#queer chinese history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Golden Orchid Societies

Golden Orchid Societies were communities of women in the Pearl River Delta region of southern China who chose not to marry, or not to live with their husbands. Golden Orchid sisters may have been asexual, aromantic, women-loving-women, or had other reasons to avoid traditional marriage.

Golden Orchid Societies generally consisted of small groups of five or so women, who lived together and pooled their financial resources. Instead of marrying a man, some Golden Orchid sisters had a solo wedding, showing their desire to remain independent from a husband. Like other weddings, these weddings were family affairs, with a banquet funded by the woman’s parents.

Many Golden Orchid groups lived together for their whole lives, and saved up to retire as a community.

Learn more

[Image description: Liang Jieyun, 85, and Huang Li-e, 90, two of the last surviving Golden Orchid sisters; they are two elderly Chinese women, facing the camera and photographed close up]

#golden orchid societies#chinese history#queer history#women's history#wlw#lesbian history#ace history#asexual history#queer chinese history#lgbt#lgbtq

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two of the most famous gay couples in Chinese history are also the sources of some of the most recognizable queer symbols in China: the bitten peach and the torn sleeve. Stories that are partially legend, partially based in some reality, have expanded beyond what anyone could have imagined and shifted from a romanticized look at a homosexual romance to a term to be clung to as a historical hook from past to present; a reminder that there is a precedent for the kind of queer love that continues in contemporary China, despite attempts to stamp it out.

Support Making Queer History on Patreon

Send in a One-Time Donation

#bitten peach#cut sleeve#chinese queer history#chinese history#lgbt history#queer history#gay history#making queer history

451 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's wild that the whole global trend of gay-focused happy ending romance shows and movies has only been going on for *looks at calendar* a measly ten years!

Just ten years ago. 2014. That's when you get the discovery of a market for queer romance series and films with happy endings. That year the OG Love Sick in Thailand came out. Brazil puts out The Way He Looks, which deserves so much more credit than it receives for influencing the aeshtetics of the genre. Looking premieres on HBO, and although it had low ratings, it's an important touchstone. And, despite Nickelodeon’s censorship and shifting the program from tv to its website, the Legend of Korra confirms Korrasami in its season finale.

The next year, in 2015, we get Love Sick season 2, and China, pre-censorship laws has a few options: Happy Together (not the Wong Kar Wai one lol), Mr. X and I, and Falling In Love with a Rival. Canada, premieres Schitt's Creek. In the US, Steven Universe reveals Garnet as a romantic fusion between two female characters, and will proceed to just be so sapphic. Norwegian web series Skam premieres and sets up a gay protagonist for its third season, which will drop in 2016 and entirely change the global media landscape.

Then, 2016! This is the MOMENT. That aforementioned Skam season happens. Japan puts out the film version of Ossan's Love and anime series Yuri!!! on Ice. China has the impactful Addicted Heroine, which directly leads to increased censorship. The US has Moonlight come out and take home the Oscar. In Thailand, GMMTV enters the BL game and Thai BL explodes: Puppy Honey, SOTUS, Water Boyy, Make It Right, plus, the Thai Gay OK Bangkok, which, like its influence, Looking, is more in the queer tradition but introduces two dramatically important directors to the Thai BL industry, Aof and Jojo.

By 2017, Taiwan enters the game with its History series. Korea’s BL industry actually kicks off with Method and Long Time No See. Thailand’s got too many BLs to mention. Call Me By Your Name, though not a happy ending, makes a big splash that will send ripples through the whole genre, and God's Own Country offers a gruff counter-argument to problematic age differences and twink obsessions. This is also the year of Netflix reboot of One Day At a Time bringing some wlw to the screen, and the Disney Channel has a main character come out as ‘gay’ on Andi Mack ( I’m am ready to throw fists with anyone who thinks the Disney Channel aesthetic isn’t a part of current queer culture). And I'd be remiss not to mention the influential cult-following of chaotic web-series The Gay and Wondrous Life of Caleb Gallo: "Sometimes things that are expensive...are worse."

All this happened, and we hadn’t even gotten to Love, Simon, Elite, or ITSAY, yet.

Prior to all this there are some major precursors some of which signaled and primed a receptive market, others influenced the people who'd go on to create the QLs. Japan has a sputtering start in the 2010s with a few BL films (Takumi-Kun, Boys Love, and Jujoun Pure Heart). Most significantly in the American context, you have Glee, and its ending really makes way for the new era that can center gay young people in a world where queerness, due to easy access to digital information, is less novel to the characters. And the QL book and graphic novel landscape was way ahead of the television and film industries, directly creating many of the stories that the latter industries used.

There's plenty of the traditional queer media content (tragic melodramas and independent camp comedies) going on prior to and alongside QL, and there are some outlying queer romance films with happy endings that precede the era but feel very much akin to QL genre tropes and goals, many with a focus on postcolonial and multicultural perspectives (Saving Face, The Wedding Banquet, Big Eden, Maurice, My Beautiful Launderette, and Weekend). I don't mean to suggest that everything I’ve listed ought to be categorized as QL.

Rather, I want to point out how all of these new-era queer romance works are in a big queer global conversation together, in the creation of a new contemporary genre, a genre that has more capacity and thematic interest to include digital technology and normalize cross-cultural relationships than other genres (there's a reason fansubs and web platforms are so easily accepted and integrated to the proliferation genre).

You're not too late to be part of the conversation. Imagine being alive in the 1960s and 70s and participating in the blossoming of the sci-fi genre. That flowering is where gay romance sits now. Join the party.

#just constantly gob-smacked to be alive right now#i know there's plenty of reason to be horrifically distressed about the condition of the world#queer history#thai bl#japanese bl#korean bl#chinese bl#skam

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Top", "Bottom" Discussion in Unknown ep. 12

The Office Gossip Scene

[Edited on 10th May; changes under clarification headings]

Now that the Unknown has resurrected the conversation about gong shou, let’s talk about it. The what and the why, so to say. Thank you @1serotonindeficientgirl (whose post inspired mine).

I welcome critiques and corrections. So, please feel free to do so.

Scenes and subtitles

The discussion in the episode starts with Wei Qian’s staff gossiping about his relationship with Wei ZhiYuan. One of the staff members comments that Wei Qian is like a little lamb (小绵羊) when it comes to his little brother:

只要遇到他弟弟 就像小绵羊

Someone replies with the following idiom:

羊入虎口

(Literally: “a sheep enters a tiger's mouth”)

It means to enter a dangerous situation where one will certainly suffer [Source: Wiktionary].

The female employee (who witnessed their kiss) asks San Pang:

三胖哥谁是羊谁是虎啊 - Who is the lamb (羊; sheep) and who is the tiger (虎)?

This has some employees confused and they ask for an explanation. They receive the following reply:

就���攻跟受的差别啊 – [it means] between them, who is gong and who is shou?

One of the staff members repeats the unfamiliar terms:

攻受 – gong shou

and the fu-nu (腐女; fujoshi) offers an explanation:

好啦姊姊教你们 – let this elder sis explain

老虎看到羊会 – the tiger upon seeing the lamb…

Before she can complete her explanation, Wei Qian moves into the scene accompanied by the growl of a big cat. The gossipers disband.

In the end our fu-nu expresses their support for Wei Qian’s relationship with Wei ZhiYuan. Before she runs off, she throws him the question:

你们谁是攻谁是受啦 – between the two of you, who is gong and who is shou?

In the next shot Wei Qian is alone. He flexes his muscles and comments:

很明显吧 - It's obvious, isn't it?

[END OF SCENE]

Everyone at that office seems pretty close. The staff calls Wei “Qian ge” 谦哥 (first name + brother) and not as “Mr. Wei” (as the English subtitles suggests). Looks like Lao Xiong (emphasis on Lao = old) is the only one who clearly disapproves of such gossipmongering.

Notice how the terms gong and shou were translated directly into top and bottom in English subtitles. While that’s technically correct, there’s some nuance missing.

While there are tongzhi (同志;queer) people who use the terms gong and shou, these are not the most popular terms for top and bottom in the tongzhi community. This series specifically uses the terms gong (攻) and shou (受). Why? We’ll get to that in a minute.

In a BL, being shou means that character is the bottom in that particular ship. That character could be top, bottom, versatile or neither in another ship. A character is a bottom (as we use the term in English) only when that character is an absolute shou (sou uke in Japanese). An absolute shou is invariably shou. No matter which ship he becomes part of and no matter who he is paired with, he will be the shou. Similar difference exists between the terms “top” and “gong”.

English subtitles use ‘top’ and ‘bottom’ from the get-go. There is no need to explain what those terms mean. But that’s not the case with gong shou – only 腐 (fu) people (BL fans) really knows what those terms really mean and thus warrants explanation.

Clarification

[Edited. Thank you @abstractelysium and @wen-kexing-apologist for contributing to the conversation.]

As noted in the convo, Wei Qian is pretty ferocious in the office and is only gentle when it comes to Wei ZhiYuan. So, it is normal that gossiping irrespective of topic would end as soon as he arrives. Also, I think Wei Qian didn’t get what gong shou means other than allusion to tiger and lamb. The original language dialogues don’t make it clear that gong and shou means top and bottom (in a ship). [The English subs gives off that impression since gong and shou were simply translated.] Moreover, those terms are danmei literacies that has entered dictionaries but not necessarily public knowledge.

It is like an insider joke for fu-people made possible by Wei Qian’s ignorance. That wouldn’t have worked on Wei ZhiYuan who read danmei while growing up. That wouldn’t have worked if the fu nu (fujoshi) stuck around to explain what that means.

Usually in such conversations in BL, fu-people are shown to be mistaken: they either mess up the ship/dynamic (Love By Chance 1) or the character(s) in the ship deliberately trick them (Counter Attack). It is almost always played out with seme/gong’s approval in BL - not sure if that dynamic between fu-people & seme aka gong character ever appeared in any live-action dynamic. The trigger of this scene is Wei ZhiYuan’s deliberate choice of actions: PDA, kiss in the office right in front of a staff member.

BL literacies

BL is a media genre in itself with different sub-genres, genre conventions and classic works. It sure has a lot of overlap with other genres:

Romance as well as GL – they coevolved. They share mothers and other ancestors.

Queer – Is it really a genre? Even if one were to ignore queer as method in academia, it is still so complex.

Let me quote Taiwanese tongzhi author Chiang-Sheng Kuo:

… what exactly is queer literature? Is it queer literature if queer people like to read it, or is it only queer literature if there are queer characters in the books? Or is it an appendage of the queer movement? If a queer author writes a book without queer characters, does that represent a certain aspect of queer culture?

(You can find the whole interview here.)

Just as danmei (耽美; Chinese BL) has its roots in Japanese BL, so is gong (攻) and shou (受) from seme (攻め) uke (受け).

gong shou aka seme uke dynamics

Mother of BL, Mori Mari, didn’t come up with it, nor did her father Mori Ogai. Both she and her father, among the other dozen tanbi (耽美; same writing as danmei but different readings cause different languages, and different meanings cause different cultures) authors inherited it from authors before them who wrote on contemporaneous and historic Japanese male androphilia.

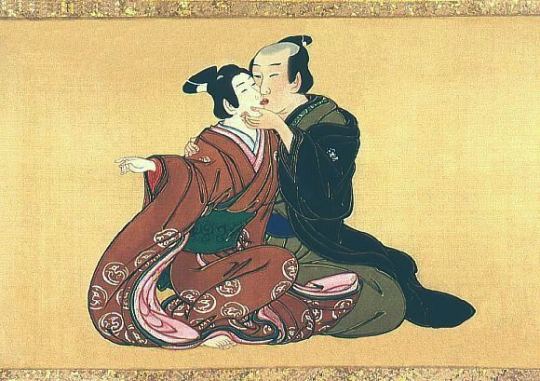

Spring Pastimes. Miyagawa Isshō, c. 1750 | seme uke dynamics in nanshoku pre-dates BL by hundreds of years.

While there is no dearth of riba (versatile) characters in BL, seme uke dynamics is:

a genre specialty. There are similar words in use in GL as well.

an enduring connection to the past of where BL was born.

remnants of a particular model of queerness; an alternative to LGBTQIA+ form of queerness.

What’s there in the scene

There is something hidden in the euphemistic explanation. On the face of it tiger devouring a lamb would be allusion to tiger gong devouring (topping) lamb shou.

But then tiger is a big cat and lamb is a herbivore. Neko (ネコ), the Japanese queer term for “bottom” means cat (etymology is obscure with this one). The term herbivore (草食) when used to describe a man means that man is masculine in a non-hegemonic way. In the series, Wei Qian embodies the hegemonic masculinity while Wei ZhiYuan is a quintessential grass-eater.

So, the description of lamb being devoured by a tiger would not be associated as simply as with the terms gong and shou especially when it comes from Taiwan which has been historically more connected to Japanese BL than any other BL producers (Sinophone or otherwise). This connection was highlighted during 魏之远 Wei ZhiYuan's naming scene where Le Ge used the borrowed Japanese possessive particle (の; no).

の = 之 (zhī)

The big cat sound effect for Wei Qian in particular adds to this. Wei Qian’s character is best described as a queen shou.

女王受 Queen shou: A shou who is as proud as a queen, and would devour gong. (source)

Wei Qian and Wei ZhiYuan’s ship is best described by Priest (the author of Da Ge, source novel of Unknown):

经典款毒舌女王和屁颠屁颠的忠犬组合 – paring of a classic, sharp-tongued queen and a tail-wagging loyal dog.

BL literacies & Affective learning

BL kind of has its own language (with words like gong shou), which fans use to share ideas and feelings. This secret language is what academics call ‘literacies.’ BL fans are all in on this and have their own ‘ways of behaving, interacting, valuing, thinking, believing, speaking, and often reading and writing’. Through ‘various visual, conceptual and textual literacies’, BL fans weave ‘an intertextual database of narrative and visual tropes which readers draw upon to interpret BL’. BL literacies is learnt through ‘affective hermeneutics – a set way of gaining knowledge through feelings.’ Audience learn BL literacies from BL works ‘which eventually leads to their active engagement’ with other BL fans. (source; Kristine Michelle L. Santos explains it in the context of Japanese BL but it applies to all BL media irrespective of where it is from.)

That scene in Unknown was set up to familiarize audience with BL literacies – not only those specific words but also the larger practice of imagining character pairing and indulging in that imagination. This is evident from the overall jubilant tone of the scene and the camera work. It is a celebration of moe. That is why we have a character who is not only a fu-nu but also willing to be openly fu-nu in that setting, sharing BL literacies and her colleagues interested to learn.

For other examples, check out Thomas Baudinette’s book Boys Love Media in Thailand: Celebrity, Fans, and Transnational Asian Queer Popular Culture. He has a chapter dedicated to explaining how genre conventions were taught to the early audience of Thai BL through similar scenes.

Why must they do this? Why break the fourth wall like this? To get more people interested in the intricacies of BL and to get them to participate in the culture. BL is created by fu-people and BL literacies are their tools and source of joy. BL must draw in more people to keep BL culture going. Commercialized BL we have today is the result of an affective culture formed over the years. It is built on years of labor of authors and their audience. I mean, look at the Unknown. This BL employs the well-developed Loyal Dog gong x Queen shou dynamics. Apart from that which the series took from the novel, it also drew upon other common BL beats to tease the relationship between Dr. Lin and his senior.

Teaching BL literacies is political. When Mainland Chinese government gets dangai productions to change names and relationships of characters (among other things), it is to prevent live-action audience from discovering BL as a genre with it disruptive potential. It is not only character's names and relationships that are changed. There are entire sub-genres of danmei (such as 高干) that got wiped out by censorship.

When a Taiwanese BL not only retains the character names & relationships and shows relatively explicit intimate scenes but also actively promotes BL literacies, it is an act of resistance. Discussion of gong shou, being genre specialty, manages to do so. Interestingly, they are doing it in an adaptation of a novel by Priest who has a particular reputation with self-censorship. That scene is not part of the source novel.

Heterosexual & gong shou

Association of bottom with the feminine (female or otherwise) has its roots in medicalization (and pathologization) of homosexuality in the west (such as through theories by scientists and doctors like Richard von Krafft-Ebing). This “knowledge” subsequently spread across the globe and was adopted to varying degrees and forms.

Moreover, the terms gong and shou applies to heterosexual pairing too.

BG (boy girl) ships have male gong and female shou

GB (girl boy) ships have female gong and male shou. [If this is interesting unfamiliar territory, check out the series Dong Lan Xue (2023).]

Moreover, if one is willing to look beyond LGBTQIA+ form of queerness (which is born and brought up in America), one can see other queer possibilities. For example, Kothi-Panthi queerness in South Asia which is characterized by explicit presentation of top bottom dynamics. There are very many similar forms of queerness in other parts of Global South.

In many cultures, sexuality doesn’t inform identity but sexual preference does. That’s why is you are to ask a kothi-panthi couple which one of you is the bottom, the kothi would tell you without hesitation: “I am.” Might even asked you in turn, “Couldn’t you tell?” For them, sexual preference (being kothi) rather than sexual orientation takes center stage. This is the inverse of how LGBTQIA+ form of queerness looks at it. While LGBTQIA+ model of queerness focuses on sexual orientation (being pan, ace, gay, etc.) as something that can be freely discussed but sexual preference (top, bottom, versatile, side, etc.) is considered private.

*Just to be clear, “kothi” is a term of self-identification. It means that the person is a bottom. Panthi is not self-identification. That’s how kothi address the men who top them.

While thanks to westernization LGBTQIA+ form of queerness enjoys more visibility, I think it is better to consider it as one type of queerness rather than the only model of queerness. Gong shou dynamics doesn’t fit into LGBTQIA+ form of queerness because it comes from another, much-older nanshoku model of queerness that made its way into Japan from China, hundreds of years ago. Friction between different models of queerness is common where ever they interact. In 1970s, Japan was witness to public debates between a younger, westernized Japanese queer activist Itō Satoru and other Japanese queer activists such as Fushimi Noriaki and Tōgō Ken who were rooted in indigenous tradition of male-male sexuality.

[Itō Satoru’s] insistence on the necessity of adopting western models of gay identity and coming out have brought him into conflict with other activists such as Fushimi Noriaki and veteran campaigner Tōgō Ken.

Interpretation and Orientalism: Outing Japan's Sexual Minorities to the English-Speaking World by Mark McLelland

Clarification

[Edited. Thank you @wen-kexing-apologist for contributing to the conversation.]

Under the LGBTQ+ model of queerness, it maybe considered inappropriate to have conversation about “top” “bottom”, especially in the office, going as far as to ask that to Qian ge. From that perspective, the BL audience (especially those who are unfamiliar with the terms gong and shou) are fair in their assessment of that scene being out of place or outright offensive.

I think things might have been a bit different if the subtitles retained the terms gong shou instead of “top” “bottom” since they aren’t exactly the same thing. That would have had the desired effect (of introducing BL literacies - gong shou in the context of 强强 (strong gong x strong shou) pairing) without unintended consequence.

What is considered rude under the LGBTQ+ framework is an essential part of fu culture. It is like addressing Wei Qian as just Qian – that could be considered rude in the original language but pretty normal in English. Different cultures, different norms, so to speak. It is only polite to be mindful of the cultural differences and avoid discussing about sexual preference where it is considered inappropriate.

As for the normalization of fu culture (especially discussions of gong shou), in my opinion the didactic scope of Unknown is undermined by the very fact that it is primarily a gǔkē danmei (via adoption (收养)) with tongyangxi vibes (highlighted multiple times by San Pang in the novel) associated with Wei ZhiYuan.

Somehow fu-culture gets judged by those who consume products of that culture. Everyone is happy with fu-cultural products as long as fu-people don't discuss who is gong and who is shou.

Why are fu-culture and BL always judged based on a culturally alien lgbtq+ form of queerness? Why must BL be arm-twisted to fit into norms of lgbtq+ form of queerness just because that is the most mainstream form of queerness?

-

That’s not much a conclusion but this is already so long. I really hope it gives you something to think about.

If you are interested, here's more.

#boys love#danmei#taiwanese bl#bl meta#bl history#bl analysis#unknown the series#unknown the series analysis#unknown the series meta#unknown#priest novels#unknown bl#unknown series#unknown the series spoilers#taiwanese series#taiwanese drama#chinese bl#chinese queer culture#danmei tropes#danmei novels#bl tropes#bl trivia#bl taiwan#unknown bl meta#unknown bl analysis#bl critique#bl novel#bl drama#yuan x qian#zhiyuan x qian

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wayson Choy (deceased)

Gender: Male

Sexuality: Gay

DOB: 20 April 1939

RIP: 28 April 2019

Ethnicity: Chinese

Nationality: Canadian

Occupation: Writer

Note: Is considered one of the most important pioneers of Asian Canadian literature in Canada, and as an important figure in LGBT literature as one of Canada's first openly gay writers of colour to achieve widespread mainstream success.

#Wayson Choy#lgbt history#chinese history#gay history#lgbt#lgbtq#mlm#bipoc#lgbt asians#qmoc#queerness#homosexuality#male#gay#1939#rip#historical#chinese#asian#poc#canadian#writer#first

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I read up on Spirit World to learn more about Xanthe and naturally I was curious with how Johnstantine was written. The story is,,,on the spectrum of "alright" to "okay" for me. I'm of the same opinion of most Hellblazer readers who think "oh that's neat, I wish Constantine was in it though" (it's quippy DC!Constantine, not much to write home about). But I'm also in a unique position when reading this comic. I consider myself a Vertigo Hellblazer purist for the most part but I can't deny the appeal Spirit World has for someone like me.

As much as I love and enjoy reading through og Hellblazer, there is a level of inaccessibility for someone like me reading it. Sometimes I take long breaks from reading Hellblazer because I get frankly fed up with outdated racist moments or arcs. Maybe Johnstantine says or does something racist that puts me in a bad mood from reading. So a story that says "John Constantine hangs out with a new Chinese nonbinary hero" is very appealing for someone like me.

I was hoping to feel catharsis reading Spirit World, seeing so much of my identities in a story and John Constantine interacting with it. But it didn't meet my expectations. I don't think DC!Constantine could give me that. If I'm honest, Constantine really didn't need to be in this story. For the record, this isn't me wanting Vertigo!Constantine to be racist to Xanthe or anything, of course I don't want that. I was hoping for more human moments of recognition. Especially queer solidarity. It felt very surface level for me. Maybe I can do something about that.

Can't outdo the art though ARE YOU KIDDING ME HOLY COW

#ramblings#jesncin dc meta#as a chinese androg person who gets sir'd or ma'am'd interchangeably that is not how a child would react to me lmao#there's moments where it could've gotten really intersectional and beautiful and it just didn't sadly#alan scott's solo in terms of queer culture- history- context absolutely owns and has heightened my standards

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghost Story: a new musical is up on YouTube!

Two love stories between Chinese American and Polish American men haunt the same Montana ranch house — one century apart. As past and present intertwine, the lovers confront long-held fears in their quest to determine if they love one another for the right reasons.

youtube

GHOST STORY is a new musical exploring queer interethnic intimacies between working-class immigrants in the early Mountain West, as well as the complicated racial past of modern gay relationships. Through a story about love, culture, and identity, the show asks: In making meaning from the overwhelming tragedies of queer history, how do we balance seeking truth and beauty?

This presentation includes mature language and some mature themes. Stream our live cast album here on Spotify (and look up Ghost Story Melliot on other streaming services to find it!)

#ghost story musical#melliot#musical theater#musical theatre#new musical#musicals#queer history#lgbtq#trans#transmasc#gay#theater#theatre#aapi#chinese american#polish american#Youtube

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Some special perspectives"

Wang Yunkai on instagram

#meet you at the blossom#wang yunkai#myatbsource#mine#just a guy who made history of having gay sex and kissing in a chinese period queer show getting some fruit and vegetables

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS IS SO COOL!! i did not know about this!!

basically the article is talking about "the golden orchid society", a society of chinese lesbians/wlw who rejected heteronormativity from the 1600s-1900s, also some ace/aro and even cishet women who rejected the standard. very cool read!!

#the golden orchid society#golden orchid society#queer history#lesbian#lesbians#sapphic#sapphics#wlw#ace#aro#aroace#queer#lgbtq#lgbt#lgbtq+#china#chinese history#ancient china

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man I just finished Babel and I was excited to read discussions online because there's so much going on in it with so many little things and just....angry white people. Everywhere. Truly a dead dove moment.

#the “you can't trust white people” theme might be a little like...aggressive but gosh you are not wrong#rf kuang#it was such a good depiction imo#it felt so much like explaining to white (or sometimes black) people what the problem is#especially felt like explaining being queer to straight people#i feel like a lot of people have at least a vague intellectual understanding of racism even if they don't see the racism#babel an arcane history#babel or the necessity of violence#also she captured a fair bit of mixed race and chinese diaspora feelings#also also i can see the relationship to the secret history and the fact that this is a rebuttal of dark academia while being dark academia#also realizing i dislike dark academia tbh#just...the ye olde university feeling is not my style#hence i went to engineering school where it had a je ne sais quois that i think is widespread neurodivergence#the good old boys clubs just do not interest me and i cannot really care about their lifestyles#it's not bad mind you it's just not for me#babel however is the exception that made me realize i dislike dark academia#hated the cloisters#got a rec for the secret history and had negative interest in that#i really want more and better depictions of engineering school and like...any similar experiences to what i had#they just do things like the social network where it's still a rich kid good old boys club but now with “nerds” who are just business majors#like the big tech guys of the modern era are primarily business guys not like...building computers in their basement#give me aome barely functional people who lean heavily into being weird once they go to school and they have hijinks like#updating archlinux and giving the other people shots if you get xyz system working again#first to get x11 back? REST OF YOU SHOTS. first to get internet back? SHOTS. sound? SHOTS. window manager? SHOTS.#or like...drama over your roommate not knowing how to do basic adult things like boil water or do laundry

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE AUDACITY!!!! OF THAT MAN I CANNOT BELIEVE HE JUST DID THAT HE HE HE WEI WUXIAN “let’s celebrate” HE SAYS WHILE LITERALLY MIMING CUTTING HIS SLEEVE!!! IN FRONT OF JC AND NHS!!! FULLY PROPOSITIONING HIM!!!! fuck lwj has the self-control of an actual god to not either punch him or kiss him right there the audacity i can’t believe it i can not believe my eyes wei wuxian is an absolute menace of a man

#god maybe i shouldn’t show this to my mom#i suppose it’s a cultural ref you won’t get if you’re not either really interested in queer world history or actually chinese#but that scene is so fucking suggestive idk what kind of blinkers you’d have to have on to miss the intended meaning#im#im flabbergasted he really did that#mdzs#wangxian#gwen’s liveblogging again

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ace awareness week: Golden Orchid Societies

Golden Orchid Societies were communities of women around the 19th and early 20th centuries in southern China who chose not to marry, or not to live with their husbands. Some Golden Orchid sisters had a solo wedding, showing their desire to remain independent from a husband. These women were known as "self-combed women", because they would dress their own hair before the ceremony, rather than having it combed by a married female relative, as was normal in a male-female marriage.

Some Golden Orchid sisters may have been asexual or aromantic. Others may have been women-loving-women, or had other reasons to avoid traditional marriage. Nonetheless, their history provides us with an insight into ace history, and what historical possibilities there have been for asexual people.

Check out our podcast to learn more

[Image: Liang Jieyun, 85, and Huang Li-e, 90, two of the last surviving Golden Orchid sisters. Tania Branigan for the Guardian]

#ace history#ace awareness week#asexual awareness week#ace week#asexual history#asexuality#lgbt#lgbtq#queer#golden orchid societies#chinese history

402 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Golden Orchid Society was a collection of organizations in South China that began during the Qing dynasty and existed from approximately 1644 to 1949 when they were banned because they were associated with an attempt to overthrow the Manchu Emperor. Over 300 years, however, they created an order of women who stood in solidarity with other women against heterosexual marriages that were oppressive at best and far too often abusive. While some of the women may have been heterosexual and avoided marriage for reasons unrelated to their sexuality, the association clearly made a space for members who were lesbians or bisexuals. Queer women found the safety and family in the Golden Orchid Society that their biological relatives had often never provided them.

Support Making Queer History on Patreon

Send in a One-Time Donation

#golden orchid#chinese history#lgbt history#china#queer history#queer#lgbt#lesbian history#making queer history

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queer Women in Qing China: Chen Yun & Han Yuan in Six Records of a Floating Life

(Pak Suet Sin as Chen Yun (left) and Yam Kim Fai as Shen Fu (right) in Madam Yun, dir. Chu Kea, 1960)

Despite being written by a relatively unremarkable man, Shen Fu's (沈復) Qing-era autobiography Six Records of a Floating Life (浮生六記) captured the public imagination for its depiction of an unusually loving married couple - namely the author and his wife Yun - and for being very sad, because the wife died young after a protracted battle with illness and poverty. Their tragic tale has inspired films, TV series, stage plays, Chinese operas, and musicals.

But for some reason (spoiler alert: it's homophobia), as far as I can tell (see note 2 below the cut), the derivative media all fail to mention that while Yun certainly loved Shen Fu, there was also someone else she loved-- a female courtesan named Han Yuan, whom she convinced her husband to take on as concubine. Although there are only a few references to Han Yuan throughout the book, her impact is outsize, making her absence from the various adaptations all the more glaring.

So let's try to rectify things, shall we? Extracted here are all the references to the relationship between Yun and Han Yuan contained in Six Records of a Floating Life - although I haven't included all the other nods to Yun's fruitiness, so do check out the book in full - click below!

Overview

The happily married Chen Yun falls for the female courtesan Han Yuan and the two soon become sworn sisters (see note 1 below). Then, to ensure they can remain together, she manages to persuade her husband to take the latter as his concubine despite his protestations that they cannot afford another mouth to feed. This turns out to have unfortunate consequences: Yun's in-laws, who she was already on thin ice with, are highly critical of the two women's relationship, and have the married couple expelled from the familial home. Further, while Yun and her husband are living elsewhere, a wealthy man pressures Han Yuan into leaving and becoming his wife instead. Yun falls into despair and the heartbreak causes her already-delicate condition to deteriorate, leading to her eventual demise.

Note 1: Sworn kinship is the most widely-available Chinese custom allowing for the formalisation of a relationship between individuals of the same gender, other than those specifically hierarchical in nature (e.g. adoption, godparents, mentorship, etc.). While not primarily romantic in association, there is certainly precedent for it: arguably the most famous Chinese love story, The Butterfly Lovers, focuses on the romance between a man and a cross-dressing woman who swore an oath of brotherhood. Even after the latter reveals that she is female, there are repeated references to their oath, and the man continues to refer to her using familial terms (賢弟/"worthy younger brother" is simply switched to 賢妹/"worthy younger sister"). Note 2: As far as I can tell, Han Yuan really does never come up in the various derivative works. However, there is some (mostly very mild) hinting regarding the in-laws' disapproval stemming in part from Yun's failure to conform to cishet norms; at least three of the adaptations from Hong Kong take as the flashpoint an incident where Yun dresses as a man in order to enjoy the Mid-Autumn festivities with her husband (see the GIF in the header) and is discovered, despite it not having had any negative consequences in the book. (There is such a cross-dressing scene in the 2021 Kunqu opera adaptation, but for some reason, in that version, Yun seems to have been on great terms with her in-laws and there was no disownment at all.) AFAIK the only adaptation that explicitly deals with Yun's queerness is the 1987 dance production from Hong Kong, wherein the disownment happens after a scene which I'll just describe as "the Mid-Autumn Festival incident, but as a boat ride which Yun turns into a threesome between herself, the boat-girl, and her husband". This actually pulls from the source material, as there is a somewhat suggestive episode involving a boatsman's daughter (this is a few pages before Han Yuan is introduced - I did say Yun was fruity)... but it's interesting that the creators decided to depict her queerness through a drunken one-night stand where she's dressed in male clothing (which was not the case in the original, though the boat-girl does still know she's a woman in this version), instead of committing to her much deeper relationship with Han Yuan.

A (probably-incomplete) list of adaptations

Fei Mu/费穆’s 1943 stage play Six Records of a Floating Life/浮生六记 (PRC)

1947 film Six Records of a Floating Life/浮生六记 (PRC) – dir. Pei Chong/裴冲, starring Su Shi/舒适 and Sha Li/沙莉

1954 film Madam Yun/芸娘 (Hong Kong) – dir. Ng Wui/吳回, starring Cheung Wood-Yau/張活游 and Pak Yin/白燕 – full movie

1960 Cantonese opera film Madam Yun/芸娘 (Hong Kong) – dir. Chu Kea/珠璣, starring Yam Kim Fai/任劍輝 and Pak Suet Sin/白雪仙 – full movie; also see my posts on it here and here

1987 dance performance Six Records of a Floating Life/浮生六記 (Hong Kong) – dir. Chan Kai-Tak – full performance

Cantonese opera Shen San Bai and Madam Yun/沈三白與芸娘 (Hong Kong) – multiple productions from different theatre companies across the years – clip

1974 TV drama Madam Yun/芸娘 (Hong Kong)

Zhou Mian/周眠's 2018 Kunqu opera Six Records of a Floating Life/浮生六记 (PRC) – multiple productions – clip 1 | clip 2

Luo Zhou/罗周's 2021 Kunqu opera Six Records of a Floating Life/浮生六记 (PRC) – multiple productions – full performance (w/ English subtitles)

Tian Chenming/田辰明’s 2021 musical Six Records of a Floating Life/浮生六记 (PRC) – multiple productions – clip

2023 Peking opera Six Records of a Floating Life/浮生六记 (PRC) – assorted clips

Extracts from Six Records of a Floating Life, trans. Leonard Pratt and Chiang Su-Hui, 1983, Penguin Books

Part I – The Joys of the Wedding Chamber

(p.48)

In the seventh month of the Chiayen year of the reign of the Emperior Chien Lung I returned from Yuehtung with my friend Hsu Hsiu-feng, who was my cousin’s husband. He brought a new concubine back with him, raving about her beauty to everyone, and one day he invited Yun to go and see her. Afterwards Yun said to Hsiu-feng, “She certainly is beautiful, but she is not the least bit charming.”

“If your husband were to take a concubine,” Hsiu-feng asked, “would she have to be charming as well as beautiful?”

“Naturally,” said Yun.

“From then on, Yun was obsessed with the idea of finding me a concubine, even though we had nowhere near enough money for such an ambition.

(p.49)

[The courtesan Leng-hsiang] had a daughter named Han-yuan, who, though not yet fully mature, was as beautiful as a piece of jade. Her eyes were as lovely as the surface of an autumn pond, and while they entertained us it became obvious that her literary knowledge was extensive. She had a younger sister named Wen-yuan who was still quite small.

At first I had no wild ideas and wanted only to have a cup of wine and chat with them. I well knew that a poor scholar like myself could not afford this sort of thing, and once inside I began to feel quite nervous. While I did not show my unease in my conversation, I did quietly say to Hsien-han “I’m only a poor fellow. How can you invite these girls to entertain me?”

Hsien-han laughed. “It’s not that way at all. A friend of mine had invited me to come and be entertained by Han-yuan today, but then he was called away by an important visitor. He asked me to be the host and invite someone else. Don’t worry about it.”

At that, I began to relax. Later, when our boat reached Pantang, I told Han-yuan to go aboard my mother’s boat and pay her respects. That was when Yun met Han-yuan and, as happy as old friends at a reunion, they soon set off hand in hand to climb the hill in search of all the scenic spots it offered. Yun especially liked the height and vista of Thousand Clouds, and they sat there enjoying the view for some time. When we returned to Yehfangpin, we moored the boats side by side and drank long and happily.

(p.50)

As the boats were being unmoored, Yun asked me if Han-yuan could return aboard hers, while I went back with Hsien-yan. To this, I agreed. When we returned to the Tuting Bridge we went back aboard our own boats and took leave of one another. By the time we arrived home it was already the third night watch.

“Today I have met someone who is both beautiful and charming,” said Yun. “I have just invited Han-yuan to come and see me tomorrow, so I can try to arrange things for you.”

“But we’re not a rich family,” I said, worried. “We cannot afford to keep someone like that. How could people as poor as ourselves dare think of such a thing? And we are so happily married, why should we look for someone else?”

“But I love her too,” Yun said, laughing. “You just let me take care of everything.”

The next day at noon, Han-yuan actually came. Yun entertained her warmly, and during the meal we played a game – the winner would read a poem, while the loser had to drink a cup of wine. By the end of the meal still not a word had been said about our obtaining Han-yuan.

As soon as she left, Yun said to me, “I have just made a secret agreement with her. She will come here on the 18th, and we will pledge ourselves as sisters. You will have to prepare animals for the sacrifice.”

Then, laughing and pointing to the jade bracelet on her arm, she said, “If you see this bracelet on Han-yuan’s arm then, it will mean she has agreed to our proposal. I have just told her my idea, but I am still not very sure what she thinks about it all.”

I only listened to what she said, making no reply.

It rained very hard on the 18th, but Han-yuan came all the same. She and Yun went into another room and were alone there for some time. They were holding hands when they emerged, and Han-yuan looked at me shyly. She was wearing the jade bracelet!

We had intended, after the incense was burned and they had become sisters, that we should carry on drinking. As it turned out, however, Han-yuan had promised to go on a trip to Stone Lake, so she left as soon as the ceremony was over.

“She has agreed,” Yun told me happily. “Now, how will you reward your go-between?” I asked her the details of the arrangement.

(p.51)

“Just now I spoke to her privately because I was afraid she might have another attachment. When she said she did not, I asked her, “Do you know why we have invited you here today, little sister?”

““The respect of an honourable lady like yourself makes me feel like a small weed leaning up a great tree,” she replied, “but my mother has high hopes for me, and I’m afraid I cannot agree without consulting her. I do hope, though, that you and I can think of a way to work things out.””

“When I took off the bracelet and put it on her arm I said to her, “The jade of this bracelet is hard and represents the constancy of our pledge; and like our pledge, the circle of the bracelet has not end. Wear it as the first token of our understanding.” To which she replied, “The power to unite us rests entirely with you.” So it seems as if we have already won over Han-yuan. The difficult part will be convincing her mother, but I will think of a plan for that.”

I laughed, and asked her, “Are you trying to imitate Li-weng’s Pitying the Fragrant Companion?”

“Yes,” she replied.

(Footnote 44 of Part 1, p.153) The Lien Hsiang Pan, a play by Li Yu (1611-?1680). Li-weng was his literary name. Yun’s confirmation that she had this play in mind gives us our principal clue about just what her real relationship with Han-yuan may have been: the play tells the story of a young married woman who falls in love with a girl, and then obtains her as a concubine for her husband so the two women can be together. As van Gulik has pointed out, Imperial China regarded liaisons between women – as opposed to those between men – quite tolerantly. They did not by any means necessarily imply a lack of affection between such women and their husbands (R.H. van Gulik, Sexual Life in Ancient China, Humanities Press, 1974: he discusses female homosexuality on p.163, and the play itself on p.302, where he translates its title as Loving the Fragrant Companion.)

From that time on there was not a day that Yun did not talk about Han-yuan. But later Han-yuan was taken off by a powerful man, and all the plans came to nothing. In fact, it was because of this that Yun died.

Part III – The Sorrows of Misfortune

(p.76)

Yun had had the blood sickness ever since her younger brother Ko-chang had run away from home and her mother had missed him so much that she died of grief. Yun was so distraught she had fallen ill herself. From the time she met Han-yuan, she passed no blood for over a year, and I was delighted that Yun had found such a good cure in her friend, when Han-yuan was snatched away by an influential man who paid a thousand golds for her and also promised to take care of her mother. “The beauty belongs to Sha-shih-li!” I had learned of all this but had not dared to say anything to Yun, so she did not find out about it until one day when she went to see Han-yuan. She returned weeping, and said, “I had not thought Han’s feelings could be so shallow!”

“Your own feelings are too deep,” I said. “How can that sort of person be said to have feelings? Someone who is used to beautiful clothes and delicate foods could never grow accustomed to thorn hairpins and plain cloth dresses. It’s better that we should be unsuccessful now than to have her regret things later.”

I comforted her repeatedly, but having been so wounded Yun still suffered great discharges of blood. She was bedridden and did not respond to any treatment. She suffered relapses, and became so thin you could see her bones. After a few years the money we owed increased daily, and so did the gossip about us. And because she had pledged sisterhood with a sing-song girl, my parents’ scorn for Yun deepened daily.

(p.78)

[…] a messenger arrived. He had been sent by a woman who had been a sworn sister of Yun’s as a child, who had married a man named Hua from Hsishan, and who had heard of her illness and wanted to inquire after her.

My father, however, mistakenly thought he was a messenger from Han-yuan and so became even angrier, saying, “Your wife does not behave as a woman should, swearing sisterhood with a sing-song girl. Nor do you think to learn from your elders, running around with riff-raff. […]”

(p.79-80)

These were Yun’s parting instructions to our daughter: “Your mother has had a bitter fate and emotions that run too deep; therefore we have had many problems. Fortunately your father has been kind to me, and there is nothing to worry about in our leaving. […]”

(p.86)

I returned to find Yun moaning and weeping, looking as if something awful had happened. As soon as she saw me she burst out, “Did you know that yesterday noon [our servant] Ah Shuang stole all our things and ran away? I have asked people to search everywhere, but they still have not found him. […]”

(p.87)

[…] from then on she began frequently to talk in her sleep, calling out, “Ah Shuang has run away!” or “How could Han-yuan turn her back on me?” Her illness worsened daily.

Finally I was about to call a doctor to treat her, but she stopped me. “My illness began because of my terribly deep grief over my brother’s running away and my mother’s death,” said Yun. “It continued because of my affections, and now it has returned because of my indignation. I have always worried too much about things, and while I have tried my best to be a good daughter-in-law, I have failed.

These are the reasons why I have come down with dizziness and palpitations of the heart. The disease has already entered my vitals, and there is nothing a doctor can do about it. Please do not spend money on something that cannot help. […]”

[…]

(p.88)

Suddenly she fell silent and began to pant, her eyes staring into the distance. I called her name a thousand times, but she could not speak. Two streams of agonised tears flowed from her eyes in torrents, until finally her panting grew shallow and her tears dried up. Her spirit vanished in the mist and she began her long journey.

[…] Alas! Yun came to this world a woman, but she had the feelings and abilities of a man. After she entered the gate of my home in marriage, I had to rush about daily to earn our clothing and food, there was never enough, but she never once complained. When I was living at home, all we had for entertainment was talk about literature. What a pity that she should have died in poverty and after long illness. And whose fault was it that she did? It was my fault, what else can I say? I would advise all the husbands and wives in the world not to hate one another, certainly, but also not to love too deeply. As it is said, “An affectionate couple cannot grow old together”. My example should serve as a warning to others.

#sapphic#wlw#wlw recommendations#asian lgbtq#lgbt history#lgbtq history#lgbt literature#lgbtq literature#literature#chinese literature#six records of a floating life#浮生六記#madam yun#芸娘#celebrating chinese new year with queers in chinese literature#as one should

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

MAY I PRESENT!! CHINESE SOVIET PROPOGANDA!!!!

I

#history#funny#gay#soviet union#chinese#propoganda#queer history#totallynotgay#how did they think that this was not gay#if anybody knows more behind this propoganda tell me#meme

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

very, very special place in my heart for queer docufilms. transgender-focused ones in particular. so much of chinese queer cinema and the queer activist movement owes itself to lgbtq+ documentaries, shorts and movies. many of china's queer filmmakers ended up creating lots of docufilms, some are notable landmark releases as well. there's just such a strong tradition for non-fiction and/or (auto)biographical films in chinese queer cinema. it's cheap and accessible to make, produces something tangibly and compellingly queer as it's real life, plays a big part in archiving queer history, etc. and a major subset of the genre is the trans documentary scene. love love love, always!

#me is mark#china's film history being widely understood as different generations and that's the primary framework for it#six generations of chinese filmmakers from the 1920s till now. the urban generation of the wave of cinema about urban china.#shanghai queer film festival coining the term generation q#and ofc chinese queer directors are dubbed the queer generation known for their prominent documentary work#really love fiction narrative gay movies ofc#but the documovies are very special to me ahhhh

6 notes

·

View notes