#deconstructing someone else’s poorly documented conlang anyway

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

More palatalisations & how they could explain the problem of murmured sounds

Okay, so: Mando’a has these spellings ⟨dh⟩ (dha), ⟨gh⟩ (ghett), and ⟨mh⟩ (mhi) where the h seems to suggest aspiration. But the problem is that that is a very weird set of consonants to be aspirated: I know of no language that would only contrast between aspirated and unaspirated voiced stops and not make the same contrast for unvoiced stops as well. (Except for the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European, but there as well this exact issue is a problem that has bugged linguists forever.)

But then, while I was formulating my palatalisation theories, I found out that ⟨mh vh bh nh lh⟩ are spellings that actually have been used by natural languages to spell /mj vj bj nj lj/. And you know what? That spelling makes perfect sense: palatalised voiced stops don’t sound exactly like murmured (i.e. aspirated voiced) sounds… but they also don’t sound exactly unlike them. There’s a bit of a puff of air, more than with the unvoiced consonants. And this could explain why Mando’a has dh but not th, and ty but not dy.

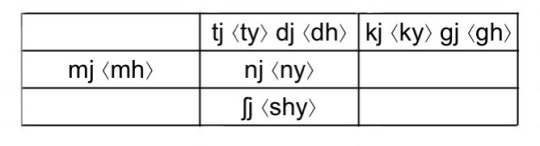

So we have a bit of a mismatched set of spellings:

… but as you see, together they make a complimentary set.

(Okay, this set is a bit incomplete; I’ll have to leave the task of completing it to a later post because it got very long and very rambling.)

So how are dh, gh, mh pronounced then?

On the Republic Commando soundtrack, mhi is pronounced as /mi/ and dha as /da/. On Traviss’s recordings, neither word makes an appearance so we don’t know how she would pronounce them. Her pronunciation guide gives:

dha[dah]

mhi[mee]

It appears that the extra h does not affect pronunciation.

In Romance languages for example, /gj/ became /j/ or /dʒ/ (so that would be ⟨y⟩ or ⟨j⟩ in Mando’a orthography), and /dj/ became /dz/ or /j/. But maybe in Mando’a they did something else: instead of strengthening, they became weaker, first becoming aspirated, and then losing the aspiration too:

/dʲ/ > /dʰ/ > /d/

/ɡʲ/ > /ɡʰ > /g/

/mʲ/ > /mʰ/ > /m/

A range of these gradations might exist along the different dialects. Perhaps the spelling ⟨dh gh mh⟩ became standardised at a time when that was the prevailing pronunciation among whichever dialect was the most prestigious one at the time.

Conclusion

So there you have it: my best damn attempt to make the weirdness of Mando’a orthography make sense.

I can’t know whether this is what the original authors (Jesse Harlin and Karen Traviss) intended. But as always, my primary goal is to make sense of the corpus of Mando’a that exists in a way that is linguistically plausible. Authorial intent is secondary to me, although I do use that as guidance whenever there is an interview or some source to guide me and I can make it fit & make sense.

Out of Harlin’s inspirations, Russian, Hungarian and Romanian exhibit at least some palatalisation, so the words that were already present in the Repcomm soundtrack (e.g. dha, mhi, tracinya, dralshy’a) could have gotten their sounds from there. Neither of the additional inspirational languages (Romani and Nepali) Traviss has mentioned has palatalised consonants, but Nepali does have murmured ones. So the additional sounds (in e.g. entye, gedet’ye) that Traviss added are more likely inspired directly by Harlin’s Mando’a or the same inspirations he used. Ghett comes from The Bounty Hunter Code by different authors—so actually the problem of murmured sounds is not attributable to Traviss.

You’ll have to judge for yourself whether this solution is plausible and satisfactory to you (and if it’s not, I’m always interested in hearing contradictory opinions even if it takes me a year to think through a reply). It’s satisfactory to me in its broad strokes, although I will have to think further on which sound changes make most sense in the light of the etymologies of the existing lexicon, which set of phonemes/pronunciations/spellings works best, etc (but that part got so long and rambly that I axed it until I have wrangled it into neater shape). But generally I feel pretty good about my chances of making something sensible out of these ingredients.

C, cy, yc—why are they pronounced like that?

I think I’ve mentioned before that the rule is very nearly regular, so here it is. I’ve reproduced Traviss’s original pronunciation guides here (so you can see whether what I’m saying holds true).

c (without y) is pronounced as /s/ before high front vowels /e i/

cerar [sair-ARR]

ceratir [sair-AH-teer]

ceryc [sair-EESH]

cetar [set-ARR]

cetare [set-ARE-ay]

cin [seen]

cinargaanar [see-NAHR-gah-nahr]

cinarin [see-NAH-reen]

cin'ciri [seen-SEE-ree]

cinyc [SEE-neesh]

ciryc [seer-EESH]

mircin [meer-SEEN]

mircir [meer-SEER]

mirci't [meer-SEET]

racin [ray-SEEN]

tom'urcir [tohm-OOR-seer]

ver'mircit [VAIR-meer-seet]

otherwise as /k/

That is, after other vowels:

ca [kah]

cabuor [kah-BOO- or]

cabur [KAH-boor]

ca'nara [KAH-nah-RAH]

can'gal [CAHN-gahl]

carud [kah-ROOD]

ca'tra[KAH-tra]

cuir [COO-eer]

copaanir [KOH-pan-EER]

copad [KOH-pad]

copikla [koh-PEEK-lah]

copyc [KOH-peesh]

cu'bikad [COO-bee-kahd]

cunak [COO-nahk]

cuun [koon]

cuyan [koo-YAHN]

cuyanir [coo-YAH-neer]

cuyete [coo-YAY-tay]

cuyir [KOO-yeer]

cuyla [COO-ee-lah]

du'car [DOO-kar]

du'caryc [doo-KAR-eesh]

ge'catra [geh-CAT-rah]

jorcu [JOR-koo]

ori'copaad [OH-ree-KOH-pahd]

vencuyanir [ven-COO-yah-neer]

vencuyot [vain-COO-ee-ot]

vercopa [vair-KOH-pa]

vercopaanir [VAIR-koh-PAH-neer]

…and in a word-final position:

balac [bah-LAHK]

bic [beek]

ibac [ee-BAK]

ibic [ee-BIK]

norac [noh-RAK]

tebec [TEH-bek]

yc is always pronounced as /iʃ/

aikiyc [ai-KEESH]

aruetyc [AH-roo-eh-TEESH]

balyc [BAH-leesh]

beskaryc [BES-kar-EESH]

burk'yc [BOOR-keesh]

chakaaryc [chah- KAR-eesh]

copyc [KOH-peesh]

dalyc [DAH-leesh]

daryc [DAR-eesh]

diryc [DEER-eesh]

duumyc [DOO-meesh]

etyc [ETT-eesh]

gaht'yc [GAH-teesh]

gehatyc [geh-HAHT-eesh]

haamyc [HAH-meesh]

haatyc [HAH-teesh]

haryc [HAR-eesh]

hayc [haysh]

hetikleyc [hay-TEEK-laysh]

hettyc [heh-TEESH]

hodayc [HOH-daysh]

hokan'yc [hoh-KAH-neesh]

iviin'yc [ee-VEEN-esh]

jagyc [JAH-geesh]

jaon'yc [jai-OHN-ish]

jari'eyc [JAR-ee-aysh

jatisyc [jah-TEE-seesh]

johayc [JO-haysh]

kotyc [koh-TEESH]

kyr'adyc [keer-AH-deesh]

kyrayc [keer-AYSH]

kyr'yc [KEER-eesh]

laamyc [LAH-meesh]

lararyc [lah-rah-eesh]

majyc [MAH-jeesh]

morut'yc [moh-ROO-teesh]

narseryc [nar-SAIR-eesh]

nayc [naysh]

neduumyc [nay-DOO-meesh]

nehutyc [neh-HOOT-eesh]

nu'amyc [noo-AHM-eesh]

nuhaatyc [noo-HAH-teesh]

ori'beskaryc [OH-ree-bes-KAR-eesh]

ori'jagyc [OH-ree-JAHG-eesh (or OH-ree-YAHG-eesh)]

ori'suumyc [OHR-ee-SOOM-eesh]

oyayc [oy-AYSH]

piryc [PEER-eesh]

ramikadyc [RAH-mee-KAHD-eesh]

ret'yc [RET-eesh]

ruusaanyc [roo-SAHN-eesh]

sapanyc [sah-PAHN-eesh]

shaap'yc [sha-PEESH]

shi'yayc [shee-YAYSH]

shuk'yc [shook-EESH]

shupur'yc [shoo-POOR-esh]

sol'yc [sohl-EESH]

talyc [tahl-EESH]

tomyc [TOH-meesh]

tranyc [TRAH-neesh]

tratyc [TRAH-teesh]

tug'yc [too-GEESH]

ulyc [OO-leesh]

urcir [oor-SEER]

utyc [OO-teesh]

verburyc [vair-BOOR-eesh]

verd'yc [VAIR-deesh]

vutyc [VOOT-eesh]

yaiyai'yc [yai-YAI-eesh]

Note that this is still true when yc occurs in the middle of a word instead of the end:

barycir [bah-REE-shir]

besbe'trayce [BES-beh-TRAYSH-ay]

dirycir [DEER-ee-SHEER]

ke'gyce [keh-GHEE-shay]

majyce [mah-jEE-shay]

majycir [MAH-jeesh-eer]

mar'eyce [mah-RAY-shay]

mureyca [MOOR-aysh-ah]

cy is pronounced as /ʃ/

burc'ya [BOOR-sha]

burcyan [BOOR-shahn]

cyare [SHAH-ray]

cyare'se [shar-AY-say]

cyar'ika [shar-EE-kah]

cyar'tomade [SHAR-toe-MAH-day]

mirshmure'cya [meersh-moor-AY-shah]

murcyur [MOOR-shoor]

oyacyir [oy-YAH-sheer]

Ret'urcye mhi [ray-TOOR-shay-MEE]

sheb'urcyin [sheh-BOOR-shin]

sho'cye [SHOW-shay]

tracy'uur [trah-SHOOR]

Exceptions

The above holds true except for some exceptions:

The first is a group of words with a combination of u + yc:

buyca [BOO-shah]

buy'ce [BOO-shay]

buycika [BOO-she-kah]

This might be related to the status of /ui/ as a diphthong in Mando’a & could be a piece of evidence against it. What do I mean? Well, every instance of ⟨uy⟩ in the dictionary, Traviss breaks up in two syllables /u.i/. Could be there’s no diphthong /ui/ in Mando’a? However, I think it’s more likely this is because Traviss gives the pronunciations with an English orthography (i.e. how an English speaking reader would know to pronounce the words), and there’s no diphthong /ui/ in English, so in order to represent those sounds in English, they have to be broken up in separate syllables.

I also think the long /u:/ in buy’ce etc. is likely simply an elision: try going slowly from /u/ to /i/ to /ʃ/, and you’ll notice it’s easier to slip directly from /u/ to /ʃ/. I would generalise it as the diphthong /ʊɪ/ being realised as /uː/ before palatal consonants (at least; maybe others as well).

and:

buyacir [boo-ya-SHEER] /bʊ.ja.ˈʃiɾ/

Which has no excuse for being irregular except for influence on its spelling from buy’ce, so you could alternatively spell it as buyacyir or pronounce it as /bʊ.ja.ˈsiɾ/ (either would be regular).

The other exception to the rule is:

acyk [AH-seek]

The rule for this could be formulated as “y is the only vowel in a syllable, it’s pronounced as /i/ and the pronunciation of c follows that.” Except for…

tracyn [trah-SHEEN]

Which itself could be analysed as a combination of the above rules: y as an only vowel gets pronounced as /i/, but the consonant in cy is still pronounced as /ʃ/ (in which case it would be acyk that is irregular instead).

It’s the derivations that appear irregular:

tracinya [trah-SHEE-nah]

tracyaat [tra-SHEE-at]

tra'cyar [tra-SHEE-ar]

Tracinya is plainly a derivation of tracyn, just spelled with an i instead of y. Interestingly, in Harlin’s Mando’a tracyn is pronounced as /tra.ʃin/ and tracinya as /tra.sin.ja/. So perhaps it’s acyk which should be pronounced as /a.ʃik/?

I’ve chosen to adjust the pronunciation of the other two to conform to the rule of pronouncing cy as /ʃ/: /tɾa.ˈʃaːt/ & /tɾa.ˈʃaɾ/.

And then:

yacur [YAH-soor]

Idek? I have do idea where this one comes from.

And:

Coruscanta [KOH-roo-SAHN-ta]

which is a loanword and doesn’t count. Although I’d suspect that “Corusanta” might be a fairly common misspelling among native speakers.

Explanation

So why is it pronounced like that? The explanation is something called palatalisation, which is the same reason why c in Latinate words is sometimes pronounced as /k/ and sometimes as /s/.

In very simple terms, the high front vowels and the semivowel /j/ are pronounced such that the tongue is at or very nearly the palatal position. So they tend to pull the preceding consonants to the palatal place of articulation (instead of whichever place of articulation they used to be pronounced at).

So in Mando’a:

c → k

c + high front vowel /i e/ → /s/

c + semivowel /y/ → /ʃ/

Not sure if /k/ is the original value of ⟨c⟩ since this rule doesn’t seem to apply to ⟨k⟩. Maybe ⟨c⟩ had originally another value, which has later changed into /k/?

There will be a second part to this post later, but I’ll break this off here for now.

#mando’a#mandoa#mando'a#mando’a language#mando’a phonology#mando’a orthography#ranah talks mando’a#conlanging#deconstructing someone else’s poorly documented conlang anyway

158 notes

·

View notes