#national Bolshevism

Text

“Alyoshka was not yet a Catholic then, but he no longer wore a beard. He had just been laid off as a guard, he had surrendered his nightstick and uniform and become once more the mustachioed and dark-eyed Alyoshka Slavkov, cheerful despite a bad limp, lover of booze. Alyoshka fed me sauerkraut and sausages, his unvarying diet, and sat down to translate a document I had brought. Entitled "Memorandum," the document expressed the hopes and dreams of what we called "the creative intelligentsia"—of Alyoshka and myself and a great number of other artists, writers, filmmakers, and sculptors who had emigrated from the USSR and whom no one here needed one fucking bit.

Alyoshka translated, and I sat in an old chair, its upholstery worn shiny, and thought about our document and our intrigues. "A drowning man's effort not to drown," I thought. Two pages. To be sent to Jackson, Carey, and Beame. As if they would help us with our art. Those demagogues had needed us, however, while we were over there. Here they shoved us on welfare so we wouldn't bitch. Okay, Ivan, have a spree, enjoy your freedom.

Cold-blooded Americans, they're so fucking smart, they advise the likes of us to switch professions. Just one thing—why don't they switch professions themselves? When a businessman loses half his fortune he throws himself off the forty-fifth floor of his office building, he does not go to work as a guard. I could have conformed in the USSR, why the fuck come here to do it? That was all the Soviet regime wanted of me, to change my profession.

A fine emigration we are, I went on in my thoughts, the most frivolous one yet. Usually only the fear of starvation or death can force people to leave a place, abandon their homeland, knowing that they may not be able to return, ever. A Yugoslavian who leaves for a temporary job in America can return home to his country, we can not. Never again shall I see my father and mother; I, little Eddie, am firm and calm in this knowledge.

It all started with Messrs. Sakharov, Solzhenitsyn, and company, who turned us against the Soviet world without ever having laid eyes on the Western world. They were prompted not only by specific purposes—the intelligentsia were demanding a part in governing the country, demanding their share—but also by pride, the desire to advertise themselves. As always in Russia, moderation was not observed. They may have been honestly deceived, Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn, but they deceived us too. Whatever the case, they were "dominant influences." So powerful was the intelligentsia's movement against their country and its system that even the strong could not resist and were swept along. So we all shag-assed over to the Western world as soon as the opportunity presented itself. We shag-assed over here, and having seen what the life is like, many if not all would shag-ass right back, but it's impossible. The Soviet government is not nice.

Fucking smart Americans, they advise men like Alyoshka and me to change professions. Where am I to hide all my thoughts, feelings, ten years of living, books of poetry? And me myself, where am I to hide refined little Eddie? Lock him up in the shell of a busboy. Bullshit. I tried it. I can no longer be an ordinary man. I am spoiled forever. Only the grave will reform me.

Eventually American security forces are going to have trouble with us. After all, not everyone conforms. In a couple of years look for Russians among the terrorists in liberation fronts of every description. That is my forecast.

Change our professions! Can the soul be changed? Knowing definitely what he is capable of, is it everyone who can suppress himself here and live the life of an ordinary man, laying no claim to anything, when he sees around him money, success, and fame, all of it largely undeserved, when he knows from experience both here and in the Soviet Union—and in this case the experience is identical—that he who is obedient and patient receives all from society, that he who sits on his butt all day and curries favor gets it all.

The brilliant inventors of vegetarian sandwiches for Wall Street secretaries can be counted on the fingers of one hand. For the most part, people arrive at success here just as they do in the USSR, by obedience, by wearing out the seat of their pants in their own or a government office, in boring daily labor. That is to say, civilization is constructed in such a way that the most restless, passionate, impatient—as a rule the most talented, who seek new paths—break their necks. This civilization is paradise for the mediocre. We thought the USSR was a paradise for the mediocre, we thought it would be different here if you were talented. Fuck no!

Ideology there, business reasons here. That is roughly true. But what difference does it make to me exactly why the world doesn't want to give me what is mine by right of my birth and talent? The world calmly gives it—a place, I mean, a place in life, recognition—to the businessman here, to the party worker over there. But it has no place for me.

Fucking shit! I'm being patient, world, very patient, but some day I'll get fed up. If there's no place for me, and for many others, then who the fuck needs a civilization like this?

That last thought I expressed aloud to Alyoshka Slavkov, who is far from agreeing with me in everything. He is drawn to religion, inclined to seek salvation in religious tradition; on the whole he is calmer than Eddie, although he too has storms raging within him, I think. He dreams of becoming a Jesuit, and I mock his Jesuitism and predict that he will participate in the world revolution along with me, a revolution whose goal will be to destroy civilization.

"And what would you build in its place, you and your friends in the Workers Party?" Alyoshka said. For some reason he lumps me in with the Workers Party, to which I have never belonged. I have merely been interested in it, as in any other leftist movement. I did become more intimate with Carol and her friends than with members of the other parties, but that was pure chance.

"The hardest thing of all," I told Alyoshka, "is to overthrow this civilization, tear it out by the root so that it cannot revive as it did in the USSR. To overthrow it once and for all is to build something new."

"And what will you do about culture?" Alyoshka asked

"This feudal culture," I said, "which inculcates wrong interpersonal relationships that originated in the distant past under a different social order-what will we do about it? We'll fucking annihilate it. It's unhealthy, it's dangerous with all its little tales of good millionaires, wonderful police who defend citizens from bestial criminals, magnanimous politicians who love flowers and children. Why is it that not one of these stinking authors—notice, Alyoshka, not one—will write that crimes, the majority of them, are generated by civilization itself? If a man kills another and takes his money, it's certainly not because he likes the color and crunch of those scraps of paper enough to murder another. He knows from his society that among his fellow countrymen those scraps of paper are God, they'll bring him any woman he wants, and bring him his grub, and deliver him from exhausting physical labor. Or a man kills his wife for betraying him. But if there were other customs, a different ethic, and interpersonal relationships were measured only by love, then why would he kill for unlove? Unlove is a misfortune, it's to be regretted. Television always shows families, and gentlemen in suits. But that's already on the way out. The gentlemen in suits are on the way out, and the wild wind of new relationships, ignoring all police measures, all religious barriers, howls over America and the whole world. The gentleman in a suit, the gray-haired head of the family, is suffering defeat after defeat, and soon, very soon, he will no longer be able to govern the world. The husband and wife who joined together in order to have a more peaceful, economically more advantageous life—not for love, but at the decree of custom—theirs was always an artificial arrangement and engendered a host of tragedies. Why the fuck preserve an obsolete custom?"“ - Eduard Limonov, ‘It's Me, Eddie’ (1979) [p. 148 - 151]

#limonov#eduard#eddie baby#eddie#russia#russian literature#russian punk#new york#soviet art#post soviet#soviet#ussr#national bolshevism#civilization#civilisation#culture#aleksandr solzhenitsyn#art#artist#freedom

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

its been a while hasnt it

#mod spice#art#centricide#jreg#centricide fanart#jreg fanart#jreg pinkcap#centricide pinkcap#jreg nazbol#centricide nazbol#jreg pink capitalism#centricide pink capitalism#jreg national bolshevism#centricide national bolshevism#jreg pink capitalist#centricide pink capitalist#i forgot how much of a doozy these tags can be

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

noninsignificant number of patriotic liberals could get behind falangist nationalism tbh (itself a legacy of orteguista liberalism), based not on racial or religious exclusion but on the notion of spain as an idea, a mission, a set of values

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Georgian affair#Joseph Stalin#Vladimir Lenin#Georgian ssr#nationalism#bolshevism#Bolsheviks#Soviet union#USSR#Грузинское дело#socialism#communism#marxism#history#Ordzhonikidze#Polikarp Mdivani

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey everybody. we're glad everyone's been enjoying politics! to keep things interesting and keep the meta balanced we'll be implementing these new ideologies in 2024:

peronism with chinese characteristics

twitch streamer philosopher kingship

absolute military junta (sortition-based)

hunnic nationalism

anarcho-sharia

marxism-leninism-maoism-klobucharism (primarily klobucharism)

three chinas policy

antitranshumanist trans humanism

puppygirl rights activism

representative shogunate

pan-midwesternism

tetsuya yamagami thought

liberal arts college technate

discordian-thelemite lebanon-style religious powersharing

armed insurrectionary incremental reformism

narcotheocracy

sex-positive feudalism

social democratic taliban entryism

badism-worseism

believing in judeo-bolshevism but thinking it was a good thing

ineffective altruism

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Uses of History, 31 – Mussolini and Fascism, 3

Fascism is a religion. The twentieth century will be known in history as the century of Fascism. – Mussolini

https://www.brainyquote.com/authors/benito-mussolini-quotes

(Photo credit – The Guardian – Mussolini inspects “Volunteers” going to Spain)

While the 20th Century was not the century of Fascism in the sense Mussolini intended (as the dominant force in world affairs), Fascism certainly…

View On WordPress

#Axis#Axis Powers#Bolshevism#Hitler#Hitler and Mussolini#League of Nations#Marxism#Mussolini#Spain#Spanish Civil War

0 notes

Note

Maybe this is too broad, but wondering if there's a better term than "conspiracy theorist" to describe some large figures in the ongoing national discourse? Not that "fluoride in the drinking crowd" were serious thinkers or total harmless, but am I alone is finding "conspiracy theory" too quaint and mild to describe how mainstream rather fringe these things are and also how totally evidence-free and something just plain dumb they can also be?

I don’t think conspiracy theories have ever been quaint and mild.

Think about the history of antisemitism from medieval blood libels to 19th century theories of Jewish financial cabals to the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” dreamed up by Tsarist agents-provocateur that took the theory global and spawned untold numbers of imitators, to Hitler’s invention of “Judeo-Bolshevism” that married traditional antisemitism to anti-Communism and nationalist populism. Conspiracy theories one and all, but fully capable of spawning pogroms and fascist dictatorships.

Likewise, we think of Anti-Masonic or Illuminati conspiracy theories as self-evidently ridiculous and harmless, but we forget that they were used by cultural conservatives in church and state to wage culture wars on the Enlightenment, liberalism, secularism, democracy, every revolution from America to France to 1848 and beyond, feminism and almost every social movement of the 18th and 19th century. People died or were surveilled or were sent to prison, political parties were formed or banned, and conservatism itself was founded in the name of “poisoning the minds of the lower orders” to inoculate them from the influence of secret societies.

As Dan Olsen has shown, even seemingly benign conspiracy theories like the JFK assassination cover-up or the Moon landing was faked or the earth is flat can hide much more malign motivations, just waiting for the opportunity to radicalize and proselytize:

youtube

#history#historical analysis#cultural history#conspiracy theories#conspiracies#anti semitism#illuminati#freemasons#flat earthers

144 notes

·

View notes

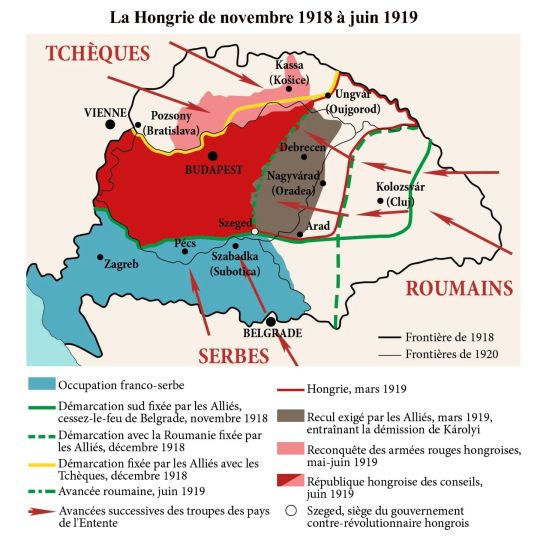

Photo

Hungary in 1918-1919

Nicolas de Lamberterie, 2020

"Történelmi atlasz - Középiskolásoknak", József Kaposi, 2016

by cartesdhistoire

Defeats on the front, rising prices, and the agitation of foreign peoples created a troubled situation in Hungary, and in January 1918, a general strike paralyzed activity in Budapest. At the instigation of certain former Hungarian prisoners freed from Russia by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and converted to Bolshevism, mutinies took place, and a new general strike of a political nature extended to the entire country on June 20.

On the night of October 29 to 30, Count Mihály Károlyi became the head of government of a de facto independent Hungary: it was the Aster Revolution which established the Hungarian Democratic Republic (November 16).

The head of the inter-allied military mission, the Frenchman Fernand Vix, demanded a retreat of the Hungarian armies by 100 km, an ultimatum which led to the fall of Károlyi and the formation of a government in the hands of the journalist Béla Kun, who had returned from Russia where he had been a companion of Lenin: the Hungarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed on March 21. To face the armed offensives of its neighbors, the government formed a People's Army which, after some successes against the Czechs, was defeated by the Romanians who advanced on Budapest. Béla Kun left the capital on August 1, two days before the arrival of Romanian and Serbian troops supported by French forces (missions led by Berthelot and Franchet d'Espèrey, respectively).

The Bolsheviks' rise to power was poorly received in the provinces and among the Allies. In the southeast of the country occupied by French troops, a national government was formed in June in Szeged whose army was entrusted to Admiral Horthy who, at the time of Béla Kun's fall, already controlled the entire South and West of the country. After negotiating the departure of the Romanians with the Entente, Horthy entered Budapest at the head of his army on November 16. The assembly elected him regent of Hungary on March 1, 1920.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

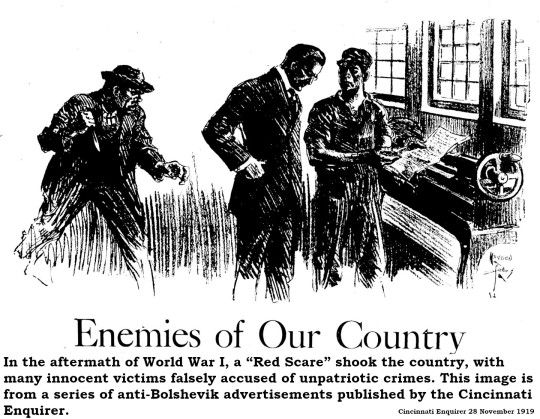

A Secret Organization Scoured Cincinnati For Bolsheviks But Found Only A Schoolgirl

It is inevitable, once you have created an organization to snitch on your neighbors, that you will find neighbors to snitch on. So it was with the American Protective League.

The American Protective League emerged from the jingoistic fervor that gripped America during the First World War. According to Steven L. Wright [Queen City Heritage, Winter 1988]:

“The American Protective League (APL) organized in Chicago in March 1917, had units in 600 cities and a membership roster of nearly 100,000. And by 1918 membership had grown to 250,000. Its membership consisted of bankers, businessmen, attorneys, chamber of commerce leaders and insurance company executives. Because of their ‘high’ position, they easily obtained information concerning ‘troublesome’ citizens, especially those who opposed the draft.”

Nationally, the APL received quasi-legal status as an affiliate of the federal Department of Justice. Locally, the Cincinnati branch of the APL was instrumental in arresting thirteen socialists who were charged with treason for circulating literature opposed to the military draft. Those charges would eventually be dismissed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1924.

With the conclusion of hostilities, the APL technically disbanded on 31 January 1919 when Gerson J. Brown, the wholesale tobacconist who led the Cincinnati chapter, turned over all League records to Calvin S. Weakley, special agent of the Department of Justice. Even though the organization ceased to exist, however, some members insisted on carrying on the work of the League. Germany’s surrender had revealed, according to these men, a new and even more sinister enemy working to conquer America – Bolshevism. John L. Richey, head of the Cincinnati Association of Credit Men, announced through several very public speeches that his position as chief investigator of the American Protective League had revealed to him that Bolshevism was alive and well in Cincinnati. According to the Enquirer [9 January 1919]:

“Mr. Richey declared speakers at recent meetings in Cincinnati had advocated immediate revolution and deliberate assassination of public officials who could not be influenced as part of the Bolshevist doctrine. There has been an increase, Mr. Richey said, in the Bolshevist movement in Cincinnati from 500 members 60 days ago, to a membership of a few more than 3,000 today.”

Not quite a week later, the Cincinnati Post [14 January 1919] announced that Richey now estimated a Cincinnati cabal of Bolshevists, International Workers of the World, and various other radical fellow travelers had more than 7,000 members. Richey pledged to continue his investigative work in Cincinnati despite the dissolution of the American Protective League through a new “secret patriotic organization.” According to Richey:

“Members of these groups of radicals, or revolutionists, are guided by a national head, who directs from New York and Philadelphia. Cincinnatians in the organizations principally are foreign born. There are Germans, Italians, Russians, and Hungarians, with some malcontent Americans.”

In a statement that foreshadowed the Red-baiting tactics of Senator Joseph McCarthy thirty years later, Richey predicted that eight to ten Cincinnati officials would soon resign once the Justice Department digested the reports submitted by the American Protective League. By February 1919, Richey’s estimate of Cincinnati radicals had reached 10,000, holding regular meetings to urge the “seizure of banks, manufacturing plants, and private property.”

Richey repeatedly asserted that the Cincinnati Board of Education fanned the flames of Bolshevism here by allowing teachers to spread radical propaganda. After all his stomping and fuming, Richey had trouble producing a single Bolshevik. Nevertheless, he told the Cincinnati Post [3 February 1919], he knew exactly where to find one:

“The home of a Cincinnati school girl, the alleged meeting place of supporters of Bolshevism, is being watched by the secret patriotic organization of which John L. Richey is head, he said Monday. Richey told of existence of a Bolshevik school where students are taught principles of Bolshevism and urged to spread them in educational institutions. A Woodward High School pupil is leader in the movement, according to Richey.”

The moment Richey made that accusation, the city turned against him and his “secret patriotic organization.” The pupil in question was Rose Simkin, aged 19, who had immigrated from Russia six years earlier. Since that time, she had been employed at the Cross Overall Company while studying in the morning before work and in the evening after work at Woodward High School, hoping to earn citizenship. She told the Post [7 February 1919]:

“I hardly know what Bolshevism means. I am an American. I didn’t even know it was I who was being talked about until told so by the school authorities. Ever since I have been in America and lived in this free country I have thought of nothing except what a wonderful land this is.”

Miss Simkin pointed to her bookshelves, filled with volumes by Poe, Shakespeare and other classic authors and defied Richey to find any hint of subversive literature.

Helen T. Wooley of the Cincinnati School Board was outraged by Richey’s accusations against Rose Simkin.

“There has been excessive zeal in trying to uncover un-American plots and in this case they have hit an innocent girl.”

The American Israelite pointed out that Rose Simkin’s brothers were serving in Palestine as part of the British army there and that Richey may not have known the difference between Zionism and Bolshevism – a not-so-subtle accusation of anti-Semitism. Mainline organizations such as the City Club and the Women’s City Club passed resolutions condemning Richey’s accusations.

As the Simkin debacle faded, so did Richey’s “secret patriotic organization.” When Richey died in 1962, his obituary made no mention of the American Protective League or his secret organization.

In 1920, Rose Simkin married Edward Trieman, her father’s partner in a Race Street haberdashery. She lived to be 70 and gave birth to a son who became a doctor. Her tombstone identifies her as “A Devoted Daughter In Israel.”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“That's it, all the topics have been covered. It's four in the afternoon, night has fallen, you can hear the hum of the refrigerator. He looks at his rings, strokes his musketeer's goatee: it's no longer Dumas's Twenty Years After but The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later. I've asked all my questions and it doesn't occur to him to ask me any: How do I live, am I married, do I have children? Do I prefer a warm climate or a cold one? Stendhal or Flaubert? Plain or fruit yogurt? What type of books do I write, since I'm a writer? He says it's part of his mission in life to show an interest in other people, and no doubt he'd be interested in me if he met me in prison, guilty of a beautiful, bloody crime, but that's not how it is. The fact is that I'm his biographer: I ask him questions, he answers, and when he's finished answering he says nothing, looks at his rings, waits for the next question. I think to myself that there's no way I can spend several hours on an interview like this, I'll get along fine with what I've got. I get up and thank him for the coffee and his time. It's right on the doorstep that he finally does ask me a question: "It’s strange, you know. Why do you want to write a book about me?"

I'm taken aback but I answer, sincerely. Because he's living—or he lived, I don't remember what tense I used—a fascinating life. A romantic, dangerous life, a life that dared to engage directly with history.

And then he says something that cuts me to the quick. With his dry little laugh, without looking at me: "Yeah, a shitty life."” - Emmanuel Carrère, ‘Limonov: The Outrageous Adventures of the Radical Soviet Poet Who Became a Bum in New York, a Sensation in France, and a Political Antihero in Russia’ (2011) [p. 337]

#limonov#eduard limonov#eddie baby#Carrère#emmanuel carrère#life#books#bookshelf#library#national Bolshevism#russia#punk#new york#russian literature#russian

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy pride month everyone!

#mod spice#mod sugar#sugar-spice everything nice!#art#centricide fanart#centricide#jreg#jreg fanart#jreg pinkcap#centricide pinkcap#centricide pink capitalism#centricide pink capitalist#jreg pink capitalism#jreg pink capitalist#jreg nazbol#jreg national bolshevism#centricide nazbol#centricide national bolshevism#jreg national bolshevist#centricide national bolshevist

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

An experimental mass spectacle that was engaged both in negotiating the fascist revolution's relation to its Soviet predecessor and in forging an alternative to Bolshevism's mechanical mass subject--the fascist ideal of 'metallized man." Entitled 18 BL (after the model name of its truck-protagonist), the spectacle was the featured event of the 1934 Littoriali Della Cultura e dell'Arte, fascism's youth Olympics of art and culture. The collaborative creation of seven young writers and a film director, 18 BL brought together two thousand actors, fifty trucks, eight bulldozers, four field-and machine-gun batteries, ten field radio stations, and six photo electric brigades in a stylized Soviet-style representation of the fascist revolution's past, present and future.

[...]

18 BL elaborated a total concept of spectacle founded on fascism's wholesale theatricalization of Italian life. Moreover, it aspired to fashion a distinctive mass hero for the new mass theater: a being cast in the image of the nation's leader, at once individualized and mass produced; a subject identified with the transnational values of industrialism, as well as with new image and voice technologies, but in whom the principle of the nation could be modernized and preserved. It created, in short, a mass protagonist who could represent the fascist revolution's continuities with its Bolshevik double but who, in so doing, could also embody the distinctive fascist ethos of constant exertion and fatigue endured by means of individual and collective discipline.

Fascist Mass Spectacle, pp 91-82, JT Schnapp

truly there is nothing new under the sun. the truck is the planet-destroying steed of twenty-first century fascists, used for blockades and convoys as an expression of their stupid might. and nearly one hundred years earlier, almost certainly without their knowledge, Italian fascists used live theatre to depict the ideal fascist subject as a truck

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You must understand. The leading Bolsheviks who took over Russia were not Russians. They hated Russians. They hated Christians. Driven by ethnic hatred they tortured and slaughtered millions of Russians without a shred of human remorse. The October Revolution was not what you call in America the "Russian Revolution." It was an invasion and conquest over the Russian people. More of my countrymen suffered horrific crimes at their bloodstained hands than any people or nation ever suffered in the entirety of human history. It cannot be [over]stated. Bolshevism was the greatest human slaughter of all time. The fact that most of the world is ignorant of this reality is proof that the global media itself is in the hands of the perpetrators."

-Alexander Solzhenitsyn

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ideology

The militant diagram

Either you respect people’s capacities to think for themselves, to govern themselves, to creatively devise their own best ways to make decisions, to be accountable, to relate, problem-solve, break-down isolation and commune in a thousand different ways … OR: you dis-respect them. You dis-respect ALL of us.

—Ashanti Alston[136]

A major force that has contributed to rigid radicalism is rigid ideology, and its tendency to generate certainties and fixed answers that close off the potential for experimentation. Alongside the Marxist critique of capitalist ideology was an aspiration to replace it with a revolutionary anti-capitalist ideology. It was thought that revolution required a unified consciousness among proletarians: they needed to be taught that it was in their interests to overthrow capitalism. The revolutionary vanguard was tasked with developing and disseminating this ideology, and with everything in life subordinated to the goal of revolution, everyone and everything could be treated instrumentally, as a means to the seizure of state power and the end of capitalism.

The philosopher Nick Thoburn links this revolutionary anti-capitalist ideology to what he calls a “militant diagram”: a persistent affective and ideological tendency that first emerged through Bolshevism and Leninism.[137] It was later expressed in movements throughout the twentieth century, from Third World national liberation struggles, to socialist formations in North America and Europe, to Black Power in the 1960s and ‘70s. According to Colectivo Situaciones, a militant research group in Argentina, this figure of militancy is always “setting out the party line,”

keeping for himself a knowledge of what ought to happen in the situation, which he always approaches from outside, in an instrumental and transitive way (situations have value as moments of a general strategy that encompasses them), because his fidelity is, above all, ideological and preexists all situations.[138]

The notion of a correct party line took different forms among different movements, but the basic (hierarchical, rigid) structure was the same: a certain privileged group would help usher in the revolution through a correct interpretation of theory and the unfolding of history. Despite joyful transformations and insurrectionary openings, tendencies towards vanguardism and rigid ideology often led groups towards isolation and stagnation.

Among many other groups, these tendencies can be seen in the US-based Weather Underground, a militant white anti-imperialist group active during the 1970s. They are best-known for their series of bombings targeting public infrastructure and monuments, conducted in an attempt to wake up white Americans to realities of US imperialism such as the government’s slaughter of Vietnamese people and its assassination of Black Panthers.

They also adopted Maoist self-criticism in order to ferret out any trace of the dominant ideology within their group. Criticism sessions, which could last for hours or even days, involved members discussing weaknesses, tactical mistakes, emotional investments, preparedness for violence, and even sexual proclivities in an effort to shed all attachments to the dominant order and induce a revolutionary way of being.[139] Even the most ruthless criticism could be justified as part of this process, and the Weather Underground developed a whole regimen of practices designed to purify themselves of any trace of dominant ideology, coupled with constant injunctions towards (what they saw as) the most militant forms of action possible.

While their tactics were controversial, they were also widely supported at the time, and the Weather Underground was only one of many groups that were bombing and sabotaging corporate and government infrastructure. What we are interested in getting at is not particular tactics, nor something specific to underground groups, but the way that certain tendencies of thought, action, and feeling can congeal into stifling patterns. As former Weather Underground member Bernardine Dohrn writes,

Weather succumbed to dogma, arrogance, and certainty. We were not alone. There was recovery, and amends that are still underway. But the perceived necessity to have answers to everything and to struggle endlessly resulted in ungenerous and damaging leadership, harm to great comrades, and wretched behaviour.[140]

As Bill Ayers, another former member, explains, the attempt to escape completely from a culture of white supremacy and capitalist conformity enforced an intense, alternative orthodoxy:

It was fanatical obedience, we militant nonconformists suddenly tripping over one another to be exactly alike, following the sticky roles of congealed idealism. I cannot reproduce the stifling atmosphere that overpowered us. Events came together with the gentleness of an impending train wreck, and there was the sad sensation of waiting for impact.[141]

Though the goal was to create revolutionary forms of organization capable of overthrowing the US government, their ideological rigidity and norms of relentless self-sacrifice paradoxically isolated them further and further from the “masses” that they sought to mobilize.

When we interviewed him, Gustavo Esteva discussed his own experience of Marxist-Leninist militancy in Latin America during this time:

In the ‘60s, when I became associated with a group in the process of organizing a guerrilla in Mexico, whose members were assuming that they were already the vanguard of the proletariat because they had the revolutionary program, I was fully immersed in what we now call sad militancy. Our “program” was evidently an intellectual construction in the Leninist tradition. We had already our criticism of Stalinism, etc. but we still were in the tradition of trying to seize the power of the state for a revolution from the top down, through social engineering. We were thus preparing ourselves (military training, etc) and organizing. Of course, there were moments or conditions of joy, laughter, intensified emotion, exhilaration … The environment of conspiracy and clandestinity and the shared ideology shaped real camaraderie and episodes full of joy, but it was clear that the experience itself was pure sad militancy, full of creating boundaries, making distinctions, comparing, making plans, and so on … How the whole experience ended makes the point better than any of those stories: one of our leaders killed the other leader because of a woman. The episode evidenced for us the kind of violence we were accumulating in ourselves and wanted to impose on the whole society. In the military training, for an army or a guerrilla, to learn how to use a weapon is pretty easy; what is difficult is to learn to kill someone in cold blood, someone like you, that did nothing personal against you … Nothing sadder than that.[142]

The experience of the Weather Underground and Esteva both make it clear that these ideological tendencies are not just about ideas; they also contain their own pleasures and highs, induced in part by the sense of being clandestine and more aware than “the masses.” Ideology is not simply rigid and cold: it can include a warm sense of belonging and camaraderie among its adherents.

This tendency has percolated into contemporary movements and groups, including those that are not directly influenced by Marxism-Leninism or Maoism. Nick Thoburn suggests,

It is a central paradox of militancy that as an organization constitutes itself as a unified body it tends to become closed to the outside, to the non-militant, those who would be the basis of any mass movement. Indeed, to the degree that the militant body conceives of itself as having discovered the correct revolutionary principle and establishes its centre of activity on adherence to this principle, it has a tendency to develop hostility to those who fall short of its standard.[143]

As militant rigidity increases, a gap widens between the group and its outside. But a single, unified Marxism-Leninism has existed only as a dream. In reality, there has been a proliferation of sectarian commitments to various ideologies, including strains of Marxism, anarchism, socialism, and so on. Ideological thinking is not necessarily something escaped through more and better thinking. For Esteva, one of the things that fundamentally destabilized the strictures of his Leninism was his joyful encounter with others, and their confidence in their own capacities to respond to problems with conviviality:

The joy of living, the passion for fiestas, the capacity to express emotions, the social climate that I found at the grassroots, in villages and barrios, in the midst of extreme misery, began to change my attitudes. My participation in different kinds of peasant and urban marginal movements gave me a radically different approach. The break point was perhaps the explosion of autonomy and self-organization after the earthquake in Mexico City in 1985. It became for me a life-changing experience. The victims of the earthquake were suffering all kinds of hardships. They had lost friends and relatives, their homes, their possessions, almost everything. Their convivial reconstruction of their lives and culture would not have been possible without the amazing passion for living they showed at every moment. Such passion had very powerful political expressions and was the seed for amazing social movements. In the following years the balance of forces changed in Mexico City, already a monstrous settlement of fifteen million people. There was a radical contrast between the guerrilla and these movements. The very notion of militancy changed in me: it was no longer associated with an organization, a party, an ideology, and even less a war … It was an act of love.[144]

To experience joy in this way is not simply to feel good, but to be transformed. Esteva’s experience with the grassroots led him to center conviviality and joy in his work and his life while continuing to be involved with and support militant movements, including the Zapatistas and the insurrectionary uprisings in Oaxaca.

For us, this shows that militancy is always about more than tactics or combativeness; it is tied to questions of affect: how movements enable people to grow their own capacities and become new people (or don’t). Marina Sitrin consistently foregrounds affect in her own work with horizontalist movements in Argentina, and when we interviewed her for this book, she talked about her experience with the different affective spaces created by groups she has been involved with:

On a basic level, the space a group or movement creates from the beginning is key—the tone and openness, or not, makes a big difference if one wants to focus on new relationships with one another. Along these same lines, ideological rigidity and hierarchies in ideas, formal and informal, create a closed and eventually nasty space for those not ascribing to the ideology or a part of the clique. People do not stay in movements that organize in this way, or if they do it is with a sort of obedience that is not transformative and instead creates versions of the same power and hierarchy …

My early organizing experiences were fortunately with anti-racist and later Central American Solidarity movements, with people who had been a part of the civil rights and later anti-nuclear movements, so who had a focus at least in part on social relationships and democracy. Later however, when I decided I needed to be a part of a revolutionary group that was organizing against capitalism as a whole, well, I found myself in a few different centrist socialist groups which were really soul-deadening. It was all about ideology and guilt. One could never do enough, and could never know enough or quote enough of whomever was the revolutionary of the day (James Cannon, Tony Cliff, etc). It was also politically all about the end and not the day to day, that even included women, which one would think, after the radical feminist movement, [that] these groups would get that relationships have to change now; but no, it was all about the future free society we all had to work for—accepting relationships as they are, pretty much.

I later came around some anarchist groups, thinking that they would be more open and focused on the day to day, as that is what I had read from the theory, but found the rigidity around identity too harsh and since I was not squatting or dressing a certain way I was kept at arm’s length—which was fine since I felt too rejected to try very hard.[145]

Sitrin’s account makes it clear that rigid radicalism does not stem from one ideology or group in particular. Marxism-Leninism has lost its grip on many movements, and accounts of such groups can sound strange and distant today. In North America at least, the dream of a revolutionary seizure of state power has lost a lot of its force, but in many cases Marxist ideology has been superseded by other ideological closures and sectarian tendencies. Currents of anarchism can be just as hostile and ideologically rigid.

#joy#anarchism#joyful militancy#resistance#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#revolution#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism

10 notes

·

View notes