#mark twain boat

Text

The Mark Twain River Boat A Disneyland Original | Full Ride POV | 2022

The Mark Twain River Boat A Disneyland Original | Full Ride POV | 2022

View On WordPress

#Disney#Disney Parks#Disneyland#disneyland 2022#disneyland california#Disneyland History#disneyland mark twain#Disneyland Park#Disneyland Resort#disneyland rides#disneyland rivers of america#disneyland vlog#mark twain#mark twain boat#mark twain disneyland#mark twain river boat#mark twain riverboat#mark twain riverboat disneyland#opening day ride at disneyland#riverboat#Rivers of America#rivers of america disneyland#tom sawyer#Walt Disney#Walt Disney World

0 notes

Video

undefined

tumblr

Silent 8mm home move, August 1966

#vintage disneyland#disneyland#disneyland california#main street usa#sleeping beauty castle#house of the future#matterhorn#storybook land canal boats#chicken of the sea pirate ship#jungle cruise#rivers of america#mark twain riverboat#dlrr#disneyland railroad#indian village#monorail#submarine lagoon#skyway#it's a small world#iasw#e: 60s#video#*mp

126 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mark Twain and entourage docked in Seattle aboard the U.S.S. Mohican, August 13, 1895. Photo by James Pond

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thinking about how self sacrificial Kunikida got me thinking that oh yeah Atsushi definitely takes after him in that aspect too.

There's Atsushi's entrance exam with him shielding everyone from a bomb he thought was real.

Atsushi was told to run during the first fight with Akutugawa in the alley, by Junichiro and Atsushi stayed.

The time he tried to leave the Agency in season 1 because didn't want the Agency to keep being targeted by the Port Mafia because of him.

If the Black Lizards had gone after Atsushi rather than raid the Agency, the plan would've worked too.

Atsushi jumped out of a moving train with Kyouka, who had a bomb strapped to her chest. He also went back for Kyouka on the burning cargo boat to save her.

Atsushi let himself get captured by Fitzgerald. He fell from the Moby Dick to the ground, running as Mark Twain sniped at him. Got his legs shot to the point he couldn't walk.

And still tried to reach for Q's doll.

Atsushi stowed back onto the Moby Dick to save all of Yokohama. He got infected by the Cannabalism ability and began fighting Ivan.

Atsushi was terrified but he was prepared to fight Fukuchi alone on the boat, even when he had no chance of winning.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Letter From Mark Twain to Nikola Tesla

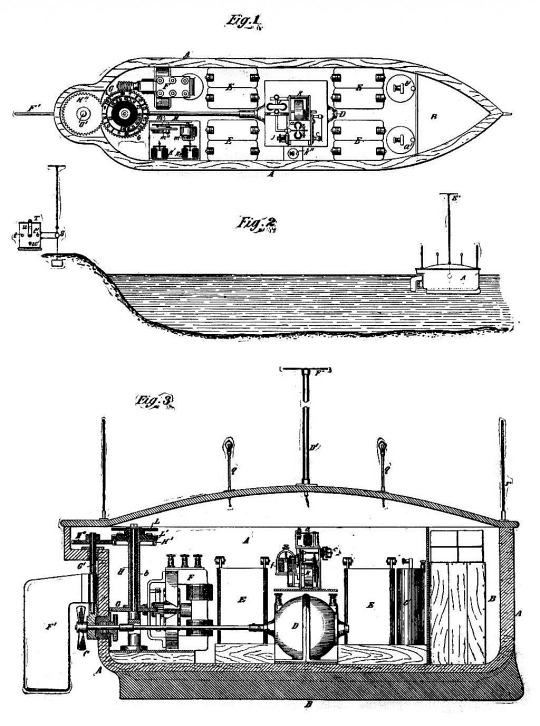

On November 8, 1898, Nikola Tesla made a public announcement of his wirelessly-controlled boat the same day his U.S. Patent was granted to him. Wireless was still very much in its infancy, so the announcement was beyond the comprehension of the layperson. Tesla described his invention as having many uses, including wirelessly controlled boats, vehicles, or aerial devices of any suitable kind to be used as life dispatch, or for carrying letters, packages, or other provisions. It could also make it easier to establish communication with inaccessible regions and explore such regions in the same, and for many other scientific, engineering, or commercial purposes. But the greatest value of his invention was its possible use in warfare for, for his own reason, it had certain and unlimited destructiveness. He could load a boat with explosives and direct it toward any enemy, and by the sheer destructive effect, he would force the opposition in retreat.

On November 17, 1898, Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, wrote a letter to Tesla regarding his wireless-controlled boat:

Dear Mr. Tesla

Have you Austrian & English patents on that destructive terror which you have been inventing?—& if so, won't you set a price upon them & commission me to sell them? I know cabinet ministers of both countries—& of Germany, too; likewise William II.

I shall be in Europe a year, yet.

Here in the hotel the other night when some interested men were discussing means to persuade the nations to join with the Czar & disarm, I advised them to seek something more sure than disarmament by perishable paper invite the great inventors to contrive something against which fleets and armies would be helpless & thus make war thenceforth impossible. I did not suspect that you were already attending to that, & getting ready to introduce into the earth permanent peace & disarmament in a practical & mandatory way.

I know you are a very busy man, but will you steal time to drop me a line?

Sincerely yours,

Mark Twain

#nikola tesla#science#history#remote control#radio#technology#mark twain#Samuel Clemens#quotes#ahead of his time#ahead of our time

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disneyland's keel boat Gullywhumper, 1964.

The Gullywhumper faithfully plied the Rivers of America around Tom Sawyer's Island for 42 years until one evening in May 1997, when the boat began to rock side to side. It capsized, dumping a full boatload of passengers into the river, leaving several with minor injuries. The boat was removed for inspection and neither it nor its companion craft the Bertha Mae returned for operation.

Instead, the Gullywhumper returned to Rivers of America as a prop and was moored on Tom Sawyer Island where passengers on the Davy Crockett Canoes, the Sailing Ship Columbia, and the Mark Twain Riverboat could see it while passing. Eventually, hull damage caused the boat to flood and sink, and it was finally removed from Disneyland in April 2009.

#vintage#Mike Fink's Keel Boats#1960s#amusement park#attraction#passengers#60s fashions#Frontierland#New Orleans Square#Bear Country#Disney

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 110: Ghost Writers in A.I. (featuring Michael Swaim)

On this week's episode, Cody and Garth are joined once again by Michael Swaim of Small Beans! Together they discuss the time a famous author wrote a book posthumously. That's right! It's actual ghost writers! They also discuss Michael's new book, The Climb and delve into the philosophical ramifications of generative A.I. on the world of artists and creators. So grab your Ouija™ boards, fire up the chatbots, and crack a few glo-sticks, it's about to get weird.

Thanks for joining the boys again, Michael! Please check out Michael Swaim's new memoir, The Climb, and the comic Michael and Garth made, One Last Job!

Check out the images below discussed in this week's episode and please come join the episode discussion on the Least Haunted Discord!

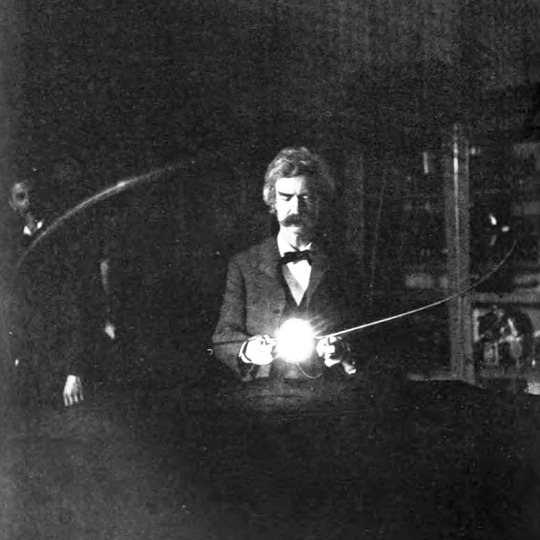

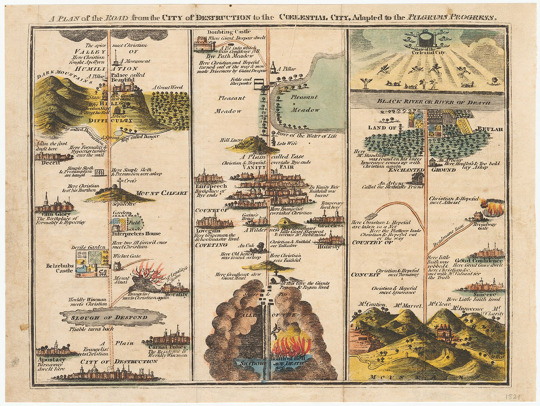

Samuel Langhorne Clemens a.k.a Mark Twain (1835-1910)

A steam powered River Boat, much like Mark Twain piloted in the 1850's.

Young Sam Clemens as a young typesetter's apprentice

Original 1901 Oujia™ Board

Pearl Lenore Curran, the medium who communicated through Ouija™ board with the "spirit" of Patience Worth- a girl who supposedly lived in the 1600's - to write a series of novels and collections of poetry.

Emily Grant Hutchings, (1870-1960), friend of Pearl Lenore Curran, and St. Louis journalist. She was present at the Patience Worth Ouija™ sessions. In 1916 she, her husband, and medium Ms. Hays used a Ouija™ to communicate with the "spirit" of Mark Twain©.

The book, Jap Herron by Mark Twain, as communicated through the Oujia™ Board.

#leasthaunted#michael swaim#mark twain#podcast#funny#ghosts#ghost writing#paranormal#podcasts#skeptics#ouija#ouija board#small beans

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

This one’s pretty extensive, so bear with me: If you were trapped on a deserted island (that includes like, a forest, and stuff, ofc) for an indefinite amount of time with no supplies nor anything else directly (or indirectly) necessary for survival…which three people would you bring with, and why? Also, how would you try and get off of it?

That's a very interesting question.

Can I choose any three people? Or do I have to choose people whom I know? Because if I could choose anyone I'd definitely say someone who had some type of experience in hostel environments. You know, like a fur trapper or frontiersman. Maybe Mark Twain. He's not a fur trapper or anything but I feel as though he'd be useful. Hermann Melville too (although he's dead...)

If I have to choose people that I know, of course I'd never want any of my friends to be trapped on a deserted island somewhere, but I'd say Jack first of all. He's, well... he's Jack, y'know? If anyone could figure a way off a deserted island it's him. And I think it'd make me feel better if he was there... Then I'd choose Mush because he'd keep our spirits up and also he's always noticing things, and that could be helpful. Plus I think he'd get a kick out of being on an island. And maybe Jake. He and his parents had a farm before they moved into the city, so he'd know about plants and things.

As for how we'd get off the island, I suppose logically we'd need a boat. Which is unfortunate because I get seasick...

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yandere Mark Twain idea

alright so I had an idea, Mark with a darling from his hometown, they grew up together, or maybe met in high school or whatever. Mark and his darling were friends before he joined the guild, but when Mark joined his darling started to distance themselves from him . They knew about the guild and they began to question if their friend were as good as he appeared to be before. The darling went off, moved away from their hometown, continued on with their life away from Mark… or so they thought.

He would be watching from a distance while working for the guild. Then he got word that he was being sent off Japan, he can’t just leave you alone without someone to watch over you but he knows you will not come with him willingly. He spends hours stressing about this. Then he gets an idea, he asks Fitzgerald for permission and of course Fitzgerald approves. So when you’re walking back to your apartment… and BANG! You feel a sharp pain in the back of your head and the pain is enough for you to fall to the ground and your head hits the concrete and knock you out.

The next thing you know you’re walking up in a strange room… there is a strange rocking with the room… a boat? Before you can ponder it anymore, Mark, who was sitting on a chair next to the bed you laid on, was dotting over you, telling you not to get up and just relax. He explained that he had to take you with him to Japan on this mission for your own safety, don’t worry, you’ll have everything you could ever want. Hey! Don’t cry, he did this for you after all.

“Oh you’re away doll! Hey, hey, hey, don’t get up, there is a sizable bruise on the back of your head from that rubber bullet I used. Atta girl, just lay down, I’ll take care of you.”

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

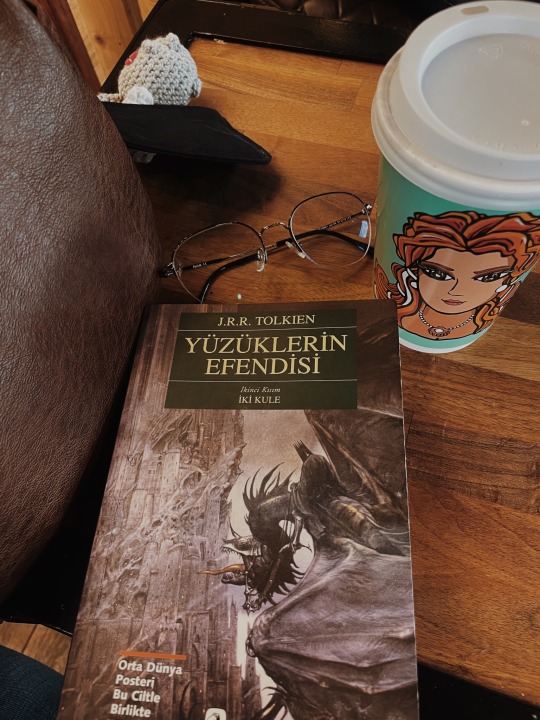

days 16-22 of my reading challenge!:

are you ready people? it’s gonna be a wild ride as i have been reading but not been able to post. here we go!

16. do you like to read poetry? if so, share your favorite poem with us.

please check previous post people, thank you<3.

17. what do you like to drink while reading?

almost any type of coffee and turkish tea.

18. which book made you cry your eyes out?

the song of achilles and i cried so much while reading the deathly hollows.

19. which book made you laugh the most?

man i need to find their english names. wait a min please. ok, i’m back. the dairies of adam and eve by mark twain and three men in a boat by jerome k. jerome.

20. share a moment from a book where you had to put the book down and take a deep breath.

i’ll give an example from the last couple of days. when i started reading the second book of lotr, the two towers, i had to put the book down and take a deep breath because i almost started crying in the subway when i read aragorn mourning for boromir.

21. which book did you expect to hate but ended up being obsessed with it?

after being disappointed by shadow and bone triology, i thought i wouldn’t like the crows but i was wrong. i had a very short bardugo phase but do not forget that i’ll always be a malyen girl. and maybe matthias.

22. is there a book you just can’t stop reading again and again.

cemile by cengiz aytmatov. is it available in english? lemme check because i think you should read it. no. i am: disappointed.

*deep breath* and scene! thank you for reading if you actually read the whole post. <3

#readingwithlunlun#reading challenge#reading aesthetic#reading alcove#reading books#book reading#reading#books#book#booklr#bookblr#bookstores#new books#bookworm#studying#studyspo#lunlunreads

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Edward Schlosser

Published: Jun 3, 2015

I’m a professor at a midsize state school. I have been teaching college classes for nine years now. I have won (minor) teaching awards, studied pedagogy extensively, and almost always score highly on my student evaluations. I am not a world-class teacher by any means, but I am conscientious; I attempt to put teaching ahead of research, and I take a healthy emotional stake in the well-being and growth of my students.

Things have changed since I started teaching. The vibe is different. I wish there were a less blunt way to put this, but my students sometimes scare me — particularly the liberal ones.

Not, like, in a person-by-person sense, but students in general. The student-teacher dynamic has been reenvisioned along a line that’s simultaneously consumerist and hyper-protective, giving each and every student the ability to claim Grievous Harm in nearly any circumstance, after any affront, and a teacher’s formal ability to respond to these claims is limited at best.

What it was like before

In early 2009, I was an adjunct, teaching a freshman-level writing course at a community college. Discussing infographics and data visualization, we watched a flash animation describing how Wall Street’s recklessness had destroyed the economy.

The video stopped, and I asked whether the students thought it was effective. An older student raised his hand.

”What about Fannie and Freddie?” he asked. “Government kept giving homes to black people, to help out black people, white people didn’t get anything, and then they couldn’t pay for them. What about that?”

I gave a quick response about how most experts would disagree with that assumption, that it was actually an oversimplification, and pretty dishonest, and isn’t it good that someone made the video we just watched to try to clear things up? And, hey, let’s talk about whether that was effective, okay? If you don’t think it was, how could it have been?

The rest of the discussion went on as usual.

The next week, I got called into my director’s office. I was shown an email, sender name redacted, alleging that I “possessed communistical [sic] sympathies and refused to tell more than one side of the story.” The story in question wasn’t described, but I suspect it had do to with whether or not the economic collapse was caused by poor black people.

My director rolled her eyes. She knew the complaint was silly bullshit. I wrote up a short description of the past week’s class work, noting that we had looked at several examples of effective writing in various media and that I always made a good faith effort to include conservative narratives along with the liberal ones.

Along with a carbon-copy form, my description was placed into a file that may or may not have existed. Then ... nothing. It disappeared forever; no one cared about it beyond their contractual duties to document student concerns. I never heard another word of it again.

That was the first, and so far only, formal complaint a student has ever filed against me.

Now boat-rocking isn’t just dangerous — it’s suicidal

This isn’t an accident: I have intentionally adjusted my teaching materials as the political winds have shifted. (I also make sure all my remotely offensive or challenging opinions, such as this article, are expressed either anonymously or pseudonymously). Most of my colleagues who still have jobs have done the same. We’ve seen bad things happen to too many good teachers — adjuncts getting axed because their evaluations dipped below a 3.0, grad students being removed from classes after a single student complaint, and so on.

I once saw an adjunct not get his contract renewed after students complained that he exposed them to “offensive” texts written by Edward Said and Mark Twain. His response, that the texts were meant to be a little upsetting, only fueled the students’ ire and sealed his fate. That was enough to get me to comb through my syllabi and cut out anything I could see upsetting a coddled undergrad, texts ranging from Upton Sinclair to Maureen Tkacik — and I wasn’t the only one who made adjustments, either.

I am frightened sometimes by the thought that a student would complain again like he did in 2009. Only this time it would be a student accusing me not of saying something too ideologically extreme — be it communism or racism or whatever — but of not being sensitive enough toward his feelings, of some simple act of indelicacy that’s considered tantamount to physical assault. As Northwestern University professor Laura Kipnis writes, “Emotional discomfort is [now] regarded as equivalent to material injury, and all injuries have to be remediated.” Hurting a student’s feelings, even in the course of instruction that is absolutely appropriate and respectful, can now get a teacher into serious trouble.

In 2009, the subject of my student’s complaint was my supposed ideology. I was communistical, the student felt, and everyone knows that communisticism is wrong. That was, at best, a debatable assertion. And as I was allowed to rebut it, the complaint was dismissed with prejudice. I didn’t hesitate to reuse that same video in later semesters, and the student’s complaint had no impact on my performance evaluations.

In 2015, such a complaint would not be delivered in such a fashion. Instead of focusing on the rightness or wrongness (or even acceptability) of the materials we reviewed in class, the complaint would center solely on how my teaching affected the student’s emotional state. As I cannot speak to the emotions of my students, I could not mount a defense about the acceptability of my instruction. And if I responded in any way other than apologizing and changing the materials we reviewed in class, professional consequences would likely follow.

I wrote about this fear on my blog, and while the response was mostly positive, some liberals called me paranoid, or expressed doubt about why any teacher would nix the particular texts I listed. I guarantee you that these people do not work in higher education, or if they do they are at least two decades removed from the job search. The academic job market is brutal. Teachers who are not tenured or tenure-track faculty members have no right to due process before being dismissed, and there’s a mile-long line of applicants eager to take their place. And as writer and academic Freddie DeBoer writes, they don’t even have to be formally fired — they can just not get rehired. In this type of environment, boat-rocking isn’t just dangerous, it’s suicidal, and so teachers limit their lessons to things they know won’t upset anybody.

The real problem: a simplistic, unworkable, and ultimately stifling conception of social justice

This shift in student-teacher dynamic placed many of the traditional goals of higher education — such as having students challenge their beliefs — off limits. While I used to pride myself on getting students to question themselves and engage with difficult concepts and texts, I now hesitate. What if this hurts my evaluations and I don’t get tenure? How many complaints will it take before chairs and administrators begin to worry that I’m not giving our customers — er, students, pardon me — the positive experience they’re paying for? Ten? Half a dozen? Two or three?

This phenomenon has been widely discussed as of late, mostly as a means of deriding political, economic, or cultural forces writers don’t much care for. Commentators on the left and right have recently criticized the sensitivity and paranoia of today’s college students. They worry about the stifling of free speech, the implementation of unenforceable conduct codes, and a general hostility against opinions and viewpoints that could cause students so much as a hint of discomfort.

I agree with some of these analyses more than others, but they all tend to be too simplistic. The current student-teacher dynamic has been shaped by a large confluence of factors, and perhaps the most important of these is the manner in which cultural studies and social justice writers have comported themselves in popular media. I have a great deal of respect for both of these fields, but their manifestations online, their desire to democratize complex fields of study by making them as digestible as a TGIF sitcom, has led to adoption of a totalizing, simplistic, unworkable, and ultimately stifling conception of social justice. The simplicity and absolutism of this conception has combined with the precarity of academic jobs to create higher ed’s current climate of fear, a heavily policed discourse of semantic sensitivity in which safety and comfort have become the ends and the means of the college experience.

This new understanding of social justice politics resembles what University of Pennsylvania political science professor Adolph Reed Jr. calls a politics of personal testimony, in which the feelings of individuals are the primary or even exclusive means through which social issues are understood and discussed. Reed derides this sort of political approach as essentially being a non-politics, a discourse that “is focused much more on taxonomy than politics [which] emphasizes the names by which we should call some strains of inequality [ ... ] over specifying the mechanisms that produce them or even the steps that can be taken to combat them.” Under such a conception, people become more concerned with signaling goodness, usually through semantics and empty gestures, than with actually working to effect change.

Herein lies the folly of oversimplified identity politics: while identity concerns obviously warrant analysis, focusing on them too exclusively draws our attention so far inward that none of our analyses can lead to action. Rebecca Reilly Cooper, a political philosopher at the University of Warwick, worries about the effectiveness of a politics in which “particular experiences can never legitimately speak for any one other than ourselves, and personal narrative and testimony are elevated to such a degree that there can be no objective standpoint from which to examine their veracity.” Personal experience and feelings aren’t just a salient touchstone of contemporary identity politics; they are the entirety of these politics. In such an environment, it’s no wonder that students are so prone to elevate minor slights to protestable offenses.

(It’s also why seemingly piddling matters of cultural consumption warrant much more emotional outrage than concerns with larger material implications. Compare the number of web articles surrounding the supposed problematic aspects of the newest Avengers movie with those complaining about, say, the piecemeal dismantling of abortion rights. The former outnumber the latter considerably, and their rhetoric is typically much more impassioned and inflated. I’d discuss this in my classes — if I weren’t too scared to talk about abortion.)

The press for actionability, or even for comprehensive analyses that go beyond personal testimony, is hereby considered redundant, since all we need to do to fix the world’s problems is adjust the feelings attached to them and open up the floor for various identity groups to have their say. All the old, enlightened means of discussion and analysis —from due process to scientific method — are dismissed as being blind to emotional concerns and therefore unfairly skewed toward the interest of straight white males. All that matters is that people are allowed to speak, that their narratives are accepted without question, and that the bad feelings go away.

So it’s not just that students refuse to countenance uncomfortable ideas — they refuse to engage them, period. Engagement is considered unnecessary, as the immediate, emotional reactions of students contain all the analysis and judgment that sensitive issues demand. As Judith Shulevitz wrote in the New York Times, these refusals can shut down discussion in genuinely contentious areas, such as when Oxford canceled an abortion debate. More often, they affect surprisingly minor matters, as when Hampshire College disinvited an Afrobeat band because their lineup had too many white people in it.

When feelings become more important than issues

At the very least, there’s debate to be had in these areas. Ideally, pro-choice students would be comfortable enough in the strength of their arguments to subject them to discussion, and a conversation about a band’s supposed cultural appropriation could take place alongside a performance. But these cancellations and disinvitations are framed in terms of feelings, not issues. The abortion debate was canceled because it would have imperiled the “welfare and safety of our students.” The Afrofunk band’s presence would not have been “safe and healthy.” No one can rebut feelings, and so the only thing left to do is shut down the things that cause distress — no argument, no discussion, just hit the mute button and pretend eliminating discomfort is the same as effecting actual change.

In a New York Magazine piece, Jonathan Chait described the chilling effect this type of discourse has upon classrooms. Chait’s piece generated seismic backlash, and while I disagree with much of his diagnosis, I have to admit he does a decent job of describing the symptoms. He cites an anonymous professor who says that “she and her fellow faculty members are terrified of facing accusations of triggering trauma.” Internet liberals pooh-poohed this comment, likening the professor to one of Tom Friedman’s imaginary cab drivers. But I’ve seen what’s being described here. I’ve lived it. It’s real, and it affects liberal, socially conscious teachers much more than conservative ones.

If we wish to remove this fear, and to adopt a politics that can lead to more substantial change, we need to adjust our discourse. Ideally, we can have a conversation that is conscious of the role of identity issues and confident of the ideas that emanate from the people who embody those identities. It would call out and criticize unfair, arbitrary, or otherwise stifling discursive boundaries, but avoid falling into pettiness or nihilism. It wouldn’t be moderate, necessarily, but it would be deliberate. It would require effort.

In the start of his piece, Chait hypothetically asks if “the offensiveness of an idea [can] be determined objectively, or only by recourse to the identity of the person taking offense.” Here, he’s getting at the concerns addressed by Reed and Reilly-Cooper, the worry that we’ve turned our analysis so completely inward that our judgment of a person’s speech hinges more upon their identity signifiers than on their ideas.

A sensible response to Chait’s question would be that this is a false binary, and that ideas can and should be judged both by the strength of their logic and by the cultural weight afforded to their speaker’s identity. Chait appears to believe only the former, and that’s kind of ridiculous. Of course someone’s social standing affects whether their ideas are considered offensive, or righteous, or even worth listening to. How can you think otherwise?

We destroy ourselves when identity becomes our sole focus

Feminists and anti-racists recognize that identity does matter. This is indisputable. If we subscribe to the belief that ideas can be judged within a vacuum, uninfluenced by the social weight of their proponents, we perpetuate a system in which arbitrary markers like race and gender influence the perceived correctness of ideas. We can’t overcome prejudice by pretending it doesn’t exist. Focusing on identity allows us to interrogate the process through which white males have their opinions taken at face value, while women, people of color, and non-normatively gendered people struggle to have their voices heard.

But we also destroy ourselves when identity becomes our sole focus. Consider a tweet I linked to (which has since been removed. See editor’s note below.), from a critic and artist, in which she writes: “When ppl go off on evo psych, its always some shady colonizer white man theory that ignores nonwhite human history. but ‘science’. Ok ... Most ‘scientific thought’ as u know it isnt that scientific but shaped by white patriarchal bias of ppl who claimed authority on it.”

This critic is intelligent. Her voice is important. She realizes, correctly, that evolutionary psychology is flawed, and that science has often been misused to legitimize racist and sexist beliefs. But why draw that out to questioning most “scientific thought”? Can’t we see how distancing that is to people who don’t already agree with us? And tactically, can’t we see how shortsighted it is to be skeptical of a respected manner of inquiry just because it’s associated with white males?

This sort of perspective is not confined to Twitter and the comments sections of liberal blogs. It was born in the more nihilistic corners of academic theory, and its manifestations on social media have severe real-world implications. In another instance, two female professors of library science publicly outed and shamed a male colleague they accused of being creepy at conferences, going so far as to openly celebrate the prospect of ruining his career. I don’t doubt that some men are creepy at conferences — they are. And for all I know, this guy might be an A-level creep. But part of the female professors’ shtick was the strong insistence that harassment victims should never be asked for proof, that an enunciation of an accusation is all it should ever take to secure a guilty verdict. The identity of the victims overrides the identity of the harasser, and that’s all the proof they need.

This is terrifying. No one will ever accept that. And if that becomes a salient part of liberal politics, liberals are going to suffer tremendous electoral defeat.

Debate and discussion would ideally temper this identity-based discourse, make it more usable and less scary to outsiders. Teachers and academics are the best candidates to foster this discussion, but most of us are too scared and economically disempowered to say anything. Right now, there’s nothing much to do other than sit on our hands and wait for the ascension of conservative political backlash — hop into the echo chamber, pile invective upon the next person or company who says something vaguely insensitive, insulate ourselves further and further from any concerns that might resonate outside of our own little corner of Twitter.

--

youtube

==

This has been going on for over a decade. The correct response is to mock and laugh at the people complaining, and point out that they're not ready for the big wide world outside their kindergarten mindset, so they'd be better off going back home to mommy and daddy. Not validate and endorse their feelings. We need to get back to that.

#Edward Schlosser#trigger warnings#hypersensitivity#Christina Hoff Sommers#safe space#academic corruption#higher education#religion is a mental illness

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

AN ITINERARY FOR NON-PLACES: billy woods & Kenny Segal's Maps

We on a world tour with Muhammad, my man;

going each and every place with the mic in their hand.

—Trugoy the Dove, ATCQ's "Award Tour" (1993)

Perhaps you will persuade him to relate something of his past. Perhaps there is one among you who can induce him to bring out his old travel-diaries; who knows?

—Rainer Maria Rilke, The Journey of My Other Self (1930)

Now when I was a little chap, I had a passion for maps.

—Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1899)

Maps won’t work here.

—Aesop Rock, “Rabies” (2016)

1.

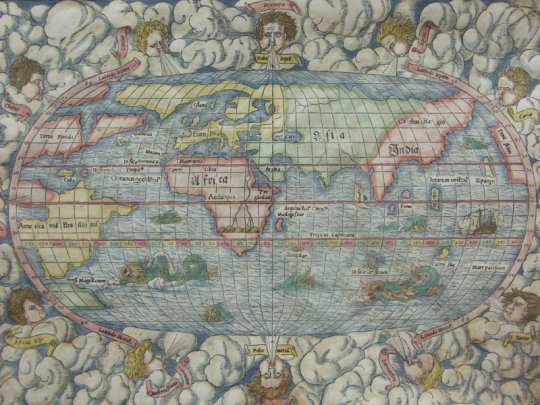

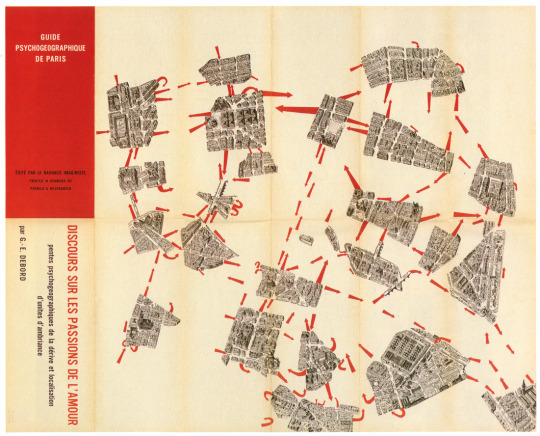

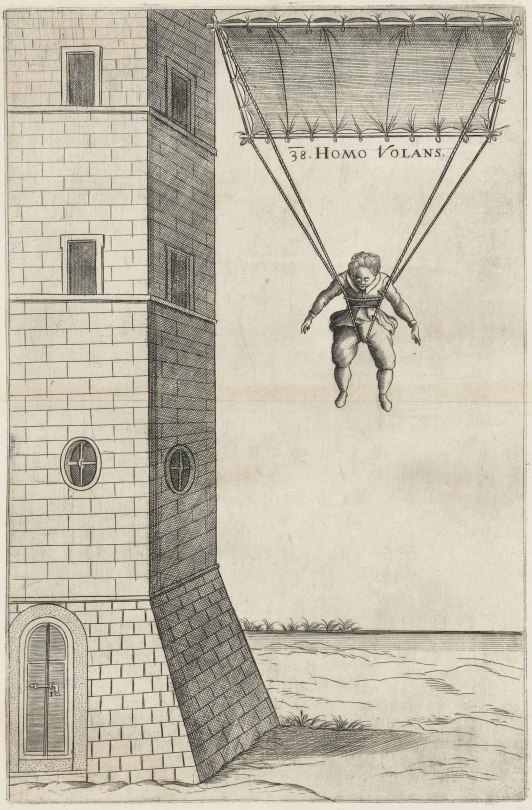

You arrive with certain expectations. You arrive with Edward Said quotes queued up in your mind, knowing “what on a map was a blank space was inhabited by natives.” As such, you equip yourself with “map and compass, gat and cutlass” (“U-Boats”), keen to trouble Orientalist notions. Don’t get it twisted as you mark twain: there are flare-ups. On “Hangman,” we hear of “Hindu kush, a Sikh surrounded by Thuggers,” a modernist nod to August Schoefft’s early-19th century painting. We hear of “flying carpets out this motherfucker.” It’s a whole-new, brave-new world. “The room smelled like Marrakech,” woods reports on “FaceTime,” and George Orwell’s “Marrakech” (1939) happens over the mind’s transom. Orwell depicts colonial subjects who, in the imperial imagination, are nothing more than “undifferentiated brown stuff”—each figure what Said calls “an atom in a vast collectivity.” So, yes, you can skirt “on the edge of Magellan maps” (“Wonderful World”), or take a cue from Mike Ladd and rip to shreds Universalis Cosmographia by Sebastian Münster, that lying bastard, but—like Dylan on “My Back Pages”—woods is riding “on flaming roads using ideas as [his] maps.” We’ll meet on edges soon, he says—probably the “lists of names, pages and pages” he’s hoarding on “Soft Landing”—but the impulse here should amount to more than freeing political dissidents from cages. On Aethiopes, woods clocked nautical miles, but now he’s on a world tour redeeming his frequent flyers. You’ll find nothing quite as unrepentant as cannibal tours here, though there are horrors and hors d'oeuvres aplenty. These Orientalist postulates are somewheres, but Maps is concerned with nowheres.

2. SUBS & COMPONENTS

Yeah, I’m leaving tomorrow, but I got time today. woods begins “Kenwood Speakers” by speaking his words of departure like John Denver, only he spares us the sentiment. “Leaving on a jet plane—” Denver sings, “don’t know when I'll be back again. / I hate to go.” woods is at worst eager and at best aloof about his own leaving. V. S. Naipaul’s Ralph Singh from The Mimic Men, meanwhile, goes further, stating bluntly: “I am not coming back.”

Maps—like Dante’s Inferno, like Plato’s cave—is where all people come to know themselves. The album is billy woods’ itinerarium mentis—his journey of the mind—a [hero’s] journey into the center of the [real] earth. One-dimensional MCs can’t handle that. The undertaking requires steadfast digging into the so[u/i]l of one’s self. Another turn of the screw, gyring deeper, despite how much the torture/[tour]ture might hurt. We feel the pangs right along with him, do we not?

Guess who’s coming to dinner on “Kenwood Speakers”? Some born sinner, the opposite of a winner—but not a sardine in his line of sight. Only Deleuze and Guattari lines of flight—escape routes to deterritorialize your whole plane of immanence. The night before woods departs on a pilgrim’s progress, his body and being go surface-to-air—Habyarimana on an economy flight. Or John Denver even, who was watching time and space cross his path as his Rutan Long-EZ plane nose-dived into Monterey Bay. Knock the plane out of the sky and woods sparks his own personal gentrifier genocide.

This is where your humble essayist springs a gentrification quote on dat azz. Say, David Harvey quoting Lenin quoting Cecil Rhodes—that would be apropos. Some “Accumulation by Dispossession” shit; some spatio-temporal fixes shit. But bleary-eyed theorizing would diminish what woods does with his terse, yet totalizing, imagistic lines. I’m gonna sit this one out and leave it to the gentrifiers themselves to tell it. (Catch me like “Lenin lying in state” [“Warmachines”]; or, as we hear on “NYC Tapwater”: “I lie down like V.I. Lenin.”)

3.

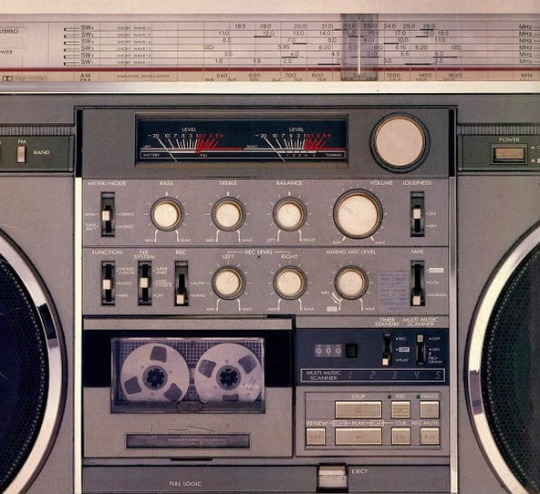

The title “Kenwood Speakers,” of course, is a portmanteau of their names [Kenny Segal + billy woods]—the blending of sound and style of [e]strange[d] bedfellows: woods as an observant Ishmael to Kenny Segal’s affable Queequeg. woods listens to Kenny Segal’s beats like Ishmael opens up to Queequeg’s tattoos—his cannibal body [of work] a “book of nomad inscription,” according to Pierre Joris. The “port” of this portmanteau is a haven, a hush harbor. “The port would fain give succor,” Melville writes, “...in the port is safety, comfort, hearthstone, supper, warm blankets, friends, all that’s kind to our mortalities.” Portmanteau as leather luggage, too—filled with Kenny’s circuit-bent Omnichord, his pedals, his SP-404, his “weird little children’s toys turned into live beat-machine things” (in woods’ words). woods calls him “nuts,” but so too was Glenn Branca. Forget jazzmatazz, Kenny’s brand of jazzmaskronk incorporates No Wavy horns and angular guitar strokes put to the orbital sander. Bring the sinuosity. Tonal plexus, to perfection. Counterpane production steez: combining elements unmethodically in sun and shade; beats stuffed with corncobs or broken crockery. Better to sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian. Bones litter the beach, gnawed.

4. A MINIMALIST HOMEBOY WHO KNOWS HIS BEATS

The opening clicks on “Kenwood Speakers” are the clicking of a gas stove before the burner crowns with blue flame (...blue flame like the oven, woods says on “Rapper Weed”). And we can trace the sonic sum of his drum thump and drum pattern to LL Cool J’s “I Can’t Live Without My Radio,” another ode to electroacoustic transducers. The Rubin-produced banger gets audiophiliacs amped—woofers wallop and tweeters twitch. Move forward in time to “Fantastic Damage,” where El-P introduces a boom-bap that veers cement-crush. He leaves “ruthless rounds of radio dust” in his wake—“cranial mush.” Bigger, deffer, fitter, happier, more productive.

In the liner notes for Radio (1985), Nelson George calls LL a “talkologist,” which we can apply to woods, too. “After-market speakers in the Saturn,” he raps, and his whip is his own personal universe, evidently. He’s a brother from another Lonely Planet. Fodor’s on the dashboard; Baedeker in the backpack. From Plainfield to Compton: Swing down, sweet chariot, stop, and let him ride dirty in a lemon (hell yeah): “Beater but they can’t catch it.” The engine clunks and clatters just as the beat breaks down after the first verse—a beat transition/deconstruction not heard since DJ Shadow’s work on “Latyrx.” Kenny Segal’s music is all Chords and Discords, like the Letters to the Editor section of DownBeat magazine. Noizy Meditations like that L.O.N.S. joint T.I.M.E. (“cover my tracks with backronyms”). Fair to say Kenny Segal could pull a broad sword from a hoarded synthesizer, word to Aes Rizzle.

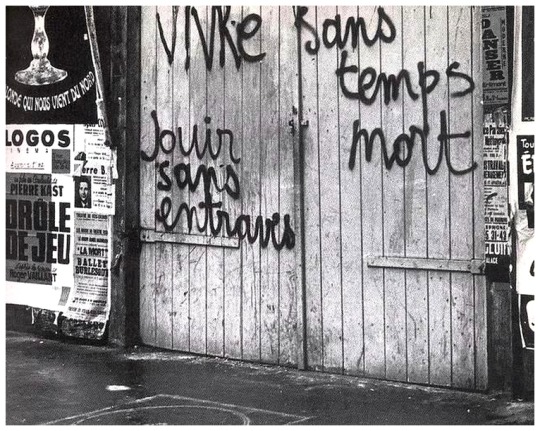

5.

LL’s radio appeared to ward off gentrifiers by design, destabilizing the ground beneath their feet: “My JVC vibrates the concrete.” He was “terrorizing [his] neighbors with the heavy bass.” True to Duke Bootee and Melle Mel, the impoverished city is like a jungle sometimes—“the rats is madness”—and the superpredators sport Brooks Brothers suits. woods is watching the blue-eyed soulless ones encroach, the “blue-eyed White Walkers in King’s Landing.” They march on the miry Slough of Despond. He’s not trying to leave the neighborhood empty-handed, so he infiltrates. He finagles and ingratiates himself into a “dinner party with the neighbors, / Their apartment’s renovated”—no longer a “crumbling mansion.” He eats their food ravenously, wolfishly. With each morsel, he’s seeking the beloved community, or so they’d like to believe.

As they dine, woods “turn[s] the music up incrementally,” and you’ve got to imagine it’s some PMRC fare—Ice-T’s “You Played Yourself” or the like. Something equal parts catch-wreck and (w)reckoning. Or maybe the song is “Kenwood Speakers” itself. And it’s a sort of Jordan Davis reversal at work. woods as Lord Baelish with the “mischievous lies.” He’s Claudius with a cup of poison. The whole ear of gentrified Bed-Stuy serpent-stung, rankly (and thankfully) abused. woods goes full Ying Yang Twins and “whisper[s] in the host’s ear all night,” hexing him, slow-releasing Paraquat into his supple mind as he sups. (That’s what’s up.) We’ve seen him in this capacity before, like when he whispered to his own dull knife-sheared shadow on “houthi.” The hushed hemlock woods administers to the “host’s ear” collapses into what woods “hear[s]” later—that “they found [the host] in the morning [with the] hose run from the exhaust pipe.” A well-thumbed copy of White Fragility left behind on his nightstand. woods reveals himself to be Samwell Tarly with the black dragonglass dagger. “Wreathed in gas—I’m a carburetor,” woods raps, contrasting his smoky satisfaction with the carbon monoxide car killing. He sees the Wicket Gate blurry in the distance—and it bears a helluva resemblance to an airport gate.

6. SPACE IS THE NON-PLACE

Much has been hastily made of the narrative structure of Maps—eager listeners figuring wussdaplan and blueprint to the realms ’n realities that the album presents. But order—beginnings [departures] and endings [arrivals]—isn’t important; movement is. Better find out, before your time’s out, what the flux? Think Inspectah Deck’s “alive on arrival”; disregard Puff Daddy’s “mess around be D.O.A., be on your way” (but heed his fugacious “ain’t enough time here”). Non-narrative acceptance will allow us to revel in what Nathaniel Mackey calls “the rickety, imperfect fit between word and world.”

And as we navigate that imperfect fit, dwell in the non-. Dwell in the non-, in the non-, in the non-. “An airport is nowhere,” W. S. Merwin writes, “which is not something / generally noticed.” Merwin’s poem (“Neither Here Nor There”) typifies ideas explored in Marc Augé’s Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity (1992). Augé analyzes the meaning of transient spaces in our fast-paced, globalized society. He sets places (rooted, concrete, community-rich locations—where “saplings bend” but don’t break) against spaces (abstract locations of the mind—“I live in my mind,” as woods said on “Asylum”). We spend an immoderate amount of time in a multiplication of “non-places,” which Augé sees as “installations needed for the accelerated circulation of passengers and goods”—airports, hotels, interchanges, high-speed roads. This is the world woods knows all too well on Maps. Whether he’s taking a “$300 Uber to a show” role-playing as Future in a Maybach, smoking a spliff that “could probably jump your car battery,” exploring “Johannesburg in a Ford Explorer,” or manifesting “Jimmy Wopo draped over his steering wheel,” woods inhabits the image of the non-place. Makes sense for someone who claims to be “from where every car foreign and [they] drive ’em on empty,” dwelling in disconnectedness. Your head is throbbing and I ain’t said shit yet—the next movement is by air.

7.

woods takes in the view from his plane window. “Space,” Augé writes, “stems in effect from a double movement: the traveller’s movement, of course, but also a parallel movement of the landscapes which he catches only in partial glimpses.” On “Soft Landing,” woods sees with new sight: “From up here the lakes is puddles, / The land unfold brown and green—it’s a quiet puzzle.” woods pieces the partial glimpses together into something cohesive and captivating—“a series of ‘snapshots’ piled hurriedly into his memory and, literally, recomposed in the account he gives of them,” in Augé’s words.

“But the book is written before being read,” Augé adds, and let’s exchange “book” with album and “read” with heard. “[I]t passes through different places before becoming one itself: like the journey, the narrative that describes it traverses a number of places.” For woods, these places include a pop-in with Aesop Rock in Portland, Oregon, a visit to the Alchemist’s lab in Los Angeles, and a late-night stop at Steel Tipped Dove’s apartment in Brooklyn. He takes up residence at Kenny Segal’s L.A. home and traipses around Japan, Brussels, Amsterdam, and Germany. Augé:

This plurality of places, the demands it makes on the powers of observation and description (the impossibility of seeing everything or saying everything), and the resulting feeling of “disorientation”...cause a break or discontinuity between the spectator-traveller and the space of the landscape he is contemplating or rushing through. This prevents him from perceiving it as a place, from being fully present in it, even though he may try to fill the gap with comprehensive and detailed information out of guidebooks.

woods has discussed the “mental and physical spaces that type of travel and touring put[s] [him] in.” His documentation of his movement through non-places is the least he can do to keep from entropying: “I was writing in hotels, and Airbnbs, and airports, and sometimes at home.” For us though, his audience, woods is no longer hiding places; he’s exposing places.

8. LIKE, “I JUST FLEW INTO THE CITY—WHAT’S UP WITH YOU?”

We hear “hero’s journey” and immediately inch toward Ithaca and Homeric hexameter, but Gilgamesh should be our guidepost, not that man-of-many-ways Odysseus. Our guidepost is woods’ “Gilgamesh”—a relationship song of stunted growth and stasis. “Got a call out the blue,” he starts, but with Maps, the call is to us and it’s a clarion call. The name Gilgamesh rings out, and it sounds like “rattling medals.” On Maps, it sounds like a “chain banged [on] glass ceilings,” an echo of Prodigy’s piece banging on glass tables. We heard the vibrations on “houthi”—that “change on plexiglass” jingle. I’m impressed by the resonance. The message doesn’t “sound weak coming out the speakers” like it did on “Gilgamesh.” The marginal upgrade is Kenwood speakers—no puttering set of Polks.

woods is arguing for a new paradigm—he didn’t need his paradigm to shift like the rest of us did. He read the daily briefings and was familiar with what-goes-around-comes-around logic. He wasn’t caught lacking on 9/11—we were. He’d been rapping along with Biggie (Blow up like the World Trade…). He coveted his promo copy of The Coup’s Party Music with Boots holding the detonator on the cover. He was looking at the city like jihadis in the cockpit. When it comes to artistic representations, like my homie D.O.C., no one has done 9/11 better than billy woods. Noreaga adopted the personage of Manuel Noriega; Intelligent Hoodlum was reborn as Tragedy Khadafi; woods takes on the mantle of Osama bin Laden—green army field jacket over white robe.

On “Gilgamesh,” he’s “left thinking like Osama in Khartoum” when his ex splits, “gone at first light, connecting flight—she made the plane.” Vindictiveness aside, woods should know her airport visit alone will be a hellish experience. Punishment enough. Subjected to TSA screens and pat downs while touring the globe, find woods “excessively mean-mugging” as the metal detector wand grazes his testicles. “Airports and aircraft, big stores and railway stations have always been a favoured target for attacks,” writes Augé, “doubtless for reasons of efficiency…. But another reason might be that…those pursuing new socializations and localizations can see non-places only as a negation of their ideal.” woods’ 9/11 bars may startle us, but they disabuse us of our bliss.

9.

GO flat out at top speed across curve of earth is the only way.

—Pierre Joris, A Nomad Poetics (2003)

The earth is a sphere.

—“Houdini”

All this perpetual movement, this implacable globetrotting, these abrupt shifts in location—it makes for a nomad poetics, as poet Pierre Joris puts it. woods is a “NOET,” where “NO stands for play [and] ET stands for et cetera, the always ongoing process, the no closure.” Joris describes how polylingualism is a nomadic trait that is capable of “moving through languages, cultures, terrains, times without stopping.” So woods drags us from witnessing Yemeni traders off the coast of Mozambique (“The Doldrums”) to Dien Bien Phu (“Baby Steps”) in less than twelve months. He slips into Jamaican patois and amuses us with his limited Spanish (Muchos problemas if you don’t have it for the plug…). In “The Schooner Flight,” Derek Walcott says, “either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.” woods would remix: I’m nobodies and nations.

“[I]f it is all flux, all nomad wandering” for the NOET, “when & how to write,” Joris asks. “How not to stop & yet do the poem?” The nomadic poem—like the songs that make up Maps—is a “poasis, a poem-oasis, i.e., a stop in the moving along.” In Sufi poetry, this is known as the mawqif, which Joris defines as “the pause, the stop-over, the rest, the stay of the wanderer between two moments of movement.” The layover, in woods’ words. A moment of “movement-in-rest, of movement on another plane or plateau, between today’s & tomorrow’s lines of flight.” Recording “Rapper Weed” in Kenny Segal’s studio in L.A., for example.

Nomad poetics encompass a political component. Joris isn’t blind to the realities of “a historical era where cheap air flight has made at least the White World into summer travelers, sun-seekers, tourist-nomads, i.e., fake nomads, or really not nomads at all, while a large part of poor Third World people are constrained to turn themselves into forced labor exilees or at best transhumance-ing workers, transients that have been ‘transported’ as the term was used in the slave trade.”

The triangulation of “sugar, molasses, rum”—it’s a strangulation. There’s trouble with travel. Travel as forced relocation. Travel as travails, as toil—or, worse—as tripaliare (Vulgar Latin for “torture”). From your book I took a page, bell hooks—who writes in Black Looks (1992) of being accosted, detained, and interrogated by white officials while in an Italian airport, and another time being strip searched at an airport in France, suspected of ties to terrorism in both cases. “[T]o travel is to encounter the terrorizing force of white supremacy,” she writes. Augé writes about how “the user of the non-place is always required to prove his innocence,” but for bell hooks, a Black woman, “there is no comfort that makes the terrorism disappear.” Who is Augé to judge how she terror manages?

“Goin’ places that I’ve never been, / Seein’ things that I may never see again,” Willie Nelson sings, impatient for a return to the road. His is a romanticized perspective; with feelings of dissociation, woods offers a no-man-ticized one, more akin to Atmosphere’s “Travel” from 2000: “We travel like the blood that surrounds your brain”—pressure builds and aneurysms flutter under cranial walls. The itinerary looks blurry, the ink faded from sun, folds, and creases. “The engagements are booked through the end of the world,” croons They Might Be Giants’ John Linnell, “so we’ll meet at the end of the tour.” [Open Mike Eagle nods approvingly.]

10. HEAVY AIRPLAY ALL DAY WITH A NINA SIMONE CHORUS

On “Soft Landing,” Kenny Segal introduces guitar to drums and they converse in a dissonant cadence. In the words of Cecil Taylor, they consist of “regular and irregular measurements, of coexisting bodies of sound.” woods takes flight and the sound of the plane lifting off the tarmac is a welcome relief, like blasts from Michael Nyman’s Decay Music (1976). “Birds flying high,” woods sorta-sings, and he follows their migratory patterns. Just get him the fuck outta dodge. He’s a budding ornithologist with his head in the loud clouds. We hear him mention “birds-of-paradise in the menagerie” and “midnight ravens” alike. The exotic and the demonic—he studies them all, binoculars to his peepers.

“Before we take off, I call Mom and say, I love you,” woods raps. He’s taken a note from Quelle Chris who advised, “Call your folks while they still livin’.” woods’ mother antipodal to his ex who he texts upon landing with a significantly less felicitous message—one feminine figure signals ascent; the other, descent. The in-betweenness of the experience—limbic and liminal all at once, exemplified by woods with his “head in the loud clouds [and] both feet on the fucking pavement.” woods invariably finds himself in the in-betweenness, the purgatorio of his life’s purpose: be it from “Rolling Loud to Shakespeare in the Park” or his own nature documentary “narrated by an Attenborough [but] over the instrumental to ‘Keep It Thoro.’”

“You believe in [the airport],” Merwin writes:

while you are there

because you are there

and sometimes you may even feel happy

to be that far on your way

to somewhere

You know how I feel? woods feels the altitude sickness, his ears popping. But once that subsides, he feels suspended in time and space. Sun in the sky. Breeze driftin’ on. Only gotta fear a flock of geese in the aircraft engines, what with no savior Sully to guide the passengers to safety. At long last, he feels free from the fetters of his life down below. He’s [re]set for a soft landing.

11.

Look out, honey, ’cause I’m using technology,

Ain’t got time to make no apology.

—The Stooges, “Search and Destroy”

There’s a duality on Maps: two selves—one who longs to travel; the other who longs to return home. Calypso after the show, but FaceTime calls with the kids at the breakadawn. On “FaceTime,” though, home is the last place. Home is where the heart gave out. What woods takes with him on the flight are the repercussions, the health complications. Quarrels crammed in the carry-on. Relationship woes on the wing:

You flyin’ easyJet—Bratislava, Utrecht,

Something felt off before I even left,

So when I saw the missed calls, I knew what was next.

Didn’t have to open the text.

woods delineates a communication breakdown. He initially tries to distance himself by using the second-person, but moments later he’s allowed himself to be drawn back in. He notes the “missed calls” and uses every shred of self-discipline to not “open the text.” The patterns, he reminds himself, are nothing new. He may be unnerved by “flyin’ easyJet,” but the awareness that “something felt off before [he] even left” feels good—a familiarity. The consonance of “felt off before I even left” provides him the lift he needs. No matter the angle he looks at it [“felt” or “left,” anagrammatically satisfying—he can sit with his feelings or leave them all behind], he’s floating above the rubble of the relationship.

Not for lack of trying. They did “couples therapy on Zoom, [but] it’s a train wreck.” The Celestial Railroad derails and they burn off the vinyl chloride toxic spillage. The evacuation zone is 30 kilometers wide. woods is a sucker—falls for it every time. Okay, okay, okay: not every time. He’s become adept at having his “evil eye ward off hex, though—FaceTime declined.” He goes full Last Tango in Paris on the enchantress, displacing his frustrations on a crowd of innocent civilians: “Butter wouldn’t melt, I gave ’em margarine.” Echoes of Tony Soprano after Carmela informs him that’s she’s filing for divorce: “The only reason you have anything is ’cause of my fucking sweat, and you knew every step of the way exactly how it works. But you walk around that fucking mansion in your $500 shoes and your diamond rings, and you act like butter wouldn’t melt in your mouth.” If we’re talking socialization mediated by screens, this is some real prestige drama—really real, son.

Ce grand malheur, de ne pouvoir être seul.

With so much drama in the relationship, woods retreats further. He loses himself at a gig. Afterwards, he writes at his desk in a hotel room in Tucson as he hears “dubstep drift in the window.” Partiers, “some half, some overdressed,” make their way through the halls, “checkin’ they phones” as the “bass shake[s] the walls.” woods is removed from it all: “I’m smoking alone in a cardigan, thinking of home.” In non-places, Augé insists, you can find yourself “alone, but one of many.” Once more unto the breach, he goes “back down to the bar again” only to witness an “afterparty packed like Parliament,” and who can really say whether it’s the funkiness of George Clinton or Margaret Thatcher, but the masses are pressed “ass cheeks and cheekbones”—baby got bacchanalia. woods, for his part, is “looking like the help or someone who just wandered in.” He’s an outsider amongst the “animal pelts,” “chunky rings, clunky shoes, [and] lots of ink.” Out of place, out of sight, out of mind, out-of-body experience. He’s Poe’s eagle-eyed protagonist in “The Man of the Crowd” (1840), “observing the promiscuous company in the room.” He marks the “dense and continuous tides of population,” “their aggregate relations,” and he “regard[s] with minute interest the innumerable varieties of figure, dress, air, gate, visage, and expression of countenance.” Despite all of that distraction, by the end of the song woods has only moved the pen six inches. “Really,” he says, regaining our trust, her trust, “I’m just waiting for my phone to ping”—emphasis on waiting. “I’m thinking ’bout you when I’m supposed to be thinking ’bout other things.”

12.

A stay in L.A., L.A., big city of dreams, but everything in L.A. is overpriced. Avaricious sonsabitches “bloated with gout, / Sores weeping, doubled-over, chest heaving from chasing clout,” shelling out “six Gs an ounce.” woods went from genuflecting at the weed price to oof. He’s a savvy consumer, but Los Angeles, as Mike Davis writes in City of Quartz (1990), is “a stand-in for capitalism in general.” He continues: “The ultimate world-historical significance—and oddity—of Los Angeles is that it has come to play the double role of utopia and dystopia for advanced capitalism. The same place, as Brecht noted, symbolized both heaven and hell. Correspondingly, it is the essential destination on the itinerary of any late twentieth-century intellectual, who must eventually come to take a peep and render some opinion on whether ‘Los Angeles Brings It All Together’ (official slogan) or is, rather, the nightmare at the terminus of American history (as depicted in noir).” woods excavates the future in Los Angeles, such as Davis’s subtitle goes, where the “Nike store on Fairfax” is absent of inventory, where one’s commodified state of being includes “monogrammed tube[s],” “crushed velvet,” and other offscourings of “colorful packaging.” None of which is of much interest to billy woods, a man who has “learn[ed] to toss the dregs.” This place, he knows, is a cemetery. He rests his riveted gaze on the “whole entourage on the couch buried in they phones.” You heard right: buried in they phones—their absence-presence of screen staring, their doom-scrolling a Tibetan Book of the Dead written in real time, a bardo of blue light. Mike Davis is quick to remind us: “Pío Pico, the last governor of Mexican California and once the richest man in [Los Angeles], was buried in a pauper’s grave.” “When it’s my time,” woods raps, “no need to pass the hat.” No GoFundMe campaign necessary to cover the costs of a champagne crepe-lined casket. “Just throw me in when the fire good and crackling,” he implores. My my, hey hey—it’s better to burn out than to fade away. Send him up in smoke just the same as so much of his precious time on earth. “Bury me in a borrowed suit,” woods advised his mortician on Earl Sweatshirt’s “Tabula Rasa.”

13.

Jet-lag is the cousin of Death. On “Bad Dreams Are Only Dreams,” woods grows weary as his transient life becomes a trance-ient life. “I can’t quite grab the new me,” he raps, brainfogged as he passes through time zones like skipping stones. His “old self [is] dozing in an aisle seat” on an Emirates flight. Forget about his girl back home, now he’s divorced from himself. Augé:

When an international flight crosses Saudi Arabia, the hostess announces that during the overflight the drinking of alcohol will be forbidden in the aircraft. This signifies the intrusion of territory into space. Land = society = nation = culture = religion: the equation of anthropological place, fleetingly inscribed in space. Returning after an hour or so to the nonplace of space, escaping from the totalitarian constraints of place, will be just like a return to something resembling freedom.

woods has split the self, drawn-and-quartered it. He’s his own chain gang. On the side of the road where his “brain [is] exposed to the elements.” If we “lift [his] skull-top off delicate,” we see it’s “wider than the Sky,” as Emily Dickinson similized it. Worst of all, it’s infected by devils who’ve no regard for the fragile “bone china chafing dish” that holds the brain. “Absent-minded,” woods raps—he’s absent of his mind. And that might be an error, as criminal-minded might more accurately reflect his present status of “break[ing] time like bricks.” “Thoughts is cinder blocks,” but all I can see is woods breaking rocks in the hot sun. When he soundclashes, he fights the law. In his cell watching Shogun Assassin for the umpteenth time, but he’s also come into possession of a VHS copy of Can Dialectics Break Bricks? (1973). Flyin’ easyJet: Hong Kong to Paris. How different is monotonous prison labor from the toil of travel? Luggage heft; cramped legs; numb ass. woods needs rest and recovery, but “alarm clocks break spells.” He’s living in his own private Gitmo. Enhanced interrogation has him walking the witch. TSA sleep-deprives him to extract intel, to elicit a confession. His Self is reduced to geologic bits. He’s “crashed out,” Flight 93 style, as he becomes a plane making impact with the ground in Shanksville, PA and disintegrates. “Search for my own black box in the hills,” he raps, wanting to recover his own voice, his own data. Just as he said on “Red Dust,” “it’d be wise” to retrieve it. But what he finds amongst the strewn debris is a “black Rubik’s cube,” impenetrably scrambled.

This nightmare scenario has woods like the rappers he described on Armand Hammer’s “Aubergine”: “Tired, / Inertia the only thing keep ’em moving, / Glassy-eyed.” woods is a survivor of the crash, of sorts—his “parachute twisted and snarled.” You can’t put a price on a good night’s sleep, even if it’s a “king’s ransom.” But woods is “half ’sleep with the halo, dead on his feet,” so maybe it’s too little, too late. He wanders zombified, inactive, unconscious. He’s trying to get right for today; he’s “not swimming in tomorrows” like on “Babylon by Bus.” His death grip on reality is only as firm as his grip on surreality, as we heard from his appearance on Infinite Disease’s “Anomalady”:

After a while, you don't remember the crowds or venues,

just the hotel rooms.

¿Tu tienes WiFi?

It's just me in a stocking cap, watching TV

The city dead out the window, still not even sleepy

Sleep deprivation, the days keep leaking

Life on the screen, light the dark like a beacon

woods the amnesiac—he “don’t remember the crowds or venues.” If only he could repress the meaningless hotel rooms instead. Alive ain’t always living in non-places (just ask Quelle Chris), especially when it’s mediated by technology: WiFi passwords, TV, his phone. Somehow he survives; it’s the city that’s dead.

14. FBI AGENTS NARROW THEY EYES

When you turn the knob on “Blue Smoke,” you trick yourself into believing you’re rehearsing with Ornette. We feel inner circle. We feel privy. But Max Roach might also be in the audience, like he was at the Five Spot in 1959, waiting for Ornette to step offstage so he could duff him up, which he did. The FBI had a dossier on Roach, just as they did for so many other Black cultural icons. COINTELPRO with the hyper-acuity. ELUCID forewarned: Fifty people at a rap show—one’s an informant. Police came to billy woods’ show on Known Unknowns, an album which has moments that jive with the claustrophonic and paranoisey sounds of Hiding Places. To avoid any confusion, I’ll pass the mic to media god Marshall McLuhan:

We now have the means to keep everybody under surveillance…. This has become one of the main occupations of mankind—just watching other people and keeping a record of their goings-on. Invading privacy—in fact, just ignoring it. Everybody has become porous…. When you’re on the telephone, or on radio, or on TV, you don’t have a physical body. You’re just an image on the air…. You’re a discarnate being. You have a very different relation to the world around you. And this, I think, has been one of the big effects of the electric age. It has deprived people, really, of their private identity.

On “NYC Tapwater,” woods takes a stab-your-brain-with-your-nose-bone attempt at mentoring the youngins: “No need for stop-and-frisk, it’s cameras everywhere, / They got your IG feed, / Come scoop kids after they do the deed.” Mass surveillance should have you shook. woods spies the “big-ass satellite dish pointed at the sky,” on “Blue Smoke.” woods fucks with the frequencies frequently, sabotaging the alphabet boys with “so much tape hiss.” These aren’t just some plainclothes cops with iPads in Missoula, Montana. These are FBI agents that “narrow they eyes, / Frustrated, asking to be reassigned” because woods is giving them nada. “Been on this n-word for months,” they concede, “I think it’s all just rhymes.” Yep, rhymes like dimes. Talk about a most strange game, but woods knows he “shouldn’t be surprised.” Know that you’ll be scrutinized. He threatens that he better not “catch you unsupervised”—from the Latin super [“over”] + videre [“to see”], which = overseer. You know that sound—it’s the sound of da police. Same as you heard at the conclusion of “Police Came to My Show.” KRS-One offered a likkle truth and implored you to open up your eye. An exercise, from the Teacher:

Take the word overseer, like a sample,

Repeat it very quickly in a crew, for example:

Overseer, overseer, overseer, overseer—

Office, officer, officer, officer.

No wonder woods guards himself with galvanized steel security fencing. In a non-place like an airport, writes Augé, “the passenger accedes to his anonymity only when he has given proof of his identity.” Mom showed him where she keeps the passport hidden, and he retrieves it when necessary. Similar rules apply to others. “Anyone wanna be in my life gotta sign several waivers,” he raps strictly on “Babylon by Bus.”

15.

I traveled among unknown men.

—William Wordsworth (1799)

I asked, “Is the mask for the killer or the crowd?"

—Armand Hammer’s “Sadderday”

What is known and unknown (in a Rumsfeldian sense); what is seen and unseen (in a Lord Quasian sense)? You can obfuscate the message. You can adjust the pitch of your voice. Augé explains how the “spatial overabundance [of non-places] works like a decoy.” Hiding places are everywhere, but they’re especially easy to access while on tour. A person “entering the space of non-place is relieved of his usual determinants,” writes Augé. “He becomes no more than what he does or experiences in the role of passenger…. Subjected to a gentle form of possession, to which he surrenders himself.” The rep grows bigger, ELUCID raps on “As The Crow Flies,” but not so big and unwieldy that woods can’t shuffle through a non-place without being recognized by adoring fans. He settles into what Augé refers to as “the passive joys of identity-loss.”

“Just picture me sittin’ with a pen in a cloud of smoke,” woods says on “Baby Steps.” He asks us to envision him in a rather peculiar scenario, one in which he’s taking notes on a performance while concealing his own presence (despite seeking “to determine if [your live set’s] a hoax”). The performer is a “glowed up” Weird Sister, “looking like she covered in gold dust.” woods deduces she “must not have re-upped her Lexapro,” but her glamorous appearance plays against woods’ own guardedness. You don’t just let anyone in. woods is privileged, though, as the performer “pulled [him] aside [and] explained she was just doing a bit.” One is inclined to consider whether this is all a projection on a screen. Or, put differently: Is this performative or praxis? Either way, woods was like, Oh. And not since his ex-wife’s reaction to learning “where [he] stashed it” has a response hit so heavy (“She paused, then she said, OK”). woods’ whole life feels stashed—brown-bagged or cardboard-boxed. A secret sharer, he’s not.

It’s' places no one knows who you are,

It’s faces we never wore.

—“Agriculture”

Would woods be able to distinguish a DOOMposter from the real thing—a cheap, bumbling replica from the genuine article? “Over time,” woods raps, “symbols eclipse the things they symbolize.” The mask becomes not a means to maintain privacy but a phenomenon itself—a mass-marketed one, at that. Just ask the MF DOOM estate. DOOM masks created and sold by both authorized and unauthorized retailers proliferate. Etsy shops stay busy predicting their posthumous profit margins [see: DEATHFAME]. MF DOOM likened his “imposters” to characters. “[W]ho I choose to put as the character is up to me,” he said. “When you come to a DOOM show…[you’ve] come to hear the show and come to hear the music. To see me? Y’all don’t even know who I am! Technology makes it possible for me to still do music and not have to be any particular place…. [I]f you’re coming to a DOOM show, don’t expect to see me, expect to hear me or hear the music that I present.” It sounds like DOOM is eternally wandering one of Augé’s non-places as one of McLuhan’s “discarnate beings.”

woods has been Camouflaging himself since at least 2003. Like Poe, he is the man of the crowd, and “[i]t will be in vain to follow: for I shall learn no more of him.” On “Soundcheck,” he asks the venue to “kill the lights,” just as he does every show, murdering the audience’s hope of eye contact, of facial recognition. Even if they manage the right angle and a “Nikon flash,” woods’ “face is the mask.” As he walks through the uncanny valleys of the shadows, you “develop the photograph but [find] something just wasn’t right.” President Kongi did not like to be photographed, and you heard Pac screamin’, spittin’ at the paparazzi. At the merch table, woods places his hand in front of his face for fan photo ops [or are they photo opps?]—a strange paradox of acquiescence [woods stops resisting the photo request, in cop parlance] and a gesture of refusal. “It’s GWAR when I’m off-stage,” he tells us on “The Layover.” The mask evolves over time. DOOM went from pantyhose, to a silver-sprayed Darth Maul mask, to a faceplate from a Gladiator helmet (the latter two prototypes thanks to the ingenuity of KEO). Oderus Urungus went from a papier-mâché helmet to a latex-horned extreme.

The proximal distance between woods’ and his audience inches ever close—close, that is, but not too close. No Next-level poke coming through-ness. A double portion of protection for him and his psychic health. He doesn’t want to make it hard for himself. “My shell, mechanical,” he quotes a trusted source in a world full of leakers, snitches, and finks. But for all the attention (achtung baby!) paid to woods’ face/non-face, more eyes should be devoted to retina-scanning his verse. woods’ “love language [is] an obscure dialect,” but his delivery veils his technical prowess. woods raps with a cup-runneth-over flow where words spill over the edge of the bar, past the four, combined with conversational cadence and syntax.

Examine the second verse of “FaceTime.” woods’ sound devices and internal rhyming are in service to his theme, providing hand-holding to the listener as they walk the patterns together. The verse begins simple enough with a nursery rhyme sequence (“oboes…clarinet”; “rainbows…wept”) but almost immediately complexifies when the garbled /r/ begins to dominate with “Marrakech.” The alliterative /d/ [“dubstep drift in the window—I sit at my desk”] drags us to the “party outside,” away from our sanctuary of solitude. And the contraction of “Playboi Carti” leads to even more intense and immediate “partyin’” in the halls. woods brings us into the noise alongside him, even if we didn’t receive a formal invitation. The tumult of the scene is communicated through woods’ irregular pattern of internal and end-rhyme. “Phones,” “alone,” “home,” “cone,” and “blown” angle through the crowd, bumping and grinding against the dominate /r/ of “cardigan,” “origin,” “bar again,” “Parliament,” “parted,” “margarine,” “wandered in,” and “order” (or disorder, if I may). The sonorant pairing of “halls” &“walls” (destabilized by bass shakes); the triad of “melt,” “help,” & “pelts”; the trading of “chunky” & “clunky”; the bevy of /nk/ & /ng/ words (rings, ink, drink, ping, thinking, things, sink)—nothing saves us from the discomfiting experience described in the verse. We are subject to the final /r/ pairing of “tread water.” We’re exhausted by that point, and we drown.

Which way ought we go from here? Doesn’t much matter which way we go.

16. ODE ON INDOLENCE

“Soundcheck” is a reclamation of dignity. woods repeats his negative declaration (“I will not be at soundcheck”) four times throughout his verse, emphatically. Not since Bartleby have we heard such a vehement refusal. “I would prefer not to,” the scrivener says. woods’ refusal would make Paul Lafargue proud. It’s an unusual illusion that makes an MC believe he must puppet perform a phantom set for an audience of one, all in the name of amplification. It’s not that complicated. Organized Konfusion dealt with this shit in ’97. On “Soundman,” they summed it up nicely: If it ain’t loud enough, we tell the soundman turn that shit up, up, up. Tek and Steele embraced a more threatening approach. Exit the soundclash and enter the venue for a moment. Boom bye bye to a sound bwoy head. (Wiretap sound like Buju Banton, don’t it?) They demand a Sound [Man] Bureill.

woods craves his pre-show isolation: “I will not be in the green room if it’s too lit.” Are we talking incandescence or excitement? Either way, he wants none of it. Dah shinin’ of a spotlight in his face is not his style. His autonomy is the only item on his rider: “I reserve the right.” And that means no irksome obligations like soundcheck or backstage dawdling. He prefers to take in the town, a “local greasy spoon or Szechuan establishment,” maybe the Courtyard Marriott bathroom where he can “[blow] marijuana through the vents.” God-level expertise when it comes to that habit. We know from “No Hard Feelings” how he “towel[s] the door.”

He “might watch the sun set over your city from a parapet or a park bench.” woods considers the lilies and how they grow—they toil not, so why should he? We’ve seen him sitting there. We might’ve mistaken him for one of those Park Bench People that Freestyle Fellowship clued us into in 1993. “I see an old man sittin’ on a park bench,” Myka 9 sang, someone “lookin’ in the skies.” Might’ve been woods. “You’re thinkin’ ’bout your kids,” Myka said, “...’bout your girl, / You’re thinkin’ of all the things you did, / You see the children play.” woods wishes he was pushing his own baby on the swing, but he’s got to wait for that.

Time’s not lost completely. He will not be at soundcheck, but he will be timely for the show. You won’t find him “wakin’ up on a park bench a bum” (“The Doldrums”). “Headlamps splash squatter tents on my way to the venue,” woods raps, “—they wave me in.” Who exactly? The squatters or the show promoter? Who would he be more comfortable with? “I’m smiling like I’m not,” he says from the stage, spurning the coon caricature so many Black performers have thrust upon them by the public. woods won’t dance a jig, won’t step and fetch it. Not even when it’s time to get paid. “After the curtains, I sit for a while before I go get the check,” he explains. He turns merch tables on the promoter; makes him wait. Work slowdown. The pay is small, so take your time and buck them all, as the Wobblies used to say. Every live show forget the lyric, huh?—probably intentional. Don’t give them what they want. Withhold your labor. Set your terms.

17. THE CONQUEST OF BREAD

…For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

—Wendell Berry

If woods can’t escape the commotion of the show, he’ll wander even farther off. On “Agriculture,” he moves beyond space and time. If “Paraquat” argued “Anno Domini, it’s no before, it’s only after,” then “Agriculture” reassesses and finds there’s only before. “Nothing in the thought bubble,” woods mentioned on “Soft Landing,” which leads us to this meditation, this reverie of the before. Before what—the Fall? Christ? Facial recognition software? Tour? “Before history [History…], I made fire in the cave,” he raps on “The Layover.” A time before connotes premodern, Arcadian. “Agriculture” strings together a sequence of befores, each more lyrical than the prior (“lyrical” not in a Biggie “lyrical lyricist flowin’ lyrics out my larynx” sense, but in a Coleridge & Wordsworth way). woods wakes “before the sunrise,” even before nature awakens fully, “before sparrow cry from thistle.” He notes “the kettle boil before it whistle,” holding space in the quiet intensity. The personified night “fight before it die” and, consequently, the “sky bleed purple,” battered and bruised. woods leads us to a place (in stark contrast to a non-place) that knows him from “before [his] hands been dirty” with corruption—a place “before [he] could grasp time,” somewhere embryonic. He welcomes us to his Walden, to an unspoiled place “without any obstruction between us and the celestial bodies.” Here, the time is “before we had new names”—names like william woods, like F. Porter, like Madziwanyika. A time “before we was new in our own eyes”—before the mirror stage or interpellation.

To get there, woods has to travel to “parts unknown.” He’s only “at home when the road’s not paved.” He only asks for a “little piece of yard” where a “couple goats graze.” Sustainable living. Living that sustains. With a name like backwoodz, why wouldn’t the escape route point to the wilds? He retreats into the peace of wild things, as Wendell Berry calls it. There, woods can focus on [re]productivity. John McPhee, who has always had to balance teaching and writing, refers to his perennial phases as “crop rotations.” In the rural setting depicted on “Agriculture,” there are places enough for woods to push his plow. He retreats not out of complacency but out of a restorative need. He’s an ol’ dirty bastard, “squatting in the soil with a fistful.” CAN YOU DIG IT?! He channels Cyrus. He channels Kaczynski (and writes as much as him, too). “Agriculture” has a subtitle: Industrial Society and Its Future. “[T]echnology exacerbates the effects of crowding because it puts increased disruptive powers in people’s hands,” Kaczynski writes, staring at the whole entourage on the couch buried in they phones.