#plantations

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

An international study led by the University of Freiburg, published in Global Change Biology, has found that forests with many tree species can store significantly more carbon than those with only one species. Researchers used data from the world's oldest tropical tree diversity experiment and found that forests planted with five tree species had substantially higher aboveground carbon stocks and greater fluxes between the carbon stores than monocultures. The results highlight the benefits of mixed-species forests for forest restoration initiatives that aim at mitigating climate change through carbon sequestration.

[...]

Remarkably, the positive tree diversity effect on aboveground carbon stocks strengthened over time, despite repeated climatic extreme events such as a severe El Niño-driven drought and a hurricane that hit the experiment. "This is important, because in the face of climate change, the long-term carbon balance of forests will depend largely on their stability to disturbances. Diverse forests exhibit greater ecological stability and the risk that the stored carbon is released back to the atmosphere is lower than in monocultures," said Dr. Florian Schnabel, first author of the study, forest scientist at the University of Freiburg's Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources, and head of the Sardinilla experiment.

25 February 2025

344 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite its green image, Ireland has surprisingly little forest. [...] [M]ore than 80% of the island of Ireland was [once] covered in trees. [...] [O]f that 11% of the Republic of Ireland that is [now] forested, the vast majority (9% of the country) is planted with [non-native] spruces like the Sitka spruce [in commercial plantations], a fast growing conifer originally from Alaska which can be harvested after just 15 years. Just 2% of Ireland is covered with native broadleaf trees.

Text by: Martha O’Hagan Luff. “Ireland has lost almost all of its native forests - here’s how to bring them back.” The Conversation. 24 February 2023. [Emphasis added.]

---

[I]ndustrial [...] oil palm plantations [...] have proliferated in tropical regions in many parts of the world, often built at the expense of mangrove and humid forest lands, with the aim to transform them from 'worthless swamp' to agro-industrial complexes [...]. Another clear case [...] comes from the southernmost area in the Colombian Pacific [...]. Here, since the early 1980s, the forest has been destroyed and communities displaced to give way to oil palm plantations. Inexistent in the 1970s, by the mid-1990s they had expanded to over 30,000 hectares. The monotony of the plantation - row after row of palm as far as you can see, a green desert of sorts - replaced the diverse, heterogenous and entangled world of forest and communities.

Text by: Arturo Escobar. "Thinking-Feeling with the Earth: Territorial Struggles and the Ontological Dimension of the Epistemologies of the South." Revista de Antropologia Iberoamericana Volume 11 Issue 1. 2016. [Emphasis added.]

---

But efforts to increase global tree cover to limit climate change have skewed towards erecting plantations of fast-growing trees [...] [because] planting trees can demonstrate results a lot quicker than natural forest restoration. [...] [But] ill-advised tree planting can unleash invasive species [...]. [In India] [t]o maximize how much timber these forests yielded, British foresters planted pines from Europe and North America in extensive plantations in the Himalayan region [...] and introduced acacia trees from Australia [...]. One of these species, wattle (Acacia mearnsii) [...] was planted in [...] the Western Ghats. This area is what scientists all a biodiversity hotspot – a globally rare ecosystem replete with species. Wattle has since become invasive and taken over much of the region’s mountainous grasslands. Similarly, pine has spread over much of the Himalayas and displaced native oak trees while teak has replaced sal, a native hardwood, in central India. Both oak and sal are valued for [...] fertiliser, medicine and oil. Their loss [...] impoverished many [local and Indigenous people]. [...]

India’s national forest policy [...] aims for trees on 33% of the country’s area. Schemes under this policy include plantations consisting of a single species such as eucalyptus or bamboo which grow fast and can increase tree cover quickly, demonstrating success according to this dubious measure. Sometimes these trees are planted in grasslands and other ecosystems where tree cover is naturally low. [...] The success of forest restoration efforts cannot be measured by tree cover alone. The Indian government’s definition of “forest” still encompasses plantations of a single tree species, orchards and even bamboo, which actually belongs to the grass family. This means that biennial forest surveys cannot quantify how much natural forest has been restored, or convey the consequences of displacing native trees with competitive plantation species or identify if these exotic trees have invaded natural grasslands which have then been falsely recorded as restored forests. [...] Planting trees does not necessarily mean a forest is being restored. And reviving ecosystems in which trees are scarce is important too.

Text by: Dhanapal Govindarajulu. "India was a tree planting laboratory for 200 years - here are the results." The Conversation. 10 August 2023. [Emphasis added.]

---

Nations and companies are competing to appropriate the last piece of available “untapped” forest that can provide the most amount of “environmental services.” [...] When British Empire forestry was first established as a disciplinary practice in India, [...] it proscribed private interests and initiated a new system of forest management based on a logic of utilitarian [extraction] [...]. Rather than the actual survival of plants or animals, the goal of this forestry was focused on preventing the exhaustion of resource extraction. [...]

Text by: Daniel Fernandez and Alon Schwabe. "The Offsetted." e-flux Architecture (Positions). November 2013. [Emphasis added.]

---

At first glance, the statistics tell a hopeful story: Chile’s forests are expanding. […] On the ground, however, a different scene plays out: monocultures have replaced diverse natural forests [...]. At the crux of these [...] narratives is the definition of a single word: “forest.” [...] Pinochet’s wave of [...] [laws] included Forest Ordinance 701, passed in 1974, which subsidized the expansion of tree plantations [...] and gave the National Forestry Corporation control of Mapuche lands. This law set in motion an enormous expansion in fiber-farms, which are vast expanses of monoculture plantations Pinus radiata and Eucalyptus species grown for paper manufacturing and timber. [T]hese new plantations replaced native forests […]. According to a recent study in Landscape and Urban Planning, timber plantations expanded by a factor of ten from 1975 to 2007, and now occupy 43 percent of the South-central Chilean landscape. [...] While the confusion surrounding the definition of “forest” may appear to be an issue of semantics, Dr. Francis Putz [...] warns otherwise in a recent review published in Biotropica. […] Monoculture plantations are optimized for a single product, whereas native forests offer [...] water regulation, hosting biodiversity, and building soil fertility. [...][A]ccording to Putz, the distinction between plantations and native forests needs to be made clear. “[...] [A]nd the point that plantations are NOT forests needs to be made repeatedly [...]."

Text by: Julian Moll-Rocek. “When forests aren’t really forests: the high cost of Chile’s tree plantations.” Mongabay. 18 August 2014. [Emphasis added.]

#abolition#ecology#imperial#colonial#landscape#haunted#indigenous#multispecies#interspecies#temporality#carceral geography#plantations#ecologies#tidalectics#intimacies of four continents#archipelagic thinking#caribbean

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

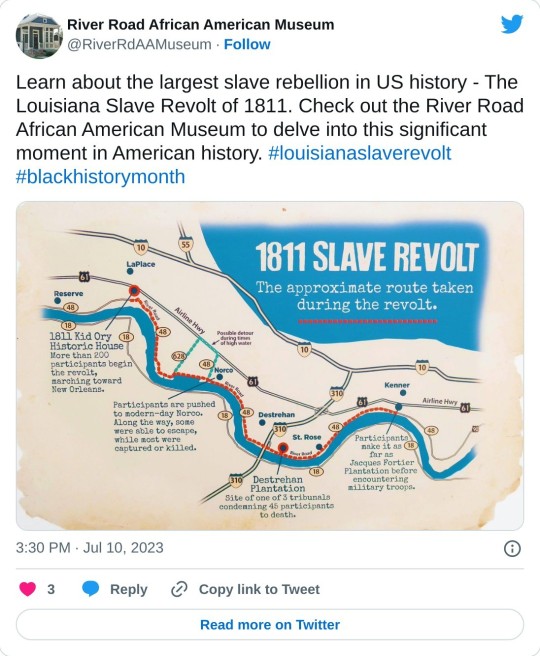

My family has a museum on River Road in Gonzalez Louisiana. the history will make you run through the fields running and crying. the bloody river road will never leave my memory..

#River Road African American Museum#River Road#Gonzalez Louisiana#louisiana#plantations#murder of Enslaved#Black History Matters#Black Lives Matter#Charles DesLonde#Kathy Hambrick#Hambrick Mortuary

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magic Wand. India,2024.

#india#coorg#karnataka#travel#plantations#coffee#bottle brush#brush#flowers#trees#nature#plants#pink#magic#fairy#wand#backpacking#photograhy#landscape#magical

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Amistad, 1839 by unknown

This 1839 oil painting of La Amistad shows the ship off Long Island, New York, next to the USS Washington. The Portuguese were the first and the last to partake in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The Spanish were also major transatlantic slavers and committed a genocide of the Native Cuban peoples when they colonized Cuba. The Spanish empire enslaved people of African origin and they often depended on others to obtain enslaved Africans and transport them across the Atlantic. Spanish colonies were major recipients of enslaved Africans, with around 22% of the Africans delivered to American shores ending up in the Spanish Empire. The story of the Amistad began in February 1839, when Portuguese slave hunters abducted hundreds of Africans from Mendeland, in present-day Sierra Leone, and transported them to Cuba, then a Spanish colony. Though the United States, Britain, Spain and other European powers had abolished the importation of enslaved peoples by that time, the transatlantic slave trade continued illegally, and Havana was an important trading hub. The Spanish plantation owners Pedro Montes and Jose Ruiz purchased 53 of the African captives as enslaved workers, including 49 adult males and four children, three of them girls. On June 28, Montes and Ruiz and the 53 Africans set sail from Havana on the Amistad (Spanish for “friendship”) for Puerto Principe (now Camagüey), where the two Spaniards owned plantations. Several days into the journey, one of the Africans—Sengbe Pieh, also known as Joseph Cinque—managed to unshackle himself and his fellow captives. Armed with knives, they seized control of the Amistad, killing its Spanish captain and the ship’s cook, who had taunted the captives by telling them they would be killed and eaten when they got to the plantation. In need of navigation, the Africans ordered Montes and Ruiz to turn the ship eastward, back to Africa. But the Spaniards secretly changed course at night, and instead the Amistad sailed through the Caribbean and up the eastern coast of the United States. On August 26, the U.S. brig Washington found the ship while it was anchored off the tip of Long Island to get provisions. The naval officers seized the Amistad and put the Africans back in chains, escorting them to Connecticut.

#portuguese slave trade#spanish slave trade#la amistad#slavery#portuguese#spanish#seascape#boat#ship#uss washington#cuba#habana#havana#history#historical#colonies#colonization#colonialism#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#fine arts#oil painting#europa#american history#plantation#plantations

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opium plantations in the Đồng Văn district of Vietnam

French vintage postcard

#postal#plantations#historic#vietnam#french#ansichtskarte#sepia#vintage#tarjeta#opium#briefkaart#photo#district#postkaart#ephemera#postcard#đồng văn#postkarte#photography#carte postale

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illustration detail from Shell Petroleum Corporation’s New Orleans and Vicinity Road Map - 1932.

#Illustration detail from Shell Petroleum Corporation’s New Orleans and Vicinity Road Map - 1932.#old new orleans#new orleans#shell oil#road maps#vintage road maps#highway maps#vintage highway maps#shell petroleum corporation#shell petroleum#gas stations#gas station road maps#vintage illustration#vintage advertising#maps#vintage maps#plantations#plantation homes#antebellum homes

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Made to labor for nearly double the hours of British yeoman farmers, African slaves would have an average working life of just seven years on the plantations of Brazil and the Caribbean. In the 1630s, a Jesuit plantation manager in Bahia, Brazil, wrote that the high mortality among slaves required an annual 6 percent replacement rate. A Barbados planter reported the same rate of slave losses, saying that “he that hath but a hundred Negroes should buy half a dozen every year to keep up his flock.” As long as the transatlantic human traffic could feed this voracious appetite for fresh slaves, plantations proved sustainable and highly profitable. Indeed, an econometric analysis of US agriculture in the early nineteenth century found the Southern slave plantation was 35 percent more efficient than a northern family farm. By literally working massed teams of slaves to death, the tropical sugar plantation maximized the energy output of the human body, creating a cruel economic logic that would drive the relentless expansion of the slave trade for the next four hundred years.

Alfred W. McCoy, To Govern the Globe: World Orders and Catastrophic Change

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

[T]he political philosophy underlying Westphalian, modern sovereignty [...], foundations of the modern state, [...] [was at least partially formed] in relation to plantations. [...] [P]lantations [are] [...] laboratories to bring together environmental and labor dimensions [...], through racialized and coerced labor. [...] [T]he planters and managers who engineered the ordering and disciplining of these [...] [ecological] worlds also sustained [...] [p]lantations [by] [...] disciplining (and policing the boundaries of) humans and “nature” [...]. The durability and extensibility of plantations, as the central locus of antiblack violence and death, have been tracked most especially in the contemporary United States’ prison archipelago and segregated urban areas [...], [including] “skewed life chances, limited access to health [...], premature death, incarceration [...]”. [...]

Relations of dependence between planters and their laborers, sustained by a moral tie that indefinitely indebts the laborers to their master, are the main mechanisms reproducing the plantation system long after the abolition of slavery, and even after the cessation of monocrop cultivation.

The estate hierarchy survives in post-plantation subjectivities, being a major blueprint of socialization into work for generations and up to the present. [...] [Contemporary labor still involves] the policing of [...] activities, mobility and access to citizenship [...].

---

[There is] persistence - until the 1970s in most Caribbean and Indian-Ocean plantation societies, and even until today in Indian tea plantations [...] - of a system of remuneration based on subsistence wages [...]. Plantations have been viewed as displaying sovereign-like features of control and violence monopoly over land and subjects, through force as much as ideology [...]. [W]itness the plethora of references to “plantocracies” [...] ([...] sometimes re-christened “saccharocracies” in the Cuban and wider Caribbean context [...] [or] “sovereign sugar” in Hawai’i). [...]

[T]race the genealogy of contemporary sovereign institutions of terror, discipline and segregation starting from early modern plantation systems - just as genealogies of labor management and the broader organization of production [...] have been traced [...] linking different features of plantations to later economic enterprises, such as factories [...] or diamond mines [...] [,] chartered companies, free ports, dependencies, trusteeships - understood as "quasi-sovereign" forms [...].

---

[I]n fact, the relationships and arrangements obtaining in the space of the plantation may be analogous to, mirrors or pre-figurations of, or substitutes for the power and grip of the modern state as the locus of legitimate sovereignty. [...] [T]he paternalistic and violent relations obtaining in the heyday of different plantations (in the United States and Brazil [...]) appear as the building block and the mirror of national-imperial sovereignties. [...]

[I]n the eighteenth-century [United States] context [...], the founding fathers of the nascent liberal democracy were at the same time prominent planters [...]. Planters’ preoccupations with their reputation, as a mirror of their overseers’ alleged skills and moral virtue, can thus be read as a metonymy or index of their alleged qualities as state leaders. Across public and private management, paternalism in this context appears as a core feature of statehood [...]. Similarly, [...] in the nineteenth century plantations were the foundation of the newly independent Brazilian empire. [...] [I]n the case of Hawai’i [...], the mid-nineteenth-century institution of fee-title property and contract labor, facilitated by the concomitant establishment of common-law courts (later administered by the planter elite), paved the way to the establishment of sugar plantations on the archipelago [...].

---

[T]he control of movement, foundational to modern sovereign claims, has in the plantation one of its original experimental grounds: [...] the demand for plantation labor in the wake of slavery abolition in the British colonies (1834) occasion[ed] the birth of the indenture system as the origin of sovereign control on mobility, pointing to the colonial genealogy of the modern state [...].

The regulation of slaves’ mobility also represented a laboratory for the generalization of [refugee, immigrant, labor] migration regulation in subsequent epochs [up to and including today] [...] [subjugating] generally racialized and criminalized subjects [...]. [P]lantations appear as a sovereign-making machine, a workshop in (or against) which tools of both domination and resistance are forged [...].

---

All text above by: Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. "Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times". Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives (edited by Petitcrops, Macedo, and Peano). Published 2023. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for criticism, teaching, commentary purposes.]

#abolition#ecology#multispecies#landscape#imperial#indigenous#colonial#tidalectics#archipelagic thinking#plantations#ecologies#carceral geography#caribbean#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies#debt and debt colonies

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

#charles deslonde#1811 slave revolt#louisiana#german coast#white slave owners#plantations#enslaved who fought back

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vortex. India, 2024.

#india#coorg#karnataka#plantations#nature#forest#flowers#organic#landscape#backpacking#purple#white#vortex#cosmic

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le vieux banc

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tobacco plantations in Indonesia

Dutch vintage postcard

#dutch#indonesia#sepia#plantations#photography#vintage#postkaart#ansichtskarte#tobacco#ephemera#carte postale#postcard#postal#briefkaart#photo#tarjeta#historic#postkarte

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Memories of Chapel Hill

April 1, 2025 Chapel Hill. The University of North Carolina. Ah! All the memories came rushing back as we drove around, parked the car, and walked along Franklin Street in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. I recalled meeting the Dean of City Planning, who welcomed me upon my arrival. He greeted me warmly and instilled confidence in me that I could not fail here. After I met my future wife, we…

View On WordPress

#Chapel Hill#city planning#Communism#genealogy#Iron Curtain#Johnny Cash#love#marriage#north carolina#Pioneers#plantations#religion#slavery#travel

0 notes