#lugnasad

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yue is a Virgo; Yukito is the Capricorn

I spend a lot of brain energy on incorporating zodiac and symbolic detail into my headcanons. Discovering Saint Seiya only made my problem worse.

For years I've held the headcanon that Yue was created on the winter solstice. It's canon that he and Yukito have different birthdays, but we only know for sure that Yukito's birthday is Christmas, December 25.

Does he have a Capricorn personality? I can believe him as an earth element.

But Yue, earth? Earthy is under Kero's jurisdiction and is one of the Cards that unseals the lion's powers. However, none of the water or air signs' personality traits in the Western zodiac match Yue at all. Clow's magic blends East and West, so I think it is important to look at temperaments and associated elements, as well as relative celestial movement through the year and cultural significance of times of year.

Left with earth signs to choose from, I believe Yue is a Virgo, not a Capricorn. Compare Yue to Virgo Shaka from Saint Seiya: powerful, beautiful, proud, dangerous, and certain of himself (at first). Virgos are exacting amd picky. They are -- I say this as an Aries -- the most difficult of people to bear. (But like Aries Mu loves Shaka, I love Yue with all my enduring love.)

Further, there is a significant moon festival during the Virgo date range. This year 2024, we have a super moon (and a partial lunar eclipse) on September 17. To me it's very believable that Yue could have been created during the autumn moon festival during a similar lunar eclipse.

During a rabbit (Eastern zodiac) year, of course!

Similarly, Kerberos was created, not at summer solstice, but at Lughnasadh, which makes him a Leo and a fire sign. That one seems pretty obvious! (He would have to be born 1 or 13 lunar years before Yue to make him a Tiger year. Ideally, he was born 25 years before Yue, making Kero a Fire Tiger Leo and Yue a Water Rabbit Virgo.)

#cardcaptorsakura#yue#zodiac signs#kerberos#saint seiya#clow reed#supermoon#lugnasad#moon festival#Magic headcanons

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

vote yes if you have finished the entire book.

vote no if you have not finished the entire book.

(faq · submit a book)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celtic seasonal festivals - Part 3: Lughnasadh

Part 1 ; Part 2 ; Part 4

Hello everyone! It's August 1st, which means it's once again time for another issue of our series on Celtic seasonal festivals. Today, we will take a look at the origins, rituals, and surviving customs of Lughnasadh - one of the less known, but no less significant festivals.

General/Etymology

Lughnasadh, pronounced loo-NAH-sah (alternatively called Lughnasa/Lúnasa), is one of the Celtic seasonal/"fire" festivals that marked the beginning of the harvest season, traditionally being held on August 1st. (Although due to the lunar calendar of the Celts, the date might have been movable.) It took place when the first fruits of the year were ready for harvest, celebrating and thanking the earth for the bounty it had given to mankind.

Back in ancient times, the last days of July were trying time for farmers, since the crops from the previous year were already done and the new ones not yet ripe. Thus, it would make sense for the advent of the harvesting period to be considered an appropriate time for celebrations of joy and thanksgiving. This suggests a great focus on arable farming in Celtic culture, which is supported by historical evidence: In fact, the Celts were the first people to significantly change Europe's landscape from the Atlantic coast all the way to the Black Sea, turning primeval forests into a cultivated landscape of fields, farmsteads, and settlements. This was in no small part due to their ability to process iron, which was used for a multitude of agricultural tools such as axes, scythes, and sickles, allowing them to work the land with ease.

The main crops cultivated by the Ancient Celts were emmer (depicted above), spelt, einkorn wheat, millet, and barley; aside from food, the latter was also used for the production of beer (Source)

However, the most ingenious, revolutionary invention of the Celtic farmers was the iron plowshare: Celtic plows were the first ones to have a mobile coulter, with a sharp knife making a vertical cut while the share simultaneously did a horizontal cut, turning over the soil. This meant that the Celts didn't have to plow their fields twice, like other ancient peoples who still used wooden plows. Thanks to this and various other inventions - like sealable underground pits to keep the corn fresh and a kind of manure made from dung and chalk/loam - the Celts were able to achieve more successes in agriculture than any other people of the Iron Age. Not even the Roman plows of this period, which could only carve furrows into the soil, were comparable to those of the Celts.

It has been suggested that the Gaulish Celts referred to Lughnasadh as Aedrinia, derived from the name of the month Edrinios (possibly meaning "end of the heat", with heat being synonymous to aéd/fire) found in the Coligny Calendar. An alternate, older Irish term for the festival was Brón Trogain, which can be translated as "Earth's sorrow" (brón meaning sorrow/lamentation/burden, and trogain earth/autumn). Since the word trogan is also associated with the pain during childbirth in an Irish imprecation, the name can be seen as a metaphor for the grain "dying" to "give life to the people". On the other hand, trogain might also be translated as "(female) raven", which is known to be the companion animal of the god Lugh. In Irish mythology, Lugh is the god of justice, kingship, the art of war, and master craftsmanship, as well as the namesake of Lughnasadh. The Old Irish name for the festival, Lugnasad, is a combination of Lug - a variant spelling of Lugh - and the word násad, meaning "festival" or "assembly". Thus, Lughnasadh can be translated as "feast of Lugh"/"Lugh's feast". However, as we will soon see, a large part of the festivities were actually not in honor of Lugh, but his mother, Tailtiu.

Ancient Customs and Rites

Supposedly, Lughnasadh was introduced by Lugh as a funeral celebration for his mother Tailtiu. According to Irish lore, Tailtiu was the wife of Eochaid mac Eirc, the last High King of the Fir Bolg to rule over Ireland. However, upon the invasion of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Fir Bolg were defeated and expelled from their homeland, with King Eochaid mac Eirc being among the casualties. However, Tailtiu survived the death of her husband and the Tuatha Dé Dananns' ascension to power, living on to become the foster mother of Lugh, the illegitimate son of the hero Cian and Ethniu, daughter of the demonic Fomorian leader Balor. Being a kind and hardworking soul, Tailtiu worked tirelessly to improve the living conditions of the people, cutting down forests and clearing the plains of Ireland so they could be used for agriculture. Eventually, however, her endeavors took their toll, and on August 1st, she passed away from exhaustion at Teltown. To commemorate her kindness and everything she had done for the Irish people, Lugh decided to declare the first of August as the time of the yearly mourning festivities for Tailtiu, his foster mother whom he loved so dearly.

From this, we can make various conclusions regarding the symbolic meaning of these myths: Scholars have proposed that Tailtiu may have originally been an Irish earth goddess, being the embodiment of dying vegetation/weed that serves to feed mankind. Furthermore, as Irish folklorist Máire MacNeill observed in her studies, the struggle for a goddess is also a theme present in various rituals of Lughnasadh: Usually, there is a conflict between two gods - one of them being identified as Lugh, while the other is believed to be a figure named Crom Cruach/Crom Dubh - who sometimes fight over a woman called Eithne, who has been theorized to be an ancient earth goddess representing the grain. The roles of the gods may also hint at their original function: In the folkloric context, Crom Cruach is the one to guard the grain as his treasure, not willing to give it up to Lugh who aims to seize it for mankind. This might be a remnant of Crom Cruach's original status as a chthonic deity, since gods and goddesses of the underworld were also thought to be responsible for fertility and growth in ancient times. There are also various surviving legends that associate Crom with a bull, intend on using the animal to sow discord and wreak havoc (sometimes, he turns into a bull himself to battle his adversary). However, they always end in Crom's defeat, with the bull often being sacrificed, consumed, and finally resurrected, which may be related to ancient practices of bull sacrifice. (There are various standing stones called "bull stones" in Ireland which are identified with Crom Cruach, and since human and cattle bones were found in stone circles such as the one at Grange, it is suspected that these places were ancient sacrificial sites.) Lastly, Lugh is also credited Lugh with triumphing over the personification of blight, which can be traced back to the myth of him killing his demonic grandfather Balor. Said to possess a single giant, havoc-wreaking eye, Balor is believed to represent the scorching summer sun as well as drought and blight, being defeated in battle by Lugh who blinds him with a slingshot.

Tailtiu by Wendy Andrew (left) and her foster son Lugh by Ire (right); Tailtiu is depicted with typical symbols of harvest (cornucopia, cow horns) as well as the image of a snake on her dress, an animal associated with healing in Celtic mythology; Lugh shares various characteristics with both the Greek Mercury and the Norse Odin, which can be seen in the attributes he is depicted with (winged sandals/winged helmet for Mercury; spear and raven for Odin)

Although we will most likely never know for sure what the ancient festival looked like, we can reconstruct its rituals from surviving customs and accounts from Irish literature. In a 15th-century version of Tochmarc Emire, one of the earliest mentions of the festival, Lughnasadh is said to commemorate the god Lugh's wedding feast, while in other texts, the origin is either attributed to the mourning of Lugh's wife Nás and her sister Buí, or the funeral games Lugh held in honor of Tailtiu. These games were known as Óenach Tailten (or Áenach Tailten) and were organized each year at Teltown in the Kingdom of Meath. It's estimated they lasted for about two weeks, and like all other customs associated with Celtic seasonal festivals, the ceremonies most likely began on the eve of August 1st. Fitting for an obsequy, it started off with a ceremony to honor the people who had passed during the year, which could take from one to three days. The guests would chant funeral songs known as Guba, followed up by the druids' Cepógs, improvised songs in memory of the dead. As a final act, the deceased would be burned on a gigantic funeral pyre. Afterwards, a universal truce would be declared by the Ollamh Érenn, the chief of bards and poets in Ireland who held a status comparable to that of a High King. Medieval sources confirm that all kings attending the óenach would agree to a ceasefire for the duration of the festival, and any violation of it was considered highly disgraceful. In addition, the occasion was also used as an opportunity to proclaim laws, settle legal disputes, and drawing up new contracts, which was achieved with the help of bards and druids acting as mediators between the rulers and the common people. Once the negotiations were over, yet another massive fire was ignited, signaling that the joyous celebrations following the funeral rites were about to begin: the Tailteann Games.

The nature of these games was very similar to that of the Ancient Olympic Games, featuring a variety of contests in disciplines such as running, hurling, high and long jumping, archery, spear throwing, as well as martial arts competitions in swordfighting, wrestling, and boxing. Swimming contests were held in artificial lakes specifically constructed for this purpose at Teltown, and horse and chariot races were extremely popular among the people (a structure strongly resembling Greek and Roman horse racetracks has also been found near the Heuneburg, a Celtic dig site in Germany dating back to the 6th century BC; this would make it the oldest preserved hippodrome in the world, as well as suggest a high significance of horse racing in Celtic culture). However, the games were not limited to shows of physical prowess: There were contests where participants had to prove their skill in singing, dancing, storytelling and Fidchell (a type of strategic board game), along with competitions to determine the greatest master goldsmiths, jewelers, weavers, and armorers. Aside from enjoying these various entertainments, many guests would also bring goods to exchange and trade them with other people. However, the character of these festivities was not really commercial - rather, the Óenach Tailten were a purely social event, meant to show off the manifold talents of their attendants as well as celebrate community and strengthen social bonds.

Due to this, the gathering was also believed to be an excellent time for matchmaking. We know that in Ireland, Scotland, and the Orkney Isles, trial marriages were a very typical Lughnasadh custom, which would be conducted by a young couple joining hands through a hole in a wooden door (this ritual known as "handfastening" has also become associated with Beltane in modern paganism, although there is no historic basis for this). These trial marriages lasted a year and a day, during which the youths were able to decide whether they wanted to spend their lives together. If the pair did happen to like each other, the marriage would be made formal after the period of time had expired - if not, the engagement would simply be annulled without consequences, and any children that resulted from the union would still be counted among the father's legal heirs.

Meanwhile, in Kildare, people celebrated the Óenach Carmain instead, which was held in honor of the goddess Carman (or Carmun). Scholars believe she may have once been a goddess similar to Tailtiu, although Irish mythology depicts her not as a native of Ireland, but as an invader who came from Athens during the times of the Tuatha Dé Danann. (It's interesting to note that her land of origin is specifically stated as Greece, especially since the Panathenaic Games in Athens share some similarities with the Celtic óenach; this gives room for the consideration that she might have been an import goddess who was villainized later on.) The Óenach Carmain seems to have been a little more focused on agriculture and commerce, featuring markets for food, livestock, and foreign trade.

Aside from the glorious óenach in the cities, it can be surmised there were also some more rural Lughnasadh traditions, varying depending on the locality. We have accounts that cattle was blessed on the eve of Lughnasadh, and that charms would be made for both the livestock and milking equipment which were supposed to last a year. (This is very similar to certain Beltane customs, which were also meant to bring good luck and ensure a plentiful supply of milk throughout the year.) Cows would be milked in the morning, with the milk being collected to be later drunk during a feast. In addition, people would go out to gather bilberries which were also an important part of the festive buffet, and if there were lots of bilberries, it was said that the harvest would be plentiful as well. Special dishes that represented the harvest would be prepared, such as porridge and bread, often including fresh seasonal fruits. In the Scottish Highlands, an oatcake called lunastain would be baked, which is believed to have its origins as a sacrificial offering. It was also tradition to bake a bread from the newly harvested grain, made with a baker's peel of rowan or another sacred type of wood. This bread would be served to the head of the household, who would eat it and then walk sunwise around the cooking fire while chanting a blessing prayer. Finally, everyone would have a communal meal of the freshly harvested foods.

Enjoying a loaf made from the first grain was one of the most common Lughnasadh traditions (Source)

However, there were also rituals that had a more religious, sacred aspect: On Lughnasadh, a variety of ritual dance plays would be re-enacted, usually centering around the god Lugh and his heroic deeds. For example, one play told about Lugh's and Crom Cruach's battle for Eithne, while another revolved around Lugh imprisoning the monster of blight and famine, saving the harvest and seizing it for mankind. In addition, a large, carved stone head was often placed on top of a hill, most likely representing Crom Cruach, after which an actor playing Lugh would symbolically triumph over it.

The sacrifice of a sacred bull was also an integral part of the festivities, followed by people feasting on its flesh as well as some sort of ceremony involving its hide. (According to Irish lore, sleeping in the hide of a sacrificed bull was a common rite of divination among druids, particularly when it came to determining the successor to the title of High King.) Eventually, the ritual was concluded by the bull's symbolic replacement with a younger one, which was most likely meant to represent its resurrection. Since Lughnasadh was the time when the first corn would be cut, there was also an offering of the First Fruits of the year, with the first sheaf of weed being brought to an elevated place where it was buried as a sacrifice to a deity (this indicates the deity was chthonic in nature, since the dwelling of chthonic gods was believed to be beneath the earth). Sometimes, people would also adorn themselves with flowers while ascending the hill, which would then be buried at the summit to signify that summer was ending.

In fact, many Lughnasadh customs took place on mountains or hills. Beginning after sunset, people would make pilgrimages to mounts such as Knocknadobar, Drung Hill, Mount Brandon, Slievecallan, Slieve Donard, Church Mountain, and Croagh Patrick (which was known as Cruachán Aigle back in the day). On many of these mountains, megalithic monuments and stone tombs, so-called cairns, were found, confirming that they have been of high cultural significance for a very long time (in close proximity to Croagh Patrick, archaeologists even discovered remains of a Bronze Age hillfort, dating back to the 8th century BC). People probably came to these remote places to remember their ancestors, and it can be assumed that spiritual ceremonies were performed at the old graves. Also, many hills had a holy well located on top of them, and just like on Imbolc and Beltane, visiting holy wells (colloquially called "clootie wells") was a very common custom on Lughnasadh. Visitors would pray for health while walking sunwise around the well, typically leaving an offering in the form of coins and "clooties" - small pieces of cloth or fabric that would be dipped in the well water and then hung on a nearby tree. Furthermore, the wells were often decorated with flowers to add to the solemn atmosphere.

However, the hilltop gatherings also had a more secular side: In many ways, they were like a smaller version of the óenach, with sporting competitions in weight-throwing, hurling, and horse racing. The tradition of a mock faction fight has also been recorded, involving two groups of young men who would have a contest in bataireacht, a type of Irish martial art that included fighting with sticks called shillelagh. From Scotland, we know of a competition between groups of youths who each built a tower of sods with a flag on top, trying to sabotage the towers of their rivals for a number of days before finally meeting "in battle" at Lughnasadh. Aside from this, various other games were also played at the gatherings, and there was a general merry atmosphere. People would feast, drink, tell stories and dance to folk music, with the typical matchmaking customs also being present. Some of these open-air gatherings also featured bonfires, although they were pretty rare and held less significance than those of Beltane. The celebrations and festivities lasted three days in total, usually being overseen by a chosen representative of the god Lugh. Once the festival came to a close, there would be a ceremony to indicate that the interregnum was over, and the chief god back in his rightful place.

Finally, same as with the other seasonal festivals, there were certain superstitions associated with Lughnasadh, particularly in regard to the weather. The beginning of August was seen as a good time for weather divination, and predictions seem to have been based on atmospheric conditions at Lughnasadh. For example, a thunderstorm with rain and lighting was believed to indicate good growing weather, due to the warm air needed for the storm to form. (In Irish lore, thunder and lightning are associated with the god Lugh, and the sparks produced are believed to stem from his grandfather Balor whom he slayed.) However, since the weather around Lughnasadh was generally very unstable and torrential rain was no rarity, it was all the more important to harvest the corn quickly, as it could otherwise be spoiled by floods. In fact, these heavy torrents were so typical of this period of the year that they became later known as "Lammas floods" in several proverbs (Lammas being the Christian equivalent of Lughnasadh). Furthermore, there are sayings such as "August needs the dew as much as men need bread" and "After Lammas, corn ripens as much by night as by day", indicating that the abundant moisture was essential to the ripening process of crops.

Garland Sunday and the legend of St. Patrick and Crom Dubh

After the 9th century, the Óenach Tailten were only held irregularly, and in the wake of the Norman invasion of Ireland, the custom died out completely. Still, many traditions associated with Lughnasadh survived the decline of the ceremonial games. With the advent of Christianity in Ireland, many of them were recast as Christian rites: For example, the custom of climbing mounts and hills on Lughnasadh stayed alive in the shape of Christian pilgrimage routes, the most prominent being the ascension of Croagh Patrick. (According to folklore, Croagh Patrick is the place where Ireland's patron saint, Saint Patrick, fasted for 40 days, chasing away a flock of demonic birds that attacked him on the mountain with his bell; in other versions, it's said he banished all snakes from the island, which have been theorized to stand symbolically for pagan gods.)

Traditionally, the festival of Lughnasadh took place on August 1st, but over the course of the centuries, all festivities and gatherings have been moved to the Sunday nearest to it (either the last Sunday of July or the first Sunday of August). This might have been influenced by the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, as well as the Christian custom that Sunday was a day off work anyway - thus, it was naturally more suited for large assemblies. Yet another factor may have been that the harvest season was a very busy time for farmers, and since the weather conditions tended to be unpredictable around this time, it was probably wise to reap the harvest as soon as possible and don't let a regular work day go to waste.

Over time, the original name Lughnasadh was abandoned, and the festival was dubbed various regionally differing names, such as "Lammas Sunday", "Bilberry Sunday", "Mountain Sunday", or "Garland Sunday", the latter being derived from the widespread custom of strewing garlands of flowers onto festive mounts (this is very reminiscent of some Beltane customs, which also involve strewing about flowers for good luck). No matter the moniker it was known by, the festival continued to be an important date that marked the beginning of the harvest, and every farmer was expected to provide the people with fresh potatoes, bacon, and cabbage on this day - otherwise, they would be called a "wind farmer" for their lack of skill in husbandry. Likewise, it was considered improper to dig out any potatoes prior to this date, which was either seen as proof of economic mismanagement or neediness.

In some regions, the day was also known as "Crom Dubh Sunday", referring to a famous legend of St. Patrick overcoming a figure named Crom Dubh. Depending on the version, Crom Dubh is either a pagan chieftain, a god, a pirate, or a robber - in the end, however, he is always either defeated or converted by St. Patrick. It is highly likely that Crom Dubh is identical with Crom Cruach, the suspected chthonic god whom scholars assume to be similar to the Roman Hades and Greek Pluto. In the tale, Crom Dubh is described as "the lord of light and darkness" and master over the seasons, and is said to keep a fire burning near his property, throwing unlucky trespassers into it as punishment. (This is assumed to be a remnant of ancient sacrificial rites; there is the folk belief that the term "dubh"/"dua" means sacrifice, although Crom Dubh more likely translates to "black crooked one".) Sometimes, he is also said to possess a granary or a bull. Considering all of these parallels with the myth of Lugh's victory over Crom Cruach, it can be seen as a Christian adaptation of it, with St. Patrick replacing the Irish patron god.

One version of the story goes like this: "Once, there lived a chieftain in northern Ireland, in what is today known as the County Mayo. He was a resident of a place that is now called Dún Pádraig (Downpatrick Head), where he lived in a house by the sea, at a site known as Dún Briste. His name was Crom Dubh, and he is said to have been an extremely vicious, wicked, and obstinate man, only surpassed in evilness by his two sons, Téideach and Clonnach. In addition, Crom Dubh possessed two hounds, named Coinn Iothair and Saidhthe Suaraighe, which were as malicious as any dogs ever get. He used to tie them to the posts of his door, and if any poor soul should trespass on his property, he would unleash them and send them after them. For all the intruders who escaped the lacerating maws of his hounds, there was an even more brutal punishment waiting for them: At the edge of the cliff close to his home, he kept a large fire burning, which he used to throw any fugitives into the flames.

Crom Dubh, his sons and his hounds were infamous for their wickedness, and the common folk were so terrified of them they would tremble in fear at the mention of their names - and if they so much as heard the bark of a dog, people would seek shelter in their underground dwellings, fearing the arrival of Crom Dubh and his entourage. Despite his growing age, Crom Dubh remained quick as the wind and nimble as a hare, and regularly, he would go through the countryside to collect taxes from his subjects. Every time he did so, he would send his sons with his hounds ahead, who would announce to the residents that Crom Dubh was coming to collect his taxes. Each person had to pay as much as they could afford, which would all be loaded onto a sledge-like yoke Crom Dubh was dragging behind him. If anyone refused to pay their dues, they would be taken before Crom Dubh the next day - while sitting by his fire, Crom Dubh would pass judgement upon them, ending with the usual sentence of throwing the culprit into the flames.

Many plans were forged to overthrow Crom Dubh, but he was assisted by a leannán sidhe, a "fairy sweetheart", providing him with arcane knowledge and power, so he was able to overcome each and every attempt on his life. People would've given all they had for him to finally be put to an end, but alas, he and his minions held the power, so all they could do was to endure the ever-worsening persecution. Left without any hope or relief, the people had no other choice but to submit to Crom Dubh, because despite their detestation for him, it was still him who brought them the light of day, the darkness of the night, and the change of seasons.

This majestic, about 50 meters high sea stack known as Dún Briste is allegedly the place where Crom Dubh once lived, located just off the coast of Downpatrick Head near Ballycastle, County Mayo (Source)

One day, St. Patrick was going through Ireland, fulfilling his missionary obligation and baptizing many people. Eventually, he came to a place called Fó Choill (Foghill), an area that was densely forested back in the day. There, he could only convince a few inhabitants to listen to his preaching, but those that did took the new faith and let themselves be christened at a nearby well. After Patrick drew the sign of Christ on their foreheads, some pagans began telling him about Crom Dubh and his evil ways, asking him if it was in his and the Holy Father's power to put him in his place or make him convert to Christianity.

St. Patrick complied with their pleas, making his way to the dwelling of Crom Dubh. When he arrived there, Crom Dubh and his son Téideach didn't even notice him at first, as the two of them were engaged in a wrestling match. Saidhthe Suaraighe laid strechted out next to them, and only when the dog gave a howling bark did Crom Dubh and his son turn, seeing St. Patrick and his company of guardians approaching behind them. Subsequently, they charged at them, clapping with their hands to order the dog to attack Patrick's party. Meanwhile, Téideach whistled for Coinn Iotair, which had been taken on a hunting trip by Clonnach, but came running as swift as the wind when called for. Thus, Crom Dubh and his son set their dogs on the foreigner, unaware of who he was or where he came from. The two hounds came at Patrick with foaming mouths, raised fur, and a menacing blue light in their eyes, but the saint remained calm and drew a circle around him with his crozier. Just as the dogs were about to seize him, Patrick spoke a few holy words of protection, and the second he had uttered them, the two animals ceased all hostility, much to the dismay of Crom Dubh. They laid down their ears and wagged their tails, jumping at Patrick and licking his toes, with the saint returning the favor by stroking them. Afterwards, he continued to go after Crom Dubh, the two dogs now following behind him. Crom Dubh fled in the direction of his fire, hoping to lure Patrick there and throw him into it like all his other victims. However, St. Patrick had been forewarned about the fire's power and stayed away from him, instead taking a stone and drawing the sign of the cross on it. He cast the stone into the middle of the flames, banishing the fire to the deepest depths of the ground, so low that a hole called Poll Na Seantainne ("hole of the old fire") can be seen there to this day.

Crom Dubh, seeing that his fire had gone out and his hounds had disobeyed him - which was completely unheard of before - fled to his house together with his son, St. Patrick following after them. Patrick talked to Crom Dubh through the closed door, doing his best to convince him to take on a more righteous path, but Crom Dubh refused to listen to his words, and neither did he let himself be baptized. Still, he was unable to put up any resistance against Patrick, as the word of God was more powerful than the witchcraft of Crom Dubh's fairy sweetheart.

Furious, Crom Dubh and his son began snapping at the saint, who promptly rammed his crozier into the ground and split the cliff in half the house was built on, separating it from the mainland - henceforth, this cliff was known as Dún Briste, meaning "broken fort". Being cut off from the mainland by a swath of sea, Crom Dubh and Téideach were left to die miserably, with midges and crows feasting on their bodies. When Clonnach, Crom Dubh's second son, saw what had happened upon his return, he set fire to the surrounding cliffs out of fear of Patrick. However, the cliffs blazed so violently that Clonnach was soon trapped in the flames, burning to a heap of ashes himself.

Afterwards, St. Patrick returned to Fó Choill, where he was greeted by droves of people showering him with thanks for putting Crom Dubh to justice. The saint took all of them to a well nearby, not leaving a single person unbaptized. In their celebratory spirits, the people thoroughly cleansed the walls of the well and the area around it, putting up forked sticks and tree branches with white and blue ribbons tied to them. They fell onto their knees, speaking prayers of gratitude to God and hailing St. Patrick for putting an end to Crom Dubh's dominion, after which everyone drank three sips from the well's water.

From then on, people would always make a pilgrimage to Cill Chuimin (Kilcummin) each year, the place where the well was located, coming together from far and wide to celebrate the anniversary of Crom Dubh's defeat. The date was always the last Sunday of the seven month, the month the Irish speakers called Lúnasa, while the Sunday was known as Crom Dubh's Sunday - to the English speakers, however, this Sunday became known as Garland Sunday."

Legend has it that Dún Briste, an island consisting of a steep chunk of cliff that has broken off from the coast near Downpatrick Head, is the piece of land where Crom Dubh's once lived and which St. Patrick separated from the mainland. Lying just a few miles north of Ballycastle in the County Mayo, the site is a tourist attraction to this day, and many people come to gaze from the edge of Poll Na Seantainne - the blowhole allegedly created by St. Patrick when he threw his stone into Crom Dubh's fire - into the turbulent sea below.

Whether one wants to believe it or not, the legend of Crom Dubh stands as a testament that despite the typical message of the superiority of Christianity, the old Irish myths did not die out, but rather were reinterpreted with the figures being replaced by different actors. Instead of trying to suppress and eradicate native Irish culture, the new Christian traditions merged with the old pagan ones, creating a unique sub-branch of Christianity.

Modern traditions and Christian Lammas

Up until the 20th century, old Lughnasadh traditions were still widely practiced in Ireland. In 1924, there was even an attempt to revive the Tailteann Games as a modern sporting competition held shortly after the Summer Olympics. The Games were primarily open to people of Irish birth or ancestry from all over the world, but some prominent athletes who had participated in the Olympics were also invited as guests. The event included both traditional sports as well as modern ones, such as races with motorcycles, speedboats, cars, and airplanes (the only disciplines that were excluded were soccer, rugby, and hockey, as they were deemed too "un-Irish" for the liking of the hosts). Furthermore, there was a vast cultural program, consisting of artistic competitions in literature, poetry, music, and dancing, in addition to various commercial displays and exhibitions of arts and crafts. The Tailteann Games were held in the years 1924, 1928, and 1932, and even managed to garner a significant amount of public attention. However, when the political party Fianna Fáil won the elections of 1932, the Games lost their financial support, as they were closely associated with the previous ruling party, Cumann na nGaedheal, and their post-Civil War politics. A committee was established to examine the possibility of staging any more Tailteann Games in the future, and despite an event being technically deemed possible in 1939, Irish politician Éamon de Valera used the split among Irish athletics federations as a pretense to delay further consideration. With the onset of the Second World War in 1939, any prospect of holding an event in the near future naturally faded away, and afterwards, the issue was never brought up again.

Nevertheless, some of the old mountain pilgrimage routes stayed alive into the 21st century, the most famous being the one to the top of Croagh Patrick, colloquially known as "The Reek". On Reek Sunday, a modern name for Garland Sunday, thousands of pilgrims come to climb to the top of the mountain, a journey that the most pious ones undertake barefoot. The procession is always led by the Archbishop of Tuam, who leads them to a small chapel at a summit where a mass is held. During their ascent, some people commit "rounding rituals", which involve walking sunwise around landmarks and monuments on the mountain, for example the cairn of Leacht Benáin ("Benan's grave"), Leaba Phádraig ("Patrick's bed"), Reilig Mhuire ("Mary's cementry"), and the summit's circular perimeter. Furthermore, people still make pilgrimages to holy wells, such as Tobernault in the County Sligo, where a special service is held on Garland Sunday.

Ever since the Neolithic Age, Croagh Patrick has been of spiritual significance, being considered a holy mountain by Ancient Celts and modern Irish Christians alike (Source)

The Puck Fair, a festival held each year in Killorglin, County Kerry from August 10th to 12th, is also believed to go back to Lughnasadh. At the beginning, a wild goat is captured and brought into town, which is then crowned "King Puck" while a local girl is chosen as the "Queen of Puck" (the goat has been hypothesized to be an ancient fertility symbol). Afterwards, the goat is put into a cage positioned on an elevated platform, where it stays for the next three days. Traditionally, a horse fair will take place on the first day of the festival and a cattle fair on the second. Finally, on the third day, the goat will be released from its enclosure and brought back to the mountains. The festivities include a parade, folk music, dancing, various workshops for arts and crafts, as well as a large market where all kinds of vendors to offer their wares to the numerous tourists that visit each year. In recent years, similar festivals have also been introduced in other regions of Ireland, such as Gweedore, Sligo, Brandon, and Rathangan. In Craggaunowen, an open-air museum in the County Clare, there is a yearly Lughnasadh festival featuring historical re-enactors. They portray various aspects of daily life in Gaelic Ireland, complete with replica clothing, artifacts, weapons, and jewelry. In 2011, the Irish television channel RTÉ even broadcasted a "Lughnasa Live" program from Craggaunowen. Aside from this, a similar Lughnasadh Fair is held in Carrickfergus Castle each year, one of the best preserved medieval castles in Northern Ireland.

As for other Celtic countries, the people of Wales celebrate a festival known as Gŵyl Awst (pronounced gwill oust), translating to "feast of August". Although a lot of old Welsh customs are unfortunately discontinued, but it can be concluded that Gŵyl Awst is an agricultural festival, with some regional differences: For example, in Cardiganshire, the central focus isn't on harvesting the fields, but rather the ffest y bugeiliad ("shepherd's feast"), which was mainly for cowherds and shepherds as sheep would also be shorn around this time. Meanwhile, in areas with a greater focus on arable farming, there was the tradition of dwrn fedi ("first reaping"), which had all farmers of the community coming together. The reapers would assist each other and coordinate their work so they could harvest the fields of a single farm each day, and upon fulfilling their task, the gathered bounty was exchanged and shared with the other workers as a sign of gratitude. At Gŵyl Awst, various special treats would also be enjoyed, many of them including oats, such as Siot, a type of crumbled oatcake steeped in buttermilk. Furthermore, we know from similar mountain climbing customs similar to those of Lughnasadh from Brecknockshire: On August 1st, pilgrims from would make their way to the Beacons, a mountain range between the counties of Carmarthenshire and Glamorgan. Their destination was the lake Llyn y Fan Fach, where they would watch out for the Lady of the Lake and collect a few flasks of healing water to take them home with them. This tradition most likely originated from an old legend about a maiden who arose from the lake and married a mortal man, begetting a son named Rhiwallon who was taught the art of healing by his mother and later became the progenitor of the famous physicians of Myddfai - a story which seems quite reminiscent of the myths about Celtic fountain spirits.

In Brittany, there is a similar festival called Gouel an Eost, a name possibly derived from Gŵyl Awst. The event is meant to celebrate the harvest, featuring an exhibition of old tractors and harvesting machines, as well as people who re-enact the traditional practices of threshing, plowing, bread-making, and other old-fashioned professions. It's meant to be a vivid window into the lives of farmers from centuries past, portraying their sorrows, their joys, and the solidarity and teamwork among their community. In addition, visitors have the opportunity to behold parade with 400 costumed extras, taste Breton specialties such as crêpes and rata (a type of stew made from meat and vegetables that was eaten by farmers), and enjoy folk music and dancing by watching performances of local Celtic circles and bagadoù bands (musical ensembles featuring bagpipes, bombards, and drums). To this date, the festival takes place each year in the commune of Plougoulm, celebrating Celtic and Breton culture alike.

Meanwhile, in England, the harvest festival became Christianized as Lammas. (Interestingly, the feast was sometimes dubbed "Gule of August" in medieval England and Scotland, which may be derived from Gŵyl Awst as well). Lammas Day, also known as Loaf Mass Day ("loaf" referring to bread and "mass" to the Eucharist), is a Christian holiday celebrated primarily in the English-speaking countries of the Northern Hemisphere. It involves the blessing of the First Fruits of harvest, and usually, a loaf of bread baked from the new crops is brought to the church to be blessed. (There are accounts that the blessed loaf was used for protective rituals in Anglo-Saxon times: The bread would be broken into four parts, which farmers would place at all four corners of a barn to protect the stored grain.) Church processions to bakeries are also a common custom, with those working there receiving blessings from the Christian clergy. In the town of Exeter in the County Devon, people still celebrate a yearly Lammas Fair, a tradition that supposedly goes back 900 years. It starts with a procession led by the Lord Mayor of the town, carrying a large pole adorned with colorful ribbons, flowers, and a white, stuffed glove on top. Once they arrive at the guildhall, the Lord Mayor will read a proclamation from King Edward III, declaring the fair open, while the pole with the glove will be hung over the building for the three-day duration of the festival (the glove is an old symbol of royal protection, signaling that the city is open for trade). Although the event is held on the first Thursday in July rather than August 1st nowadays, it still bears a lot of resemblance with the fairs and markets typical of Lughnasadh.

Some remnants of Lughnasadh even carried over to the Irish diaspora: Many families with Irish roots still tend to choose August as the time to host family reunions and parties. However, due to modern work schedules, such events have often been to adjacent holidays, for example Indendence Day (July 4th) in the USA.

Nevertheless, the influence of Lughnasadh is still alive today, and although it may not have garnered the same public attention as Beltane or Samhain, the harvest festival was undoubtedly a very important occasion for our ancestors. So, perhaps we should take a moment to value the fruits, vegetables, and grain that feed us, and remember to not take earth's bounty for granted. Also, make sure to show appreciation to your fellow human beings: If your friends are in need of help, be ready to lend a hardworking hand, and if someone does you a favor, always remember their kindness.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alright, that's a wrap! I had a lot of fun researching about Lughnasadh, especially since it gave me the opportunity to shed a little more light on this somewhat unknown festival. Thus, I hope you enjoyed reading this article as well, and if you did, I would be delighted if you stayed tuned for the last issue on November 1st. Next up: the Samhain rematch! ;-)

#lughnasadh#paganism#celtic paganism#tailtiu goddess#lugh god#crom cruach#crom dubh#st patrick#garland sunday#lammas#harvest festival

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

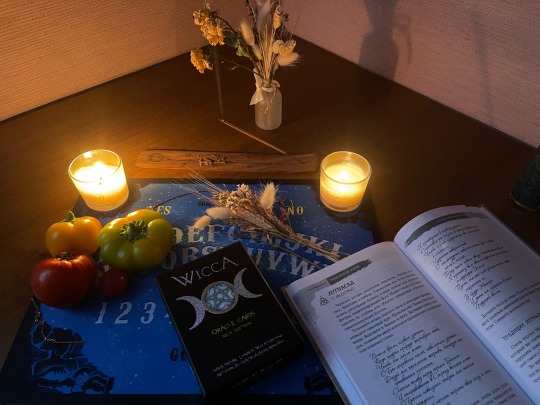

Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh marque une transition essentielle dans le cycle annuel : le glissement de l’été à l’automne et l’émergence de la période des moissons. Cette fête est un jalon symbolique, riche en traditions et en rituels. Lughnasadh, en incarnant la sagesse ancestrale et la puissance de la nature, donne naissance à une symphonie symbolique complexe. Les quatre célébrations saisonnières, qui jalonnent le cœur du cycle festif annuel, sont des instants singuliers où l’on rend hommage aux différents aspects de la vie universelle et aux activités du clan. Ces festivités, qui comprennent Samain, Imbolc, Beltaine et Lugnasad, soulignent chacune des traits distinctifs de leur saison respective.

Samain, célébrée le 1er novembre, met l’accent sur la valeur de la solidarité familiale et clanique. À l’automne, saison des semailles et des chasses, la cohésion et la coopération du clan deviennent primordiales. C’est donc une période privilégiée pour se rassembler et resserrer les liens familiaux. Imbolc, qui a lieu le 2 février, est une fête de purification et de recueillement. L’hiver, par sa nature même, est une période de retraite et de renouveau. Cette fête marque un temps de purification du foyer, symbolisant un nettoyage en profondeur avant l’arrivée du printemps. Beltaine, célébrée le 1er mai, est un hommage à la jeunesse, à la croissance et à l’amour. Le printemps, saison du renouveau et de l’épanouissement, est une période où la compétition entre les jeunes est mise en avant. C’est un temps de croissance et de compétition saine, où l’amour fleurit. Lugnasad, enfin, célébrée le 1er août, est un jour de festin, marquant la saison estivale qui est le moment de savourer les fruits des premières récoltes. Cette fête est associée à la maturité et à la récolte, symbolisant l’âge de 44 ans, où l’on moissonne ce que l’on a semé dans sa vie. Lugnasad représente l’âge mature, le temps de récolter matériellement les fruits de ce que nous avons semé et cultivé au cours de notre vie, une période marquée par la notion de maturité et de moisson.

Le Dieu Lugh aurait instauré cette fête en mémoire de sa mère Tailtiu dont un tumulus subsiste à Teltown en Irlande. La mère de Lug succomba d’épuisement après avoir défriché toute l’Irlande, préparant ainsi tout le pays à l’agriculture. Tailtiu est plus qu’une simple mère pour Lug, elle incarne une grande Déesse, représentant un aspect de la Terre-Mère.

Cette fête était l’occasion d’un grand rassemblement où tous les problèmes étaient réglés sous l’œil vigilant de la mère (de Lugh), à travers des jeux (compétition) ou autres… Par facilité, cette fête a été associée à la moisson car Tailtiu, qui représente la Terre-Mère, est indéniablement la génératrice de la moisson. Cependant, c’est Lugh qui a instauré cette fête en son honneur et non pour la moisson…

Le nom de cette fête renvoie au dieu Lugh, dont l’influence se retrouve dans le nom de nombreuses villes européennes et de tribus celtiques. Il est perçu comme un dieu aux multiples facettes, fortement associé à la souveraineté et à la magie.

En sommes, Lugh partage de nombreux points communs avec le dieu Wotan. Tout comme Wotan, Lugh est reconnu pour sa vaste connaissance des arts magiques. Il est également associé aux corbeaux, pratique l’art de la magie, et est souvent représenté avec un œil fermé lors de certains rituels. Lugh, à l’image de Wotan, est le patron des poètes, conduit les armées au combat, et sa lance est son arme de prédilection.

En outre, Freyr, le dieu nordique de la fertilité et des récoltes, est honoré par le Freysblöt, une cérémonie d’offrandes qui marque aussi le début de la moisson. Thor, qui aide également aux récoltes, et sa femme Sif, dont les cheveux dorés peuvent évoquer les champs de blé mûrs, sont également vénérés lors de cette fête.

Au cours du Freysblöt, la première gerbe de blé récoltée est attachée et bénie en l’honneur des dieux et des vaettir, les esprits de la terre. Le pain, cuit à partir de ce premier blé moissonné, devient une offrande partagée avec toute la communauté.

Autrefois, cette célébration revêtait une importance vitale pour nos ancêtres. Une mauvaise récolte pouvait entraîner de nombreuses morts durant l’hiver. Aujourd’hui, nous rendons hommage à Freyr pour toutes les récoltes abondantes dont nous avons bénéficié. Si certaines années étaient particulièrement difficiles, des sacrifices drastiques étaient réalisés. Nous honorons Freyr en lui présentant un blöt, un festin issu de nos jardins et de nos champs.

Il est vrai que ce que nous savons de manière avérée concernant ces célébrations antiques est parfois fragmentaire. Freyfaxi, par example, est une création contemporaine qui correspond approximativement avec le jour de Larsok, le 10 août, cité dans le Primstav. Historiquement, à cette date, il était de coutume d’avoir fini de stocker le foin pour assurer l’approvisionnement en lait durant l’hiver. Bien que Larsok soit parfois interprétée comme une fête des moissons, certains chercheurs proposent qu’elle pourrait être liée à la fête de Saint-Laurent.

En Grande-Bretagne, des fêtes de la moisson ont été célébrées depuis les temps anciens pour remercier les divinités pour les récoltes abondantes. Selon la tradition locale, ces cérémonies ont lieu en septembre ou en octobre. Néanmoins, une fête des moissons précoce avait lieu le 1er août, nommée Lammas, « messe du pain », ou Hlalmaesse. Il s’agissait d’une cérémonie pour marquer le début de la saison de la moisson. À Lammas, un pain réalisé à partir de la nouvelle récolte était apporté, symbolisant ainsi le commencement de la période des moissons. Cette cérémonie se situait à mi-chemin entre le solstice d’été et l’équinoxe de septembre, indiquant une étape importante du cycle agricole.

De plus, Lughnasadh est une fête officielle en Irlande et une célébration gaélique, qui a des racines dans le paganisme et est mentionnée dans certaines des plus anciennes littératures irlandaises. Historiquement observée en Irlande, en Écosse et sur l’île de Man, Lughnasadh réunit de grands groupes pour des cérémonies religieuses, des compétitions athlétiques rituelles, des banquets, des rencontres amoureuses et des échanges commerciaux. La fête survient à un moment critique pour les communautés agricoles : les réserves de l’année précédente sont épuisées et les nouvelles récoltes ne sont pas encore prêtes.

En Suisse également, le 1er août est un jour férié. Traditionnellement, Lughnasadh a toujours été associée au premier jour d’août. Cependant, au cours des siècles récents, une grande partie des rassemblements et des festivités qui lui sont associés ont été déplacés vers les dimanches les plus proches – soit le dernier dimanche de juillet ou le premier dimanche d’août. On pense que cela est dû à l’incertitude du temps et au fait que la période des récoltes était chargée, ce qui rendait difficile de sacrifier des jours de travail. Comme le dimanche aurait de toute façon été un jour de repos, il était logique de célébrer à ce moment-là. Le passage au calendrier grégorien a également pu influencer cette modification.

Enfin, Lughnasadh partage des thèmes agricoles avec Lammas, ou hlalmaesse. Au fil du temps, ces deux fêtes se sont entremêlées au point qu’il est souvent difficile de distinguer les éléments spécifiques à chacune.

Il est dit de Lughnassadh qu’elle est la fête du plaisir, où il convient de célébrer le phénomène connu sous le nom de plaisir sensible. C’est pourquoi lors du banquet, un squelette accompagne les hôtes à table. Qu’est-ce que le plaisir, c’est-à-dire ce stimulus qui détermine à peu près toutes les décisions? Il procède de la lumière tirée de quelque chose. Chacun, à son niveau, tire sa lumière, son plaisir, du divin. Dans l’ancienne religion, c’est Frey qui raffine le fait de tirer sa vitalité des joies de ce monde.

Il est dit que c’est lors de cette fête qu’il faut aller dans la forêt pour explorer et trouver le petit peuple, avec une loupiote comme Hermod allant voir Baldr.

Effectivement, la forêt étant le symbole du subconscient, il est raconté qu’à la veille de Lughnasadh, il est le bon temps de se promener en forêt, de pénétrer dans les bois et de parcourir un sentier. C’est à ce moment précis, dit-on, que le petit peuple devient visible. Farfadets, lutins, fées et nains sont alors au rendez-vous. On souligne l’importance de renouveler les protections magiques pour les récoltes, le bétail, les habitations et toutes autres possessions. Les maisons se parent souvent d’une croix de sorbier, en forme de Naudiz, accrochée au-dessus des portes, un symbole protecteur fort. On prépare des gâteaux avec les ingrédients disponibles et on les mange dans les champs ou les pâturages. De petits morceaux sont jetés par-dessus l’épaule alternativement à gauche et à droite en guise d’offrandes aux esprits de la nature pour favoriser les récoltes et aux prédateurs pour demander d’épargner le bétail.

À l’aube de Lughnasadh, nos ancêtres et leurs enfants célèbrent une série de rites et de cérémonies. Une coupe solennelle du premier grain est effectuée, dont une offrande est faite à la divinité, portée à un endroit élevé et enterrée. Un repas composé de la nouvelle récolte et de myrtilles rassemble la communauté entière. Par ailleurs, une danse-jeu rituelle peut-être illustre une lutte pour une déesse et un combat rituel.

Ce rituel complexe implique aussi l’installation d’une tête en pierre sculptée au sommet de la colline et une victoire sur elle par un acteur incarnant Lugh/Wotan. La célébration se prolonge ainsi sur trois jours, avec le jeune dieu Lugh, ou son représentant humain, à la tête des festivités.

En Irlande, on gravi de nombreuses montagnes et collines importantes pour ce festival. L’occasion est marquée par des repas, des boissons, de la danse, de la musique folklorique, des jeux, des rencontres amoureuses, ainsi que des compétitions athlétiques et sportives. Dans certaines traditions, tous portent des fleurs en grimpant la colline et ils les enterrent ensuite au sommet en signe de la fin de l’été.

Parmi les autres traditions, les gens préparent un gâteau spécial appelé le lunastain, qui est à l’origine une offrande aux dieux. Certains puits sacrés sont visités, où les visiteurs prient pour la santé en marchant dans le sens du soleil autour du puits, laissant ensuite des offrandes, généralement des pièces de monnaie ou des clooties.

Finalement, nous purifions notre bétail en le guidant à travers un cours d’eau. Nous dédions les premiers fruits de nos récoltes aux divinités et aux esprits. Des poupées sont fabriquées à partir des épis de blé et servent de talismans pour assurer la protection des personnes, des champs, du bétail et des possessions.

« Le mois d’août a besoin de la rosée autant que les hommes ont besoin de pain. » « Après Lammas, le maïs mûrit autant la nuit que le jour. »

En conclusion

Lughnasadh, cette fête ancestrale, représente un symbole profond de l’interdépendance entre l’homme et la nature et du respect de ses cycles. Elle rappelle l’importance de la gratitude pour les dons que nous recevons de la terre. Aujourd’hui, alors que nous célébrons cette journée, nous nous souvenons de ces traditions et nous les adaptons à notre époque moderne, tout en préservant l’esprit et le sens des anciennes coutumes. Que ces rituels et célébrations nous rappellent constamment notre lien avec la nature et l’importance de vivre en harmonie avec elle.

0 notes

Text

Lugh, God of Oaths and Vows

In my deity guide for him, I mentioned that Lugh, amongst other things, is the god of oaths and vows

Recently someone messaged me and asked:

Hi there. I found your Lugh post from back in January. Thank you for posting such a wonderfully thorough discussion on Lugh. I was wondering in your research, upg, or general knowledge if you knew of any myths regarding Lugh renewing his vows or something to that extent and thus why the renewal of vows and/or the making of oaths is done at Lughnasadh?

So I did some digging.

During the festival of Lughnasadh legal matters were discussed, an óenach was held and trial marriages began.

There are plenty of sources that state that Lugh is associated with oaths and promises, though not all of them explain why.

Some suggest that that the names given to the god throughout the Gaelic-Celtic cultures gives us clues indicating that Lugh is the god of oaths.

Such examples being:

The welsh name for the god, Llew, likely comes from the Welsh word “llw” which means “an oath”.

As well, the Irish name for the god, Lug or Lugh, may come from the Old Irish word “luige” or “luge” which means “oath” or “swearing”. If this is the case, then the name Lugus, another name given to the god, might mean “God of Vows”/“God of Oaths”.

The best source I’ve found for this information is in the book The Gods of the Celts and Indo-Europeans by Garrett Olmsted (particularly page 110); Olmsted also has quite a few sources in his book.

As you mentioned, I have read a few sources stating that some people believe that the story behind the holiday of Lughnasadh is one of Lugh renewing his vows to his wives. I haven’t, however, been able to find any evidence of this in the history of the holiday.

It could be that because legal dealings are held on Lughnasadh, the mythos sort of picked that up through time.

If anyone knows of a source or sources that can otherwise explain why the story of Lugh renewing vows came about please send it my way!

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flower magick 🌺

#photography#still life#flowers#witch#pagan#art#witchcraft#tarot cards#tarot#lammas#lugnasad#summer#echinacea#calendula#aster#crystals#amethyst#magick#mine

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

#paganism#calender#samhain#pagan#paganpride#yule#imbolc#ostara#beltane#mabon#lugnasad#litha#lammas#summer solstice#winter solstice#spring equinox#fall equinox

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lughnasadh bread 🌞🌾🍞 Je n’ai pas eu le temps de célébrer quoi que ce soit pour Lughnasadh, mais j’ai tout de même pris le temps de cuisiner un petit pain aux figues pour l’occasion. C’est tellement bon que ça vaut tous les rituels du monde 😋🥖🌞 La suite de la célébration attendra quelques jours ! Peu importe, c’est un sabbat que j’aime fêter sur plusieurs jours. Et vous ? Vous avez fait quelque chose ? #lughnasadh #lugnasad #lammas #lughsday #summer #lughnasadhbread #breadbaking #bread #homemade #homemadebread #cooking #baking #bake #baker #figbread #kitchenwitch #kitchenwitchery #pagan #paganism #witch #witchcraft #wheeloftheyear #merrylughnasadh #sabbat #celebration #tradition #countrysidelife #ifeellikeasimincottageliving #imsostrongieatpainforbreakfast https://www.instagram.com/p/CSEwDN1CUHs/?utm_medium=tumblr

#lughnasadh#lugnasad#lammas#lughsday#summer#lughnasadhbread#breadbaking#bread#homemade#homemadebread#cooking#baking#bake#baker#figbread#kitchenwitch#kitchenwitchery#pagan#paganism#witch#witchcraft#wheeloftheyear#merrylughnasadh#sabbat#celebration#tradition#countrysidelife#ifeellikeasimincottageliving#imsostrongieatpainforbreakfast

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Así lo a designado Lugh que brillará por última vez, Al caer la tarde llega el crepúsculo Dando paso al otoño. Que la luz resplandezca más que nunca. Bendecido Lammas tengan todos... . . . . . . . . . #lammas #lugh #lugnasad #lugnasadh https://www.instagram.com/p/CSCcaBTr0Gx/?utm_medium=tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

instagram

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to prep for Lammas ❂

I know witchy fellas, it’s boiling hot & sunny out there. But we gotta put it in the effort. All together. Till the end. Till Lammas.

Briefly explained, Lammas or Lughnasadh opens the harvest season around August 1st and our ancestors would know the perfect timing of it by watching the rise of the star Sirius at the dawn after a long while not showing. This sabbat originated by the Celts whom used to propitiate Lugh to ensure sunny weather and a fruitful harvest. He was their god of Light, excellently proficient in all arts & protector of thieves, travelers and merchants. Moving to the southern areas, this celebration was still existing in a more earthy practical variant: mother Earth, plants, fresh produce, seeds and grains were the actual focus. These other people couldn’t care less about Lugh. They only cared about showing gratitude to Nature as a whole, often by baking the first LOAF MASS of the season (Lammas, a bread loaf) after months of summer break - we should stop baking at home from Beltane day till Lammas day, unless we’re home-based bakers and do that for a living;)

So, as usual, in this post I’m going to give you tips & ideas to prep for august 1st. Which means these are not things you should do on the very day, but BEFORE. Don’t rush last minute darlings. We can do this.

Let’s get readayyyy. ✽

1. Local farmers’ markets should become a routine. Ok, hands down we all need the supermarket to survive on a daily basis but you can surely minimize your shopping list, so you can go buy fresh produce at some farmers’ market. Buy organic stuff there, not at the mall. This is a good easy way to re-establish a direct contact with Earth and welcome earthy energies into your life. Plus, it’s going to be a refreshing walk every time.

2. Improve the lighting in your house/room. Besides Samhain, this is by far the best time of the year to purchase new lamps, led lights, lanterns; fix bulbs that are out, remove useless/broken curtains, buy candles, add fairy lights everywhere etc... Being a metaphor of the sunny weather, daylight and artificial lighting in general must be of primary importance in your environment. Enhance natural lighting during the day, set up a nice and diffused lowlight illumination system at night. Don’t forget your backyard ‘cause...

3. You should take good care of your garden. I don’t care how busy you are, we all have at least 5 spare minutes to trim out dead leaves from our plants. If you own a piece of land or have a rather big veg garden, please don’t forget about it. Pay special attention to your plants/trees, do a little bit of cleaning every day, pick what’s ripe, cut out dead leaves, get creative with your lawn mower, water the vases, work the ground... The goal is to have a beautiful, curated garden by august 1st. But if you don’t have a garden or similar...

3.2. Buy your fav aromatic plant & look after it. Choose herbs that you prefer adding to your meals (if you’re a diy pro or make your own soaps etc.. feel free to use that fragrant plant in your products), so that you’ll be able to use it quite often without forcing yourself. I personally do it with basil. Basil is my daily go-to, I love its smell and taste. Again, the goal is to buy a plant in July and prove to Mother Nature that you can nurture it properly until at least august 1st. Get in touch with the “green world” and upgrade your basic skills. In other words...

4. Try to excel in every project/activity you start. Remember what you read earlier? Blame Lugh for this one. Lammas day is like a test: if you want Nature to be by your side during harvest time, you must earn its trust through proving that you’re able to achieve great results - because you’re a hard worker. July is about learning, attending classes, practicing, studying. My advice would be to not start a bunch of random projects now: be picky and commit to only one or a few. Be honest with yourself, modest with timing and consistent in everyday practice so that in august you’ll be skilled enough to unleash your best potential. This is your time to shine!

5. Do your research on baking bread. Yes, exactly. Read recipes, articles, books etc... On Lammas day you want to have fun baking your first bread loaf of the season, so you’d better be prepared. It’s a fun experience even if you’re not a pro baker, at least you can try a new hobby to fill your free morning/evening. But baking a beautifully decorated, tasty, fragrant bread loaf would take Lammas to the next level though.

If you don’t own an oven, purchase a small electric one for less than 50$. It’ll be useful to cook other foods in the future without stressing the hell out of your microwave.

*for our celiac fellas*: grains and gluten are clearly off-limits for you. However, Lammas’ celebration involves CORN as well. Try to make your gluten-free dough with corn flour, rice flour or other ingredients that are suitable for you. Focaccia, polenta and pizza doughs are also suitable for the occasion.

6. Include apples, grapes and corn in you cosmetics or in your diet. Since these fruits are in season, why not take heed of their benefits? Simply buy things like apple shampoo, grape lip balm, apple snacks, grape masks... A BAG OF CRISPY POP CORN...These are valid examples. You have a wide range of choice, you’ve got the powahhh.

7. Grab a book and a glass of Albariño/Pinot Noir/Rosé. That’s how you pamper yourself before Lammas. A rocking chair in the garden, proper lighting for reading, a cushion, your fav book and a glass of fine wine.

Alternatively, you can elegantly snack on grapes or sip some super refreshing apple juice from a chic crystal goblet!

8. Develop a grounding routine. For those who are new to the grounding concept, I’ll break it down real quick. We’re always moving, on the go, running, rushing, driving, working out, traveling, walking, cleaning, fidgeting, passively entertained, distracted by screens or social media etc... The practice of grounding promotes the exact opposite to reach inner balance and fulfillment. Basically, it’s very good to be swift and active, but being incapable of sitting still while quietly dealing with ourselves is a huge, major problem. Imagine rooting yourself into the soil: you can lay down or sit comfortably on the ground without a mat and really feel the Earth underneath. Close your eyes, breathe deeply, choose a meditation method that you like, visualize yourself being as static and peaceful as a tree... Or simply be. You’ll find a way to contemplate these OFFLINE moments away from photos, screens, sounds, people... This routine should take 10-20 minutes of your day. Make sure it takes place in nature, or alternatively in places where there’s actual grass, ground or nearby your (aromatic) plants so you can touch them if you need to.

9. Get creative with corn magic and corn art. Lammas has a solid tradition of corn use for various purposes. As you’re prepping for the big day, start featuring corn kernel/cobs in your magic. If you don’t practice - which is totally fine - carry a small amulet bag with corn inside with you. If you’re an artist or crafter, paint the kornel or use cobs for artwork!

10. Be out in the sunlight, sun bathe or simply breathe fresh air, get outside, enjoy all things outdoors :)

Hope this was helpful and inspirational fo you all, good luck and happy Lammas darlings.

Floods of love, msmoonfire (IG: @msmoonfire)

#wicca#pagan#sabbat#sabbats#Wheel of the Year#paganism#lammas#lughnasadh#august#wiccan#magick#magic#corn#celiac#festival#lugnasad#handfasting#bread#baking#kitchen magic#spells#spellwork#ritual#rituals#spell#meditation#witches#witchery#witchcraft#witchblr

325 notes

·

View notes

Photo

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Lughnasadh #Lúnasa #Lugnasad #Lammas #Lammastide Oh Lugh ✨🔥✨ beloved and revered Lugh, Lord of the light and the storms, blessed be your beautiful day, in this day we celebrate the sacred light to all the humble warrior Gods like you, you who fought for the living and triumphed over the world of the dead 💥 we celebrate together your triumph and the name of your mother this day, may fill us with your blessings today, to empower us this new cycle and bring us your magnificent present today, and everyday 🧿 So mote it be.

#wicca#witchcraft#pagan#magick#magic#witches#shaman#wiccan#astrology#spirituality#witch#paganism#shamanism#lunasa#lughnasadh#lugnasad#lammas#lammastide#wheel of the year#heathen#heathenry#druid#druids#druidcraft

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belated Lughnasadh Blessings

#aoibhneas speaks#gaelic polytheist+#gaelic polytheist#gaelic polytheism#polytheist#polytheism#lughnasadh#lughnasa#lúnasa#lugnasad

11 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Let’s celebrate August and the climax of Summer at this Lugnasad festival *** Beauty, blossoming of nature, fruits and flowers in abundance *** Love and Peace to All ♥ Music by Asher Fulero Célébrons Août et l'apogée de l'été en cette fête de Lugnasad *** Beauté, épanouissement de la nature, fruits et fleurs en abondance *** Amour et Paix à Tous ♥

7 notes

·

View notes