#read: i was an english major but there are several books on goodreads that only i and grady hendrix have read

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

honoring the pretension inherent in me by having a commonplace book but the first entry is lyrics from cobra starship's "prostitution is the world's oldest profession (and i, dear madam, am a professional)"

#just ramblings of aurora#read: i was an english major but there are several books on goodreads that only i and grady hendrix have read#him because he wrote paperbacks from hell#me because my taste is trash#i was ane nglish major but DID write an essay about 3oh3 for my college's lit journal#i was an english major but my favorite “literary” author is bret easton ellis#AND HE'S A FUCKING HORROR AUTHOR AND I WILL FIGHT YOU ON THAT#every agrees about american psycho but have you READ the shards???#have you READ glamorama????#do we forget what happened to that poor asian kid???#in glamorama???#less than zero's literary but like come ON#come ON remember GLAMORAMA or at least PRETEND YOU GOT THROUGH THE FIRST SIXYT PAGES OF NAMEDROPS

0 notes

Text

Blog Tour & Arc Review: Killers of a Certain Age by Deanna Raybourn

Welcome to the Killers of a Certain Age book tour with Berkley Publishing Group. (This blog tour post is also posted on my Wordpress book review blog Whimsical Dragonette.)

Order

Add to Goodreads

Publishing Date: September 6, 2022

Synopsis:

Older women often feel invisible, but sometimes that's their secret weapon. They've spent their lives as the deadliest assassins in a clandestine international organization, but now that they're sixty years old, four women friends can't just retire - it's kill or be killed in this action-packed thriller. Billie, Mary Alice, Helen, and Natalie have worked for the Museum, an elite network of assassins, for forty years. Now their talents are considered old-school and no one appreciates what they have to offer in an age that relies more on technology than people skills. When the foursome is sent on an all-expenses paid vacation to mark their retirement, they are targeted by one of their own. Only the Board, the top-level members of the Museum, can order the termination of field agents, and the women realize they've been marked for death. Now to get out alive they have to turn against their own organization, relying on experience and each other to get the job done, knowing that working together is the secret to their survival. They're about to teach the Board what it really means to be a woman--and a killer--of a certain age.

My Rating: ★★★★

*Author Bio, my review, and favorite quotes below the cut.

Author Bio:

New York Times and USA Today bestselling novelist Deanna Raybourn is a 6th-generation native Texan. She graduated with a double major in English and history from the University of Texas at San Antonio. Married to her college sweetheart and the mother of one, Raybourn makes her home in Virginia. Her novels have been nominated for numerous awards including two RT Reviewers’ Choice awards, the Agatha, two Dilys Winns, a Last Laugh, three du Mauriers, and most recently the 2019 Edgar Award for Best Novel. She launched a new Victorian mystery series with the 2015 release of A CURIOUS BEGINNING, featuring intrepid butterfly-hunter and amateur sleuth, Veronica Speedwell. Veronica has returned in several more adventures, most recently AN IMPOSSIBLE IMPOSTOR, book seven, which released in early 2022. Deanna's first contemporary novel, KILLERS OF A CERTAIN AGE, about four female assassins on the cusp of retirement publishes in September 2022.

My Review:

This book was very good. I wasn’t sure what to expect, having never read a Deanna Raybourn book, and I was pleasantly surprised. The story whizzed along at a good clip, the characters were for the most part well-developed and interesting. The pacing was breathless as they raced against time to carry out heists and murder the men who are trying to murder them.

I came to really appreciate Billie, as it was in her POV for the most part, but I did feel that the other three women blurred together a bit and weren’t as distinct as I would have liked.

I very much approve of the casual inclusion of LGBT+ characters and relationships. That always makes a book feel much more friendly, and it was done so naturally that I barely even registered it.

I also really really appreciate that the main characters were 'women of a certain age' and (despite being expert assassins) they felt very authentic. There were many mentions of the plans having to be adapted to their older bodies. Despite it, they still kicked ass. They were competent and capable AND dealing with things like hot flashes and muscles and stamina that weren't what they once were. It made for such a nice contrast to the usual teenagers/twenty-something protagonists I usually read about.

I wasn’t sure at first if I was going to like it. There were a few issues I had with it:

The placement of the ‘past’ sections was sometimes jarring and I occasionally got confused about where and when they were. I did become more used to this as I went along, but it took me out of the flow of the story on more than one occasion.

The action scenes - which, to be fair, were a large chunk of the book - were just a tad too clinical. They read almost like newspaper reports. I don’t know if this is just a style common to thrillers - I haven’t read many of them. I feel like the simple language and not-flowery writing are a staple of the genre, but I’m not sure about the descriptions of fight scenes. As the book progressed this bothered me less and less, however, so it might have improved or I might have gotten used to it.

One thing that did bother me consistently through the book was that it was a tad vulgar for my tastes. I do appreciate the bluntness with which things not normally talked about are discussed among the women, but there were so many instances of descriptions of sexual harassment from their targets (which they had to put up with with a smile which definitely made the targets unsympathetic very quickly). Even more off-putting to me (and more common within the story) was the way that the (many) murders were described. Not just how they looked, but how they felt, how they sounded, how they smelled… I get that they are assassins and yes, they do kill a lot of people over the course of the book, but I just didn’t want that much familiarity with the deaths.

I did appreciate the very feminist slant to it all, and the way the men’s casual sexism was used to increase support for the women. Also the way that the four of them used the ‘old women are invisible’ idea to their advantage in order to further their schemes.

The story was very compelling and I found it difficult to put down. I would also probably read it again and will definitely be recommending it to others.

*Thanks to NetGalley and Berkley for providing an e-arc for review.

Favorite Quotes:

And every job was a chance to prove Darwin’s simple maxim. Adapt or die. We adapted; they died.

---

Three old women, nodding their heads like the witches in Macbeth. I’d known them for two-thirds of my life, those impossible old bitches. And I would save them or die trying.

---

Women are every bit as capable of killing as men.

#deanna raybourn#killers of a certain age#berkley#contemporary thriller#netgalley#arc review#shilo reads#this was a lot of fun#i definitely recommend it#blog tour

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr Top 50 Books of 2022 - thoughts from a reader and writer

I was bored and tired on Wednesday so I did this for fun. Don’t take it too seriously and don’t mind me sounding cynical at times.

intro

I am a writer obsessed with book publishing, both traditional and indie. I’ve been trying to understand the trends in the modern book world for the last couple years and I have some info from the querying/trying to get published side of the deal. I am also a reader of books that don’t seem to fit modern trends very much. I both read and write primarily in 2 genres: science fiction and 20th-21st century literary. I thought looking at the books popular on tumblr, a social media that does not fit many online molds, would be fun and informative.

methods

I took the tumblr top 50 books of 2022 list and copypasted it to excel. I cleaned up the data and added three columns to the original title and author: genre, age category, and year of publication. I got this data from goodreads and wikipedia.

Several important notes on this methodology: genre is a fuzzy category and many books on this list would fit multiple labels. I tried to stick with the most characteristic, e.g. listed first in goodreads or listed most often on google. For books before the 20th century, I labeled them as literary even though they also have their genres, e.g. Pride and Prejudice I labeled as literary though it is also a romance. There were a couple books that seemed in between YA and middle grade, and again I tried to pick the most often listed category. Lastly, Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad appear on this list, somehow, and in order not to mess up my year of publication stats, I listed year of pub as the year it was translated into English and published in Europe.

Then I calculated super basic average and count descriptive stats. I also found some info about the tumblr users to inform my conclusions.

results

the age category split is pretty even between YA and adult: 28 adult, 20 YA, 2 middle grade

it is exactly 5:5 adult and YA in the top 10

however, if we only look at books published after 2010, YA jumps to above 50% (14 out of 23)

fantasy is by far the most popular genre, 26 books out of 50, 16 out of 23 published from 2010 (not counting science fantasy)

fantasy YA specifically is the most popular combination, with 11 books out of 23 published from 2010 being in that category

there is only 1 book on the whole list that can be classified as pure sci-fi: 1984 by George Orwell, published in 1949 - though there are a few science fantasy books on the list, e.g. The Locked Tomb series

there are also a few “classics” (aka literary on my list), 2 thrillers (specifically dark academia books), and 2 contemporaries - the rest of the genres are 1 book per category

the average publication year of a tumblr top 50 book is 1960

books published after 2010 are less than 50% of the list, and there are less than 10 books published in the last 5 years - out of them 1 book that hasn’t even been published yet

the vast majority of these books are not what I would call a “tumblr-specific fandom”, with the exception of maybe The Locked Tomb (though it is very popular on Twitter) and some classics that have seen a resurgence of popularity due to chapter-by-email fandoms

discussion

In my opinion, tumblr trends are pretty typical of modern online and industry trends in general. First of all, a note on books’ popularity as a whole: it’s not great. The top post in the top book of 2022 sits under 1k notes, while the top posts of the top TV show of 2022 range in the above 5k notes. Also, the top 50 books list itself was on page 6 out of 7 in the tumblr fandom review. Despite common opinion, millenials and gen Z actually read more than some previous generations, especially because by far the bulk of all readers are children and teenagers. However, books are obviously less popular than other media. I’d guess that more people on tumblr read fanfic of TV shows and movies than original books, even when those properties are based on books. This is not a criticism or a moral judgement, but simply my intuition about the state of media popularity.

It is also not surprising that, by far, the most popular categories of books on tumblr are YA fantasy and old classic. From querying experience, I know that YA is the absolute king of books. A querying YA author has an above 30% chance to be agented eventually, while e.g. a science fiction author has around 3%. In personal experience of going to bookshops multiple times a week, YA, especially YA fantasy, absolutely dominates the shelves. Fantasy itself is much more popular than almost any other genre: it often gets lumped with sci-fi and horror, which leads to the shelf/area being 80% fantasy and 20% old sci-fi classics and Stephen King. I’ve no idea when and how fantasy defeated science fiction so brutally, but it makes me sad. No beef with fantasy readers or writers, I just wish there was space for all of us.

The average publication year is also not surprising, considering trad pub makes way more money publishing old classics than new books. As I’ve said, the chapters by email trend raised their popularity even further. In general, it takes a book a while to get popular. With the exception of The Locked Tomb, which appears to be an outlier on almost every aspect, the top 10 is dominated by books older than 10 years at least.

The popularity of YA surprises me to some extent, considering it is, by definition, a category aimed at teenagers. Again, despite common belief, tumblr demographics are much more skewed towards people aged 20-35. My guess is that people who read YA as teenagers continue to read it in their 20s because they know they like it and there’s a great abundance of new books. In comparison, middle grade rarely remains popular among adults. On the other hand, the prevalence of classics and what I would call politically/socially important books like Maus, 1984, Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, etc, tells me that there is also a fair amount of people who read for reflection/education. Not that those books are not enjoyable reads or that there is a good or bad way to read, I’m just curious whether these are separate demographics or whether an average tumblr person who posts about books goes between Percy Jackson and The Illiad on their reading list.

Among all these trends, as I’ve said, The Locked Tomb appears a huge outlier, considering its main ship also made it to the top 100 ships of 2022. I don’t know what it is - the lesbians, the necromancy, the sword fighting - but this book just broke through all the YA fantasy and became like A Proper Fandom. I am currently reading Gideon the Ninth because a few people told me it sounds like a good comp title from the novel I am currently querying and, around 100 pages in, I personally think it’s the memes. Taking notes...

conclusion

Despite tumblr seeming like the quirky teenage girl of webbed sites, its reading trends are somewhat typical to the modern industry. And what is typical of the modern industry is the dominance of super old titles, big names, YA in general and YA fantasy in particular, and a great difficulty of new books to become popular. Of course this data is limited to 50 books (I would love to look at the top 200 for example) so obviously it’s gonna be dominated by big names and classics, but I really thought at least the top 50 to 30 would look a bit more diverse. Oh well, I guess I’ll carry on in the querying trenches.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

january reading

why does january always feel like it’s 3 months long. anyway here’s what i read in january, feat. poison experts with ocd, ants in your brain, old bolsheviks getting purged, and mountweazels.

city of lies, sam hawke (poison wars #1) this is a perfectly nice fantasy novel about jovan, who serves as essentially a secret guard against poisoning for his city state’s heir and is forced to step up when his uncle (also a secret poison guard) and the ruler are both killed by an unknown poison AND also the city is suddenly under a very creepy siege (are these events related? who knows!) this is all very fine & entertaining & there are some fun ideas, but also... the main character has ocd and SAME HAT SAME HAT. also like the idea of having a very important, secret and potentially fatal job that requires you to painstakingly test everything the ruler/heir is consuming WHILE HAVING OCD is like... such a deliciously sadistic concept. amazing. 3/5

my heart hemmed in, marie ndiaye (translated from french by jordan stump) a strange horror-ish tale in which two married teachers, bastions of upper-middle-class respectability and taste, suddenly find themselves utterly despised by everyone around them, escalating until the husband is seriously injured. through several very unexpected twists, it becomes clear that the couple’s own contempt for anyone not fitting into their world and especially nadia’s hostility and shame about her (implied to be northern african) ancestry is the reason for their pariah status. disturbing, surprising, FUCKED UP IF TRUE (looking back, i no longer really know what i mean by that). 4/5

xenogenesis trilogy (dawn/adulthood rites/imago), octavia e. butler octavia butler is incapable of writing anything uninteresting and while i don’t always completely vibe with her stuff, it’s always fascinating & thought-provoking. this series combines some of her favourite topics (genetic manipulation, alien/human reproduction, what is humanity) into a tale of an alien species, the oankali, saving some human survivors from the apocalypse and beginning a gene-trading project with them, integrating them into their reproductive system and creating mixed/’construct’ generations with traits from both species. and like, to me, this was uncomfortably into the biology = destiny thing & didn’t really question the oankali assertion that humans were genetically doomed to hierarchical behaviour & aggression (& also weirdly straight for a book about an alien species with 3 genders that engages in 5-partner-reproduction with humans), so that angle fell flat for me for the most part, altho i suppose i do agree that embracing change, even change that comes at a cost, is better than clinging to an unsustainable (& potentially destructive) purity. where i think the series is most interesting is in its exploration of consent and in how far consent is possible in extremely one-sided power dynamics (curiously, while the oankali condemn and seem to lack the human drive for hierarchy, they find it very easy to abuse their position of power & violate boundaries & never question the morality of this. in this, the first book, focusing on a human survivor first encountering the oankali and learning of their project, is the most interesting, as lilith as a human most explicitly struggles with her position - would her consent be meaningful? can she even consent when there is a kind of biochemical dependence between humans and their alien mates? the other two books, told from the perspectives of lilith’s constructed/mixed children, continue discussing themes of consent, autonomy and power dynamics, but i found them less interesting the further they moved from human perspectives. on the whole: 2.5/5

love & other thought experiments, sophie ward man, we love a pierre menard reference. anyway. this is a novel in stories, each based (loosely) on a thought experiment, about (loosely) a lesbian couple and their son arthur, illness and grief, parenthood, love, consciousness and perception, alternative universes, and having an ant in your brain. it is thoroughly delightful & clever, but goes for warmth and humanity (or ant-ity) over intellectual games (surprising given that it is all about thought experiments - but while they are a nice structuring device i don’t think they add all that much). i haven’t entirely worked out my feelings about the ending and it’s hard to discuss anyway given the twists and turns this takes, but it's a whole lot of fun. 4/5

a general theory of oblivion, josé eduardo agualusa (tr. from portuguese by daniel hahn) interesting little novel(la) set in angola during and after the struggle for independence, in which a portuguese woman, ludo, with extreme agoraphobia walls herself into her apartment to avoid the violence and chaos (but also just... bc she has agoraphobia) with a involving a bunch of much more active characters and how they are connected to her to various degrees. i didn’t like the sideplot quite as much as ludo’s isolation in her walled-in flat with her dog, catching pigeons on the balcony and writing on the walls. 3/5

cassandra at the wedding, dorothy baker phd student cassandra returns home attend (sabotage) her twin sister judith’s wedding to a young doctor whose name she refuses to remember, believing that her sister secretly wants out. cass is a mess, and as a shift to judith’s perspective reveals, definitely wrong about what judith wants and maybe a little delusional, but also a ridiculously compelling narrator, the brilliant but troubled contrast to judith’s safer conventionality. on the whole, cassandra’s narrative voice is the strongest feature of a book i otherwise found a bit slow & a bit heavy on the quirky family. fav line is when cass, post-character-development, plans to “take a quick look at [her] dumb thesis and see if it might lead to something less smooth and more revolting, or at least satisfying more than the requirements of the University”. 3/5

the office of historical corrections, danielle evans a very solid collection of realist short stories (+ the titular novella), mainly dealing with racism, (black) womanhood, relationships between women, and anticolonial/antiracist historiography. while i thought all the stories were well-done and none stood out as weak or an unnecessary inclusion, there also weren’t any that really stood out to me. 3/5

sonnenfinsternis, arthur koestler (english title: darkness at noon) (audio) you know what’s cool about this book? when i added it to my goodreads tbr in 2012, i would have had to read it in translation as the german original was lost during koestler’s escape from the nazis, but since then, the original has been rediscovered and republished. yet another proof that leaving books on your tbr for ages is a good thing actually. anyway. this is a story about the stalinist purges, told thru old bolshevik rubashov, who, after serving the Party loyally for years & doing his fair share of selling people out for the Party, is arrested for ~oppositional activities. in jail and during his interrogations, rubashov reflects on the course the Party has taken and his own part (and guilt) in that, and the way totalitarianism has eaten up and poisoned even the most commendable ideals the Party once held (and still holds?), the course of history and at what point the end no longer justifies the means. it’s brilliant, rubashov is brilliant and despicable, i’m very happy it was rediscovered. 5/5

heads of the colored people, nafissa thompson-spires another really solid short story collection, also focused on the experiences of black people in america (particularly the black upper-middle class), black womanhood and black relationships, altho with a somewhat more satirical tone than danielle evans’s collection. standouts for me were the story in letters between the mothers of the only black girls at a private school, a story about a family of fruitarians, and a story about a girl who fetishises her disabled boyfriend(s). 3.5/5

pedro páramo, juan rulfo (gernan transl. by dagmar ploetz) mexican classic about a rich and abusive landowner (the titular pedro paramo) and the ghost town he leaves behind - quite literally, as, when his son tries to find his father, the town is full of people, quite ready to talk shit about pedro, but they are all dead. it’s an interesting setting with occasionally vivid writing, but the skips in time and character were kind of confusing and i lost my place a lot. i’d be interested in reading rulfo’s other major work, el llano en llamas. 2.5/5

verse für zeitgenossen, mascha kaléko short collection of the poems kaléko, a jewish german poet, wrote while in exile in the united states in the 30-40s, as well as some poems written after the end of ww2. kaléko’s voice is witty, but at turns also melancholy or satirical. as expected i preferred the pieces that directly addressed the experience of exile (”sozusagen ein mailied” is one of my favourite exillyrik pieces). 3/5

the harpy, megan hunter yeah this was boooooooring. the cover is really cool & the premise sounded intriguing (women gets cheated on, makes deal with husband that she is allowed to hurt him three times in revenge, women is also obsessed with harpies: female revenge & female monsters is my jam) but it’s literally so dull & trying so hard to be deep. 1.5/5

the liar’s dictionary, eley williams this is such a delightful book, from the design (those marbled endpapers? yes) to the preface (all about what a dictionary is/could be), to the chapter headings (A-Z words, mostly relating to lies, dishonesty, etc in some way or another, containing at least one fictitious entry), to the dual plots (intern at new edition of a dictionary in contemporary england checking the incomplete old dictionary for mountweazels vs 1899 london with the guy putting the mountweazels in), to williams’s clear joy about words and playing with them. there were so many lines that made me think about how to translate them, which is always a fun exercise. 3.5/5

catherine the great & the small, olja knežević (tr. from montenegrin by ellen elias-bursać, paula gordon) coming-of-age-ish novel about katarina from montenegro, who grows up in titograd/podgorica and belgrad in the 70s/80s, eventually moving to london as an adult. to be honest while there are some interesting aspects in how this portrays yugoslavia and conflicts between the different parts of yugoslavia, i mostly found this a pretty sloggy slog of misery without much to emotionally connect to, which is sad bc i was p excited for it :(. 2/5

the decameron project: 29 new stories from the pandemic, anthology a collection of short stories written during covid lockdown (and mostly about covid/lockdown in some way). they got a bunch of cool authors, including margaret atwood, edwidge danticat, rachel kushner ... it’s an interesting project and the stories are mostly pretty good, but there wasn’t one that really stood out to me as amazing. i also kinda wish more of the stories had diverged more from covid/lockdown thematically bc it got a lil repetitive tbh. 2/5

#the books i read#long post#sonnenfinsternis is so good the audiobook nearly made me cry in the supermarket

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Since March, I have been sending discreet messages to authors of young adult fiction. I approached 24 people, in several countries, all writing in English. In total, 15 authors replied, of whom 11 agreed to talk to me, either by email or on the phone. Two subsequently withdrew, in one case following professional advice. Two have received death threats and five would only talk if I concealed their identity. This is not what normally happens when you ask writers for an interview.

[An] author I will call Chris is white, queer and disabled. Chris has generally found the YA community friendly and supportive during a career spanning several books, but something changed when they announced plans for a novel about a character from another culture. Later, Chris would discover that an angry post about the book had appeared anonymously on Tumblr, directing others to their website. At the time, Chris only knew that their blog and email were being flooded with up to 100 abusive messages a day.

“These ranged from people telling me that … I was a sick pervert for tainting [their] story with my corrupt, westernised ideas,” Chris says, “to people saying [I] had no right to appropriate [their] experiences for [my] own benefit and I must immediately stop work. Some emails and comments consisted of just four-letter words.” There were threats of beatings and sexual assault. One message made the threat of a group “coming to my house in the middle of the night, and breaking in so that they could give me a lethal overdose”. Some messages came through Goodreads, although Chris does not know if they were linked to the main YA community. The “vast majority”, and all of the most violent threats, “came from an ideology that I would identify as left”, Chris says, and every message made the same demand. “Stop writing this. Don’t write this. You can’t write this. You’re not allowed … ”

Reading stuff like this is truly disheartening, and I think a reminder that we should all stop and search our souls once in a while. Because being ‘on the right side’ doesn’t make you right all the time. And when I see what’s going with a fringe of the US left, and how it’s slowly spreading to Europe, I’m genuinely pissed off and afraid. I do not want to be caught in the middle between a right-wing that’s becoming completely demented and - whatever this is. We should make our voice heard before it’s too late.

#young adult#publishing#books#culture#ya#cancel culture#cultural appropriation#sjw#writers problems#this is a nightmare#every day i see some extreme idea on tumblr#presented as empathy and common sense#then you rant to people offline#they tell you it's the internet#but it's not#there's scary things going on#irl as well#and europe's not immune#uuuugh#old woman yells at cloud

590 notes

·

View notes

Text

55 BOOKISH QUESTIONS (THAT YOU LIKELY DON’T CARE ABOUT)

I found this questionnaire here

1. Favorite childhood book: Hmmm I didn’t read much when i was a kid. But I’d have to say i loved the Magic Tree House series. That series was amazing when i was a kid.

2. What are you reading right now? I just started Incubus Dreams by Laurel K. Hamilton. But i just finished reading Kiki’s delivery service.

3. What books do you have on request at the library? To Sleep in a sea if stars by Christopher Paolini. Sadly i have to wait eight weeks before i can get it. *sad face*

4. Bad book habit: Hmmm I’d guess i’d have to say that sometimes i check out too many ebooks from the library and sometimes never get to them. Oops.

5. What do you currently have checked out at the library? Nothing. I haven’t been able to go to the library.

6. Do you have an e-reader? No. I want one and will get one eventually but for now i use my ipad.

7. Do you prefer to read one book at a time, or several at once? I usually read about one or two books at a time. It really just depends on my reading mood.

8. Have your reading habits changed since starting a blog? No not really. I still read a majority adult fantasy.

9.Least favorite book you read this year: I’d say Storm Front by Jim Butcher. I just really didn’t like it.

10. Favorite book I’ve read this year: The Laughing Corpse by Laurel K. Hamilton. It was so cool.

11. How often do you read out of your comfort zone? Not very often. Just because most of the time i read out of my comfort zone i end up not enjoying what i’m reading. But recently I started reading some science fiction and i might be getting into this genre.

12. What is your reading comfort zone? Fantasy in general but more adult fantasy. :)

13. Can you read on the bus? I don’t normally take a bus so...no. lol

14. Favorite place to read? My bed or outside under my big maple tree.

15. What’s your policy on book lending? No one but two people are allowed to borrow my books. But they don’t get to borrow my favorites. I’ve had too many bad experiences with people borrowing them.

16. Do you dogear your books? Occasionally if i don’t have a bookmark but normally i use a bookmark.

17. Do you write notes in the margins of your books? No

18. Do you break/crack the spine of your books? only massmarket paperbacks. I find them so hard to read.

19. What is your favorite language to read? Umm English. I am learning french right now so eventually i would love to read in french.

20. What makes you love a book? The Characters and the plot.

21. What will inspire you to recommend a book? If I loved it and think the appeal extends to the person or group of people I’m recommending it to.

22. Favorite genre: Adult Fantasy.

23. Genre you rarely read (but wish you did): General Fiction. A lot of the plots sound interesting but i just have a hard time getting into them.

24. Favorite Biography: None lol

25. Have you ever read a self-help book? (And, was it actually helpful?) I had to for school in 9th grade. It was so boring.

26. Favorite Cookbook: Do restaurant menus count? They should really count.

27. Most inspirational book you’ve read this year (fiction or non-fiction): I really don’t know honestly.

28. Favorite reading snack: Pretzels and Soda or peperoni slices.

29. Name a case in which hype ruined your reading experience: The Bridge Kingdom. I was expecting too much from it.

30. How often do you agree with the critics about about a book? I’ve never really payed attention.

31. How do you feel about giving bad/negative reviews? I feel bad, especially when it’s a book i really didn’t like. But at the same time ba reviews do come with the territory of publishing or releasing art.

32. If you could read in a foreign language, which language would you choose? French.

33. Most intimidating book I’ve read: I really don’t get intimidated by books.

34. Most intimidating book I’m too nervous to begin: I don’t really have one.

35. Favorite Poet: Emily Dickinson i guess. I really don’t read poetry

36. How many books do you usually have checked out from the library at any given time? 1-10 books.

37. How often do you return books to the library unread? Sometimes but not as often as i used to.

38. Favorite fictional character: Rhysand. That man is just amazing.

39. Favorite fictional villain: Eric from True Blood series. Eric is so amazing. Granted he’s not fully a bad guy but mostly he is.

40. Books I’m most likely to bring on vacation: Romance. I enjoy a good fluffy romance when i’m on vacation. Or i will read a easy fantasy book.

41. The longest I’ve gone without reading: Well 6 months since i started my reading journey 12 years ago.

42. Name a book you could/would not finish: Crazy Rich Asians. I couldn’t deal with the characters or the writing. Ugh.

43. What distracts you easily when you’re reading? Loud Noises or the TV.

44. Favorite film adaptation of a novel: Lord of the Rings. It’s one of the best adaptations movie made.

45. Most disappointing film adaptation: Hmm i don’t know.

46. Most money I’ve ever spent in a bookstore at one time: $86.

47. How often do you skim a book before reading it? Never.

48. What would cause you to stop reading a book halfway through? if i just can’t stand the characters or the writing any more.

49. Do you like to keep your books organized? Kind of. I keep the authors together & series together. Also my favorites stay together.

50. Do you prefer to keep books or give them away once they’ve been read? I keep the ones i liked or loved but i chuck the ones i didn’t like.

51. Are there any books that you’ve been avoiding? hmm not really

52. Name a book that made you angry: The Girl in 6E. I couldn’t stand that book.

53. A book I didn’t expect to like but did: Eragon by christopher paolini. It was a book that really surprised me.

54. A book I expected to like but didn’t? From Here to Eternity by Catlin Doughty. I really loved her first book. But this one was just not my cup of tea.

55. Favourite guilt-free guilty pleasure reading: I don’t get the whole guilty pleasure thing. You like what you like and thats that.

Okay thats it ya’ll. Tag me if you do this tag. See you in my next post. :D

My Goodreads page

1 note

·

View note

Note

hello! you said in one of your videos (I think) that in order to write it’s important to read, but I can’t seem to be able to fit reading in my schedule (as in other than fanfic) so I’m wondering how you do it and what your goals are weekly/monthly/yearly. can’t wait to finish Narcissus btw! xx

HELLO!!! honestly it would be really hard for me to find time to read at all if i wasn’t an english major. i’d say about 75% of the books and short stories that i read this year were for one class or another, and the rest i read over the summer or during smaller breaks from school.

i don’t know what your situation/schedule is like, but no matter what i think the key is routine. if you schedule a daily block in your day ahead of time you no longer have to find time — it’s already there. making a habit doesn’t take very long, so it’ll get easier and easier to just do it without thinking as time goes on. and start with small goals! it’ll be easy to commit, for example, to reading for just fifteen minutes before bed every night. anothering thing to keep in mind is to always set goals based on time reading and not number of pages read! you’ll be surprised by how much material you’ll get through with just fifteen minutes a night.

and don’t be afraid to change up how you’re reading! audiobooks are great and though a lot of them are expensive, if a book is in the public domain you’ll find an audiobook of it on youtube or spotify! i personally am not a fan of audiobooks (i have a predominantly visual/photographic memory — i recall stories by remembering how the pages looked so i don’t retain stories as well if i’m only listening) but i’ll often play one while reading along. i did this for about ten shakespeare plays this year (because shakespeare is meant to be heard, not read, dammit) and am currently listening to little women before bed (because i’ve read it so many times already).

once reading is part of your daily routine, you can increase your time spent reading by reading whenever you have a spare moment. i read a lot this year in between classes, whenever i didn’t have friends to eat with at the dining hall, whenever i had free time at work, and while on the train. this is made even easier if you are able to carry your book with you everywhere, so i’d recommend either reading paperbacks whenever possible or on your phone/laptop.

in short, just remember that slow and steady wins the race! reading is not a competition or a matter of page count. this is why i detest yearly reading goals based on number of books read (like the goodreads challenges). i’d much rather you focus on rewarding yourself for reading every day rather than achieving a certain number of books read. ALSO it is always more important to read things that you enjoy rather than things that will make reading a chore in any way for you. since i read a lot of *intellectual* material for school, i read exclusively fun books for enjoyment.

anyway, happy reading! also thanks for reading narcissus! i’m so happy that i actually finished writing it this year rather than letting it go on as an unfininished work forever.

here are some of my favorite things i read in 2019:

the poppy war by rf kuang, nobody is ever missing by catherine lacey, the fourth state of matter by jo ann beard (commonly known as one of the best creative non fiction essays in existence), lavinia by ursula k le guin, my body is a book of rules by elissa washuta, severance by ling ma, wonder woman grew up in nebraska by sarah gerkensmeyer, reeling for the empire by karen russel, a midsummer night’s dream by shakespeare, notes of a native son by james baldwin, selections from the iliad by homer (translated by caroline alexander), the odyssey by homer (translated by emily wilson), and the song of achilles by madeline miller.

also i’m currently reading a memory called empire by arkady martine and loving it! and soon i want to start reading the witcher book series because i loved the show.

anyway i hope this answer was helpful to you. happy reading!! (and come back when you’re done with narcissus — i’d love to hear your thoughts!)

1 note

·

View note

Text

What I Learned From Reading a Book(ish) a Day

I have been in university for the past four years of my life in a very draining English degree. You might think this would have made me want to read, but, in fact, it had the exact opposite effect. I was drowning in required readings. So much so that in one of my seminar classes I had to read 12 novels. Yes. 12! And that was only 1 of my 5 courses! So of course I read as much as I could (and cheated with the help of sparks notes how could I not? just so I would be able to keep my head above water. Sure I learned a thing or two, and found fantastic books along the way, but this left me severely unsatisfied. Why? Because none of this was reading for fun.

During my first winter break in first year I read 5 books in the span of 3 weeks. I was so consumed by school work that reading for pleasure became my release. When school started again, so did the reading, but for education instead of fun.

Now I jump to today. At the beginning of April I submitted my last undergraduate assignment, thus ending my reading for pain. Similarly to what happened after my first semester of university, I read. And I read and read until I almost hit a slump.

It may have been my depression keeping me in bed, but I still read. From my last submitted assignment to today as I sit here writing this post, I have read about 12 books. For someone who only keeps her Goodreads goal at 35 it’s a lot.

So what did I learn from this? I learned that my love of reading may have laid dormant for the past 4 years, but it certainly didn’t die like I feared it would (and as many past English majors told me it would).

So now as I prepare to embark on my masters in publishing I hope that I can keep this newly reignited passion for reading going... or at least I’ll try.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s been a whole year since I posted last. Part of me wants to apologise for being gone so long, but mostly I’m just glad that I’m here.

Instead of doing a GIANT 2018 READING POST, I’m going to chop it up into three posts:

Favourite Books Read in 2018

2018 Reading Data and Goal-setting for 2019

2013-2018 Reading Data Trends

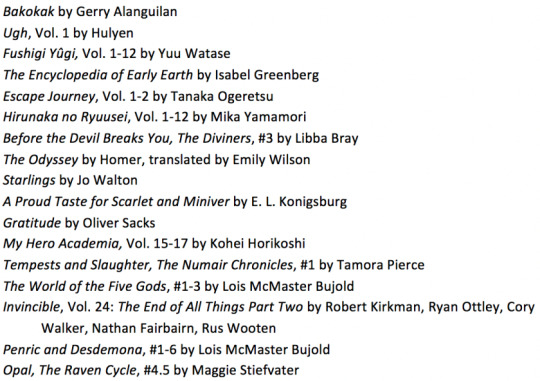

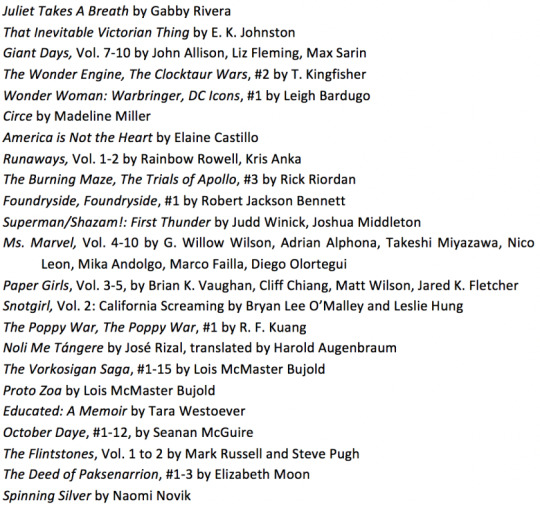

I was going to do a bigass one like I usually do but it just felt so daunting. Probably because I read 256 books in 2018 and it was pretty tempting to just close that Excel sheet and move on to an empty one for 2019. But what is the point of an unexamined life, anyway?

So this post is basically a listicle with summaries grabbed from Goodreads, as well as the complete list of the books I read in 2018. I really enjoyed all these books immensely and they’re all in my personal canon now.

My Top 10 Reads for 2018:

The Odyssey by Homer, translated by Emily Wilson

The first great adventure story in the Western canon, The Odyssey is a poem about violence and the aftermath of war; about wealth, poverty, and power; about marriage and family; about travelers, hospitality, and the yearning for home.In this fresh, authoritative version—the first English translation of The Odyssey by a woman—this stirring tale of shipwrecks, monsters, and magic comes alive in an entirely new way. Written in iambic pentameter verse and a vivid, contemporary idiom, this engrossing translation matches the number of lines in the Greek original, thus striding at Homer’s sprightly pace and singing with a voice that echoes Homer’s music.

Circe by Madeline Miller

In the house of Helios, god of the sun and mightiest of the Titans, a daughter is born. But Circe is a strange child—not powerful, like her father, nor viciously alluring like her mother. Turning to the world of mortals for companionship, she discovers that she does possess power—the power of witchcraft, which can transform rivals into monsters and menace the gods themselves.Threatened, Zeus banishes her to a deserted island, where she hones her occult craft, tames wild beasts and crosses paths with many of the most famous figures in all of mythology, including the Minotaur, Daedalus and his doomed son Icarus, the murderous Medea, and, of course, wily Odysseus.But there is danger, too, for a woman who stands alone, and Circe unwittingly draws the wrath of both men and gods, ultimately finding herself pitted against one of the most terrifying and vengeful of the Olympians. To protect what she loves most, Circe must summon all her strength and choose, once and for all, whether she belongs with the gods she is born from, or the mortals she has come to love.

3. The World of the Five Gods by Lois McMaster Bujold

A man broken in body and spirit, Cazaril, has returned to the noble household he once served as page, and is named, to his great surprise, as the secretary-tutor to the beautiful, strong-willed sister of the impetuous boy who is next in line to rule.

It is an assignment Cazaril dreads, for it will ultimately lead him to the place he fears most, the royal court of Cardegoss, where the powerful enemies, who once placed him in chains, now occupy lofty positions. In addition to the traitorous intrigues of villains, Cazaril and the Royesse Iselle, are faced with a sinister curse that hangs like a sword over the entire blighted House of Chalion and all who stand in their circle. Only by employing the darkest, most forbidden of magics, can Cazaril hope to protect his royal charge—an act that will mark the loyal, damaged servant as a tool of the miraculous, and trap him, flesh and soul, in a maze of demonic paradox, damnation, and death

4. Noli Me Tangere by Jose Rizal, Translated by Harold Augenbraum

In more than a century since its appearance, José Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere has become widely known as the great novel of the Philippines. A passionate love story set against the ugly political backdrop of repression, torture, and murder, “The Noli,” as it is called in the Philippines, was the first major artistic manifestation of Asian resistance to European colonialism, and Rizal became a guiding conscience—and martyr—for the revolution that would subsequently rise up in the Spanish province.

5. America is Not The Heart by Elaine Castillo

Three generations of women from one immigrant family trying to reconcile the home they left behind with the life they’re building in America.

How many lives can one person lead in a single lifetime? When Hero de Vera arrives in America, disowned by her parents in the Philippines, she’s already on her third. Her uncle, Pol, who has offered her a fresh start and a place to stay in the Bay Area, knows not to ask about her past. And his younger wife, Paz, has learned enough about the might and secrecy of the De Vera family to keep her head down. Only their daughter Roni asks Hero why her hands seem to constantly ache.

Illuminating the violent political history of the Philippines in the 1980s and 1990s and the insular immigrant communities that spring up in the suburban United States with an uncanny ear for the unspoken intimacies and pain that get buried by the duties of everyday life and family ritual, Castillo delivers a powerful, increasingly relevant novel about the promise of the American dream and the unshakable power of the past. In a voice as immediate and startling as those of Junot Diaz and NoViolet Bulawayo, America Is Not the Heart is a sprawling, soulful telenovela of a debut novel. With exuberance, muscularity, and tenderness, here is a family saga; an origin story; a romance; a narrative of two nations and the people who leave home to grasp at another, sometimes turning back.

6. The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk W. Johnson

A rollicking true-crime adventure and a thought-provoking exploration of the human drive to possess natural beauty for readers of The Stranger in the Woods, The Lost City of Z, and The Orchid Thief.

On a cool June evening in 2009, after performing a concert at London’s Royal Academy of Music, twenty-year-old American flautist Edwin Rist boarded a train for a suburban outpost of the British Museum of Natural History. Home to one of the largest ornithological collections in the world, the Tring museum was full of rare bird specimens whose gorgeous feathers were worth staggering amounts of money to the men who shared Edwin’s obsession: the Victorian art of salmon fly-tying. Once inside the museum, the champion fly-tier grabbed hundreds of bird skins–some collected 150 years earlier by a contemporary of Darwin’s, Alfred Russel Wallace, who’d risked everything to gather them–and escaped into the darkness.

Two years later, Kirk Wallace Johnson was waist high in a river in northern New Mexico when his fly-fishing guide told him about the heist. He was soon consumed by the strange case of the feather thief. What would possess a person to steal dead birds? Had Edwin paid the price for his crime? What became of the missing skins? In his search for answers, Johnson was catapulted into a years-long, worldwide investigation. The gripping story of a bizarre and shocking crime, and one man’s relentless pursuit of justice, The Feather Thief is also a fascinating exploration of obsession, and man’s destructive instinct to harvest the beauty of nature.

7. Educated: A Memoir by Tara Westover

An unforgettable memoir in the tradition of The Glass Castle about a young girl who, kept out of school, leaves her survivalist family and goes on to earn a PhD from Cambridge University

Tara Westover was 17 the first time she set foot in a classroom. Born to survivalists in the mountains of Idaho, she prepared for the end of the world by stockpiling home-canned peaches and sleeping with her “head-for-the-hills bag”. In the summer she stewed herbs for her mother, a midwife and healer, and in the winter she salvaged in her father’s junkyard.

Her father forbade hospitals, so Tara never saw a doctor or nurse. Gashes and concussions, even burns from explosions, were all treated at home with herbalism. The family was so isolated from mainstream society that there was no one to ensure the children received an education and no one to intervene when one of Tara’s older brothers became violent.

Then, lacking any formal education, Tara began to educate herself. She taught herself enough mathematics and grammar to be admitted to Brigham Young University, where she studied history, learning for the first time about important world events like the Holocaust and the civil rights movement. Her quest for knowledge transformed her, taking her over oceans and across continents, to Harvard and to Cambridge. Only then would she wonder if she’d traveled too far, if there was still a way home.

Educated is an account of the struggle for self-invention. It is a tale of fierce family loyalty and of the grief that comes with severing the closest of ties. With the acute insight that distinguishes all great writers, Westover has crafted a universal coming-of-age story that gets to the heart of what an education is and what it offers: the perspective to see one’s life through new eyes and the will to change it.

8. The Wicked + The Divine, Vol. 7 and 8 by Kieron Gillen, Stephanie Hans, André Lima Araújo, Matt Wilson, Kris Anka, Jen Bartel

In the past: awful stuff. In the present: awful stuff. But, increasingly, answers.

Modernist poets trapped in an Agatha Christie Murder Mystery. The Romantics gathering in Lake Geneva to resurrect the dead. What really happened during the fall of Rome. The Lucifer who was a nun, hearing Ananke’s Black Death confession. As we approach the end, we start to see the full picture. Also includes the delights of the WicDiv Christmas Annual and the Comedy special.

9. Mister Miracle by Tom King and Mitch Gerads

Mister Miracle is magical, dark, intimate and unlike anything you’ve read before.

Scott Free is the greatest escape artist who ever lived. So great, he escaped Granny Goodness’ gruesome orphanage and the dangers of Apokolips to travel across galaxies and set up a new life on Earth with his wife, Big Barda. Using the stage alter ego of Mister Miracle, he has made quite a career for himself showing off his acrobatic escape techniques. He even caught the attention of the Justice League, who has counted him among its ranks.

You might say Scott Free has everything–so why isn’t it enough? Mister Miracle has mastered every illusion, achieved every stunt, pulled off every trick–except one. He has never escaped death. Is it even possible? Our hero is going to have to kill himself if he wants to find out.

10. The Band, #1–2

Clay Cooper and his band were once the best of the best — the meanest, dirtiest, most feared crew of mercenaries this side of the Heartwyld.

Their glory days long past, the mercs have grown apart and grown old, fat, drunk – or a combination of the three. Then an ex-bandmate turns up at Clay’s door with a plea for help. His daughter Rose is trapped in a city besieged by an enemy one hundred thousand strong and hungry for blood. Rescuing Rose is the kind of mission that only the very brave or the very stupid would sign up for.

It’s time to get the band back together for one last tour across the Wyld.

PHEW. Did you guys read any of those books? Did you like them? Hit me up!

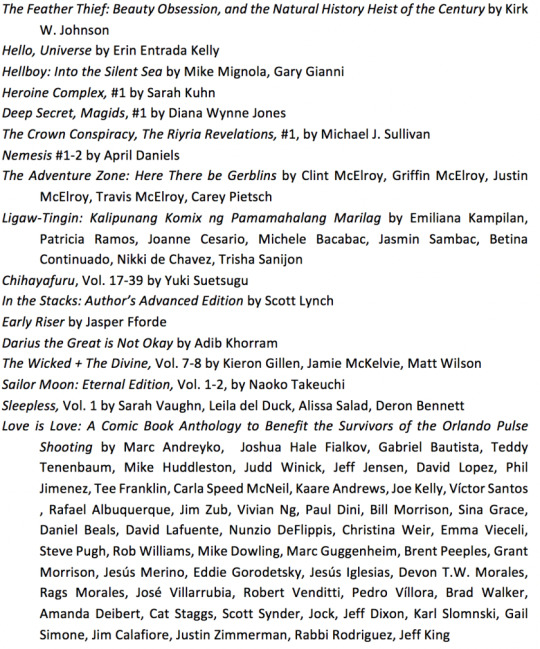

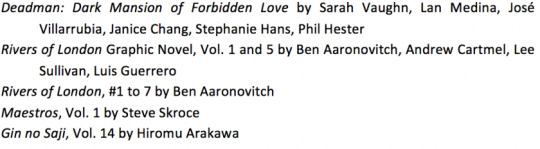

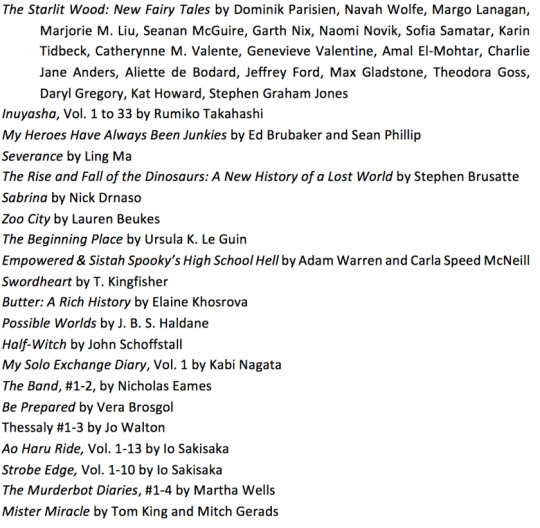

The books I read in 2018:

Okay, thank you for reading. Keep a weather eye out for the next post, hopefully very soon.

My Ten Favourite Books from 2018 It's been a whole year since I posted last. Part of me wants to apologise for being gone so long, but mostly I'm just glad that I'm here.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

REVIEW-The Sweetest Fix by Tessa Bailey ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 5 STARS

The Sweetest Fix is the delicious story of a dancer, taking her chance in New York City, and the grumpy baker she meets under less than honest circumstances. Leo wants nothing more than to be left to his baking, something that fulfills his need to care for others. He has dreams of expanding, but needs a push to make them happen. That push comes from Reese, the woman that dances her way into his life and opens his eyes to possibilities. I'll say now that while I loved Leo and his dirty-talking ways, Reese is the absolute star of this book. She's got dreams and, despite a few moments of self-doubt, she is determined to create the life she wants to live. Her excitement at being in New York came alive on the page, and I adored that Leo was happy to bask in her joy. The gift Leo sent to Reese while they were apart is one of the best things I've ever read in a romance novel. Also, nap dates are the best idea ever! Major swoon and lots of happy tears! If you're looking for a sweet treat, with a side of sexy, the The Sweetest Fix is sure to hit the spot!

Excerpt:

Leo stuck his hands in his pockets and sauntered toward her, taking a spot beside her at the edge of the roof. “So. You’re a long way from home. How long have you been in the city?”

Her smile wavered, the reminder of her lies of omission twisting bolts on the sides of her throat. “Oh, not long.” She turned and propped her arms on the wall, looking out over the city blocks. “I wish my mother could see this.”

“You said she owns a dancing school. Was she your teacher?”

“When I was little, yes. Around age ten, she thought I needed something a little more advanced.” She gave him a prim look. “It paid off, too, don’t you know? You might remember me from a certain national Red Rover Yogurt commercial.”

He turned slightly, squinting an eye at her. “Wait a minute. No way.”

Reese pushed off the wall and performed the soft shoe routine she’d done thousands of times—mostly as a party trick—since the age of eleven. “No preservatives or chemicals, we’ve got your all-natural meals,” she sang, “Choose Red Rover products and kick up your heels.”

“Holy shit.” He stared at her, dumbfounded. “The audacity of me to ask out a celebrity.”

“Please.” She fluffed her hair. “I put my pants on one leg at a time like everyone else.”

They seemed to gravitate toward each other naturally, as if there was no other option, until their faces were a handful of inches apart. “How about those shorts?” he said gruffly. “You get those on the same way?”

A hot, fizzy stream of awareness circled and danced in her midsection. This was flirting. But not the kind she was used to. Where she worried about every line out of her mouth, worrying they would come across too desperate. Or if the guy would think she was funny. No, it was easy as breathing to pull back the edge of her coat, drawing his attention downward. “What? These old things?”

“Yeah.” A muscle ticked in his cheek. “Those.”

She leaned in like they were sharing a secret and watched his eyes darken. “I have to wiggle around a little to get these on.”

They exhaled into each other’s space, not bothering to hide the fact that both of them were breathing faster. “Damn, Reese.”

There was a wealth of meaning in those two words. Not just, damn, you look good in those shorts. But damn, this attraction between them was not typical. “I know,” she said in a rush, their mouths almost touching. She wasn’t sure what made her pull away before he could close the distance for a kiss. Maybe it was to gather her wits or a tug from her conscience. But she took a long pull of February air to perform maintenance on her short-circuiting brain. “So, um…” She resisted the urge to fan herself. “How long have you owned the bakery?”

With his own centering breath, Leo slowly settled back in a safe distance away. “Four years,” he said, voice gravelly. “Took me a while after culinary school to build the capital and find the right people. The right place. Didn’t want to rush it.”

“Capital?” Her question hung in the air for several seconds before she realized what a stupid assumption she’d made. “Forget I said that. I just…I thought with your father being who he is…”

“That I would have an automatic investor?” He shrugged a shoulder. “Natural to assume that. Don’t worry about it.” There was an assessing glance in her direction, as if he wasn’t sure whether to say more. She held her breath, hoping he would. “I guess it didn’t feel right taking money for something he doesn’t have a real interest in. Baking. I’m not saying he’s unsupportive. We’re just about different things. Felt better doing it on my own.”

“That’s admirable.” She wanted to tell him how much she could relate. Currently. Trying to grasp something that felt just within reach, refusing any shortcuts. How it could feel scary and unfair one minute, rewarding the next. “And I guess you found the right people. Jackie and Tad.”

Warmth moved in his expression. “Yeah. Tad was actually an usher downstairs when I met him. We interviewed Jackie together. She’d just dropped out of nursing school because the emotional toll was more than she expected.”

“So she went for the exact opposite.”

“Only for a while. I doubt she’ll be at the Cookie Jar forever. But I’ll be glad to have her as long as she puts up with my grumpy ass.”

“You’re not coming across as grumpy as you did Saturday night.”

“That’s because I’m trying to charm you into going out with me. Is it working?”

Her laugh drifted out over the rooftops. “Maybe. How long until the grump returns?”

“I skipped lunch. So…imminently.”

Download your copy today or read FREE in Kindle Unlimited!

Amazon: https://amzn.to/3qLixkj

Amazon Worldwide: http://mybook.to/SweetestFix

Amazon Paperback: https://amzn.to/3qQ9OO3

Add The Sweetest Fix to Goodreads: http://bit.ly/3qMG0la

ABOUT TESSA:

Tessa Bailey is originally from Carlsbad, California. The day after high school graduation, she packed her yearbook, ripped jeans and laptop, driving cross-country to New York City in under four days.

Her most valuable life experiences were learned thereafter while waitressing at K-Dees, a Manhattan pub owned by her uncle. Inside those four walls, she met her husband, best friend and discovered the magic of classic rock, managing to put herself through Kingsborough Community College and the English program at Pace University at the same time. Several stunted attempts to enter the workforce as a journalist followed, but romance writing continued to demand her attention.

She now lives in Long Island, New York with her husband of eleven years and seven-year-old daughter. Although she is severely sleep-deprived, she is incredibly happy to be living her dream of writing about people falling in love.

Contact Tessa

Website: https://www.tessabailey.com

Facebook: http://bit.ly/2sScu5g

Instagram: http://bit.ly/36pRws6

Amazon Author Page: https://amzn.to/2NSjQgA

Goodreads: http://bit.ly/37nMrSB

Join her Reader Group: http://bit.ly/2uoDGZP

Stay up to date with Tessa Bailey by joining her mailing list: http://bit.ly/36j2TCl

0 notes

Photo

Where Are Our Black Boys on Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy Novel Covers?

Why are there no boys like me on these covers?

My seventeen-year-old brother who lives in Lagos, Nigeria, raised this question to me recently. Not in these exact words, but sufficiently close. I’d been feeding him a steady drip of young adult (YA) science fiction and fantasy (SFF) novels from as diverse a list as I could, featuring titles like Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti, Martha Wells’ Murderbot series, Roshani Chokshi’s The Star-Touched Queen and Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother. The question, at first seemed like a throwaway one, but as my head-scratching went on, I realised I did not have a clear-cut answer for it.

His question wasn’t why there were no black boys like him in the stories, because there definitely were. I guess he wanted to know, like I now do, why those boys were good enough to grace the pages inside but were somehow not good enough for the covers. And because I felt bad about the half-assed response I offered, I decided to see if I could find a better one.

So, I put out a twitter call for recommendations.

Can anyone point me to science fiction & fantasy novels with black teenage boys on the cover? Asking for my teenage brother. I know there's Tristan Strong, & books from Victor LaValle & Colson Whitehead, but I need more. Most YA I see with black boys are contemporary lit.

— Suyi on hiatus. (@IAmSuyiDavies) May 6, 2020

The responses came thick and fast, revealing a lot. I’m not sure I left with a satisfactory answer, but I sure left with a better understanding of the situation. Before I can explain that, though, we must first understand the what of the question, and why we need to be asking it in the first place.

Unpacking the Specifics

My intent is to engage with one question: How come there are few black boys on young adult science fiction and fantasy novel covers? This question has specific parameters:

black: of Black African descent to whatever degree and racially presented as such;

boys: specifically male-presenting (because this is an image afterall), separate from female-presenting folks, and separate from folks presenting as non-binary, all regardless of cisgender or transgender status;

are displayed prominently on covers: not silhouetted, not hinted at, not “they could be black if you turned the book sideways,” but undeniably front-of-cover blackity-black;

YA: books specifically written for young adults (readers aged 12-18), separate from middle-grade (readers 8-12) and adult (readers 18+);

SFF: science fiction and fantasy, but really shorthand for all speculative fiction and everything that falls under it, from horror to fabulism to alternative history;

novels: specifically one-story, book-length, words-only literature, separate from collections/anthologies or illustrated/graphic works (a novella may qualify, for instance)

I’m sure if we altered any of these criteria, we might find some respite. Contemporary YA and literary fiction with teenage protagonists, for instance, are littered with a relatively decent number of black boys on the covers (though many revolve around violence, pain and trauma). Young women across the people-of-colour spectrum are beginning to appear more often on SFF covers too (just take a look at this Goodreads list of Speculative Fiction by Authors of Color). Black boys also pop up on covers of graphic novels here and there (Miles Morales is a good example). But if we insist on these parameters, we discover something: a hole.

It is this gaping black hole (pardon the pun) that I hope to fill with some answers.

The Case for Need

Think about shopping at a bookstore. Your eyes run over a bunch of titles, and something draws you in to pick one–cover design, title, author, blurb. You’d agree that one of the biggest draws, especially for teens to whom YA SFF novels are aimed, is the character representation on the cover (if there’s one). Scholastic’s 7th Edition Kids & Family Reading Report notes that 76% of kids and teens report they’d like characters who are “similar to me,” and 95% of parents agree that these characters can help “foster the qualities they value for their children.” If the cover imagery, which is the first point of contact for this deduction, is not representative of the self, there’s an argument to be made that reader confidence in the characters’ ability to represent their interests would be significantly reduced.

The why of the question is therefore simple: when a group already underrepresented in literature and readership (read: black boys, since it’s still believed that black boys don’t read) are also visually underrepresented within their age group and preferred genre (read: YA SFF), it inadvertently sends a message to any black boy who loves to read SFF: you don’t fit here.

This is not to say that YA is not making strides to increase representation within its ranks. Publisher’s Weekly’s most recent study of the YA market notes various progressive strides, touching base with senior publishing professionals at teen imprints in major houses, who say today’s YA books “reflect a more realistic range of experiences.” Many of them credit the work of We Need Diverse Books, #DVPit, #OwnVoices and other organizations and movements as pacesetters for this growing trend.

In the same breath, though, these soundbites are cautiously optimistic, noting that the industry must look inward for underlying reasons why easy defaults remain commonplace. Lee&Low’s recent Diversity in Publishing 2019 study’s answer to why unquestioned go-tos still reign supreme is that the industry remains, sadly, 76% Caucasian. For a genre-readership with such exponential success, that makes the hole a massive one. Of the Top 10 Best Selling Books of the 21st Century, four are YA SFF franchises by Rowling, Collins, Meyer, and Roth, the most among all listed genres. In 2018’s first half, YA SFF vastly outsold every other genre, amassing over a quarter of an $80-million sales total. This doesn’t even include TV and film rights.

I once was a black boy (in some ways, I still am). If such a ubiquitous, desired, popular (and don’t forget, profitable) genre-readership somehow concluded a face like mine on its covers was a no-go, I’d want to know why too.

Navigating the Labyrinth

Most of the responses I received fell into three categories: hits & misses, rationale, and outlook. Hits & misses were those who attempted to recommend books that met the criteria. If I had to put a number to it, I’d say there were around 10+ misses to one hit. I received many recommendations that didn’t fit: middle-grade novels, graphic novels, covers where the blackness of the boy was up for debate, novels featuring black boys who were not present on the cover, etc.

The hits were really great to see, though. Opposite of Always by Justin A. Reynolds was the crowd favourite of the recent recommended titles. The Coyote Kings of the Space-Age Bachelor Pad by Minister Faust was the oldest recommended title (2004). One non-English title on offer was Babel Corp, Tome 01: Genesis 11 by Scott Reintgen (translated to French by Guillaume Fournier, published in the US as Nyxia). Non-print titles also showed up, like Wally Roux, Quantum Mechanic by Nick Carr (audio only). Lastly, some crossover titles like Miles Morales: Spider-Man by Jason Reynolds (MG/YA) and Temper by Nicky Drayden (YA/Adult) were present. You’ll find a full list of all recommendations at the end of this article.

Many of the hits were worrisome for other reasons, though. For instance, a good number are published under smaller presses, or self-published. Most are of limited availability. Put simply: a high percentage of all books recommended have severely limited wider industry coverage, which twanged a sour note in this orchestra.

The rationale group attempted to approach the matter from a factual angle. Points were made, for instance, that fewer men and nonbinary folks are published in YA SFF than women, and fewer black men even so, therefore representing black boys on covers may increase with more black male authors of YA SFF. While a noble thought, I do argue that various YA authors, regardless of race or gender, have written black boys as protagonists, yet those didn’t make the covers anyway. Would more black male authors suddenly change that?

Another rationale pointed toward YA marketing, which many stated mostly targets teenage girls because they are the biggest audience. I’m not sure how accurate this is, but I know sales often tell a different story from marketing (case in point: 2018 market estimates show that nearly 70% of all YA titles are purchased by adults aged 18-64, not teenage girls). If the sales tell a different story, yet marketing strategies insist upon a one-note approach, then it’s not really about the sales, is it?

Lastly, the outlook responses came mostly from readers, authors and publishing professionals who are long-time advocates of increased inclusion in publishing. The overwhelming consensus was that, while there is no complete absence of black boys on YA SFF covers, the real problem is the difficulty in pointing them out. It was agreed that it speaks volumes that we have to do this deep-dive just to find an okay amount of recommendations. Many left with a feel-good note, though, since more authors and professionals dedicated to inclusion and visibility are finally getting their feet into the doors at Big Publishing. Thanks to advocates like People of Color in Publishing and We Need Diverse Books, the future looks exciting.

So, I’ll end this on another feel-good note by offering an ongoing list of recommendations that fit the bill. You’ll find that most are absolutely worth a look-see. This list is also open for public updates, so feel free to add your own recommendations. And here’s looking to the decision-makers at Big Publishing to make this list even bigger.

+Black Boys on YA SFF Novel Covers: A List of Recommendations

#books#black literature#black lit#black children's books#children's books#black children#black boys#people of color in publishing#we need diverse books#tor#ya#sff#representation#publishing

0 notes

Text

radical eschatology and 1Q84

i wrote this as a goodreads review, but i couldn’t fit the whole text there so this is the review in its entirety.

“‘lunatic’ means to have your sanity temporarily seized by the luna, which is ‘moon’ in Latin. In nineteenth-century England, if you were a certified lunatic and you committed a crime, the severity of the crime would be reduced a notch. The idea was that the crime was not so much the responsibility of the person himself as that he was led astray by the moonlight. Believe it or not, laws like that actually existed… I learned it in an English literature course at Japan Women’s University, in a lecture on Dickens. We had an odd professor. He’d never talk about the story itself but go off on all sorts of tangents.”

I think a lot of my writing on this site consists of meandering tangents, only obliquely related to the book at hand — though less useful and interesting than this literature professor’s in 1Q84. Either way I will stick to what I’m comfortable with here. I will start with why I read this obscenely large book. My high school friend who was recently married, hosted a birthday party at a new place he moved into in Etobicoke. I arrived half-an-hour late from the time it was supposed to start (according to Facebook), and was the first one there — which is some indication of the sort of company I keep. As I awkwardly sat around after a brief house tour, he poured me a drink, and we chatted about life and my terrible job. He suddenly exclaimed, “Oh, I almost forgot. There’s something I want to lend to you.” He skips up the stairs and comes back down with a large phone book. On its front cover: a face hiding behind the characters “1Q84” — maybe embarrassed by its bloated constitution. This will help you on your daily commutes from hell, he encouraged me.

I’ve heard that your first Murakami book has a good chance of becoming your favourite Murakami book. That was probably the case for me with “Kafka on the Shore”. I think that book put me onto Kafka, before I would later encounter him in the work of Walter Benjamin, Judith Butler, and his late communist ‘wife’, Dora Diamant. But subsequent Murakami books were not as satisfying for me. After reading Norwegian Wood, I decided to try and take a break from Murakami. I had grown a little weary of the Oedipal themes, and Murakami’s recurring Manic Pixie Dream Girl tropes. Around this time, my fourth-year college roommate discovered Murakami for himself, and his first encounter was through 1Q84. He loved it, but what a book to start with, I had thought at the time. I was impressed that he ploughed right through such an enormous millstone of a novel. (I was very intimidated by its size when my friend handed it to me, but got through it in surprising time. Having now read 1Q84, I realize it was actually a very fun book to read, and often quite difficult to put down, so it now makes sense.) Anyways, I was discussing these things with my roommate and another law student who was camping with us at Sandbanks Provincial Park — she also shared similar thoughts as mine on Murakami. Conversation wandered on to Junot Diaz, who she was much more approving of — this of course was before the #MeToo revelations about Diaz. How quickly tides can turn. (Especially when there are two moons in the sky.)

So something about the structure of 1Q84. I am told the first two books are structured after the two books of Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier” — each chapter alternating between Aomame (major keys) and Tengo (minor keys). In each book of Clavier, Bach cycles through all twelve tones, a prelude and fugue for each tone’s major and minor keys. So each of Murakami’s chapters in Book 1 and 2 corresponds to a Prelude and Fugue in Bach’s collection of pieces — 48 chapters in all.

I admittedly have a thing for Bach. I have a copy of Gould’s “Well-Tempered Clavier” on compact disc at home. It came in a package of random shit the novelist Tao Lin gathered together from his bedroom and sold online for like $30 on eBay. That is the sort of stupid stuff I wasted my money on as an undergraduate student. Among the zines, postcard sized art prints, manuscript pages from his edits of Taipei, and a copy of “Shoplifting from American Apparel” was a disc of Gould’s “Well-Tempered Clavier”. In one of the preludes and fugues, the disc is scratched, and makes these heavenly wobbling sounds as it skips, and I have grown quite fond of these parts. I also particularly love hearing the infrequent muffled hums of Gould behind his gas mask.

Book 3 of 1Q84 is structured after Bach’s Goldberg Variations. In the past couple years, I’ve listened to this composition likely more than any other, simply because it’s one of the few albums I happened to have downloaded on my phone. It’s Igor Levit’s studio recording of the Goldberg Variations along with his recording of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations and Rzewski’s “The People United Will Never Be Defeated”. I thought it was a clever trio to package in an album. I also recommend Lisa Moore’s performance of other Rzewski compositions put out by Cantaloupe.

I am particularly fond of Rzewski’s “People United” because it recalls for me my first May Day march, where I chanted the Chilean song (from which Rzewski’s title is derived and his piece alludes to) with other people on the street marching on the way to Queen’s Park, while students shouted ‘ftp’ at officers lined on the sidewalk. I was supposed to march with a small contingent from Student Christian Movement, but couldn’t find them at Allan Gardens, so I marched near some York OPIRG students, and in front of a communist who was debating random people the entire march, haha. I had never seen so many anarchists and communists in one place at a time. They sure do like their black and red flags, haha.

This brings me to the next comment I wanted to make. I was curious about Murakami’s politics and I had a difficult time finding a decent write-up that focuses on this, because Murakami can come across as fairly apolitical, which I think is what his ‘bourgeois individualism’ (I use that term in jest) requires of him. Anyways, I stumbled across a series of blog posts made by a Trotskyist grad student that discuss how Japanese student movement comes up in almost every single novel by Murakami, and he discusses how the student movement was a significant segment of the political left in Japan during that time.

“Some brief highlights of the student movement’s history in Japan will suffice. After the end of the war, university students oriented to the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) took advantage of the new liberal atmosphere to rally for university autonomy, for the appointment of progressive faculty and administrators, and for a student voice in administration… In 1948, students from all over Japan inaugurated the All-Japan Federation of Student Self-Government Organizations (known by its acronym, Zengakuren) with a leadership largely from the Japanese Young Communist League… However the honeymoon between the students and the JCP was short-lived… The JCP had seen the American occupation as an opportunity to complete the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Japan, which had been the Moscow-ordained task of Communist Parties the world over during the Popular Front (1936-39) and then again after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, when Communists were allied with all “liberal,” “democratic,” and “peace-loving” forces, meaning those of the ruling class.