#mayor lear

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Blossom (Bre'Elle Erickson) and The Mayor (Natalie Rae Wass). Puffbots (Jessica Smith and Amanda Chial). Don't mind me taking a moment to remember just how great our costumes were! Shout out to our costumer Sarah Simon who also worked on KamehameHamlet. Photo by Alex Wohlhueter.

Play-Dot Archives: Mayor Lear May Wrap Up

Thank you all for joining us for a very fun and silly Mayor Lear May (week) and enjoy this last-minute promo (below) we made for our final weekend of the run in 2017 I'll link all the archival posts below, and don't forget to join us for our Spirit Bomb Rally Stream tomorrow! Shalee and will be back to tackle the ever-growing list of reblogs so hop in and ask us a question or two about Mayor Lear or Kamehamehamlet! Until then, Lord Abracadaver of Minneaspolissville, signing off. Mayor Lear Archival Posts:

Mayor Lear Promo Poster

What is Mayor Lear?

Mayor Lear Projections

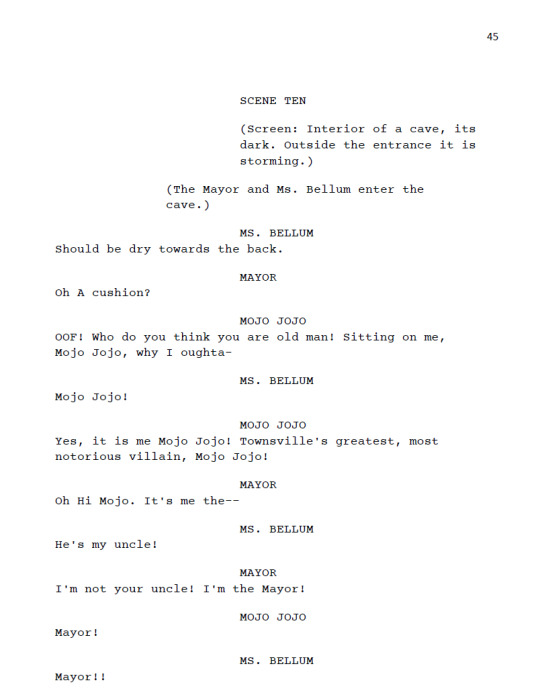

Mayor Lear's Cave Scene

#mayor lear#shakespeare#power puff girls#theatre#theater#ppg fanart#ppg fanfic#ppg fandom#ppg blossom#playdotarchives

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

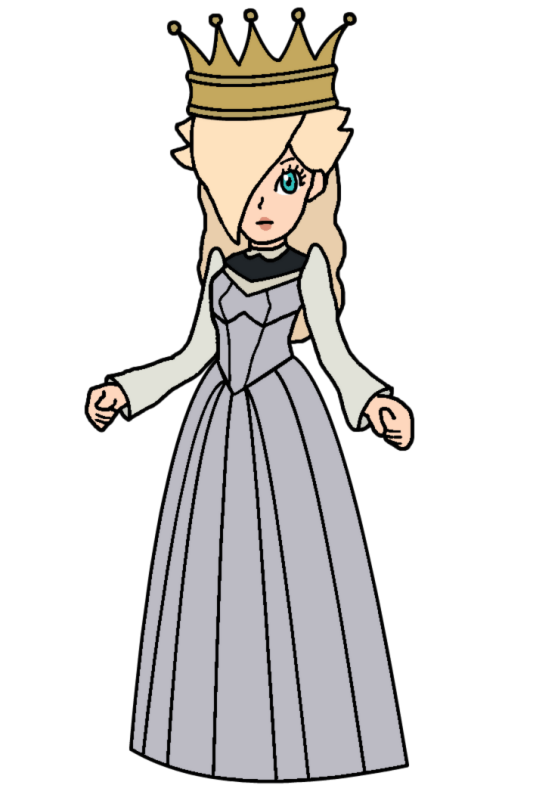

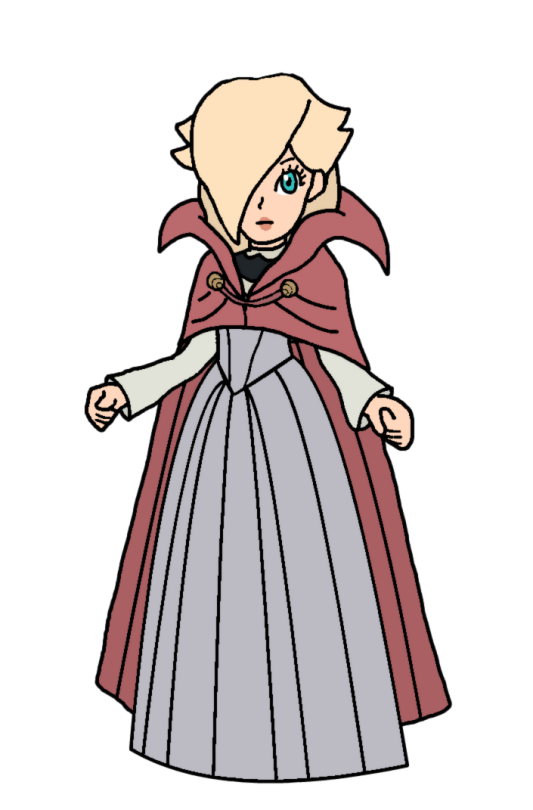

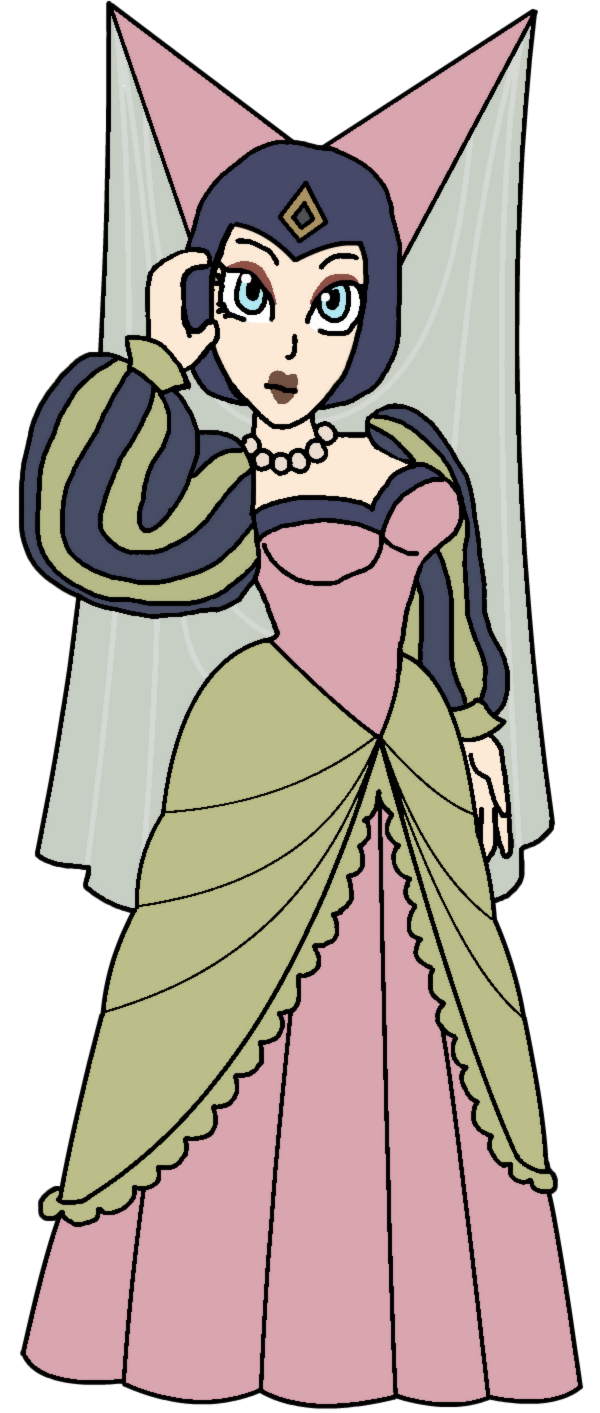

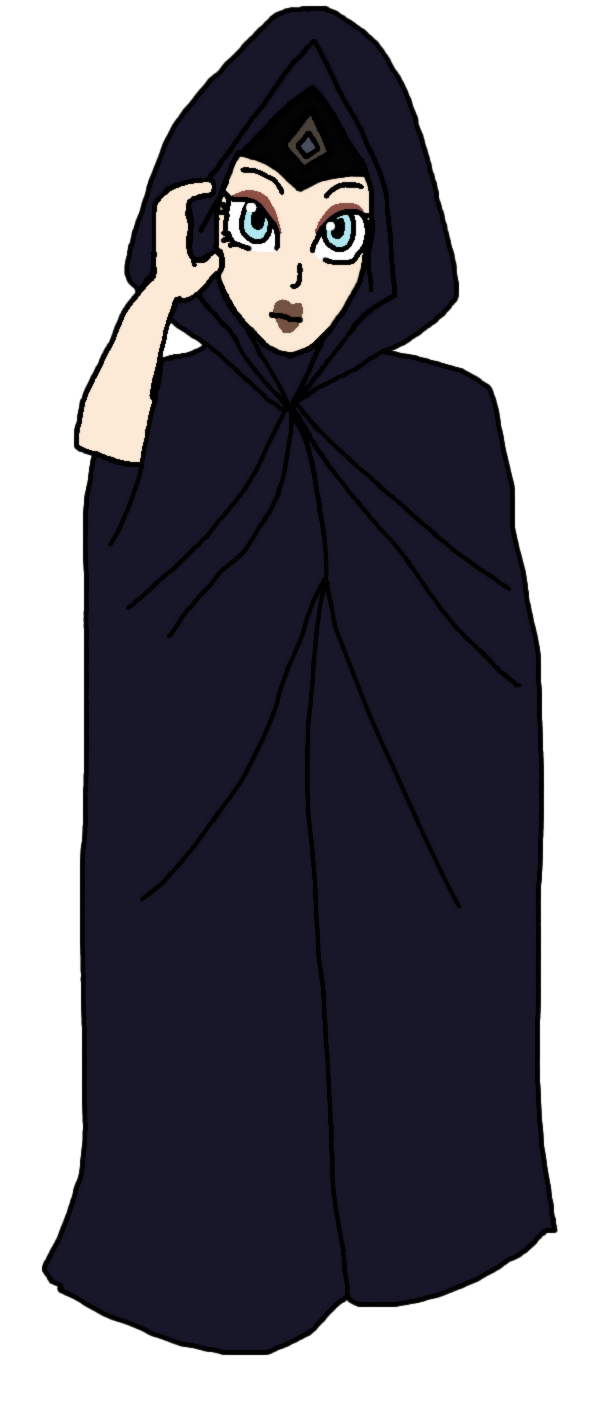

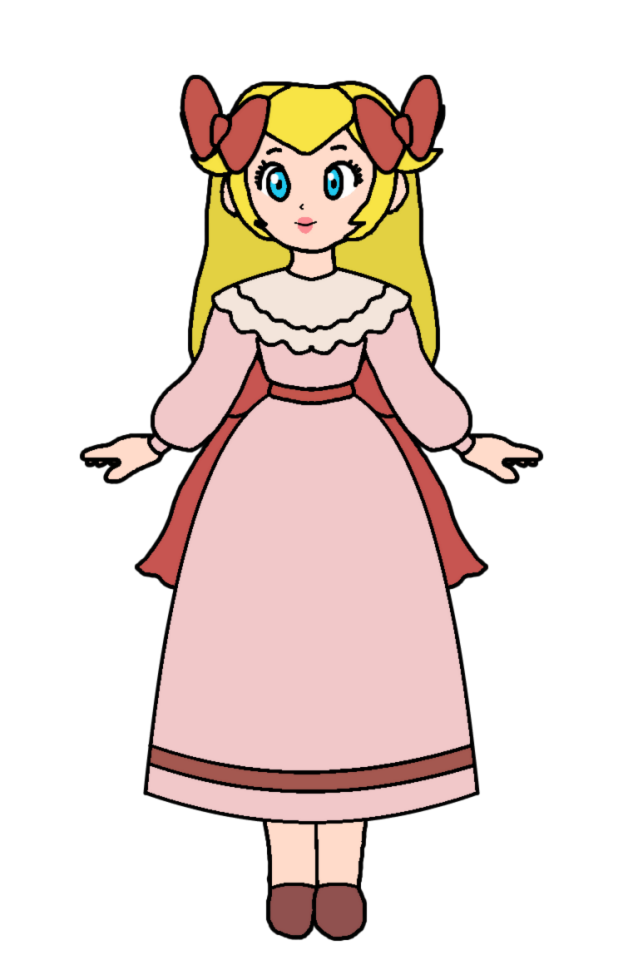

Mario girls cosplaying as characters from Manga Sekai Mukashi Banashi/World Fairytale Masterpieces/Tales of Magic

1 + 2. Cordelia

3 + 4. Regan

5 + 6. Goneril

7 + 8. Clara

9. Orihime

10. Elsa

#manga sekai mukashi banashi#world fairytale masterpieces#tales of magic#the nutcracker#clara#dream world princess#orihime#tanabata#princess elsa#elsa#knight of swans#king lear#cordelia#goneril#regan#princess peach#peach#rosalina#pauline#mayor pauline

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

[4] It's Good to Be King | mean king!harry

MAIN MASTERLIST

Series Summary: Harry, a handsome, but ill-mannered new king, bound by tradition, must select a queen, and against all expectations, he chooses Y/n, a street beggar. Now, Y/n finds herself caught between the gilded cage of royalty and the cold, harsh simplicity of her past, navigating a court shocked by her presence and a king who revels in the scandal of it all.

Note: Harry is mean/uncouth in this, though things do get better. He doesn't treat anyone around him with much respect at all. Expect to not like him much at first. Also, this is set in the 1800s England, and while not completely historically accurate, I did my best to keep it as accurate as possible.

Ch. 4 Word Count: 8,762

Ch. 4 Warning: Talk of menstruation and bleeding, mentions of blood and wartime, aggressive male behavior (Harry gets a little violent with the Lord Mayor), discrimination

It's Good to Be King Masterlist

. .

Y/n hadn't been given a choice on the style of her wedding dress. It had already been selected for her. But it was breathtaking. She'd never seen anything like it before, and that she would soon be wearing it in front of the kingdom? It was no wonder she was not given a choice. She would never have picked such a lavish thing because she did not feel worthy of it.

That morning was her first fitting. She stood with her arms stretched outward, one person on each side, holding her steady, while the dressmaker pinned and tucked and cut at the lace and the silk, adjusting it to her size. Mrs. Mable was the royal seamstress, and Y/n couldn't help but feel she held some contempt for her. The way she was pulling and prodding, even poking her with pins, all felt intentional.

"Ow!" Y/n winced when Mrs. Mable stuck a pin through the silk skirt, and it grazed her skin. Again. She was becoming ireful toward the woman when all she wanted was to relive the kiss she'd just had with the king, not a few hours earlier. She'd received a handful of strangers into the Rose Room for the fitting, and she'd been soaring with hot cheeks and a softly fluttering heart before Mrs. Mable got her hands on her.

She didn't know that the lace had its own name, Honiton, or that the diamond necklace they showed her (to be kept in its satin case until the day of the wedding) was Turkish. The dress had an off-the-shoulder, open neckline, with layered sleeves down to her elbows, all lined with the special lace. The silk corset bodice was pointed downward in a deep V, while the skirt was full and pleated silk.

Staring at her figure in the mirror, she felt like a fraud. How had this happened to her? How had luck (or misfortune, she wasn't sure yet) stricken her so abruptly? It was one thing to have been expecting her new lot, to have been raised up for it and accustomed to royal life, but it was another to have been plucked from the streets, shoved into it blindly, and to have people enraged by her presence without ever getting to know her first.

"Please be careful. You're poking her…" Phoebe said to Mrs. Mable.

The woman, whose face was hidden behind silk and lace as she bunched up the bottom hem of the dress, dropped her pin cushion to the floor as she jabbed another sharp object into the fabric. "She'll be fine. I've only nicked her a few times. It's part of the work if you want it done properly."

"But she will be your queen. She is to be treated with the utmost care and —"

Mrs. Mable stood up and pulled at the back collar of Y/n's dress, making her nearly stumble. "Queen Consort. There is a difference. We'll see if she makes it that far."

"The King is taken by her. She will prove you all wrong. You'll see." Phoebe crossed her arms over her chest and glared at the dressmaker.

Y/n glanced at Phoebe in warning. She didn't want people arguing over her status. It wasn't worth it. If Mrs. Mable wanted to treat her like she was still a street beggar, all while fitting her for her royal wedding gown, then so be it. She'd soon learn who she was dealing with, and Y/n would not forget the treatment she was being subjected to.

"We will see." Mrs. Mable turned Y/n around and took her measuring tape to her hips, waist, and bust, before spinning her around again to help her step out of the dress. "I'll return two days before the wedding for the final fitting, along with the finished veil. And don't get too heavy-handed with tarts or the dress will be too tight."

Y/n looked down at her figure and glanced at it in the mirror. She hadn't gained very much weight at all, but kept being told she needed to gain more. Now there was the dressmaker telling her to go lightly on the very tart Y/n requested to have in the room for herself and anyone else who wanted some. Her mood was a little foul after having been prodded and nicked, so she huffed, stepping past Mrs. Mable to grab a piece of tart and shove it into her mouth as she stared at the woman in defiance.

When the dressmaker and her helpers left the room, Phoebe closed the door and leaned into it, shaking her head. "That woman is awful. There's gossip that she's been vying to have her daughter meet the king before you two are wed."

Y/n slid her standard dress back on, and Phoebe pushed herself from the door to help fasten the back. "What do you mean? To present her to him? For marriage?"

"I believe so."

She knew that the middle and upper classes of Thornekeep were spoiled and mean. So, it shouldn't have surprised her that Mrs. Mable didn't take seriously her eventual new title, and that she hoped her daughter could steal the designation for herself. Y/n was slowly learning about the politics of the kingdom and she was going to have to brace herself for what was soon to come.

"Now let's finish that tart."

. .

Harry was seething. The council had found the Lord Mayor guilty, but he was only charged a measly fine for his transgression. A fine! Imagine forcefully taking the king's wife-to-be from her quarters, openly disrespecting the crown, and humiliating her in front of the kingdom… and the punishment was nothing more than a fine?

He couldn't believe it when the news was sent to him. He'd planned on an in-person visit to retrieve the brooch from the Lord Mayor, but when he learned he'd gotten away with nary a slap to the wrist, he immediately sought out his Proctor to go back before the council to appeal the decision. His only recourse was to prove she'd been hurt in some way.

He stormed into the room where Y/n was in the middle of her etiquette class, and the governess stood from her chair quickly and lowered her head. "Your Majesty."

He breezed by the woman and pulled Y/n's chair out, dropping down to his knees in front of her without so much as a glance toward the governess. Y/n gasped when he pulled her skirts up and he put his hand over the dark blue and brown spot on her knee. He'd seen the bruise the morning before when he tried to get her to join him in his tub.

"This. Did this happen when they pushed you around and removed you from the castle?"

Y/n blinked slowly at him as he looked up at her. He looked desperate, wild. She had nearly forgotten the bruise herself and she certainly hadn't realized he'd even seen the thing.

"Yes. I was pushed down to my knees and hands from the steps. It was bruised much worse at first, but it's better now. Can hardly feel it really."

"And who pushed you? His name, Y/n. Was it the Lord Mayor?"

"I… I'm not sure. It was two men… The Lord Mayor never touched me except to take the brooch."

She watched as he clenched his jaw and looked down at the bruise, his thumb running along the top of her knee. "He was there, though. Did you hear him order the men to take you?"

Y/n thought back to that awful morning, and she nodded. "Yes. He said that your duties fall on him when you're away and that it was his command. And Niall! The guard, who's just there outside the door. He was there and he heard it and saw it all. That's who he said it to."

"So he ordered men to do this to you. And we have a witness." He pushed himself to stand up and stepped away quickly, back toward the door, before he turned to speak again. "I will get your brooch back for you today."

When the door was closed, the governess looked shocked as she watched Y/n slide the fabric back down her legs.

"What? Is this what it takes for you to notice my presence? The king himself must barge into your classroom and cause a disturbance for you to realize I'm sitting here?"

The woman wiped her hands down her dress and turned toward the table to speak. It seemed she only spoke to Y/n with her back turned to her. "I notice. I've already taught you plenty—"

Y/n stood up. "You should speak to me with more respect from now on. I will be the queen soon. If not, I'm sure the king will have words with you next. I will not return for any remaining classes. I understand now that I have much better manners than even you do."

She dismissed herself and stepped out of the room with that awful woman. Niall was waiting at the door, and he greeted her with a polite, sharp nod. "At least you and Phoebe are kind to me," she said, smiling at him as she began to walk toward the grand staircase that would lead them up to the king's chambers. "And you're kind to Phoebe as well. Thank you for that."

Niall didn't speak often. His duties didn't allow for it. But a few times he let his guard slip — so to speak — and he'd say a few words. "I've no reason to disrespect you or your lady-in-waiting."

Y/n smiled to herself as she continued up the steps. The stairs were wide, and they seemed to go on forever. The landings, on the way up, split the levels into threes, and the stairs curved around and continued up until they found the floor with the king's chambers and the Rose Room, where her chambers were. "If you disrespected Phoebe, I'm sure she'd be heartbroken. She rather likes you."

Before Y/n could pull the door open with it's heavy iron knob Niall spoke. "She does? Did she say something?"

She looked around the hallway and then up at Niall. "Of course she did. But that's nothing I can discuss with you. Secret is safe with me. No need to worry."

. .

Y/n had a large bruise on her left knee and a castle guard as witness. Harry doubted anyone else would offer to attest. He'd bring Niall with him the following day to meet again with the Proctor for proof of the Lord Mayor's mishandling of his queen-to-be. But first, he needed to find the Lord Mayor to deal with him at once and retrieve the brooch.

He didn't bother announcing his arrival or sending the house steward to call to the Lord Mayor that he was there. And it was good to be king because it meant that people had to listen to what he asked of them, even if they didn't much like him. So when he lowered his hand and stepped inside, the house steward bowed his head and let Harry in without a peep.

He wasn't hard to find. Harry spotted him quickly in his first-floor study, reading, and the Lord Mayor stood in haste. "Your Majesty. To what do I owe the honor of your sudden and unexpected presence?"

The king stepped toward the large bookshelf and ran a finger over the hard bindings. Harry's saunter and cold grin were vexing. The Lord Mayor had never met anyone so plaguy in his life. The king was full of himself and was purposefully bucking tradition. He had a much more suitable and beautiful option than Y/n, which the king would have loved.

"You have something that belongs to Y/n. The woman to whom I will be wed at the end of next week."

"I have nothing in my home that belongs to that girl."

Harry bit down on his molars as his dark gaze seared at the Lord Mayor before he bounded toward him, heavy steps over the wooden floors, until the king's hand was wrapped around the man's throat and his back pressed against the wall.

"I will not be disrespected by you once more, Virgil," he spat the name between his teeth. "First, you insult me behind my back and make a show of carting off my wife-to-be and her family like animals. And now you lie to my face? If you do not produce the brooch, that will be considered theft, which you will regret when I drag you before the council."

The man's eyes were wide as he tried to pry the king's strong grip from his windpipe. He wheezed as the back of his throat constricted when he attempted to speak.

"I can't hear you. Speak louder, worm."

Harry was enjoying watching Virgil squirm and gasp. He could squeeze tighter and hold on for a few minutes longer, be done with the man for good. But then, having to explain to Parliament what had happened would be awfully annoying, so he opted for just scaring him instead.

"You were much easier to subdue than I imagined. But then again, you have aged like spoiled curd. Flimsy muscles trying to pry my hand away. Give it another go. Let's see what you've got, old man."

The Lord Mayor did not have it in him to pry Harry's hand from his throat. And it was true, he was getting older and his body was not as virile as it had once been. He was no match for the young king. He tried twisting, but instead of working himself free, Harry released him and stepped back as the man fell to the floor and violently coughed.

Harry laughed as he stepped around the Lord Mayor to his desk and sat down in the chair, closing the book Virgil had been reading. "Where's the brooch? Or should I fetch your wife and tell her what you've done?"

The Lord Mayor, with his palm at his throat, coughed. "King Styles…" He inhaled sharply, his voice pinched as he tried to speak after the king had restricted his air. "I was protecting you. Protecting Thornekeep!"

Harry glared at the pathetic man, still on the floor, trying to push himself to his knees. "You defied me and the kingdom. You showed contempt toward Y/n and her family." He pushed himself from the chair and stood over Virgil, looking down at him. "And on your command, you had two men push her down to her knees, inflicting pain and making her bruise. That is assault, which will not go unpunished."

The Lord Mayor finally leveraged himself to stand, placing a hand on the bookshelf and pulling himself upward. "My Lord, please. The girl is a street beggar. Her word is not to be trusted. My advice is to consider another—"

Harry stepped in closer, his boots bumping into the old man's as he pushed him by his chest, his back against the bookshelf. "Your advice is not needed nor warranted. I am King. I will choose what I please, and I will have what I want."

The man stood with his hands upward as he bent back and away from the king, still standing toe-to-toe with him. "I didn't hurt the girl or her family. I simply returned them from where they came."

"I will have you tried for treason. Assault! What you did to her is inexcusable. You flagrantly disobeyed my command. If the council doesn't find you guilty, I do. And if they don't impose a more severe penalty, I will. I'll take this into my own hands if need be."

"There's a beautiful young woman. Much lovlier than Y/n. Pearl is her name… Smart, golden hair, a virgin. Her family comes from—"

Harry laughed loudly, cutting Virgil off. "I will marry Y/n. I want no one else for my queen. You have overstepped your duties with me, and after I'm done with you, you will not be welcome in or near the castle. You will be stripped of your title, and you and your wife will be considered a disgrace to the kingdom. I will see to it."

"Please… My Lord…" He kept his hands upward in surrender. "This is excessive. Do you really think that having my title stripped will be well received by the proletariat who elected me? It would be bedlam! The people would not stand for such controversy!"

"Has it not gotten into your skull, yet, that I am not concerned by outrage or controversy. Let them be angry. Anger is better than complacency."

"Complacency is prosperous. Anger is costly."

"And I have the means to pay whatever the cost if need be."

"You are going to bankrupt the kingdom with your frivolous actions. Your father would be turning in his grave if he knew what you were up to."

Harry spat, "Good. I hope my father rots. Let the spoiled aristocracy learn to work for their meals like everyone else. Have you seen the rookeries? Do you know the reality of what sits on the outskirts? Thornekeep is prosperous, but only for you. Only for those who don't need it."

"Oh, pish!" Virgil laughed incredulously. "You act like some kind of martyr, yet you've seen the rookeries of Thornekeep but once! Stop this madness! You will drive our kingdom into the ground with your foolishness! You've no idea the damage it will cause—"

Harry slammed his fist into the wood of the bookcase directly next to the Lord Mayor's head. "I have been to the slums in many a kingdom. You forget, maggot, that I spent most of my adulthood outside of Thornekeep as commander-in-chief of our kingdom's armies. I led my men to victory in dangerous battles across the land. I fought alongside the downtrodden. I've lived it. I've seen it all up close. I do not care who hates me. Let my father's rest be disturbed. I care not!"

"Heavens! What is going on?" Virgil's wife appeared in the doorway, the look of surprise on her face quite amusing to Harry.

Harry patted the Lord Mayor's shoulder and stepped back. "We were just having a good ol' chat about my future wife. Though Virgil here does seem to fancy a golden-haired girl called Pearl, I explained to him that I'm a man with morals and already spoken for. I'm sure any other man would be grateful for a chance with her. Even married ones like yourself."

The woman blinked in surprise at her husband. "Little Pearl? You mean Mr. and Mrs. Mable's daughter?"

Harry nodded, clasping his hands behind his back as he moved toward the doorway and smiled casually at her. "Yes. I believe that was who he was referring to. He's quite fond of the girl. I don't know how he's become privy to her virginal status, but your husband seems quite excited about that detail. Bit too young for me…"

He leaned in closer to the Lord Mayor's wife and spoke quietly. "I prefer 'em thicker through the calf and more mature personally, but your husband has his own tastes, I presume. Just keep an eye on him around little Pearl, will you?"

"Your majesty!?" The woman looked at the king, her mouth agape.

Harry grinned back at the man. "My wife's brooch, the one you stole? Have it sent to her within the hour, or I will be back again before nightfall."

. .

Y/n felt feverish and her insides were twisting and turning and squeezing tight, like her guts were being clamped together and wrung into a ball. Her sisters' bickering about the little game they were playing nearly tipped her over the edge of anger. She wanted to scream at them for silence. And most interestingly, she hadn't been able to finish the dinner that was served to her either. She had no appetite.

"Y/n. Are you feeling alright? You look unwell." Her mother put the back of her hand up to her forehead and gasped. "My child! You're burning hot! Phoebe! Where is Phoebe? Where is the guard?"

Y/n sighed and leaned forward as she closed her eyes, placing her elbows on the table. She wasn't worried about her manners at that moment. She felt like she was about to vomit. She heard her mother shuffle from the dining room to find Phoebe, who'd just wandered off only moments before.

If she hadn't been in so much sudden pain, she would have found it amusing that both Phoebe and Niall were nowhere in sight. Pushing herself from her chair to stand, her father rushed to her side. "Careful there. Here we go."

He leveraged her to standing, draping her arm over his shoulder, and began to help her back to the King's quarters. Before they had reached the stairs, Phoebe was there on her other side, arm drawn across her back to help. "I'm so sorry, madam! I didn't know you were poorly. I would have—"

"It's okay, Pheobe. Don't stress. I just need to lie down…"

She hadn't seen the king all afternoon and figured it was better that he wasn't seeing her in that state. He'd probably change his mind about her altogether if he saw her like that. If she wasn't healthy, what good was she to him? She inhaled sharply through clenched teeth when a spasm wracked her organs.

"Should we fetch a doctor?" Her father said.

"I just need to lie down. Please."

Y/n was brought to the king's bed and propped against the pillows when she noticed her mother, sisters, and Niall standing in the doorway watching. She didn't want an audience. She wanted to rest and needed the pain to go away.

Phoebe pulled at the blankets as she tried to make the bed more comfortable, and Y/n groaned. "Please… I just need rest. I'm not dying." Although she felt like she was.

"Yes. Of course. We'll leave you be. But we will be fetching a doctor whether you like it or not."

Y/n closed her eyes and rolled to her side as her father and Phoebe finally left the room. She groaned quietly and hugged herself around her stomach. She wondered if she'd eaten something bad. Or perhaps God was finally punishing her for her lustful thoughts and behavior.

Making herself into a ball, she clenched her teeth and felt something wet on her leg. She paused and slowly she reached down, bringing her hand under her chemise to feel, and when she lifted her hand in front of her face, she hadn't expected to see blood.

Blood coming from… there?

She pushed herself up to sit and pulled at her skirt. More blood. "Am I with my monthly sickness?" she whispered.

It had been some months since she'd bled at all, so to suddenly see blood… Well, it explained the pain she was feeling, though it'd never ached like that before. Hissing in pain, she bent forward and closed her eyes. At least now she knew she wasn't going to die.

. .

Y/n startled when the door to her chambers was suddenly pushed open, and in stepped a vexed-looking Harry. "Are you okay? I was told you've fallen ill."

"I'm not ill. Not in the sense that I'm sick with something I've caught. It's my…" She glanced away and sighed before looking him back in the eye. "Lunation."

"Lunation," he said the word slowly as he stood there, blinking at her. If she'd ever seen a confused man before, he was it. She nearly laughed at the expression on his face. To see the king look at her like that… Well, it wasn't something she felt she'd be seeing often. Had no one told him? She'd assumed everyone in the castle was talking about it by now.

"I'm having my menses."

"Oh! Yes. I see..." He stepped in closer next to her bed. "But why must you be here? I thought I'd find you in my room."

Y/n pressed her hands into the top of the bedding she sat upon. "Special mattress. They put this over the bigger one underneath. To catch my blood. I didn't think you'd want me next to you while I'm… well…"

Harry pushed his hand over the thin, smaller mattress and nodded. "Is it comfortable. Feels stiff."

"Nicer than anything I used to sleep on. I'm perplexed that this is meant for me to bleed on, and then it gets burned after. I'd have loved to have had this mattress at one time."

"Is it always like this for you? Your menses?"

Y/n leaned back and placed her hands over her stomach. "No. I haven't bled in some time. It was never on schedule anyway. The doctor said I must have been malnourished, and now that I'm eating well, my body is… revitalising was the word he used. He did come with tea and some medicine, and I feel much better now, though. He said I'll be fine."

She heard him push out a breath, like he'd been holding it in. "I've got something for you…"

He reached into the pocket of his waistcoat and pulled out the lovely brooch that had been taken from her. She smiled and sat up. "I'm so glad it's not been lost for good. It's so beautiful."

Harry reached for her hand and placed the golden breastpin into her palm. "Virgil will not be coming around here again. His invitation to the wedding has been revoked. My Proctor is working on having his title stripped."

"Thank you for getting it back for me. I realize my presence here is an incumbrance. To you and to everyone who cares about the crown. I can see I'm not well-liked in this castle."

Harry furrowed his brow and trailed his eyes over her figure. "Who else has been rude with you?"

"Besides you?" She tucked her lips into her mouth and watched his expression fall.

"My rudeness was meant to be a test of your resolve. Have I not amended myself to you?"

"Little by little, I suppose. I can't expect you to dote on me like a man burning with desire when you have none for me."

"I may not express my desires plainly, but I would not have you here if I didn't want you here. Perhaps it's not evident to you, my motivations, but you have been a surprise to me. A pleasant one. One that I intend on keeping for good."

Y/n had only been teasing at first, but his tiny confession was consoling to her. She knew there was a small flame burning between them, but his visage was not an easy one to see through.

"You chose me to anger the kingdom and to produce an heir. Are you saying now that there's more to it than just that?"

He clenched his jaw and slid his irises down to her bare feet. "It is true that was my initial purpose with you. But as I said, you've been a surprise to me."

She looked down at her feet as he ran the pad of his finger over her ankle and then upward to her shin, stopping at the bottom hem of her chemise. She swallowed as she looked back up to his face at his lips. The lips she'd kissed just the morning before. She hadn't been able to stop thinking about how it felt. It left such a warm, lingering sensation on her skin that she was sure she'd never be without it again.

Harry sat down at the edge of the mattress, his hand still on her shin, before he drew his fingers back down to her ankle. He'd been so worried about her at first. His assistant, Fred, told him she'd nearly fainted at dinner and had to be brought to bed, and something about a doctor. He probably should have waited to hear the rest, but his legs were carrying him quickly up to his room to get to her before he could even think about what he was doing.

When he didn't find her in his room, he dashed back into the hallway like a madman to the Rose Room, to her quarters. His heart had been racing, and he was already thinking the worst. Until he saw her propped against her feather pillows with her pretty eyes aimed wide at his intrusion.

The truth was, his mind had been in a fog since he'd kissed her. He wasn't a man who kissed his conquests typically. He found kissing to be a waste when his only intention was usually to get himself off. But Y/n's mouth was soothing and sweet. He could have let himself kiss her for hours, just savoring the smell of her skin and the tiny licks of her tongue against his. Best of all, her breath wasn't offensive in the least. It was like herbs and warm honey.

He brushed his knuckles against his lips in reverie and pressed his palm over her shin, wrapping his fingers around the underside, and kept his gaze fixed on her. He didn't know what he'd have done if she had been worse off. He was still feeling the waves of calming relief easing his mind now that he'd found her well.

"You've also been a surprise to me. I disliked you at first. Thought you were the devil." She smiled softly, biting her lip and then releasing it.

"I'm still the devil, little mouse. That, you were not wrong about."

She shook her head. "No. You're different with me. If you were still treating me as you had at first, I'd be contemplating running off with Lane."

His brows stitched together tightly, and the ease on his face was gone. "Lane. Is he going to be a problem for us?"

"A problem? He's my friend."

"He's a friend who's smitten with you, and you just said you'd thought of running off with him. Are you also smitten with him?"

Y/n laughed and shook her head. "Heavens no! Never."

Harry did not laugh with her. "But you're close to one another. Has he ever tried to kiss you?"

She stopped chuckling and blinked at the king slowly. Was she to lie to him and say no? Certainly, he wouldn't take it well if she told him the truth. She'd seen him in his jealousy before and wasn't keen on another outburst from him.

Looking down at where he was now clutching her shin, she shook her head no but kept her lips pressed together. She was afraid that if she were to speak the lie, he'd see right through her.

Harry reached toward her chin and tilted her face up. "Look at me when you answer. Have you kissed him?"

She blinked harshly and inhaled through her nose as she shook her head again, but she couldn't lie when she was looking directly at him. "Just… Well… Once. He was drunk, and I only wanted him to stop asking, so I let him, but that was it. I never even thought of him like that… I—"

"Who else have you kissed other than me?"

"My Lord, I—"

"Harry." He interrupted. "In private, you will call me by my given name, unless you plan on running off with another man, then the cold formalities will do. So tell me. How many others have you kissed?"

"No one else. Just you. I can hardly even count Lane, it was gross."

He let go of her chin and stood up, stepping away, his back to her. "And did he do anything else to you? Touch you anywhere he shouldn't?"

"Of course not. You are the only one who's ever touched me where he shouldn't."

Harry turned to look at her. "Where I shouldn't? Are you the maker of the law now? To tell the king, your husband, that he shouldn't touch you?"

"We're not wed yet."

"I could wed you tonight if I so please. Do not forget who I am."

"How could I? You're the devil. Just like you said."

Harry let out an incredulous sigh and shook his head. "You're free to leave if you like. I'm sure you'd prefer Lane over the devil."

She crossed her legs together and sat up, glaring at him. "Your jealousy is risible when the whole kingdom knows of your past exploits. How many women before me did you lie with and kiss, and how many do you still take?"

She wasn't sure she was prepared to hear his answer. She was sure he'd been having his fun and would continue to.

Stepping back toward the bed, he narrowed his eyes at her and placed his palms down on the mattress. "Since you? None. I haven't."

"You didn't return to your room last night. I must assume you were in another woman's bed."

"I was in my office working. I slept there. I have taken no women since you have arrived, and before you, it matters not."

She wanted to believe that he had not been soothing his heathen nature with other women, but a man like Harry, the king, could do as he pleased, and Y/n would have no say in what he did when he was away from her.

"Then why should it matter that a boy once kissed me a long time ago? And I don't think I believe that you've been keeping your fiddle clean either."

He couldn't answer her first question without sounding like a pathetic sap, but he knew the answer was because he was, in fact, jealous. He thought that when he'd kissed her, he had been her first. Harry didn't know why he was feeling so sentimental about a little kiss, but he likened the feeling to someone having poked a sharp pin into his chest. Even her accusation left him stung in pain.

"I might be the devil to you, but your accusations of me are false. I have no interest in anyone else in that way."

"But you could if you wanted. You're the all-powerful king. What's stopping you from rogering any other pretty girl who surely throws herself at your feet? Certainly, it isn't because of me."

Harry stood up, removing his hands from the mattress and stared at her in disbelief. He'd been accused of many things before, but somehow, having Y/n fault him with infidelity when he'd practically been a saint was absurd.

"Would you like me to go off and stick my fork into another woman? I have no interest in doing such a thing, but you seem quite fond of the idea."

She looked away from him. She wasn't sure why he cared or why she was provoking him. "I'm tired. I need rest."

"You didn't answer me earlier. Who else has been rude with you, Y/n? Tell me."

Crossing her arms over her chest, she sighed as she looked back at him. "The governess, the laundress, the dressmaker, some of the maids, the castle steward, the butler's servants, one of the footmen was particularly hateful when I was being dragged away into the cart—"

"Is your lady in waiting also hostile with you?"

She shook her head. "No. Phoebe's very kind. I think of her as a friend. Niall too, he's also very genial. I trust them both equally.

Harry looked down at the floor and worked the bottom part of his jaw from side to side. He hadn't realized that so many of his staff had been cruel to her. He expected some friction, but this? He lifted his gaze back up to hers. "Why haven't you told me?"

"Did you not already imagine I'd be treated with such disdain? No one wants me here in the castle… Well, most don't. I represent everything they hate."

"I suppose I was mistaken in thinking that even if they disliked you, they wouldn't outright scorn you. Even the governess?" He shook his head and placed his hand on the wooden poster of the bed.

"I've tried everything with her. I meet with her on time for every class. I'm polite, quiet, and I always practice what she's shown me. But I've come to accept that she thinks she's wasting her time with me… that I'm not worth the trouble. She never looks at me. Only speaks with her back turned, and then half the class acts like I don't exist. Most of the hour is spent looking at a wall while she reads. One time, I arrived early and she wasn't there. When she finally stepped into the room, it was half past and she never once looked at me or spoke, even when I asked her what she'd be teaching me that day."

"Do not indulge her anymore. You needn't put yourself through that kind of turmoil for a class that teaches useless politesse."

"I won't. I told her today that I wouldn't return."

"Good. And how are your parents faring?"

Y/n smiled, confused and a little astounded by the sudden change of subject as well as the shift in his mood. "They are very happy. I think they, too, are treated poorly, but they ignore it because they're so strong-headed. The beds and the food are quite enough to keep their mouths shut about ill treatment."

She watched as he traced his fingers over the thin stuffed mattress she sat on. "As soon as you are given your title, anyone who treats your family badly will be punished for it."

Y/n nodded and looked down at the brooch in her hand, running her thumb along the engraving. The small thing was heavier than it looked. She was glad to have it back, mostly so that it wasn't lost. She knew it meant a lot to Harry because it was once his mother's.

"She didn't have a chance to wear it but a handful of times," he said, looking at the breastpin. "They were going to bury it with her, but I stole it." He smiled at the memory as he traced his finger along the edge of the blanket near her thigh. "It was sitting in a tin tray with her other valuable jewels, and after I took it, my father tore the castle apart to try and find it. No one ever suspected it was me. Had hidden it for many years, then took it with me to war. No one ever knew."

Y/n looked up at him. She wasn't surprised that he'd stolen it as a child, and somehow it made him seem so much more human. He was just a small boy when he lost his mother. He deserved to have a piece of her to take with him.

"So you've always had a rebellious heart."

He licked his lips and looked down at her. "Yes. I suppose I have."

"Do you miss her?"

Stress lines carved into his forehead. "Not anymore. I still think of her, though. Fond memories… I came to terms with all that a long time ago."

"You're a very strong person."

"Strong? Maybe. Most everything is a farce, Y/n. I prefer the appearance of stoicism, so that's what I allow everyone to see. It's better to keep emotion out of reach."

"Does that mean you don't allow yourself to feel sad or happy?"

"I don't allow others to see it. That does not mean I don't feel those things. I do, however, prefer to remain rational. I let logic rule, not my emotions."

"But you are making significant changes by rejecting convention. You are causing tumult in the kingdom, and people are outraged. How is it that you are ruling by logic when you've created such a stir amongst the people?"

Harry sighed and sat down next to her, his eyes reaching from her face down to the brooch in her hand. "Do you believe that my actions speak of a man governed by his irrational feelings?"

"Some people think you're acting rashly. But to me, I find your plight noble. The poors are always overlooked. We fend for ourselves the best we can, but now to have the king on our side feels like our voice has finally been heard. Emotional or rational thinking, I don't know. But it's not without good virtue or mindful discernment."

"Mindful discernment." He smiled as he returned his gaze to hers. "I suppose I do have a soft spot for the undervalued among us. Even if it began as a means to an end."

Y/n let the words sink into her pores. She knew all along that he chose her to upset people. She wasn't delusive. Even if he'd started being nicer on occasion, she was still but a means to an end for him. But he was also a means to an end for her as well. She and her family could live comfortably, well fed, well rested, safe… Maybe true love had not been meant for her like she once imagined.

"Well, I'm certainly glad you saw me that day. Otherwise, I'd just be another undervalued, begging strangers for any kindness. At least I have a comfortable bed to lie down in." Yn laughed and closed her fingers around the brooch. "My mother thinks you courted me. I don't know why she'd believe a king would be interested in a street beggar, but I won't correct her. She still believes in true love and fate and all that. Don't have the heart to tell her how it happened. That you selected me out of convenience. A means to an end, if you will."

Harry's brows pulled together. "Is that what you think? That this is all just a show?"

"Is it not?"

"You will be crowned Queen, and you will be my wife, with whom I will produce an heir. That is not a show."

"Maybe not a show. But you said it yourself, a means to an end."

"What were you expecting, Y/n? Love at first sight? Anyone I would have selected would have been the same. But I did not anticipate to find you so alluring. I've grown very fond of you in these weeks."

She swallowed as her skin burned hot. It was most infuriating to her that he could sway her emotions so rapidly. In one beat, she was a disappointing burden, and yet in another, she was fond and alluring.

Even as she sat there, the thin fabric of her chemise covering most of her skin, while she bled into the mattress below her, he meant his words just the same. She was more beautiful and captivating by the day. Lifting his hand up to the curve of her jaw, he let his pupils wander over the features of her face, and he could tell she was nervous.

"What is it, mouse?" he asked in a soft timbre.

She blinked her eyes and looked back up at him, her mouth parted as she paused for a moment to let her irises mesh with his. "Sometimes you're confusing to me. I don't know how to feel when you speak about me. I know you don't love me. I never expected that from you. But I don't think I imagined you'd find me alluring either. Especially right now while I'm painting the mattress under me in red."

He slid his thumb over her cheekbone as he pushed out a breathy laugh.

"Is what I said laughable to you?" she asked, her brow raised.

He grinned. "Yes, your words amuse me. You're quick-witted. Do you think that because you're having your mensus that I would recoil in disgust?"

She nodded. "Yes, in fact. Even my father is repulsed, and he loves me."

Harry shook his head, and she watched his gaze drag down to her bare ankles and then back up to her face. It was almost lewd the way he so brazenly wiped his sight over her frame the way he had. She might as well have been lying there naked.

"I'm not squeamish by a little blood, Y/n. I've sewn limbs and gashed wounds together. I've used my bare hands to stop the bleeding of maimed soldiers more times than I care to count. I saw the most ghastly things when I was leading our royal army not that long ago. Your mensus does not unnerve me in the slightest."

"I see. But even still, it isn't desirable. You cannot tell me you find me alluring in this moment."

"And why not? You are not less beautiful or mouthy because of it. It does not deter my fondness." He grinned.

She had a hard time believing him. But why would he lie to her? He had no reason to try and make her feel better about herself because either way, she wasn't going anywhere.

"Even when I offered myself to you the morning before, you didn't want me, and I wasn't yet bleeding. How can you say these things to me now?"

Harry shifted, his knee pushed into her thigh as he took her face in his hands. "What are you on about? I made it clear my feelings about that. And then I kissed you. Do you not remember any of it?"

Her lashes fluttered as she tried to maintain calm. Of course, she remembered it all. Word for word. And then the kiss… Every brush of his lips and tongue, the way her body washed in heat every time she relived the kiss in her mind. It had changed a part of her, so of course, she hadn't forgotten.

"I remember."

He nodded and let go of her cheeks. She remembered, but did she remember it the way he did? Had he been alone in the way his heart pounded wildly behind his chest, in the way his fingertips burned, and his blood simmered… The way he was breathless when he finally pulled away? For that had never happened to him before, and it marked him so violently that he couldn't think straight all night.

And it had just been a kiss. Was he a fool to let the feel of her warm mouth against his take up so much space in his chest as he had? Even then, he'd wanted to kiss her again to revel in the sensation.

"I can't stop thinking about it. The kiss…" she confessed.

He looked back up at her face, relieved at her words but stricken by his shameful inner thoughts. He couldn't help but feel a kindred madness working its way through his veins.

"Nor can I," Harry replied quietly, almost reluctantly, like an admission passed between the cracks of armour. “The kiss, I can still feel it sitting on my lips.”

His thumb skimmed her bottom lip, light as breath, his eyes fixed there. "The moment I felt your mouth on mine, I knew it was something that would stay with me.” He paused. “And I found myself imagining it over and over.”

Y/n sat still, afraid to breathe too loudly, her heart fluttering rapidly like a mouse, the pulse pumping in her neck.

Harry’s voice dropped lower. “It lingers. The feeling of you. I wasn't prepared to let it sink me to the depths.”

She shivered, her nerves causing her skin to prick, as his words lay gently over her heart. "But you left so quickly after and didn't return to me last night. I know you said you were working, but you made your choice to keep away from me."

“Because I didn’t trust myself last night.” His hand slid to the side of her neck, his thumb pressing lightly into the hollow of her throat. “You offered yourself to me, and I was feeling reckless things. I have spent a lifetime reining in heedless actions. Staying away was best for us both.”

She boldly slid her shaky hand against his leg as his gaze lifted sharply to hers. He hadn't expected it, and in that brief moment, a recognition passed between them; they were two people, human and flawed, no different than the other. Their outward status meant nothing in those seconds that ticked by.

He leaned forward slowly, his nose brushing against hers. “You drive me mad.”

She smiled gently, their lips nearly touching. “You deserve it.”

That earned a brief breath of a laugh from him, more air than sound. And then, before reason could interrupt, before obligation, or her own festering doubts could rise to interfere, Harry kissed her.

It was not like the first time. This one felt impatient, a test of sanity or madness, a sating of curiosity. It was filled with a slow ache that had been building since their first clash of wills. His mouth moved over hers with devastating precision until she pressed her tongue to his, and the precision turned into a starved pace, as though every second he didn’t kiss her was one he could no longer justify.

Y/n’s fingers crept up his hard, solid chest, curling into the soft linen of his shirt as she responded, matching his hunger with a keenness of her own. Her body ached with a desperate need to be touched, to know she mattered to him.

And Harry touched her like she did matter. As if the truth he couldn’t yet speak was being carved into the space between them. His lips opened and closed around hers, his fingers slid gently up her spine to the back of her neck as she moaned into his mouth.

A harsh knock on the door startled them. The king slowly parted from her and turned toward the door. "Who's there?"

Y/n sat forward to watch the door open, and in stepped Harry's assistant, hands clasped behind his back, head lowered. "Your majesty. Forgive my intrusion, but your presence is requested. The Lord Mayor and His Grace, Duke Hughes are here to settle a dispute."

"Send them away. It's far too late to be resolving conflicts, and I have nothing more to say to the Lord Mayor today."

The man nodded shallowly as he kept his eyes turned to the floor. "He said that if you refuse to meet with him, he will report you for theft, assault, and trespassing."

Harry laughed and ran a finger under his nose. "That spineless worm. Fine. Tell him to make himself comfortable in the drawing room. I'll come find him soon."

"Of course, Your Majesty," Fred said as he closed the door behind himself.

Harry moved his hand from hers and fixed his gaze on her pretty eyes. “You should rest.”

“I won’t be able to,” she murmured. “Not after that.”

“After the kiss or the intrusion?"

She smiled shyly and looked down at her lap. "The kiss."

Harry nudged her chin upward to look at him. "Then think of it as a dream.”

She looked at him as he pulled away, her voice barely above a hush. “Did you feel reckless again?”

His soft green eyes scanned hers for a quiet moment. Then, with a final kiss to her brow, he answered, “Maybe.”

With that, he stood, smoothing the front of his waistcoat, his mask of control slowly knitting itself back over his face — but not before she caught the softness still lingering at the corners of his mouth.

“I'll be around to check on you, but I'd better find you fast asleep when I return. And I’ll see to the governess tomorrow.”

He made for the door, and just before exiting, he glanced over his shoulder with a glint of something playful in his eyes. “Rest, little mouse. The devil’s watching over you tonight.”

She pushed a breathy laugh from her lips and watched the edge of his mouth turn upward before he left her alone in her room. The silence around her felt stiff and accusatory, but she quelled the burgeoning shame and guilt that started to rise up in her. Y/n was done with needless worrying about wanting to kiss a handsome man who would soon be her husband. She touched her lips softly, the feel of his mouth engraved on hers.

Perhaps he was the devil but she was beginning to see that maybe the devil wasn't as bad as everyone had said.

. .

NEXT

. .

Feedback/Thoughts | Patreon

Thank you for reading! I appreciate any support so remember to comment, reblog, & like 💕

Tags: @matildasatellite @stylesftcher @hinnyrx @eversincehs1 @sunshinemoonsposts

@whoreonmondays @archerxnn @daphnesutton @spinninc @haliastyless

@multiplefandomstan @bruhk @sassamanda77 @cherryshouse @montgomery-929496

@badgalbell3 @practistyles @matildalittlefreak @imaginexxharry @yousunshineyoutempter

@tenaciousperfectionunknown @swiftmendeshoran @tiaamberxx @closureesny @angelbabyyy99

@malwtilda @itjustkindahappenedreally @onlyangellucifer @harryistheonlyoneforme @butdaddyilovehim-hs

@lc-fics @hannahdressedasabanana @babegoalsreads @harrrrystylesslut @elidoho

@gotdrxnkonu @cathy-1997 @imgonnadreamaboutthewayyoutaaaa @angeldavis777 @lillefroe

@monicaalexandraaa @hsonlyangelxo @brittanyzelazno @caynonmoondreams @mellamolayla

@ladscarlett @heartateasee @littlenatilda @michellekstyles @harrysredroom

*If you asked to be on the mean king!harry taglist and don't see your username I may have removed you bc you didn't interact with any of the posts - my tags are maxxed out. If you want to be on a taglist please let me know and interact with the post (like, comment, reblog). xoxo

#harry styles#king!harry#harry styles smut#harry styles fanfic#x reader#harry styles x reader#royalty#royal au#mean king!harry#firstpost#harry styles fanfiction#harry styles one shot#harry styles writing#harry styles fic#harry styles series#harry styles fiction#harry styles fan fic#harry styles concept#harry styles x yn#innocent!reader#harry styles imagine#harry styles fluff#one direction#harry edward styles#harrystyles#harry smut#harry#harry x reader#harry x yn#niall horan

709 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events In The History And Of The Life Of Elvis Presley Today On The 8th Of April In 1972.

ELVIS PRESLEY ARRIVES AT MGHEE TYSON AIRPORT IN KNOXVILLE TENNESSEE TO PLAY TWO PERFORMANCES SHOWS CONCERTS.

Elvis Presley braved the cold winds, and descended the steps onto the tarmac, followed immediately by his father Vernon Presley. Lois Thomas wrote an article the following day, April 9th In 1972 titled: “Gyrations Now look rather like Karate Moves Elvis Presley thrills Ex-teen-agers and Youths”, which referred to Elvis’ Presleys arrival at the airport, “Security unusual, security was tighter for Elvis Presley during his visit here than for any Presidents, Kings or other officials who have visited Knoxville in recent years”. A News-Sentinel reporter (Jan Maxwell), and photographer (Dave Carter) were first told they would not be allowed near the Lear Jet bringing Elvis Presley to Knoxville when it arrived. Later, arrangements were made to allow a photographer to meet Elvis Presley However, no fuss was made when a reporter accompanied the photographer to greet Elvis Presley Reporter Jan Maxwell (Avent) described Elvis’s Presley’s attire in her article published the following day: “The singing star was dressed in a wine-colored suede leather outfit with a knee length coat and matching pants. He wore a pair of modern sunglasses”. Maxwell witnessed the scene at the airport as the fans were held back from meeting their idol as she wrote: “Fans not allowed Past Gate – screaming fans were not allowed past the gate of the ramp – only a handful of persons were allowed by Presleys officials to meet the plane, including the Mayor’s wife, and a News-Sentinel photographer and reporter”. Rare Candid Photo Of Elvis Presley Here Taken By Sentinel Reporter’s Photographer Dave Carter Of Elvis Presley Wearing The Long Wine Suede Coat And Rare Candid Of Elvis Presley Also By Dave Carter Sentinel Reporter At Is Knoxville Tennessee Show And Concert Wearing the Light Blue Nail Jumpsuit And The Matching Cape And The White Chained Belt.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Más allá de la Movida

Cuando pensamos en los movimientos artísticos españoles surgidos tras la dictadura franquista, la Movida Madrileña suele ocupar un lugar central en el discurso. Sin embargo, el país, con su diversidad y riqueza creativa, también fue hogar de otras transformaciones previas, menos mencionadas, pero profundamente originales e interesantes. Entre ellas, en Andalucía, destacaron la revolución de Torremolinos y el rock andaluz, dos fenómenos que desafiaron las normas y lo establecido.

Durante los años 60 y principios de los 70, en plena dictadura, Torremolinos se convirtió en un lugar clave para la transgresión. Este enclave costero de Málaga atrajo a una comunidad diversa de artistas, músicos, turistas y curiosos, convirtiéndose en un referente de independencia. La presencia de bases militares estadounidenses en la zona trajo influencias musicales, corrientes y divisas extranjeras, lo que llevó al régimen franquista a hacer la vista gorda en este rincón.

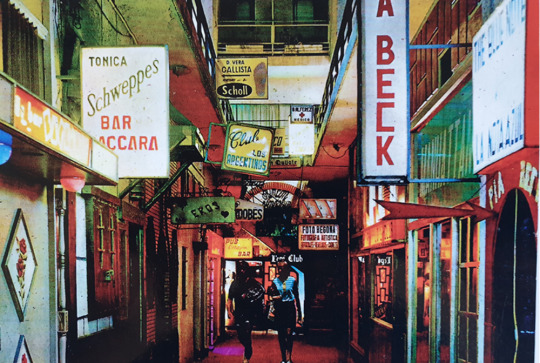

El Pasaje Begoña se convirtió en el epicentro de esta revolución. Este estrecho callejón albergaba bares y discotecas donde se respiraba una libertad impensable en el resto de España. Además de artistas y figuras internacionales como Brian Jones, guitarrista de los Rolling Stones, y Amanda Lear, musa de Dalí, el Pasaje acogía un ambiente donde la comunidad homosexual encontró un espacio para expresarse y relacionarse con mayor libertad, algo excepcional en la España de la dictadura. Este entorno diverso inspiró a grupos locales como Los Íberos, pioneros en la fusión de sonidos pop y beat.

Algún tiempo después, y sin salir del sur de España, nacía una revolución musical diferente: el rock andaluz. Este movimiento, que surgió en los años 70, ofreció una fusión única entre el flamenco tradicional y estilos como el rock progresivo, la psicodelia y el jazz. Más que un género, el rock andaluz fue una reinterpretación de las raíces flamencas desde una perspectiva contemporánea, conectándolas con las corrientes internacionales.

Bandas como Smash, liderada por Gualberto García, rompieron moldes al combinar las guitarras eléctricas con la esencia del flamenco. Por su parte, Triana, con Jesús de la Rosa al frente, consolidó este movimiento con temas como En el lago o Abre la puerta, que se convirtieron en himnos generacionales. También destacaron figuras como Silvio Fernández Melgarejo, un artista irreverente que mezcló rockabilly, flamenco y letras llenas de humor y poesía.

Aunque la Movida Madrileña es el fenómeno más citado, la creatividad y valentía que florecieron en Andalucía, con movimientos como la revolución de Torremolinos y el rock andaluz, evidencian que la transformación en España fue mucho más amplia y diversa.

Postal nocturna del emblemático Pasaje Begoña, cortesía del Ayuntamiento de Torremolinos.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have brought the 100 Classic Book Collection DS game. (It was £1 and had a few book I wanted to read on it so decided why not?) Here is the list of books that it includes. Can people convince me to read some of the other books that are on there.

I have read | I want to read | 🦝 I have the physical copy to

🦝 Little Women - Louisa May Alcott

Emma - Jane Austen

Mansfield Park - Jane Austen

Persuasion - Jane Austen

Pride and Prejudice - Jane Austen

Sense and Sensibility - Jane Austen

Lorna Doone - R. D. Blackmore

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall - Anne Brontë

Jane Eyre - Charlotte Brontë

The Professor - Charlotte Brontë

Shirley - Charlotte Brontë

Villette - Charlotte Brontë

Wuthering Heights - Emily Brontë

The Pilgrim's Progress - John Bunyan

Little Lord Fauntleroy - Frances Hodgson Burnett

🦝 The Secret Garden - Frances Hodgson Burnett

🦝 Alice's Adventures in Wonderland - Lewis Carroll

Through the Looking-Glass - Lewis Carroll

The Moonstone - Wilkie Collins

The Woman in White - Wilkie Collins

🦝 The Adventures of Pinocchio - Carlo Collodi

Lord Jim - Joseph Conrad

What Katy Did - Susan Coolidge

The Last of the Mohicans - James Fenimore Cooper

🦝 Robinson Crusoe - Daniel Defoe

Barnaby Rudge - Charles Dickens

Bleak House - Charles Dickens

🦝 A Christmas Carol - Charles Dickens

David Copperfield - Charles Dickens

Dombey and Son - Charles Dickens

Great Expectations - Charles Dickens

Hard Times - Charles Dickens

Martin Chuzzlewit - Charles Dickens

Nicholas Nickleby - Charles Dickens

The Old Curiosity Shop - Charles Dickens

Oliver Twist - Charles Dickens

The Pickwick Papers - Charles Dickens

A Tale of Two Cities - Charles Dickens

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes - Arthur Conan Doyle

The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes - Arthur Conan Doyle

The Count of Monte Cristo - Alexandre Dumas

The Three Musketeers - Alexandre Dumas

Adam Bede - George Eliot

Middlemarch - George Eliot

The Mill on the Floss - George Eliot

King Solomon's Mines - H. Rider Haggard

Far from the Madding Crowd - Thomas Hardy

The Mayor of Casterbridge - Thomas Hardy

Tess of the d'Urbervilles - Thomas Hardy

Under the Greenwood Tree - Thomas Hardy

The Scarlet Letter - Nathaniel Hawthorne

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame - Victor Hugo

Les Misérables - Victor Hugo

The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. - Washington Irving

Westward Ho! - Charles Kingsley

Sons and Lovers - D. H. Lawrence

The Phantom Of The Opera - Gaston Leroux

The Call of the Wild - Jack London

White Fang - Jack London

Moby-Dick - Herman Melville

Tales of Mystery & Imagination - Edgar Allan Poe

Ivanhoe - Walter Scott

Rob Roy - Walter Scott

Waverley - Walter Scott

🦝 Black Beauty - Anna Sewell

All's Well That Ends Well - William Shakespeare

Antony and Cleopatra - William Shakespeare

As You Like It - William Shakespeare

The Comedy of Errors - William Shakespeare

Hamlet - William Shakespeare

Henry V - William Shakespeare

Julius Caesar - William Shakespeare

King Lear - William Shakespeare

Love's Labour's Lost - William Shakespeare

Macbeth - William Shakespeare

The Merchant of Venice - William Shakespeare

A Midsummer Night's Dream - William Shakespeare

Much Ado About Nothing - William Shakespeare

Othello - William Shakespeare

Richard III - William Shakespeare

Romeo and Juliet - William Shakespeare

The Taming of the Shrew - William Shakespeare

The Tempest - William Shakespeare

Timon of Athens - William Shakespeare

Titus Andronicus - William Shakespeare

Twelfth Night - William Shakespeare

The Winter's Tale - William Shakespeare

🦝 Kidnapped - Robert Louis Stevenson

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde - Robert Louis Stevenson

🦝 Treasure Island - Robert Louis Stevenson

Uncle Tom's Cabin - Harriet Beecher Stowe

🦝 Gulliver's Travels - Jonathan Swift

Vanity Fair William - Makepeace Thackeray

Barchester Towers - Anthony Trollope

🦝 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn - Mark Twain

🦝 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer - Mark Twain

Around the World in Eighty Days - Jules Verne

🦝 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea - Jules Verne

The Importance of Being Earnest - Oscar Wilde

The Picture of Dorian Gray - Oscar Wilde

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Shakespeare, Shakespeare also spelled Shakspere, byname Bard of Avon or Swan of Avon, (baptized April 26, 1564, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England—died April 23, 1616, Stratford-upon-Avon), English poet, dramatist, and actor often called the English national poet and considered by many to be the greatest dramatist of all time.

Shakespeare occupies a position unique in world literature. Other poets, such as Homer and Dante, and novelists, such as Leo Tolstoy and Charles Dickens, have transcended national barriers, but no writer’s living reputation can compare to that of Shakespeare, whose plays, written in the late 16th and early 17th centuries for a small repertory theatre, are now performed and read more often and in more countries than ever before. The prophecy of his great contemporary, the poet and dramatist Ben Jonson, that Shakespeare “was not of an age, but for all time,” has been fulfilled.

William Shakespeare

Category: Arts & Culture

Baptized: April 26, 1564 Stratford-upon-Avon England

Died: April 23, 1616 Stratford-upon-Avon England

Notable Works: “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” “All’s Well That Ends Well” “Antony and Cleopatra” “As You Like It” “Coriolanus” “Cymbeline” First Folio “Hamlet” “Henry IV, Part 1” “Henry IV, Part 2” “Henry V” “Henry VI, Part 1” “Henry VI, Part 2” “Henry VI, Part 3” “Henry VIII” “Julius Caesar” “King John” “King Lear” “Love’s Labour’s Lost” “Macbeth” “Measure for Measure” “Much Ado About Nothing” “Othello” “Pericles” “Richard III” “The Comedy of Errors” “The Merchant of Venice” “The Merry Wives of Windsor” “The Taming of the Shrew” “The Tempest” “Timon of Athens”

Movement / Style: Jacobean age

Notable Family Members: spouse Anne Hathaway

It may be audacious even to attempt a definition of his greatness, but it is not so difficult to describe the gifts that enabled him to create imaginative visions of pathos and mirth that, whether read or witnessed in the theatre, fill the mind and linger there. He is a writer of great intellectual rapidity, perceptiveness, and poetic power. Other writers have had these qualities, but with Shakespeare the keenness of mind was applied not to abstruse or remote subjects but to human beings and their complete range of emotions and conflicts. Other writers have applied their keenness of mind in this way, but Shakespeare is astonishingly clever with words and images, so that his mental energy, when applied to intelligible human situations, finds full and memorable expression, convincing and imaginatively stimulating. As if this were not enough, the art form into which his creative energies went was not remote and bookish but involved the vivid stage impersonation of human beings, commanding sympathy and inviting vicarious participation. Thus, Shakespeare’s merits can survive translation into other languages and into cultures remote from that of Elizabethan England.

Shakespeare the man

Life

Although the amount of factual knowledge available about Shakespeare is surprisingly large for one of his station in life, many find it a little disappointing, for it is mostly gleaned from documents of an official character. Dates of baptisms, marriages, deaths, and burials; wills, conveyances, legal processes, and payments by the court—these are the dusty details. There are, however, many contemporary allusions to him as a writer, and these add a reasonable amount of flesh and blood to the biographical skeleton.

Shakespeare Reading, oil on canvas by William Page, 1873-74; in the collection of the Smithsonian American Museum of Art, Washington, D.C. (William Shakespeare)

Shakespeare's birthplace

The parish register of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, shows that he was baptized there on April 26, 1564; his birthday is traditionally celebrated on April 23. His father, John Shakespeare, was a burgess of the borough, who in 1565 was chosen an alderman and in 1568 bailiff (the position corresponding to mayor, before the grant of a further charter to Stratford in 1664). He was engaged in various kinds of trade and appears to have suffered some fluctuations in prosperity. His wife, Mary Arden, of Wilmcote, Warwickshire, came from an ancient family and was the heiress to some land. (Given the somewhat rigid social distinctions of the 16th century, this marriage must have been a step up the social scale for John Shakespeare.)

Stratford enjoyed a grammar school of good quality, and the education there was free, the schoolmaster’s salary being paid by the borough. No lists of the pupils who were at the school in the 16th century have survived, but it would be absurd to suppose the bailiff of the town did not send his son there. The boy’s education would consist mostly of Latin studies—learning to read, write, and speak the language fairly well and studying some of the Classical historians, moralists, and poets. Shakespeare did not go on to the university, and indeed it is unlikely that the scholarly round of logic, rhetoric, and other studies then followed there would have interested him.

Instead, at age 18 he married. Where and exactly when are not known, but the episcopal registry at Worcester preserves a bond dated November 28, 1582, and executed by two yeomen of Stratford, named Sandells and Richardson, as a security to the bishop for the issue of a license for the marriage of William Shakespeare and “Anne Hathaway of Stratford,” upon the consent of her friends and upon once asking of the banns. (Anne died in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare. There is good evidence to associate her with a family of Hathaways who inhabited a beautiful farmhouse, now much visited, 2 miles [3.2 km] from Stratford.) The next date of interest is found in the records of the Stratford church, where a daughter, named Susanna, born to William Shakespeare, was baptized on May 26, 1583. On February 2, 1585, twins were baptized, Hamnet and Judith. (Hamnet, Shakespeare’s only son, died 11 years later.)

How Shakespeare spent the next eight years or so, until his name begins to appear in London theatre records, is not known. There are stories—given currency long after his death—of stealing deer and getting into trouble with a local magnate, Sir Thomas Lucy of Charlecote, near Stratford; of earning his living as a schoolmaster in the country; of going to London and gaining entry to the world of theatre by minding the horses of theatregoers. It has also been conjectured that Shakespeare spent some time as a member of a great household and that he was a soldier, perhaps in the Low Countries. In lieu of external evidence, such extrapolations about Shakespeare’s life have often been made from the internal “evidence” of his writings. But this method is unsatisfactory: one cannot conclude, for example, from his allusions to the law that Shakespeare was a lawyer, for he was clearly a writer who without difficulty could get whatever knowledge he needed for the composition of his plays.

Career in the theatre of William Shakespeare

The first reference to Shakespeare in the literary world of London comes in 1592, when a fellow dramatist, Robert Greene, declared in a pamphlet written on his deathbed:

There is an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers heart wrapt in a Players hide supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you; and, being an absolute Johannes Factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country.

What these words mean is difficult to determine, but clearly they are insulting, and clearly Shakespeare is the object of the sarcasms. When the book in which they appear (Greenes, groats-worth of witte, bought with a million of Repentance, 1592) was published after Greene’s death, a mutual acquaintance wrote a preface offering an apology to Shakespeare and testifying to his worth. This preface also indicates that Shakespeare was by then making important friends. For, although the puritanical city of London was generally hostile to the theatre, many of the nobility were good patrons of the drama and friends of the actors. Shakespeare seems to have attracted the attention of the young Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd earl of Southampton, and to this nobleman were dedicated his first published poems, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

One striking piece of evidence that Shakespeare began to prosper early and tried to retrieve the family’s fortunes and establish its gentility is the fact that a coat of arms was granted to John Shakespeare in 1596. Rough drafts of this grant have been preserved in the College of Arms, London, though the final document, which must have been handed to the Shakespeares, has not survived. Almost certainly William himself took the initiative and paid the fees. The coat of arms appears on Shakespeare’s monument (constructed before 1623) in the Stratford church. Equally interesting as evidence of Shakespeare’s worldly success was his purchase in 1597 of New Place, a large house in Stratford, which he as a boy must have passed every day in walking to school.

Globe Theatre

How his career in the theatre began is unclear, but from roughly 1594 onward he was an important member of the Lord Chamberlain’s company of players (called the King’s Men after the accession of James I in 1603). They had the best actor, Richard Burbage; they had the best theatre, the Globe (finished by the autumn of 1599); they had the best dramatist, Shakespeare. It is no wonder that the company prospered. Shakespeare became a full-time professional man of his own theatre, sharing in a cooperative enterprise and intimately concerned with the financial success of the plays he wrote.

Unfortunately, written records give little indication of the way in which Shakespeare’s professional life molded his marvelous artistry. All that can be deduced is that for 20 years Shakespeare devoted himself assiduously to his art, writing more than a million words of poetic drama of the highest quality.

Private life

Shakespeare's house in Stratford-upon-Avon

Shakespeare had little contact with officialdom, apart from walking—dressed in the royal livery as a member of the King’s Men—at the coronation of King James I in 1604. He continued to look after his financial interests. He bought properties in London and in Stratford. In 1605 he purchased a share (about one-fifth) of the Stratford tithes—a fact that explains why he was eventually buried in the chancel of its parish church. For some time he lodged with a French Huguenot family called Mountjoy, who lived near St. Olave’s Church in Cripplegate, London. The records of a lawsuit in May 1612, resulting from a Mountjoy family quarrel, show Shakespeare as giving evidence in a genial way (though unable to remember certain important facts that would have decided the case) and as interesting himself generally in the family’s affairs.

No letters written by Shakespeare have survived, but a private letter to him happened to get caught up with some official transactions of the town of Stratford and so has been preserved in the borough archives. It was written by one Richard Quiney and addressed by him from the Bell Inn in Carter Lane, London, whither he had gone from Stratford on business. On one side of the paper is inscribed: “To my loving good friend and countryman, Mr. Wm. Shakespeare, deliver these.” Apparently Quiney thought his fellow Stratfordian a person to whom he could apply for the loan of £30—a large sum in Elizabethan times. Nothing further is known about the transaction, but, because so few opportunities of seeing into Shakespeare’s private life present themselves, this begging letter becomes a touching document. It is of some interest, moreover, that 18 years later Quiney’s son Thomas became the husband of Judith, Shakespeare’s second daughter.

Shakespeare’s will (made on March 25, 1616) is a long and detailed document. It entailed his quite ample property on the male heirs of his elder daughter, Susanna. (Both his daughters were then married, one to the aforementioned Thomas Quiney and the other to John Hall, a respected physician of Stratford.) As an afterthought, he bequeathed his “second-best bed” to his wife; no one can be certain what this notorious legacy means. The testator’s signatures to the will are apparently in a shaky hand. Perhaps Shakespeare was already ill. He died on April 23, 1616. No name was inscribed on his gravestone in the chancel of the parish church of Stratford-upon-Avon. Instead these lines, possibly his own, appeared:

Sexuality of William Shakespeare

Like so many circumstances of Shakespeare’s personal life, the question of his sexual nature is shrouded in uncertainty. At age 18, in 1582, he married Anne Hathaway, a woman who was eight years older than he. Their first child, Susanna, was born on May 26, 1583, about six months after the marriage ceremony. A license had been issued for the marriage on November 27, 1582, with only one reading (instead of the usual three) of the banns, or announcement of the intent to marry in order to give any party the opportunity to raise any potential legal objections. This procedure and the swift arrival of the couple’s first child suggest that the pregnancy was unplanned, as it was certainly premarital. The marriage thus appears to have been a “shotgun” wedding. Anne gave birth some 21 months after the arrival of Susanna to twins, named Hamnet and Judith, who were christened on February 2, 1585. Thereafter William and Anne had no more children. They remained married until his death in 1616.

Were they compatible, or did William prefer to live apart from Anne for most of this time? When he moved to London at some point between 1585 and 1592, he did not take his family with him. Divorce was nearly impossible in this era. Were there medical or other reasons for the absence of any more children? Was he present in Stratford when Hamnet, his only son, died in 1596 at age 11? He bought a fine house for his family in Stratford and acquired real estate in the vicinity. He was eventually buried in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford, where Anne joined him in 1623. He seems to have retired to Stratford from London about 1612. He had lived apart from his wife and children, except presumably for occasional visits in the course of a very busy professional life, for at least two decades. His bequeathing in his last will and testament of his “second best bed” to Anne, with no further mention of her name in that document, has suggested to many scholars that the marriage was a disappointment necessitated by an unplanned pregnancy.

What was Shakespeare’s love life like during those decades in London, apart from his family? Knowledge on this subject is uncertain at best. According to an entry dated March 13, 1602, in the commonplace book of a law student named John Manningham, Shakespeare had a brief affair after he happened to overhear a female citizen at a performance of Richard III making an assignation with Richard Burbage, the leading actor of the acting company to which Shakespeare also belonged. Taking advantage of having overheard their conversation, Shakespeare allegedly hastened to the place where the assignation had been arranged, was “entertained” by the woman, and was “at his game” when Burbage showed up. When a message was brought that “Richard the Third” had arrived, Shakespeare is supposed to have “caused return to be made that William the Conqueror was before Richard the Third. Shakespeare’s name William.” This diary entry of Manningham’s must be regarded with much skepticism, since it is verified by no other evidence and since it may simply speak to the timeless truth that actors are regarded as free spirits and bohemians. Indeed, the story was so amusing that it was retold, embellished, and printed in Thomas Likes’s A General View of the Stage (1759) well before Manningham’s diary was discovered. It does at least suggest, at any rate, that Manningham imagined it to be true that Shakespeare was heterosexual and not averse to an occasional infidelity to his marriage vows. The film Shakespeare in Love (1998) plays amusedly with this idea in its purely fictional presentation of Shakespeare’s torchy affair with a young woman named Viola De Lesseps, who was eager to become a player in a professional acting company and who inspired Shakespeare in his writing of Romeo and Juliet—indeed, giving him some of his best lines.