#rather than being artistic or literary or meaningful

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

everyone just needs to take a deep breath and accept the fact that some kind of "pulp fiction" has always existed, will always exist, does not inhibit the ability for "serious" stories to exist, and will almost never warrant pearl clutching about the end of xyz for media because of its popularity.

#and remember that its corporations you're actually mad at.#using pulp fiction as a catch all term for like cheap mass produced fiction that focuses on entertaining#rather than being artistic or literary or meaningful#but I feel like if you get the concept of pulp fiction as want it literally means#then you get what I'm talking about now#just expand it to like movies and shows and not just books

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Idle Conversations || Good Omens Ineffable Husbands

[Pre-Canon/Ambiguous in Timeline] [Angst] [Hurt No Comfort] [EXTREME Misunderstandings] [i'm so sorry]

In the little bookshop nestled on the corner two supernatural beings usually congregated. Fora various reasons- ranging from “how do I stop heaven from finding out I tempted that priest for you” to “I made a wonderful pound cake and insist you try it!”

Tonight however, was a strange third option. Tonight, an angel and a demon were lucidly drunk in the back room, speaking about any and everything that escaped their lips. Now Crowley, the dark man who adapted to any environment he needed to, playfully argued to Aziraphale, the cozy little angel that likes things to be rather comfortable. It infuriated Crowley to no end that Aziraphale was simply satisfied with a comfortable silence, while Crowley felt a vehement need for intake and indulgence. And to think that the discussion started over a movie that Aziraphale found interesting while Crowley found it pompous.

“Really, it’s not a problem with pretentious movies- if the guy behind its got a good record of making good high art movies, it’s the people I can’t stand who say they understand abstract art when the abstract is the art!” Crowley explained emphatically as he lazily took another sip of wine. Aziraphale nodded, his brow curled in minute frustration at how Crowly spectacularly missed his point completely.

“Well, not focusing on the audience, the movie is a wonderful example of artistic nihilism and a meaningful existentialism in a sense- now I know that’s rather oxymoronic to say, but I feel that the art of the so-called nonsensical is the sense of it all. After all, the meaning of the phrase “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.” is paradoxically beautiful and abstractly striking in a more than can be put into words.” Aziraphale rambled on, but Crowley had put a finger up to silence him as he opened his mouth to speak.

“Well, that’s why I decided I can’t watch movies that you’ve already seen with you anymore.” He nodded, finally speaking. Aziraphale had long taken the alcohol out of his body to better explain his love for the film, but the way Crowlay had said that struck the angel in a way he did not perhaps like. “It’s like I’m watching your reaction and attachments you’ve already formed to the characters and the movie rather than the movie itself- kinda ruins the whole “new” experience. Like with Pride n’ Prejudice. I listened to you waffle on about how much you loved Darcy’s character more than I watched the film!”

Now, surely Crowley had not meant it to come off so harsh sounding, and Aziraphale knew that intrinsically. Whenever Crowley had said something upsetting, it was usually out of ignorance rather than actual malice. This however, stung like nothing else before had.

“I show you the films I like to let you see..” Aziraphale had trailed off, his voice shutting quietly against his will. “I show you the films I like and the books I like to let you peek into what made me the angel I am today. It’s nice to have a comfortable monotony once in a while.”

Crowley shrugged. “That makes sense and all, but angel, where’s the excitement for the new? The reaching out for a never before felt experience? If you’re always stuck in the comfortable- what if something passes you by?” That was a rather silly question, Aziraphale thought. He had never let an opportunity pass simply because he was comfortable.

“It’s a sense of stability, for me personally.” Aziraphale retorted kindly. The ever so tightly lipped smile across his face hid back all the questions that raced in his mind. Was he really that boring to Crowley? Had he not cared for all the times Aziraphale had tried to open up to him through his beloved literary artworks? He had thought Crowley liked sitting with him and indulging in stories that were near and dear to him. “Heaven is very hectic, despite what it looks like.”

“Quite the opposite for us, really.” Crowley muttered disdainfully. “Every day down there is the same old same old.”

“Perhaps that’s why you prefer a faster paced lifestyle. It fulfills a different need for you, just as the comfortable stagnation fulfills a need for my life.”

“Yeah, but what’s the point of it all? The world’s still going to spin if you’re sitting in ye olde bookshop that never changes.” Crowley asked genuinely, another bottle empty and set by the chair. “I couldn’t manage myself if I just stuck to the same thing for centuries.”

“I suppose that’s the point, really. I like staying still and admiring the complex beauties of select things, while you are far better suited to a short-form consuming style of appreciation.”

Crowley made a noise of agreement. He had always liked to look up with the times. Humans always were so fast paced, after all. It’d be a shame to blink and miss something clever they did. That was something Crowley could never really understand about Aziraphale- why did he find it so fascinating to just sit idly by and perfect the tiny details of everything? As much as Crowley(to everyone else who saw him and Aziraphale together) was so brazenly smitten, his curiosity about Aziraphale’s tendencies always kept him around, even if it was just lingering for a few moments in-between thrills of adventure.

A tightness in Aziraphale’s chest and a puzzled furrow to his brow clued Crowley that something was up.

“Well, as much as I would love to continue this conversation, I really think we should be off. I have a new shipment of books I need to unpack. I was going to get to them before you had dropped by.”

Now Crowley knew something was definitely up. He did not want to press the angel about it in the state he was in currently, so a quick sobering up brought him to realize that something in the conversation had went grievously wrong. It was best not to try his luck in these types of situations he had learnt. With a quick goodbye and a lingering stare that perhaps looked a second too long, Crowley had excused himself back to his apartment. There Aziraphale sat, Crowley’s words echoing in his mind.

Was he boring to Crowley? Was he dull and long winded? Well, compared to Crowley, Aziraphale was certainly more hesitant to change. His life had always been far too hectic, what was wrong with wanting a little stability?

Aziraphale hesitated as he reached for a book.

Was he really limiting his horizons by staying stagnant?

Aziraphale’s hands placed themselves gently on his lap as he let out a long yet soft sigh. Should he bake? No, that was one of his many limited hobbies. He did not want to go out and try new things simply because Crowley implied that his palette was lacking. He would not succumb to a demon’s taunt- no matter how accidental it was.

But that was the worst part though, wasn’t it? That it had been so casually said. As if it was a common fact about Aziraphale that he liked to stop and observe a world that still spun despite him. “You go too fast for me, Crowley.”

#fanfiction#good omens#aziraphale x crowley#aziracrow#aziraphale#crowley#crowley x arizaphale#ao3#azicrow#anthony j crowley#good omens 2#ineffable divorce#ineffable husbands#ineffable idiots#im so sorry but also lmao get fucked#prettyboypistol#prettyboy pistol

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I miss academia only in the literary field tbh. Bc I always enjoyed reading and analysis but I kind of -need- to be prompted, I -need- other people to ask me things, bc otherwise I’m putting statements out there into the void unprompted vs whatever the spiritual successor is to your teacher handing you a sheet which says “what do you think this means” with the explicit understanding and willingness to offer you the grace your personal perspective on this author is going to be fucking limited, your intention to research them in their totality might be nonexistent. and this isn’t a moral defect, you just fucking want to read Something and talk about what you just read, 5 minutes ago. But you also aren’t seeking to be regarded as an expert, or someone who wants to read nonstop in perpetuity till you feel like you’ve learned Nothing, which is what I feel like a lot of people who read and discourse a lot about reading sometimes do.

Some people never stop they never pull back long enough to apply that knowledge to the present, which is why they exist in a sphere separate from normal people, who rightfully feel condescended to by this. Bc your basis and understanding of intelligence is “have you collected enough Information” to even be allowed to to perceive and form opinions on this isolated instance of what you’ve read. Instead it becomes a Sisyphyian task of further and further education which will lead you in circles and convince you that you can never know enough. Ergo you can never Be enough, to be worthy of stating your own opinions. Did you research the surrounding historical context? Have you read all of this authors works? Have you read the inspiring literature? Are you eager to provide in depth analysis and condemnation of this authors problematic opinions?

Wheras I want to sort of, beg to the importance and validity of sometimes having a limited perspective, and needing to clumsily navigate the learning process, rather than immediately being presumed one of 2 alternatives, an expert, or someone with no right to speak on a subject, period.

Can -you- the person who is more educated than me, summarize whatever makes this prolonged research and knowledge of the subject important, sustinctly, within reason, or are you presuming the need to engage with this thing in its entirety is necessarily meaningful to my capabilities as a human.

When engaging w someone less educated than you, on any subject, it’s your duty as the expert, within reason, Not to gatekeep people who are just passing through. I.e. when a non artist shows me a drawing, i do not critique them as someone who intends to spend 20+ years getting to the level of skill and understanding I am at, I speak to them as a person passively engaging with a hobby and praise them for their attempts, offering minimal advice if they are interested. Ask yourself. Are you actually keen on imparting this wisdom on others or are you just weaponizing it to make them feel stupid and morally deficient.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rise of ‘insta poetry’

The creative arts is a field that unfortunately, has never quite received the recognition it deserves. Few artists- like writers and painters- have ever been able to make a living out of their art, regardless of their skill level. Even legendary poets such as William Carlos Williams and Charles Bukowski had to take second jobs alongside writing their poetry to survive.

However, with the rise of ‘instagram poetry/insta-poetry,’ it’s become a main career for many people. Instapoetry, by definition, is a term used to describe poetry written with the intention of being posted on social media platforms, especially instagram. It has a distinct style when compared to the work of poets from the past, or even the poetry taught in schools.

One of the most notable poets who emerged using this style would be Rupi Kaur, author of ‘Milk & Honey.’ She began by posting her poems on tumblr back in 2012, switched to instagram, and eventually published her collection of poems as a book in 2014. By 2016, the book had made it onto the New York Times bestseller list, and her success continued to grow. The rise of Rupi Kaur helped the entire genre of poetry gain recognition once again; from an under-valued, under-appreciated art form to one that was in the front shelves of bookstores.

Since Rupi Kaur, more and more insta-poets have begun to enter the spotlight, including many celebrities who decided to branch out into poetry. Cleo Wade, Atticus, and R.M. Drake are just a few who have been successful. This style of poetry’s success is likely due to how accessible and understandable it is to most consumers. The poems are typically quite short, aesthetically-pleasing to look at with drawings to accompany them, and are usually blunt and not heavy on literary devices or techniques. It also has a proven history of encouraging more people to engage in writing poetry, helping it stay relevant and brought into the changing world. Further, it provides more room for experimentation and freedom than typical poetry, which makes it more appealing to the majority of the population.

However, there’s another side of people who hold a different viewpoint. It’s often argued that insta-poetry is an invalid style of poetry, and is rather leading to the death of true, authentic, and meaningful poetry. Some claim that it’s nothing but shallow, artificial, ‘shower-thought’ lines that don't require any analysis or interpretation, with the only method of conveying meaning being line breaks.They say it focuses more on looking aesthetic and pretty instead of holding any substance, which leads to the demise of good quality literature in the modern world. Rebecca Watts, a British poet, wrote an essay in which she criticized the craft of insta-poetry and some of the poets themselves, writing it off as ‘amateurish’ and something that solely propagates the culture of instant gratification.

According to them, the issue does not lie with enjoying insta poetry- the issue is what its success shows us about society. It shows us society’s addiction to simplicity, and their interest in things that do not require them to think or have background knowledge about a certain topic. It’s also a testament to the steadily decreasing attention spans of people- nobody has the patience or energy to read the work of someone like Robert Frost and analyze the meaning behind his writing. The work of poets such as Rupi Kaur is much more immediately relatable and understandable, due to its simplicity, and that’s what sells.

Further, most of these poets had no formal education regarding writing poetry. Those against it argue that people publishing works of poetry without having the proper knowledge are stripping the art form of its complexities, and making it seem like an easier task than it is. Writing is a learned, complicated craft, and many insta-poets are self-publishing collections of poetry as a side-job to their already famous profession. Simultaneously, many writers working on honing their skills and trying to publish poetry are hardly getting recognition, angering many supporters of poetry.

In conclusion, insta-poetry may be a new arrival, but it’s evidently one that’s staying. It’s a double-edged sword, and it’s up to us to choose which side to focus on.

#writing#nonfiction#article#essay#poetry#instapoet#literature#modern literature#modern poetry#social media#writers on tumblr

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regarding this post, and this somewhat-jokey in tone but fully serious in sentiment post from awhile back -

I cannot possibly express how worse than useless abstractions are, when it comes to determining the appeal of kink to me. Do I want to hurt someone? Do I want to submit to someone? Well, I don't fucking know! Where's the story? Where's the narrative? What are the motivations involved, and the specific contours of the interpersonal dynamic in question, that would give rise to this sort of interaction and make it erotic?

I remember stumbling across someone's tumblr awhile ago (around the time of the porn ban and the mourning of the loss of content) that was centered on a certain type of kink, and reading the posts I was kind of like "damn, this is boring? this is just the same conceit over and over with nameless, faceless figures that serve only as a conduit for this kink, but in a way that renders it absolutely meaningless, because I don't know anything about these people and why this scenario would appeal specifically to them." (More power to the person who ran that blog, but contextless erotica is not my deal.) But being introduced to this same kink in the context of a piece of media that I was already invested in, thematically and artistically and character-wise, made it suddenly come vividly into colour for me and made me realize, oh, I do understand the appeal of this now.

Like, I find kink easiest to engage with in a fandom context (or literary/media-based context, more generally) because it gives me a preexisting background to apply these abstractions to and make them make sense. And Hannibal in particular works so well for that because kink is woven so much into the fabric and artistic sensibility of the show, but not in a direct or surface level way, so there's a lot of room left for the viewer to extrapolate and tease it out in personally meaningful ways. And because the characters' motivations wrt violence and power are comparable but varied, it gives me a lot of possible "ins" in considering the appeal of this stuff to me.

In general, I get frustrated by common narratives about (or rather, defenses of) interest in kink that put a lot of emphasis on the early, instinctive appeal of certain positions/acts. Not because that's not true for many people, but because I feel it's limiting as a rhetorical approach, and because it doesn't match my experience. As with queer identity, I'm wary of framings that seek to locate inclination to deviate from the norm as a permanent, unchangeable quality of the self that is simply "named" and "recognized" by certain discursive frameworks, rather than something that can itself come into being and develop alongside epistemic growth. But I think I'm finally starting to feel less crazy about this.

#i'm turning off reblogs because holy damn this is some word salad#that i'm mainly writing just to write it#kink blogging#hannibal talk#fandom natterings#fandom as a means of exploring kink is invaluable tbh#because every other means is..... 'meh' to me

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

All speak in creation. All living and non-living beings have access to gestures, sounds and music that constitute any language. But linguists often credit only humans with the capacity for language, despite knowing it’s not solely their creation. Language, in fact, is the music of creation (the cosmos) created in equity altogether. Not only Adivasi ones, but languages created by every human society on the planet have been sourced from natural environments, experiences, relationships with the biosphere, everyday activities, art skills and techniques. We Adivasis make use of this musical language in many forms and ways, which then constitute the making of our oral tradition. Our oral literature. This is why we Adivasis address this collective tradition, which includes the oral literature of our ancestors, and today’s written modern literature, as orature and orature cannot be considered to be ‘folk literature’.

As non-Adivasi literature constantly looks upon ‘folk literature’ in isolation from ‘people/folks’, folk literature often ends up denoting an illiterate, rural society, unfamiliar with script and grammar, whose culture lags compared to city folk. Cultures considered simple because their language knows no twists.

From a philosophical standpoint, it is far more complex to define ‘folk’. In philosophy, there is both ‘worldly’ and ‘otherworldly’, both reality and imagination. The ‘folk’ in non-Adivasi societies and civilisations belongs to either humans or gods. ‘Folk’ is a mishmash of earth, sky, underworld and heaven. Indian philosophy and literature have such a conceptualisation of ‘folk’.

Among Adivasis, ‘folk’ doesn’t hold a similar conception. Here ‘folk’ is reality. There is no space for fantasy and the unreal in their world. This is why Adivasis do not categorise or keep their literature in the ambit of ‘folk literature’. They call it purkha sahitya (literature of the ancestors). In Hindi, their literary tradition, (which includes both ancestral and modern-day literature), is called ‘Vachikta’. In English, orature. Because orature isn’t just language, but rather sounds, letters, music, movements and songs. It comprises the languages of animals-birds, rivers-mountains, forests-settlements, planets, sun, moon and the wind. And all this is real, absolutely true. No element is supernatural or even divine. Not miraculous. Each of our moments is connected to all these elements of the cosmos, and we touch and feel them in our day-to-day life. This is why the cultural world of Adivasis is artistic, multicoloured, and multilingual.

Without knowing the nature of language, its mutual associations, the nature of its duets, and its innate contradictions, it is not easy to understand the oratorial tradition, Adivasi ancestral literature and its modern-day works. Speculating from the criteria of so-called mannerly, modern literature, from the aesthetic norms of Hindi literature and culture of India is fruitless.

The conceptions of Adivasi philosophy are different from dominant Western, Indian or Marxist ideas. It neither accepts ‘Satyam Shivam Sundaram’ like the East nor truth and beauty as in the West. Nor does it consider human beings as the eternal truth like Marxists and Dalits. Adivasi philosophy is creationist and naturalist. Adivasi society holds the highest value for known-unknown directions, disciplines, and provisions of the planet, nature and cosmos. There are no concepts around truth-falsity, beauty-ugliness or human-inhuman in their philosophy. It doesn’t consider humans to be great because of their intelligence or ‘humanity’. It firmly believes that everything living and non-living in the universe is equal. Neither is anyone big nor small. All things present in the universe are meaningful and have equity in existence, whether an insect, a plant, a stone or a human being. It accepts knowledge, reason, experience and materiality within the discipline of nature, not against it. Adivasi philosophy does not look at exploration, testing and knowledge in terms of convenience and usefulness, but as symbiotic harmony and existential association with the earth, nature and the entire living world. It looks at the activities and behaviours of the human world, the entire evolutionary process, not against nature and existence but complementing it. It brings things to utility as long as there is no sense of serious damage to any object or creation, to nature and the earth. It follows that there is no degradation or decay of nature and life.

Adivasis don’t fall into the lingual traps of modernity. In their philosophical tradition, they are more realistic and scientific than any society. They never search for truth, experiment with truth and look for humanity. For them, the sun is the sun, the moon is the moon. Water is water. Blood is blood. Human is human.

This is why Adivasi literature cannot be divided into ‘folk literature’ and ‘Nobel literature’. It stays in unanimity. Adivasi thinkers and writers around the world consider their oral and written literature to be inseparable. The difference in thoughts between tradition and modernity in non-Adivasi literature finds no ground in Adivasi society. The coming of new material resources does not completely change a tradition. It doesn’t bring forth any substantial change in one’s philosophy of life. The making of vision, aesthetics and philosophy does not occur overnight. This process is extremely slow and long. From this point of view, the concept of modernity seems like an illusion. If the coming of technical inventions and luxuries like fridges, TVs, mobile phones and the internet guaranteed ‘modernity’ then there’d be no killings in the name of race, religion, caste or gender in Indian society. There wouldn’t have been such continuity in atrocities and discrimination against women, Adivasis, Dalits and backward communities. Our daily behaviour is governed by our philosophy, not by motorcycles, scooters and cars. Air conditionerss can only regulate temperatures outside oneself, not value systems, thoughts and ideas. Those result from one’s philosophical tradition and religious philosophy.

Adivasi literature is the bearer of its philosophical tradition. There is no place for false modernity with the glitter of materialism there. Marathi Adivasi author, Vahru Sonvane, says, “It is incongruous from the point of view of Adivasis for literature to only be written. Thousand-year-long traditions have never stopped. Those traditions are still an integral part of Adivasi life in an inseparable way.”

Mamang Dai, Arunachali adivasi writer, writes, “I am Adivasi, and geography and landscape, the myths and stories of our ancestors… all of these shape my thought process.”

Canadian Aboriginal thinker and author, Akiwanji Dame, says, “Literature is a creative activity. Literature as a unit of creativity is a part of our culture, and we always express it through many ways and mediums. By singing, speaking or writing, all are ultimately part of a unique creativity’.

The oratorial art and literary practices of Adivasis are a set of diverse art forms in which nature plays a major and assured role alongside all other art forms. In the art traditions of the Adivasi world, dancing is necessary for playing, playing music is necessary for dancing, singing is necessary for playing music, and singing, dancing and playing are not possible without the natural habitat. Water, forest and land are the main elements of Adivasi philosophy and art. To look at Adivasi orature in isolation from all these is to deny its philosophical discourse.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Readings, 2023

I didn’t read as much or as widely in 2023 as I had hoped, but what I did read mostly followed a through-line of free-spiritedness, pessimism, and absurdism as part of researching for a theory on the critique of everyday life I’ve been working on. This has involved reading more fiction than in the last few years, which I’ve definitely enjoyed, and finally getting around to several authors I’d been meaning to read for years. A fun reading year I’ve already begun furthering in 2024.

1. Camus, Albert. “Exile and the Kingdom.” Translated by Justin O’Brien. The Plague, The Fall, Exile and the Kingdom, and Selected Essays, by Albert Camus, Everyman’s Library, 2004 [1957], pp. 357–488

A strong collection of short stories, each full of a sense of unease, ennui, melancholy, estrangement/alienation, and even madness. I enjoyed them, though they never fully clicked with me. Above all, they felt substantial, considered, and carefully constructed; perhaps too carefully, as they all had a sense of detachment that seemed a little at odds with their subjects.

2. Machiavelli, Niccolò. The Prince. Edited by Peter Bondanella, translated by Peter Bondanella, OUP, 2008 [ca. 1513] (re-read)

Re-reading The Prince for a second time in less than six months (this time for a seminar rather than myself) was very enjoyable, which is a testament to Machiavelli’s literary skills. Some of the things which stood out to me on this reading more than on previous ones: Machiavelli’s artistic talent, the work being full of tight little sentences both beautiful and cutting; the metaphor of applied sciences (arts), above all medicine; the sheer ubiquity of his implicit republicanism; the degree to which he offers ethical maxims—in the tradition of Nietzsche or La Rochefoucauld—for life that can be more or less applied by anyone. My conviction of the centrality of this little book for all political reasoning, science, and practice only grows. An endlessly fertile work. Bondanella’s translation is tight, evocative, stylish, and still by far the best I’ve come across.

3. Anderson, Perry. Considerations on Western Marxism. Verso, 1979

An accessible and easy introductory essay for the tradition, striking a balance—mostly but not entirely successfully—between productive criticism and productive encouragement. However, Anderson fails and never properly even attempts, despite claiming he would, to establish the coherency and meaningfulness of the concept of Western Marxism itself, without which the work is a little disjointed.

4. La Rochefoucauld, François de. “Moral Reflections or Sententiae and Maxims: fifth edition, 1678”, “Maxims Finally Withdrawn by La Rochefoucauld”, “Maxims Never Published by La Rochefoucauld”. Collected Maxims and Other Reflections, by François de La Rochefoucauld, OUP, 2008 [1664–78], pp. 1–191

Technically sharp, tight, incisive; a wonderful representative of the aphoristic ethical tradition and a refreshing kind of urbane cynicism concerned with living well, i.e., with happiness. Very much begs for re-reading, especially because so much of it will inevitably go over your head on first reading, an inevitable risk of short (or even longer) aphorisms.

5. Cioran, E. M. A Short History of Decay. Translated by Richard Howard, Penguin, 2018 [1949]

Cioran is meant to be lyrically very talented, and certainly there are many aphorisms in this short work that are indeed artistically excellent, but there are also a lot (I’d say slightly more) which I found clumsy. I got the impression he was trying too hard and that where he succeeded it was as much from brute strength as learnt skill. Linked to this, philosophically speaking there were plenty of interesting ideas and themes, but they were insufficiently built upon; the aphoristic form was, I feel, misused here, and worked to undermine rather than reinforce the philosophy. The book felt underwhelming compared to his high reputation. Overall, a good book, definitely worth reading and both a notable product of its time and place and a work for the present, a more than worthwhile study of life’s groundlessness and aporias, but not the masterpiece I’d been hoping for.

6. Cioran, E. M. All Gall Is Divided. Translated by Richard Howard, Arcade, 2019 [1952]

A much stronger work than A Short History of Decay: artistically far superior, masterful in its hyper-short aphoristic form. Even through the prism of a translation, it’s clear that Cioran became much more comfortable writing in French in the three years between the two: the sentences run better, are more careful, more economical, more impactful. In terms of the philosophical content, having finished the book I feel unsure about what it was actually saying, as if it wasn’t saying much at all. I think this is a limitation of such short aphorisms when they're taken in isolation and not used as part of (perhaps prompts for) discussion, philosophy being an inherently dialogic art; I prefer the longer form used by the likes of Nietzsche and Adorno and, indeed, the Cioran of A Short History. Nevertheless, All Gall Is Divided picks up where A Short History of Decay left off, continuing the call for a moderate and moderating scepticism and rejecting fanaticism and faith. As ever, the pessimists are the more respectful and kind thinkers...

7. Althusser, Louis. Machiavelli and Us. Edited by Francois Matheron, translated by Gregory Elliott, Verso, 2011 [1962–86]

A fantastic study of Machiavelli and his materialism; an immensely strong justification of his absolute centrality for materialist analysis and politics. The reading of Machiavelli as the first theorist of political practice as such is especially strong and important, as is the closely related interpretation of his approach and practice as being one of locating specific, concrete conjunctural situations—exactly as a Leninist does—and, sub specie historiae, identifying programmatic tasks immanent in that conjuncture and establishing (and judging) means and aims only with reference to that task, not with reference to whichever subjectively-determined goals the political agent might have as he’s often thought to do (a “vulgar pragmatism”, Althusser calls it). A brilliant, short, essayistic book, strong both as an analysis of Machiavelli per se and (mostly implicitly) as a guide to how he can and must be used by communists.

8. Tartt, Donna. The Little Friend. Bloomsbury, 2002

I read this at random to try and get back into long novels after years of avoiding them, and hopefully it's succeeded because The Little Friend is a great book. Its central characters—especially the protagonist, Harriet, the best child character I’ve read in a very long time��are rich and convincing, its atmosphere and sense of place are perfect, and the sadness and misery which pervades it are excellently handled. The ending is delightfully brutal, a gorgeous flurry of violence. The social criticism that is present throughout just beneath the surface is also well used to set the mood and context, though I would say is a little underdeveloped and maybe somewhat crude, though the perspective of a child is responsible for a lot of that crudeness and so isn’t necessarily a weakness.

9. West, M. L., editor. Greek Lyric Poetry: The Poems and Fragments of the Greek Iambic, Elegiac, and Melic Poets (excluding Pindar and Bacchylides) Down to 450 BC. Translated by M. L. West, OUP, 2008

West's translation is often fairly loose in order to make the poems more comprehensible to a modern audience, and while that's usually something I don't like I have to say he's done a good job here. Arranging the poets chronologically (as much as is possible, anyway) really lets you see the cultural change that occurred over the centuries covered, as old, barbaric, Dionysian Greece gave way to a younger, more sterile, more civilised, more Apollonian regime. Throughout, however, the poets have a profound sense of intimacy and place, a true glimpse at a different way of life and the ephemeral pleasures of a long-gone world. The universal embracing of all the poets—from the oldest to the most recent—of sexual desire in general, without qualification of the sex of the target of that desire, is very stark, and a wonderful demonstration that our modern conception of sexuality is historically relative and must one day fall— we can only hope to be replaced by something much closer to the profound wisdom of the ancient erotic principle. Despite the translation's best attempts and the palpable skill of the poets, a lot of the work here does come across as quite dry, sadly, bereft as it is of its native metre and the accompanying music it was meant for, to say nothing of the social context it was written to be enjoyed in or the extremely fragmentary status of so much of it. But even so, there are throughout stunning fragments of beautiful verse, from little clusters of word combinations that seem to come out of nowhere to whole sustained works that, by some miracle, have come down to us through the millennia. I read this above all to get a better feeling for ancient Greek culture, and in this Greek Lyric Poetry succeeds: it is the collected beauty of a different way of life that can decisively inform our struggle for a new one.

10. Lucretius Carus, Titus. On the Nature of the Universe. Translated by Ronald Melville, OUP, 2008 [ca. 50BC]

Lucretius’ achievement in writing De rerum natura is difficult to comprehend. Simultaneously a powerful cosmology that is barely out of date and a guide to living which remains nearly peerless, it combines, as all good philosophy should, wonderful content with wonderful form, but the degree of his artistic skill is so total that it easily puts him at the summit of philosophical writing, alongside such giants as Nietzsche and Plato. This edition is very strong, with an excellent translation, a very competent introduction, and a large number of explanatory notes that are formatted in a way that doesn’t impact reading the main text at all. Why Melville has translated the title as On the Nature of the Universe, rather than the ubiquitous On the Nature of Things, I don’t know; it’s a strange choice. Maybe he wanted to emphasise the scope of the work, and the universe comes across as more magisterial than “things”? But his translation is excellent, very readable, beautiful.

The subtle, stunningly intelligent atomic physics that Lucretius communicates in such beautiful and evocative ways is amazingly prescient and perceptive. The degree to which it presaged central discoveries of modern science is exhilarating and leaves me a little speechless. To name only a few standout points from the first book: entropy (1.215); the conservation of matter/energy (1.215–25); relativism about time (1.458); molecules (1.483); subatomic particles (1.610). These are things which Lucretius hypothesises on the basis of a masterful combination of observation, experimentation, and reasoning, i.e., upon genuinely scientific grounds. The maturity and sophistication of the entire enterprise is staggering. Among the many, many things that Lucretius is, he is irrefutable evidence that the people who lived even in the distant past were not stupid, and knew how to discover fundamental truths about their world. In so doing he’s also a fantastic standard-bearer for philosophy: this is what our subject can do! See what we can achieve! See what we can know! See our triumph!

His more overtly “philosophical” principles are even more impressive, his atomism, no matter how stunning, being now (after millennia!) outdated. Among such vital and still cutting-edge principles as the causal closure of the physical (1.304) and determination in the last instance (1.546), Lucretius puts forward the genius of Epicureanism in full force: the harmlessness of death, the ubiquitous misery of fearing death, the ease and goodness of viewing death with ambivalence and contempt and carelessness; hedonism; opposition to romance as a social regime (something even Marxists haven’t fully recognised!); opposition to religion (the criticisms of religion in De rerum natura are extremely powerful and gorgeous, heartfelt and motivated by an intoxicating humanism and love and so disgust at the wound that religion is for men), and on and on.

I simply cannot lavish enough praise on De rerum natura. It comes within a hair’s breadth of perfection, being pulled down only by a brief lapse into misogyny and lazy, patriarchal thinking and the affirmation of marriage, something even more disgraceful as, paradoxically and contradictingly, it follows directly on from an unparalleled rejection of romance and the slavery it subjects us to. But even this is confined to a single page. De rerum natura is an entire philosophy for life contained in a relatively short book of poetry: it is a shining jewel of world literature and a defiant, proud demonstration of antiquity’s brilliance and bequeathment to mankind. It remains a live work, begging to be taken up and used in the critical study and critique of the world— communists could learn a great deal from it; Marx’s debt to Lucretius was a good starting point, but it has been criminally underdeveloped. Just beyond brilliant. “Masterpiece” doesn’t even begin to do it justice. Ovid gave some indication, made some attempt, when he wrote that ‘The verses of sublime Lucretius will perish only when a single day brings about destruction of the world’ (Amores 1.15).

11. Cioran, E. M. The Temptation to Exist. Translated by Richard Howard, Arcade Publishing, 2013 [1956]

A strong work of philosophical essay writing, a worthy addition to the French tradition in which Cioran is here attempting to place himself. Lots of interesting ideas skillfully expressed in easy and engaging prose. Cioran’s writing is tight, terse, and considered, and this book has confirmed my judgement from the previous two books of his I read this year that he’s a master of phrases—of little combinations or words—and that this is where his style really excels. In terms of content, The Temptation to Exist definitely has stronger and weaker parts, but rarely falls very far from “good”.

12. Amable, Bruno, and Stefano Palombarini. The Last Neoliberal: Macron and the Origins of France’s Political Crisis. Translated by David Broder and David Fernbach, Verso, 2021 [2018]

Read this in a couple of sittings over a single day, so a relatively easy read. Amable and Palombarini argue that the defining characteristic of the contemporary French social formation is the absence of a dominant social bloc (i.e. voting bloc, support for a party or coalition of parties), and that Macron and LREM are the first to have been able to capitalise on what they call the “bourgeois bloc” of the upper and middle classes who are united by “culturally left/liberal” views and support for European integration.

13. Thacker, Eugene. Infinite Resignation. Repeater, 2018

Infinite Resignation is very easy to read. I read over a hundred pages in a day multiple times, and that’s very unusual for me. I would describe Thacker’s writing style as distinctly “American”: plain, simple, best when it is saying something bluntly, and unsightly when it tries to be artistic and ape the European writers that dominate the book; he’s just not good enough an artist to sound profound when he’s writing a hyper-short aphorism full of pseudo-profound words. But for all this the book is not trivial, and Thacker’s encyclopaedic and constant reference to the long tradition of pessimism adds a huge amount to it. Overall a perhaps surprisingly effective work, one which I’m already in the process of mining for ideas and even some quotations for my main ongoing draft.

14. Lahiri, Jhumpa, editor. The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories. Penguin, 2020

This is a wonderful anthology, full of magic, the fantastical, the strange, the sombre, the melancholy, the poor and the intelligentsia, the city and the countryside, the new and the old, the male and the female, the human and the nonhuman. The selected stories are all excellent, and together convey a really strong sense of Italy and her regionalism, and of it changing over time, with selections from across her modern history as a unified state. There are stories here which are works of unpolished social realism; there are also a large number which come across as something like a fable. All of them make you want to be in love with such an ancient, rich, cultured, and conflicted country, even and especially when you are being shown her ugly underbelly.

15. Kafka, Franz. “The Trial.” The Complete Novels, by Franz Kafka, translated by Edwin Muir and Willa Muir, Vintage Books, 1999 [1915], pp. 11–128

What can one say of Kafka, other than that he is gorgeous? The Trial is a powerful critique of liberalism and capitalist modernity, with the entire system and its well-meaning participants (we might say its bearers— Träger) undercut and subjected to a scathing demystification through the mystifying story. Some interesting things that stood out to me: Joseph K. is unusual for a protagonist in being a very unlikeable person, nothing remarkable but distinctly distasteful and offputting, as well as being the quintessential modern bourgeois; throughout the novel, its recurrent subjects/themes cover, like bullet-points, the central foci of capitalist modernity, most prominently the judiciary and legalism, general bureaucracy, landlordism, the marriage form and monogamy, misogyny/patriarchy, and the interplay between poverty and wealth and their common subjection before the social order itself. The way that Kafka combines form and content is masterful, as the two are always fully in agreement and mutually reinforcing. Even when the gruelling monotony and byzantinism of most of the novel give way without warning to the stochastic, fragmentary, disjointed ending, a product of the book’s incompleteness, it seems almost designed and deliberate, and has a strong emphatic effect.

16. Shawn, Wallace. The Fever. Revised ed., Faber & Faber, 2009 [1990] (re-read; new edition)

The Fever is a brutal work, an emotional powerhouse. It has an amazing power to make you viscerally bleed for the poor and the oppressed, for the downtrodden, for the forgotten and the exploited, and to want to give everything you are to the people and the struggle for freedom. It’s especially cutting for a middle-class reader like the protagonist, for the well-off, for those who think of themselves as good people, because it rips the edifice of money and morality and the liberal order out from under their eyes and shows how the whole regime of wealth and comfort rests upon the backbreaking humiliation and misery of the poor. It’s a cold-hearted, ideologically suffocated person who could read The Fever and not be deeply moved by it and made, even if only for a brief period, to see the world a little differently. Short, sweet like vomit, oppressive like the monsoon heat, it’s a brilliant little play.

I don’t like or agree with several of the revisions made in this edition compared to the original (which I read many years ago); maybe that’s because some of the lines of the original which have been burned into my mind have been erased or altered, but some of the central moments of the play—most of all the little church in the poor country, and the guerilla in the café—seem to me less powerful and direct.

17. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits. Translated by R. J. Hollingdale, CUP, 1996 [1878–80]

A fantastic work that is a brilliant life companion for the titular free spirits. It’s wonderful to see Nietzsche as a critical but sincere advocate and follower of the natural sciences and the Enlightenment. This is a somewhat short review compared to some of the others on this list, but don’t mistake that for a lacklustre attitude towards the work on my part: it’s more than anything because there is so much—and so much that is good—in these “travel books” as Nietzsche called them that I struggle to think of where to begin with describing them. They are immensely valuable, as is everything by Nietzsche, but spending half a year slowly chewing through these couple of thousand aphorisms has given me a lot, and a huge pool of ideas and references for my writing. They do exhibit marks of underdevelopment, both in content and style, compared to his later, “mature” works, but nonetheless they amount to a very valuable salvo against the world we oppose and of considerable worth irrespective of their place within Nietzsche’s oeuvre.

18. Camus, Albert. “The Myth of Sisyphus.” Translated by Justin O’Brien. The Plague, The Fall, Exile and the Kingdom, and Selected Essays, by Albert Camus, Everyman’s Library, 2004 [1942], pp. 489–605

For a work as famous as this is, I wasn’t very impressed by The Myth of Sisyphus. It seemed to me more like an extremely bloated plan for an essay rather than a finished one, complete with critical, central failures, including a failure to ever properly define or characterise vital concepts (including the absurd!) and to even attempt to justify enormous leaps of “argument” (without justification they’re not arguments, only stipulations at best) that are essential to the essay as a whole, most notably the rejection of suicide which is made with a handwaving nonentity of a segway into the rest of the work. The huge amount of space given over to the analysis of works of literature also seemed wildly misplaced and detracted from the essay; the substance of what Camus is arguing with them could be stated in two pages. I agree with a huge amount of what Camus is saying here, just not with really any of the ways in which he is stitching those things together. Reading this has sadly reinforced my preconception that Camus was a good philosophical novelist but a poor philosopher (a distinction he actually conveys well in this essay, ironically enough, including the weakness of the former group’s attempts to fulfil those of the latter— I can’t tell if he thought he was subject to those weaknesses or not, but he was). Nevertheless, the philosophy being put forward here is a strong one, a distinctly Mediterranean foil to the Germanic Nietzsche. The discussion of absurd archetypes, namely the seducer, the actor, and the conquerer, was a particular stand-out that I think offers good strategies for different free spirits. I have been utilising The Myth of Sisyphus a lot in scraps of writing towards my main ongoing piece, I want to emphasise the significance and maturity of its ideas, but as a piece of writing it’s surprisingly poor and lets down its actual position considerably.

19. Camus, Albert. “The Plague.” Translated by Justin O’Brien. The Plague, The Fall, Exile and the Kingdom, and Selected Essays, by Albert Camus, Everyman’s Library, 2004 [1947], pp. 1–272

The first chapter of this book has one of the best atmospheres I’ve ever read, a near-perfect building of tension and dread that masterfully begins a masterful story. The teaching of philosophy—and of a philosophy—through fiction is difficult, and in my experience fails more often than it succeeds, but Camus has succeeded to such a degree in The Plague that I’m left feeling like a novel was the best way to present the ideas, stronger than a nonfiction work, stronger than The Myth of Sisyphus. Beautiful and brilliant, the sort of work someone can easily pick up, be awe-struck by, and decide to adopt as their guiding document in life— and be well-chosen in doing so. Everything is as it should be, and the cumulative effect is something like perfect. A sublime book to end the year with.

1 note

·

View note

Note

to be fair, i DID steal the title of borealis green from the taylor swift song snow on the beach ft. lana del rey. it was inspired by this line in the song:

I searched aurora borealis green I've never seen someone lit from within Blurring out my periphery

which in turn inspired this line in the fic:

She lifts her gaze and falls into his, wrapped in green like northern lights.

nina has a point though like. every single artist/creator first had an idea they wanted to share in a way that would be really meaningful to others. she really said it best when she wrote, "they’re inviting you to a special part of their brain that they’ve decorated with their own experiences, references and visuals — things that they love and passed onto their favourite characters, so they can hopefully reach you." that's why so many fic titles are song lyrics, why the greatest literary works allude to other works, why fanworks exist. we make meaning from other people's meaning-making, and what's so amazing about that is that it comes out original and new every time someone creates their own thing based off the source of inspiration.

for example, i listened to "snow on the beach" and was inspired for a feligami fic because of the feeling of strangeness of new love the song conveyed - like the narrator is completely thrown off by such strong feelings and beautiful devotion. i imagined the same would be true for canon kagami's experience with felix! and i felt particularly strong about the line "i searched auroria borealis green" because to kagami, the color of felix's eyes has transcended the ordinary into phenomenal. especially when he gives her heart eyes. it must make her feel strange and weird and so, so happy, and isn't that such a nice thing to feel? and voila! there's my fic.

if someone had fed an AI this same idea to generate a "fanfic," what kind of deeper meaning would be gleaned? would there be carefully crafted language to make meaning, or double meanings? would there be references and allusions to other works you can make meaning of to form your opinion of the current work? until AI can do that (which God forbid EVER happens) there is no way it can be as good as anything a human being produces.

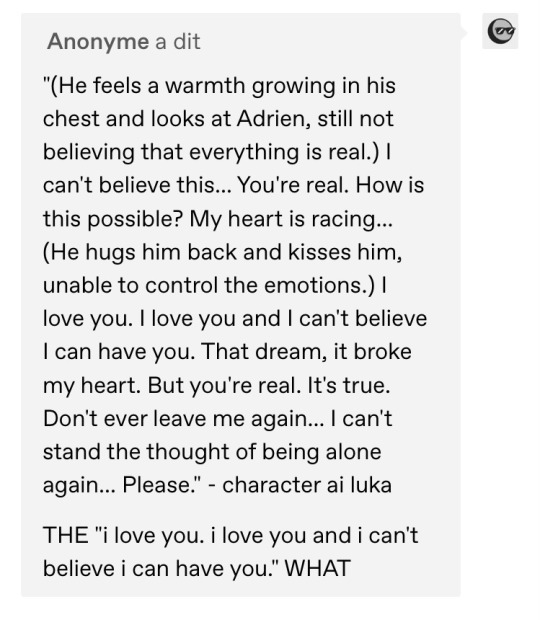

reading through this AI snippet anon gave, i see only a cheap perversion of the feelings this kind of fic can convey when written by someone intending to give you a piece of their heart.

"(he) looks at Adrien, still not believing that everything is real. "I can't believe this... You're real."

LOL way to say the same thing twice?! and without any overarching thematic meaning to "belief" or "real" either smh

"He hugs him back and kisses him, unable to control the emotions. 'I love you. I love you and I can't believe I have you.' "

?!?! seems like luka's controlling his emotions to me! i don't see him crying screaming shaking adrien or wracking with sobs. he expressed himself super coherently and also extremely basically. why is belief so hard for luka? why is he so shaken by the fact that adrien is real? if he's so overwhelmed, a hug and a kiss shouldn't nearly be enough to suffice his show of enthusiasm.

"Don't ever leave me again... I can't stand the thought of being alone again... Please."

well now this is just transgressing against luka's characterization. he has shown he is fine being alone, that he does not make people stay with him if they don't want to, that he makes no impositions on others' decisions. the only meaning i got from this sentence is that the AI didn't watch the show or care enough about luka to give him good dialogue.

this is an absolute imitation of human interaction and if this were an ao3 fic i would've clicked out within the first paragraph.

nina you put everything so eloquently but my favorite part has to be: "it’s very disheartening to see that people would rather ask a machine to spit out some easily digestible but impersonal interactions than give your work a chance." tbh i can't even digest the ai content, simply BECAUSE it's so impersonal. but i know that what the AI imitates is what lots of people are looking for/ personally want to see. which leads me to my other favorite part of your essay: "I can guarantee there are beautiful pieces of fanwork out there that will cater to your tastes and haunt you for years in a way Character AI or Chat GPT never could. And the good news is — if you don’t find anything, it means it’s time to write it yourself!"

PLEASE WRITE YOUR OWN STUFF!!! PLEASE DRAW YOUR OWN STUFF!! PLEASE MAKE YOUR OWN STUFF INSTEAD OF GIVING OTHER PEOPLE'S TO AN AI!! art is little pieces of our fragile human hearts that we want to share with you! we want you to get meaning out of it, we want you to be inspired by it to make your own!

watching character ai lukadrien create the most heart wrenching debilitatingly angsty love story to ever love story ever

Hey, I can tell there’s no malice behind your ask, but — don’t do that.

I write fanfiction myself, and a lot goes into it:

1. Unreasonable amounts of ✨ Time and Effort ✨

Just the other day, my WIP kept me up until 2 AM, because I wanted it to be neatly polished before even sending it to my beta readers (@paracosmicfawn and @dragongutsixofficial). The first thing I did the following morning was re-read it again, to correct any typos and inconsistencies my tired brain might have missed the night prior.

2. Research and analysis

For a cute little Lukadrien scene I wrote with my ✨ awesome girlfriend ✨ — something that was never even going to be published — I went through a dozen different sources trying to get a better understanding of what meditation actually is and to capture the philosophy behind it accurately. This does not make me special — all authors do it out of dedication and love for their craft, but it’s energy that could be spent doing literally anything else, especially when you consider how horrifyingly lonely the writing process can be (see point 1).

Also, there’s a reason I spend so much time making analysis posts on Silly Little Blorbos who do not exist! It gets my brain running and allows me to sharpen my understanding of the characters, so I can write them properly in my works.

3. A unique perspective on the characters, the source media, and life in general

Which gives all the flavour to my favourite AO3 works out there.

Like, yes, that extract you sent in your follow-up ask is cute, I guess, but it’s also incredibly generic:

When actual living breathing human (or Senti) beings share their work with you, they’re inviting you to a special part of their brain that they’ve decorated with their own experiences, references and visuals — things that they love and passed onto their favourite characters, so they can hopefully reach you. For instance, Character AI would never have had the genius idea to compare Felix’s eyes to an aurora borealis; this could have only sparked from @wackus-bonkus-maximus’ brain. Similarly, my version of Felix will often reference works of art and literature that left a strong impact on me as a child — an impact I’m sure can also be sensed in my approach to storytelling and even in the way I structure sentences and paragraphs.

Which leads me to my final and most important point:

4. EMOTIONAL BAGGAGE™

Because let’s be real — there’s a reason our brains latch onto certain characters, and said reasons aren’t always sunshine and rainbows. I’ve cried more writing about the Senticousins than over the loss of certain people or relationships in my own life. Long before that, I latched onto Clive and gave him everything I felt was missing from my life as a teenager, so I could live vicariously through him. And of course, I always make my characters some flavour of queer, because for a long time this was the only outlet I got for my own feelings and identity.

It takes a lot of vulnerability to put all of this on the Internet for others to read and judge, and it’s very disheartening to see that people would rather ask a machine to spit out some easily digestible but impersonal interactions than give your work a chance.

I can guarantee there are beautiful pieces of fanwork out there that will cater to your tastes and haunt you for years in a way Character AI or Chat GPT never could. And the good news is — if you don’t find anything, it means it’s time to write it yourself!

And of course, I cannot end this post without encouraging everyone to read about the writers’ and actors’ strike currently unfolding in the US.

#miraculous ladybug#miraculous fanfic#borealis green#luka couffaine#lukadrien#felix graham de vanily#kagami tsurugi#feligami#adrien agreste#writing#fanfiction#fanfic#ai fic#ai generated

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

fan language: the victorian imaginary and cnovel fandom

there’s this pinterest image i’ve seen circulating a lot in the past year i’ve been on fandom social media. it’s a drawn infographic of a, i guess, asian-looking woman holding a fan in different places relative to her face to show what the graphic helpfully calls “the language of the fan.”

people like sharing it. they like thinking about what nefarious ancient chinese hanky code shenanigans their favorite fan-toting character might get up to—accidentally or on purpose. and what’s the problem with that?

the problem is that fan language isn’t chinese. it’s victorian. and even then, it’s not really quite victorian at all.

--------------------

fans served a primarily utilitarian purpose throughout chinese history. of course, most of the surviving fans we see—and the types of fans we tend to care about—are closer to art pieces. but realistically speaking, the majority of fans were made of cheaper material for more mundane purposes. in china, just like all around the world, people fanned themselves. it got hot!

so here’s a big tipoff. it would be very difficult to use a fan if you had an elaborate language centered around fanning yourself.

you might argue that fine, everyday working people didn’t have a fan language. but wealthy people might have had one. the problem we encounter here is that fans weren’t really gendered. (caveat here that certain types of fans were more popular with women. however, those tended to be the round silk fans, ones that bear no resemblance to the folding fans in the graphic). no disrespect to the gnc old man fuckers in the crowd, but this language isn’t quite masc enough for a tool that someone’s dad might regularly use.

folding fans, we know, reached europe in the 17th century and gained immense popularity in the 18th. it was there that fans began to take on a gendered quality. ariel beaujot describes in their 2012 victorian fashion accessories how middle class women, in the midst of a top shortage, found themselves clutching fans in hopes of securing a husband.

she quotes an article from the illustrated london news, suggesting “women ‘not only’ used fans to ‘move the air and cool themselves but also to express their sentiments.’” general wisdom was that the movement of the fan was sufficiently expressive that it augmented a woman’s displays of emotion. and of course, the more english audiences became aware that it might do so, the more they might use their fans purposefully in that way.

notice, however, that this is no more codified than body language in general is. it turns out that “the language of the fan” was actually created by fan manufacturers at the turn of the 20th century—hundreds of years after their arrival in europe—to sell more fans. i’m not even kidding right now. the story goes that it was louis duvelleroy of the maison duvelleroy who decided to include pamphlets on the language with each fan sold.

interestingly enough, beaujot suggests that it didn’t really matter what each particular fan sign meant. gentlemen could tell when they were being flirted with. as it happens, meaningful eye contact and a light flutter near the face may be a lingua franca.

so it seems then, the language of the fan is merely part of this victorian imaginary we collectively have today, which in turn itself was itself captivated by china.

--------------------

victorian references come up perhaps unexpectedly often in cnovel fandom, most often with regards to modesty.

it’s a bit of an awkward reference considering that chinese traditional fashion—and the ambiguous time periods in which these novels are set—far predate victorian england. it is even more awkward considering that victoria and her covered ankles did um. imperialize china.

but nonetheless, it is common. and to make a point about how ubiquitous it is, here is a link to the twitter search for “sqq victorian.” sqq is the fandom abbreviation for shen qingqiu, the main character of the scum villain’s self-saving system, by the way.

this is an awful lot of results for a search involving a chinese man who spends the entire novel in either real modern-day china or fantasy ancient china. that’s all i’m going to say on the matter, without referencing any specific tweet.

i think people are aware of the anachronism. and i think they don’t mind. even the most cursory research reveals that fan language is european and a revisionist fantasy. wikipedia can tell us this—i checked!

but it doesn’t matter to me whether people are trying to make an internally consistent canon compliant claim, or whether they’re just free associating between fan facts they know. it is, instead, more interesting to me that people consistently refer to this particular bit of history. and that’s what i want to talk about today—the relationship of fandom today to this two hundred odd year span of time in england (roughly stuart to victorian times) and england in that time period to its contemporaneous china.

things will slip a little here. victorian has expanded in timeframe, if only because random guys posting online do not care overly much for respect for the intricacies of british history. china has expanded in geographic location, if only because the english of the time themselves conflated china with all of asia.

in addition, note that i am critiquing a certain perspective on the topic. this is why i write about fan as white here—not because all fans are white—but because the tendencies i’m examining have a clear historical antecedent in whiteness that shapes how white fans encounter these novels.

i’m sure some fans of color participate in these practices. however i don’t really care about that. they are not its main perpetrators nor its main beneficiaries. so personally i am minding my own business on that front.

it’s instead important to me to illuminate the linkage between white as subject and chinese as object in history and in the present that i do argue that fannish products today are built upon.

--------------------

it’s not radical, or even new at all, for white audiences to consume—or create their own versions of—chinese art en masse. in many ways the white creators who appear to owe their whole style and aesthetic to their asian peers in turn are just the new chinoiserie.

this is not to say that white people can’t create asian-inspired art. but rather, i am asking you to sit with the discomfort that you may not like the artistic company you keep in the broader view of history, and to consider together what is to be done about that.

now, when i say the new chinoiserie, i first want to establish what the original one is. chinoiserie was a european artistic movement that appeared coincident with the rise in popularity of folding fans that i described above. this is not by coincidence; the european demand for asian imports and the eventual production of lookalikes is the movement itself. so: when we talk about fans, when we talk about china (porcelain), when we talk about tea in england—we are talking about the legacy of chinoiserie.

there are a couple things i want to note here. while english people as a whole had a very tenuous knowledge of what china might be, their appetites for chinoiserie were roughly coincident with national relations with china. as the relationship between england and china moved from trade to out-and-out wars, chinoiserie declined in popularity until china had been safely subjugated once more by the end of the 19th century.

the second thing i want to note on the subject that contrary to what one might think at first, the appeal of chinoiserie was not that it was foreign. eugenia zuroski’s 2013 taste for china examines 18th century english literature and its descriptions of the according material culture with the lens that chinese imports might be formative to english identity, rather than antithetical to it.

beyond that bare thesis, i think it’s also worthwhile to extend her insight that material objects become animated by the literary viewpoints on them. this is true, both in a limited general sense as well as in the sense that english thinkers of the time self-consciously articulated this viewpoint. consider the quote from the illustrated london news above—your fan, that object, says something about you. and not only that, but the objects you surround yourself with ought to.

it’s a bit circular, the idea that written material says that you should allow written material to shape your understanding of physical objects. but it’s both 1) what happened, and 2) integral, i think, to integrating a fannish perspective into the topic.

--------------------

japanning is the name for the popular imitative lacquering that english craftspeople developed in domestic response to the demand for lacquerware imports. in the eighteenth century, japanning became an artform especially suited for young women. manuals were published on the subject, urging young women to learn how to paint furniture and other surfaces, encouraging them to rework the designs provided in the text.

it was considered a beneficial activity for them; zuroski describes how it was “associated with commerce and connoisseurship, practical skill and aesthetic judgment.” a skillful japanner, rather than simply obscuring what lay underneath the lacquer, displayed their superior judgment in how they chose to arrange these new canonical figures and effects in a tasteful way to bring out the best qualities of them.

zuroski quotes the first english-language manual on the subject, written in 1688, which explains how japanning allows one to:

alter and correct, take out a piece from one, add a fragment to the next, and make an entire garment compleat in all its parts, though tis wrought out of never so many disagreeing patterns.

this language evokes a very different, very modern practice. it is this english reworking of an asian artform that i think the parallels are most obvious.

white people, through their artistic investment in chinese material objects and aesthetics, integrated them into their own subjectivity. these practices came to say something about the people who participated in them, in a way that had little to do with the country itself. their relationship changed from being a “consumer” of chinese objects to becoming the proprietor of these new aesthetic signifiers.

--------------------

i want to talk about this through a few pairs of tensions on the subject that i think characterize common attitudes then and now.

first, consider the relationship between the self and the other: the chinese object as something that is very familiar to you, speaking to something about your own self vs. the chinese object as something that is fundamentally different from you and unknowable to you.

consider: [insert character name] is just like me. he would no doubt like the same things i like, consume the same cultural products. we are the same in some meaningful way vs. the fast standard fic disclaimer that “i tried my best when writing this fic, but i’m a english-speaking westerner, and i’m just writing this for fun so...... [excuses and alterations the person has chosen to make in this light],” going hand-in-hand with a preoccupation with authenticity or even overreliance on the unpaid labor of chinese friends and acquaintances.

consider: hugh honour when he quotes a man from the 1640s claiming “chinoiserie of this even more hybrid kind had become so far removed from genuine Chinese tradition that it was exported from India to China as a novelty to the Chinese themselves”

these tensions coexist, and look how they have been resolved.

second, consider what we vest in objects themselves: beaujot explains how the fan became a sexualized, coquettish object in the hands of a british woman, but was used to great effect in gilbert and sullivan’s 1885 mikado to demonstrate the docility of asian women.

consider: these characters became expressions of your sexual desires and fetishes, even as their 5’10 actors themselves are emasculated.

what is liberating for one necessitates the subjugation and fetishization of the other.

third, consider reactions to the practice: enjoyment of chinese objects as a sign of your cosmopolitan palate vs “so what’s the hype about those ancient chinese gays” pop culture explainers that addressed the unconvinced mainstream.

consider: zuroski describes how both english consumers purchased china in droves, and contemporary publications reported on them. how:

It was in the pages of these papers that the growing popularity of Chinese things in the early eighteenth century acquired the reputation of a “craze”; they portrayed china fanatics as flawed, fragile, and unreliable characters, and frequently cast chinoiserie itself in the same light.

referenda on fannish behavior serve as referenda on the objects of their devotion, and vice versa. as the difference between identity and fetish collapses, they come to be treated as one and the same by not just participants but their observers.

at what point does mxtx fic cease to be chinese?

--------------------

finally, it seems readily apparent that attitudes towards chinese objects may in fact have something to do with attitudes about china as a country. i do not want to suggest that these literary concerns are primarily motivated and begot by forces entirely divorced from the real mechanics of power.

here, i want to bring in edward said, and his 1993 culture and imperialism. there, he explains how power and legitimacy go hand in hand. one is direct, and one is purely cultural. he originally wrote this in response to the outsize impact that british novelists have had in the maintenance of empire and throughout decolonization. literature, he argues, gives rise to powerful narratives that constrain our ability to think outside of them.

there’s a little bit of an inversion at play here. these are chinese novels, actually. but they’re being transformed by white narratives and artists. and just as i think the form of the novel is important to said’s critique, i think there’s something to be said about the form that fic takes and how it legitimates itself.

bound up in fandom is the idea that you have a right to create and transform as you please. it is a nice idea, but it is one that is directed towards a certain kind of asymmetry. that is, one where the author has all the power. this is the narrative we hear a lot in the history of fandom—litigious authors and plucky fans, fanspaces always under attack from corporate sanitization.

meanwhile, said builds upon raymond schwab’s narrative of cultural exchange between european writers and cultural products outside the imperial core. said explains that fundamental to these two great borrowings (from greek classics and, in the so-called “oriental renaissance” of the late 18th, early 19th centuries from “india, china, japan, persia, and islam”) is asymmetry.

he had argued prior, in orientalism, that any “cultural exchange” between “partners conscious of inequality” always results in the suffering of the people. and here, he describes how “texts by dead people were read, appreciated, and appropriated” without the presence of any actual living people in that tradition.

i will not understate that there is a certain economic dynamic complicating this particular fannish asymmetry. mxtx has profited materially from the success of her works, most fans will not. also secondly, mxtx is um. not dead. LMAO.

but first, the international dynamic of extraction that said described is still present. i do not want to get overly into white attitudes towards china in this post, because i am already thoroughly derailed, but i do believe that they structure how white cnovel fandom encounters this texts.

at any rate, any profit she receives is overwhelmingly due to her domestic popularity, not her international popularity. (i say this because many of her international fans have never given her a cent. in fact, most of them have no real way to.) and moreover, as we talk about the structure of english-language fandom, what does it mean to create chinese cultural products without chinese people?

as white people take ownership over their versions of stories, do we lose something? what narratives about engagement with cnovels might exist outside of the form of classic fandom?

i think a lot of people get the relationship between ideas (the superstructure) and production (the base) confused. oftentimes they will lob in response to criticism, that look! this fic, this fandom, these people are so niche, and so underrepresented in mainstream culture, that their effects are marginal. i am not arguing that anyone’s cql fic causes imperialism. (unless you’re really annoying. then it’s anyone’s game)

i’m instead arguing something a little bit different. i think, given similar inputs, you tend to get similar outputs. i think we live in the world that imperialism built, and we have clear historical predecessors in terms of white appetites for creating, consuming, and transforming chinese objects.

we have already seen, in the case of the fan language meme that began this post, that sometimes we even prefer this white chinoiserie. after all, isn’t it beautiful, too?

i want to bring discomfort to this topic. i want to reject the paradigm of white subject and chinese object; in fact, here in this essay, i have tried to reverse it.

if you are taken aback by the comparisons i make here, how can you make meaningful changes to your fannish practice to address it?

--------------------

some concluding thoughts on the matter, because i don’t like being misunderstood!

i am not claiming white fans cannot create fanworks of cnovels or be inspired by asian art or artists. this essay is meant to elaborate on the historical connection between victorian england and cnovel characters and fandom that others have already popularized.

i don’t think people who make victorian jokes are inherently bad or racist. i am encouraging people to think about why we might make them and/or share them

the connections here are meant to be more provocative than strictly literal. (e.g. i don’t literally think writing fanfic is a 1-1 descendant of japanning). these connections are instead meant to 1) make visible the baggage that fans of color often approach fandom with and 2) recontextualize and defamiliarize fannish practice for the purposes of honest critique

please don’t turn this post into being about other different kinds of discourse, or into something that only one “kind” of fan does. please take my words at face value and consider them in good faith. i would really appreciate that.

please feel free to ask me to clarify any statements or supply more in-depth sources :)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

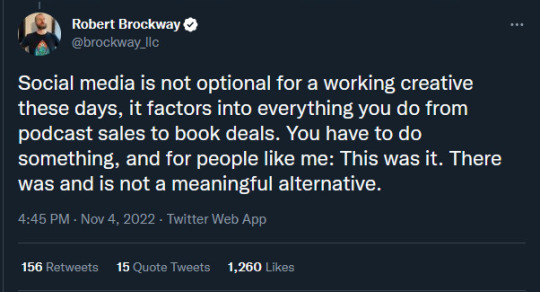

I saw this tweet recently. It was part of a series of tweets about the uncertain fate of Twitter, most mired in anxiety about where one can go after Twitter collapses (as currently seems likely). I wanted to specifically hone in on this tweet, though.

Some cursory research shows me Robert Brockway is, as implied here, an author, primarily of various -punk science fiction. He is published by Tor Books, a pretty large publishing house that specializes in sci-fi and fantasy. I think what Mr. Brockway is so anxious about is not a problem with Twitter but rather a problem with the book publishing industry, which has been remarkably, mind-bogglingly mismanaged for decades.