#north cornwall

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gallos

This 8-foot-tall (2.4 m) bronze sculpture by Rubin Eynon is located at Tintagel Castle, a mediaeval fortification located on the peninsula of Tintagel Island adjacent to the village of Tintagel (Trevena), North Cornwall.

It’s a representation of a ghostly male figure wearing a crown and holding a sword. While it’s popularly known as the "King Arthur statue", the site's owner English Heritage, has stated that it isn’t meant to represent a single person, but instead reflects the general history of the site, which is likely to have been a summer residence for the kings of Dumnonia between the late 4th and late 8th centuries (ie between the end of Roman rule in Britain and the Anglo-Saxon period).

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunset in Bude. In sequence

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some pictures downloaded from my Pentax Bridge camera, taken over the last few days in North Cornwall #pentax #pentaxbridge #northcornwallcoast

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Libraries Around the World: Cornwall, Canada

Cornwall Public Library

#libraries#librarylife#libraryland#prince edward island#canada#public libraries#libraries around the world#around the world#north america#cornwall

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

personally, i think scotland and wales should be able to kyoshi island themselves. just drift off into the ocean so they don't have to deal with us shits

#cornwall too although i'm not sure everyone there is cool enough to be down for that#big fan of kicking england out of the UK to get The Cooler UK That's Not Actually A Kingdom#i'd love to ask wales and scotland to take the north with them#but after everything we've done to wales i don't think we deserve it#uk politics

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

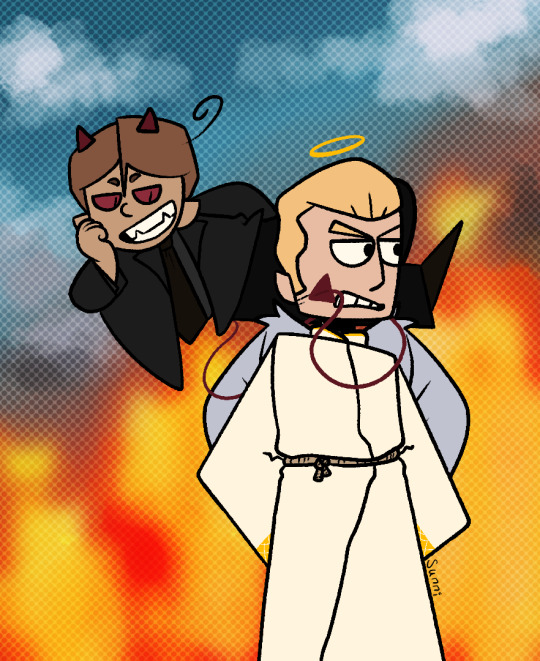

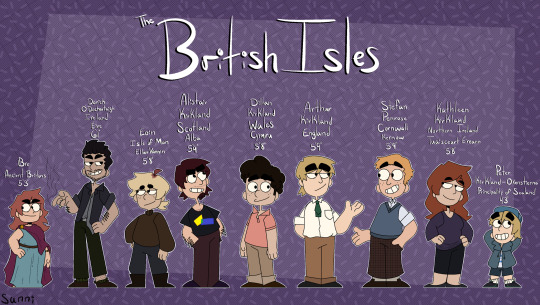

Various art shit, you’re welcome babes ❤️

1) Im a sucker for demon Vene rather than angel Vene, also obvious good omens inspired lmao

2) I looooooove the idea of Germany having a mini schnauzer! I did a poll on my other blog and the name Pretzel won! I based her personality on the mini schnauzer I had, Sir Lewis. Talkative, very loyal, a massive cuddler, abandonment and anxiety issues. I think Germany adopted her from a (verified) show dog breeder for the purpose of going on different kinds of hunts with him and Prussia, but in the long run it didn’t work out because Germany may have neglected to train her properly and spoiled her far more than he meant to. So her job is exactly like the other three dogs; a cuddly lap dog.

3) Not many notes here. Just transmasc Romano and I think Romano got a perm in the past as an attempt to bring back his once VERY curly hair because he honestly missed it. He gave up in the 90s lol

4) Redrew the old line up for the British Isles family! Very slight redesigns too! I think the canon uk bros designs are nice but also idc, I’ll draw these uk bros all the time instead 👀

#hetalia#hetalia fanart#hetalia ocs#hetalia headcanons#hws romano#hws south italy#hws veneziano#hws north italy#hws germany#hws england#hws british isles#hws ancient britons#hws ireland#hws northern ireland#hws cornwall#hws wales#hws scotland#hws isle of man#hws sealand

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polly Joke, North Cornwall, England by Chris Marshall

#england#uk#nature#landscape#sea#coast#wild flowers#flowers#red flowers#yellow flowers#beautiful#petitworld favs#petitworld

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

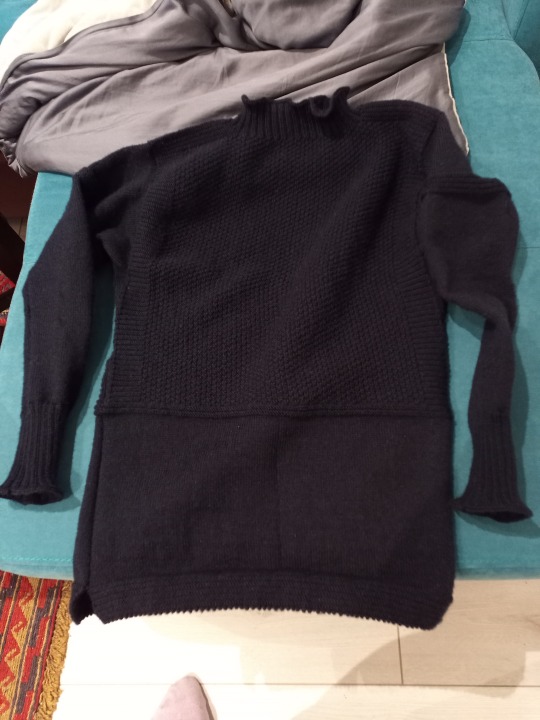

Gansey Nerdery

Ganseys are actually a really clever piece of knitwear, okay? And I feel they deserve extra love.

Here is a Gansey:

Please excuse the crap photo, it's because it's one I knitted myself. They are traditional fishermen's jumpers that are designed to be warm, hard-wearing, and close-fitting enough not to be at risk of entanglement when using machinery.

While you can get fully-patterned Ganseys, most of them are half-patterned like this one. This is because most holes happen in the lower part of the sleeves and body, and plain stocking stitch is easier to mend.

The knobbly-bobbly edge is because I used a Channel Islands cast-on, which is traditional for Ganseys from Guernsey (which is where they get their name from), but not something you see as much with the variants from Cornwall, North-East England or Scotland (which are all Gansey hotspots). This particular Gansey is otherwise mainly Scarborough pattern, although the banding on the sleeves is more commonly a Cornish thing.

Ganseys are reversible, as there's no difference in the front and back, which spreads wear and helps avoid elbow holes.

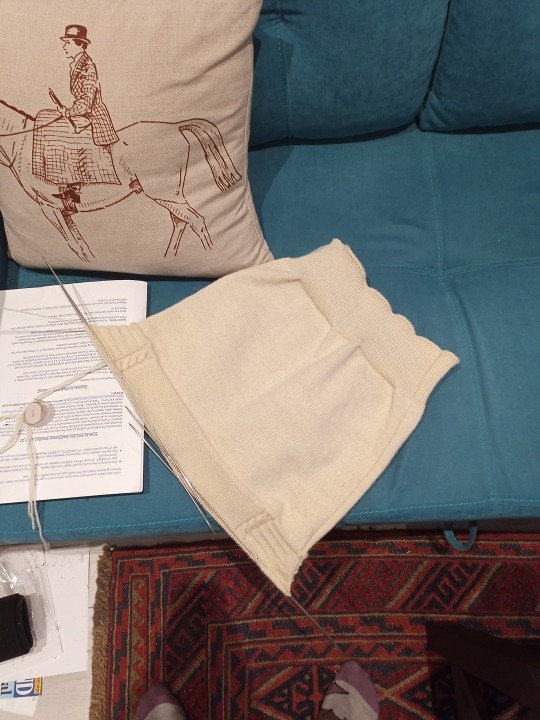

They also don't have seams, as such, as traditionally they're knitted in the round as one piece. Like so:

There are 'false seams' up the sides, which are just purl stitches that help you keep your place in the pattern without needing stitch markers etc. when you're in the stocking stitch section. There are also grafts at the shoulders, and you pick stitches up around the armholes for the sleeves, which obviously does make a join, but there's no sewing required as sewn seams are inherent weak points.

Another thing Ganseys have to avoid weak points that might result in holes developing is sleeve gussets. They look like this:

You can also do a double gusset, by carrying on the false seam up the middle of the gusset as well, rather than just around the edges, which I did on the navy one, but alas I don't have any pics as it's currently packed away in a box somewhere and I'm not willing to go digging for it, so you only get to see the single version.

The gusset is knitted halfway as part of the body, then put on a spare needle or stitch-holder while the upper body gets knitted as front and back separately (you can apparently also knit the top part in the round and then cut the armholes, but cutting knitwear scares me), then the second half is knitted as part of the sleeve:

The false seam continues down the sleeve, which then gives a nice reference point for where to put thumbholes, if desired. It's very easy - you just switch to knitting back and forth for about 1.5"-2" before returning to knitting in the round.

The collar also has gussets, which helps it stand up. Those involve picking up progressively more stitches either side of the shoulder graft while knitting back and forth for a few rows, before you can pick up the rest of your collar stitches and do some nice ribbing. You can do this before or after the sleeves, as you prefer.

I don't seem to have a picture of it with both sleeves in situ, but yes, the cream one absolutely was a copy of James Fitzjames' Gansey from The Terror. If you're looking for a sign to make one yourself, do it - it's fun!

As a closing note, I wanted to talk about yarn. Ganseys are traditionally done in pure wool 5-ply, which is sort of between 4-ply and DK in terms of weight (broadly equivalent to most sports-weight yarns if you're either unable to get Gansey/Guernsey yarn or prefer a different fibre content) and very tightly plied. This, paired with the thinness of the knitting pins (aka double-pointed needles, usually between 2mm-2.75mm), gives a very tightly-knitted garment that is pretty windproof, as well as being water resistant and still warm when wet. Hence very suitable for both fishing and polar exploration. You could do them in oiled wool for even more waterproofing if you wanted, but I have no idea where to get pre-oiled yarn or how to oil it yourself, and honestly I can't imagine it would be necessary in most modern circumstances.

Unless you actually intend on exploring polar regions, in which case you could probably use all the weather-proofing you can get!

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

Golden hour at Bossiney, North Cornwall.

638 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'all heard of the Tudor Rose, right...?

"The Tudor rose takes its name and origins from the House of Tudor, which united the House of Lancaster and the House of York. The Tudor rose consists of five white inner petals, representing the House of York, and five red outer petals to represent the House of Lancaster."

I agree though, we need to be heard by the seat of power in the South. Perhaps we can talk to these guys and get them to help out:

...some kind of flanking or pincer move perhaps?

No more war of roses we must unite against the south so instead of the red rose or a white rose May I propose a new symbol

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fistral beach

The north coast of Cornwall,

England

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Travel back [...] a few hundred years to before the industrial revolution, and the wildlife of Britain and Ireland looks very different indeed.

Take orcas: while there are now less than ten left in Britain’s only permanent (and non-breeding) resident population, around 250 years ago the English [...] naturalist John Wallis gave this extraordinary account of a mass stranding of orcas on the north Northumberland coast [...]. If this record is reliable, then more orcas were stranded on this beach south of the Farne Islands on one day in 1734 than are probably ever present in British and Irish waters today. [...]

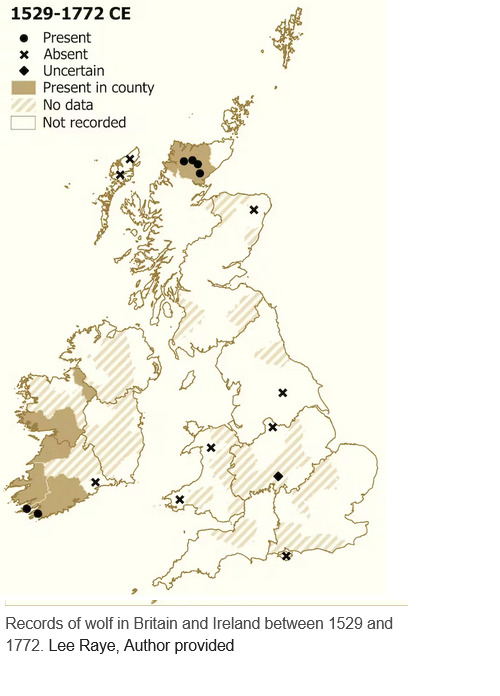

Other careful naturalists from this period observed orcas around the coasts of Cornwall, Norfolk and Suffolk. I have spent the last five years tracking down more than 10,000 records of wildlife recorded between 1529 and 1772 by naturalists, travellers, historians and antiquarians throughout Britain and Ireland, in order to reevaluate the prevalence and habits of more than 150 species [...].

In the early modern period, wolves, beavers and probably some lynxes still survived in regions of Scotland and Ireland. By this point, wolves in particular seem to have become re-imagined as monsters [...].

Elsewhere in Scotland, the now globally extinct great auk could still be found on islands in the Outer Hebrides. Looking a bit like a penguin but most closely related to the razorbill, the great auk’s vulnerability is highlighted by writer Martin Martin while mapping St Kilda in 1697 [...].

[A]nd pine martens and “Scottish” wildcats were also found in England and Wales. Fishers caught burbot and sturgeon in both rivers and at sea, [...] as well as now-scarce fishes such as the angelshark, halibut and common skate. Threatened molluscs like the freshwater pearl mussel and oyster were also far more widespread. [...]

Predators such as wolves that interfered with human happiness were ruthlessly hunted. Authors such as Robert Sibbald, in his natural history of Scotland (1684), are aware and indeed pleased that several species of wolf have gone extinct:

There must be a divine kindness directed towards our homeland, because most of our animals have a use for human life. We also lack those wild and savage ones of other regions. Wolves were common once upon a time, and even bears are spoken of among the Scottish, but time extinguished the genera and they are extirpated from the island.

The wolf was of no use for food and medicine and did no service for humans, so its extinction could be celebrated as an achievement towards the creation of a more civilised world. Around 30 natural history sources written between the 16th and 18th centuries remark on the absence of the wolf from England, Wales and much of Scotland. [...]

In Pococke’s 1760 Tour of Scotland, he describes being told about a wild species of cat – which seems, incredibly, to be a lynx – still living in the old county of Kirkcudbrightshire in the south-west of Scotland. Much of Pococke’s description of this cat is tied up with its persecution, apparently including an extra cost that the fox-hunter charges for killing lynxes:

They have also a wild cat three times as big as the common cat. [...] It is said they will attack a man who would attempt to take their young one [...]. The country pays about £20 a year to a person who is obliged to come and destroy the foxes when they send to him. [...]

The capercaillie is another example of a species whose decline was correctly recognised by early modern writers. Today, this large turkey-like bird [...] is found only rarely in the north of Scotland, but 250–500 years ago it was recorded in the west of Ireland as well as a swathe of Scotland north of the central belt. [...] Charles Smith, the prolific Dublin-based author who had theorised about the decline of herring on the coast of County Down, also recorded the capercaillie in County Cork in the south of Ireland, but noted: This bird is not found in England and now rarely in Ireland, since our woods have been destroyed. [...] Despite being protected by law in Scotland from 1621 and in Ireland 90 years later, the capercaillie went extinct in both countries in the 18th century [...].

---

Images, captions, and all text above by: Lee Raye. “Wildlife wonders of Britain and Ireland before the industrial revolution – my research reveals all the biodiversity we’ve lost.” The Conversation. 17 July 2023. [Map by Lee Raye. Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

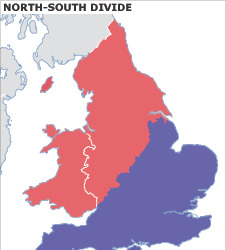

England doesn’t have a North-South divide. But if it did have one, Cornwall would be in the North.

Now I’m not saying there isn’t a big geographical divide between like, Manchester and Canterbury, or that the country’s a homogeneous patchwork, what I’m saying is this divide isn’t north-south and thinking about it as such masks a lot of things.

Oh, and I am, for necessity of discussing this divide, going to be ignoring the Midlands. I hope you forgive me ignoring the deep cultural ties between Birmingham and Rutland.

Map Men made a video about the North-South divide in England (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ENeCYwms-Cc&ab_channel=JayForeman), which focused on the line determined by Danny Dorling in 2008.

… Which isn’t a north-south divide. It’s a northwest-southeast divide, going up at more than 45 degrees – it’s more an east-west divide than it is a north-south. It also includes Wales in “the North” but we’ll get to that.

But it was a north-south divide he set out to find, so a north-south divide he sort of drew, excluding exclaves and enclaves where the metrics he was looking at would make that not a north-south divide.

Notably, several would seem to put the west country peninsula in “the North”… So what’s up with that?

(Dorling's full paper is here, and I recommend looking through the whole thing to see how he arrived at the divide he eventually concluded: https://www.dannydorling.org/wp-content/files/dannydorling_publication_id2938.pdf)

Anyway. This is what’s up with that:

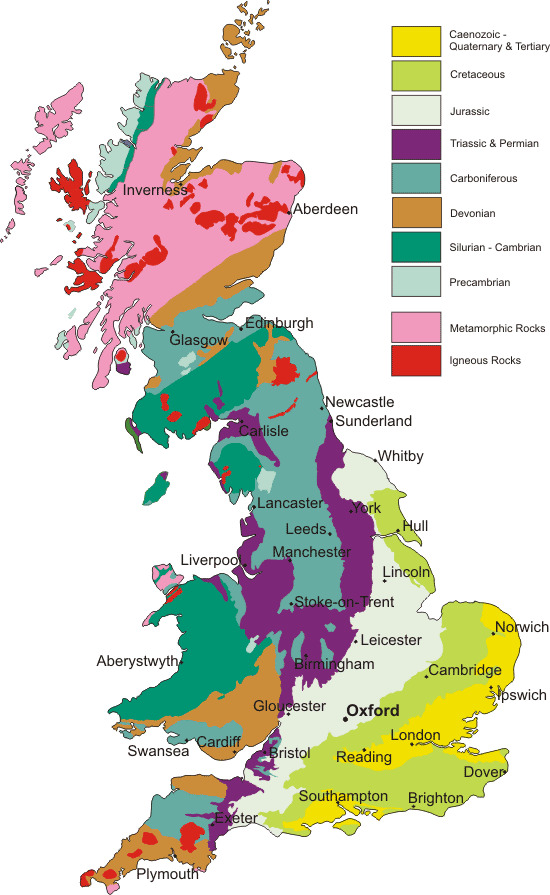

This is a geological map of Great Britain (and the Isle of Man, which isn’t actually part of the UK or any of its constituent countries but I guess it’s here anyway.)

Here again, in the boundary between Jurassic and Triassic geology, is that diagonal line from the Humber to the Severn, but continuing past both. For convenience, here are those two lines superimposed on one another.

With Danny Dorling’s line (frequently following county boundaries or other administrative boundaries) in blue, and the geological divide in red.

One line was drawn in 2008, the other has existed over 200 million years.

This isn’t a coincidence – it’s the reason for the divide.

What made “the North” is the industrial revolution. And one thing that drove the industrial revolution was the mines: coal, iron, silver, tin, the rocks beneath our feet and the people who dreamed they were worth more than the people they sent into the dark to bring it into the light.

Towns grew around mines, from Walker to South Crofty, and more than just the mines defining them, it was the mines closing that would cement the divide.

“Byker Hill and Walker Shore, collier lads forever more”

“Cornish lads are fishermen and Cornish lads are miners too”

- Two folk songs about regional identity’s roots in its industry, from opposite ends of this dividing line

In the West Midlands, the Black Country didn’t earn that name with caviar; it, like Manchester and Leeds, reinvented itself when the industry collapsed: cities built in the brick ruins of the temples built to the exploitation of the workers, blackened by the smokes of the cremation of its labour industry. When the light catches the steel and glass just right, you can still see the ghosts.

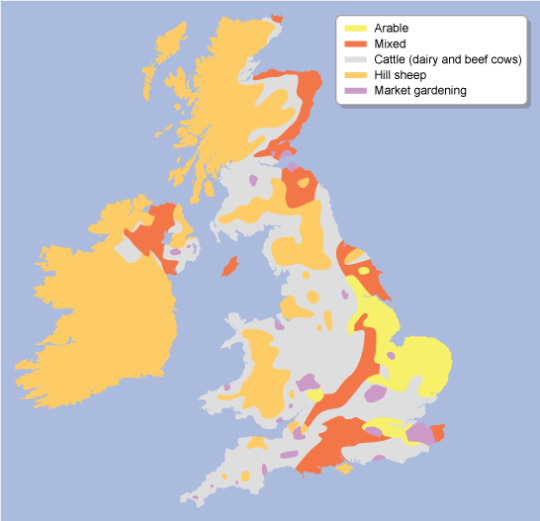

Even the country life outside the cities is shaped by this geology: the terrain north-west of this line doesn’t lend itself to large, flat expanses of land for arable farming, and the divide is visible again when looking at agriculture:

With the majority of land south of the Jurassic-Triassic line being arable, mixed and market gardening, with a fair amount of cattle in the Cotswolds and Chilterns and along the north side of the Thames, and the majority north-west of it being cattle and sheep – which are almost absent from the south side of the divide with the exception of the Isle of Wight and therefore, ironically, Cowes.

Not all farming is the same, the yearly flow of labour and of marketable goods between livestock and arable having little in common beyond being intensive work out-of-doors and taking huge amounts of land to accomplish.

But one thing that also goes hand in hand with this is that sheep aren’t mostly farmed for their meat but for their wool, and what drove industrialisation in the Pennines was the steam-loom: the mechanisation and mass-production of wool.

(Incidentally, on this map arable farming and market gardening also correlate with several types of English traditional dance: Molly, Border an East Midlands and East Riding plough dances, which began as a way for seasonal farmhands to make ends meet by busking with menaces in the winter off-season, but that’s for a later Morris ramble).

But hang on, that puts Hull on the same side of the divide as Kent, not, for example, Liverpool. So what gives there?

The East Riding isn’t built on mining - a kid with a bucket and spade could find the water table in most of the county.

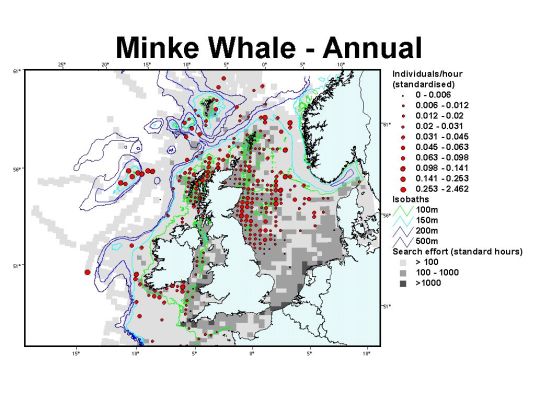

Hull, and other ports of Yorkshire with it, was built on whaling – and not many industries have collapsed harder than whaling. For once, the geography of the land has little impact on this, but the geography of the sea does:

Between England and the European continent is a shallower stretch of sea called Dogger Bank – named for the Dutch cod-fishing boats known as Doggers which fished on it. But shallow water isn’t great for whales. So where is there water good for whales?

Well, whalers from Great Britain would venture as far as the Antarctic ocean in search of whales, and often hunted off Greenland – but there was water closer to home where whales did and still do frequent:

(There is still whaling in the North Sea. Around 500 minke whales are killed by Norwegian whalers each year “in objection to” the global ban on commercial whaling.)

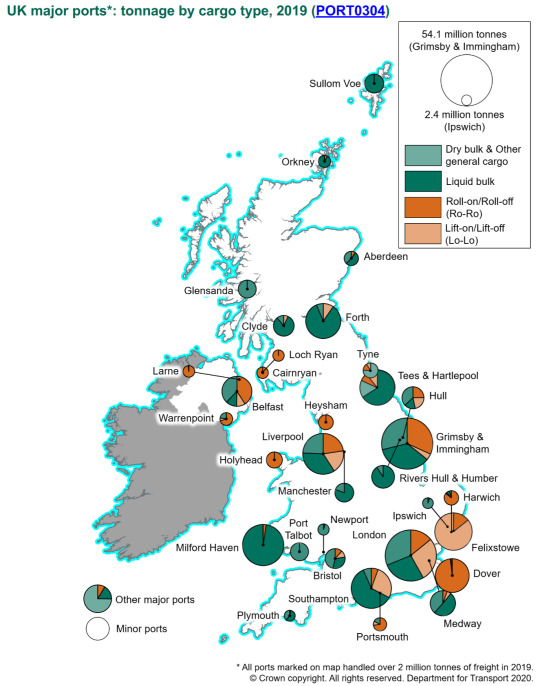

Outside of this, there’s also a divide between port cities dealing primarily in cargo or primarily in passengers, something which is somewhat evening out by one means or another, but here’s a current map of UK passenger ports and their passenger numbers:

Or at least circles sized to correspond to their passenger numbers - source with stats: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sea-passenger-statistics-all-routes-2021/sea-passenger-statistics-all-routes-2021

Compare this with a map of cargo ports by load:

Source with numbers: https://safety4sea.com/uk-ports-record-steady-performance-during-2018/

Generally showing passenger numbers getting lower the further you get from Dover, but not the same correlation with cargo (Plymouth and Holyhead both bucking this trend at a glance).

So, if not “The North” and “The South”, what name does make sense for this divide?

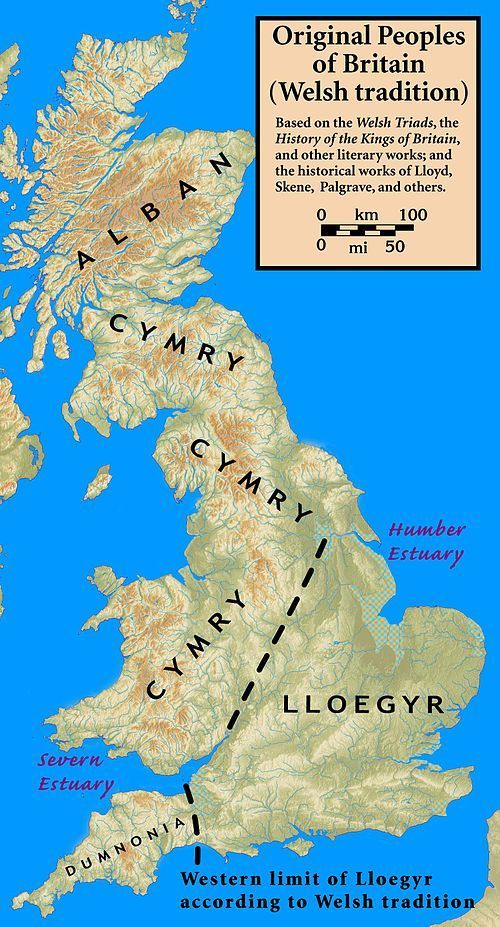

I propose “the South” be known as Lloegyr.

These names still exist: Domnonea still exists in Brittany both as a name for that same region from which Brittonic settlers came to Brittany and an area of Brittany named for them, and in Welsh, yr Alban is Scotland, Cymru is Wales and Lloegr is England.

Wales isn’t part of “the North”. “The North” is part of Wales.

271 notes

·

View notes