#maryland state archives

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Special collections are archives-lite

Cleo, Akila, and Brian see the few items in the library's special collections room which are presented by Khensu in an episode of Cleopatra in Space

There are are specific parts of libraries which don't fit the usual distinctions between archives and libraries. One of those parts are special collections, which generally keep personal papers and rare books, including thesis written by alumni. Access to materials in said library sections is similar to than in archives, but can be managed by archivists or librarians. As such, special collections, just like historical societies and rare books, can be considered archives-lite. [1]

Reprinted from my Wading Through the Cultural Stacks WordPress blog. Originally published on June 15, 2022.

There are a few examples of this in series I've watched and have explained on this blog. One of the first examples is the special collections room of the PYRAMID library in an episode of Cleopatra in Space, holding holograms, documents, and other research materials, making it a repository of sorts. It is more than a mini-archives, but can be seen as operating "in a library-archives space of sorts" as I wrote at the time. More directly than this is the special collections room of the Trolberg library in Hilda. I described the importance of the room to the episode as a whole, writing:

She [Samantha Cross] begins by noting how Hilda and Twig, her deerfox, Twig, find a secret special collections room in the Trolberg library, a room which is only seen one time in the series. While she notes that as a result the room is only seen in this episode it "doesn't make a huge impact on the story as a whole...Hilda photocopies a page of the book that she was reading when the Librarian confronted her in the special collections room, intending to help her friend, David, and her mom...After Hilda enters the secret/hidden special collections room, it is literally underground...Assuming she does not put the book back in the special collections room, this means that the librarian will have to re-shelve this, hinting at the work she will do off-screen...Is this librarian a lone arranger of the special collections room? Or does she have volunteers, unpaid interns, or other staff helping her? It is my hope that this librarian has paid staff helping her...Frida expresses her surprise that the special collections room existed, making it clear it really is hidden...Sadly, the librarian doesn't have a role in any other episodes and neither does this special collections room...

I expanded on this in a post in January of last year, where the protagonists go back into the special collections room. They use it to begin a trek through various secret rooms until they come across the librarian, Kaisa, who ends up being a witch. In the case of Hilda and Cleopatra in Space, there is no doubt there was some level of appraisal even though it not shown directly in either series.

As such, it is clear, that libraries can have archives of sorts within them, and in some cases (like with the Maryland State Archives) libraries can exist within archives. This can help patrons, and even those working in the library, providing with secondary sources to give context to the primary sources within the archives themselves.

© 2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] Samantha Cross noted this on her blog in explaining the Springfield Historical Society in an episode of The Simpsons. Cross also writes about the importance of family records in an episode of Star Vs. The Forces of Evil, or the archives which revealed the truth in an episode of Justice League Legends, and the Hall of Records used by Lisa and Bart in an episode of The Simpsons.

#cleopatra in space#special collections#archivy#archival science#archival studies#archives#maryland state archives#the simpsons#star vs. the forces of evil#svtfoe#justice league of legends#hilda#records#record restrictions#restrictions

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

License Plate of the Day 0010

State: Maryland

Run: 2017?-present

Type: special interest

My Other Car is a Bicycle

The BN does not stand for anything in particular

One of the hundreds of organizational support license plates offered in Maryland. Costs $25 and must be a member of the organization to obtain, money collected does not go to the organization.

Image Credit

#hell yeah for biking hell no for not putting the date this thing was made anywhere on your website bike Maryland#if you know the date please let me know their questions form is down#I found a post mentioning it dating 2017 so it’s at least in 2017#I spent way too long researching this i went through bike marlylands entire news archive#anyways#license plate#vehicle license plate#license plate of the day#United States#maryland#2010’s#2020’s#dubious date#special interest

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things To Know To Get Your Vote Counted — Non-Exhaustive List

[Plain text: "Things To Know To Get Your Vote Counted — Non-Exhaustive List."]

Post date: October 28, 2024. Contains information relevant to both in-person and absentee voting.

Same Day Voter Registration:

[Same Day Voter Registration:]

If you're not already registered to vote, over 20 states (and DC) allow you to register while you're at the polling place on election day (or for early voting). If you're making a last-second decision to vote, or you thought you were registered but found out you weren't, these states give you options up until (insert time the polls close) on November 5th.

[ID: map with states shaded where same-day registration is allowed in 2024. States that allow it are: California, Colorado, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. (North Carolina only allows it during early voting.) End ID.] (Source: Ballotpedia)

Alaska and Rhode Island only allow same-day registering voters to vote for president/vice president. North Carolina only allows same-day registration in the early voting period. Most states require an ID and/or proof of residency to register as usual — the Ballotpedia page is a good starting point for researching requirements in your own state.

Casting a Provisional Ballot:

[Casting a Provisional Ballot:]

Provisional ballots are cast by voters who can't prove they are eligible to vote at the polling place on Election Day. For example, if you:

don't have a photo ID on you, but it's required in your state?

requested an ID ballot, but had to vote in person because you didn't receive it?

changed your name or address, but it doesn't show up in the registration information?

have your eligibility challenged by a poll worker for any reason?

Then you should ask for a provisional ballot. Moreover, federal law requires election officials to offer voters a way of tracking whether their vote was counted. Many states have online provisional ballot trackers.

Provisional ballots are used in all states except for Idaho and Minnesota. To learn more about your specific state, I recommend the National Conference of State Legislatures (archive link if the site is down).

Tracking Your Ballot and Curing Signatures:

[Tracking Your Ballot and Curing Signatures:]

In addition to provisional ballots, if you've submitted an absentee ballot, Vote.org compiles ballot trackers to ensure your ballot is received — the vast majority of states have an online version.

Moreover, if voting absentee, familiarize yourself with your state's cure period for signature errors, and be on the lookout for communication in case your signature is found not to match. 33 states require some kind of notification and ballot-curing process — which means that if your ballot is rejected, you have a chance to fix it, albeit most likely needing to appear in person.

Be Careful About Phones, Ballot Selfies, Political Clothing:

[Be Careful About Phones, Ballot Selfies, Political Clothing:]

Many states disallow taking pictures of your ballot, and even some of the states listed as "allowing" it only do so under specific conditions (ex: your face isn't in the photo, the photo isn't taken at the polling place, et cetera). Moreover, several states go even further, and ban phones at the polling place altogether. Nevada, Maryland, and Texas are the states I'm aware of, but there may be more.

Also, at least 21 states ban political apparel or buttons in polling places. Regarding both apparel and phones, it is also possible that cities could set their own rules, so you should err on the side of caution unless you know for a fact what's allowed and what isn't.

Responding to Voter Intimidation:

[Responding to Voter Intimidation:]

866-Our-Vote (866-687-8683) is a hotline you can contact, which will help connect you with lawyers and federal investigators. Their website also lists hotlines in Spanish, Arabic, and some East & Southeast Asian languages. If you witness or experience a civil rights violation, you should write down your account for future reference, contact the DOJ Civil Rights Division, and possibly also a local ACLU division.

Other Information:

[Other Information:]

Getting time off work to vote, state-by-state

State election department contact information

Vote411 (voting law information & candidate information)

If anyone notices an error or broken link in this post, please let me know so I can correct it. If anyone would like to add on information in the notes, please do so — especially if it's specific to your state! Please just include a source if possible, and present the information as accessibly as you can. Overall, good luck out there.

#politics#us politics#simply could not find a good 2024 post about this information that had both sources and image descriptions#so i made it myself

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved in our archive

There are an increasing number of states across the U.S. where "very high" levels of the virus that causes COVID-19 are present in wastewater.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Idaho, New Mexico and South Dakota all had "very high" levels of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in their wastewater during the week between November 17 and November 23, 2024.

The week prior, between November 10 and November 16, only New Mexico's wastewater had this level of the virus present.

Arizona, Arkansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts and New Hampshire currently have "high" levels of COVID-19, while "moderate" levels were detected in Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah and Wyoming.

(Follow link for interactive map!)

Nineteen states had "low" levels, while 14 states and D.C. had "minimal" levels of the SARS-CoV-2 virus present in wastewater.

Between November 10 and November 16, "high" levels were detected in Arizona, Kentucky, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and South Dakota, with "moderate" levels of the virus detected in Colorado, Idaho, Maine, Maryland, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah and Wyoming.

The data from New Hampshire, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and South Dakota all have limited coverage for the most current data, which means it is "based on a small segment (less than 5 percent) of the population and may not be representative of the state/territory," the CDC explains. Additionally, North Dakota has no data for this period.

The CDC monitors COVID-19 levels in wastewater as part of its surveillance strategy to track the spread of the virus in communities. Infected individuals shed the virus in their feces, meaning that monitoring wastewater can reveal increases in infection rates earlier than clinical testing or hospitalizations.

"The wastewater viral activity level indicates whether the amount of virus in the wastewater is minimal, low, moderate, high or very high. The wastewater viral activity levels may indicate the risk of infection in an area," the CDC said.

Wastewater data helps public health officials allocate resources and make informed decisions about mask and vaccination policies.

In the week ending November 23, about 4.5 percent of COVID-19 tests around the country came back positive. This represents a 0.3 percent increase from the week prior. Some regions had rates of up to 6.3 percent, such as Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas.

"SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is constantly changing and accumulating mutations in its genetic code over time. New variants of SARS-CoV-2 are expected to continue to emerge. Some variants will emerge and disappear, while others will emerge and continue to spread and may replace previous variants," the CDC said in a statement.

Subvariant KP.3.1.1 made up 37 percent of COVID-19 variants in U.S. wastewater over the two weeks before November 23. The new XEC variant made up 24 percent, KP.3 made up 17 percent, JN.1 made up 8 percent and "other" made up 14 percent.

For the same period, variants detected in positive test samples were slightly different, with KP.3.1.1 making up 44 percent of recorded COVID infections, XEC totaling 38 percent and MC.1 composing 6 percent.

#mask up#public health#wear a mask#pandemic#wear a respirator#covid#covid 19#still coviding#coronavirus#sars cov 2

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

The WAVES of Change: Women's Valiant Service in World War II 🌊

When the tides of World War II swelled, an unprecedented wave of women stepped forward to serve their country, becoming an integral part of the U.S. Navy through the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) program. This initiative not only marked a pivotal moment in military history but also set the stage for the transformation of women's roles in the armed forces and society at large. The WAVES program, initiated in 1942, was a beacon of change, showcasing the strength, skill, and patriotism of American women during a time of global turmoil.

The inception of WAVES was a response to the urgent need for additional military personnel during World War II. With many American men deployed overseas, the United States faced a shortage of skilled workers to support naval operations on the home front. The WAVES program was spearheaded by figures such as Lieutenant Commander Mildred H. McAfee, the first woman commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Navy. Under her leadership, WAVES members were trained in various specialties, including communications, intelligence, supply, medicine, and logistics, proving that women could perform with as much competence and dedication as their male counterparts.

The impact of the WAVES program extended far beyond the war effort. Throughout their service, WAVES members faced and overcame significant societal and institutional challenges. At the time, the idea of women serving in the military was met with skepticism and resistance; however, the exemplary service of the WAVES shattered stereotypes and demonstrated the invaluable contributions women could make in traditionally male-dominated fields. Their work during the war not only contributed significantly to the Allies' victory but also laid the groundwork for the integration of women into the regular armed forces.

The legacy of the WAVES program is a testament to the courage and determination of the women who served. Their contributions went largely unrecognized for many years, but the program's impact on military and gender norms has been profound. The WAVES paved the way for future generations of women in the military, demonstrating that service and sacrifice know no gender. Today, women serve in all branches of the U.S. military, in roles ranging from combat positions to high-ranking officers, thanks in no small part to the trail blazed by the WAVES.

The WAVES program was more than just a wartime necessity; it was a watershed moment in the history of women's rights and military service. The women of WAVES not only supported the United States during a critical period but also propelled forward the conversation about gender equality in the armed forces and beyond. Their legacy is a reminder of the strength and resilience of women who rise to the challenge, breaking barriers and making waves in pursuit of a better world.

Read more: https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2023/11/06/historic-staff-spotlight-eunice-whyte-navy-veteran-of-both-world-wars/

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

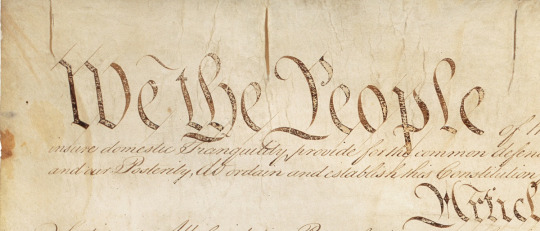

Happy Constitution Day!

Can’t make it to the National Archives Building in person? Check out the hi-res scans in our catalog:

Record Group 11: General Records of the United States Government Series: The Constitution of the United States

Image description: Zoomed-in portion of the first page of the U.S. Constitution, including the words “We the People.”

Transcription:

We the People of the United States in order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Article. I.

Section.1. All Legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

Section.2. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second year by the People of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.

No Person shall be a Representative who shall not have attained the Age of twenty-five Years, and been seven Years a Citizen of the United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an Inhabitant of that State in which he shall be chosen.

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. The actual Enumeration shall be be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut five, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland six, Virginia ten, North Carolina five, South Carolina five, and Georgia three.

When vacancies happen in the Representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Election to fill such Vacancies.

The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.

Section.3. The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, chosen by the Legislature thereof, for six Years; and each Senator shall have one Vote.

Immediately after they shall be assembled in Consequence of the first Election, they shall be divided as equally as may be into three Classes. The Seats of the Senators of the first Class shall be vacated at the Expiration of the second Year, of the second Class at the Expiration of the fourth Year, and of the third Class at the Expiration of the sixth Year, so that one third may be chosen every second Year; and if Vacancies happen by Resignation, or otherwise, during the Recess of the Legislature of any State, the Executive thereof may make temporary Appointments until the next Meeting of the Legislature, which shall then fill such Vacancies.

No Person shall be a Senator who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty Years, and been nine Years a Citizen of the United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an Inhabitant of that State for which he shall be chosen.

The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate, but shall have no Vote, unless they be equally divided.

The Senate shall chuse their other Officers, and also a President pro tempore, in the Absence of the Vice President, or when he shall exercise the Office of President of the United States.

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.

Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.

Section.4. The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.

The Congress shall assemble at least once in every Year, and such Meeting shall be on the first Monday in December, unless they shall by Law appoint a different Day.

Section.5. Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members, and a Majority of each shall constitute a Quorum to do Business; but a smaller Number may adjourn from day to day, and maybe authorized to compel the Attendance of absent Members, in such Manner, and under such Penalties as each House may provide.

Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly Behaviour, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.

Each House shall keep a Journal of its Proceedings, and from time to time publish the same, excepting such Parts as may in their Judgment require Secrecy; and the Yeas and Nays of the Members of either House on any question shall, at the Desire of one-fifth of those Present, be entered on the Journal.

Neither House, during the Session of Congress, shall, without the Consent of the other, adjourn for more than three days, nor to any other Place than that in which the two Houses shall be sitting.

Section.6. The Senators and Representatives shall receive a Compensation for their Services, to be ascertained by Law, and paid out of the Treasury of the United States. They shall in all Cases, except Treason, Felony and Breach of the Peace, be privileged from Arrest during their Attendance at the Session of their respective Houses, and in going to and returning from the same; and for any Speech or Debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other Place.

No Senator or Representative shall, during the Time for which he was elected, be appointed to any civil Office under the Authority of the United States, which shall have been created, or the Emoluments whereof shall have been increased during such time; and no Person holding any Office under the United States, shall be a Member of either House during his Continuance in Office.

Section.7. All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills.

Every Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it becomes a Law, be presented to the President of the

111 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Interview: Swiss Colonialism Exhibition

The National Museum Zurich recently opened a comprehensive and multi perspectival exhibition on Switzerland’s colonial past: Colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements. Based on the latest, original research and drawing on biographies, as well as using objects, artworks, photographs, and written documents for illustrative purposes, Colonial explores the vicissitudes of Swiss colonial history from the 1500s up to the present era. In this interview, James Blake Wiener speaks to co-curator Marina Amstad to learn more.

Maryland, Dutch East Indies

Swiss National Museum (CC BY-NC-SA)

JBW: Marina Amstad, thanks so much for speaking with me. I suspect that many museum visitors – like potential readers of this interview – may find the concept of “Swiss colonialism” to be puzzling given that Switzerland is renowned for its policy of neutrality and has never had any colonies of its own.

What was it then, which provided the impetus for a show on Swiss colonial history?

Marina Amstad: For a long time, Swiss history was seen only in terms of what happened on the territory of present-day Switzerland. Since the 16th century, however, Swiss society has become increasingly globally interconnected. There were numerous Swiss individuals who participated in the colonial system. On the one hand, the exhibition aims to show the areas of colonial activity in which the Swiss were involved. On the other hand, it shows that Swiss history is also global history.

JBW: Several Swiss companies and private individuals participated in the transatlantic slave trade and amassed fortunes from trading in colonial products and exploiting enslaved people.

How extensive was Swiss participation in the Triangular Trade (from the 16th to 19th century - a three-way trade system between Africa, Europe, and the Americas), and how did activities connected to the trade enrich Switzerland’s economy?

MA: Current research has identified more than 250 Swiss companies and private individuals who were involved in the trade and deportation of more than 172,000 enslaved people. Some made large profits, others losses. The Swiss economy profited in several ways: On the one hand, through the direct profits that flowed into Switzerland, but also through the cheap raw materials from the colonies, such as cotton for the textile industry.

However, the question of whether Switzerland (as a state) also became rich as a result of its colonial connections is difficult to answer on the basis of current research. Individual companies and families undoubtedly benefited from colonialism, while the majority of the Swiss population still lived a poor and underprivileged life around 1900. It is important to point out that there is still a research gap (partly because certain archives in Switzerland are still inaccessible to researchers).

Swiss Colonial Human Trafficking

National Museum Zurich (Copyright)

JBW: While many have an idealized picture of Switzerland as a bastion of neutrality, the martial valour and cunning of Swiss mercenary soldiers is as storied as it's important in Swiss history.

What can you tell us about those Swiss who served as mercenaries in European armies abroad? How are their actions presented within Colonial?

MA: For a long time, Swiss mercenaries have been remembered in a very positive light, ignoring the violence they both committed and experienced. Swiss mercenaries served in European colonial armies from the end of the 16th century, taking part in violent campaigns of conquest and the maintenance of colonial order. For example, the exhibition presents Hans Christoffel, a mercenary from Graubünden who served in the Royal Dutch Indian Army from 1886 to 1910. He was known for his authoritarian military style and his unscrupulous behaviour, including several massacres of indigenous people, for example on the island of Flores in present-day Indonesia. In a film, the descendants of the survivors of these massacres explain how they remember the mercenaries and the excesses of violence.

JBW: A sizable number of Swiss men and women traveled the world as missionaries, and an entire section of the exhibition is dedicated to their activities and religious zeal.

What is their significance in Swiss colonial history? How did they shape colonial ventures and settlements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America?

MA: Missionaries worked with local authorities to establish hospitals and schools. Although they were sometimes agents of social change, their relationships were often characterised by a paternalistic self-image. Above all, we show how the missionaries shaped the image of the colonies and the colonised, especially the image of "inferior" cultures, in Switzerland.

JBW: Can you tell us about how scientists at the universities of Zurich and Geneva formulated race theories to legitimize colonial systems in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries?

MA: Around 1900, the universities of Zurich and Geneva became international centres for so-called 'racial anthropology'. Alleged 'racial anthropologists' measured the skulls of people from all over the world and classified them into 'races'. The method of the 'Zurich School' in particular became the internationally accepted standard from the 1920s onwards. These analyses were also used to protect an allegedly endangered 'white race'. So-called ‘Race theory' and eugenics were still practised in Switzerland in isolated cases until the 1960s. Today, thanks in part to genetic research, the idea of a 'human race' has been officially discredited.

Swiss Colonial Science

ETH-Bibliothek Zürich (Copyright)

JBW: By drawing parallels to contemporary issues, Colonial also ponders the open question of what this colonial heritage means for present-day Switzerland.

With that in mind, how should visitors grapple with the complex nature of Switzerland’s colonial entanglements? Moreover, what would you like visitors to walk away with following a tour of Colonial?

MA: With all these historical issues, we have always been concerned with the question: what does this have to do with us as a society? It is not our responsibility what people did before us. But it is our responsibility how we deal with this colonial legacy. Because colonialism has left its mark, in our language, in our history books, in our administrations, in our minds. Colonial mindsets still have an impact today, and in order to recognise and break them, we need to understand where they come from. Visitors should realise that Switzerland, as part of the global world, also has to deal with the consequences of colonialism.

Swiss Colonial Entanglements Exhibition Space

National Musuem Zurich (Copyright)

JBW: On behalf of World History Encyclopedia and its readers, I thank you very much for sharing your time and expertise with us.

MA: Thanks very much for your interest in our exhibition.

Colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements is on show at the National Museum Zurich through January 19, 2025. The exhibition continues in an adapted form, from 27 March to 11 October 2026, at the Château de Prangins.

Marina Amstad is a historian and exhibition curator at the Swiss National Museum. She studied history and Slavonic studies in Basel, specialising in modern and contemporary history. Since 2016, she has been working on various exhibitions at the National Museum Zurich. She is co-curator of the exhibition Colonial—Switzerland’s Global Entanglements.

Continue reading...

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS IS THE CHAMPIONSHIP'S FINAL ROUND!

More info about flags below

Cecil County MD

The flag is red and white, divided vertically, with the red next to the hoist, and the white portion in the fly. On the white portion is a representation of the county seal. The flag was designed by B. B. Martin, near Elkton, and was adopted as the winning entry in a county-wide contest sponsored by the Cecil County Chamber of Commerce.

Bob Barnes (reference archivist at Maryland State Archives), 1998

Mercer County OH

On April 4, 2002, the County Commissioners adopted this official county flag for the first time in its history. The celebration of Ohio's 200th Birthday was the catalyst for the endeavor. Over thirty designs were received from students, residents and workers of Mercer County. The commissioners accepted the flag created by a group of nine individuals employed by Fanning/Howey Associates located in Celina, the county seat.

The flag is colorful, yet simple, and clearly represents the pride of the community. Agriculture is represented by a silhouette of an 1800's style barn. Three amber bands across the bottom represent the different colors of crops as they ripen and are ready for harvest. The lighthouse signifies Grand Lake, the largest man-made lake in Ohio. Beams radiating from the lighthouse stand for all six Mercer County schools: red for St. Henry, orange for Coldwater, gold for Parkway, green for Celina, blue for Marion Local, and purple for Fort Recovery.

The flag committee added one final touch to the design. The foundation of the lighthouse was modified to have fourteen stone blocks. Each block represents one of the townships. The county was named after General Hugh Mercer of the Revolutionary War.

The Ohio Channel

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please innumerate for us the specialized problems of the library sciences.

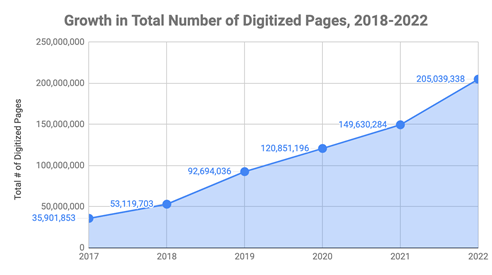

Let me start with the caveat that my information is based on my experiences at the National Archives more than a decade ago, and policy has definitely changed on this front as we can see from this graph of recent digitization - apparently NARA wants to get to 85% digitization by 2026. (Even still, I'd note that the records of the WPA are <0.001% digitized.)

However, back when I was doing the research that would eventually become my first book, I remember being at the National Archives II building in College Park, Maryland (Go Terps!) and getting really frustrated that all the records of the WPA were only available in their original physical form and that all the guides and indexes were also in paper only and were all from the 1970s, and I asked the archivist why the hell the National Archives hadn't been digitized already.

This is what they told me: if it's handled correctly and stored in the right environmental circumstances, paper can last a thousand years. Carbon copies can last even longer, if they don't rip. (Seriously, the bastard things are like onion skins, they'll split if you look at them funny.) Microfilm is slightly more technologically advanced than paper, but it only lasts 500 years in the right conditions.

We've only had computers en masse since the 1980s, and already there's a huge amount of records (especially from the early years) that we don't have any more, because the hard drives got re-formatted due to higher costs of storage space back in the day, or because old computers got thrown out when they were replaced by newer models and the hard drives are all rotting in landfills somewhere, or because backwards compatibility broke down and we just can't read those file types on our modern computers, or because the actual data got corrupted on the disc, or because some legacy company is asserting copyright against a video game museum, or because some political hack and/or president of the United States decided to violate the Presidential Records Act.

While we thought that the internet would cause an explosion of written records from ordinary people on the scale of the advent of mass literacy, there are vast swathes of the early internet that simply do not exist any more because the servers got switched off when Geocities et al. folded in the dot-com bubble burst or when everyone migrated to Web 2.0, and the Internet Archive tries its best (bless its heart, affectionately) but it can't be everywhere and save everything.

As a result, the archivist told me, digitization is a fraught question: what file format do we use? How do we know that file format will still be compatible and backwards-compatible in 50 years? 100? Longer? Do we keep everything locally or store it on the cloud, and how do we ensure that the storage mechanisms won't fail if there's a blackout or a virus or whatever? Do we digitize everything now, or do we wait until optical character recognition improves enough to the point where digitized records can be searched for words and phrases? Etc.

Keep in mind, I am a public policy historian who studies the 20th century U.S - I work primarily with the official records and the central archives of the richest government in the world. From a library sciences perspectives, this is kind of an ideal scenario, and it's still kind of fucked up. (Let me tell you, the rage and grief I felt when I learned that most of the General File of the Public Works Administration was thrown away by the National fucking Archives and Records Administration in the mid-1950s because they were running out of shelf space in the D.C location and didn't think these records were important...)

Now imagine what it's like at a local historical society or a small liberal arts college, or the national museum of a developing nation for that matter, who do not have the resources for the kind of grand digitization project that NARA started doing five years ago. Think of the sheer scale of historical records that sleep, unseen and untouched perhaps for decades and perhaps for ever, in little cubbyholes all across the world. Among professionals, historical records are measured in linear and cubic feet - think about that for a second, how many pages of paper there are in a foot when you stack them up, and how many hundreds and thousands and millions of feet there are across the face of the world. Think of all the millions of feet of pieces of paper that have been lost to us because of fire or rot or war or time itself.

This is why Peter Turchin is a quack. Historical records are not a standardized little database for social scientists to plug their fucking spreadsheets into; historians don't play that kind of bullshit t-ball, with all our data neatly packaged and handed to us on a silver platter. Our profession is not a social science, it's a goddamn treasure hunt through boxes that were never catalogued or categorized (or that were re-catalogued so many times no one remembers how they were put together in the first place) to find writing that no one has read since the authors died. All of us know that our work, our understanding, will always be partial and limited, because memory is infinitely fragile and the very idea of historical preservation is a mad existential defiance of entropy itself. These records are real, they are fragile - to hell with the Library of Alexandria, remember the National Museum of Brazil? - and they are all that is left to us of the dead.

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey! this is kind of a longshot -- and if youre totally not comfortable answering this then no worries -- i know youre probably in the more appalachian side of maryland, but would you happen to know anyone renting out somewhere more in the eastern side of MD? just got a job at the national archives and trying to find a nice place!

Unfortunately, I am in the western end of the state; I do not know anyone in the eastern shore area. Wait, National Archives - that would be DC area? Oof, sounds like a pretty cool job in a really difficult (traffic) area! I will toss this out to my followers, see if anybody has any ideas.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

archive #2, pt 1

the constitution!

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America Article. I. SECTION. 1 All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives. SECTION. 2 The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature. No Person shall be a Representative who shall not have attained to the Age of twenty five Years, and been seven Years a Citizen of the United States, and who shall not, when elected, be an Inhabitant of that State in which he shall be chosen. [Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.]* The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut five, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland six, Virginia ten, North Carolina five, South Carolina five, and Georgia three. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Election to fill such Vacancies. The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. SECTION. 3 The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, [chosen by the Legislature thereof,]* for six Years; and each Senator shall have one Vote. Immediately after they shall be assembled in Consequence of the first Election, they shall be divided as equally as may be into three Classes. The Seats of the Senators of the first Class shall be vacated at the Expiration of the second Year, of the second Class at the Expiration of the fourth Year, and of the third Class at the Expiration of the sixth Y

Year, so that one third may be chosen every second Year; [and if Vacancies happen by Resignation, or otherwise, during the Recess of the Legislature of any State, the Executive thereof may make temporary Appointments until the next Meeting of the Legislature, which shall then fill such Vacancies.]*

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#VoicesFromTheStacks

Image: Oscar Hahn from La Tercera

Oscar Hahn

Oscar Hahn, born in Iquique, Chile in 1938, began writing poetry early in life. The first book of poetry Hahn published, Esta Rosa Negra, in 1961, included poems he had written between the ages of 17 and 19. Once graduated from the University of Chile in 1963, Oscar attended the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa and received his M.A. in 1972. Upon completion of this program, Hahn returned to Chile to teach, but was arrested after the 1973 coup d'état and held in an Arica prison. Within our Oscar Hahn collection, there is a testimonial about these days in jail and their aftermath, dealing in part with how it affected him as a writer. After his release, he returned to the states and obtained a PhD from the University of Maryland, where he studied until 1977, when he returned to the University of Iowa, joining the Spanish-literature faculty.

Image: Imágenes nucleares y otros poemas by Oscar Hahn

Hahn is a celebrated, leading poet of his generation, sometimes called the Dispersed or Decimated Generation (Generacion Trilce). According to a biographical sketch in the collection, critics praised Hahn’s blend of fantastic, ironic, and realistic elements in his work, leading to the association of postmodernism and surrealism. One highlighted critical response from Kirkus Reviews contributor says Hahn “takes ordinary situations and images and implants within them a kind of surrealist grenade that explodes when least expected – and with striking effect.”

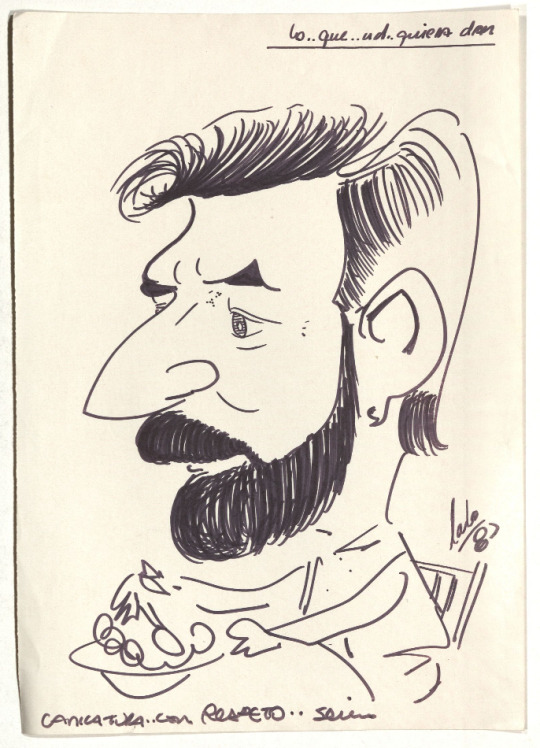

Image: Caricature drawing of Hahn from the Oscar Hahn Papers

In Special Collections and Archives, we have the Oscar Hahn Papers, containing a fairly complete list of Hahn’s publications and materials about him as well some published works in the monograph collection. A link to the collection finding aid can be found here.

-Kaylee S., Special Collections, Olson Graduate Assistant.

#uiowa#special collections#uiowaspecialcollections#voicesfromthestacks#library#poetry#chilean poetry#chile#oscar hahn

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moments before the kickoff of the 118th United States Congress in January, incoming GOP leaders ripped down Nancy Pelosi’s post-insurrection magnetometers, which had stopped at least one Republican, Representative Andy Harris of Maryland, from entering the House floor with a handgun. The first meeting of the House Natural Resources Committee, held on February 1, devolved into partisan vitriol as Republicans reversed an explicit ban on members bringing firearms into their hearings. Soon, AR-15 pins started popping up on rank-and-file lapels. Then, two weeks later, a bill was introduced to make the mass-shooter-approved AR-15 the “national gun of the United States.”

This may be Joe Biden’s Washington, but the US Capitol appears to be, once again, under the firm grip of the gun lobby. With repeated threats of federal government defaults and shutdowns consuming Washington throughout 2023, little attention has been paid to specific agency-by-agency spending proposals, including a House Republican proposal to zero out funding for gun violence research at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). That effort, part of a House appropriations bill, was postponed after Congress passed a short-term extension to fund the federal government into early next year. But that doesn't mean it won't return then, with powerful Republican lawmakers painting the CDC's research as overtly partisan.

“I think it may have a political component, and that's my concern,” Representative Robert Aderholt, an Alabama Republican, tells WIRED. He’s known as a cardinal on Capitol Hill because he chairs the Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies, which is tasked with producing the nation’s largest domestic funding measure, including control of the CDC’s budget, each year.

The powerful appropriator isn’t thoroughly versed in the gun violence research his subcommittee is trying to defund, but Aderholt is skeptical anyway. “If it were just honest, innocent research, then I wouldn’t have a problem,” Aderholt says. “But I have some concerns with the way that it’s being handled under this administration.”

Thing is, no one really knows what story the CDC research will tell. It’s only been around for three years after nearly a quarter-century of congressional prohibition under the 1996 Dickey Amendment, which essentially barred the CDC from examining the roots of the uniquely American scourge of gun violence.

“This is about public health,” Rosa DeLauro, the top Democrat on the labor committee, tells WIRED. “We haven’t had it for 20 years. Think about all the research that was done about seatbelts and prevention. So I think about what’s happening with the uptick in gun violence, which is unbelievable … we need to do the research to help us be able to prevent that.”

In 2018, lawmakers upended the Dickey Amendment, explicitly clarifying that the will of Congress is for the CDC to research the contemporary weaponization of America. But federal dollars—which, contrary to GOP concerns, are still strictly forbidden from being used to promote gun control—didn’t start flowing to researchers until 2021. Democrats have pushed for $50 million annually to research America’s second-leading cause of death for people 18 years old or younger. (The first is motor vehicle accidents, which Congress devoted $109.7 million to research in the 2022 fiscal year.) But for the past three years, they’ve only been able to squeeze $25 million a year—split between the CDC and National Institutes of Health—out of Republican senators.

With more than 39,000 gun-related deaths so far in 2023, according to the Gun Violence Archive, America’s on pace to endure another record-setting amount of carnage by year’s end, which you wouldn’t know from the giddily gun-friendly mood on the House side of the Capitol. “I think the Republicans are just nuts on this, you know, the extremes,” Mike Thompson, a Democratic representative from California, tells WIRED. Nuts or not, Republicans control the House.

Even through the tears stemming from America’s recent uptick in gun violence—including homicides, suicides, and mass shootings—the past three years have been an exciting time for researchers in this space, because when the federal government leads, university research follows. The two-plus decades drought has rippled through academia.

“People weren't going into this field because you couldn't make a career in it,” Andrew Morral, who runs RAND Corporation’s Gun Policy in America Initiative, tells WIRED. “It’s the kind of thing where it takes a fair amount of research before you start getting believable findings. I mean, you can have a study or two that show something, but in social science, it's very hard for one or two studies to persuade anyone.”

Morral is also director of the National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research, which is philanthropically endowed with $21 million earmarked for firearm violence prevention research. A few years back, he led a conference with “30 to 100 people.” At the start of the month, when they held their annual meeting in Chicago, there were 750 attendees, including some 300 presenters whose studies ranged from how “guns provide access to sources of life meaning” for some Floridians to whether there’s any correlation between heat waves and shootings.

“A lot of new questions are being asked and new ways of looking at things—this just wasn't possible five years ago,” Morral says. “There [are] people coming into the field now, and that's what the money is doing. It's making it possible to get this field launched. There's a lot of low-hanging fruit here, but it's going to take a lot of research to start getting persuasive findings and it's starting to happen.”

In the wake of horrific mass shootings at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, and a grocery store in a predominantly Black neighborhood of Buffalo, New York, last year, before the GOP recaptured the House, Congress passed the sweeping Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA), aimed at improving the nation’s background check system, stymieing gun traffickers, protecting domestic violence survivors, and enhancing mental health services in local communities and schools from coast to coast.

The measure includes billions for mental health, $250 million for community violence intervention programs, and $300 million for violence prevention in the nation’s schools. It also recognizes the federal deficiency in school safety research by creating a Federal School Safety Clearinghouse, envisioned as a repository for the best “evidence-based” research for keeping violence off American school grounds.

That best-practices clearinghouse for schools was a GOP-sponsored provision that made it into the BSCA, but, as WIRED reported last summer, studying gun violence wasn’t a part of negotiations on the measure aimed at curbing gun violence. This latest effort by House Republicans to effectively bar the CDC from researching gun violence has social scientists worried about the real-life consequences of turning off the federal funding tap again. The two Senate Republicans who negotiated the BSCA aren’t worried.

“People misuse research every day,” Senator Thom Tillis, a North Carolina Republican, tells WIRED. The other Republican who had a seat at the head table for last summer’s gun negotiations is one of minority leader Mitch McConnell’s top lieutenants, John Cornyn of Texas—a leading contender for replacing the ailing GOP leader in the Senate—who shrugs off CDC gun violence research. “I don't think there's any shortage of research in that area,” Cornyn tells WIRED. But he bifurcates gun violence research from gun violence prevention. “We haven't been able to figure out how to solve all the crimes. Basically, we've tried to deter them, we've tried to investigate and prosecute them, but we haven't been able to figure out how to prevent them. So that's the basic problem, I think.”

Democrats agree. They also say the reason for that “basic problem” is clear: The CDC—through the chilling effect the federal prohibition had on academia over 24 years—has failed to foster a robust research environment to accompany America’s robust gun culture. But Democrats aren’t looking to pass reforms this Congress. Sure, they want to. But the House is barely performing at its normal rate of functional-dysfunctionality these days (just ask newly-former House speaker Kevin McCarthy). Senate Democrats are willing to have a gun violence prevention debate, but as of now, many say there’s no reason to try and debate House Republicans.

“They're not writing bills that are designed to pass the Senate in order to get signed by the president. They're literally throwing red meat to the fringe on every conceivable issue. That's just not serious,” Senator Chris Murphy, the Connecticut Democrat who was at the center of last summer’s gun reform negotiations, tells WIRED. “At some point, they're going to have to figure out how to pass a bill with us, but they haven't reached that space yet.”

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved on our archive (Daily updates!)

Weird how this "endemic" German strain is poised to dominate worldwide... That almost sounds like a pandemic :O

By Ahjané Forbes

KP.3.1.1 is still the dominant COVID-19 variant in the United States as it accounts for nearly 60% of positive cases, but the XEC variant is not far behind, recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data shows.

"CDC is monitoring the XEC variant," Rosa Norman, a CDC spokesperson told USA TODAY. "XEC is the proposed name of a recombinant, or hybrid, of the closely related Omicron lineages KS.1.1 and KP.3.3."

The variant, which first appeared in Berlin in late June, has increasingly seen hundreds of cases in Germany, France, Denmark and Netherlands, according to a report by Australia-based data integration specialist Mike Honey.

The CDC's Nowcast data tracker, which displays COVID-19 estimates and projections for two-week periods, reflected that the KP.3.1.1 variant accounted for 57.2% of positive infections, followed by XEC at 10.7% in the two-week stretch starting on Sept. 29 and ending on Oct. 12.

KP.3.1.1 first became the leading variant between July 21 and Aug. 3.

The latest data shows a rise in each variant's percentage of total cases from Sept. 15-28, as KP.3.1.1 rose by 4.6%, and XEC rose by 5.4%. Previously, the KP.3.1.1 variant made up 52.6% of cases and XEC accounted for 5.3% from Sept. 15-28.

Here is what you need to know about the XEC variant and the latest CDC data.

COVID-19:Your free COVID-19 at-home tests from the government are set to expire soon. Here's why.

Changes in COVID-19 test positivity within a week Data collected by the CDC shows a drop in positivity rate across the board, while the four states in Region 10 had the biggest decrease (-2.7%) in positive COVID-19 cases from Sept. 29, 2024, to Oct. 5, 2024.

The data was posted on Oct. 11.

Note: The CDC organizes positivity rate based on regions, as defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Here's the list of states and their regions' changes in COVID-19 positivity for the past week:

Region 1 (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont): -2% Region 2 (New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands): -1.9% Region 3 (Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia): -1.3% Region 4 (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee): -0.6% Region 5 (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin): -2% Region 6 (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas): -0.8% Region 7 (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska): -1.7% Region 8 (Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming): -1.2% Region 9 (Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Marshall Islands, and Republic of Palau): -1.3% Region 10 (Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington): -2.7% The CDC data shows COVID-19 test positivity rate was recorded at 7.7% from Sept. 29 to Oct. 5, an absolute change of -1.8% from the prior week.

COVID-19 symptoms The variants currently dominating in the U.S. do not have their own specific symptoms, the CDC says..

"CDC is not aware of new or unusual symptoms associated with XEC or any other co-circulating lineage of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19," Norman said.

The government agency outlines the basic symptoms of COVID-19 on its website. These symptoms can appear between two and 14 days after exposure to the virus and can range from mild to severe.

These are some of the symptoms of COVID-19:

Fever or chills Cough Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing Fatigue Muscle or body aches Headache Loss of taste or smell Sore throat Congestion or runny nose Nausea or vomiting Diarrhea The CDC said you should seek medical attention if you have the following symptoms:

Trouble breathing Persistent pain or pressure in the chest New confusion Inability to wake or stay awake Pale, gray, or blue-colored skin, lips, or nail beds

#mask up#covid#pandemic#wear a mask#public health#covid 19#wear a respirator#still coviding#coronavirus#sars cov 2#XEC

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

chapter 11 of till the road and sky align is now up! featuring the lovely state of maryland and some lawrence backstory. enjoy!

6 notes

·

View notes