I share and translate here (ty DeepL) everything I post on Blogger.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Shennong tasting which herbs are good.

from the series Oriental Medical Greats

Studio Tadeuma [behance]

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

This was generated by MidJourney AI.

Alpine lotus leaf flower

69K notes

·

View notes

Text

It looks like the same banyan tree. I found it: 23°28'33.98"N 116°20'45.19"E

425 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is how it goes. It's from Weavers, scribes, and kings: a new history of the ancient Near East by Amanda H. Podany.

Decadent, dissolute modernity - tentatively dated as having begun sometime in the 3rd millennium BCE

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

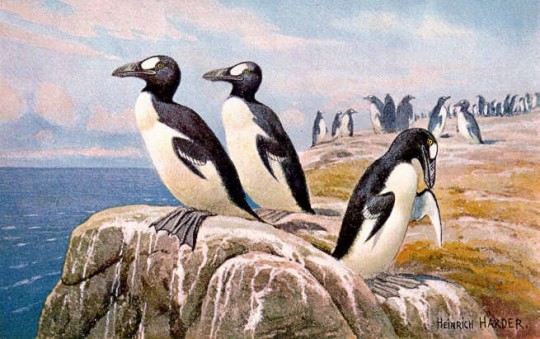

The original penguin lived in the north.

At the end of the 16th century, the word penguin appears together with the Dutch pinguïn, which originated the French word pingouin. The original meaning is preserved in the latter, as pingouin is an auk, while manchot is a penguin, although the influence of modern English is changing this. Despite Antarctica had not yet been discovered, Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama may have seen them in southern Africa, as did Juan Sebastián Elcano. However, the word did not really refer to the friendly birds of the South Pole, but to the giant auks (Pinguinus impennis) of the Arctic.

Penguins from the northern hemisphere

The northern penguin was a bird that reached the breeding grounds on the European and North American rocky coasts in May, nesting even in Gibraltar and Florida. Although it is not known how they timed their travel, they reached their destination without forming large flocks. They tended to arrive emaciated, but regained their stocky figure by feeding on fish, diving headfirst off cliffs. Unlike the common auk (Alca torda), they could not fly with their wings, but were excellent swimmers. However, on land, where they remained with their torso upright, they were rather clumsy. Because of this and their black and white plumage, explorers believed that the birds in the southern hemisphere were also penguins.

Known since antiquity

Apart from the name penguin, the Basque sailors knew it as harpoonaz, the French explorer Jacques Cartier called them apponatz and the Norse called them geirfugl. All these names referred to its beak, which penetrated the water like a harpoon. Possibly, this bird was known to the Greek explorer Pytheas, who reached Iceland in 330 BC. The same must have happened in the gold rush of 1570, when 600 Dutch, German and French ships headed for Baffin Island only to find mica instead of the golden metal. By then, they were extinct in most of Europe. Long gone was the 10th century A.D., when their feathers were used to stuff mattresses. So in England and America they decided to travel north to get them, plucking them and leaving the birds to die miserably.

Capture and extinction

Because they were easy to capture and had a considerable size, when they came ashore to spawn they were captured by the dozens. Their eggs were also collected, but the fact that each pair laid only one was their undoing. In addition, the hunters knew that not all birds laid eggs on the same day, so those that were saved in a first expedition were lost in the following ones. In this way, due to human action and other predators, such as polar bears, the giant auks were retreating northward.

By the beginning of the 19th century, they had disappeared from Newfoundland. Just two decades later, many believed them to be a legend, although the occasional pair could be found in the more remote British Isles. Many of these specimens ended up stuffed in museums. Until then, Geirfuglasker Island was their last bastion. Due to currents and cliffs, it was inaccessible to humans, but not to these birds. Unfortunately, a volcanic explosion destroyed it in 1830 and they had to retreat to Eldey. On June 3, 1844, Sigurdr Islefsson, Jon Brandsson and Ketil Ketilsson arrived on the island of Eldey, near Iceland, and killed the last two giant auks, whose size made them easily visible among the other birds. Although subsequent sightings were reported and there were rewards for decades for obtaining new specimens, it is believed that these were the last of the auks.

0 notes

Text

The whimsical soul of ships

According to the folklore of the sailors of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, on long voyages they always had company on their ships. It was an invisible crewman who made himself subtly or outrageously noticeable: the ship's spirit.

The ship's spirit was a type of elf that the Norwegians call nisse, the Swedes tomte and the Finns tomtenisse or tontu, i.e., it belongs to the same type of beings as Santa's helpers. In Germany, the equivalent of these beings was the kobold; in Brittany, France, it is a lutin or luiton; in the Netherlands, it was a kabouter(man), while in Great Britain it was a puck, pixie or brownie. On the whole, they are mischievous little domestic or nature creatures that help those who favor them and harm those who do not. However, as these creatures are best known when on a ship is by their German name, klabautermann ("Striker"). In Denmark, it may appear assimilated with skibsnisse, while in the Frisian Islands, Schleswig-Holstein and Pomerania it may appear assimilated with puck.

The klabautermann was a ship-dwelling goblin. As a goblin, he was a small, pipe-wielding being who acted according to the respect he received. If he was well cared for, the voyages prospered and the ship was protected. Because of this, he can appear as a carpenter who fixes at night everything that breaks during the day, which is why he is also called klütermann. Conversely, if he was abandoned, the ship would meet its end. When he was heard restlessly running about the shrouds, making noises in the rigging and in the hold, it was the signal for the crew to leave the ship immediately. His mood also manifested itself in less extreme situations. He was believed to maintain order and discipline on the ship by shouting orders, especially among the young and unruly crewmen. To sailors, he could be both a help and a hindrance, hitting them on the head, humiliating them, taunting them or punishing wrongdoers. In fact, the name klabautermann was derived from the commotion he caused.

Besides looking like a carpenter or smoking a pipe, he wore yellow breeches, horseman's boots, a red or gray jacket and a cap like that of the American pilgrims, also reminiscent of the top hat of the leprechaun. He had a large red head and green teeth and used to sit under the halter. The horseman's boots, with which he used to appear in calm seas, could be related to horse latitudes near the equator, at 30° north latitude and 38° south latitude. It seems that these received their name because, in this area of high pressure, travel was slower, having to ration water and slaughter the horses that consumed more.

Now, how was the klabautermann born? Well, according to the beliefs, the soul of a ship was the same that was in the wood of the trees. The trees could have obtained the soul of a human being or possessed the soul of another being. This is possibly related to the Vårdträd or Tuntre, sacred trees planted on special occasions that represented ancestors and nature spirits.

Although it is a connection without unanimous support, it is related to Seals of Sinope, to whom traditionally sailors served a portion of each meal. This was bought by a traveler, whose money remained in the hands of the captain to be distributed among the poor upon arrival at port.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ea-Nasir, the merchant famous for his bad copper

A bad reputation is eventually forgotten and, if your memory is inconvenient, a damnatio memoriae eliminates even your good reputation. Despite this, there are people whose bad opinion endures for centuries or even millennia. As many others as there may be, Ea-Nāṣir is the paradigm of disrepute.

Its history is set in the Isin-Larsa period, in the city of Ur at the time of Larsa's splendor, during the reign of Rim Sin I, before Hammurabi of Babylon united the whole region, and when it was the nerve center of the Persian Gulf trade. Then, in the temple of Šamaš, traders met with investors. Investors paid in silver or other trade goods, mainly reed baskets, but also objects such as bracelets. Ea-Nāṣir was a merchant who mostly brought copper from Dilmún, as well as precious stones and spices. The territory of Dilmun corresponded to Bahrain and Failaka Island (Kuwait). Each investor only risked his share and, if all went well, he could take a share of the profits. Although Ea-Nāṣir took most of the profits, since each investor was only responsible for his share, the additional costs were borne by him. Thus, by taking less risk, the door was open to the small investor, who also did not need to bring in great wealth, although the profits depended on what could be obtained by trading what was offered.

Ea-nāṣir’s tablets

Unfortunately, whether by sea or land, trade is risky and merchandise is often lost. There were also dishonest traders and dissatisfied investors. At No. 1 Old Street in Ur, Sir Leonard Wooley found, between 1922 and 1934, 29 tablets from the so-called Ea-Nāṣir archive. This one we know mainly from a tablet where Nanni presents a complaint (UET V 81). This is the oldest known complaint:

Tell Ea-Nāṣir: Nanni sends the following message.

When you came, you told me in such a way "I will give Gimil-Sin (when he arrives) copper ingots of good quality." You left but did not do what you promised me. You showed ingots that were not good before my messenger (Ṣīt-Sin) and said "If you want to take them, take them, if you do not want them, go!"

Why do you take me, that you treat someone like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like us to collect the sack with the money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with disdain by sending them to me several times empty-handed, and that for enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants of Dilmun who has treated me in such a manner? Only you treat my messenger with contempt! Regarding that (insignificant) mine [~0.5-1 kg] of silver I owe you, feel free to speak in such a manner, while I have given the palace on your behalf 1 080 pounds of copper, and Šumi-abum has also given 1 080 pounds of copper, in addition to what we have both had written on a sealed tablet to keep in the temple of Šamaš.

How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my bag of money from me in enemy territory; now it is up to you to restore me (my money) in full.

Know that (henceforth) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of good quality. I shall (henceforth) select and take the ingots individually from my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of refusal because you have treated me with contempt.

Both are mentioned again in another tablet (UET V 66):

Talk( to Ea-Nāṣir) and, thus says Nanni. May Šamaš bless your lives. Since you wrote to me, I have sent Igmil-Sin to your [...]. The copper from my purse and the purse of Eribam-Sin, seal it for him. He can bring it. Give good copper to him.

We may note that Ea-Nāṣir must have been in trouble regularly, for he needed to appease two men (UET V 72):

Tell the Shumun-libshi and the Zabardabbû [Sumerian loan: coppersmith or one who stored copper]: Ea-Nāṣir and Ilushu-illasu say: Concerning the situation with Mr. "Shorty" [kurûm] and Erissum-matim, who came here, do not be afraid. I made them enter the temple of Šamaš and take an oath. They said, "We did not come for those matters; we came for our business." I told them, "I will write to you" - but they did not believe me! He said, "I have a dispute with Mr. Shumun-libshi." He said, "[...] to your partner. I took, and you did not do [...]. You did not give it to me." In three days, I will reach the city of Larsa. Also, I spoke to Erissum-matim and said, "What is your sign [password, hidden omen, personality]?" I said to the teapot maker, "Go with Ilum-gamil to the Zabardabbû, and take the deficit for me, and put it in the city of Enimma." Also, do not neglect your [...]. Also, I have given the ingots of which we spoke to men. [Written on the edge] Don't be critical! Take the [...] from them! Don't worry! We'll come and get you.

The tension could turn to jest (UET V 20):

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir; thus says Ili-idinnam. Now, you have done a good job! [with sarcasm]. A year ago, I paid silver. In a foreign country, (only) you will retain bad copper. If you wish, bring your copper.

For, apparently, the precious copper did not always reach the one who wanted it (UET V 29):

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir; thus says Muhaddum concerning the ingots: the sealed tablet of your companions has "gone" with you. Now Saniqum and Ubajatum have gone to see you. If you really are my brother, send someone with them, and give them the ingots that are at your disposal.

So he had to worry about keeping the investors in a good mood (UET V 22):

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir, thus says Ilsu-ellatsu regarding the copper of Idin-Sin, Izija will come to you. Show her 15 ingots so that she can select 6 good ingots and give those to them. Act so that Idin-Sin does not get angry. To Ilsu-rabi give 1 copper talent from Sin-remeni, the son of [...].

On the whole, whether by his failures or his successes (UET V 5), it is shown that Ea-Nāṣir's main activity was to bring copper in exchange for silver:

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir; thus Appa says. My copper give it to Nigga-Nanna - good (copper) - so that my heart will not be tormented; Besides copper from 2 silver mines Ilsu-ellatsu asked me to give. [...] With my copper, for 1(?) silver mine give copper and silver (for him). I will pay [...]. And a copper kettle that (may) contain 15 qa [qa≈10 cm3] of water and 10 mines of other copper send it to me. I will pay silver for it.

Some of the people are recurrent, such as Sumi-abum (UET V 55):

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir and Ilsu-ellatsu; thus says Sumi-abum. May Samas bless your lives. Now summatum and [...] to you I have sent. They have come to you. 1 silver mine he (they or I) has (have/have) sent.

The state of preservation of the tablets sometimes leaves us with questions, such as what question there was regarding the apprentice (UET V 54).

Speak to Ea-Nāṣir; thus says Sumi-abum. Concerning the question [...] of the apprentice [...].

Finally, tablet records what looks like an inventory (UET V 848/BM 131428):

11 garments: 1/3 mine value [mina≈0.5-1 kg], 2 2/3 shekels of silver [shekel≈8.3 g]. 5 garments: value: 13 silver shekels. 2 garments value: 6 1/2 silver shekels 5 garments: value: 10 2/3 silver shekels 27 garments: value: 5/6 mina, 4 1/2 shekels, 15 še [še≈0.05 g]. ------- (total) 50 garments: value: 1 2/3 mina, 7 1/3 shekels, 15 še: in the hands of Mr. Ea-Nāṣir.

Šamaš’s temple

It is convenient to remember that Šamaš was the solar god, who dispensed justice because he could see from the sky. His temple was a place for agreements, distributing fairly, with the god as witness, profits and losses. As they had a good reputation, the temples were a place to deposit money, serving as a bank and offering loans. The divine awe ensured that borrowers would repay and kept interest rates low. These temples also stored private goods marked with their corresponding seals to distinguish their owners. In addition, although citizens did not own the temples, they owned land on behalf of the former. These were regional economic engines that the state kept in check with taxes to prevent them from accumulating too much power, but without harming local productivity.

Copper trade

During the Bronze Age, copper was incredibly important in Mesopotamia for its practical and military applications. In the Akkadian Empire (c. 2334-2154 B.C.) and the third dynasty of Ur (c. 2112-2004 B.C.), Mesopotamian temples organized trips to Magan, on the Oman peninsula, and Meluhha, in the Indus Valley. Magan then had a monopoly on copper, but in the Isin-Larsa period (2025-1763 B.C.), this responsibility rested in the hands of the traders themselves. However, their efficiency must have been good enough for the state not to take control of the trade and entrust them with the palace's copper supply. It was then that Dilmun began to prosper to the detriment of Magan, which temporarily coincided with the decline of the Indus Valley civilization. This copper would have come to Dilmun from Gujarat, Rajasthan, in present-day India, and the southern half of Iran. However, this prosperity would gradually disappear from the end of the Isin-Larsa period. With the decline of the successive Paleo-Babylonian Empire (1792-1595 B.C.) and the rise of the later Kassite Empire (c. 1531-1155 B.C.), Mesopotamia obtained copper from Cyprus, so that the Dilmun copper merchants went bankrupt.

In its period of prosperity, the price of copper in Dilmun must have been attractive to Persian Gulf traders, who transported it in large quantities. The palace of Larsa was a participant in this trade and was possibly the main investor in Ea-Nāṣir, for he imported as much as 18 tons for it. Some of the names mentioned on the tablets could belong to palace administrators.

Usually, Ea-Nāṣir traveled by sea to Dilmun to buy copper in exchange for silver, staying there for a while, at which time he sent the ships to Ur. Tablets with orders and reproaches would reach him while there and he would subsequently take them to his house in Ur. In this, he had a large courtyard and furnaces with models and tools, so perhaps copper was worked there and some customers brought copper to obtain a specific product, such as teapots. This occupation would increase the fire risk of the domicile, explaining the state of some of the slats. Since he had a large business with the palace, perhaps that is why he could afford to neglect minor investors. While in Dilmun, some of his investors gave copper to the palace on his behalf. Of the recurring names, Nanni would have been a local copper merchant, while Arbituram a creditor to whom Ea-Nāṣir owed debts. Nigga-Nanna was possibly a middleman employed by Ea-Nāṣir.

0 notes

Text

The melody of memory: the ancestral hymn that united two continents

In the summer of 1933, linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner (1890-1972) and musicologist Lydia Parish visited Amelia Dawley in Harris Neck, Georgia. This was a coastal community of Black landowners from the Gullah ethnic group. Turner recorded the song sung by Dawley, which the community had known for ages without understanding its meaning. This marked the beginning of a journey to their roots.

Origin of the Gullah Language

Turner was interested in Gullah culture, which had remained isolated from outsiders, especially white people. The Gullah people were descendants of slaves from plantations in South Carolina and Georgia, comprising individuals from the Mandingo, Bamana, Wolof, Fula, Temne, Mende, Vai, Akan, Ewe, Bakongo, and Kimbundu ethnic groups.

Turner hypothesized that their language was either an archaic or childlike form of English. To uncover this part of American linguistic history, which he would publish in "Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect," he first had to earn their trust. Through his research, he realized that Gullah had no trace of English and reasoned that it could have survived similarly to Pennsylvania Dutch, a dialect of German preserved through relative isolation. The study of their language indicated a common origin with the languages of Jamaica and Barbados, suggesting it originated from some part of West Africa. After years of studying their creole languages and African languages, he narrowed his search down to the Mende and Vai languages.

youtube

Among the data he recorded, in chapter 9 of his book, he published Dawley's song, considered the longest known African language song in the United States. Its meaning was unknown, but in 1941, his Sierra Leonean student Solomon L. Caulker recognized the repetition of the term "kambei" ("grave") in the Mende language. Thanks to this revelation, Turner was able to publish a translation of the funeral song:

Ah wakuh muh monuh kambay yah lee luh lay tambay Ah wakuh muh monuh kambay yah lee luh lay kah. Ha suh wileego seehai yuh gbangah lilly Ha suh wileego dwelin duh kwen Ha suh wileego seehi uh kwendaiyah.

Come together, let's work hard; the grave is not yet finished; let its heart be perfectly at peace. Come together, let's work hard; the grave is not yet finished; let its heart be perfectly at peace. Sudden death commands everyone's attention, oh elders, oh heads of families. Sudden death commands everyone's attention, like a distant drumbeat.

Turner's works became reference materials, but general interest in the Gullah people experienced a pause. Anthropologist Joseph Opala, who had lived in Sierra Leone for years and studied the ruins of slave trading centers, was the one who revived the interest.He began with the records from the Ball plantation in South Carolina and the slave ship and auction records discovered in New York, which showed a complete trace from Africa to the present day. In his documentary Family Across the Sea (1989), he gathered Emory Campbell and several Gullah leaders for a trip to Sierra Leone.

The Return of the Funeral Hymn

However, although enthusiastic about the idea, Sierra Leone felt it was not enough. They needed clearer links. That's when they collaborated with ethnomusicologist Cynthia Schmidt to find the origin of Dawley's song. They searched the district where they estimated its most likely origin, but found no one who knew it. This changed in the periphery, in Senehun Ngola, where they found Bendu Jabati.

Bendu Jabati had heard this song sung by his grandmother, who told him it was sung in honor of the ancestors. It was a hymn sung at funerals, associated with a very important ceremony for the Mendé: the Tenjami ("Crossing the River"). Knowing that it was a cultural element that could be lost, his grandmother taught it to him, along with the movements to show her mourning. The custom was for the men to prepare the grave, while the women pounded the rice. It was performed on the third day of a woman's funeral or the fourth of a man's, symbolizing the bridge between the world of the living and the dead. Relatives spent the night and part of the next day at the burial site performing the final rites. After preparing and eating rice, participants completed the ritual by turning over an empty pot of rice, leaving it on the ground as a farewell. This ceremony disappeared after World War I, when soldiers recruited by the British Army introduced Islam and Christianity upon their return.

youtube

The meeting took place in 1997 between Mary Moran (1921-2022), daughter of Amelia Dawley, and her family, with Bendu Jabati. They were welcomed by the president of Sierra Leone in Freetown and taken to Senehun Ngola, where they met Bendu Jabati. By that time, they had the full text of the song provided by Sierra Leonean linguist Tazieff Koroma and translated by him, Edward Benya and Opala. In Sierra Leone, the song was slightly different, possibly because of the development of the language over the intervening centuries. When Mary Moran and Bendu Jabati met, it proved that this hymn had survived another generation. This encounter was shown in the documentary The Language You Cry (1998).

A wa kaka, mu mohne; kambei ya le'i; lii i lei tambee. A wa kaka, mu mohne; kambei ya le'i; lii i lei ka. So ha a guli wohloh, i sihan; yey kpanggaa a lolohhu lee. So ha a guli wohloh; ndi lei; ndi let, kaka. So ha a guli wohloh, i sihan; kuhan ma wo ndayia ley.

Come quickly, let us work hard; the tomb is not yet finished; his heart has not yet grown cold. Come quickly, let us work hard; the tomb is not yet finished; let his heart be cool now. Sudden death cuts down the trees, borrows them; the remains slowly disappear. Sudden death cuts down the trees; let it be satisfied, let it be satisfied, at once. Sudden death cuts down the trees, borrows them; a voice speaks from afar.

Recognizing a Slave Girl

In Sierra Leone, however, they wanted an even more concrete connection: the name of a slave who had left their homeland. Despite the difficulty of the task, Opala found in the Martin family papers the name of Priscilla, a girl who was taken from Sierra Leone to Charleston in 1756. Although it is unknown exactly how she was obtained, contemporary records speak of abductions by other Africans, especially from enemy kingdoms, such as the Fula, Mandingo or Susu. They were kidnapped, prisoners of war, people convicted of crimes or sold to pay debts. In exchange, the British offered them guns, gunpowder, clothes, rum, metal goods and various trinkets. Of the 40 British slave castles or fortified trading posts in Sierra Leone, he would have passed through Bunce Island, the largest and only major castle on the Rice Coast. She would have come from the interior to the coast walking naked or with rags and bound hands. Before traveling by sea, she would have been branded and auctioned off. After surviving the rough voyage across the Atlantic on the ship Hare, she would have stayed 10 days in quarantine, being one of the few people in good condition, and then put to work in a rice field. Although the Hare was a British ship owned by the London owners of Bunce Island, New-York Historical Society records said it was an American slave ship owned by Samuel and William Vernon, two of the wealthiest merchants in colonial Rhode Island, sailing from Newport, Rhode Island.

In America, Priscilla would have fallen in love a decade later with the slave Jeffrey, with whom in 1770 she had three children and, in 1811, after his death, about 30 grandchildren. Her descendants continued to work on the plantation until early 1865, when the plantation was taken over by the Federals. Henry, one of his freed descendants, took the surname Martin and had ten children with Anna Cruz. Of these, roofer Peter Henry Jr. was born in 1886 and had Thomas P. Martin in 1933. At the time of the investigation, he was to have been the one to make the trip, but he died and was replaced by his daughter Thomalind Martin Polite, a 31-year-old speech pathologist at a primary school. Their reunion in Sierra Leone was shared in the documentary Priscilla's homecoming (2005).

In conclusion, although slavery attempted to erase the identity of its victims, they have the power to preserve the customs that connect them to their roots through the centuries. The song itself bridged the gap between the two shores, reuniting through their descendants those who had been separated.

4 notes

·

View notes