#ramiro ii of aragon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Petronila I of Aragon

(1136-1173)

She was the first fully-fledged woman queen of Aragon, with a title in her own right. Petronila came to the throne through special circumstances. Her father, Ramiro, was bishop of Barbastro-Roda when his brother, Alfonso I of Aragon, died without an heir in 1134, and left the crown to the three religious military orders. His decision was not respected: the aristocracy of Navarre elected a king of their own, restoring their independence, and the nobility of Aragon raised Ramiro to the throne. As king, he received a papal dispensation to abdicate from his monastic vows in order to secure the succession to the throne.

King Ramiro II the Monk married the daughter of the Count of Poitiers, Agnes of Aquitaine, a widow of proven fertility who had given birth to four children in her previous marriage. The expected heir to the throne was born in 1136. For first time, the destiny of Aragon fell on a girl, named Petronila. Almost since her birth, she was a key piece in the political games of the Iberian Peninsula. When Petronila was just a little over one year old, was betrothed to Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona, who was twenty-three years her senior.

King Ramiro abdicated and returned to monastic life. Queen Agnes crossed the Pyrenees again and confined herself to the Abbey of Fontevrault, where she died years later. There is no evidence that Agnes took any part in the affairs of her daughter Petronila. Except for the first few weeks of her life (without the possibility of any recollection) and entrusted to the care of a housekeeper, Petronila never saw her mother.

Her future husband refused to take charge of her education, and the girl was sent to Castile to be educated by her sister-in-law Berenguela of Barcelona, queen of Castile. In Castilian lands, King Alfonso VII wanted to marry Petronila to his son, the infante Sancho, heir of Castile. The Aragonese nobility, alarmed by this situation, met in Cortes to demand the return of the young queen to Zaragoza. Also her father, Ramiro II, threatened to abandon his monastic retreat to defend the interests of the kingdom, and his daughter. Finally, Petronila left Castile and returned to Aragonese lands.

When Petronila was fourteen, the betrothal to Ramon Berenguer IV was ratified at a wedding ceremony held in the city of Lleida. This marriage sealed the union of Aragon with the Catalan counties, so Queen Petronila has gone down in history as the mother of the Crown of Aragon.

The relationship between Ramon and Petronila was stable and fruitful, although he, with more experience and authority, played a predominant role in government affairs, she was not a submissive queen. Petronila was aware of her power as the legitimate heir to the Aragonese throne and remained firm in her role, although discreetly.

Petronila and Ramon developed a relationship of mutual respect, where trust and political collaboration prevailed over any differences. Ramon Berenguer was never king. The Count of Barcelona used the title Prince of Aragon. The marriage produced four sons and one daughter.

In the summer of 1162, when Ramon Berenguer went to Turin to meet with Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, the Count of Barcelona fell ill and died. The eldest son, Ramon, received the title of Count of Barcelona, and as he was a minor, was placed under the tutelage of Henry II of England.

Widowed at the age of 26, Petronila did not want to take a husband again and was the mistress of her own actions. Being a woman in the power was not easy. Queen Petronila faced constant scrutiny from nobles and clerics, many of whom doubted her ability to rule. For two years she ruled and administered her kingdom of Aragon. Attentive to preserve the peace and the integrity of Aragon, Petronila signed a truce with Navarre. She kept the ambitions of the local nobles in check and ensured that her son could govern without internal divisions. The marriage of her son with Sancha of Castile was one of Petronila's most important strategic moves. This marriage alliance not only strengthened ties with the powerful kingdom of Castile, but also guaranteed peace on a traditionally conflictive border. The chronicles tell us a curious conspiracy that Queen Petronila had to dominate, when an elderly gentleman claimed to be the late King Alfonso the Battler.

Her son and heir was only seven years old when Petronila abdicated in his favor. When Ramon inherited the throne from his mother, he changed his name to Alfonso II out of deference to the Aragonese. Queen Petronila died in Barcelona in October 1173. She was buried at the cathedral of the city; her tomb has been lost.

Sources:

youtube

#petronila de aragon#peronella d'aragó#spanish history#ramon berenguer iv#alfonso ii of aragon#ramiro ii of aragon

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bell of Huesca by José Casado del Alisal

#josé casado del alisal#art#spain#spanish#medieval#middle ages#ramiro ii#king#aragon#aragonese#nobles#the monk#nobility#abbey#bell#history#europe#european#herald#aragón#mediaeval#iberian peninsula#dog#dogs#hound#hounds#noblemen#architecture#archbishop

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

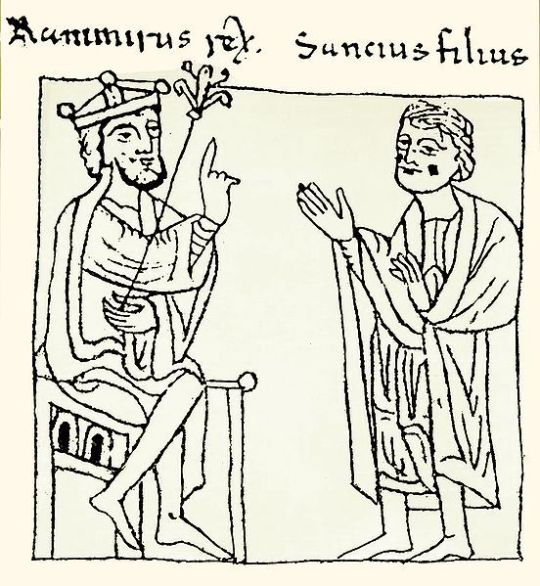

1) Ramiro I of Aragon (1006/7- 1063), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and Sancha de Aybar; with his son Sancho I of Aragon & V of Pamplona (1043-1094)

2) His wife, Ermesinda of Foix (1015 - 1049), mother of Sancho I of Aragon. Daughter of Bernard Roger de Foix and his wife Garsenda de Bigorra; and Sancha of Aragon (1045-1097), daughter of Ramiro I and Ermesinda

3) His father, Sancho III of Pamplona (992/96-1035), son of García II of Pamplona and Jimena Fernández

4) His brother, García III of Pamplona (1012-1054), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and his wife Muniadona of Castile

5) His nephew, Sancho IV of Pamplona (1039- 1076), son of García III of Pamplona and his wife Placencia of Normandy

6) His brother, Ferdinand I of Leon (1016- 1065), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and his wife Muniadona of Castile

7) His niece, Urraca of Zamora (1033-1101), daughter of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

8) His niece, Elvira of Toro (1038-1099), daughter of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

9) Sancho II of Castile (1038/1039-1072), son of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

10) Alfonso VI of Leon (1040/1041-1109), son of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

#jonsnowfortnightevent#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#ramiro i of aragon#sancho i of aragon#sancha of aragon#ermesinda of foix#sancho iii of pamplona#garcía iii of pamplona#sancho iv of pamplona#ferdinand i of leon#urraca of zamora#elvira of toro#sancho ii of castile#alfonso vi of leon#bastard kings and their families#canonjonsnow

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

José Casado del Alisal (Spanish, 1832-1886) The Legend of the Monk King, 1880 Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Traditionally known as The Bell of Huesca, this painting depicts one of the most terrifying events in the history of Medieval Spain. Ramiro II of Aragon decapitated all the noblemen who had dared to challenge his royal power, one by one. As he had promised to make a bell that would ring to reaffirm his power, he did so with the heads of the rebel noblemen. For the clapper, he used the head of the Archbishop responsible for the failed conspiracy. This painting shows the exact moment when the monarch shows his work to the rest of the court.

#José Casado del Alisal#spanish art#spanish#spain#the legend of the monk king#the bell of huesca#european history#european art#classical art#europe#european#art#fine art#fine arts#oil painting#europa#mediterranean#Aragon#medieval#medieval europe#medieval spain#espana#iberia#iberian#king#nobles#nobility#royalty#history#spanish history

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sos del Rey Católico is one of the best preserved walled towns in Spain.

Sos del Rey Católico is a historic town and municipality in the Cinco Villas comarca, province of Zaragoza, in Aragon, Spain.

Located on rocky and elevated terrain, this important border town served well as a stronghold from the year 907 when it was reclaimed by Sancho I of Pamplona.

It was incorporated in 1044 by Ramiro I into the Kingdom of Aragon.

In the year 1452, during the Navarrese Civil War, Queen Juana Enríquez de Córdoba moved to the town, then called "Sos". There she gave birth to the infante Ferdinand on March 10, 1452, who later became Ferdinand II of Aragon, one of the Catholic Monarchs. His birth added "del Rey Católico" to the name of the town, which translates as "of the Catholic King".

In 1711 it was named as the capital of the Cinco Villas

The exceptional preservation of the historic center makes a stroll around this town becomes a journey into the past highlighting the city walls, churches, Plaza de la Villa and the Palacio de los Sada, where Ferdinand was born in 1452.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queens and Princesses of the Spanish Kingdoms: Ages at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. This data set ends with the transition to Habsburg-controlled Spain.

Sancha, wife of King Fernando I of Léon; age 14 when she married Fernando in 1032 CE

Ermesinda of Bigorre, wife of King Ramiro I of Aragon; age 21 when she married Ramiro in 1036 CE

Sancha, daughter of King Ramiro I of Aragon; age 18 when she married Count Ermengol III of Urgell in 1063 CE

Constance of Burgundy, wife of King Alfonso VI of Léon & Castile; age 19 when she married Count Hugh II of Chalon in 1065 CE

Felicia of Roucy, wife of King Sancho of Aragon; age 16 when she married Sancho in 1076 CE

Agnes of Aquitaine, wife of King Pedro I of Aragon; age 14 when she married Pedro in 1086 CE

Teresa, daughter of King Alfonso VI of Léon & Castile; age 13 when she married Count Henri of Burgundy in 1093 CE

Elvira, daughter of King Alfonso VI of Léon & Castile; age 15 when she married Count Raymond IV of Toulouse in 1094 CE

Bertha, wife of King Pedro I of Aragon; age 22 when she married Pedro in 1097 CE

Elvira, daughter of King Alfonso VI of Léon & Castile; age 17 when she married King Ruggero II of Sicily in 1117 CE

Berenguela of Barcelona, wife of King Alfonso VII of Léon & Castile; age 12 when she married Alfonso in 1128 CE

Urraca, daughter of King Alfonso VII of Léon; age 11 when she married King Garcia Ramirez of Navarre in 1144 CE

Petronilla, daughter of King Ramiro II of Aragon; age 14 when she married Count Ramon Berenguer IV of Barcelona in 1150 CE

Richeza of Poland, wife of King Alfonso VII of Léon & Castile; age 12 when she married Alfonso in 1152 CE

Sancha, daughter of King Alfonso VII of Léon & Castile; age 14 when she married King Sancho VI of Navarre in 1153 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Alfonso VII of Léon & Castile; age 16 when she married King Louis VII of France in 1154 CE

Urraca of Portugal, wife of King Fernando II of Léon; age 17 when she married Fernando in 1165 CE

Eleanor of England, wife of King Alfonso VIII of Castile; age 9 when she married Alfonso in 1170 CE

Sancha of Castile, wife of King Alfonso II of Aragon; age 20 when she married Alfonso in 1174 CE

Dulce, daughter of Queen Petronilla of Aragon; age 14 when she married King Sancho I of Portugal in 1174 CE

Berenguela, daughter of King Alfonso VIII of Castile; age 7 when she married Duke Conrad II of Swabia in 1187 CE

Marie of Montpellier, wife of King Pedro II of Aragon; age 10 when she married Viscount Raymond Geoffrey II of Marseille in 1192 CE

Garsenda of Foralquier, wife of Prince Alfonso II of Aragon; age 13 when she married Alfonso in 1193 CE

Constance of Toulouse, wife King Sancho VII of Navarre; age 15 when she married Sancho in 1195 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Alfonso II of Aragon; age 19 when she married King Emeric of Hungary in 1198 CE

Blanca of Castile, daughter of King Alfonso VIII of Castile; age 12 when she married King Louis VIII of France in 1200 CE

Eleonora, daughter of King Alfonso II of Aragon; age 22 when she married Count Raymond VI of Toulouse in 1204 CE

Urraca, daughter of King Alfonso VIII of Castile; age 19 when she married King Afonso II of Portugal in 1206 CE

Mafalda of Portugal, wife of King Enrique I of Castile; age 20 when she married Enrique in 1215 CE

Sancha, daughter of King Alfonso II of Aragon; age 25 when she married Count Raymond VII of Toulouse in 1211 CE

Elisabeth of Swabia, wife of King Fernando III of Castile; age 14 when she married Fernando in 1219 CE

Eleonora of Castile, wife of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 19 when she married Jaime in 1221 CE

Berenguela, daughter of King Alfonso IX of Léon; age 20 when she married Emperor Jean I of Brienne in 1224 CE

Marguerite of Bourbon, wife of King Teobaldo I of Navarre; age 15 when she married Teobaldo in 1232 CE

Yolanda of Hungary, wife of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 20 when she married Jaime in 1235 CE

Joan of Dammartin, wife of King Fernando III of Castile; age 17 when she married Fernando in 1237 CE

Yolanda, daughter of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 13 when she married King Alfonso X of Castile in 1249 CE

Isabelle of France, wife of King Teobaldo II of Navarre; age 14 when she married Teobaldo in 1255 CE

Kristina of Norway, wife of Prince Felipe of Castile; age 24 when she married Felipe in 1258 CE

Beatriz, daughter of King Teobaldo I of Navarre; age 16 when she married Duke Hugues IV of Burgundy in 1258 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 21 when she married Prince Manuel of Castile in 1260 CE

Constanza of Sicily, wife of King Pedro III of Aragon; age 13 when she married Pedro in 1262 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Jaime I of Aragon; age 14 when she married King Louis IX of France in 1262 CE

Beatrice of Savoy, wife of Prince Manuel of Castile; age 18 when she married Pierre of Chalon in 1268 CE

Blanche of France, wife of Prince Fernando of Castile; age 16 when she married Fernando in 1269 CE

Blanche of Artois, wife of King Enrique I of Navarre; age 21 when she married Enrique in 1269 CE

Beatriz, daughter of King Alfonso X of Castile; age 17 when she married Marquis William VII of Montferrat in 1271 CE

Esclaramunda of Foix, wife of King Jaime II of Majorca; age 25 when she married Jaime in 1275 CE

Maria de Molina, wife of King Sancho IV of Castile; age 17 when she married Sancho in 1282 CE

Yolanda, daughter of King Alfonso X of Castile; age 17 when she married Diego Lopez V de Haro in 1282 CE

Juana, daughter of King Enrique I of Navarre; age 11 when she married King Philippe IV of France in 1284 CE

Maria Diaz I de Haro, wife of Prince Juan of Castile; age 17 when she married Juan in 1287 CE

Yolanda, daughter of Prince Manuel of Castile; age 12 when she married Prince Afonso of Portugal in 1287 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Pedro III of Aragon; age 17 when she married King Denis of Portugal in 1288 CE

Isabel of Castile, wife of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 8 when she married Jaime in 1291 CE

Blanche of Anjou, wife of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 15 when she married Jaime in 1295 CE

Yolanda, daughter of King Pedro III of Aragon; age 24 when she married Prince Roberto of Naples in 1297 CE

Constanza of Portugal, wife of King Fernando IV of Castile; age 12 when she married Fernando in 1302 CE

Beatriz, daughter of King Sancho IV of Castile; age 16 when she married King Afonso IV of Portugal in 1309 CE

Maria, daughter of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 12 when she married Prince Pedro of Castile in 1311 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 12 when she married Prince Juan Manuel of Villena in 1312 CE

Teresa d'Entença, wife of King Alfonso IV of Aragon; age 14 when she married Alfonso in 1314 CE

Marie of Lusignan, wife of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 42 when she married Jaime in 1315 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 10 when she married King Frederick I of Germany in 1315 CE

Eleonora of Castile, wife of Prince Jaime of Aragon; age 12 when she married Jaime in 1319 CE

Elisenda of Montcada, wife of King Jaime II of Aragon; age 30 when she married Jaime in 1322 CE

Blanca de La Cerda y Lara, wife of Prince Juan Manuel of Castile; age 10 when she married Juan Manuel in 1327 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Alfonso IV of Aragon; age 18 when she married King Jaime III of Majorca in 1336 CE

Cecilia of Comminges, wife of Prince Jaime of Aragon; age 16 when she married Jaime in 1336 CE

Maria of Navarre, wife of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 8 when she married Pedro in 1337 CE

Leonor of Portugal, wife of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 19 when she married Pedro in 1347 CE

Eleonora of Sicily, wife of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 24 when she married Pedro in 1349 CE

Juana Manuel, daughter of Prince Juan Manuel; age 11 when she married King Enrique of Castile in 1350 CE

Blanche of Bourbon, wife of King Pedro of Castile; age 14 when she married Pedro in 1353 CE

Constanza, daughter of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 18 when she married King Federico of Sicily in 1361 CE

Maria de Luna, wife of King Martin of Aragon; age 14 when she married Martin in 1372 CE

Juana, daughter of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 29 when she married Count Juan I of Ampurias in 1373 CE

Marthe of Armagnac, wife of King Juan I of Aragon; age 26 when she married Juan in 1373 CE

Beatriz of Portugal, wife of Prince Sancho of Castile; age 19 when she married Sancho in 1373 CE

Eleonora of Aragon, daughter of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 17 when she married King Juan I of Castile in 1375 CE

Eleonora, daughter of King Enrique II of Castile; age 12 when she married King Carlos III of Navarre in 1375 CE

Isabel of Portugal, wife of Count Alfonso Enriquez; age 13 when she married Alfonso in 1377 CE

Violant of Bar, wife of King Juan I of Aragon; age 15 when she married Juan in 1380 CE

Beatriz of Portugal, wife of King Juan I of Castile; age 10 when she married Juan in 1383 CE

Juana, daughter of King Juan I of Aragon; age 17 when she married Count Matthieu of Foix in 1392 CE

Eleonora of Albuquerque, wife of King Fernando I of Aragon; age 20 when she married Fernando in 1394 CE

Yolanda, daughter of King Juan of Aragon; age 19 when she married Duke Louis II of Anjou in 1400 CE

Blanca I of Navarre, wife of Prince Martin of Aragon; age 15 when she married Martin in 1402 CE

Juana, daughter of King Carlos III of Navarre; age 20 when she married Count Jean I of Foix in 1402 CE

Beatriz, daughter of King Carlos III of Navarre; age 14 when she married Count James II of La Marche in 1406 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Pedro IV of Aragon; age 31 when she married Count Jaime II of Urgell in 1407 CE

Margarita of Prades, wife of King Martin of Aragon; age 14 when she married Martin in 1409 CE

Maria of Castile, wife of King Alfonso V of Aragon; age 14 when she married Alfonso in 1415 CE

Catalina of Castile, wife of Prince Enrique of Aragon; age 15 when she married Enrique in 1418 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Carlos III of Navarre; age 24 when she married Jean IV of Armagnac in 1419 CE

Maria, daughter of King Fernando I of Aragon; age 17 when she married King Juan II of Castile in 1420 CE

Eleonora, daughter of King Fernando I of Aragon; age 26 when she married King Duarte of Portugal in 1428 CE

Agnes of Cleves, wife of Prince Carlos of Aragon; age 17 when she married Carlos in 1439 CE

Blanca II of Navarre, daughter of King Juan II of Aragon and Queen Blanca I of Navarre; age 18 when she married King Enrique IV of Castile in 1440 CE

Eleonora of Navarre, daughter of King Juan II of Aragon and Queen Blanca 1 of Navarre; age 15 when she married Count Gaston IV of Foix in 1441 CE

Juana Enriquez, wife of King Juan II of Aragon; age 19 when she married Juan in 1444 CE

Isabel of Portugal, wife of King Juan II of Castile; age 19 when she married Juan in 1447 CE

Joana of Portugal, wife of King Enrique IV of Castile; age 16 when she married Enrique in 1455 CE

Isabel I of Castile, wife of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 18 when she married Fernando in 1469 CE

Juana, daughter of King Enrique IV of Castile; age 13 when she married King Afonso V of Portugal in 1475 CE

Juana, daughter of King Juan II of Aragon; age 21 when she married King Fernando I of Naples in 1476 CE

Isabel, daughter of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 20 when she married Prince Afonso of Portugal in 1490 CE

Juana, daughter of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 22 when she married Felipe I of Castile in 1501 CE

Margaret of Austria, wife of Prince Juan of Aragon; age 17 when she married Juan in 1497 CE

Maria, daughter of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 18 when she married King Manuel I of Portugal in 1500 CE

Catalina, daughter of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 15 when she married Prince Arthur of England in 1501 CE

Germaine of Foix, wife of King Fernando II of Aragon; age 18 when she married Fernando in 1506 CE

112 women; average age at first marriage was 16. The eldest bride was 42 years old, and the youngest was 7.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Birthdays for today, April 24th:

Ramiro II, King of Aragon, 1086

Sabina of Bavaria, Duchess of Württemberg, 1492

William the Silent, Prince of Orange, 1533

Gaston, Duke of Orléans, 1608

Maria Clementina of Austria, Duchess of Calabria, 1777

Marau, Queen of Tahiti, 1860

Iman bint al-Hussein, Princess of Jordan, 1983

#ramiro ii#sabina of bavaria#maria clementina of austria#Queen Marau#Iman bint ِAl-Hussein#gaston of orleans#gaston of france#william the silent#long live the queue#royal birthdays

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

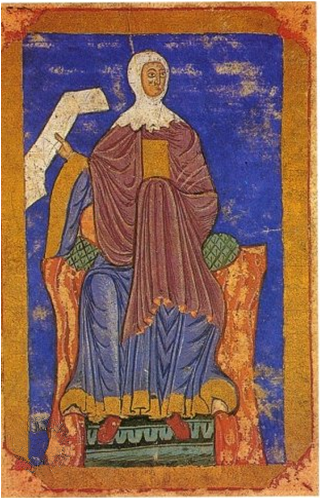

Petronilla (29 June/11 August 1136 – 15 October 1173), whose name is also spelled Petronila or Petronella, was Queen of Aragon from the abdication of her father, Ramiro II, in 1137 until her own abdication in 1164. After her abdication she acted as regent during the minority of her son (1164–1173). She was the last ruling member of the Jiménez dynasty in Aragon, and by marriage brought the throne to the House of Barcelona.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the neon-lit skies of Neo-Aragon, a futuristic city-state where past and future collided, resided a young woman named Althea. She was known throughout the city not only for her striking beauty, emphasized by her brilliant blue eyeshadow and glittering attire but also for her unique connection to the ancient history of Aragon.

Althea was a descendant of Ramiro II of Aragon, the legendary king who ruled in the 12th century. But unlike her ancestors, Althea had inherited more than just royal blood; she possessed a rare genetic anomaly that allowed her to communicate with the spirits of her forebears. This ability was both a gift and a curse, as the spectral voices often overwhelmed her with their tales of battles, politics, and ancient wisdom.

One evening, while attending a lavish celebration in the heart of Neo-Aragon, Althea felt a familiar but unsettling presence. The vibrant colors around her seemed to pulse with energy, mirroring the chaos within her mind. As she danced under the multicolored lights, she felt the unmistakable touch of her ancestor, Ramiro II.

"Althea," his voice echoed in her mind, "the past and future are intertwined. Our legacy is at risk."

She excused herself from the revelry and sought solace in a quiet corner. Closing her eyes, she allowed Ramiro's spirit to guide her. In a vision, she saw a shadowy figure manipulating the threads of time, seeking to alter the course of history and erase the legacy of the Aragonese kings.

"The Chrono-Saboteur," Ramiro whispered, "an ancient enemy long thought defeated. He has returned to finish what he started."

Determined to protect her heritage, Althea embarked on a journey to find the Time Crystal, an artifact hidden deep within the city's catacombs. The crystal had the power to stabilize the temporal rifts and prevent the Chrono-Saboteur from achieving his goal. Her path was fraught with danger, as the catacombs were guarded by temporal anomalies and remnants of past battles.

Guided by the wisdom of her ancestors and her own resilience, Althea navigated the labyrinthine passages. Each step brought her closer to the crystal and deeper into the annals of her family's history. She encountered spectral warriors, including her great-grandfather who had fought in the Aragonese Wars, and received their blessings and advice.

Finally, she reached the chamber of the Time Crystal. Its ethereal glow illuminated the ancient inscriptions on the walls, telling stories of bravery and sacrifice. As she approached the crystal, the Chrono-Saboteur appeared, a figure shrouded in darkness and malice.

"Your efforts are futile, girl," he sneered. "The past cannot protect the future."

Althea, undeterred, raised her hand to the crystal. "I am not alone," she declared. "I carry the strength of my ancestors."

With a surge of energy, the crystal responded to her touch. Light burst forth, enveloping the chamber and casting out the darkness. The Chrono-Saboteur howled in defeat as the temporal rifts sealed shut, restoring the timeline.

As the light faded, Althea found herself back at the celebration, her glittering attire shimmering more brightly than ever. The presence of Ramiro II lingered, his voice now filled with pride.

"You have done well, Althea. Our legacy is secure, and the future is yours to shape."

With newfound confidence and a deeper connection to her heritage, Althea returned to the dance floor. The neon lights of Neo-Aragon swirled around her, a testament to the enduring spirit of the past and the endless possibilities of the future.

0 notes

Text

The Huesca Bell, by Casado del Alisal

La campana de Huesca por Casado del Alisal Study of the painting (19th century, ): The canvas recreates the moment when King Ramiro II of Aragon shows the nobles of his kingdom the severed heads of the nobles who had dared to challenge his authority. The monumental architecture of the room and the greyish tones of the stone masterfully underline the gloomy character and the gloomy atmosphere…

View On WordPress

#19th century#19th century paintings#Aragon#Casado del Alisal#conde de Barcelona#Edad Media#Ramón Berenguer IV#Spanish painters

1 note

·

View note

Note

If the son of a king (he’s the fifth son) wants to become a priest, does he loses his place in the line of succession?

Absolutely. Unless there is a lack of heirs, his succession rights are given up. If all his brothers die, he can be offered the throne like Ramiro II of Aragon

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sancho Garcés IV (c. 1039 – 1076)

He was King of Pamplona from 1054 until his death. He was the eldest son of García Sánchez III and his wife, Estefanía, and was crowned king of Pamplona after his father was killed at the Battle of Atapuerca during a war with the Kingdom of León. Sancho, who was then fourteen years of age, was proclaimed king by the army in the camp by the field of battle with the consent of the king of León, Fernando I, also his uncle. Sancho's mother served as his regent until her death in 1058. Remaining faithful to her husband's policies, she continued to support the monastery of Santa María la Real of Nájera. Soon after Sancho's accession, many lords in the west of the kingdom went over to the Leonese. Sancho and Fernando signed a treaty defining their shared border in 1062.

As king, Sancho received support from his other uncle, King Ramiro I of Aragon. Out of gratitude for "his friendship, his fidelity, his help and his council", Sancho gave Ramiro possession of Lerda, Undués and the castle of Sangüesa.These places were probably to be held as fiefs or in a similar arrangement. Beginning in 1060, Sancho put pressure on al-Muqtadir, king of Zaragoza, and exacted from him annual payments of tribute, parias.

From 1065, he was in conflict with Castile, raised to a kingdom for Fernando's son Sancho II of Castile. This culminated in the so-called War of the Three Sanchos. Faced with an invasion by his cousin Sancho of Castile, Sancho of Pamplona asked for aid from his other cousin, Sancho of Aragon. Their forces were defeated by Sancho of Castile and El Cid. Sancho of Pamplona lost Bureba, Alta Rioja, and Álava to Sancho of Castile.

Sancho IV was assassinated in Peñalén by a conspiracy headed by his brother Ramón Garcés and his sister Ermesinda. During a scheduled hunt, Sancho was forced from a cliff by his siblings. Upon his assassination, the kingdom was invaded and ultimately partitioned between Sancho of Aragon and a third cousin, Alfonso VI of León and Castile. Alfonso occupied La Rioja and Sancho was proclaimed king in Pamplona.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

#el cid#polls#favourite characters#El Cid (2020)#rodrigo díaz de vivar#ruy#urraca de zamora#fernando i de león#sancha de león#doña jimena#jimena díaz#alfonso vi de león#garcía ii de galicia#sancho ii de castilla#elvira de toro#ramiro i de aragón#i realized this poll ended up being mainly about the leonese royal family but anyways#i will do other polls with some others characters later#i have included here ramiro i of aragon too because he was ferdinand i of leon's bastard brother#ramiro i and ferdinand i's father was sancho iii of pamplona and garcia iii of pamplona was their brother too#el cid polls

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BELL OF HUESCA - LA CAMPANA DE HUESCA

The king of Aragon, Alfonso I el Batallador, who died on September 7, 1134, without descendants, bequeathed his kingdoms to the Military Orders (that is, to the order of the Templars, the San Juanistas and the Knights of the Holy Sepulcher of Jerusalem), but no one thought of fulfilling that will. The Aragonese nobles, gathered in Jaca, offered the Crown of the Kingdom to their brother Ramiro, Bishop of Roda Barbastro. Ramiro was celebrating the Nativity of the Virgin in Tierrantona when he received the news of his brother's death the day before, having to occupy the throne. His coronation took place in Zaragoza on September 29, 1134, but with the commitment to return in two years to his ecclesiastical tasks, once the line of succession was secured.

The King, fed up with the excesses and rebellion of the Nobles, tried to take charge of the situation, but he had no idea how to do it; So he dispatched a trusted messenger to the monastery of San Ponce de Tomeras to ask his abbot for advice, with whom he had a deep friendship since his youth, when he took up the habits of a monk there. The messenger arrived at the monastery and quickly asked to be received by the Abbot, to whom he transmitted the King's message. The latter, after a brief thoughtful silence, ordered the messenger to accompany him to the garden. As they walked, and without anyone saying a word, the Abbot was cutting the cabbages (some sources speak of roses) that stood out the most over the others. After the walk, the Abbot turned to the messenger and said:

"Return to my Lord the King, and tell him how much you have seen"

The messenger, astonished at what had happened, mounted his horse and returned to convey the Abbot's message to the King. The monarch, unlike the stunned messenger, did understand what the Abbot meant. Now he knew exactly what he had to do.

Ramiro summoned the nobles to Cortes in Huesca, informing them that he wanted to show them a bell that he had ordered built, the sound of which would be heard throughout the kingdom. The nobles received the news between surprise and mockery, but on the day set there they appeared, curious to contemplate that bell that the King was talking about "let's go see that madness that the King wants to do", says the Chronicle of St. Juan de la Peña (Drafted in the fourteenth century) that the nobles thought. Before starting the Cortes, he invited them to a copious barbecue washed down with abundant good wine to agree on an agenda among all. After dinner, the King was inviting one by one the main members of the nobility to enter the room below the throne to discuss in private with them and show them the famous bell.

The nobles, as they entered, were cut down by six burly mountaineers who promptly decapitated them. Headless bodies were thrown into a corner while heads were arranged in a circle. Fifteen heads were arranged in this way on the ground when he brought in Bishop Ordás de Zaragoza, the main leader of the conspiracies against him. The Bishop, seeing the show, was overwhelmed. The King asked him if he did not think it was the most beautiful bell ever made, and if he believed that something was missing, to which the Bishop, full of terror, replied that nothing was missing. The King then replied:

"Yes, something is missing, and this is the clapper, and to make up for it your head is destined."

Ordás was also beheaded and his head hung from a hook in the middle of the circle formed by the other heads.

Once the bell was finished, the King invited the rest of the nobles to enter with him to admire the bell that he had told them so much about.

"You are going to see the bell that I have melted in the underground to ring for greater glory and strength of Ramiro II! I am certain that its ringing will make you restrained, solicitous and obedient to my commands ”.

The nobles upon entering the room were terrified at what they saw. They understood that they were not dealing with a wimp that they could handle at will, but that Ramiro II had proven to be a strong king who would not hesitate at anything in order to preserve the kingdom of Aragon.

As Aragonese that I am, I believe in the legend of the Bell of Huesca. And as a lover of History I have read that during the Reign of Ramiro II a few Nobles disappear from the documents ……. The room where the events occurred continues to exist, it is part of the Huesca Museum, as it stands next to the old Royal Palace.

Between 1879 and 1880, the painter of Romanticism, José Casado del Alisal painted a huge painting at the Spanish Academy of Fine Arts in Rome that represents the moment when the King discovered the "Bell" to the Nobles. Property of the Prado Museum, the painting has been deposited and has been exhibited in the Huesca City Hall since 1950.

Now you too can have this work of art in your home.

To do this first you need the painting "The Rape of the Sabine Women" by @thejim07.

You can download it HERE.

As always, I have to thank my colleagues @navidesigns and @artyssims for being my guinea pigs as always.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Fallecido el 7 de septiembre 1134 el rey de Aragón, Alfonso I el Batallador, sin descendencia, legó sus reinos a las Órdenes Militares (es decir, a la orden de los Templarios, a los Sanjuanistas y a los caballeros del Santo Sepulcro de Jerusalén), pero nadie pensó en cumplir dicho testamento. Los nobles aragoneses, reunidos en Jaca, ofrecieron la Corona del Reino a su hermano Ramiro, Obispo de Roda Barbastro. Ramiro se encontraba celebrando la Natividad de la Virgen en Tierrantona cuando recibió la noticia de la muerte de su hermano el día anterior, teniendo que ocupar el trono. Su coronación tuvo lugar en Zaragoza el 29 de septiembre de 1134, pero con el compromiso de regresar en dos años a sus quehaceres eclesiásticos, una vez asegurada la línea de sucesión. Con un rey inexperto y en apariencia pusilánime los nobles aragoneses pensaron que podrían manejarlo a su antojo.

El Rey, harto de los desmanes y rebeldía de los Nobles trató de hacerse cargo de la situación, pero no tenía la menor idea de cómo hacerlo; así que despachó un mensajero de confianza al monasterio de San Ponce de Tomeras para pedir consejo a su Abad, con el que le unía una profunda amistad desde su juventud, cuando tomó allí los hábitos de monje. El mensajero llegó al monasterio y rápidamente pidió ser recibido por el Abad, al que le transmitió el mensaje del Rey. Éste, después de un breve silencio pensativo, ordenó al mensajero que lo acompañara al huerto. Mientras paseaban, y sin que nadie pronunciara palabra alguna, el Abad fue cortando las coles (algunas fuentes hablan de rosas) que más sobresalían sobre las demás. Acabado el paseo, el Abad se volvió hacia el mensajero y le dijo:

“Vuelve a mi Señor el Rey, y cuéntale cuánto has visto”

El mensajero, atónito ante lo que había pasado, montó en su caballo y regresó a transmitir al Rey el mensaje del Abad. El monarca, al contrario que el estupefacto mensajero, sí que entendió lo que el Abad quería decir. Ahora sabía exactamente lo que tenía que hacer.

Ramiro convocó a los nobles a Cortes en Huesca comunicándoles que quería enseñarles una campana que había mandado construir, cuyo sonido se escucharía por todo el reino. Los nobles recibieron la noticia entre la sorpresa y la burla, pero el día fijado allí se presentaron, curiosos por contemplar esa campana de la que el Rey les hablaba “vayamos a ver esa locura que el Rey quiere hacer “, dice la Crónica de San Juan de la Peña (Redactada en el siglo XIV) que pensaron los nobles. Antes de empezar las Cortes, les invitó a un copioso asado regado con abundante buen vino para consensuar un orden del día entre todos. En la sobremesa, el Rey fue invitando uno a uno a los principales miembros de la nobleza a entrar en la sala de debajo del trono para debatir en privado con ellos y enseñarles la famosa campana.

Los nobles, conforme iban entrando, eran reducidos por seis fornidos montañeses que sin perder tiempo los decapitaban. Los cuerpos descabezados eran echados a un rincón mientras las cabezas eran dispuestas en un círculo. Quince cabezas se disponían de esta forma en el suelo cuando hizo entrar al Obispo Ordás de Zaragoza, principal cabecilla de las conjuras contra él. El Obispo, al ver el espectáculo, quedó sobrecogido. El Rey le preguntó si no le parecía la más hermosa campana jamás hecha, y si creía que le faltaba algo, a lo que el Obispo, lleno de terror, contestó que no faltaba nada. El Rey entonces le contestó:

“Sí que le falta algo, y esto es el badajo, y para suplirlo destino tu cabeza”.

Ordás fue también decapitado y su cabeza colgada de un gancho en medio del círculo que formaban las otras cabezas.

Una vez terminada la campana, el Rey invitó al resto de los nobles a entrar con él para admirar la campana de la que tanto les había hablado.

“Vais a ver la campana que he hecho fundir en los subterráneos para que repique a mayor gloria y fortaleza de Ramiro II,! Estoy cierto que su tañido os hará comedidos, solícitos y obedientes a mis mandatos”.

Los nobles al entrar en la sala quedaron aterrorizados ante lo que vieron. Comprendieron que no se las tenían con un pelele al que pudieran manejar a su antojo, sino que Ramiro II había demostrado ser un rey fuerte que no vacilaría ante nada con tal de conservar el reino de Aragón.

Como Aragonés que soy, creo en la leyenda de la Campana de Huesca. Y como amante de la Historia he leído que durante el Reinado de Ramiro II unos cuantos Nobles desaparecen de los documentos……. La sala donde ocurrieron los hechos sigue existiendo, forma parte del Museo de Huesca, ya que se levanta junto al antiguo palacio Real.

Entre 1879 y 1880, el pintor del Romanticismo, José Casado del Alisal pinto en la Academia Española de Bellas Artes de Roma un enorme cuadro que represente el momento en el que el Rey descubre a los Nobles la “Campana”. Propiedad del Museo del Prado, el cuadro esta depositado y se expone en el Ayuntamiento de Huesca desde 1950.

Ahora vosotros también podéis tener en vuestras casas esta obra de arte.

Para ello primeo necesitáis el cuadro de “El Rapto de las Sabinas” de @thejim07.

Lo podéis descargar AQUÍ.

Como siempre he de dar las gracias a mis compañeros @navidesigns y @artyssims por ser como siempre mis conejillos de Indias.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sos del Rey Católico in Zaragoza. Spain Sos del Rey Católico is a historic town and municipality in the Cinco Villas comarca, province of Zaragoza, in Aragon, Spain Located on rocky and elevated terrain, this important border town served well as a stronghold from the year 907 It was incorporated in 1044 by Ramiro I into the Kingdom of Aragon. n the year 1452, during the Navarrese Civil War, Queen Juana Enríquez de Córdoba moved to the town, then called "Sos". There she gave birth to the infante Ferdinand on March 10, 1452, who later became Ferdinand II of Aragon, one of the Catholic Monarchs. His birth added "del Rey Católico" to the name of the town, which translates as "of the Catholic King"

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#discoveringaragón No. 3: Afternoon in Huesca

Finalement j’ai passé et aussi réussi tous les examens de ma première année à la fac, ce que signifie que je peux vivre des aventures au dehors de la bibliothèque. Miguel n’est pas encore un homme libre, c’est pour ça que je lui accompagne à Huesca, où il doit terminer encore quelques affaires à la fac. Entretemps je me mets en marche pour découvrir cette petite mais jolie ville.

Mittlerweile sind alle Prüfungen vorbei und auch bestanden, was bedeutet dass ich endlich auch wieder Abenteuer außerhalb der Bibliothek erleben darf. Miguel ist leider noch kein freier Mann, deswegen begleitete ich ihn nach Huesca, wo er an der Uni noch ein paar Sachen erledigen musste. Währenddessen begab ich mich also auf einen kleinen Entdeckungsspaziergang durch diese kleine, aber sehr feine Stadt.

Finalmente he acabado todos los exámenes (y también aprobado), lo que significa que al fin puedo volver a tener aventuras fuera de la biblioteca. Miguel aún no es un hombre libre, así que el jueves pasado lo acompañé a Huesca, donde tenía que acabar alguna cosita en la uni. Mientras tanto me fui a descubrir un poquito esta pequeña pero preciosa ciudad.

Huesca se trouve à une heure en train de Saragosse, aux pieds des Pyrénées, ce qu’on note surtout avec le climat, car il fait beaucoup moins chaud. Elle n’a même pas 53 000 habitants, mais il y a plein d’étudiants et fonctionnaires qui font l’aller-retour tous les jours (l’université de Saragosse à un campus ici, et ceux qui n’entrent pas á Saragosse viennent ici). Le centre ville entière est zone piétonnière et très soigné. A quatre heures et demi de l’aprem il n’y a personne dans les rues et je profite du silence. Tout en haut de la colline se trouve la cathédrale et la mairie. Au milieu de la place entre ces deux édifices se trouve une fontaine, des arbres et quelques bancs. L’ambiance pacifique m’invite à me poser pour une petite heure et lire quelques chapitres de mon livre (The Handmaid’s Tale).

Huesca befindet sich eine Zugstunde von Zaragoza entfernt und liegt am Fuß der Pyrenäen, was man klimatechnisch sehr merkt, da es immer etwas kühler ist. Sie hat nur knapp 53 000 Einwohner, aber es pendeln extrem viele Studenten und Beamte hierher. Das gesamte Stadtzentrum ist Fußgängerzone und sehr gepflegt. Um halb fünf nachmittags ist außer mir keine Menschenseele unterwegs und ich genieße die absolute Stille. Ganz oben auf dem Hügel an dem die Stadt geschmiegt ist, befindet sich die Kathedrale und das Rathaus. Ich verliebe mich sofort in den kleinen Platz dazwischen, mit dem Brunnen, Bänken und schattenspendenden Bäumen und beschließe, dort erstmal ein paar Kapitel in meinem Buch zu lesen (The Handmaid’s Tale).

Huesca está a una hora en tren desde Zaragoza, a los pies de los pirineos, lo que se nota mucho en las temperaturas. Son mucho más agradables. No llega ni a los 53 000 habitantes, pero hay mucho estudiante y funcionario que hace el viaje de ida y vuelta cada día. El casco antiguo es enteramente zona peatonal y muy cuidado. A las cuatro y media de la tarde no hay ni dios en la calle y disfruto de la tranquilidad. Encima de la colina están la catedral y el ayuntamiento. Me enamoro instantáneamente de la pequeña plaza situada entre ellas, con sus árboles y su fuente. Me quedo una horita leyendo mi libro (actualmente el Cuento de la Criada).

En suite je visite le musée archéologique, au final de la rue. Je ne suis pas seule, mais il n’y a quand même pas un bruit. L’entrée est gratuite pour tous et je suis surprise par la qualité de l’exposition. Chaque côté de cet édifice octogonale présente une époque différente de l’histoire de la région. Les panneaux d’affichages et les textes (qu’en Espagnol, sorry) sont très simples à entendre et plaisantes à la vue. On ne voit ça pas tous les jours dans des musées si petits! J’apprends beaucoup sur la région: par exemple je ne savais pas qu’il y a des dolmen (comme chez Asterix) aussi dans les Pyrénées ou que les gens d’ici entretenaient des contacts commerciaux avec les Etrusques et les Phéniciens avant de l’arrivée des Romans. Dans le musée se trouve aussi la salle de trône de la reine Petronila, actuellement le lieu d’une exposition temporaire sur “Labitolosa”, une ville romaine très curieuse. Et juste à côté se trouve une petite chapelle, avec une histoire glauque…

Anschließend besuche ich das Archäologische Museum, am Ende der Straße. Ich bin zwar nicht die einzige Besucherin, aber im Innenhof ist es trotzdem totenstill. Der Eintritt ist gratis und das Museum überraschend gut. Jeder Trakt des achteckigen Gebäudes ist einer anderen Epoche in der Geschichte Huescas und seiner Umgebung. Die Schaukästen und dazugehörenden Texte sind einfach zu verstehen und visuell sehr ansprechend. Sowas sieht man selten in so kleinen Museen! Ich lerne erstaunlich viel über die Region: zum Beispiel wusste ich gar nicht dass man Dolmen (wie aus Asterix und Obelix) auch in den Pyrenäen finden kann, oder dass bevor die Römer kamen bereits Handel mit den Etruskern und Phöniziern betrieben wurde. Im Museum befindet sich ebenfalls der Thronsaal von Königin Petronila, in dem gerade eine temporäre Ausstellung über Labitolosa stattfindet, eine römische Fundstätte in der Nähe. Und gleich daneben befindet sich eine kleine Kapelle, in der sich anscheinend folgende Geschichte abgespielt haben soll…

A continuación visito el museo archeologico al final de la calle. No soy la única visitante pero el patio interior está tranquilísimo. La entrada es gratuita y el museo está sorprendentemente bien. Cada lado de este edificio octogonal cuenta un época diferente de la historia de la región. Las vitrinas y sus textos son muy fáciles deentender y visualmente sugerentes. ¡Es raro verlo en museo tan chiquitos! Aprendo un montón sobre la historia de Huesca y sus alrededores. Por ejemplo, no sabía que había dólmenes (como en Asterix y Obelix) también en los Pirineos -¡Y unos cuantos además!- O que había flujos de comercio con los etruscos y fenicios bastante antes de que llegaran los romanos. En el museo también se encuentra la sala de tronos de la reina Petronila, donde actualmente hay una exposición temporal sobre Labitolosa, una antigua ciudad romana cerca de Huesca. Y justo al lado está una pequeña capilla, donde la gente dice que pasó la siguiente historia…

Ramiro II était très préoccupé de la situation politique en Aragon après la mort de son frère. Surtout les nobles étaient peu obéissants. Désespéré il envoya un messager chez son ancien maître pour lui demander un avis. Le maître demanda au messager de lui accompagner dans le jardin, où il coupa les roses qui plus dépassaient le buisson. Puis, il dit au messager de répéter le geste devant les yeux du roi. Le roi fit appeler tous les nobles chez soi, sous le prétexte de vouloir construire une cloche tellement grande qu’on l’allait écouter dans tout le règne. Après il fit couper la tête aux nobles les plus rebeldes, arrangea les têtes dans la chapelle en forme de cloche et fit entrer le reste des nobles.

Ramiro II war sehr besorgt um den Zustand Aragons nach dem Tod seines Bruders. Besonders die Adligen waren sehr ungehorsam. Verzweifelt schickte er seinem alten Lehrer einen Boten um ihn um Rat zu beten. Dieser nahm den Boten mit ihn den Garten, wo er die Rosen abschnitt, die am meisten aus dem Gebüsch herausstanden und sagte dem Boten, vor dem König die Geste zu wiederholen. Der König ließ also alle Adeligen zu sich rufen, unter dem Vorwand eine große Glocke bauen zu wollen, die man im ganzen Reich hören würde. Dann ließ er den schlimmsten Rebellen den Kopf abschlagen, legte sie in der Kapelle in Glockenform auf und die anderen Adeligen eintreten.

Ramiro II estaba muy preocupado por la situación política en Aragón después de la muerte de su hermano. Sobre todo porque los nobles eran muy desobedientes. Desesperado mandó un mensajero para demandar ayuda a su antiguo Abad (antes de ser Rey había sido monje en un Monasterio). El maestro llevó al mensajero a su jardín y cortó las rosas que más destacaban del arbusto. Le dijo de repetir este gesto delante del Rey. El Rey llamó entonces a todos los nobles, bajo el pretexto de querer construir una campana tan grande que se iba a escuchar en todo el reino. Luego hizo cortar las cabezas a los noblesmás rebeldes, los colocó en forma de campana en dicha capilla y hizo entrar al resto de los invitados.

A painting of the legend, by José Casado, which you can see in the same museum

Bon, on ne sait pas trop si cette histoire est vraie ou pas, mais les pâtissiers de Huesca ont créé en tout cas une pâtisserie en sa honneur: Les cloches de Huesca. Généralement, les pâtisseries de Huesca sont connues bien dehors de ses murs: Le “Pastel Ruso”, la “Trenza de Almudévar” (mon préféré: de la pâte feuilleté avec des noix et un remplissage crémeux…) les “Alfahares” (des petites nuages de sucre, jaune d’oeuf et huile d’olive) ou les castagnes de massepain. Ahh, quelle jolie ville!

Ob diese Geschichte wahr ist, ist nicht ganz sicher, aber ihr zu Ehren wurde sogar ein Nachtisch kreiert: Die Campanas de Huesca. Generell ist Huesca was Süßspeisen angeht ziemlich stark unterwegs: der “Pastel Ruso” von der über 100 Jahre alten Konditorei Ascaso ist weit über die Stadtgrenzen hinaus bekannt, genauso wie die “Trenza de Almudévar” (mein Favorit - buttriger Blätterteig mit Nüssen und Cremefüllung), die “Alfahares” (weiche Dotter-Zucker-Olivenöl-Wölkchen) oder Marzipan-Kastanien. So eine schöne Stadt!

Bueno, no se sabe muy bien si esta historia es verdad o no, pero los pasteleros oscenses crearon un postre para conmemorar la leyenda: las Campanas de Huesca. En general, los pasteles de Huesca son bien conocidos también por la gente de fuera: por ejemplo el Pastel Ruso de la Pastelería Ascaso, o la trenza de Almudévar, o los Alfahares y las castañas de mazapán. ¡Me gusta esta ciudad!

Il commence à pleuvoir un peu, mais nous nous promenons encore un peu dans le parc avant de prendre le train de retour. L’escapade a valu la peine!

Es beginnt leicht zu regnen, aber wir spazieren noch durch den Park bevor es zurück nach Zaragoza geht. Der Ausflug war kurz aber auf jeden Fall wert!

Empieza a llover un poco, pero nos paseamos por el parque antes de volver a la estación. ¡La escapada ha valido la pena!

1 note

·

View note