#mitzraim

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

youtube

10 Pragas do Egito

1 note

·

View note

Text

Me when im agitato grande, muy discutante, muy disupuente and muy nauseatus, mitzraim hotzionno dayenu even...

#shitposting#musicals#falsettos#falsettoland#mendel weisenbachfeld#falsettoland obc#everyone hates his parents

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Plutarco Elías Calles fue miembro del Rito de Memphis Mitzraim

0 notes

Text

A link to my personal reading of the Scriptures

for the 25th of march 2025 with a paired chapter from each Testament (the First & the New Covenant) of the Bible

[The Letter of 1st Thessalonians, Chapter 2 • The Book of 2nd Chronicles, Chapter 21]

along with Today’s reading from the ancient books of Proverbs and Psalms with Proverbs 25 and Psalm 25 coinciding with the day of the month, accompanied by Psalm 6 for the 6th day of Astronomical Spring, and Psalm 84 for day 84 of the year (with the consummate book of 150 Psalms in its 1st revolution this year)

A post by John Parsons:

This week we will conclude the book of Exodus for the current Jewish year, and therefore I thought it was a good idea to review some of the key ideas of the book in preparation for Passover this year...

The theme of the Book of Exodus (סֶפֶר שְׁמוֹת) essentially turns on two great events, namely, the deliverance of the Israelites from bondage in Egypt (i.e., yetzi’at Mitzraim: יְצִיאַת מִצְרַיִם) and the subsequent revelation given at Sinai (i.e., mattan Torah: מַתַן תּוֹרָה). Both of these events, however, are grounded in the deeper theme of God’s faithful love (chesed ne’eman: חֶסֶד נֶאֱמָן) expressed by the blessing of blood atonement (i.e., kapparat ha’dam: כָּפָרָת הַדָּם). With regard to the former, the blood of lamb (as foreshadowed in Eden) was required to cause death to “pass over” (לִפְסוֹחַ) the houses of the faithful of Israel; with regard to the latter, the sacrificial system represented by the Mishkan (i.e., “Tabernacle”) was designed to teach what I call the “korban principle” (i.e., ikaron ha’keravah: עִקָרוֹן הַקרָבָה), that is, that the only way to draw near to God is by means of sacrificial blood offered in exchange for (or in place of) the trusting sinner, as stated in the Torah, “For the life of the flesh is in the blood, and I have given it for you on the altar to make atonement for your souls, for it is the blood that makes atonement by the life” (Lev. 17:11), and likewise in the New Testament we read: “without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins” (Heb. 9:22).

Jewish tradition tends to regard the giving of the law at Sinai to be the goal of the entire redemptive process, a sort of “return from Exile” to the full stature of God’s chosen people. Some of the sages have taken this a step further by saying that God created the very universe so that Israel would accept the law. Such traditions, it should be understood, derive more from rabbinical thinking devised after the destruction of the Second Temple than from the narrative presented in the written Torah itself, since is clear that the climax of the revelation at Sinai was to impart the pattern of the Mishkan (תבנית המשכן) to Moses. In other words, the goal of revelation was not primarily to impart a set of moral or social laws, but rather to accommodate the Divine Presence in the midst of the people. This is not to suggest that the various laws and decrees given to Israel were unimportant, of course, since they reflect the holy character and moral will of God. Nonetheless, it is without question that the Torah was revealed concurrently with the revelation of the Sanctuary itself, and the two cannot be separated apart from “special pleading” and the suppression of the revelation given in the Torah itself... The meticulous account of the Mishkan is given twice in the Torah to emphasize its importance to God. This further explains why Leviticus is the central book of the Torah of Moses. (For more on this, see “The Eight Aliyot of Moses.”)

As we consider these things, however, it is important to realize that underlying the events surrounding deliverance and revelation is something even more fundamental, namely, the great theme of faith (אֱמוּנָה). This theme is our response to God’s redemptive love. God’s love is the question, and our response - our teshuvah - is the answer. The great command is always to "choose life!" We must chose to turn away from the darkness to behold the Light... Jewish tradition states there were many Jews who perished in Egypt during the Plague of Darkness because they refused to believe in God’s love. Likewise, the revelation at Sinai failed to transform the hearts of many Jews because they despaired of finding hope.

As glorious as the redemption and revelation was, then, there was something even more foundational that gave “inward life” to God’s gracious intervention. You must first believe that God loves you and regards you as worthy of His love; you must “accept that you are accepted.” It is your faith that brings you near... This is the “Cinderella Story” of Exodus.

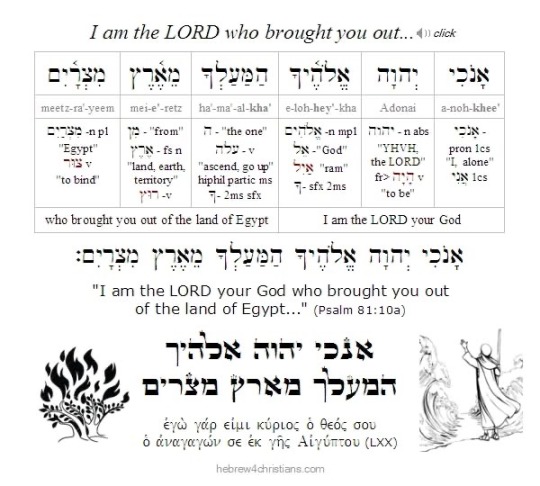

These themes of the Book of Exodus - and really of the Bible itself - will mean little to you unless you willingly identify with the calling of the Jewish people, and that implies that you reckon yourself as worth saving... You must see yourself as the recipient of divine affection and love. After all, without this as a first step, how will you make the rest of the journey? This is similar to the First Commandment revealed at Sinai: “I AM the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt...” Notice that the statement, "I AM the LORD your God" (אנכי יהוה אלהיך) was uttered in the second person singular, rather than in the plural. In other words, you (personally) must be willing to accept the love of the LORD into your heart, since the rest of the Torah is merely commentary to this step of faith. Therefore the Book of Exodus is called Shemot (שְׁמוֹת), "names," because it sees every person as worthy of God’s redeeming love and revelation. “For God so loved the world...” (John 3:16).

The midrash says that only one out of five of the children of Israel made it out of Egypt; some say one out of fifty, and some say one out of five hundred (see Mechilta). As Yeshua said: "Many are called, but few are chosen" (Matt. 22:14). Those who directly experienced God’s deliverance in Egypt first of all believed they were redeemable people. Before anything else they made a decision to receive hope within their hearts. The blood of the original Passover lamb was a smeared as sign of their faith that God would accept them. We also must begin here. This is the start of the journey. We step out by faith, leaving behind the familiar - including the dark familiarity of our sin and shame - and venture out into the unknown. We venture out in hope because we trust the promises of God (הַבְטָחוֹת יהוה).

The journey of faith (מַסָע הַאֱמוּנָה) is marked with testing (בְּדִיקַת אֱמוּנָה). Being called out of the world leads you into the desert places. Faith is not something static, like a church creed or theology handbook. There are stony places, dangers, and difficulties that attend the way. We move out from “walled cities” into tents, traveling as “strangers and sojourners” on our way to a promised heavenly city. Therefore the Scriptures state that "by faith Abraham went to live in the land of promise, as in a foreign land, living in tents with Isaac and Jacob, heirs with him of the same promise. For he was looking forward to the city that has foundations, whose designer and builder is God" (Heb. 11:9-10). The way back home is the same for all who "cross over" from this world to the next. It is the way of hope, trust, and surrender.

The story of divine deliverance is not the story of “other people”; it is not a story told in the “third person.” You must choose to belong. Again, your faith draws you near. That is why the sages teach: b'chol dor vador - in each and every generation an individual should look upon him or herself as if he or she (personally) had left Egypt. It's not enough to recall, in some abstract sense, the deliverance of the Jewish people in ancient Egypt, but each Jew is responsible to personally view Passover as a time to commemorate their own personal deliverance from the bondage of Pharaoh. The same must be said regarding Shavuot. Each person should consider himself as having personally received revelation at Sinai. The altar of the Mishkan was set up for you to draw near to God - you, not some people who lived long ago... This is why non-Jews who turn to the God of Israel by putting their trust in the Messiah are regarded equal members in the covenants and promises given to ethnic Israel. It is a brit milah (בְּרִית מִילָה) - literally, a "covenant of the word" - that makes us partakers of the covenantal blessings given to Abraham (Eph. 2:12-19; Gal. 3:7; Col. 2:11, etc.).

The narratives of the Book of Exodus, like other narratives of the Torah, often function as parables of faith (i.e., mishlei emunah: מִשְׁלֵי אֱמוּנָה). "The deeds of the fathers are signs for the children." Signs of what? Of the coming Messiah, as Yeshua Himself attested and the apostles likewise affirmed (John 5:46; Luke 24:27;44; Matt. 13:52; 2 Tim. 3:14-17). The Mishkan (i.e., “Tabernacle”) itself was a metaphor of God’s redemption (גְּאוּלַת יהוה) embodied in Yeshua. The Mercy Seat (kapporet) represented the Throne of God (Heb. 4:16; 2 Ki. 19:15) where propitiation for our sins was made (Rom. 3:25). Indeed, the word Mishkan (מִשְׁכָּן) is related to the word mashkon (מַשׁכּוֹן), a pledge or “promise on loan.” The Tabernacle functioned as a “loan” to Israel until the Messiah came to establish the true Temple (הַאֲמִיתִי הַמִּקְדַשׁ) by means of His atoning sacrifice (Gal. 3:19). The law (ספר הברית) is called a "schoolmaster" meant to lead to the Messiah and His Kingdom rule (Gal. 3:23-26). The glory of the Torah of Moses was destined to fade away (2 Cor. 3:3-11), just as its ritual center (i.e., the Tabernacle/Temple) was a shadow (צֵל הַמִצִיאוֹת) to be replaced by the greater priesthood of the Messiah (כְּהוּנָת הַמָּשִׁיחַ; see Heb. 10:1; 13:10). "Now we are released from the law, having died to that which held us captive, so that we serve in the new way of the Spirit (הַדֶּרֶך הַחֲדָשָׁה שֶׁל הָרוּחַ) and not in the old way of the written code (Rom. 7:6). Yeshua is the Goal of salvation (מְטָרָת הַיְשׁוּעָה) and the “Goel” (i.e., גּאֵל, Redeemer) from the curse of the law... "For the law made nothing perfect, but on the other hand, a better hope is introduced, and that is how we draw near to God" (Heb. 7:19). When the veil is taken away, Yeshua appears on every page of Scripture... (For more on this, see “Why then the Law?,” and “Paul’s Midrash of the Veil,” links below).

[ Hebrew for Christians ]

========

Isaiah 43:1b reading:

https://hebrew4christians.com/Blessings/Blessing_Cards/isa43-1b-jjp.mp3

Hebrew page:

https://hebrew4christians.com/Blessings/Blessing_Cards/isa43-1b-lesson.pdf

3.24.25 • Facebook

from Israel365

Today’s message (Days of Praise) from the Institute for Creation Research

0 notes

Text

i am muy disgutante 🫶🏽

and muy disappointe 🫶🏽

and muy naseatus 🫶🏽

and me mitzraim hotzionno dayenu 🫶🏽

jason, i am agitato grande, jason

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parashat Vaera-MeirTV Spanish en YouTube

youtube

Rabbis Meir Kalmus and Shmuel Kornblit talking about the weekly Parshah 📜🤗

#parasha de la semana#jumblr#torah#torah study#parasha ha shavua#parasha vaera#rabbis#rab. kalmus#rab. kornblit#meir tv spanish#moshe ravenu#mitzraim#amisraeljai#am israel#israelites#10 plagues#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Va'eira: "Who Brings You Forth"

HaMotzi — the Blessing for Bread

As a rule, most of the blessings recited over food speak of God as the Creator. For example, we say: בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָעֵץ (“Creator of fruits of the tree”), בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה (“Creator of fruits of the ground”), בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הַגָּפֶן (“Creator of fruits of the vine”).

But the blessing for bread does not fit this pattern. Before eating bread, we say HaMotzi — הַמּוֹצִיא לֶחֶם מִן הָאָרֶץ — “Who brings forth bread from the earth.” Why don’t we acknowledge God as “the Creator of bread,” following the formulation of other blessings?

It is highly significant that the wording of the blessing of HaMotzi mirrors the language used by God in His announcement to Moses:

Is there some connection between bread and the Exodus from Egypt?

The Special Role of Bread

The Earth contains an abundance of nutrients and elements, and through various processes, both natural and man-made, these elements are transformed into sustenance suitable for human consumption. However, when it comes to foods that are not essential to human life, it is difficult to know whether the nutrients and elements have attained their ultimate purpose upon becoming food. In fact, their utility began while they were still in the ground, and we cannot confidently state that they are now, in the form of a fruit or vegetable, more vital to the world’s functioning.

Bread, on the other hand, is the staff of life. Bread is necessary for our physical and mental development. As the Talmud states, “A child does not know how to call ‘Father’ and ‘Mother’ until he tastes grain” (Berachot 40b). This emphasizes the importance of bread in sustaining life, setting it apart from other foods. The elements used to make bread have attained a significant role that they lacked when they were still buried inside the earth.

The words of HaMotzi blessing — “Who brings forth bread from the earth” — reflect this aspect of bread. The act of “bringing out” draws our attention to two stages: the elements’ preliminary state in the ground, and their final state as bread, suitable for sustaining humanity. Other blessings focus on the original creation of fruits and vegetables. HaMotzi, on the other hand, stresses the value these elements have acquired by leaving the earth and becoming life-sustaining bread.

What does this have to do with the Exodus from Egypt?

The elements that are used to make bread started as part of the overall environment — the Earth — and were then separated for their special function. So, too, the Jewish people started out as part of humanity. Their unique character and holiness were revealed when God took them out of Egypt. “I am the Eternal your God, Who brings you forth from under the subjugation of the Egyptians.”

Like the blessing over bread, God’s declaration highlights two contrasting qualities: the interconnectedness of the Jewish people to the rest of the world; and their separation from it, for the sake of their unique mission.

(Adapted from Olat Re’iyah vol. II, p. 286)

0 notes

Text

I think it's:

Ma tovu ohalayikh Leah mishkenotayikh Rachel.

Despite the plural of 'mishkan' (dwelling place, residence) being 'mishkanot,' when you attach the possessive suffix we want to the plural noun, the 'a' becomes an 'e.' For Yaakov, we want to attach '-ekha' for the masculine singular addressee + plural noun, so it's 'mishkenotekha.' "Your dwellings" for a single male addressee. For Rachel, we use the suffix '-ayikh' for the feminine singular with our plural noun, giving us 'mishkenotayikh.' Similar considerations for 'ohel' (tent), but vowel magic happens and the 'e' in the word becomes an 'a' for the form we want.

If you want to know why mishkanot changes to mishkenot, it's because the noun is in something called a construct state and vowel changes tend to happen. It's why we take 'bayit' (house) and turn it into 'beit' for words like 'beit din' (court) and 'beit kholim' (hospital.) Literally those words break down into "house of law" and "house of the sick" respectively, but 'bait' has to be transformed into the construct form 'beit' to give you this possessive meaning. Another one you'll see is 'elohim' become 'elohei' in something like 'elohei mitzraim' for 'the gods of Egypt' or 'elohei Avraham' for 'the God of Avraham.' Some words don't change though-- in singular form, 'yam' (sea, ocean) is still 'yam,' like 'yam hamelakh' ("the sea of salt") for the Dead Sea.

Ma Tovu with Leah & Rachel?

Last month we sang “Ma tovu” at the synagogue in a slightly different form than usually. The traditional text is:

Ma tovu ohalekha Yaakov Mishknotekha Yisrael

When we sang this text as the chorus we repeated it and changed “Yaakov” to “Leah” and “Yisrael” to “Rachel”. The words “ohalekha“ and “mishknotekha“ were adjusted to fit the female form. I don’t remember how the female version differs from the male. Can anybody help me woth this, please? Thank you!

#I'm using your spelling convention of *kh* for *ch* btw#Maybe I shouldn't have used elohim as an example since grammatically it's actually plural but we mean it in the singular#unless context makes it obvious that you do really mean the plural

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the DnD Jumblr ask: Yaakob, Moishe, and Miriam!

Yaakov:

I think he'd be a Rogue. This is the man who tricked his brother to get his Birthright, and tricked his father to get the Blessings, tricked Lavan to get his rightful dowry, and fought a literal angel. This man is not afraid to resort to trickery and deception for what he thinks is right. At times he's morally grey because of this, but ultimately his actions pay off in the end. He's a tactition, he carefully divided his household when preparing to battle Esav, and he's a diplomat. This is a jack-of-all-trades and a genius.

For his alignment, he'd be Chaotic Good. He's good, but boy is he just an unbridled source of chaos.

Moshe:

He'd be a Paladin. He's obviously one of the greatest leaders of our time, and he's both a clan leader and a fighter. He speaks to G-d and argues with G-d, and fights Mitzraim, Amalek, the men at the well, and anyone who dares threaten his people. He's imbued with prophecy and connection to G-d, although sometimes he makes grievous mistakes.

For his alignment, he'd be Neutral Good. I was going to say "lawful good", but since when has Moshe ever followed the letter of the law? He's absolutely good, but sometimes he makes mistakes, and even talks back to G-d. (I think we're seeing a theme here with Tanakh figures and talking back to G-d XD).

Miriam:

Kind of obvious, but she'd be a Bard. She's associated with music, after all she helped compose Shirat HaYam, and led the Jews in song and praise after the splitting of the sea. The timbrels she and the women had were taken from their Egyptian masters when they were preparing to leave Egypt, and I think that's pretty badass. It's in her merit that the Jews had water in the desert, and she's smart and headstrong. She was the one who suggested to Batya to make Yocheved Moshe's wetnurse, and if we go by Midrash, she was also one of the midwives who defied Pharoah's orders and saved the Jewish babies. She also rebuked her father and all the Jewish men for divorcing their wives out of fear of the Egyptians, and she's confident and wise.

Her alignment would be Chaotic Good. She's good, but like her ancestors, she's absolutely chaotic. She's rebellious and witty and isn't afraid to speak her mind, even against voices of authority. She definately makes mistakes, like when she slandered Moshe's wife, but she's very much human. She's an awesome figure.

#jumblr#judaism#miriam#miriam haneviah#moshe#moshe rabbeinu#yaakov#yaakov avinu#tanakh#midrash#jumblr ask meme#if jew know jew know

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luz negra.

Esta escrito Zohar Bereshit 15a “con el comienzo de la voluntad del Rey (para crear el mundo) una luz negra (Butzina dikardinuta) suprema (una chispa fuerte) emergío”.

Para comprender este hermetico pasaje debemos saber que antes de que nuestro universo fuera creado la luz Divina lo abarcaba absolutamente todo. No habia nada fuera de El. En el momento en el que el ser supremo decidio crear su mundo, el primer paso para hacerlo fue un proceso llamado tzimtzum (contracción) es decir la contraccion de la luz Divina para asi dejar un espacio “vacio” (un lugar donde la luz no fuera perceptible) y dar asi lugar a lo otro, a lo ajeno, a la dualidad, aquello que en apariencia no es Dios, sino creación.

Nuestros sabios nos explican que esta “contracción” tiene por objetivo el dar la pauta para la existencia de una creación que no sea absorbida inmediatamente por la luz Divina. Sin embargo aun dentro de este espacio vacio la luz del Infinito continua irradiando solo que de forma oculta. En secreto.

Para lograr esto el creador utilizo una “Butzina dikardinuta” (luz “oscura”). Descrita en el parrafo de inicio.

Esta luz es nada mas y nada menos que la sensación de independencia, la subjetividad propia, en otras palabras la conciencia de uno mismo. Esta luz, fue dispuesta únicamente para que la creación pudiera observar y apreciar la luz del creador y asi ser testigos de la gran bondad Divina, pero sin ser asimilados totalmente por la unicidad del Creador. Podemos inferir de aquí que existe una dicotomia intrinseca en la creación, dicotomia que sirve de plataforma para la observacion y aprecicion de la unidad Divina, pues el ser uno incluye el hacerse uno.

Sin embargo esta sensacion de independencia, esta luz negra fue/es tan potente que causo la sensacion no solo de independencia del creador sino que es la fuente de la sensacion de desconexión absoluta, fuente entonces de la subjetividad y de la soledad existencial. Fue este resultado (la sensacion de desconexión) lo que se conoce como Shebirat Hakelim (la ruptura de los recipientes). Evento que es descrito como resultado de la incapacidad del recipiente de contener el flujo de luz divina dirigido hacia el, causando asi su fractura. Recordemos que esta luz es la llamada “luz oscura”.

Ahora bien, esta ruptura tiene consecuencias palpables hasta nuestros dias, de hecho debemos recordar que las descripciones de estos eventos son atemporales, es decir que son procesos que están sucediendo constantemente. Como dice la Guemara que “Dios renueva constantemente el Maase Bereshit”.

Por lo tanto es correcto decir que cuando somos presa de la sensacion de desconexión con lo divino dentro nuestro, estamos sintiendo la fuerza de aquella butzina (lampara) de luz negra de la que estamos hablando. Esta desconexión lleva a la fragmentación interna, a esto le llamamos oscuridad. (Al contrario de la luz negra que a pesar de ser oscura se le denomina luz).

Esta escrito en el Midrash Bereshit Raba: Cuando Hashem decretó el exilio, fue y le pregunto a Abraham Avinu, donde quieres que tus hijos cumplan mi decreto? En el Guehinom o entre las naciones? A lo que Abraham contesto, en las naciones. De aqui que “Ein Guehinom leisrael” (no hay purgatorio para israel).

Sabemos que el objetivo principal de la vida del Yehudi es “recuperar” aquellas chispas que cayeron predas de las klipot durante Shebirat Hakelim. Chispas oscuras, pues tienen su origen en la luz negra.

Sabemos tambien que estas chispas se encuentran como nos dicen los sabios en su mayoria en Egipto (Mitzraim) esta es la razon por la cual Hashem ordena a Yaakov Avinu bajar a Mitzraim (Egipto). Ya que la mayor parte de chispas se encuentran ahi. Cabe resaltar que el patriarca que termina bajando a Egipto es Yaakov el arquetipo del Yo.

Sin embargo debemos recordar lo que el Likutey Moharan nos explica. Todo sufrimiento es llamado Mitzraim pues todos los sufrimientos Mezter (oprimen) a la persona. Notese que Mitzraim (Egipto) tiene la misma raiz idiomatica que Metzer estreches/angosto/oprimir. Con esto en mente entonces podemos decir que, cuando la persona se encuentra en una situación que lo angustia esa persona se encuentra en Mitzraim, esa persona se encuentra oprimida dentro de las fronteras de ese Egipto espiritual, fronteras que como dice el Midrash eran abiertas por fuera y cerradas por dentro para que todos pudieran entrar pero nadie pudiera salir.

…Y le dijo a el Yo soy Hashem… Exodo 6:2. En referencia a este pasaje el Agra de Kala nos dice que si tomamos las letras que anteceden al tetragrama, más las letras que les siguen. Y sumamos sus valores nos da como resultado 61, el mismo valor numérico que la palabra Ani (Yo). Esto es el secreto de “Yo soy el primero y Yo soy el ultimo”. Y nos explica que estos factores numericos que rodean al nombre Divino, (nombre que representa la misericordia e infinitud absoluta) aluden a todas las aparentes condicionantes externas que dan forma a la realidad exterior del individuo, condicionantes que paradójicamente existen únicamente en este mundo dual, regido por las limitantes del tiempo y espacio. Pero son justo estos factores los que esconden las chispas divinas de luz negra, escondidas en las circunstancias que rodean la vida del individuo. Y las que en última instancia nos dan la pauta y el desequilibrio para trascender nuestra propia individualidad.

Concluimos diciendo que todo factor externo tanto bueno como malo es el escondite de estas chispas. Cada situación, cada persona que vemos, cada objeto, cada sonido tiene entonces un valor incalculable pues forman parte de los factores que envuelven el secreto de la trascendencia (Ani Hashem). Estas condiciones muchas veces angustiantes son angustiantes porque su luz es tan potente que nos desconecta de la fuente Divina y entonces me invade la sensacion de abandono existencial, de caos y de sin sentido, se vuelve todo entonces oscuridad y vacío pues siento que soy pero al ser, soy algo aparte y todo aquello que no soy yo, me resulta ajeno a mi. Y por lo tanto una amenza. La máxima expresión de la división; pero cuando comprendo que estos factores estan puestos justamente ahi y justamente en esa posicion y en esa forma para mi bien absoluto, porque están ahi para que yo pueda desarrollar (justamente) la inmanencia del yo pero con el objetivo siempre de la trascendencia hacia el otro hacia aquello que no soy yo, aquello ajeno que hoy entiendo es también Ein Sof. Entonces dejo la fragmentación interior de lado y comienzo a ser uno y forzosamente el que es uno se hace uno como dice el Zohar. Dando como resultado la integración del yo y la integración correcta de lo externo.

Cuando acepto, cuando abrazo, cuando trabajo con lo que es y lo que soy y dejo de lado lo que deseo que fuera entonces libero estas chispas, o mas bien me libero a mi mismo y me doy cuenta que eso que llame oscuridad también es luz y deja de ser oscuridad y deja de ser amargo, deja de angustiarme, aunque la forma externa de la circunstancia no cambie me libero en su forma mas absoluta (que es la libertad de la mente) de ese exilio (Galut) Egipcio. Es entonces que el Galut de la Shejina se transforma en Megale Shejina (revelacion de la presencia Divina). Y el espacio que habito y el tiempo en el que existo se vuelve sagrado. Se vuelve todo Divino todo Ein Sof y por lo tanto todo uno conmigo y yo me vulevo uno con todo. Pues revelo que en el secreto de las cosas todo es y no ha dejado de ser uno con lo Infinito.

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Histórias Espirituais - Sonhos de Faraó

#faraó#egito#hebreus#judeus#exodo#exilio#mitzraim#galut#geula#ivrim#yehudim#paró#halomot#sonhos#interpretação dos sonhos#sonhar#sonho

0 notes

Text

im literally so dumb i just said

“Jason I am agitato grande Jason I am muy disgutante And muy disappointe And muy naseatus And me mitzraim hotzionno dayenu- wait i dont speak jewish.. *silence* jeWISH ISNT A LANGAUGE- ITS FUCKING HEBREW-”

im so stupid.

#im a fucking iditot#falsettoland#falsettos#march of the falsettos#everyone hates his parents#the marvin trilogy#musicals#Theater

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

∞

“jason I am agitato grande. jason I am muy disgutante and muy disappointe and muy naseatus and me mitzraim hotzionno dayenu” - everyone hates his parents from falsettos

#this feels like a weird line to love but its so stupid n fun to song#and the awkward silence after makes it#also so to you have paintings of dicks dont talk to me about taste

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A link to my personal reading of the Scriptures

for the 27th of january 2025 with a paired chapter from each Testament (the First & the New Covenant) of the Bible

[The Letter of Romans, Chapter 10 • The Book of 2nd Kings, Chapter 18]

along with Today’s reading from the ancient books of Proverbs and Psalms with Proverbs 27 and Psalm 27 coinciding with the day of the month and year (with the consummate book of 150 Psalms in its 1st revolution this year), accompanied by Psalm 38 for the 38th day of Astronomical Winter

A post by John Parsons:

We are re-reading the story of the exodus for the current Jewish year...

The exodus from Egypt (i.e., metziat mitzrayim: יציאת מצרים) is perhaps the most fundamental event of Jewish history; it is "the" miracle of the Torah. In addition to being commemorated every year during Passover (Exod. 12:24-27; Num. 9:2-3; Deut. 16:1), it is explicitly mentioned in the first of the Ten Commandments (Exod. 20:2), and it is recalled every Sabbath (Deut. 5:12-15). The festivals of Shavuot (Pentecost) and Sukkot (Tabernacles) likewise derive from it (the former recalling the giving of the Torah at Sinai and the latter recalling God's care as the Exodus generation journeyed from Egypt to the Promised Land), as does the Season of Teshuvah (repentance) that culminates in Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement). Indeed, nearly every commandment of the Torah (including the laws of the Tabernacle and the sacrificial system) may be traced back to the great story of the Exodus, and in some ways, the entire Bible is an extended interpretation of its significance. Most important of all, the Exodus both prefigures and exemplifies the work of redemption given through the sacrificial life of Yeshua the Messiah, the true King of the Jews and the blessed Lamb of God...

The deeper meaning of exile concerns blindness of the divine presence. The worst kind of exile is not to know that you are lost, away from home, in need of redemption... That is why Egypt (i.e., Mitzraim) is called metzar yam - a “narrow strait.” Egypt represents bondage and death in this world, and the exodus represents salvation and freedom. God splits the sea and we cross over from death to life. Since Torah represents awareness of God's truth, Israel was led into a place of difficulty to learn and receive revelation (Gen. 46:1-7). Out of the depths of darkness God's voice would call his people forth. Likewise we understand our "blessed fault," the trouble that moves us to cry out for God’s miracle in Yeshua... Indeed the New Testament states that Yeshua "appeared in glory and spoke of his exodus (τὴν ἔξοδον αὐτου) which he would accomplish at Jerusalem" (Luke 9:31).

[ Hebrew for Christians ]

========

Psalm 81:10a reading:

https://hebrew4christians.com/Blessings/Blessing_Cards/psalm81-10a.mp3

Hebrew page:

https://hebrew4christians.com/Blessings/Blessing_Cards/psalm81-10a-lesson.pdf

1.24.25 • Facebook

from Israel365

Today’s message (Days of Praise) from the Institute for Creation Research

0 notes

Photo

English - Polish - Yiddish

Passover - Pejsach / Pascha / Pesach - פסח [peysech] Passover seder - seder - דער סדר [seyder] seder plate - talerz sederowy - די קערה [kare] Aggadah - Hagada - די הגדה [hagode] matzah - maca - מצה bitter herb - morer, gorzkie zioło - דער מרור [morer] egg - jajko - דאָס אײ horseradish - chrzan - דער כרײן lamb - jagnię - לאַם wine - wino - ווײַן

Egypt - Egipt - מצרים [mitzraim] pharaoh - faraon - פּרעה [pare] slave - niewolnik - דער שקלאַף slavery - niewola - די שקלאַפֿערײַ plagues - plagi - פּלאָגן the Red Sea - Morze Czerwone - ים סוף flight - ucieczka - אַנטלויפן The Exodus, The Departure of Egypt - wyjście z Egiptu - די יציאת מצרים [yetsies mitsraim] desert - pustynia - דער מידבר [midber]

holiday - święto - רוה טאג miracle - cud - נס [nes]

אַ כּשרן, פֿריילעכן און זיסן פּסח

#passover vocabulary#passover vocabulary list#passover vocab#passover vocab list#english vocabulary list#polish vocabulary list#yiddish vocabulary list#languagesandstuff#my post#pesach vocabulary

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Origin of Hide and Seek

Pesach is just around the corner and all of our thoughts turn to redemption—the ten plagues of deliverance, the exodus from Mitzraim, the splitting of the sea, the annihilation of our oppressors and enemies, arrival at Har Sinai, the unity of the nation encamped at the foot of the mountain, etc. We were in a state of extreme joy and euphoria as we anticipated the giving of the Torah.

But something unexpected happened (Shemot 20:15): וְכׇל־הָעָם רֹאִים אֶת־הַקּוֹלֹת וְאֶת־הַלַּפִּידִם וְאֵת קוֹל הַשֹּׁפָר וְאֶת־הָהָר עָשֵׁן וַיַּרְא הָעָם וַיָּנֻעוּ וַיַּעַמְדוּ מֵרָחֹק (All the people saw the thunder and lightning, the sound of the shofar, and the mountain smoking; and the people saw and they trembled and stood at a distance). The last thing they expected was to witness a spectacle that terrified them. They were afraid of dying and wanted Moshe to bring the Torah to them. Moshe told them not to be afraid, and that it’s all just a big test. Hashem wanted them to fear Him, not the ‘scary spectacle.’ However, the people didn’t budge. They weren’t going anywhere. On the other hand, Moshe was drawn into the darkness (Shemot 20:18): וַיַּעֲמֹד הָעָם מֵרָחֹק וּמֹשֶׁה נִגַּשׁ אֶל־הָעֲרָפֶל אֲשֶׁר־שָׁם הָאֱלֹקִים (The people stood at a distance but Moshe was drawn near to the thick darkness where G‑d was). It is interesting that the final test before receiving the Torah was to experience thick darkness—a place where the path forward would be obscured, where everything would appear distorted, a reality in which nothing would make any sense—a state of confused existence where even the ‘laws of nature’ would cease to exist. Why was this necessary, and what can we learn from this?

When we arrived at Har Sinai, we were very excited, and we enthusiastically said (Shemot 19:8): כֹּל אֲשֶׁר־דִּבֶּר יְיָ נַעֲשֶׂה (All that Hashem has spoken, we will do). But it is also written (Shemot 19:17): וַיּוֹצֵא מֹשֶׁה אֶת־הָעָם לִקְרַאת הָאֱלֹקִים מִן־הַמַּחֲנֶה וַיִּתְיַצְּבוּ בְּתַחְתִּית הָהָר (Moshe took the people from the camp to meet G‑d, and they stood in the tachtit of the mountain). Literally, this means that they stood at the foot of the mountain, but our Sages learned something much deeper about what was really going on (Avodah Zarah 2b): ואמר רב דימי בר חמא מלמד שכפה הקב"ה הר כגיגית על ישראל ואמר להם אם אתם מקבלין את התורה מוטב ואם לאו שם תהא קבורתכם (Rav Dimi bar Chama said that [the word tachtit] teaches that the Holy One, blessed be He, overturned the mountain like a barrel over Yisrael and said to them, If you accept the Torah, great! But if not, there [under the mountain], will be your burial). In other words, the Torah was accepted only through an aspect of coercion. (And as is known, it wasn’t until the days of Mordechai and Ester that we accepted the Torah completely out of love.) So, on the one hand, we were very enthusiastic, excited and intent on doing everything Hashem said, but on the other hand, we were hesitant and afraid. How can we explain this contradiction?

Let’s bring up another contradictory idea. The verse (20:18) said that G‑d was in the thick darkness [הָעֲרָפֶל, ha-arafel]. What was G‑d doing in the darkness? Isn’t the Torah light (Mishlei 6:23)? And if Moshe was going to receive the Torah, why was he entering into the darkness to receive it? Although it seems bizarre and paradoxical, both are equally valid realities: the Torah is light and Hashem dwells in the darkness. As the Baal Ha-Turim points out on that verse, the gematria for הָעֲרָפֶל is identical to the gematria for the שכינה [Shechinah, the Divine Presence], i.e. 385. This is not coincidental. This is hidden a secret in the Torah that teaches us that when Moshe was drawn near to the thick darkness, he was being drawn near to the Shechinah. The darkness was exactly where Hashem was to be found. We can also read about this perplexing truth elsewhere. For example, David ha-Melech said (Tehillim 18:12): יָשֶׁת חֹשֶׁךְ סִתְרוֹ (He made darkness His concealment). He also said (Tehillim 97:2): עָנָן וַעֲרָפֶל סְבִיבָיו (Cloud and the arafel surround Him). And Shlomo ha-Melech, at the dedication of the Beit ha-Mikdash said (Melachim Aleph 8:12): יְיָ אָמַר לִשְׁכֹּן בָּעֲרָפֶל (Hashem said [that He would] dwell in the arafel).

Instead of simplifying the matter, we now have two paradoxes! Paradox #1: the people were enthusiastic yet terrified and pulled back. Paradox #2: Hashem who is light and whose Torah is light dwells in thick darkness. Can there be a single explanation for these two apparently contradictory and paradoxical ideas?

When someone chooses to do teshuvah on some particular aspect of his life or even after chasing meaningless pursuits throughout his entire life, he often experiences something for which he was completely unprepared. His life may have been going along quite smoothly up to this point; yet, the moment he commits to walk in the ways of Hashem and to purify himself, everything seems to fall apart. He may encounter many obstacles, and life as a whole may get extraordinarily difficult, being overrun by many setbacks. He begins to wonder if Hashem is even interested in his teshuvah. After all, he may have done some terrible things, maybe even many terrible things. Perhaps Heaven is simply rejecting him, plain and simple, G‑d forbid. Such a person’s enthusiasm may wane and he may become despondent or depressed, possibly even abandoning the thoughts of teshuvah that he originally had, G‑d forbid. However, if he understood the dynamics of what was happening and that Hashem wasn’t rejecting him, he wouldn’t have come to such a state. So what is going on? Why do things like this seem to happen so often?

When we sin, we bring upon ourselves (and upon others) judgments, i.e. indictments for crimes committed against the King and His kingdom. These indictments come from the Attribute of Justice [מִדַּת הַדִּין, middat ha-din] which rightly accuses us and denounces us. Not only that, but obstacles are often set up preventing us from walking in Hashem’s ways. Why should we be permitted to waltz effortlessly into a sublime relationship with Hashem when we did what we did, defiling ourselves and ruining His world? The middat ha-din is not unfair; it is just. After all, it is written (Tehillim 37:28): כִּי יְיָ אֹהֵב מִשְׁפָּט (For Hashem loves justice).

However, there is also the Attribute of Mercy [מִדַּת הַרַחֲמִים, middat ha-rachamim] which stems from the fact that Hashem loves kindness, as it is written (Michah 7:18): כִּי־חָפֵץ חֶסֶד הוּא (For He desires chesed). So on the one hand, the Holy One, blessed be He, loves justice, yet on the other hand, He desires chesed and loves Yisrael, His beloved children, even after they sin, as it is written (Malachi 1:2): אָהַבְתִּי אֶתְכֶם אָמַר יְיָ וַאֲמַרְתֶּם בַּמָּה אֲהַבְתָּנוּ הֲלוֹא־אָח עֵשָׂו לְיַעֲקֹב נְאֻם־יְיָ וָאֹהַב אֶת־יַעֲקֹב (I have loved you, said Hashem, but you said, How have You loved us? Isn’t Esav a brother to Yaakov, declares Hashem, yet I love Yaakov).

In short, there must be din and there must be rachamim. But what’s the solution for this paradoxical situation? Can both co-exist?

The solution is that which is stated explicitly in the Zohar Ha-Kadosh (Emor 99b): וְאָף עַל גַּב דקב"ה רָחִים לֵיהּ לְדִינָא כד"א כִּי אֲנִי יְיָ אוֹהֵב מִשְׁפָּט נֶצַח רְחִימוֹי דִּבְנוֹי לְרֶחִימוּ דְּדִינָא (Even though the Holy One, blessed be He, loves din, as it says [Yeshaya 61:8], ‘For I, Hashem, love justice’, the love of his children trumps the love of din). If only we could hold this truth in the forefront of our minds constantly, imagine how much anguish and heartache we could avoid in life! Even though Hashem loves din, he loves us even more. As a result, although He doesn’t push away din, for He created it and agrees with it, and He knows that we are not worthy to drawn near to Him for the abundance of our sins, what does He do? He places his middat ha-rachamim within his middat ha-din. He hides in the midst of the darkness! He’s not rejecting us. He’s not indifferent to our teshuvah and to our efforts to draw closer to Him. It’s as if He’s playing hide and seek, and He wants us to find Him in the midst of all the so-called obstacles, as it is written (Yeshaya 55:6): דִּרְשׁוּ יְיָ בְּהִמָּצְאוֹ (Search for Hashem when He can be found). After all, the truth is that there are no such things as obstacles. They’re all just illusions, as stated explicitly in Likutei Moharan 115: כִּי בֶּאֱמֶת אֵין שׁוּם מְנִיעָה בָּעוֹלָם כְּלָל (For in truth, there is no obstacle in the world at all). Do we get it? Do we see why the so-called obstacle isn’t really an obstacle at all? It is because Hashem arranged them and hid Himself within them; therefore, they are the path to Hashem. And if they are the path to Hashem, they’re not obstacles, are they? Yes, they are challenges and difficulties, but they don’t prevent us from accessing Hashem. On the contrary, they are the very route to Hashem.

This being the case, why was Moshe the only one who was drawn into the darkness? It is because not everyone has this understanding, or even if they do ‘know it to be true’, they don’t ‘feel it to be true’. And the only one who had this knowledge, this da’at, was Moshe Rabbeinu. Therefore, he was drawn into the darkness—literally. He was compelled to enter the darkness, not for himself, but on behalf of the people, to bring the Torah out to them. Therefore, if we are to find Hashem in every situation in life, especially during the difficult times, we need da’at. That’s why it’s the first berachah of request in the Shemoneh Esrei. We need it like we need air to breathe. Without it, we’re constantly falling into the traps laid by the Sitra Achra to ensnare us. But with da’at, we can recognize the trap at the moment we encounter it, and know and feel that it’s just a test—that Hashem is there and that what He really wants is not for us to become entrapped but to draw closer to Him. It is as R' Nachman writes (L.M. 115): וּמִי שֶׁהוּא בַּר דַּעַת הוּא מִסְתַּכֵּל בְּהַמְּנִיעָה וּמוֹצֵא שָׁם הַבּוֹרֵא בָּרוּךְ הוּא (Someone who has da’at, he looks into the obstacle and finds the Creator, blessed be He, there). And if Hashem is there, then that’s where we need to go.

All of this may seem like a rather convoluted way to draw close to Hashem. Couldn’t He have designed the system another way, in a clear and direct way? He has unlimited abilities, after all. So how come He designed it in a way that seems like we’re all involved in some kind of surreal game of hide and seek? To answer that question we need to go back to the Garden. What did Adam do after he sinned? It is written (Bereshit 3:9-10): וַיִּקְרָא יְיָ אֱלֹקִים אֶל־הָאָדָם וַיֹּאמֶר לוֹ אַיֶּכָּה׃ וַיֹּאמֶר אֶת־קֹלְךָ שָׁמַעְתִּי בַּגָּן וָאִירָא כִּי־עֵירֹם אָנֹכִי וָאֵחָבֵא (Hashem G‑d called to the man and said to him, Where are you? He said, I heard Your voice in the garden, and I feared because I am naked, so I hid). Adam, i.e. we, initiated the game, not G‑d. And since we hid from G‑d, He hides from us. It is middah k’neged middah. In His infinite wisdom, G‑d knows that the only way for us to rectify this sin is to replace fear with emunah and enter into the thick darkness. Then, instead of Hashem asking us אַיֶּכָּה (Where are you?), we will ask Him אַיֶּכָּה? This is the ultimate tikkun.

May we merit to find Hashem in all of our challenges and difficulties in life and never abandon the hope of finding Him in the midst of our thick darkness.

0 notes