#saint pere

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The History of Santa Claus

Santa Claus—otherwise known as Saint Nicholas or Kris Kringle—has a long history steeped in Christmas traditions. Today, he is thought of mainly as the jolly man in red who brings toys to good girls and boys on Christmas Eve, but his story stretches all the way back to the 3rd century, when Saint Nicholas walked the earth and became the patron saint of children.

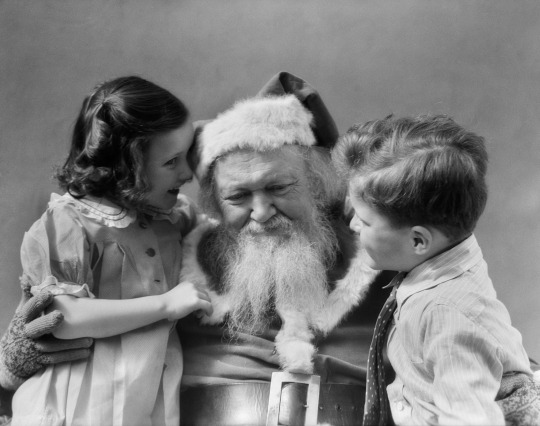

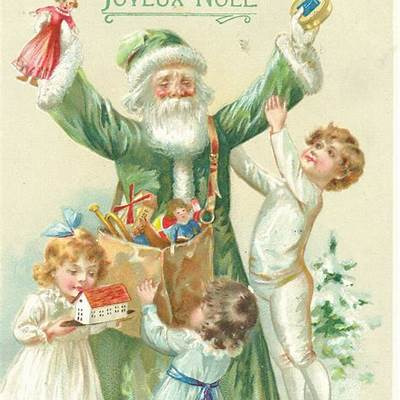

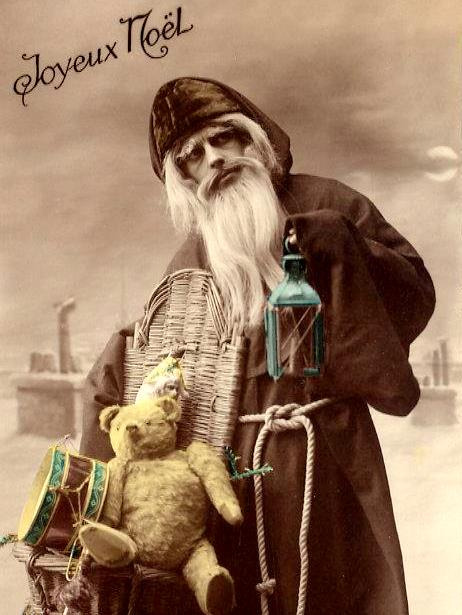

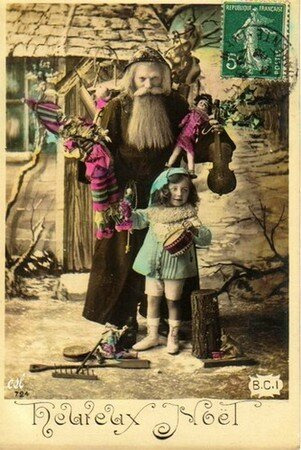

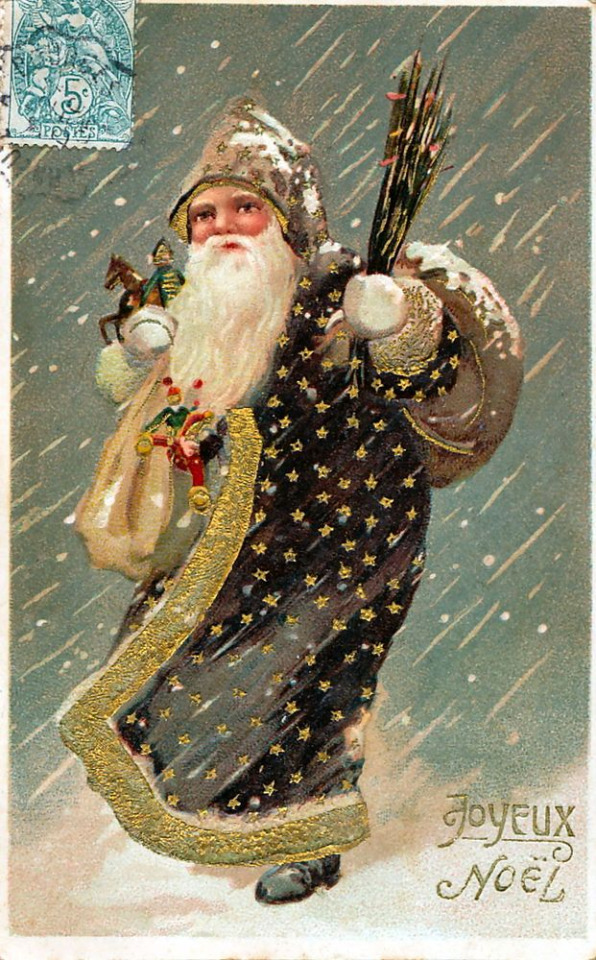

Santa Claus wasn't always "chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf." PHOTOGRAPH BY CLASSICSTOCK/CORBIS

The Legend of Saint Nicholas

The legend of Santa Claus can be traced back hundreds of years to a monk named St. Nicholas. It is believed that Nicholas was born sometime around A.D. 280 in Patara, near Myra in modern-day Turkey. Much admired for his piety and kindness, St. Nicholas became the subject of many legends.

One of the best-known St. Nicholas stories is the time three young girls are saved from a life of prostitution when young Bishop Nicholas secretly delivers three bags of gold to their indebted father, which can be used for their dowries. He was very religious from an early age and devoted his life entirely to Christianity. The strict saint took on some aspects of earlier European deities, like the Roman Saturn or the Norse Odin, who appeared as white-bearded men and had magical powers like flight. He also ensured that kids toed the line by saying their prayers and practicing good behavior. In continental Europe (more precisely the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, the Czech Republic and Germany), he is usually portrayed as a bearded bishop in canonical robes.

During the Middle Ages, often on the evening before the anniversary of his death, December 6, children were bestowed gifts in his honour. By the Renaissance, St. Nicholas was the most popular saint in Europe. Even after the Protestant Reformation, when the veneration of saints began to be discouraged, St. Nicholas maintained a positive reputation, especially in the Netherlands.

Coming to America

In the Netherlands, kids and families simply refused to give up St. Nicholas, or Sinterklaas as the saint is called in Dutch, as a gift bringer. They brought Sinterklaas with them to New World colonies. St. Nicholas made his first inroads into American popular culture towards the end of the 18th century. In December 1773, and again in 1774, a New York newspaper reported that groups of Dutch families had gathered to honor the anniversary of his death.

The name Santa Claus evolved from Nick’s Dutch nickname, Sinter Klaas, a shortened form of Sint Nikolaas (Dutch for Saint Nicholas). In 1809, Washington Irving helped to popularize the Sinter Klaas stories when he referred to St. Nicholas as the patron saint of New York in his book, The History of New York. As his prominence grew, Sinter Klaas was described as everything from a “rascal” with a blue three-cornered hat, red waistcoat, and yellow stockings to a man wearing a broad-brimmed hat and a “huge pair of Flemish trunk hose.” An appearance that was more derived from the English 'Father Christmas' and was quite different from the Dutch Sinterklaas.

Santa Equivalents Around The World

Eighteenth-century America’s Santa Claus was not the only St. Nicholas-inspired gift-giver to make an appearance at Christmastime. There are similar figures and Christmas traditions around the world.

The English legend explains that Father Christmas visits each home on Christmas Eve to fill children’s stockings with holiday treats. Father Christmas dates back as far as 16th century in England during the reign of Henry VIII, when he was pictured as a large man in green or scarlet robes lined with fur. He typified the spirit of good cheer at Christmas, bringing peace, joy, good food and wine and revelry. As England no longer kept the feast day of Saint Nicholas on 6 December, the Father Christmas celebration was moved to 25 December to coincide with Christmas Day.

In the Netherlands and Belgium, the character of Santa Claus competes with that of Sinterklaas, based on Saint Nicholas. Santa Claus is known as de Kerstman in Dutch ("the Christmas man") and Père Noël ("Father Christmas") in French. For children in the Netherlands, Sinterklaas still remains the predominant gift-giver in December mostly celebrated on Sinterklaas evening the day before 6 December.

In Germany, the Christmas season is marked by the presence of two significant figures: Weihnachtsmann and Das Christkind or Christkind'l. Weihnachtsmann, a term that literally translates to "Christmas Man," is the German counterpart to Santa Claus. In contrast, Das Christkind, meaning "The Christ Child," represents a more traditional and religious aspect of German Christmas celebrations. Christkind was believed to deliver presents to well-behaved Swiss and German children on Christmas Eve. The name "Kris Kringle", a common variant of Santa in parts of the United States is derived from Christkind.

In Nordic folklore, the figure known as Tomte or Jultomten holds a special place in Christmas traditions. Originating from Swedish and Scandinavian mythology, Tomte is a small, mythical creature often depicted as a friendly, bearded being resembling a garden gnome and wearing a red cap. During the Christmas season, Tomte takes on a role similar to that of Santa Claus, delivering presents to children in a sleigh drawn by goats on the night of December 24th.

In Icelandic folklore, the Yule Lads, or "Jólasveinar," are mischievous characters associated with the Christmas season. These thirteen brothers, sons of the mountain-dwelling trolls Grýla and Leppalú��i, are known for their playful antics and sometimes slightly sinister behavior. Traditionally, the Yule Lads would visit homes in the thirteen nights leading up to Christmas, each leaving small gifts or playing pranks depending on the behavior of the children.

In Italy, the Christmas season is marked by the presence of two iconic figures: Babbo Natale and La Befana. Babbo Natale, the Italian counterpart to Santa Claus, shares many similarities with the global image of the jolly gift-bringer. The other Italian icon, La Befana, is a unique and beloved figure in Italian folklore. Unlike the festive and plump Babbo Natale, La Befana is portrayed as an old woman, often depicted as a haggard but kind witch. According to tradition, La Befana visits homes on the night of January 5th, leaving small gifts and sweets for children who have been good and a lump of coal for those who have been naughty.

In French-speaking regions, the iconic figure associated with Christmas gift-giving is Père Noël, also known as Papa Noël. Père Noël is akin to the global representation of Santa Claus, often depicted as a jolly and benevolent character who travels in a sleigh pulled by reindeer, embodying the spirit of generosity and joy during the festive season.

In Spain and many Spanish-speaking cultures, the Christmas season unfolds with the anticipation of visits from both Papa Noel and Los Reyes Magos, offering children a delightful blend of traditions. Papa Noel, the Spanish equivalent of Santa Claus, is eagerly awaited on the night of December 24th. Following this, the celebration continues with the arrival of three kings known as “Los Reyes Magos” on January 6th. This holiday is known as Three Kings' Day or Día de Reyes. On the night before Día de Reyes, children place their shoes or small containers filled with hay under their beds for the Kings' camels. In return, Los Reyes Magos leave gifts, sweets, and small toys, creating a magical and cherished experience for children who wake up to the joyous surprises.

In Russia, instead of Santa, there is Ded Moroz and his granddaughter Snegurochka, who deliver gifts to children on New Year’s Eve. Children would sing Russian songs around the yolka.” A yolka is a coniferous tree similar to a Christmas tree. Ded Moroz is described as a grandfather with a long white beard.

Mikuláš (also known as Saint Nicholas) is the father of Christmas in the Czech Republic, as well as in Hungary. Mikuláš looks like the Pope and Santa combined. However Mikuláš is not always the person delivering presents on Saint Nicholas Day, it is typically believed to be Jesus. Saint Nicholas Day in the Czech Republic is predominantly celebrated on Dec. 5-6, although depending on the region, it is also celebrated on Dec. 25. Children put a boot out on the eve of Saint Nicholas Day and hope to find it full of candy and toys from Jesus in the morning. Bad kids can expect only a wooden spoon in their shoe.

In Japan Hoteiosho, or Hotei, is the equivalent of Santa pictured as a fat man with eyes in the back of his head who can tell if kids are naughty or nice. He is also known as the “Laughing Buddha,” because he is often depicted with a jovial face and surrounded by grinning children. Hotei is one of the Seven Lucky Gods, stemming from ancient Chinese and Indian religion. Hotei may have been based on a real person, named Budai, a man who died in 916 A.D. and was later worshipped in Buddhist practice.

So far a selection of customs and traditions similar to Santa Claus. Of course there are more, and in many traditions parallels to other cultures can be found.

sources; history.com, nationalgeographic.com, wikipedia

#santa claus#saint nicholas#kris kringle#sinterklaas#father christmas#pere noel#papa noel#history#jultomten#christmas eve#december 6#december 24#yule lads#weihnachtsmann#christkindl

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cimetière du Père Lachaise à la Toussaint, 2017.

#urban landscape#cemetery#fowers#pere lachaise#paris#france#2017#all saints day#photographers on tumblr

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Port-Saint-Père, France

A lioness cares for her cubs as they enjoy the outdoors for the first time, at the Planète Sauvage zoological park near Nantes

Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

#afp via getty images#photographer#port-saint-pere#france#lioness#lion#lion cubs#animal#mammal#planete sauvage zoological park#nantes#nature

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎅🎄 Personnages du folklore de Noël dans différentes cultures. Partie 2

#christmas#noel#drawing#art#character design#charadesign#saint nicolas#saint nicholas#krampus#pere fouettard#christkindel#christkindl#nutcracker#nussknacker#casse noisette

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marshals of the First French Empire buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery

Yesterday was the anniversary of the opening of the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris in 1804. @captainknell mentioned that they’re interested in seeing the tombs of the Marshals who are buried there and I realized that I actually have some pics of them. These are not all the Napoleonic figures buried there; not even close! There are actually quite a few notable figures buried at this cemetery.

Credit to the amazing photographer: Stéphane Charton-Thomas.

Marshal Suchet:

Marshal Grouchy:

Marshal Saint-Cyr:

Marshal Lefebvre:

Marshal Davout:

Marshal Ney:

Marshal Masséna:

Marshal Kellermann:

#Père Lachaise Cemetery#Père-Lachaise Cemetery#cimetiere du Pere Lachaise#cimetiere#cemetery#graveyard#gravesite#tomb#tombs#tombstone#tombstones#graves#napoleon’s marshals#Suchet#Grouchy#Saint-Cyr#Lefebvre#Davout#Ney#Masséna#Kellermann#sepulcher#sepulchre#frev#french revolution#napoleonic#napoleonic era#Paris#France#first french empire

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dorothy Day now and forever! We have the largest archive of her works in our campus archives!

A fellow Golden Eagle, I see ;)

Another vote added for Dorothy Day!

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Val Thorens - Savoie - Alt. 2300 m.

Vue générale;

Massif de Peclet-Polset (3566 m.)

#Val Thorens#Savoie#Massif#Peclet-Polset#Peclet#Polset#Des Saints Peres#Col de Thorens#Glacier de Peclet

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rehearsal for festa major. Video shared by Món Casteller.

In Tarragona (Catalonia), there is the tradition that on the day after festa major (traditional Catalan holiday celebrated in each town or city on their patron saint's day), which in Tarragona is celebrated on September 24th, the four castellers groups of the city go up and down the stairs in front of the city's cathedral doing a pilar and continue walking the pilar through the down-hill street until they cross all the Font square near it. The whole process is about 500 meters and takes each group an average of 10 to 15 minutes to do.

Castellers are the Catalan tradition of doing "human towers", which can have many people on each layer or floor. A pilar is when the "tower" only has one person on each floor, like you can see in the video. In this video, you can see the group Colla Castellera de Sant Pere i Sant Pau practising going down the stairs in front of the Cathedral.

#tradicions#castellers#tarragona#catalunya#catalonia#castells#cultures#culture#anthropology#travel#europe#traditions#folk culture#festa major#catalan#catalan culture#wanderlust#explore#ethnography

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Dec. 25, 2016 photo shows women in procession outside Saint Benedict Church during Marujada religious celebrations in honor of the Catholic Saint in the fishing town of Braganca, Brazil. For the procession, women wear blue skirts and white shirts and don white circular feathered, hats streaming colorful ribbons. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pere Fouettard

Pere Fouettard means “Father Whip” in French. This character is also known as Hans Trapp in Alsace; Ruprecht in German folklore, Zwarte Piet in Dutch folklore, and Houseker in Luxembourg). He is a shady figure who goes out with Saint Nicholas on or about December 6th. Pere Fouettard gives children who are disrespectful spankings, while Saint Nicholas gives them presents. The delivery of coal or beets has taken on the role of spankings in several parts of France and Belgium.

Although depictions of Pere Fouettard may vary somewhat from country to country, he is often represented as a frightening figure, dressed in fur, with a long beard, a gloomy visage, and untidy hair. He often carries a whip, a staff, or a bunch of twigs for protection. He threatens to stuff rebellious kids in his big bag and haul them away if they don’t behave or say their prayers...

Pere Fouettard: A Bogeyman, Polar Opposite of Santa Claus

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Humanized Polar Express

My take on a humanized/anthro/sentient Polar Express.

Appearance:

A Baldwin s3 2-8-4 and Pere Marquette 1225 hybrid locomotive man. Wears a puffer jacket w/ traditional Inuit fur-trimming, ice skates, mittens, and three jingle bells on the hood.

Personality:

courageous, intelligent, wise, skeptical (formerly), faithful, practical, aloof, blunt, hardy, generous, sacrificial

Backstory:

The Polar Express initially worked on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in North America. His real name is Kuvianak, meaning "joy". He is of Inuit heritage: can speak Aivilimmiutut and knows how to survive in hardy weather. Kuvianak died from crashing on ice during an extreme blizzard. He was not scrapped, but put on display until The Christmas Spirit whisked him away.

Kuvianak is now a magical holiday train who brings children from around the world to The North Pole, where they meet Saint Nicholas. When he was assigned this job, he was hesitant. Christmas is a Christian holiday. But Kuvianak was a Pagan; he didn't want to let go of his traditions.

Converted to Christianity, The Polar Express saw Christmas for what it truly meant. His motto: believe. "Though I've grown old, the bell still rings for me as it does for all who truly believe."

#my writing#writing snippet#character bio#humanized#humanization#the polar express#humanized locomotive#steam locomotive#humanized design#christmas movie#my art#long post

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can I ask this question?

What's the deal with Pére Noel?

Do you any information about him?

I really found very few information about Pere Noel before he was synchronized with Britain's Father Christmas and US' Santa Claus.

Was he just a french version of Father Christmas, focused in adult festivities and merrymaking before becoming a gift-bringer like Santa and St. Nicolas?

Is he today any different from Santa and Father Christmas?

I read that in some parts of France St Nicholas is still the main gift-bringer figure, so I'm confused about the events that led to Pere Noel being a major holiday figure in the French context.

This ask actually needs a very long and complex answer that I will provide below, because the topic of the "Père Noël" is extremely complex...

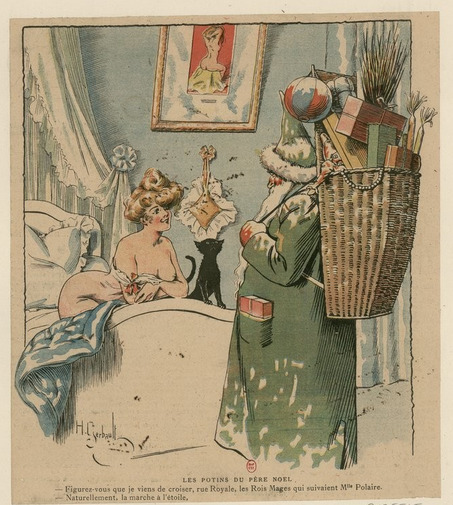

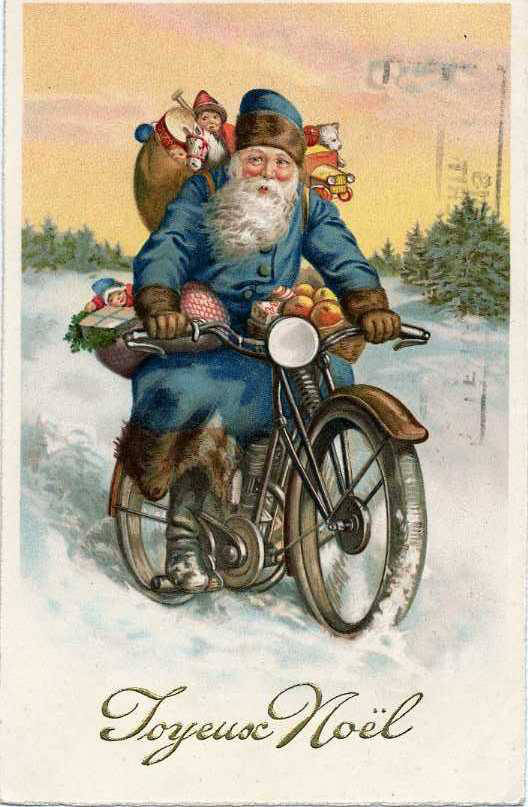

My guess is that you are referring to the "Père Noël" that appeared in Chris Schweizer's set of "Father Christmas cards" - which appears here if you want the original post, but to clarify I will copy the art below for the sake of the explanation -

This is not the current day "Père Noël". You will NOT see this guy around in the streets today. In modern France, "Père Noël" is the name of the French version of Santa Claus. Or rather, French people call Santa Claus "Père Noël". Current day's Père Noël is just a Santa Claus copypaste. Now, "Père Noël" literaly means "Father Christmas" in French, so one would expect him to be much closer to the British Father Christmas... But yes and no. Yes because it is another incarnation of Father Christmas that predated the American Santa Claus, but no because the French Père Noël has a different (though similar) iconography than the British Father Christmas.

Overall, if you recall my previous post, it is the same thing as with the "proto-Santa Claus/Kris Kringle" of 19th America (mischievious elf-like figure wrapped in brown furs) versus the 20th century American Santa Claus (jolly old man in red and white). "Père Noël" was the figure that was the placeholder of the gift-giver before the arrival of the American Santa Claus in the post WWII world (as with all things American in France, it was imported by the Americans that helped set France free). The earliest records of Père Noël appearing are from the mid-19th century - George Sand writes in her 1855 biography that as a kid she was waiting for "little father Christmas", this "good elder with his white beard", that dropped at midnight from the chimney to place shoes in the "petits souliers" (little slippers" of the kid) ; while an humoristic newspaper of 1848 wrote a dialogue where Père Noël knocks at someone's door - only for the person not to believe them, and saying he should be entering by the chimney not the door. Here, despite the name linking him to the British Father Christmas, he bears the marks of the proto-Santa Claus/Kris Kringle of 19th century America (such as the small size, explaining why he fits through chimneys). But it is all unclear as the figure was definitively not set in stone. In fact, in the second half of the 19th century, there was a certain fleeting between "Père Noël" (Father Christmas), "Bonhomme Noël" (Old Man Christmas/Christmas Man) and "Petit Noël" (Little Christmas, aka a variation of "Little Jésus", a French variant of the German Christkindl).

The thing with France is that it is a cultural crossroad - and this explains the diversity of Noël/Christmas traditions. For example in Provence there is a strong focus on the Epiphany and the Rois Mages (the Three Magi), similar to the traditions of the Reyes Magos in Spain ; while Eastern France truly kept alive the Saint Nicholas tradition typical of Central Europe (Netherlands, Germany, etc). And that's without counting local figures like Tante Arie... Anyway. So yes, saint Nicholas was a very popular gift-giver in France for a long time because France was a deeply Christian country (First Daughter of the Church), and the tradition stayed in the "Germanic" or Dutch-influenced parts of France (North, North-East). But in the rest of the country, Père Noël emerged. A continuation of Saint Nicholas-Sinterklass (still an old man, still with a donkey/horse, carrying gifts in a wicker basket), but with less religious symbols (while he still looks like a monk in some depictions, he never looks like a bishop and never has any overt Christian symbols). There's also the whole Père Fouettard as the French evil counterpart of Père Noël, the same way Saint-Nicholas/Sinterklaas has many "dark companions", but that's another story...

That all being said, the reason Père Noël was so easily "morphed" or "transformed" into the American Santa Claus is because, while he existed as a figure of Christmas folklore in France, he was not actually... defined. There was no specific image of him, no specific attribute, no lasting tradition - he existed as an archetype, as a general image, as a figure everybody knew by name but nobody agreed on how to depict. Sometimes he was closer to Saint Nicholas/Sinterklass by appearing as a thin monk-like old man with his donkey ; other times he was similar to the British Father Christmas by being a larger man dressed in green ; other times yet he was rather similar to the traditional embodiments of winter by appearing as a being wrapped in a grey or white large cloak... You've got some fleshy red-dressed Père Noël with fur-lined clothes similar to the future Santa Claus, just as much as you have skinny brown, blue or purple Père Noëls. There was a father Christmas but more as a general idea. And it is this inconsistency, this "freedom" of depiction that led to the American image of Santa Claus easily becoming the new face of Père Noël.

For example, here are various images of what the pre-Americanization Père Noël looked like:

You will notably notice that many of the visuals used in these Christmas pictures can also be found in England as the Father Christmas there tried out and found various looks - which is why it is sometimes hard to differentiate Victorian Christmas cards from French ones, and shows again how the French Père Noël is basically a cross between Father Christmas and Saint Nicholas.

In conclusion, long story short, Père Noël is not actually truly "French". It is a French figure, but born of the arrival of the British Father Christmas figure into a very Catholic France that fused him slightly with Saint Nicholas, hence a slightly more "religious" look ; and threw in some traditional Father Winter/Old Man Winter imagery to the lot. Overall, when you say "Father Christmas", you also speak of "Père Noël" as they are basically the same figure, with no massive difference, just slight alterations and a different cultural context.

And today Père Noël is just Santa Claus. BUT some elements that were part of the "old" Père Noël legend stuck around even in the modern Americanized incarnation, such as the habit of referring to "petits souliers" (little slippers) as the place he is supposed to leave gifts.

#french folklore#christmas lore#santa claus#father christmas#père noël#saint nicholas#the evolution of santa claus#the evolution of Christmas#christmas#noël

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aulard on Herault de Sechelles

Okay here we go, another author who is absolutely in love with Herault. I’m not even joking, Aulard is completely head over heels for this man. So here is his chapter on Herault de Sechelles in his book Les orateurs de la Législative et de la Convention: l'éloquence parlementaire pendant la Révolution française (Tome 2). Link here: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5441755r

A few notes:

When I make a translation, I am not agreeing or disagreeing with anything an author says. It's important to keep in mind that every author has their own agenda and writes about historical events and historical figures within the context of their own viewpoint. Aulard , as you will see, is a keen supporter of Danton, and he labels Herault as a Dantoniste throughout the entire chapter. Whether Herault should be considered as a strict Dantoniste is, in my non-professional opinion, up for debate. A lot of people are still not aware, for example, that he and Fabre d'Eglantine were arrested separately to, and before Danton and Camille were arrested, and it was only afterwards that it was decided that they should be tried together.

Aulard neglects to give sources for several of the statements that he makes and is very condescending towards Robespierre and Saint-Just. He also seems to try to justify Herault’s actions during the revolution by saying that he was mostly acting to keep Robespierre off his back. I personally think this is incredibly injurious to Herault, who was an active participant in the Revolution – we have no reason to believe, as many would like to, that he was only pretending to support the Revolution to survive, rather than because he genuinely believed in its principles.

Also, apparently Herault bought a lottery office for one of his mistresses and I just … cannot deal with this man.

Anything with an asterisk is my personal note/observation. I will take the time to remind every one again that my French is dismal and that is why I always link the original. Huge thank you again to @ans-treasurebox for helping me with translating parts of this and also to @orpheusmori who had to sit there and put up with me losing my mind over Herault on the Discord for several nights in a row.

Chapter VIII – Herault de Sechelles

I

Herault de Sechelles was the ornament of the Dantonist party. A man of the court and of noble family (1), a classical and lucid spirit, an orator enamored with academic elegance, he forms a perfect contrast with the rusticity of Legendre. When he was very young, he was introduced to Marie Antoinette by her cousin Madame de Polignac, pleased her, and obtained from her a position as a lawyer at the Chatelet. He won great success there through his talent for speaking and by the choice of his causes, calculated to interest the sensitivity of his protectors. "There is applause on all sides, says one of his biographers, at his eloquent indignation against the ingratitude of a pupil towards his tutor and against the odious behavior of an opulent girl who had abandoned her mother in need."

(1) His grandfather had been lieutenant general; his father, colonel of the Rouergue regiment, had perished gloriously at the Battle of Minden (Jules Claretie, Les Dantonistes, p. 317). He was also a nephew of the Marshal de Contades (Souvenirs de Berryer, I, 1)

In 1779, at the age of 19, he published Eloge de Suger. Serious and charming, he was soon called, by the favor of the Queen (1), to the post of Advocate General in the Parliament of Paris. The parliamentarians, he would say, hated him, either because of the rapidity of his fortune (2), or for his philosophism.

(1) She sent him, it is said, a scarf embroidered with her own hand. - His last speech as a lawyer was a triumph: the magistrates and the audience accompanied him, applauding, to his carriage. Journal de Paris of August 7, 1785, quoted by J. Claretie, ibid.

(2) La pere de Berryer's (ibid.) says that he had been appointed after a hard fight and he adds "He had justified this sudden elevation by the marvelous ease of speaking, which he had shown in various causes of brilliance."

He did not believe himself out of place among the combatants of July 14, and he broke with the court party at the beginning of the revolution. At the end of 1790, he was elected judge in Paris, then he became commissioner of the king at the tribunal de cassation. A member of Parliament for Paris in the Legislative Assembly, he hesitated at first between the royalists and the Jacobins. On the 6th of October, he protested against the revolutionary decree issued the day before on the ceremonial of the royal session. Interrupted as an aristocrat, he was silent and observed in silence until the end of 1791.

On the 29th of December, he delivered a speech on war, in which, in the manner of Brissot, but more briefly, he drew a picture of the state of Europe: according to him, each power was too poor to desire war. All the more reason to demand a lot, to summon the King of Prussia, to intimidate the counterrevolutionaries from within. Is he for war or for peace? Does he support Brissot or Robespierre? We don't know; but we can see in his somewhat equivocal words the Dantoniste policy: let's make war, but let’s be sure about making it, after having defeated the court.

This speech pleased and, although ambiguous, rang true. From then on, Herault followed a democratic line. On the 14th of January, in response to the declaration of Pilnitz, he proposed to the Assembly an address to the people, in which the perfidy of the court was clearly indicated. As for the threats of Europe, France only had to rise to confound them. "Certainly, the French, after having taken such a high rank, will not resolve to descend to the last place; yes, the last, for there is on earth something more vile than a slave people, it is a people who become so again after having known how to cease to be so."

On the 24th of January, he attacked the draft decree presented by the diplomatic committee in response to the Emperor's office: "I regret, he said, that the committee did not announce or rather reiterate the known resolution of France, which, as a consequence of her renunciation of any conquest, having also renounced to meddle in any way with the form of government of other powers, must doubtlessly, in the face of all mankind, expect the most perfect reciprocity; and when one will see a wise people regulating within its homes the form in which it suits it to live, leaving peace to its neighbors and seeking order for itself; if ambitions, vengeance, dare to arm themselves against the happiness of such a people, the world, posterity, history, by pitying them, will avenge them, and will mark with eternal opprobrium their vanquished enemies and even their conquerors, if there could be any.”

This elevated and diplomatic language made an impression and the Assembly voted the draft decree of Herault, by which the king was invited to declare to the emperor that he could henceforth treat with him only in the name of the French nation, to ask him if he wanted to remain the friend of the French nation and to give until the 15th of February to respond.

He was twice rapporteur for the legislation committee: on the 22nd of February, on ministerial responsibility, the conditions of which he discussed pleasantly; on the 7th of April on the acceleration of judgments in cassation.

At the beginning of July 1792, the gravity of the circumstances had led the Assembly to add an extraordinary commission to the diplomatic and military committees. The diplomatic qualities of his words led Herault, on the choice of his colleagues, to be designated for the drafting of the report relating to the declaration of the homeland in danger, a report which would be read with passionate attention by all of Europe (July 11). "Our most important business, he said, is to go to war soon, and not to wait for a chance or a set back which, however slight, might make some of the powers who are now mute observers, but whose diplomatic correspondence shows us, perhaps in the distance, secret hopes and a prudence subordinated to fortune, determine to be against us. Let us therefore produce a great movement, let us deploy a formidable apparatus, let us interest each citizen in his fate: let’s call, it is time, all over the fatherland, all the French, all those who, having sworn to defend the Constitution until death, have the happiness of finally being able to carry out their oath. The fatherland is in danger, and this single word, like the electric spark, hardly left within the national representation, will resound the same day in the 83 departments, will rumble on the heads of the despots and their slaves; and this single word will repel their attacks, or will victoriously support the negotiations, if, however, these are negotiations that we can hear and which in no way alter the immutable sanctity of our rights.”

In a more critical than enthusiastic spirit, Herault examines the objections that could be made to this declaration; he exposes them with a gift of objectivity very rare in this time of passion. He ends with a sufficiently warm oratory: "When, under Louis XIV, despotism, seconded by the genius of Turenne, held in check four armies at the same time, let us believe with confidence in the cause of the human race and in the miracles of freedom. Ah, gentlemen, a prophetic voice rises in my heart: we have sworn to be free; it is to have sworn to conquer! Called, in the face of the universe, to stipulate the rights of humanity, let us avenge these sacred and imperishable rights: I swear by these phalanxes which will gather from all parts of France, and by you, intrepid Gouvion, by you, brave Cazotte; and by all of you whom a death so beautiful and so desirable has reaped before the victory, under the walls of Philippeville; virtuous citizens, whose memory will henceforth preside over our destinies, and whose souls, quivering with joy in the depths of the tombs, will share in all our triumphs!”

In matters of revolutionary enthusiasm, that is all that the noble and pure rhetoric of Herault de Sechelles can give. He understands, he interprets with truth the spirit of 1792; he is not under its influence. His reason approves of patriotic folly; his heart does not share it. There is in this beautiful spirit an inability to be moved, to vibrate with the same passions as the people. He admires Danton and would like, I believe, to possess his sympathetic verve; but, whatever he does, he mingles with the passions of the time only as a dilettante, with the reserve of a delicate observer, with a good will that is immediately cooled by a innate decency. His friend Paganel said that he distinguished himself from the men of his party by "his liberal education, his gentle affections, the tastes and the urbanity which reveal the beautiful forms of his body and the noble and brilliant features of his face". (1)

(1) Paganel, II, 247. Cf. Souvenirs du pere du Berryer, I, 176 “Herault de Sechelles was not forty years old in Year II. He was one of the most handsome men in France, tall, dark-faced, very noble; he had the manners of the court."

Indolent, selfish, he pleased everyone, even the fiercest sans-culottes, who forgave him his status as a ci-devant because of his modesty, his affability, and the pleasant turn he gave to the most revolutionary measures. Paganel, believing to praise him, judges him severely "He spared, he says, all opinions, and appropriately took, but only for his defense, the colors of each party." No, Herault was not a hypocrite (1), but an epicurean who tasted the flower of each opinion in turn, an eclectic to whom it seemed that all sides were right, but that there was more common sense and good faith in that of Danton. He loved life; but he did nothing ugly to avoid the guillotine. His laziness explains what is undulating in his politics, and Paganel was truer and shrewder when he wrote "laziness dominated over all his tastes, and the love of women over all his other passions. His speeches to the tribune, his work on the committees, were many victories he won over himself, were so many thefts from his pleasures. Herault lavished a life which promised him only brief pleasures. He was always ready to lose it. He felt that the genius of the Revolution would prevail over his precautions and his prudence; and each event warned him of his destiny. He spared himself the terrors of it, by filling with much existence the few days which were counted to him..."

(1) This reputation came to him from the contrast which was noticed between his political gravity and his private playfulness. Saint-Just would say hatefully in his report: "Herault was serious in the Convention, a buffoon elsewhere, and laughed incessantly to excuse himself for not saying anything". And Sieyes wrote in his intimate notes: "Brilliant with his success, H. de S., in his distraction, looked like a very happy funny fellow, who smiled at the irascibility of his thoughts" (Sainte-Beave, Causories du Lundi, t. V).”

Mais c’est la Herault tel que le fit la crise meme de la Terreur.* In 1792, he is still smiling and optimistic. It does not seem that the fall of the throne moved him. On the 17th of August, he traced with a rather bold hand the first draft of the revolutionary tribunal. His educated voice mingled with the great voice of Danton in the work of national excitement which marked, in August 1792, the dictatorship of the Cordeliers and Girondin patriots. His proclamation on the capture of Longwy (August 26) is not lacking in emphasis, any more than the noble letter he wrote on September 10, in his capacity as president, to the widow of the heroic Beaurepaire.

*This sentence has eluded my ability to translate.

In the first six months of the Convention where he represented the department of Seine-et-Oise, his speeches were rare. Elected president on the 2nd of November, he was sent with Simon, Gregoire and Jagot, to Mont Blanc. He was still there during the trial of the king, whom he condemned, it is said, by letter, but without saying to what penalty. The Convention liked to be presided over by this man of noble face and conciliatory manners. They put him at their head on two important occasions. It was he who presided temporarily, in place of Isnard, on the night of May 27 to 28, when the commission of the Twelve was broken up for the first time. On the 2nd of June, he replaced the tired Mallarme in the chair, and had the sad honor of guiding the Convention in the walk it took in the Tuileries Gardens and the Carousel, to make people believe that it was free and to save its dignity. It was therefore to the beautiful Herault that Hanriot made his crude reply "The people did not rise to listen to phrases, but to give orders."

He was made a deputy to the Committee of Public Safety on the 30th of May "to present constitutional basics". On the 10th of June he tabled the famous draft Constitution, improvised with so much haste. Circumstances alone made the short and dull report he read on this subject famous. There is only one original idea: the establishment of a national grand jury, to which each department would appoint a member, and whose function would be “to protect the citizens from the oppression of the Legislative Body and the Executive Council.” This article was rejected on the 16th of June at the request of Herault himself, who declared that he had always considered the institution of the a national jury to be very dangerous. This is the first time that a reporter has admitted to having an opinion other than expressed in their report. And yet, on the 24th of June, he proposed in his name an additional article: of the censorship of the people against its deputies and of its guarantee against the oppression of the legislative body. This system contained the single Chamber, counterbalanced it as a second Chamber, and tended to the same end as the "national jury". This bicameriste insistence of Herault served as a theme for the Robespierrist Jacobins to slander him. "We remember, Saint-Just would say in his report, that Herault was with disgust the mute witness of the work of those who drew up the plan of the Constitution, of which he skillfully made himself the shameless reporter." (1)

(1) Yet Couthon praised Herault’s attitude on the committee to the tribunal (26 brumaire an II).

Yet nothing would alter the favor he enjoyed at the Convention. Re-elected to the Committee of Public Safety, on the 17th of July he made this chimerical and Jacobin proposal, inspired by the beautiful dreams of Jean-Jacques, at which his skepticism must have made him smile to himself, "Citizens, you decreed this morning that the house of the traitor Buzot, in Evreux, would be razed. The Committee of Public Safety thought that it was necessary to celebrate the return of freedom in this city by a civic festival, in which six young virtuous republicans will be married to six young republicans chosen by an assembly of old men. The dowry of these young girls will be provided by the nation". The Convention adopted the proposal.

As we can see, his talented pen didn't hesitate to align with the ideas of others. There was even one instance where he acted as a rapporteur to interpret the underlying opposition of the Robespierrists to Danton's inclinations. On August 1st, 1793, Danton had proposed the establishment of the Committee of Public Safety as a provisional government, seeing in this unity of dictatorship the most effective means to defend the nation and the revolution. Hérault had too much political acumen and was too much a friend of Danton to hesitate in opposing the anarchic and disorganizing spirit alongside him. Nevertheless, he allowed himself to be influenced and presented a report against his master's proposal, contributing to its rejection on August 2.

On the 9th of August, by a singular favor, the Convention called him once more to the chair. They wanted her noblest and finest speaker to appear and speak in their name at the national holiday, which was held the next day in honor of the acceptance of the Constitution by the people. It was a new federation. Mixed with an immense retinue in which there were delegates from all the primary assemblies of the Republic, the Convention went slowly to the Champ de Mars, according to the program created by David, and stopped at six solemn stations, in front of the fountain of regeneration, in front of the triumphal arch erected in honor of the women of October 6, at the Place de la Revolution, at the Invalides, at the altar of the fatherland, and finally in front of the monument for the warriors who died for the fatherland, at the Champ de Mars.

Herault thus delivered six speeches which shone more by the high decency of the expressions than by the internal feeling. He moved the people, however, when he addressed the dead soldiers: "Ah! how happy you were! You died for your country, for a land dear to nature, loved by heaven; for a generous nation, which vowed a dedication to all feelings, to all virtues; for a Republic where places and rewards are no longer reserved for favor, as in other states, but assigned by esteem and by trust, you have therefore fulfilled your function as men and French men; you entered the tomb after having fulfilled the most glorious and desirable destiny that there is on earth; we will not outrage you with tears.”

The spirit of this festival, as reflected in the speeches of Herault de Sechelles, was entirely philosophical and naturalistic: "Oh Nature! exclaimed the friend of Danton, receive the expression of the eternal attachment of the French for your laws, and that these fertiles waters that spring from your breasts , that this pure drink that watered the first humans consecrate in this cup of fraternity and equality, the oaths that France makes to you on this day, the most beautiful that the sun has lit since it was suspended in the vastness of space.”

The inspiration of the six speeches of the president of the Convention had no deist, spiritualist character: it is the indirect negation of the ideas of Rousseau, the glorification of the positivist tendencies of Diderot. One can imagine what sadness, sincere and respectable, Robespierre must have experienced at this demonstration which already foresaw the Feast of Reason. I admit that he, who was born to preach, was envious of the role of great philosophical pontiff that the Dantonist Herault played that day. But it was a deeper feeling, a believer's pain that kindled in him that hatred, of which the harmless and amiable haranguer was to be the victim.

II

From then on, [Herault] felt himself watched by the symbolic and frightening eye which figured on the banners of the Jacobins, and he saw that Robespierre was watching him. He immediately darkened the color of his presidential speeches, but without carmagnole. Soon he had himself sent on a mission to Alsace, and he wrote, from Plotzheim, on 7 Frimaire Year II, in Jacobin style: "I have taken all possible measures to raise the department of Haut-Rhin to the level of the Republic. The public spirit was entirely corrupted there. Intelligence with the enemy, aristocracy, fanaticism, contempt for assignats, speculation and non-execution of the laws everywhere: I fought all these scourges, I suspended the department, created a departmental commission; I forced the popular Society to regenerate itself; I broke up the surveillance committees, the least of which were feuillants, and I replaced them with sans-culottes; I organized here the movement of terror which alone could consolidate the Republic: I have created a central committee of revolutionary activity, which requires the rapid action of all the authorities; a revolutionary force detached from the army and which covers the whole department; a revolutionary tribunal, finally, which will bring the country to its senses. "

Thus declaimed this delicate,* for reason as much as for personal prudence: we know, moreover, that he was not rigorous to the aristocrats of Alsace and that he did not shed a drop of blood (1).

*Aulard uses delicate here as a noun and I’m genuinely not sure what to translate it as. Possibly he means fop, or dandy, possibly someone who is tricky or someone who is tactful, as in a “delicate situation”. However, these are only my suggestions and possibly inaccurate.

(1) Cf. Hist. De la Revol. Fr. Dans le departement du Haut-Rhin, par Veron-Reville, 1865, in-8.

But, since the feast of August 10, Robespierre had been weaving a skillful plot against him and was trying to undermine the Dantonist party through him. His plan, indicated in his intimate notes (2), was to make Herault pass for a spy for foreign powers in the Committee of Public Safety.

(2) Le proces des dantonistes, par le docteur Robinet, pass.

The care which this serious spirit took to learn about all foreign affairs, his continual handling of diplomatic papers, might give some pretext to the accusation of communicating to the enemy the plans of the revolutionary government.

As it happened, like everyone else, he had had relations with Proly, bastard of the Prince of Kaunitz. On 26 Brumaire, Bourdon (de l'Oise) echoed these rumors, and dared to say to the Convention: "I denounce to you the ci-devant attorney general, the ci-devant noble Herault Sechelles, member of the Committee of Public Safety, and now commissioner in the Army of the Rhine, for his liaisons with Pereyra, Dubuisson and Proly." But the mine burst too soon: there was a general protest, and Couthon himself had the honesty to pay homage to the patriotism of Herault.

However, an incident had occurred in Alsace, which gave pretext to enormous calumnies. In Brumaire, a letter was intercepted at the outposts of General Michaud's army, who sent it to Saint-Just and Lebas, in Strasbourg. Signed: the Marquis de Saint-Hilaire, this letter tended to lead people to believe in intelligence between the people of Strasbourg and the enemy. The trick was crude. But how to make Saint-Just listen to reason? He immediately imprisoned part of the authorities of Strasbourg, and left in his post only the mayor Monet, and a deputy. A second letter arrived immediately, same signature, dated Colmar, 7 Frimaire Year II. The mayor was reproached for not having yet delivered the city, despite the money received: and the "marquis de Saint-Hilaire" added: "I have only been here (in Colmar) to talk to our friend Herault, who promised me everything."

On the spot, the representative Lemane, who had replaced Saint-Just and Lebas in Strasbourg, had the mayor arrested and, insultingly, sent the letter to Herault. [Herault] brought together the authorites and the popular Society of Colmar and, in a long speech, warns them against the machinations of the royalists, adding that he asks for his recall. It was, among the patriots of Alsace, a cry of pain, for Herault had made himself loved during his mission. But he was exasperated by Lemane's suspicion (1).

(1) Veron.Reville, pass.

Back at the Convention, he was all the more anxious to justify himself because his colleagues on the Committee displayed an insulting distrust of him. Young Robespierre claimed to have brought back from Toulon a document which proved the betrayal of his college: "Ah! how could I be vile enough, cried Herault, to abandon myself to criminal liaisons, I've only had one intimate friend since the age of six. Here he is! (pointing to Lepelletier's painting) Michel Lepelletier (2) O you, from whom I will never part, whose virtue is my model; you who were, like me, the butt of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr, I envy your glory. I would rush like you, for my country, to meet the daggers of freedom; but were it necessary that I were assassinated by the dagger of a Republican? - Here is my profession of faith. If having been thrown by the chance of birth into this caste that Lepelletier and I have not ceased to fight and despise is a crime which I must atone for: if I must, I still have the freedom to make new sacrifices; if a single member of this assembly sees me with suspicion at the Committee of Public Safety: if my prorogation, a source of continually recurring hassles, can harm the public thing before which I must disappear, then I pray the National Convention to accept my resignation from this Committee."

Not one of the accusers answered a word; the Convention not only passed on the agenda on the resignation of Herault, it ordered the printing of his speech (9 Nivose).

(2) assassinated Lepelletier, like Marat, had only admirers. In reality, Herault could not bear his vanity, and mocked him. This president, after 89, refused one day to sit at the same table as a simple prosecutor. We find the comic account of this incident as it took place at Herault’s house, in Oeuvres completes de Bellart, VI, 128.

This triumph did not stop the calumny. On 11 Nivose, Robespierre wrote in his own hand and had Collot, Billaud, Carnot and Barère sign this letter to Herault, "Citizen colleague, you had been denounced to the National Convention, which sent this denunciation back to us. We need to know if you persist in the resignation which you have, it is said, offered yesterday to the National Convention. We ask you to choose between perseverance in your resignation and a report of the Committee on the denunciation of which you have been the object: because we have here an indispensable duty to fulfill. We await your written repudiation today or tomorrow at the latest." These hypocritical threats did not intimidate Herault: he did not resign, and the Committee made no report.

The documents of young Robespierre, we have them: they are in the Archives. These are Spanish papers seized by one of the cruises on an enemy ship: the name of Herault is not even stated there. It is to be believed that the famous threatening letter had no other purpose than to force Herault to reveal himself, in the event that, as was hoped, he would be guilty of high treason. We can guess Robespierre's rage, his confusion, in the presence of this disappointment. His audacity knew no bounds: on 26 Ventose, Herault was arrested with Simond for complicity with the enemies of the Republic and relations with a citizen charged with emigration. The next day, on a summary report from Saint-Just, the Convention ratified this arrest, but did not decree it until 11 Germinal with the Dantonists.

In the meantime, the innocence of the defendant had come to light: the emigre whom he had been accused of hiding in his home was none other than his own secretary, Catus, appointed by the Committee of Public Safety and who, if he had crossed the border, had only been able to do so for a diplomatic mission. They were careful not to confront Herault with this. Moreover, Saint-Just's report of 11 Germinal did not make the slightest allusion to this grievance, which had been the official cause of the Dantonist's [Herault’s] arrest. It was not even brought up at the revolutionary tribunal. (1)

(1) Cf Robinet, 349-352.

In order to ruin Herault, it was necessary to resuscitate the old grievance formerly disavowed by Couthon, and to accuse him of complicity with the foreigner. Saint-Just dared to say: "Herault, who had placed himself at the head of diplomatic affairs, did everything possible to avert the projects of the government. Through him, the most secret deliberations of the Foreign Affairs Committee were communicated to the foreign governments. He had Dubuisson make several trips to Switzerland, to conspire there under the very seal of the Republic.”

It was not easy for the men of the revolutionary tribunal to color the condemnation of Herault who had exclaimed proudly, in the style of Danton: "I challenge you to present the slightest clue, the slightest adminicle possible, to make me only suspect of these communications." (2)

(2) Asked about his name and where he lives: "My name is Marie-Jean, a name not very prominent even among the saints. I sat in this room where I was hated by parliamentarians." Accused of complicity with Chabot and others, he confined himself to denying that he had knowledge of the affair. The court did not insist. But it must be recognized that Herault's notorious intimate relationship with the Abbe d'Espagnac made an unfavorable impression.

They then read to him the famous papers seized on a Spanish ship, two letters from Las Casas and Clemente de Campos, Ambassador of Spain, in which Herault was mentioned by name as an agent of the foreign country. The unfortunate replied: "The tenor of these letters, the perfidious style in which they are written, sufficiently indicates that they were fabricated abroad only to make patriots into suspect and to ruin them. And certainly, the trap is too grossly overstretched to let myself get caught up in it!" Now, and this is not the least infamy of the Robespierreists, the prosecution had not hesitated, in order to ruin Herault, to insert his name in the two Spanish letters, to fabricate all the passage where his accomplices were supposed to reveal his name. We have said it: these papers are in the Archives, M. Robinet published them, and there is no question of Herault’s involvement.

Asked about his mission in Alsace and about his negotiations in Switzerland, he replied, according to Topino-Lebrun, that he had worked, with Barthelemy, for the neutrality of Switzerland, and protected France from an army of 60,000 men. . -And Dubuisson's mission? It was Minister Defeorgues who gave it to him. -And Proly? - "I never communicated to Proly anything in politics, there was none (sic). Moreover, I had to confront myself with Proly. I was deceived, like Jay Sainte-Foix, like the Convention, like Jean-Bon, who wanted to take him on as a secretary, like Collot d'Herbois." And he added: "Like Marat, Proly was carried in triumph. The Convention, by a solemn decree, received my explanations."

Then came the insignificant accusation of having corresponded with a refractory priest. To which Herault replied that this priest, being a simple canon, could not be submitted to the oath and therefore could not be refractory. Finally, in a sort of peroration, he recalled what he had done and suffered for the Revolution. "It is here," he said, "the moment to invoke my services, to remind my judges of this Constitution which has cost me so much sweat, this Constitution accepted by all good French citizens as making them happy: It is by this Constitution that I saved the fatherland, and I can tell the French what a Roman general said: At this time, in which I have saved you, let us go to the Capitol to give thanks to the gods. These were not the only services I rendered to the fatherland: I was seen on the memorable day of July 14, 1789." Here, either foolishly or by malice, the Bulletin defers these six lines that conclude Herault’s defence to the next issue: "On July 14, 1789, I had two men killed beside me: I have not ceased to be pursued by the royalists, and especially in my mission in Sardinia. I was appointed judge, to the great regret of all the counter-revolutionaries who shuddered with rage; and when I accepted this post, it was necessary to have had courage to fill it."

All accounts agree that Herault was imperturbable in the midst of these dreadful debates. Condemned, he said coldly: "I expected that!" And later, approaching Camille, who was choked up and foamed with rage: "My friend, let's show that we know how to die." On the cart, according to Desessarts, "he was placed alone on the last seat; he carried his head high, but without any affectation; the most beautiful color shone on his face. Nothing announced the slightest agitation in his soul: his eyes were gentle and modest, he cast them around him without seeking to fix attention or to inspire interest. One would have said, seeing him, that cheerful ideas were occupying his imagination."

III

Such was the political career of Herault, much inferior to the personal merit of this distinguished man, one of the finest natures that appeared at the end of the eighteenth century. His philosophical opinions were those of Diderot, for who, a little denigrating, he wrote an unreserved eulogy (1).

(1) Voyage a Montbar, etc., au IX, in-8, p. 107-108.

They were also those that Buffon expressed to him in 1785: "I have always named the creator, said the great writer to him in an intimate outpouring; but you only have to remove this word, and naturally replace it with the power of nature, to give rise to two great laws: attraction and impulse (2).”

(2) Ibid., pg. 36.

The same philosophical freedom appeared in Herault's conversation. Shortly after 89, the lawyer Bellart, invited to the house in Epone, was scandalized by the remarks which he heard there. "The master of the house rested from the impieties with the obscenities. Finally, in two or three days, I discovered that he was materialistic to the highest degree." Bellart took it into his head to convert him and delivered to him a tirade as orthodox as Sganarella's remonstrance to Don Juan: "Don't be afraid," replied the other; although materialistic I will still take care of you, if necessary (3)."

(3) Oeuvres de Bellart, tom. VI, p. 125-129.

In frimaire Year II, Vilate attended a conversation between Herault and Barere on the supreme goal of the Revolution. Herault placed himself above all from a philosophical point of view. He already saw "the reveries of paganism and the follies of the Church replaced by reason and truth." "Nature, he said, will be the god of the French, as the universe is its temple." He therefore expressed his intimate feelings when, on the feast of August 10, surrounded by all his colleagues, he addressed an official prayer to Nature. On his mission at Colmar, he had made a proclamation "to replace, he said, false religions by the study of nature", and issued a decree which made the decadi obligatory, and instituted a festival of Reason in each canton capital (4).

(4) Sciout, Hist. De la Constitution civile, III, 741.

To the Robespierrist animosity aroused by such opinions, it would have been necessary to oppose pure and rigid mores. But this delicate* (perhaps entirely disgusted) lived in an elegant orgy. He was the titular lover of the beautiful and famous Sainte-Amaranthe. He knew the art of living together in peace, around him, several young women whom his beauty had fascinated. He made them wear his colors, yellow and purple, and the ultra-Jacobin Vinent denounced in his journal the impudence of this debauched young patriot. He himself confesses all this in gallant letters published by La Morency, the authenticity of which is indisputable.

*Same issue with the use of the word delicate.

Even if her style did not reveal the truth of Herault in every line, what interest would Morency have had, in 1799, in forging the documents with which she decorated her autobiographical novel of Illyrine? (1)

(1) Illyrine ou l’ecueil de l’inexperience, an VII, 3 vol., in-8.

Certainly, neither the mores nor the style of this cheerful woman are recommendable. It was she who wrote, with her French and her heart: "We are only happy by doing: it's my morality." But there is an air of truth in the confidences which is further accentuated by the author's thoughtlessness. Yes, the mistress of the conventionnel Quinette was too silly to imagine the details, so probable, so vivid, of her affair with Herault, she who could only support Illyrine's reputation by gross plagiarism (2).

(2) When she saw the handsome Dantonist, she thought she saw, she said naively, the god of love, the graces of Apollo. Invited to dinner with Quinette, in the luxurious apartment of Hérault, she admired the large library, the elegant living room, the outfit of the young conventionnel "his redingote de levite of bazin anglais, lined with blue taffeta."*

*Redingote de levite is a type of jacket/coat, while bazin anglais is a type of fabric.

The story of the visit she made to him at the Convention on the day when he was named president (November 2, 1792) is a piquant tableau of the mores of the time. She handed him, shortly afterwards, a petition in favor of divorce, which Herault read to the Convention and, he said, caused applause. But, a few days later (November 29, 1792), the gallant president was sent to the mission. "It is from the Committee of Public Safety, with the horses at the carriages, that I am writing to you, dear and beautiful; I am leaving at this moment for Mont-Blanc with a secret and important mission...". And, after having spoken to her of his mistresses and of the perfidy of Sainte-Amaranthe, he ended thus: "Adieu, Suzanne. Go sometimes to the Assembly in memory of me. Adieu. The horses rage, and one believes me nationally occupied, while I am only in love with my very dear Suzanne."

When Herault returned, everything was his, and he bought a lottery office for his mistress, for which the security of 30,000 francs was lent, she affirms, by the Abbe d'Espagnac. It hurts to see Danton's friend take pleasure in such base intimacy which bordered on cynicism. La Morency has innocuously traced the picture, quite Pompeian, of the erotic distractions of his orgy comrades. No less naively, she explains this shamelessness: "It is rather to kill himself, she says, that he takes pleasure to excess, than to be happy." Herault said to her, probably in the first weeks of 1794 "Sinister omens threaten me, I want to hasten to live; and when they tear me from life, they will think they are killing a man of thirty-two: well! I will have eighty years, because I want to live for ten years in one day!".

It must be admitted: this epicureanism, so indecent in such circumstances, gave color and force to the Robespierrist accusations and compromised Danton's party. But should we see in Herault, as in such a friend of Hebert, a wallowing brute? "Elegant writer, says Paganel, he devoted to letters all the time he stole from the tastes that dominated in him." I have not been able to read Eloge de Suger, which he published at the age of twenty-nine; but his Voyage a Montbar (1785) is an exquisite piece in every respect, in which Buffon lives whole again, man and author. In there, Herault does not show himself, as Sainte-Beuve said, "a light, unfaithful and mocking spy" (1), but an observer and a painter. By the fine truth of his insights, he is ahead of Stendhal, whose dryness and precision he has. A laborious writer, he constantly pursues brevity and simplicity, and he achieves the strength of Chamfort, with more breadth of intelligence and a concern for general insights that he perhaps owes to his association with Buffon (2).

(1) Causeries de Lundi, IV, 354.

(2) In 1788, he published (or rather had printed) le Codicile politique et pratique d’un jeune habitant d’Epone. Revised in prison, this work was not widely distributed to the public until 1801 under the title Theorie de l'ambition. These moral reflections, influenced by a philosophy that is a little too positive and dry, offer a pessimism that is tempered by a good-toned irony. M. Claretie has already pointed out the most remarkable of these maxims as well as a chapter on conversation, where Herault characterizes the most ingenious conversationalists of the end of the eighteenth century and the ideal orator as the one who would summarize the different kinds of spirit of Thomas, de Delille, de Garat, de Cerutti, d'Alembert, de Buffon, de Gerbier and a few others, lawyers or actors. This is the school where he trained and learned to please.

This very modern spirit, turned towards the future, à la Diderot, does not drag scholarly chains after him; he does not have the superstition of Latin, the adoration of Greco-Latin legend. But he knows how to enjoy the past, and tastes true erudition, for example in the Abbe Auger, the translator of Demosthene, for who he pronounced an elegant funeral oration, at the Societe des Neuf-Souers, in 1792. At a time when the University no longer taught Greek, and perhaps for that very reason, Herault says true things about Demosthene, whom he judges as a politician as much as an artist. "The Revolution, he says, by developing our political ideas, made us appreciate the works of some ancients and enjoy all their genius, a measure which we lacked."

He admires in the Greek orator "this proud and sensitive soul, which carries within it all the dignity and all the pains of the fatherland: this general movement, without which there is no popular eloquence, where the accessory relations, tightly packed, roll on high in periods which compensate for the extent of the ideas by the precision of the style.” But here, it is of himself that he thinks and it is his own talent that he designates when he says: "Never, above all, he never ceased to equal, by his efforts, this beauty, this continuous perfection of language, that happy mechanism, so familiar to the orator that he could not even cease to be elegant in the most impetuous apostrophes, in the most vehement outbursts: a rarer merit than one might think, because it is due to a particular kind of spirit, and mainly to the address which is the gift of multiplying the force by distributing it. Here we recognize Buffon's ideas on oratorical style.

He himself had made up, for his own use, a kind of rhetoric which was found in his papers and which the Magasin encyclopedique published in 1795. These are practical precepts, recipes distributed without order, but which bear the mark of experience and whose interest is all the greater since Herault is the only orator of the Revolution to whom we owe a technique of his art. There is a question that first fascinated those who inaugurated the political forum in France: Should we read the speeches or say them? Both methods had supporters: some used them alternately depending on the circumstances. As for improvisation, even those who abandoned themselves to it seemed to excuse themselves for it as if it were negligence: so Herault, who by the way hardly improvised, only poses the alternative, read or say? - “It is only by speaking, he remarks, and not by reading, that one can make what one says truly perceptible, this is the custom of the lawyers of the Parliament of Bordeaux; otherwise, one flounders; the ideas relax, weaken and soon die out. This is what happens to M. de Saint-Fargeau: hence the easy word of most lawyers who are so fond of talking about business. To reconcile the need for a full and concise style with the other, I think you have to learn by heart. It is true that it is costly, but glory is at the end, and that is the way to surpass both those who speak and those who write."

Memory is therefore the first part of public speaking. But how should one learn a speech?

"I meditate on it, says Herault, the main idea, the accessory ideas, their number, their order, their connection, the plan of each part, the divisions, the subdivisions of each object. I dare to affirm that it is then impossible to make a mistake. If one forgot the speech, one would be in a condition to repeat it on the spot; and how much moreover the rhythmic sentences, a little ornamented, a little brilliant, in a word all that strikes the self-esteem of the one who must speak, are they not engraved in the memory with extreme ease!”

"A very useful and very convenient procedure, to which you must get used to, to make up your mind quickly and to remember a multitude of ideas at the same time, is, when you have these ideas, to retain from each only the word that carries, and whose mere memory reproduces the entire phrase. Voltaire said somewhere: "The best words are the couriers of thoughts". Applying this adage here in another sense, I would say that you have to get your brain used to needing only head words [mot tetes] throughout the whole range of longer discussion."

"To learn by heart, this word pleases me. There is, in fact, only the heart which retains well and which retains quickly. The slightest thing which strikes you in place makes you retain it. Therefore, the art would be to hit each other as much as possible."*

*The French here reads: L’art serait donc de se frapper le plus qu’il serait possible. I genuinely have no idea if he means that we should be hitting each other with the force of our words … or actually physically hitting each other. Either could be possible with this man.

"To write. The memory remembers better what it has seen in writing. Make it like a painting where one reads in the way that one speaks."

"Memory is also aided by figures: thus count the number of things you have to learn, in a speech, for example."

"I have also experienced that it was very useful for me to speak to remember a speech; I often tried to speak in public for an hour, and sometimes two, without any kind of preparation. I came out of this exercise with a singular aptitude, and it seemed to me in those moments that if I had had to give a speech, which I would have only read, I would have come out of it with a great advantage.”

After memory, action seemed to him the most important part of eloquence. When he first started out as a lawyer, he had taken lessons from Mademoiselle Clairon. "Do you have a voice?" she asked me, the first time I saw her. A little surprised at the question, and moreover, not really knowing what to say, I answered: "I have one like everyone else mademoiselle. - Well! you must make one for yourself." Here are some of the precepts of the actress, which Herault tried to follow: "There is an eloquence in sounds: study above all to give roundness to your voice; so that there is roundness in the sounds, you have to feel them reflecting against the palate. Above all, go slowly, simple, simple!" She said to him: "What do you want to be? An orator? You must be one everywhere, in your room, in the street." She also gave this advice, purely scenic and bad for a speaker: "To dye the words with the feeling that they give birth to."

Herault says that he constantly thought of Mlle Clairon's voice, and he characterizes his own manner by recalling that of his teacher: "She takes her voice from the middle sometimes softly, sometimes forcefully, and always in such a way as to direct it as she pleases. Above all, she often moderates it, which gives it the slightest brilliance that makes it shine. She goes very slowly, which contributes at the same time to furnishing the mind with ideas, grace, purity and nobility of style. I maintain that there is, in speech, as in music, a sort of measure of tones which helps the mind, at least mine. I have felt that going quickly offends and prevents the exercise of my ideas..." "... Do not believe that this is a real slowness. One disguises it, sometimes by force, sometimes by warmth that we give to certain words, to certain phrases. The result is a pleasing variety, but the bottom line is always serious and posed."

Such was his concern to speak well that for a long time he compelled himself to declaim in the morning the fury of Orestes and the whole role of Mahomet, to the point of scratching his voice: in the evening he felt a strong diction, easy and varied. He neglected no means of training.

He carefully studied the gesture itself. Clairon said to him: "Your type is nobility and dignity in the supreme degree. Very few gestures, but place them appropriately, and observe the oppositions which bring out the changes in gestures." He himself said: "The multiplied gesture is small, is meager. The broad and simple gesture is that of true feeling. It is on this gesture that you will be able to convey a great movement." These notes contain even more practical remarks on action: "It is important to be firm on the feet which are like the base of the body, and from which all the assurance of the gesture proceeds. One cannot practice too much in one's room to walk firm and well under oneself, legs on feet, thighs on legs, body on thighs, back straight, shoulders low, neck straight, head well placed. I noticed that in general, gestures become easier when the body is tilted. When it is straight, if the arms are long, there is a risk of lack of grace. The mid-length gesture is infinitely noble and full of grace. Don't wiggle your wrists, even in the biggest movements. Before expressing a feeling, make the gesture (1)."

(1) The most technical remarks follow: "The soul of the arm is in the elbow ... It is in the elbow that the movement necessarily begins. - When you want to raise your arm, raise your elbows: let it be in general level with the hand. - Also open your arms. These open gestures open beside the body are better than those made in front of you. - By raising your elbow you round your arm. - Also lower your head to make it easier to raise the arms. The gesture is in the combination of the head and the arm. Raise the arm all at once, that is to say, the arm and the hand together. Make the gesture often before speaking: that there often remains an end which can still rise when you have spoken. Open and spread fingers announce astonishment, admiration, surprise; add to it also the elevation of the chest which expands to receive the idea that strikes it.”

Finally, here is a piece of advice which reveals the secret of the disdainful grace with which he appears on the platform: "You must always seem to create what you say. You must command in words. The idea that one speaks to those inferior in power, in credit and above all in spirit, gives freedom, assurance, even grace. I once saw d'Alembert in a conversation at his house, or rather in a hovel, for his room deserved no other name. He was surrounded by cordons bleus,* ministers, ambassadors, etc. What contempt he had for all these people! I was struck by the feeling that the superiority of the spirit produced in the soul."

*Cordon bleus are blue ribbons, i.e. members of an order of knighthood known as L’Ordre des Chevaliers du Saint-Esprit.

This rhetoric of Herault, so ingenious, explains the pleasure of his eloquence; it also explains its weakness. This orator, so preoccupied with training himself, with raising his head, with rising to the height of the subject, does not have in him the sources of oratorical inspiration, always ready and from which a Danton, a Vergniaud, and even lesser haranguers, rise up. I don't believe that he lacks conviction, nor that we should believe in the words that Bellart attributes to him: "When we asked him what party he was from, he answered that he was from the one who doesn't give a fuck about the others." No, there was sincerity in him about his philosophical and political preferences. But he did not have that revolutionary faith which transfigured even the most miserable in times of crisis.

In his Traite sur l’ambition, he distinguishes between male brains and female brains; I believe that he should be placed, whatever has been said of it, in the second of these two categories.

#qui posts#frev#herault de sechelles#i have many thoughts on this man#and i am subjecting you all to them#soon#also please feel free to reach out with feedback!#saint-just#danton#camille desmoulins#robespierre

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Bird/Rebirth” symbolism from TWDDD 1x2 Alouette

To get it out of the way, we’re talking about episode 1x2 here, or 102 if you want to format it that way. I’m mentioning it because...

...as we've talked about for years, the hands on the clock behind Beth as she wakes up (rebirth/resurrection symbolism) points to the TEN and the TWO. Or in other words, the 10 and the 2, as in 102. Or as in “episode 1x2”. Neither the audience nor the characters knew anything about Beth’s whereabouts at that point, she might as well have been dead.

But of course she wasn’t. Because where Beth, in 5x8 Slabtown, was protected by the Bird symbolism from her encounter with the Blue Heron painting from 4x12 Still...

...Lily wasn't. TWDDD 1X2 was the episode where she died.

...or that's how you could put it for simplicity’s sake. It's not entirely correct though, the reality is a bit more complex.

As we saw, Isabelle sang an old lullaby, “Alouette”, to calm Lily down before giving birth. “Alouette” is French for lark, and “Lark" is a bird.

In other words, the Bird symbolism actually WAS present in Laurent's birth scene, it just didn't apply to Lily. Instead, it protected her child.

(Let's also not forget that Lark was Madison's (from FTWD) Padre name, and Madison "resurrected" after being thought to have perished in the fire (Sirius symbolism) at the Diamond Stadium)

And in the words of Pere Jean: "It's a miracle".

A live baby, born from a dead woman. That's what I'd call major "resurrection/rebirth” symbolism.

Let's talk about how this is how we know the rebirth/ resurrection symbolism is also intertwined with the Sirius symbolism. As I constantly keep talking about, Sirius symbolism means return/resurrection/rebirth because it originates from the astronomical event that occurs when Sirius the Dog Star returns to the night sky after having disappeared for some time. And "Sirius" symbolism in the TWDU is often represented by the prescence of "fire" in some way, shape or form, because Sirius the Dog Star got its name from Greek "Seiros", which means "glowing", "scorching".

And how do we know baby Laurent is covered by Sirius symbolism?

"Welcome, Laurent"...

Here are few fun facts about Saint Laurent (Lawrence in English), who we now know baby Laurent is named after:

Here he is, looking fierce in the face of fire: