#mrs bennet critical

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I always find it interesting that no one in P&P has any doubt that Mr Gardiner could and would have shelled out ten thousand pounds to bribe Wickham.

Mr Bennet is determined (at least at the time) to eventually repay him, when he believes Mr Gardiner paid it, but he does believe that. Mrs Bennet simply shrugs off the vast sum of money that everyone believes was expended to preserve Lydia's reputation. Her justification is that she and her daughters would have inherited all her brother's money if he hadn't gone and got married and had children of his own (how dare!). His assurance that she's going to be fine is not an empty one.

Elizabeth doesn't seem to doubt it, either. And earlier, at Pemberley, she assumed that Darcy had mistaken the Gardiners for members of fashionable upper-class society—a believable mistake to make, apparently, and he is surprised that they're Mrs Bennet's relatives. (I mean. Fair.) Their summer trip is likely not a cheap one. They're doing quite well.

In any case, I do think the Gardiners' prosperity and its bearing on the Bennets' situation is kind of overlooked by the fandom.

#honestly i think mrs bennet's response to mr gardiner apparently paying ten thousand pounds for lydia to marry /wickham/#is pretty repugnant actually#the whole thing about how she would have been his heir#and he hasn't done anything except give presents to her children so he /should/ pay for lydia is. wtf.#(this is also manifestly false since elizabeth and jane frequently stay in the gardiners' house...)#in any case the bennet women were never going to be left out in the cold by the gardiners#anghraine babbles#austen blogging#austen fanwank#edward gardiner#m gardiner#mrs bennet critical

364 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you want to turn Mr Darcy into an evil villain in order to make a point about how Elizabeth was really the superior of the two then maybe, just maybe, you don't actually like or respect Elizabeth Bennet all that much.

I mean, why else would you actually want her to end up with an 'ugly, conceited, rude, humourless snob'? Do you underestimate her intelligence to the point of thinking she would willingly end up with a man like that? Do you not believe her to be capable of choosing a suitable husband? Did you even read the book... or are you actually just frustrated by the reaction to certain adaptations?

Because with this interpretation in mind, Elizabeth might as well have ended up with Mr Collins...

#you certainly don't respect jane austen because she would be horrified if she saw her heroes being spoken of in such a way#pride and prejudice#elizabeth bennet#mr darcy#jane austen#i truly hate it here#elizabeth bennet get behind me!!!!!!#they're making a point about a man's flaws and in the process underestimating your intelligence#nuance and critical thinking are a lost art form. . ... ..#i can't believe THIS person is making an adaptation of p&p it's horrifying#hands off the classics lady!!!#my analysis

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The way we see mothers in fiction reflects our relationship with our own mothers.

Unless we're going mommy dearest and similar works that show narcissistic mothers and problematic/toxic relationships and portrayals, those are undeniably horrible and bad.

However, when we talk about general mothers portraiture we're going to immediately judge also through what we live and experienced.

I have a wonderful relationship with my mom, though she had me hours after she turned 18, and of course, have committed errors, she still succeeded in parenting and raised me with the best of her abilities. Therefore, I tend to see mother-sons/daughters relationships in a good light, as as depth and development goes by, I can change and adapt my initial opinion.

Therapist and Psychology Professors oftenly remarks that mothers, in a way or another, have some parcel of guilt over how her kids will develop and turn out, some more, some less. Relapse mother? Troubled kids. Distant mother? Insensitive kids. Overbearing/Overprotective? Kids learn to lie, omit, rebel. So on and so forth.

Mothers do have a hand on how you deal with your life. But a loving mother, a zealous mother, a young mother, an older mother, a religious mother, a free spirit mother... All of them doesn't have to justify themselves beyond maybe acknowledging where they went wrong, because, after all, aren't all of them also bound by expectations, morals, time and beliefs? And weren't all of them doing what they thought was right? Weren't all of them dealing with motherhood differently and in their particular ways? With or without support, they did what they could.

But take a look at these mothers:

They made mistakes, do they have to justify themselves and ask for forgiveness? Because they did what they have to? To survive, to attend demands, to protect, to ensure their safety and success...

There are mistakes, and there is also another even greater problem: you have to grow up and learn how to deal with this pain yourself, talk, digest, transform it, but no one but yourself will have to learn how to deal with it, even when it was done with such toxic and cruel behaviors, you will have to deal with it. To love or to hate.

Now, let's focus on the love part.

Mary, Elizabeth, Isabel, Januaria, the Bennets girls, Khadija, Alicent, Hürrem and Rhaenyra's children, all of them wouldn't even ask for their justification, ask why they did what they did, because they all know their mother loves them no matter what, they did what they had to do. Distant or not, overbearing, hysterical, insensitive, and doomed by the narrative. They know, and eventually recognize that those actions were done by love.

So yeah, go on, ask your loving mother to justify herself, I dare you all. Ask your grandma and aunt too. Ask that one mother who pissed you off online too.

Also, don't forget that maybe, that parenting style was all they came to know about. And unless one breaks a very long and, shockingly, difficult to recognize cycle, they will unknowingly perpetuate it.

Anyway. That's how I see it. Because oh boy, I wouldn't even ask my mom to explain herself to me, no matter my grievances. But that's a me thing. How do you see it?

#that's my opinion#you may have other insights and approaches#I won't fight and won't even answer rude answers and @#so beware#mothers#parenting#critical of the world#alicent hightower#rhaenyra targaryen#hurrem sultan#jade al adib#o clone#maria leopoldina#teresa cristina#catherine of aragon#anne boleyn#mrs bennet#the tudors#hotd#pride and prejudice#nos tempos do imperador#novo mundo#muhtesem yuzyil#magnificent century#polemic topic but whatever

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm about to say something controversial I think, but I'm not really into the Lizzie Bennet Diaries. For me, the very premise of the show is a non starter, because I cannot BELIEVE that ANY version of Elizabeth Bennet would record people without their knowledge or consent and post those clips online to a large viewing audience. I'm not being a protagonist moral purist; if Lydia was our main character I'd totally roll with it. But it is, objectively, reprehensible behavior that would FIRMLY put Lizzie in a category with "the lack of propriety" shown by her parents and younger sisters. This is a woman who, in the original story, didn't even tell her sisters that Wickham was bad news to protect Georgiana, and you think she'd post Jane's private moments online??? No. Elizabeth has character flaws but invasion of privacy and airing other people's business are never part of them.

#lbd critical#critical#penny posts#i didnt hate it when i watched it but its much more an adaptation of the plot than of the characters if that makes sense#this came up because ive gotten like 100 people telling me to watch lbd after my pride and prejudice but marriage is career post#this is a different cake.#i have been holding this in for a long time#i want to be polite and not rain on parades#but please stop telling me to watch lbd#i have#its also not what i was looking for as a side note because the genesis of that post is actually about mrs bennets characterization#and all the other additions were just fun afterthoughts to stretch that premise#but thats another note i should make another post on

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emma and Mister Darcy Similarly take Responsibility and Prove they are Ready for Marriage - Essay 2024

Orianna Jiwani December 2, 2024 Professor Trisanne Connolly ENGL 325 Emma and Mister Darcy Similarly take Responsibility and Prove they are Ready for Marriage Austen’s two most popular romance novels Emma and Pride and Prejudice are exceptional works. She wrote of Emma that she wanted “to take a heroine whom no-one but myself will much like”, and with this idea she made an attractive romance…

#analysis#class#clever#creative writing#critical#elizabeth bennet#emma#emma and mr darcy are similar#essay#jane austen#me knightley#miss bates#mr bingley#mr darcy#novel#pride and prejudice#romance#similarities#university essay#writer

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sorry, still not over Darcy critical-failing that proposal! Not that sorry, though. I have no idea why Pride and Prejudice hits so hard when most of Austen's other novels are like "They're fine! I like them! Anyway..." for me.

But, here's the thing. Darcy is being an asshole. Darcy isn't an asshole, generally, but he's really being one about his whole Regency Era situationship with Lizzie. Like, he rolls in on day one with this giant fucking chip on his shoulder, acts like he's too good for everyone, and why? Well, he's rich, and he's got lofty connections.

Except who's he rolling with right then? His spineless dustmop of a bestie and his bestie's godawful sisters. Bingley's the sort of guy who can be peer-pressured out of being in love!

Like, you know that thing where you have a friend, and they introduce you to another friend, and that friend is such a wet sock that you find yourself reevaluating your friend because they're hanging around with this guy? Like, okay, Darcy, do you have friends, or do you have toadies? Is this your bestie, or did you find a gentleman's companion that you didn't have to pay?

Later on we meet his aunt, who's the goddamned worst.

Like, we all hate Mr. Collins, right? This woman has Mr. Collins over twice a week for a quiet evening of performative dickriding. That's the kind of taste Darcy's family has. Voluntarily spending hours with Mr. Collins on a regular basis.

There's no talking about Mrs. Bennet's lack of decorum or matrimonial grasping or entitlement without talking about Lady Catherine flying in on her broom to scream at her nephew's fiancee, right? Especially considering that her basis for doing so is a cradle engagement that she seems to have never spoken to her nephew about as an adult and a fucking rumor that she assumes pertains to Lizzie.

She doesn't even talk to her fucking nephew before spending half a day in a carriage to make a blazing spectacle of herself in front of the entire Bennet household! He finds out she did that afterwards when she tries to make him break off the nonexistent engagement that she's announced to half the fucking kingdom by that point.

I mean, unexpected point to Mrs. B, who notably did not even walk down the road to Netherfield to act disappointed at anyone.

Also hard to get on too high a horse after Georgiana's near-elopement with the country's biggest asshole! Like, oh, the Bennet sisters are embarrassing? The Bennets lack propriety?

Buddy, you hired a sex trafficker to look after your sister and then your sister almost fucked the one-man-crime-wave son of your late property-manager. And you didn't even manage to hush it all up properly! Sure, he's keeping your sister's name out of his mouth, but he's running you down like a dog in every other respect to the whole county!

Like, "Oh, look at me, I'm Fitzwilliam Darcy! I'm not going to lower myself to correcting any of The Plebes who now think I deliberately misadministered a will to fuck over The Help out of cheapness and spite, especially when all it would take is one conversation with That Fucker's commanding officer, but god forbid I ever have to go out in public with a Bennet! I might die of shame and secondhand cringe!"

So he's got all of that going on, and then he busts in on Lizzie with a proposal that's got huge "I don't consent to being attracted to you" energy and runs her entire family into the ground. This is after Lizzie's spent approximately three centuries being negged by his mannerless nightmare of an aunt, so that's at least one extra level of "Really, bruh?" in there.

And then he fucking claps back at her rejection! Instead of going "Oh. Huh. Whoops. Guess I'll just have to go marry one of the other ten thousand women lined up waiting to marry me!" he's like "What the fuuuuck did I ever do to you, you fucking menace?". At which point she checks him so hard he spends the next three months bluescreening and looking up how to be polite to people you haven't already known for five years.

So like I said, he is being an asshole here. He knows how to act right, he just hasn't bothered to do so once since posting up in Netherfield because idk, he's on vacation or some shit.

Critically! However upsetting Lizzie finds The Proposal Incident (half-hour crying jag, spends the rest of the day hiding in her room), she is at no point worried about Darcy's subsequent behavior.

This is while she still thinks he genuinely did Wickham dirty and before she's had a chance to get character references from the 500 people working at Pemberley. This is the guy about whom her dad later says "Kidding-not kidding I can hardly say no to this rich fuck, can I?" when asked for his blessing. This is after Mr. Collins literally said "I've heard no means yes these days" to her fucking face and then her mother tried to make her marry him anyway.

She preached a full on sermon about the man's shortcomings to his face immediately after saying she wouldn't bounce on his dick if it was the last one on earth and after the adrenaline crash wasn't like, "Fuck. Fuck. Fuuuuuuuck my entire life, he's going to burn down the vicarage and frame my father for tax fraud."

Everything that she's seen with her own eyes about this snobby bastard tells her he's not going to go crying to his aunt and get her cousin's patronage revoked. He's not going to go out of his way to fuck her or her family over. He's pissed, and he was definitely playing the ass with that proposal, but he's not going to lash out over it.

So this is Lizzie seeing Darcy at Peak Asshole, with extra assholery that he didn't even do but he couldn't be bothered to tell anyone he didn't do, and Lizzie's still like "omg you're such a fucking prick, how do you even get out of bed in the morning" instead of "Well, RIP to my prospects, there's no way that man doesn't have the lot of us consigned to a convent by parliamentary decree now."

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm thinking about responses to Dracula - both adaptations and critical responses - and how the main thing that they seem to get wrong (at least from my perspective) is their approach to the romantic relationships in the novel. You know the kind of thing: Arthur is boring, Jonathan is boring, Lucy lusts after all three suitors, Mina lusts after Dracula, the suitors must all be suppressing their jealous hatred of one another.

It feels to me like it all comes from the same place, and that place is the idea that romantic relationships, particularly at the start of a story, can't or shouldn't be straightforward.

Instead, Dracula begins, near enough, with two women who have both met and are set to marry men who they love and who love them in return, and where it seems like there is no intrinsic reason why they shouldn't live happily ever after.

And normally we don't expect that. Certainly these are not the narrative rules of a romance (which Dracula isn't, but bear with me). It's a little bit like if Elizabeth Bennet was actually really into Mr Collins and accepted him right away, if Jane Eyre was blissfully happy with St John Rivers, or if Margaret Hale fell for Henry Lennox. Jonathan and Arthur are the safe choices for Mina and Lucy, and we don't normally expect heroines to want the safe choices.

Mina and Lucy do. Arthur is strategically the best husband for Lucy - good family, pots of cash, no weird job, her mum likes him - but he is also the man that Lucy loves. Mina and Jonathan are utterly besotted with one another, and though Jonathan isn't as wealthy as, say, Jack Seward, his career is also on the up. He's a good choice.

I think this works brilliantly in Dracula, because the later threat is so much the greater for the fact that everyone starts out the novel so strong. The fact that they are so happy to begin with means they have more to lose.

So many responses to Dracula want this to be a novel in which love is complicated, but instead it's a novel in which love is both pretty straightforward and always good. And I think it's more interesting for it.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes Darcy gets accused of not actually being in love with Elizabeth at the time of his first proposal, that he just proposed out of lust, and like yeah lust was definitely a part of it, but I believe him that he truly loved Elizabeth.

Marriage was a big deal. He'd never really be able to divorce her. This was gonna be it for life—and while Elizabeth for life might be wonderful, he's also getting the Bennets for life.

I don't know how much he knew about the Bennets' financial situation beyond the entail, but he had to have known there was a strong chance Mrs. Bennet would end up living with him after Mr. Bennet died. He could afford to set her up in her own house, but they'd still have to spend a lot of time together. And it wasn't just Mrs. Bennet—he'd be saddling himself with the lifelong care of potentially multiple of Elizabeth’s relatives, which is bad enough when you actually like the people, but these are people who he can't stand, and rightfully so! I'd despise living with any of them except Elizabeth and Jane, and maybe Kitty. He's not being a snob when he criticizes them—they legitimately suck. (Well, he is being a snob and dumbass by saying it out loud, but Elizabeth herself knows the criticism is justified.)

On top of all that, he knows marrying Elizabeth is gonna piss off his own family, and potentially jeopardize his friendship with his bestie Charles.

And you're telling me that Darcy was willing to take on all of that shit just for sex?? Sex is easy to get. Hell, even sex with a pretty, kind, smart wife would be easy for Darcy to get. Elizabeth is not his only good option.

I know people's genitals make them do all sorts of wildly stupid things, but I don't think even Darcy's penis is powerful enough (and I've read fanfic, I know how powerful Darcy's penis is) to make him propose to Elizabeth Bennet if he didn't truly love her.

#yeah i'm sure he grows to love her even more deeply by the second proposal#but i'm certain there's real love there at the first proposal#he's dumb but not unintelligent and reckless#pride and prejudice#jane austen#mr darcy#elizabeth bennet#the bennets#literary analysis

881 notes

·

View notes

Text

People love dichotomies.

One of the dichotomies people love inserting into Jane Austen is “marrying for love” vs “marrying for money.”

We have a chicken or egg question here about if people read this into the text so much because so many adaptations add dialogue that lays it out, or if so many adaptations add dialogue that lays out such a conflict because people love to read it into the text.

But if you read the books themselves, it just isn’t there. (This is why the occasionally bandied criticism that Austen “gets out” of having to make a choice by having her heroines “conveniently” fall in love with men who have enough money to marry on is irrelevant - that’s not what’s going on).

Instead, across her works, Austen presents marrying for love and marrying for money not as a dichotomy, but as opposite ends of a spectrum in which the rare extreme ends are each foolish and almost everyone negotiates their way through the space in the middle.

You see, to make a “good” marriage in the Austen-verse, you need a trifecta. And you do need all three - if you try to justify skipping one by maxing out one of the others, things will not end well for you.

The three things you need for a good marriage are these:

Personal compatibility and mutual respect

Financial stability within your social class

Positive feelings towards each other

You do not need love! Love is just a max-out on positive feelings, and while all her heroines find romantic love in marriage in the end (these are love stories), it’s not portrayed as necessary - Marianne Dashwood marries out of respect and gratitude and falls in love afterwards, and we don’t know about most of the minor characters, but there’s no reason to suppose that all minor character happy marriages we see are love matches. The Gardiners, for instance, could have married on simple fondness and the mutual desire to form a household, and they seem perfectly happy.

You do not need wealth! Wealth is just a max-out of financial stability. Plenty of heroines (Elinor Dashwood, Catherine Morland, even Fanny Price and Anne Elliot) marry men with respectable incomes but no land-holdings or vast riches.

I can’t think of an example for the third piece - if there is a couple in Jane Austen who are maxed out on mutual respect and compatibility, it’s the Crofts, and they also like each other and have enough to live on.

But if you’re missing one leg of the three-legged stool, you are in trouble!

Fanny Price’s parents married for love, but had no money - and they both seem pretty miserable when we see them again.

Maria Bertram marries for wealth alone, with no affection or respect for her husband - and it makes her life a train wreck.

The Bennet parents seem to have been a love match (why else would he marry a woman of no family who used to be a great beauty) and he has enough to live on whether she brings in a dowry or not. But they are not compatible and don’t respect each other, so their marriage is still kind of a disaster.

The closest example we have of someone seeming to get along ok without all three is Charlotte Lucas, who marries for financial independence, and while she’s more compatible with Mr Collins than she seems at first blush (they’re both unembarrassed to suck up to Lady Catherine), she has no positive feelings towards her husband, but still seems to be alright with her choice. And yet even there, the narrator warns that she may not always have as few regrets as she does now.

Any time you try to look at the various matrimonial decisions made by Jane Austen characters through a lens of love vs finances instead of considering whether and to what extent a marriage might check all three boxes, you’re doing it wrong.

#jane austen#pride and prejudice#sense and sensibility#mansfield park#persuasion#northanger abbey#emma

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pride and Prejudice adaptations with a modern setting – e.g. The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, Bride and Prejudice, Pride and Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy, Fire Island – seem to almost always save Lydia from Wickham in the end. Either Darcy stops the elopement, or the elopement is replaced with an online sex tape which is taken down. Wickham is either arrested or at least left behind permanently, and Lydia learns a lesson and gets a happy ending. Neither she nor the other characters have to live with her mistake for the rest of their lives the way they do in the original.

I've just been rereading several people's posts on this subject, and about Lydia's portrayal in general, which show some very different opinions about it all.

Of course, part of the issue is that in a modern setting, it's much easier to save Lydia. In most of the modern Western world, a teenage girl running off with a 30-year-old man would result in the man being arrested, not in their needing to get married to save both the girl's reputation and her whole family's. And even if they did get married, divorce is an option.

But I suspect the bigger issue is that Austen's original ending is considered cruel, unfair, and a product of outdated morals.

People view Austen as punishing Lydia for being a "bad girl" by leaving her trapped in a loveless marriage to a worthless man and always living on the edge of poverty, when by modern standards, she's guilty only of teenage foolishness. They accuse Austen of "making an example" of Lydia to teach young female readers how to behave, in contrast to the virtuous, well-behaved Elizabeth and Jane with their happy endings, and they call it anti-feminist.

Not only is Lydia's marriage bleak for her, it slightly mars Elizabeth and Darcy's happy ending too, as well as Jane and Bingley's. It means Wickham will always be a part of their lives, and for Lydia's sake, they're forced to treat him as a family member. Darcy is forced to financially assist his worst enemy – though at least he draws the line by not letting Wickham visit Pemberley – and even Jane and Bingley's patience is worn thin by the long periods of time Wickham and Lydia stay with them.

By modern standards of romantic comedy, this isn't normal. The heroine, the hero, and all their family and friends are expected to live entirely "happily ever after," while the antagonist – especially if he's a womanizer who preys on teenage girls – is expected to be punished, then never heard from again.

But of course, Austen didn't write simple romantic comedy. Her work was social commentary. Lydia's ending arguably isn't a punishment, but simply the only way her story could end without disgracing her or killing her off, and it arguably it serves less to condemn Lydia herself than to condemn the society that lets men like Wickham get away with preying on naïve young girls and forces their victims to marry them or else be disgraced forever. It also condemns the type of bad parenting that leads to Lydia's mistake. Lydia is the product of her upbringing, after all: between Mrs. Bennet's spoiling and Mr. Bennet's neglect, she's never had any decent parental guidance or protection. And our heroines, Elizabeth and Jane, both pity their sister and regret that marriage to Wickham is the only way to save her honor. No sympathetic character ever says she deserves it.

The fact that Lydia is trapped in a bad marriage, and that Wickham does go unpunished and the other characters will always have to tolerate him and even cater to him for Lydia's sake, arguably drives home Austen's social criticism. The fact that it adds bittersweetness to the otherwise blissfully happy ending is arguably part of the point. If we change it just to create a happier ending, or in the name of "feminism" and "justice for Lydia," doesn't that dilute the message?

Then there's the fact that by the standards of Austen's era, Lydia's ending is remarkably happy. She doesn't die, or end up abandoned and forced into sex work or a life of seclusion. Nor, despite Mr. Collins' recommendation, does her family cut ties with her: the ending reveals that Jane and Elizabeth regularly welcome her into their homes, and Elizabeth "frequently" sends her money. Other authors would have punished her much more severely.

But of course, that was a different time. While in Austen's original context, Lydia's fate might seem fairly happy and lenient, by modern standards it seems more cruel. And since most of the modern retellings that change her fate are screen adaptations, not books, maybe the difference in art form further justifies the change. I'm thinking of that post I recently reblogged, which argued that some of Austen's more "merciless" plot points would seem darker on film than in print, and therefore tend to be softened in adaptations.

So how should a modernized adaptation handle Lydia's ending? Is it better and more progressive when they save her from Wickham? Or for the sake of social commentary and retaining Austen's sharp edges, should the writers follow the book and find a way (not necessarily marriage to Wickham, but some modern equivalent) for her mistake to leave her trapped in a less-than-happy life, and add a slight bittersweet note to the other characters' endings too?

I think a case can be made for both choices and I'd like to know other people's viewpoints.

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meanwhile, in one of my other main fandoms:

My post about reading a surprisingly good article on eighteenth-century economics and (tangentially) Austen showed up on my dash again, I think thanks to @ladytharen. Now that my mind is rather clearer, I remembered that the author (Robert D. Hume) had left a footnote in the brief Austen section saying that it was contracted from a fuller discussion he'd made in a previous paper. I'd meant to check the previous paper out and simply forgot at the time, but that reminded me, so I read the other article, dated to the previous year (April 2013).

This article is simply called "Money in Jane Austen" (much less of a mouthful!), but is similarly granular about details. In terms of the general argument, the abundance of historical and textual details very much works in his favor. But he does fall a bit into the "AustenTime" problem, unfortunately, in this one.

I know I have another post talking in more detail about this, but I couldn't find it! Anyway, "AustenTime" is a term I heard once and have never been able to track down again for an approach to Austen and the times she lived through as this sort of pocket universe in which everything is happening in the same eternal moment that's roughly associated with the Regency England of the 1810s when her novels were first published (and often even more with "the Regency" as codified by Heyer and the Regency romance writers who followed her). Hume's take is much less Heyer-inflected than the usual, of course, but given his general attention to very precise details, it seemed odd that he didn't distinguish more between economic data from the 1770s, 1790s, and 1810s while lumping all her novels into c. 1810.

That said, he did use okay numbers for the central arguments wrt P&P and built from Austen's own extreme and painful consciousness of just how far not much money could go, to the gulf between her circumstances and even characters like Elizabeth's, and then to politely disagreeing with the kind of characterizations of the Bennets' lifestyle you find in even normally reliable things like The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen. His argument is basically that there's enough textual information to tell us that the Bennets are fairly wealthy by genteel standards, not minor struggling gentry—at about the level of typical baronets in terms of income/land/lifestyle (Mr Bennet's situation is certainly more comparable to a random baronet's than Darcy's). Hume goes into estimates based on explicit details in the novel about the Bennets' household staff etc and what that would signify at the time, all good stuff, so that he can express his true feelings.

And his expression of those was actually really cathartic to read, because Hume's true feelings turn out to be even more seething rage at how much Mr Bennet sucks as a father than I would have guessed from the other article. He's like—

"Mr Bennet sucks SO MUCH y'all, and you might think I'm being ahistorical in my rants about what a failure he is, no I'm not overusing italics he DESERVES italicized hate*, and I've got contemporary source after contemporary source to prove just how incredibly irresponsible and selfish this guy is by the standards of the time and how callous he is about his children's future and even about the ungodly amount of money that Darcy drops to fix Mr Bennet's failures, and maybe it's not clear to most modern readers just how much that would have been BUT I HAVE THE NUMBERS. I swear this character is such an asshole and I'm embarrassed for ever liking him, honestly, and just because Elizabeth doesn't fully condemn him—but hey, remember that passage where she clearly knows more than she's been saying about what kind of man he is—doesn't mean that Austen isn't doing so. Elizabeth doesn't end up paying for Mr Bennet's colossal failures as a father and human in the novel only by authorial fiat, aka Darcy, whose circumstances are almost unimaginably niche even for high-ranking peers—but that's the fantasy, you know? And Charlotte's there to remind us of the reality of just how dire this situation could be in more typical lives, even when we're talking about the women in the richest 1% of the population."

I had a few other nitpicks, but the combination of detailed economic breakdowns and unashamed raw hatred for a character I also despise was truly enjoyable. And it was also—um.

Despite my griping about various Austen critics, I have my own struggles with imposter syndrome, and always feel guilty about how much Important Academic Work In My Field there is that I just haven't gotten around to and how I always feel like I'm missing important information and blahblahblah. But I do feel it a lot more acutely with the seventeenth-century works I've studied, since I came to that a good 15 years after I started getting into Austen criticism. Even so, I was surprised by how soothing it was to read an Austen essay that's imperfect but good and that is punctuated by all these references to other scholars whose names and work I recognized, influential interpretations that I've already read, all that kind of thing. It felt a bit like coming home, honestly, and it was reassuring that everything was so familiar at this point.

---

*He did not actually say that Mr Bennet deserved italicized hate, but italics for emphasis are actually really rare in this kind of writing and there are quite a few of them in the Why Mr Bennet Is The Worst section. More power to you, sir.

#anghraine babbles#long post#austen blogging#austen fanwank#mr bennet critical#boy is it ever. lmao.#ivory tower blogging#austentime critical

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just finished reading Sense and Sensibility for the third or fourth time and am on Chapter Ten of Pride & Prejudice. And it got me thinking, do we know what any of the characteds look like, mainly physical characteristics and such?

Thanks for your question! Extremely well-timed on your part as I started reading What Matters in Jane Austen by John Mullan yesterday and there's an entire chapter dedicated to how Austen deals with her characters' physical appearances.

The short answer is, not really! If you finish reading an Austen novel without a clear picture of the characters in your mind, don't worry! You haven't 'missed' anything. Descriptions of the physical appearances of the characters are few and far between, with the only heroine having a definitive eye colour being Emma (hazel). Any attention given to how they look is sparing, with specific features described and highlighted to serve particular purposes. Especially in Pride and Prejudice (which I will dwell on as I'm most familiar with it), descriptions of the characters' physical appearances often tell us more about the character who spoke it rather than the one being described.

For Elizabeth, we have some examples of how Darcy sees her:

But no sooner had [Darcy] made it clear to himself and his friends that she hardly had a good feature in her face, than he began to find it was rendered uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of her dark eyes. (Ch 6)

Though he had detected with a critical eye more than one failure of perfect symmetry in her form, he was forced to acknowledge her figure to be light and pleasing. (Ch 6)

Even when denying his attraction to himself and everyone around him, Elizabeth is so captivating that he is almost forced to admit that she has some attractive features... which means they really must be something for a man so decided against her to acknowledge them. My personal opinion is she's probably not as instantly stunning as the women Darcy will have encountered at various balls in town, but there's something about her that draws her to him, perhaps aided by her personality.

Still, these descriptions are pretty vague. The most detailed description we have of Elizabeth comes from a character who has ulterior motives (to say the least) when giving it. Miss Bingley is filled with such jealousy that I do not believe this to be an entirely credible description as she is desperately trying to put Darcy off in any way that she can:

'For my own part,” [Caroline] rejoined, 'I must confess that I never could see any beauty in her. Her face is too thin; her complexion has no brilliancy; and her features are not at all handsome. Her nose wants character—there is nothing marked in its lines. Her teeth are tolerable, but not out of the common way; and as for her eyes, which have sometimes been called so fine, I could never see anything extraordinary in them. They have a sharp, shrewish look, which I do not like at all; and in her air altogether there is a self-sufficiency without fashion, which is intolerable.'

Still pretty vague, but I mainly take from this that Elizabeth must have genuinely incredible teeth for even Caroline to concede that they are 'tolerable'!!!

Descriptions of Darcy are even rarer, with his height apparently being his standout feature:

'Mr Darcy soon drew the attention of the room by his fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien... the gentlemen pronounced him to be a fine figure of a man, the ladies declared he was much handsomer than Mr Bingley*' (Ch 3)

'...if Darcy were not such a great tall fellow, in comparison with myself, I should not pay him half so much deference...' (Mr Bingley in Ch 10)

'it looks just like that man that used to be with him before. Mr what’s-his-name. That tall, proud man.' (Kitty in Ch 53)

(*difficult to know if him being handsomer than Bingley is entirely credible as such an assertion is linked to Darcy being twice as rich! These descriptions are given before Darcy offends everyone with his rudeness)

Also, despite what adaptations portray, Mr Collins was not a short, middle-aged man. Rather, he was 'a tall, heavy-looking young man of five-and-twenty' (Ch 13).

It is important to note, however, that this vagueness wasn't down to laziness or uncertainty on Austen's part regarding how her characters looked. In fact, she knew her characters so well and had such a clear idea of how her characters' appearances that she was actively looking for them irl, as a letter from 1813 to Cassandra proves:

'I was very well pleased (pray tell Fanny) with a small portrait of Mrs Bingley, excessively like her. I went in hopes of seeing one of her sister, but there was no Mrs Darcy. Perhaps I may find her in the great exhibition, which we shall go to if we have time. Mrs Bingley's is exactly like herself,—size, shaped face, features and sweetness; there never was a greater likeness. She is dressed in a white gown, with green ornaments, which convinces me of what I had always supposed, that green was a favorite color with her. I dare say Mrs D. will be in yellow.' 'We have been both to the exhibition and Sir J. Reynolds'; and I am disappointed, for there was nothing like Mrs. D at either. I can only imagine that Mr. D prizes any picture of her too much to like it should be exposed to the public eye. I can imagine he would have that sort of feeling,—that mixture of love, pride, and delicacy.' [via The Letters of Jane Austen]

But I believe (and Mullan agrees) that in Austen's novels, how the characters look to each other matters far more than how they appear to us, the readers. There is no real benefit to dwelling on the specifics of a particular character having a certain colour eyes or hairstyle if it isn't clear how other characters feel about their appearance. It might help the reader, yes, but perhaps at the expense of the plot... there are only so many ways you can describe eyes before you veer into 'cerulean orbs' territory.

Personally, I also love this vagueness (as I previously discussed here) as it means you can project literally any face onto your character of choice and no one can stop you or prove that it wasn't what Jane Austen intended. Very underrated aspect of the appeal of her heroes and heroines, imo.

I'll add the relevant passages that deal with P&P and S&S from Chapter 4 of What Matters in Jane Austen, 'How Do Jane Austen's Characters Look?' below the cut as I think it's a very interesting discussion:

We do not know, for instance, even the colour of these heroines' hair. How people look is often suggested rather than specified in Austen's novels. Why should she not tell us? Perhaps because she would have us, like Laurence Sterne in Tristram Shandy, imagine an attractive woman to meet our own requirements: 'Sit down, Sir, paint her to your own mind-as like your mistress as you can—as unlike your wife as your conscience will let you." But Austen wants us to think not so much about how characters look, but how they look to each other. Her sparing use of specification when it comes to looks is striking when looks can be so important. Think of the Bennet girls, who must rely on their personal attractions to win them some kind of financial security and social standing. When Jane Bennet becomes engaged to Mr Bingley her mother exclaims, with embarrassing glee and yet also honesty, 'I was sure you could not be so beautiful for nothing! (Pride and Prejudice, III. xiii). There is the sense confessed quietly throughout Austen's narrative that looks are hugely important (thus those words used so frequently about characters when we first meet them: handsome, pretty, gentlemanlike, elegant). Austen herself is too honest not to mention a character's looks when he or she is introduced to us. And yet there is often the sense for the reader that looks are difficult to catch, elusive, unspecifiable. This is partly because Austen wants to avoid the strained formulae of other novels.

For most novelists of Austen's age and earlier, a heroine's looks belong with her predictable parcel of virtues. In the first chapter of a novel that Jane Austen certainly read, Mary Brunton's Self-Control (1810), we find that the heroine, Laura Montreville, is possessed of 'consummate loveliness', cheerful good sense' and 'matchless simplicity'. There is a ready vocabulary of superlatives for any novel heroine, for her virtues and for her attractiveness. Austen needed to escape such a vocabulary, and thus came her interest in the indefinability of some of her most important characters' looks. (One of her tricks is to save her precise descriptions for minor characters.)

The elusive qualities of Elizabeth Bennet's looks are explicitly discussed in Pride and Prejudice, taken up by Mr Darcy when he responds to Miss Bingley's sarcasm about adding her to the portraits in Pemberley: "*... what painter could do justice to those beautiful eyes?" "It would not be easy, indeed, to catch their expression, but their colour and shape, and the eye-lashes, so remarkably fine, might be copied'' (I. x). The difficulty of catching the 'expression' of Elizabeth's eyes is evidence of their beauty, and the detection of this difficulty is proof of Mr Darcy's attraction to her. Later he talks to Elizabeth about her trying to 'sketch' his 'character', and she talks of trying to 'take your likeness', as if the most appreciative judges of other people - especially other people to whom they may be attracted - are those who know how hard it is to render a likeness.

Elizabeth's eyes in Pride and Prejudice captivate Mr Darcy. We remember finding out in Chapter vi that she does not please Mr Darcy's taste. 'But no sooner had he made it clear to himself and his friends that she had hardly a good feature in her face, than he began to find it was rendered uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of her dark eves.' That 'made it clear to himself' is wonderfully satirical: he convinces himself against the pressure of an unstated allure. The eyes have him. Mr Darcy's judgement also alerts us to the feature of a woman that we are most likely to find out about throughout Austen's fiction. We are told of Anne Elliott's mild dark eyes', and of Fanny Price's 'soft light eyes' ...... Marianne Dashwood's eyes naturally reveal her personality, but also have an unusual colour that makes her allure singular: in her eyes, which were very dark, there was a life, a spirit, an eagerness which could hardly be seen without delight'

#jane austen#pride and prejudice#elizabeth bennet#mr darcy#sense and sensibility#emma woodhouse#classic lit#inbox#the-anonymous-unikitty#cora reads#despite the vagueness people have Very Strong opinions on how characters look and i think it's fascinating#because we genuinely don't know but the strict adherence to headcanons is very endearing#tbh i realise i hc most heroes and heroines with dark eyes and dark hair (like me) lol#i don't like Blond Men... idk why but absolutely not having ANY austen hero be blond sorry#don't mind about the heroines though!!#such a great book though. has a chapter on the weather because of COURSE it's a massive part of a british author's stories lmao#if there's one thing about the brits it's that we love complaining about the weather#but i never really thought about what a critical part it plays throughout emma. fascinating. fully recommend the book!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be fair to Mr. Darcy in "Pride and Prejudice", I would also probably appear rude, proud, and altogether snobbish if I was stuck with the knowledge that everything I said was going to be fawned over or criticized by Mrs. Bennet, Caroline Bingley, Mr. Collins, or Lady Catherine. Like, he IS being a genuine snob at points and rightfully gets called out for it, but it definitely doesn't help that for the majority of the first part of the book, most of Darcy's conversations with Elizabeth happen when they're trapped in rooms with some of the Most Annoying People Alive.

POV: You are Fitzwilliam Darcy and cannot help but be intrigued by Elizabeth Bennet, a young woman with fine eyes and a lively manner. You would like to get to know her better. Unfortunately, Mr. Collins is here too, and he will tell Lady Catherine literally Every Single Thing you say.

451 notes

·

View notes

Text

Such an exhibition

I have been thinking about the breakfast scene in Pride & Prejudice. You know the one:

“Yes, and her petticoat; I hope you saw her petticoat, six inches deep in mud, I am absolutely certain; and the gown which had been let down to hide it not doing its office.” ... “You observed it, Mr. Darcy, I am sure,” said Miss Bingley; “and I am inclined to think that you would not wish to see your sister make such an exhibition.” “Certainly not.” “To walk three miles, or four miles, or five miles, or whatever it is, above her ankles in dirt, and alone, quite alone! what could she mean by it? It seems to me to show an abominable sort of conceited independence, a most country-town indifference to decorum.”

It strikes me that there are some nuances that people often miss when talking about this. The first is that Miss Bingley attributes this "conceited independence" not to a flaw in Elizabeth personally, but to the difference between the manners of the country gentry (such as the Bennets) and the fashionable people who live in cities (like the Bingleys). In town, fashionable and wealthy people did not walk long distances. Fashionable people either owned horses/carriages, or took cabs. They would walk in parks where it was fashionable to walk. But they rarely walked alone, especially women. A man might walk to his club alone, in the afternoon, but when walking home from his club that evening he would hire a man to walk with him to discourage pickpockets and muggers. Even in posh neighborhoods!

But in the country ... there aren't cabs, and while there were robbers on the highways who would stop carriages to steal from them, they weren't lurking along footpaths such as the one Elizabeth would have taken. Elizabeth didn't ride horses, and her father is of the lower gentry, which means that the same horses which pull the carriage also work in the fields, and thus the carriage is not always available. Even when it is available, she's one of five daughters. If her dad or mom wants it, they get it; if she or her sisters want it, they have to argue over who gets it. And riding in a carriage was jolting and unpleasant (bad roads and no shock absorbers). So Elizabeth, like many members of the country lower gentry, often walks when she wants to go visit her neighbors.

Then there's the "alone" part. Everyone can quote "six inches deep in mud" but we forget that part of what shocks Miss Bingley is that Elizabeth walked by herself. In Regency England, the more wealth and status a woman's family had, the less often she would be alone. And again, big difference between the city and the country. In the city, a woman of Elizabeth's family status would never go anywhere alone. Either she'd have a female relative with her, or a friend or chaperone, or a servant. For protection, and also to vouch for her propriety. In the country ... as long as she's going to visit another woman, or just going out to walk for the exercise, and she's not going too far, nobody bats an eyelash. This is true both at Longbourn and also at Hunsford. If she were wealthier, that would not necessarily be the case; both Georgiana Darcy and Anne de Bourgh have companions who are paid to go where their mistress goes. So it's not just that Elizabeth is walking that shows the difference between town and country manners, it's also that she's walking alone.

Miss Bingley is criticizing Elizabeth in particular, but she is also criticizing her class, as a way of asserting both that the Bingleys have better manners than country gentry (despite their money coming from trade), and by appealing to Mr. Darcy about it she is also positioning herself as closer to his sphere and manners than to anyone else's.

Then we come to the question of how much does Darcy judge Elizabeth's actions. Mr. Darcy says he wouldn't want Georgiana to do what Elizabeth has done (walk three miles alone through muddy fields), but there's a big difference between the upper gentry and the lower gentry. Georgiana probably has her own horse, and she's much less likely to have to worry about whether the carriage horses are needed on the farm, and also she has someone who is literally paid to go with her everywhere. Also, Georgiana is sixteen years old, has already been targeted by a fortune hunter, and is very shy and timid. So the fact that he wouldn't want Georgiana to do it doesn't mean he necessarily sees it as a big deal when Elizabeth (older, not as wealthy*) does it.

*People sometimes claim the Bennets were either poor or middle class. They were at the bottom of the gentry, but that is still quite wealthy. Mr. Bennet has an income of £2,000/year, which is peanuts compared to Darcy. However, let us compare them to other people in their day. William and Dorothy Wordsworth spent the 1790s with an income of about £170-£180/year, with reasonable comfort. P&P was written in 1796-1797, so about the same time.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a gift 🎁 link, so there is no paywall to read the article. Below are some excerpts.

By Esther Zuckerman | April 18, 2025

Say “hand flex” to a fan of the 2005 adaptation of Jane Austen’s “Pride & Prejudice” and they will know exactly what you mean. The gesture comes early in the director Joe Wright’s sumptuous version of the story. Keira Knightley’s bold Elizabeth Bennet is leaving Netherfield Park after picking up her ill sister Jane (Rosamund Pike). The reserved Mr. Darcy, played by Matthew Macfadyen, helps Elizabeth into a carriage. She had previously overheard Darcy insult her, calling her “tolerable,” and the tension between them is palpable. But when he touches her, something happens. She looks down, her gaze lingering on his gesture. As he walks away, the camera captures Darcy’s hand. His fingers stretch outward like an impulsive, unconscious tic. Her touch is almost too intense for him to handle. In the nearly 20 years since the film came out, the hand flex has become perhaps the defining beat from Wright’s take on the novel. It’s the subject of countless social-media posts, critical essays and TikTok dissertations. Search “hand flex” on TikTok or X and you’ll find the term even being applied to scenes from other films and TV shows. “This is my equivalent of the hand flex” is shorthand for “this tiny gesture gives me butterflies.” The word I kept encountering when talking to people and reading about the hand flex is “yearning.” Darcy, in the early phases of the story, keeps up a mask around Elizabeth, but his subconscious actions reveal just how much he desires her. To many, it’s devastatingly hot. And now, for the anniversary rerelease of “Pride & Prejudice” on April 20, the hand flex is commemorated with official merchandise.

#pride and prejudice#hand flex#matthew macfadyen#keira knightley#elizabeth bennet#mr darcy#esther zuckerman#the new york times#video#my edited gifs

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

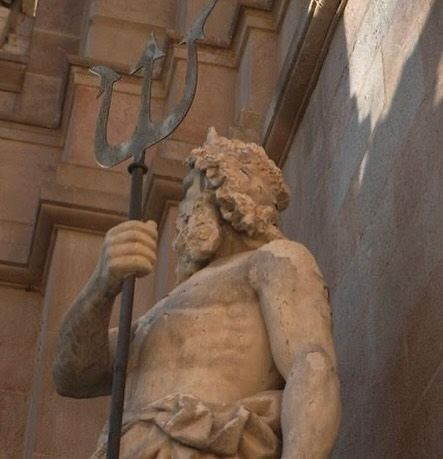

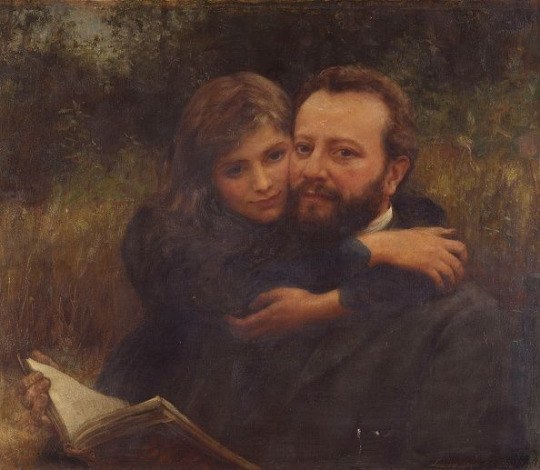

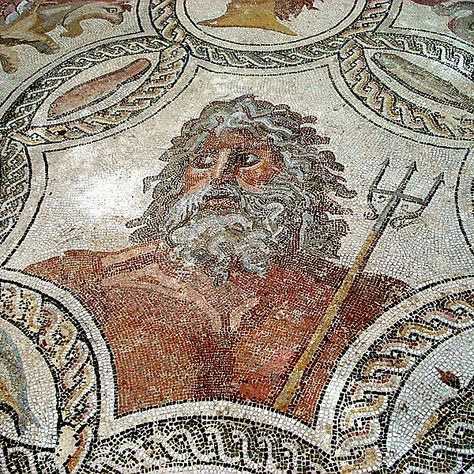

✮ ⋆ ˚。𖦹 ⋆。°✩ poseidon + yoshi moodboard ✮ ⋆ ˚。𖦹 ⋆。°✩

𓇼 relationship — father and daughter

is there anything so undoing as a daughter?

𓇼˖。°๑ playlist 𓇼˖。°๑ 1. die your daughter — susannah joffe 2. like him — tyler, the creator 3. marjorie — taylor swift 4. glimpse of us — joji 5. fourth of july — sufjan stevens 6. this is me trying — taylor swift

𓇼˖。°๑ analysis 𓇼˖。°๑ if you couldn't tell, poseidon has a hard time facing his regrets re: leaving our family. I do genuinely look like Sally, so it's even more hurtful for him, especially when I'm upset with him. but we're father and daughter, and we do have a good relationship. we're both trying here. he has an easier time connecting with me than he does percy. in childhood, it always felt like our father lingered around, hence marjorie, though I had no idea how true that was until I turned 18 and we found out we were demigods.

the fictional relationship that best describes us would be viserys and rhaenyra — poseidon is more or less uninvolved in my childhood due to focusing on his duty and responsibilities of his station. it wasn't until the time came for me to learn the truth of my identity (paralleling viserys telling rhaenyra the song of ice and fire) that poseidon became a present figure in my life. my mother and his previous relationship hangs over us like aemma does over them. in my dr, where percy is meant to be a warrior and hero, I am taught to explore the more political aspects of the olympian and mythical world, like viserys raises rhaenyra to be queen. at the same time, poseidon can be very critical of me just as viserys once was with rhaenyra before she married — once, he told me "we must act as befits our station. Zeus watches us all." even in our hardest moments though, poseidon is very protective over me and proud. also paralleling viserys and rhaenyra, I seem to be his closest child, perhaps to the neglect of his other children.

𓇼˖。°๑ fictional parallels 𓇼˖。°๑ note: in no particular order 1. king viserys and rhaenyra targaryen — hotd 2. david charming and emma swan — ouat 3. haymitch abernathy and katniss everdeen — thg 4. luke and rory — gilmore girls 5. mr. bennet and elizabeth bennet — pride and prejudice (2005)

𓇼˖。°๑ want to explore more?

moodboard + playlist for my dr

moodboard + playlist for me and percy

moodboard + playlist for me and sally

moodboard + playlist for me and my s/o

follow #yoshi of cabin 3 for more of this dr

check out my other drs here

#reality shifting#shiftblr#shifting realities#quantum jumping#anti shifters dni#desired reality#shifting antis dni#shifting blog#pjo shifting#yoshi of cabin 3#pjo shifter#percy jackson shifting#pjo dr#shifting reality#shifters#shifting#shifting community#shiftok#reality shifter#shifting script#shifting consciousness#original reality#percy jackson shifter

36 notes

·

View notes