#rena yehuda newman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ron Schreiber (1934 - 2004) - "THE HOUSE IS OLD"

I think of the line "we live here. we think of the other house" daily. Found it first in a zine about being a butch faggot by the artist Rena Yehuda Newman. There is not much online about Schreiber. According to the anthology "Gay & Lesbian Poetry In Our Time" (Edited by Carl Morse and Joan Larkin), he was born in Chicago and raised in Dayton, Ohio. He lived all over the world (in Japan with the US Army as well as in Amsterdam) and taught at the University of Massachusetts for 30 years (!) - the last info is from alicejamesbooks.org, where one can buy two of his poetry collections.

0 notes

Photo

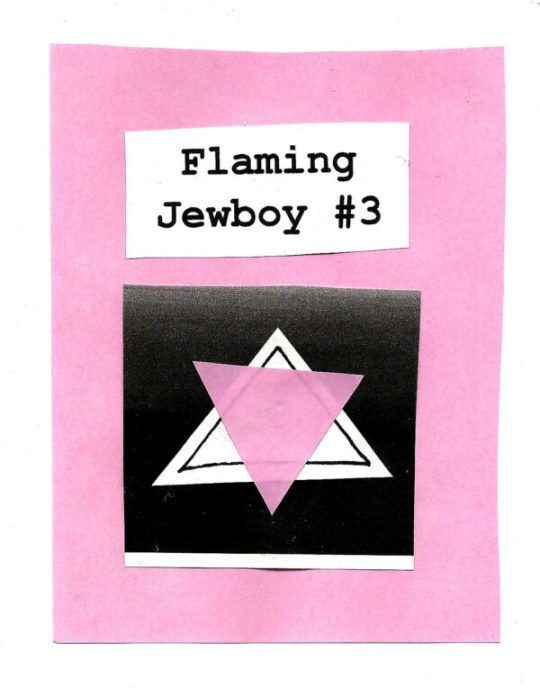

Issue #3 of ‘Flaming Jewboy’ by Rena Yehuda Newman is a zine about queer Jewish sexuality and "the honest confessions of a Jewfag..."

Read about it, or buy it here.

#zine#zines#fanzine#fanzines#flaming jewboy#rena yehuda newman#queer zine#queer zines#queer fanzine#queer fanzines#queerzine#queerzines#jewish zine#jewish fanzine#jewish zines#jewish fanzines#fanzine juif#zine juif#fanzine judio#zine judio

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pay Your Students: Student Activism and Student Labor In Campus Archives

Or, “Building Trust Between Archives and the Student Body: Hiring Student Historians” or even, “My Undergraduate Experience at the Midwestern Archives Conference: Why More Paid Positions Like Mine Must Exist On Campus”

by Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), Student Historian in Residence

“Student Memory: Then and Now” Poster by Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), presented at MAC 2019 in Detroit

This year, I had the honor of attending the Midwest Archives Conference (MAC) 2019 in Detroit, Michigan for a couple days sitting in on sessions, learning about the archival profession, and presenting my poster entitled “Student Memory: Then and Now”. I’d been to conferences before but the Midwest Organic and Sustainable Education Service (MOSES) Agricultural conference was, as you might guess, a little bit of a different vibe than an Archives meet-up.

The conference was informative and occasionally quirky (including the damaged document recovery vendor giving out vacuum-sealed beef jerky as a freebie). I attended sessions on imposter syndrome in the profession, documenting the HIV/AIDS crisis in the Midwest, and #Archives4BlackLives. In the time outside the conference, I wandered around Detroit with a friend, checking out a public installation in honor of organized labor, exploring the Detroit Institute of Art, and walking by the Church of Scientology up the street from our hotel. Critiques of many sessions included, the conference was an enriching and enlightening experience -- especially considering that, a little over a year ago, I had only a basic understanding of what an archives even was.

I may have been the only undergraduate at the conference, my age surprising many of the University Archivists who approached me to discuss my poster. While the poster discussed parts of my research and its relevance to the present, the bulk of my presentation centered around questions of archives outreach and community engagement, documenting the experiences of the student body and peer-educating about what an archives is and does. In my presentation, I wanted to suggest that archives can be supportive spaces for student activists on campus and archivists can be their accomplices in their pursuit of justice. I made a short list of action steps.

How can archivists support student activism?

Collaborate with student organizers, government, and groups to preserve student memory, especially for contemporary issues

Listen to the needs of students, especially marginalized students, asking: how archival collections can be of service to them?

Host events and workshops about relevant historical campus movements and protests

Encourage students to think of themselves as historical subjects by leading workshops teaching students how to document their experiences

Provide accessible opportunities for students to contribute their own meaningful, modern materials to the campus archives

But most importantly...

Fund paid student staff positions, employing students to do archival research, outreach, and modern documentation

On my poster I was transparent about the wages, conditions, responsibilities, and privileges of my position as Student Historian in Residence, which is well-paid, supported by the staff, and flexible in terms of time and content. By being compensated for my labor, I’ve been able to spend the time that I need to in the archives working on all sorts of projects that benefit the archives and (I hope) serve the student body.

Though the Student Historian position began this year as a pilot research opportunity, the work has sprouted into other projects, like creating a teaching kit about the Black Student Strike, spreading the gospel of archives by presenting to classrooms around campus, leading late-night archives sessions on topics like “Queer History”, teaching student government about self-documentation, and most recently, conducting interviews for a modern oral history project on UW-Madison student activism from 2016 - 2019.

While non-student staff keep the wonderful Archives ship afloat, this kind of outreach work can only be done by a student. I’m not saying that I’m the student who should do this work -- this isn’t about me, it’s about student labor in general. The importance and value of archival peer education is immense. The benefits of trust between the student body and their campus archives are best achieved when student staff members are given the opportunity to take ownership over the archives and bring that passion to the rest of their circles, letting other students know that their campus archives is a place where their collective work can be remembered. This quality of work can only happen if students are paid for it -- and paid well.

At the conference, I had one university archivist approach me and ask how their archives could create these student community connections without a budget. Was there a way she could get the same results without paying students for their work?

As the Student Historian, I have the profound opportunity to spend hours familiarizing myself with materials, reflecting on my learning, meeting with staff members, creating projects to serve my fellow students, and sharing my work with the rest of my community. This position requires a lot of time each week and has yielded projects that the Archives staff and I are proud of. Yet for many marginalized, low-income students -- all of whom would offer unique, necessary perspectives into these archival pursuits -- this opportunity would be inaccessible were it unpaid. Many students can’t afford to work for free. I answered that, while there are many steps an archives can take to support student activism and document these corners of student life, by not paying students for documentation or research, an archive creates a barrier for access and excludes the brightest, most marginalized students on campus from sharing their perspectives and benefiting from the enormous opportunity that archival work has to offer.

To University Archivists interested in the above: Apply for grants to fund student projects. Find funding for student staff members to do research, outreach, and modern materials collection.

Archives are a place for activism, for students to reclaim campus memory as their own. Do yourself and the student body a favor -- create more positions like mine and spread the archives love inside the reading room and beyond.

-- Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), Student Historian in Residence 2018-19

#Student#Student Archivist#Student Historian#Student History#History#Archives#Student Labor#Student Activism#Activism#Organizing#Memory#University#University of Wisconsin#UW#Workers#Wage#Labor#Labor History

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

These people are professionals

These people are professionals

Tuesday’s riot ‘not spontaneous’

From the publication Madison365, an ally of the BLM/Antifa/Insurrection, comes confirmation what most of us suspected.

By Rena Yehuda Newman – Jun 25, 2020 described as “is a recent History graduate of UW-Madison.”

On Tuesday night [06-24-2020] in Madison, marchers took to the streets to protest the arrest of local organizer Yeshua Musa, who was violently,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

Hi! Just wanted to say that your testosterone zine has been hugely helpful in my deciding whether or not T is something I want to pursue long term. Simple things like "most people stop taking T at some point after reaching a particular transition goal" are very helpful. Thank you for creating a nice resource that is helpful on my own gender exploration!

it's not my zine, it is Rena Yehuda Newman's, I just posted it on tumblr because I also thought it was very helpful and I wasn't seeing it on tumblr.

Their Instagram is @ rena.yehuda Twitter is @ renayehuda and Gumroad is renayehuda.gumroad.com

sorry for the confusion. i didn't want to add my own commentary to their information, just wanted to share it so more people saw it

0 notes

Photo

Issue #2 of ‘Flaming Jewboy’ by Rena Yehuda Newman. Read it online at QZAP (Queer Zine Archive Project).

#zine#zines#fanzine#fanzines#flaming jewboy#jewish zine#jewish fanzine#Rena Yehuda Newman#qzap#queer zine archive project#queer zine#queerzines#queerzine#queer zines#fanzine juif#fanzine judio#zine juif#zine judio

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Read Micah Bazant's 'Timtum: A Trans Jew Zine' online here. And read Rena Yehuda Newman's love letter to it here.

#zine#zines#fanzine#fanzines#Micah Bazant#Timtum#A Trans Jew Zine#Timtum: A Trans Jew Zine#trans zine#trans zines#queer zine#queer zines#trans fanzine#trans fanzines#fanzine trans#fanzines trans#jewish zine#jewish fanzine#zine judio#fanzine judio#jew zine#zine juif#fanzine juif

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Student Memory: What It Is & Why It Matters

Rena Yehuda Newman, Student Historian in Residence 2018 - 2019

Black Student Leaders Wahid Rashad, Harvey Clay, and others at Rally During UW Black Student Strike, February 1969

A song to listen to as you read: Archive, by Mal Blum

Student memory is a constant struggle. This is an axiom that every student organizer or worker knows intuitively. On college campuses, every four or five years means a complete turnover of knowledge. There is only a brief window for continuity. So, what does it mean to pass down memory in a place with such a transient population?

As a student historian, I’ve been researching the student activism of the 1960s Vietnam War era on UW-Madison’s campus. But there are significant gaps in the collections, namely, the voices of the student organizers who led the most major protest movements of their time, like the Black Student Strike. While it’s a relatively new phenomenon for archives to serve communities rather than powerful institutions, the same problem seems to be happening continually -- no one is documenting the campus activism of 2019.

Not only does this mean the erasure of student history, but also the continued forgetting of modern student memory, leaving each successive generation of students without context. This causes major problems for students engaged in social issues and policy change. Without memory of previous happenings and student-led initiatives, ideas and already-fought battles, students are at a severe disadvantage. Tireless hours by student activists can be undone. And if each year brings new amnesia, momentum is irrecoverably lost.

With this in mind, we have to ask: Who benefits from forgetting?

In my time as a student organizer, activism for or against new policies often feels like a race against the clock. I’ve heard time and time again that the administration and board of regents relishes a certain temporal safety. However awful a policy, however bad the student backlash, they can just wait it out until no student on campus remembers the time before. Those in power always benefit from public forgetting.

For example, in 2017 - 2018, University Housing unleashed a new mandatory meal plan without the input or consent of the student body, requiring all first years living in residential housing to pay an additional $1400 into WiscCard accounts, to be used exclusively for eating at the dining halls. This policy directly harmed low income students, students with eating disorders and dietary restrictions, and impacted students’ right to choose where and how they eat on campus. Major protests ensued all of last year, including an hour-long shutdown of UW’s most major dining hall. But many incoming freshman have no idea this policy is new, or that their fellow students spent countless hours fighting for an opt-out. Without a sense of memory, the student body is ill-equipped to advocate for itself and address harms they may experience but never be aware of.

Another example: in 2017, Governor Scott Walker tried to slash students’ ability to self-tax through allocable segregated fees, which would have effectively killed all of UW-Madison’s most major student organizations, many of which offer vital services for students like the Rape Crisis Center or the campus food pantry, The Open Seat. Students fought and won against this policy proposal, but the same issue could arise again. If students don’t know about this history of advocacy, the next time segregated fees are attacked, those future students will be forced to reinvent the wheel.

I want to bring together these two strands of maintaining student memory and recording student history. It seems that they are heavily dependent on each other -- if new students are given a sense of memory, “caught up to speed” with previous events on campus, all students benefit. I’m going to spend this spring collecting student materials to fill in the gaps. But I can’t do it alone, especially because as a white student, many of these are not my stories to tell.

We have so much to gain from remembering.

How should a student body organize against collective amensia?

Last week I presented to Associated Students of Madison (ASM), the UW-Madison student government about maintaining student memory. I believe student government can have an important role to play in creating workshops, sessions, and publications to educate students about their own past. Student government might also take it upon itself to do documentation work, creating folders full of posters and graphics and materials from recent organizing movements, especially on campuses where there isn’t a paid student historian to do this labor.

But this kind of documentation should happen at a grassroots level beyond student government. Student institutions and organizations have important roles to play, but are not representative. All students, especially students of marginalized identities, should keep records of themselves, write about their experiences, compile the materials of daily life and continuous struggle present in their time on campus. Creating “Disorientation Guides” to give to new students is useful. Though an individualist and professional culture usually means hoarding credit, fight back against this impulse by saying the names of fellow students and organizers who have also done the work. Create a folder on your computer of screenshots, receipts. Leave citations, make a record.

Collect for the future and fine ways to revive the past. Take opportunities in classes to research local historical student issues. Go dig around in your university’s archives. Ask for the wisdom of elders who have been around for a while. Tell the stories you learn, especially the stories that give you hope or create resilience in you -- make art about them, publish zines about them. Keep it alive.

Memory is protection against erasure. People and institutions of power will not record our stories, but we can. Create your files, archive your experiences. Make memory out of story then find a way to tell it. If you trust them, donate your materials to your local archive, especially university archvies. If you don’t, make your own. Either way, write it down. Collect it.

To all student activists engaged in the struggle: In fifty years, there may be a student wondering what their campus did during Trump Era America. Don’t let that story be written for you. Pick up your pen, fill up your boxes.

You are a historical subject, act like it.

- Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them)

#student#activism#organizing#archive#memory#remember#history#student history#student memory#documentation#my archives#archives#student government#campus

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

E.P.S. 900: A Student-Run Course

A couple weeks ago I was hunting around in the archives for the Wisconsin Student Association’s (WSA, precursor to ASM) Student Power Report. The usual and simple search methods weren’t working so well, so I sat down with one of my coworkers at the desk to look into the murkier depths of the internal archival databases.

We discovered a single box labeled “P. Altbach” with a few promising folders. What piqued my interest, though, wasn’t the “WSA” folders, but a few others labeled, “Student Protest Policy”, “UW-Government-Military Links”, and “E.P.S. 900″, among others. It looked good on screen, so we grabbed the elevator key and began the journey down to the archives basement.

Finding a box like this is a lot like finding hidden treasure. Following the coordinate map of shelf location, we pulled off an old box that had been accessioned in 1980. When we opened it, it seemed like the materials hadn’t been touched since. Excitedly, anxiously, I brought it upstairs and placed it at the table like a huge present. Since I’m Jewish, I can only imagine that this is exactly what Christmas morning feels like.

Curious about the ambiguity of the “E.P.S. 900″ folder, I set it down on the table and opened it up. Inside were documents on documents regarding a class entitled “Educational Policy Studies 900: Experiments in Teaching and Learning,” an entirely student-run class created by a student group called The Center for Radical Education.

The folder contains lists of projects, letters between administrators and the students behind the Center for Radical Education, correspondence between students, a letter from a Harvard professor interested in recreating the course, class descriptions, and reports on the course itself written by students.

The folder contains a report on the first time the class was offered, as well as a report on the second time in Spring 1969, the course having been moved from EPS 900 to 350 to allow undergraduates the chance to enroll.

According to these reports, the class exists because of the activism of students and collaboration with some of the more progressive members of the Educational Policy department’s faculty (including Associate Professor Philip Altbach, the compiler of the collection for whom the box is named). According to their own report, the idea for the class came about in the summer of 1968, within a small community of Education School graduate studentsr. In Fall 1968, sixty grad students took this class for credit.

The class was structured around student-generated projects with a huge range of topics. A list published after the initial Fall 1968 class named 20 projects, including “Theater, Education, and Politics”, “High School Social Studies Curriculum”, “History of the Blues”, “Film Project”, “Black Employment Problems in America”, “Rent Strike Project” (lead by now-Mayor of Madison Paul Soglin), and a reading group on “cybernetics and technology”. The cybernetics project is described in detail in the report as gathering once a week “in one of the students apartments about eight at night and lasting until eleven or so before breaking up (and until one before total disbanding).” Though the cybernetics discussion group was one of the more successful projects, it seems like the energy of the participants was far from unusual within the course.

The second time the course was offered in Spring 1969, concurrent with the Black Student Strike, according to a letter sent out by the Center for Radical Education, the course had to be capped at 500 students because if enrollment were to be kept open, they would “end up with 1000 or more students in the course” and they simply could “not handle that number of students under our present set up.” In short, the course was wildly popular, but clearly lacked the resources that its organizers and participants needed.

The project list expanded in the course’s second run in Spring 1969. There were projects listed as “Black Studies Curriculum”, “Madison Tenant Union”, “Women’s Liberation”, “Free High School”, “Contemporary Poetry”, “Contemporary Radical Student Movements”, “New Theater” & “Community Theater”, “The Nature of Self Discovery”, “The Consumer and the Community”, and more.

As of my finding this box in Fall 2018, I haven’t found much of any secondary sources expanding on this class (though doubtless there are more materials tucked away in the archives directly related to this course and its organizers). On some of the project lists, there are names of project organizers attached, many of whom are likely still alive and could be interviewed for oral histories. With 500 students attending, this was no small phenomenon. I wonder about its impacts for student organizers and how it functioned within a greater contemporary scene of activism and student radicalism.

Not only are the research prospects of this course exciting, but its implications for the University today are enormous. As a student in 2018, what does it mean to me to know that there were student-run courses at this school just fifty years ago? It was hard-fought for, and unfortunately died away. Why? Why couldn’t this happen again? Could it?

In a moment of intense political upheaval, for me, a course like this feels like lifeblood. Could the work of these former students be a precedent or map for creating newly radical courses? I don’t know how many students have the time and energy for an undertaking like this. But there’s something electric in knowing that it is possible, that is has been done. As I continue researching this particular nook in UW’s Vietnam War-era activism, I hope my understandings can act as a talisman rather than a relic.

- Rena Yehuda Newman, Student Historian in Residence

#StudentHistory

#UW-Madison#education#higher education#Student Power#Student#Pedagogy#Education Policy#EdPol#Black Power#Union#Strike#Black Student Strike#Vietnam#Activism#Organizing#Student action#History#Archives

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Student Strike Teaching Kit: Memory for Justice

by Student Historian in Residence Rena Yehuda Newman (They/them)

For the past three months, I’ve been working collaboratively with the UW Archives Staff to put together a Teaching Kit about the Black Student Strike of February 1969, in honor of the 50th Anniversary of the Strike, coming up in February 2019. As of the end of December, the first draft of the kit has been finished and sent out to community members for review. By the end of January, I’ll have a link up here for anyone to view the kit publicly.

I drafted the following post before winter break, and though it’s a bit late in its posting, I figure that as I enter the revision stage of the kit (having received tons of helpful, wonderful feedback from community collaborators), I want to post this bit of personal reflection.

______________________________________________________________

Mid December, 2018

I’m heading home for winter break this Sunday. But before I sign off for the break, I wanted to take a second to reflect on the experience of putting together this kit, especially as a white historian working on a public project to document black activism.

After Cat, Troy, Katie, and I had our first meeting to talk about compiling a teaching kit for the strike, I was enthusiastic about the project. These days, I think reparations through education can be an effective tool for restorative justice, revitalizing memories of upstanding community members fighting injustice. The staff was kind with entrusting me with a lot of say in the process, more or less putting me in charge of curating the primary source documents that the kit would feature.

Holding this responsibility means being transparent about my own limits: as a white student, there are limitations to my work on this project. The meanings and choices I make regarding the materials and curation of this kit will be influenced by my own identities and experiences. Whiteness impacts those choices. While it is necessary that white people also engage in anti-racist action in all spheres, at all times during this project I have wondered deeply about my ability to do justice for a project like documenting the Black Student Strike of 1969 for Students in 2018-2019.

Many of my weekly meetings with Cat Phan, my supervisor, were spent discussing this question of curation, bias, and identity. By nature, this collection will be limited (we tried to keep it to ~10 documents for accessibility’s sake). I’ve included an extra document, a placeholder entitled “Absent Materials”, highlighting omissions in curation and encouraging students to question inclusions and exclusions in the collection. We also included a set of “Modern Materials” regarding a set of demands by black students for 2016, also calling for anti-racist action on campus.

We wanted the kit to include a wide swath of voices, especially student voices. We wanted the kit to uphold the story of the black student organizers, despite the fact that our UW archival collections have enormous gaps with regards to firsthand student activist accounts. I wanted the kit to make clear the history of state violence that the UW enacted on its own students by calling in the National Guard. I wanted the kit to reaffirm the ongoing relevance of the Black People’s Alliance’s “13 Demands”, salient today. I wanted this kit to bear witness and I wanted this kit to help my peers bear witness.

But as a public, community project, the UW archives staff cannot be the only voices in constructing the kit. While my usual instinct is to bring in more student voice, especially connecting with my black peers about this project, Cat suggested that we send it out wider, including scholars from the Black Studies Department, Black Student Center, and Multicultural Student Center. Now that the first draft is done, we’re in process of sending it out to these community partners for critique. I want to be accountable for mistakes I’ve made in this process, transparent about my thinking. I want to be accountable for the work that’s being done/needs to be done. I want to document that process of accountability so that students doing similar projects in the future can learn from my mistakes and reflections.

I hope that this kit, after feedback, collaboration, and revision, can be a jumping-off point for restorative education. A small teaching kit cannot claim to tell the whole story of an event like the Black Student Strike, but it can provide an opportunity to glean old-new meanings, to give students and educators alike the chance to explore a less-commemorated event that bears enormous significance for the UW community. The process as well as the product brings lessons to questions of what it means to be a part of this strange American project, locally and nationally.

The Black Student Strike contains lessons for me as a young, white student seeking to work for justice on campus and in the world. I hope that the questions contained in this teaching kit can act restorative, opening up conversations about the Strike itself and what it means to inherit its memory.

#Student History#UW Archives#University of Wisconsin#Wiscsonsin#Wisco#Black Student Strike#Black History#Public Memory#History

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grappling with State Violence at UW

Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), Student Historian

As part of my research in the UW Archives, I’ve been reading through the Subject Files of the Black Student Strike, from Fall 1968 - Spring 1969. During the Black Student Strike, hundreds of students boycotted classes, marched, and disrupted business-as-usual in pursuit of 13 Demands drafted by the Black People’s Alliance. The 13 Demands included the admittance of 500 more black students, a Black Studies Department, and student control over the proposed department and the Black Cultural Center, along with several other proposals.

While the events of Black Student Strike took place over a period of months in the ‘68 - ‘69 school year, student actions came to a head around February 1969 -- and consequently, violent state actions followed.

“13 Demands”, Black Protest February 1969 Subject File, UW Archives

Most of the materials that speak to student perspective on the strikes, like protest pamphlets and literature, are in the Wisconsin Historical Society. The The UW Archives collections heavily include the administration’s perceptions of the strike, providing an intimate and harrowing look into the perspectives of the powerful during this era.

In the Black Student Strike archival subject folder there is a chronology of events narrated from an administrative perspective, likely created by the chancellor’s office from the voice and tone of the document, which frequently describes Chancellor Young’s personal schedule and other internal commentary, though the official source is not stated. The chronology details administrative interactions with black student leaders, starting in November 1968. The document narrates these events largely as inconveniences for then-Chancellor H. Edwin Young.

Using a chronology created by people in a position of power creates historical dilemmas, or at least a number of important opportunities for questioning. The chronology consistently lacks concern for student well-being, especially those of student protesters. The report often reads like a crime report against black student activists. While the record of events is helpful in providing a clear timeline of events, what is included and excluded (and what is known and unknown) by the administrative writer is informative of agenda. My selective recounting of the document is a further redaction. Do I trust the writer of this chronology? Do you trust me as a student writing about these events?

According to the document, in November and December, students engaged in talks with Young and began their protests and class boycotts. By February, the 13 Demands were brought to Chancellor Young’s office. On February 8th, “several blacks demonstrate[d] inside Field house during Ohio State-Wisconsin Basketball game, while police hold 300 demonstrators at bay outside.” The report includes that 4 policemen were injured. It does not include whether or not students were harmed.

On February 9th, the Student Senate of the Wisconsin Student Association “votes to support strike and to provide bail money.”

On February 10th, “1,500 students and sympathizers peacefully picket major classroom buildings while strike leaders emphasize at rallies that their aim is a non-violent confrontation with the University administration.”

On February 11th, “180 city policemen and county sheriff’s deputies and traffic officers -- all riot equipped -- clear demonstrators from Bascom Hall and four nearby classroom buildings.”

On February 12th, “Governor Knowles activates 900 Wisconsin National Guardsmen at the request of UW President Fred Harvey Harrington and Chancellor Edwin Young.”

On February 13th, “1,000 more guardsmen called up” in addition to to the 900 from the previous day. That day there were “ten arrests, several injuries.”

“Chronology of Activity Regarding Black Students” p.2, Black Protest February 1969 Subject File, UW Archives.

The Chancellor and President of the UW called in 1,900 armed National Guardsman against unarmed student protestors.

According to the newspapers, the UW Regents advocated heavily on behalf of this decision as well. One regent even called for budget cuts to the UW “unless University takes prompt action” ( “Legislators Label Protestors at UW ‘Long Haired Creeps’”, Wisconsin Rapids Tribune, February 12th 1969). A headline from the Madison Capitol Times intoned, “Troops to Remain at UW ‘As Long as Needed’: [Says Chancellor] Young”. Armed guardsmen "used clubs as they made their way through demonstrators” and left unrecorded numbers of students “injured in strife”, according to the Milwaukee Sentinel. (“Knowles Calls Out Guard to Restore Order at UW,” Milwaukee Sentinel. February 13th, 1969.)

I’ve read over this section of the chronology several times. Each time something inside me sinks. Right now, I can’t look at this piece of history with cool eyes. I am not removed from it, rather, I inherit it. As a student, how do I reckon with the knowledge that the leaders of my school called for state violence against their own students?

The response I have to anticipate from modern readers is common: “But that was 50 years ago. Things are different now.”

But they aren’t.

The UW Board of Regents just last year proposed and passed a piece of legislation ironically titled “The Free Speech Bill,” (SB 250) which could suspend or expel students for “disrupting” speakers invited to the UW, never mind the fact that what constitutes “disruption” remains ambiguously defined. Administrators in power within the UW system remain unfriendly to expressions of civil disobedience and free speech via protest, despite UW being a public school. Last year, I heard many professors and law students describe this policy as possibly unconstitutional, and dangerous due to its potential to create a “chilling effect” and reducing civic protests writ large. Outside of “The Free Speech Bill”, echoes of withdrawing funding from the UW because of the political actions of its students are loud and clear today. I wrote about my fears regarding the policy in a Letter to the Editor published the Daily Cardinal.

The Regents’ modern policy is not removed from the UW Administration’s past. To understand this modern connection to the armed troops employed by UW administrators during the Black Strike is to more intimately understand a legacy of state violence against student activism at UW.

As a student historian, I find it important to grapple with this legacy. If students brought these grievances up to the UW Regents and UW-Madison Chancellor’s office today, would they be remorseful or would they stand behind the violent decisions of their predecessors? Would they seek reparations? Most saliently, and perhaps most hauntingly, I need to ask: would they do it again?

For students in a particularly politically tumultuous time, when the impacts of local, state, and national policy directly harm members of student body, and the tensions between school and state seem to grow each year, the answer to that question is precarious and high stakes.

Would they do it again?

- Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), Student Archivist

#StudentHistory

#Student History#Student Historian#student#UW#UW-Madison#Wisconsin#Archives#UW-Archives#State Violence#Protest#Strike

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crafting a Research Proposal

Rena Yehuda Newman (They/them), UW Archives Student Historian

From Archives staff: A belated posting of a blog entry written two weeks ago by Student Historian in Residence Rena Yehuda Newman!

--------------------------------------------

As September comes to a close, the deadline for my research proposal draws nearer. The initial deadline we’d set of August was a bit too soon -- at that point, about a month into the job, I’d only just gotten my landlegs in the archives.

When I wasn’t in meetings with various staff members, I was picking through materials that had been pulled for me, suggested by the staff, browsing and trying to get a sense of what piqued my interest and felt meaningful. I poked at the bookshelves and boxes and tried my hand at searching through the digitized databases. Though I’d spent a bit of time in archives before this job, it took from the end of July until summer’s end for me to feel capable in the archives as an actual researcher (not just a student with a class prompt) -- to become familiar with the staff and knowledgeable of the resources available to me.

Now that we’re almost through the month, I’m starting to put the finishing touches on my research proposal. Though I’d started drafting it at the end of August, it’s only now coming to fruition. I’m glad I had the extra time -- I needed that time to explore, to ask new questions, and to put the new lessons I’m learning into practice. Starting the school year itself has really helped catalyze the project.

I’m currently taking a class from Bill Cronon entitled, “The Making of the American Landscape”. His father wrote one of the histories of UW I’ve been using as a guide. The purpose of the class is to understand how to read landscapes as historical texts -- or in the opposite order, understand how political, social, and economic forces render themselves in the physical world around us and shape the ground beneath (and above) our feet.

Yesterday, my section went on a tour of Library Mall. We discussed the bizarre, mismatched architectures of Memorial Library, Humanities, the Historical Society, the Red Gym, and more. My TA showed us photographs from earlier eras, using visuals as hints to discover when the picture was taken. But I found myself curious when the conversation turned to the Vietnam War era, awake with connections between the class and my research here at the archives.

There’s an old myth (or fact, I don’t know yet) about the Humanities building that circulates in Madison: its horrible-but-enchanting brutalist architecture exists for the purpose of eschewing student protest. In its most extreme forms, the myth describes the building’s slanted sides as potential tank positions, a solid bastion of war against “radicals”.

Though I don’t know about the intent behind Mosse’s brutalist architecture, I intend to find out. At the very least there is a grain of truth behind the rumor; the Humanities building decries public gathering by design. Enormous and echoey above the surface and cramped with hallways inside, there are no good places to get together with crowds in the entire concrete block. The architecture is alienating, uncomfortable. Congregating there is difficult and counterintuitive. I’ve heard the same speculations aimed at the design of Vilas, which has similar booming plazas and intentionally uncomfortable spaces.

The more I thought about the way in which architecture impacts public attitudes, the more I thought about how political action shapes public policy, whether through the will of the public or as a reaction against it. Though most of my research up until this point has been exclusively about students, I was still thinking about the chronology of the Black Strike written by the administration’s office. I can’t stop thinking about how violent the UW administration has historically been towards a politicized student body -- even a non politicized student body. Thus far I’ve been researching how student protest impacted campus, but during the tour, I began wondering how the administration’s often violent response to student protesting has impacted UW policy today. If the administration’s disdain for student radicals potentially shaped a behemoth like the Humanities building, what other less-visible structures did it erect around campus?

My research proposal has shifted from an inquiry into the relationships between students groups to an investigation of the University’s response to student organizing and how the UW admin’s responses have shaped the modern student political climate, protesting policies, and physical landscapes of the University today.

While my project will focus on the violent responses of UW towards its own students, the University’s history violence extends far beyond the scope of the student body, encompassing gentrification, racial violence, policy towards Madison homeless, and even (especially) the college’s very beginning when UW was established on stolen HoChunk land. When historical wrongs are documented as evidence, they can better be used for the purpose of reparations. I hope my research can illuminate the ways in which the University’s violent past haunts campus grounds -- and what students can do to join our predecessors in resisting it.

- Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), Student Historian

#StudentHistory

#history#black strike#student history#uw#uw-madison#wisconsin#UW Archives#state violence#resist#research#landscape architect#landscape#architecture#Mosse#violence

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Student Historian in Residence: Hello from the Archives!

My name is Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), the new Student Historian in Residence at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives. I’m here on this tumblr in the name of being a good self-historian. Here I’ll be documenting the research, ideas, epiphanies, philosophies, reflections, and poetry of the archives during my residency. Under the hashtag #UWStudentHistory, I’ll be sharing my musings on the regular, and you can follow me on this whimsical adventure through boxes of mystery materials and memories yet uncovered.

As a History student entering their Junior year at UW-Madison, I find myself thinking a lot about memory. As a young Jewish kid, I remember a someone once telling me the difference between history and memory. History is concerned with what happened, while memory asks a different question: Who am I because it happened?

In a day and age of revealed political turmoil and growing unsafety of marginalized communities in the United States, asking this question of memory has become front and center for me. Participating in civic discourse as a young white, Jewish, non-binary artist and writer means that I hold all of my identities in both hands. I also inherit the histories and memories of all these categories -- and regardless if I understand them or not, the stories of those who have come before me shape who I am today.

As a student at UW, I inherit the legacy of this institution. Long, problematic, strange, niche, agricultural, brilliant, radical, racist -- UW is all of these things, embroiled in contradiction. I write this blog post sitting underneath an 1892 portrait of a white University President reclining in a three-piece suit, sitting next to a copy of “The American Archivist” journal bookmarked to a paper about archivists and reparations activism. Behind me are boxes and boxes of mixed materials, many of them uncatalogued, many of them with secrets inside.

There are the public radio reels and the collections from the Dictionary of American Regional English, where linguists interviewed people all around the country just to hear how people spoke. There are time capsules in here, and reports about corn. There are the images of the prestigious Ku Klux Klan UW chapter from the early 1900s in our yearbooks. There are fliers from protests and rallies and statements that the Chancellor released to mollify roiling student bodies, students who shouted in the streets, who wanted to protect Japanese students from internment, who demanded an African American Studies Department, who protested weapons contractors and chemical companies, who bombed Sterling Hall. What I’m saying is, it’s not simple. But as a student, all of it is mine.

Just as all of it is mine, I want my peers to know that all of it is ours. All of these students from eras past have been us, even the ones who have been ‘against’ us. There’s a lot to learn from knowing that. It’s hard to remember who we’ve been when our community is so transient that every four or five years, UW hits reset. Yet the archives remind me that every time I step onto Library Mall for a rally, I join a long tradition of other students, often standing against the University, who organized and fought. The memory of those actions lives here in the University Archives, tucked away by the lake shore dorms, quietly humming away on the fourth floor of Steenbock Library.

In the time that I’m here, I seek to study student activism from the Vietnam War era, focusing specifically on the political organizing of students of color. I want to learn about presence of organizations like Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), up-and-coming chapters of the Black Panthers and Asian American student organizations, as well as how the University responded to these organizations and demonstrations. I want to know how they organized, how they talked to each other, who tried to erase them, what impact they made. I hope that the materials will guide my research and lead me into new understandings. I also want to be aware of absent voices -- whose papers are not here in the archive? Have not been sorted or tagged? Honoring absence in history is itself part of the history, and can itself be an act of restorative justice. These are all things I hope to bear in mind in my time here.

As I go deeper, I hope to connect other students to the wonderful staff and space here at the archives. I want to bring peers into the work. Collective memory is at the heart of who we are and who we become, and history can never be learned alone. I can’t wait to get started.

- Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Organizing with History in Mind

How I think about activism has changed since I’ve started studying history: What does it mean to document struggle?

The archives serve a practical and poetic purpose: to document what’s happened, to collect remnants of place and time -- and through these masses of materials, provide a context for the world unfolding around us today.

The archives aren’t always successful in doing that. The past few weeks I’ve been deep-diving into 1960s and 70s-era documents, trying to orient myself to the issues of the student body at the time. I wanted to know what kind of activism and concerns my counterparts from 60 years ago were thinking about. There’s a lot of materials about Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a New Left organization that organized a lot of anti-war protests, among other topics. There are massive files with the internal memos from the Chancellor’s office and the administration. Newspaper clippings are in great abundance.

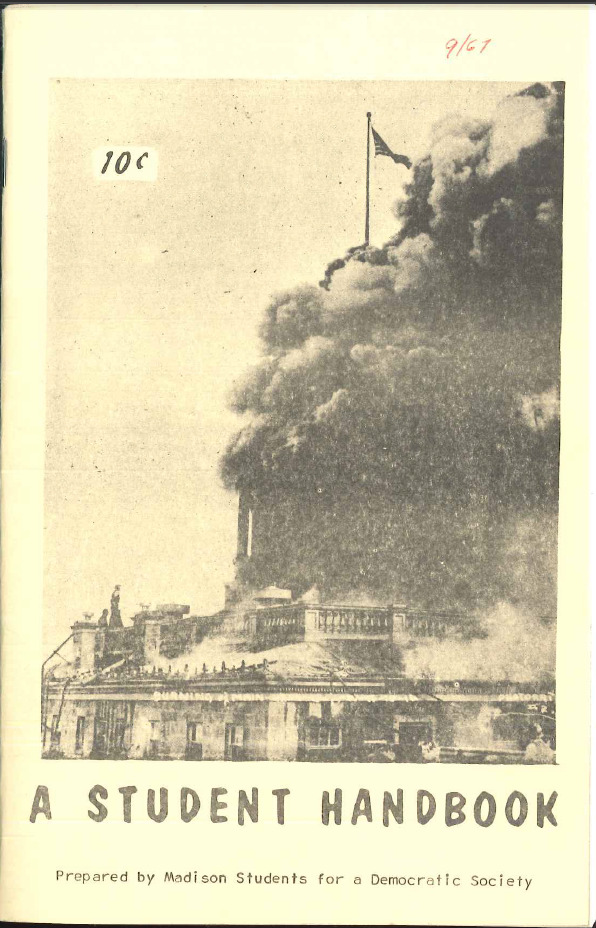

I’ve found a lot of really cool, exciting materials, like an SDS student disorientation pamphlet called “A Student Handbook”, with a picture of Bascom Hall’s no-longer-existing dome set ablaze from 1916 on the cover. I’ve found a collection of disorientation guides from 1992 until 2014, which live in the pamphlet collection of WHS. I found an internal newsletter called “Like it Is,” written by the administration so that staff members could stay abreast of the hundreds of protests that seemed to be happening weekly during 1969.

All of these things are energizing and so invigorating to look at, but there’s a theme: these are all materials that were largely produced by white folks on campus and/or people in positions of relative power. And it makes sense -- for years, the archives have been run almost exclusively by white people and existed solely for the purpose of recording the things that the University Administration thought was important: official documents and correspondence, acceptable events, et cetera. Even the fact that the three main boxes of student activism are titled “Student Unrest” tells us something about who was looking at this history and dictating what was meaningful and what wasn’t worth keeping.

Though I’m getting really into hunting for the SDS materials, there’s a reason why they’re available and other contemporaneous student groups’ materials aren’t. Groups like Concerned Black People (previously Concerned Black Students) and the Black Council at UW, for example, were significant organizing forces, but as a white student in 2018, I was only able to learn about them tangentially through UW Archives materials which mention or include them, rather than on their own terms in their own writings. I’m certain there are many other major groups whose materials went uncollected by the old archival staff and for that reason, aren’t included in this post.

While some of these “less-collected” groups may have their materials in the Wisconsin Historical Society (and I know that WHS tends to collect a lot of activist materials from the Black Freedom Movement in general), the fact that they are absent from the University’s archives is telling. While the staff today is very reparations and justice-oriented, there is a sense that this attitude is profoundly new in a building racked with portraits of old white guys. If a good historian is supposed to let the materials guide the work, then what should I do with my awareness that the materials themselves have omitted the most important, marginalized stories?

I’m sure I’ll do more writing about the narrative desecration created by omission, but for now I want to focus on how understanding these gaps has impacted the way I approach on-campus activism and organizing in general.

The more I see what is and isn’t here in the University Archives, the more I want to repair the damage that’s been done going forward. While I don’t think it’s my job right now to go off into the corners of Madison and search for people to donate materials (though it is certainly a job that must be done), I think it is my responsibility as a person in this position of power to advocate for more and wider student voices to be added to the archives in 2018. There’s no reason the archives should lag behind by a decade: there’s plenty of organizing materials from the last two years alone that need their own folders right now.

Just this past week, the Wisconsin Union Board decided to remove the names of Porter Butts and Fredric March from the Union facilities, two men who were affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan in their time as students. The public discourse surrounding this issue has taken months, and I found myself upset (though not shocked) by the number of older white community members who showed up on Tuesday afternoons at public fora to talk about how strongly they feel that the names of these men must stay up. I also attended one open forum and spoke in strong condemnation of preserving the names, instead advocating for their removal and the creation of an exhibit regarding restorative justice at UW, documenting the discourse about removing the names, and education about reparations at the University. (I might add that I thought it was incredibly unfair of the board to hold this debate during the summer, when many students are away, especially considering this is an issue that effects students directly).

Though I couldn’t be present at the final vote, my friend and ASM Vice Chair Yogev Ben-yitzchak texted me to tell me the verdict. While he was pleased with the decision, he was frustrated at how many people in the room weren’t sure, or were in favor of keeping the names up. To him, it seemed clear that publicly honoring men who had been inducted into an on-campus white supremacist organization perpetuated harm, making UW an even more toxic place for marginalized students. But other white community members didn’t see it that way.

This decision to remove the names is an important historical precedent. So, recording student voice for the purpose of the archives is necessary. I asked if Yogev would write up his feelings about the decision for me. “Well, they’re going to be doing an article about it.” He said. “It should be coming out soon.”

“No,” I said, “I want to hear how you feel about it. As if you’re just telling me what happened.”

The archival boxes are stocked full of Daily Cardinal articles and newspaper clippings about events, but much rarer are student sentiments, personal records of how things shook out. Not only is that stuff more interesting, but having that kind of narrative ensures that future historians really know exactly how subjects feel -- and there’s less chance it can be overridden or taken out of context. “If you send it to me, I’ll put it in the archives. And then future students can read it and will know how it felt to be there. They can’t pretend this didn’t matter.”

While Yogev is clearly a student in position of greater power, I realized that this kind of proactive documentation is a form of activism itself. To encourage my peers to create testimony and save it is a way to protect against erasure. If we have our accounts in the archives, those who would prefer to paint history as something apolitical or “on a moral arc” can’t get away with it. They’ll have to confront our testimonies first.

In the example of Porter Butts and Fredric March, it’s easy to see how in 20 years the University will brag about how “progressive” they were in removing the names. But if we have these stories of how difficult the discourse was, how against change the community was, we can hold the school and the community accountable for its racism and its disinterest in creating restorative justice. Creating these records means that we can use them later as proof of wrongs, and from there can begin the process of reparations.

This is true for every student issue -- especially issues that directly impact marginalized student communities. As part of my work, I’d like to run a workshop or two about documenting actions, the importance of writing after a protest, et cetera. I’d also like to help the archives themselves make it as easy and intuitive as possible for students to submit materials to the archives.

I hope that in my role as a student historian, I can do the work of bringing in those modern testimonies from my peers and ensuring that, while our collections of the Vietnam War era may be overwhelmingly white, the records of the Trump era are not. I want to make sure that we will not be erased. I want to make sure that my peers dictate their own history on their own terms. It’s part of my job to ensure the future University community will know the #TheRealUW and can see themselves in our struggles.

- Rena Yehuda Newman, Student Historian

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring Jewish On-Campus Political Action & Cultivating a Personal, Intersectional Historical Practice

I’m at the stage in my work at the archives when I’m about to start writing up my research proposal. I’ve spent the last couple weeks sifting through materials related to SDS, the Black Student Strike, the TA strike, and other student movements. The 1967 “A Student Handbook” produced by SDS has been a really wonderful and applicable guide to the type of political energy on campus at that time (cover shown above).

However, as I’ve been looking through the materials, I’ve also been asking whose voices are present and whose aren’t. The materials in the UW archives are largely white and male, and while many of the SDS materials pay lip service to antiracist ideas, the collections and activism itself is not particularly intersectional.

My main subject(s) of inquiry for my research at the archives follow these questions:

Who was organizing on campus from 1954 to 1976?

What identities, geographical backgrounds, and ideologies were present in political action at UW during this era?

Whose voices were present but their materials largely absent within archival collections?

What groups had large student membership and what were the relationships between these political groups like? What tensions and affinities existed between these active students?

What happened to the political energy on campus after the Vietnam war ended?

What issues were students dealing during this era which continue on today? What is “campus continuity” with such a transient population? I.e., what is the relevance of this for students today and what can we learn from the struggles of our predecessors?

An overarching theme of my research is about relationships between student groups with special interest with regards to racial dynamics in organizing. For example, how did SDS interact with local chapters of the Black Panthers? Was “Concerned Black People” an SDS-run group or just affiliated? How did certain groups support or hinder the establishment of the African-American studies department?

I wrote previously about the contradictions and tensions inherent to investigating black history as a white student historian. Not only might I miss crucial meanings, my whiteness in this work may actually perpetuate the same harms that I want to help repair, and good intentions do not alone mitigate damaging impact. Additionally, I worry about my interest in black student organizing being voyeuristic -- that I may be interested in them for motives that are more centered around my whiteness, projecting the white gaze onto the research. Yet, just because it is harder (socially, emotionally, politically) for me to be researching black student history on this campus doesn’t mean I shouldn’t engage in this kind of study. So, how can I research these topics from a genuine, honest, and reparative place while acknowledging how my own identities factor into the work?

A few days ago I realized that I hadn’t read a lot of significant discourse about Jewish students’ organizing on campus. As a Jewish student, I’m interested in this history -- on a personal level I know how much representation matters. I’ve been paging through “University of Wisconsin: A History” by E. David Cronon and John Jenkins and found mentions of Daily Cardinal Editor-in-Cheif ‘70-’71 Rena Steinzor, and New Year’s Gang members Leo Burt and David Fine. I went to the Wisconsin Historical Society and looked through the Alan Stein papers. The more I read into historical campus activist figures, the more I thought to myself, “There are a lot of pretty Jewish-sounding names.”

I’m clearly profiling my own people here, but there’s something to that sense of recognition. I’m not entirely sure that Sterling Hall Bombers are really the kind of representation I’m looking for, but I’m still curious: how many Jews were organizing at this time and what (if anything) did their identity as Jews mean to them?

Since I’ve only been thinking about this for a little while, I haven’t looked that deeply into the collections regarding Jewish organizing. Though I don’t know how many materials exist in the archives, I have a hunch that there weren’t very many (if any) groups which explicitly called themselves Jewish political organizations. It makes sense -- things would get antisemitic really fast. It follows a classic derogatory trope: Jews have historically been accused of “meddling” in political affairs and having too much power and influence. Practically speaking, most Jews involved in that era of leftist organizing probably wouldn’t want to advertise their identity. And it’s possible that many secular Jews engaged in UW Vietnam War-era activism didn’t really see their Judaism as a primary or motivating factor in their work. Yet, there’s a thru-line and history of political action within the Jewish community -- and a pretty radical streak at that. My Jewish identity is a strong, powerful basis for my politics. As a way of finding myself in the work and centering my work in my lived reality, I’d love to explore how era-Jews were engaged in campus activism. What did that identity mean to them? Were they affiliated with any Jewish organizations? Did their identity as Jews impact their relationships to other student organizers, i.e, black, latinx, and asian organizers? Investigating my own assumptions, are the people I’ve listed above even Jewish?

I believe that it’s important to know yourself and your own community as preparation for interacting with the greater community. Then, when you’re finally sitting at the table with others, also strong with their own self-knowledge and introspection, the conversation becomes more mutually meaningful.

Returning to my questions about how my whiteness may impact my work, maybe more seriously researching white identity and Jewish identity and white Jewish identity (p.s., not all Jews are white) on campus at this time, alongside my other inquiries might be a more mutually respectful way to approach any research about black, latinx, and asian student organizing on campus. Ultimately, I think the experience of learning about “myself” through my own identities as a way of learning about the work of others will be fruitful. This practice can help me see my own “skin in the game,” or my direct connection to the stakes of what I’m researching and better prepare to engage in restorative justice through my research here at the archives.

– Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them), Student Historian

#UWStudentHistory

#UW-Madison#StudentHistory#UWStudentHistory#student activism#history#Jewish#SDS#BlackPanthers#Wisconsin

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Activism, White Historian

As I enter the beginnings of my research, I’ve been trying to orient myself to the student climate of the 1960s and 1970s. I’ve started reading Cronon and Jenkins’ “The University of Wisconsin, A History: 1945 - 1971″ which gives a clear and student-oriented overview of many protests and movements occurring at UW-Madison, with an eye towards the administration’s end of things. I found myself looking up the footnoted articles in the Daily Cardinal and Badger Herald newspaper collections and paging through the days in 1969, slowly getting my feet grounded in a decade fifty years back.

It’s easy to get caught up in the advertisements (“The Community Co-Op: Free Kool-Aid! Friendly cheerful atmosphere // a living room, even”) and exciting to see the kinds of events on a daily basis. It seems that almost every day there’s another protest or action or organized meeting being publicized through the increasingly-leftist Daily Cardinal, which seemed to play a major role in organizing and supporting events like a Wisconsin Student Association “disorientation” symposium for Freshman (with 1400 first-years attending) and providing information about the Unionization of the student body through op-eds and investigative reporting.

Alongside Anti-Vietnam activism, vehement protests of campus ROTC, and actions for greater student control over academic departments arose the Black Student Strike, one of the largest actions of the era in which an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 students participated in marches and walkouts. The Black Strike was enormous, with the goals of creating a Black Studies Department with co-equal student voice, moving UW-Madison to admit three black students kicked out of UW-Oshkosh for “disorderly conduct”, among the “13 Demands”. The Wisconsin State Legislature even got involved in the backlash and passed a resolution calling for the expulsion of any student blocking access to a University Building (Sound familiar? Flashback to the police presence at the Gordon’s Dining Hall protest, ready to arrest students for blocking entrance into the facility, not to mention the related Regents’ new “[Anti-] Free Speech Policy”).

The activism of the Black Strike was extremely effective and wide-scale, and demonstrates scores of lessons for today’s young organizers. Which brings me to a personal question: What does it mean for me as a young, white historian to be studying this black and brown history? And for what end?

In high school, I was blessed with incredible, compassionate, and radical black educators who did the labor of teaching me about American racism, the pervasive force of whiteness, institutions of oppression, and collective liberation. These educators instilled in me the understanding that it is my obligation as a white American to leverage my privileges in order to dismantle white supremacy -- by uplifting voices of marginalized communities, by actively denying complicity in perpetuation of harm, and recognizing when I should speak and when I should listen. This has created in me a reverence for the brilliance of Black organizing and philosophy of struggle, especially as a young trans and Jewish person who often looks to those narratives for guidance in my own organizing. Black trans women throwing bricks at cops are the reason I can exist today. Miss Major Griffin-Gracy once told me that in trans memory, we are all “like champagne glasses,” cascading from one generation to the next. So how do I honor their work and legacy?

Now, in this privileged position of Historian in Residence, with remarkable access to all sorts of stories told/heard and told/unheard, I feel that I’m in a dilemma. I’ve entered into a too-long tradition of white historians curating what should be collective history. I feel that my project in the archives must embody an effort to use the archives for the purpose of reparations.* But as a white person, I cannot do this alone. Engaging with this material without questioning my place in it creates many risks: the artifacts I find may mean one thing to me but something else entirely to the communities who created them. I risk engagement purely for selfish purposes of learning, not for the purpose of restorative justice. I risk excluding the same voices I want to learn from -- and if that’s not exploitation, I don’t know what is. Even with vigilance, my whiteness will harm the work in ways I may not be conscious of.

So this leads me to questions of action. Should I just avoid the risk of doing more racist history and focus on activism regarding less “explicitly racial” issues? That would be lazy and ridiculous. Intersectionally speaking, there’s no such thing -- Vietnam-era activism was so bound up in racial politics there is no separation of the two.

While I want to do race-critical research, I think I need to be hyper-aware of my own limitations. I resolve to bring others into this research, especially my peers and co-organizers of color. There must be Black, Latinx, APIDA, Native student perspectives in this work. But since they’re not being compensated for that labor, it’s important I take on a research topic that doesn’t require their constant presence or tokenization -- rather, demands me to reach out and act as a bridge (share power), while examining materials within my own realm of knowledge and identities in a meaningful way. Hopefully I can work with the archives’ staff to find some way to make sure my peers’ efforts are mutually beneficial. My process of research must also include a constant personal reflection on my own identities, especially my whiteness here in the historically-white space of the archives.

This might mean a project about collaboration between student activist communities in the late 1960s & early 1970s. There’s plenty to share in those materials, especially since there’s (literally) something for everyone. I’d love to give my peers a chance to see themselves in campus history -- or open myself up to rebuke about how they don’t see themselves in campus history, and that it’s obnoxious to assume they should.

Memory is a collaborative process. I hope this project can be something that actively brings present day students together to discuss and understand the history of this place, what it means for us, and how it can help liberate us going forward. That means I have to get over my white fragility, leverage my power in the archives, and bring more voices to table. Maybe we’ll even have a potluck.

-- Rena Yehuda Newman (They/Them)

#UWStudentHistory

*Anna Robinson-Sweet, “Truth and Reconciliation: Archivists as Reparations Activists” The American Archivist Vol. 81 (Spring/Summer 2018). 23-37.

14 notes

·

View notes