#princess of tripoli

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

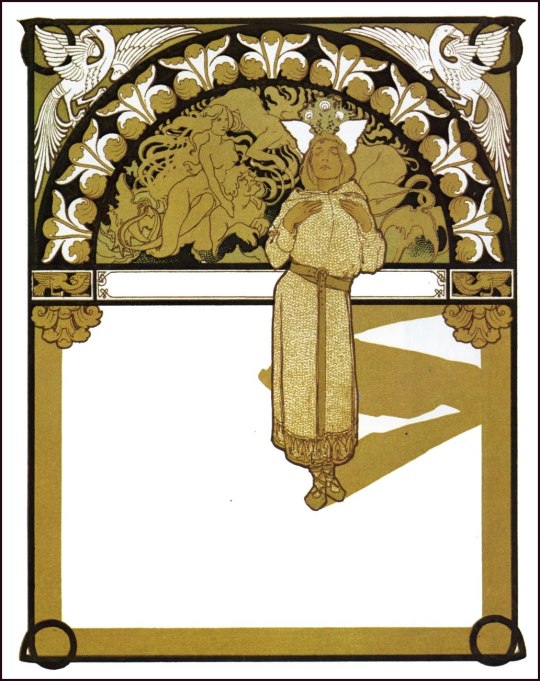

La princesse Mélissinde et le chevalier Bertrand / Princess Melisande and Bertrand

Artist : Auguste François Gorguet (1862-1927)

#auguste françois gorguet#melissinde#melisandre#chevalier bertrand#knight#bertrand#Bertrand d’allamanon#princess of tripoli#la princesse lointaine#edmond rostand#mélissinde#medieva#art#squire

528 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alphonse Mucha ֍ Ilsée, Princesse de Tripoli (1897)

Based on Edmond Rostand's La Princesse Lointaine, written for Sarah Bernhardt in 1895, L'Ilsée, Princesse de Tripoli was commissioned from the author Robert de Flers by the Parisian publisher Henri Piazza.

By the time De Flers had completed his manuscript, Mucha had only three months to prepare 134 coloured lithographs before the edition was due to go to print.

Mucha later wrote of the experience: 'We worked on four stones simultaneously. I did some of the drawings straight onto the stone. Other things, particularly the decorative edgings, I drew on tracing paper which was then passed on to the draughtsmen who continued the work with the colors I specified. I hardly had time to sketch out the motif for an ornament when they came and took it from my hands and got down to work on it.'

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

de Flers, Robert. Ilsée, Princesse de Tripoli. Illus. Alphonse Mucha, limited ed. Paris: Léon Gruel, 1897. source: Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD, USA (not on view)

#books#alphonse mucha#rare books#princesse de tripoli#walters art museum#ilsee princesse de tripoli#leatherbound#leatherbound books#gilt#gilded

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

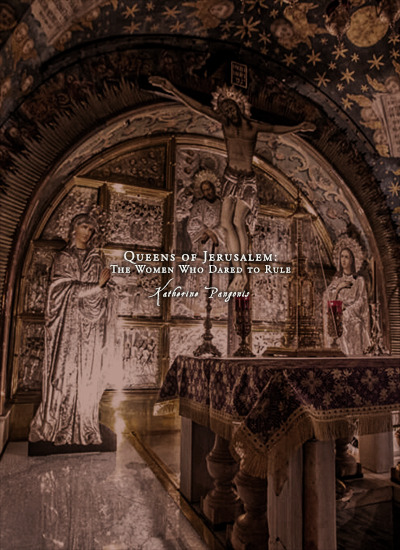

Favorite History Books || Queens of Jerusalem: The Women Who Dared to Rule by Katherine Pangonis ★★★★☆

Despite these clearly documented roles, the vast majority of crusades historians, both medieval and modern, have neglected the roles of women in their histories. This book intends to go some way towards fixing this imbalance by shedding some light on the deeds of women in positions of authority in Outremer: specifically, the dynasty of formidable women rulers founded by Morphia of Melitene, the first crowned Queen of Jerusalem. Her daughters and granddaughters reigned as Queens of Jerusalem, Princesses of Antioch, Countesses of Tripoli, and held many other positions as well. They represent some of the most daring, devious and devoted women that history has ever seen. The source material available on these women is sparse in comparison to what we have regarding their husbands and fathers, but enough survives to construct vivid portraits of these remarkable queens and princesses. ... The two central figures of this book are Queen Melisende of Jerusalem and Queen Sibylla of Jerusalem. These women, grandmother and granddaughter, served as Queens Regnant of Jerusalem, and consequently there is considerably more source material written about them than the other noblewomen of Outremer. However, the lives of their mothers, sisters, nieces and cousins, ruling variously as Queens Consort of Jerusalem and Princesses of Antioch, are also worthy of note, playing pivotal roles in the internal politics of Outremer.

#litedit#historyedit#medieval#crusader states#european history#asian history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vere novo , priori jam mutato consilio , Alienora virgo regia , insignis facie , sed prudentia & honestate prestantior , futura Regina Sicilie , atque cum ea Nymphe obsequiis apte regalibus , accepta benedictione parentum , ab urbe Neapoli gloriosas discessit , per Calabriam , propter maris tedium , usque Regium iter agens : quam discedentem Neapolitane matres , quantum spectantes oculi capere potuerunt , effusis pre gaudio lacrimis affequute sunt.

Gregorio Rosario, Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas sub Aragonum imperio retulere, I, p.456-457

Eleonora was born in Naples in the summer of 1289 as the tenth child (third daughter) of Carlo II lo Zoppo of Anjou, King of Naples, Count of Anjou and Maine, Count of Provence and Forcalquier, Prince of Achaea, and of Maria of Hungary.

Nothing, in particular, is known about her childhood, which she must have spent with her numerous siblings in the many castles of the Kingdom.

She is first mentioned in a Papal bull dated 1300 in which Boniface VIII annulled the marriage of 10 years-old Eleonora to Philippe de Toucy, Prince of Antioch and Count of Tripoli, (the contract had been signed the year before) on account of the bride’s young age and the fact that family hadn’t asked for the Pope’s dispensation.

Two years later, there were discussions of a match with Sancho, the second son (and later successor) of Jaume II of Majorca, but the engagement never occurred.

Finally, in 1302, Eleonora’s fate was sealed. On August 31st 1302 the Houses of Anjou-Naples and of Barcelona signed the Peace of Caltabellotta, which ended the first part of the War of the Sicilian Vespers and settled (or tried to) the problem of which House should have ruled over Sicily. Following this treaty, the old Norman Kingdom’s territory (disputed between the French and Spanish born ruling houses) was to be divided into two parts, with Messina Strait as the ideal boundary line. The peninsular part, the Kingdom of Sicily, now designed as citra farum (on this side of the farum, meaning the strait, later simply known as the Kingdom of Naples ), and the island of Sicily, renamed the Kingdom of Trinacria, designed as ultra farum (beyond the farum).

The Peace of Caltabellotta stipulated that Angevin troops should evacuate the island, while the Aragonese ones should leave the peninsular part. Foundation of the peace would have been the marriage between princess Eleonora of Anjou and King Federico III (or II) of Sicily (“e la pau fo axi feyta , quel rey Carles lexava la illa de Sicilia al rey Fraderich, que li donava a Lieonor, qui era e es encara de les pus savies chrestianes, e la millor qui el mon fos, si no tant solament madona Blanca, sa germana, regina Darago. E lo rey de Sicilia desemparava li tot quant tenia en Calabria e en tot lo regne: e aço se ferma de cascuna de les parts, e que lentredit ques llevava de Sicilia; si que tot lo regne nach gran goig." in Ramon Muntaner, Crónica catalana, ch. CXCVIII). The pact dictated also that once Federico had died, the two kingdoms would be reunited under the Angevin rule. This clause won’t be fulfilled.

The bridal party had to wait until spring 1303 before setting off for her new country since sea storms had damaged part of the fleet and thus delayed the departure. The voyage had cost 610 ounces, where the Florentine bankers Bardi and Peruzzi were asked to advance the payment, and the groom pledged to repay them 140 ounces.

By May 1303, Eleonora and her companions arrived in Messina where she was warmly welcomed and where on Pentecost, May 26th, of the same year she got married to Federico in Messina’s Cathedral (“E a poch de temps lo rey Carles trames madona la infanta molt honrradament a Macina, hon fo lo senyor rey Fraderich, qui la reebe ab gran solemnitat. E aqui a Macina, a la sgleya de madona sancta Maria la Nova, ell la pres per muller e aquell dia fo llevat lentredit per lola la terra de Sicilia per un llegat del Papa, qui era archebisbe, que hi vench de part del Papa, e foren perdonats a tot hom tots los pe cats quen la guerra haguessen feyts: e aquell dia fo posada corona en lesta a madona la regina de Sicilia, e fo la festa la major a Macina que hanch si faes.” in Ramon Muntaner, Crónica catalana, ch. CXCVIII).

After the wedding, most of the bridal party returned to Naples, while the newlyweds proceeded to Palermo.

On July 14th 1305 Eleonora gave birth to the heir, who was called Pietro in honour of the child’s paternal grandfather, Pere III of Aragon. To celebrate his son’s birth, Federico III gifted his bride of Avola castle and the surrounding land, to which will be added the city of Siracusa (in 1314), Lentini, Mineo, Vizzini, Paternò, Castiglione, Francavilla and the farmhouses in Val di Stefano di Briga. This gift would mark the creation of the Camera reginale, which would become the traditional wedding present given to Sicilian Queen consorts, and eventually would be abolished in 1537.

Including Pietro, she would give birth to nine children: Costanza (1304 – post 1344), future Queen consort of Cyprus, Armenia and Princess consort of Antiochia; Ruggero (born circa in 1305 - ?) who would die young; Manfredi (1306-1317) first among his brothers to hold the title of Duke of Athens and Neopatras; Isabella (1310-1349) Duchess consort of Bavaria; Guglielmo (1312-1338) Prince of Taranto and heir to the Duchy of Athens and Neopatras following the death of his brother; Giovanni (1317-1348) Duke of Randazzo, Count of Malta, later also Duke of Athens and Neopatras and Regent of Sicily; Caterina (1320-1342) Abbess of St. Claire Nunnery in Messina; Margherita (1331-1377) Countess Palatine consort of the Rhine.

Through these donations Eleonora became a full-fledged vassal, and had to pay homage to her husband the King. Thanks to official documents, we get the idea that Eleonora tried to manage her lands as much personally as she could do, naming herself vicars, administrators, and granting tariff reductions. Federico indulged his wife as much as he could, although in some cases (like the management of the city of Siracusa) his will was the only one taken into account.

Despite almost every time she was unsuccessful, Eleonora fully embraced her role as mediator between the Aragonese and Angevins. For example, in 1312 her brother-in-law, King Jaume II of Aragon, asked her to dissuade her husband (Jaume’s brother) to ally himself with the Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich VII of Luxembourg since this alliance could generate new friction with the Angevin Kingdom, as well as with the Papacy (with the risk of stalling the Aragonese occupation of Sardinia). After the King of Aragon, it was Pope Clemente’s turn to ask Eleonora to convince Federico to make peace with Roberto of Anjou. In both cases, though, her conciliatory efforts didn’t work.

In 1321 she witnessed her son Pietro being associated to the throne and thus crowned in Palermo (“Anno domini millesimo tricentesimo vicesimo primo, dum Johannes Romanus Pontifex contra Fridericum Regem, & Siculos propter invasionem bonorum Ecclesiarum precipue fulminaret, Fridericus Rex primogenitum suum Petrum, convenientibus Siculis, coronavit in Regem, & patris obitum, inopinatum premetuens, & ut filius qui purus videbatur & simplex, ab adoloscentia regnare cum patre affuesceret patrisque regnando vestigiis inhereret […]” in Gregorio Rosario, Bibliotheca scriptorum ..., I, p. 482). Pietro’s coronation publicly violated the Treaty of Caltabellotta (as the Kingdom should have returned to the House of Anjou), causing the pursuing of warfare between Naples and Palermo. Once again Eleonora’s attempts at peace-making failed miserably, with her nephew, Carlo Duke of Calabria, refusing to even meet her in 1325, after he had successfully raided the outskirts of Messina.

The Queen didn’t have much luck in internal policy too as she failed to appease her husband and her protegé, Giovanni II Chiaramonte. After gravely wounding Count Francesco I Ventimiglia of Geraci (his brother-in-law and one of the King’s trustees), all that Eleonora could do was advise Chiaramonte to flee to avoid the death penalty.

Nevertheless, the Pope still hoped to use the Queen (who, at that time and alone in her Kingdom, was exempted from the Papal interdict) as mediator with her husband, promising to lift the excommunication in exchange for Federico’s backing down. Once again nothing happened.

On June 25th 1337 Federico III died near Paternò. He was buried in Catania since it was too hot for the body to be transported to Palermo (“Feretrum humeris nobiliores efferunt. Adsunt Regii filii, proceresque Regni. Exequias Regina, illustribus comitata matronis, prosequitur.” in Francesco Testa, De vita, et rebus gestis Federici 2. Siciliæ Regis, p.225). After the death of her husband, the now Dowager Queen turned to religion, following the example of those in her family who had consecrated themself to Christ (“At Heleonora certiorem fe de illa consolandi rationem inivit. Ipsa enim , ut Rex excessit e vita, ei, qui omnis consolationis fons est, fese in Virginum collegio Franciscanæ familiæ Catinæ devovit; in hoc Catharinan , & Margaritam filias imitata, quæ in ætatis flore, falsis terrestribus, contemptis bonis, Christ, cui fervire regnare est, in sacrarum Virginum Messanensi Collegio, de Basicò dicto, ejusdem Franciscanæ familiæ fese consecrarant; quod Collegium posteaquam Catharina fancte gubernavit, sanctitatis opinione commendata deceffit” in Francesco Testa, De vita..., p.226).

If Eleonora might have hoped to exert some kind of influence as many other Queen mothers did in the past and would do in the future over their weak-willed royal children, she would soon realize she had a powerful rival in the new Queen consort, her daughter-in-law, Elisabetta of Carinthia. Like Eleonora, the new Queen supported the Latin faction (a group of Sicilian noblemen who opposed the Aragonese rulership over Sicily, hoping the island would be returned under the influence of the Angevins instead). But, while Elisabetta had managed to raise the Palizzis to the highest positions at court, her mother-in-law still supported the Chiaramonte, making it possible for the exiled Giovanni II to return to Sicily, be pardoned by the King and see all his goods be returned. Soon though Chiaramonte resumed his personal feud against the Ventimiglia (also part of the Latin faction) and once again Eleonora's attempt to bring peace failed miserably. Only through Grand Justiciar Blasco II d'Alagona's intervetion, the crisis was averted.

In 1340, the Dowager Queen made a last attempt to appease the new Pope, Benedict XII. Unfortunately, the Sicilian envoys sent to Avignon to take an oath of vassalage (since Norman times Sicily theoretically belonged to the Papacy, who granted it to the Sovereigns who acted as Papal Legates) were treated roughly by the Pope, who declared Roberto of Anjou (Eleonora's brother) as Sicily's legitimate King.

Deeply distraught, the Dowager Queen resolved to definitely retire from public life. She spent what it remained on her life visiting the monastery of San Nicolo' d'Arena (Catania), joining the monks in their religious life. She died in one of the monastery's cells on August 10th 1341. Her body would be buried in the Church of San Francesco d'Assisi all'Immacolata (Catania), the construction of which she had personally promoted in 1329 to thank the Virgin Mary for protecting the city from one of many Mount Etna's eruptions.

Sources

AMARI MICHELE, La guerra del Vespro siciliano

CORRAO PIETRO, PIETRO II, re di Sicilia in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 83

DE COURCELLES JEAN BAPTISTE PIERRE JULLIEN, Histoire généalogique et héraldique des pairs de France: des grands dignitaires de la couronne, des principales familles nobles du royaume et des maisons princières de l'Europe, Vol. XI,

FODALE SALVATORE, Federico III d’Aragona, re di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 45

GREGORIO ROSARIO, Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas sub Aragonum imperio retulere, I,

KIESEWETTER ANDREAS, ELEONORA d'Angiò, regina di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 42

de MAS LATRIE LOUIS, Histoire de l'île de Chypre sous le règne des princes de la maison de Lusignan. 3

MUNTANER RAMON, Crónica catalana

Sicily/naples: counts & kings

TESTA FRANCESCO, De vita, et rebus gestis Federici 2. Siciliæ Regis

#historicwomendaily#historical women#history#history of women#herstory#eleanor of naples#frederick iii of sicily#house of aragon and sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#myedit#historyedit

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

found pdfs of documents decoratifs figures decoratives a THIRD collaborated art nouveau design book mucha worked on and ilsee princesse de tripoli im eating so well

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

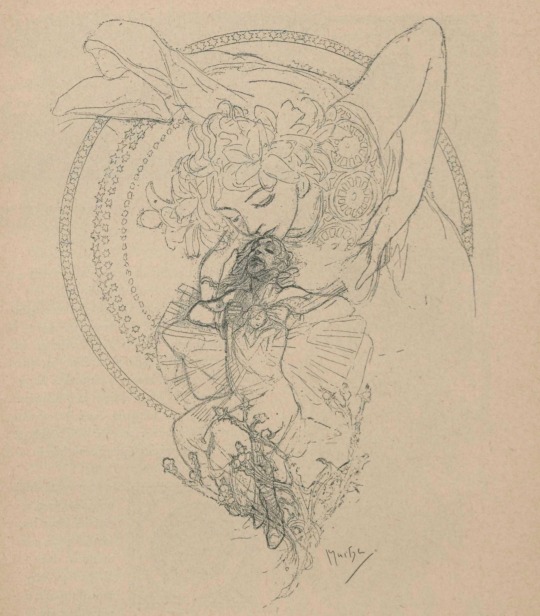

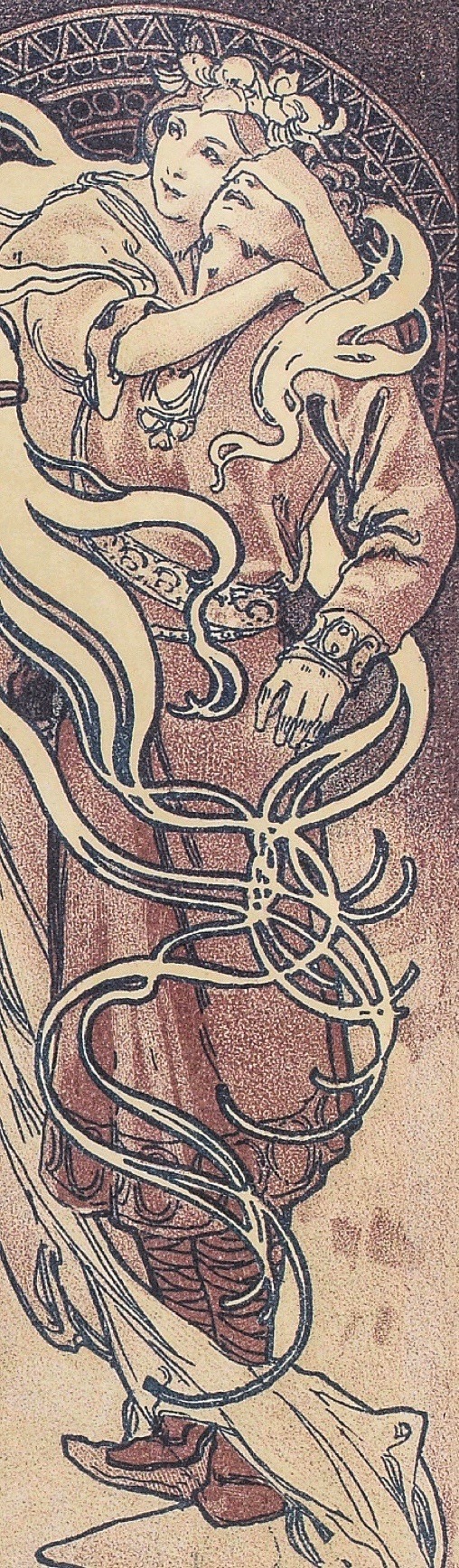

Study for Ilsée

Artist: Alphonse Mucha

166 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Illustrations by Alphonse Mucha, for Ilsée, Princesse De Tripoli by Robert de Flers, based on Edmond Rostand’s play La Princesse Lointaine

1897

courtesy of Kyle Geib on Flickr x x x

#book illustration#illustration#Art Nouveau#Mucha#Alphonse Mucha#Czech#art#Robert de Flers#Ilsée Princesse De Tripoli#Edmond Rostand#La Princesse Lointaine#French#literature#play#novel#turn of the century

553 notes

·

View notes

Text

ILSEE, PRINCESS OF TRIPOLI by Robert de Flers. Illustrated by Alphonse Mucha. Art binding by Léon Gruel. (1897).

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#illustrated book#vintage books#art binding#alphonse mucha#book binding

303 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Illustration from Ilsée, Princesse de Tripoli by Alphonse Mucha (1897)

#alphonse mucha#art#illustration#art nouveau#19th century#19th century art#vintage art#vintage illustration#vintage#czech art#czech artist#books#book illustration#childrens books#princess#fine art#golden age of illustration#classic art

735 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ilsée, Princesse de Tripoli by Robert de Flers

detail

1897

Artist : Alphonse Mucha

353 notes

·

View notes

Note

If Baldwin IV had a wife, it would likely have been a Byzantine princess as his uncle and father had...Baldwin III and Amaury. No romance, just a royal alliance. Consummation sealed the deal. Leprosy was not a cause for annulment, and spouses still had to honor "the marital debt."

Alright, let's talk realism for a minute.

Well, yes to the "marriage as a means of political alliance" part - we are in the middle ages, after all. While they had the concept of courtly love - which was outside the bounds of marriage - genuine romantic love between spouses was quite a rare thing and not something you married for or expected upon entering a marriage. Marriage was mainly to ensure alliances and the continuation of the family line via children. For most people, it certainly wasn't the dramatic affair that it is often presented as in medieval-themed fiction and film: though they may not have loved each other, spouses had to rely on each other in many aspects of daily life, so it was in the best interests of both partners to make the marriage work. It was, in general, not an instrument to suppress women or deprive them of their rights - in fact, in the 11th and 12th centuries marriage customs were changing and the church (yes, the church) actively encouraged granting women the right to agree or disagree to an arranged marriage.

While leprosy may not have been a cause for annulment or non-consummation of an existing marriage, I'm pretty certain it would have been seen as a valid reason to not enter into marriage negotiations in the first place. For one, men afflicted with leprosy tend to have fertility issues, so what would be the point in a marriage to a man who, in all likelihood, will not be able to produce an heir? And two, I imagine the prospective bride would have had a word or two to say on the subject of having to marry and sleep with a fellow who looks like a rotting corpse. I mean, I'm sorry for being shallow for a minute, but even if he had the nicest character imaginable, I would not be able to bring myself to touch a man so covered in sores and rashes. Sorry, but no. For that, you'd have to tie me to the bed - or forcibly drag me out of the nearest monastery medieval me most certainly would have fled to.

Also, as long as the vows had not yet been spoken, parties could withdraw from the marriage contract - with consequences to be expected for the offence given, yes, but it was possible. They didn't even have to give much of a reason. One example of this from the crusader states would be the failed negotiations for a marriage between Raymond III of Tripoli's sister Melisende to the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus in 1160 or so, during the reign of Baldwin III. The Franks, expecting the marriage to take place, raised a large dowry for Melisende, made a ton of preparations ... but the Byzantines delayed, delayed, delayed, until after a year, it was eventually made clear that the marriage would not take place after all, and Manuel married Maria of Antioch instead. As a result, young Raymond went into rage mode, equipped the ships he'd originally had built for his sister with pirates and criminals and let them raid the Byzantine coast. Which is one of the reasons why I think the Byzantines would have looked a little askance at another marriage proposition from the Franks, at least for a few years after that.

So, when trying to imagine a possible marriage for Baldwin, I think a lot of it comes down to the question of when the marriage would have been arranged. I'm not a historian, of course, so if anyone knows better, please feel free to correct me. But I somehow can't see marriage negotiations with the Byzantine empire taking place during Baldwin's childhood (before the leprosy was known), not with his mother in the picture who had effectively been replaced by the Byzantine Maria Comnena, and certainly not later when Raymond was regent during his minority. From that point in time on, the leprosy was also an issue; and when Baldwin was finally old enough to make his own decisions, it wouldn't be long until the Byzantine empire began to spiral into decline and its own problems with the ascent of the child-king Alexios II and then, not much later, Andronikos I seizing power and slaughtering the Roman Catholic inhabitants of Constantinople. So I'd say, all in all, that during Baldwin's lifetime, a marriage with a Byzantine princess would have been rather unlikely.

I think if Baldwin had married, it would probably have been some noblewoman from Europe, and I suppose they would have had to be betrothed from early childhood on, with the wife's family - for some reason - not reneging the prospective marriage once the leprosy was found out. Tbh, though, if I were to write a story about Baldwin (which I am not because there are so many Baldwin fics and novels out there already), I'd probably not give him a wife and opt for a sort of mistress- or courtly-love-arrangement instead, because a proper marriage in his case would, in medieval terms, be largely nonsensical.

Again, sorry for the rant - I hope this makes sense.

#asks#kingdom of heaven 2005#baldwin iv#raymond iii of tripoli#manuel comnenus#maria comnena#yes i probably gave this ask more thought than it warranted#i hope it's not altogether idiotic#but on the bright side: i am done with my thesis and am going to hand it in next week#my supervisor has already had a look at it and said she's very happy with what i've done#so i'm exhausted but happy#anyways#i better answer the remaining asks in my inbox#sorry again for the long wait folks

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Queens of Jerusalem: The Women Who Dared to Rule

Queens of Jerusalem: The Women Who Dared To Rule by Katherine Pangonis is a non-fiction book focussed on the lives of the royal women who ruled in the medieval Middle East (or Outremer) from 1099 to Saladin's conquest of Jerusalem in 1187. These women have been consistently overshadowed by the kings and leaders of the crusades, and this book strives to change that. By putting the Queens of Jerusalem, the Princesses of Antioch, and the Countesses of Tripoli and Edessa to the fore, readers not only get a brand new look into the history of Outremer during the early crusades but they are also reminded that women were present and active during this time in history.

Continue reading...

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ilsée, Princesse de Tripoli - Robert de Flers, lithographies de Alphonse Mucha - 1897 - via Gallica

58K notes

·

View notes

Text

Every French princess ever

Other posts in this series: Every Queen of England ever, Every English princess ever, Every Queen of France ever

Rothilde - daughter of Charles the Bald and Richilde of Provence

Ermentrude - daughter of Louis the Stammerer and Ansgarde of Burgundy

Emma of France - daughter of Robert I and Beatrice of Vermandois (Queen consort of West Francia)

Emma of France - daughter of Robert I and Beatrice of Vermandois (Queen consort of West Francia)

Matilda of France - daughter of Louis IV and Gerberga of Saxony (Queen consort of Burgundy)

Hedwig of France - daughter of Hugh Capet and Adelaide of Aquitaine (Countess of Mons)

Gisèle of France - daughter of Hugh Capet and Adelaide of Aquitaine (Countess of Ponthieu)

Advisa of France - daughter of Robert II and Constance of Arles (Countess of Nevers)

Adela of France - daughter of Robert II and Constance of Arles (Duchess of Normandy, Countess of Flanders)

Constance of France - daughter of Philip I and Bertha of Holland (Princess of Antioch, Countess of Troyes)

Cecile of France - daughter of Philip I and Bertrade de Montfort (Princess of Galilee, Countess of Tripoli)

Constance of France - daughter of Louis VI and Adélaide of Maurienne (Countess of Boulogne and Toulouse)

Marie of France - daughter of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine (Countess of Champagne)

Alice of France - daughter of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine (Countess of Blois)

Margaret of France - daughter of Louis VII and Constance of Castile (Queen consort of England, Queen consort of Hungary and Croatia)

Alys of France - daughter of Louis VII and Constance of Castile (Countess of Vexin, Countess of Ponthieu)

Agnes of France - daughter of Louis VII and Adela of Champagne (Byzantine Empress consort)

Marie of France - daughter of Philip II and Agnes of Merania (Duchess of Brabant)

Isabelle of France - daughter of Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile (Saint)

Isabella of France - daughter of Louis IX and Margaret of Provence (Queen consort of Navarre)

Blanche of France - daughter of Louis IX and Margaret of Provence (Infanta of Castile)

Margaret of France - daughter of Louis IX and Margaret of Provence (Duchess of Brabant)

Agnes of France - daughter of Louis IX and Margaret of Provence (Duchess of Burgundy)

Blanche of France - daughter of Philip III and Maria of Brabant (Duchess of Austria)

Margaret of France - daughter of Philip III and Maria of Brabant (Queen consort of England)

Isabella of France - daughter of Philip IV and Joan I of Navarre (Queen consort of England)

Joan II of Navarre - daughter of Louis X and Margaret of Burgundy (Queen regnant of Navarre)

Joan III of Burgundy - daughter of Philip V and Joan II of Burgundy (Countess of Burgundy and Artois)

Margaret I of Burgundy - daughter of Philip V and Joan II of Burgundy (Countess of Burgundy and Artois)

Isabella of France - daughter of Philip V and Joan II of Burgundy (Dauphine of Viennois)

Blanche of France - daughter of Philip V and Joan II of Burgundy

Blanche of France - daughter of Charles IV and Joan of Évreux (Duchess of Orléans)

Joan of France - daughter of Philip VI and Blanche of Navarre

Joan of Valois - daughter of John II and Bonne of Luxembourg (Queen consort of Navarre)

Marie of France - daughter of John II and Bonne of Luxembourg (Duchess of Bar)

Isabella of France - daughter of John II and Bonne of Luxembourg (Countess of Vertus)

Catherine of France - daughter of Charles V and Joanna of Bourbon (Countess of Montpensier)

Isabella of Valois - daughter of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria (Queen consort of England, Duchess of Orléans)

Joan of Valois - daughter of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria (Duchess of Brittany)

Marie of Valois - daughter of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria

Michelle of Valois - daughter of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria (Duchess of Burgundy)

Catherine of Valois - daughter of Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria (Queen consort of England)

Radegonde of Valois - daughter of Charles VII and Marie of Anjou

Yolande of Valois - daughter of Charles VII and Marie of Anjou (Duchess of Savoy)

Magdalena of Valois - daughter of Charles VII and Marie of Anjou (Princess of Viana)

Joan of France - daughter of Charles VII and Marie of Anjou (Duchess of Bourbon)

Catherine of France - daughter of Charles VII and Marie of Anjou (Countess of Charolais)

Anne of France - daughter of Louis XI and Charlotte of Savoy (Duchess of Bourbon)

Joan of France - daughter of Louis XI and Charlotte of Savoy (Queen consort of France)

Claude of France - daughter of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany (Queen consort of France, Duchess of Brittany)

Renée of France - daughter of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany (Duchess of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio)

Madeleine of Valois - daughter of Francis I and Claude of France (Queen consort of Scotland)

Margaret of Valois - daughter of Francis I and Claude of France (Duchess of Berry, Duchess of Savoy)

Elisabeth of Valois - daughter of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici (Queen consort of Spain)

Claude of Valois - daughter of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici (Duchess of Lorraine)

Margaret of Valois - daughter of Henry II and Catherine de' Medici (Queen consort of France, Queen consort of Navarre)

Marie Elisabeth of France - daughter of Charles IX and Elisabeth of Austria

Elisabeth of France - daughter of Henry IV and Marie de' Medici (Queen consort of Spain, Queen consort of Portugal)

Christine of France - daughter of Henry IV and Marie de' Medici (Duchess of Savoy)

Henrietta Maria - daughter of Henry IV and Marie de' Medici (Queen consort of England)

Marie Thérèse - daughter of Louis XIV and Maria Theresa of Spain (Madame Royale)

Louise Élisabeth of France - daughter of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska (Duchess of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla)

Henriette of France - daughter of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska

Marie Louise of France - daughter of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska

Marie Adélaïde de France - daughter of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska (Duchess of Louvois)

Victoire of France - daughter of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska

Sophie of France - daughter of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska (Duchess of Louvois)

Thérèse of France - daughter of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska

Louise of France - daughter of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska (Saint)

Marie-Thérèse - daughter of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette (Queen consort of France)

Sophie of France - daughter of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

Sophie d'Artois - daughter of Charles X and Maria Theresa of Savoy

Louise of Orléans - daughter of Louis Philippe I and Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily (Queen consort of the Belgians)

Marie of Orléans - daughter of Louis Philippe I and Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily (Duchess of Württemberg)

Clémentine of Orléans - daughter of Louis Philippe I and Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily (Princess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duchess of Saxony)

#french history#catherine of valois#claude of france#henrietta maria#elisabeth of valois#historical women

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Women of the Crusader States || The Reigns of Baudouin II and Mélisende + Foulques

Morphia of Melitene (unknown – c. 1126/7) Daughter of Khoril of Melitene. Wife of Baudouin II de Jérusalem. Mother of Mélisende, Alix, Hodierne, and Yvette de Jérusalem.

Mélisende de Jérusalem (1105 – 11 September 1161) Daughter of Baudouin II de Jérusalem and Morphia of Melitene. Wife of Foulques V, comte d’Anjou. Mother of Baudouin III and Amaury de Jérusalem. Grandmother of Baudouin IV, Sibylle, and Isabelle Ire de Jérusalem.

Alix de Jérusalem (c. 1110 – after 1136) Daughter of Baudouin II de Jérusalem and Morphia of Melitene. Wife of Bohémond II, prince d’Antioche. Mother of Constance, princesse d’Antioche. Grandmother of Bohémond III, prince d’Antioche; Marie d’Antioche, Byzantine Empress; Philippa d’Antioche, dame de Toron; Baudouin d’Antioche; and Agnès d’Antioche, magyar királyné.

Hodierne de Jérusalem (c. 1110 – c. 1164) Daughter of Baudouin II de Jérusalem and Morphia of Melitene. Wife of Raymond II, comte de Tripoli. Mother of Raymond III, comte de Tripoli and Mélisende de Tripoli.

Yvette de Jérusalem (c. 1118 – 1178) Daughter of Baudouin II de Jérusalem and Morphia of Melitene. Abbess of Bethany.

Beatrice Rubinyan (1075 – c. 1130) Daughter of Kostandin I, Lord of Armenian Cilicia and an unnamed great-granddaughter of Bardas Phokas. Wife of Josselin Ier de Courtenay, comte d’Édesse. Mother of Josselin II de Courtenay, comte d’Édesse. Grandmother of Agnès de Courtenay, Josselin III de Courtenay, and Isabelle de Courtenay.

Cécile de France (1097 – 1145) Daughter of Philippe Ier de France and Bertrade de Montfort. Wife of Tancrède de Hauteville, prince de Galilée and Pons de Saint-Gilles, comte de Tripoli. Mother of Raymond II, comte de Tripoli. Grandmother of Raymond III, comte de Tripoli and Mélisende de Tripoli.

Helvis de Rama (c. 1110 – aft. 1152) Daughter of Baudouin Ier, seigneur de Rama and Stéphanie, dame de Naplouse. Wife of Barisan d’Ibelin, seigneur de Rama. Mother of Hugues d’Ibelin, seigneur de Rama; Baudouin d’Ibelin; seigneur de Rama; Balian d’Ibelin, seigneur de Naplouse; and Ermengarde d’Ibelin.

#historyedit#crusader states#crusades#french history#asian history#european history#medieval#history#women of the crusader states#nanshe's graphics

77 notes

·

View notes