#pashtu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Top 10 Values of Pakhtun/Pashtun

Pakhtun Jarga ✅ Pakhtun is another spelling of “Pashtun,” which is an ethnic group primarily living in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Pashtun people have a rich cultural heritage and values, and there are many real values that are considered important in Pashtun society. Here are ten of them: 1 🎯 Honor (Nang):Pashtuns place a high value on personal and family honor. They believe that one’s…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Patrol. Afghanistan 1953

Kabul, 1953. Long before the many wars. My father Cyril was Air France General Manager in Pakistan. Karachi was the road to the Far East. Paris sent him to Kabul to investigate the possibility of opening a line to Afghanistan. My parents had lived in Pakistan for 6 years already. They spoke Urdu fluently. He knew the region. He took my mother’s 8mm camera. Shot a film which my mother edited, and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

What languages do you speak?

Swedish, English, Pashtu and some Urdu

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

An AU where Fabius is a Hollywood plastic surgeon.

Where this sudden change of heart came from and why - it's better not to ask when luck favours you so much. An interview with Hollywood's most sought-after, exclusive and undoubtedly most reclusive facesculptor! Well, at least initially with his spokesperson? Assistant? No explanation was given and there is nothing on the tasteful, very blank business card. Not even an email address. Or a telephone number. Anyone who has to ask for it hasn't understood how things work around here.

So now this lobby in a building far enough removed from the city to have an undisturbed hill overlooking the Pacific to itself (presumably at the price of the gross national product of a Central American country). A strangely brutalist-beautiful house that looks like a James Bond villain gave Aldo Rossi free rein.

Dr Bile has never before answered an interview request, let alone positively: why now, of all times, and from a magazine that is not exactly Lancet - it is inexplicable!

It is not particularly inviting yet. Two women who could not be more different and yet look equally unreal without flaunting the artificiality of too much plastic surgery stand with the noncommittal vigilance of born bodyguards at the doorway to the deeper interior of the building. One is downright bizarrely tall, her platinum blonde hair in an expensive cut that shows off her facial features, which are not one hundred percent even in just the right way, to their best advantage. She radiates a deadly elegance that makes it clear that even though she wears strangely blocky high heels that almost turn her feet into hooves (they must be shoes!), in a critical situation she would strike with the ruthlessness of a pouncing snake. Like her colleague, she wears a tailored dark suit in the price range called for by the tailors of the Vatican. No logo on the clothes. Of course there isn't. The winged double helix is only present as an isolated pattern in the dark carpet and on the wall. The other woman is clearly smaller, but more compact. Her muscular composure is punctuated by a couple of almost ceremonial-looking, tremendously precise scars that do not disfigure her face but rather indicate her businesslike nature. Something that her pixie cut and broad, sinewy hands emphasise.

"Ah, good afternoon! Welcome to the Consortium!" Perfectly articulated, flawless. Yet a very slight echo of the rounded consonants of Farsi or Pashtu.

The man stepping out of the doorway is not the doctor. Of course he isn't. But our journalist has done his homework. So this is him. His .. Press officer? Assistant? Marketing manager? It was impossible to figure out. But he is what stands between Dr Bile and the world.

His smile is practised and smooth, his olive-dark features regular. As he reaches out, the sleeve of the Desmond Merrion suit slides up just the right distance to expose the beginnings of the fine lines of a calligraphic tattoo. As if he actually deals with visitors every day, he ushers him to the passageway between the two women. A corridor with old copperplate engravings showing the most prominent buildings of various medical faculties. Tastefully dimmed spotlights create a withdrawn atmosphere. Further back, a few more doors can be seen and at the very end, a double door upholstered in leather. "My name is Saqqara Ur-Damak Thresh and today I am here to answer all your questions."

Of course, this is a lie. But perhaps it is possible to draw enough substance from his answers to get closer to the Doctor's mystery.

His office. Not the doctor's study, of course. And "office" is only a very marginal term. There is an empty desk and a very utilitarian seating area. And bookshelves on the walls. On all the walls. Filled with volumes of all sizes and ages, obviously not just placed for decorative purposes.

Not what you would expect. But actually, you can expect nothing and everything here.

The only wall not filled with literature is a floor-to-ceiling window that looks out over the conifer-forested hills and driveway. Just before Mr Thresh makes an inviting hand gesture towards the couch, a black Maybach with tinted windows pulls up. Stops in front of the entrance. On the door a gold logo. An eye in a circle of arrows. Ah, of course the clientele here is also special.

On the low table between the two couches is a silver tea set. Mr Thresh pours, quite the good host. Everything here is at once completely ceremonial and absolutely authentic.

"I hope your journey was pleasant. Of course, as always, time is short. But rest assured - for the next hour, my attention is entirely yours!"

-------------------

Okay. So. I am absolutely obsessed with the premises of this AU! I haven't barely scratched the surface (I mean, Saqqara, Savona, Igori and a hint of Abaddon is nothing!) and it's already an entire page of text.

So - if anybody is interested, I will write more about this AU. There are a lot of people who have to make an appearance - especially of course the Doctor himself!

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to Aurora Bay, [ELIJAH VARGAS]! I couldn’t help but notice you look an awful lot like [OSCAR ISAAC]. You must be the [FORTY] year old [RETIRED SPECIAL FORCES]. Word is you’re [COURAGEOUS] but can also be a bit [STUBBORN] and your favorite song is [KNOCKIN' ON HEAVEN'S DOOR BY BOB DYLAN]. I also heard you’ll be staying in [SEABROOK QUARTER]. I’m sure you’ll love it!

LINKS

stats

wanted connections

playlist

ABOUT ELI

astrology:

Aries ☀, Cancer ☾, Pisces ↟

traits:

closed off, courageous, fiery, stubborn, charming, practical, sarcastic, rational, private, risky, daring, leader, easily annoyed, persuasive, thoughtful, protective, loyal, insightful, fighter, observant

aesthetic:

seashells, sleepless nights, sunset walks, camouflage, passport stamps, messy kitchen, guitar strings, unofficial chef, the weight of war, champagne problems, swords, eagle eye

BIOGRAPHY

[ tw: death, gun violence, ptsd, war, alcoholism ]

Eli was born in Aurora Bay and lived there until he was thirteen with his single mother and older brother Hector.

His mother passed away suddenly due to an aneurysm. Eli and Hector were forced to live with their family out in New York. They were under their uncle’s care.

His family in New York was a bit problematic, running with the wrong crowds, often getting into trouble with the law. Eli didn’t approve in the beginning and his uncle often teased that he was self righteous or like a little soldier - always following orders.

Hector was quick to join their cousins and friends, often getting into trouble for stealing or vandalism. When breaking into a home to pawn off some items, Hector was gunned down by the owner and killed. After losing his brother, the only piece of true family he still felt he had, Eli became determined to leave that family behind and leave New York behind him.

Eli joined the Army as a means of escape. He went up in the ranks and joined the special forces. He spent a good part of his life moving around, serving tours in foreign countries, and often in combat.

While stationed back in New York for some time, he was not enthused to go back to a place that now felt haunted. He was eagerly finding ways to get deployed or stationed elsewhere, up until he met someone. Mei Lian Huang.

The two fell in love and for the first time in his life he had felt seen. New York no longer felt like hell, because she was the closest to Heaven he had ever been. Their relationship came with a complication - she was married. Eli knew it was wrong to pursue her, but for the first time in a long time, he was willing to break the rules.

After some time into the affair, the Army wanted him to relocate to Germany. He thought it was a perfect chance for them to finally escape and start something new together. When he invited her to join him, he was surprised that she declined. His heart broke that day in a way he was never sure would repair. Almost as if it broke one too many times. He had no choice but to leave her behind.

Eli spent the last five years finishing out his career in the special forces. He retired at the age of 40 with 22 years of service under his belt and the PTSD that keeps him up at night. For once in his life, he decided to do something for himself that didn’t involve following orders or fighting. He moved to the only place that ever felt like home - Aurora Bay.

Now back in Aurora Bay, he’s searching for the meaning of home and hoping he finds it when he takes those strolls at dusk along the beach, remembering the days of walking beside his mother and brother.

EXTRA INFO

While in the military, Eli was given the nickname "Eagle Eye Eli" due to his outstanding capabilities with sniping. The nickname was shortened to "Triple E" and later to simply "Trip". All of his military friends call him Trip to this day.

Eli can speak a handful of different languages, though he's not fluent in all of them. He knows a bit of Arabic, Pashtu, Dari, and German. He is also fluent in Spanish.

He has hopes of opening his own restaurant or bakery one day in honor of his late mother. Eli has always been a talented chef.

He enjoys playing the guitar and singing. If you give him enough to drink, he may even do an open mic night.

He has had a problem with alcohol for the past couple of years. It's difficult for him to sleep and so he often turns to a bottle to help. Eli is attempting every day to cut back on his alcohol consumption, and some days he fails miserably.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some people call kurds Persians assyrians chladeans pashtu etc all arabs and my fellow western people it's time we had the talk

Arabs are native Arabic speakers and their descendents are arab or part arab

Nationality of an arab country doesn't make someone an arab, in Syria there are significant Kurd populations for example who live in the syrian Arab republic but are not arabs

Iran is not an arab country

A lot of people in the middle east have been different cultures at different times but assimilated into the arab speaking people during the arab expansions during the first 3 khalifates, an example is the Maronites of Lebanon, they were once near entirely Aramaic speaking but now are nearly entire arabic speaking and are considered arab

My dad is ¼ maronite lebanese my great grandma spoke arabic fluently as a first language, and passed it on to a few of her kids, not my grandpa though; my dad says he's not part arab he's part west Asian... which... sure pal whatever

Lebanese is a nationality not an ethnicity, west Asian is a geographic region not an ethnicity and what an Arab is has nothing to do with nationality and no arab country is homogeneous, or any country for that matter.

Also arab does not equal Muslim, arabs are religiously diverse so write this down

0 notes

Text

Online Pashtu to English Translation Services - Quickly and Accurately Translate Pashto Conversations

Pashtu to English: Unlocking Opportunities for Immigrant Families For the nearly 40 million Pashto speakers around the world, communicating across languages can often get lost in translation. As more Afghan and Pakistani immigrants settle in America, bridging the cultural and linguistic divides through accurate Pashto to English translation becomes increasingly vital. This comprehensive guide…

View On WordPress

#afghan immigrants#dari translation#english learners#pakhto#pakistani immigrants#pashto#pashto to english#pashto translation#pushto

0 notes

Note

Well, I don't think she is fluent in 9 language either, but Nadia must be fluent in danish, english pashtu/dari and german, (I heard a german interview with her and she was nearly fluent) which is crazy.

I've heard the german interview too, she really is so good! I think a lot of danish people learn german in school, right? she's crazy smart for sure!!

1 note

·

View note

Text

زما په گل په شان صورت وه ستا دبیلتون په خزان مراوی شوی مینه

I had a beautiful face like a flower but your separation turned me into autumn.

Pashto Landay via honeyandelixir

#Pashtolanday#Pashto#Pashton#Pathan#Pashtu#Pashtopoetry#pashtopoetry#Poetry#Poems#poems on tumblr#urdu poems#friendship poems#love poems#poemsdaily#inspirational poems#poemsaboutlove#spilled poems#sad poems

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

کۀ غواړئ چې ووینۍ یو قام څومره مهذب دے، وګوره چې د خپلو ښځو سره څنګه تعامل کوي.

باچا خان بابا

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It was the night before christmas

It’s the evening before Eid here, so Eid Mubarak to my Muslim followers from your resident Pathaan obey me siblings (and me!). And to those of you who don’t celebrate Eid, I hope you still have a wonderful day! ❤

And yes Noor is wearing my Eid outfit and yes I did put Yusuf in something my brother has worn on Eid too lol

#ahhh noor looks like a princess#and look at yusuf!#catch him wearing his special occasion glasses lmao#I wanted to make something bigger#but i always get so busy around eid time I only just about managed to finish this#eid mubarak#!!!#Or as we say in pashtu#akhtar de umbarak sha#tumblr stop eating the quality#thanks#noor#nais doodles#yusuf#obey me mc

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!

Your inbox is open, so can you write a bit about Athanasia Al Ghul's younger years in League of Shadows? I remember your "Failure", but it was long, long ago. You can show some more of her trainings maybe or describe her room or her hobbies or anything you like, but about teen Sia? I'd be great!

Hello,

So I'm terribly sorry about this, but I can't really do that. Failure is set in HfaB, and I haven't fully explored Athanasia as a character, so I'm not super comfortable attempting to flesh her out at this moment. I can tell you the following about her though based off the one shot Failure:

-Athanasia is the Bruce/Talia tube baby storyline, she was grown in the tube with Lazarus Pit waters, and other fluids needed. No, Bruce and Talia are not aware of her existence; they both believe she was their miscarried child, and that miscarriage is what broke them up.

-She was raised as a slave in the LoA, she never had an opportunity to be an heir.

-She trained routinely with Grant Wilson and Jason Todd; she even later helped Jason escape.

-She and Jason are the exact same age, mere months separate them age wise; and I think Jason is still the older one, I'd have to double check my notes.

-Her favorite books are the Girl With the Dragon Tattoo Series by Steig Larsson; Athanasia relates to Lisbeth Salander very well, and this is the reason that Athanasia went on to live in Stokholm, Sweden.

-She's a hacker and computer genius, she prefers not to be physical or violent, though she can be. She's assumed the mantel TH3 GH0ST (yes this is a nod to the video games where Bruce held the mantel the Ghost)

-Athanasia was sixteen when she escaped the LoA.

-She is in contact with Jason and Tim (neither are aware she's Bruce's daughter, and Tim doesn't even know her real identity; not for a lack of trying but they have a pen pal relationship exchanging chess moves and intel)

-She's had sexual relations with men and women; and like Jason has a complicated relationship regard sex and her actual sexuality (which is still unknown or not dwelled on).

-She has met and had dealings with Talia; Talia and Athanasia have a very bad relationship as a whole.

-She celebrated Ra's al Ghul's death by going on a three month long bender, in which she does not remember most of, but has photos spanning her travelling the Hindukush to piss on Ra's grave.

-She prefers cats to dogs, but reptiles to cats (I know, my soul evac'ed my body too when I figured that out).

-She is not a fan of spicy foods, but a lover of French cuisine, and Italian cuisine; she despises English food passionately.

-She is a meta, punk rock, classic rock, hard rock, and rock n roll fan (frequenting concerts for her favorite bands), she despises country music, pop music, and techno music; though she does enjoy clubbing and club music

-Her favorite drink is white wine, or sherry, she's an avid vodka drink too.

-She speaks the following languages fluently: English, Arabic (specifically the Pashtu and Egyptian dialects), Chinese, Swedish, and Russian. She understands the following languages: Italian, French, German, and Spanish.

-She likes motorcycles; holding cars in great disdain.

-She is a loner with known antisocial personality disorder as well as severe PTSD.

-She carries a Baretta 92F, and a P-83 Wanad (because she loves Lisbeth Salander), but she's familiar and comfortable with a Glock 17 too.

I hope that helps form an idea for the Athanasia I'll be introducing in Damned Prince of Gotham.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

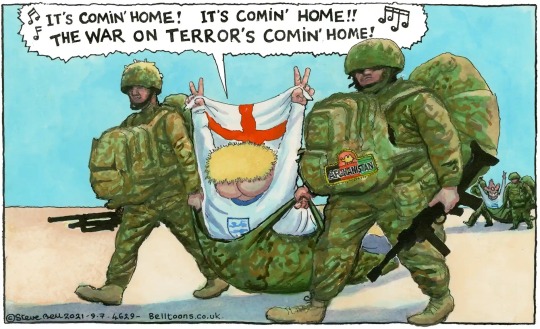

ltdan2288 asked: As a fellow veteran of the Afghan Campaign, might I ask if you have any thoughts about the imminent end of Allied air support & combat-advisory operations over there? The fall of large swaths of the country to the Taliban is already underway, which can only be seen as an unspeakable tragedy for the people there. From a strategic perspective, there’s no reason to believe that we won’t have to return in some capacity of AQ or ISIS reestablish themselves under Taliban sponsorship. At the same time, it’s not clear to me that our presence did anything beyond kick the can down the road and delay this inevitable outcome. As someone with such a deep knowledge of military history, I’m curious if you have a different perspective.

I have been avoiding answering this post for a while now because Afghanistan dredges up so many conflicting emotions inside me. I wrestle with so many memories of my time there with my regiment to fight in a war that we all didn’t really understand what we were fighting for.

Deep breath.

Almost two decades of conflict in Afghanistan has cost British taxpayers £22.2billion, or $31.3 billion according to UK government figures. As British troops prepare to leave Afghanistan, the 20-year deployment bill could be even higher. As of May 2021, the total cost of Operation Herrick (codename for the deployment of British soldiers to Helmand province) is £22.2billion. There were 457 fatalities on, or subsequently due to, Op Herrick. Of which 403 were due to hostile action. During the operation between January 1, 2006 and November 30, 2014, there were 10,382 British service personnel casualties. Of these 5,705 were injuries and the remainder being illness or disease. The UK’s remaining 750 troops in Afghanistan, involved in training local forces, started exiting the war-devastated country in May. Most of them will return home by the end of July.

They, like every one of us who went to fight in Afghanistan, will ask the same questions, ‘Why did we go there?’ ‘What was the real purpose of the mission?’ ‘Was it worth it?’

Both my older brothers fought there with special distinction and I later fought there too. I have very mixed emotions when I think about my time in Afghanistan. For all its faults and tortured history, I love that country and love its many ethnic people. I even started to learn Pashtu as I already had a spoken command of Urdu because I had been raised partly in both Pakistan and India and it’s where many Afghan refugees living in the UN camps for over a generation had learned Urdu too.

It’s not just that my family has history in Afghanistan going back to the days of the East India Company but I had a sincere respect for its culture and history as one of the central hot spots for great civilisational achievements, but also as a stubborn and unruly country who proudly defied the Great Powers to bend the knee and turned it into a ‘graveyard of empires’. Most of all I think of the friendships I made there and how my perspective on life changed as a consequence of knowing such resilience and fortitude in the face of catastrophe and death.

I’m sure like everyone else I wasn’t too surprised by President Biden’s announcement that he was announcing the imminent withdrawal of all American troops in Afghanistan. He wanted to pivot to something else when asked about it. “I want to talk about happy things, man!” He said. Who could begrudge him given that America has been at war in Afghanistan for a better part of 20 years and has nothing to really show for it. Except of course the loss of its brave service men and women as well as the death of thousands of Afghan civilians. It spent more than $2 trillion to kill Osama bin Laden, the architect behind 9/11 attacks and failed to convincingly snuff out both murderous terror groups, Al Qaeda and ISIS.

When the Secretary General of Nato announced back in April 2021 all alliance troops were to be withdrawn from Afghanistan, it was made to look like a nice, clean, enunciation of a joint decision. The end date was set for 11 September, 2021 - 20 years after the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington - and it was in line with the oft-repeated alliance maxim: we went in together; we will come out together. Except that, on closer examination, it was all rather messier.

This was partly because the withdrawal from Afghanistan had actually been Trump’s policy, so here was Joe Biden, the anti-Trump, co-opting a policy from his predecessor (a policy Trump had been so keen on that he tried to accelerate the withdrawal after he lost the election). Biden then tried to detach it from Trump by slowing down the withdrawal date a little and expressing it in terms more comprehensible to the Washington establishment and to US allies.

Where Trump had essentially done a deal with the Taliban and set a withdrawal date of 1 May, Biden left the Taliban out of it and invoked the totemic date of 9/11. This does not mean, of course, that the withdrawal will not be completed a good deal sooner - once you announce a withdrawal, you might as well get on with it.

In fact, Biden had to make a decision one way or another, given the rapid approach of Trump’s 1 May withdrawal date. And, whether it came from Washington or Nato, it was pretty low key for an announcement that a 20-year military involvement that had cost 4,000 allied lives was ending. Indeed, many people beyond Washington and Afghanistan might not quite have registered the news, given the considerable noises from Nato’s simultaneous dire warnings about Russia massing troops on the Ukrainian border, the death of the Duke of Edinburgh in the UK, and the Covid pandemic everywhere.

And distractions were needed not just because Biden was implementing a Trump policy. It was also because he was ordering an unconditional withdrawal – which he justified, correctly, by saying that setting preconditions would mean that the troops could be there forever. It was a risk Biden knew all too well, given that Barack Obama had been persuaded by General David Petraeus – against his election pledges and his better judgement – that what Obama really wanted was not a withdrawal, but a ‘surge’ with conditions attached before a withdrawal could take place.

Distractions were also useful for London, where the timing was hardly ideal. Imagine you were in government in London, you had watched the dismal failure of the UK’s Herrick operations in Helmand Province between 2006 and 2014, you knew that your armed forces had suffered 456 deaths in 20 years, with many more severely injured, but you had hung on in there.

Your government had also just released a blueprint for foreign and security policy, setting future priorities even further from home, in the Indo-Pacific, and your Prime Minister was about to make a high-profile visit to India as part of his post-Brexit ‘Global Britain’ branding . In those circumstances, an announcement that the US had decided to leave Afghanistan, giving you no choice but to follow, was almost exactly what you did not need. Rather than showing the UK as a powerful, autonomous military actor and a valued ally, it showed the exact opposite.

It also reminded an unhappy British public about a costly conflict it had rather forgotten. And those who did more than bother to remember - like the families who lost loved ones on the battlefield - and who over the years have blamed successive governments for moving the goalposts and lacking an exit strategy (all true too).

All of which might explain why the UK’s Foreign and Defence Secretaries followed the US example by changing the subject to the iniquities of Russia and China, rather than issuing a joyous pronouncement to the effect of: hooray and thank goodness, our boys and girls are coming home.

The UK’s Chief of Defence Staff, General Sir Nick Carter gave a subdued, unenthusiastic response to Biden’s announcement. I cannot remember such open acknowledgement of UK-US military policy friction in recent decades - or such an abject admission by the UK of its defence dependence on the US. What Carter said was that the unconditional withdrawal was ‘not a decision we had hoped for, but we obviously respect it and it is clearly an acknowledgement of an evolving US strategic posture’. In other words, the UK had opposed Biden’s decision – or would have done, if asked (which is not clear). Also, that it was Washington’s ‘strategic posture’ that had ‘evolved’, not the UK’s. He suggested there was a real danger that progress made could be lost and that there could be a return to civil war, with the Taliban maybe returning to power - again, all true.

Given that the UK officially has only 750 troops in Afghanistan at present, and most of them are there in a training capacity, to dissent from the US position so openly would be considered decidedly rude in the Ministry of Defence. Perhaps to that end, General Carter played the dutiful soldier and had to - through gritted teeth - put a positive gloss on Afghanistan’s future, insisting that the objective in going into Afghanistan, ‘to prevent international terrorism emerging from the country’, had been achieved which was ‘great tribute to the work of British forces and their allies’.

He also said that Afghan forces were ‘much better trained than one might imagine’ and that the Taliban ‘is not the organisation it once was’, so that ‘a scenario could play out that is actually not quite as bad as perhaps some of the naysayers are predicting.’ Blah blah blah. He’s wrong, and I think he knows it but only in the sanctity of his gentlemen’s club might he truly admit it.

I know he’s wrong because the chatter amongst ex-veterans I know is that we’ve made a balls up of Afghanistan yet again - by ‘again’ I mean from the past 200 years of us Brits trying to bring order to chaos in Afghanistan and getting burned for our troubles.

Both my father and my older siblings tell me what their friends and ex-service peers (some very senior indeed) have been nattering over a drink at their gentlemen clubs where ex-veterans haunt the club bar. Many just shake their heads in sighed resignation before burying themselves in the Times crossword or drowning their sorrows with a beer or two at how lock in step we’ve become to the Americans at a time when the British army is re-branding itself as a more independent nimble hi-tech impact army (the creation of a new ranger regiment being but one example).

Still if President Biden wanted to tie a neat bow on U.S. involvement in Afghanistan - saying, as he had, that the logic for the war ended once al-Qaida was gutted and Osama bin Laden killed - then it reveals a stunning lack of introspection about the United States’ role in the conflict that will continue in Afghanistan long after the last American and British troops leave.

Less than three months after President Joe Biden declared that the last American troops would be out of Afghanistan by September 11th, the withdrawal is nearly complete. The departure from Bagram air base, an hour’s drive north of the capital, Kabul, in effect marked the end of America’s 20-year war. But that does not mean the end of the war in Afghanistan. If anything, it is only going to get worse.

It is true that the president had no good choice on Afghanistan, and that he inherited a bad deal from his predecessor. There are never good choices when it comes to Afghanistan: only bloody trade offs.

But in announcing an unconditional withdrawal, he made the situation worse by throwing out the minimal conditions U.S. Special Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad had negotiated under the Trump administration. U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad has delivered to the Afghan government and Taliban a draft Afghanistan Peace Agreement - the central idea of which is replacing the elected Afghan government with a so-called transitional one that would include the Taliban and then negotiate among its members the future permanent system of government. Crucial blank spaces in the draft include the exact share of power for each of the warring sides and which side would control security institutions.

The refrain now from the Biden administration is that the United States is not abandoning Afghanistan, that it will aim to do right by Afghan women and girls, and that it will try to nudge the Taliban and Kabul toward a peace deal using a diplomatic tool kit.

But the narrative ignores much of the reality on the ground. It also ignores history.

In theory, the Taliban and the American-backed government had been negotiating a peace accord, whereby the insurgents lay down their arms and participate instead in a redesigned political system. In the best-case scenario, strong American support for the government, both financial and military (in the form of continuing air strikes on the Taliban), coupled with immense pressure on the insurgents’ friends, such as Pakistan, might succeed in producing some form of power-sharing agreement.

But even if that were to happen - and the chances are low - it would be a depressing spectacle. The Taliban would insist on moving backwards in the direction of the brutal theocracy they imposed during their previous stint in power, when they confined women to their homes, stopped girls from going to school and meted out harsh punishments for sins such as wearing the wrong clothes or listening to the wrong music.

More likely than any deal, however, is that the Taliban try to use their victories on the battlefield to topple the government by force. They have already overrun much of the countryside, with government units mostly restricted to cities and towns. Demoralised government troops are abandoning their posts. In the first week of July 2021, over 1,000 of them fled from the north-eastern province of Badakhshan to neighbouring Tajikistan. The Taliban have not yet managed to capture and hold any cities, and may lack the manpower to do so in lots of places at once. They may prefer to throttle the government slowly rather than attack it head on. But the momentum is clearly on their side.

America and its NATO allies have spent billions of dollars training and equipping Afghan security forces in the hope that they would one day be able to stand alone. Instead, they started buckling even before America left. Many districts are being taken not by force, but are simply handed over. Soldiers and policemen have surrendered in droves, leaving piles of American-purchased arms and ammunition and fleets of vehicles. Even as the last American troops were leaving Bagram over the weekend of July 3rd, more than 1,000 Afghan soldiers were busy fleeing across the border into neighbouring Tajikistan as they sought to escape a Taliban assault.

As the outlook for the army and for civilians looks increasingly desperate, so do the measures proposed by the government. Ashraf Ghani, the president, is trying to mobilise militias to shore up the flimsy army. He has turned for help to figures such as Atta Mohammad Noor, who rose to power as an anti-Soviet and anti-Taliban commander and is now a potentate and businessman in Balkh province. “No matter what, we will defend our cities and the dignity of our people,” said Mr Noor in his gilded reception hall in Mazar-i-Sharif, the key to holding the north (sounds like Game of Thrones). The thinking is that such a mobilisation would be a temporary measure to give the army breathing space and allow it to regroup and the new forces would co-ordinate with government troops to push back hard on the Taliban.

However this is Afghanistan. The prospect of unleashing warlords’ private armies fills many Afghans with dread, reminding them of the anarchy of the 1990s. Such militias, raised along ethnic lines, tended to turn on each other and the general population.

With America gone and Afghan forces melting away, the Taliban fancy their prospects. They show little sign of engaging in serious negotiations with Mr Ghani’s administration. Yet they control no major towns or cities. Sewing up the countryside puts pressure on the urban centres, but the Taliban may be in no hurry to force the issue. They generally lack heavy weapons. They may also lack the numbers to take a city against sustained resistance. On July 7th they failed to capture Qala-e-Naw, a small town. Besides, controlling a city would bring fresh headaches. They are not good at providing government services.

Perhaps the Taliban have learned their history lesson and might refrain from attacking Kabul this time around. Their best course may be to tighten the screws and wait for the government to buckle. American predictions of its fate are getting gloomier. Intelligence agencies think Mr Ghani’s government could collapse within six months, according to the Wall Street Journal. So clearly the momentum is on the side of the Taliban and they just need to chip away at Ghani’s forces one district after another until the inevitable and hateful surrender of the central Afghan government to their demands.

At the very least, the civil war is likely to intensify, as the Taliban press their advantage and the government fights for its life. Other countries - China, India, Iran, Russia and Pakistan - will seek to fill the vacuum left by America. Some will funnel money and weapons to friendly warlords. The result will be yet more bloodshed and destruction, in a country that has suffered constant warfare for more than 40 years. Those who worry about possible reprisals against the locals who worked as translators for the Americans are missing the big picture: America, Britain and other allies are abandoning an entire country of almost 40m people to a grisly fate.

Nothing exemplifies - at least in Afghan eyes - of all that has gone wrong with American involvement in Afghanistan than in the manner of their leaving.

The U.S. left Afghanistan's Bagram Airfield after nearly 20 years by shutting off the electricity and slipping away in the night without notifying the base's new Afghan commander, who discovered the Americans' departure more than two hours after they left in the middle of the night without raising any alarms.

They left behind 3.5 million items, including tens of thousands of bottles of water, energy drinks and military MRE's (Meals Ready to Eat ration packs to the uninitiated). Thousands of civilian vehicles were left, many without keys to start them, and hundreds of armoured vehicles. The Americans also left small weapons and ammunition, but the departing US troops took heavy weapons with them. Ammunition for weapons not left for the Afghan military was blown up.

Now that is some feat considering the logistics of this mass exodus without drawing any attention. You have obviously been to Bagram and so you will know just how big and sprawling it is. Bagram Airfield is the size of a small city, roadways weaving through barracks and past hangar-like buildings. There are two runways and more than 100 parking spots for fighter jets known as revetments. One of the two runways is 12,000 feet long and was built in 2006. There's a passenger lounge, a 50-bed hospital and giant hangar-size tents filled with furniture. And all those shops to remind Americans of home from familiar fast food restaurants and hairdressers and massage parlours to buying clothing and jewellery and buying a Harley Davidson motorbike (or so I’ve been told).

I’m guessing that the Afghans were certainly outside of the wire and probably had not been inside Bagram Airfield for months. So from the outset they would not have had any reason to think anything was going on until the generators probably ran out of fuel and it started to go a little too quiet. The inner gate was probably discretely left unlocked and when the US stopped answering the radio/phone and then they probably investigated.

Before the Afghan army could take control of the airfield about an hour's drive from the Afghan capital, Kabul, it was invaded by a small army of looters, who ransacked barrack after barrack and rummaged through giant storage tents before being evicted, according to Afghan troops. Afghan military leaders insist the Afghan National Security and Defense Force could hold on to the heavily fortified base despite a string of Taliban wins on the battlefield. The airfield includes a prison with about 5,000 prisoners, many of them allegedly Taliban members.

I’m pretty sure some bright spark in the US Pentagon public affairs dept convinced his military superiors that it was important to avoid the optics of Americans leaving in the same way they did in Vietnam in case it depresses the American public and the US military. Instead it demoralised its allies, the Afghan national army who are now the only line of defence against the Taliban. In one night, they lost all the goodwill of 20 years by leaving the way they did, in the night, without telling the Afghan soldiers who were outside patrolling the area. The manner in which the Americans left Bagram air base amounts to a resounding vote of no confidence in Afghanistan’s future. It just looks bad.

The U.S. choice came with costs attached to each decision. With staying, the cost was potential U.S. troop casualties and a fear that things would not change on the ground. With leaving comes the cost of a deeper conflict in Afghanistan and a backsliding of progress made there over the past two decades. In many ways, the costs of staying seem shorter-term and borne by the United States, while the costs of leaving will be predominantly borne by Afghans over a longer time horizon. Yet, even if those costs seem remote now, history tells us that they will be blamed on the United States.

Biden perhaps reflective of history of Americans getting into quagmires abroad didn’t want to be seen exerting time and energy for a losing cause. His decision also reflects his administration’s foreign policy for the American middle-class paradigm, which focuses on domestic considerations over international ones (and is this so different from Trump’s “America First”? No, it is not). The irony, though, is that the American middle class largely doesn’t care about Afghanistan - their ambivalence gave way to support for this decision once it was announced, but it wouldn’t be hard to visualise the public approving of a scenario that kept a couple thousand troops there for a while longer.

What’s perhaps most disturbing is the narrative the president has presented along with the rationale for withdrawal: that America went to Afghanistan to defeat al-Qaida after 9/11, that mission creep led America to stay on too long and, therefore, it is time to get out. This takes an incomplete view of U.S. agency in the war in Afghanistan. The narrative implies that the civil conflict in Afghanistan today did not originate with America - that this more than 40-year war began with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, preceded America’s interference in Afghanistan, and will follow our departure.

The fact of the matter is that, by beginning the campaign in Afghanistan in 2001 and overthrowing the Taliban, who were then engaged in their draconian rule, and installing a new government, we western allies began a new phase of the Afghan conflict — one that pitted the Kabul government and the United States/Britain/NATO against the Taliban insurgency. The Afghan people did not have a say in the matter. That we allied powers are leaving Afghan women, children, and youth better off in many ways after 20 years is due to us, and we should be proud of that. But that we are leaving them mired in a bloody conflict is also due to us, because we could not hold off the Taliban insurgency, and we must all reckon publicly with that.

I have to ask myself why did we fail?

I’m only speaking about us Brits now as I’m sure you have your own thoughts as an ex-Marine officer of what you thought of the American military effort. Yes, I’m copping out of really bashing the yanks because first, I have too much respect for those fantastic American service men and women I did have the privilege to fight alongside with; and second, we Brits have nothing to crow about as we fucked up in lots of ways too, and to make things worse, we should have known better given our imperial history with Afghanistan.

The seeds of our failure in Afghanistan lies in not learning from history. We didn’t have a mission that was properly defined nor did we have a strategy that was clear, coherent, and easily communicated to both its fighting men and women as well as to the British public.

Were we there to get our hands bloody and to root out and destroy extreme Islamist terrorists or were we there to indulge in state building out of some idealistic notions of liberal humanitarianism? This question was at heart of our failure within our government and also within the British army as well as our relations with America and our NATO allies and finally the Afghans themselves.

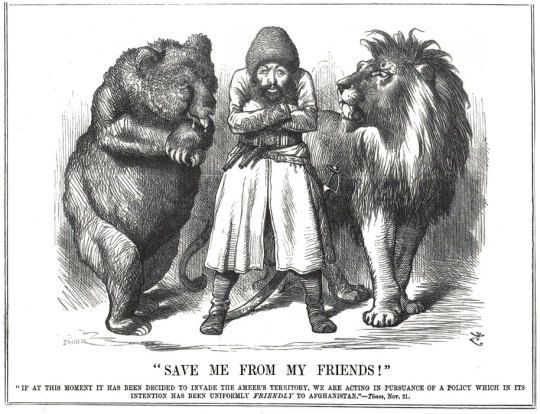

Although never colonised in the same manner as other central and south Asian countries, the modern Afghan state is very much a creation borne out of great power rivalry. A land occupied by a number of different ethnic, linguistic and religious groups, it is a country whose borders were defined by, and whose sense of national identity was forged in response to western great power competition. Its geopolitical position - landlocked, mountainous, and surrounded by past great powers and present regional rivals - lends Afghanistan a dual role of geographic obscurity and great strategic significance, and has as such frequently been treated as little more than a buffer state between empires and a proxy of local powers. Its shared historical border with Russia and British India made it an object of imperial intrigue and, by consequence, has been subject to five European military interventions in the last 175 years.

The first three interventions of these occurred during the era of ‘the Great Game’ in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in which Britain and Russia (latterly the Soviet Union) competed for influence and control over Afghan politics in order to protect their respective imperial holdings in India and central Asia.

The fourth and fifth interventions, ranging from the late 1970s to the present day, similarly involved attempts by Soviets and then by an American-led international coalition to remove political leaders acting against their interests and to protect their favoured candidates.

The unifying feature of all these conflicts was the idea of Afghanistan as the site of potential threats to the interests and security of more powerful states.

Britain’s legacy in Afghanistan in particular set the tone for the country’s historical pattern of conflict and political contestation, fuelling both the intermittent emergence of Afghan national consciousness and a fractious political lineage that saw thirteen amirs in just eighty years. Interventions by the Empire during the Great Game set the conditions for the assassination of ostensibly national leaders by their compatriots (Shah Shuja Durrani in the First war) or their exile by the British (Shere Ali Khan and Ayub Khan in the Second).

Despite the British achieving their aim of protecting India in the second and third conflicts by maintaining Afghanistan as either a pro-British buffer state or as a neutral party, the Afghan narrative tends to emphasise successes such as the massacre of British forces retreating from Kabul to Jalalabad in 1842, the defeat of British and Indian forces at Maiwand in 1880, and the gaining of sovereignty in foreign affairs in 1919.

Soviet intervention in the late 1970s and 1980s further buttressed this identity of resistance, and the failure and ultimate overthrow of the Communist-backed Najibullah government, as well as the collapse of the Soviet Union shortly after their drawdown from Afghanistan, led to a sense amongst the victorious mujahidin of the country as the ‘graveyard of empires’.

Afghanistan’s modern history should thus be seen as inextricably linked to the ebbs and flows of great power politics. Each intervention exacerbated extant internal power struggles between rival elite individuals and groups vying for nominal control over the country. Foreign intervention in Afghanistan was met on each occasion with fierce resistance from tribal militias coalesced around religion; as has been remarked upon by one historian of the country, the threat of external domination has been one of the few means of uniting its disparate population around the concept of an Afghan ‘nation’, and in most cases this shared sense of identity cohered around religion, not nationalism.

Indeed, the presence of intervening powers and the development of the Afghan state may be seen as mutually supporting: whilst most Afghan leaders throughout the last two centuries have asserted their sovereignty over the country, the reality has in most circumstances been one of competing tribal chiefs and/or ‘warlords’ rather than a single dominant leader.

Where leaders have managed to cohere the disparate tribal and ethnic groupings of the country under one banner - most notably under the regime of Dost Mohamed Khan (1826-1839, 1845-1863) – this was due in large part to their diplomatic abilities of compromise and co-optation with Afghanistan’s regional power- brokers. In other cases, such as that of the reign of Abdurrahman (1880- 1901), power was maintained by an unflinching ‘internal imperialism’ and the use of punitive force against rebellious factions.

The challenges of maintaining and projecting centralised power in Afghanistan allow us to see the relationship of its leaders with world or regional powers in the last two centuries as one of mutual exploitation. Throughout the Great Game and the Cold War, whilst the British/Americans and Russians/Soviets would use threats and bribes (and occasionally force) to compel Afghan rulers to comply with their geopolitical needs, Afghan rulers themselves often deftly manipulated those powers to maintain and extend their own power.

The pattern followed by Afghan leaders from the nineteenth century to the present day is remarkably similar in the respect that most have relied upon a rentierist economic model, seeking external aid in order to sustain the cost of security and administration. The plan of modern rulers was to warm Afghanistan with the heat generated by the great power conflicts without getting drawn into them directly. Abdurrahman, for example, used British subsidies to fund his military campaigns against rebellious factions; the Musahiban rulers of the mid-twentieth century used American capital to develop its nascent economic infrastructure and Soviet finance to bolster its armed forces; and, following the overthrow of the last royal leader of Afghanistan, Mohamed Daoud, in 1978, the quasi-communist leadership of Babrak Karmal, Hafizullah Amin, Nur Muhammad Taraki, and Mohammad Najibullah during the late 1970s and 1980s relied in the main on Soviet money and military assistance in its ultimately failed attempt to implement socialist policies and put down the American, Saudi and Pakistani-backed mujahidin.

These trends continued into the post-Cold War period in respect to both the Taliban movement (essentially directed and funded by Pakistan), the Northern Alliance (funded largely by former Soviet central Asian states) and the regime of Hamid Karzai (maintained in economic and military terms by the American-led, NATO-operated International Security Assistance Force and the wider international community). In the former cases, occurring in the main in the period of civil war between 1992 and 2001, rentierism was limited to the maintenance of proxy parties and the continuation of conflict.

By contrast, the ISAF mission bore similarities with the Soviet-backed socialist regimes of the 1980s, insofar as it focused huge amounts of capital and military resources on stabilisation and state-building efforts. Both intervening parties made the error of ignoring Afghanistan’s political history and focused their efforts on bolstering the authority of a centralised state, both promoted policies that were deemed ‘universal’ in their application and were, unsurprisingly given such hubris, vulnerable to accusations by Afghan opposition to being alien and imperialistic ideologies, and both expended enormous amounts of blood and treasure in order to sustain the regimes they supported.

The UK’s struggle to locate a coherent strategy for Afghanistan should, therefore, be seen firstly in the light of the historical problematic of Afghan state-building. This is important in narrative terms because difficulties of defining strategy imply similar challenges in explaining strategy. As with its efforts to ‘think’ strategically, Britain’s ability to explain the strategy(ies) for the war in Afghanistan have been frequently criticised by various commentators. The most strategically debilitating aspect of the Afghan campaign has always been the incoherence of the mission’s purpose; indeed the question ‘‘why are we in Afghanistan?’’ has never really been settled in public consciousness. The international community massively underestimated the difficulties of state-building and greatly overstretched themselves in the commitments made to Afghanistan, and that they did so because ‘strategies’ for Afghanistan rested on assumptions of the universal applicability of liberal state-building.

The international community from the start (meaning from the Bonn Conference of late 2001) fundamentally misunderstood the nature of an Afghan society deeply ravaged by decades of conflict, and failed to foresee the malign effects state-building ventures would have on the country. Specifically, the Bonn Conference, which set out the parameters of the post-invasion Afghan state, implemented a centralised state system onto a state whose experience of such was limited, and where the success of such a system in extending its authority beyond the major cities was predicated on coercion and the use of force.

Historically this has rarely been a credible option for Afghan rulers or their international backers, and was even less so under the self-imposed restrictions of liberal war-fighting and state-building. Rather, re-creating a centralised state required Afghan and international actors to enter into the same methods of co-optation and compromise as those of the past; in necessitating these kind of measures – as opposed to implementing a looser, federal system of governance – the centralisation of the Afghan state paved the way for a reconstitution of a ruling order based on tribal elements and ‘strongmen’. This produced something of a paradox for state-builders, as the creation of a strong, central state capable of implementing liberal policies across Afghanistan came at the cost of entering into alliances with ‘warlords’ known for their illiberal and coercive political approaches and illicit economic activities.

Another unintended but unavoidable consequence of centralised state-building identified by scholars is the re-constitution of the rentier state in Afghanistan. Post-Bonn, Afghanistan returned to its historical norm of maintaining the state via the extraction of external security and development rents, without which it would almost certainly implode due to the ruinous state of its economy and taxation system. Studies have shown that his new rentierism differed from previous patronage systems at the state level insofar as it was fuelled by an unprecedented influx of capital and resources into the country. This had the effect of introducing regulated systems of ‘neo-patrimonalism’, where departments were to be distributed as rewards to the various factions that took part in the Bonn conference, and there had to be enough rewards to go around.

In other words, the structure of the post-invasion Afghan state was, to a great extent, defined not by the demands of good governance, the needs of the country or the demands of post-conflict stabilisation and reconstruction – the purposes for which the centralised model was chosen to promote – but rather by the first-order need to avoid the derailment of the centralised state by co-opting regional power brokers.

Because of the imperative of shoring up a nascent state by securing support from potential competitors, the gulf between the ends of liberal state-building and the illiberal means required to facilitate its functioning can therefore be seen to a certain extent as inevitable.

A major issue, however, was that the patrimonial linkages created by the state for its regional proxies was not comprehensive, as it did not extend to the Taliban’s Pashtun heartland and, as such, fuelled resentment and alienation as much as they placated and co- opted extra-state power brokers. Key players in the Northern Alliance - the primarily Tajik opposition to the Taliban - received prestigious posts within the state, whilst the predominantly Pashtun Taliban were themselves excluded from such arrangements. Because those rewarded by the state tended to be given ministerial or governorial roles in cities, the conflict dynamic tended to reflect an urban – rural divide similar to that of the Soviet occupation. Along this reading, the neo-Taliban insurgency was in many ways a product of the political miscalculations and deficiencies of post-invasion state- building activities.

Given this starting point, such a view concludes that the strategic problems encountered by the international community in Afghanistan were, to a large degree, problems created by (or at the very least exacerbated by) the state-builders themselves. They misread Afghan politics in a way that reflected their own philosophical assumptions about the state and society.

Strategy in Afghanistan suffered because the coalition effort, comprised of multiple national actors and the United Nations, rarely took on the form of a unified effort. Part of the reason for this was a divergence of opinion between actors as to the ultimate purpose – counter-terrorism or state-building – of the intervention.

In the first years of the Afghan campaign, the United States’ Bush Administration remained staunchly opposed to what it called ‘nation building’ and opted instead to pursue a policy of capture- or-kill missions against suspected terrorists. For the United Nations and most of the United States’ European NATO allies, however, state-building was considered a necessary element of any counter-terrorist strategy. This difference of opinion was manifest from the start by the creation of two parallel missions – the US-led, counter-terrorism-focused Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and the stabilisation missions of the European Union, United Nations (United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA)) and NATO (International Security Assistance Force (ISAF)) – engaged in seemingly incompatible aims of military prosecution and peace building.

Opinion on the impact of this dual approach varies. Some scholars have noted, along lines similar to those critiquing the state-building efforts of the international community that the approach taken by the UN, EU and ISAF was too ambitious, naïve and unrealistic, and therefore bound to fall short of their liberal political and economic goals. Both Europe and these international agencies ignored the necessity of paring down the international community’s state-building efforts to core, security-centric capacity building within the Afghan National Security Forces. But of course one can make the counter argument, as many have of course, that on the contrary it was the insufficiencies of state-building approaches vis-à-vis OEF’s counter-terrorist approach that led to subsequent failures in UN and ISAF efforts; specifically, that a disproportionate focus on counter-terrorism missions meant that opportunities of peace- building were irreparably compromised.

Within NATO there was a division not just of opinions but also one of mission relating to different political perspectives about the purpose of the Afghan mission and its ultimate referent object – whether it was primarily about the interests of the coalition member states or concerned in the main with Afghanistan itself – and, from that, the methods to be employed in pursuit of one or another objective. This was not merely a debate bounded by strategic necessity, however; rather, such debates stemmed as much from institutional disagreements over who would or could do what in Afghanistan, which in turn arose from the differences in political constitutions and cultural attitudes towards counterinsurgency and counter- terrorism.

These ‘national caveats’ or ‘red cards’ of participation created significant problems for NATO in Afghanistan, both political, in terms of the relations between states and the abiding sense amongst some that others were ‘free-riding’ on the collective security system and, and strategic and operational, in the sense that command-and-control capabilities and cohesion between forces were limited by the engagement restrictions placed on certain armed forces. Indeed, the disproportionate burden placed on combat-oriented states like the United States, the United Kingdom, and several new member states in Eastern Europe led to political statements denouncing Europe’s perceived transgressors of collective security participation; former US Defence Secretary Robert Gates argued, for example, that NATO had effectively become a ‘two-tier alliance’ ‘between members who specialise in ‘soft’ humanitarian, development, peacekeeping and talking tasks and those conducting the ‘hard’ combat missions - between those willing and able to pay the price and bear the burdens of alliance commitments, and those who enjoy the benefits of NATO membership... but don’t want to share the risks and the costs’.

A lack of strategic unity was the natural consequence of a structural compromise that produced two distinct strategic authorities that were, in many ways, competing with one another. Along similar lines to the political arrangements between the Afghan state and its regional proxies, the NATO alliance structure can be seen (and evidently is seen by officials such as Gates) as patrimonial: states participated on the basis of fulfilling their own interests and along operational lines that were complementary to those interests, for the purposes of securing an alliance structure that accommodated all participants ahead of the imperative of creating a coherent strategy for stabilising Afghanistan. As with the neo-patrimonialism of the Karzai regime NATO’s efforts would be dictated by the limitations imposed upon it by circumstance.

Thus, in the cases of Afghanistan’s and the international community’s internal political dynamics, strategy was confined by the structure of the Afghan state and society, the structure of the international community and NATO, and the interplay between those structures. The implication here is that the agency required for the possibility of a workable strategy may have been illusory from the start.

Leaving Afghanistan was never going to be pretty, but the latest turn is uglier than expected.

No one quite expected the speed of collapse within the Afghan National Army to hold of attacks of the Taliban. I don’t think it’s do with the lack of training or their professional skills is lacking (though there may be some truth in it). A big driver in the collapse is the money for wages, food and medical care for troops is syphoned to Dubai, so the Afghans who want to fight, and there are quite a few who hate the Taliban, get less replenishment than the 6th army in the last weeks of Stalingrad. They have arms, ammo and boots for this season only and that is it. Both money and morale are in short supply for these soldiers.

If I was a trained soldier in the Afghan National Army I would desert. I would say to them abandon the fixed defences these ‘ferenghis’ (foreigners) have gifted you and move to the hills and seek refuge with your tribal clan, who will be glad of the arms and experience you bring. Or get over the border if you are lucky to be in the North, if in the West you hire yourself to the Narcos in the badlands on the Iran border. Most other places it is either a last stand or defection, your Government and their relatives have already got their planes fuelled up in Kabul ready to move to their villa complexes in the UAE.

I’m being a trifle cynical but for good reason. Everyone who has been to Afghanistan sees the veil lifted on the corruption of aid and how the elites protect themselves ahead of defending the masses who bear the brunt of the bloodshed.

The corruption has been endemic from the get go, but the international community ignored it all for 'progress'. Any Afghan politico you hear on the media complaining about the West abandoning Afghanistan has at least $30 million parked in Dubai that should have gone to the soldiers, teachers, doctors, builders etc.

As spectacular as the collapse of the Afghan National Army has been it’s been even more scarier seeing how swift the Taliban has been in taking over vital provincial areas through propaganda, civilian intimidation, and rapid attacks. One by one, the Taliban has been taking over areas in a number of provinces in northern Afghanistan in recent weeks. The Taliban says it has taken control of 90 districts across the country since the middle of May. Some were seized without a single shot fired.

The UN's special envoy on Afghanistan, Deborah Lyon put the figure lower, at 50 out of the nation's 370 districts, but feared the worst was yet to come. Most districts that have been taken surround provincial capitals, suggesting that the Taliban are positioning themselves to try and take these capitals once all foreign forces are fully withdrawn. On a map, it's easy to see the point Lyon is making. A stark example is Mazar-i-Sharif, the biggest city in the north and a significant power centre in its own right. It was the rock upon which the Northern Alliance fought against the Taliban.

It is significant the Taliban are kicking off this offensive in the north, not their heartland in the south and east. The north was the toughest part of the country for them to crack last time. Their expectation is if they have victory there, success will flow much easier in their traditional homelands further south.

The strategy of taming the north extends to emasculating and profiting from trade routes to neighbours. On Monday night they captured the important border town of Shir Khan Bandar, Afghanistan's main crossing into Tajikistan. Earlier in the day, top Tajik government officials had met to discuss concerns about the growing instability next door. There is no indication that the Taliban intend to take their fight north of the border, but in the past Tajikistan has been a vital conduit for supplies flowing to the militants' northern enemies.

The last time the Taliban controlled the city was 20 years ago, when they left hundreds of captives in steel trucking containers to suffocate and die in the scorching desert heat. Now, the militants are back at the city gates once again, as part of a lightning offensive against Afghan government forces that has set alarm bells ringing from Kabul to Washington. So it should worry us all where will all this lead to.

America's drawdown seems to be the game changer. The Taliban have been beaten back several times in recent years, notably from Kunduz in 2015. The Taliban captured it briefly before US airstrikes were called in. Civilian casualties were high but the militants were driven out. The militant group has never been able to withstand the heavy US and NATO air assaults backing Afghan ground forces, but now the US and NATO are leaving, so is much of the threat of sophisticated and sustained air power. And the Taliban are well aware of this.

It seems to me behind the choice of withdrawal by the Biden government lies a bigger assumption that drives that choice. That is the Taliban militants' perceived desire for international recognition. This has been the mantra underpinning the American exit. The logic of the American argument has been simple: The Taliban wouldn't renege on their agreements with the US because they crave international acceptance. The events of this past week and more appear to blow a hole in that assumption.

Another assumption that’s currently being blown out of the water is the US establishing some presence outside of Afghanistan so that if it needs to intervene again to combat terrorism or flush out militants then it can do so from the safety of a neighbouring country. But so far no country has come forward to reciprocate. And why would they? Like the Afghans, no one likes foreign troops with boots on the ground in their country. Only the central Asian republics and possibly Pakistan would come close to allowing that but there would be a political cost those governments would pay with their people. Moreover by welcoming the Americans in, they also allow the militants to target that country too.

Another assumption is the nature of the Taliban support and links to terrorist groups. The U.S. may not face any serious post-withdrawal Afghan support of extremist threats to the United States, even if the Taliban does take over. It is all too true that the Taliban continues to talk to the remnants of Al Qaeda, as do elements of the Pakistani military. It is unclear, however, that these remnants of Al Qaeda focus on attacks on the U.S., and the Taliban does seem to oppose ISIS. It is also unclear that the Taliban will host other extremist movements that focus on attacking the U.S. or states outside the region.

It is unclear that any key element of the Taliban has an interest in such attacks on the United States. Even Al Qaeda now focuses largely on objectives inside Islamic countries, and it is unclear that some other major extremist force will emerge in Afghanistan that do not focus on regional threats and on taking over vulnerable, largely Islamic states.

At the same time, one needs to be careful about the assumption that the U.S. can defeat any such threats by launching precision air and missile strikes against extremist targets. It is unclear that the forces in Afghanistan involved in any small covert attacks on the U.S. will be easy to target and cripple if they do emerge. The Taliban is unlikely to tolerate major training camps and facilities for extremist forces, and any such strikes will present major problems for the U.S. if the extremist threat consists of scattered small facilities and small expert cadres that shelter among the Afghan population.

It is also far from clear that more intense U.S. air attacks on Taliban forces from outside Afghanistan will have any decisive effects. The loss of limited numbers of Taliban fighters as well as some key Taliban leaders and facilities will not offset the pace of their victories in the countryside or enable the central government to survive. A continuing U.S. ability to target and kill some key Taliban leaders and fighters also does not mean that the risk of such strikes will deter future Taliban willingness to let small, extremist strike groups conduct well-focused, well-planned strikes on U.S. or allied territory, especially if such groups in Afghanistan sponsor attacks on the U.S. or it strategic partner by strike units or cadres based in other countries.

At the same time, it does seem more likely that the Taliban, and/or any independent extremist groups, will focus largely on Iran, Pakistan, Russia, China, and the other “-Stans.”

Going forward I think we need to re-evaluate many of our assumptions about the war in Afghanistan.

The objectives of the Authorised Use of Military Force approved by the US Congress in 2001 have long been accomplished. Once Osama bin Laden was killed in Operation Neptune Spear in 2011, the last element of the AUMF was met. The American and British mission in Afghanistan was complete. But America and Britain did not leave because we wanted to do a spot of state building to curb the spread of militant islamist terror. That was a mistake as it turned out.

Post-Neptune Spear, The American, the British, and their allies’ conventional mission should have been ended, adopting instead a laser focus on intelligence collection and offensive special operations to prevent al-Qaeda (or any terrorist organisation) from re-establishing safe havens and training areas.

What was needed for an acceptable ‘victory’ and a ‘saving face’ withdrawal was to embrace the use of Afghan Militia Forces the same way the Allies did for our initial entry way back in 2001.

In 2001, Western powers won the initial military engagement in 42 days using special operations forces with local and regional allies - we need to return to this format - and through a combination of special operations and specific information operations efforts, regaining the high ground and influence over ‘centres of gravity’. The issue is not the number of troops, but the mission of the forces there. Once the mission is defined, the number of forces needed would be clear.

It has never been about the number of troops - it’s been about the lack of an achievable mission assigned to our forces in Afghanistan.

The US engaged in ‘nation-building’ for the wrong reasons - and has seen bad results. We installed Hamid Karzai, served as his praetorian guard to protect the new central government and abandon our AMF allies and attempted to build a large, bulky, expensive and ineffective Afghan National Army - a force that is now evaporating before our eyes. It was folly.

Americans will never make the Afghan people more like them - nor will they be able to instil what my American colleagues used to fondly refer to as ‘a Jeffersonian democracy’ in Afghanistan. That day may come but only when the Afghan people wish it to be so. Lest it be forgotten Americans sought independence in 1776; the Afghan people seek self-reliance and independence from foreign influence. This is their defining historical DNA: escape from any outside control.

The Afghan people are not ungoverned, they are self-governed - with no tradition of central democracy and no desire for our version of democracy or ‘prosperity’. By pushing ‘prosperity’ we had become targets for both the Afghan government and the Taliban. This has ended, but we must draw a distinction between the end of nation-building and the continuation of our own interests in Afghanistan and the region.

It is time to adopt a practical policy based on what will work and is in our allied interests, rather than by funding the aspirations of progressive politicians who have no real understanding of Afghanistan.

First, we must establish a clear post-‘state-building’ strategy - with achievable objectives. We must return to the policy and operational format we know will work - cooperation with Afghan tribal leaders and militia. This type of force was used to achieve the initial victory in 2001. Empowered warlords and regional leaders were the force multiplier that worked as the Afghan Militia Forces - and can again, in partnership with our Special Operations Forces work now. Intelligence collection and limited military operations should be our focus.

There is no way around it. One has to play the Great Game. Think tribal rather than central. Afghan nationhood is a liberal Western wet dream.

The central government is weak and corrupt just like all the other rulers of the past. The Afghan National Army is not as strong as it is on paper. It can hardly prop itself up rather than any government. Most of the Afghan National Army troops have stronger tribal loyalties than to the concept of a nation. Since the tribal chiefs play both sides to hedge their bets, it's no wonder 'their' people do what they're told. The Taliban know this because that has always been the Afghan way, so the tribes go with them. Provided the Taliban honour their promises to the tribal chiefs, the Taliban can do what they want.

On one hand, the tribes won't now be too bothered by central government and have a large pool of Western-trained troops to prop them up. On the other hand, they now have to do business formally with the Taliban again. Largely in order to get their hands on Western-supplied aid that will surely follow after the Americans leave.

Second, we must accept the reality of Pakistani influence in Afghanistan - and work with the Pakistanis to counter al-Qaeda and the other militants now attacking Pakistani targets within Pakistan. Pakistan has made great advances in securing the tribal areas on the other side of the border and they have always been the de facto control of much of the Taliban force capacity, such as the Haqqani network. Working with Pakistan is the best option within the current circumstance.

‘Endless wars’ are not an American value. The use of the US military must only be used in response to genuine threats, when American interests are at stake or lives in danger. Withdrawal of conventional military forces and discontinuing nation building is in the US interest: leaving Afghanistan is not.

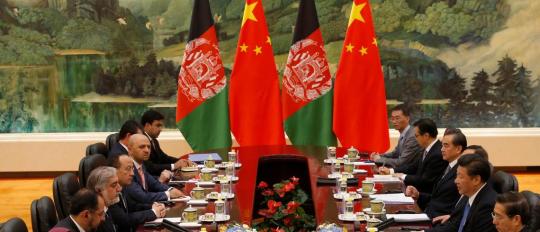

Third, make Afghanistan China’s problem. Afghanistan could easily become a hotbed for growing Islamic extremism, which would to some extent affect stability in Xinjiang.

It is not without reason that Afghanistan is known as the “graveyard of empires”. The ancient Greeks, the Mongols, the Mughals, the British, the Soviet Union and most recently the US have all launched vainglorious invasions that saw their ambitions and the blood of their soldiers drain into the sand. But after each imperial retreat, a new tournament of shadows begins. With the US pulling out of Afghanistan, China is casting an anxious gaze towards its western frontier and pursuing talks with an ascendant Taliban. The burning questions are not only whether the Taliban can fill the power vacuum created by the US withdrawal but also whether China - despite its longstanding policy of “non-interference” - may become the next superpower to try to write a chapter in Afghanistan’s history.

Beijing has held talks with the Taliban and although details of the discussions have been kept secret, government officials, diplomats and analysts from Afghanistan, India, China and the US said that crucial aspects of a broad strategy were taking shape. An Indian government official said China’s approach was to try to rebuild Afghanistan’s shattered infrastructure in co-operation with the Taliban by channelling funds through Pakistan, one of Beijing’s firmest allies in the region. China is Pakistan’s wallet.

It has been reported that Beijing has been insisting that the Taliban limit its ties with groups that it said were made up of Uyghur terrorists in return for such support. The groups, which Beijing refers to as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, are an essential part of China’s security calculus in the region. The ETIM groups were estimated by the UN Security Council last year to number up to 3,500 fighters, some of whom were based in a part of Afghanistan that borders China. Both the UN and the US designated the ETIM as terrorists in 2002 but Washington dropped its classification last year. China has accused the ETIM of carrying out multiple acts of terrorism in Xinjiang, its north-western frontier region, where Beijing has kept an estimated 1m Uyghur and other minority peoples in internment camps.

In a clear indication of Beijing’s determination to counter the ETIM, Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, exhorted counterparts from the central Asian states of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan this year to co-operate to smash the group. “We should resolutely crack down on the ‘three evil forces’ [of extremism, terrorism and separatism] including the East Turkestan Islamic Movement,” Wang said in May according to Chinese news media which I follow.

The importance of this task derived in part from the need to protect large-scale activities and projects to create a safe Silk Road. Silk Road is one of the terms that Chinese officials use to refer to the Belt and Road Initiative, the signature foreign policy strategy of President Xi Jinping to build infrastructure and win influence overseas.

An important part of China’s motivation in seeking stability in Afghanistan is protecting existing BRI projects in Pakistan and the central Asian states while potentially opening Afghanistan to future investments. China would have to more actively support efforts to ensure political stability in Afghanistan. So make them work for it. Western powers need to leverage China’s problems in Xinjiang to be more active in Afghanistan.