#native North American insect species

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bzzz!

Just some bees in my garden and in the fields and on a neighbourhood walk. :)

Featured bees include bumblebees (native), green sweatbees (native), honeybees (invasive), carpenter bees (native), and some I'm not sure about.

Featured flower hosts include bull thistles (invasive weed), rose of sharon (invasive), New England aster (native), cup plant (native), starthistle (not native), Nuttall's sunflower (native), purple coneflower (native), anise hyssop (native), white wood aster (native), swamp milkweed (native), sow thistle (invasive weed), creeping charlie (invasive), creeping thistle (invasive weed), wild rose (native maybe), wild bergamot (native), bride's feathers (native), bigleaf lupin (native maybe or invasive), and upright prairie coneflower "Mexican hat" (native species, but a cultivar).

All my photos, unedited. Don't mind the weirdness of the third last photo. It's my phone's "portrait" which I found out belatedly can have, uh, interesting results.

#bees#bumblebees#insects#hymenoptera#bees wasps and ants#honeybees#sweatbees#carpenter bees#my photos#photography#blackswallowtailbutterfly#bees on flowers#flowers#native North American plant species#native North American insect species#thistles#milkweed#sunflower#purple coneflower#upright prairie coneflower#swamp milkweed#lupin#bigleaf lupin#asters#New England aster#white wood aster#coneflowers#wild rose#starthistle#creeping charlie

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xerces Society: Announcing The State Of The Bees Initiative: Our Plan To Study Every Wild Bee Species In The U.S.

This is really exciting news! For those unaware, the Xerces Society has been focusing on invertebrate conservation for over fifty years, and has pioneered a lot of the work to bring awareness to the devastating losses of not only insects but other terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates. It gets its name from the Xerces blue butterfly (Glaucopsyche xerces), the first North American butterfly driven to extinction by human activities.

Even if you haven't heard of the Xerces Society, you've probably come across various "Save the Bees!" campaigns. These frequently focus on the domesticated European honey bee (Apis mellifera), which, while it may be important to crop pollination in many parts of the world, is not a part of natural ecosystems in places like the Americas and Australia, and can be considered an invasive species at times. With the rise of colony collapse disorder (CCD) particularly after the turn of the 21st century, where entire domestic honeybee colonies would die off, the need to preserve bees began to gain wider public acknowledgement.

But what many people don't realize is that it is the thousands upon thousands of other native bee species worldwide that are in greater danger of extinction. They don't have armies of beekeepers giving them safe places to live and treating them for diseases and parasites. More importantly, where honey bees may visit a wide variety of plants, native bees often have a much narrower series of species they visit, and they are quite vulnerable to habitat loss. Most bees are not as social as honey bees and live solitary lives, unseen by the casual observer.

Invertebrates in general often suffer from a lack of conservation information, meaning that particularly vulnerable species may fly under the radar and risk going extinct without anyone realizing until it's too late. This ambitious program by the Xerces Society aims to solve that problem, at least for the 3,600+ species of bee in the United States. If they can assign a conservation status to each one, then that strengthens the argument toward protecting their wild habitats and working to increase their numbers. Hopefully it will also prompt more attention to other under-studied species that are in danger of going extinct simply because we don't know enough about them.

#bees#save the bees#invertebrates#arthropods#insects#entomology#nature#wildlife#animals#ecology#environment#conservation#science#scicomm#endangered species#extinction#pollinators#Xerces Society#Xerces blue

598 notes

·

View notes

Note

I always hear about the ecosystems that are more biodiverse than expected, like grasslands, deserts, rivers. What ecosystems are less biodiverse that most people expect? Or do all ecosystems have a lot going on?

forests!!!!! i don’t wanna shit on them lol but it’s kinda funny—you go from rainforests, which are a hotbed of biodiversity, to places like the redwood forest or northern coniferous woods which are just…. strangely silent.

in the case of northern coniferous woods (like in parts of alaska), the geology contributes to it. only certain species can survive in geologically active areas with poor soil quality—conifers (pine, spruce, larch) LOVE that shit. in the case of the redwoods and other more southern but still northern forests (loll!! think oregon coast), there’s only so many species that can survive in those poor-quality soils that are constantly wet thru the year. again, wooo conifers!!

the redwoods though are specifically interesting… dense canopy leads to fewer plant species able to grow, which means there’s less food for other animals. if you ever get the chance to visit redwood national park, be silent and listen for a bit. there’s a noticeable lack of insects and birds. all of that goes together!!

that being said—there are some studies being done on the redwood canopies. there are specific fern and moss ecosystems that ONLY grow on those trees, and due to habitat fragmentation it’s pretty hard to gather info on them. these things grow on a scale of hundreds of years, so many of them just don’t exist anymore.

also, though, on the other side of the scale—the southeast US is STAGGERINGLY biodiverse. that part of north america mirrors southeast asia, both are considered rainforests (in parts lol). interestingly, too, there are a lot of species that are very similar despite being separated by the pacific ocean.

example: american beautyberry vs asian beautyberry!!

also, shout out to central texas for being a biodiversity hotspot <333 i will forever maintain that the hill country is one of the most special places in the country!!! old oaks, sycamores, pecans, and bald cypress (best tree) lining the rivers—cliffsides covered in trees, amazing diversity of insects and reptiles, riverside flood plains, native tall grass prairies—it’s amazing!! i’m biased though obviously lol!!

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making Better State Insects

So at some point I stumbled across a list of State Insects. Honestly I wasn't even aware states had "state insects", but as I looked down the list my disappointment grew. A vast majority of states had selected the European honeybee (which is not even native) as their state insect, with monarch butterflies and ladybugs being the two runner ups. I thought this was a damn shame because there's so many interesting insects in the US, so I'm making a better official new list of state insects.

For this list my criteria are:

Insect must be native to the state

No repeats

Insect must be easily observable to the naked eye

I also had general guidelines of picking insects that were relatively common (based on inaturalist heat maps of observation) and picking insects that were cool or interesting. Some of these insects I picked because I thought they were important parts of the areas culture and experience (lovebugs, toebiters, and periodical cicadas) and some insects I picked just to raise awareness that they exist in the US.

I also don't think I gave anyone huge L's, no mosquitoes, louses, cockroaches, ect, because my goal of this list is to get people interested in their native insects and I want it to be fun to find and observe your state insect.

Also some states get gold stars for picking state insects that already meet these criteria and are cool so they get to keep theirs. Some states also have "state butterflies" or "state agricultural insect" which for this list I'm ignoring, you can keep those I'm just focused on state insects. Slight disclaimer also, I've only ever lived in California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and South Carolina, and all these states are keeping their original state insect. So all the insects I'm choosing are for states I haven't lived in. Also I'm not including photos in this post just for my own sanity.

List under the cut!

Alabama

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Giant Leaf-footed Bug (Acanthocephala declivis)

Leaf-footed bugs are cute, they're big, they're stanced up, the males have big back legs, you've probably seen them. Being true bugs they have piercing mouthparts and suck plant juices.

Alaska

Four-spot Skimmer (Libellula quadrimaculata)

Alaska gets to keep their old state insect, it's a cool dragonfly and apparently was partially chosen to honor bush pilots who fly to deliver supplies in the Alaskan wilderness, so really cool!

Arizona

Two-tailed swallowtail butterfly (Papilio multicaudata)

Arizona also gets to keep their state insect. Kind of a shame because Arizona has a lot of cool species, but it did meet my requirements and they get points for choosing a different kind of butterfly.

Arkansas

Old: European honeybee

New: North American Wheel Bug (Arilus cristatus)

One of the largest assassin bugs in the US, these guys are appreciated by gardeners for their environmentally friendly pest control. They also look badass.

California

California Dogface Butterfly (Zerene eurydice)

Endemic to California and on a stamp! Again, kind of a shame because there's a lot of cool insects in California, but I respect this choice, especially since California was the first state to designate a state insect (1929).

Colorado

Colorado Hairstreak Butterfly (Hypaurotis crysalus)

Same deal as California, the state's name is in the common name, unique butterfly found in the four corners region. Just get a stamp or something soon!

Connecticut

Old: European Praying Mantis

New: Cecropia Moth (Hyalophora cecropia)

You picked a state insect no one else had but went with a nonnative mantis? Here's an insect that'll make you stand out and it's a native species. Lesser known than some of the other giant silk moths, the Cecropia moth is the largest native moth and has some truly stunning colors.

Delaware

Old: Convergent Ladybeetle

New: Periodical Cicada (Magicicada septendecim)

Cicada's had to be somewhere on this list and Delaware was one of the main hotspots for brood X, one of the largest broods of the multiple staggered brood cycles. Hey, they have a lot of history in America. Accounts go back as early as 1733, with Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin making a note of them.

District of Columbia

Old: None

New: Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

The Entomological Society of America is trying to get the Monarch Butterfly added as our national insect, so I think that's reason enough to let DOC claim it.

Florida

Zebra Butterfly (Heliconius charithonia)

Florida gets to keep their state butterfly, but the populations that have existed in Florida are in steep decline. Ideally I would want being the official state insect to come with some protections, hopefully people can get invested in reintroducing them.

Georgia

Old: European Honeybee

New: Horned Passalus Beetle (Odontotaenius disjunctus)

Also called bess beetles or patent-leather beetles, these cute guys are important for forest systems because they eat decaying wood, helping to break down felled trees. They're cute beetles that squeak when disturbed.

Hawaii

Kamehameha Butterfly (Vanessa tameamea)

An endemic Hawaiian butterfly named after a ruling dynasty of Hawaii. Their population is under threat, as with a lot of native Hawaiian species, so I think this is a good state insect to build protections and activism around.

Idaho

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Ice Crawler (Grylloblatta sp. "Polaris Peak")

Look Idaho, I have to admit that even though I've traveled extensively through WA, OR, CA, and NV I've never stepped foot in Idaho and I don't intend to. Your state exists in a weird liminal zone, not really the pacific northwest but not really whatever Montana is either. Your state isn't even all in one time zone. So look, I really wanted ice crawlers to be on this list, but they're exclusively found on mountains in the pacific northwest and Sierra Nevadas. Normally I would've given them to Washington or Oregon, but those states already have state insects that work for them. So your state gets ice crawlers, and they do exist in Idaho in the panhandle. It's not an L, ice crawlers are amazing extremophiles that crawl over snow in high elevation mountain peaks. They exist in their own unique order and theres only one genus in the US, with different species being region locked, sometimes onto specific mountains. Their thermoregulation is so delicate, the warmth of someones hand holding them causes them to over heat and die. They're cool, unique, and weird, and let's face it so is your state. At least I didn't take a cop out by picking the potato bug.

Illinois

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Red-banded Leafhopper (Graphocephala coccinea)

Leafhopper done Chicago style.

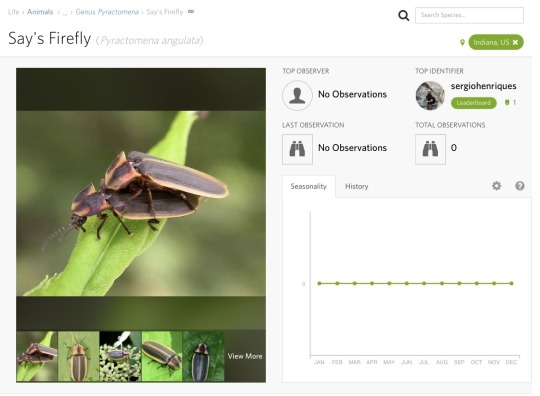

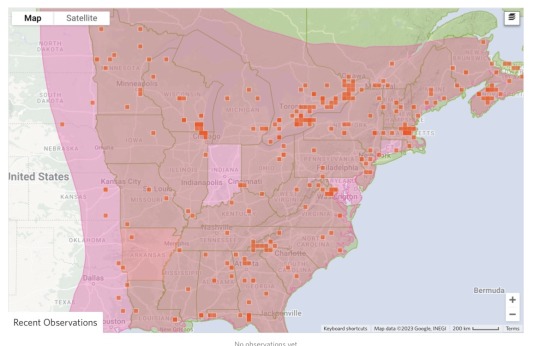

Indiana

Old: Say's Firefly

New: Common True Katydid (Pterophylla camellifolia)

I wanted to give you Say's Firefly. I really did. But when I looked on Inaturalist not A SINGLE OBSERVATION was listed for the species in Indiana. I'm even going to post pictures.

So even though this is extremely funny I'm giving your state the Common True Katydid instead. Large, loud, and easy to spot, these guys can frequently be heard chirping in trees. Not only do different populations have different rates of chirp, but the rate of chirp is also so predictably dependent on temperature that you could make an equation to tell the temperature based on chirp rate.

Iowa

Old: None

New: Westfall's Snaketail (Ophiogomphus westfalli)

Really cool clubtail dragonfly that's almost exclusively found in Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Kansas

Old: European Honeybee

New: Rainbow Scarab (Phanaeus vindex)

A kind of true dung beetle, they play an important role in removing waste. And although they don't roll waste like the stereotypical dung beetles, they are extremely pretty.

Kentucky

Viceroy Butterfly (Limenitis archippus)

This is fine.

Louisiana

Old: European Honeybee

New: Lovebug (Plecia nearartica)

Look, one of the southern states was going to get this one and Louisiana has a majority of the observations for them. Although annoying, it's things like having to scrape thousands of flies off your car that makes the Southern experience. Embrace it!

Maine

Old: European Honeybee

New: Brown Wasp Mantidfly (Climaciella brunnea)

I really wanted these guys to be somewhere on the list. Neither a wasp, mantis, or fly, these are predatory neuropterans related to lacewings. They have raptorial front legs (resembling a mantis) and their coloration resembles paper wasps that they live alongside. Weird, unique, and wonderful!

Maryland

Baltimore Checkerspot Butterfly (Euphydryas phaeton)

This butterfly might've been picked for the resemblance of the state flag. It's in decline in it's native range, so hopefully more awareness and consideration to state insects will help push conservation efforts.

Massachusetts

Old: Ladybug

New: Hornet Clearwing Moth (Paranthrene simulans)

Hornet mimic moth, the caterpillars feed on chestnuts and oaks. All lepidopterans (moths and butterflies) have modified hairs on their wings that form the "scales" that give this order their name. For this moth though, parts of it's wings don't have any scales so it more convincingly resembles a hornet. Underneath the scales, butterfly and moth wings look pretty much like any other insect's wing. Cool!

Michigan

Old: None

New: American Salmonfly (Pteronarcys dorsata)

The biggest salmonfly in North America. They make excellent fishing bait, and several fly fisherman use salmonfly lures to catch trout. Their nymphs are also an important indicator of water quality, with them being one of the first species to disappear in the presence of pollution or contaminants.

Minnesota

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: American Giant Water Bug (Lethocerus americanus)

Also one of the ones that had to be on the list somewhere, and the Inat heatmap says Minnesota. Toebiters are part of the experience, and they are cool and ferocious looking.

Mississippi

Old: European Honeybee

New: Eastern Eyed Click Beetle (Alaus oculatus)

Click beetles have a cool adaption that allows them to launch themselves in the air to avoid predators. This makes an audible sound, hence their common name. The Eastern Eyed Click Beetle is one of the largest and most striking click beetles in the US, with large false eyespots on their thorax.

Missouri

Old: European Honeybee

New: Goldenrod Soldier Beetle (Chauliognathus pensylvanicus)

A soldier beetle that feeds on aphids and small plant pests, these beetles also eat pollen and nectar from flowers. They don't harm the flower, and though their common name reflects their preference for goldenrod flowers, they're also an important pollinator of the prairie onion (Allium stellatum). This is a native species of onion that grows from Minnesota to Arkansas.

Montana

Old: Mourning Cloak

New: Western Sheep Moth (Hemileuca eglanterina)

Mourning Cloak butterflies do technically work for my criteria, but I wanted to showcase some more regional insects in this as well, as Mourning Cloaks are found throughout North America and Eurasia. The Western Sheep Moth is an absolutely stunning giant silk moth, found throughout the western United States. Although not as big as some other silk moths, the bold orange and black coloration on these make them absolutely stand out.

Nebraska

Old: European Honeybee

New: Blowout Tiger Beetle (Cicindela lengi)

A tiger beetle with unique patterns, these guys are active predators and are particularly difficult to spot because they run extremely quickly. They seem to be pretty cold tolerant and exist from Colorado up into Canada.

Nevada

Vivid Dancer Damselfly (Argia Vivida)

This damselfly was picked as Nevada's state insect because it's widespread throughout the state and matches the state colors, silver and blue. That gets my seal of approval!

New Hampshire

Two-spotted Lady Beetle (Adalia bipunctata)

This is fine.

New Jersey

Old: European Honeybee

New: Margined Calligrapher (Toxomerus marginatus)

A pretty hoverfly, they strongly resemble bees in both looks and behavior. Larvae feed on common plant pests such as thrips and aphids, while the adults sip nectar and pollinate flowers. These helpful attributes make it something the Garden State can appreciate!

New Mexico

Tarantula Hawk (Pepsis grossa)

New Mexico wins the official state insect list by a landslide. Not only is the tarantula hawk a super cool and formidable insect to showcase, but New Mexico's state butterfly (Sandia Hairstreak) was discovered in New Mexico. No notes 10/10!

New York

Nine-spotted Lady Beetle (Coccinella novemnotata)

A native species of lady beetle that's been in decline in recent years, New York is one of the last remaining states where they've been spotted. I also appreciate that New York designated a specific ladybug species instead of just saying "Coccinellidae species".

North Carolina

Old: European Honeybee

New: Eastern Rhinoceros Beetle (Xyloryctes jamaicensis)

A large native species of rhinoceros beetle. They breed in ash trees, and are under threat due to competition from the Emerald Ash Borer.

North Dakota

Old: None

New: Nuttall's Blister Beetle (Lytta nuttalli)

As with all blister beetles, these guys have a chemical defense. Unlike the more famous Bombardier Beetle thought, instead of being black and red they are iridescent red/purple and green.

Ohio

Old: Ladybug

New: Bald-faced Hornet (Dolichovespula maculata)

Look, when the one thing everyone knows about your state is that it sucks, it's time to lean into it. Bald-faced hornets, everyone knows them, everyone has opinions about them, and they get a lot of attention. I don't think I have to explain this one anymore.

Oklahoma

Old: European Honeybee

New: Giant Walking Stick (Megaphasma denticrus)

The largest insect in the United States. Being a native walking stick, they're less damaging than the imported invasive walking sticks that are heavily controlled.

Oregon

Oregon Swallowtail Butterfly (Papilio oregonius)

Oregon in the common name and in the species name, and also has a stamp!

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Firefly (Photuris pensylvanica)

Pennsylvania in the common name and species name. If fireflies weren't already on this list I would've made sure to include them somewhere.

Rhode Island

American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus)

When I saw this on the list I was worried. American Burying Beetles are one of my favorite insects, but they're extremely endangered now. I also thought they existed more in the midwest, so I was worried I would have to change this one because it violated the "native to the region" rule. But! To my pleasant surprise, not only did their historic range extend to Rhode Island, but there is actually a carefully maintained wild population on Block Island. They estimate between 750-1000 individuals live there, making it one of the few remaining places where the American Burying Beetle still exists. Excellent work Rhode Island!

South Carolina

Carolina Mantis (Stagmomantis carolina)

This is fine. I wanted to give South Carolina the Palmetto bug but they're actually not native.

South Dakota

Old: European Honeybee

New: Golden Northern Bumble Bee (Bombus fervidus)

"Save the bees" should really be focused on native pollinators, many of whom are in decline. There are a lot of species of native bee you can feature as a state insect, with the Golden Northern Bumble Bee being a particularly large and striking species.

Tennessee

Old: Firefly and ladybug

New: Black-waved Flannel Moth (Megalopyge crispata)

Seriously look them up, these guys are adorable.

Texas

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Rainbow Grasshopper (Dactylotum bicolor)

It was really hard to pick an insect for your state. The Texas Unicorn Mantis was a contender but I eliminated it because it's really only found in the southern part of Texas, so it was between the Rainbow Grasshopper and the Eastern Velvet Ant (or Cow Killer). I went with the Rainbow Grasshopper because it's more wide spread and common, and occurs everywhere except the east part of Texas. But the Eastern Velvet Ant only occurs on the east part of Texas, maybe you should get an East and West Texas insect? I also thought more people have probably already heard of the Eastern Velvet Ant than the Rainbow Grasshopper, which is a shame because they're super interesting to look at.

Utah

Old: European Honeybee

New: Mormon Cricket (Anabrus simplex)

Mormon Crickets are not true crickets, and instead closer related to katydids. Their common name comes from an early account of Latter-day Saint settlers in Utah. In 1848, a swarm of Mormon Crickets decimated the settler's crops, so the legend goes that they prayed for relief from this plague of insects. Later that year, a swarm of gulls appeared and ate the crickets, thus saving the crops. This is recounted in the "miracle of the gulls" story. To recognize their contributions, the California Gull is commemorated as Utah's state bird. I thought it was fitting then that the Mormon Cricket be recognized as your state insect.

Vermont

Old: European Honeybee

New: Long-tailed Giant Ichneumon Wasp (Megarhyssa macrurus)

A pretty wasp with an extremely long ovipositor, these wasps are common in deciduous forests across the eastern United States. They can't sting, and instead use their long ovipositor to stab into tree bark and deposit eggs on the horntail larvae that burrow into the trees.

Virginia

Old: Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly

New: Giant Stag Beetle (Lucanus elaphus)

A large stag beetle native to the Eastern United States. Although not as well known as their similar looking fellow stag beetles from Japan, these guys are a lovely chocolate brown instead of solid black. Like most stag beetles, they breed in decaying wood.

Washington

Green Darner Dragonfly (Anax junius)

I imagine this was chosen because it matches the flag.

West Virginia

Old: European Honeybee

New: Appalachian Tiger Beetle (Cicindela ancocisconensis)

This tiger beetle likes hilly terrain. As with all tiger beetles, they can be hard to spot because they run across the ground in search of prey. They are fast! But this can make it more rewarding when you finally catch up to one.

Wisconsin

Old: European Honeybee

New: Phantom Crane Fly (Bittacomorpha clavipes)

Don't believe old wive's tales about crane flies drinking gallons of blood, they are nonbiting. Those striking black and white legs are hollow, and are held out when they fly, making an extremely distinct sight that's been likened to sparklers or snowflakes.

Wyoming

Sheridan's Hairstreak (Callophrys sheridanii)

This is fine.

#insect#insects#state insect#long post#list#text post#entomology#bugblr#invertebrates#invertiblr#inverts#invert

197 notes

·

View notes

Note

While I’m in the inbox, what’s your favourite fishy? Or other aquatic animal? :3

OOOOGH okay i’ve answered this a few times but. i don’t really have a fav so i tend to talk about a different one every time lmao,,, so today it’s gonna be darters which are a recent discovery but oml. i love them so much.

little disclaimer i HOPE this is accurate but i am also just a random fucking kid writing about things i like off the top of my head . yay

first let’s just. let’s look at them for a little bit.

waow……. beautiful

these are mostly males in breeding colors but STILL!! even “plain” they’re still so cute

wow… speckled darters. so beautiful

honestly as someone who started in aquariums and moved on to general fish they’re one of my favs just because of how well they blend function and design. they’re also cool. let me explain.

so first of all they’re members of the perch family.

do we see the family resemblance?? a little??

they tend to live in similar areas (darters are north american native fish!! yay!!! represent!! they’re unfortunately not where i am but at least i get sharks. one day i will travel and find a darter)

there’s all diff kinds and some are very very endangered, they aren’t that well known so some people will just use them as bait. rip.

one thing that’s super cool is how well adapted they are to their environment. so darters tend to live in like, fast flowing streams. to help hold on, they spend most of their time along the rocks and they use their big pectoral fins to kinda get held in place by the current. but something i thought was really neat is that they tend to either have a very reduced swim bladder or none at all!! so when they stop swimming they literally just. sink. it helps them stay put but it’s really funny to me.

they’re also a really diverse group, the areas they live in lead to a lot of allopatric speciation due to how stream systems work. so you get a lot of different kinds in relatively close areas.

oh another thing!! not all of them are in fast flowing areas. there’s ones like sand darters. who like the name suggests just kinda sit in the sand but i love that for them

sand darter. yippee!!

their cool patterns actually help them camouflage, u can kinda see it with the sand darter pic. it’s giving riverbed 🫶

they’re also very fast (get it. darters) and pretty good hunters as well. they commonly eat small aquatic insects (mosquito larvae, mayflies) and also small crustaceans (isopods, small crayfish) oh and also snails sometimes.

also a cool thing is that certain species actually do care for their young!! most of them kinda do the usual fish thing which is. you’re on your own. but some species of darter (i think??? fantail?? don’t quote me) actually will lay their eggs and then the male of the pair will defend them until they hatch. so silly

** I LOOKED IT UP ITS FANTAILS AND ALSO JOHNNY DARTERS

beautiful amazing parents (fantail left johnny right)

OH another thing. darters tend to be very sensitive to changes in water chemistry, so their important ecological indicators of marine ecosystem health. if you have darters your water is probably good :)

anyways. point of all of this is darters are a very cool very diverse group of fish and are also very pretty and i think they’re cool. theres a lot of kinds that are endangered or threatened and i think we should talk about them more to raise awareness. yay!

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Salix discolor (American pussy willow)

The catkins of this pussy willow (Salix discolor) is another sure sign of early spring and they're the only flower I can think of that wears a fur coat. Pussy willows use these silky fibers as insulation to keep their catkins protected in late winter. This species is native to North America in a wide band that runs, coast-to-coast, through southern Canada and the northern lower United States.

Plants know when to flower by measuring the air temperature and the length of day. A brief warm period in the winter will not be enough for pussy willows- they need longer days too. Then, when the timing is perfect - boom they bloom!

As with so many spring flowering trees, willows produce flowers before they leaf-out. Male and female catkins grow on different plants. The appearance of yellow anthers indicates that this one is a boy and it's just about to start producing pollen. Willows are insect-pollinated and this means that hungry worker bees will soon wake up and these pussy willows will immediately get their full attention.

#flowers#photographers on tumblr#pussy willows#spring flowers#catkins#fleurs#flores#fiori#blumen#bloemen#Native plants#my garden#recommendation: "What a plant knows” by Daniel Chamovitz#Vancouver

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solar Farms Have a Superpower Beyond Clean Energy. (New York Times)

Excerpt from this New York Times story:

It’s not your average solar farm.

The glassy panels stand in a meadow. Wildflowers sway in the breeze, bursts of purple, pink, yellow, orange and white among native grasses. A monarch butterfly flits from one blossom to the next. Dragonflies zip, bees hum and goldfinches trill.

As solar projects unfurl across the United States, sites like this one in Ramsey, Minn., stand out because they offer a way to fight climate change while also tackling another ecological crisis: a global biodiversity collapse, driven in large part by habitat loss.

The sun’s clean energy is a powerful weapon in the battle against climate change. But the sites that capture that energy take up land that wildlife needs to survive and thrive. Solar farms could blanket millions of acres in the United States over the coming decades.

So developers, operators, biologists and environmentalists are teaming up with an innovative strategy.

“We have to address both challenges at the same exact time,” said Rebecca Hernandez, a professor of ecology at the University of California, Davis, whose research focuses on how to do just that.

Insects, those small animals that play a mighty role in supporting life on Earth, are facing alarming declines. Solar farms can offer them food and shelter by providing a diverse mix of native plants.

Such plants can also decrease erosion, nourish the soil and store planet-warming carbon. They can also attract insects that improve pollination of nearby crops.

Pollinator friendly solar can pay off for business, too, potentially saving money and giving projects an edge for approval at a time when communities are increasingly wary of vast solar farms. Developers are taking note.

But there’s a broad spectrum of pollinator friendliness and little agreement on what efforts should count. Standards are often nonexistent. Some big projects are limiting pollinator habitat to tiny corners of their sites. Ecological value varies widely.

Communities may not understand the difference, and corporate marketing may exaggerate. That’s led to accusations of greenwashing.

Pollinator habitat on solar farms is “a serious work in progress,” said Scott Black, executive director of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, a nonprofit group that is working on an effort to bring some clarity by certifying solar sites.

“It’s not fair if some people are truly stepping up to do this right and another company is barely doing anything and saying they’re pollinator friendly,” he said.

“If you build it, will they come?” he asks in his research. So far the answer is a resounding yes, if you grow the right plants.

In a study published late last year, his team found that insect abundance had tripled over five years on test plots at two other Minnesota solar sites. The abundance of native bees grew twentyfold.

The results come amid a global decline of wildlife that leaders are struggling to address. Some of the most well-known insect species are in trouble: Later this year, the federal government is expected to rule on whether to place monarch butterflies on the Endangered Species List. North American birds, for their part, are down almost 30 percent since 1970.

But at this site, called Anoka County Solar, acoustic monitoring has documented 73 species of birds, presumably attracted by the buffet of seeds and insects. Some build nests in the structures supporting the panels.

Mammals are showing up, too. Mr. Walston checked a trail camera before leaving, hoping to discover the occupant of a remarkably large burrow: A fox, he thought, or a badger. No luck.

(It’s trickier to make solar sites friendly to large wild animals, in part because developers are nervous to let them near expensive infrastructure, but efforts are underway there, too.)

What makes this meadow possible is the height of the panels. A prairie restoration firm had told ENGIE, the owner and developer, that taller panels would allow for a sharp increase in native vegetation species, providing much more ecological diversity, said John Gantner, the director of engineering and delivery for ENGIE’s smaller-scale sites.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 2nd, 2024

Thick-legged Hoverfly (Syritta pipiens)

Distribution: Native to Europe, but found throughout Eurasia and North America.

Habitat: Occur wherever there are flowers, but most common around human habitations; common habitats include farmland, gardens and parks. Larvae are most common in rotting organic matter such as compost, manure, silage, and occasionally cadavers.

Diet: Larvae feed on decaying organic matter, while adults feed on many types of flowers. Their most common food plants are water-willow, white vervain, American pokeweed and candyleaf.

Description: The thick-legged hoverfly is called so due to their overdeveloped hind legs. These insects can sometimes be pests, as they occasionally feed on ornamentals, but are generally considered beneficial because they pollinate many common flower species. They also act as bio-indicators, especially to demonstrate the effects of environmental changes on pollinators.

Hoverflies are very agile fliers, and are often found hovering near flowers. This species, however, is very rarely found flying more than a metre above ground level. When they encounter another fly, males will sometimes circle around them; if they're male, this often results in the two males circling eachother, and if they're female, the male may dive at her at an acceleration of up to 500 centimetres per second squared in an attempt to initiate copulation.

Images by Joaquim Alves Gaspar and Stephen Luk.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's learn more about the impressive but potentially invasive ornamental plant introduced from North America, the Canadian Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis).

Despite its invasive nature, Canadian Goldenrod is an important food source for a wide range of insects including the Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus). Cattle and horses as well as deer can safely eat Canadian Goldenrod, and the flowers are not associated with allergies in humans since they do not produce airborne pollen. The plant is used in traditional herbal medicine by indigenous Americans for fevers and respiratory illnesses.

This gold-medallist invasive species has become an ecological menace in Europe and East Asia, where Chinese experts blame it for the extinction of over 30 species of native Chinese plants. In the UK, this admittedly attractive plant was introduced as an ornamental in the 19th century but it soon fell out of favour with gardeners because it was too aggressive.

I am unsure whether the Canadian Goldenrod in my garden is a survivor of a old garden design or if my late Dad added it to the garden, but it is confined as a specimen to a small patch in my garden. New plants are removed if found elsewhere on my property, so it won’t win any gold medals for invasiveness here.

#katia plant scientist#botany#plant biology#plants#plant science#yellow flowers#flowers#wildflowers#goldenrod#canadian goldenrod#plant identification#cottage garden#plant facts#north american plants#solidago#plant scientist#plantblr#gardening

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

[A] luscious Owari Satsuma citrus tree, whose species was originally imported from Japan, currently experiencing the ravaging effects of an aphid infestation. [...] Where did they come from? [...] And a question that nineteenth- and twentieth-century individuals may have added is, who is to blame? Jeannie N. Shinozuka’s monograph, Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 [...] [examines] such human and nonhuman interconnections [...] [and] meditates on such questions in the historical setting of the American empire, including its transpacific borderland.

Toward the end of the nineteenth and through the twentieth century, the already present anti-Asian racism in the United States was infused with a conservationist attitude of sustainable yield and efficient use of the vast but vanishing natural resources of North America.

---

Unsurprisingly, these racial anxieties appeared just as the American empire expanded well beyond the continent’s borders. The economic threat of chestnut blight or citrus scale played into a native invasive binary that conveniently placed blame for the species’ decline, along with pest and disease introductions, on poor and immigrant groups, while excluding and erasing a longer colonial history of importations of destructive plants and animals by colonial and antebellum planters. These fears were founded not just in the economics of decline, based on a fear of the threat posed to cash crops often grown on increasingly large-scale farms, but also in jealousy surrounding agricultural innovations [...] of certain immigrant farmers [...] in a society plagued with racial anxieties of a so-called yellow peril. Paradoxically, wealthy American citizens interested in beautifying landscapes often held an orientalist fascination with a fetishized and consumable version of a Japanese countryside in the form of tea gardens. [...]

---

The work also discusses the role of newly ordained technocratic officials in giving supposed scientific validity to attitudes toward plant, animal, and human invaders from the Orient.

Plant biologists such as [D.F.] and entomologists [...] were on the forefront of crusades to prevent economically damaging insects and plant diseases from entering the borders of the United States and “degrading” the native stock. Many of these individuals, like [D.F.], were closely associated with some of the leading eugenicist organizations, for example, the American Breeder’s Association, within the United States. Their efforts at plant quarantine culminated in Plant Quarantine Number 37, or PQN 37, a law intended to prevent diseases and infection from foreign animal and plant bodies. This law set a precedent for similar policies regulating humans perceived as alien, including the Immigrant Act of 1924, which limited immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, while completely excluding individuals from Asia. Similarly, officials, [...] [entomologists] included among them, seized and destroyed the property of Japanese immigrants [...].

---

Shinozuka’s work is [...] a contribution to environmental history and Asian studies, [and] it is also a fresh conversation on borderlands and the role that [...] migrant groups, played in such porous places as the US Mexico border and Hawaii, the Pacific gateway to the US empire. Both domains offered opportunities to immigrants and scientists alike [...]. [I]mmigrant labor provided muscle power to corporate-owned American sugar plantations in Hawaii while also experiencing accusations of importing such damaging insects as the termite or Oriental beetle. What Shinozuka makes clear is that while these insects may have originated in southeast Asia, their spread was enabled by the context of American colonialism and empire. The trifold factors of urbanization, industrialization, and monocrop agriculture, all promoted in the interest of American business and marketed as a modernization effort in supposedly backward places like Hawaii, created the perfect circumstances for insects to swarm and disease to spread.

---

All text above by: Jacob Gautreaux. "Review of Shinozuka, Jeannie N., Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950". H-Environment, H-Net Review. August 2024. At: h-net dot org slash reviews/showrev.php?id=60450. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

hii! im trying to get over my phobia of bugs, so i decided i would try and see the good side of them :]

if its okay, could you share with me some of your favourite facts about bugs, and/or some cool images of bugs? no pressure, though! ^_^

oh, i'm so happy and proud of you anon! as a very avid bug lover, i always love hearing people try to be more open to them, even just slightly!!

a few fun facts:

a single dung beetle can move about 1141 times it's own weight! it's like if a human pulled SIX double decker buses, all on their own!

male stoneflies are like, the gym guy of the bug world - sometimes they'll do pushups as a way to impress a potential mate!

male giraffe weevils use their looong necks to fight eachother, much like actual giraffes!

some tarantulas have been found to essentially keep frogs as pets! the spider will offer safety and protection to frogs while a frog will eat any insects that may try and attack the spiders eggs!! (this habit has also been seen in some other spider species too!)

and here's some photos!!

rosy maple moth (dryocampa rubicunda), also known as the great silk moth! this species is a small north american moth. it's recently surged in popularity due to it's adorable colours and tiny size, even having plushies made after it!

sources: image one, image two

humming bird hawk moth (macroglossum stellatarum) is named for it's resemblance to the humming bird as they feed on the nectar of tube shaped flowers using their long proboscis while staying in the air. this species is found across temperate areas of eurasia such as portugal, japan and spain!

sources: image one, image two

cecropia moth (hyalophora cecropia), aka a giant silk moth is the largest native moth found in north america! their wing can even span up to five-seven inches (13-18 centimeters) wide!

source: image one, image two

the peacock spider (maratus volans) is a jumping spider native to australia (my country!!) with only one species residing in china! much like the bird they're named after, peacock spiders will display their bright feathers as a mating technique, paired with a dance! it is widely believed that females will kill a male if they find their dance unsatisfactory but this is fortunately, for the men, untrue! she will instead ignore him or move her abdomen side to side to display her disinterest. the maratus sarahae (first image) is one of the largest species! image two is a maratus azureus!

source: image one, image two

sabertooth longhorn beetle (macrodontia cervicornis) are some of the largest beetles in the world! it spends most of it's life in a larval stage which can last up to 10 years!! after which it will only live a few more months in which it will reproduce. sabertooth larvae are planted under the bark of dead or dying softwood trees as they will burrowing inside it!

source: image one, image two

i hope this was enjoyable!! i had a lot of fun doing this hehe

#playtime answers#sfw agere#age regressor#age regression#agere blog#sfw interaction only#sfw agedre#agedre#sfw agedre blog#agedre blog#sfw age regression#bug agere#agere bugs#bug#bugs#insects#entomology#tw spiders#jumping spider#arachnophobia#arachnids#spiders#cw spiders#cw arachnophobia#cw arachnid#tw arachnophobia#tw arachnids#tw bugs#tw insects#cw bugs

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ten-Lined June Beetle - Polyphylla decemlineata

The stripes along this Beetle's shell are very prominent, but not necessarily distinct as there are a few similar-looking species. It does make for a beautiful find from Canada's west coast (in Squamish). My dear friend found it sheltering inside his car. Presumably it needed a ride to Vancouver and public transit just wouldn't do. While I'm kidding here, insects do on occasion get transported to new locations via road vehicles or overseas shipping. Such activity can introduce species that are normally considered harmless within their native range into an ecosystem that isn't prepared for them! This can result in pest status, or being labelled an invasive specie should their habit become too detrimental. This specie is fortunately not an invasive one here, as it is native to western North America. It instead has status as a pest of orchards, whereby the adults feed on fruit tree leaves while the larvae feed on their roots! Naturally, this can warrant monitoring of crops to prevent extensive damage, especially for the larvae who may inadvertently destroy young trees during their time developing beneath the soil. Today's specimen has pupated and left that life behind in favor of a more herbivorous routine. Despite the weight of her armored shell, this Scarab is quite capable of strong flight.

For a North American comparison between similar Beetles, my friend described this insect's behavior (when he found it) as similar to that of May Beetles (Phyllophaga spp.), which are more common in my neck of the woods. Both genera seem to have a fondness for flying into lights at nighttime. There is somewhat of a resemblance as well, especially with the soft fluff on the Beetle's underside. The Ten-Lined June Beetle is far more glamorous, however. There's a lack of confirmation on this, but it's possible that those bold stripes gave this Beetle its other common name: the Watermelon Beetle. I'd be hard pressed to say that their feeding habits created that name since watermelons grow on vines rather than trees (the harvest would be much more precarious if that were the case). Finally, should you find a Beetle similar in appearance to this one, take note of its antennae. This individual is likely to be a female as her antennae is reduced in size, but it can still fan out (from a club shape) to better catch scents on the breeze. Male Ten-Lined June Beetles have enormous, (curved) paddle-like antennae jutting out from their heads! Genuinely, you can't miss them! Although particularly ornamental in design, they aren't useful as weapons to batter away rival insects. They elaborately fan out to catch the alluring scent of a female Beetle's pheromones, but I wonder how the male's flight stability and direction are affected by the larger antennae.

Pictures were taken on August 5, 2024 in Squamish with an iPhone 12.

#jonny’s insect catalogue#insect#beetle#ten lined june beetle#scarab beetle#june bug#coleoptera#watermelon beetle#squamish#sḵwx̱wú7mesh#august2024#2024#nature#entomology#invertebrates#arthropods#photography#animals

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I meant to post this earlier in the month, but in case you missed it, the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is going to be listed as a threatened species under the United States Endangered Species Act. It's a bit disappointing for those of us pushing for full endangered status because a threatened species doesn't receive as complete a set of protections. But it's better than nothing.

Monarch butterflies have seen a precipitous drop in numbers over the past few decades, to include both the western and eastern North American subpopulations. When I was a child in Missouri in the 1980s they were a common sight in our garden; that's not the case any more. The western subpopulation, found west of the Rocky Mountains, is much smaller than the eastern and so is at even greater risk of extinction.

As with most endangered species, habitat loss is the leading cause of population drop. While an adult monarch butterfly can feed from a variety of flowers, the caterpillars can only eat the leaves of milkweed (Asclepias spp.) No milkweed means no monarchs, and as open fields and meadows are increasingly paved over or turned into housing developments with sterile grass lawns, the monarchs have fewer and fewer places to lay their eggs. Climate change is also having a negative effect on monarchs; many died in last January's freezing temperatures that hit their overwintering sites in Texas and Mexico, and temperature variability also affects monarch reproduction.

While the ESA threatened listing is a move in the right direction, it's not enough. Existing monarch habitat must be protected, and lost habitat restored as much as possible. Even little pockets of native milkweeds for caterpillars, and other native wildflowers for the adults, can create important oases, so planting these species in your yard or on your porch can help monarchs and other native insects. Avoid non-native, tropical milkweed species, as these can host dangerous parasites. And keep pushing U.S. Fish and Wildlife to give monarchs full endangered status, while supporting organizations that advocate for these butterflies, like the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

#monarch butterflies#butterflies#insects#invertebrates#arthropods#nature#wildlife#animals#environment#conservation#scicomm#endangered species#extinction#animal welfare

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spectember D27: Revamp the Dinosauroid

The end of the Triassic propitiated finally the dominance of dinosaurs in the next period with the rupture of the large supercontinent Pangea, though in this timeline something pushed further the fragmentation of the continent, and instead of just opening the rift of the Atlantic, it multiplied across Africa and a section of south America, making the Tr/J mass extinction more severe and killing out many more species of dinosaurs, so now the Jurassic was no longer dominated by the animals we have in our timeline, instead we get a strange variety of large dinosaur-like crocodiles, many sauropodomorphs that diverged from the smaller species that survived and never went into the same trend of gigantism as in our earth, many synapsids and so on. At the end of the late Jurassic a lot happened with the new order, within some of the second radiation of sauropodomorphs included varied carnivorous carnosaur-like species, medium size coelurosaur-like omnivores and smaller herbivores that look like silesaurs; from the omnivore lineage that have expanded in varied niches would rise a branch of semiaquatic species that resembled something like a scaly penguin with hands, long finger and claws, with short robust tails, shorter necks and longer heads with narrow keratinized mouths.

They are remarkable as many other animals of this world, through one particular species seems to have started a peculiar evolutionary trend in the last 10 million years.

For the reader, we will refer to this species as the Shagoids, a species originated from 50 cm long aquatic sauropodomorph descendants that wandered on the estuaries of the now more fragmented north Africa/south American region, their ancestors were more of a mix of a cormorant with an otter as unlike the rest of its own family this belongs, as one main feature of these are they still functional forelimbs, these still preserved functional arms and hands that helped them to manipulate their prey of crustaceans and mollusks. Over time these developed strategies to break down their prey shell, including the habit of picking and using stones which choose appropriately for this task. This behavior was passed on to new generations, learned and properly helped them to get food with less effort, the food quality increased brain energy, brain size also increased and so their skills were forged much more adequately.

It was on matter of few million years the Shagoids lineage abandoned their swimming lifestyle and became mostly semi aquatic coastal dwellers, living in the shores and just entering water to hunt their food rather than spending most of their time there. As social animals they formed hierarchy groups, formed by the head of a dominant female around minor males that could either mate with her or just serve them, as well many other younger individuals, matriarchs often had the duty to select and organize hunting and spending of food, as well regulate reproduction and mating between their lower family, as she normally is the eldest of the group, and only another female of the same blood can turn into a elder matriarch of if mated by the son of the elder, this perhaps was the moment they gained proper sentience as how they defined a cultural and social structure.

It seems at the end rathe in a sudden change of sea level in the last 3 million years did the final push on their evolutionary journey, as most of the Shagoid populations got stranded within the main continent with almost no way to find new connections to large water bodies, in other situation their species would have die for starvation, but at that point they were already adapted to feed on other food sources, from tubers, insects and small animals, being able to cook them using fire they managed to craft, and so properly passed the harsh time with the loss of a chunk of their population over the sudden change.

When the Shagoid expanded and found again large water bodies far from their native regions, they really have changed considerable from their ancestors, as their closest relative was a sort of strange loon like reptilian species wandering in the coasts, these were more like limbed penguins with long arms and tridactyl hands, which the third finger being a derivation of the 4th an 5th clawless digit fused into one, their short legs lost their webbed feet a while ago and are more adapted for walking, their head still preserve the characteristic seabird like shape but their teeth have changed in shape to be generalistic omnivore, with a large head which houses the most intelligent brain in the planet.

Over the last thousands of years, they have been becoming more and more prone to establish permanent settlements populated by hundreds of them much more different of their wandering tribes, often farm plants and even carry some animals for domestication.

For the first time in their history they are in the pathway of civilization… who knows what will happen next, either the Shagoid can remain like this until their extinction, or they will start building towards the sky and beyond.

#speculative evolution#alternative evolution#triassic#jurassic#sauropodomorph#dinosauroid#sapient#spectember

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yesterday, I went to a beach! I say “a” because there are actually a lot of private and public beaches in my area (as a result of living practically on top of Lake Michigan). While the beach was deserted of vacationing humans, I was delighted to find a number of different insects going about their business!

In order, we have:

A seven spotted ladybug navigating some gravel. There were a lot of ladybugs on the beach, and I’m not entirely sure why. Perhaps they were hunting for aphids that might be lurking among the leaf debris scattered across the beach.

A bean leaf beetle, taking a moment on the side of a tiny sprout in the sand. Bean leaf beetles are plant-eaters, and are considered pests by farmers due to their voracious appetites and their preference for vegetable plants.

A multicolored Asian ladybeetle and a Spotted Cucumber beetle crossing paths. I’ve talked about Asian ladybeetles at length in the past, and the Spotted Cucumber Beetle is remarkably similar to the bean leaf beetle, both in appearance and in appetite. Strangely, spotted cucumber beetles don’t subsist solely on cucumbers, which I suppose explains their presence here.

*Disonycha leptolineata* (no common name), a species of flea beetle, which get their name from their remarkable jumping abilities. Flea beetles are closely related to leaf beetles, which makes sense given that their names are anagrams. The fact that this one lacks a common name illustrates just how vast the insect world is: there are simply too many insect species, and not enough time, to give all of them a common name. If I were to name this guy, I’d go with something cool—perhaps ‘painted firefly leaf beetle’.

Spotted pink lady beetle. A large number of these dudes were crawling frantically around the beach, searching for nothing in particular. Perhaps it was their mandatory exercise break.

Green Immigrant Leaf Beetle Weevil. As its name indicates, it is not native to the United States, having arrived from Europe in the early 1900’s. Despite the reputation that nonnative species of insect have gathered for themselves (thanks, spotted lantern flies) these little weevils do not appear to have had a major impact on North American ecosystems, though I doubt this was out of the goodness of their hearts—insects cannot tell the difference between right and wrong.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post Human Studies: Homo Florophagi

Many post human species have rather natural origins: a colony of human stranded on a world over thousands of years into the millions adapts to their circumstances, high gravity causes increases in bone density or toxic atmospheres creating more able to filter out toxins at the cost of low oxygen intake.

Homo Florophagi or the Human Locust are in fact not the result of quiet Evolution taking its course upon the human form distorting it into whatever brilliant new arrangements are possible. No the human locust are examples of homo sapiens’s folly, the idea that all outcomes can be predicted. That with enough information anything can be accounted for. Because the one thing that was not accounted for with the genesis of these locusts was human error.

To err is human too forgive is divine. The creators of the human locusts were profoundly human. When mankind first left Earth one of the questions that arose was how best to suit planets the ecological state of terra formation. Dead worlds or worlds without any noticeable atmosphere and few traces of native life contatry to most popular beliefs where some of the easiest to be settled during the spring time of mankind. Then came the question of those that already had complex ecosystems. Another common misconception is that mankind's colonization efforts were United under one single entity. This is incorrect mankind has never been united and with the events of the Fall of the Galactic Order it is very unlikely that they will ever be as they are now scattered to the stars.

To make a long diatribe short one of the proposed solutions to worlds with already established ecosystems were Homo Florophagi. An offshoot of baseline humanity mixed with xenotypical, chortoicetes terminifera, coptotermes formosanus, ornithorhynchus anatinus, as well as other similar species.

The base idea behind them was this: if we can introduce a pest to a world that has a virgin ecosystem that is so divergent from Earth it would make sustained life more difficult than once the ecosystem is sufficiently destabilized invasive species can be introduced to restabilize the planet in a more earthlike direction. The question then went to what is the basis of most ecosystems and that went to the plant. Now the plant is a life form that has emerged again and again across the universe it is seemingly one of the simplest forms of complex life to emerge.

Thus the florophagi - a species with the relative intelligence of humanity, the eusocial behavior of most insect species mixed into it, shortened gestational periods in leathery eggs, and the ability to devour any and all plant life it finds. Its face, limbs, and digits work extended it's teeth reduced more to protruding clicking buck teeth. The human locust no longer walk upright for prolonged periods of time however the increased strength given to most of its limbs allows it to climb on surfaces in search of food long denied to bipedal mankind. Jaws that one might find in North American Beaver with multiple lines of molars to grind down food forming a jawline that is constantly growing new teeth as old ones are worn out. Because of the way their eggs function as an added benefit they are born hungry.

A human locust will emerge ready to devour anything in the vicinity including other eggs and then swiftly move on to join the rest of its colony in devouring whatever plant life it can find.

Such a destructive species in field testing did in fact destabilize most of the ecosystems it was present in. Once all available plant life was consumed, colonies would go on to devour animals, and then each other. Within approximately one decade, a colony of one hundred expanded to one three hundred million and had completely rendered barren landmass the size of Old North America. Within a year of the last other food sources being gone, the colony collapsed in on itself and the example specimens functioning exactly as intended. They were born hungry and they would die hungry.

The human locust would in most cases be considered arousing success by its creators sending it to frontier worlds waiting for the population boom and then collapse and then stepping in once all were confirmed dead to rebuild the world in Old Earth's likeness. Many other human factions objected to the use of the human genome in such a way but the Creators only pointed to their successes.

Until a colony got loose.

AlI it took was one cage improperly closed.

And all those hubris the creators of this monster and it is difficult to call them a monster for though they are destructive it is not by choice and it is not their fault they did not desire to be created as such but the one thing that their creators forgot and all their humorous was that they had given their children human intelligence. The ability to exchange information, the ability to speak and dirt though much changed by the protruding jawline, jutting joints, and hairless skin.

All it took was one colony getting loose on a ship that they were able to observe how to pilot and they would never go hungry again.

To this day the descendants of the original homo florophagin remain a pest across two galaxies.

I cannot blame them.

4 notes

·

View notes