#monaco gp 1975

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

niki lauda, mario andretti, john watson, james hunt // monaco - may 11, 1975 📷 motorsport images

#niki lauda#james hunt#mario andretti#john watson#f1#vintage f1#classic f1#ferrari#hesketh#surtees#parnelli jones racing#monaco#1975#1970s#1975 monaco gp#monaco gp 1975

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Watson on the racers he knew - from Motorsports magazine

Ronnie Peterson:

Ronnie, first of all, was a good friend. He was an exceptionally quick racing driver, and one of his great skills was he could jump into anything and drive it quickly. He wasn't as adept at developing a car. Ronnie's skill was phenomenal car control, balance, natural speed, but most of all he was a genuinely lovely person. Lots of drivers have lost their lives and I've never been upset. But Ronnie's death upset me. I still feel it now.

Jody Scheckter

James Hunt called him Jonathan Livingston Seagull, after a book which is an allegorical fable about a seagull with ambitions beyond flying and scavenging with the flock. I met Jody when he came across in the early 1970s and he was wild. A high level of driver ability. In 1973 at the French GP he and Fittipaldi had a collision. He was a loose cannon then, a little like Riccardo Patrese a few years later. But following Watkins Glen that year he was transformed after being one of the drivers who stopped at the scene of François Cevert's fatal accident. What he saw had a seminal change on his outlook and philosophy of being a racing driver. He said later that it brought home to him that the sport he loved could kill. Jody wasn't someone I had much to do with in the paddock, but I'm not sure he had much to do with anybody.

Bernie Ecclestone

He made a profound impact on me, not necessarily as a team leader, but he's a pragmatic and lateral thinking person. Again, Watkins Glen 1973 and Cevert's accident... a wonderful, beautiful gut lost his life and it felt disrespectful to jump back in the car and go back out. That's what I believed, how I was brought up. And Bernie said, "Get in that car, you're here to race. Whatever happened to François it's over and what you are doing is not going to make any difference." It helped me throughout the rest of my career, when a driver was injured or killed. I was able to erect a kind of barrier around myself. It enabled me to put up a blinder to however awful or ugly it may have been, to get back into the car and race. At Niki's accident at the Nürburgring in 1976, I was one of the early cars through and I had him lying with his head on my thighs, looking into his fave and comforting him as best I could. Then I had to jump back into Mt car and do a Grand Prix. I never gave it a second thought. That was the influence Bernie had on me, to detach emotion from what is your job. If you can't do it, get out. Later I had the same thing with Gilles Villeneuve at Zolder. I saw his body in the catch-fencing. I looked in his eyes and the lights had gone out. I got back in the car, drove back to the pits, told Teddy Mayer and John Hogan, and went for a coffee. Nothing. If a psychologist heard me say that, they would claim there is something wrong with me, to have that high level of detachment. But soilders, firefighters, the police - they need such mechanisms. You have to find what works best for you. That was Bernie's influence on me.

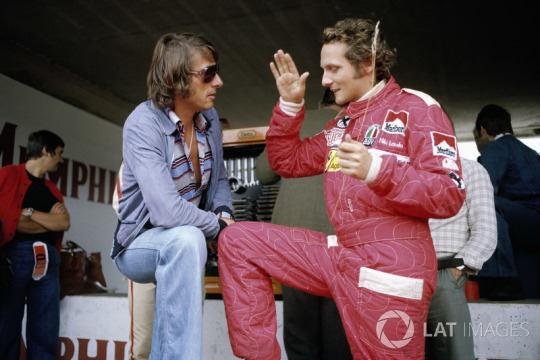

Niki Lauda

The Niki of the 1970s was very driven, very focused and very ambitious. He had a vision of where he wanted to be and how to get there. When he drove for March initially it wasn't a particularly good car, then he jumped ship to BRM and did an extremely good job. Monaco in 1973, he was outstanding. But he saw through Louis Stanley and realised the team was essentially going nowhere. He needed to move on to a better place, and he's done enough to attack Ferrari's interest. He formed relationships with key people in the team who become 'your' people. He did that with Mauro Forghieri and Luca Di Montezemolo and might have won the world title in 1974, but was going through a process of learning how to get there. By 1975, with the car he then had, he had done all his learning.

James Hunt

James was a pure animal, a pure athlete. He turned out to have a lot of skill, probably against many people's expectations. I saw him first in 1973 in the March at Monaco where he did a brilliant job. He was a bit of a contradiction in many respects because he seemed to have all the ability and skill, and a huge amount of intelligence as well which is fundamental. He was also a caged animal that needed to be controlled and some teams, principally McLaren, saw how to do that, holding him back and the lighting the blue touch paper and letting him go. What Teddy Mayer realised in 1976 was, don't let James screw around with the car, just get a good balance and throw rubber at it. James was like a lion trying to eat you alive. Bang, out he'd go and he'd deliver incredible laps. The other thing about James, in spite of his off track behaviour, he was a fit guy who played a lot of sports at very high level as an amateur. He was mercurial in that second half of the 1976 season. OK, he had a very good car in a very good team, but he dragged out every last ounce of performance from that car.

#classic f1#f1#niki lauda#formula one#formula 1#vintage f1#james hunt#bernie ecclestone#ronnie peterson#jody scheckter#john watson

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

1975 Monaco GP 🏁

On-board with Emerson Fittipaldi 🇧🇷 in his McLaren M23 Ford.

#classic #Formula1

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

GP de Monaco, Monte-Carlo, Niki Lauda 1975

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

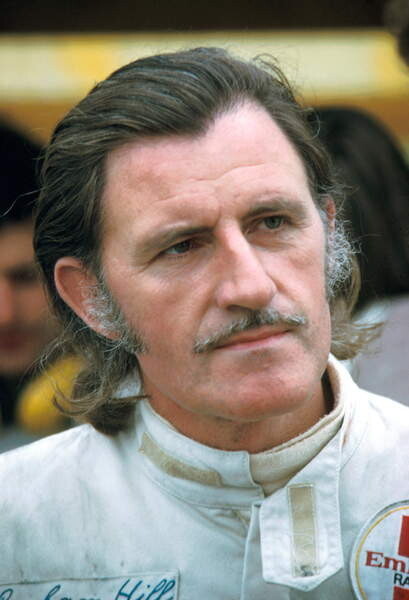

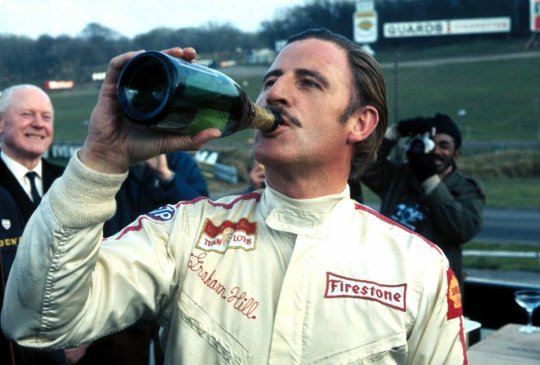

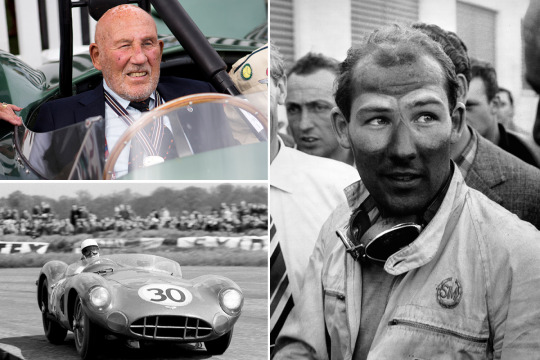

Because of the last weekend's Indy 500 and Monaco GP I wanted to pay tribute to the only Triple Crowned driver and one of the goats- Graham Hill. Born in 1929 and sadly passed due to a plane accident in 1975 at the age of 46.

Mr. Monaco won there in 1963, 1964, 1965, 1968 and 1969.

In the meantime he won Indianapolis 500 in 1966.

He achieved the Triple Crown in 1972 by winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

The 2 times world champion got his titles in 1962 and 1968.

The reason why it's so impressive to me, is how different those 3 events are and it makes me fall for Motorsport even more. F1 is great and there is so much more to add on it. That's why I patiently wait for Fernando Alonso to be the second in history universally the best driver. Or my prayers will be listened and one day it will be Max Verstappen🤞🤞.

#f1#formula 1#graham hill#indy 500#indianapolis 500#triple crown#monaco gp#monaco grand prix#24 hours of le mans

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life In The Fast Lane - Prologue

Rating: Teen & Up

Warnings: None apply

Pairings: Original Female Character(s)/Original Male Character(s); OFCs & OMCs

Work Tags: Re-write of a previous work; Mentions of IRL current and past F1 figures; Eventual romance; friends to lovers; found family/work family; actual family; racing drivers and their various shenanigans; how to handle pressure (and how not to); with a sprinkling of the power of friendship; tags will be updated as work progresses

Word count: 802

One

The Guardian – 8th January 2016

Motorsport pioneer Maria Teresa de Filipps, the first female Formula One driver, has died aged 89.

The Italian driver, from Lombardy, participated in five Grand Prix across 1958 and 1959, making her debut at the 1958 Monaco Grand Prix in a privateer Maserati. Across her three Grand Prix starts, her highest placing was tenth at the Belgian Grand Prix that same year, though she failed to score any points.

de Filipps was appointed Vice President of the Club of Former Grand Prix Drivers in 1997, and in 2004 founded the Maserati Club, later becoming its Chairperson.

Two

F1 Weekly Newsletter

This week on our dive into the F1 archives, we’re putting the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix under the microscope.

Contested at the Montjuïc Street Circuit in Barcelona, you may know that it was won by Jochen Mass, with Jacky Ickx and Carlos Reutemann rounding out the top three… but today we’re focusing on the driver who finished in sixth place.

Italian driver, and more notably the second female driver to compete in Formula 1, Lella Lombardi.

Lombardi is still to this day the most successful female driver in Grand Prix history, having scored just half a point at the 1975 Spanish GP, as the race was red flagged after 29 laps. Her career spanned 12 races across 17 entries, driving for March, RAM, and Williams. Her last race was the 1976 Austrian Grand Prix, where she finished twelfth.

Three

17th October 1989 – The Sword and Lion, Oxford

“Okay and last question for the sports round,” A hushed washed over the pub, as the groups sat round almost every table leaned back in their seats to try and hear better. “Who is the only British female Formula One driver?”

The hush was replaced by a sea of confused murmurs.

“A female F1 driver?” One patron exclaimed in complete disbelief.

“There’s never been a woman in F1 it’s a trick question!” Another huffed with their arms folded across their chest.

“The answer, was Divina Galica. She took part in three race weekends, the 1976 British Grand Prix and the Argentine and Brazilian Grand Prix in 1978, though she never qualified for those races. She also competed in four Winter Olympics as a skier”

Four

7th April 2010 – Brands Hatch Circuit

Rain came pouring down at the race track on a very cold, grey Spring day. It was the middle of the week, so the circuit sat empty, bar a handful of people in offices in the main pit building doing paperwork.

The Desiré Wilson grandstand sat right at the end of the start/finish straight, looking across Paddock Hill. As it got pelted with rain some looked out of their windows at the grandstand, and let out a small sigh before continuing on with their work.

Better known for her career in sportscar racing than her one race entry at the 1980 British Grand Prix, Desiré Wilson had won the race at Brands Hatch in the 1980 British Formula One championship. While completely separate from the series it was named after, it was still an astounding enough achievement that merited a grandstand being named in her honour.

Rain continued to fall for the rest of the day, and as the last of the office staff left, the grandstand stayed where it always had been, looking out over the circuit.

Five

BBC Sport F1 Column

The fifth and still final female driver to compete in Formula 1 was Italian racer Giovanna Amati. She signed with Brabham for the 1992 season, alongside Eric van der Poele from Belgium.

She first drove an F1 car the year prior, driving 30 laps in a Benetton at a private test, prior to signing with Brabham. Amati became the first female driver in twelve years to take part in a Grand Prix weekend at the first race of the season in South Africa.

Her career was sadly short lived, as she failed to qualify in the first three races of the 1992 season, which resulted in Brabham replacing her with Damon Hill, who also failed to qualify in the next five races.

Amati had a brief spell in sportscar racing, before her retirement. She briefly worked as a television commentator and wrote columns for various Italian motorsport publications.

It would be another 24 years before Formula 1 would see another female driver compete in a Grand Prix weekend, when British driver Susie Wolff drove in first practice for Williams at the 2014 British Grand Prix (she went on to drive in three more practice sessions before announcing her retirement from racing).

This weekend sees the driver-less streak broken again as Amy McDonald will drive for Renault in the first practice session at this week’s Spanish Grand Prix in Valencia.

It is unclear if or even when Formula One will see a female driver permanently racing in the sport. Attitudes towards female drivers have come a long way thanks to the likes of W Series, and Formula 1’s own feeder series F1 Academy, though many questions still remain at just how competitive a female Formula 1 driver could be, if one was ever given the chance.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MONACO, 1975 — Niki Lauda, Ferrari 312T.

#f1#niki lauda#monaco gp 1975#scuderia ferrari#ferrari 312t#1970s#ph#*ph#*m#*ferrari#scrapbooking#1975

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

No one asked for this, but here are some facts about Bono:

Since some people are still a bit confused, his real name is Peter Bonnington. Bono is just a nickname given to him by his colleagues

He was born on 12th February 1975

He’s British (obviously, I mean, you heard his accent, right)

The position he holds now is a senior race engineer. He started as a data scientist with Jordan GP in early 2000s

Then he joined Honda as an understudy to Andrew Shovlin and became Jenson Button’s performance engineer

At Brawn GP he guided Button to his first and only WDC

His first time as a race engineer was at Monza GP in 2010, when he replaced Mark Slade as Michael Schumacher’s engineer

In 2011 he became Michael’s race engineer

He’s been Lewis’ engineer since 2013, so from the beginning of Hamilton’s time at Merc

He was the one to invent the catchphrase “It’s Hammertime”. He came up with it when radio restrictions were still quite heavy, so he had to figure out how to suggest Lewis to push

Toto Wolff jokingly revealed that Bono sometimes takes a coffee break during the race to escape from Lewis’ complaining for a while

Bono called successful communication with the driver “a bit of an art”. He also said that he knows Lewis so well they are second-guessing each other’s thoughts now

Lewis stated he wouldn’t be able to achieve his 7 titles without Bono

This is what Peter looks like for anyone who doesn’t already know:

Trivia:

Bono’s left-handed

He really likes spicy food (but like spicy SPICY)

He has a dog <3

He prefers two wheels than four. Asked if he prefers a car or a bike, he said “bike all the way, either me pedaling or with an engine. Two wheels is my passion”

He loves Monaco, especially the mountains. He loved going out on his road bike there. He said that climbing 900 meters vertical was “a good fun”

He also likes Singapore because of different time zones. He humorously said he discovered that he had much more free time while working at night and sleeping during the day

Other places he really likes to visit are Austin and Budapest

#YES this is a Bono stan account#i can talk about him all day#this man is a blessing#Toto give him a raise#NOW#i wonder how Bono hides his angel wings#peter bonnington#bono#f1#formula 1#formula 1 race engineer#race engineer#mercedes#mercedes amg#mercedes f1#lewis hamilton#michael schumacher

611 notes

·

View notes

Text

Niki’s “office” for the 1975 Monaco GP

The only computer here is the man behind the wheel

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

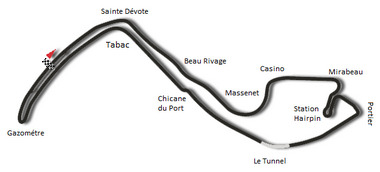

Changes to the Monaco Circuit over the years

1929 - 1972

A few chicanes were added and changed slightly over this time as well as some resurfacing for safety measures but other than that it stayed the same.

1973 - 1975

The train station at the hairpin along with the old tunnel were removed in 1973 and were replaced with a modern hotel complex, and land reclaimed from the sea created a circuit extension around a new outdoor swimming pool. A new narrow curve around the Rascasse restaurant replaced the gasometer curve, while the additional space regained from the sea allowed for a permanent pit lane for the first time alongside the start/finish straight.

1976 - 1985

In 1976, alterations were made at Rascasse and Ste Dévote to slow the cars,

1986 - 1996

In 1986 the left-right chicane (Chicane du Port) which had increasingly been taken at alarming speed was replaced with a new chicane (Nouvelle Chicane), closer to the tunnel exit. This again included land reclaimed from the harbour, giving the benefit of space for a small area of run-off. It slowed the cars considerably, though a bump on entry ensured this was still a tricky section of track.

1996 - 2021

In 1997, the original S-bend around the swimming pool was redesigned, with the barriers moved further back. The new section was named 'Virage Louis Chiron' in honour of the 1931 GP victor and long-time clerk of the course.

The next phase of new work only affected the southern side of the port. Some 5,000 square metres of land were reclaimed from the sea. The circuit between the second part of the swimming pool section and La Rascasse was moved 10 metres and completely redesigned.

The S-bends at the exit of the swimming pool section were tightened into a slower right-left chicane. The following year saw the opening of a new, much wider pit lane with by building over the old track between the swimming pool and La Rascasse. This provided 250 square metres of extra pits space for the teams – though they still remain amongst the most cramped on the F1 calendar

Looking at this circuit it is absolutely insane how little it has changed in nearly 100 years of racing around the streets of the principality.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture by oldschoolf1 on instagram

A small Formula 1 history lesson.

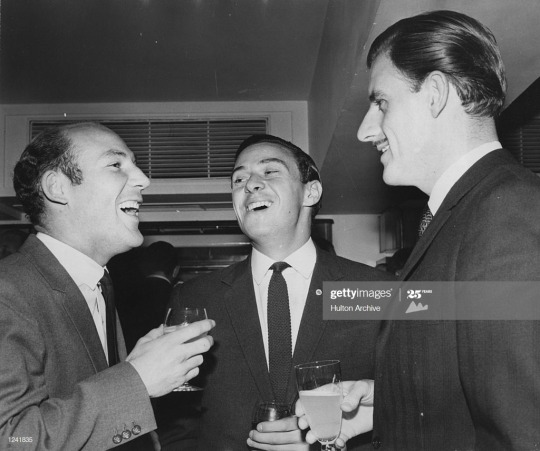

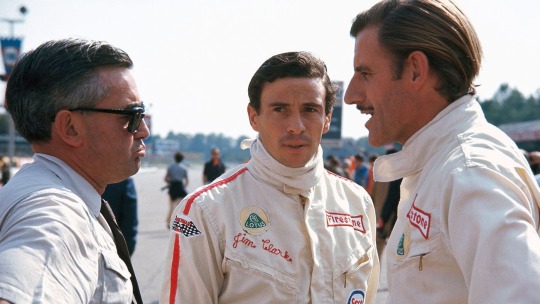

Left to right:

1. Jochen Mass 🇩🇪 (*30.09.1946 LeMans Winner 1989, 1 GP-Win in F1 1975 Spain)

2. Ronnie Peterson 🇸🇪 (*14.02.1944 ✝️11.09.1978 Vice World Champion 1971, 1978 F1, 10 GP-Win, F2-Europe Winner 1971)

3. Graham Hill 🇬🇧 (*15.02.1929 ✝️29.11.1975 👑 (LeMans 1972, Indy 500 1966, Monaco GP 1963, 1964, 1965, 1968, 1969), 2 Worldchampionships, 14 GP-Wins)

4. Niki Lauda 🇦🇹 (*22.02.1949 ✝️20.05.2019 3 Championships, 25 GP-Wins)

5. Clay Regazzoni 🇨🇭 (*05.09.1939 ✝️15.12.2006 Vice World Champion 1974, 5 GP-Wins)

Text by f1.history.meme on instrgam (me on instagram)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

penman47 asked: Your pages on Stirling Moss and Graham Hill have brought back fond memories of my passion for Formula 1 racing and the Grand Prix races from 1963 through1972. Mechanical failures often plagued Stirling Moss, Graham Hill and Jimmy Clark as man put machine to test. My question would be who of the three would come out on top driving the same mechanically perfect car at say the British Grand Prix Silverstone.

Thank you for your question @penman47

I received this question just before the sad news about the recent untimely death of the legendary Sir Stirling Moss. It feels prescient to respond now after a bit time to pass to reflect with a more sober perspective rather than let sentiment and emotion cloud any judgement.

In my family we are, it is fair to say, racing nuts. My grandfather had the racing bug and drove classic cars at amateur meets like Goodwood through his friendship with Freddie Richmond and was involved heavily in the RAC Club. He was fortunate to see all three of these racings icons race. He saw all of Jim Clark’s five victories at the British Grand Prix and regularly went to Monaco to see Graham Hill win there five times. He saw Stirling Moss race too and he was there for the Glover Trophy at Goodwood in 1962 when Stirling Moss had his career ending accident. Without taking anything away from the modern era drivers like Alain Prost, Ayrton Senna, Michael Schumacher, and Lewis Hamilton - all of whom he thinks are a credit to motor racing - he is very much of his era. As a proud Scots, he thinks Jim Clark was the best he ever saw.

My father got the racing bug too but was more of a Le Mans fan when he was growing up because spectators were closer to the action than F1. He had inherited and also built up his own classic car collection that he sometimes races at Goodwood. He was a wee laddie when he saw Clark and Hill race but he doesn’t fully recall because he was too young to fully remember. He loved watching James Hunt, Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost but had a grudging respect for Nikki Lauda. He never saw Stirling Moss race but knew him quite well through Goodwood and at the RAC Club in London. I know his head says Jim Clark but his heart says Stirling Moss was the best British driver.

For one of my older brothers, who has a thing for speed as I do, he was always a big Ayrton Senna fan. Again as a small boy he saw Ayrton Senna race and was part of the converted to consider him as the greatest driver of all time. Senna’s bravery was his own inspiration to take part in the Dakar Rally and other endurance races.

It’s indeed one of my unmet ambitions to ride in the Dakar Rally but it’s always been on the back burner. I would like to ride with my brother because he has the experience but he and I are too competitive and we would fight over who was the better driver - for the record, I know I am.

My mother - being Norwegian - is left to make dry sarcastic remarks about boys and toys whenever my grandfather, father and us siblings talked about racing. But she’s not immune to the glamour of F1 racing either. I’ve been told by my aunts that when my mother was at her Swiss boarding school, and later learning to be a ski instructor in the Alps, she would descend upon Monaco during the Grand Prix with her friends and enjoy the social side of racing i.e. the partying side of Formula One racing. But she’s quite buttoned up about her partying past. Meanwhile she and my other siblings continue roll their eyes when the subject of racing comes up.

But speaking for myself, speed has been my drug of choice and flying combat helicopters in the army for a time helped satiate that need. When I left I felt empty and bereft. But if flying single craft planes and gliders gives me weird sense of peace these days (when I can make the time to do so), I get a decent rush from riding motorbikes hard and fast on the open country roads (forget about the urban traffic congested cityscape). Racing the odd fast car I managed to get my hands on through pliant boyfriend or good friend has given me a brief thrill too but it’s been spoiled often with my driving companion screaming in my ear or pissing their pants as I take the turn hard. With my penchant for crashing - tsk, more like a graze - I’m not allowed any where near my father’s classic cars.

I have been to Grand Prix races, including ones at Silverstone, Spa-Francochamps, Singapore, Shanghai, Suzuka, Yas Marina, Monza, and Monaco, from the time I was at boarding school. I would either go as a guest of my grandfather or father or even with some school friends who lived in Monaco and had links to get entry into the drivers’ paddock. But these days it’s more likely because of wrangling a corporate hospitality invitation that I would have the chance to go - sometimes if I plan my calendar fortuitously and Lady Luck smiles upon me I can catch two birds with one stone e.g. do a business trip to Shanghai and stay on to see the Shanghai Grand Prix. So I follow racing avidly if I can. For me of course the amazing Lewis Hamilton is the driver of our generation along with Michael Schumacher’s imperious reign at the top. And I do like the cut of Max Verstappen’s gib too.

Of course it’s hard for me to credibly assess who was the better driver between Stirling Moss, Graham Hill, and Jim Clark because I wasn’t a direct witness but not many today were either. But I consider myself a racing fan and I have seen old footage. I have also read about the history of Grand Prix racing and listened to others whose expert views I respect. So I hope what I offer is just an educated opinion at the end of the day but I recognise the heart will come into it because racing - at least in the vintage years - was quite romantic even as it morphed into something more glamorous in later decades.

Anyway, your question just added more fuel to the fire in our family discussions over our recent Zoom calls.

I have to say upfront that I consider Jim Clark as the greatest British driver of all time. I’m with my grandfather on this one and I always enjoy playing contrarian to my father(!). But all things considered Jim Clark was on a different level to both Stirling Moss and Graham Hill. And why I think so I hope I can lay that case out below.

It’s important to put all three drivers in their racing context.

Firstly, they all didn’t race at their peak at the same time and in the case of Moss in a different era. But there was some overlap between Moss and Clark and Hill. Stirling Moss had active career from 1951-1961. Graham Hill had his active years between 1958 to 1975. And Jim Clark was only active for eight years from 196O to 1968.

Secondly, unless you’re a racing fan or have seen old film footage, it really is hard to convey to our present times just how dangerous driving was in that era. It was known as the Killer Years in Formula One history. Back in the days when the British government leached up to 97 per cent from a race driver’s income, a racer had at least a 40% chance of dying at the wheel, so tragedies were commonplace. Some prodded the tiger once too often and ran out of luck. It really is hard for us to fathom the extreme danger Grand Prix drivers put themselves under when they hared around the track as one mistake might well cost them their life or a body of broken bones.

And thirdly, it may sound simple to say this, but they drove extremely fast at very high speeds. The temptation again is to look at vintage racing cars in the light of modern super engineered racing cars and think they were easy to drive.

Few drivers in the history of motor sport can prove they’ve won the elusive Triple Crown. Only Graham Hill can. Formula One world champion in 1962 and 1968; winner of the 1966 Indianapolis 500; winner of the 1972 24 hours of Le Mans and five time Monaco GP winner. An incredible achievement that underlines the fact that Hill was one of the most complete drivers of his time. He was fast, but not the fastest. Talented, but not the most talented. The best, but not always and everywhere. Explosive, but predictable. Professional, but with enough self-mockery to pull his pants down at dinner parties, running up and down the tables. Hill drove his cars throughout the most dangerous years of the sport. Calmly and reserved, while he tried to fight off virtuoso's like Jim Clark, Jochen Rindt and Jackie Stewart.

When Stirling Moss drove on the track, he was there to race, not to eke out championship points. And to do it fast, faster than anyone else. For a driver whose competitive peak coincided with one of motor racing’s most dangerous periods when death regularly stalked all drivers, a time when average lap speeds escalated while safety precautions stood still, Moss’ courage and achievements were even more astonishing. Moss knew all about that: witness the serious leg injuries he suffered during practice for the 1960 Belgian Grand Prix, a race in which compatriots Chris Bristow and Alan Stacey both died, or the career-ending aftermath of his accident during the 1962 Glover Trophy at Goodwood.

But for his own unswerving sense of fair play, he could have pipped Mike Hawthorn to become Britain’s first world champion in 1958. Moss won four races to his rival’s one, but the latter benefited from greater reliability and consistency. The pivotal moment came in the Portuguese Grand Prix, from which Hawthorn was initially stripped of second place for receiving a push-start after slithering off the track. Moss was among those who came to his defence.

To this day Moss has won more world championship grands prix than any other driver never to have secured the championship, despite the ever-escalating number of such races. He has always maintained that he’d like to remembered as “a driver who preferred to lose while driving quickly than to win by driving slowly enough to get beaten”. For a few years, after the retirement of the great Juan Manuel Fangio in 1958, he was the finest and most famous racing driver in the world. He was so good that Ferrari not only wanted him to drive for them but were prepared to have the car painted blue, the team colour of his friend Rob Walker. And it is worth remembering that Enzo Ferrari rated Moss ahead of Fangio and placed him alongside Tazio Nuvolari. He is, perhaps then, the ultimate proof that raw racing statistics sometimes mean very little when you are natural racer.

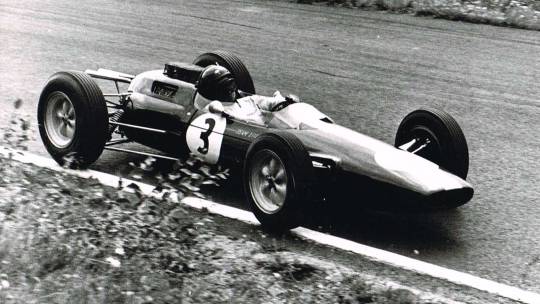

Jim Clark’s raw racing statistics spoke volumes for his achievement and the astonishing records he set, a few of which still remain unsurpassed. More than that he has been hailed as one of the top three drivers of all time in any reputable survey. His achievements were a reflection of the awe and admiration many of his driving peers and others since his untimely tragic death have held about the man and the racer.

Clark began matching Stirling Moss’s speed in the second half of the 1961 season, and took over the Englishman’s mantle in 1962 when Moss was injured in a crash at Goodwood on Easter Monday. Clark narrowly lost the World Championship that year to BRM rival Graham Hill, after his Lotus developed an oil leak while dominating the finale in South Africa. Two years later he lost another championship to an oil leak, literally on the last lap of the season-closing Mexican GP. The honours fell instead to John Surtees. But in 1963 and 1965 Clark was unstoppable in Colin Chapman’s green and yellow Lotuses, and their driver/engineer relationship was symbiotic.

Jim Clark not only won his second title in 1965 but he did so by leading every single lap of every race he finished in the 1965 season. Therefore, he won every race he finished with what we now call lights to flag victories. It was an incredible feat which has been unmatched by the other truly greats of the sport, Fangio, Senna, or Schumacher.

In 1963 only some obfuscation by the establishment at Indianapolis Motor Speedway in favour of the traditional front-engined roadsters prevented him from beating Parnelli Jones to victory on his Indy 500 debut in Chapman’s rear-engined Lotus ‘funny car’. He led the 1964 Indy 500 race before his rear suspension broke, and in 1965 dominated the event and became the first Briton to win this iconic race since Dario Resta in 1916.

Clark remains the only man in history to have won the Formula One World Championship and the famed Indianapolis 500 in the same year (1965).

His tally of 25 victories was a record at the time. It has since been surpassed by several other drivers, but none in so few races. Clark's came in just 72 starts, a win ratio surpassed only by Alberto Ascari and Juan Manuel Fangio.

Likewise, his tally of 33 total pole positions was first passed by Sebsatian Vettel, with only Ayrton Senna, Michael Schumacher and Lewis Hamilton ahead of Clark. But in percentage terms, Clark is ahead of them all. He was on pole for 45.2% of his races - only Fangio, on 55.8%, did better.

Those numbers give a sense of how Clark towered over his era, a period when he made many grands prix mind-numbingly boring, so completely did he and his Lotus dominate them. Yes, the Lotus was often the best car, but Clark's supremacy was not in doubt. His two titles in 1963 and 1965 were exercises in crushing superiority, and he would have won in 1964 and 1967 as well had it not been for the notoriously poor reliability of Lotus's cars.

But does any of this tell us which of the three would have won between the three of them at the British Grand Prix as you suggest?

Graham Hill may have been the monarch of Monaco - his nickname was after all ‘Mr Monaco’ with his magisterial six wins between 1963 and 1969, a record only bettered by the great Ayrton Senna - but much to his regret he never won a British Grand Prix race.

Stirling Moss won two British Grand Prix races in 1955 driving a Mercedes car and in 1957 where he shared a drive in a Vanwall car with Tony Brooks.

Jim Clark won the British Grand Prix an astonishing five times. In 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965 he won driving the same Lotus-Climax car and in 1967 he won with a Lotus-Ford car. His five victories were a record that stood through the subsequent decades until Alain Prost equalled Clark’s tally in 1993 (Prost won on and off between 1983 and 1993). Clark’s record was only surpassed in 2019 when Lewis Hamilton won his amazing sixth victory at the British Grand Prix (with perhaps more to come). Even more remarkable was how peerless Clark’s domination was as he won four British Grand Prix races consecutively. It was yet another amazing record that belonged to Jim Clark until Lewis Hamilton joined him in the record books with four straight wins (2014-2017).

It might be churlish to point out that Stirling Moss, like Graham Hill, never won at Silverstone even when he raced there. Clark won three times.

In those days the British Grand Prix was not always held at Silverstone. Between 1926 and 1986 the venue track chosen rotated between Brooklands and Silverstone, then Aintree and Silverstone, and later Brands Hatch and Silverstone. Only from 1987 onwards to the present day did Silverstone become the established venue race track of the British Grand Prix.

Moss’ two British Grand Prix victories were both achieved at Aintree (1955 and 1957). The British Grand Prix races that Moss did compete at Silverstone he retired due to engine or axle trouble.

In contrast Clark won his first British Grand Prix victory at Aintree in 1962, and another one at Brands Hatch in 1964 but the other three victories were at Silverstone.

So one would have to give the win to Jim Clark on paper.

But some may argue yes, that’s all well and good but who was the fastest driver and who really was the better driver?

Here again the stats speak for themselves. The all time list of fastest laps set during their respective careers gives us some clue because the tracks they drove on were the same during their eras. Graham Hill is 34th on the all time fastest laps set with 10 fastest laps in the Grand Prix races he drove in a 17 year career (1958-1975). Stirling Moss is 15th on the all time fastest - one position above Ayrton Senna - where he set the fastest laps in 19 Grand Prix races in his 10 year career (1951-1961). Jim Clark is 7th on the all time fastest laps set by a Grand Prix driver. He recorded 28 fastest laps in Grand Prix races in his 8 year short racing career (1960-1968). Only Mansell, Vettel, Prost, Raikkonen, Hamilton and Schumacher as 1st stand ahead of him. What makes Clark’s achievement staggering is that he was competing in an era where technology was in the Bronze Age compared to the modern marvels of technology, aerodynamics, and speed. It’s also worth noting all the other drivers had much longer racing careers than Clark did before his untimely death. At the 1968 South African Grand Prix - his last before his death in Hockenheim ring in Germany 3 months later - Clark won way ahead of the pack led by Graham Hill who came in second. He was comfortably on his way to another world championship with more records to be smashed.

Clark still holds the record of eight Grand Slam race wins - that is winning pole position, putting in the fastest lap, and leading every lap of a race to the win. Only Lewis Hamilton comes close with six and Schumacher and Ascari with five. He achieved this twice at the British Grand Prix in 1962 (Aintree) and 1964 (Brands Hatch). Again it needs to be emphasised that Clark did all this while driving in the most dangerous era of Formula One - The Killer Years - where death of drivers and lack of driver and track safety was all too common. This is simply astonishing.

Of the three, Jim Clark was the fastest. I think this isn’t just about stats it’s also the they way they drove that made all three such great racers. All three certainly had limitless courage that even now demands total respect and awe. In particular it’s breath taking watching old film footage of Moss driving his most famous and greatest victory of all was the 1955 Mille Miglia in which he covered 1,000 miles of open Italian roads at an average speed of 97.96mph in 10 hours, seven minutes and 48 seconds.

But the fastest doesn’t make you best of course. When it comes to judging who was the best I think what their peers and contemporaries thought of them counts a lot in coming to some conclusions as to who was the best driver.

Sir Jackie Stewart, three times world champion and a team mate of Jim Clark as well as friends with all three drivers, is worth listening to.

Many think that Graham Hill wasn’t the most natural driver. This isn’t said to slight him or doubt his abilities but to acknowledge his approach to driving. As Jackie Stewart said, “Whereas Jimmy [Clark], Stirling, to a certain extent myself, would drive around a car’s handling problem, Graham would fiddle with the car until it was right. Graham would take very different lines around a corner to others, and I know because sometimes I was following him.”

Sir Stirling Moss has echoed Stewart’s comments. “I’d go along with Jackie and say that Graham didn’t have a natural ability to drive a car extremely quickly. But having said that, when I was to choose a partner for a sports car race at say, the Nürburgring, I would always choose Graham because he was so reliable. Quick, but unlikely to do anything stupid.”

Jackie Stewart’s comment unearth one of secrets of why not only was Jim Clark the fastest but also the best of the three. Simply put Clark knew how to take corners and know when to brake.

It must be stressed that both Moss and Clark knew how to take corners and mastered the art of breaking to a level very few drivers reached whatever car they were driving.

Moss was certainly a pioneer in taking corners and knowing when and when not to brake. Moss - especially at his peak in the Lotus - would cut into the corner early and with the brakes on.

Most drivers run deep into a corner before turning the wheel. In this way a driver could complete his braking in a straight line, as is the standard practice and one everyone did and still do, before setting the car up for the corner. But natural drivers like Moss (and Clark) preferred to cut into the corner early and even with their brakes still on to set up the car earlier. In this way such drivers almost make a false apex because they get the power on early and try to drift the car through the true apex and continue with this sliding until they are set up for the next bit of straight. In other words, the result is a smooth line as you come out of the turn and race on at faster and more seamless speed.

Clark would take this to the next evolutionary step from Moss - also in a Lotus - as cars became more mechanically challenging to handle. Clark placed a big premium on braking. In his book At the Wheel (1964) he expounded on this belief, "The most important thing you can learn in racing: how to brake. Often, if I want to go through a given corner quicker I don’t necessarily put the brakes on any later than usual, but I might not put them on very hard, and take them off earlier. Where you are led into the trap is leaving your braking too late and having to run deep into the corner and brake at the last moment, you might certainly arrive at the corner quicker, but there is a psychological tendency to brake much harder than you need to and therefore over-brake."

A good example of this is looking at footage of the 1965 French Grand Prix in Clermont-Ferrand where Jim Clark won from pole position and set the fastest lap around this new track that no one had driven on before (see below)

youtube

Fast forward to the 9 minute mark you will see all the top drivers of that era tackling a fast downhill left - unfortunately you don’t see Graham Hill, who had an off day and ended up 13th I think - but the point remains valid.

Jim Clark drives a Lotus in this 1965 French Grand Prix race and is bombing away from the rest of the pack as was his usual MO. The interesting thing to notice is the turn. Clark’s Lotus is 2-3 feet inside the painted white line as he turns into the corner. It’s really more of a smooth elegant sweep into the corner. Clark clearly turns in much more earlier with the brakes - as we now know - are lightly caressed. Clark smoothly glides through out of the turn as he disappears from view carrying crucial extra speed. Then the rest come and the difference is soon clear. Jackie Stewart’s BRM P261 car grazes the line and grappling with more understeer than he might have liked finds himself to the right of the dotted line when he comes out of the turn. The V8 Ferrari of the great John Surtees also grazes the line with a similar result. Dan Gurney’s Brabham BT11 car crosses the painted line and he pays for his aggressive stance by sitting cross the road’s dotted centre line. On this track at Clermont-Ferrand there were forty-eight corners in its five sinuous miles to perilously navigate and Clark using this MO had the nonchalant confidence and consistency as well as the driving artistry to increasingly pull ahead of the chasing pack to victory.

Analysing the Clark technique, Peter Collins (a former team manager at Team Lotus and Williams, and an avid Clark fan), who knows more about what makes great drivers than most, made a key observation, “His driving was incredibly fluid even in dramatic moments. Watching the first laps of various races you got a very strong impression that he was mentally more ahead of the car than was the opposition. Watching him leading at the ’Ring in 1967, for instance, the impressive thing was that there were no dead moments in transition from braking to turn-in, to throttle on. He was able to drive an understeering car in a four-wheel drift and judge the exits to perfection.”

Graham Hill, who was a good friend of Jim Clark’s as well as being a fiercely competitive rival on the track, knew better than most and so I shall let him have the final say on this. Hill in his penned eulogy to Jim Clark noted his mastery of taking the corner, “For a driver, the excitement of racing is controlling the car within very fine limits. It's a great big balancing act, motor racing. It's having the car broken away and drifting and doing exactly as you want it to do and getting around the corner as quickly as you can, and knowing that you've done it, and hoping that it is better than anyone else has done. You are aiming at perfection and never actually getting it. Now and then you say, "That's it. That's how I want to do that corner. Now beat that, you bastards." This is the essence of racing, and at this, Jimmy, in his era, was unsurpassed.”

A word must be said about the cars these drivers drove. Racing cars in that era were extremely fast but also extremely unreliable. One can only lament how many world championships Moss, Hill, and Clark would have won if not for some mechanical car failure that did cost them dearly. In the case of Clark, he agonisingly lost the world championships in 1962 and 1964 due to oil leaks in the final race both times.

Of the three Hill was the most technical, not surprising given that he started life with the Royal Navy as a technician specialist. When he was racing Hill took notes of every test, every practice, every race and how his car handled specific track conditions and setups. He was constantly on top of his mechanics with these early versions of telemetry and his expertise on engineering meant that the difference between mechanic and driver was nothing more than a grey area. According to some of the mechanics who worked with Hill, it was sometimes impossible to please him. Both Moss and Clark by contrast didn’t really bother with that side but rather they just jumped into the car and worked around the problems on the track relying on their natural flair and genius. That’s how brilliant they both were.

So how would Moss and Clark fare if they both had the same car and barring any technical issues. There are no certainties but they did both briefly overlap in their careers, as Moss was coming to the end of his and Clark was about to start his ascension. The race that most would point to is the 1961 South African Grand Prix. Stirling Moss was the undisputed world's best in 1961, pulling off some famous victories in inferior equipment, but Clark's performances at the end of the season showed that things were changing. Clark's Lotus Climax 21 car had beaten the slightly older Lotus Climax 18/21 model of Moss in the Natal Grand Prix earlier in the month, but the East London race stepped things up a notch. Clark was fastest in qualifying and started on pole position with Moss +0.2 seconds behind.

Both Clark and his Team Lotus team mate Trevor Taylor led the way at the start but but Moss was soon into second and took the lead when Clark spun avoiding another car. Now Clark charged, despite sustaining gearbox damage, lapping faster than his pole time, and Moss was powerless to stop him coming through to win."Moss pulled in behind Clark and tried to stay in his slipstream but could not keep up with Clark's fast and furious driving and fell slowly, but surely, behind," read Autosport's report. "Clark demonstrated that the world championship is no pipe-dream for him." Clark was a little more circumspect, though beating Moss was clearly a watershed: "I had the satisfaction of beating Stirling twice in two weeks, although, in all fairness, my car was newer than his," he wrote in his 1964 book, Jim Clark - At the wheel.

That Clark was being characteristically modest and magnanimous isn’t the main point to take away. The point is made by Colin Chapman the iconic genius behind Lotus who said of Clark, “when there was no mechanical trouble, Clark absolutely blew away the opposition. One prime example of that was the 1967 German Grand Prix when the Lotus was not an easy car to drive but still Clark got pole in it by a staggering 9 seconds. This also brought out another of Clark’s skills – to drive around problems. He was capable of driving a car with any given setup – he never asked to change the setup to make it to his liking, he went out on track and tried to make the car go faster by adjusting accordingly at corners, which was very easy for him as he had a very smooth driving style and it never looked like he was trying to muscle the car across the corners.”

Once Clark was in front he was almost unbeatable. No matter who you were or how good you were, Clark was quicker and relentless. It was almost game over once Clark took the lead and slowly pulled away from the rest. Graham Hill said in his eulogy to Jim Clark, “He was also particularly competitive, particularly aggressive, but he combined this with an extremely good sense of what not to do. One can be overthrusting—aggressive to the point of being dangerous. Well, this Jimmy was not. But he was a fighter, a fighter that you could never shake off. He invariably shot into the lead and killed off the others, building up a lead that sapped their will to win.”

This is one main reason with all things being equal, Clark would beat Moss and Moss would beat Hill. The really scary thing about Clark’s complete mastery of driving was what Colin Chapman said years later, "I think Jim never drove really 100% - he was so good, he didn’t need it to beat the others. Perhaps only in Monza 1967 he had the knife between his teeth...."

Moss is rightly celebrated as an icon of motor racing. Moss had a fantastic 15 year career on the track and just as importantly he had an even longer one off the track as the fantastic ambassador of Grand Prix racing. Moss lived to be 90 years old and he used that time to deservedly cement his legendary status as a Formula One great. He was a very charismatic and convivial personality. He is revered by contemporary drivers and racing fans because his presence was anywhere and everywhere. No racing event would be complete without the vintage stardust of the great Sir Stirling Moss. At Goodwood and at the RAC Club racing enthusiasts would mill around him and listen to his endless yarns. At race circuits during the Grand Prix season his presence in paddock would stop everything as racers and technical crew were in awe of him.

In contrast Jim Clark’s racing career was tragically cut short to a mere 8 years and yet he had achieved so much at the age of 32 years old. Arguably his death had the greater impact because it was more keenly felt by his peers and those within the racing world. So when he was killed by a puncture during the wet Formula 2 Deutschland Trophy race at Hockenheim on 7 April 1968, after his Lotus crashed into unforgiving trees by the side of the track, race drivers around the world felt death’s hand on their shoulder, and asked themselves, “If it can happen to Jim Clark, what chance do we have?”

The consequence of Clark’s death cannot be stressed enough. Clark’s death was the sacrificial blood price for the more modern era drivers to race with greater driver safety measures in place and safer tracks for spectators that these days we today take for granted. A lot of credit is due to Clark’s close friend and team mate, the great Sir Jackie Stewart, who at the risk of his own personal reputation, pushed hard for the racing world to take driver safety seriously. A lot of danger - and perhaps even the excitement - has been taken out as Moss used to say. But there is no question racing - whilst still relatively dangerous because of the higher speeds they are pushing for those micro margin of victories - is much safer than the dangerous era of Moss, Hill, and Clark.

So why isn’t he more well known or revered by the general public (as opposed to hard core racing fans and those within the racing world)? I suspect it was due to his shyness and aversion to publicity. Clark grew up on a Scottish farm and he was clear to many that this was his roots that he always returned to. While he couldn’t entirely avoid the glamour of the racing world with its hedonistic side effects of women, sex and fast cars - as personified by Graham Hill or James Hunt - Clark eschewed all that in favour of simple living on his Scottish farm. His only indulgence was an airplane that he used to piloted into race circuits in Europe - Hill could fly too and it cost him his life in 1975 in a tragic plane accident. Clark simply loved racing. The proud Scot was a gentleman with self-deprecating charm and modesty to match. He was simply a good and decent man revered by his own peers in his own time.

At Clark’s funeral, Jim Clark Snr, beloved father, confessed to Dan Gurney, a racing rival, that he was the only man his son had feared. Gurney, who died in January 2018, spoke of Clark thus: “It is certainly an honour to have had the opportunity to know him as a team-mate, a friend, and to have competed with him on so many memorable occasions. Jim whipped us so many times that we all sort of got used to it. Naturally, we didn’t like being whipped, but, it is probably a testimony to Jim’s integrity and stature among us, his peers, that we couldn’t help loving the lad in spite of it.”

Elizabeth ‘Widdy’ Cameron, whom Clark nearly married in 1960, and with whom he stayed close despite rising fame, said: “He was very shy. And he was a terrific gentleman. I didn't hear him say bad things about anybody. He was a good, good man and I hope everybody remembers that. He was very special.” Sir Jackie Stewart, the three time world champion and another great British driver, still sheds a tear when he’s asked about Jim Clark. The two Scots were close friends, and three years earlier when Stewart had arrived in F1, he played the Robin role to Clark’s undisputed Batman. “Jim Clark,” he says still, “was everything I aspired to be, as a racing driver and as a man.” When Jim Clark this humble man as a product of his upbringing on a Scottish farm in the Scottish Borders insisted that inscribed on his tomb stone would be, ‘farmer and world champion’.

Of course I never saw Moss, Hill and Clark race but I’m definitely in the camp that considers Jim Clark as not only the greatest British driver of all time but also arguably the best driver in the world of all time alongside that other most naturally gifted racer, Ayrton Senna. There’s not much to differentiate their greatness and genius.

It’s fitting that the final judgement of who was the best driver of the three should rest with their peers and contemporaries. Juan Manuel Fangio, the Argentine great is one of my favourite racers and one who is also considered one of the greatest of all time, said this about Clark in 1995: "He was better than I was - the greatest driver ever." Even the great Ayrton Senna when he went to Clark’s old Scottish boarding school, Loretto, confessed to the schoolboys, "After all - Jim Clark was the greatest driver ever."

The wonderful thing about arguing about who is the best with British icons like Moss, Hill, and Clark as examples is how the past can inspire the present generation of drivers to aspire to greater heights than the peers of the past. Who knows perhaps one day we will be talking about Lewis Hamilton or Max Verstappen in the same hushed tones of reverence and awe. Then as racing fans we should count our blessings that we can witness their special racing artistry on the track first hand while we can in the same way past generations were in awe of such special talents as Moss, Hill, and Clark.

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#grand prix#racing#driving#stirling moss#jim clark#graham hill#formula one#britain#british#sports

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ciao Niki

Ferrari pays tribute to the Austrian champion

A workaholic, a computer-like brain ahead of his time, a stickler for detail who could separate emotion and rational thought and go straight to the heart of the matter. But at the same time, a person who could have moments of madness, who, to take the title of his autobiography, went on a journey “to hell and back.” A man who found the strength to jump back in his racing car just six weeks on from that terrible accident which he miraculously survived. These were just some of the elements that made up Andreas Nikolaus Lauda, known to everyone simply as Niki. Last night, at the age of seventy, he passed away.

“This is a very sad day for me, having been fortunate to have actually seen him race and also for all fans of Ferrari and Formula 1,” commented Ferrari Vice President, Piero Ferrari. “Niki leaves us having suffered so much and that is painful for me. He won so much with Ferrari and with other teams too and he always remained a friend. He was a fantastic driver, an accomplished businessman and an amazing person. I will miss him.”

“My memories of Lauda go back to my childhood,” recalled Scuderia Team Principal Mattia Binotto. “When I was little I saw him and Regazzoni win for the Prancing Horse on race tracks all round the world. I was not yet ten and to me he seemed like a fearless knight. Once I came into Formula 1, my relationship with Niki was one of mutual respect. I think that thanks to his bravura and his undoubted charisma, he helped make this great sport well known and loved all over the world. I have fond memories of him telling me that my Swiss approach was just what was needed to bring order to the very Italian Ferrari! That was Niki all over, straight talking and direct and even if you didn’t agree with him all the time, you couldn’t help but like him.”

Lauda was born in Vienna on 22 February 1949. He was an innovator and a champion who brought a new way of thinking to his racing. When Niki first appeared on the Formula 1 scene, he came across as a stubborn young man, with strong self-belief, to the extent that he ignored the wishes of his family and took out a loan to follow his dream to race in Formula 1. In 1973, the Austrian drove for BRM alongside Clay Regazzoni and it was the Swiss driver who mentioned the youngster to Enzo Ferrari. In one of those typical moves that caught out everyone in the sport, Ferrari signed Lauda for 1974. Right from the start, at the races in Spain and Holland, Niki was a front-runner, fighting for the wins in the 312 B3-74. He missed out on the title, but in 1975 he would drive the 312 T. Lauda was fully immersed in the team, helping it to improve with his mania for detail and his attitude endeared him to Enzo Ferrari, who treated him like one of his family. Lauda and the Scuderia evolved into the perfect partnership and grit and determination brought win after win. In 1975, the Austrian took his first world championship crown, also helping the Prancing Horse to win the Constructors’ and Drivers’ titles for the first time after an eleven year wait.

The 1976 season got off to an encouraging start for the reigning champion. Niki won five of the first nine races – Brazil, South Africa, Belgium, Monaco, Great Britain – so that he had more than double the number of points of his closest rival. Then it was time for the German GP at the Nurburgring, the circuit known as the Green Hell, because it was so long, tricky and dangerous. On lap 2, Niki lost control of the car on the damp track and crashed heavily into the barriers. As a result, the car burst into flames. Thanks to the valiant efforts of other drivers, he was pulled from the wreckage, but he was seriously injured, to the extent he was given the last rites. But Lauda was not the sort to give up easily. He fought just as hard in his hospital bed as he had done on track and recovered in record time. Just six weeks later, he was racing again, although in great pain. He was determined to retain his title, but it was not to be. He missed out on the championship by a single point under a downpour at Fuji in Japan. Events had turned Lauda into a true hero, in sport and in life. His popularity transcended the world of racing as he entered the collective imagination, to the extent that his life was even turned into a film.

In 1977, Lauda won his second world championship, but it was also the year in which he severed his ties with the Scuderia and Enzo Ferrari. Lauda switched to Brabham for the following year but, on their own, neither he nor Ferrari managed to win. Niki briefly retired from the sport, before returning to take his third and final title in 1984, with McLaren.

Despite a turbulent end to the relationship with Scuderia Ferrari, the story of Lauda and Maranello would have a final chapter, when he returned as a consultant to the team in 1993. With his two titles and 15 wins over four seasons, Lauda is the second most successful driver for Scuderia Ferrari in Formula 1.

233 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Niki Lauda - GP Monaco 1975 - Ferrari 312 T

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Monaco GP 1975 -- Princess Grace and Prince Rainier with the winner Niki Lauda.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Niki Lauda remembered: All 25 of his F1 wins

Niki Lauda remembered: All 25 of his F1 wins

1974 Spanish GP

1/25

Photo by: Sutton Images

1974 Dutch GP

2/25

Photo by: LAT Images

1975 Monaco GP

3/25

Photo by: LAT Images

1975 Belgian GP

4/25

Photo by: Rainer W. Schlegelmilch

1975 Swedish GP

5/25

Photo by: Rainer W. Schlegelmilch

1975 French GP

6/25

Photo by: LAT Images

1975 US GP

7/25

Photo by: Ercole Colombo

1976 Brazilian GP

8/25

P…

View On WordPress

0 notes