#mark wunderlich

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

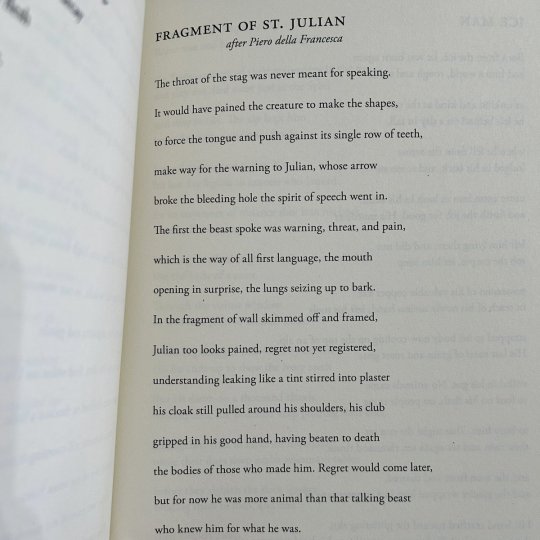

- Mark Wunderlich, Fragment of St. Julian.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

A poem by Mark Wunderlich

Raccoon in a Trap

The kidskin of his clever paws charcoal black and clawed like a witch

scratch at the turf. Hanging his head he hunches like a bear and in his fur turns

a boggy funk, a whiff like the hairy belly of a man. I carry the cage to the edge of the woods

and he barks, bares a grin of sharps, points a flinty nose, moist and smart

to read his future on the air. I believe this is the thief who stole the nest of chicks,

tore the vent from a hen and ate her in the company of her peers—a husbandman’s

springtime menace, the glowing eyes in the night. In the orchard, morning clouds

disperse. The sun returns for another run pulled by the beasts of myth

before I put the muzzle of the gun through the wires and fill his warm head with lead.

Mark Wunderlich

0 notes

Text

I imagine them as they wander the high peaks, rippling like figures underwater, like figures one dreams and forgets, a shape drawn and erased so only the pencil's impression remains.

From "First, Chill" by Mark Wunderlich

0 notes

Text

Rilke’s First Duino Elegy is a deeply philosophical and existential work that reflects his broader themes of transcendence, beauty, suffering, and the limitations of human perception. It is enriched by concepts from classical studies, particularly in its allusions to Greek mythology, classical heroism, and Platonic ideas about the nature of reality and longing.

Context of Rainer Maria Rilke Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) was an Austrian poet whose work often explores the tension between the material and the spiritual, the transient and the eternal. His Duino Elegies, written between 1912 and 1922, reflect his preoccupation with metaphysical longing, artistic creation, and the terror inherent in beauty. These elegies were influenced by his experiences in Duino Castle, as well as his readings in philosophy, art, and mysticism. Rilke’s writing often places human existence in contrast to the divine or the infinite, emphasizing a feeling of estrangement and the necessity of transformation through suffering and embracing it as much as the nurturing solitude offered by life to us, which he expresses as being not just beneficial but necessary. He deeply valued solitude, seeing it as essential for personal and artistic growth. He believed that solitude was not loneliness but a necessary state for self-discovery, inner strength, and creativity. Rilke viewed solitude as a way to confront one’s deepest thoughts and emotions, fostering a deeper understanding of oneself and the world. In Letters to a Young Poet, he advised embracing solitude rather than fearing it, arguing that it allows individuals to develop independence, patience, and emotional depth. He saw solitude as a space where one's soul could mature, free from external distractions and societal pressures. According to Rilke, true love and relationships could only flourish when individuals had first cultivated their own inner world, making solitude a foundation for authentic connections. For Rilke, solitude was not an escape but a path to wisdom, self-sufficiency, and a richer, more meaningful life. He believed that in solitude, one could listen to the whispers of the soul, unlocking creativity and personal transformation.

Use of Classical Concepts with in The First Elegy

Angels as Platonic Forms or Divine Messengers The poem opens with a desperate cry (which, to me, was reminiscent of the opening lines of Homer's Iliad): “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the Angels’ Orders?”

Rilke’s angels are not comforting figures but rather terrifying beings whose essence is too overwhelming for humans to bear. This aligns with classical and Neoplatonic views of divine beings as existing on a higher plane of reality, beyond human comprehension.

The idea that “Every Angel is terrifying” evokes the Greek concept of daimons—spiritual intermediaries between gods and humans in Platonic thought, which could be either enlightening or overwhelming.

Beauty and Terror—The Sublime in Classical Aesthetics “For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror, which we can still barely endure.”

This reflects a classical and Romantic notion of the sublime, where beauty is intertwined with awe and fear. The Greeks associated beauty (kalon) with both harmony and a kind of divine mystery that could lead to madness, as seen in the myths of Phaedra or Pentheus.

Alienation and the Stoic Worldview “Not Angels, not humans, and the sly animals see at once how little at home we are in the interpreted world.”

This echoes the Stoic perspective on human beings as estranged from a rational universe, struggling to interpret existence in meaningful terms. The idea of the interpreted world suggests an awareness that human perception is limited and filtered through subjective understanding.

Classical Lament and Mythology

The poem references the myth of Linos, a legendary musician mourned in ancient Greek laments. “Is it a tale told in vain, that myth of lament for Linos, in which a daring first music pierced the shell of numbness?”

The death of Linos, often seen as a foundational moment in the development of song and poetry, reflects Rilke’s belief in suffering as the origin of artistic creation. This aligns with the classical idea that poetry arises from grief, as seen in Orpheus’s lament for Eurydice.

Heroism and Fate “Remember: the hero lives on, even his downfall was only a pretext for attained existence.”

This recalls the Homeric and tragic Greek conception of heroism, where the hero’s suffering and death are not simply personal losses but transformative moments that give meaning to existence. Rilke’s hero transcends mere mortality by achieving a state of eternal significance, much like Achilles or Heracles.

Transformation and the Arrow as a Metaphor “The way the arrow, suddenly all vector, survives the string to be more than itself.”

This is reminiscent of Aristotelian and Platonic ideas of potentiality and actualization. The arrow is a symbol of release from earthly attachments, reflecting the classical idea that true existence lies beyond the constraints of the material world.

In Conclusion

Rilke’s First Elegy is a meditation on human limitation, divine terror, and the need to embrace suffering as a path to transformation. Through classical concepts—Platonic transcendence, the sublime, mythological lament, and heroic endurance—Rilke connects ancient wisdom with modern existential longing. His poetry echoes the classical world’s awareness of mortality, beauty, and the pursuit of meaning beyond the tangible realm.

#academia#dark academia#light acamedia#learning#studying#classical studies#modern studies#liturature#Rainer Maria Rilke#poetry#poetry recs#writer recs#Platonic#Aristotelian#classical literature arts#classical literature#Classical Aesthetics#stoicism#philosophy#classical philosophy#just a fun little addition i tried to summarize best i could of what i saw in this work#the secret history#i really feel Donna Tartt was inspired by Rilke#Donna Tartt#analysis#literature analysis#nothing in depth but again tried to keep everything brief as i could

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm going to start a poetry collection for Dean Winchester and you may think the first addition would be something from the renowned classic and this, your living kiss or perhaps from lazarus rises (amongst other things) but it will, in fact, be The Prodigal by Mark Wunderlich

#of course my papa's waltz and those winter sundays will make an appearance as well#and i will likely spend a very long time trying to narrow down some poems from lazarus rises to include#but only after the prodigal#some of us are having a moment paralleling the prodigal son parable to early seasons dean and sam#also i do think dean from atylk would get more out of this poem than canon dean#but it was published two years after atylk so they didn't really have it on hand#alas#dean winchester#poetry#supernatural#spn#dean winchester poetry anthology#ari talks about whatever they want forever

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homes or houses: A sensory explanation of Cathays by Lara Rowe

I take my first steps on Merthyr Street; it’s exactly 09:19 in the morning on an all too familiar day – bin day. The glistening sun peaks far ahead of the rows of disordered terraced houses before me, illuminating the multicoloured plastic, like a solar glitterball – but the atmosphere remains uncomfortable with tension. I begin to head down the pin straight route towards the end of the path, assessing everything from the level of my shoelaces to the upward reach of my eyes. The pavement, uneven and cratered, introduces me to each blue and red plastic bin sack at the kerbside as I pass, some abandoned, some ruptured and some bursting at the seams with household castaways yet to be collected. My feet traverse their contents bleeding onto the street: crushed Red Bull cans, defaced Domino’s boxes, limp cucumber slices sealed in condensation-slick plastic. A trail of crinkling crisp packets flurry alongside me as I keep pace, and I notice the glare of wine bottle necks protruding from overflowing glass bins, sympathetic to their perhaps once good night but rather heavy morning. So typical of Cathays calamity, the mess feels performative, almost ritualistic in its regularity and merely a weekly marker of student occupation and signs of the rhythms of student living (Wunderlich 2008; Hubbard 2008).

The wind is fierce as I make my first turn onto Minister Street, leaving not only my hair strewn across my face but litter and tumbling blue and red polythene bags across the street too. A brown food caddy brushes past my ankles, trickling along the street in symphony with its peers to produce a soft rhythmic melody of hard plastic bouncing across everything from the very tarmac of the road to the wheel rims of cars and front doorsteps. I am alone on the street, and am reminded of an ‘outback’ scene with tumbleweeds running free, except I am not in the middle of nowhere, I am in a distinctly urban student ‘mini-city’. Far from passive waste I’m reminded of their symbol of transience, of absent care. Not just refuse, but rather residue – a sticky by-product of student life, of landlord neglect. The mess I see before me is not simply mess, but a marker of movement, disregard and exclusion (Puwar 2019). I stop and stare at the stains with stories of temporary belonging, lived in and absorbed everyday by all who occupy.

I leave the residue of Merthyr and Minister by reaching my first major turn, this time a sharp right towards Maindy Road. I stumble over my laces as I do so, and look round sheepishly to ensure nobody saw. There is distinct hustle and bustle to this street. Where Merthyr was slumped and sluggish, Maindy is bright and bold. The air thickens as I’m met by swathes of cars mounting and demounting the speed bumps towards the city centre, their bumpers barely surviving the scrape. Beyond the bumps stand tall a cluster of brand new Cardiff University buildings; their illuminated ruby red logos reflecting onto a row of dilapidated terraced houses opposite mark this territory as very much student occupied (Hubbard 2008). Here my attention returns to the rhythm of the street, not the slow shuffle of bin bags and food caddies dancing around the kerbs, but a mechanical beat marked by engines, tyre screeches and the occasional horn to cut through the morning air. The sounds spark my senses and I can sense a difference, this feels more lively, more urban – I feel more alive. As I continue my plod I spot the notorious Cathays Lidl sign, my stomach correspondingly rumbling on cue at the accompanied wafting aroma of freshly baked croissants. I note the way I am now experiencing my surroundings not through mere external observation, but vivid bodily perception and embodiment (Pink 2009). As cars continue their convoy beside me I appreciate our shared use of the space, we are all but people on a journey after all, but I mourn for their lack of same interaction and appreciation with the space from within the walls of their restrictive metal box (Ingold 2004).

Now 09:35 and with my feet warming to the pace, I cross the subtle threshold into Llantrisant Street through a small patch of freshly cut grass. A group of boys bustle past on their morning run, perhaps for exercise, perhaps for aforementioned croissants – the beauty of life is I will never know. The liveliness of the streets reflect space as so actively shaped by human presence, a choreography of movement scent and sound. The noise, smells, and visual cues for which I am lucky enough to observe form the very foundations of the social production of space (Wunderlich 2008). From the rich smell of French pastries to the blur of boys sprinting past, and the hum of negotiating speed bumps, this stretch is infused with everyday rhythms of student life. The space is not merely a backdrop or landscape, but a social product continually created and recreated through the bustle of activity and shared use (Lefebvre 1991). I pause for a moment, leaning on the outside wall of the Tesco Express I’ve made many an evening trip to. My legs ache slightly, but not through fatigue. It’s a kind of awareness, as though my calves are situating themselves in a sociological experiment in real time. The tinges intensify, today they’re demanding more from me. A gaze? A thought? Perhaps a responsibility for appreciation, attention, ownership, and presence (Springgay and Truman 2019). A dog sits beside me and I smile and laugh in appreciation as the sun beams down, both his ginger fur and my ginger hair radiating in the light.

Upon my next transition to Cathays Terrace I’m met immediately by a shift, in atmosphere, but too density of decay. The houses slouch before me, brimming with neglect – an astounding contrast to the shiny University buildings I’d been admiring a mere few steps back. I stare at one particular house in the distance, number 45. The 5 is askew on the door, a light breeze perhaps enough to brush it fully ajar and turn number 45 into its lesser number 4. Plonked in the front window is a faded sign that reads ‘To Let: Students Only’. This doesn’t come to my surprise. The white paint of the porch is now a mottled grey and peeling like sunburnt skin, black mould peeks through the windowsills and the net curtains appear wet, damp, and 40 years out of fashion. These are not homes lovingly maintained. They are transactions, holding cells between terms, eagerly anticipating the start of a new academic year to increase their holding fees yet once more (Sage, Smith and Hubbard 2012). The living rooms turned bedrooms are easy to spot: curtains drawn tight all hours, blackout blinds clinging to window frames from the inside. I consider each rotting bay window as I pass, envisioning hastily constructed contract terms and group chats with incompetent letting agencies, not Sunday dinners or birthday balloons taped to the wall. My surroundings, though bustling with light, feel grey.

The further my step count reaches the greater embedded landlord neglect becomes here. ‘To Let’ signs continue to flutter like flags of indifference, and every cracked drainpipe, crumbling doorstep and moss-caked garden wall repeats a familiar narrative: minimum investment for maximum return. As Sage, Smith and Hubbard (2012) agree, student housing becomes easy pickings for real estate, commodified by absentee landlords and managed by letting agents concerned only with yield, student houses are a pot of gold for the rentier class (Howard 2024). I navigate myself across the zebra crossing on Cathays terrace, putting my hand up to thank the driver as I do, and embark on my new foundations of Lisvane Street. A smile once again creeps upon my face. To my left I see a small front garden, neatly kept, with daffodils arranged in chipped terracotta pots and a ring doorbell overseeing the order. Amongst the decay of student living I’ve witnessed so far, the presence of long-term residents feels quieter, yet too somehow louder. A silent battle of modest gestures of care and security against collapsing porches and jungle-like driveways that dominate the rest of the streets. The fragile remnants of what came before the studentification of these walls peeks through the cracks like a glimmer of light (Atkinson and Bridge 2005). Listening to what I’m being presented with here sees far beyond initial presentation of ‘ugly’ and ‘pretty’ houses. When fully considered it speaks to a story of studentification and gentrification here (Back 2007); your environment will always tell a story, you just have to listen to it.

The more I observe, the more I find the contrast unsettling. Where long-term residents remain, their homes emit a different frequency. I ponder what it means to them to live within this shifting topography – not of people but of priorities. To have the area of your family home overrun with constant influxes and retraction of students. An embodied tension – the litter, the neglect, the noise – all become material evidence of a mini-city reshaped by institutions and investors, not by neighbours or nuances (Sage, Smith and Hubbard 2012). I tremble as I continue, a deep discomfort within me the more I recognise and occupy these streets. In an attempt to distract from my guilt I take the first available route change I can, another sharp right, to be greeted by the iron fencing of Cathays’ primary school. I smile once more. The usual soundtrack of clattering bins and revving engines has been replaced by a playful cacophony of children’s voices rising form the playground. I hear ‘hopscotch’ and ‘tag’ being played, immediately taking 18 years from me, and putting me back in their place. It's a poignant contrast to my previous emotion, and a stark reminder of a need to more than observe but feel the space that I occupy (Ingold, 2004).

Upon completion of my cyclical loop I arrive where it all began – Merthyr Street. For my closing observations I admire the intercalations of Merthyr Street – a street in her own right, yet one from which tributary roads unfurl – Minister, Treorky, Treherbert, Hirwain, and Llantrisant. The signs latched onto houses all sit rusty and seemingly loose. I come to appreciate her as the mother street of Cathays. A structural and social artery, she forms the foundations of a hive of interaction, a place where pathways converge and diverge, both hellos and goodbyes are simultaneous, each one bearing its own rhythm of everyday life. I admire her architecture. It is tired, her bricks are chipped and walls weathered, but she thrums with human presence as pedestrians and cars pass by me. More than a route – she mothers her unique cast of characters as a navigation of the shifting social and cultural terrains of urban life, and provides a landscape for exploring the reasons we enter and occupy public space with one another (Butler 2012). My admiring of her crumbling architecture, even as a mother, brings me back to stark reality. Regardless, the crumbling architecture here is still shaped by temporary occupation, not long-term care and love. The temporality and brokenness begin to mirror the impermanence of student life itself. And my presence and part in this only seeks to reaffirm it. I stop and stand outside my front door, jingling my keys and visualising myself. I turn towards my front door, raise my key to the lock, and recognise my reinforcement of a need for these bulging HMOs and displacement of stable communities. I hang my head, I am part of the problem. I am the tension and the mess that feeds Cathays’ uncomfortable atmosphere.

Methodological Note

This sensory walk-through Cathays was not just about documenting urban decay or student mess; it was about the meaning that lay behind, and being moved – emotionally and physically – by a space I thought I knew. Walking as a method allowed me to engage directly with the rhythms and textures of my environment as not a passive observer but an implicated presence. An appreciate of the city’s ‘mundane’ details was imperative but too eye opening (Bates and Rhys-Taylor 2017) as it was within the details of the sounds of crashing caddies, the scent of croissants near Lidl and the textures of crumbling bay windows that the social life of Cathays came alive.

I approached this walk intuitively, guided by my feet alone with no real plan of action or destination in mind, simply a heightened sense of attention to what might emerge and the corresponding relation to my emotions. My course was dictated strictly by whatever piqued my interest at the time; mainly, the rabbit hole of dilapidated student housing. The noises, smells, and visual cues that weave the fabric of socially occupied space were afforded to me only because of my presence on foot, had I been driving or even cycling there would have been barriers to the unfiltered interaction with the space I was granted (Ingold 2004). I was experiencing the city through the aches in my legs, the shifting rhythms of breaths as I peruse row upon row of collapsing terraced house. The more I saw the more my surroundings spoke, not in words but in the flicker of a ‘To Let’ sign, the heavy quiet of a long-term residents front garden. Not merely passive observations, but invitations to understand the social and spatial politics embedded in the ordinary. Sensory ethnography emphasised an entirely different experience of Cathays than I would normally anticipate. An embodiment of my student town lead to far greater meaning than the mere external observation I was used to as I was immersed directly into the foundations and streets of Cathays, questioning every storytelling feature from the sky above to the ground beneath me (Pink 2009). It invited a kind of thinking in motion (Springgay and Truman 2019), my current steps dictated my next, but to do that they had to perceive and process first – what did it all mean? What marked this as a student area? As I progressed I noticed a shift in how I inhabited the space. It was no longer my daily walk to Tesco or to university, it was a practice of perception; lingering longer, and allowing myself to feel uneasy with what I found.

The slow pace was intended to explore the everyday details of mess, studentification, and landlordism that are so often filtered out. Sensory cues grounded me in the present, giving light to the notion of walking as a way of re-seeing the familiar (Ramsden 2016). I’ve walked these streets countless times, for the food shop, fresh air, or simply boredom, but never before with such situational attention. A habitual stroll was transformed into sociological witnessing, drawing out the overlooked nuances of landlord neglect and student takeover. I became increasingly aware of my own positionality within the landscape, both as a student and a contributor to the very studentification I was critiquing. Reflexivity was intertwined with my method, I was not walking through Cathays, I was walking with it and allowing it to tell me its story. I came to understand walking as a sensory, embodied way of knowledge passing, unsettling the boundary between the researcher and the researched (Pink 2009). What I encountered was not a neatly presented neighbourhood but a layered and breathing one, with contradiction in every breath. Walking as method afforded me an understanding of Cathays as not simply a student quarter but a place where rhythms collide, from the permanence of a primary school bell versus the ephemerality of student tenancies. Though uncomfortable, the approach offered more than mere observational offerings. It commanded my presence, my listening ears, and an acceptance that I too am part of the narrative. The walk made visible what often goes unnoticed – the quiet tensions of occupation, investment, and belonging.

Bibliography

Atkinson, R. and Bridge, G. (2004) Gentrification in a global context: the new urban colonialism. London ; New York: Routledge.

Back, L. (2007) The Art of Listening. Oxford: Berg.

Bates, C. and Rhys-Taylor, A. (2017) (eds) ‘Finding Our Feet’, Walking Through Social Research. London: Routledge.

Butler, C. (2012) Henri Lefebvre: Spatial Politics, Everyday Life and the Right to the City. Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group.

Howard, A. (2024) Seven propositions about ‘generation rent’. Housing Theory and Society, 42(1), pp.1–22.

Hubbard, P. (2008) Regulating the Social Impacts of Studentification: A Loughborough Case Study. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(2), pp.323–341. doi: 10.1068/a396.

Ingold, T. (2004) Culture on the Ground. Journal of Material Culture, 9(3), pp.315–340.

Pink, S. (2009) Doing Sensory Ethnography. London: SAGE.

Puwar, N. (2019) ‘Walking through Litter’, Life Writing Projects. Available at: https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/lifewritingprojects/place/nirmal-puwar/ [Accessed 17/4/2025]

Ramsden, H. (2016) Walking & talking: making strange encounters within the familiar. Social & Cultural Geography, 18(1), pp.53–77.

Sage, J., Smith, D. and Hubbard, P. (2012) The Diverse Geographies of Studentification: Living Alongside People Not Like Us. Housing Studies, 27(8), pp.1057–1078.

Smith, D.P. and Holt, L. (2007) Studentification and ‘Apprentice’ Gentrifiers within Britain’s Provincial Towns and Cities: Extending the Meaning of Gentrification. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 39(1), pp.142–161.

Springgay, S. and Truman, S.E. (2019) ‘Introduction’, Walking Methodologies in a More-than-human World: WalkingLab. London: Routledge.

Wunderlich, F. (2008) Walking and Rhythmicity: Sensing Urban Space. Journal of Urban Design, 13(1), pp.125–139.

0 notes

Text

Thank you for the tag, red!!!

1) The last book I read

A Children's Bible by Lydia Millet! It was pretty okay, but not really what I had expected

2) A book I reccomend

House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski <3 worlds least accessible book but I adore it, if you feel up to reading it you absolutely must

3) A book I couldn't put down

What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher, a very cool take on the Fall of the House of Usher that I really really enjoyed

4) A book I've read twice (or more)

The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux :) autism.

5) A book on my TBR

God of Nothingness: Poems by Mark Wunderlich. picked this up purely because the cover looked fun I am not immune to judging a book by its cover

6) A book I've put down

WEYWARD BY EMILIA HART. borderline TERFy women bloodlines witch book I haaaate it I don't know if I will ever finish it

7) A book on my wishlist

Cath Maige Tuired physical edition.....I long for you.

8) A favourite book from childhood

Maybe A Fox by Kathi Appelt, a very beautiful book to me that I absolutely reccomend. I've read and reread this one a lot as well

9) A book you would give to a friend

The Cat Who Saved Books by Sôsuke Natsukawa, its fun and silly and I like the weird worldbuilding

10) A nonfiction book you own

The Wager by David Grann, which was very very good, I couldn't wait to read more

11) What are you currently reading?

"Bobcat" and other short stories by Rebecca Lee, its just okay so far

12) What do you plan on reading next?

Omnibus by Dylan Thomas

Eyeeeee don't feel like tagging sorry. if you see this consider yourself tagged :}

13 books!

What’s up readers?! How about a little show and tell? Answer these 13 questions, tag 13 lucky readers and if you’re feeling extra bookish add a shelfie! Let’s Go!

(I was tagged by the kind @glueblade, thanks for sending the ask!)

1) The Last book I read:

The Lost Metal, by Brandon Sanderson

2) A book I recommend:

I really enjoyed The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller!

3) A book that I couldn’t put down:

It's a clichéed response, but Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir. Damn but I loved Gideon (the character) from the start and I wanted to know more about her.

Also Monstrous Regiment by Terry Pratchett. My favourite of his so far!

4) A book I’ve read twice (or more):

Do mangas count? Because I've read the Fullmetal Alchemist series by Hiromu Arakawa quite a number of times lol

5) A book on my TBR:

The rest of the Murderbot Diaries by Martha Wells. I only read the first novella so far, and I'm hooked!

6) A book I’ve put down:

I tried to read The Well of Time a couple of times, and I've never quite managed. I don't know why it just doesn't click with me.

7) A book on my wish list:

God, so many. I'd be curious to read anything by R. F. Kuang, like the Poppy Wars series and Babel.

8) A favorite book from childhood:

I was a big fan of the Bartimaeus series by Jonathan Shroud. Barty is still one of my favourite narrators ever.

9) A book you would give to a friend:

I have the tendency to lend my books to my friends, does it count? For one, I got two of them hooked on the Stormlight Archive series by Brandon Sanderson that way. I have a friend who would really like Uprooted by Naomi Novik too, but I haven't had the occasion to lend it to her yet!

11) A nonfiction book you own:

I like reading history books these days! So I have a few of Martin Wall's books about Anglo-Saxon history, and couple of books about the Viking age and the Roman era too.

12) What are you currently reading:

Artificial Condition, bu Martha Wells, and Irish History by Neil Hegarty.

13) What are you planning on reading next?

Feet of Clay by Terry Pratchett. And a lot, lot more lol...

I tag... @baepsae-7, @andordean, @mass-convergence, @kelenloth, @ramblesanddragons and anyone who would want to try! But no pressure if you don't have the time!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some days arrive with what feels like hope

and the sky bleeds gold like a flame.

-Mark Wunderlich

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Trick” by Mark Wunderlich, The Anchorage

378 notes

·

View notes

Text

That we were born suffering, but that we are not meant to suffer. That the wind blows and the birches outside my window sing a little.

- Mark Wunderlich, "Proposition" from God of Nothingness

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

This year I did not love the first snow

From "First, Chill" by Mark Wunderlich

0 notes

Note

Do you have any queer book recs? Fiction, nonfiction, poetry... I’ll take anything really 😅

I do!

I’ll put my queer fiction/fantasy, nonfiction, and poetry recs below the cut.

Fiction/Fantasy

Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Sáenz

One of my all-time favorite books. Ever. Seriously, I’ve read it so many times I could probably quote parts back to you. It reads like poetry with a beautiful story and happy ending. It’s about two teenage boys in El Paso, Texas who become friends and eventually more. The author himself is also gay.

There’s also a sequel, Aristotle and Dante Dive into the Waters of the World, coming later in 2021

Carry On by Rainbow Rowell

I think one of the reasons I like this book (and series) is because it reads like fanfiction. That’s probably because it... kind of is! It’s a similar universe to Harry Potter, with a magical boarding school and a “chosen one” who needs to defeat an antagonist. But there’s also a lot more narrators, funny snark, and gay makeouts.

This is part of a series. Wayward Son is the second book, and the third book, Any Way the Wind Blows, is coming in July 2021.

Captive Prince by C.S. Pacat

Again, I think one of the reasons I love this series so much is because it reads like fanfiction. And that’s probably because it was originally posted on LiveJournal!

It’s official summary is: “Damen is the true heir to the throne, but when his half brother seizes power, Damen is captured, stripped of his identity and sent to serve the Prince of a rival nation as a pleasure slave.” But IMO it’s so much more than this. This series is fascinating and intriguing and I couldn’t put it down.

Warnings for a shitton of unresolved sexual tension and several explicit scenes, including noncon.

This is part of a trilogy. Here is the second book, The Prince’s Gambit, and the third is Kings Rising.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

This book is a letter from a son in his late 20s to a mother who can’t read. It’s beautifully written and heartbreaking and a wonderfully brutal look at race, class, masculinity, and family.

Ocean Vuong is also a poet, and it definitely shows in his writing in the best way.

Nonfiction

When Brooklyn Was Queer by Hugh Ryan

I bought this as a Stucky fan to help my own fic writing, but came to love it for so many other reasons too. It’s an amazingly researched look into the queer history of Brooklyn, New York spanning the 1850s through the late 1900s. It’s full of just as many funny stories as heartbreaking ones, and was riveting the whole way through (as well as giving me a much-needed education for my writing).

This Book Is Gay and What’s The T? by Juno Dawson

I got these books when I was starting to exploring my gender and sexuality. They’re very informative and easy to read, and were a wonderful resource for my parents to learn about the lgbt+ community after I came out. Since then, I’ve used them in my sex-ed classes and recommended them to many queer teen and parent groups I’ve been asked to speak at.

To give you a taste, some of the chapters in This Book Is Gay are “Where to Meet People Like You”, “The Ins and Outs of Gay Sex”, and “Stereotypes Are Poo.” The author herself is also trans.

Poetry

Crush and War of The Foxes by Richard Siken ( @richardsiken-poet )

If you are gay, on tumblr, or in fandom, there’s probably a 99% chance you’ve heard of or read something by Richard Siken. Both of these books are full of impactful words and beautiful (and sometimes horrible but still beautiful) imagery. I have yet to find any other poet that comes close to his unique brand of poetry.

Please, The Tradition, and The New Testament by Jericho Brown

Please focuses on love and violence, and has become one of my favorite books of poetry.

The Tradition deals with how we’ve become accustomed to fear and terror in all aspects of life - bedroom, classroom, workplace, the movie theater... His poems discuss everything from mass shootings, rape, police brutality, and homophobia, and it’s a beautiful book.

The New Testament is more about examining race, masculinity, and sexuality in the context of religion. It’s a wonderful look at life, death, rituals, good and bad, shame, and culture.

The Anchorage and Voluntary Servitude by Mark Wunderlich

The Anchorage is a beautiful collection of poems that all seem to relate to each other in a web of repeated details and voice. It’s split into four sections and takes you on a journey when you read it altogether.

Voluntary Servitude is largely about love, sex, betrayal, family, and heartbreak. It’s full of strong imagery and beautiful words. I would put this, Crush by Richard Siken, and Please by Jericho Brown into the same category. I absolutely love them all.

Collected Poems by Thom Gunn

This is a big book of most of Thom Gunn’s poetry and includes his books Fighting Terms, My Sad Captains, Jack Straw’s Castle, Touch, The Man With Night Sweats, and more. It covers many subjects throughout his life and career including HIV/AIDS. He’s heavy on and more formal with meter than some other poets, so if you like that, give it a try!

Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong

Another from Ocean Vuong! This one is a poetry collection that looks at everything from love, romance, and family to memory, grief, and war. It’s also beautifully gentle, and I’m always left stunned by his words.

#book recommendations#queer books#queer poetry#queer fiction#lgbt poetry#lgbt books#lgbt fiction#benjamin alire sáenz#rainbow rowell#c.s. pacat#ocean vuong#hugh ryan#juno dawson#richard siken#jericho brown#mark wunderlich#thom gunn#my posts

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

A wander through Rhymney Street over Easter break by Macy White

As I embark on my sociological exploration of Cathays’ bustling streets, I am drawn to the materiality of place - the tangible expressions of urban life that shape our interactions and perceptions. Descending the steps from Crwys Road reveals a resplendent display of graffiti, injecting bursts of colour into the otherwise monotonous thoroughfare. Traversing the alleyway, the urban sounds emanating from Crwys Road gradually fade, signalling my departure from the commercial hub and entry into the place of my inquiry: Rhymney Street. Negotiating the scattered remnants of commercial consumption strewn across the pavement (Puwar 2019), I keenly feel the absence of the usual student energy that permeates this space. As Easter break unfolds and the students vacate, a quietude settles, allowing me to experience the changing temporal rhythms of this space. Conceptualising the street as a dynamic entity, shaped by cultural expressions and diverse mobilities (Hubbard and Lyon 2018), I delve into uncovering the ‘co-production of lives and landscape’ (Knowles 2011, p.137). Walking becomes my tool for immersion in the representational and lived world (Wunderlich 2008, p.125), facilitating an exploration of the essence of being in place (O’Neil and Hubbard 2010).

I embrace the flâneur, or rather the flâneuse - a wandering existence that combines elements of ‘reportage and poetique’ (Gantz 2005, pp.150- 152). In my walk, marked by its fluctuating pace and rhythm, I strive to align with the inherent rhythms of place, consciously ‘urban roaming’ (Rendell 2003, p.230 in Wunderlich 2008) to explore the landscape materially, physically, and sensually. Much like the 'discursive walk’, it transcends mere destination, inviting immersion in the journey itself (Wunderlich 2008, pp.132-133).

Turning left onto Rhymney Street, the absence of students, typically omnipresent in this lively enclave of Cathays, is palpable. The street, usually pulsating with youthful energy, now lies eerily quiet. Without their presence, the essence of the street transforms, and I sense the emptiness around me, discerning the absence of fellow pedestrians (Degen 2008). As I traverse its length, I am enveloped in an ‘intense sensuous encounter’, each step shaping my embodied experience and perception of the streetscape (Degen 2008, pp. 3-5). The transition beneath my feet, from rough concrete steps to smooth tiny concrete squares creates a ‘reciprocal and body-bound exchange with the environment’ (Wunderlich 2008, p.126). The air, devoid of the usual cacophony of voices, carries a stillness only broken by the distant hum of traffic echoing from Crwys Road. Navigating the street unencumbered by the usual obstacle course of debris and litter, I am struck by the unfamiliar tranquillity. It’s an unusual sensation, walking along a street typically alive with fellow students, now deserted. The pavement, usually a bustling thoroughfare, now bears witness to my lone walk (Rose 2020), its surface worn by the countless footsteps that have traversed it. Amidst the quietude, a blossom tree captivates my gaze, its petals scattered like confetti in a celebration of spring’s arrival. Stepping onto the road, I’m drawn by the ethereal beauty of the blossoms, their vivid hues contrast the usual sight of litter-strewn pavements. The fragrance of spring fills my nose, a refreshing departure from the usual odours of exhaust and decay. Blossoms carpet the ground, untouched and undisturbed. As my gaze follows the meandering path of the road, its unconventional zigzag design symbolises the intricate dance of spatial negotiation it represents. The narrowness of the street presents challenges for various forms of mobility, each encounter requiring a dance of movement and direction. Today, however, is different - allowing me to move freely. Returning to the narrow path, I contemplate the dynamics of access and mobility that define this space, pondering the diverse ways in which we perform in urban space (Amin and Thrift 2002; Wunderlich 2008).

Moving along the stream of Victorian terrace houses, the sight of vacant parking spaces saturates the landscape, a clear indicator of the residents' temporary absence. Each empty slot stands as a silent testament to the usual vibrancy, now momentarily subdued. A few cars linger, their ownership a mystery amidst the desolate scene. Nearby, a lone pigeon pecks at the pavement, its rhythmic bobbing a solitary dance amidst the stillness. Having traversed this path countless times, I’ve observed how the space is a product of human activity, where the lively rhythms of student life imbue this space as inherently social in its construction and interpretation (Lefebvre 1991). Yet today, the absence of students renders the street eerily tranquil. Noticing the absence of food bins, typically present after bin collection, I am struck by the street’s newfound pristineness, unencumbered by the remnants of urban life. Sunlight filters through the clouds, casting elongated shadows across the pavement, accentuating the architectural intricacies of the surrounding houses. With each step, I engage kinaesthetically, attuned to the rhythm of my own movement and the surrounding environment (Wunderlich 2008). My breathing slows in harmony with the leisurely pace of my urban stroll, while my footsteps echo the unhurried tempo of the street’s dynamic. The atmosphere unfolds with a subdued rhythm of its own, the usual clamour of activity now replaced by a serene ambiance. Delving deeper into the sensory tapestry of nature, I hear the gentle rustle of the leaves, the occasional chirp of a passing bird, inviting introspection and contemplation of the city. The warm caress of sunlight on my face adds to the pleasure of the walk, casting a glow over the streetscape. As I exchange a smile with a fellow student passing by, I am struck by the serenity that surrounds us. In this moment, we are the sole occupants of this street, a rare occurrence in this part of the city. I am reminded of my own embodiment, the familiarity of the encounter, the shared understanding of navigating these streets as students, creating a sense of connection without interaction (Neal et al. 2015). As our paths briefly intersect, I reflect on the temporal dimension of student life. The ebb and flow of the academic calendar define and shape not only our existence but also the rhythms of the city.

Walking along, I approach the bridge spanning over the adjacent train tracks, its steel arches stretch like a symbolic gateway connecting this student-centric streetscape to the vibrant allure of City Road. As I gaze upon it, thoughts of the diverse inhabitants of this city flood my mind, where the city serves as a conduit for connection. This ‘two-way encounter between mind and the city’ (Lefebvre 1996, pp.104-111) reminds me that I’m not solely in a student landscape but rather in a multicultural urban metropolis (Watson 2016). An older man descends the bridge onto Rhymney Street. He carries food shopping bags, their weight causing his shoulders to droop slightly, a testament to the practicalities of everyday urban life. The subtle nod of his head, dictated by the rhythm of his music, suggests a detachment from the external urban world, lost in the melodies playing through his headphones to drown out the city’s noise (Back 2017). Despite the absence of the usual energy that permeates this space, his presence enriches the street’s dynamic rhythms, adding depth to its urban symphony. As he moves ahead, I’m reminded of the interconnectedness of people and the myriad stories woven into these fluid and ever-changing streets (Hubbard and Lyon 2018), embodying the ‘intricate ballet’ of urban life - a choreography of pedestrian movements and social interaction (Jacobs 1961, p.65). A car passes by its zigzagging motion echoing the street’s unconventional design, momentarily startling me with its disruption. Music blares from its speakers, briefly drowning out the rare ambient sounds of the street. In the distance, a group of older adults stroll leisurely, their laughter and animated conservation filling the air. As the car fades into the distance and the laughter of the group recedes, I’m reminded of the array of human experience that animate the city streets.

Wandering along, I’m drawn into the unique narratives ingrained into each property, like a curious observer unravelling the mysteries woven into their walls. These houses, though aged, each tell a diverse story: some have been modernised or re-vitalised with vibrant coats of paint, while others wear their age with dignity, their earthy-toned exteriors hinting at decades of history. Rhymney Street stretches out before me, its length a reminder of the multitude of stories that intersect and intertwine along its path. The homes wear the marks of their inhabitants, from the eclectic display of empty alcohol bottles to the colourful tapestries distinguishing one dwelling from the next. Amidst the mosaic of houses, a bright sky-blue residence catches my eye, its vibrant cheerful hue radiating a welcoming aura. Verdant plants grace its windows, their leaves glistening in the gentle sunlight that filters through. Three empty gin bottles, repurposed as candle holders, stand as quirky ornaments, their colourful wax sticks casting a playful glow. Fairy lights drape elegantly, their soft illumination dancing against the drawn curtains. This dwelling radiates a sense of belonging, a visual testament to the thriving community that calls these walls home. This way of walking to learn the city (Back 2017) unveils the intricate intermingling of the senses that transcend the body, inviting us to observe and grasp the essence of place (Amin and Thrift 2002). As the sun dips behind the cloud, casting a shadow over the street, the pattern of drawn curtains and the absence of lights hint at the departure of these residents, revealing the temporal nuances encountered along the way.

Arriving at the end of Rhymney Street, I’m greeted by a vibrant tableau. This segment of the street, leading directly to the nearby ‘student’ pubs, pulsates with vitality and motion. Cars squeeze into filled parking spaces, creating a patchwork of haphazard arrangements along the path. The houses exude a sense of occupancy, curtains drawn open and lights on, imbuing the area with life. Ahead, three young people emerge from their house, one recoiling in disgust at the sight of open food bags strewn by their doorstep, with a screechy ‘eww’. They deftly navigate the obstacle course of debris with a rhythmic sidestep, sharing laughter as they go. Continuing my walk, the sounds of laughter, conversation, and music drift from the nearby houses, filling the air with a lively energy. The shift in ambiance is striking, with a vibrant vitality animating the landscape. Diverse individuals move along the street, using it as a thoroughfare to access the nearby commercial activity, intertwining place, journey, and people (Knowles 2011). In the absence of the usual student rhythms, other groups of individuals emerge, their presence becoming more visible against the backdrop of the urban setting. As I approach the street’s end, I peer over the boundary wall, absorbing the diverse tapestry of urban life below. Cars stop and accelerate, engines humming. Pedestrians hurry along the pathways, their strides embodying a ‘purposive walk’ of constant rhythmic and rapid pace (Wunderlich 2008, p.131). Deliveroo bikes dart through the traffic with purpose and urgency. The cacophony of movement and the scent of exhaust amalgamate through my embodied perception, mediating my sense of place (Degen 2008, pp. 4-6). The array of mobilities enrich the urban rhythms of Cathays, reaffirming that urban life is everywhere and in everything (Amin and Thrift 2002). Standing still, I’m struck by the contrast that while Rhymney Street rests, the urban city continues to pulse with urban rhythmicity – it never sleeps (Smith and Hall 2013). Turning around to admire the length of Rhymney Street, its expansive stretch reveals it as more than just a thoroughfare – it’s a social hub with its own unique cast of characters, embodying ‘the shifting social and cultural terrains of urban life’ (Barker 2009, p.155). I reflect how the return of students will transform the streets’ dynamic again, where everyday life redefines the polyrhythms (Smith and Hall 2013) and materiality of place. Turning to leave, the yellow double lines of the street stretch out before me like a guiding beacon, bidding farewell to Rhymney Street as I re-join the rhythm of urban life, journeying back into the heart of the city.

Methodological Note

The ‘rhythm of walking generates a rhythm of thinking’ (Solnit 2001, p.5), where mind, body, and the sensory stimuli of place coalesce (Ingold and Lee Vergunst 2016; Springgay and Truman 2017). Walking serves as a mediated and constructed pathway, imbued with kinaesthetic richness, guiding our exploration of place by sensitising our bodies to the phenomenological processes of existence (Solent 2001; Wunderlich 2008; O’Neil and Hubbard 2010). For Knowles (2011, p.136), these journeys provide imaginative tools to delve into the ‘fabric and fabrication of cities’, offering insights into the idiosyncratic construction of lived experience and place. As described by Ingold, they constitute an ‘improvised matrix of movement’ connecting physical spaces with the social practices that shape them (2000, pp. 220-226). This fluidity and interconnection inherent in walking affords a deeper understanding of the multifaceted processes through which landscapes are formed, experienced, valued, and contested (Watson 2006; Macpherson 2016). City walks, with their capacity to stimulate new perspectives and narratives, peel back the layers of overlapping social, historical, and contested materialities woven into the urban tapestry. This way of engaging with the city ‘from below’ (Back 2014), provides a means to explore the multi-temporality, rhythmicity, and socio-sensory processes of the landscape (Amin and Thrift 2002).

My reflexive journey aimed to contextualise the diverse mobilities and urban rhythms of the streetscape by juxtaposing them with my previous experiences. Using walking to tap into the ‘sociological imagination’ (Mills 1959), I observed in-situ how the influx of students shapes the social, material, and physical landscape. Immersing myself in the sounds, smells, and sights of my journey fostered an embodied ‘phenomenological sense of place’ (Pink 2008, p.178), deepening my personal connection to the city. My walk intended to uncover the stories and histories woven within the streetscape while remaining attuned to the ‘music of the city’ (Lefebvre 1996, p.227). The rhythms of the city serve as the coordinates through which individuals frame and organise their urban experiences (Amin and Thrift 2002, p.17). By examining cities through the journeys that traverse them (Knowles 2011), we can unveil the intricate interplay of urban dynamics, cultural expressions, and spatial configurations that flow through and define city life. The infrastructure of Rhymney Street dictated my pace; its long, linear layout, devoid of the usual pedestrian flows, allowed me to pause, reflect, and freely navigate the streetscape without conforming to its typical rhythms. By acknowledging the fluidity of urban representation (Knowles 2011), I aimed to capture the evolving essence of urban existence through employing a ‘literary sociology’ approach, embracing writing that mirrored the creativity and fluidity inherent in the walk itself (Back, 2007, p. 164). My student identity and familiarity with the city are significant, as they provided context-specific knowledge about its identity and connection to the student community. This reinforced my sense of belonging and identity, influencing my experience, perspective, and interpretation. Focusing on the street as a synecdoche for the city (Amin and Thrift 2002), I sought to uncover how the streetscape comes alive, is lived in, and moves with the rhythm of urban life.

References

Amin, A., Thrift, N.J. 2002. Cities: reimagining the urban. Cambridge: Polity.

Back, L. 2007. The art of listening. New York, Ny; Bloomsbury Academic.

Back, L. 2014. Reflections: Writing cities. In: Jones, H. and Jackson, E. 2014. Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging: Emotion and Location. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Back, L. 2017. Memory, City Life and Walking. In: Bates, C. and Rhys-Taylor, A. eds. Walking Through Social Research. London: Routledge, pp. 20-37.

Barker, J. 2009. Introduction: Street Life. City & Society 21(2), pp. 155–162.

Degen, M. 2008. Sensing cities: regenerating public life in Barcelona and Manchester. London; New York: Routledge.

Gantz, K. 2005. Strolling with Houellebecq: The Textual Terrain of Postmodern “Flânerie.” Journal of Modern Literature 28(3), pp. 149–161.

Hubbard, P., Lyon, D. 2018. Introduction: Streetlife – the shifting sociologies of the street. The Sociological Review 66(5), pp. 937–951.

Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books. Lee Vergunst, J., Ingold, T. 2016. Ways of Walking. Routledge. Knowles, C. 2011. Cities on the move: Navigating urban life. City 15(2), pp. 135–153. Lefebvre, H. 1996. Writings on Cities. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 147–159.

Mills, C.W. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford University Press.

Neal, S., Bennett, K., Jones, H., Cochrane, A., Mohan, G. 2015. Multiculture and Public Parks: Researching Super-diversity and Attachment in Public Green Space. Population, Space and Place 21(5), pp. 463–475.

O’Neill, M., Hubbard, P. 2010. Walking, sensing, belonging: ethno-mimesis as performative praxis. Visual Studies 25(1), pp. 46–58.

Pink, S. 2008. An urban tour: The sensory sociality of ethnographic place-making. Ethnography 9(2), pp. 175–196.

Puwar, N. 2019. Walking through Litter – Life Writing Projects. Available at: https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/lifewritingprojects/place/nirmal-puwar/ [Accessed: 15 April 2024].

Rose, M. 2020. Pedestrian practices: walking from the mundane to the marvellous. In: Homes, H., Hall, S.M. Mundane Methods: Innovative ways to research the everyday. Manchester: University Press.

Smith, R.J. and Hall, T. 2013. No Time Out: Mobility, Rhythmicity and Urban Patrol in the Twenty-Four-Hour City. The Sociological Review 61(1), pp. 89–108.

Watson, S. 2006. City publics: the (dis)enchantments of urban encounters. London: New York: Routledge.

Watson, S. 2016. Making multiculturalism. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40(15), pp. 2635–2652.

Wunderlich, F.M. 2008. Walking and Rhythmicity: Sensing Urban Space. Journal of Urban Design 13(1), pp. 125–139.

0 notes

Text

Winter Study by Mark Wunderlich

Two days of snow, then ice and the deer peer from the ragged curtain of trees.

Hunger wills them, hunger pulls them to the compass of light

spilling from the farmyard pole. They dip their heads, hold

forked hooves above snow, turn furred ears

to scoop from the wind the sounds of hounds, or men.

They lap at a sprinkling of grain, pull timid mouthfuls from a stray bale.

The smallest is lame, with a leg healed at angles, and a fused knob

where a joint once bent. It picks, stiff, skidding its sickening limb

across the ice's dark platter. Their fear is thick as they break a trail

to the center of their predator's range. To know the winter

is to ginger forth from a bed in the pines, to search for a scant meal

gleaned from the carelessness of a killer.

#Mark Wunderlich#poetry#x#all wild animals were once called deer#a northern country#you cannot escape the landscape#winter#ice

1 note

·

View note

Text

#literary quotes#bennington college#bennington mfa program#mark wunderlich#poets#poetry community#poem

3 notes

·

View notes