#rainforest ecology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Secrets of the Leafcutter Ants Revealed

Discover the amazing world of leafcutter ants! These remarkable insects showcase teamwork, agriculture, and unique adaptations that are sure to fascinate you.

Check out my other videos here: Animal Kingdom Animal Facts Animal Education

#Helpful Tips#Wild Wow Facts#leafcutter ants#ant colonies#insect behavior#nature documentary#rainforest ecology#animal behavior#ant farming#biodiversity#social insects#leafcutter ant facts#ecosystem#entomology#nature secrets#survival strategies#teamwork in nature#insect societies#leafcutter ant life cycle#fascinating insects#wildlife exploration#environmental science#nature enthusiasts#science education#animal adaptations#ecological balance#youtube#animal science#fun animal facts#animal habitats

1 note

·

View note

Text

The World's Forests Are Doing Much Better Than We Think

You might be surprised to discover... that many of the world’s woodlands are in a surprisingly good condition. The destruction of tropical forests gets so much (justified) attention that we’re at risk of missing how much progress we’re making in cooler climates.

That’s a mistake. The slow recovery of temperate and polar forests won’t be enough to offset global warming, without radical reductions in carbon emissions. Even so, it’s evidence that we’re capable of reversing the damage from the oldest form of human-induced climate change — and can do the same again.

Take England. Forest coverage now is greater than at any time since the Black Death nearly 700 years ago, with some 1.33 million hectares of the country covered in woodlands. The UK as a whole has nearly three times as much forest as it did at the start of the 20th century.

That’s not by a long way the most impressive performance. China’s forests have increased by about 607,000 square kilometers since 1992, a region the size of Ukraine. The European Union has added an area equivalent to Cambodia to its woodlands, while the US and India have together planted forests that would cover Bangladesh in an unbroken canopy of leaves.

Logging in the tropics means that the world as a whole is still losing trees. Brazil alone removed enough woodland since 1992 to counteract all the growth in China, the EU and US put together. Even so, the planet’s forests as a whole may no longer be contributing to the warming of the planet. On net, they probably sucked about 200 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year between 2011 and 2020, according to a 2021 study. The CO2 taken up by trees narrowly exceeded the amount released by deforestation. That’s a drop in the ocean next to the 53.8 billion tons of greenhouse gases emitted in 2022 — but it’s a sign that not every climate indicator is pointing toward doom...

More than a quarter of Japan is covered with planted forests that in many cases are so old they’re barely recognized as such. Forest cover reached its lowest extent during World War II, when trees were felled by the million to provide fuel for a resource-poor nation’s war machine. Akita prefecture in the north of Honshu island was so denuded in the early 19th century that it needed to import firewood. These days, its lush woodlands are a major draw for tourists.

It’s a similar picture in Scandinavia and Central Europe, where the spread of forests onto unproductive agricultural land, combined with the decline of wood-based industries and better management of remaining stands, has resulted in extensive regrowth since the mid-20th century. Forests cover about 15% of Denmark, compared to 2% to 3% at the start of the 19th century.

Even tropical deforestation has slowed drastically since the 1990s, possibly because the rise of plantation timber is cutting the need to clear primary forests. Still, political incentives to turn a blind eye to logging, combined with historically high prices for products grown and mined on cleared tropical woodlands such as soybeans, palm oil and nickel, mean that recent gains are fragile.

There’s no cause for complacency in any of this. The carbon benefits from forests aren’t sufficient to offset more than a sliver of our greenhouse pollution. The idea that they’ll be sufficient to cancel out gross emissions and get the world to net zero by the middle of this century depends on extraordinarily optimistic assumptions on both sides of the equation.

Still, we should celebrate our success in slowing a pattern of human deforestation that’s been going on for nearly 100,000 years. Nothing about the damage we do to our planet is inevitable. With effort, it may even be reversible.

-via Bloomburg, January 28, 2024

#deforestation#forest#woodland#tropical rainforest#trees#trees and forests#united states#china#india#denmark#eu#european union#uk#england#climate change#sustainability#logging#environment#ecology#conservation#ecosystem#greenhouse gasses#carbon emissions#climate crisis#climate action#good news#hope

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

From the article:

On May 21, twenty communities in the Peruvian Amazon received long-awaited legal titles to their traditional lands, marking a significant victory in the struggle for Indigenous peoples’ land rights and environmental protection. Encompassing approximately 75,000 acres, an area three times the size of Manhattan, the titles were delivered during a well-attended ceremony in the Huitoto Murui Indigenous community of Centro Arenal, in the state of Loreto. Indigenous leaders traveled from remote rivers that feed into the Amazon to receive their titles in person. Local and state officials also attended. “Today we can say that our lands are indeed ours, and we can defend ourselves from any aggression that arrives at our community,” said Anibal Oliveira, Indigenous Ticuna leader of the San Salvador community. Last year, an innovative strategy devised with our partners allowed Rainforest Foundation US to secure more land titles in ten months than in the previous three years. Now, in 2024, we are already surpassing that record. An additional 10,500 acres of titles are expected to be delivered to communities in the same region over the next couple months.

#indigenous conservation#indigenous rights#amazon conservation#habitat conservation#amazon rainforest#peruvian amazon#good news#hope#newyears2025#environment#ecology#habitat#rainforest conservation#ecoanxiety#ecogrief

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

Come Have a Bite with the Vampire Bat!

Desmodus rotundus, better known as the common vampire bat, is a species of leaf-nosed bat native to Central and South America, as well as parts of the Caribbean. They are found primarily in tropical forests, particularly rainforests, but can also roam into scrubland and agricultural areas. Common vampire bats roost in hollow trees, caves, and abandoned buildings, making them a common sight in or near urban areas.

As their name implies, the common vampire bat feeds exclusively on blood, particularly those of mammals. In the wild they will feed on large animals like tapirs, but they more frequently go after domesticated animals like cattle, goats, and horses. However, when ideal prey is lacking they will also feed off lizards, turtles, snakes, toads, and crocodiles. Like most bats, D. rotundus uses echolocation to find prey. Then, special heat sensors in the nose help it to detect blood vessels close to the skin; it then bites open a small flap of the skin and drinks its fill. Its saliva contains both painkillers and anticoagulents, so victims seldom notice their host until after it has fed. Predators of D. rotundus include owls, hawks, and eagles.

Common vampire bats live in colonies of about 100 individuals, although colonies consisting of up to 1,000 individuals have been recorded. Within these colonies, males and females roost separately; females cluster in groups of 8-20, while males roost individually and guard territories against other males. However, D. rotundus is highly social, and males and females will both groom members of the same and opposite sex. This grooming can even extend to homosexual behaviours like genital licking, which is thought to reinforce hierarchies and strengthen social bonds.

D. rotundus can breed year-round, but females only raise one pup per year. Males typically mate with females in or near their defended territories. Afterwards, females carry their pregnancy for about 7 months before giving birth to a single pup. These young feed on their mother's milk for their first month; during this time, other adult females will often provide the mother with excess blood as she cannot hunt for herself. Once the pup is weaned they begin recieving blood from their mothers, and at four months they begin accompanying her on hunts. At about five months they are fully independent; females will remain in their mother's roost while males will leave to establish their own territories. Young become fully mature at about a year old, and adults may live to 12 years in the wild.

The common vampire bat is relatively plain looking, as far as bats go. They are generally gray or brown, with darker fur over their backs and dark brown or black membranes along their wings. The nose has a distinct triangle shape, which houses special heat-sensing organs. Likewise, the ears are large and triangular, used for echolocation. Adults are rather small, about 9 cm (3.5 in) long with an average wingspan of 18 cm (7 in) and a weight of 25–40 grams (2 oz).

Conservation status: The IUCN lists D. rotundus as Least Concern. In fact, populations of the common vampire bat are increasing due to the abundance of livestock as a food source.

If you like what I do, consider buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Jose Gabriel Martinez Fonseca

Sheri & Brock Fenton

Nicolas Reusens

#common vampire bat#Chiroptera#Phyllostomidae#vampire bats#leaf-nosed bats#bats#mammals#tropical forests#tropical forest mammals#tropical rainforests#tropical rainforest mammals#urban fauna#urban mammals#central america#south america#queer fauna#nature is queer#animal facts#biology#zoology#ecology

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It was an assumption—almost an article of faith—amongst many biogeographers, ecologists, and paleoecologists that the great regional rainforests were, at Western contact, the product of natural climatic, biogeographic, and ecological processes,” wrote paleoecologist Chris Hunt, now based at Liverpool John Moores University, and his colleague, Cambridge University archaeologist Ryan Rabett, in a 2014 paper. “It was widely thought that peoples living in the rainforest caused little change to vegetation.” New research is challenging this long-held assumption. Recent paleoecological studies by Hunt and other colleagues show evidence of “disturbance” in the vegetation around Pa Lungan and other Kelabit villages, indicating that humans have shaped and altered these jungles not just for generations—but for millennia. Borneo’s inhabitants from a much more distant past likely burned the forests and cleared lands to cultivate edible plants. They created a complex system in which farming and foraging were intertwined with spiritual beliefs and land use in ways that scientists are just beginning to understand. Samantha Jones, lead author on this investigation and researcher at the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution, has studied ancient pollen cores in the Kelabit Highlands as part of the Cultured Rainforest Project. This is a U.K.-based team of anthropologists, archaeologists, and paleoecologists that is examining the long-term and present-day interactions between people and rainforests. The project has led to continuing research that is forming a new scientific narrative of the Borneo highlands. People were most likely manipulating plants from as early as 50,000 years ago in the lowlands, Jones says. That’s around the time humans likely first arrived. Scholars had long classified these early inhabitants as foragers—but then came the studies at Niah Cave. There, in a series of limestone caverns near the coast, scientists found paleoecological evidence that early humans got right to work burning the forest, managing vegetation, and eating a complex diet based on hunting, foraging, fishing, and processing plants from the jungle. This late Pleistocene diet spanned everything from large mammals to small mollusks, to a wide array of tuberous taros and yams. By 10,000 years ago, the folks in the lowlands were growing sago and manipulating other vegetation such as wild rice, Hunt says. The lines between foraging and farming undoubtedly blurred. The Niah Cave folks were growing and picking, hunting and gathering, fishing and gardening across the entire landscape.

[...]

“The Cultured Rainforest project has shown how profoundly entangled the lives of humans and other species in the rainforest are,” says University of London anthropologist Monica Janowski, a member of the project team who has spent decades studying highland Borneo cultures. “This entanglement has developed over centuries and millennia and succeeds in maintaining a relatively balanced relationship between species.” Borneo’s jungle is, in fact, anything but untouched: What we see is a result of both human hands and natural forces, working in tandem. The Kelabit are a little bit farmer and a little bit forager with no clear line between, Janowski says. This dualistic approach to land use may reveal a deeper human nature. “Scratch any modern human and you will find, under the surface, a forager,” she says. “We have powerful foraging instincts. We also have powerful instincts to manage plants and animals. Both of these instincts have been with us for millennia.”

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phyllopsora corallina

Rainforest coral lichen

This lichen has a squamulose-areolate thallus which grows on bark and moist rocks in rainforests and costal forests. It has green, convex, crenulate areoles each up to 0.5 mm wide, which grow far apart when young, and closer and overlapping when older. It has globose to cylindrical to coralloid isidia along the pubescent margins, and produces brown, biatorine apothecia.

images: source

info: source | source

#lichen#lichens#lichenology#lichenologist#mycology#ecology#biology#fungi#fungus#symbiosis#symbiotic organisms#algae#trypo#trypophobia#Phyllopsora corallina#Phyllopsora#I'm lichen it#lichen a day#daily lichen post#lichen subscribe#life science#environmental science#natural science#nature#naturalist#beautiful nature#weird nature#rainforest#see the forest for the lichens

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

You'll love his 𝙏𝙤𝙭𝙞𝙘 𝙇𝙤𝙫𝙚

♛┈💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜

When I rewatched FernGully: The Last Rainforest I realized that I had to hint to the world how much we need an ai cover for this song. The idea for Hexxus Donnie appeared into my head almost instantly due to their shared mischievous energy and Rottmnt Donnie's sheer obsession with progress and finding fuel for their big machines (There is no Uranium without U, remember?)

♛┈💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜

♛┈💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜✤💜

@swagreecrow @neocelticavalon @kawaiibunga @sivy-chan-blog @narwals14 @angelcatlowyn @dai-su-kiss @janet-the-dark-queen @turtle-babe83 @foxflamewarrior @cowabunga-doll @wolfroks @aeempress @androidships007 @iheartchv @raphsmuneca @characterworkshoppe @roxosupreme @thedl2912 @cthonyxa @lordfreg @niphredil-14

#rottmnt#tmnt 2018#rottmnt 2018#rise of the tmnt#donnie 2018#rise donnie#ferngully#the last rainforest#hexxus#tim curry#1992#90's cartoons#ecology

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

My one bitter moment I remember from semester 1 at uni was when I mentioned that temperate rainforests are a thing and for some reason had to fight for my fucking life because no one believed me??

I'm not sure if it was because they thought rainforests have to be warm?? But like. Scotland very much has temperate rainforest and there should be more in the rest of the UK

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

I felt like doing some more speculative evolution, this time some digital sketches in the same vein as the hand drawn sketches I started out with. I was mainly inspired by an article from Vox about some animals biologist imagine could exist in a million years: https://www.vox.com/down-to-earth/22734772/future-animals-evolution-unexplainable Those examples included a whale-like rat, a flightless, carnivorous pigeon, and a giant mantis. I originally intended to draw each of them by themselves but ended up drawing other organisms that could exist in their respective ecosystems.

The whale-like rat I imagined as filter feeding like crabeater seals while having enlarged incisors for feeding on jellyfish (which have been exploding in population). Along with it I included a predatory marine rat, a large descendant of bristle mouth fish, and an arrowhead shaped squid that can more effectively glide above water to escape predators (yes there are squid that glide).

The carnivorous pigeon I actually imagine being more omnivorous but willing to case down small animals on occasion like the feather tailed descendant of mice shown here. I also included my take on the Rabbuck (deer-like descendants of rabbits) from Dougal Dixon's After Man and a descendant of feral pigs that have become largely predatory.

The giant mantis ranges from 12-14in in body length and evolved stronger limbs from grappling tougher prey as well as a body resembling branches to disguise itself while hunting. One of it's prey is a lizard that has begun to evolved powered flight while another is a tree-frog that can change its skin color and texture akin to cephalopods for camouflage. On of the few predators the mantis itself would have is the gliding cat.

These are just a few of the organisms that would exist in these ecosystems and I might do a sketch dump for other environments.

As always, comments and critiques are welcome.

#my art#digital art#creature design#digital sketch#speculative evolution#speculative zoology#speculative biology#future evolution#ecology#predators#prey#rat#fish#squid#pigeon#mouse#rabbit#boar#praying mantis#lizard#frog#cat#speculative#invertebrates#vertebrates#plains#ocean#rainforest#mantis

24 notes

·

View notes

Video

Steely-vented Hummingbird by Adam Rainoff Via Flickr: The Steely-vented Hummingbird (Saucerottia saucerottei) is a captivating species native to the tropical and subtropical forests of Central and South America. This photo, taken at La Minga Ecolodge near Cali, Colombia, captures a female perched gracefully amidst a backdrop of soft green tones. Her iridescent green feathers glisten in the natural light, with hints of blue and gold adding depth to her plumage. At 1988 meters above sea level, this location offers the perfect environment to observe the diversity of hummingbirds that thrive in Colombia, a country known for its remarkable avian richness. From a technical perspective, this image was taken with a Canon R5 and a 100-500mm lens at 500mm. The camera was set to TV mode with a shutter speed of 1/1000 second, ready for action shots, but this hummingbird’s momentary stillness provided an opportunity to switch focus. The fading light required me to raise the ISO to 800, a setting the R5 handles with ease, delivering a noise-free result that preserves fine details. Handheld at this focal length, the camera’s stabilization ensured sharpness while maintaining flexibility to adjust composition on the fly. ©2021 Adam Rainoff Photographer

#La Cumbre#Valle del Cauca#Colombia#hummingbird#bird#nature#wildlife#Saucerottia#photography#rainforest#tropical#feathers#plumage#iridescent#perch#flight#conservation#environment#ecology#forest#mountains#travel#eco-tourism#biodiversity#Canon#lens#adventure#exploration#exotic#natural

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

100 tons of dead fish collected in a Greek town last week

#dead fish#athens#greece#fishing#ecology#natural disasters#collapse#climate change#global warming#ecosystem#rainforest collapse#destruction#self destruction#end of the world#conservation#extinction#doom and gloom#tipping point#apocalypse#catastrophic#climate catastrophe

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deforestation in the Amazon Increases Local Heat by Up to 4°C

Temperature rise in deforested areas could be up to 14 times higher, says study

The global climate crisis is one of the reasons why the Amazon is getting hotter; however, a significant portion of the warming in the region is of local and regional origin, linked to the deforestation of the biome. A study conducted by Brazilian and British researchers is the first to quantify the different contributions to this effect.

According to the analysis published in the scientific journal PNAS, the increase in temperature in heavily deforested areas of the Amazon basin may have been up to 14 times higher than what would have occurred if the forest had not been cleared.

This corresponds to temperatures 4°C higher.

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#science#environmentalism#ecology#amazon rainforest#brazilian politics#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

“We have a moral obligation to try to repair the damage caused by our ancestors. In doing so, we would find that temperate rainforests are amongst our best allies in the battles we face.

To stave off the existential threat posed by the climate crisis, it’s imperative that we not only cease burning fossil fuels but also restore the natural carbon sinks that we’ve destroyed. Rampaging wildfires and killer floods show that climate breakdown is already upon us: we’ve already pumped too much carbon into the atmosphere and need to start actively removing it.

Tech entrepreneurs dream of building machines to capture carbon dioxide from the air, but they’re overlooking the ones that nature spent millions of years designing: trees.”

-Guy Shrubsole, The Lost Rainforests of Britain

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

“An understanding of the natural world & what's in it is a source of not only a great curiosity, but great fulfillment.”

By, Sir David Attenborough

#naturecore#david attenborough#ecosystems#ecology#mindfulness practices#rainforest#photography on tumblr#peace and tranquillity

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Get Foxy with the Grey-headed Flying Fox

Pteropus poliocephalus, better known as grey-headed flying foxes, are a species of megabat native to eastern Australia. They are typically found in rainforests, woodlands, and swamps, but they have also become common in more agricultural and urban areas, particularly those that maintain large groves of trees. They are semi-migratory, moving when food availability diminishes, and can travel over 1000 km (620 mi) over the course of a season.

Like most bats, grey-headed flying foxes forage at night. They feed exclusively on fruit, pollen, nectar, and tree bark-- most commonly from figs and two species of eucalyptus tree-- and may fly up to 50 km (31 mi) in a single night to find food. Although they are quite large, P. poliocephalus can fall prey to eagles, goannas and snakes, particularly as pups or juveniles.

Because they do not feed on insects, these bats do not use echolocation to navigate. Instead, they use a large range of calls to communicate with other members of their colony, which can contain several hundred members in the summer. Winter colonies are slightly smaller, and segregated by sex, but individuals and families within these groups will stay together for several generations.

Mating occurs between March and May, when males stake out territories and compete to attract females. After mating, mothers seclude themselves in a female-only colony and gestate a singe pup about 6 months after breeding. Weaning takes an additional 5-6 months, after which juveniles separate from their mother. Daughters typically stay within their mother's winter colony, while sons join the male colony after a year's time. Individuals take approximately 30 months to become fully mature, and may live up to 10 years in the wild.

The grey-headed flying fox is notable for being the largest of Australia's bat species. Adults can be anywhere from 600-1000 g (21.5- 35.2 oz), with a wingspan of up to 1 m (3.3 ft). As their name implies, the body is covered with burnt orange fur, and the face is large and fox-like, with none of the large ears or distinct nasal apparatuses that distinguish other bat species.

Conservation status: P. poliocephalus is considered Vulnerable by the IUCN. Populations are declining largely due to habitat destruction. Many individuals are also killed by farmers, who consider them to be pests.

Photos

Vivien Jones

Shane Ruming

Andrew Mercer

#grey-headed flying fox#Chiroptera#Pteropodidae#fruit bats#flying foxes#bats#mammals#tropical forests#tropical forest mammals#tropical rainforests#tropical rainforest mammals#deciduous forests#deciduous forest mammals#urban fauna#urban mammals#oceania#australia#east australia#biology#zoology#ecology#animal facts

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

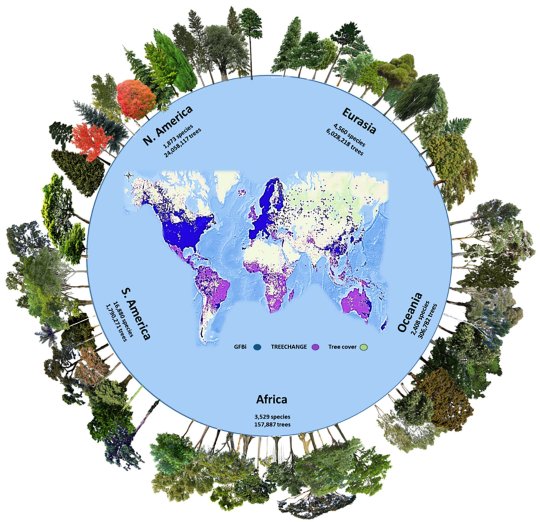

Diagram showing the number of tree species and the estimated tree population of the world in 2022.

“The number of tree species and individuals per continent in the Global Forest Biodiversity Initiative (GFBI) database. This dataset (blue points in the central map) was used for the parametric estimation and merged with the TREECHANGE occurrence-based data (purple points in the central map) to provide the estimates in this study. Green areas represent the global tree cover. GFBI consists of abundance-based records of 38 million trees for 28,192 species. Depicted here are some of the most frequent species recorded in each continent. Some GFBI and TREECHANGE points may overlap in the map. Image credit: Gatti et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2115329119.“

Source: Tom Kimmerer’s Twitter page

#scientific diagram#trees#forestcore#botany#katia plant scientist#rainforest#taiga#woodland#forests#Forest#tree cover#nature#science#ecology#natural history#diagram#infographic#big data#biology#plant biology#bioinformatics#science news

107 notes

·

View notes