If a fisherman were to try and get his daily catch from the lake, or if an ignorant tourist were to throw their trash in it, the Abaia will unleash its wrath. Thrashing and twisting, it causes impressive waves that will claim the life of the perpetrator, dragging them down to the depths to remain with the great eel.

There is another version of this legend that claims the Abaia holds control over the weather via magic. The story goes that a fisherman discovered a bountiful lake, full of critters and creatures to sate his village’s hunger. He led the village to this lake, and has them help plunder it of life. The Abaia, upon seeing this, causes a torrential rainstorm, wiping out the village and drowning everyone who had harmed the creatures. The Abaia is often depicted as a motherly being to the inhabitants that share its home.

As someone who knows the basics about various eels, I have to wonder if there is some electrical aspect to this creature. Perhaps its ability to cause storms is caused by a powerful electrical charge. According to the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, the Electric Eel has three organs — the main organ, the Sach’s organ, and the Hunter’s organ — that produce electric impulses used for defense, communication, navigation, and hunting. At 6-8 feet long, this eel can generate up to 800 volts of electricity. Is the Abaia electric? Being so massive in size, could its electrical shock cause a storm? It’s unlikely, yes, but an interesting thought to consider.

#nox hawthorne#writers on tumblr#writing#writer#writeblr#art#artist#artists on tumblr#misc writing#artwork#cryptids#creature feature friday#Abaia

785 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Fascinating Facts About the Arapaima, the Largest Freshwater Fish in South America

This keystone species of the Amazon River ecosystem are a fearsome predator with many names.

Reaching up to 10 feet (3 meters) long and weighing 440 pounds (200 kilograms), arapaima are the largest freshwater fish in South America—and an important species in the Amazon River ecosystem. Learn about these jungle giants before you encounter them at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. 1. They are top predators in their environment. 2. Arapaima breathe air. 3. They’re an ancient species...

Read more: Ten Fascinating Facts About the Arapaima, the Largest Freshwater Fish in South America | Smithsonian Voices

#arapaima#fish#bony fish#ichthyology#amazon#rivers#freshwater#aquatic#animals#nature#science#south america

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Giant Salamander (Andrias japonicus), young adult, family Cryptobranchidae, endemic to Japan

One of the largest amphibians in the world, this huge salamander grows up to a length of ~5 ft.

Photographs via: Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute

#andria#giant salamander#salamander#cryptobranchidae#andrias#amphibian#herpetology#animals#nature#japan#asia

342 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Animal News today; Walnut the White-naped Crane has passed naturally of old age. She contributed eight chicks to her species’ survival.

I hope Chris Crowe will recover from losing his crane wife with time

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also the hunting for their skin and others!

It's January 31st, 🦓 International Zebra Day. Zebras live in 🌍 Africa in many different habitats, including savannas, mountains, woodlands, and hills. As you undoubtedly suspected, Zebras are members of the 🐴 Horse family, the genus Equus. There are three species of Zebra - Plain’s Zebra, Mountain Zebra, and Grevy’s Zebra. Each has a distinct pattern of alternating black and white stripes.

Why do Zebras have stripes? Believe it or not, scientists still aren't sure. Many theories exist, though. Stripes might provide camouflage in tall grass, especially at night. The stripes on a herd of Zebras might also confuse 🦁 predators because it can be difficult to tell where one Zebra ends and another begins. Or Zebras may use their stripes to identify each other as, like with human fingerprints, each Zebra's stripe pattern is unique. In addition, it's been proven that the alternating black and white pattern of Zebra stripes helps control 🌡️ body temperature, plus deters 🦟 biting flies from landing. It could very well be that all of these factors play a part in the natural selection of stripes for Zebras.

Are Zebras black with white stripes, or white with black stripes? In its mother's womb, each Zebra starts out black, and the white coloration develops there, while still in the womb.

There've been many attempts to tame Zebras, but their unpredictable nature makes this difficult. However, in 1907, Kenyan Doctor Rosendo Ribeiro regularly rode his tame Zebra to his patients' homes.

The populations of all three Zebra species are declining. The most threatened is Grevy's Zebra, whose population has decreased 54% over the past 30 years. The main culprits in this case do not include the usual suspect, climate change, but are habitat loss, poaching (for their pelts), and hunting (for bushmeat). The 🗽 Smithsonian Institution's 🐼 National Zoo and 🟩 Conservation Biology Institute founded International Zebra Day to help raise awareness of the Zebras' plight and help encourage efforts to preserve and protect them and their habitats. ☮️Peace… Jamiese of Pixoplanet

#International Zebra Day#Zebra Day#World Zebra Day#Day Of The Zebra#Africa#Smithsonian#Smithsonian Institution#National Zoo#Conservation Biology Institute#Animal Conservation#Wildlife Safari#zebras#zebra#horses#horse#bushmeat#hunting#poaching#habitat loss#animals like us#we're all one#be kind to all kind#be kind to all kinds

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

I dont know if it’s something youve been asked before, and i dont know how to really phrase my thoughts. But whats it like working in like environmental things well disabled? Have you met many, or any, other disabled people in the field? I’m 16, and ever since I was little I’ve had so much passion for environmental education in particular, and it was a field I wanted to go into for a long time. Sadly it seems like my body has other plans, I’m currently at a point where I might have to drop out of highschool because managing class and disability is too much, and so college feels impossible. And when it was mostly mental stuff I had thought about maybe joining americorps or something because it looked like they’ll take people with a ged and then I could still do work I care about, but I’ve only ever met one physically disabled person doing anything related to the environment and stuff (there’s a person with leg braces and a service dog who works at the local aquarium) so I never really get a chance to ask about this stuff

so idk, sorry if I’m rambling a lot and hard to understand. If it makes you feel any better I’ve cornered every environmental educator I’ve met the last year or so (and I go to a project based environmental charter school thing, so I meet a lot) and asked them a lot of questions too. Especially since my school encourages us to think about future careers and what skills we need

so idk, I want to know. What’s it like? Is it hard? What did you have to do to get the job you have now? Do you regret it, would you choose something different if you could go back? Do you have any advice?

I hope you’re having an ok day, and that I’m not too annoying, and thank you if you even took the time to read this far. -🌱

no no don't apologize, this is exactly what this blog is for. When I started my journey I couldn't find any outspoken disabled environmentalists or any resources for people like us. So I started this blog to compile resources and share what I've learned as my career has progressed. I want everyone regardless of physical or mental state to be able to pursue their passions in environmental science and conservation.

Honestly, this field has a long way to go still. Even big institutions like the Smithsonian haven't quite figured it out yet. But there is definitely a shift happening. I've been seeing so many more disabled young people interested in this field and its amazing. I saw another physically disabled student at the Smithsonian conservation biology institute when I visited as an alum a few weeks ago, and I believe I was one of if not the first person to attend as a wheelchair user (yeah they didn't know what to do with me 😮💨) I had a professor who directly singled me out for being a wheelchair user so you will unfortunately run into some bigots in this field.

However the federal government (im assuming you are in the US so apologies if you're not) especially during the Biden administration has been ramping up its hiring of Schedule A employees. Schedule A allows you to circumvent the competitive process through the WRP (workplace recruitment program) once you've graduated college (or GED). Schedule A can be provided by a doctor or disability counselor (My DARS office did mine, love DARS: it's free and every state has one). My manager is HOH as well as one of my new coworkers and I was of course recently hired by the EPA as well. The EPA is probably the most disability friendly place to work in our field, if not anywhere. It has its issues but I've been pretty much over-accommodated instead of under (sad I consider the minimum accommodations to feel excessive).

Here's some of the things I've learned so far:

1. My biggest advice to anyone your age wanting to get into this field is to volunteer volunteer volunteer!! You are most likely at a time where you can afford to work for free. Most environmental internships are unpaid unless you have prior experience with the organization. Try out a bunch of different experiences to find out what you like the most. I never would have thought I'd be a bug person until I did my first invertebrate stream assessment. I got into environmental science late in my college career so it took me a lot longer to figure out what I wanted to do. Get as much experience as you can while you are still supported by your parents and don't have to worry about things like rent or bills. Some organizations are trying to change this so people from lower incomes can still have the same opportunities, but it still has a ways to go. Notably zookeepers have to work either for free or for dirt cheap for a couple years before they get hired full time.

2. Be prepared to lose out on your dream job due to your disability(s). I'm going to be frank and not spout any of that "you can do anything you put your mind to" bullshit. Yes, most things CAN be done by anyone with the right accommodations, but in a field where a large percentage of the work is done physically, you will be unable to do some types of jobs. I'm not saying it's impossible to get your dream job with disabilities, but it's a very common experience for us. For example, I looked into working on a boat. In a perfect world, I'd be given limitless accommodations and time to rest but on a boat that is extremely difficult. You can't take sick days whenever you need them. This was the same thing I had to realize when I was offered my dream job in my dream location: A stream specialist field technician for the USGS in Portland Oregon. I absolutely loved working in the field, and yes there are many of us who do/did fieldwork using mobility aids. I miss fieldwork everyday. But I had to turn it down. I knew deep down I couldn't handle it, having scheduled in advance field excursions that I couldn't postpone, having to hike in difficult terrain in remote locations, even moving across the entire country, at least at the time, was improbable. I was barely holding on at my field job where I did have safety nets. I just couldn't justify the financial and physical strain as well as the risk if I wasn't able to do the job and became unemployed. It broke my heart to give it up and I'm still grieving. But I do enjoy my current job and it lets me prioritize my health. No longer do I just work and sleep because work would take up all my spoons. I've been drawing and gaming and spending more time with loved ones. It is an unfortunate fact of life that sometimes what we want isn't what we need. Being disabled means that sometimes we have to make hard decisions that abled people don't ever have to think about. It's part of the grieving process for those of us who were abled at some point. I can't speak on what it's like for those with lifelong disabilities from birth, but I know its hard for them too.

3. Ok yeah 2 was a huge bummer, but here's where it gets better: When one door with stairs closes, a door with a ramp opens. There will be other opportunities. This field isn't just fieldwork despite what most people think. You don't have to be a super strong ranger that can hike 20 miles in a day without breaking a sweat to do environmental work. The field needs people who take what the guys outside collect and analyze it, research it, visualize it, present on it, take care of it, write about it, archive it, make art of it, etc etc etc. There are so many organizations that need people who can do data analysis and administration. Working at a desk doesn't make you less of an environmentalist. Plus that's not all, you can work in a lab or work with smaller creatures like bugs or herps or fish or you could do botany or geology! You don't need to be able to go out and get them yourself to work with them. Being able to save energy during my workday allows me to pursue my passions like collecting bugs and swimming. I can volunteer with citizen science projects or conservation orgs and still do fieldwork, but because its not a job I can do it when I feel up to it, I don't have to push myself to keep going because I'm worried about being fired. I currently work as a data analyst for the EPA and I work mostly from home so I can do my work without suffering. Yea data analysis isn't my favorite thing in the world but your job doesn't have to be. Sometimes a job is something that makes you money so you can do your passions outside of it. But I am happy the work I do supports something I am passionate about (supporting states so they can clean up more sites and thus have cleaner water).

4. You'll have to learn how to advocate for yourself. Push against boundaries. Explore your options. Especially with doctors. You know yourself best, don't let anyone else define your boundaries for you, even me. If someone says you can't do something because of your disability, but you know that you actually can, tell them and be assertive about it. Many of us are seen as abrasive and rude, but to be a disabled person in a very abled centered world you gotta be. Don't let anyone hold you back because THEY feel uncomfortable. My coworkers at my old job were worried for me when I showed up to work with my crutches for the first time. But it actually made me BETTER at stream assessments (having four legs means you don't slip as much). I could do it even if I needed to take breaks and use mobility aids. Nowadays it's too much for me to be doing that but at the time it was within my limits. And sometimes, you'll overestimate yourself and end up flaring or hurting yourself. It's okay to make mistakes, it doesn't make you a bad person. At first you'll push through too much but as you learn your body's limits you'll get better at managing your disability. And sometimes a great memory is worth a week-long flare up. Its for YOU to decide what you can do.

That's all I can think of for now, I should probably get ready for bed soon. But just remember, there are more of us than they think and we can be capable, productive, and a benefit to the environmental movement no matter our ability or skills.

If you have anymore specific questions, or just need to talk, I'm always available (even if I might take a while to reply).

#wrenfea.ask#environmental science#field technician#from the field#chronic disability#chronic pain#spoonie#disability#chronic illness#physical disability#neurodivergence#working while disabled#I've been thinking about creating a Tumblr community since I just got the ability to#what do yall think?

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cloned ferret gives birth in Va., making history, U.S. officials say. (Washington Post)

Antonia, a cloned black-footed ferret, gave birth to kits in June. They are seen at 3 weeks old on July 9 at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Virginia. (Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute)

Excerpt from this Washington Post story:

An endangered animal that was created by cloning gave birth to two healthy offspring at a Smithsonian Institution/National Zoo center in Virginia, in what a federal agency called a conservation milestone.

Authorities indicated that techniques used in their work with black-footed ferrets could help preserve other endangered species.

The two ferrets were born in June to a cloned mother at the Smithsonian National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Virginia.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service called it an exciting research achievement that broke new ground in efforts to preserve the animals. The work could also help in preserving other endangered species, animal specialists said.

The cloned ferret mother, Antonia, gave birth after mating with a male ferret named Urchin, the federal wildlife agency announced last week. Antonia was born last year, created from preserved genetic material from Willa, a female ferret that died in 1988 without descendants.

Cloning provided the opportunity to bring the genes of an eighth “founder” into the existing ferret population, according to Revive & Restore, one of several organizations involved in the ferret project.

Antonia was described as the first cloned ferret to restore lost genetic variation to its species. One of her kits died, but two survived. Sibert is a female and Red Cloud is a male.

They are “doing well,” said Revive & Restore.

Their birth represented “a critical step forward” in the use of the cloning process to produce greater genetic diversity in conservation, the wildlife agency said.

Genetic diversity is vital to the healthy, long-term recovery of an endangered species, the wildlife agency said, and the cloned ferret mother showed three times the genetic diversity of the current population of endangered ferrets.

23 notes

·

View notes

Video

Extremely Rare Guam Rails Hatch at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo by Smithsonian's National Zoo Via Flickr: Photo Credit: Jim and Pam Jenkins, FONZ Photo Club As Washington, D.C.’s unseasonably warm winter turns into spring, a baby boom is underway at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. Two Guam rail (Gallirallus owstoni) chicks hatched March 3 and 4; they join six others in the Zoo’s collection—three of which live at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Va. This brings the total population of these small, flightless birds to 162 individuals. Each hatching is significant—the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists these birds as extinct in the wild. In about six weeks, keepers will separate the chicks from their parents, and Zoo veterinarians will perform a routine medical exam and take feather samples to determine their sexes. To date, 82 chicks have hatched at the Zoo and SCBI, and each provides scientists with the opportunity to learn about the growth, reproduction, health and behavior of the species. The Zoo sent 29 Guam rails to the government of Guam for release and breeding, and an additional 25 birds have gone to other institutions to breed. Guam rails flourished in Guam’s limestone forests and coconut plantations until the arrival of the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis), an invasive species that stowed away in military equipment shipped from New Guinea after World War II. Because these reptiles had no natural predators on Guam, their numbers grew and they spread across the island quickly. Within three decades, they hunted Guam rails and eight other bird species to the brink of extinction. In 1986, Guam’s Department of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources captured the country’s remaining 21 Guam rails and sent them to zoological institutions around the globe—including the National Zoo—as a hedge against extinction. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums created a Species Survival Plan for the birds. The SSP pairs males and females in order to maintain a genetically diverse and self-sustaining population. Today, 118 Guam rails are thriving on two islands near the mainland: Rota and Cocos. The availability of release sites continues to shrink, however, due to deforestation and human expansion. Controlling the brown snake population remains a significant challenge as well, though researchers have made progress in developing a variety of barriers, traps and toxicants. Forty-four birds reside in zoos and other facilities in North America. Visitors to the Smithsonian’s National Zoo can see these birds on exhibit in the Bird House. In stark contrast to their brown-and-white-plumaged parents, Guam rail chicks sport black downy feathers. nationalzoo.si.edu/Animals/Birds/

#Guam rail#bird#national zoo#smithsonian#rare#endangered#Gallirallus owstoni#washington#D.C.#FONZ#flickr

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Black-footed ferrets are North America’s only native ferret species and were thought to be extinct in 1979.

When the species was miraculously rediscovered in 1981 in Wyoming, these long, quirky mammals quickly rose to become the center of dedicated conservation efforts.

At that time, the Wyoming Game Department and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services brought 18 ferrets into human care to begin cooperative breeding programs, like the one at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Virginia.

Between captive breeding, wildlife reintroductions, habitat restoration, and even genetic cloning, one of the continent's most endangered mammals is now seeing a comeback.

Perhaps the cutest manifestation of this conservation work is a new litter, born at the NZCBI on May 11.

Since 1989, 1,218 black-footed ferret kits have been born at NZCBI, with 750 reintroduced to the wild. Currently, 48 ferrets live at NZCBI, including one-year-old female Aristides, who gave birth to the new litter of six kits last week.

Last breeding season, NZCBI raised 51 ferret kits. Now with 2024’s season underway, animal care staff are closely monitoring the ferrets’ behavior through the institute’s Black-Footed Ferret Cam (a temporary live webcam the public can also view on the NZCBI website)...

Right now, the kits are still tiny, weighing less than 10 grams, with a thin layer of white fur covering their bodies. Their well-known mask-like markings and namesake dark feet will appear in the next few weeks. Then, they’ll start venturing out of their den and exploring the burrows of their habitat, akin to the tunnels they’d find in the wild."

-via GoodGoodGood, May 21, 2024

#endangered species#ferret#ferrets#black footed ferret#united states#conservation#conservation news#baby animals#good news#hope

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

We've lost an icon and a legend :(

WASHINGTON -- One of the great interspecies love stories of our time has come to an end.

Walnut, a white-naped crane and internet celebrity, has passed away at age 42. She is survived by eight chicks, the loving staff at the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, and by Chris Crowe, a human zookeeper whom Walnut regarded as her mate for nearly 20 years.

“Walnut was a unique individual with a vivacious personality,” Crowe said, in a statement released by the National Zoo. “I’ll always be grateful for her bond with me.”

... “She was always confident in expressing herself, an eager and excellent dancer, and stoic in the face of life’s challenges," Crowe said. "Walnut’s extraordinary story has helped bring attention to her vulnerable species’ plight. I hope that everyone who was touched by her story understands that her species’ survival depends on our ability and desire to protect wetland habitats."

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

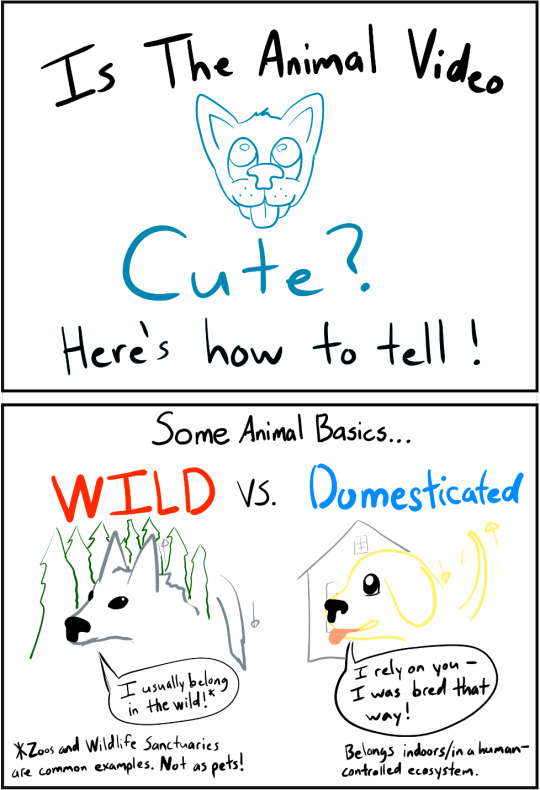

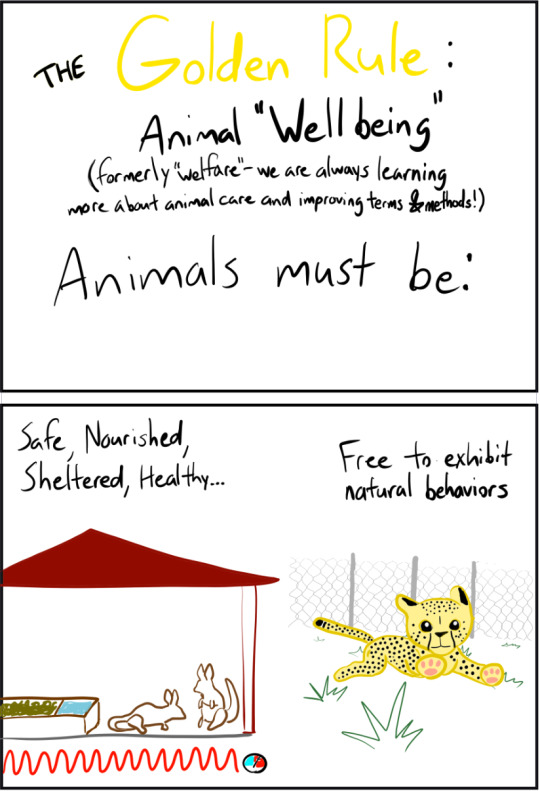

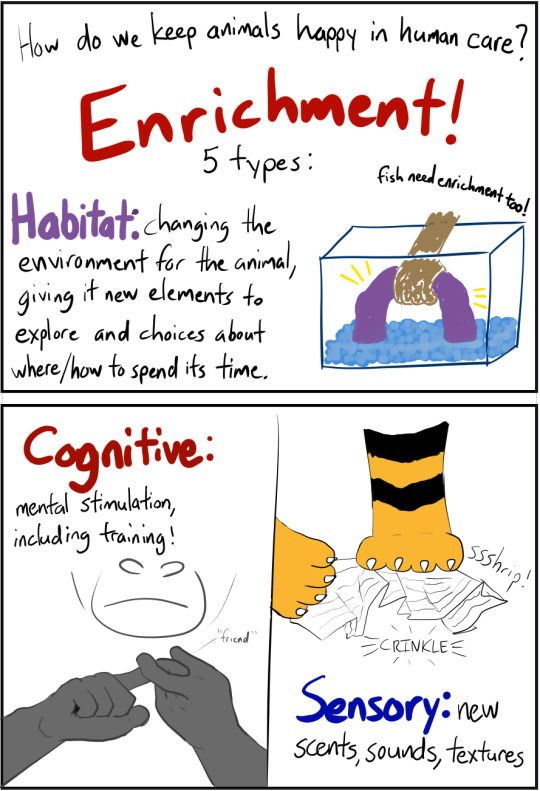

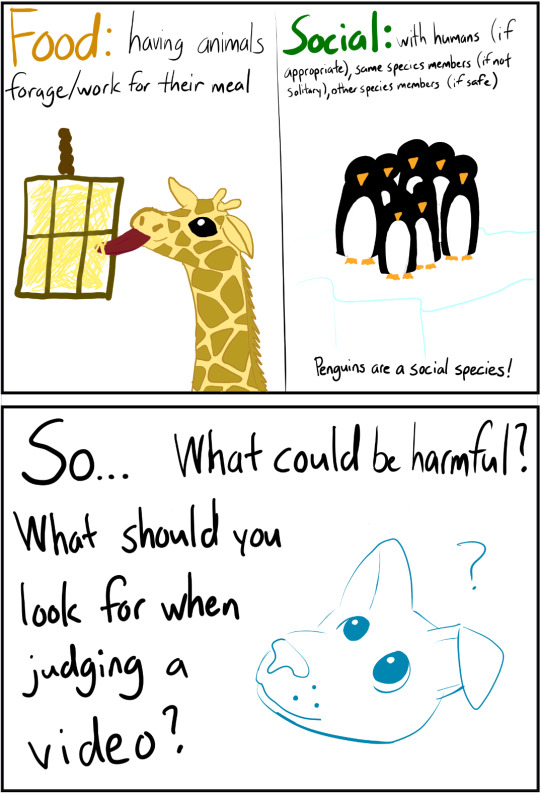

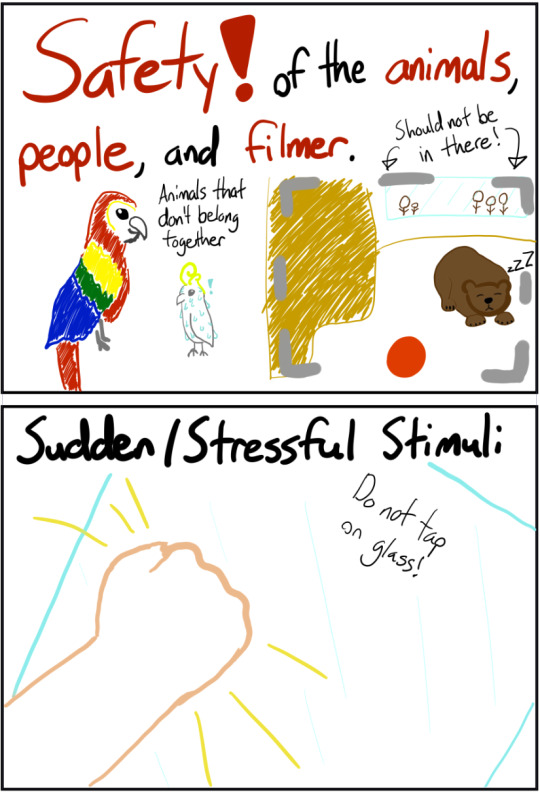

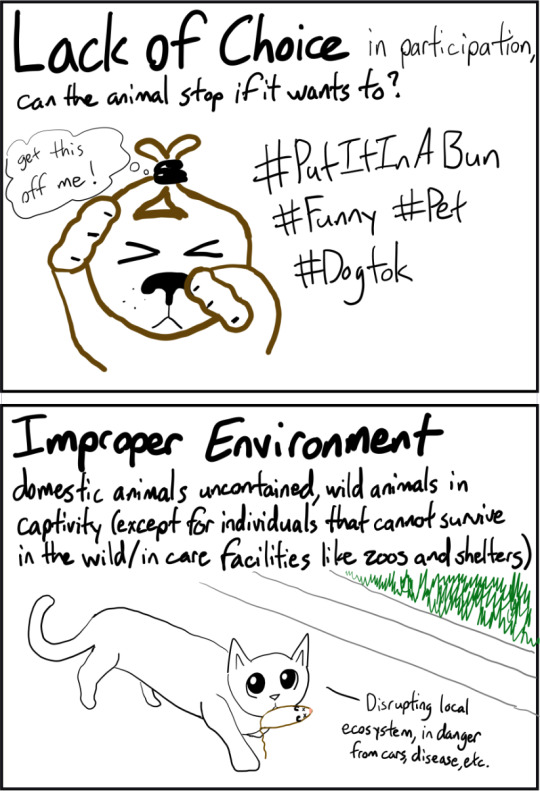

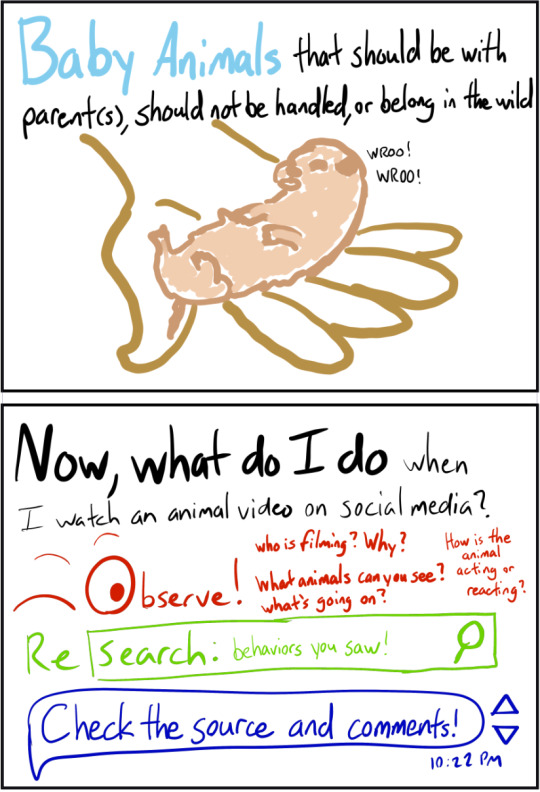

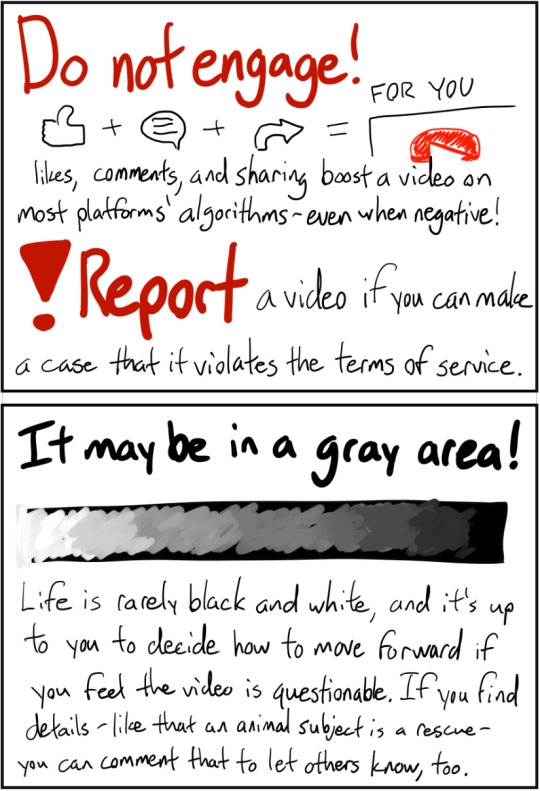

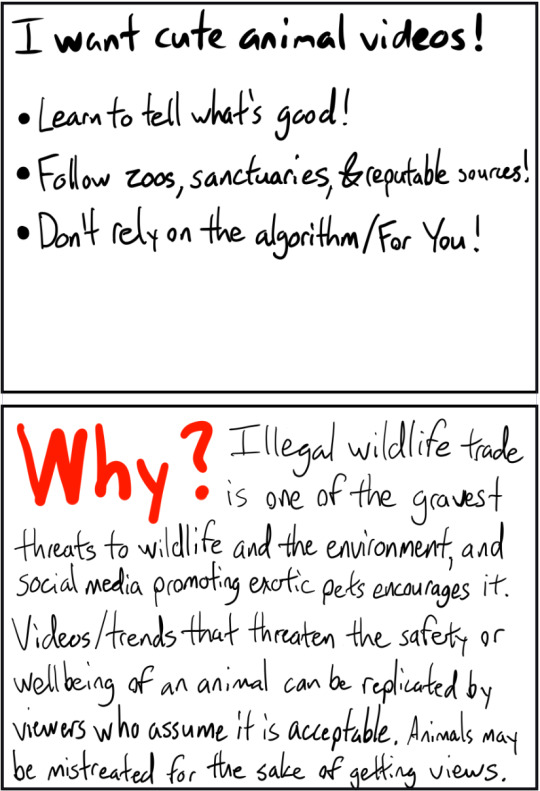

We have lots of wonderful accounts that do a great job of telling if the animal video is cute or not, but it's important for everyone to exercise critical thinking skills and learn how to analyze them too! Here's an infographic with some basics on animal science that can help you decide what to look for.

Key questions for analyzing videos:

Are all of the animals and people in the video (including the filmer) safe?

Is the animal choosing to participate?

What behavior or activity is being shown - is it a natural and positive behavior for the animal, is it enriching? Or may it be a negative behavior? You can search ‘animal’ ‘behavior’ online - like “gorilla picking itself” - for a quick check!

What’s the purpose of the video - is the situation created for the animal, or for viewers?

Is it sensible that the animal is there, doing what it is doing?

Overall - figure out what you can see, and what you need to find out/double check, and then search that! Add it all up and you should be able to draw your own conclusions too.

Please check out some of our other posts for examples on how to think through videos you may see!

Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute. (2022, May 25). Animal Enrichment. Smithsonian's National Zoo. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/animal-enrichment

Bielawski, J. (2017, January 5). Beware what you share! "Cute" videos are often cruel. Animal Help Now. Retrieved March 22, 2023, from https://ahnow.org/blog/2017/01/05/beware-what-you-share-cute-videos-are-often-cruel/

Goldstein, H. (2022, April 13). What to do when you see animal cruelty on Social Media. What to Do When You See Animal Cruelty on Social Media. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://www.worldanimalprotection.us/blogs/what-do-when-you-see-animal-cruelty-social-media

American Veterinary Medical Association. (n.d.). Animal welfare: What is it? Animal Health Welfare. Retrieved March 28, 2023, from https://www.avma.org/resources/animal-health-welfare/animal-welfare-what-it Colchester Zoo. (2022, February 11). Environmental enrichment. Colchester Zoo. Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://www.colchester-zoo.com/about-us/environmental-enrichment/

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adorable but Deadly Fluff Balls, Better Known as Pygmy Slow Lorises, Born at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo

The two babies are part of an endangered species whose unbearable cuteness has made them a target for wildlife traffickers

Small mammal caretakers at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute (NZCBI) were in for a surprise late last month when they arrived at work. Naga, a 3-year-old pygmy slow loris, had two newborn babies holding on to her. They’re the first of their endangered species born at the zoo, according to an announcement. Zookeepers had suspected that Naga was pregnant—she’d started gaining weight after being introduced to a 2-year-old male named Pabu in September—but they didn’t know for sure because her thick fur made it difficult to obtain an ultrasound image. So on March 21, when Kara Ingraham spotted Naga hanging out on a high branch at a time of day when she’s normally sleeping, she knew she needed to take a closer look...

Read more: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/first-endangered-pygmy-slow-lorises-born-at-smithsonians-national-zoo-and-conservation-biology-institute-180984112/

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help Nature

The six ferret kits at the Smithsonian National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute’s breeding facility in Front Royal, Va., just passed their 90-day health check with flying colours.

#ferret #kits

Smithsonian Magazine

5 notes

·

View notes