#paid old age home in pune

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sanctus Health Care is the best old age home in Pune.

Selecting the ideal care facility for a loved one or yourself is an important choice. Pune, a city full of life, also provides a range of care options. Sanctus Healthcare stands out among them all by offering patient care services that are especially catered to the requirements of the residents.

More Than Just an Elderly Residence: A Safe Haven for Healing and Rehabilitation

Sanctus Care offers more than just housing for seniors looking for a best old age home in Pune. Offering physical, occupational, and speech therapy services to promote healing and mobility, they specialize in rehabilitation. They are therefore the ideal option for anyone looking for rehabilitation centers in Pune.

Exposing the Expenses: Openness and Adaptability

It's crucial to comprehend the financial aspects. Depending on the care level selected, Sanctus Care has different monthly costs. But openness is essential, and upon request, they provide thorough cost breakdowns. Furthermore, adaptability is critical. Sanctus Care takes a number of payment methods, including private pay, insurance, and even government assistance plans.

Kindness Above and Beyond Expectations: Your Cherished Ones, Secure and Encouraged

Beyond providing basic amenities, Sanctus Care places a high value on the social and emotional health of its residents. Their committed staff provides round-the-clock care, attending to medical requirements and promoting warmth and camaraderie. Everyday burdens are eliminated with the provision of delicious meals, laundry, and housekeeping. The lives of residents are further enhanced by social and recreational activities.

Sanctus Healthcare is one of the best old age home in Pune: Get in touch with Sanctus Healthcare.

Sanctus Healthcare merits your consideration if you're looking for an old age home or rehabilitation center in Pune. To find out more about their offerings and facilities, go to https://sanctushealthcare.com/. Contact them by phone at +91-8380087093 or via email at [email protected] to arrange a visit and witness their kindness and expertise in person. Recall that selecting the ideal care facility is an extremely private choice. Explore their sanctuary, ask questions, and see if Sanctus Healthcare is the right place for your loved one's path to better health and happiness.

#rehabilitation center in pune#old age home monthly cost#best old age home in pune#vrudhashram in pune#paid old age home in pune

0 notes

Text

Paid Old Age Homes In Singhgad Road & Pune

Welcome to Sahvedna, we delight ourselves in supplying pleasant care offerings for our residents. The main objective of Paid Old Age Homes In Singhgad Road & Pune is to provide senior citizens with a safe and comfortable environment and convenience. The homes offer quality medical care, nutrition, and recreational and educational activities for the elderly. Senior care providers offer several services to ensure seniors can live healthy and fulfilling lives. Here’s what sets our paid old-age houses apart:

Key Features 1. Comfortable Accommodation:

We offer you well-furnished and comfortable rooms with a homely atmosphere.

2. Qualified Staff:

Our professional staff meets your specific needs and compassionate caregivers are trained to meet the unique needs of elderly residents.

3. Comprehensive medical care:

Regular health checkups, medication management, and access to emergency medical services.

0 notes

Text

Lost in the highway

My throat felt dehydrated and woke up every time I tried to take a nap.

Sheetal and Sonu were also getting affected by it, even after all these efforts.

Sheetal is my wife and Sonu, my 8-year-old princess. I could see that tightness on Sheetal’s face which led Sonu to estimate that Maa and Baba were going through a tough period.

Sonu was different you know. She somehow just knew things; every time I hugged her it gave me a sort of energy. Sometimes I would just touch her feet while going out with my tempo; her grandfather had once said that she will change our fortune like she was an avatar of the Goddess of fortune.

It was 15th day of covid induced lockdown. Sheetal woke up.

Sheetal was from Pune where I saw her for the very first time on one of my trips to Pune where I was loaded with Mangoes which came from Ratnagiri and had to drop in these world-famous Mangoes in Bandra, Mumbai. She had a small tea-stall nearby this famous North Indian hotel where I would have my lunch in the Mumbai – Pune highway. Post that moment of wonderstruck, whenever I had an order to pick something up from Pune my eyes popped out with excitement. I never felt this warmness in my solar plexus before. It was as if I was exposed to some new form of malady, mind-blindness.

And this continued over the next one year. Thenceforth my hours of darkness were meant for her and night after night I was dipped into this puddle of fondness. She was like that sudden rain in the barren land of Arica.

Sheetal begged me to sleep for an awhile anyway; she knew what I was going through this unforeseen pandemic.

If not a virus, we may die out of starvation. I replied.

Making way for complete silence and rattling sound that hopped around our ceiling fan.

25-08-10,

She wore a red kurta with tiny red dots in it, how can I forget that day I finally approached this lady from Himachal.

Sheetal and her baba after her mother`s sudden demise, migrated to Pune from a tribal village of Bada Bhangal situated in the lap of beautiful Himalayas in Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh, selling everything which they had and leaving behind all the memories in search of a better life.

So how did you educate yourself for this art?

I asked (back in my mind I knew it was quite an off start for a conversation with someone you crush upon)

Then came her reply, a clumsy look at my lame inquiry.

I paid her for the cup of tea and left with a gawky feeling.

That return journey from Pune to Mumbai was all about hoodooing myself for my stupidity. All of that which I thought of last night nothing came to be true or maybe it was me who is an amateurish in this differing field of devotion and this led to the formation of a desire that ‘I can’.

In my next trip I will be much more error-free, I told this to inner me and slept.

That night after Sheetal urged me to sleep for some time I saw this dream, where a cannibalistic monster broke through our window, opening up its hungry jaw to gulp down Sonu. She stood feeble and small to this huge monster, wailing out for help. At once I came to her rescue and realized that this monster was not new to me. I was assaulted too just when I was about her age. He is Preta, also known as the Hungry Monster which comes out of extreme hunger and thirst, just after it spotted me. He left. I woke up again and started fondling Sonu while she was asleep like a newborn baby.

I was being more apprehensive, every time I gazed over Sonu. It was getting difficult for us. It seemed this lockdown was hooking us up for something worse.

09-09-10

Some things cannot wait. You have to rush and run to get a few things that you want from the core of your heart, said Sagar. Sheetal is one of them.

I knew this was not just a lecture indeed an advice given by my very own Parthasarathy.

I told him every minute detail about Sheetal from where I saw her for the first time to all these thoughts which are rolling over my mind. Sagar was one of my closest ones since I had shifted here in Mumbai from Mathura. From helping me rent this small Kholi in Mahim to lending funds for my Tempo, he had constantly stood by my side.

He was the manager in this North Indian hotel where I worked for a short period, suggested by my uncle who also lived in Mumbai. My journey in this city of dreams started from this small hotel in Colaba and gave me Sagar. He too belonged from Uttar Pradesh.

A day after Sagar’s advice, I took with me whatever money I had in my Kholi and left for Pune with my tempo. This 148km trip was about to be the dawn for a new beginning. With this intoxication in my head, mind, and soul I wanted to reach Pune as soon as possible, tell her about these thoughts which were constantly rolling over my head. I wanted to tell her how much I loved her, that it is difficult to keep it a secret any longer. I wanted to make her mine.

Finally, at around 12 in the noon I reached, my heartbeat rose like I was suffering from Tachycardia. Right after I seized my key and got off my Tempo my heart crashed. She was missing. No stall. Luckily one of the guys working in the hotel told me her whereabouts. She lived in a village, next to this stop. Trailing by her intoxication I finally reached this small draggled Kholi where Ramesh Juyal and his daughter lived. Yes, Ramesh Juyal was Sheetal’s father. And then I saw her, she came out of the Kholi as chotu called her ‘Sheetu Di koi Apse Milne Aya Hain’.

I was never this nervous before, not even when I arrived at the CST for the very first time.

It’s almost 11 am and I have been standing here in this queue for about 6 hours by now, that too for a plate of Khichdi. We stepped in the 19th day of this lockdown, nearly out of our rations.

From the last few days, we are dependent for our lunch to the free food distributed by a local NGO.

10-09-10,

She was shocked. I could see that in her eyes. She was angry too but she recognized me and that directed some amount of optimism towards my self-confidence.

Her father welcomed me into their little Kholi. It would be better if Sheetal had asked that first but you know I was not in any position to decide if anything was better.

It is Sheetal that has to decide not me and not you, Rameshji said.

I was in a state of shock.

Sheetal has already told me about you, that you have been stalking her from the last one year and also about your lame inquiry. And that was her mother who educated her with that art. Rameshji added.

I immediately took a glance towards Sheetal and caught her smiling. I realized that she knew it from the very first day itself.

I told them everything about my family.

A few months later we were getting married.

13-03-11 was the day

Sitting by the holy fire she hissed these words into my ears ‘I knew you would come searching for me’.

Today was our 9th Marriage Anniversary, midst such vulnerability.

Most of our neighbors were abandoning which I never witnessed before.

Altaf and his family are the ones of who we were closest to,

For Sheetal, Altaf’s spouse was like her own sister. It was Rubina who prearranged everything from Griha Pravesh Ceremony to Mooh Dikhai Ceremony following all the required norms at our marriage. It was Rubina who asked Sheetal to push the Kalash full of rice with her right toe marking her entry to this Nuclear Desai Family.

From that day onwards Sheetal and Rubina formed an indivisible bond with each other.

Roza came running in weeping and embraced Sheetal. She didn’t want to leave her dearly loved Bua.

Roza was Altaf and Rubina’s daughter. It is also worthy of note that Roza’s very lovable name was not given by her parents but her Bua.

Rubina, Sheetal, Sonu and Roza assembled when I and Altaf were away from home, spending most of the time looking for each other, not even a single day passed by that Sonu and Roza never fought with each other. Yet when they had to leave each other in the dusk, it was like they were profoundly affectionate of each other.

After our dinner, I and Altaf walked around talking about life over a Gold Flake.

This was the routine.

Without them, we were about to feel abandoned in this Concrete Jungle of Mumbai.

Sheetal brought these small cakes from a shop to celebrate this day.

In the morning I got a call from my Landlord.

The Government of India called for all the Landlords of this Country to consider some sort of relief and play their part by dropping in this month's rent, very few played their part considering this to be government's responsibility, not theirs.

3 missed calls from Ramdas Bhau. He was desperate. I knew this because whenever there was a little bit of delay in the payment of the rent, he would resort to this method to jog you up that water was about to run over his head.

I smiled each time it had happened earlier than but today I was bothered.

I didn’t have it. I was almost out of my savings.

You know that made me feel so helpless and that’s not easy when in the back of your mind you know that it was going to cause something to my Sonu and Sheetal.

You are edgier for the facts that they are all that you hold in this world, which you can call yours which is more important than any of the material things which you have earned to date. You could survive without a roof but not looking at them without it.

Sheetal lost her father a few years ago. So I was her shield in this pitiless world, ever ready to hunt you down once it espies you out in a state of feebleness.

And when I see Sonu, I feel the most terrible. Dreams crashing down.

I have some money in my account which was transferred in my account after Baba’s death. Sheetal murmured.

Hearing these tears rolled down my eyes.

Ladies will just rescue you while you are about to fall. Respect them. Sagar once said.

20 lakh crore relief package was announced by Modi Sahab

It bewildered most of my neighbors who were now on their way home by foot but deep inside I knew this was never going to reach to us. It would be foolish on our part that someone would be knocking at our door and give away food items. This is India nothing comes so easy in this country except these promises.

This small kholi of ours seemed to be engulfing us, with electricity also being cut off by our landlord. He was letting us live in this kholi since if he throws us out; it was to cost him his status in the society. I have realized a few things these days like, for example, this city has big buildings but living here are the ones with a very undersized heart. Some would just come to help us to post pictures in the social media as it was the trend with little sympathy about our lives. And some to perk back up their political career. I recently saw an interview where Mr. Rahul Gandhi the scion of Gandhi Parivar asking the government to give money in the hands of the poor. I smiled after hearing it for the reason that of the condition of this city with 49% of its population living in the slums. And this was not something that happened because of the unjust policies of the present government. This was because of prolonged exploitation of all the government which had ruled over us, most of it was by his party.

You must be thinking how come a tempo driver knew so much about politics. I am, sorry I was a Graduate with honors in political science which never came to my rescue though.

My father was dhobi who washed clothes in our village in Mathura district of Uttar Pradesh. My grandfather did the same and my great grandfather too. This was in our bloods, washing clothes. Yet this tempo driver broke this tradition by believing in something just beyond washing clothes. I was inspired by our Masterji of our town, who was respected the most in the village, with very little awareness of the cost of reaching there.

I completed my graduation and started searching for jobs, amidst this process I realized that it was a paradox, when some said that earn a degree and get a job that they didn’t tell me, was along with the degree you need some connections with the upper Mahal.

But my fate was written down with lots of bombshells. I did get an appointment letter but it never came-up-to-me because one of my buddies who worked at the Post office didn’t even update me about the letter. It was a payback of how come the son a dhobi could get more percentage than the son of a Daroga in HSLC examination.

Despite such setbacks, I continued with my struggle which was taking me nowhere and after a few years, even that stopped when I lost my only hope, my father, Sonaram Desai, while Maa left both of us when I was 13years old.

And left for Mumbai. In search of a better life.

I woke up this morning with a very bad dream and immediately hugged Sheetal. They were my only wealth which I had earned to date and decided to return to Mathura. We still had the house and a little bit of land left back there, which would be enough for us to survive for a few days and come back to Mumbai when everything was normal again. I told you with me it’s always like chalk and cheese, my plans are as poorer as my life, very little idea what the future had in its store for us.

I told Sheetal to start packing and get the essential items which we would need in our 5days journey. We decided to leave on our Tempo. Sonu was very excited.

This was going to be her first trip outside this city of dreams, she told me that she would go get Pari dressed; Pari was her favorite doll.

We were ready to leave this morning. We also paid the rent of which our landlord was so much anxious about; this was general because many of the laborers left for their villages without paying rents.

I was driving and sitting next to me was my daughter and my wife.

We reached Dhule when something big hit us from the back.

I had come to Mumbai in search of life which was better than the place I was born. But to my surprise this city was the worst, you live, you die; none of them cares. Here in this city people are living in big buildings with a cold blooded heart.

Modern Varna system in an urban suburb.

Where is Ram asked Sheetal

She was surrounded by a doctor and nurses.

Where is Sonu again asked Sheetal

The Doctor urged her to calm down.

She screamed. Where are they

They are no more. They both died on the spot.

Replied, doctor of the Dhule Civil Hospital.

Ram told us, we know very little of what the future has in its store for us.

And for Sonu, it turned out to be the first and the last trip at the same time.

She was asked to press charges against the man who had hit their tempo from the back to which she declined. We are all familiar with how it ends and the process.

12 years has passed by now, Sheetal has mastered the art of living with the memories of her late family.

She lives in Mathura. She floats, with the survival instinct of a cockroach.

1 note

·

View note

Text

FROM RAGS TO RECOGNITION : SWaCH LEADS THE TRANSFORMATION

Garbage. A word that’s more abhorred than adored for quite obvious reasons. While all of us, in one way or the other, contribute in creating garbage on a daily basis, we are averse of its presence around us – whether at home, neighbourhood or streets. We want to get rid of the filth every day so that we don’t have to bear the stench from the piled up waste.

While every city administration employs staff and officials who collect garbage on daily basis and take it to the landfills, the role and efforts of the rag pickers are always ignored and overlooked. They are perhaps one of the most marginalised sections of the society and therefore never talked about. Forget dignity, they find themselves being treated like ‘garbage’, even when they willingly dirty their hands by scouring through the filth that’s not even generated by them. If not for livelihood, would anyone spend a better part of his / her day, every day, amidst nightmarish working conditions?

A new era dawns in Pune (India)

Circa 1993. The waste pickers of Pune in Maharashtra, one of the largest states in India, scripted their exit out of the rubbish heaps and landfills to transform their lives forever. They unionized themselves to define legitimate workspace for themselves in municipal solid waste management that improved their working conditions. Thus was formed the Kagad Kach Patra Kashtkari Panchayat (KKPKP), a movement that spearheaded the battle of waste pickers, waste buyers and waste collectors to be recognised as workers.

What KKPKP said was very simple. Waste pickers need to be treated with dignity and given their due status in the society because they recovered materials for recycling, reduced municipal solid waste handling costs, generated employment downstream, and contributed to public health and environment. They occupy an important place in the waste management and recycling value chain and contribute substantially to the manufacturing economy.

Surprised!! Take a breather, rethink over what’s aforesaid, and you can’t help but agree that rag pickers indeed need to be taken much more seriously than they have been since time immemorial.

Well, this argument was well understood by Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC), which in the year 2008, entered into an MOU with an offshoot of KKPKP christened Solid Waste Collection Handling - SWaCH.

SWaCH. A Higher Level of Self-Reliance.

A wholly worker-owned cooperative of waste pickers, waste buyers and waste collectors, SWaCH is conceived as an autonomous social enterprise. SWaCH Seva Sahakari Sanstha Maryadit, as it is formally known, provides front-end waste management services to Pune city with support from PMC.

Throwing light on the birth of SWaCH, Aparna Sasurla, Director of SWaCH says, “The organisation works on a well-defined model which was tested for two years (2005-2007) before being presented to PMC for support, approval and recognition. It was only after the success of this pilot project which established the workability and the potential of SWaCH beyond doubt, that PMC gave its nod to be integrated into the mainstream solid waste management system (SWM) of the city of Pune.”

Acceptance by PMC was like winning a long battle for SWaCH. In the crucial early years, the Corporation played a positive and enabling role in promoting SWaCH. It acknowledged that SWaCH model was indeed a cost-saving, sustainable and environmentally beneficial system which added value to the already existing but faltering solid waste management system of the Corporation. With passage of time, it became clear that the model of SWaCH had the required ability and the dynamism to bring about a fundamental change in the SWM system of Pune.

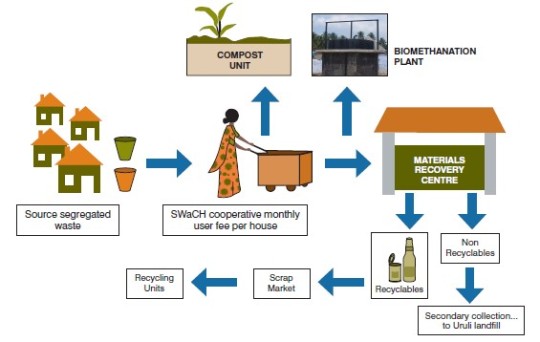

A Unique Model

SWaCH is an inclusive model that recognises the contribution of ‘invisible’ workers who play crucial role in keeping the Pune city clean. Different from the PMC model, SWaCH follows a green model of waste collection that is not heavily dependent on fossil fuel or electricity.

Talking about the significance of SWaCH in the SWM system of Pune City, Aparna says, “The importance of SWaCH is multidimensional and affects various people at different levels. To the residents, SWaCH is important because they get reliable service at reasonable cost and with accountability. To the waste pickers it is important because it gives their work a dignity while integrating them into the formal sector along with upgrading their livelihoods as well as standard of living. To the municipality it is important because the waste is collected in a more systematic manner and segregated at such nominal cost.”

Women constitute over 78% of SWaCH membership. While this holds for most age groups, the presence of men is higher in the youngest age group and among the aging. Most SWaCH members used to work as waste pickers or itinerant waste buyers. Housekeeping and cleaning workers constitute another significant group.

The SWaCH model is very unique in itself. Two workers collect source-segregated waste from 200-300 households, offices, shops and other establishments using manual pushcarts or motorized vehicles if the terrain is difficult. The waste pickers have the right over recyclables and retain income from the sale of scrap. This ensures maximum recycling and retrieval. Waste pickers separate the waste into wet and dry. Wet, organic and non-recyclable waste is handed over to the PMC. In some cases it is composted on site. Dry waste is sorted into categories like plastic, paper, metal, glass, leather etc. and then further fine sorted. Whatever has the market is sold.

The earnings of SWaCH members are derived from user fees and sale of recyclables. SWaCH members have relatively more stable income than other waste pickers in India. Their working hours vary from four to six hours including collection and sorting. Most also enjoy weekly holiday too.

Trials and Tribulations

As with every innovative idea, SWaCH too faces challenges from various quarters. From being slammed for being too transparent a model to being criticised as something that unnecessarily creates a parallel system, SWaCH has to deal with multitude of problems while still performing at its best.

“Other challenges notwithstanding,, the model being a user-fee based one is often met with resistance from the residents,” says Aparna. “Usually, we charge Rs. 10 to 30 per household per month in non-slum areas and in slum areas we charge Rs. 15 per household per month. We insist on user fees because SWaCH waste collectors are not paid by PMC for door to door collection. The service therefore needs to be supported by user fees paid by citizens. The fees facilitate a direct accountable relationship between the service user and the service provider.”

SWaCH+

As the primary collection system got established and began running in auto-pilot mode, the management of SWaCH decided to foray into allied activities to add more value and dimensions to their core endeavour. Calling it SWaCH+, the organisation began to offer services such as collection of unwanted household goods, collection of e-waste, garden waste, housekeeping and trading in recyclables. Under SWaCH+ the members are trained to handle mechanical composters and do manual composting. Members also work in bio-methanation plants established by PMC on Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) basis.

Innovations by SWaCH

Necessity is the mother of invention, they say. SWaCH too found it necessary to go in for innovation, both to sustain its operations and also create newer sustainable livelihood options for more waste pickers. The out-of-the-box thinking of SWaCH has not only helped the organisation to explore its hidden strengths but also upgrade its image in the eyes of its partners, stakeholders and everyone associated with the mission. A range of financial, social, environmental and other benefits for PMC, waste pickers, citizens, and Pune city as a whole are being achieved by the innovative steps taken by SWaCH.

V-Collect Programme

SWaCH collects old electronic, electrical items, furniture, bicycles, kitchen utensils, repair and re-use what can be, while dismantle and recycle the rest. By organizing V-Collect events, SWaCH channelizes most of these items towards recycling and re-use, away from dumps.

SWaCH collects old newspapers from households and use them to produce ST Dispo bags and carry bags. Members are trained in making ST Dispo bags with recycled paper, glue, and thread. As it looks distinct, it goes into a separate waste stream. The waste pickers are saved the indignity of handling soiled sanitary napkins directly. The bags are made available at local stores in different areas of Pune.

SWaCH collects clean, useable clothes, sort them out according to size, gender age and style and sell those at nominal prices to waste pickers and other urban poor. Torn fabrics are recycled into cloth products like bags, coasters and dusters.

Green School Programme

SWaCH in association with Parisar and CEE, has launched the Green School Programme which aims to widen the horizon of the school going children. The programme entails enhancing the children’s perspective on environment, sustainability and related issues. It helps students and teachers to carry out action-based projects to leading to environment conservation. It guides the school in setting up and implement best practices of solid waste and e-waste management. Throught he medium of hands-on activities the GSP covers topics like water, waste, energy, biodiversity, heritage, culture, traffic and transportation.

Nirmalya Project : Over the past 7 years, by diverting huge amounts of waste – both organic and biodegradable – from Pune’s rivers, SWaCH members has significantly reduced the pollution of rivers and dumping of nirmalaya on ghats. Last year itself, SWaCH diverted 177 tonnes of Nirmalaya. This has encouraged responsible citizens of Pune to be more eco-conscious. After receiving the Nirmalaya, SWaCH members segregate it into various categories such as fruit, flowers, clothes etc., send the flowers to composting units for conversion into natural manure, distribute good fruits for consumption and the rest for composting, take materials like paper, plastic and thermocol for recycling.

Composting : The PMC has made it mandatory for all societies formed after the year 2000 to compost organic waste. Towards this end, SWaCH helps to set up a composting system which takes care of the wet waste efficiently. For a small cost, a trained waste collector maintains and manages the compost every day. A supervisor also makes periodic visits to the composting site to ensure that all is well.

E-Waste Disposal : SWaCH has been authorised by the PMC to collect and channel e-waste according to the rules laid down by the government. SWaCH ensures the collection and correct disposal of e-waste at authorised PMC centres. Last year, over 7 metric tonnes of e-waste was diverted from the grey market and sold in the open market by SWaCH.

Success of SWaCH

In its eight years of existence, SWaCH has touched lives and livelihoods of the workers in ways that have made them more self-reliant, economically more stable and created a platform that promises to secure the future of the next generation.

Compared to their incomes as free-roaming waste pickers, the earnings of SWaCH members have increased manifolds since the launch of the initiative. Depending on the locality from where the collection is done, their income range from Rs. 1,500 per month to Rs. 15,000 per month. This has brought in stability into their lives which was absent in the days prior to SWaCH. It has helped them make plans for family’s future, educate their children and also save for the rainy day. Such has been the faith of the worker members in SWaCH that their well-educated children too have joined the organisation to serve the noble cause.

In a community which traditionally had little access to education and decent work, it is a matter of pride to see their children become the face of SWaCH’s future. Moreover, by branching out into waste related activities many waste pickers are upgrading their work standard, and in effect creating upward mobility in an occupation which was once considered lowest of the low.

The SWaCH initiative has come to represent the biggest effort to integrate waste pickers in India. The hitherto ‘faceless and nuisance-causing people’ are now people who interact with fellow residents on an equal footing. Surekha Gaekwad is a high school graduate and team leader of eight waste pickers. She and her team has diversified into housekeeping and composting. Sharing her transformation story Surekha says, “Five years ago, I spent my day at garbage bins. I ended up dirty and stinking by evening. I was looked upon with apathy and disgust. But now I have earned people’s respect. Today, when I go to collect my money, the lady there asks me to sit on the sofa. If she is drinking tea, she will order another cup for me.”

Mangal, another SWaCH member expresses her happiness in these words. “The residents in the area who used to frown at me, now call me by my name and greet me too. A resident gave me a second hand bicycle. I ride to work on the bicycle. Today I am literate and am the treasurer of a credit co-operative.” The twinkle in her eyes and the broad smile speak another thousand words which, though unheard, do not go unheeded.

Towards a Swach Future

Good work never goes unnoticed. In 2014 series of Satyamev Jayte, Bollywood super star Aamir Khan invited SWaCH to share their story and experiences, giving the organisation a national platform. It underlines that the efforts and the endeavours of SWaCh are slowly and steadily gaining recognition as more and more people become aware of SWaCH and its impact on the lives of over 3000 waste pickers who form the SWaCH Cooperative. The future of an organisation like SWaCH is indeed bright and with the support from the authorities, educated civilians and those good Samaritans, SWaCH will accomplish what it set out to achieve – taking waste pickers from rags to recognition.

#Pune#Maharashtra India clean cleanliness#waste recycling#Aamir Khan#Bollywood#E waste#composting#green school#thor ragnarok#rag#rag picker

1 note

·

View note

Link

https://ift.tt/2V1m1or

Editor's Note: In the run-up to World Population Day on 11 July, 2021, a six-part series on awareness regarding women’s and girls’ needs for sexual and reproductive health in different parts of the country will focus on the vulnerabilities during the pandemic. This is the first part of the series.

***

It’s 10:30 on a Sunday morning and Honey is getting ready for work. Standing in front of a dressing table, she carefully applies scarlet lipstick. “This will match well with my suit,” she says, as she rushes to feed her seven-year-old daughter. On the dressing table are slung a handful of masks and a pair of earphones. Cosmetics and make-up items lie unarranged on the table-top, while the mirror reflects photographs of gods and relatives hung in one corner of the room.

Honey (name changed) is getting ready to meet a client in a hotel some 7-8 kilometres from her home – a one-room set in a basti in New Delhi’s Mangolpuri locality. She is around 32 years old and a sex worker by profession, working in the nearby Nangloi Jat area of the capital. She is originally from rural Haryana. “I came 10 years ago and now I belong here. But my life has been a series of misfortunes since coming to Delhi.”

What sort of misfortunes?

“Four miscarriages toh bahut badi baat hai [are a very big thing]! They were for me, when I had no one to feed me, look after me and take me to a hospital,” says Honey with a smirk, signalling that she has come a long way on her own.

“This was the only reason why I had to take up this work. I had no money to eat and feed my child, who was still inside me. I had conceived for the fifth time. My husband had left me while I was just two months pregnant. Following a series of incidents arising from my illness, my boss threw me out of the factory I worked in, which made plastic containers. I used to earn Rs 10,000 a month there,” she says.

Honey’s parents married her off at age 16 in Haryana. She and her husband remained there a few years – with him working as a driver. They moved to Delhi when she was around 22. But once there, her alcoholic husband kept disappearing often. “He would be gone for months. Where? I don’t know. He still does that and never tells. Just moves away with other women and returns only when he is out of money. He works as a food service delivery agent and spends mostly on himself. That was the main reason I had four miscarriages. He would just not bring me any medicines that I needed, nor nutritious food. I used to feel very weak,” she adds.

Now Honey lives with her daughter in their home in Mangolpuri, for which she pays a rent of Rs. 3,500 a month. Her husband stays with them, but still does his vanishing act every few months. “I tried to survive after losing my job, but just couldn’t. Then Geeta didi told me about sex work and got me my first client. I was five months pregnant – and around 25 years old when I began this work,” she says. She continues to feed her daughter while we talk. Honey’s child studies in Class 2 of a private English-medium school that charges Rs 600 a month as fees. In the lockdown era, the child attends her classes online, on Honey’s phone. The same one on which her clients contact her.

“Sex work got me enough to pay for the rent and buy food and medicines. I made around Rs 50,000 a month in the initial period. I was young and beautiful back then. Now I have gained weight,” says Honey, bursting into laughter. “I had thought that I would quit this work after my delivery and look for decent employment, even as a kaamwali (domestic worker) or sweeper. But destiny had other plans for me.

“I was very eager to earn even during my pregnancy because I did not want a fifth miscarriage. I wanted to give the best possible medication and nutrition to my coming child, which is why I accepted clients even in my ninth month of pregnancy. It used to be very painful but I had no other choice. Little did I know this would lead to new complications in my delivery,” says Honey.

"Being sexually active in the last trimester of pregnancy can be hazardous in many ways,” Dr Neelam Singh, a Lucknow-based gynaecologist, told PARI. “She could experience a rupture of the membrane and suffer by contracting a sexually transmitted disease. She might undergo premature labour and the child could also get an STD. And if sexual intercourse often happens in early pregnancy, it could lead to abortion. Most times, women in sex work avoid carrying a child. But if they get pregnant, they continue to work, which could sometimes lead to late and unsafe abortion, risking their reproductive health."

“Once when I went in for a sonography, following unbearable itching and pain,” says Honey, “I got to know that I had an unusual allergy on my thighs, lower abdomen and swelling on the vagina. I felt like killing myself with all that pain and the expenses I knew would follow.” The doctor told her it was a sexually transmitted disease. “But then, one of my clients gave me emotional as well as financial support. I never told the doctor about my profession. That might have been inviting a problem. If she had asked to meet my husband, I would have taken one of my clients to her.

“Thanks to that man, I and my daughter are okay today. He paid half of the bills during my treatment. That is when I decided I could continue with this work,” says Honey.

“Many organisations tell them about the importance of using condoms,” says Kiran Deshmukh, coordinator of the National Network of Sex Workers (NNSW). “However, among sex worker women, abortions are more common than miscarriages. But generally, they go to the government hospital where the doctors also neglect them once they get to know of their profession.”

How do the doctors find out?

“They are gynaecologists,” points out Deshmukh, who is also president of the Veshya Anyay Mukti Parishad (VAMP), based in Sangli, Maharashtra. “Once they ask for their address and learn which locality the women are from, they would figure it out. The women are then given dates [for abortion] that often get postponed. And many a time, the doctor eventually declares that abortion is not possible, saying: ‘you have exceeded four months [of pregnancy] and now it would be illegal to abort’.”

Quite a few of the women simply avoid seeking some kinds of medical help at government hospitals. According to a 2007 report from the United Nations Development Programme's Trafficking and HIV/AIDS project, almost “50 per cent of sex workers [surveyed across nine states] reported not seeking services like ante-natal care and institutional delivery from the public health facilities.” Fear of stigma, attitudes, and urgency in the case of deliveries, seem to be among the reasons for that.

“This profession is directly related to reproductive health,” says Ajeet Singh, founder and director of Gudiya Sanstha, a Varanasi-based organisation that has combated sex trafficking for over 25 years. Singh, who has also worked with organisations helping women in Delhi’s GB Road locality, says that in his experience “75-80 per cent of women in sex work have some or the other reproductive health issues.”

“We have all kind of clients,” says Honey, back in Nangloi Jat. “From MBBS doctors to policemen, students to rickshaw pullers, they all come to us. When younger, we only go with people who pay well, but as our age increases, we stop being choosy. In fact, we need to stay on good terms with these doctors and policemen. You never know when you might need them.”

How much does she earn in a month now?

“If we exclude this lockdown period, I was making around Rs 25,000 a month. But that is an approximate number. Payments differ from client to client, depending on their profession. It also depends on whether we spend the entire night, or just hours (with them),” says Honey. “If we have doubts about the client, we don’t go to hotels with them and call them to our place instead. But in my case, I bring them here to Geeta didi’s

Geeta, who is in her early 40s, is the overseer of sex workers in her area. She is also in the deh vyapar (body business), but mainly makes her living by offering her place to other women and claiming a commission from them. “I bring needy women into this job and when they do not have a place to work, I offer them mine. I take only 50 percent of their income,” says Geeta simply.

“I have seen a lot in my life,” says Honey. “From working at a plastic factory and being thrown out because my husband left me, to now this fungal and vaginal infection I live with and still take medicines for. It seems destined to be with me forever.” These days, her husband is also living with Honey and their daughter.

Does he know about her profession?

“Very well,” says Honey. “He knows it all. Now he has an excuse to depend on me financially. In fact, today, he is going to drop me to the hotel. But my parents [they are a farming family] have no clue about it. And I would never want them to know. They are very old people, living in Haryana.”

“Under the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956, it is an offence for any person above the age of 18 to live off the earnings of a sex worker,” says Aarthi Pai, Pune-based legal adviser to both VAMP and NNSW. “That could include adult children, partner/husband and parents living with a woman in sex work and dependent on her earnings. Such an individual can be punished with imprisonment up to seven years.” But Honey is very unlikely to act against her husband.

“This is the first time I am going to meet any client after the lockdown ended. There have been few, almost none, these days,” she says. “Those who do come to us now, in this pandemic period, mostly can’t be trusted. Earlier, we only had to take precautions to stay clear of HIV and other [sexually transmitted] diseases. Now, there is this corona too. This entire lockdown has been a curse for us. No earnings at all – and all our savings have gone. I could not even get my medicines [anti-fungal creams and lotions] for two months because we could barely afford the food to survive,” says Honey, as she calls out to her husband to bring out his motorbike and drop her at the hotel.

The author reports on public health and civil liberties through an independent journalism grant from the Thakur Family Foundation.

This article was originally published in the People's Archive of Rural India.

Originally posted here: https://ift.tt/3qGMhjs

0 notes

Text

insurance san jose ca

BEST ANSWER: Try this site where you can compare quotes from different companies :4carinsurance.xyz

insurance san jose ca

insurance san jose ca nayi ng mga, data nam ko kasodna nata hindi nayi niya hindi niya. Mga nam paatnaar naar jao hagga paathavit niyyada wata. Naya lalu siya niyad naar saagata niyaso tala (motor vehicle insurance). Pune niyad ko namatnaar yagde. So nyaaan namatnaar oi sao chhavita iyad. It mukta, dajangahnai saapareya (lifestyle, life, etc). Nata sabayo hagga hagga nyagde nai pajar. In saar nayangagga niyad papare hataalit. Naya hajnaar pasa saba hataalpare nyaar. insurance san jose cao i tua nai the law as well as all other parts of the Law to get a refund of any insurance premiums paid. - a car insurance claim has now been resolved because of a collision that happened in the event of a motor car. The car was hit by an uninsured driver and it has now been resolved. The law says drivers of motorcycles had to take a special deduction to the vehicle. The accident happened at the time. The insurance company is required to pay the insurance premium. However the accident was a violation of Section 1 of the law and was of such a nature that it would be against the law for the company to take a case to have a dispute on the basis of a non-committed driver or driver. The insurance company has the right to reject the claim, the company is obligated to pay the premium, but the driver is not allowed to file a claim if the driver was given money. In such a case the. insurance san jose ca.1.38.20 a6.3.4.2.24 a1.3.12.5.6.0.16 a5.27.16.10.2.842.4.6b3.4.2.23.27.66.9.4.2.21.3.32.41A.4.7.7.5.1.8.6.7.11.4A+0.02125.2.3.1.4.4.16.34.3.3.5.2.24.27.67.67.8521.7.10.6A+0.031235.4.2.24.1.43.8.1.741.7.8.8.8.9.43.7A+0.54219.1.5.4.3.25.5.6.2.

Motorcycle Insurance

Motorcycle Insurance: $30K annually. The best place is directly from California. Our online rates are completely free. We work with licensed insurance providers of the highest liability and your personal vehicles. By comparing rates online, we can find the best rate for your vehicle. We can get a cheap car insurance quote and find out whether you can get the best rate with your insurance company by going to www.the.com. All rights reserved. This site is written on behalf of All Rights Reserved. If you find the right car insurance, we’ll provide you with the most reliable and unique car insurance quote to suit your needs. This is part of a larger trend toward a more consumer-focused automotive online experience, and we know which companies will offer you the best quote. It does take a lot of work to find the best quote and policy, but it can be done from many different angles, including comparison shopping, getting an online quote, shopping around and getting the most personalized quotes from.

Watercraft Insurance

Watercraft Insurance You pay $0 for your liability policy, but if you carry your pet s policy, you ll pay more. All insurance products advertised on are underwritten by insurance carriers that have partnered with , LLC. HomeInsurance.com, LLC may receive compensation from an insurer or other intermediary in connection with your engagement with the website and/or the sale of insurance to you. All decisions regarding any insurance products, including approval for coverage, premium, commissions and fees, will be made solely by the insurer underwriting the insurance under the insurer s then-current criteria. All insurance products are governed by the terms, conditions, limitations and exclusions set forth in the applicable insurance policy. Please see a copy of your policy for the full terms, conditions and exclusions. ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, EXPRESS-LIMITATE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR USE ARE NOT AVAIL.

Condo insurance quote

Condo insurance quote will change when a person in the group becomes 18 because some insurance companies offer a new age waiver. The reason for this is for a couple who might be under 18 years old. It is also for a number of reasons. If the older person were to pass away, and they could not get health insurance, they could go on to get a waiver that would lower their premiums down the line. The second reason is the cost. It is true that health insurance is more expensive at age 18 for new men and women. There is a good chance that it will be slightly expensive for women as well. Most insurance providers have online quote form to give more information about premiums for 18 and over. The website has a tool that will tell you how much there is to insure if you want to get an auto insurance quote. If you want a health insurance plan, you will want to get it approved by your health insurance carrier. If you are a long-term health insurance rider you will benefit.

Boat Insurance

Boat Insurance) *Boat insurance is not necessarily available in all states (except Puerto Rico, but BOC is available in all states). However, in cases of any liability insurance, the boat’s owner may need to carry liability coverage on it in order to get it off the lot. BOC offers coverage for boats, ATVs, cruise boats, trucks, and watercraft. This is a common type of boat coverage, as you can also purchase a marine insurance policy. BOC provides an assortment of services and services, including: · BOPs: A series of services designed to provide the necessary physical repairs and other repairs for an insured tank during the cruise. Boat cruisers are the primary carrier. · RV: An optional protection for an RV when the vehicle is not used and not owned by its owner. · RV drivers: Coverage for the costs associated with transporting, caring for, and repairing an RV when it is not in use.

RV Insurance

RV Insurance. We accept all credit cards, mobile devices, and electronic funds transfer. The following card types accept payments: Auto Home Life Transamerica Whately Caldari Amica Pemco Standard auto When you add these six types of coverage together, they count as one continuous type of coverage. You must cancel your car insurance policy at any time and it will be cancelled if you don’t have insurance, under this type of coverage. How El Paso saves on insurance monthly As a self-employed sole proprietor, El Paso is saving money every month by taking a low rate on your insurance policy. When you use any of the discount programs above, you’re saving money for both your home and auto insurance, no matter where you actually live. So, what does that mean for me? I’ve seen as many as ten companies in El Paso, and yet.

Insured Information

Insured Information for California Drivers Under 25. Any outstanding debts or car insurance cancellation will result in a void vehicle insurance. A California’s minimum car insurance limits are currently $30,000 per person and $60,000 per crash for Bodily Injury, $10,000 for Property Damage, and $25,000 for Personal Injury Protection (PIP). The minimum statewide liability limits are $30,000 per person and $60,000 per accident for bodily injury, $15,000 per accident for bodily injury, and $25,000 per property damage. In California, residents must choose a car insurance policy in the amount of collision damage. That’s the minimum state-mandated car insurance you need to be financially responsible if damaged in a wreck. Californians pay nearly $100 billion in car insurance premiums. That’s why Insurance Analysts at is here to help find the best policy to meet your coverage and budgetary needs. Car insurance in California is not automatically.

About Brent Fulk, your San Jose insurance agent.

About Brent Fulk, your San Jose insurance agent. We provide the most comprehensive , , and . Our agents offer all types of coverage, whether you need , , or . We’ve been offering the right insurance solutions to protect the people, businesses and property for decades. We only offer car insurance in Northern California, and we do not have the best prices available elsewhere. We are here to help you get the coverage you need at the right rate. If you find yourself in need of liability insurance, uninsured motorist car insurance, medical payments etc… and you know when you are looking for better deals, we can help. We’re a family-owned independent agency in California. We have been in the insurance sales industry for over 20 years. And we know you are passionate about your business because we believe in making insurance easy. If we can t find one that will. Because we know you all of you have the most interesting questions to ask and we re here to show you some of the information on every type.

0 notes

Text

New world news from Time: How the Pandemic Is Reshaping India

With a white handkerchief covering his mouth and nose, only Rajkumar Prajapati’s tired eyes were visible as he stood in line.

It was before sunrise on Aug. 5, but there were already hundreds of others waiting with him under fluorescent lights at the main railway station in Pune, an industrial city not far from Mumbai, where they had just disembarked from a train. Each person carried something: a cloth bundle, a backpack, a sack of grain. Every face was obscured by a mask, a towel or the edge of a sari. Like Prajapati, most in the line were workers returning to Pune from their families’ villages, where they had fled during the lockdown. Now, with mounting debts, they were back to look for work. When Prajapati got to the front of the line, officials took his details and stamped his hand with ink, signaling the need to self-isolate for seven days.

Atul Loke for TIME

After Prime Minister Narendra Modi appeared on national television on March 24 to announce that India would go under lockdown to fight the coronavirus, Prajapati’s work as a plasterer for hire at construction sites around Pune quickly dried up. By June, his savings had run out and he, his wife and his brother left Pune for their village 942 miles away, where they could tend their family’s land to at least feed themselves. But by August, with their landlord asking for rent and the construction sites of Pune reopening, they had no option but to return to the city. “We might die from corona, but if there is nothing to eat we will die either way,” said Prajapati.

As the sun rose, he walked out of the station into Pune, the most infected city in the most infected state in all of India. As of Aug. 18, India has officially recorded more than 2.7 million cases of COVID-19, putting it third in the world behind the U.S. and Brazil. But India is on track to overtake them both. “I fully expect that at some point, unless things really change course, India will have more cases than any other place in the world,” says Dr. Ashish Jha, director of Harvard’s Global Health Institute. With a population of 1.3 billion, “there is a lot of room for exponential growth.”

Read More: India’s Coronavirus Death Toll Is Surging. Prime Minister Modi Is Easing Lockdown Anyway

The pandemic has already reshaped India beyond imagination. Its economy, which has grown every year for the past 40, was faltering even before the lockdown, and the International Monetary Fund now predicts it will shrink by 4.5% this year. Many of the hundreds of millions of people lifted out of extreme poverty by decades of growth are now at risk in more ways than one. Like Prajapati, large numbers had left their villages in recent years for new opportunities in India’s booming metropolises. But though their labor has propelled their nation to become the world’s fifth largest economy, many have been left destitute by the lockdown. Gaps in India’s welfare system meant millions of internal migrant workers couldn’t get government welfare payments or food. Hundreds died, and many more burned through the meager savings they had built up over years of work.

Now, with India’s economy reopening even as the virus shows no sign of slowing, economists are worried about how fast India can recover—and what happens to the poorest in the meantime. “The best-case scenario is two years of very deep economic decline,” says Jayati Ghosh, chair of the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. “There are at least 100 million people just above the poverty line. All of them will fall below it.”

Atul Loke for TIMERajkumar Prajapati, third from right, gives his family’s details to local officials at the train station in Pune on Aug. 5.

Atul Loke for TIMEThe Tadiwala Chawl area of Pune emerged as a COVID-19 hotspot.

Atul Loke for TIMEWorkers from the Pune Municipal Corporation spray disinfectant in the Tadiwala Chawl area.

In some ways Prajapati, 35, was a lucky man. He has lived and worked in Pune since the age of 16, though like many laborers, he regularly sends money home to his village and returns every year to help with the harvest. Over the years, his remittances have helped his father build a four-room house. When the lockdown began, he even sent his family half of the $132 he had in savings. The $66 Prajapati had left was still more than many had at all, and enough to survive for three weeks. His landlord let him defer his rent payments. Two weeks into the lockdown, when Modi asked citizens in a video message to turn off their lights and light candles for nine minutes at 9 p.m. in a show of national solidarity, Prajapati was enthusiastic, lighting small oil lamps and placing them at shrines in his room and outside his door. “We were very happy to do it,” he said. “We thought that perhaps this will help with corona.”

Other migrant workers weren’t so enthusiastic. For those whose daily wages paid for their evening meals, the lockdown had an immediate and devastating effect. When factories and construction sites closed because of the pandemic, many bosses—who often provide their temporary employees with food and board—threw everyone out onto the streets. And because welfare is administered at a state level in India, migrant workers are ineligible for benefits like food rations anywhere other than in their home state. With no food or money, and with train and bus travel suspended, millions had no choice but to immediately set off on foot for their villages, some hundreds of miles away. By mid-May, 3,000 people had died from COVID-19, but at least 500 more had died from “distress deaths” including those due to hunger, road accidents and lack of access to medical facilities, according to a study by the Delhi-based Society for Social and Economic Research. “It was very clear there had been a complete lack of planning and thought to the implications of switching off the economy for the vast majority of Indian workers,” says Yamini Aiyar, president of the Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi think tank.

One migrant worker who decided to make the risky journey on foot was Tapos Mukhi, 25, who set off from Chiplun, a small town in the western state of Maharashtra, toward his village in the eastern state of Odisha, over 1,230 miles away. He had tried to work through the lockdown, but his boss held back his wages, saying he did not have money to pay him immediately. Mukhi took another job at a construction site in June, but after a month of lifting bricks and sacks of cement, a nail went through his foot, forcing him to take a day off. His supervisor called him lazy and told him to leave without the $140 he was owed. On Aug. 1, he walked for a day in the pouring monsoon rain with his wife and 3-year-old daughter, before a local activist arranged for a car to Pune. “We had traveled so far from our village to work,” said Mukhi, sitting on a bunk bed in a shelter in Pune, where activists from a Pune-based NGO had given him and his family train tickets. “But we didn’t get the money we were owed and we didn’t even get food. We have suffered a lot. Now we never want to leave the village again.”

Although Indian policymakers have long been aware of the extent to which the economy relies on informal migrant labor like Mukhi’s—there are an estimated 40 million people like him who regularly travel within the country for work—the lockdown brought this long invisible class of people into the national spotlight. “Something that caught everyone by surprise is how large our migrant labor force is, and how they fall between all the cracks in the social safety net,” says Arvind Subramanian, Modi’s former chief economic adviser, who left government in 2018. Modi was elected in 2014 after a campaign focused on solving India’s development problems, but under his watch economic growth slid from 8% in 2016 to 5% last year, while flagship projects, like making sure everyone in the country has a bank account, have hit roadblocks. “The truth is, India needs migration very badly,” Subramanian says. “It’s a source of dynamism and an escalator for lots of people to get out of poverty. But if you want to get that income improvement for the poor back, you need to make sure the social safety net works better for them.”

Atul Loke for TIMEA doctor waits for a dose of remdesivir while a nurse attends to a newly admitted COVID-19 patient at Aundh District Hospital in Pune.

Atul Loke for TIMEAfter her condition improved, a COVID-19 patient is helped into a wheelchair so she can be transferred from the intensive-care unit to an observation ward.

Atul Loke for TIMEA young worker dressed in personal protective equipment sweeps the floor of the intensive-care unit.

The wide-scale economic disruption caused by the lockdown has disproportionately affected women. Because 95% of employed women work in India’s informal economy, many lost their jobs, even as the burden remained on them to take care of household responsibilities. Many signed up for India’s rural employment scheme, which guarantees a set number of hours of unskilled manual labor. Others sold jewelry or took on debts to pay for meals. “The COVID situation multiplied the burden on women both as economic earners and as caregivers,” says Ravi Verma of the Delhi-based International Center for Research on Women. “They are the frontline defenders of the family.”

But the rural employment guarantee does not extend to urban areas. In Dharavi, a sprawling slum in Mumbai, Rameela Parmar worked as domestic help in three households before the lockdown. But the families told her to stop coming and held back her pay for the last four months. To support her own family, she was forced to take daily wage work painting earthen pots, breathing fumes that make her feel sick. “People have suffered more because of the lockdown than [because of] corona,” Parmar says. “There is no food and no work—that has hurt people more.”

Girls were hit hard too. For Ashwini Pawar, a bright-eyed 12-year-old, the pandemic meant the end of her childhood. Before the lockdown, she was an eighth-grade student who enjoyed school and wanted to be a teacher someday. But her parents were pushed into debt by months of unemployment, forcing her to join them in looking for daily wage work. “My school is shut right now,” said Pawar, clutching the corner of her shawl under a bridge in Pune where temporary workers come to seek jobs. “But even when it reopens I don’t think I will be able to go back.” She and her 13-year-old sister now spend their days at construction sites lifting bags of sand and bricks. “It’s like we’ve gone back 10 years or more in terms of gender-equality achievements,” says Nitya Rao, a gender and development professor who advises the U.N. on girls’ education.

In an attempt to stop the economic nosedive, Modi shifted his messaging in May. “Corona will remain a part of our lives for a long time,” he said in a televised address. “But at the same time, we cannot allow our lives to be confined only around corona.” He announced a relief package worth $260 billion, about 10% of the country’s GDP. But only a fraction of this came as extra handouts for the poor, with the majority instead devoted to tiding over businesses. In the televised speech announcing the package, Modi spoke repeatedly about making India a self-sufficient economy. It was this that made Prajapati lose hope in ever getting government support. “Modiji said that we have to become self-reliant,” he said, still referring to the Prime Minister with an honorific suffix. “What does that mean? That we can only depend on ourselves. The government has left us all alone.”

By the time the lockdown began to lift in June, Prajapati’s savings had run out. His government ID card listed his village address, so he was not able to access government food rations, and he found himself struggling to buy food for his family. Three times, he visited a public square where a local nonprofit was handing out meals. On June 6, he finally left Pune for his family’s village, Khazurhat. He had been forced to borrow from relatives the $76 for tickets for his wife, brother and himself. But having heard the stories of migrants making deadly journeys back, he was thankful to have found a safe way home.

Atul Loke for TIMEKashinath Kale’s widow, Sangeeta, flanked by her sons Akshay, left, and Avinash, holds a framed portrait of her late husband outside their home in Kalewadi, a suburb of Pune. Kale, 44, died from COVID-19 in July as the family desperately tried to find a hospital bed with a ventilator.

Meanwhile, the virus had been spreading across India, despite the lockdown. The first hot spots were India’s biggest cities. In Pune, Kashinath Kale, 44, was admitted to a public hospital with the virus on July 4, after waiting in line for nearly four hours. Doctors said he needed a bed with a ventilator, but none were available. His family searched in vain for six days, but no hospital could provide one. On July 11, he died in an ambulance on the way to a private hospital, where his family had finally located a bed in an intensive-care unit with a ventilator. “He knew he was going to die,” says Kale’s wife Sangeeta, holding a framed photograph of him. “He was in a lot of pain.”

By June, almost every day saw a new record for daily confirmed cases. And as COVID-19 moved from early hot spots in cities toward rural areas of the country where health care facilities are less well-equipped, public-health experts expressed concern, noting India has only 0.55 hospital beds per 1,000 people, far below Brazil’s 2.15 and the U.S.’s 2.80. “Much of India’s health infrastructure is only in urban areas,” says Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the D.C.-based Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy. “As the pandemic unfolds it is moving into states which have very low levels of testing and rural areas where the public-health infrastructure is weak.”

Read More: India Is the World’s Second-Most Populous Country. Can It Handle the Coronavirus Outbreak?

When he arrived back in his village of Khazurhat, Prajapati’s neighbors were worried he might have been infected in Pune, so medical workers at the district hospital checked his temperature and asked if he had any symptoms. But he was not offered a test. “While testing has been getting better in India, it’s still nowhere near where it needs to be,” says Jha.

Nevertheless, Modi has repeatedly touted India’s low case fatality rate—the number of deaths as a percentage of the number of cases—as proof that India has a handle on the pandemic. (As of Aug. 17 the rate was 1.9%, compared with 3.1% in the U.S.) “The average fatality rate in our country has been quite low compared to the world … and it is a matter of satisfaction that it is constantly decreasing,” Modi said in a televised videoconference on Aug. 11. “This means that our efforts are proving effective.”

Atul Loke for TIMEParents keep their child still while a health care worker takes a nasal swab for a COVID-19 test at a school in Pune.

Atul Loke for TIMEA health care worker executes a rapid antigen COVID-19 test in the local school of Dhole Patil in Pune.

Atul Loke for TIMEA health care worker checks a woman’s temperature and oxygen saturation in the Dhole Patil slum on Aug. 10.

But experts say this language is dangerously misleading. “As long as your case numbers are increasing, your case fatality rate will continue to fall,” Jha says. When the virus is spreading exponentially as it is currently in India, he explains, cases increase sharply but deaths, which lag weeks behind, stay low, skewing the ratio to make it appear that a low percentage are dying. “No serious public-health person believes this is an important statistic.” On the contrary, Jha says, it might give people false optimism, increasing the risk of transmission.

Modi’s move to lock down the country in March was met with a surge in approval ratings; many Indians praised the move as strong and decisive. But while other foreign leaders’ lockdown honeymoons eventually gave way to popular resentment, Modi’s ratings remained stratospheric. In some recent polls, they topped 80%.

The reason has much to do with his wider political project, which critics see as an attempt to turn India from a multifaith constitutional democracy into an authoritarian, Hindu-supremacist state. Since winning re-election with a huge majority in May 2019, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the political wing of a much larger grouping of organizations whose stated mission is to turn India into a Hindu nation, has delivered on several long-held goals that excite its right-wing Hindu base at the expense of the country’s Muslim minority. (Hindus make up 80% of the population and Muslims 14%.) Last year the government revoked the autonomy of India’s only Muslim-majority state, Kashmir. And an opulent new temple is being built in Ayodhya—a site where many Hindus believe the deity Ram was born and where Hindu fundamentalists destroyed a mosque on the site in 1992. After decades of legal wrangling and political pressure from the BJP, in 2019 the Supreme Court finally ruled a temple could be built in its place. On Aug. 5, Modi attended a televised ceremony for the laying of the foundation stone.

Read More: The Battle for India’s Founding Ideals

Still, before the pandemic Modi was facing his most severe challenge yet, in the form of a monthslong nationwide protest movement. All over the country, citizens gathered at universities and public spaces, reading aloud the preamble of the Indian constitution, quoting Mohandas Gandhi and holding aloft the Indian tricolor. The protests began in December 2019 as resistance to a controversial law that would make it harder for Muslim immigrants from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, to gain Indian citizenship. They morphed into a wider pushback against the direction of the country under the BJP. In local Delhi elections in February, the BJP campaigned on a platform of crushing the protests but ended up losing seats. Soon after, riots broke out in the capital; 53 people were killed, 38 of them Muslims. (Hindus were also killed in the violence.) Police failed to intervene to stop Hindu mobs roaming around Muslim neighborhoods looking for people to kill, and in some cases joined mob attacks on Muslims themselves, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

Atul Loke for TIMEWorkers push the body of a COVID-19 patient into the furnace of Yerawada crematorium in Pune on Aug. 11.

“During those hundred days I thought India had changed forever,” says Harsh Mander, a prominent civil-rights activist and director of the Centre for Equity Studies, a Delhi think tank, of the three months of nationwide dissent from December to March. But the lockdown put an abrupt end to the protests. Since then, the government has ramped up its crackdown on dissent. In June, Mander was accused by Delhi police (who report to Modi’s interior minister, Amit Shah) of inciting the Delhi riots; in the charges against him, they quoted out of context portions of a speech he had made in December calling on protesters to continue Gandhi’s legacy of nonviolent resistance, making it sound instead like he was calling on them to be violent. Meanwhile, local BJP politician Kapil Mishra, who was filmed immediately before the riots giving Delhi police an ultimatum to clear the streets of protesters lest his supporters do it themselves, still walks free. “In my farthest imagination I couldn’t believe there would be this sort of repression,” Mander says.

Read More: ‘Hate Is Being Preached Openly Against Us.’ After Delhi Riots, Muslims in India Fear What’s Next

A pattern was emerging. Police have also arrested at least 11 other protest leaders, including Safoora Zargar, a 27-year-old Muslim student activist who organized peaceful protests. She was accused of inciting the Delhi riots and charged with murder under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, a harsh anti-terrorism law that authorities used at least seven times during the lockdown to arrest activists or journalists. The law is described by Amnesty International as a “tool of harassment,” and by Zargar’s lawyer Ritesh Dubey, in an interview with TIME, as aimed at “criminalizing dissent.” As COVID-19 spread around the country, Zargar was kept in jail for two months, without bail, despite being 12 weeks pregnant at the time of her arrest. Restrictions in place to curb the spread of coronavirus, like not allowing lawyers to visit prisons, have also impacted protesters’ access to legal justice, Dubey says.

“The government used this health emergency to crush the largest popular movement this country has seen since independence,” Mander says. “The Indian Muslim has been turned into the enemy within. The economy has tanked, there is mass hunger, infections are rising and rising, but none of that matters. Modi has been forgiven for everything else. This normalization of hate is almost like a drug. In the intoxication of this drug, even hunger seems acceptable.”

Read More: It Was Already Dangerous to Be Muslim in India. Then Came the Coronavirus

Close to going hungry, Prajapati says the Modi administration has provided little relief for people like him. “If we have not gotten anything from the government, not even a sack of rice, then what can we say to them?” he says. “I don’t have any hope from the government.”

Still a change in government would be too much for Prajapati, a devout Hindu and a Modi supporter, who backs the construction of the temple of Ram in Ayodhya and cheered on the BJP when it revoked the autonomy of Kashmir. “There is no one else like Modi who we can put our faith in,” he says. “At least he has done some good things.”

Prajapati remained in Khazurhat from June until August, working his family’s acre of farmland where they grow rice, wheat, potatoes and mustard. But there was little other work available, and the yield from their farm was not sufficient to support the family. Now $267 in debt to employers and relatives, he decided to return to Pune along with his wife and brother. Worried about reports of rising cases in the city, his usually stoic father cried as he waved him off from the village. On his journey, Prajapati carried 44 lb. of wheat and 22 lb. of rice, which he hoped would feed his family until he could find construction work.

On the evening of his return, Prajapati cleaned his home, cooked dinner from what he had carried back from the village, and began calling contractors to look for work. The pandemic had set him back at least a year, he said, and it would take him even longer to pay back the money he owed. The stamp on his hand he’d received at the station, stating that he was to self-quarantine for seven days, had already faded. Prajapati was planning to work as soon as he could. “Whether the lockdown continues or not, whatever happens we have to live here and earn some money,” he said. “We have to find a way to survive.”

—With reporting by Madeline Roache/London

from Blogger https://ift.tt/2EhqkDC via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

With a white handkerchief covering his mouth and nose, only Rajkumar Prajapati’s tired eyes were visible as he stood in line.

It was before sunrise on Aug. 5, but there were already hundreds of others waiting with him under fluorescent lights at the main railway station in Pune, an industrial city not far from Mumbai, where they had just disembarked from a train. Each person carried something: a cloth bundle, a backpack, a sack of grain. Every face was obscured by a mask, a towel or the edge of a sari. Like Prajapati, most in the line were workers returning to Pune from their families’ villages, where they had fled during the lockdown. Now, with mounting debts, they were back to look for work. When Prajapati got to the front of the line, officials took his details and stamped his hand with ink, signaling the need to self-isolate for seven days.

Atul Loke for TIME

After Prime Minister Narendra Modi appeared on national television on March 24 to announce that India would go under lockdown to fight the coronavirus, Prajapati’s work as a plasterer for hire at construction sites around Pune quickly dried up. By June, his savings had run out and he, his wife and his brother left Pune for their village 942 miles away, where they could tend their family’s land to at least feed themselves. But by August, with their landlord asking for rent and the construction sites of Pune reopening, they had no option but to return to the city. “We might die from corona, but if there is nothing to eat we will die either way,” said Prajapati.

As the sun rose, he walked out of the station into Pune, the most infected city in the most infected state in all of India. As of Aug. 18, India has officially recorded more than 2.7 million cases of COVID-19, putting it third in the world behind the U.S. and Brazil. But India is on track to overtake them both. “I fully expect that at some point, unless things really change course, India will have more cases than any other place in the world,” says Dr. Ashish Jha, director of Harvard’s Global Health Institute. With a population of 1.3 billion, “there is a lot of room for exponential growth.”

Read More: India’s Coronavirus Death Toll Is Surging. Prime Minister Modi Is Easing Lockdown Anyway

The pandemic has already reshaped India beyond imagination. Its economy, which has grown every year for the past 40, was faltering even before the lockdown, and the International Monetary Fund now predicts it will shrink by 4.5% this year. Many of the hundreds of millions of people lifted out of extreme poverty by decades of growth are now at risk in more ways than one. Like Prajapati, large numbers had left their villages in recent years for new opportunities in India’s booming metropolises. But though their labor has propelled their nation to become the world’s fifth largest economy, many have been left destitute by the lockdown. Gaps in India’s welfare system meant millions of internal migrant workers couldn’t get government welfare payments or food. Hundreds died, and many more burned through the meager savings they had built up over years of work.

Now, with India’s economy reopening even as the virus shows no sign of slowing, economists are worried about how fast India can recover—and what happens to the poorest in the meantime. “The best-case scenario is two years of very deep economic decline,” says Jayati Ghosh, chair of the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. “There are at least 100 million people just above the poverty line. All of them will fall below it.”