#mando’a orthography

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

C, cy, yc—why are they pronounced like that?

I think I’ve mentioned before that the rule is very nearly regular, so here it is. I’ve reproduced Traviss’s original pronunciation guides here (so you can see whether what I’m saying holds true).

c (without y) is pronounced as /s/ before high front vowels /e i/

cerar [sair-ARR]

ceratir [sair-AH-teer]

ceryc [sair-EESH]

cetar [set-ARR]

cetare [set-ARE-ay]

cin [seen]

cinargaanar [see-NAHR-gah-nahr]

cinarin [see-NAH-reen]

cin'ciri [seen-SEE-ree]

cinyc [SEE-neesh]

ciryc [seer-EESH]

mircin [meer-SEEN]

mircir [meer-SEER]

mirci't [meer-SEET]

racin [ray-SEEN]

tom'urcir [tohm-OOR-seer]

ver'mircit [VAIR-meer-seet]

otherwise as /k/

That is, before other vowels:

ca [kah]

cabuor [kah-BOO- or]

cabur [KAH-boor]

ca'nara [KAH-nah-RAH]

can'gal [CAHN-gahl]

carud [kah-ROOD]

ca'tra[KAH-tra]

cuir [COO-eer]

copaanir [KOH-pan-EER]

copad [KOH-pad]

copikla [koh-PEEK-lah]

copyc [KOH-peesh]

cu'bikad [COO-bee-kahd]

cunak [COO-nahk]

cuun [koon]

cuyan [koo-YAHN]

cuyanir [coo-YAH-neer]

cuyete [coo-YAY-tay]

cuyir [KOO-yeer]

cuyla [COO-ee-lah]

du'car [DOO-kar]

du'caryc [doo-KAR-eesh]

ge'catra [geh-CAT-rah]

jorcu [JOR-koo]

ori'copaad [OH-ree-KOH-pahd]

vencuyanir [ven-COO-yah-neer]

vencuyot [vain-COO-ee-ot]

vercopa [vair-KOH-pa]

vercopaanir [VAIR-koh-PAH-neer]

…and in a word-final position:

balac [bah-LAHK]

bic [beek]

ibac [ee-BAK]

ibic [ee-BIK]

norac [noh-RAK]

tebec [TEH-bek]

yc is always pronounced as /iʃ/

aikiyc [ai-KEESH]

aruetyc [AH-roo-eh-TEESH]

balyc [BAH-leesh]

beskaryc [BES-kar-EESH]

burk'yc [BOOR-keesh]

chakaaryc [chah- KAR-eesh]

copyc [KOH-peesh]

dalyc [DAH-leesh]

daryc [DAR-eesh]

diryc [DEER-eesh]

duumyc [DOO-meesh]

etyc [ETT-eesh]

gaht'yc [GAH-teesh]

gehatyc [geh-HAHT-eesh]

haamyc [HAH-meesh]

haatyc [HAH-teesh]

haryc [HAR-eesh]

hayc [haysh]

hetikleyc [hay-TEEK-laysh]

hettyc [heh-TEESH]

hodayc [HOH-daysh]

hokan'yc [hoh-KAH-neesh]

iviin'yc [ee-VEEN-esh]

jagyc [JAH-geesh]

jaon'yc [jai-OHN-ish]

jari'eyc [JAR-ee-aysh

jatisyc [jah-TEE-seesh]

johayc [JO-haysh]

kotyc [koh-TEESH]

kyr'adyc [keer-AH-deesh]

kyrayc [keer-AYSH]

kyr'yc [KEER-eesh]

laamyc [LAH-meesh]

lararyc [lah-rah-eesh]

majyc [MAH-jeesh]

morut'yc [moh-ROO-teesh]

narseryc [nar-SAIR-eesh]

nayc [naysh]

neduumyc [nay-DOO-meesh]

nehutyc [neh-HOOT-eesh]

nu'amyc [noo-AHM-eesh]

nuhaatyc [noo-HAH-teesh]

ori'beskaryc [OH-ree-bes-KAR-eesh]

ori'jagyc [OH-ree-JAHG-eesh (or OH-ree-YAHG-eesh)]

ori'suumyc [OHR-ee-SOOM-eesh]

oyayc [oy-AYSH]

piryc [PEER-eesh]

ramikadyc [RAH-mee-KAHD-eesh]

ret'yc [RET-eesh]

ruusaanyc [roo-SAHN-eesh]

sapanyc [sah-PAHN-eesh]

shaap'yc [sha-PEESH]

shi'yayc [shee-YAYSH]

shuk'yc [shook-EESH]

shupur'yc [shoo-POOR-esh]

sol'yc [sohl-EESH]

talyc [tahl-EESH]

tomyc [TOH-meesh]

tranyc [TRAH-neesh]

tratyc [TRAH-teesh]

tug'yc [too-GEESH]

ulyc [OO-leesh]

urcir [oor-SEER]

utyc [OO-teesh]

verburyc [vair-BOOR-eesh]

verd'yc [VAIR-deesh]

vutyc [VOOT-eesh]

yaiyai'yc [yai-YAI-eesh]

Note that this is still true when yc occurs in the middle of a word instead of the end:

barycir [bah-REE-shir]

besbe'trayce [BES-beh-TRAYSH-ay]

dirycir [DEER-ee-SHEER]

ke'gyce [keh-GHEE-shay]

majyce [mah-jEE-shay]

majycir [MAH-jeesh-eer]

mar'eyce [mah-RAY-shay]

mureyca [MOOR-aysh-ah]

cy is pronounced as /ʃ/

burc'ya [BOOR-sha]

burcyan [BOOR-shahn]

cyare [SHAH-ray]

cyare'se [shar-AY-say]

cyar'ika [shar-EE-kah]

cyar'tomade [SHAR-toe-MAH-day]

mirshmure'cya [meersh-moor-AY-shah]

murcyur [MOOR-shoor]

oyacyir [oy-YAH-sheer]

Ret'urcye mhi [ray-TOOR-shay-MEE]

sheb'urcyin [sheh-BOOR-shin]

sho'cye [SHOW-shay]

tracy'uur [trah-SHOOR]

Exceptions

The above holds true except for some exceptions:

The first is a group of words with a combination of u + yc:

buyca [BOO-shah]

buy'ce [BOO-shay]

buycika [BOO-she-kah]

This might be related to the status of /ui/ as a diphthong in Mando’a & could be a piece of evidence against it. What do I mean? Well, every instance of ⟨uy⟩ in the dictionary, Traviss breaks up in two syllables /u.i/. Could be there’s no diphthong /ui/ in Mando’a? However, I think it’s more likely this is because Traviss gives the pronunciations with an English orthography (i.e. how an English speaking reader would know to pronounce the words), and there’s no diphthong /ui/ in English, so in order to represent those sounds in English, they have to be broken up in separate syllables.

I also think the long /uː/ in buy’ce etc. is likely simply an elision: try going slowly from /u/ to /i/ to /ʃ/, and you’ll notice it’s easier to slip directly from /u/ to /ʃ/. I would generalise it as the diphthong /ʊɪ/ being realised as /uː/ before palatal consonants (at least; maybe others as well).

and:

buyacir [boo-ya-SHEER] /bʊ.ja.ˈʃiɾ/

Which has no excuse for being irregular except for influence on its spelling from buy’ce, so you could alternatively spell it as buyacyir or pronounce it as /bʊ.ja.ˈsiɾ/ (either would be regular).

The other exception to the rule is:

acyk [AH-seek]

The rule for this could be formulated as “if y is the only vowel in a syllable, it’s pronounced as /i/ and the pronunciation of c follows that.” Except for…

tracyn [trah-SHEEN]

Which itself could be analysed as a combination of the above rules: y as an only vowel gets pronounced as /i/, but the consonant in cy is still pronounced as /ʃ/ (in which case it would be acyk that is irregular instead).

It’s the derivations that appear irregular:

tracinya [trah-SHEE-nah]

tracyaat [tra-SHEE-at]

tra'cyar [tra-SHEE-ar]

Tracinya is plainly a derivation of tracyn, just spelled with an i instead of y. Interestingly, in Harlin’s Mando’a tracyn is pronounced as /tra.ʃin/ and tracinya as /tra.sin.ja/. So perhaps it’s acyk which should be pronounced as /a.ʃik/?

I’ve chosen to adjust the pronunciation of the other two to conform to the rule of pronouncing cy as /ʃ/: /tɾa.ˈʃaːt/ & /tɾa.ˈʃaɾ/.

And then:

yacur [YAH-soor]

Idek? I have do idea where this one comes from.

And:

Coruscanta [KOH-roo-SAHN-ta]

which is a loanword and doesn’t count. Although I’d suspect that “Corusanta” might be a fairly common misspelling among native speakers.

Explanation

So why is it pronounced like that? The explanation is something called palatalisation, which is the same reason why c in Latinate words is sometimes pronounced as /k/ and sometimes as /s/.

In very simple terms, the high front vowels and the semivowel /j/ are pronounced such that the tongue is at or very nearly the palatal position. So they tend to pull the preceding consonants to the palatal place of articulation (instead of whichever place of articulation they used to be pronounced at).

So in Mando’a:

c → k

c + high front vowel /i e/ → /s/

c + semivowel /j/ → /ʃ/

Not sure if /k/ is the original value of ⟨c⟩ since this rule doesn’t seem to apply to ⟨k⟩. Maybe ⟨c⟩ had originally another value, which has later changed into /k/?

There will be a second part to this post later, but I’ll break this off here for now.

#mando’a#mandoa#mando'a#Mando’a phonology#Ranah talks Mando’a#mando’a linguistics#Mando’a orthography#mando’a language

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s a revision to this theory. Apparently I went looking for fish further than the sea, as the saying goes. Mea culpa!

Mando’a sounds were influenced by Latin and Hungarian. Here’s what Karen Traviss says:

“Jess had to create lyrics that could be sung, because that was his primary objective, so he needed to get syllables to fit rhythms. But I needed to reconcile that with a structured grammar. Jess shared his thoughts with me about how he developed the sounds and I stuck with that softer sound he'd created. He took his sounds from Latin and Hungarian, and I added on some sounds from Urdu, Gurkhali and even Romany. I gave it a Hebrew rhythm and the end result sounds almost like Russian and Gaelic crossed with Hebrew.”

—Karen Traviss in Inside Mando’a Culture and Language

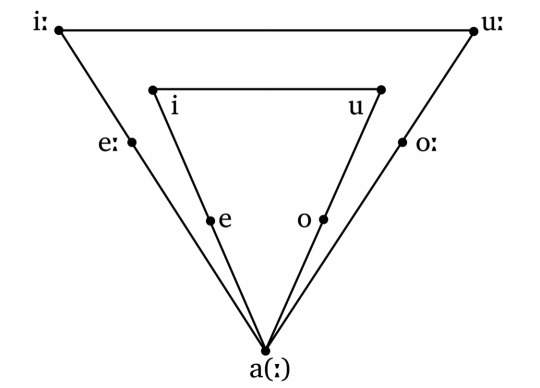

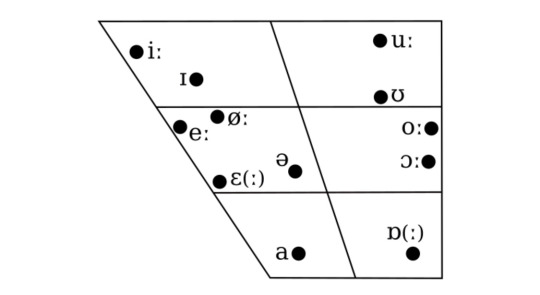

You know what Mando’a vowels look like? They look like this:

Distribution of Latin vowels according to William Sidney Allen's Vox Latina, p. 47. By Nicodene.

They look like Latin vowels, not like English ones.

Classical Latin short vowels /i e o u/ were probably pronounced with a relatively open quality, something like [ɪ] [ɛ] [ɔ] [ʊ] & the long vowels with a relatively close quality, something like [iː] [eː] [oː] [uː].

Classical Latin short vowel /i/ was similar in quality to the long /eː/ and the short /u/ was similar to the long /oː/. This is suggested by attested misspellings. — That explains why Mando’a spellings <ee> and <oo> are give pronunciations as "ee" (in English orthography) = /i/ and "oo" (English orthography) = /u/.

Hungarian has a different vowel system (with more than 5 vowels for one), but it too shows a similar phenomenon where long vowels are slightly higher than their short counterparts.

This has implications for Mando’a diphthongs as well, if we assume they were similarly influenced by the languages Mando’a was inspired by. I do not have the energy to write that analysis just now (because it ties to some other issues like palatals).

Mando’a phonotactics also show a clear inspiration from Latin, which Traviss apparently also knows.

p.s. A correction to the previous post: Traviss is a Portsmouth native, not Tyneside. I don’t know where she got the Tyneside inspiration from.

Kaa's Grudge-Match With Mando'a Pronunciation

KT is no Tolkien, okay. She did a decent job with the language and worldbuilding, for which I thank her from the bottom of my heart, but her pronunciations are, to put it delicately, irregular. I’m willing to tolerate some of it - but certainly not all of it.

Keep reading

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

etaoin arieu’t

Most of the time I use vulgarlang to generate languages, since I can stay phonologically consistent across a culture while being ratshit at making up words. Staring at its blessedly low-effort output, I got curious about Mando’a, one of Star Wars’ most famous conlangs. The easiest thing to do seemed to be to grab the list of words from mandoa.org, so I did. After scrubbing it a bit for punctuation marks - not the comma - I ran it through a couple of analysis tools to see how it’s different from English, and what other characteristics it might have. If anyone’s got any longer Mando’a texts, please flick me a link even if it contains user invented words. I’d be interested to see how different they are.

The first thing was a frequency analysis. For instance, in a plain English text, 12.7% of all letters will be an E, while very few will be an X. In Mando’a, 17.14% of all letters will be an A, and very few will be a W.

The twelve most frequent letters in English, in order, are: ETAOIN SHRDLU. In Mando’a, they’re ARIEU‘T ONSLY. Until now, I hadn’t noticed that Traviss’s Mando’a doesn’t actually contain an F, and I think but can’t find a reference for, that she said Fett is derived from vhett, meaning farmer. Mando’a has no Z either, which could be a nice bit of world-building regarding Satine Kryze perhaps coming from another population altogether (like the Norman French after 1066) but almost certainly isn’t. There are also no letters for X or Q.

After that, I did a sliding bigram analysis. This scans through the text looking for which two letters are most likely to appear next to each other. In English, the six most common are TH, HE, IN, ER, AN and RE. Interestingly, for a language created by someone called Karen, Mando’a has AR, IR, AA, RA, KA, and AN.

K itself is nearly seven times more likely to appear in Mando’a than it is in English. People do tend to prefer the letters in their name over other letters in the alphabet, so this isn’t quite as egotistical as you might assume. It’s the thirteenth most common letter in Mando’a, half way down the frequency list.

Even though the letters don’t appear in written Mando’a, the sounds for F, Q, X, and Z might be present in spoken Mando’a. However, I tend to headcanon them as too pragmatic to put up with an orthography as horrifying as English’s, so for me this now means that someone with a heavy Mando accent would curse vhiervhek about the vhekking banta vhodder. That’s not a typo in bantha; Mando’a is missing TH as a bigram and presumably as a phoneme as well.

I have no idea why she chose these letters to leave out while leaving the rhotics in. F itself occurs about 2.2% of the time in English, the 15th most common letter, but the bigram VH that she implies replaced it is only the 171st most frequent one in Mando’a, showing up 0.16% of the time. Odd, since it’s in the name belonging to the most famous Mandos of them all.

Although this analysis is based on Mando’a orthography, it suggests a restricted number of phonemes. The pronunciation guide limits that even more. I couldn’t find any Mando written in IPA, although some poor sod has probably tried it. At some point in the future I might try and figure out how many phonemes it has, compared to real-world languages and other conlangs, like Klingon and Dothraki.

There’s no real conclusion here, except that it hasn’t escaped my notice that the seven most common letters in Mando’a, ARIEU’T, are similar to the word for traitor, foreigner, outsider: aruetii, which could be a bemusing in-universe cultural artifact, and that double letters don’t seem to mean anything, pronunciation-wise, so why is the third most common bigram AA when it doesn’t denote a long vowel or anything useful?

(and if Etain’s name came from ETAOIN?)

#mando'a#travissity#frequency analysis#sliding bigrams#orthography#conlangs#vulgarlang#questionable methodology#graphs available on request#ditto outputs#more texts please#and ipa orthography#press V and H to pay respects

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

riduurok

What’s the etymology of riduurok? Well, here’s a favourite little pet theory of mine.

Let’s see what parts of riduurok we can find in other words. Obviously there’s riduur, ‘spouse’. But what about “rok”? Well, I think it’s kom’rk, ‘vambrace’. See, kom’rk also more plainly occurs in shuk’orok, ‘crushgaunt’—but there it’s orok, not “rk”. And I think that word is kind of like kar’ta, which is also sometimes pronounced as “karota”: it has dropped some vowels along the way. This is confirmed by the pronunciation, which is given as “KOHM-or-rohk”. I reconstruct the original form as orok (i.e. vowels intact).

Making riduurok something like rid-orok. And what do vambraces have to do with marriage? They’re exchanged, making *rid- something like “to exchange, swap” and riduurok “to exchange vambraces”. Riduur would then literally mean “one who exchanges”, i.e. the person with whom one exchanges armour.

P.s.

What does kom in kom-orok mean? I’ve no idea, but I’d like to hear suggestions. It looks like orok was originally a word that meant either a gauntlet or a vambrace, and then later we have a compound kom-orok meaning ‘vambrace’ and shuk-orok meaning ‘crush-gauntlet’. Perhaps “cuff”, as in a long cuff that extends from the gauntlet to cover the forearm? Something else?

P.p.s.

As an aside, I kind of have a problem with the spelling of kom’rk. It’s unnecessarily irregular and doesn’t correspond to the pronunciation, which is really just bad orthography. Maybe it’s supposed to look exotic? Idek. It’s also one of the very few words that doesn’t agree with the overall patterns of Mando’a phonotactics. I’ve added kom’rok and kom’orok as alternative spellings in my dictionary, and I’ve half a mind to make one of them the primary spelling.

#mando’a#mandoa#mando'a#mandalorians#mando’a language#mando’a etymology#mando’a linguistics#Ranah talks mando’a#riduurok

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

So canon Mando’a is pretty clearly affected by English, and not in a good way. And I want to fix that in my revision, obviously. I’m in no way the first one to attempt that. I kind of need to make a decision how to go about it, though.

The question is, which one should I work from, pronunciation or orthography? That is, should I assume that the written form is “correct” and KT’s pronunciation was affected by her native English, or that her pronunciation is correct and her transliterations were affected by English spelling conventions? That both are affected and the “correct” is something else? Should I work out both versions and see where they do/don’t agree? Maybe I could learn something, or maybe I would just have two versions to choose from?

I’m leaning towards working out both because I can’t decide, but I’d be happy to hear any thoughts or ideas.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This post has outgrown the 100 link limit; more links under the cut.

General

On Mando’a terminology: affixes and clitics

Phonology

IPA chart (I’m going to be reworking this, but it’ll suffice for now)

C, cy, yc—why are they pronounced like that? — Pronunciation of y — A theory of -yc, -cy-, -cya and -cye — More palatalisations — More palatalisations & how they could explain the problem of murmured sounds (my overarching theory on how to explain all the weirdness of Mando’a orthography)

Phonotactics & epenthetic sounds

Loanword phonology (discussion)

Concordian Mando’a

Morphology

Mando’a nominal suffixes & a work in progress on how they might be chosen

*da-, ‘out’ (prefix)

*je-, ‘false, un-’ (prefix)

*she-, ‘behind’ (prefix)

u(r)-, ‘less’ (prefix)

Re- in Mando’a? (reduplication again)

Syntax

Mando’a prepositions

Habitual aspect (fanon)

Articles: eyn, te, haar

Relative pronouns, relative adverbs, interrogatives (question words)

Etymology (canon words)

*ara-/*aru-, ‘away’ or ‘against’? & again here

*ak-, ‘mission’ (aka, akaan, etc.) & hokaanir, ‘to cut’ (+ related words)

*ay(l)-, ‘sweet’ & ‘sticky’

*bin-, ebin, bintar, bines

*bid-, *bi-, *bin-, *bir-

briikase, ‘happy’

dadita (the best analysis not by me, scroll to the end)

*da-, ‘out’ (dayn, davaab, dajun)

eyn & solus

*je-, ‘false, un-’ (jekai, jehaat, jahaatir, jaal, jehavey’ir)

kelita, dab’ika, keldab

*nar-, ’move, action, act’ (nari, narir, lonar, shonar, jenarar, cetar’narir, muninar, naritir, narser, nasreyc, ashnar, nar’sheb, ca’nara)

oyu’baat

ramikad, ‘commando’ & ori’ramikad, ‘super commando’

rejorhaa’ir, ‘to tell’ (not solved, tell me your ideas)

*she-, ‘behind’ (shebs, sheber, shekemir, shereshir, shereshoy)

sterebiise & geroya be haran, alii’jaate, naast

u(r)-, ‘less’ (ures, umaan, urakto, urmankalar, utreeyah, utreyar, utrel’a)

English etymologies in Mando’a (not my post, but I’ve added several more in the replies)

Open etymology questions (gimme your ideas!)

Non-canon vocabulary

Also in the reblogs of the above etymology posts!

alii’gai, alii’gaise, alii’gaila; extended definitions

doyust, ‘bridge’

gi’gaide, ‘fish scales’ (here’s another idea for the same pattern, not mine)

mana, ‘origin, source; mine’

*ram-, ram’ika, ramikad, ramikaar

shiik, ‘noodle’

taylaar, ‘book’

Te Yaim’ol & Naak’tsad

utra, ‘emptiness, void’ (not sure this is mine, might have adopted it from someone else’s dictionary)

“Bless you” or “gesundheit” in Mando’a

Loanwords in Mando’a (headcanon)

#History, #culture, #religion, #philosophy, #headcanons, &c.

History of the Mandalorian peace movement (conjecture & headcanons)

The Mandalorian Proletarian Uprising (complete and unabashed headcanons)

New Mandalorians and armour (headcanons)

Kad Ha’rangir & slash and burn agriculture

Stuff I’m working on

Mando’a Derivational Dictionary — current priority

Canon Mando’a analysis: project outline — sometime this century

@mandoxember — coming, hopefully maybe next year

FAQ

Blog runs mostly on queue and I’m currently pretty busy at work (and not spending a lot of time hanging out here). Send me a dm if you want to hail me.

If I liked it, likely I also queued it. Or put it in the drafts because I had something to say that I had to mull over a bit.

Why haven’t you answered my comment/ask/question? It’s either in my queue, lost in my drafts, eaten by my inbox, or I forgot. Feel free to resend/ask again/send me a dm.

Do you do translations? Feel free to send me asks if you have something fun but don’t expect a speedy reply.

You seem very confident in your analyses, what’s your source? Just canon, some interviews by Traviss and Harlin, and Traviss’s blog and comments in some forum threads. No special word of god here! Just a lot of extrapolation and some previous linguistics and conlanging knowledge. I have made a (atm incomplete) systematic analysis of Mando’a, but I’m just a human and I might have drawn incorrect conclusions—you’re very welcome to debate me and add your contradictory opinions. Most of the stuff I post are my own interpretations which you’re welcome to adopt, but I can’t claim to hold the one and only truth. And yes, the title of this blog is picked because I know I can be an annoying little mir’shebs when I think I’m right. But I do genuinely enjoy hearing other opinions and getting my own ones challenged, even if the tone does not always come across in text. If I haven’t reblogged your contrary opinion, it’s because the reply got long and it’s in my drafts somewhere, or else I’m still mulling it over.

Please don’t send me asks for money. I don’t currently have any to spare, nor do I have time to vet gofundmes. I do what I can, and donate what I can, when I can, to effective humanitarian organisations. Sorry I can’t help more.

Mando’a masterpost

Most of my Mando’a linguistic nerdery you should be able to find under the hashtags #mando’a linguistics and #ranah talks mando’a. Specific topics like phonology and etymology are tagged on newer posts but not necessarily on older. I also reblog lots of other people’s fantastic #mando’a stuff, which many of these posts are replies to.

I also post about #mandalorian culture, other #meta: mandalorians and #star wars meta topics, #star wars languages, #conlangs, and #linguistics. I like to reblog well-reasoned and/or interesting takes on Star Wars and Mandalorian politics, but I am not pro or contra fictional characters or organisations, only pro good storytelling. You can use the featured tags to navigate most of these topics. Not Star Wars content tag is #not star wars, although if it’s on this blog, likely it’s at least tangentially related.

Currently working on an expanded dictionary and an analysis of canon Mando’a. Updates under #mando’a project. Here are my thoughts on using my stuff (tldr: please do). My askbox is open & I’d love to hear which words, roots or other features you want to see dissected next.

#Phonology

Mando’a vowels

Murmured sounds in Mando’a

Ven’, ’ne and ’shya—phonology of Mando’a affixes

#Morphology

Mando’a demonyms: -ad or -ii?

Agent nouns in Mando’a

Reduplication in Mando’a

Verbal conjugation in Ancient Mando’a & derivations in Modern Mando’a

-nn

Adjectival suffixes (this one is skierunner’s theory, but dang it’s good and it’s on my post, so I’m including it)

e-, i- (prefix) “-ness”

#Syntax

Middle Mando’a creole hypothesis — Relative tenses — Tense, aspect and mood & creole languages — Copula and zero copula in creole languages — More thoughts about Mando’a TAM particles

Mando’a tense/aspect/mood (headcanons)

Mando’a has no passive

Adjectives as passive voice & other strategies

Colloquial Mando’a

Alienable/inalienable possession — more thoughts

Translating wh-words into Mando’a

#Roots, words & etymology

ad ‘child’—but also many other things

adenn, ‘wrath’

akaan & naak: war & peace

an ‘all’ + a collective suffix & plural collectives

ba’ & bah

*bir-, birikad, birgaan & again

cetar ‘kneel’

cinyc & shiny

gai’ka, ka’gaht, la’mun

jagyc, ori’jagyc & misandry

janad

*ka-, kakovidir & cardinal directions

ke’gyce ‘order, command’

*maan-, manda, gai bal manda, kir’manir, ramaan & kar’am & runi: ‘soul’ & ‘spirit’

*nor- & *she- ‘back’ (+ bonus *resh-)

projor ‘next’

riduurok, riduur, kom’rk, shuk’orok

*sak-, sakagal ‘cross’

*sen- ‘fly’

tapul

urmankalar ‘believe’

*ver- ‘earn’

*ya-, yai, yaim (& flyby mentions of eyayah, eyaytir, gayiyla, gayiylir, aliit)

Regional English in Mando’a

#Non-canon words

Mining vocabulary

Non-canon reduplications

Many words for many Mandalorians

What’s the word for “greater mandalorian space”?

Names of Mandalorian planets

Dral’Han & derived words

besal ‘silver, steel grey’

derivhaan

hukad & hukal, ’sheath, scabbard’

*maan-, manda, kar’am & runi: ‘soul’ & ‘spirit’ & derivations

mara/maru, ‘amber-root’

*sen- ‘fly’ derivations

tarisen ‘swoop bike’

*ver- ‘earn’ derivations

#mando’a proverbs

#mando’a idioms

Pragmatics & ethnolinguistics

Middle Mando’a creole hypothesis

History of Mando’a — Loanwords in Mando’a

Mando’a timeline

Mandalorian languages

#mandalorian sign language

Kinship terms

Politeness in Mando’a: gedet’ye & ba’gedet’ye — vor entye, vor’e, n’entye — vor’e etc. again — n’eparavu takisit, ni ceta

Mandalorians and medicine, baar’ur, triage

#Mandalorian colour theory (#mandalorians and color): cin & purity, colour associations & orange, cin, ge’tal, saviin & besal, gemstone symbolism

#Mandalorian nature, Flora and fauna of Manda’yaim

starry road

Concordian dialogue retcon

A short history of the Mandalorian Empire

Mandalorian clans & government headcanons

Mando’a handwriting guide: part 1, part 2, part 3

What I would have done differently if I had constructed Mando’a

FAQ

Can you answer a question about combat medicine? May I direct you to my post about Free tactical medicine learning resources.

Can I use your words/headcanons in my own projects? Short answer: yes please.

Do you do translations? If I happen to be in the mood or your translation question is interesting. Feel free to bomb my inbox, but don’t expect quick answers.

What’s your stance on Satine Kryze and the New Mandalorians? They’re fictional and I don’t have one beyond their narrative being interesting & wishing that fandom would have civil conversations about them without calling each other names.

Why do you portray Mandalorians as multi-racial and gender-agnostic when they’re all white men in canon? Because that’s the power of transformative works: to create the kind of representation we want to see in a world where it’s lacking.

LGBTQIA? I don’t stand for any shade of discrimination. If I say something insensitive, rest assured it’s because I temporarily misplaced my other brain cell, not because of malice.

NSFW? No. This is a linguistics blog, so cursing and some frank vocabulary should be expected, but no porn here. I don’t believe in nudity or sex in themselves being taboo topics, but I’ll try to keep things family-friendly. I was a medic for a good chunk of my life, so frank discussions about medical/anatomical/trauma topics might also happen, which may or may not be tagged.

Asks under #ranah answers

P.s. Let me know if the links don’t work or something else is wrong (some items don’t have links, they are articles in my draft folder/queue which I’ve listed here so they don’t get lost—sorry for the tease!). Also please tell me if you need me to tag something I haven’t so you can filter it: this blog is for readers—if I was writing just for myself, I wouldn’t bother to edit and publish—so let me know what I can do to make it work better for you. Thanks!

#star wars#mandalorians#star wars meta#mando’a#mandoa#mando'a#mando’a language#conlang#mando’ade#mandoa language#ranah talks mando’a#mando’a linguistics#mandoa resources

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

@sootships Actually, I think the vowel quality *just might* be significant based on Traviss’s pronunciation guides. Or at least, one way to make sense of them would be a similar system to Latin vowels. But it’s admittedly not the easiest to tease out, because there’s the fact that Traviss have her pronunciations in English orthography which… is not great. It’s been a job and a half to work out what might be an artefact of English and what might be an actual property of Mando’a phonology. Any result there is going to require some degree of interpretation, I’m afraid.

random thonk: i guess short and long vowels aren't super meaningful (i forget the fancy linguistics terminology for what i mean but i figure u catch what i mean) since a lot of roots have derivations where the vowel is either long or short... and i guess they must not be quality-wise super different since there doesn't seem to be instances of, say, aa turning into o or oo toruning into u etc (which has happened in latin)

Yep, the only way I could make any headway with the etymologies was disregarding vowel length. After that it became much easier.

It doesn’t necessarily mean that vowel length is not phonemic in Modern Mando’a, but it certainly seems to indicate that it wasn’t phonemic at some point in its past. But idk, I’m still figuring out what would make most sense with that.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

And now for the third part where I have some theories. There will also be a fourth with still more theories.

A theory about -yc, -cy-, -cye and -cya

There are two adjectival suffixes in Mando’a: -la and -yc. You’ll often see -la reduced to just an -l- in compound words. But what about -yc?

Well, what I think happens it gets reduced to just /ʃ/… which is spelled as ⟨cy⟩.*

And you know how Mando’a uses the plural suffix to derive nouns from other word classes?

I think -cya and -cye are effectively combinations of -yc + either the archaic plural suffix -a or the modern -e. (Well, -a also seems to be a regular nominal suffix I guess, but the phonological process would be the same.) Meaning that nouns that end in -cya or -cye were probably derived from adjectives ending in a regular -yc.

This theory btw only accounts for words where the cy can be analysed as a suffix, but not for e.g. cyare. So it’s a special case of why cy is pronounced that way, rather than the full explanation.

More palatalisation

To be clear, this is where I veer from analysis to creative interpretation in an attempt to make Mando’a make sense as a language.

Well, is it only this one sound (whatever sound c used to be) that’s affected by palatalisation?

There are no other consonants that would display this kind of a phenomenon where they change pronunciations based on what follows.

There are, however, other consonants that are followed by the semivowel y. So how ought those be pronounced? Are they palatalised? Or if not full-on palatalised (as in the sound change), maybe palatalised (as in secondary articulation)? Maybe either or anything in between is possible, depending on the dialect.

entye[ENT-yeh]

Ba'gedet'ye![BAH-geh-DET-yeh]

Gedet'ye[Geh-DET-yay]

⟨ty⟩ could be /tʲ/ or /c/, /t͡ʃ/ or /t͡ɕ/

kyor[KIE-ohr]

kyorar[KIE-ohr-ar]

kyorla[kie-OHR-lah]

⟨ky⟩ could be /kʲ/ or /c/, /t͡ʃ/ or /t͡ɕ/ (yes, it’s the same set as for ty—these often merge in languages with this phenomenon)

tracinya[trah-SHEE-nah]

Usen'ye![oo-SEN-yeh]

⟨ny⟩ could be /nʲ/ or /ɲ/, like the Spanish ñ.

chaashya[cha-SHEE-ah]

dralshy'a[drahl-SHEE-ya]

dush'shya (doshishya)[doo-SHEESH-ya]

jate'shya[JAH-tay-SHEE-ah]

ori'shya[ohr-EE-she-ya]

⟨shy⟩ could be /ʃʲ/ or /ɕ/, although Traviss’s pronunciations seem to suggest ‘shya has two syllables. However, see my commentary in the first post on the problems of using English orthography to represent the sounds of another language.

Also these “ya” sounds apparently were originally inspired by Russian**, where they are not diphthongs but palatalised sounds. So that’s the interpretation I’m inclined to go with. It also fits nicely in my phonotactics draft.

* cy might also represent /ʃʲ/ or /ɕ/ rather than /ʃ/, but obviously Traviss’s pronunciation guide wouldn’t be able to represent this difference.

I think palatalisation (however it is realised exactly) is phonemic in Mando’a, i.e. for example kyor and kor would be recognised as different words.

These (plus c) are the only consonants appearing before the y in canon. Perhaps palatalisation is restricted to them, or perhaps it could affect most (but not necessarily all) consonants. Slavic languages certainly have a wide variety of palatalised consonants, although there are also languages with much smaller sets.

** According to David Collins, the audio lead of Republic Commando games in this group interview with Harlin, though as far as I can tell, Harlin himself has directly only admitted to being inspired by Latin, Hungarian, and soviet anthems (see e.g. this interview, although he mentions it in several different interviews), and listening a lot of Hungarian, Russian, and Romanian (see the first link). If anyone has an interview or another source stating differently or adding more support, please send it my way!

In the next part, I’ll elaborate on palatalisation of different consonants and how that could also explain another thorny problem of Mando’a orthography…

C, cy, yc—why are they pronounced like that?

I think I’ve mentioned before that the rule is very nearly regular, so here it is. I’ve reproduced Traviss’s original pronunciation guides here (so you can see whether what I’m saying holds true).

c (without y) is pronounced as /s/ before high front vowels /e i/

cerar [sair-ARR]

ceratir [sair-AH-teer]

ceryc [sair-EESH]

cetar [set-ARR]

cetare [set-ARE-ay]

cin [seen]

cinargaanar [see-NAHR-gah-nahr]

cinarin [see-NAH-reen]

cin'ciri [seen-SEE-ree]

cinyc [SEE-neesh]

ciryc [seer-EESH]

mircin [meer-SEEN]

mircir [meer-SEER]

mirci't [meer-SEET]

racin [ray-SEEN]

tom'urcir [tohm-OOR-seer]

ver'mircit [VAIR-meer-seet]

otherwise as /k/

That is, after other vowels:

ca [kah]

cabuor [kah-BOO- or]

cabur [KAH-boor]

ca'nara [KAH-nah-RAH]

can'gal [CAHN-gahl]

carud [kah-ROOD]

ca'tra[KAH-tra]

cuir [COO-eer]

copaanir [KOH-pan-EER]

copad [KOH-pad]

copikla [koh-PEEK-lah]

copyc [KOH-peesh]

cu'bikad [COO-bee-kahd]

cunak [COO-nahk]

cuun [koon]

cuyan [koo-YAHN]

cuyanir [coo-YAH-neer]

cuyete [coo-YAY-tay]

cuyir [KOO-yeer]

cuyla [COO-ee-lah]

du'car [DOO-kar]

du'caryc [doo-KAR-eesh]

ge'catra [geh-CAT-rah]

jorcu [JOR-koo]

ori'copaad [OH-ree-KOH-pahd]

vencuyanir [ven-COO-yah-neer]

vencuyot [vain-COO-ee-ot]

vercopa [vair-KOH-pa]

vercopaanir [VAIR-koh-PAH-neer]

…and in a word-final position:

balac [bah-LAHK]

bic [beek]

ibac [ee-BAK]

ibic [ee-BIK]

norac [noh-RAK]

tebec [TEH-bek]

yc is always pronounced as /iʃ/

aikiyc [ai-KEESH]

aruetyc [AH-roo-eh-TEESH]

balyc [BAH-leesh]

beskaryc [BES-kar-EESH]

burk'yc [BOOR-keesh]

chakaaryc [chah- KAR-eesh]

copyc [KOH-peesh]

dalyc [DAH-leesh]

daryc [DAR-eesh]

diryc [DEER-eesh]

duumyc [DOO-meesh]

etyc [ETT-eesh]

gaht'yc [GAH-teesh]

gehatyc [geh-HAHT-eesh]

haamyc [HAH-meesh]

haatyc [HAH-teesh]

haryc [HAR-eesh]

hayc [haysh]

hetikleyc [hay-TEEK-laysh]

hettyc [heh-TEESH]

hodayc [HOH-daysh]

hokan'yc [hoh-KAH-neesh]

iviin'yc [ee-VEEN-esh]

jagyc [JAH-geesh]

jaon'yc [jai-OHN-ish]

jari'eyc [JAR-ee-aysh

jatisyc [jah-TEE-seesh]

johayc [JO-haysh]

kotyc [koh-TEESH]

kyr'adyc [keer-AH-deesh]

kyrayc [keer-AYSH]

kyr'yc [KEER-eesh]

laamyc [LAH-meesh]

lararyc [lah-rah-eesh]

majyc [MAH-jeesh]

morut'yc [moh-ROO-teesh]

narseryc [nar-SAIR-eesh]

nayc [naysh]

neduumyc [nay-DOO-meesh]

nehutyc [neh-HOOT-eesh]

nu'amyc [noo-AHM-eesh]

nuhaatyc [noo-HAH-teesh]

ori'beskaryc [OH-ree-bes-KAR-eesh]

ori'jagyc [OH-ree-JAHG-eesh (or OH-ree-YAHG-eesh)]

ori'suumyc [OHR-ee-SOOM-eesh]

oyayc [oy-AYSH]

piryc [PEER-eesh]

ramikadyc [RAH-mee-KAHD-eesh]

ret'yc [RET-eesh]

ruusaanyc [roo-SAHN-eesh]

sapanyc [sah-PAHN-eesh]

shaap'yc [sha-PEESH]

shi'yayc [shee-YAYSH]

shuk'yc [shook-EESH]

shupur'yc [shoo-POOR-esh]

sol'yc [sohl-EESH]

talyc [tahl-EESH]

tomyc [TOH-meesh]

tranyc [TRAH-neesh]

tratyc [TRAH-teesh]

tug'yc [too-GEESH]

ulyc [OO-leesh]

urcir [oor-SEER]

utyc [OO-teesh]

verburyc [vair-BOOR-eesh]

verd'yc [VAIR-deesh]

vutyc [VOOT-eesh]

yaiyai'yc [yai-YAI-eesh]

Note that this is still true when yc occurs in the middle of a word instead of the end:

barycir [bah-REE-shir]

besbe'trayce [BES-beh-TRAYSH-ay]

dirycir [DEER-ee-SHEER]

ke'gyce [keh-GHEE-shay]

majyce [mah-jEE-shay]

majycir [MAH-jeesh-eer]

mar'eyce [mah-RAY-shay]

mureyca [MOOR-aysh-ah]

cy is pronounced as /ʃ/

burc'ya [BOOR-sha]

burcyan [BOOR-shahn]

cyare [SHAH-ray]

cyare'se [shar-AY-say]

cyar'ika [shar-EE-kah]

cyar'tomade [SHAR-toe-MAH-day]

mirshmure'cya [meersh-moor-AY-shah]

murcyur [MOOR-shoor]

oyacyir [oy-YAH-sheer]

Ret'urcye mhi [ray-TOOR-shay-MEE]

sheb'urcyin [sheh-BOOR-shin]

sho'cye [SHOW-shay]

tracy'uur [trah-SHOOR]

Exceptions

The above holds true except for some exceptions:

The first is a group of words with a combination of u + yc:

buyca [BOO-shah]

buy'ce [BOO-shay]

buycika [BOO-she-kah]

This might be related to the status of /ui/ as a diphthong in Mando’a & could be a piece of evidence against it. What do I mean? Well, every instance of ⟨uy⟩ in the dictionary, Traviss breaks up in two syllables /u.i/. Could be there’s no diphthong /ui/ in Mando’a? However, I think it’s more likely this is because Traviss gives the pronunciations with an English orthography (i.e. how an English speaking reader would know to pronounce the words), and there’s no diphthong /ui/ in English, so in order to represent those sounds in English, they have to be broken up in separate syllables.

I also think the long /u:/ in buy’ce etc. is likely simply an elision: try going slowly from /u/ to /i/ to /ʃ/, and you’ll notice it’s easier to slip directly from /u/ to /ʃ/. I would generalise it as the diphthong /ʊɪ/ being realised as /uː/ before palatal consonants (at least; maybe others as well).

and:

buyacir [boo-ya-SHEER] /bʊ.ja.ˈʃiɾ/

Which has no excuse for being irregular except for influence on its spelling from buy’ce, so you could alternatively spell it as buyacyir or pronounce it as /bʊ.ja.ˈsiɾ/ (either would be regular).

The other exception to the rule is:

acyk [AH-seek]

The rule for this could be formulated as “y is the only vowel in a syllable, it’s pronounced as /i/ and the pronunciation of c follows that.” Except for…

tracyn [trah-SHEEN]

Which itself could be analysed as a combination of the above rules: y as an only vowel gets pronounced as /i/, but the consonant in cy is still pronounced as /ʃ/ (in which case it would be acyk that is irregular instead).

It’s the derivations that appear irregular:

tracinya [trah-SHEE-nah]

tracyaat [tra-SHEE-at]

tra'cyar [tra-SHEE-ar]

Tracinya is plainly a derivation of tracyn, just spelled with an i instead of y. Interestingly, in Harlin’s Mando’a tracyn is pronounced as /tra.ʃin/ and tracinya as /tra.sin.ja/. So perhaps it’s acyk which should be pronounced as /a.ʃik/?

I’ve chosen to adjust the pronunciation of the other two to conform to the rule of pronouncing cy as /ʃ/: /tɾa.ˈʃaːt/ & /tɾa.ˈʃaɾ/.

And then:

yacur [YAH-soor]

Idek? I have do idea where this one comes from.

And:

Coruscanta [KOH-roo-SAHN-ta]

which is a loanword and doesn’t count. Although I’d suspect that “Corusanta” might be a fairly common misspelling among native speakers.

Explanation

So why is it pronounced like that? The explanation is something called palatalisation, which is the same reason why c in Latinate words is sometimes pronounced as /k/ and sometimes as /s/.

In very simple terms, the high front vowels and the semivowel /j/ are pronounced such that the tongue is at or very nearly the palatal position. So they tend to pull the preceding consonants to the palatal place of articulation (instead of whichever place of articulation they used to be pronounced at).

So in Mando’a:

c → k

c + high front vowel /i e/ → /s/

c + semivowel /y/ → /ʃ/

Not sure if /k/ is the original value of ⟨c⟩ since this rule doesn’t seem to apply to ⟨k⟩. Maybe ⟨c⟩ had originally another value, which has later changed into /k/?

There will be a second part to this post later, but I’ll break this off here for now.

#mando’a orthography#mando’a#ranah talks mando’a#mando’a phonology#mando’a linguistics#mando’a language#mandoa#mando'a

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

More palatalisations & how they could explain the problem of murmured sounds

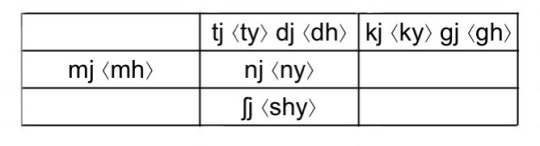

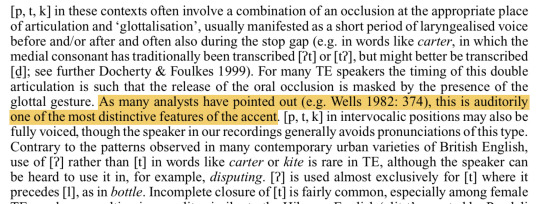

Okay, so: Mando’a has these spellings ⟨dh⟩ (dha), ⟨gh⟩ (ghett), and ⟨mh⟩ (mhi) where the h seems to suggest aspiration. But the problem is that that is a very weird set of consonants to be aspirated: I know of no language that would only contrast between aspirated and unaspirated voiced stops and not make the same contrast for unvoiced stops as well. (Except for the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European, but there as well this exact issue is a problem that has bugged linguists forever.)

But then, while I was formulating my palatalisation theories, I found out that ⟨mh vh bh nh lh⟩ are spellings that actually have been used by natural languages to spell /mj vj bj nj lj/. And you know what? That spelling makes perfect sense: palatalised voiced stops don’t sound exactly like murmured (i.e. aspirated voiced) sounds… but they also don’t sound exactly unlike them. There’s a bit of a puff of air, more than with the unvoiced consonants. And this could explain why Mando’a has dh but not th, and ty but not dy.

So we have a bit of a mismatched set of spellings:

… but as you see, together they make a complimentary set.

(Okay, this set is a bit incomplete; I’ll have to leave the task of completing it to a later post because it got very long and very rambling.)

So how are dh, gh, mh pronounced then?

On the Republic Commando soundtrack, mhi is pronounced as /mi/ and dha as /da/. On Traviss’s recordings, neither word makes an appearance so we don’t know how she would pronounce them. Her pronunciation guide gives:

dha[dah]

mhi[mee]

It appears that the extra h does not affect pronunciation.

In Romance languages for example, /gj/ became /j/ or /dʒ/ (so that would be ⟨y⟩ or ⟨j⟩ in Mando’a orthography), and /dj/ became /dz/ or /j/. But maybe in Mando’a they did something else: instead of strengthening, they became weaker, first becoming aspirated, and then losing the aspiration too:

/dʲ/ > /dʰ/ > /d/

/ɡʲ/ > /ɡʰ > /g/

/mʲ/ > /mʰ/ > /m/

A range of these gradations might exist along the different dialects. Perhaps the spelling ⟨dh gh mh⟩ became standardised at a time when that was the prevailing pronunciation among whichever dialect was the most prestigious one at the time.

Conclusion

So there you have it: my best damn attempt to make the weirdness of Mando’a orthography make sense.

I can’t know whether this is what the original authors (Jesse Harlin and Karen Traviss) intended. But as always, my primary goal is to make sense of the corpus of Mando’a that exists in a way that is linguistically plausible. Authorial intent is secondary to me, although I do use that as guidance whenever there is an interview or some source to guide me and I can make it fit & make sense.

Out of Harlin’s inspirations, Russian, Hungarian and Romanian exhibit at least some palatalisation, so the words that were already present in the Repcomm soundtrack (e.g. dha, mhi, tracinya, dralshy’a) could have gotten their sounds from there. Neither of the additional inspirational languages (Romani and Nepali) Traviss has mentioned has palatalised consonants, but Nepali does have murmured ones. So the additional sounds (in e.g. entye, gedet’ye) that Traviss added are more likely inspired directly by Harlin’s Mando’a or the same inspirations he used. Ghett comes from The Bounty Hunter Code by different authors—so actually the problem of murmured sounds is not attributable to Traviss.

You’ll have to judge for yourself whether this solution is plausible and satisfactory to you (and if it’s not, I’m always interested in hearing contradictory opinions even if it takes me a year to think through a reply). It’s satisfactory to me in its broad strokes, although I will have to think further on which sound changes make most sense in the light of the etymologies of the existing lexicon, which set of phonemes/pronunciations/spellings works best, etc (but that part got so long and rambly that I axed it until I have wrangled it into neater shape). But generally I feel pretty good about my chances of making something sensible out of these ingredients.

C, cy, yc—why are they pronounced like that?

I think I’ve mentioned before that the rule is very nearly regular, so here it is. I’ve reproduced Traviss’s original pronunciation guides here (so you can see whether what I’m saying holds true).

c (without y) is pronounced as /s/ before high front vowels /e i/

cerar [sair-ARR]

ceratir [sair-AH-teer]

ceryc [sair-EESH]

cetar [set-ARR]

cetare [set-ARE-ay]

cin [seen]

cinargaanar [see-NAHR-gah-nahr]

cinarin [see-NAH-reen]

cin'ciri [seen-SEE-ree]

cinyc [SEE-neesh]

ciryc [seer-EESH]

mircin [meer-SEEN]

mircir [meer-SEER]

mirci't [meer-SEET]

racin [ray-SEEN]

tom'urcir [tohm-OOR-seer]

ver'mircit [VAIR-meer-seet]

otherwise as /k/

That is, after other vowels:

ca [kah]

cabuor [kah-BOO- or]

cabur [KAH-boor]

ca'nara [KAH-nah-RAH]

can'gal [CAHN-gahl]

carud [kah-ROOD]

ca'tra[KAH-tra]

cuir [COO-eer]

copaanir [KOH-pan-EER]

copad [KOH-pad]

copikla [koh-PEEK-lah]

copyc [KOH-peesh]

cu'bikad [COO-bee-kahd]

cunak [COO-nahk]

cuun [koon]

cuyan [koo-YAHN]

cuyanir [coo-YAH-neer]

cuyete [coo-YAY-tay]

cuyir [KOO-yeer]

cuyla [COO-ee-lah]

du'car [DOO-kar]

du'caryc [doo-KAR-eesh]

ge'catra [geh-CAT-rah]

jorcu [JOR-koo]

ori'copaad [OH-ree-KOH-pahd]

vencuyanir [ven-COO-yah-neer]

vencuyot [vain-COO-ee-ot]

vercopa [vair-KOH-pa]

vercopaanir [VAIR-koh-PAH-neer]

…and in a word-final position:

balac [bah-LAHK]

bic [beek]

ibac [ee-BAK]

ibic [ee-BIK]

norac [noh-RAK]

tebec [TEH-bek]

yc is always pronounced as /iʃ/

aikiyc [ai-KEESH]

aruetyc [AH-roo-eh-TEESH]

balyc [BAH-leesh]

beskaryc [BES-kar-EESH]

burk'yc [BOOR-keesh]

chakaaryc [chah- KAR-eesh]

copyc [KOH-peesh]

dalyc [DAH-leesh]

daryc [DAR-eesh]

diryc [DEER-eesh]

duumyc [DOO-meesh]

etyc [ETT-eesh]

gaht'yc [GAH-teesh]

gehatyc [geh-HAHT-eesh]

haamyc [HAH-meesh]

haatyc [HAH-teesh]

haryc [HAR-eesh]

hayc [haysh]

hetikleyc [hay-TEEK-laysh]

hettyc [heh-TEESH]

hodayc [HOH-daysh]

hokan'yc [hoh-KAH-neesh]

iviin'yc [ee-VEEN-esh]

jagyc [JAH-geesh]

jaon'yc [jai-OHN-ish]

jari'eyc [JAR-ee-aysh

jatisyc [jah-TEE-seesh]

johayc [JO-haysh]

kotyc [koh-TEESH]

kyr'adyc [keer-AH-deesh]

kyrayc [keer-AYSH]

kyr'yc [KEER-eesh]

laamyc [LAH-meesh]

lararyc [lah-rah-eesh]

majyc [MAH-jeesh]

morut'yc [moh-ROO-teesh]

narseryc [nar-SAIR-eesh]

nayc [naysh]

neduumyc [nay-DOO-meesh]

nehutyc [neh-HOOT-eesh]

nu'amyc [noo-AHM-eesh]

nuhaatyc [noo-HAH-teesh]

ori'beskaryc [OH-ree-bes-KAR-eesh]

ori'jagyc [OH-ree-JAHG-eesh (or OH-ree-YAHG-eesh)]

ori'suumyc [OHR-ee-SOOM-eesh]

oyayc [oy-AYSH]

piryc [PEER-eesh]

ramikadyc [RAH-mee-KAHD-eesh]

ret'yc [RET-eesh]

ruusaanyc [roo-SAHN-eesh]

sapanyc [sah-PAHN-eesh]

shaap'yc [sha-PEESH]

shi'yayc [shee-YAYSH]

shuk'yc [shook-EESH]

shupur'yc [shoo-POOR-esh]

sol'yc [sohl-EESH]

talyc [tahl-EESH]

tomyc [TOH-meesh]

tranyc [TRAH-neesh]

tratyc [TRAH-teesh]

tug'yc [too-GEESH]

ulyc [OO-leesh]

urcir [oor-SEER]

utyc [OO-teesh]

verburyc [vair-BOOR-eesh]

verd'yc [VAIR-deesh]

vutyc [VOOT-eesh]

yaiyai'yc [yai-YAI-eesh]

Note that this is still true when yc occurs in the middle of a word instead of the end:

barycir [bah-REE-shir]

besbe'trayce [BES-beh-TRAYSH-ay]

dirycir [DEER-ee-SHEER]

ke'gyce [keh-GHEE-shay]

majyce [mah-jEE-shay]

majycir [MAH-jeesh-eer]

mar'eyce [mah-RAY-shay]

mureyca [MOOR-aysh-ah]

cy is pronounced as /ʃ/

burc'ya [BOOR-sha]

burcyan [BOOR-shahn]

cyare [SHAH-ray]

cyare'se [shar-AY-say]

cyar'ika [shar-EE-kah]

cyar'tomade [SHAR-toe-MAH-day]

mirshmure'cya [meersh-moor-AY-shah]

murcyur [MOOR-shoor]

oyacyir [oy-YAH-sheer]

Ret'urcye mhi [ray-TOOR-shay-MEE]

sheb'urcyin [sheh-BOOR-shin]

sho'cye [SHOW-shay]

tracy'uur [trah-SHOOR]

Exceptions

The above holds true except for some exceptions:

The first is a group of words with a combination of u + yc:

buyca [BOO-shah]

buy'ce [BOO-shay]

buycika [BOO-she-kah]

This might be related to the status of /ui/ as a diphthong in Mando’a & could be a piece of evidence against it. What do I mean? Well, every instance of ⟨uy⟩ in the dictionary, Traviss breaks up in two syllables /u.i/. Could be there’s no diphthong /ui/ in Mando’a? However, I think it’s more likely this is because Traviss gives the pronunciations with an English orthography (i.e. how an English speaking reader would know to pronounce the words), and there’s no diphthong /ui/ in English, so in order to represent those sounds in English, they have to be broken up in separate syllables.

I also think the long /u:/ in buy’ce etc. is likely simply an elision: try going slowly from /u/ to /i/ to /ʃ/, and you’ll notice it’s easier to slip directly from /u/ to /ʃ/. I would generalise it as the diphthong /ʊɪ/ being realised as /uː/ before palatal consonants (at least; maybe others as well).

and:

buyacir [boo-ya-SHEER] /bʊ.ja.ˈʃiɾ/

Which has no excuse for being irregular except for influence on its spelling from buy’ce, so you could alternatively spell it as buyacyir or pronounce it as /bʊ.ja.ˈsiɾ/ (either would be regular).

The other exception to the rule is:

acyk [AH-seek]

The rule for this could be formulated as “y is the only vowel in a syllable, it’s pronounced as /i/ and the pronunciation of c follows that.” Except for…

tracyn [trah-SHEEN]

Which itself could be analysed as a combination of the above rules: y as an only vowel gets pronounced as /i/, but the consonant in cy is still pronounced as /ʃ/ (in which case it would be acyk that is irregular instead).

It’s the derivations that appear irregular:

tracinya [trah-SHEE-nah]

tracyaat [tra-SHEE-at]

tra'cyar [tra-SHEE-ar]

Tracinya is plainly a derivation of tracyn, just spelled with an i instead of y. Interestingly, in Harlin’s Mando’a tracyn is pronounced as /tra.ʃin/ and tracinya as /tra.sin.ja/. So perhaps it’s acyk which should be pronounced as /a.ʃik/?

I’ve chosen to adjust the pronunciation of the other two to conform to the rule of pronouncing cy as /ʃ/: /tɾa.ˈʃaːt/ & /tɾa.ˈʃaɾ/.

And then:

yacur [YAH-soor]

Idek? I have do idea where this one comes from.

And:

Coruscanta [KOH-roo-SAHN-ta]

which is a loanword and doesn’t count. Although I’d suspect that “Corusanta” might be a fairly common misspelling among native speakers.

Explanation

So why is it pronounced like that? The explanation is something called palatalisation, which is the same reason why c in Latinate words is sometimes pronounced as /k/ and sometimes as /s/.

In very simple terms, the high front vowels and the semivowel /j/ are pronounced such that the tongue is at or very nearly the palatal position. So they tend to pull the preceding consonants to the palatal place of articulation (instead of whichever place of articulation they used to be pronounced at).

So in Mando’a:

c → k

c + high front vowel /i e/ → /s/

c + semivowel /y/ → /ʃ/

Not sure if /k/ is the original value of ⟨c⟩ since this rule doesn’t seem to apply to ⟨k⟩. Maybe ⟨c⟩ had originally another value, which has later changed into /k/?

There will be a second part to this post later, but I’ll break this off here for now.

#mando’a#mandoa#mando'a#mando’a language#mando’a phonology#mando’a orthography#ranah talks mando’a#conlanging#deconstructing someone else’s poorly documented conlang anyway

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went back to my notes, and actually I didn’t remember this one quite accurately.

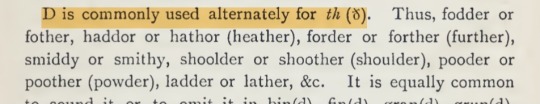

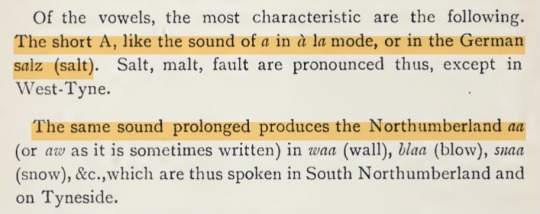

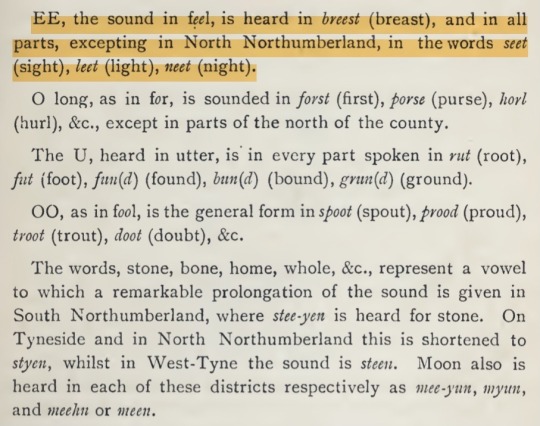

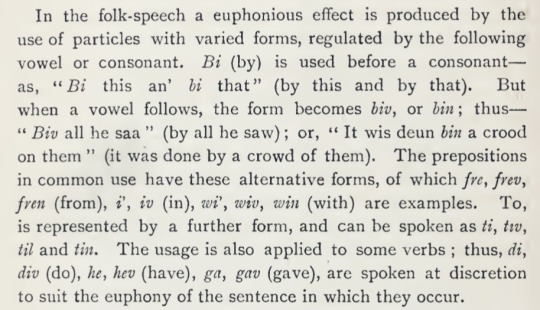

Apparently my first idea for long/short vowels had been to raise the short vowels, like Māori does. But that didn’t really work with the given pronunciations, so I flipped them, raising the long vowels instead. Which is indeed the system used by Swedish (which I’ve been reading lately, so that’s probably where the brain fart came from)—but also by some English dialects, incidentally including dialects in the Northumberland area. And that made a something click in my brain, as I had recently reposted this post about Geordie or Tyneside English inspiration in Mando’a. (And please point out any mistakes in the following, as I’m certainly no expert on English dialects!)

So I went and looked up dialects in this area. And here’s what I found (all emphases mine):

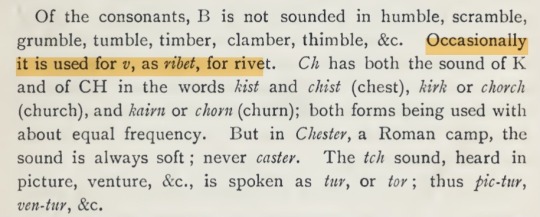

Consonants

In Heslop (1892 — yes, this is very old, but it’s a much more comprehensive and better written than a random list of dialect words off of the internet):

Karen Traviss (2006):

"V" and "w" are also sometimes interchangeable, as are "b" and "v"-another regional variation.

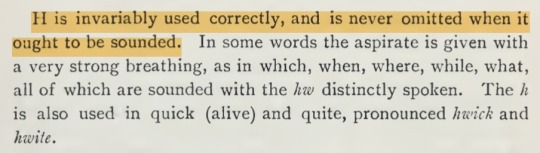

Traviss (2006);

“The initial "h" in a word is usually aspirated, except in its archaic form in some songs and poems, and "h" is always pronounced when it occurs in the middle of a word.”

Traviss (2006):

“Occasionally, the pronunciation of "t"s and "d"s are swapped. "T" is the modern form; "d" is archaic.”

I don’t think this one appears in TE, but th ~ d does (Heslop 1892):

And then we have also

“some regions do pronounce "p" almost as ph and "s" as z.”

and

“"J" is now pronounced as a hard "j" as in joy, but is still heard as "y" in some communities.”

I don’t know if those have any correspondences in TE. More data required.

Vowels

Heslop (1892):

Watt & Allen (2003):

Vowel length is phonemic for many speakers of TE, i.e. the distinction is one of duration.

Glottal stop

Watt & Allen (2003):

Traviss (2006):

“Sometimes an apostrophe separates the terminal vowel, to indicate the slight glottal stop of some Mandalorian accents. This apostrophe, known as a beten, or sigh-as in Mando'a-can also indicate breathing, pronunciation, or dropped letters.”

The Beten is both a phonetic and a spelling symbol. It is used to represent glottal stop, but also to form compound words and indicate contractions (as it is in English). Yes, it’s irregular, but so are natural languages. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Here’s Traviss’ (2005) take:

“The beten is almost optional, except in some words where it's really obvious you need it for ease of pronunciation. I know that's a bit odd but every language needs an idiosyncrasy, sand that struck me as one that would evolve naturally; folk would "spell" words wrong, seeing as it's mainly an oral tradition, but Mando'ade are pretty chilled about it. They always look at the bigger picture. Very pragmatic.”

Phonologically conditioned variation in particles:

Heslop (1892):

Compare with Mando’a suffixes ge’/get’, n’/ne’/nu’, k’/ke’, and others.

Tldr:

Now I need to go back to the dictionary and see if this works, but I suspect it will. And if I’m correct, Mando’a phonology is also inspired by its author’s native dialect, and the inconsistencies between the spellings and pronunciations in the original dictionary can be explained by a) the inherent difficulty of rendering one languages phonology into the orthography of another (which is why we use IPA! goddammit), and b) the differences in the pronunciation between standard English (which were probably thinking of when looking at those pronunciation directions) and the authors native dialect (which they may have been thinking of).

P.s. This would also work with my newest pet theory that Modern Mando’a is a creole language: it would explain these phonological effects as substrata effects. Because way back when the Taung were conquering the galaxy and conscripting humans and other species into their armies, some of those conscripts certainly spoke Galactic Basic, but they wouldn’t have spoken the Core dialects (represented by RP in GFFA), would they? They would’ve spoken Outer Rim Basic dialects.

References:

Heslop, Oliver (1892), “Northumberland Words”. The English Dialect Society, London. https://archive.org/details/northumberlandv128hesluoft

Traviss, Karen (2005), in “Mando’a discussion”, Starwars.com message boards. https://web.archive.org/web/20070809091250/http://forums.starwars.com/thread.jspa?threadID=237751&start=0

Traviss, Karen (2006), “The Mandalorians: People and Culture”, Star Wars Insider, 86. (The relevant part for example here)

Traviss, Karen, “Mando’a ”, karentraviss.com. https://web.archive.org/web/20110925083955/http://www.karentraviss.com/page20/page26/index.html (archived in 2011)

Watt, Dominic; Allen, William (2003), "Tyneside English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (2): 267–271, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001397

(Would’ve loved to find more sources for this, but I’m at home and don’t have access to university library atm. So.)

Kaa's Grudge-Match With Mando'a Pronunciation

KT is no Tolkien, okay. She did a decent job with the language and worldbuilding, for which I thank her from the bottom of my heart, but her pronunciations are, to put it delicately, irregular. I’m willing to tolerate some of it - but certainly not all of it.

Keep reading

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s an idea I’ve been bouncing around for a while. And mind you, I haven’t made any sort of a systemic analysis to figure out if this would work or make sense, so right now it’s just an idea that I’m floating.

What if:

Mando’a vowels change slightly when they are doubled/lengthened. Not enough to make them entirely separate phonemes, but noticeably so that the short vowels are more central/relaxed and the long vowels are slightly “exaggerated” in comparison.

Short i is relaxed /ɪ/, like in English “kit

Long ii is slightly higher, tighter /iː/, like in English “fleece”

Short e is relaxed /ɛ/, like in English “bed”

Long ee is slightly higher /eː/, like in Australian English “bed”—look, English e’s don’t vary very systematically so it’s hard to do this “like English thing”

Short a is central /ɐ/, like in English “nut” or /ʌ/ like English “strut”

Long aa is back /ɑː/, like in English “father”

Short u is /ʊ/, like in English “foot”

Long u is /uː/, like in English “goose”

Short o is /ɔ/

Long oo is ever so slightly higher, not quite u but half a step in that direction, /oː/

Some speakers, especially of Kalevalan/Sundari dialects which have been influenced by Galactic Basic, pronounce unstressed short vowels even more centrally, as /ə/

Tl;dr: the front vowels get fronter, back vowels backer, everything gets slightly raised. But native speakers still perceive them as the same sounds. This system is btw very much inspired by Swedish phonology (but has a smaller number of vowels), if anyone is wondering. Go to the Wikipedia Swedish Phonology page, and you can listen to examples.

So when a Basic-speaking non-linguist comes to Mandalore, they genuinely might think ee sounds like /iː/ and oo sounds like /uː/—or think that their Basic-speaking audiences would get the sounds correct if they represented them like that with English orthography. I had a hard time figuring out which English words even would reliably produce the those sounds. Because the problem is that you can only represent English phonology with English orthography—how would you represent sounds that are not in English with English spelling? You don’t. That’s why we use IPA, not whatever the hell it is that canon Mando’a dictionary uses.

Kaa's Grudge-Match With Mando'a Pronunciation

KT is no Tolkien, okay. She did a decent job with the language and worldbuilding, for which I thank her from the bottom of my heart, but her pronunciations are, to put it delicately, irregular. I’m willing to tolerate some of it - but certainly not all of it.

Keep reading

#mando’a#mandoa#mando’a language#retcon#mando’a retcon#mando’a phonology#mando’a linguistics#ranah talks mando’a

123 notes

·

View notes