#shinbutsu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Please join this server dedicated to Japanese Buddhism! ☸️🙇🏻

1 note

·

View note

Text

Imakumano Kannon-ji

The story goes that Kūkai was in the area and a bright light came upon him, and revealed itself to be Kumano Gongen (kami of the Kumano Pilgrimage). He gave Kūkai a statue of the 11 Faced Kannon that had been carved by Amaterasu Ōmikami and instructed him to build a temple, alongside that statue Kūkai carved a second one and enshrined them together.

I love how many of Kūkai's tales really reflect the importance of Shinbutsu Shugo during his time and his respect for and reverence for the kami. It's neat.

There was of course a shrine dedicated to Kumano Gongen on the grounds.

And of course here's the goshuin

#Imakumano Kannon Ji#Imakumano Kannon-ji#buddhism#shinbutsu shugo#kami#photos#goshuin#Temples#Shrines#Shinto

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm considering starting a series on my Wordpress where I give information on kamisama - head shrines, known unique offerings they like, and so on. I am also a minimum wage worker, so I may make this a Patreon thing where people can vote for the next kamisama I write about. IDK. Thoughts? Please feel free to reply or what have you.

(For clarity, the information would be public, but being a Patron would simply give you the ability to request kamisama or vote)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In my studies I've seen many pictures of small shrines like this. Because Buddhist and Shinto so often look very similar it's becomes necessary to look for visual clues to determine if it is a Shinto shrine, a Buddhist shrine, or some curious mix of the two.

A Small Vermilion Shrine for Fudōmyō-Ō, the Immovable Wisdom King ・華寺境内の朱色が美しい不動明王堂

A small vermilion shrine housing a statue of the Buddhist deity Fudōmyō-Ō, or the “Immovable Wisdom King.”

Although located within the grounds of Ryuge-ji, a Buddhist temple, the shrine’s architecture closely resembles that of a traditional Shinto hokora. It’s a quiet example of how Japan’s two spiritual traditions — Buddhism, introduced from China, and indigenous Shinto — once blended naturally in daily life.

This fusion is known as shinbutsu-shūgō (神仏習合), the harmonious coexistence of kami and Buddhas that flourished for centuries. While the Meiji government’s separation order in 1868 sought to divide the two, the effort was not entirely successful. Even today, small moments like this remind us of the enduring ties between them.

Location: Kanazawa Ward, Yokohama, Japan Timestamp: 2025/01/09 17:12 Fujifilm X100V with 5% diffusion filter ISO 320 for 1/480 sec. at ƒ/2.5 Classic Negative film simulation

For a deeper dive, check out sources for further reading and Google Maps links: https://www.pix4japan.com/blog/20250309-fudomyo-o

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sukuna's Backstory Theory (+ mini Uraume Backstory Theory)

While we wait for jjk ch 265 leaks, I hope you enjoy reading this post of mine in the meantime.

Please note that this is just my theory. Also, Sukuna deserves to die.

Now enjoy your reading.

WARNING: MANGA SPOILERS UP TO CH 264; subject covers the following sensitive topics: sacred s*x, cannibalism, homosexual relationships; mentions or implications of abuse

Beginning:

We know from Sukuna himself in chapter 237 that he was an 忌み子 - a taboo child. In ancient and medieval Japan, a taboo child is a child that is ostracized, unwanted, and discarded.

JJK CHAPTER 237

As mentioned by Sukuna, he himself 'consumed' his twin to survive and had presumed that his 'foolish mother' (愚母 - he wasn't looking down on her, calling her stupid, but instead he was humbly referring to her) must have been starving.

JJK CHAPTER 257

Prominent families during that time were the Fujiwara, Sugawara and Abe clans. For sure, he wasn't born a noble, but rather a commoner, or worst, a slave. He must've been born with weak or below average CE, too, aside from his four arms, four eyes, and the second face.

It was probably only him and his mother in the beginning and she was the only one taking care of him. Given their supposed circumstances, Sukuna must've started working by the time he was around 5 or 6. Plus, if I were to guess where they would've lived, it would be in the agricultural lands of a Buddhist-Shinto temple. In Heian era, Buddhism and Shinto co-existed together (shinbutsu-shuugoo) so it's not strange to find Buddhist temples to have at least one small shrine dedicated to a kami (a Shinto god/goddess) [these are calles jisha (寺社)] and Shinto shrines accompanied by Buddhist temples in mixed complexes [these are called jinguuji (神宮寺)].

In addition, these institutions had these manorial estates called, shooen (荘園), which were "any of the private, tax free, often autonomous estates or manors...... developed from land tracts assigned to officially sanctioned Shintō shrines or Buddhist temples or granted by the emperor as gifts to the Imperial family, friends, or officials." In the case of shrines and temples with shrines in them, they are called mikuri (御厨), which means a god's/goddess' kitchen.

The Chinese characters for mikuri are the same as the first two letters of Sukuna's CT (御厨子). In the beginning, mikuri only referred to the place where shrine offerings/sacred food (fish, vegetables, etc.) were cooked, but it eventually also included the land or property where they get the offerings from and prepare them in the meaning. Plus, the citizens of these lands/properties were called "gods' & goddesses' people" (神人, shinjin), and these mostly consisted of the producers (fishermen, farmers, etc.). We can definitely infer that Sukuna has most likely worked in the cooking area of the mikuri, the 御厨子所 (mizushidokoro, a kitchen for the upper classes and the shrines and temples) Think about it, not only does he use words related to consuming, but he also referenced fish-related words.

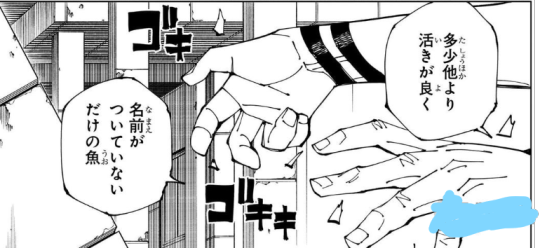

JJK CH 224 - "A fish who merely has no name attached to it."

JJK CH 216 - "卸す" - to grate (e.g. vegetables); to cut up fish "三枚に卸す” - to cut you into three slices (fillet)

JJK CHAPTER 8 - "おろした" - past tense verb of 卸す "三枚におろした” - cut you into three slices (fillet)

(light blue is just to cover watermarks)

In Heian era, meat was forbidden except for some parts in Japan where hunting was really common (except for aristocrats and monks lowkey - they do eat them at times, especially when they fall sick). Fish was temporarily banned but was eventually lifted. So, majority of the Japanese people during this time period didn't eat meat with the exception of fish and other seafood. Moreover, when cooking the shrine offerings, the only meat they cooked was seafood. Plus, if he and his mom was in one of the shrine and temples in Heian-kyoo (present-day Kyoto), then chances are he had to cook for festivities and rituals in the imperial palace.

But then, how did he learn to read and write? The only one who were literate were the imperial family, aristocrats, Shinto priests, Buddhist monks, and anyone else related to religious institutions and higher rank than commoners. So the only available ways for him to have access to learning kanji (漢字 - Sino-Japanese characters) and even kana (hiragana and katakana) was to become an apprentice monk or priest. But I believe he became a Buddhist apprentice monk since it is more open than becoming a Shinto priest.

If he had started as a worker in the mikuri, he would have been secretly listening to the lessons between an apprentice and the older monk. Then, if he managed to prove his talent, he could have become an apprentice. If he were an apprentice monk, he would have to learn directly from an older monk. This would not stop him from working as a kitchen worker since he would have to help with preparing offerings and cooking for important occasions and guests.

As an apprentice, he would have learned everything about Buddhism, including how to preach to people. Unfortunately, there was a cost to this. It was the nanshuudou, the homosexual practice between a prepubescent apprentice monk and an older adult monk, which is heavily documented in Edo period but a practice that has been ongoing in the Shinto priest apprenticeships and eventually in Buddhist monk apprenticeship, as well. Mind you, this is not a practice between male lovers, but of loyalty and the first step to 'reaching enlightenment'. I think of it as a pseudo-sacred s*xual relationship. It is something expected at that time, but it may not have been a great experience for Sukuna. He was a taboo child, meaning even those older monks most likely made this harsher than it already was. Not to mention, he might have been as young as 7 or 8 years old when this all happened.

This was also sort of thought of by a JP theorist, according to this twitter user.

Anyways, let's move on from this sensitive topic.

You might be wondering why do I think he had been an apprentice monk and a cook? Well, mizushi (御厨子) also has these meanings.

Zushi (厨子) originally was a word for storage boxes for utensils and ingredients in the kitchen, then extended into becoming a storage for personal stuff and a decoration as well for aristocrats.

Zushi also extended to becoming a storage for Buddhism relics, scrolls or anything important. This includes the Buddhist altars. Thus becoming Mizushi, sacred storage.

Additionally, as an apprentice monk, he would be able to interact with nobility more. Buddhism was intertwined with the court politics in Heian era. This is more prominent when court officials and even the imperial family members, including the Emperor, would retire as Buddhist nuns or monks. Plus, there would also be visits by the officials and probably he was able to see or receive letters and poems from them. It would be inevitable that he learns them to communicate effectively.

This would also makes sense as he knew Tengen, who was an avid supporter of Buddhism.

Career as a Sorcerer:

In an era where the Fujiwara clan ruled supreme, leaving barely any crumbs for other aristocratic clans to take spots in the political arena. So, in order to consolidate their own power, many other clans (including the minor/weak branch families of the Fujiwaras) and Imperial princes went to obtain their own land outside of Heian-kyoo (present-day Kyoto) and even their own army. That's why these clans have armies of their own, especially those full of sorcerers. I won't be surprised if they took in anyone who has curse energy and trained them, just like what the Fujiwaras did with Uro.

So, I believe that someone noticed his cursed energy and his potential, then took him for training. Then obviously he would have met other Heian-era sorcerers. Here are my two cents on this:

I would like to believe that Tengen trained him as she was also an avid supporter of the religion, and he eventually met Kenjaku as they're 'friends' with her. Being a jujutsu sorcerer apprentice meant quitting or being part-time in his apprenticeship from the Buddhist Temple. (But I wonder if this would have stopped the pseudo-sacred s*x stuff.......) However, I'm open to the fact that it might have been another sorcerer who trained him (or there has been another one besides Tengen and Kenjaku who did so or influenced him) due to the name of his extension technique 'Divine Flames, Open'

One of the opposing factions (either the Sugawara, Tachibana or Abe clan) to the Fujiwara hired him in their order to put them in check. I'm leaning more towards the Sugawara clan.

This was probably the time when he probably met Angel from Abe clan, Uro from the Fujiwara, and especially Uraume. I'll explain how Uraume is related to the Sugawaras in a bit.

Sukuna served as part of Sugawara's troops or something like that. This can also be the point where he learned more about Japanese art and culture at the time.

One of the curses he must've fought was Yamata no Orochi.

Sukuna betrayed the Sugawaras and destroyed its army of sorcerers, with a few survivors left. Uraume decided to dedicate their whole life to him and followed him from then on.

He officially became a curse user and wrecked havoc in Japan, especially Heian-kyoo

Angel got enraged from his acts and with the permission of the Abe clan and the remnants of Sugawara clan, they jumped on Sukuna but lost.

Later on, he defeated the Fujiwara army led by Uro.

How is Uraume related to the Sugawaras?

There's this video from JP channel that was theorizing about Uraume when they first appeared in Shibuya arc a couple years ago that they used to be trapped in the prison realm before being freed so that Kenjaku can use it for Gojo Satoru and it was time for Sukuna's resurrection but this was obviously debunked, but there was something interesting that the creator brought up - the Tobiume.

Have you heard about The Legend of the Flying Plum (飛梅伝説)? So basically, when Sugawara no Michizane was demoted in ranking because of the Fujiwaras and was exiled, he wrote a poem expressing his sorrow of not seeing his precious plum tree in his residence in Heian-kyo (present-day Kyoto) ever again. Then from this, a romantic legend came about, where the plum tree was so fond of its master and cannot bear to be apart from him that it finally flew to Dazaifu, where he was exiled to, and that tree became known as tobi-ume (飛梅, 'the flying plum').

Michizane loves plum trees and plum blossoms, so it won't be strange if there were people in the clan named after plum blossoms or plum. In my case, I believe that Uraume is related to the Sugawara clan, but their status in the clan itself wasn't great. We can assume from their name in kanji, 裏梅.

裏 means the following:

opposite side; bottom; other side; side hidden from view; undersurface; reverse side

rear; back; behind

in the shadows; behind the scenes; offstage; behind (someone's) back

梅 means plum

Though they may have been born from a noble, prestigious clan, they remained in the shadows. My theory is that, for whatever reason it may be, Uraume's life wasn't as good as before Sukuna allowed them to serve him. They might have been an illegitimate child or they might have some deformity we don't know of, or whatever. Then they met Sukuna and the rest was history.

Do you not believe that Uraume is not related to the Sugawaras?

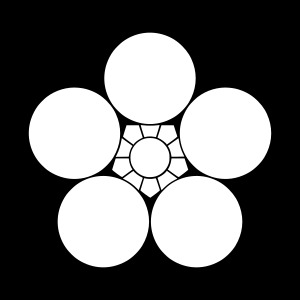

Let me show you a picture of the Sugawara clan crest.

They call this umebachi. A plum blossom crest.

And what's in Uraume's name? Ume (梅) - plum.

Another thing here that fulfill its name is the fact that Uraume is Sukuna's servant. Just like the tobiume, they follow their master from behind and cannot bear to be apart from him.

'Divine Flames, Open':

Here's something that caught my attention.

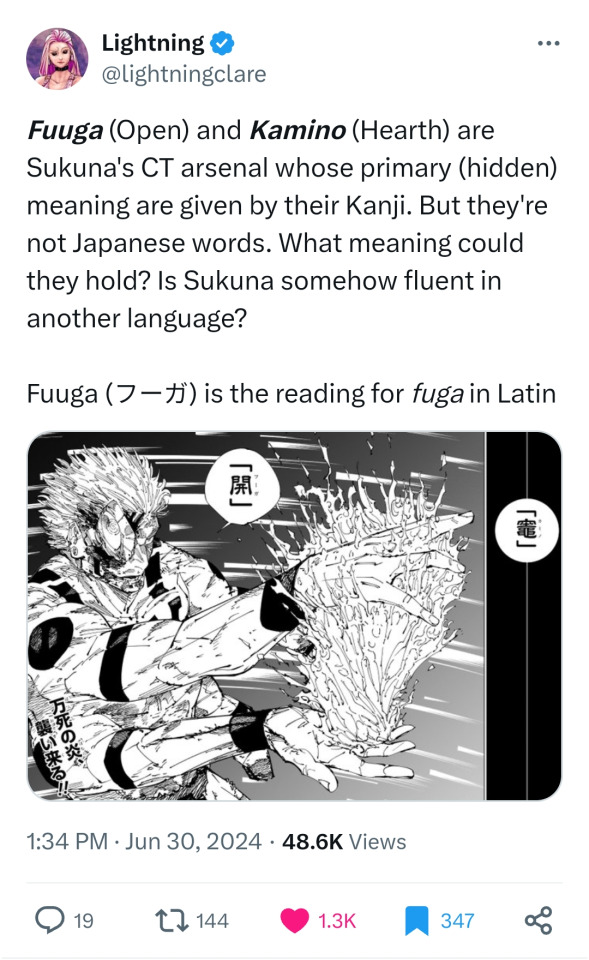

Kamino (カミノ) has the kanji 竈, that is originally pronounced as kamado. It means traditional Japanese wood or charcoal-fueled cook stove. Fuuga (フーガ) has the kanji 開, originally pronounced as kai, meaning open. Now everything else is purely Japanese except these two.

Kamino and fuuga originated from Latin and Ancient Greek, and both exist in the Romance languages. How tf is he using these words? Around Heian era, only the Eastern Roman Empire is standing and the main language there was Greek....... but that's around present-day Turkey and its surroundings. The furthest they reached in trade was China...... oh wait, Heian era Japan still traded with China........

Seems like that theory of Chinese sorcerer isn't far-fetched, eh?

(But fr tho, do you think he met someone from Byzantine? There's no confirmation time travel is a thing so that's the only possible explanation)

Cannibalism:

Cannibalism, believe it or not, was practiced in China from Tang Dynasty and onwards. Remarkably, Heian era's last major Chinese contact was with Tang Dynasty. Records of cannibalism must have been brought from Tang Dynasty China along with Buddhism and other things by monks who were sent to China by the government.

It was said that human flesh of a young person was a great medical treatment for illnesses. So there would be young people, especially females, sacrificing some of their flesh for the sake of their parents or parent-in-laws recovery. Furthermore, Emperors, e.g. Wuzong of Tang, supposedly ordered provincial officials to send them "the hearts and livers of fifteen-year-old boys and girls" when they had become seriously ill, hoping in vain this medicine would cure him. Later on, private individuals sometimes followed their example, paying soldiers who kidnapped preteen children for their kitchen.

There was also something called war cannibalism, in which victors in a battle, war, or conflict would eat the dead enemy's flesh as "official punishments and private vengeance", as well as "celebrating victory over them."

Therefore, I propose that Sukuna started cannibalism as a way to treat an illness or disease - in private obviously since in Heian era, meat other than seafood was banned and meat that becomes available for special occassions or circumstances like falling sick are reserved for the upper class, plus if he ever was an apprentice monk, he would not have been allowed to consume meat. Since Heian era had outbreaks, such as smallpox, and also common diseases, anyone can get it, including him. So, not wanting to die, he resorted to this. But then it eventually became a habit that also extended to eating people he defeated in battles and young people and women for medicinal and nutritional purposes later on. This is the most likely the reason why in the first chapter, he was looking for children and women.

But if he had contracted some sort of illness or disease at some point in his youth and cannibalism (obviously) wasn't a cure for it, how would he have survived it and lived longer? Perhaps it might have to do with Tengen - who knows if she could have an extension technique of her Immortality CE, where she could have extended his lifespan. It could have had to do with Kenjaku; with their vast knowledge, it's possible he offered a solution to him. However, I'm leaning more towards Tengen helping him in this regard. It was also probably the reason why she ended up having four eyes and all because of this. But, of course, he couldn't escape death, so he agreed to Kenjaku's terms and became cursed objects to reincarnate later on.

My second proposition is that Sukuna was maltreated and the people didn't bother sharing meager amount of food available to him. We know that because of the Fujiwara family's political monopoly in the capital as well as the distribution of the land to nobility made it possible for them to abuse their power. For instance, these lords imposed taxes in an unreasonable amount to fund their lavish lifestyle, which obviously made life hard for the peasants and slaves since goods such as silk, grains and food became a common medium of exchange when the currency fell. So you can imagine how much they had to give up just to pay their taxes. This definitely made their food supply low. I can also imagine Sukuna was blamed for misfortunes and misery they have experienced because of his status as a taboo child. I don't think they would provide him food and so he would have to rely on dead people to survive.

And assuming that we're going off with this proposition instead of the other one, I think the reason why Sukuna was seeking women and children because in the past, it was more common for children and women to die. Children are naturally more vulnerable and women die easily, especially during childbirth. I'm certain that the most common corpses or bodies he must've found were those of children and women. But, of course, eventually he began to crave humans because he got so used to it that normal food didn't satisfy his hunger any longer - not that cannibalism fully resolved it, though.

The Fallen:

(I'm not gonna lie, majority of what I would say here are more assumptions based on Geto's and a bit of Yuji's acts)

Everyone has been comparing Sukuna and Gojo, seeing them as foils and parallels. I acknowledge that they are similar to each other and whatnot. But what if I tell you that he could've gone through an experience or two similar to Geto?

Think about it. Wouldn't you consider Geto as a 'Fallen One'? He was a righteous man, whose goal is to protect the weak as a strong person. But after the Toji incident, his moral convictions and purpose has been questioned by himself, and eventually, he fell from grace - being stripped of his status as a jujutsu sorcerer and thus becoming a curse user. He had the same values but they were reinterpreted and twisted.

If my theory on Sukuna being educated at a Buddhist Temple is true, then he must have believed in the salvation of those who are suffering (like Yuji to some extent), but was corrupted along the way. He had the same ideals, but it became reinterpreted and twisted. I think the reason why he hates Yuji because he is seeing all those he threw away to gain freedom and absolute strength in jujutsu in him. Both of them are inverses of each other, and it's not a surprise if Yuji is the representation of the old Sukuna.

I mean if you look at nobility back in Heian era, they kept indulging themselves in leisure and pleasure to the point that they neglected the economy. Literally the currency fell and all those bureaucratic and admin work fell mostly to lower classes working in each ministry. Basically back then, the higher you were in the hierarchy, the more pleasure you could attain and keep chasing for. How else did you think Japanese art, literature and culture came to be during this era? This was where he probably learned about hedonism or what influenced him to be one.

Not to mention, people who would've taken advantage of him for their pleasure, curiosity, greed and personal gains, power and control, and many more reasons. He could have been like Geto and Yuji, who exorcise curses and help the weak. There was a turning point where he decided to let go of everything and walk the path that he has been in for the last 1000 years.

I am not surprised if he decided to be who he is today as a revenge to the world, a response to the trauma and suffering he went through just like Geto.

If I am right about Sukuna going through a similar experience as Geto did, then this page below brings a whole new meaning to the Gojo vs Sukuna fight on December 24, 2018 - the death anniversary of Geto:

JJK CH 223

But despite all of these, there's one thing we can agree on - that is, he became the monster the world sees him as in the end.

That will be it. I hope y'all like it to some extent. Until then.

References:

Heian Era, Buddhism, 御厨子 -related Topics:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sh%C5%8Den/

https://ja.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%BE%A1%E5%8E%A8

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhist_temples_in_Japan

https://www.britannica.com/place/Japan/The-Heian-period-794-1185

https://www.colorado.edu/ptea-curriculum/imaging-japanese-history-1

https://ja.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8E%A8%E5%AD%90

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sugawara_no_Michizane

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heian_period

https://www.colorado.edu/ptea-curriculum/imaging-japanese-history-1

Homosexuality in Medieval Japan:

https://www.tofugu.com/japan/gay-samurai/

https://ida.mtholyoke.edu/items/19c86409-c129-46a1-927b-11cfe0ffb1c3

Cannibalism & Sacred S*x-related Topics:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_cannibalism

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Medical_cannibalism&diffonly=true

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cannibalism_in_Asia

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sexual_ritual

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_prostitution

Ancient Greek, Latin, & Roman Empire Topics:

https://en.m.wiktionary.org/wiki/fuga

https://en.m.wiktionary.org/wiki/caminus

https://en.m.wiktionary.org/wiki/camino

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Roman_relations

YouTube Videos I Referenced:

https://youtu.be/5n24Ulc8u84?si=Nngbg4xEqyNu82x8

https://youtu.be/WhBN29CIuAQ?si=5bNryoT-GzleIGq9

Reddit Posts I Referenced:

https://www.reddit.com/r/Jujutsushi/comments/1bngk9x/i_solved_one_of_the_great_mysteries_of_the_heian/

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/ztay5e/what_foreign_countries_did_japan_have_trade/

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/zs4k9p/what_was_life_like_for_the_average_people_heian/

Twitter Posts I Referenced:

https://x.com/eldammonite/status/1571157320570380295

https://x.com/lightningclare/status/1807467771913269374

#jjk#jjk manga#jjk meta#jjk sukuna#sukuna#ryomen sukuna#sukuna ryomen#uraume#jjk uraume#jujutsu kaisen manga#jujutsu kaisen#jujutsu geto#jjk geto#gojo satoru#geto suguru#jjk spoilers#jujutsu sukuna#jjk 265

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sean bienvenidos, japonistasarqueológicos, a una nueva entrega de religión nipona, una vez dicho esto pónganse cómodos qué empezamos. - Seguramente, todos hemos escuchado hablar del Budismo y Sintoísmo, dos religiones muy diferentes entre sí, ya que sus pilares religiosos no están hechos de la misma materia, voy a intentar resumir este tema para que todos podamos entenderlo mejor. ¿Cuándo llego el budismo a Japón? Llego en el siglo VI d.c en el período kofun también denominado protohistoria, lo que no voy a negar y lo que todos sabemos es que china, India y otros países influenciaron a Japón y eso lo podemos ver todavía a día de hoy. - Pero hace poco vi el uso de la palabra Sincretismo religioso, lo cual, me parece el término de lo menos apropiado, ¿Qué significa sincretismo? Unión, fusión e hibridación, casos más claros, lo podemos ver en Latinoamérica y con Grecia y Roma. Por lo cual el término más apropiado para este caso sería coexistencia o convivencia, además en el periodo meiji hubo una reforma religiosa para separar ambas religiones y convivencia al sintoísmo, religión del estado, a esto se le llama Shinbutsu bunri en hiragana sería:(しんぶつぶんり) ¿Qué opinan ustedes? - Espero que os haya gustado y nos veamos en próximas publicaciones que pasen una buena semana. - ようこそ、考古学的日本びいきの皆さん、日本の宗教の新連載へ。 - 仏教と神道、この二つの宗教の柱は同じ材料でできているわけではないので、私たちは皆、この二つの宗教について聞いたことがあるだろう。 仏教はいつ日本に伝来したのだろうか?仏教が日本に伝来したのは紀元6世紀の古墳時代で、原始時代とも呼ばれている。しかし、中国やインド、その他の国々が日本に影響を与えたことは否定しないし、誰もが知っていることである。 - しかし最近、宗教的シンクレティズムという言葉が使われているのを目にした。シンクレティズムとは何を意味するのだろうか?統合、融合、ハイブリッド化、その最も明確な例はラテンアメリカやギリシャ、ローマに見られる。また、明治時代には宗教改革が行われ、両宗教を分離し、国教である神道と共存させた。 - 今後の記事もお楽しみに。

-

Welcome, archaeological Japanophiles, to a new instalment of Japanese religion, so make yourselves comfortable and let's get started.

Surely, we have all heard about Buddhism and Shintoism, two very different religions from each other, as their religious pillars are not made of the same material, I will try to summarize this topic so we can all understand it better. When did Buddhism arrive in Japan? It arrived in the 6th century A.D. in the Kofun period also called protohistory, what I will not deny and what we all know is that China, India and other countries influenced Japan and we can still see that today.

But recently I saw the use of the word religious syncretism, which seems to me the least appropriate term, what does syncretism mean? Union, fusion and hybridisation, the clearest cases of which can be seen in Latin America and with Greece and Rome. So the most appropriate term for this case would be coexistence or coexistence, also in the meiji period there was a religious reform to separate both religions and coexistence to Shinto, state religion, this is called Shinbutsu bunri in hiragana would be:(しんぶつぶんり) What do you think?

Hope you liked it and see you in future posts have a good week.

#history#japan#culture#kyoto#geography#photos#education#japan photos#photography#photo#artists on tumblr#original artists on tumblr#archeology#日本#歴史#ユネスコ#unesco#考古学#art

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

tengen is sukuna's mother

It's time for me to do something. Let's start with this page, aka one of the only times we see Sukuna mention Tengen directly in the manga. We see him eating his old body, which is now a shinbutsu mummy. This state is achieved only via *extreme* fasting which will keep the body-

what's the takeaway here

We know that Sukuna should have been a twin, but was forced to eat him to survive due to starvation from his mother's womb. My theory is that Tengen is Sukuna's mother, which is exactly why he called the act of eating his old body that Tengen had conserved with her ironic

He was eating "Himself" because of her again, and not only that the "himself" in question was left in a state of extreme starvation, tying in to the first time again. Imo, this scene, is Tengen expressing desire to feel close to her son, even just by looking like him, because

-she couldn't give him even a smidge of the motherly love he should've had due to her being deeply plunged in her isolation and buddhist practices, only idly watching the world unfold, which deeply infuriates activists like Kenjaku and Tsukumo Yuki

And what Sukuna undergone before being born was akin a gu ritual, and the Culling Game is like a gu ritual too, where the strongest survives

"With this theory in mind it gives another layer of poetry to Yuji and Sukuna. Both were abnormal due to their mothers, both were too strong to relate to others, both bear the spiral of curses in their eyes yet the path they chose were fundamentally different"

#jjk theory#ryomen sukuna#jjk tengen#jujutsu kaisen#jujutsu kaisen theory#jujutsu kaisen meta#jjk spoilers#yuji itadori#jjk

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

if you are struggling with writing a character and that character is uchiha madara, the solution to your problem is to cut out his pov altogether and not elaborate on anything. if he's not forcing the audience to draw their own conclusions based on speculation from other characters' thoughts on him and from violence-oriented shinbutsu symbolism, you're doing something wrong

#naruto#naruto shippuden#uchiha madara#writing advice#honestly this is mostly for me i've been having Thoughts again

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mai, Satono and their peers: a look into the world of dōji

Okay, look, I get it, Mai and Satono are not the most thrilling characters. I suspect they would be at the very bottom of the list of stage 5 bosses people would like to see expanded upon. Perhaps they are not the optimal pick for another research deep dive. However, I would nonetheless like to try to convince you they should not be ignored altogether. If you are not convinced, this article has it all: esoteric Buddhism, accusations of heresy, liver eating, and even alleged innuendos. As a bonus, I will also discuss a few other famous Buddhist attendant deities more or less directly tied to Touhou. Among other things, you will learn which figure technically tied to the plot of UFO is missing from its cast and what a controversial claim about a certain deity being a teenage form of Amaterasu has to do with Akyuu.

Mai, Satono and the grand Matarajin callout of 1698

An Edo period depiction of Matarajin and his attendants (via Bernard Faure's Protectors and Predators; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

As indicated both by their family names and their designs, Mai and Satono are based on Nishita Dōji (爾子多童子) and Chōreita Dōji (丁令多童子), respectively. These two deities are commonly depicted alongside Matarajin, acting as his attendants, or dōji. Nishita is depicted holding bamboo leaves and dancing, while Chōreita - playing a drum and holding ginger leaves. ZUN kept the plant attributes, though he clearly passed on the drum. In the HSiFS interview in SCoOW he said he initially wanted both of them to hold both types of leaves at once, so I presume that’s when the decision to skip the instrument has originally been made. We do not actually fully know how Nishita and Chōreita initially developed. It is possible that their emergence was a part of a broader process of overhauling Matarajin’s iconography. While initially imagined as a fearsome multi-armed and multi-headed wrathful deity, with time he took the form of an old man dressed like a noble and came to be associated with fate and performing arts. The conventional depictions, with the attendants dancing while Matarajin plays a drum under the Big Dipper, neatly convey both of these roles. The group was additionally responsible for revealing the three paths (defilements, karma, and suffering) and three poisons (greed, hatred, and desire) to devotees.

In addition to being a mainstay of Matarajin’s iconography, Ninshita and Chōreita also had a role to play in a special ceremony focused on their master, genshi kimyōdan (玄旨帰命壇). This term is derived from the names of two separate Tendai initiation rituals, genshidan (玄旨壇) and kimyōdan (帰命壇).

Genshi kimyōdan can actually be considered the reason why Matarajin is relatively obscure today. In 1698, the rites were outlawed during a campaign meant to reform the Tendai school. It was lead by the monk Reiku (霊空), who compiled his opinions about various rituals in Hekijahen (闢邪篇, loosely “Repudiation of Heresies”). Matarajin is not directly mentioned there, and the polemic with genshi kimyōdan is instead focused on a set of thirteen kōan pertaining to it, with mistakes pointed out for each of them. Evidently this was pretty successful at curbing his prominence anyway, though.

By the 1720s, even members of Tendai clergy could be somewhat puzzled after stumbling upon references to Matarajin, and in a text from 1782 we can read that he was a “false icon created by the stupidest of stupid folks“. He ceased to be venerated on Mount Hiei, the center of the Tendai tradition, though he did not fade away entirely thanks to various more peripheral temples, for example in Hiraizumi in the north. Ironically, this decline is very likely why Matarajin survived the period of shinbutsu bunri policies largely unscathed when compared to some of his peers like Gozu Tennō.

“Nine out of ten Shingon masters believe this”, or the background of the Matarajin callout

Dakiniten (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Tendai reformers and critics associated genshi kimyōdan with an (in)famous Shingon current supposedly linked with Dakiniten, Tachikawa-ryū. This is a complex issue in itself, and would frankly warrant a lengthy essay itself if I wanted to do it justice; the most prominent researcher focused on it, Nobumi Iyanaga, said himself that “it is challenging to write about the Tachikawa-ryū in brief, because almost all of what has ever been written on this topic is based on a preconceived image and is in need of profound revision”. I will nonetheless try to give you a crash course. Recent reexaminations indicate that originally Tachikawa-ryū might have been simply a combination of Shingon with Onmyōdō and local practices typical for - at the time deeply peripheral - Musashi Province. Essentially, it was an ultimately unremarkable minor lineage extant in the 12th and 13th centuries. A likely contemporary treatise, Haja Kenshō Shū (破邪顕正集; “Collection for Refuting the Perverse and Manifesting the Correct”) indicates it was met with at best mixed reception among religious elites elsewhere, but that probably boils down to its peripheral character. Starting with Yūkai (宥快; 1345–1416) Shingon authors, and later others as well, came to employ Tachikawa-ryū as a boogeyman in doctrinal arguments, though. Anything “heretical” (or anything a given author had a personal beef with) could be Tachikawa-ryū, essentially. It was particularly often treated as interchangeable with a set of deeply enigmatic scrolls, referred to simply as “this teaching, that teaching” (kono hō, kano hō, 此の法, 彼の法; I am not making this up, I am quoting Iyanaga); I will refer to it as TTTT through the rest of the article. These two were mixed up because of the monk Shinjō (心定; 1215-1272) who expressed suspicion about TTTT because of its alleged popularity in the countryside, where “nine out of ten Shingon masters” believe it to be the most genuine form of esoteric Buddhism. However, he stresses TTTT was not only non-Buddhist, but in fact demonic. The description of this so-called “abominable skull honzon”, “skull ritual” or, to stick to the original wording, “a certain ritual” (彼ノ法, ka no hō) meant to prove the accusations is, to put it lightly, quite something.

Essentially, the male practitioner of TTTT has to have sex with a woman, then smear a skull with bodily fluids generated this way over and over again, and finally keep it in warmth for seven years so that it can acquire prophetic powers. This works because dakinis (a class of demons) live inside the skull. The entire process takes eight years because Dakiniten, the #1 dakini, attained enlightenment at the age of 8. Shinjō himself did not assert TTTT was identical with Tachikawa-ryū, though - he merely claimed that at one point he found a bag of texts which contained sources pertaining to both of them. Ultimately it’s not even certain if TTTT is real. It might be an entirely literary creation, or an embellishment of some genuine tradition circulating around some marginal group like traveling ascetics. We will likely never know for sure.

Regardless of that, Tachikawa-ryū became synonymous not just with incorrect teachings, but specifically with teachings with inappropriate sexual elements. By extension, it was alleged that the songs and dances associated with Matarajin and his two servants performed during genshi kimyōdan similarly had inappropriate sexual undertones.

ZUN seems to be aware of these implications, since the topic came up in the aforementioned interview. The interviewer states they read that “during the middle ages a lot of Tendai and Shingon sects end up becoming obsessed with sexual rituals and wicked teachings, leading to their downfall” (bit of an overstatement). In response, ZUN explains that these matters are “interesting” and adds that he “did prepare some materials with that, but that would make [the game] too vulgar.” No dialogue or spell card in the game actually references genshi kimyōdan, for what it’s worth, but seeing as this is the only real point of connection between Matarajin and such accusations it’s safe to say ZUN is to some degree familiar with the discussed matter.

As in the case of the Tachikawa-ryū, modern researchers are often skeptical if there really was a sexual, orgiastic component to the rituals, though. A major problem with proper evaluation is that very few actual primary sources survive. We know the words of the songs associated with Matarajin’s dōji, but they are not very helpful. They’re borderline gibberish, “shishirishi ni shishiri” alternating with “sosoroso ni sosoro”. Polemics present them either as an allusion to sex or as an invitation to it; as cryptic references to genitals; or as sounds of pleasure.

None of these claims find any support in the few surviving primary sources, though. Earlier texts indicate that the dance and song of the dōji was understood as a representation of endless transmigration during the cycle of samsara. When sex does come up in related sources, it is presented negatively, in association with ignorance. Bernard Faure argues that the rituals were initially apotropaic, much like the tengu odoshi (天狗怖し), which I plan to cover next month since it helps a lot with understanding what’s going on in HSiFS. The goal was seemingly to guarantee Matarajin will help the faithful be reborn in the pure land of Amida. However, the method he was believed to utilize to that end can be at best described as unconventional.

To unburden the soul from bad karma, Matarajin had to devour the liver of a dying person. This is essentially a positive twist on a habit attributed in Buddhism to certain classes of demons, especially dakinis, said to hunger for so-called “human yellow” (人黄, ninnō), to be understood as something like vital essence, or for specific body parts. In this highly esoteric context, Matarajin was at once himself a sort of dakini, and a tamer of them (usually the role of Mahakala), and thus capable of utilizing their normally dreadful behavior to positive ends.

The true understanding of these actions was knowledge apparently reserved for a small audience, though. Keiran shūyōshū (溪嵐拾葉集), a medieval compendium of orally transmitted Tendai knowledge, asserts that even monks actively involved in the worship of Matarajin were unfamiliar with it.

Beyond Mai and Satono: dōji as a class of deities

You might be wondering why an article which was supposed to be an explanation of Mai and Satono ended up spending so much time on ambivalent aspects of Matarajin’s character instead. The ambivalence present in the aforementioned liver-related belief was a fundamental component of the character of many deities once popular in esoteric Buddhism, and by extension of their attendants too. Therefore, it is actually key to understanding dōji. As I already mentioned in my Shuten Dōji article a few weeks ago, when treated as a type of supernatural beings, the term dōji implies a degree of ambiguity. The youthfulness of these “lads” means that in most cases they were portrayed as unpredictable, impulsive, eager to subvert social order and hierarchies of power, and prone to hubris. Some of them are outright demonic figures, as already discussed last month. Simply put, they possess the stereotypical traits of a young person from the perspective of someone old. They initially seemingly developed as a Buddhist reflection of Taoist tongzi, in this context a symbol of immortality and youthfulness, though a case can be made that youthful Hindu deities like Skanda (Idaten) also had an influence on this process. Many Buddhist deities can be accompanied by pairs or groups of dōji, for example Jizō, Kannon, Fudō, Dakiniten or Sendan Kendatsuba-ō. In some cases, other deities could manifest in the form of dōji. In Chiba there is a statue of Myōken reflecting such a tradition, for example. There are also “independent” dōji. Closely related terms include ōji (王子), “prince”, used to refer for example to the sons of Gozu Tennō and the attendants of Iizuna Gongen, and wakamiya (若宮), “young prince”, which typially designates the youthful manifestation of a local deity.In the second half of the article, I’ll describe some notable dōji who can be considered relevant to Touhou in some capacity.

Gohō dōji: the generic dōji and the legend of Myōren

A gohō dōji in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The term gohō dōji (護法童子) can be translated as something like “dharma-protecting lad”. It’s not the name of a specific dōji, but rather a subcategory of them. Historically they were understood as something like the Buddhist analog of shikigami. The term gohō itself has a broader meaning, and can refer to virtually any protective Buddhist deity, even wisdom kings or the four heavenly kings. The archetypal example of such a figure is Kongōshu (Vajrapāṇi), who according to Buddhist tradition acts as a protector of the historical Buddha. A good example of a Gohō Dōji is Oto Gohō (乙護法) from Mount Sefuri. He reportedly appeared before the priest Shōkū (性空; 910–1007) before his journey to China, and protected him through its entire duration. Afterwards a temple was built for him. Curiously, this legend actually finds a close parallel in these pertaining to Matarajin, Sekizan Myōjin or Shinra Myōjin protecting monks traveling to China - except the deity involved is a youth rather than an old man. From a Touhou point of view, the most important example of a gohō dōji is arguably this nameless one, though. He appears in the Shigisan Engi Emaki, an account of the miraculous deeds of the monk Myōren, who you doubtlessly know from UFO. The section focused on him is fairly straightforward: a messenger from the imperial court approaches Myōren because the emperor is sick. Using his supernatural powers, he summons a deity clad in a cape made out of swords to heal him without having to leave his dwelling on Mount Shigi himself. He obviously succeeds. Afterwards the court sends a messenger to offer Myōren various rewards, but he rejects them. While the emperor is not directly shown or named, he is presumably to be identified as Daigo. While the supernatural helper is left unnamed and is often simply described as a gohō dōji in scholarship, it has been pointed out that his unusual iconography seems to be a variant of that associated with the fifth of the twenty eight messengers of Bishamonten. A depiction of a similar figure is known for example from the Ninna-ji temple in Kyoto. This makes perfect sense, seeing as the connection between Myōren and this deity is well documented, and recurs through the legends presented in the Shigisan Engi Emaki. Needless to say, it is also the reason why Bishamonten by proxy plays a role in the plot of UFO. Given these fairly direct references, I am actually surprised no UFO character borrows any visual cues from the gohō dōji, seeing as the illustration is quite famous. It was even featured on a stamp at one point.

Zennishi Dōji (Princeton University Art Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Yoshiaki Shimizu has suggested that the connection between Myōren and his Gohō Dōji is meant to mirror that between Bishamonten and his son and primary attendant, Zennishi Dōji (善膩師童子), and highlight that the monk was an incarnation of the deity he worshiped. He also argued that Myōren’s nameless sister (not attested outside Shigisan Engi Emaki) - the character ZUN based Byakuren on - is meant to correspond to Bishamonten’s wife, Kisshōten/Kichijōten (presumably with spousal bond turned into a sibling one). I am not sure if this proposal found broader support, though - I’m personally skeptical.

Kongara Dōji (and Seitaka Dōji): almost Touhou

Fudō Myōō, as depicted by Kyōsai (via ukiyo-e.org; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Kongara Dōji (衿羯羅童子, from Sanskrit Kiṃkara) and Seitaka Dōji (制多迦童子, from Sanskrit Ceṭaka) are arguably uniquely important as far as the divine dōji go - a case can be made that they were the model for the other similar pairs. They are regarded as attendants of Fudō Myōō (Acala), one of the “wisdom kings”, a class of wrathful deities originally regarded as personifications and protectors of a specific mantra or dhāraṇī. In Japanese esoteric Buddhism, they are understood as manifestations of Buddhas responsible for subjugating beings who do not embrace Buddhist teachings. Acting as Fudō‘s servants is the primary role of Kongara and Seitaka. As a matter of fact, both of their names are derived from Sanskrit terms referring to servitude. This is not reflected in their behavior fully: esoteric Buddhist sources indicate that Kongara is guaranteed to help a devotee who would implore him for help, but Seitaka is likely to disobey such a person. Interestingly, both can be recognized as manifestations of Fudō. This seems to reflect a broader pattern: once a deity ascended to a prominent position in esoteric Buddhism, some of their functions could be reassigned to members of their entourage. ZUN arguably references this in Mai and Satono’s bio, according to which “their abilities (...) are nothing more than an extension of Okina's.” Despite the aforementioned shared aspect of their nature, Kongara and Seitaka actually have completely different iconographies. Kongara is portrayed with pale skin, wearing a monastic robe (kesa) and with his hands typically joined in a gesture of respect. Seitaka, meanwhile, has red skin, and holds a vajra in his left hand and a staff in the right. His characteristic five tufts of hair are a hairdo historically associated with people who were sentenced to banishment or enslavement. He’s never portrayed wearing a kesa in order to stress that in contrast with his “coworker” he possesses an evil nature. It has been argued the fundamental ambivalence of dōji is behind this difference in temperaments.

While the pair consisting of Kongara and Seitaka represents the most common version of Fudō’s entourage, he could also be portrayed alongside eight (a Chinese tradition) or uncommonly thirty six attendants. The core two are always present no matter how many extra dōji are present, though. Appearing together is essentially their core trait, and probably is part of the reason why they could be identified with other duos of supernatural servants, like En no Gyōja’s attendants Zenki and Gōki (who as you may know are referenced in Touhou in one of Ran’s PCB spell cards, and in a variety of print works).

As for the Touhou relevance of Kongara and Seitaka, a character very obviously named after the former appeared all the way back in Highly Responsive to Prayers, but I will admit I am personally skeptical if this can be considered an actual case of adaptation of a religious figure. There are no iconographic similarities between them, and their roles to put it lightly also don't seem particularly similar. Much like the PC-98 use of the term makai (which I will cover next month), it just seems like a random choice. At least back in the day there was a fanon trend of treating the HRtP Konngara as an oni and a fourth deva of the mountain, but I will admit I never quite got that one. In contrast with Yuugi and Kasen’s counterparts, Kongara's namesake actually doesn’t have anything to do with Shuten Dōji. The less said about a nonsensical comment on the wiki asserting Kongara’s status as a yaksha (something I have not seen referenced outside of Touhou headcanons, mostly from the reddit/tvtropes side of the fandom) explains why his supposed Touhou counterpart is present in hell, the better.

Uhō Dōji: my life as a teenage Amaterasu protector of gumonji practitioners

Uhō Dōji (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Uhō Dōji (雨宝童子), “rain treasure child”, will be the last dōji to be discussed here due to being by far the single most unusual member of this category. Following most authors, I described Uhō Dōji as a male figure through the article, but as noted by Anna Andreeva, most depictions are fairly androgynous. Bernard Faure points out sources which seem to refer to Uhō Dōji as female exist too; this is why I went with a gender neutral translation of dōji. In any case, the iconography is fairly consistent, as documented already in the Heian period: youthful face, long hair, wish-fulfilling jewel in one hand, decorated staff in the other, plus somewhat unconventional headwear, namely a five-wheeled stupa (gorintō). Originally Uhō Dōji was simply a guardian deity of Mount Asama. He is closely associated with Kongōshō-ji, dedicated to the bodhisattva Kokūzō. The latter is locally depicted with Uhō Dōji and Myōjō Tenshi (明星天子), a personification of Venus, as his attendants.Originally the temple was associated with the Shingon school of Buddhism, though today it instead belongs to the Rinzai lineage of Zen. A legend from the Muromachi period states that Kongōshō-ji was originally established in the sixth century, during the reign of emperor Kinmei by a monk named Kyōtai Shōnin (暁台上人).The latter initially created a place for himself to perform a ritual popularly known as gumonji (properly Gumonji-hō, 求聞持法, “inquiring and retaining [in one’s mind]”).The name Kongōshōji was only given to it later when Kūkai, the founder of the Shingon school of Buddhism (from whose traditions gumonji originates), received two visions - one from a dōji and then another from Amaterasu - that a place suitable to perform gumonji exists on Mount Asama. After arriving there, he stumbled upon the ruins of Kyōtai Shōnin’s temple, so he had it rebuilt and renamed it. Subsequently, Amaterasu appointed Uhō Dōji to the position of the protector of both this location and Buddhist devotees partaking in gumonji in general. Most of you probably know that gumonji pops up in Touhou as the name of Akyuu’s ability in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense. ZUN describes it simply as perfect memory, but in reality it’s an esoteric religious practice focused on chanting the mantra of Kokūzō 1000000 times over the course of a set period of time (either 100 or 50 days). The goal is to develop perfect memory in order to be able to memorize all Shingon texts, though it is also believed to increase merit and grant prosperity in general. The oldest references to it come from the eighth century, and based on press coverage it is still performed today. ZUN actually never mentioned gumonji in a context which would stress the term’s Buddhist character. In Forbidden Scrollery Akyuu prays to Iwanagahime rather than to any Buddhist figures. I get the idea behind that, but I will admit I liked the portrayal of her religious activities in Ashiyama’s Gensokyo of Humans much more.

Gumonji aside, the second major point of interest is the connection between Uhō Dōji and Amaterasu. In the legend I’ve summarized above, they are obviously two separate figures, with one taking a subordinate position. This changed later on, though. At some point, most likely between 1419 and 1428, the two deities came to be conflated. As Bernard Faure put it, Uhō Dōji effectively came to be seen as the “Buddhist version of Amaterasu”. To be specific, as Amaterasu at the age of sixteen, presumably to account for the fact that a dōji would by default be a youthful figure. The treatise Uhō Dōji Keibyaku goes further and asserts that that Uhō Dōji manifests in India as the historical Buddha, Amida and Dainichi; in China as Fuxi, Shennong and Huang Di; and in Japan as Amaterasu, Tsukuyomi and Ninigi. In his astral role, he represents the planet Venus, but he can also manifest as Dakiniten and Benzaiten, in this context understood as respectively lunar and solar. He is also the creator of all of these astral bodies. The grandiose claims about Uhō Dōji, Amaterasu and other major figures were not exactly uncontroversial. It seems that especially in the eighteenth century the Ise clergy objected to them, presumably because they effectively amounted to their peers at Kongōshō-ji promoting their own deity to make the temple more important as a part of the Ise pilgrimage, which at the time enjoyed considerable popularity. The association between Amaterasu and Uhō Dōji nonetheless persisted through the Edo period, and despite protests voiced at Ise among laypeople Mount Asama was widely recognized as the third most important destination for participants in the Ise pilgrimage, next to the outer and inner shrines at Ise themselves. It is also quite likely that there was no shortage of people who would imagine Amaterasu looking just like Uhō Dōji. Ultimately the Uhō Dōji controversy was just one of the many chapters in Amaterasu’s long and complex history, and there was nothing particularly unusual about the claims made. There were quite literally dozens of Buddhist or at least Buddhist-adjacent figures she developed connections to (Bonten, Enma and Mara, to name but a few), and the Ise clergy took active part in this process. Buddhist reinterpretations of Amaterasu flourished especially through the Japanese middle ages. It was only the era of Meiji reforms that brought the end to this, cementing the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki inspired vision of Amaterasu as the only appropriate one. However, this is beyond the scope of this article. Worry not, though: the very next one I’m working on will cover these matters in detail. Please look forward to it. Bibliography

Anna Andreeva, “To Overcome the Tyranny of Time”: Stars, Buddhas, and the Arts of Perfect Memory at Mt. Asama

Talia J. Andrei, The Elderly Nun, the Rain-Treasure Child, and the Wish-Fulfilling Jewel: Visualizing Buddhist Networks at the Grand Shrine of Ise

William M. Bodiford, Matara: A Dream King Between Insight and Imagination

Bernard Faure, The Fluid Pantheon (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 1)

Idem, Protectors and Predators (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 2)

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Nobumi Iyanaga, Tachikawa-ryū in: Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia

Gaétan Rappo, Heresy and Liminality in Shingon Buddhism: Deciphering a 15th Century Treatise on Right and Wrong

Idem, “Deviant Teachings”. The Tachikawa Lineage as a Moving Concept in Japanese Buddhism

Yoshiaki Shimizu, The "Shigisan-engi" Scrolls, c. 1175

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nella penisola di Kii in Giappone, gli antichi sentieri del Kumano Kodo si intrecciano attraverso montagne boscose e attraversano antichi villaggi. Milioni di persone hanno viaggiato in questo sacro pellegrinaggio nel corso dei secoli, usando gli stessi sentieri coperti di muschio presi dai guerrieri samurai e dagli imperatori giapponesi. La leggenda narra che gli alberi, le cascate e le montagne siano le dimore di spiriti, rendendo il Kumano Kodo un viaggio in movimento di morte e rinascita. Nel periodo Heian (794 – 1185) il pellegrinaggio era in gran parte riservato all’élite religiosa e politica. La famiglia e la corte imperiale fecero un arduo viaggio dall'antica capitale di Kyoto a questa remota area, alla ricerca del cielo sulla terra. Storicamente, le montagne in Giappone erano considerate sia la dimora degli dei che uno spazio di ritrovo per gli spiriti dei morti. Per questo motivo, la regione montuosa di Kumano era sempre venerata dai seguaci dei sistemi di credenze politeiste del Giappone (che dovevano diventare collettivamente conosciuti come Shintoismo). Inoltre, il Kodo era uno sbocco ideale per le pratiche ascetiche, così come per la purificazione della mente, del corpo e dell'anima.

I siti sacri noti come Kumano Sanzan sono:

Kumano Hayatama Taisha

Kumano Nachi Taisha e il vicino Tempio Nachisan Seiganto-ji

Kumano Hongu Taisha .

Tutte le vie di pellegrinaggio Kumano Kodo conducono a Oyunohara , il Torii più grande del mondo, Questa struttura monolitica simboleggia la divisione tra il mondo secolare e quello spirituale; è l’ingresso ad un’area sacra.

Il simbolo di Kumano Kodo è il corvo sacro a tre zampe, Yata-garasu. Le tre zampe rappresentano il cielo, la terra e l’umanita’.

Kumano Sanzan ha combinato le fedi shintoiste e buddiste in una sola, conosciuta come Shinbutsu-shugo (letteralmente la convergenza del buddismo e dello shintoismo). L’idea che le divinità (kami) siano presenti in tutte le cose sulla Terra è profondamente radicata nella cultura giapponese dai tempi antichi. Il White paper ripiegato sotto forma di fulmini e appeso ai santuari delinea le aree in cui si ritiene che i kami presiedano. Dopo che il buddismo arrivò in Giappone nel VI secolo, i kami shintoisti diventarono, essenzialmente, manifestazioni di entita’ buddiste.

Shide, le stelle filanti di carta piegate a forma di bullone, spesso attaccate a Shimenawa (corda di paglia di riso), sono utilizzate per la purificazione nei rituali shintoisti e sono appese alle aree sacre. Lo shimenawa sulle cascate di Nachi indica la presenza di un kami (deità).

Gli Oji sono santuari sussidiari che fiancheggiano il Kumano Kodo e fungono da luoghi sia di culto che di riposo. La formazione di questi santuari è stata attribuita agli asceti di montagna Yamabushi, che storicamente servivano come guide di pellegrinaggio.

Più di 1.200 anni di storia shintoista e buddista sono documentati in queste montagne, motivo per cui il Kumano Kodo è stato insignito dello status di Patrimonio Mondiale dall'UNESCO.

“Questa è l’unica area sacra del mondo in cui due religioni coesistono in perfetta armonia”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Religious Imageries in JJK: The Conflicting Views of Shinto and Buddhism.

Disclaimer: This is not an explanation post, this is an observer post. I will try to sum up what I have observed so far.

Let's begin with the definition and history of both Shinto and Buddhism.

Shinto [神道]: Combined with the kanji of God/Kami (神) and Road /Michi(道), Shinto literally means The way of the God(s). It is the indigenous religion of Japan and is as old as Japan itself.

Shinto belief is polytheist and animistic as it has almost 8 million gods that are derived from nature and natural things. This religion revolves around "Kami". Kami can be manifested from anything, but the most important Kami are the natural ones.

Sun, Rain, Earth etc. The most important central Kami is Amaterasu the Kami of the Sun. The exact history of Shinto is untraceable but it was mentioned in the Yayoi Period (300 BCE to 300 CE) of text.

Shinto describes the world as a inhabitant of the human and the kami they worship. It describes the world as founded by the kami and once humans/ living beings pass away they become kami as well.

It is safe to say that Shinto belief described humanity as living being as a whole, where even after death they don't living. The idea of morality or immorality is also absent from it. The existence of Kami is the manifestation of humanity itself and not separated from human beings.

Fun Fact: Chinese indigenous religion 'Dao' has the same characters as Shinto's kanji. So it might be possible that Shinto actually comes from Chinese Daoism.

Buddhism: Buddhism is an Indian religion. It revolves around the teaching of Buddha. Buddha is no myth. Even though convoluted, early texts gives his name as "Gautama" and he lived around 5th to 6th Century BCE.

In India his name is mostly known as "Siddharth". He was born in Lumbini in present day Nepal and grew up in Kapilavastu. The border of India and Nepal, a town of the Ganges plain of present day Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

The most notable person who helped spread Buddhism around India so much that it was spread in the NEA and SEA is Emperor Asoka (304-232 BCE) from the Maurya Empire (322-180 BCE).

Buddhism circles around the suffering of human, the circle of life and Karma (deed). Where a soul is constant as it is being born in this world as human, it goes through the cycle of life (suffering) and it dies.

It also talks about Dharma as the ultimate truths, also that humans are born to fulfill a certain role. Moksha: The liberation from the earthly desire which should be the ultimate goal of a human being.

It also draws the line between God and humans as Gods are separated from the earthly matters and pushes the idea of Gods creating the universe and the creating the humanity.

The Mix of both Religion:

Though the idea of Shinto and Buddhism is pretty contradicting it existed with each other for centuries.

Even though Buddhism entered in japan in Yayoi Period (250-538 AD), it became popular in Asuka Period (538-710) due to buddhist sect taking the rein of the country. Initially Buddhism and Shinto coexisted and even mixed with each other. It was called Shinbutsu-Shougou. However, later it was forcefully separated by Japanese nationalists in Meiji Era (1868-1912) and Shinto became the state religion of Japan with the Emperor being worshipped as Kami the descendants of Amaterasu.

Cursed Spirit: The reason I am writing this is not because the obvious depiction of buddha, Buddhist shrines and mention of clans and sects etc. What caught my interest was that the idea of "Cursed Spirit".

The textbook explanation of Cursed Spirit is that the reaction of human emotions but as we see it is actually the manifestation of human existence. As long as humans will exist, curses will also exist.

Which pretty much resembles the idea of Kami.

The timeline: The golden era of jujutsu was Heian Era which historically existed between 794-1185 AD. Almost a century after Buddhism was introduced in Japan. Also in that era Sukuna rose up as the king of curses. Which may indicate the clans existed even before and Sukuna existed throughout.

Characters like Kenjaku and Tengen their birth and living timeline are unknown but they might just as be as old as Japan, like Shinto.

Getou and Megumi are the only two people who can control curses as Shikigami. Which is another japanese Shinto belief that has also been associated with "Curses" during Heian Era.

The people who used to control Shikigami were called Onmyoji (Yin-Yang Master).

Both of them were either antagonised or villfied by the jujutsu society at one point.

Also the most important part that made me think about this is...Sukuna's domain.

This resembles an average Shinto shrine...

The Tori is missing.

Insanity.

Anyways. I am not saying that Gege is making one religion look bad and another look good. It's not true and actually far from it. Though contradiction, Gege shows the good and bad of both sides. Kenjaku is bad and the higher ups are as worse as him.

Personally I think this is a battle of belief of the world with a main character emerges with no beliefs at all. Itadori Yuuji hates Sukuna but not by the virtue of being Gojo's student but his own opinion about him. In the latest chapter he says "Human beings are not a tool, so nobody's existence is premediated." Which contradicts the idea of "Dharma".

The message might be "If you want to change the world, you have to diverge from the existing path and forge your own."

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyoto

Heian Jingū

Enshrined Kami: Emperors Kanu and Komi, the first and last emperors to reside in Kyoto

Prayers Offered: Peace, the well being of the family, and protection against danger

Heian Jingu enshrines Emperor Kanmu (r. 781-806), who created Heiankyo (present-day Kyoto). While he was the only kami enshrined when the shrine was built in 1895, Emperor Komei was added in 1940 on the 2,600th anniversary of the nation’s founding. It was an unusual case, in which one emperor was enshrined as a kami more than a thousand years after his death, and a second emperor (only distantly related to the first) some forty-five years later. The shrine was established as much as a commemorative emblem of the past glory of Kyoto as a religious institution. Of course, it is not the only one in Japan to enshrine emperors. But the others are simply shrines, whereas Heian Jingu is strongly symbolic, dedicated to both the founder of the old capital and the last emperor to reside there. Kanmu is revered as a clever and creative leader who built the city that was the center of Japanese culture for the better part of a thousand years. Komei, on the other hand, is best known for his anger at the forced entry of Commodore Matthew Perry’s black ships in 1853 and the edict he issues in 1863—impossible by then to obey—to “expe, the barbarians.” By the time of Komei’s death at the age of just thirty-five in 1867, the country was in disarray, and the wholesale import of Western culture into Japan had begun. But what was hardest for the citizens of Kyoto to swallow was the prospect of the young Emperor Meiji relocating to the country’s new eastern capital, Tokyo.

—Pages 106-107

Hirano Jinja

Enshrined Kami: Imaki no Sume Ōkami, Kudo no Ōkami, Furuaki no Ōkami, Hime no Ōkami

Prayers Offered: To find love and marriage, revitalization and new beginnings, protection against danger, and safe childbirth

The four kami enshrined in Hirano Jinja are neither widely known nor well understood. The shrine describes Imaki okami as a god of revitalization, Kudo okami as a deity of the cooking pot, Furuaki okami as a deity of new beginnings, and Hime no okami as a deity of fertility and discovery. The Engishiki (967) mentions the shrine as guardian of the imperial household kitchen. It seems that Emperor Kanmu gathered these kami together in one shrine and founded Hirano Jinja in the northwest corner of Kyoto to act as a protector of both the city and of the imperial court. Kitabatake Chikafusa (1293–1354) was apparently the first to consider the kami as ancestral, assigning them to the Tahira, Minamoto, Oe, and Takashina branches of the imperial line…Shinto scholar Ban Nobutomo (1773–1846), in his research into banshin (foreign kami), stated that the kami of Hirano are ancestors of the Paekche dynasty. However a spokesman for the shrine believes Nobutomo erred in his translation of certain words, which drew him to an erroneous conclusion. A related theory identified Hime no Ōkami with the mother of Kanmu, Takano no Niikasa. If so, it may be one reason why Kanmu, whose mother was descended from a Korean king of Paekche, valued the shrine. Perhaps incidentally, the term “Imaki” is applied to Korean immigrants in the Nihon shoki…

…considered “eminent kami”…received regular offerings from the imperial palace. The kami of Hirano were considered very powerful, and the hereditary priests who controlled the shrine were from a clan of tortoise-shell diviners called the Urabe. Tortoise-shell divination (kiboku), imported from China through Korea, became one of the main forms of divination regulated under the Council of Kami Affairs (jingikan). The Urabe were an important clan of hereditary Shinto priests (jingidoke) considered one of the “three houses of Shinto” along with the Shirakawa and Nakatomi clans. They divided into the Hirano and Yoshida clans, with the Yoshida becoming one of the most influential kami clans throughout the late medieval and Edo periods. The Yoshida controlled the right to appoint new priests and rank shrines. The Hirano were transcribers of the classics and experts on the Nihon shoki. A compilation of research, called Shaku Nihongi, written by Urabe Kanekata, earned the family the sobriquet “house of the Nihon shoki.”

—Page 109

…In the Heian period it was considered one of the “major seven” shrines, along with Ise, Iwashimizu, the Kamo shrines, Matsuo, Fushimi Inari, and Kasuga. It was associated with a shinbutsu shugo (syncretistic) belief known as the “thirty tutelaries” (sanjubanshin), which originated with the Tendai monks of Mount Hiei in the ninth century. This was a belief that thirty kami (presumably chosen by Tendai monks) alternated daily to protect the Lotus Sutra. The kami of Hirano was also included in this grouping.

—Pages 110

Iwashimizu Hachimangū

Kami Enshrined: Hachiman okami (also known as Hondawake no mikoto and associated with Emperor Ojin), Hime okami, and Jingu Kogo (Okinagatarashihime no mikoto).

Prayers Offered: Protection against danger, safe childbirth, and the attainment of goals.

Iwashimizu represents the emergence of Hachiman as a god of war as well as exemplifying the Kami’s identification with Buddhism. It is also significant as the the kami’s second enshrinement close to a capital city and seat of power. (For the beginnings of Hachiman worship, see the entry for Usa Jingu.) The first was in Tamukeyama Hachimangu in Nara as protector of the Great Buddha of Todaiji in 752. After that time, the connection between Hachiman and the imperial court grew stronger. In 855 Hachiman was again called upon to “protect the nation” when the head of the Great Buddha of Todaiji suddenly fell off during an earthquake. Emperor Montoku launched a campaign to rebuild the Buddha shortly afterward and the first place he turned for assistance was Usa Jingu. For the first time the imperial message addressed Hachiman as “awesome Daibosatsu” (great Buddha) and called upon him to “protect the emperor [country] to eternity.” At the same time, a statement was issued that the kami who assisted in this project would gain “merit” (in the sense of Buddhist enlightenment). It was an important step in acknowledging kami as “trace” manifestations of the “original ground” (honji-suijaku) of the Buddha.

—Page 112

There is an interesting story related to the bamboo of Otokoyama. In 1880 Thomas Edison sent one of his researchers, William H. Moore, to Japan in search of good bamboo to use as light bulb filaments. It is said that he had tested six thousand materials, but the bamboo taken from a fan lasted the longest—200 hours. Moore was directed to Kyoto and more specifically Otokoyama, and the bamboo he found there made a filament that lasted close to 1,200 hours. Ironically, the rock that makes up Otokoyama is a poor surface for growing bamboo, as a result of which the type that grows there is harder than normal. It became part of Edison’s incandescent lamp for the following ten years, and the inventor maintained close ties to Japan… It is strange to think that the mammoth Japanese electric industry began with Edison, and that Edison’s light bulb began with the grace of the kami of Iwashimizu Hachimangu. Today there is a monument to the inventor on Otokoyama, and a Festival of Light has been observed since 1999. It is also possible to purchase ema votive plaques bearing an image of Edison.

—Pages 113-114

#Heian Jingū#Heian Jingu#Hirano Shrine#Iwashimizu Hachimangū#Iwashimizu Hachimangu#Shinto#Shinto Shrines A Guide#Photos#Kami#shinbutsu shugo#Buddhism#Thomas Edison

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any more headcanons about the Senju?

Here is a loooooong post with assorted collection of Senju clan HCs for you! They main apply to the Warring States era and early Founders Era. Some of them are new, some I've picked up from some of my older posts.

Disclaimer: This is HC's of the general culture. People are people and won't act in perfect alignment with the norms or social etiquette that is encouraged, may interpret them differently or disagree with them entirely. Hashirama and Konoha also brought drastic change which ended or drastically changed some of these traditions and norms.

CW for a bunch of stuff including but not limited to war, injury, pregnancy, childbirth, sex, abuse, death and more. Reader discretion is advised.

As far as religion goes the Senju lean more into Shinbutsu-shūgō (Syncretism of Shintoism and Buddhism), but a number consider themselves to have little to no attachment to spirituality. Ancestor worship is the most commonly displayed spiritual practice among Senju.

Ashura fought and worked hard for his abilities and gained much from the support of others, and the Senju towards the end of the WS era have managed to breed certain beneficial traits into becoming extremely common within their clan. This includes possessing a genetic anomaly that gives 9/10 Senju a natural affinity for two of the five basic chakra natures, as opposed to just one which is the universal norm (with the exception of a handful of clans with rare kekkei genkai). Another incredibly common trait in Senju was in fact passed on from their ancestor Ashura, which is immense physical strength, stamina and energy (see more notes in next point). Their natural physical strength and muscle density is immense, allowing them to achieve feats that would otherwise be incredibly difficult or impossible to achieve without enhancing your ability with chakra and pushing the natural limits of your body. Stamina can be used to mold into chakra for performing ninjutsu techniques. Having lots of stamina allows them to perform many or stronger techniques while still having energy left to remain physically active. Their strong life-force, which they share with their relatives the Uzumaki, makes them hard to kill. They can be severely injured but still cling to life, even if they may not be able to keep fighting at the time. These traits have allowed them to keep up with the rival and otherwise unmatched Uchiha clan. Their average is what others would consider impressive.