#raskolnikov for example

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

you read old classics because youre actually smart. i read old classics because i like making fun of people from the 1800s. we are not the same.

#for the sake of my dignity i feel obligated to say that yes obviously i have. reading comprehension. have you seen the shit ive said#about orv. wait no not tha-#raskolnikov for example#is a stinky little guy who passes out every 5 seconds#lm fucking ao#and that guy from dagon#dude#he sees eldritch horror and he goes “AAAAA” and thats literally the story.#thats it#dorian is british narcissus.#howdoitag#bookblr#the only character i refuse to shit on is charles darnay#rip charles darnay you arguably aro coded king

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do people write fanfiction of 19th century Russian literature? Because I for sure have some crack shipping ideas for Smerdyakov and Raskolnikov... in a AU in which they never regret their crimes... which you know, it's more complicated than that, there's a lot of angst, but I do think that Raskolnikov's mommy issues and melancholic nature would pair really well with Smerdyakov's daddy issues and subversive nature... also they're both Dostoyevsky's characters which means they're already halfway into homo-affectionate territory / angsty / extremely passionate territory, also these two are both interesting weirdos and they would have the most unhinged conversations late at night (I'm a romantic I know)

One thing I always hated in the literary groups I tried to be a part of was how joyless the discussions were, Dostoevsky books can be genuinely funny and laughably intense, without being less complex or philosophical, you can have multiple experiences and discussions you know... I mean, in a just world you should be able to crack ship Smerdyakov and Raskolnikov, that's what I mean

#dostoyevsky#brothers karamazov#crime and punishment#literature#i really love don quixote's discussions on mental health and the socialization of mentally ill people for example#at the same time it is one of the funniest books ever and this aspect does not overshadow the serious discussions the text suggests#by being so faithful to how our experiences work in real life - without genre categorization - these books just prove how genius they are..#anyway#this is about crack fanfiction#fanfiction#fyodor dostoevsky#russian literature#rodion romanovich raskolnikov#pavel smerdyakov#classic literature#fanfic

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

chat guess whos old bsd hyperfixation from 2021-2022 (ish) resurfaced and who is now rewatching all of it and experiencing season 4 and 5 for the first time and losing my MIND at the characters i knew from the manga being animated

spoilers its me

#bungou stray dogs#bsd sigma#bsd#the autism hit#this image is of a message i sent to my friends on discord#i love him sooooo much you dont understand#i just finished season 4 ITS SO COOL#i read the manga when i used to be a fan but it was 2 yrs ago so i forgot lots of it#i remember the important things though#like sigma for example#I WILL BE MAKING BSD ART AND POSTING IT#SOON I SWEAR im just busy with school ugh#people who understand and appreciate that bsd fyodor is based off raskolnikov talk to me please#i finished crime and punishment recently and its my favourite book ever#unrelated to bsd cuz i started it way before getting back into bsd

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Conflict

Conflict - a struggle between two opposing forces

Key Character Terms

1. Protagonist

The main character in a literary work

Usually seen as good, upright, respectable, and always attempting to take the proper course of action

Is not always good

For example, in Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff, a brooding and vengeful man, is the protagonist

Thus, the protagonist is a central character, regardless of whether he or she is good or bad

Note: Some literary works may involve an animal protagonist, such as Buck in Call of the Wild, or the animal characters in folk tales or fables.

2. Anti-Hero

When the protagonist is flawed or dominated by negative traits or questionable behavior, he or she is called an "anti-hero"

The term "anti-hero" does not, however, mean that the central character stands in opposition to an actual hero in the story or novel

Rather, it means that the central character stands in opposition to the traditional idea of a hero

3. Antagonist

Stands in opposition to the protagonist

In most novels, the protagonists and antagonists will be clearly distinct and remain consistent

In general, the antagonist will be viewed as bad, wicked, or malicious

Even if dominated by negative traits, however, the antagonist can be just as significant and complex a character as the protagonist

4 Major Types of Conflict

By observing the manner in which a character resolves or doesn’t resolve a conflict, one can gain insight into the character’s qualities, values, and personality.

1. Character’s struggle against nature

When a character must overcome some natural obstacle or condition, a conflict with nature occurs

For example, the men in "The Open Boat" must strive to reach land or perish at sea

Floods, snowstorms, insects, and animals may all constitute a conflict with nature

There are, however, less obvious manifestations of nature that can also constitute a conflict, such as plague or famine

2. Character’s struggle against an antagonist

A struggle between two people is a common element in many works of literature

For example, in Hamlet, Hamlet is involved in a conflict with his uncle, King Claudius, who seeks to have Hamlet killed

However, a conflict between two people is not always openly hostile

For example, in Crime and Punishment, the young murderer Raskolnikov and the police investigator Porfiry engage in a psychological conflict, a battle of wits

3. Character’s struggle against society

A struggle against society occurs when a character is at odds with a particular social force or condition produced by society, such as poverty, political revolution, a social convention, or set of values

For example, in Nicholas Nickleby, the protagonist stands in conflict with a hypocritical education system, while in Bleak House it is a corrupt legal system that functions as the major antagonist

4. Struggle between competing elements within the character (internal conflict)

Within a character, aspects of his or her personality may struggle for dominance

These aspects may be emotional, intellectual, or moral

Examples:

An "emotional" conflict would occur if the protagonist chose an unworthy lover over someone who is devoted

An “intellectual” conflict could entail accepting or rejecting one’s religion

A “moral” conflict might pose a choice between honoring family or country

Such conflicts typically leave the character indecisive and agitated

When such conflicts are resolved, the resolution may be successful or unsuccessful

Writing Notes & References ⚜ Worksheet: Conflict

#writing notes#writeblr#dark academia#spilled ink#studyblr#fiction#conflict#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#poets on tumblr#literature#poetry#creative writing#writing reference#writing resources

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the modern publishing landscape, these days, I think like we do not have many (if any) point-of-view characters with low social motivation for whatever reason.

Sure, there are lots of characters with social anxiety or other perceived or legitimate foibles to overcome, there are many YA villain origin stories, and there are many unpalatable, traditionally "unlikable" men in classics, but disregarding those, who else do we have?

Can the state of openly being alone (and content) rarely be presented as morally-neutral or as the end result of a narrative? Must it always be that either being alone is the starting point, so there's room for "personal growth," or that being alone is seen as "undesirable" and/or an indication that the person alone has a "problem" or something otherwise wrong with them, like a deficit or moral failing that in some kind of karmic way gives them "what they deserve," which is being alone and discontent with it?

Characters with society anxiety, any differences in communication, or other reasons that interfere with forging connections "don't count" because they may still be motivated. Traits such as these only stand in the way of gaining relationships, as plot obstacles. They aren't intrinsically tied to indifference or to low motivation. So, these characters clearly are not experiencing a lack of interest. And they are not the ones rejecting others. Thus, they "don't count" as far as the archetype that I'm looking for goes.

Characters who undergo villain arcs or otherwise negative arcs may want to maintain their relationships or gain them, so some examples are immediately disqualified (hence not having low social motivation), even if they are the type of character most likely to alienate themselves by a story's end, conflicting with what they wanted.

(Unfortunately, Coriolanus Snow, who is quite close to the type of protagonist I'm searching for "doesn't count" because he has some drive to keep people in his life.

Rafal Mistral partially "counts," and is satisfying as a character, but also doesn't count because he temporarily makes "friends" or allies, depending on how you look at his exploits. Yet, despite all this, not having friends isn't exactly framed as a morally-neutral state either, so he is also disqualified by the end. Basically, he does have low social motivation, but his narrative lacks the conditions that would make the natural consequences of that low motivation play out for themselves. He is always surrounded by people, even if he hates every last one of them.

And, generally speaking, the usual, moody-broody, "misunderstood" YA love-interests very easily "don't count" because they have a desire to get closer to their object of affection.

Even Katniss Everdeen, an overall good person, who usually views herself as "unlikable," befriends others, originally for pragmatic, survival purposes. However, she does start with low social motivation, so that's something in her favor.

And yes, I'm aware that we need other people in this world—I would just like to see someone prove that supposed truth wrong once. And perhaps succeed in their world, if that's not too much to ask for.)

Also, are there any instances of characters who progressively alienate themselves from others, in which that progression is not inherently seen as negative? Like, what about non-corrupt misanthropes? Are there few of those in literature? (Maybe—Eleanor Oliphant from literary fiction counts, but something about that book did not appeal me and I didn't finish it.)

Classics guys sort of "count," but I haven't really seen examples of any comparable protagonists today since many authors and readers write and look for "relatability" in blank slate everyman figures oftentimes.

(I'm not done with Crime and Punishment yet, but Raskolnikov is very tentatively looking like a safe bet for a character who may end up alone and who may not be completely malcontent over such a fate, even if I'm expecting tragedy. I'm that not far along, but I also wouldn't mind it too greatly if he died, I suppose.

And even Sherlock Holmes has Watson as his constant, even if he's notoriously asocial! So he "doesn't count" either.

Carol from Main Street also comes close, but still ultimately desires approval from others.

Maybe no one is truly immune to humanity and I should give up on this notion?)

How many pov characters out there are 1) apathetic toward the masses and 2a) either alienate themselves as the plot progresses or 2b) do not make any friends? (I will allow them making friends and consequently losing them though because that still ends in net zero!)

Indeed, this "gap" in protagonists I've been running into lately, especially with coming-of-age arcs and protagonists whose arc is some form of "getting out of their shell," is: why do we (almost?) never see protagonists who just flat-out don't progress in terms of connecting with fellow humans?

Wouldn't having even a handful of those types be reflective of reality? (We as a society are more disconnected than ever, to be fair, despite constantly having access to one another via technology.)

Or I would completely understand it, if it were narratively impractical to have a plot in which a protagonist makes zero friends. Maybe, it's a near-unwritable form for a story?

So, my question is: does anyone have book recommendations, which present a character whose end goal is not to make friends or forge connections (any other ambitions or motivations are fine) and whose state of being friendless both lasts and is regarded as morally-neutral or as not outright evil? Any genre is fine. High fantasy is preferable. I am stumped.

(I also wouldn't mind recommendations of books in which the protagonist is vilified due to being alone, even if that is not my primary query here.)

#bookblr#dark academia#writing#introvert#writeblr#books#booklr#bookworm#hunger games#introversion#bookish#book#writer#writblr#creative writing#tbosas#the ballad of songbirds and snakes#coriolanus snow#the hunger games#book recommendations#books and reading#crime and punishment#raskolnikov#fandom meta#book reccs#fandom#eleanor oliphant is completely fine#school for good and evil#rafal mistral#rise of the school for good and evil

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

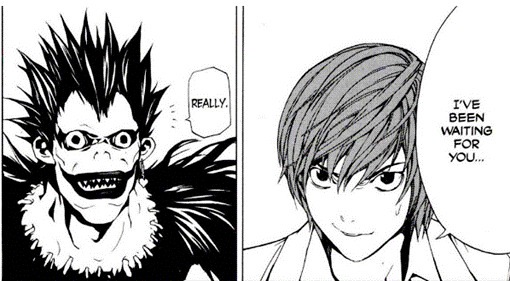

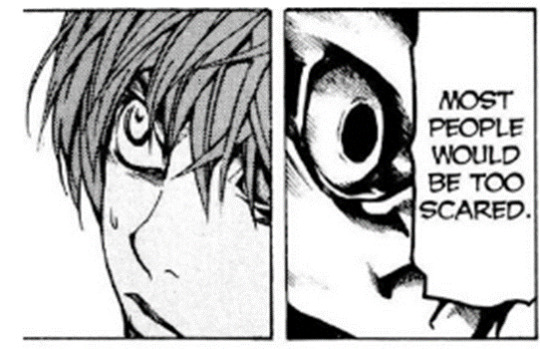

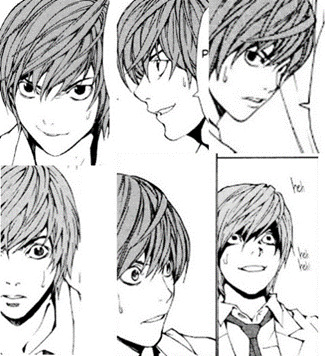

How to Read 108: A Chapter-by-Chapter Death Note Analysis

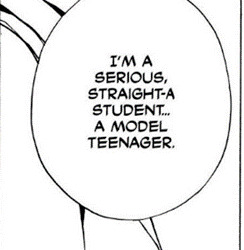

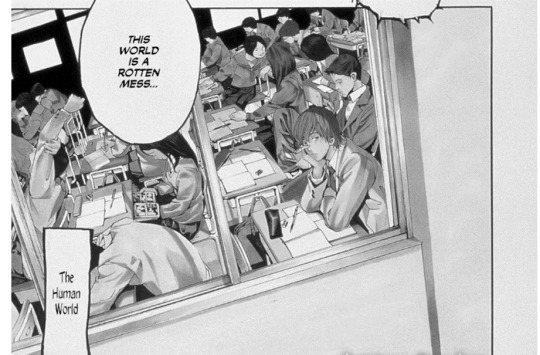

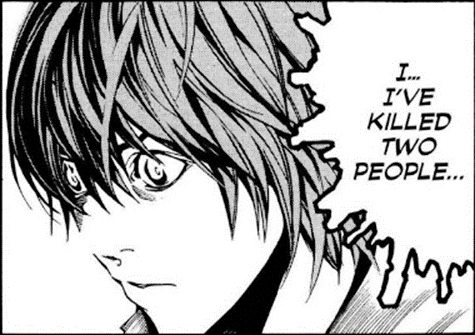

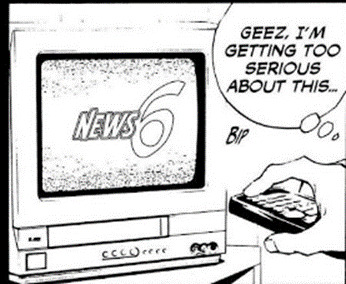

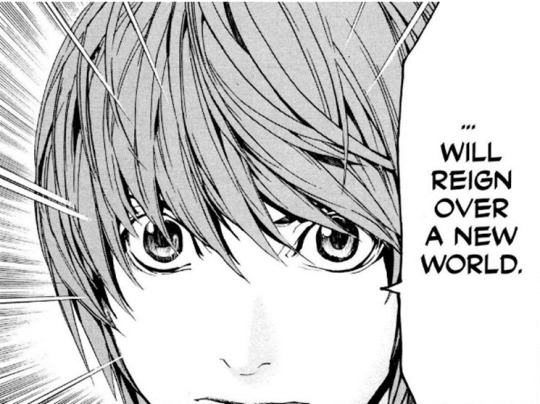

Hello everyone! Welcome back to second part of my analysis on Death Note’s first chapter, entirely dedicated to everyone’s favorite mass murderer, home boy Light Yagami!

Chapter 1: Boredom. Lilith’s Breakdown. Part 2

Establishing the protagonist:

Light and expectations

Light’s resignation

Light’s cognitive dissonance

Establishing the protagonist

In A Guide to Screenwriting Success, Stephen Duncan refers to them as the character who drives the story forward, who makes the key decisions that affect the plot, often being the one who faces the most obstacles. The OSU College of Liberal Arts says they are the character whose fate matters the most, and usually the emotional heart of the narrative.

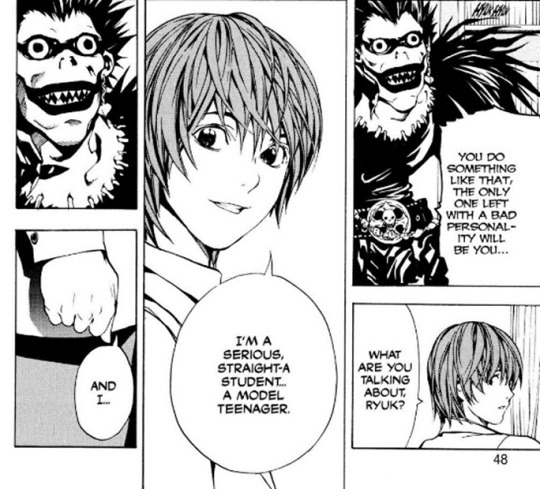

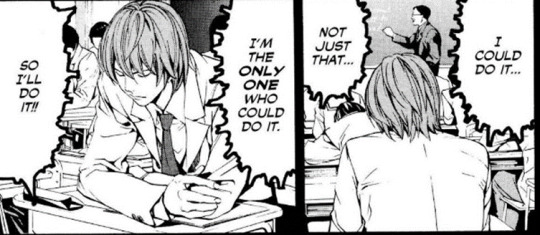

There are many definitions one can find online about what a protagonist is, the most oversimplified ones defining the protagonist under the same veil as the hero. But most of us here know that isn’t quite how it works. Still, even though we might be used to anti-hero protagonists by now (Deadpool, Saitama, Dr. House to name a few…) straight-up villain protagonists are rarer to come by, and, most specially, they usually don’t come by in the form of a teenager--or look anything like the guy in the picture above-- which is perhaps the main thing that makes Light stand out in a sea of manga MC’s and remain culturally relevant.

Light is a blueprint of his kind, becoming the point of comparison for other animanga protagonists that fall through a moral decline. To showcase how Light differs from even his own architype, I’m going to be taking three of some of the most famous examples in media and intermittently compare them to Light Yagami in this analysis: Macbeth from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Rodion Raskolnikov from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Star War’s Anakin Skywalker.

Light and expectations:

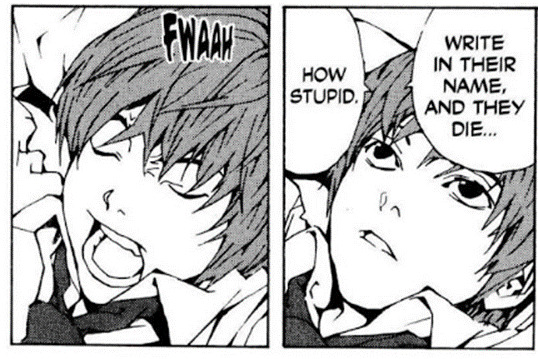

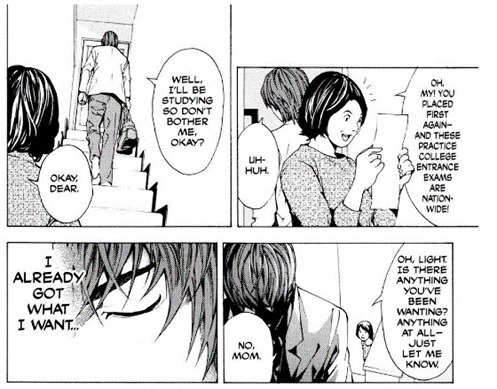

As we had seen in my previous post, we begin the story with a schoolboy disconnected from his immediate surroundings, his whole posture and expression reflecting the “boredom” that it’s the title of this chapter. His status as protagonist highlighted by the fact that he’s the only one looking directly at us. While all his classmates distract themselves with things inside the classroom (their friends, their books, their phones, or simply sleeping) Light gazes out the window, almost as if hoping that something external will offer more intrigue than the monotony of his current situation.

And he gets his wish! A notebook falls from the sky. We know what happens next. Light picks it up, as it is the only thing that’s interrupted his ennui. He’s initially unimpressed by it, although he commends whoever did it for at least committing to the bit.

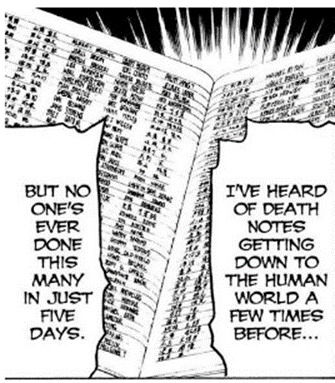

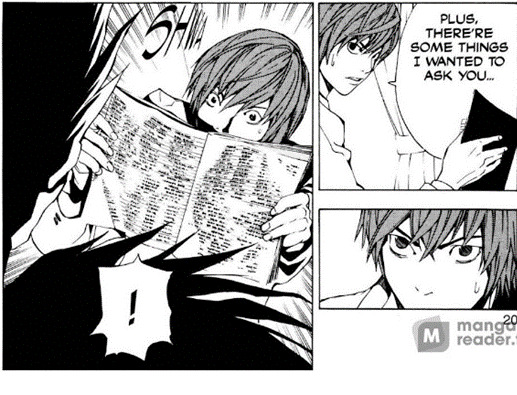

Ohba doesn't reveal the true outcome of the event right away. Instead, he makes us wait, fast-forwarding five days before slowly unfolding the details. This deliberate withholding of information is a recurring technique throughout Death Note, fueling the tension and intrigue that characterizes the manga, leaving us eager to piece the puzzle together.

But the next set of panels is what I want us to take a closer look at this chapter:

If you know anything about Japanese culture, you’re probably aware of the immense importance that academic success has on a japanese student’s life. To give some context to what’s happening here, I’ll quote Independent researcher Steve Bossy on his report Academic Pressure and Impact on Japanese Studies from 2000:

“In 1872, the Meiji government introduced a public educational system that made higher education accessible to anyone who was intelligent enough to qualify. (…) The entrance examination became the sole instrument by which all students were measured. Tokyo University became the pinnacle of academic achievement and the gateway to future success. Only the most intelligent students were admitted and upon graduation were rewarded with the best jobs. (…) The university entrance examination is the gatekeeper that provides access to and ultimately determines students' future success and status. The university that a student attends is most often the sole criterion that employers consider in their decision to hire a potential candidate.”

It’s no wonder, then, that Light’s mom has been eagerly waiting for his results on the practice exam for this life-determining test. Although we have to take into account, Sachiko says he has placed first again, so his parents are pretty used to his academic success, and Sachiko was just eager for confirmation on her son’s competence. Light is so used to this by now he does not demonstrate any pride or enthusiasm about having placed first nationally on the practice test for what is arguably the most important exam of his life. Perhaps he might have, were it not for the much more significant matter occupying his mind at the moment, though I doubt it. As we’ve already firmly established: Light is bored.

So, we have already identified one expectation Light has: he is presumed to excel academically. By Japanese society standards, this is a promise his parents see of his successful future.

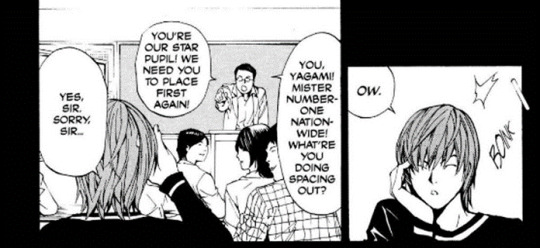

This is then reinforced by what his cram schoolteacher is shown to say in the flash-back: Light wasn’t just Japan’s number one in that sole mock test, he is already Japan’s number one student.

We can then add a new expectation:

Light is expected to keep his place as top nation-wide student and elevate the standing of the schools he attends.

Light doesn’t seem to find this to be such a difficult task though, considering the nonchalant way he brings the results to his mother. He is assured to attend the most prestigious university of the country, so then why, we may ask, does he even attend a prep school in the first place?

We can find the answer here:

In Japan, it is common for students to attend supplementary classes due to the intense competition within the education system and the critical significance of the entrance exam. So even top students like Light would be expected to attend these types of schools to give themselves an edge. Or as Light puts it: Serious, straight-A, model teenagers. This is who Light is—what he expects of himself and what everyone else expects of him: to embody the ideal of what a Japanese boy should be, to serve as a model others look up to, the standard by which they should shape themselves. Academically focused, respectful of authority, socially responsible, and attuned to societal norms.

Light’s resignation:

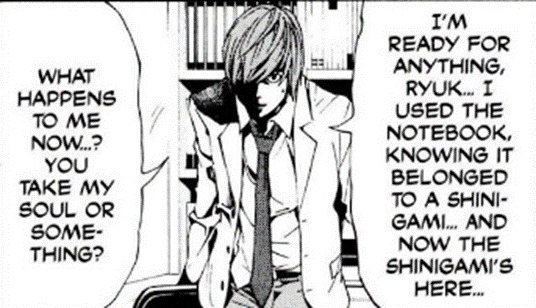

Now that we have established who Light Yagami is, let’s examine more of his initial thought process when presented with the seemingly impossible reality that the random notebook that fell from the sky is, in fact, a supernatural murder weapon.

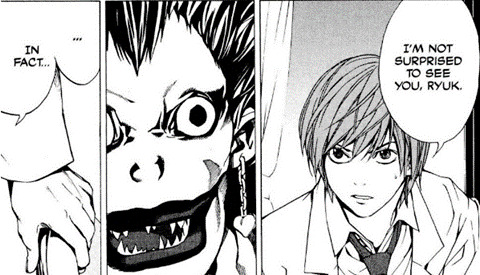

As previously noted, we don’t immediately learn about Light’s reaction to his discovery. Instead we meet him again after he’s had five days to process his experience. Then Ryuk, whom we’ve already met, shows his rather unpleasant face to an unexpecting Light, and scares the pants out of the boy.

Or so it seems.

Despite the initial scare, Light has had the foresight to attribute the notebook to a Shinigami, and supposedly had been waiting for them to show up. Light, at this point, had fully accepted the supernatural explanation, and braved with a resolved face whatever consequence it might bring.

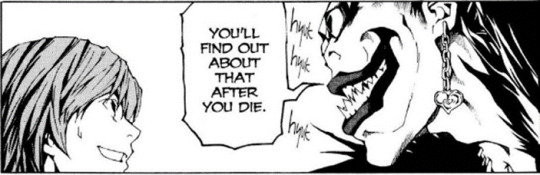

But how did Light recognize the connection to a Shinigami, and what does that mean in Japanese culture? The evolution of the concept of death is a fascinating subject, and while I recommend further reading on the topic (such as this article), to summarize: Shinigami are said to be the Japanese Grim Reaper, a relatively recent addition to their folklore, much as the Grim Reaper is for the West, and it was produced as a result of the increased interaction of these two cultures. A difference is that, traditionally, they are less seen as harvesters of souls but as creatures who ensure the smooth running of the cycle of life, performing their duty without malice and remaining morally neutral.

The Shinigami in Death Note are a fusion of these traditional Japanese beliefs and Western, particularly Christian, cautionary tales. This blending of cultural influences is a prominent theme throughout the manga (and anime), which I will explore in more detail in future entries.

But let’s go back to our protagonist. While both the Western Grim Reaper and the Shinigami ultimately bring death, Light doesn’t seem daunted by this prospect. This raises an important question: Did he have a plan to convince a literal god like Ryuk to spare him, or was he content with having made a difference, however brief? As Ryuk points out:

Ryuk, a timeless entity for all we know, singles Light out among what could be centuries of Death Note users. This continues to drive the point for the audience of Light being an extraordinary individual, now not just by his intelligence, but by his adamant determination.

However, Light’s apparent perfect composure in this scene is not entirely genuine. He is sweating profusely through this whole interaction--something that we will rarely see from him in the rest of the story. It makes sense, for its his life at stake here. But it gives us an insight into Light’s ability to suppress his natural human emotions in favor of retaining a sense of dominance and control. At this point, Light really cannot have any idea of what awaits him, or how to bargain with a being like Ryuk, yet he is intent on directing the exchange in his own terms. He even has a prepared Q&A:

I know the dramatic way in which Light swooshes open the notebook is sort of hilarious, but upon re-read, it made me think further upon this display with Ryuk. We know Light thought it wasn’t chance but choice that made Ryuk give him the Death Note, so did he want to demonstrate his worthiness to the Shinigami? His fearlessness? Did he have a whole speech planned on why he should be allowed to keep using the Death Note? After all, we learn seconds later that he had already formed his long-term plan of ruling the world, so did he plan to offer his soul, in pure Faustian manner, for the chance to wield the Shinigami’s power?

In the end, Light learns that there is nothing he has to offer—no bargain to be made. Instead, the conditions of the Death Note say he will experience fear and torment (which he has already done), that Ryuk will write his name when he dies (which results in the same thing) and that he can go to neither heaven nor hell.

This last one could be considered the greatest sacrifice, upon first read. But it is also a pretty neutral consequence that doesn’t promise reward nor suffering. Of course, it isn’t until the final chapter that we learn it isn’t really a sacrifice, as every other human shares the same fate.

Hence Light’s ecstatic look.

There is then a subversion to Christian narratives by keeping Ryuk’s role neither malevolent nor benevolent. He does not actively tempt Light to keep using the notebook, and even gives him a way out by offering the option of giving it to another human if he doesn’t want it. He has no interest in convincing Light of anything. This is similar to the role of the three witches in Macbeth, who instigate the narrative by sharing a prophecy, but do not manipulate or coerce Macbeth into taking any specific action. However, a key difference in the start of this story and that of Macbeth’s is the idea of destiny. Ryuk mocks Light for believing himself special, in contrast to the witches assuring that Macbeth would be a King. Light's confidence in his potential to rule the world is entirely self-driven, rather than being shaped by prophecy or fate.

Light’s cognitive dissonance:

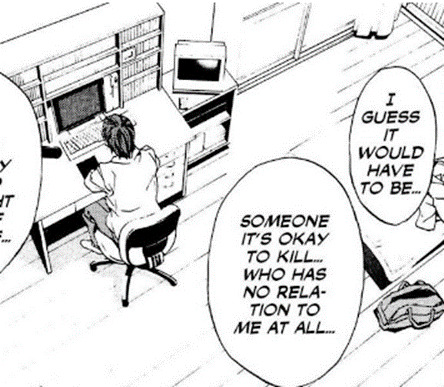

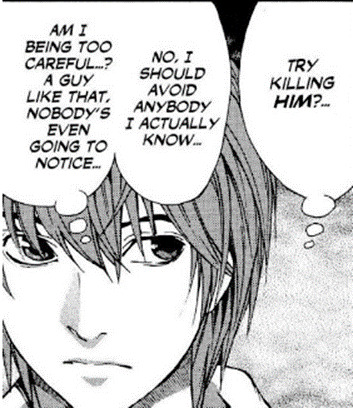

Ah, we’re finally at the pivotal moment of this first chapter. The moment that will define Light’s character for us moving forward.

So finally, after Light’s interesting conversation with Ryuk we are thrown back into the flashback that explains how he came to write all those names. The events go as follows: Light was bored, so he decided to write a name on the strange thing he brought home-- just for the sake of it. Despite mostly believing the notebook to be a prank in bad taste, as a strategic thinker, he immediately envisions possible scenarios where it could be real and plans his actions accordingly. He even berates himself for this:

But of course, the Death Note works, exactly as the instructions said.

Up until this point, Light’s actions could be entirely written off as an accident. Kind of like a child shooting a gun because they can’t discern the danger of it. But the event is so monumental, so outside of normal bounds that Light’s young and curious mind cannot simply leave it be and risk another murder. He needs answers and he needs answers now.

Light is fully aware that his actions are socially reprehensible, which would explain why he decides to continue acting by himself. Not to mention the ridicule, too, were he to hand the notebook to the police and it turned out to have been just a coincidence. And Light Yagami is not socially reprehensible and he is not ridiculous. But there is something else, too.

Light Yagami feels detached and high above the world.

It’s natural, as he literally is above his peers in at least the standard by which they are more strictly measured. In a culture where academic achievement is synonymous with social value, Light’s intellectual superiority is reinforced by his position as the model student, but he is also a 17-year-old with a skewed sense of long-term consequences and proportionality, reacting with his amygdala to his immediate environment instead of keeping on with the cool rationality he believes himself to possess. An example of this is when he considers killing one of his fellow classmates for bullying and coercion. A rather minor offense when compared to the criminals Kira would first execute, and directly contradicting the first precaution he’d already thought for himself: to not kill anyone directly associated with him.

But then he conveniently finds a perfect target, another one that he can justify to himself in the context of preventing a heinous crime.

When the Death Note works once again, it finally confirms Light as a murderer, and this is when the cognitive dissonance takes place.

In psychology, cognitive dissonance is a mental conflict that occurs when your beliefs don’t line up with your actions. This discomfort motivates individuals to reduce the inconsistency, usually by changing their believes, justifying their actions, or minimizing their importance.

Light’s cognitive dissonance almost makes him wretch, makes him question himself and consider throwing away the Death Note, which he refers to as an ‘evil thing’.

But he begins to resolve this dissonance by reframing his believes in order to justify the new image of himself as a murderer. Light’s inner conflict plays out over at least a day, during which his conscious mental battle is not whether what he did was justified, but whether or not he will be able to take on the role that would justify it.

In the end, if he doesn’t take the role of a vigilante, he would have to face the breaking of his self-schema as a moral and upstanding citizen. But the decision to continue killing would also transform him into something else. This conflict between morality and identity is so strong those first few days, that Light admits to having persistent nightmares and loses 10 pounds in 5 days. But ultimarely, the dissonance is resolved with a perfect, if delusional and self-aggrandizing, moral justification: Not only is it right to become the world’s judge and executioner, but he is the only one capable of doing so.

An extraordinary cognitive re-structuring and self-deception in a relatively short amount of time. But then again, we have already reiterated throughout this meta that Light is not an ordinary individual.

And who better, honestly, to carry us through this particular story? What are the limits of these character’s self-justification? What are the consequences of a God’s power in the hands of a mere human? And what happens when a brilliant mind has to contest with a teenager’s inflated ego?

I wasn’t expecting to have this much to say about the first chapter, I’m looking at the page count of this document with a bit of terror, honestly, but it just goes to show how strongly Death Note manages to establish its main themes from its opening and all the questions it leaves the reader with, inviting us to take part of this unconventional psychological thriller.

If you read up until this point kudos to you and I hope you enjoyed my brain’s rambling, I would love to hear your thoughts and feedback. I don’t know if next entries are going to be this long, but I am enjoying finding new things to ponder about this series, that I hadn’t even thought about after 5 years of being a fan!

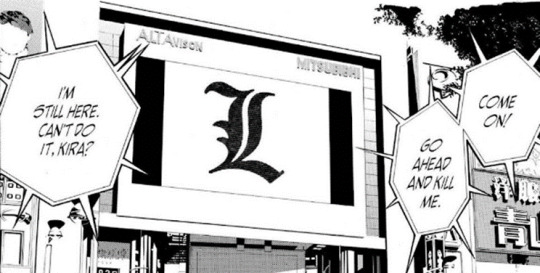

Next entry! Chapter 2: L. Lilith’s Breakdown

Previous entry: Chapter 1: Boredom. Lilith’s Breakdown. Part 1

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

confession time: any time I see a ML described as "green flag loser" I want to barf a little into a bag and peace out.

I get that this is appealing to a number of people but no thank you.

First of all, I hate the green flag/red flag fixation - not only is it ridiculously reductive (and completely pointless when applied to fictional characters as opposed to real life situations. Macbeth was a red flag and so was Raskolnikov and Melmoth the Wanderer and and and. OK, fine, and now what in terms of next steps and why does it matter?) but it is also making me think you are discussing Gaddafi's Libya versus the USSR.

Secondly, loser is not appealing to me. I don't mind someone being bad at something/clumsy/etc if it makes sense for the narrative but I cannot say I find that quality specifically sexy. The whole "pathetic wet meow meow" phenomenon has clearly passed me by.

In conclusion (because rants, like all good things, come in threes), at least the way I see it used in drama fandom, any time those terms are used, you know there is a great chance of a couple where ML is obsessed with FL for no good reason and seems to have no life and dreams beside her while she cannot be too bothered, like an inverse of those Victorian novels where heroine was a beacon of angelic purity and devotion, existing for the hero (who had an actual story) and so 2-D, she'd disappear if she stood sideways. I am fine with (and even pretty into - I love dysfunction) narratives where one half is obsessed with the other half who is much less invested, provided it's written well enough to explain why this is so (see Something Happened in Bali or Love and Redemption for example), but those types of narratives I am complaining about never bother with explanations - it is because it is, have your wish fulfillment and like it! Except I don't.

end rant.

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you use dostoevsky’s real work to analyze his character or is it solely from bsd canon? and if not, how do you feel about people using the actual writers as inspiration for headcanons and stuff? cause i think it’s really cute and creative but sometimes it breaks the immersion and i sit there ashamed—reminded that these were real people. especially when they come up in college. but to be fair, the characterization canonically is so much worse when immersion gets broken. when you think about it, like how osamu dazai, the real person, once attempted double suicide with a woman and he was obviously unsuccessful but the woman was. and that’s one of osamu dazai, the character’s, main gags. this was kind of a ramble and kind of irrelevant to my original question lmao sorry

First of all, thank you so much for bringing this up!!!♥️ I’m truly grateful for this request —I’ve been wanting to write about this for a long time, my dear.♥️

I'm solely using BSD canon events, such as the manga, the anime, interviews, BSD guidebooks, and other canon materials like the BSD letters that were published a couple of months ago.

I don’t associate the real authors with the BSD characters because, first, it’s very disrespectful. Second, while you can definitely understand the motives of the BSD characters better by reading each author's works—since each one has a unique style and philosophy—there’s really nothing to associate.

The BSD characters are interpretations of certain works by those authors, not the authors themselves.

For example, if Fyodor were truly interpreted as Dostoevsky, he would have been a much warmer person with deep vulnerability. Dostoevsky was likely an INFJ (which might help explain it; that’s my type, and... you know how I am), whereas Fyodor from BSD is an INTJ, similar to Raskolnikov from Crime and Punishment.

I could write a detailed analysis on this topic, but I currently have many requests and limited time. I’ll make sure to address it once I’ve worked through the current requests. Thank you for your understanding (because I believe that this is what you initially wanted)!♥️

#bsd fyodor#bungou stray dogs fyodor#fyodor dostoevsky#fyodor dostoyevsky bsd#fyodor x reader#bungo stray dogs x reader#bungou stray dogs#fyodor x you#yandere bsd#bsd#bungo stray dogs dazai#bsd dazai#bungou stray dogs chuuya#dazai x reader#bsd chuuya#dazai x you#bungou stray dogs dazai#dazai#bungo stray dogs chuuya#chuuya nakahara#bsd analysis

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dostoevsky knew a lot, but not everything. For example, he thought that if you kill a person, you will become Raskolnikov. And we now know that you can kill five, ten, a hundred people and go to the theater in the evening.

Anna Akhmatova

#anna akhmatova#dostoevksy#fyodor dostoevsky#russian poetry#russian classics#russian literature#poetry#poetic#poem#original poem#spilled poetry#writers and poets#poems and poetry#poems and quotes#beautiful quote#book quote#quotes#books#old literature#literature#book quotes#quoteoftheday#life quote#bookworm#books & libraries#poetsandwriters#love poems#spilled thoughts#spilled ink#spilled words

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

Raskolnikov: I know a lot about criminals and the criminal mindset. For example, one of the most frequent things criminals do that makes them get caught is return to the scene of their crime.

Raskolnikov: So obviously, I returned to the scene of the crime.

#rodya is the worst criminal#author: dostoevsky#ruslit#russian literature#book: crime and punishment#character: rodion raskolnikov#crime and punishment#russian classics

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Design Choices for Raskolnikov's Pony Version

I got a pretty good amount of people wanting to see why I chose certain designs for my version of ponified Raskolnikov as well as some headcanons I had. So here it is. Just as a refresher. I’ll put the reference sheet below.

Raskolnikov's reference sheet

The first thing I’d like to mention is that my pony version of Raskolnikov is, of course, Taratorkin’s version of Raskolnikov which I think is pretty obvious given my account. However, I’d like to mention that because it’s what inspired his species. I’ve seen many others make him either a unicorn or earth pony, both of which are very good design choices as well, but I went strictly on vibe. To me, different portrayals of Raskolnikov give different feelings of what species he would be. For example, Vladimir Koshevoy’s version looks like he would be a unicorn (for me) while Georgy Taratrokin’s looks like he would be a pegasus.

When I design characters, especially ponies, I love to make them very unique and stand out. It was a bit harder to do many unique twists with Raskolnikov since he’s already an established character but I still added some things. The first thing isn’t that unique but it makes him stand out from the crowd. In the book, he’s described as being tall with Taratorkin’s version making him stand at 6 '3 ft. 6 ‘3 today is still much taller than the average male but especially in the time period the book takes place, therefore, I made my version have a much taller stature than an average pony. I also did this because it increases the intimidation effect by a significant amount, with him towering over everyone.

Height comparison of Raskolnikov and an average pony

Because of his size, unique additions, and for headcanon reasons, I also decided to give him very large wings. When I design pegasi, I always love to try to have different flight groups with categories ranging from flight imitating commercial aircraft to flight imitating species of animals. To me, Raskolnikov doesn’t give the vibe of being a fast flier or one who would even enjoy large speeds so I gave him large wings that would imitate that of a large bird, being able to fly for longer periods of time at slower speeds rather than a short time with large speeds. But the headcanons in the next post will explain more about that.

When it comes to his color palette, I stuck to a very monotone scheme. The 1970 Soviet adaptation is in black and white, which was done deliberately. However, this doesn’t mean that everyone would be black and white. To me, Raskolnikov looks like he’d have a dark color scheme while someone like Razumikhin would have more colors. Raskolnikov can appear scary but is also an attractive figure, the same way that dark colors can be seen as scary or beautiful depending on who’s looking.

Going back to unique twists, I had sort of an AU when I was younger where there was a secret species of ponies that was driven out from where we usually see in the show and erased from all history books but one. So they’re now considered a myth rather than real, but it’s a bit too complex from this post to go into detail but one important thing to note is that they’re identifiable by markings on their body. I chose yellow since it’s a color that showed up in the book and which I feel matches Raskolnikov very well. (More about details of the markings in the headcanon post).

A small note and reminder is that the scarring on his wing and shoulder is in fact from the fire that was mentioned at the end of the book. (More on this in the headcanon post).

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crime and Punishment: Part 1 Analysis (Spoilers !!)

Characters:

Rodion Raskolnikov: 23 years old; ex student living in St. Petersburg; currently unemployed and very behind on rent; kind of a shut in

Alyona Ivanovna: pawn broker; capricious; undervalues the items brought to her; is abusive toward her younger half-sister; very rich

Lizaveta Ivanovna: younger half sister of Alyona Ivanovna; intellectually disabled; very "agreeable and uncomplaining" due to her disability and is pregnant often; cooks and cleans her sister's home; makes clothes; and cleans other's homes for a fee; gives all of her money to Alyona Ivanovna

Semyon Marmeladov: councilor; severe alcoholic; married to Katerina Ivanovna; was sober for one year but fired after drinking again; when the family moved and he found a new job, he was fired again; recently found his current job after begging a man for the position; after getting paid he took the money and spent it on alcohol and hasn't been home for five days; almost brags about his incompetence and how much it is destroying his wife, daughter, and step children

Katerina Ivanovna: second wife of Marmeladov; has three children from her previous marriage; sick; married Marmeladov "weeping and sobbing and wringing her hands" because she had nowhere else to go after her first husband died

Sonya Marmeladova: Marmeladov's daughter from his first wife; seems intelligent but was not able to make money doing handiwork and was bullied into prostitution by her step mother so that she could provide for the family

Nastasya: servant at the place Raskolnikov rents from; she seems to genuinely care about Raskolnikov, especially when he's sick

Praskovya Pavlovna: Raskolnikov's landlord; allegedly wants to get the police to evict him because he does not pay rent

Pulcheria Raskolnikov: Rodion's mother who sends him money to live off of, more so now that he has dropped out of university and stopped giving lessons for money: lives away from St. Petersburg, probably from the area the family is all originally from

Dunya Raskolnikov: Rodion's sister: younger than him: was a governess but the position was taken from her when the man of the household, Mr. Svidrigailov, kept trying to get her to have an affair with him and his wife saw; her reputation was ruined by Marfa Petrovna, his wife, and she and her mother were treated poorly by others; her reputation was saved when Mr. Svidrigailov told the truth and Marfa Petrovna's distant relative found out about Dunya through her story; the relative, Pyotr Luzhin, visited Dunya and Pulcheria and proposed to Dunya, which she agreed to; does not love Mr. Luzhin

Mr. Svidrigailov: the man who tried to preposition Dunya into an affair

Marfa Petrovna: wife of Mr. Svidrigailov; tarnished Dunya's reputation and kicked her out of their home after she found her husband trying to convince Dunya to be in a relationship with him; distant relative of Pyotr Luzhin

Pyotr Luzhin: 45 years old; relative of Marfa Petrovna, who told him about Dunya Raskolnikov; proposed to her the day after they met; arrogant; does not love Dunya; is open to meeting Raskolnikov and giving him a job at his business

Razumikhin: a former friend of Raskolnikov's from university; cheerful; friendly; well loved by others; physically strong; also left university for the time being

Themes:

Women Sacrificing Themselves to Save the Men They Love: seen so far in Sonya Marmeladova literally selling herself to provide for her father and her stepfamily, and Dunya Raskolnikov becoming, as Raskolnikov put it, "Mr. Luzhin's lawful concubine" to provide for her family, but mostly her brother; also, kind of seen in Lizaveta Ivanovna, although she does not sacrifice herself for a man, but her sister

Poverty: almost every character lives in poverty to some degree so far, besides Mr. Luzhin, Alyona Ivanovna and the Svidrigilovs, all for various reasons; for example, I believe Raskolnikov and Marmeladov are very different characters, but they are similar in the sense that they both rely on their female relatives to provide for them currently in the novel. There are other characters like Sonya, Lizaveta, Dunya, and Pulcheria who live in poverty because they give all or most of their money to someone else. There is also Katerina Ivanovna, who is ill and has to take care of her three young children, as cruel as she may be to Sonya. Razumikhin apparently had to leave university like Raskolnikov due to financial struggles, but we have not been told why

Morality of Criminality: It is revealed that the novel is asking us a question about crime when we hear Raskolnikov's reason for murdering Alyona Ivanovna: is one death worth it if it saves thousands of other lives? Raskolnikov believes so, but his crime goes wrong, and he ends up having to murder Lizaveta as well when he gets to their home too late, and she gets home before he can leave. Now he believes he has committed a crime, whereas before he thought that Alyona's death was a net positive for society. I wonder how his opinion on this will change as he processes what he has done or if the book will leave it up to us to decide for ourselves Christianity: during Marmeladov's story about his life he sort of compares himself to Christ, saying he should be crucified, etc. However, I believe Sonya is the more Christ-like figure in their dynamic in the way that she sacrifices herself for the greater good of her loved ones

Memorable Quotes:

"On that day He will come and ask, 'Where is the daughter who gave herself for a wicked and consumptive stepmother, for a stranger's little children? Where is the daughter who pitied her earthly father, a foul drunkard, not shrinking from his beastliness?' And He will say, 'Come! I have already forgiven you once…I have forgiven you once…And now, too, your many sins are forgiven, for you have loved much…'" (p. 41)

"'…It's clear that the one who gets first notice, the one who stands in the forefront, is none other than Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov. Oh, yes, of course, his happiness can be arranged, he can be kept at the university, made a partner in the office, his whole fate can be secured; maybe later he'll be rich, honored, respected, and perhaps he'll even end his life a famous man! And mother? But we're talking about Rodya, precious Rodya, her firstborn! How can she not sacrifice even such a daughter for the sake of such a firstborn son! Oh, dear and unjust hearts! Worse still, for this we might not even refuse Sonechka's lot! Sonechka, Sonechka Marmeladov, eternal Sonechka, as long as the world stands! But the sacrifice, have the two of you taken full measure of the sacrifice? Is it right? Are you strong enough? Is it any use? Is it reasonable? Do you know, Dunechka, that Sonechka's lot is in no way worse than yours with Mr. Luzhin?…" (p. 62-63)

"His thoughts were distracted…And generally it was painful for him at that moment to think about anything at all. He would have liked to become totally oblivious, oblivious of everything, and then wake up and start totally anew…" (p. 69)

"'…what do you think, wouldn't thousands of good deeds make up for one tiny little crime?…'" (p. 86)

#crime and punishment#book blog#bookish#bookblr#books#19th century literature#booklr#books and reading#classic lit#classic literature#russian literature#dostoevksy#fyodor dostoevsky#russian lit#russia#dostoevsky quotes#book quotes#classic lit quotes#I'm doing it in parts so I have stuff to post and also so I don't have to write as much at the end lol#I'm unsure of if certain words on here will get the post flagged but I hope not?#the post is educational?#idk man

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having an absolutely splendid time with all my translations of Crime and Punishment, buuuuut

When I was trying to decide which to buy, I noticed that a lot of people made their case very vaguely ("it feels most authentic," "I like the translator's philosophy," etc) without any key examples

So I've decided to take my translations and compare certain words and phrases I find interesting or significant! If anyone has a copy of Pevear and Volkhonsky, I would LOVE if you could chime in!

(All quotes except Garnett transcribed from physical copies by me; all errors are my own)

Worth noting!!!! I love this so much that I want to point it out!!!! The Katz translation provides context with FOOTNOTES!!!! Instead of ENDNOTES!!!! I'M SO PLEASED!!!!!!!

Axe

Garnett: Axe

McDuff: Axe

Magarshack: Hatchett

Katz: Axe

Marfa Petrovna

Garnett: Marfa Petrovna Svidrigaïlov

McDuff: Marfa Petrovna Svidrigailov

Magarshack: Mrs Svidrigaylov*

Katz: Marfa Petrovna Svidrigaylov

*Magarshack does this with every character referred to by first name, regardless of gender; Pyotr (or here, Peter) Petrovich Luzhin is also referred to as "Mr Luzhin" in instances where other translations use "Pyotr Petrovich." I thought it was odd, which is why I included it.

Rodya

Garnett: Rodya

McDuff: Rodya

Magarshack: Roddy

Katz: Rodya

This little exchange bc Magarshack's translation made me laugh

Garnett:

“I don’t want it,” said Raskolnikov, pushing away the pen. “Not want it?” “I won’t sign it.” “How the devil can you do without signing it?” “I don’t want... the money.”

McDuff:

"I don't want it," Raskolnikov said, pushing the pen away.

"What on earth are you talking about?"

"I won't sign."

"The devil, man, but you've got to!"

"I don't want... the money..."

Magarshack:

"Don't want to," said Raskolnikov, pushing away the pen.

"Don't want what?"

"Shan't sign."

"Damn you, man, but they want your signature!"

"I don't want — the money."

Katz:

"There's no need," said Raskolnikov, pushing the pen away.

"No need for what?" asked Razumikhin.

"I won't sign it."

"What the hell? How can he do it without a signature?"

"I don't need any... money..."

Argument with Luzhin

Garnett:

“I tell you what,” cried Raskolnikov, raising himself on his pillow and fixing his piercing, glittering eyes upon him, “I tell you what.” “What?” Luzhin stood still, waiting with a defiant and offended face. Silence lasted for some seconds. “Why, if ever again... you dare to mention a single word... about my mother... I shall send you flying downstairs!”

"What's the matter with you?" cried Razumihin.

McDuff:

"Do you want to know something?" Raskolnikov exclaimed, raising himself on his pillow and fixing him with a penetrating, glittering stare. "Do you?"

"Well, sir?" Luzhin stood still and waited with an offended, challenging look on his face. The silence lasted for several seconds.

"If you so much as dare... to say another single word about my mother... I'll knock you head over heels downstairs!"

"Hey, what's got into you?" cried Razumikhin.

Magarshack:

"Do you know what?" Raskolnikov cried, raising himself on the pillow and staring at Mr Luzhin with glittering, piercing eyes. "Do you know what?"

"What, sir?" Luzhin stopped, and waited with an offended and challenging air.

For a few seconds there was silence.

"If you dare to say another word about — about my mother, I'll — I'll kick you down the stairs!"

"What's the matter with you?" cried Razumikhin.

Katz:

"Do you know what?" cried Raskolnikov, raising himself on his pillow and staring at him with a piercing, flashing glance. "Do you know what?"

"What, sir?" Luzhin paused and waited with an offended and challenging look. Several seconds passed in silence.

"If you dare once again... utter even one word... about my mother... I will throw you down the stairs head over heels!"

"What's the matter with you?" cried Razumikhin.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Crime and Punishment: Short Bungou Stray Dogs Analysis

Finally finished Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky. i might do a post talking about my actual thoughts on the book, but not right now because I'm INSTEAD gonna talk about BSD Fyodor because, if I'm gonna be honest, a large part of the reason I read this book was to see if I could get an insight on what his ability could be (obviously I also read it because I know it's an extremely influential book to the psychological thriller literature genre, and it's made me want to read more of his books because I am absolutely entranced by his writing style).

SPOILERS: This book did NOT give me a single damn clue to Fyodor's ability.

However, I do have a better understanding of why Asagiri chose to write Fyodor in that specific way, with the added effect of making Fyodor much more understandable. I have a better appreciation, I think, for Asagiri's character writing. Let me explain:

The large, overarching theme of C&P is the idea that some people are naturally born with the right to kill. That is, people are naturally born into two categories: "Ordinary" and "Extraordinary". The majority of the population falls into the former - they live their lives in submission to the law and to those above them. In essence, they do not have the "right to kill"; they are otherwise overcome with guilt, regret, or simply caught for their wrongdoings.

The latter category has very few people in it, and for a simple reason - they are the ones who are, essentially, above the law, and therefore, the lawmakers. They are the ones who lead the revolutions, sit on the throne, and most importantly, kill when they need to kill and do not hesitate to "step" over their crimes as nothing more than the necessity to power. They are not caught. In fact, they are hailed as the greatest leaders. Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and his most constantly referred example, Napoleon. These are the born with the "right to kill".

The main character, Raskolnikov (of whom I will be calling the affection Rodya because I am NOT spelling his name over and over again), believes himself to be a "Napolean". Rodya is the one who came up with this theory in the book, after all. However, he finds out, near the end, after several blunders and mental breaks, that he is not one of the people who can "step" over their crimes. He hesitated before killing his target. His guilt for his two murders sent him into a feverish state for days on end. He walked to the police station to confess his crimes a million times before finding some reason, right before he was meant to do it, to chicken out and continue living life under this ever-evolving notion that he was sorely mistaken about himself. Rodya is not the "Napolean" he thought he was born to be.

How does this relate to the Bungou Stray Dogs character? I believe that Fyodor is, essentially, the embodiment of the "right to kill". He is everything that Rodya thought he was, which is an excellent analysis on the part of Asagiri. One of the first things Fyodor does is kill Ace, then a relatively innocent child, Karma. He does this without blinking, without a hint of remorse, and proceeds with his day. He knows that this is his right, that he is the one above others, that he can kill and he cannot be caught for it. He claims to have mastered and tamed his own ability. Why? Because he is the "Extraordinary."

Another theme that I find quite intriguing is religion. In truth, it really isn't that prevalent (though there are a great many Biblical quotations and references throughout) until the last part, Part 6, of Crime and Punishment. Rodya has a near-constant epiphany with religious belief, even at one point stating, point-blank and in irritation, that God isn't real and He certainly isn't helping anyone in the mortal plane. He oscillates between claiming that the "Devil" forced him to kill, to saying that believers are frantic and stupid, then to kissing the dirty ground in repentance for his crimes. He state of mind ends in that repentance state, a supposed believer and eager to start his life anew.

To make Fyodor a devoted believer in God, with a set viewpoint and acting as an executor of God's will, is, once again, an excellent choice. Rodya's irritation and inner turmoil were one of the many reasons why he failed miserably in maintaining the secret of his crimes. Fyodor is none of those things: he is calm, cool, collected, and set in his ways. Interestingly, in Crime and Punishment, the vilest character also seems to have no particular issues with religion himself. And he, for the most part, gets away with his heinous crimes completely. This battle of belief, and relating it to God, provides a healthy insight to why Fyodor has obtained the "right to kill", versus Rodya, who was born "Ordinary."

The last point I want to seriously touch on is less about Crime and Punishment and more about the author himself. However, I did learn about this through reading the translator's notes (the translation I read is by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, Second Edition (2021), Vintage Classics). Dostoevsky was hugely indebted to Nikolai Gogol as a successor to Gogol's ingenious literary developments in "fantastical realism" and satire. Dostoevsky made several references to Gogol's works in C&P, and none in a critical manner. In the animanga, the roles are completely reversed; Nikolai is the one chasing after Fyodor, admiring his intellect and "ingenious" with the eventual goal of setting himself free. This idea of flipping authors' relationships on their heads is part of what makes Bungou Stray Dogs so entertaining to consume, and it takes a great deal of research and effort to be able to adjust these relationships so that they clearly reflect the real-life ones.

As for one afterthought, the name "Rats in the House of the Dead" appears to be a clever play on the Dostoevsky book Notes from the Dead House. I haven't read this book yet, but I want to (along with Notes from Underground). I'm curious to see if there is any further correlation, but I would assume not, considering the contents of the book.

NO. I did NOT find literally anything that could help me decipher Fyodor's ability. Rodya literally confesses his crime like a week and a half after he commits it. No character in this novel, nor theme, reflects whatever the h e double hockey sticks Fyodor has going on in BSD. I have theories, but they have literally nothing to do with Crime and Punishment outside of the base fact that his ability has something to do with killing (which we already knew). Woe is me. I'll get over it, I guess.

#this is really ironic for me to post this#because fyodor is like#my top 10 least favorite bsd characters#mori is at number one because literally who else would it be#idk where fyodor falls#maybe if he took a bath every once in a while he wouldn't be in the list at all#bsd fyodor#bungou stray dogs fyodor#bungou stray dogs#bsd#fyodor dostoyevsky bsd#fyodor dostoevsky#fyodor dostoyevsky#crime and punishment#bsd 113#bsd analysis#bungou stray dogs analysis#analysis#rant#bsd rant

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

(SPOILERS for The Brothers Karamazov, The Idiot, and Crime And Punishment)

Major Themes in Dostoevsky’s novels: Russia, Loneliness, Faith, Love, and Redemption

// this is rough, transcripted from an audio recording and only slightly edited. if anyone wants to talk to me about this, please do!

After finishing Crime And Punishment, Notes From Underground, The Brothers Karamazov, and The Idiot (working on Demons currently), I’ve been thinking a lot about the larger themes and concepts that tie Dostoevsky’s works together. Although many of his works are different, I’ve noticed- at least, in my interpretations- that they carry key elements which are integral to understanding and digesting his writing.

Beginning with Crime and Punishment; my first Dostoevsky, and the novel which began my odyssey into his masterful worlds. (this section may be more flawed than the others, as i’ve read it about a year ago) C&P, at its surface, is about the folly of man- inflated ego and its effects on humanity. Raskolnikov likens himself to Napoleon. He believes that he is destined for a greater cause, and he kills because of that deep desire for greatness. But it’s not difficult to grasp that he is truly nobody; he kills for no actual reason, and his crime is simply a crime of hopelessness. And he knows that, and it scares him. In fact, knowing he has no true motive scares Raskolnikov more than people realizing he’s the murderer. Dostoevsky’s characters all seem to represent certain facets of Russia. (my knowledge of Russia in Dostoevsky’s time is limited, so i apologize if I get this completely wrong..) What Raskolnikov feels while nervously roaming the lonely streets of his town is what is occuring in the minds of the Russian people as a whole. When it is concluded that Russia at the time is a lonely, confusing, morally corrupt nation, it becomes more clear how Raskolnikov connects to this greater idea. Many crave to be different, to distinguish themselves from the crowd, to prove that they are just and for a good cause, but truly- as i think Dostoevsky sees it- they’re not. And they cannot run away from that. This becomes more problematic and is heightened when they are forced by societal standards and needs to push their disillusionment down instead of being able to voice them.

Another important theme to consider is redemption and forgiveness. Raskolnikov achieves this at the end of C&P when he is put in Siberia for his crime. (important!!) This concept of forgiveness is integral to Dostoevsky’s faith, which is depicted shamelessly in many of his works. Everyone deserves pardon from their sins if they accept it- everyone is capable of it, too. Raskolnikov finding God in Siberia is extremely similar to Dostoevsky���s experience. He doesn’t shy away from embedding his own experiences into his work. Christianity is important to him. Not wholly because it’s the “correct” way to believe, but because it helps quell the loneliness and feelings of corruption which one may feel in his Russia. It provides an escape, a meaning, a love which can save and teach and inspire goodness in a world which instead inspires much evil.

In The Brothers Karamazov, you see some of the same Christian ideals. There’s Alyosha, who’s a holy beacon of light; though he’s also flawed in his own right, owing to the concept that achieving goodness is a constant pursuit. This is similar to Ivan’s journey, who has the idea that “everything is permissible,” and because of this he inadvertently causes his father’s death. Once again an act of murder on Pavel’s part with no real justification- stemming only from his own loneliness and abuse. Ivan lives a faithless life, focusing on the bad and denying god because of the very real unfairness he sees in the world around him. Though Dostoevsky allows Ivan to make his convincing case, he shows us how this view can falter and lead to only more violence and corruption. The most convincing example of Dostoevsky contending Ivan’s argument is with a scene of redemption at the end of TBK once again. Alyosha talks to a group of young boys and tells them about the importance of respect and friendship, of youthful vitality in loving freely. The children praise the Karamazov name, showing how an act of kindness can overcome the past difficulties and pain in the Karamazov family. Of course, the Karamazovs serve as a symbol for the entirety of the Russian people. Love is the savior- love for God in many cases, love for the people around you, love for the world even through its darkest moments. In a cast of extremes- an extreme athiest in Ivan, who lets his love for the world grow so hurt that it turns inro a hatred- an extreme lover of God in Alyosha, who lets his love blind him sometimes, in Smerdyakov who has never felt love and kills because of it, and an extreme obsessor over romantic love in Dimitri, which overcomes him and drives his every action, Love works in mysterious ways. It consumes the world, but there is a way to harness that love and make it into something truly good and beneficial.

Lonliness is something which blocks this love- and this ties into The Idiot. The cast of The Idiot is a cast of lonely people who find themselves constantly separated from the people around them, unable to connect because of the world which they live in that seems to breed more hatred and contempt rather than true understanding. Prince Myshkin has led his whole life essentially alone, apart from Russia due to his bad case of epilepsy (could this be a reason for his purity? Yes, probably, if we’re sticking to the idea that Russia corrupts its people) and with little outside interaction. Near the beginning of the book, Myshkin reflects on a time living in Switzerland when he started to see a lonely woman because he only wanted to lend her some companionship, not out of romantic love but out of his own great compassion to help others escape the loneliness he feels. Myshkin goes on to meet a cast of characters who, despite being (debatably, but not as physical as his illness) mentally healthy, are just as lonely as he is because Russia is, once again, a lonely place. Then there’s Nastasya, who’s been abused and sees herself as incapable of being and receiving love due to her being “tainted.” The Idiot serves as Dostoevsky’s darkest book because he does not provide redemption for Nastasya. Her loneliness has consumed her so fully and she will not allow the love into her life that she needs to survive. In the same way as Myshkin started to love the woman in Switzerland, Myshkin falls in love with Nastasya, in a wild pursuit to save her. Unfortunately, this tactic of his does not work. It actually ends up all falling apart because of jealousy. But Dostoesvky does provide a concept of a way out, though it’s less articulated- and it’s Myshkin himself. Myshkin is more of a beacon of light that Alyosha. He’s that true barrierless acceptance and childlike loving which is sparse in Russia and powerful in its capablity. By applying that Myshkin mindset to yourself, it is a way to be happy and make others feel happy aswell. But Myshkin is hurt by the people around him, who abuse him for his purity and laugh at his goodness, only because they are afraid of what they have never seen before. Dostoevsky shows (mirroring Jesus’ demise) how the Myshkin mindset ends in punishment, suffering, and injustice, because the world he lives in cannot accept that part of him. Maybe some semblance of redemption is possible, but embodying the Christian ideal and being truly authentic to your inner goodness will oftentimes lead to pain. Continue loving humanity through that. One can only hope that in the afterlife you will be rewarded. Maybe that is the ultimate redemption.

// i want to talk about A LOT more considering christianity, dostoevsky’s usage of provinces and gossip, and i’d love to be more historical in general. probably will rewrite this all when i finish demons, but this is it for now

#dostoevksy#dostoyevsky#russian literature#the idiot#the idiot dostoevsky#prince myshkin#the brothers karamazov#tbk#alyosha karamazov#lev myshkin#crime and punishment#rodion romanovich raskolnikov#rodya raskolnikov#alyosha#ivan karamazov#mitya karamazov#nastasya filippovna

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

as someone in her twenties and an astro girlie it makes sense why raskolnikov was going through all that — he was TWENTY-THREE. i don't think dostoevsky half-assed the choice of placing rodya in that age, given he's already so deliberate with the names he gives his characters.

like i'm not surprised why there's a general consensus online that 23 is a weird, freaky age to be; take raskolnikov for example — always oscillating between crippling depression or having a god complex (or experiencing both at the same time).

#bro wrote about the worst possible outcomes of someone's 12th house profection year#dostoevsky was so ahead of his time#rodya's 12h profection year beat his ass so hard#crime and punishment#fyodor dostoevsky#rodion romanovich raskolnikov#russian literature

31 notes

·

View notes