#ngola

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ÚNICA MALTA - CORRÓ BEM ft DJ FLAVIO NGOLA

ÚNICA MALTA – CORRÓ BEM ft DJ FLAVIO NGOLA SITE PARA BAIXAR MÚSICAS MP3 , SONG FREE 2025

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Njinga was born into the royal family of Ndongo (now Angola), in west Africa, in 1582. From the age of twenty, Njinga led a group of rebels against the Portuguese invasion of the region. They were elected Ngola (ruler) in 1624, and described by Portuguese colonists as “the most powerful adversary that has ever existed in Africa”.

Njinga modelled themself on the mythic leader Tembo a Ndumbo. Tembo, like Njinga, was assigned female at birth, but underwent rituals to turn them into a man and warrior. Njinga did the same.

Njinga is now recognised as a national hero in Angola, and is commemorated with a statue (pictured) in the capital, Luanda. They are remembered by many communities of African descent around the world for fighting for their nation’s independence.

Check out our podcast on Njinga to learn more!

#black history month#njinga of ndongo and mtamba#njinga#nzinga#black history#queer history#gender#angola#angolan history#african history

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free Coloring Pages inspired by the warrior Queen Nzinga of Matamba & Ngola which is present day Angola 🇦🇴.

A PDF copy of these coloring sheets are available on my Gumroad page!

If you color any of my pages, please tag me. I would to see your creativity!

#freebies#free printable#black coloring pages#juneteenth coloring#juneteenth#black coloring books#black women#african#african history#angola#african america history#black history art#black tumblr#blacklivesmatter#black positivity#african queen#historical fashion#historical art#june 2024#juneteenth2024#gumroad#free coloring pages

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

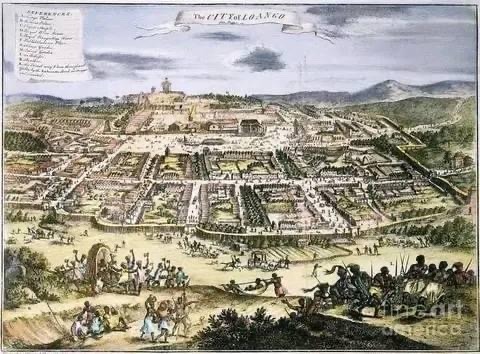

Portuguese Angola

Portuguese Angola in southwest Africa was the first European colony on that continent. While settlement from 1571 proved problematic in the interior, the Portuguese did obtain a large number of slaves which they shipped to their Atlantic island colonies and to Portuguese Brazil right up to the end of the Atlantic slave trade in the 19th century.

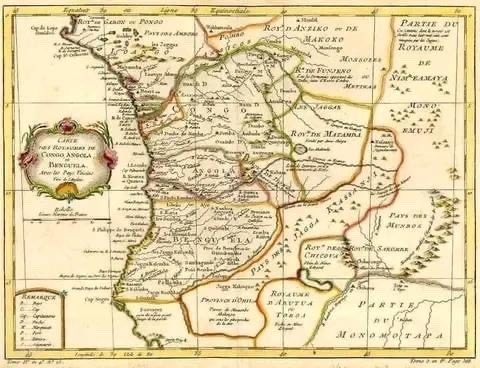

With the capital at Luanda on the coast, the Portuguese struggled against the kingdoms of Kongo, Ndongo, and Matamba to gain control of the interior. The Angolan Wars saw shifting tribal allegiances thwart the relatively small number of Afro-Portuguese, but help from Brazil, eager to maintain the flow of slaves, proved crucial. The decolonization process in the mid-20th century was one of the most bloody and shambolic in Africa, and civil war continued long after independence was gained in 1975.

The Portuguese in West Africa

The Portuguese arrived in West Africa, and from the late 15th century they began to explore further south. Following the Portuguese colonization of São Tomé and Principe in 1486, the Europeans were looking for slaves to work on their sugar plantations. The Portuguese settlers on São Tomé and Principe had already been in trade contact with the mainland, searching for gold, pepper, and ivory. The main trading partner was the Kingdom of Kongo (c. 1400 - c. 1700), which controlled a booming regional slave trade. Through the 16th century, slaves from Kongo (and also the Kingdom of Benin) were transported to the Portuguese islands and to their colonies in the North Atlantic like Madeira.

The Portuguese had bought African slaves with cotton cloth, silk, mirrors, knives, and glass beads, but they got the idea to launch their own slave-capturing expeditions in Africa’s interior and cut out the Kongolese middlemen. The Kongo kings were not pleased with this development, and they were increasingly alarmed at the effects of European culture and the Christian religion on their subjects. As relations soured, the Portuguese began to look for another trade partner further down the coast of Africa.

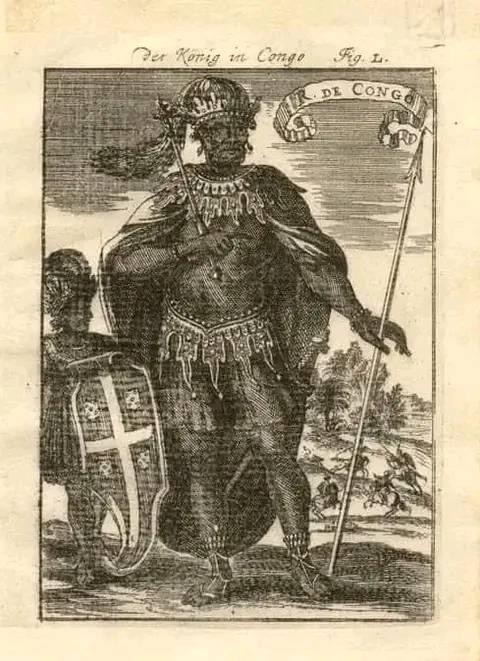

Exploring further south in the mid-16th century, the Europeans came into contact with a new kingdom, or rather a loose confederation of Kimbundu tribes, then known as Ndongo, probably formed c. 1500. Its ruler was called the Ngolo, which derives from the local word for iron - ngola - and from which the name Angola derives. The Portuguese attempted to create a new slave industry partnership with Ndongo and even involved the kingdom in a war with their northern neighbours, the Kingdom of Kongo. Ndongo had already defeated Kongo in a battle in 1556 and so seemed a good candidate to satisfy Portugal's ambitions in the region.

Continue reading...

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imbokodo #3 by Thabo Rametsi, Thabiso Mabanna and Katlego Motaung. Cover by Motaung. Out in January 2025.

"Lieutenant Manthatisi, the Nameless Warrior, and a team of Imboko join Chief Moshe and set sail for Thaba N'chu. With war on the horizon, and the land teeming with refugees, will they find answers to the missing girls? Are Emperor Mbande and the Ngola behind the carnage and kidnapping-or are there other forces at play?"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

New art in my shop

Inspired by a portrait of Queen Nzinga. She way the 17th century Ambundu ruler of the Ndongo and Matamba kingdoms in what is now Northern Angola 🇦🇴.

Highly educated and skilled with a battle ax, Ana I Nzinga was born into the Ndongo kingdom to the Ngola, Kilambo and his favorite concubine, Kengela ka Nkombe. She had 2 sisters, Makambu Mbandi (Barbara) and Funji (Grace)and a brother, Mbandi

She was also an ambassador to the Portuguese empire. Once she assumed power over the kingdom after her brother’s death the Portuguese invaded and drove here into exile and depleting her forces.

She married a Imbangala (mercenary) warlord and used him the build up her forces. She and her people ( with help from the Dutch) then proceeded to regain much of the lost kingdoms. Then it went back and forth for awhile. The Dutch eventually pulling out. The fighting only stopped when a peace treaty was signed.

During peacetime Nzinga allowed the women in her ear band to have kids, have former slaves land, abolished concubinage, (she married her favorite in a Christian ceremony) no longer tolerated meritocracy and democratic policies. And she dominated the slave trade.

She died of an infection without surviving children as her son was murdered by her brother who also had her sterilized. Her sister Barbara took over

#African woman#queen#my art#myart#my artwork#painting#traditional art#black woman#Nzinga#Angola#artists on tumblr#Ndongo#Matamba#Ambundu#portrait#black history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The real Revolution is the Revolution (expansion, ascension) of Consciousness.

#Sagrada Ngola

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The entire African continent was an extremely civilized place by their own rich cultures, the time the first European travellers began discovering and later destroying her people and cultures.

“When they arrived in the Gulf of Guinea and landed at Vaida (in West Africa) the captains were astonished to find streets well laid out, bordered on either side for several leagues by two rows of trees; for days they travelled through a country of magnificent fields, inhabited by men clad in richly coloured garments of their own weaving! Further south in the Kingdom of the Congo, a swarming crowd dressed in `silk` and `velvet`; great States well-ordered, and down to the most minute details; powerful rulers, flourishing industries-civilized to the marrow of their bones. And the condition of the countries on the eastern coast- Mozambique, for example- was quite the same.”Leo Frobenius, `Histoire de la Civilisation Africaine`, quoted in Anna Melissa Graves, `Africa, the Wonder and the Glory,US, Black Classic Press, (originally 1942),pg4.

Portuguese missionaries wrote of the Kongo…” a well-organized political system with taxes and rates, there was a brilliant court,(and) a great civil service. The state constructed roads, imposed tolls, supported a large army and had a monetary system-of…shells, of which the Mani Congo…had a monopoly. The Congo Kingdom even had a few satellite states, for example the state of the Ngola (ie Ndongo) in present-day Angola. The original kingdom was about the size of France and Germany put together”.

“There is no doubting…the existence of an expert metallurgical art in the ancient Kongo; only the competition of objects from abroad and the slow deterioration brought about its decline. A further proof is provided by recent ethnographic documents. The Bakongo were aware of the toxicity of lead vapours. They devised preventative and curative methods, both pharmacological (massive doses of pawpaw and palm oil) and mechanical (exerting of pressure).

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oeri trram rolun pxeioangtsyìpit alu "mouse/mawsì" nì'Ìnglisì oeyä kelkumì. Tsole'a nì'aw ioangtsyìpit a taryul rawngkxamlä alunta fwa pxeioangìl tolok fìtsengit loloho oeru. – Yesterday I found 3 mice in my home. I was very suprised to find so many since two nights ago I only saw one run in through the door.

Tolul kxamlä rawng a pumìri rilvängun fya'ot ahusan kxamlä kelkuä aykemyo, ha tsantxäl silvängi aylaru fte livang. Ayfol rolun fya'oti kuma tsantxängäl silvi ayeylanur. – Perhaps the one that got in found an opening in my house somewhere and called their friends to come, too, which means they may have left a trail (ugh).

Oe nolongspe' sì spole'e nì'i'a framawsì fa oeri mesokx a yolemstokx mehawntsokx kezemplltxe fte tìhawnu säpivi. (Aymawsìri txo 'ivampi fu frivìp fkeyä ta'lengit, tsakrr tsängun 'eykivefu fkoti spxin taluna mawsì tsun hivena txumnga'a ioangtsyìpit akusawngar alu nì'Ìnglìsì "virus"). Ha, aytìftia kìfkeyä mowar si fura fko tìhawnu si sì laro si fkori mesokx akrrmaw tìnusongspe'. – I caught all 3 of them with my hands (wearing gloves then washing my hands of course since mice can carry viruses so its advised to minimize direct contact w them in case they touch or bite you).

Pxemawsìri oel ngola' pxefoti mì tsawla sähena fte ftivanglen tìhusifwot fkeyä. Oel txopu soleyki pxefoti akum oel nerongspe' nìftxan letsaktap. Ha, oel yomtolìng ayrina'ti sì payti fte 'eykivefu maywey pxefoti. – I kept all of them in a tall plastic bin so they couldnt jump out. I probably scared them alot, so I fed them nuts and gave them a little water to calm 'em down.

Oe harmawl hawngkrr kä tìkangkemne tsarewon, ha ke lu krr oeru fpi lonu pxefoti. Krra oe hu hena a oel yolem pxefoti nemfa nì'i'a holum kelkuru ulte polähem tsengur atìkusangkemro, oeyä lefngap pa'limì olì'awn tsa'u.. – Since I had to work that morning and was running late, I didnt have time to find a place to release them, so i left the container with them in it in my car when i got to work.

Pxemawsìri lamu txantompa atxur slä oeti keftxo 'eykefu fula spawne'ea pxefo tok wrrpa hrh. Txantxompa slarmu meyp nìftxan kuma oeru lolu skom a tìsteftxaw si pxefeyä tìfkeytokur. Pxefori 'olefatsu mawey ulte yolom ayrina' a oel yolomtìng pxefoti. Siltsan. Henanemfa lolängu fahew aonvä' nìtxan hrh. – The weather outside was very stormy and i felt bad for them again, lol, so i waited until the rain let up to check on them. They seemed calm and were eating the nuts i gave them. Good. The container smelled tho lol.

Mawkrra tìkangkem soli, oel lolonu pxefoti pxaw tìkusätenga txayo alu "park" nì'Ìnglìsì, ulte pxefo holum nìfya'o spä . – After work, I released them in a nearby park and they hopped away.

---

Lit. Translation - Regarding me, yesterday found two little animals called mouse English-ly my home in. [i] saw only 2 animals that were running [the] doorway through, so [the] 3 animals were being at here was suprising to me.

Ran through [the] door that one regarding [it], found [perhaps] a hiding path through my home's walls, so [perhaps] it invited [disparagement] their friends in order to explore. They found that path results that they [possibly] invited their friends [disparagement].

I pursued and captured every mouse and caught them by means of my hands which [they] doned two gloves in order to protect myself (regarding mice if [they] touch one's skin, [they] can cause one to feel [disparagement] sick because mice can [possibly] carry poisonous little animals exploiting called English-ly "viruses". So scientists advise that to protect one's hands then clean them after [the] pursuing).

Regarding [the] mice i contained the 3 of them in tall container in order to [possibly] prevent escaping their. I probably caused to be afriad them that result [from] pursuing them so violently. So i fed them seeds and water in order to make feel calm [to] the 3 of them.

I was preparing to go work toward too slowly that morning so was no time to me for the sake of releasing the 3. When [I] [the] container that i had put [the] three mice into finally left home with and arrived working place at, it remained inside my car.

Regarding the 3 mice, was rainstorm powerful outside but they 3 were safe and dry but made me feel worry the thing that they 3 were captured and outside lol. The storm weakened so there was opportunity to me to check the condition of emotions of 3 of theirs. Regarding the 3 [they] felt [apparently] calm and were eating seeds that i fed to them. Was [disparagement] so mice's odor inside container hrh.

After working, I released the 3 thems around [the] hanging out field that is "park" English-ly, and [the] 3 thems departed in a jumping way.

#all words in red are words/phrases im unsure abt#oel.mine#this al hapoened in january lol#this took forever#anyway look how cute they look#lì'fya lena'vi#na'vi#contains pic

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nzinga Mbande: Warrior Queen of Angola

Nzinga Ana de Sousa Mbande (c. 1583 – 17 December 1663) was a southwest African ruler who ruled as queen of the Ambundu Kingdoms of Ndongo (1624–1663) and Matamba (1631–1663), located in present-day northern Angola. Born into the ruling family of Ndongo, her father Ngola Kilombo Kia Kasenda was the king of Ndongo. She is remembered in Angola as the Mother of Angola, the fighter of negotiations,…

View On WordPress

#African History#African Leaders#Ambundu Kingdoms of Ndongo#Angola History#central africa history#Nzinga Ana de Sousa Mbande

1 note

·

View note

Text

DJ FLAVIO NGOLA – RESILIÊNCIA (EP) 2025

DJ FLAVIO NGOLA – RESILIÊNCIA (EP) SITE PARA BAIXAR MÚSICAS MP3 , SONG FREE 2025

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The melody of memory: the ancestral hymn that united two continents

In the summer of 1933, linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner (1890-1972) and musicologist Lydia Parish visited Amelia Dawley in Harris Neck, Georgia. This was a coastal community of Black landowners from the Gullah ethnic group. Turner recorded the song sung by Dawley, which the community had known for ages without understanding its meaning. This marked the beginning of a journey to their roots.

Origin of the Gullah Language

Turner was interested in Gullah culture, which had remained isolated from outsiders, especially white people. The Gullah people were descendants of slaves from plantations in South Carolina and Georgia, comprising individuals from the Mandingo, Bamana, Wolof, Fula, Temne, Mende, Vai, Akan, Ewe, Bakongo, and Kimbundu ethnic groups.

Turner hypothesized that their language was either an archaic or childlike form of English. To uncover this part of American linguistic history, which he would publish in "Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect," he first had to earn their trust. Through his research, he realized that Gullah had no trace of English and reasoned that it could have survived similarly to Pennsylvania Dutch, a dialect of German preserved through relative isolation. The study of their language indicated a common origin with the languages of Jamaica and Barbados, suggesting it originated from some part of West Africa. After years of studying their creole languages and African languages, he narrowed his search down to the Mende and Vai languages.

youtube

Among the data he recorded, in chapter 9 of his book, he published Dawley's song, considered the longest known African language song in the United States. Its meaning was unknown, but in 1941, his Sierra Leonean student Solomon L. Caulker recognized the repetition of the term "kambei" ("grave") in the Mende language. Thanks to this revelation, Turner was able to publish a translation of the funeral song:

Ah wakuh muh monuh kambay yah lee luh lay tambay Ah wakuh muh monuh kambay yah lee luh lay kah. Ha suh wileego seehai yuh gbangah lilly Ha suh wileego dwelin duh kwen Ha suh wileego seehi uh kwendaiyah.

Come together, let's work hard; the grave is not yet finished; let its heart be perfectly at peace. Come together, let's work hard; the grave is not yet finished; let its heart be perfectly at peace. Sudden death commands everyone's attention, oh elders, oh heads of families. Sudden death commands everyone's attention, like a distant drumbeat.

Turner's works became reference materials, but general interest in the Gullah people experienced a pause. Anthropologist Joseph Opala, who had lived in Sierra Leone for years and studied the ruins of slave trading centers, was the one who revived the interest.He began with the records from the Ball plantation in South Carolina and the slave ship and auction records discovered in New York, which showed a complete trace from Africa to the present day. In his documentary Family Across the Sea (1989), he gathered Emory Campbell and several Gullah leaders for a trip to Sierra Leone.

The Return of the Funeral Hymn

However, although enthusiastic about the idea, Sierra Leone felt it was not enough. They needed clearer links. That's when they collaborated with ethnomusicologist Cynthia Schmidt to find the origin of Dawley's song. They searched the district where they estimated its most likely origin, but found no one who knew it. This changed in the periphery, in Senehun Ngola, where they found Bendu Jabati.

Bendu Jabati had heard this song sung by his grandmother, who told him it was sung in honor of the ancestors. It was a hymn sung at funerals, associated with a very important ceremony for the Mendé: the Tenjami ("Crossing the River"). Knowing that it was a cultural element that could be lost, his grandmother taught it to him, along with the movements to show her mourning. The custom was for the men to prepare the grave, while the women pounded the rice. It was performed on the third day of a woman's funeral or the fourth of a man's, symbolizing the bridge between the world of the living and the dead. Relatives spent the night and part of the next day at the burial site performing the final rites. After preparing and eating rice, participants completed the ritual by turning over an empty pot of rice, leaving it on the ground as a farewell. This ceremony disappeared after World War I, when soldiers recruited by the British Army introduced Islam and Christianity upon their return.

youtube

The meeting took place in 1997 between Mary Moran (1921-2022), daughter of Amelia Dawley, and her family, with Bendu Jabati. They were welcomed by the president of Sierra Leone in Freetown and taken to Senehun Ngola, where they met Bendu Jabati. By that time, they had the full text of the song provided by Sierra Leonean linguist Tazieff Koroma and translated by him, Edward Benya and Opala. In Sierra Leone, the song was slightly different, possibly because of the development of the language over the intervening centuries. When Mary Moran and Bendu Jabati met, it proved that this hymn had survived another generation. This encounter was shown in the documentary The Language You Cry (1998).

A wa kaka, mu mohne; kambei ya le'i; lii i lei tambee. A wa kaka, mu mohne; kambei ya le'i; lii i lei ka. So ha a guli wohloh, i sihan; yey kpanggaa a lolohhu lee. So ha a guli wohloh; ndi lei; ndi let, kaka. So ha a guli wohloh, i sihan; kuhan ma wo ndayia ley.

Come quickly, let us work hard; the tomb is not yet finished; his heart has not yet grown cold. Come quickly, let us work hard; the tomb is not yet finished; let his heart be cool now. Sudden death cuts down the trees, borrows them; the remains slowly disappear. Sudden death cuts down the trees; let it be satisfied, let it be satisfied, at once. Sudden death cuts down the trees, borrows them; a voice speaks from afar.

Recognizing a Slave Girl

In Sierra Leone, however, they wanted an even more concrete connection: the name of a slave who had left their homeland. Despite the difficulty of the task, Opala found in the Martin family papers the name of Priscilla, a girl who was taken from Sierra Leone to Charleston in 1756. Although it is unknown exactly how she was obtained, contemporary records speak of abductions by other Africans, especially from enemy kingdoms, such as the Fula, Mandingo or Susu. They were kidnapped, prisoners of war, people convicted of crimes or sold to pay debts. In exchange, the British offered them guns, gunpowder, clothes, rum, metal goods and various trinkets. Of the 40 British slave castles or fortified trading posts in Sierra Leone, he would have passed through Bunce Island, the largest and only major castle on the Rice Coast. She would have come from the interior to the coast walking naked or with rags and bound hands. Before traveling by sea, she would have been branded and auctioned off. After surviving the rough voyage across the Atlantic on the ship Hare, she would have stayed 10 days in quarantine, being one of the few people in good condition, and then put to work in a rice field. Although the Hare was a British ship owned by the London owners of Bunce Island, New-York Historical Society records said it was an American slave ship owned by Samuel and William Vernon, two of the wealthiest merchants in colonial Rhode Island, sailing from Newport, Rhode Island.

In America, Priscilla would have fallen in love a decade later with the slave Jeffrey, with whom in 1770 she had three children and, in 1811, after his death, about 30 grandchildren. Her descendants continued to work on the plantation until early 1865, when the plantation was taken over by the Federals. Henry, one of his freed descendants, took the surname Martin and had ten children with Anna Cruz. Of these, roofer Peter Henry Jr. was born in 1886 and had Thomas P. Martin in 1933. At the time of the investigation, he was to have been the one to make the trip, but he died and was replaced by his daughter Thomalind Martin Polite, a 31-year-old speech pathologist at a primary school. Their reunion in Sierra Leone was shared in the documentary Priscilla's homecoming (2005).

In conclusion, although slavery attempted to erase the identity of its victims, they have the power to preserve the customs that connect them to their roots through the centuries. The song itself bridged the gap between the two shores, reuniting through their descendants those who had been separated.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part Two of Queen Nzinga - Historical Story time

This Coloring Page was inspired by the 17th century warrior Queen Nzinga of Matamba & Ngola which is present day Angola 🇦🇴.

Let me know which historical figure I should do next. And don’t forget to share a little history with friends!

The coloring pages are available for free on my socials! Enjoy!

#angola#african fashion#african art#african queen#african history#juneteenth2024#juneteenth#black coloring pages#black history art#timelapse#timelapse art#educational coloring#unique coloring page#historical fashion#illustrations#black queen#story time#story telling#history lesson#history lover#coloringtherapy#african ancestry

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1997 Amelia’s daughter, Mary Moran, and other members of the Moran family were invited to Sierra Leone, West Africa, where they were welcomed in Freetown by Sierra Leone’s President and then flown by helicopter to the country’s interior. There, in the small village of Senehun Ngola, Mary and Bendu Jabati met and sang this song together for the first time. Years earlier, Bendu’s grandmother had told her that this song, which had been passed down in her village from mother to daughter for centuries, would one day reunite her to long-lost relatives.

In addition to finding out where in Africa her ancestors were abducted into slavery, Mary Moran discovered the meaning of the Mende song: a processional hymn for the final farewell to the spirit, it was sung in Senehun Ngola by women as they prepared the body of a loved one for burial.

(The OP's link leads to a site with a recording of the song sung by both Mary Moran and her mother, Amelia)

TIL a family in Georgia claimed to have passed down a song in an unknown language from the time of their enslavement; scientists identified the song as a genuine West African funeral song in the Mende language that had survived multiple transmissions from mother to daughter over multiple centuries (x)

89K notes

·

View notes

Text

Imbokodo #2 by Thabo Rametsi, Thabiso Mabanna and Katlego Motaung. Cover by Motaung. Out in November.

"Lieutenant Manthatisi, the Nameless Warrior, and a team of Imboko join Chief Moshe and set sail for Thaba N'chu. With war on the horizon, and the land teeming with refugees, will they find answers to the missing girls? Are Emperor Mbande and the Ngola behind the carnage and kidnapping - or are there other forces at play?"

6 notes

·

View notes