#royal institute of british architecture

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

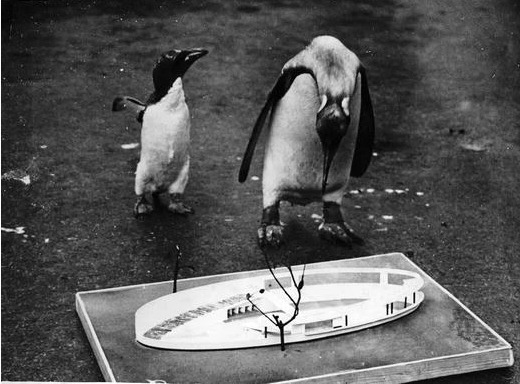

Two penguins “inspect” an architectural maquette of the new Penguin Pond, London Zoo.

Photograph by John Havinden, 1934 (RIBA)

#penguins#birds#avians#london#zoological society of london#1930s#1934#ZSL#animal photography#RIBA#royal institute of british architecture#do you think they liked it?

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

What, then, are we doing to our capital city now? What have we done to it since the bombing during the war? What are we shortly to do to one of its most famous areas - Trafalgar Square? Instead of designing an extension to the elegant facade of the National Gallery which complements it and continues the concept of columns and domes, it looks as if we may be presented with a kind of municipal fire station, complete with the sort of tower that contains the siren. I would understand better this type of high-tech approach if you demolished the whole of Trafalgar Square and started again with a single architect responsible for the entire layout, but what is proposed is like a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.

HRH The Prince of Wales, A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the 150th anniversary of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), Royal Gala Evening at Hampton Court Palace, 30 May 1984

#quote#architecture#RIBA#Royal Institute of British Architects#National Gallery#Trafalgar Square#Prince of Wales#Prince Charles#King Charles

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

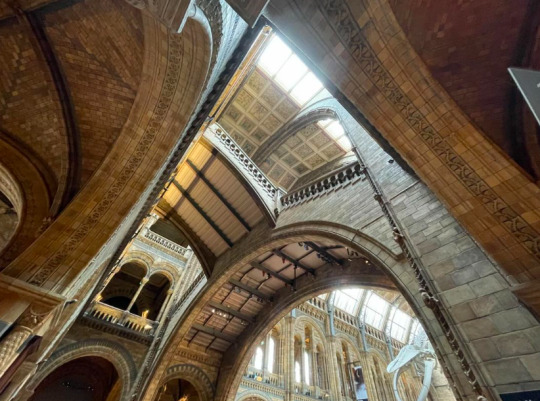

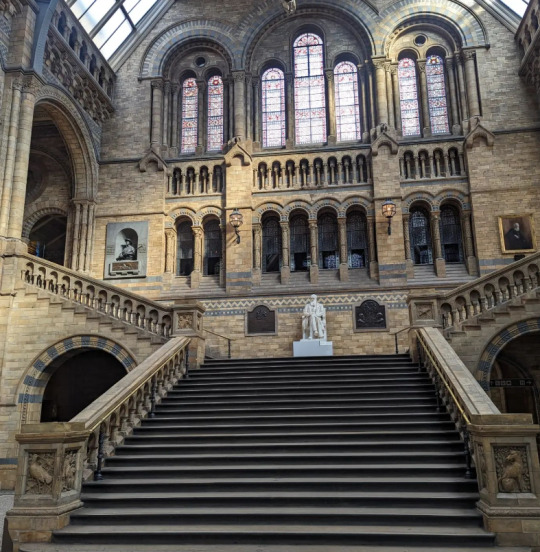

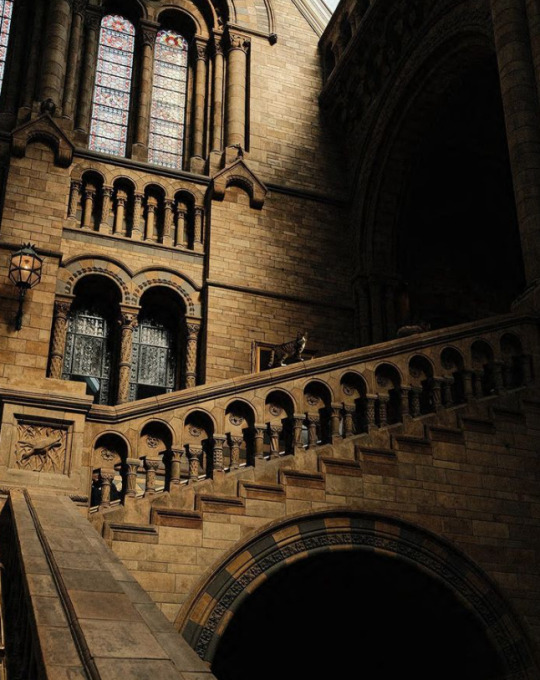

Natural History Museum - London

The Museum first opened its doors on 18 April 1881, but its origins stretch back to 1753 and the career of Sir Hans Sloane, a doctor and collector. Sloane travelled the world as a high society physician. He collected natural history specimens and cultural artefacts along the way. After his death in 1753, Parliament bought his extensive collection of more than 71,000 items, and then built the British Museum so these items could be displayed to the public. In 1856 Sir Richard Owen - the natural scientist who came up with the name for dinosaurs - left his role as curator of the Hunterian Museum and took charge of the British Museum’s natural history collection. Unhappy with the lack of space for its ever-growing collection of natural history specimens, Owen convinced the British Museum's board of trustees that a separate building was needed to house these national treasures. He drew-up a rough architectural plan in 1859 entitled 'Idea of a Museum of Natural History'. The plan was later referred to by architect Alfred Waterhouse in the design of the Natural History Museum. In 1864 Francis Fowke, the architect who designed the Royal Albert Hall and parts of the Victoria and Albert Museum, won a competition to design the Natural History Museum. However, when he unexpectedly died a year later, the relatively unknown Alfred Waterhouse - a Quaker architect from the north of England - took over and came up with a new plan for the Museum. Waterhouse used terracotta for the entire building as this material was more resistant to Victorian London's harsh climate. Construction began in 1873, and the result is one of Britain’s most striking examples of Romanesque architecture — considered a work of art in its own right and has become one of London's most iconic landmarks. Owen's foresight has allowed the Museum to display very large creatures such as whales, elephants and dinosaurs, including the beloved Diplodocus cast that was on display at the Museum for 100 years. He also demanded that the Museum be decorated with ornaments inspired by natural history. And he insisted that the specimens of extinct and living species kept apart at a time when Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution was revealing the links between them. Along with incorporating Owen’s ideas into his plans, Waterhouse also designed an incredible series of animal and plant ornaments, statues and relief carvings throughout the entire building – with extinct species in the east wing and living species in the west. Waterhouse sketched every one of these sculptures in great detail, even asking Museum professors to check the scientific accuracy of his drawings, before creating the fantastic decorations that complement the Museum’s exhibitions. While the building reflects Waterhouse’s characteristic architectural style, it is also a monument to Owen’s vision of what a museum should be. In the mid-nineteenth century, museums were expensive places visited only by the wealthy few, but Owen insisted the Natural History Museum should be free and be accessible to all. The Museum took nearly eight years to build, and moving the collections from the British Museum in Bloomsbury was a huge job. Relocating the zoological specimens, which included huge whale bones and taxidermy mammals, took 394 trips by horse and cart spread over 97 days. The Natural History Museum finally opened in 1881. The building’s decorative and Romanesque style by Waterhouse is reminiscent of medieval European abbeys, but it is also a monument to Owen’s vision of what a museum should be: the world’s largest and finest institution dedicated to natural history.

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/history-and-architecture.html

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/visit/virtual-museum.html

#other's artwork#architecture#Romanesque#Alfred Waterhouse#Sir Richard Owen#terra cotta#Natural History

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minnette de Silva is my Roman Empire and here is why.

It’s 1918, Sri Lanka is still known as Ceylon, a British Colony and the last place you’d expect to find feminist ground breaking artistic pioneers. Minnette de Silva is born and concurs.

One of the first modernist architects to come from Sri Lanka AND the first Asian woman to become an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

She was awarded the SLIA Gold Medal for her contribution to architecture “regional modernism for the tropics”

She did not complete her formal education due to family circumstances. Despite not finishing the modern equivalent of her A-Levels, she undertook an apprenticeship and attended lectures at the Ceylon Technical College (Desi kids rejoice at an intellectual icon who had an untraditional path through education). She then joined the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art which allowed her to study under many influential architects.

She was eclectic, intelligent and a force to be reckoned. She was expelled from the Government School of Architecture in India for attending a Free Gandhi March and refusing to write an apology letter to the Head of the School for it (we don’t stan Gandhi but we do stan standing up for your beliefs!)

Her father was extremely opposed to her career path but she went for it anyway. A bad bitch. An unstoppable force.

According to The Guardian “During her time at the Architectural Association (AA) in the UK she cut an elegant figure, draped in silk saris and followed by a train of young male students bearing her bags and instruments.”

This is how I imagine her walking down those halls!

Minnette de Silva returned to a newly independent Sri Lanka in 1949, and established her career in Kandy. She was influenced by Ananda Coomaraswamy, and advocated for the preservation of the traditional methods of craftsmanship, construction, and acquiring materials. She was inspired to create a style that incorporated the newly Western methods of development with the natural style, aesthetic, and landscapes of the tropical island.

The photos below are her designs and they are

e x q u i s i t e ✨

She never married. According to Architectual Record Minette explained to a friend “husbands are only good for carrying one’s bags”

My real life reaction to reading THAT quote🔥

However, Minette was always plagued by financial insecurity, she died penniless in a hospital in Kandy on the 24th of November 1998 at the age of 80. She had fallen from her bathtub at home, and was not found for days. Only a relative few of her building remain standing.

RIP Minette de Silva, you were a pioneer and an inspiration.

#sri lanka#dark academia#sri lankan culture#desi culture#light academia#museums#sri lankan history#history#architecture#inspirations#poc dark academia#sri lankan dark academia#poc academia#women history#i’m back bitches

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

On October 24th 1796 the artist, David Roberts, was born in Edinburgh.

The son of a shoemaker, who began his career as an apprentice house painter. Roberts was born in Stockbridge, near Edinburgh, and while a boy he was a frequent visitor to Rosslyn Chapel, it’s architecture is a complex fusion of influences from many cultures, and it has been mentioned that it was an immense inspiration to the painter.

At the age of 19, after studying art formally at night, Roberts became foreman of work at Scone Palace for a time. Returning home in search of a new job at the end of the project, he took work as a scenery painter for James Bannister’s circus. Bannister offered him more work, engaging him on a good salary of 25 shillings a week, and for a while Roberts toured the country with the circus.

Through Bannister, Roberts then found work at the Pantheon Theatre in Edinburgh, but when the venture failed, he returned to his trade of house painter and decorator. All the time he was working on the “day job”, he was also practising his sketching and painting, thus developing his fine art skills.

Roberts returned to painting scenery for theatres in Edinburgh and Glasgow, meeting his wife, the actress Margaret McLachlan, at the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh. They had one child, Christine. In the early 1820s he exhibited work at the Fine Arts Institution in Edinburgh, including scenes of the abbeys of Melrose and Dryburgh, which were popular themes due to the immense interest in the history of the Anglo-Scottish border created by the work of Walter Scott.

Roberts was offered work in London, at first by the Coburg Theatre and then the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane. Soon Roberts was commissioned to work for Covent Garden, while also successfully exhibiting at the British Institution. Gothic, romantic and religious themes were still popular in art and Roberts continued to produce paintings of Scottish abbeys and famous European Cathedrals. He developed his range into landscapes and seascapes, as well as Biblical and antiquarian themes, achieving fame though his painting “Departure of the Israelites from Egypt”.

Roberts began to travel in 1832, producing a series of lithographs from his trip to Spain and Morocco. In 1838, he embarked on a tour of Egypt, Nubia, Sinai, Syria and the Holy Land, and his sketches, paintings and lithographs were hugely in demand on his return. Publication of “Sketches in the Holy Land and Syria, 1842–1849” and “Egypt & Nubia” followed, volumes that ran to many editions and are still popular as reprints today.

When he returned to Scotland, the Royal Scottish Academy feted him at a public dinner. As a result of this, Roberts advised the Academy that he was worried about work that was being done at Rosslyn Chapel. One of the major architectural conflicts of the time was between the “romantic school” who viewed overgrown buildings as beautiful in their own right, even seeing the moss and overgrowth as protective, and those who wished to restore and preserve buildings.

When he returned to Scotland, the Royal Scottish Academy feted him at a public dinner. As a result of this, Roberts advised the Academy that he was worried about work that was being done at Rosslyn Chapel. One of the major architectural conflicts of the time was between the “romantic school” who viewed overgrown buildings as beautiful in their own right, even seeing the moss and overgrowth as protective, and those who wished to restore and preserve buildings.

Roberts also visited Italy in the early 1850s, producing a volume of paintings entitled “Italy, Classical, Historical and Picturesque”. The last 15 years of his life were spent carrying out prestigious projects such as the painting of the opening of the Great Exhibition of 1851. He became a member of the Royal Academy and was given the freedom of Edinburgh. His distinctive style and intuitive interpretation of light were emulated by many artists who came after him.

The last time I posted about David Roberts I featured his work in Palestine and Egypt, the pics this time around are his home grown work, the first being a self portrait, next is his apparent inspiration, the Entrance to the Crypt, Rosslyn Chapel, St. Mungo’s Cathedral, Glasgow and Dumbarton Rock.

If you want to see more of his work check out the Royal Academy's site here.https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art.../name/david-roberts-ra

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The figure Architectural Aspiration being sculpted by Bainbridge Copnall which is above the main entrance of Royal Institute of British Architects. 1934.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bristol United Press Building - Temple Way - Bristol UK

The Bristol United Press building was built for the publishing and printing of newspapers owned by the Bristol Evening Post Group, which included the Bristol Evening Post, The Western Daily Press, the New Shopper and the New Observer. It was also the headquarters of the Evening Post.

Colin Beales had the position of ‘deputy group architect’ and John Collins was the leader with the title, ‘group architect’. They were both part of the Group Architects DRG that was appointed to design this building in March 1966. Colin suggested the collective name, “Group Architects”. The construction began in December 1970 and was completed in September 1974.

The architects received Commendation from the Royal Institute of British Architects Architecture Award in 1975.

The last of the three images here shows the BUP Building now as it has been redeveloped as a major research hub to be known as No1 Temple Way

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

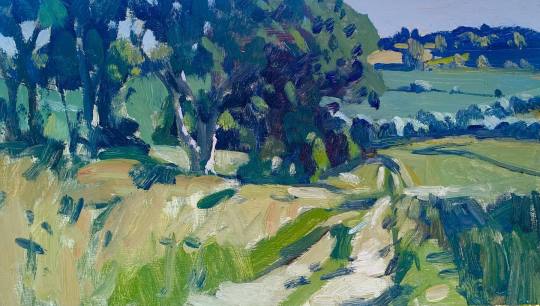

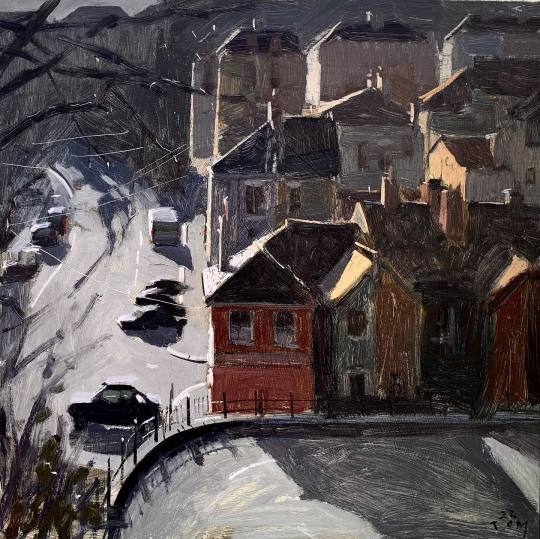

Tom Marsh is a Sussex based plein air oil painter.

His work is regularly hung at the Mall Galleries for the annual exhibitions of the Royal Society of Marine Artists, The Royal Institute of Oil Painters, The New English Art Club and The Royal Society of British Artists.

Tom works fast to capture the essence of a place but underlying his free style is a background in architectural illustration. Tom's degree is in illustration and he was admitted as a member of the Institute of Architectural Illustrators.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Life and Times of Queen Elizabeth II: An Era of Transition and the Future of the British Monarchy

Queen Elizabeth II, the longest-reigning British monarch in history, ascended to the throne on February 6, 1952, and her reign lasted until her death on September 8, 2022. Born Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor on April 21, 1926, her life and reign encapsulated a period of extraordinary change both within the United Kingdom and across the globe. Her tenure saw the transformation of the British Empire into the Commonwealth, the end of the Cold War, the dawn of the digital age, and significant shifts in social norms and values. As the figurehead of the UK and 15 other Commonwealth realms, her consistent presence provided a sense of continuity amidst these vast changes. Early Life and Ascension Elizabeth was not born as the direct heir apparent to the throne; her destiny changed with the abdication of her uncle, King Edward VIII, in 1936, which made her father the king and her the next in line. Educated privately at home and serving in the Auxiliary Territorial Service during World War II, Elizabeth's early life was a blend of royal duty and service to her country. Her marriage to Philip Mountbatten in 1947 was a union that lasted 73 years, until his death in 2021, and played a central role in her life and reign. Together, they had four children: Charles, Anne, Andrew, and Edward, whose lives and activities have also been closely followed by the public. Reign and Legacy Throughout her reign, Queen Elizabeth II navigated the monarchy through times of both turbulence and triumph. She worked with 15 UK Prime Ministers, from Winston Churchill to Liz Truss, and met with numerous world leaders, influencing diplomatic relations through her engagements. Her reign was marked by a dedication to public service, with countless engagements, state visits, and ceremonial duties performed with unwavering commitment. Elizabeth's ability to adapt the monarchy to the times without sacrificing its traditions was among her most notable achievements. She embraced television and the internet to connect with the public, including the annual Christmas broadcast, which became a significant aspect of her communication with the Commonwealth and the world. Death and Transition The death of Queen Elizabeth II marked the end of an era and the beginning of a new chapter for the British monarchy. Her son, Charles, succeeded her as King Charles III, bringing to the throne a different perspective shaped by years of advocacy on environmental, social, and architectural issues. The Future Monarchy King Charles III faces the challenge of leading a monarchy in a modern, more questioning world. With debates surrounding the monarchy's funding, its role in society, and the relevance of the Commonwealth in the 21st century, his reign is poised to be one of adaptation and potential transformation. Charles has indicated a desire to streamline the monarchy and focus on sustainability and social issues, which could redefine the royal family's role in British society and beyond. The transition also raises questions about the monarchy's place in the UK and its relevance to younger generations. While the monarchy has historically enjoyed strong support, changing demographics and societal values suggest that its future role may need to evolve. The life and times of Queen Elizabeth II represented a bridge between centuries, embodying tradition while facing forward. As the British monarchy enters a new era under King Charles III, it stands at a crossroads between its historical legacy and the demands of a changing world. How this institution adapts will likely define its relevance and survival in the years to come, continuing a story that has fascinated and engaged people around the globe for more than a millennium. Read the full article

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

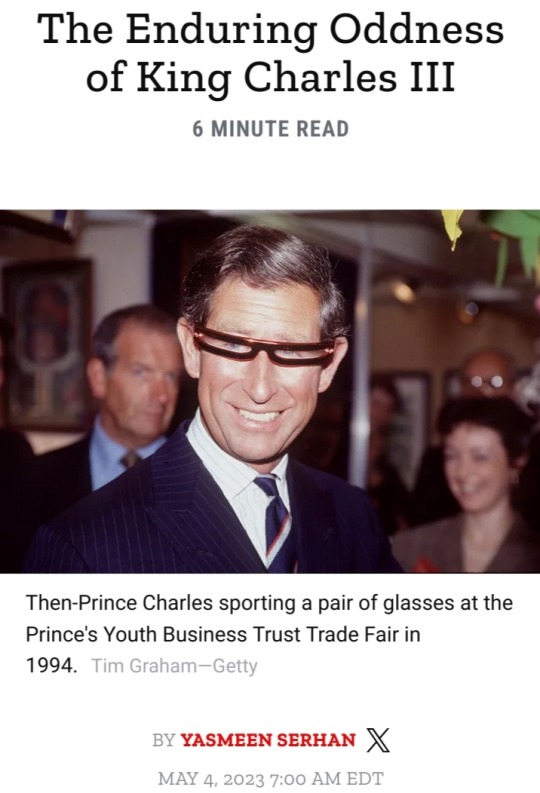

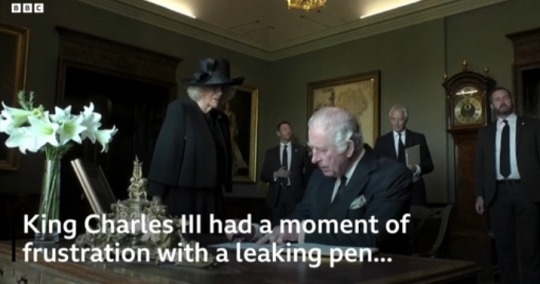

“The occupations of a constitutional monarch are grave, formal, important, but never exciting,” wrote the British journalist Walter Bagehot in his 19th-century work on the English constitution.

If that’s true, no one appears to have told King Charles III.

The British monarch, who will formally be crowned king in a coronation ceremony this weekend, is perhaps the least non-exciting royal alive.

Quite aside from his position as the head of the British royal family — a role that he automatically took over following the death of his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, in September — Charles’s life has always been under the spotlight, from his fairytale wedding to Princess Diana in 1981 to his falling out with his youngest son in 2021.

What distinguishes Charles from his mother, as well as most other members of his family, is his vast array of interests and hobbies.

Many Britons could probably name something about the king that most would find eccentric or odd: His love of red squirrels, for example, or his passion for British hedgerows.

There’s also his disdain for cube-shaped ice. Virtually everyone in the country, if not the world, knows how he feels about leaking pens.

“He’s quite quirky,” Sally Bedell Smith, author of Prince Charles: The Passions and Paradoxes of an Improbable Life, tells TIME.

Quite unlike Queen Elizabeth II, who had a reputation for keeping her personal views on everything beyond corgis and horses private, Charles has always been outspoken about his views and interests.

The one that he is perhaps best known for is his passion for environmentalism, a cause that he took up as early as 1970 when, as the Prince of Wales, he issued a prescient warning about the “horrifying effects of pollution.”

On related issues such as organic farming and sustainable fashion, Charles was ahead of his time.

So committed is he to the cause of conservation that he purportedly still wears a pair of shoes that he bought in 1971 and drives a classic Aston Martin that runs on bioethanol made from cheese and wine.

He has since issued more urgent calls for radical climate action.

But the monarch’s interests don’t end with the planet. Among Charles’ other noted pastimes is architecture and, in particular, how it has been stained in the modern era.

He once described a proposed addition to London’s National Gallery as “a monstrous carbuncle” and even likened London’s contemporary landscape to the Battle of Britain in World War II.

(“You have, ladies and gentlemen, to give this much to the Luftwaffe,” he once told attendees of an event marking the Royal Institute of British Architects’ 150th anniversary.

“When it knocked down our buildings, it didn’t replace them with anything more offensive than rubble. We did that.”)

A living embodiment of Charles’ architectural worldview can be found 130 miles southwest of London in Poundbury, a town featuring pastel-colored houses, abundant courtyards, and signless roads that was designed by Charles as an experimental planning project in the 1980s.

Due to be completed in 2025, Poundbury has been hailed as a model for new, livable urbanism. To critics, however, it’s seen as more of a feudal Disneyland.

That Charles has so many passions — to say nothing of his interest in philosophy, homeopathic medicine, and Islam — is, in many ways, a direct consequence of his extended stint as heir to the throne, a period in which he had both the time and the resources to pursue his interests.

His time as Prince of Wales “was not, by any stretch of the imagination, a life spent in waiting,” Bedell Smith says, noting his work with more than 400 charities, many of which were directly tied to his interests.

“He was very busy; he was a man in a hurry.”

“He has a fogeyish side, there’s no doubt about it,” says Richard Fitzwilliams, a longtime royal expert. “But he’s also an extremely hard worker.”

This perception can get lost amid Charles’ more peculiar idiosyncrasies, from his reported preference to travel with his own custom-made toilet seat to his apparent unwillingness to administer his own toothpaste.

It’s little wonder that one of his biographers, royals expert Christopher Anderson, dubbed him “one of the most eccentric sovereigns Great Britain has ever had.”

Since becoming sovereign, however, Charles had to scale his own personal views and interests back.

In his first address to the nation following his mother’s death, he conceded that, as he takes on his new role, “it will no longer be possible for me to give so much of my time and energies to the charities and issues for which I care so deeply.”

For many observers, this was an essential step in ensuring the continuity of the royal family as a unifying force in the country.

“A monarch simply cannot go out and make pronouncements on issues that could very well alienate some portion of the British population, and for that matter the population in those nations that remain realms over which the British monarch is a head of state,” Bedell Smith says.

“One of the most important roles of the monarch is to be the binding force in British society and to do anything that runs counter to that threatens his position.”

Charles has found some ways of maintaining his individuality, though.

While the monarch was reportedly blocked, for example, from attending the COP27 summit in Egypt last year, he did host a reception for others attending the summit to discuss the issue of climate change.

And while he may still be the “defender of the faith,” as the supreme governor of the Church of England, Charles has also dubbed himself the “defender of faiths,” reflecting his desire to be more inclusive.

And while Charles’s coronation will be steeped in religious symbolism and tradition dating back centuries, there will still be elements of the celebration that are unique to him, if you know what to look for.

The design of the ornately illustrated coronation invitations, for example, features a hedgerow border in an apparent nod to the monarch’s love of horticulture.

The ceremony will also feature Greek Orthodox music, in a tribute to the king’s father, the late Duke of Edinburgh, who was born in Corfu into the Greek and Danish royal families.

(“He was always interested in Eastern Orthodox thinking and practices,” says Bedell Smith)

The inclusion of religious leaders representing the Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, and Sikh traditions in the coronation underscores Charles’s efforts to reflect Britain’s diversity, as well as his own interests in non-Christian faiths.

#King Charles III#His Majesty The King#British Royal Family#Coronation 2023#coronation#ceremony#Walter Bagehot#Sally Bedell Smith#Queen Elizabeth II#environmentalism#organic farming#sustainable fashion#architecture#Poundbury#idiosyncrasies#Richard Fitzwilliams#Christopher Anderson#climate change#tradition#religious symbolism#horticulture#faith#diversity

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modernism

Another 1930s Odeon

The Modernism architectural style originated in Germany in the 1920s.

The “modern movement” as explained by RIBA was “used to describe the rigorous modernist designs of the 1930s to 1960s”. This was a period where architects “abandoned past styles”(RIBA) and focused on the functuality of structures and rationing the use of materials rather than the look – “rejecting ornament and embracing minimalism”(RIBA).

Modernism was inspired by the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century when art and design “embraced rationality and simplicity”(study.com) as a response to the Renaissance’s wealthiest who inhabitated homes of complexicity and luxury.

(archdaily)Definitions:

“Functionalism is based on the priniciple that the design of a building should reflect its purpose and function.

Minimalism emphasizes the use of simple design elements without ornamentation or decoration.”

During this era, characterized by inddustrialisation, there were many scientific advances (which led to a rapid change in society) as well as building technology advances. These building technology advances consisted of new construction methods, e.g. the steel frame and curtain walls, etc. The new methods were consistent with the modernism style as they were methods which kept material usage to a minimum as well as falling in line with the new desire for functional over aesthetic buildings. Lbuildings such as skyscrapers and mass housing (flats) were able to be built due to the advancement of knowledge and science, allowing the new methods to be structurally stable for such projects.

While previously the crafting of “furniture and décor”(study.com) was done indivdually and intricately, the new developments in technology meant that mass production was available and as said by study.com, “increaded affordability”.

(RIBA)Characteristics:

“Form follows function (function first)

Modern materials (e.g.steel)

Less is more (minimal)

Open plan interiors (spacious)”

During this time, society started to move away from being as materialistic and showing off money through excessively detailed and bright designs and towards function and minimalism. The departure of the extensive materialism allowed society to rebuild with a new order of equality between classes.

References:

“Another 1930s Odeon.” Art Deco Architecture, Sept. 2012, decoarchitecture.tumblr.com/post/31848938933/another-1930s-odeon-modernism-in-metroland.

Bowen, Kristy. “Modernism in Architecture: Definition & History | Study.com.” Study.com, 2019, study.com/academy/lesson/modernism-in-architecture-definition-history.html.

Kuiper, Kathleen. “Modernism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 17 Jan. 2019, www.britannica.com/art/Modernism-art.

“Modernism in Architecture.” Dezeen, www.dezeen.com/tag/modernism/.

Olcayto, Rory. ““Housing for Dirty People’ Is Back and I Welcome It.”” Dezeen, 29 Mar. 2023.

Royal Institute of British Architects. “Modernism.” Architecture.com, Riba, 2019, www.architecture.com/explore-architecture/modernism.

Walsh, Niall Patrick. “12 Important Modernist Styles Explained.” ArchDaily, 18 Mar. 2020, www.archdaily.com/931129/12-important-modernist-styles-explained.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zaha Hadid by Katherine Krizek

“I’m a feminist, because I see all women as smart, gifted and tough”

Zaha Hadid studied mathematics at The American University of Beirut until 1972 when she moved to London to study Architecture. As a woman and an Iraqi-British citizen of Muslim heritage she broke many barriers. In the 1988 exhibition “Deconstructivism in Architecture” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, her conceptual works gave the world an opportunity to witness her unique voice and helped to launch her as an international figure in the field.

Among her many firsts, she was the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2004, the London Design Museum’s Designer of the Year in 2014, and the Royal Institute of British Architects Gold Medal in 2016. She was also named a Dame to honor her achievements in architecture.

Born 1950, Iraq; Died 2016, USA

#zaha hadid#Katherine krizek#portrait#art#artwork#female portrait#female artists#architects#female architect#women in design#women of color#women of colour#women in art#irl women/girls

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A figura Architectural Aspiration sendo esculpida por Bainbridge Copnall que está acima da entrada principal, 1934.

Royal Institute of British Architects, 66 Portland Place, Londres

Coleções RIBA

The figure Architectural Aspiration being sculpted by Bainbridge Copnall which is above the main entrance, 1934.

Royal Institute of British Architects, 66 Portland Place, London

RIBA Collections

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

May 7th 1876 saw the death of the leading Scottish architect David Bryce.

Bryce was born in Edinburgh, where his father was a successful builder. He was educated at the Royal High School and joined the office of the architect William Burn in 1825, at the age of 22. By 1841, Bryce had risen to be Burn’s partner. Burn and Bryce formally dissolved their partnership in 1845, with disputes over the building of St Mary’s Church, Dalkeith, Midlothian, for the Duke of Buccleuch.

Burn moved to London, and Bryce succeeded to a very large and increasing practice, to which he devoted himself with the enthusiasm of an artistic temperament and untiring energy and perseverance. In the course of a busy and successful career, which was actively continued almost down to his death, he became the top architect in Scotland, and designed important works in most of the principal towns of the country.

In 1835 he was elected an associate of the Royal Scottish Academy, he was also a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, of the Architectural Institute of Scotland, of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and officiated for several years as grand architect to the Grand Lodge of Masons in Scotland.

Bryce died on this day 1876, after a short illness from bronchitis, leaving many important works in progress, which were completed under the superintendence of his nephew, who had been his partner for some years, and who succeeded to his business. He died unmarried.

He is buried in the New Calton Cemetery in Edinburgh just west of the main north-south path, beside his nephew, John Bryce, who I mentioned finished many of his uncles projects I posted pics of his grave a couple of years ago on a visit there.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things to Do in London: A Guide to Exploring the British Capital

London is known for its heritage and is, at the same time, brimming with everything modern. Something for everyone is really what London holds. Whether history, culture, or just experiencing something different-a long list has been created which includes things that can be done and seen in the city of London. Here's your ultimate guide to things to do in London to ensure you make the most of your visit to this iconic city.

Go to the Tower of London One of London's most famous landmarks, the Tower of London, is definitely a must-see for those interested in British history. Its ancient walls have provided a royal palace, prison, and even treasury. Today, visitors can go through the Crown Jewels, the medieval White Tower, and learn about all the fascinating tales that make this site so unique. Don't miss the famous Beefeaters, who guide tours and share spooky stories from the Tower's past.

British Museum The British Museum is a must-visit for art enthusiasts and history buffs. It has collections that go back centuries and across civilizations-from ancient Egyptian artifacts to the Rosetta Stone-one of the world's greatest museums. The museum is free to enter, so everyone can go in, and the exhibits are breathtakingly beautiful, allowing people to travel through time and culture.

Enjoy the Scenic Views at the London Eye Experience panoramic views of the city with a visit to the London Eye, one of the world's tallest observation wheels. Located on the South Bank of the River Thames, this giant Ferris wheel provides breathtaking views of landmarks such as the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben, and St. Paul's Cathedral. A ride on the London Eye provides an unforgettable way to view the city from above, especially at sunset or nighttime when the city is lit up.

Tour Buckingham Palace A visit to Buckingham Palace is the quintessential part of any trip to London. It houses the British monarch, and its grand architectural details along with its stunning gardens are a must-see. The State Rooms can be seen on guided tours at specific times of the year, so one gets a glimpse of the grand interiors of the royal residence. Catch the Changing of the Guard ceremony outside the palace, an iconic British pageantry.

Stroll Through Hyde Park One of the largest and most popular parks in London, Hyde Park provides a quiet and serene refuge amidst the bustling sounds of the city. It could be for walking, having a picnic near Serpentine Lake, or riding a pedal boat; the peacefulness is ensured in Hyde Park. There are also other facilities in the park, including Princess Diana Memorial Fountain and Speaker's Corner, where any individual can stand up to deliver a speech.

South Bank Promenade The South Bank of the River Thames is a melting pot of culture and entertainment. It has all of London's greatest cultural institutions from Shakespeare's Globe Theatre to the Tate Modern. Take a riverside promenade along the walkways lined with the view of the London Eye, St. Paul's Cathedral, and the Millennium Bridge. The area is also full of cafes, restaurants, and bars, making it an ideal place to relax after a day of sightseeing.

Visit Covent Garden For something more colorful, take a walk through Covent Garden: this is a comprehensive district meant for shopping and dining, and it hosts many entertainment events. The Market in Covent Garden provides various shops selling trades from handicrafts to antiques; in addition, the area accommodates some of London's greatest street performers. For drama lovers, there are also one or two shows hosted within the West End.

Explore Victoria and Albert Museum The Victoria and Albert Museum is a true gem of arts, design, and fashion. Having more than 2.3 million items on its roster, this is considered one of the world's biggest museums focusing solely on decorative arts and design. Its showpiece includes excellent works of sculpture and pieces of fashion; plus, impressive temporary exhibitions feature state-of-the-art art from modern-day artists.

Visit the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben Among the most famous attractions in London are the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben. The Gothic architecture of the Parliament building is located along the Thames, which houses the House of Commons and House of Lords. Inside the building, visitors can take guided tours when the Parliament is not in session. One cannot miss a picture with Big Ben, the clock tower synonymous with the city.

Thames River Cruise There is no better way to view London than on a Thames River cruise. The river runs through the heart of the city, and you get to glide past some of the famous landmarks, including Tower Bridge, London Bridge, and the Shard. Many of these cruises offer commentary, so it's informative and scenic at the same time.

Shop at Oxford Street Oxford Street is the heart of London's busy commercial life, and it boasts hundreds of shops, from big department stores such as Selfridges to worldwide fashion brands. If you want something special, visit nearby Carnaby Street and Regent Street, which has more boutique shops and independent stores.

Enjoy Afternoon Tea A classic British tradition, afternoon tea is a must-do activity while in London. Enjoy a selection of finger sandwiches, scones with clotted cream, and an assortment of pastries, all served with a pot of tea. Many upscale hotels, such as The Ritz and Claridge’s, offer luxurious afternoon tea experiences in grand surroundings. It's the perfect way to relax and enjoy the finer things in life.

Conclusion From ancient landmarks such as the Tower of London to modern attractions such as the London Eye, London is full of things to do. This city offers a vibrant tapestry of experiences, ranging from world-class museums and historic sites to vibrant markets and scenic parks. Whether it's your first time visiting London or you have been there before, London never fails to surprise and delight with its endless opportunities for exploration.

0 notes

Text

By Lynsey Chutel

The New York Times

A prizewinning building, once celebrated as Britain’s “best,” will be reduced to rubble if the university that owns it has its way.

The Centenary Building, once the glass-and-concrete triumph of the University of Salford, outside the northern city of Manchester, was the inaugural winner of the Royal Institute of British Architects Stirling Prize in 1996. The prize recognizes the best new building in Britain.

Barely 29 years later, the building has become a white elephant. Its critics say it is too hot in the summer, too cold in the winter, and too noisy all year. Its “aging infrastructure means it no longer meets modern standards and requirements,” the University of Salford said in a brief statement, adding that it has “been vacant for a third of its built life.”

But the decision to level it has pitted preservationists against pragmatists. Architecture buffs are rushing to get the Centenary Building listed as a historic site, which could spare it from the wrecking ball.

The university, on the other hand — along with the Salford City Council and a real-estate developer called the English Cities Fund — wants to demolish the building to make way for a $3.2 billion new city district to be known as the Crescent. The school, with more than 26,000 students, and its partners see the project as a key to fostering economic growth in the area.

Opponents of the plan include the Twentieth Century Society, an organization aimed at preserving Britain’s design heritage. “This is a sophisticated piece of modern architecture, with clear opportunities for adaptive reuse,” the society said in a statement, urging the university to reconsider. “It acted as catalyst for previous regeneration in the area, and could do so again.”

When the Centenary Building was completed in 1995, it was a celebrated for its wide interior spaces with indirect sunlight. When commissioning the building, the university called for a structure that would be a “fusion of design and technology,” according to the architect’s brochure. The Stirling Prize jury described it as “a dynamic, modern and sophisticated exercise in steel, glass and concrete.”

At the time, the building’s architects, Hodder+Partners, experimented with natural ventilation as an early energy-saving technique, forgoing the need for air-conditioning, Stephen Hodder, the head architect, said in an interview. Now, the building’s fluctuating temperature is one of the main complaints against it.

But it’s a design flaw that could easily be fixed by retrofitting the Centenary Building with new, more sustainable fixtures, Mr. Hodder said. “It shouldn’t be retained simply because it won a certain prize,” he said, arguing instead that it should be retained out of a responsibility to reduce its carbon footprint with sustainable design.

The Stirling prize catapulted to fame his then-fledgling architecture firm of six people. Hodder+Partners went on to winanother prize, the Civic Trust Award, in 1998. Today, it employs 30 and enjoys the prestige of a major firm.

When Mr. Hodder received the commission, the building was a 1960s-era academic structure with an interminable corridor and barely any natural light. He envisioned that the new design would mimic a mall or medieval street, with classrooms and laboratories opening up onto an atrium.

His instructions were to build quickly and affordably. Midway through, the plans had to be adjusted from housing the department of electrical engineering to the faculty of art and design. As the glass, steel and concrete went up, the university’s leadership at the time decided the building’s unveiling would also mark the centenary of the school’s founding.

In the years since, however, the university has centralized its campus, and academics and students have abandoned the building. The university rented it out for several years but it has also stood vacant. Critics have characterized its rapid construction as rushed and shoddy

Efforts to turn the building into a school, with Mr. Hodder’s help, came to nothing, he said. He has also abandoned hopes that it could be used a community health center.

“I’m trying to detach myself from the importance of that building to this practice,” Mr. Hodder said, adding that he learned about its planned demolition from news reports.

While Mr. Hodder says he has not joined any campaigns to save the building, the Twentieth Century Society is trying to whip up momentum. Last month, the society caught wind of the plan to demolish the Centenary building, said Oli Marshall, the society’s director of campaigns. The society and its trustees are among those seeking a historic site designation.

The university and its development partners — the City Council and real estate development company — did not respond to questions about why the building could not be repurposed.

The Twentieth Century Society sees its bid to have the building granted protected status as a test case for prizewinning architecture. If buildings that have been lauded for their contribution to British architecture “only have a shelf-life of 30 years, what does that say about the current state of British architecture?” the group said in its statement.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/12/world/europe/centenary-building-salford-manchester.html

0 notes