#land of poets and thinkers

Text

Erziraphael

In german, Aziraphales name is "Erziraphael".

It's really weird, when I watch Good Omens in german (when anybody joins me), when otherwise I (re)watch it in english. And of course I stroll through (ok, I live in) this fandom. But I think germans would pronounce it REALLY weird, like "Azirafale":

every A is like the "u" in but

Z like in "tsk"

I like you would spell "e"

take the R from "great" but form it in the back of your throat

and the E like the "a" in about

Nice? No? I think so too! It sounds strange!

So I think it's for the better, to change it in german. I'm sure, my mother would pronounce it as I've described (I'll try it tomorrow and report back!) I assume, they changed the name, because it is similar to Archangel Raphael, wich is familiar for a german tounge.

I wrote this because of another post, but I can't, find it anymore.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(1/54) “We begin in darkness. A siren screams. The invaders come from the desert in a cloud of dust. The king gathers his army at a mountain castle. A single battle decides our fate. The battle burns, the din of drums, the clash of axes, the spark of swords. The dirt turns clay with blood. The sun goes down on a fallen flag. The day is lost. The king is gone. Our people are left defenseless. The only weapon we have left is our voice. So they come for our words. Scholars are murdered, books are burned, entire libraries are turned to dust. Until nothing remains. Not even memories of who we were. Silence. The sun comes up on a knight galloping across the land. He summons the teachers, the scholars, the authors, the thinkers. He tells them to gather the words that remain: the books, the scrolls, the letters, the verses. Everything that escaped the burning pits. Then he summons the sages. The keepers of our oldest myths, from before the written word. He copies their stories onto the page. Then when all has been gathered, all of the words, only then does he summon a poet. It had to be a poet. Because poetry is music. It sinks into the memory. And in this land of endless war, the only safe library is the memory of the people. It is said that at any given time there are one hundred thousand poets in Iran, but only one is chosen. A single poet, for a sacred mission. Put it all in a poem. Everything they’re trying to destroy. The entire story of our people. Our kings. Our queens. Our castles. Our banquets. Our songs and celebrations. Our goblets filled with wine. Our roasted kebabs. Our moonlit gardens. Our caravans of riches: silken carpets, amber, musk, goblets filled with diamonds, goblets filled with rubies, goblets filled with pearls. Our mountains. Our rivers. Our soil. Our borders. Our battles. Our crumbled castles. Our fallen flags. Our blood. Who we were. Who we were! Our culture. Our wisdom. Our choices. And our words. All of our words. Three thousand years of words, a castle of words! That no wind or rain will destroy! However long it takes, put it all in a poem. All of Iran, in a single poem. A torch to rage against the night! A voice to echo in the dark.”

در تاریکی آغاز میکنیم. بانگ آژیری برمیخیزد. غارتگران بیابانی در هالهای از گرد و غبار فرا میرسند. شاهنشاه سپاهیانش را پیرامون کاخی کوهستانی گرد میآورد. تکنبردی سرنوشتساز است. سوزندگیهای نبرد، بانگ کوس و دراها، چکاچاک تبرها، درخشش شمشیرها. خاکِ آغشته به خون گِل میشود. خورشید درفش افتاده را به شب میسپارد. نبرد از دست رفته است. پادشاه نیز رفته است. و مردمان بیدفاع ماندهاند. اینک سخن، تنها جنگافزار ماست. زین روست که بر واژگانمان میتازند. دانشمندان را میکشند، کتابها را میسوزانند، کتابخانهها را با خاک یکسان میکنند آنچنان که هیچ نمانَد. حتا یادمانی از آن که بودهایم. خاموشی. خورشید بر سواری که در سرتاسر زمین میتازد پرتوافشان است. اوست که آموزگاران را فرا میخواند، دانشمندان را، نویسندگان را، اندیشمندان را. و از آنان میخواهد تا همهی واژگانِ بازمانده را فراهم آورند. کتابها، طومارها، نامهها، سرودهها. و هر آنچه از شرارههای سوزان آتش دور مانده است. آنگاه فرزانگان را فرا میخواند. نگهبانان اسطورههای کهن، از پیشین زمان. داستانهاشان را بر برگها مینویسند. با فراهم آمدن این همه، هنگام آن رسیده است تا سرایندهای توانا بالا برافرازد، نیزهی قلم برگیرد، سرودههای آهنگینش را چنان بر دلها نشاند که در یادها بمانند. در این سرزمینِ جنگهای بیپایان، تنها کتابخانهی امن، خاطرهی مردمان است. گویند سدهزار شاعر همزمان در ایران میزیند ولی تنها یکیست که از پس این کار سترگ برمیآید. تکشاعری، برای کوششی سپنتا. کسی که همهی واژگان را در شعرش بگنجاند! گنجینهای دور از دستبُرد آنان که در پی نابودیاش هستند. دربرگیرندهی داستان مردمانمان. پادشاهانمان. شهبانوانمان. کاخهامان. سرودها و بزمهایمان. جامهای پر از بادهمان. کبابهای بریانمان. باغهای مهتابیمان. کاروانهای کالاهای گرانبها: فرشهای ابریشمین, عنبر، مُشک، پیمانههای پر از الماس، پیمانههای پر از یاقوت، پیمانههای پر از مروارید. کوهستانمان. رودهامان. خاکمان. مرزهامان. نبردهامان. باروهای ویرانمان. درفشهای بر خاکافتادهمان. خونمان. که بودهایم. که بودهایم! فرهنگمان. خِرَدمان. گزینههامان. و واژگانمان. همهی واژگانمان. هزاران سال واژه، کاخی از واژگان که از باد و باران نیابد گزند! هر اندازه زمان ببرد.همه را در شعرش بگنجاند. همهی ایران را، در سُرودی یگانه. مشعلی خروشنده در سیاهی شب! پژواک بلند و پرطنین آوایی در تاریکی

684 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yandere!childhood-Friend!Fae x F!reader

You grew up with a mysterious but kind friend, but when you learn the truth about him you become distant from fear that the stories about his kind are true. Despite this you still loved him and gathered up courage to see him one last time before you left town. Did you really think he’d let you leave again? Fae are know to abduct humans to be servants, entertainment or even lovers.

Use of y/n

You grew up on the edge of a small town, in a house with little garden space, enough for a small bed of vegetables and some pretty flowers. However there was plenty of wild land stretching till the next town over, most of it a forest with healthy oak trees and soft mossy ground. Some land was a meadow that always seemed to be glow with a golden hue and and sprout the most beautiful flowers and large daisies even on the gloomy days. Other bits of land had desire paths stomped into the ground, some by your own doing and some by strangers, there was a creek that ran through the town and into the forest then over to the next town. You liked to sit there as a child with the daisies from the meadow and make daisy chains and to fashion into jewellery and crowns.

Your parents though you were a unusually quiet child, never really playing with other kids to long not because of a fault on yours or theirs part; were just happily reserved. So they didn’t bother you to much, believing you were just a thinker who enjoys their own pace, maybe you could grow to be a great poet. However while some of that true you were quieter for other reasons.

You were content with with the friend you had already, you understood early on that one close friend is better than all the friend in the world (maybe with slight persuasion of the friend). You in fact wasn’t slinking out the back door to the forest, promising you’d be home before tea time, to be alone but instead to meet your woodland friend.

You never connected the dots that the friend that you had grown up with was far from human until you began to read more widely, therefore learning about old tales and creatures like werewolf’s, witches and... fae ? Fae that sounded eerily similar to the now young teen in the forest, small horns that will sometimes poke from his hair that you shrugged off to be knotty hair or odd lighting, or the sharp black nails you’d assumed to be a odd fashion statement, or the odd colour of his eyes that you didn’t know was possible but blamed good genetics.

You freaked out a bit when you first realised that this boy wasn’t just a boy from the neighbouring town who enjoyed the forest but rather a fae who are usually depicted as evil, cunning and unpredictable. Maybe the stories are dramatic or just false, he’d never lay a rough hand on you before, rather he’d gently wind together plants and branches with your daisy chain to make you a more extravagant crown, and when he’d gently coax you over the creek holding your hand telling you what rocks to step on, or rub certain leaves on your cuts carefully that ease the pain almost crying himself from seeing you tear up.

You found it hard to believe he was anything like the stories, so after a few days to process the possibility you set out to meet him again. Hopeful that you were over exaggerating and he was just a human boy.

...

Fiddling with the hem of your shirt you walked deeper into the woods following the desire path you and your friend had made through the years, reaching the creek you stepped on the rocks he had guided you over and met the muddy bank on the other side with a squelch as your boots sunk a bit. You watched your footing as you trudged back onto the dry mossy ground, having made the clumsy mistake of falling into the mud many times before, you missed the boy dropping what he was doing and jumping down from a tree before rushing to you.

“Where were you?” The boy sighs frustrated, you jolted on edge from the sudden intrusion but relaxed when you saw it was just him. Although he looked angry as he stomped closer you could understand why “I’m sorry, I was just a bit busy” you chewed your lip, annoyed you hadn’t come up with a better excuse “I’m here now though” you said more like a question and forced a smiled, searching his face for forgiveness.

His eyes softened and a toothy grin crept onto his face “you’re excused” he half joked and your shoulders relaxed fully and almost forgot why you were here when he slipped his hand into yours. Looking down at your fingers intertwined with his soft fingers with talon like nails at the end you couldn’t hide the was your face dropped, he luckily wasn’t looking but rather guiding you to the meadow.

Walking beside him you were as silent as a church mouse, even treading carefully on the forest floor. You couldn’t help but be fearful of what he might be, taking a quiet breath you decided to walk along side him instead of being dragged behind. Now beside him you tried looking at his hair hoping you had made this all up in you’re head, but you saw no horns. Maybe you had just been dramatic so you tried to enjoy the walk with peace of mind.

Finally reaching the meadow you both collapsed into some taller grass that would make a padded place to lay, laying side by your side he talked about his week while looking up at the clouds and occasional butterflies. His parents always sounded strict and unloving, his brother sounded cruel and he had no friends from what you heard, maybe one day he could come for tea ‘mom would love him and maybe that would make him happier’ you thought; feeling guilty you had such a idillic live and him not so much.

Turning your head to face his with a sad smile as he ranted wanting to emphasise or comfort somehow but you found yourself become chocked up, he turned his head to and saw your sour face “but never mind that, I’m here with you and the forest that’s what makes me the most happy”. You however weren’t comforted not even hearing his attempt of lighting the mood, no you were sickly unsettled for another reason. Small but sharp horns that glimmered under the sun, now exposed slightly as his black curls fell oddly when he turned his head uncovering all the evidence you needed.

You jolted up so fast from the grass that your hair ribbon that wrapped around your head keeping stray stands from you face had unraveled from its lovingly tied bow and fell to the grass, the wind began picking up and everything around you became chaotic with the sound of the trees groaning and leaves shaking violently you stumbled back away from the grass that tickled your legs, every piece of grass now feeling like needles. He jumped to his feet just as fast or maybe quicker and grabbed your arm “what is it? Are you okay?” He pushed the hair from your face and tried pulling you closer, there they were again, the horns exposed from the wind. He saw you looking at them and his face dropped his mouth opened to protest but you didn’t give him a chance as you ripped your wrist from his hand and began running for the forest.

He followed closely yelling for you to come back, it started desperate then became frantic before turning demanding , you could have sworn the woods were becoming darker and branches were reaching to trip you. However you got to the creek and ran straight through instead of minding the stepping stones, it’s reached your knees but splashed higher. Climbing the muddy bank with your hands before you became steady enough to climb the rest on your feet you glanced back seeing him run up to the creek and stand there as you ran further away. You never saw him look so angry, fully convinced he was a malicious fae like the ones from the book you ran all the way home.

...

It might have been slightly naive to believe that he would still be in the woods after all these years but you needed closure, needed to walk through the woods and see there was never any threat, that afternoon you had accused a harmless boy of being something he’s not, something that didn’t exist, and the woods hadn’t grown a conscience and tried to trip you and consume you or left a story book monster decide your fate. You wanted to remember this place for what it was, a wild but joyful escape from ordinary life.

Memories change and you believed whole heartedly that everything you experienced that last afternoon in this place was all childish imagination from reading to many books. So it did come as a disturbing realisation as you faced a young man, probably your age with curly dark hair, bright unnatural eyes and shiny dark but sharp winding horns. “It’s okay y/n, just come here for me okay? Then I’ll explain it all to you” he spoke softly just like he used to when attempting to soothe your scrapes. He stood tall with a hand outstretched persuading you to cross the creek and for some reason you couldn’t take another step back but only forwards, it was like you were in a trance like state but still partially conscious.

Maybe if you and done your research, and learned that giving your name to a fae means bad news, you might have had a clue as to what was happing as to why you were compelled to cross the water and let him pull you into a desperate and crushing hug “it’s okay now my love, I’ll never let you leave like I foolishly had before, I’m so sorry” he pulled back a bit to hold your cold cheeks and look into your terrified eyes, his eyes softened from their frantic state as he pushed the stray stands from your face.

He then reached into his pocket and pulled out a ribbon, no it was your ribbon the one that unraveled from your hair as you fled the forest. He wrapped it under your hair and around your head, keeping your hair from your face he kissed your forehead. Had he been here the whole time waiting for you with your old flimsy ribbon? “We’re going to go home now okay?” He spoke slow and condescendingly, holding your face to look him in the eyes. You nodded slightly but stopped when you noticed the subconscious action, he was however satisfied with that and began dragging you into the woods with a hand in yours.

He had only walked about a minute before he heard your sobbing, turning quickly he saw your reluctance in your eyes and your mumbled pleas, but as much as his heart broke seeing you so upset he refused to let you out of the trance he had over you and risk you leaving for good. Instead he slowly picked you up and held you close encouraging you to hide your face from the cold bite of winter and cry into his shoulder.

He continued walking deeper into the woods without regret, he would have taken you kicking and screaming over his shoulder if he had to. Just this way he can rub your back, talk to you calmly and comfortably walk through the entryway to the world where most fae beings reside to take you to his home.

534 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) was an American philosopher, writer, naturalist, and political activist. He is best known for his book Walden, published in 1854, which recounts his two-year experiment living alone in a small cottage at Walden Pond two miles outside Concord, Massachusetts, and his essay On the Duty of Civil Disobedience written in 1849 shortly after his release from a Concord jail for non-payment of a poll tax.

Early Life & Transcendentalism

Thoreau was born in Concord, Massachusetts, on 12 July 1817. He studied at Harvard College and his worldview was shaped by transcendentalism, a belief in the divinity of human nature, which was not a coherent philosophy but an attitude or state of mind that inspired many American intellectuals who flourished between 1820 and 1860. The movement's foremost representative, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) had given the Phi Beta Kappa commencement address at Harvard with Thoreau in attendance. Other notable transcendentalists were Margaret Fuller, Louisa May Alcott, Walt Whitman, and Bronson Alcott. They were young Americans who had been born into the Unitarianism of New England. According to Perry Miller in his American Transcendentalists, they responded to the new literature of England and the continent "revolting" against the rationalism of Harvard College. Although Protestant, they turned against the Protestant ethic, choosing instead to cultivate the arts of leisure to avoid making money. To some, it was intense individualism, but to others, it was sympathy for the poor and oppressed. Morris wrote: "…the self-reliance and self-determination exalted by the transcendentalists gave to American writers a freedom that vitalized the first period of national letters." (600)

Thoreau graduated in 1837 without distinction and returned to Concord; he viewed Concord as a microcosm of the world. Instead of seeking employment like his fellow graduates, he chose instead to become an observer and interpreter, a "thinker of thoughts, a student of nature and of literature – half-scientist and half-poet" (Mead, 112) He tried teaching for a while and even land surveying. In Walden he wrote, "I did not teach for the good of my fellow man but simply for a livelihood, this was a failure" (65). He even worked for a time in his family's pencil factory. An occasional odd job provided him with enough money to be clothed and fed. He became friends with Emerson, who took him into his home (1841-43) and offered him advice on the craft of poetry and writing. Thoreau moved briefly to New York, living with Emerson's brother, to try to sell some of his essays and poems, but he was unsuccessful.

Continue reading...

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

A friend of mine and me come from Germany and we call him the „Sahneschnittchen mit Erdbeeren“, which literally translates to „cream slice with strawberries“.

Colloquially, a person who is attractive is also referred to as a cream slice. And the thing about the strawberries is self-explanatory, I think.

Germany - the land of poets and thinkers, or something like that.

#alastor#alastor the radio demon#hazbin alastor#hazbin hotel#radio demon#fanart#alastor fanart#alastor hazbin hotel#hazbin fandom#hazbin art#hazbin fanart#artwork#art

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rambling about Hass in Elisabeth for a REALLY long time. TL;DR - yeah, it is necessary as a song...

Because of the costumes and staging people often just see it as "the antisemitism song", which it is, strongly, but I think sometimes the wider context presented therein is ignored. Really, the song shows how antisemitism and hatred are fuelling and entangled with other movements!!

The nationalists in that song come from various groups and social classes, and identify as their enemies:

Socialists

Pacifists

Jewish writers

Jewish women

"Those who are not like us"

Crown prince Rudolf (because of his - historically strong - friendships and other positive associations with Jews)

The Habsburgs as a whole

Elisabeth and her Heinrich Heine (= a Jewish poet) monument project (which also attracted such strong criticism from German nationalists [Austrian Germans who were nationalists, not "Germans" in the modern sense] historically)

Hungary

The "barons" - so the nobility

The "slavic state"

The ongoing "betrayal of the people"

And to contrast, they identify as good:

Strength ("the strong wins, the weak fails", and also "strong leaders") and "purity"

"Unity"

Glory/splendour ("pracht")

Christian values

"Unified Germany", an alliance with Prussia and even an Anschluss (the joining of Austria and other "ethnically German" [so-called] lands to the German Reich. Hmm does anyone remember who also strove for and eventually implemented this... /s)

The conservative Wilhelm II as emperor (again, they want to join Austria into the German Reich)

So like. There is a glorification of all things "German" and of conservative values (religion) and reactionary power politics ("weakness" was and is by similar groups now considered to be a major flaw of liberalism and a liberal world order - in the song, pacifism and socialism are also connected to it), as exemplified by Wilhelm II's Germany specifically. To contrast, racial enemies ("non-Germans") threatening "racial purity" must be eliminated, with violence if necessary. And the Habsburg monarchy, being a multinational empire, is described as immoral and weak because of it being multinational (and the position of Slavs and Hungarians in politics and imperial administration).

The themes of "betraying the people" (Volksverrat) are especially interesting because the enemies of the nationalists as listed in the song, Jewish women, pacifists and socialists, were also the people blamed for German defeat in WW1 (the "stab in the back" at the home front myth). It's overall 19th and 20th century anti-establishment fascist imagery.

Ajdkkf I don't think I'm clearly making my argument but the song's key functions are:

To dispel the myth of the late 19th century being "the good old days", the glory days of Austria before the world wars somehow magically came to happen and ruined it. In fact, the songs shows that the developments leading to the world wars stem from politics and mass movements of hatred that developed alongside and gave power to & drew power from nationalism in the 19th century

To show the audience exactly what Rudolf is talking about in "Die Schatten werden Länger (reprise)". What is the "evil that is developing"? It's not Rudolf's personal petty wish for more power, or his angst about not being emperor yet, or some generic amorphous disdain for how FJ is reigning; it's not the lack of Hungarian independence either, for god's sake. I will die on this hill, if you cut Hass or replace it with conspiracy or whatever you can cut Rudolf as well, Elisabeth as a show is (in my opinion) a good portrayal of him precisely because it depicts him as a political thinker (in contrast to many depictions and post-Mayerling accounts which diminish that and just talk about Mayerling and his "immorality" - a talking point devised by the nationalists and antisemitists who hated him lol, liberal politics were connected to lack of morality) and someone who, unlike most of his contemporaries, saw that antisemitism, emphasis on "power" and realist power politics, exclusionary/hateful rhetoric and excess nationalism would lead to ruin. AND Hass also shows that he was hated by the German nationalists for this! As was his mother, for her sympathy to Heine...

To connect genuine popular dissatisfaction (from Milch - Hass is a reprise of Milch in terms of rhythm and the call-and-response structure where Lucheni talks to the crowd) with inequality, the lack of democracy and the excesses of royalty... to the rise and presentation of fascism as a "solution"

To show that 19th century nationalism was, in many ways, exclusionary, antisemitic, racist and "war-mongering", and that this rhetoric is old - not somehow magically appearing for WW2 and then disappearing again - and will time and again rise... and that it's everyone's responsibility to recognise it for what it is when it happens, if we are to have a reasonable, decent world to live in.

The framing of Hass sometimes confuses people I will never recover from that one post cancelling Elisabeth das musical for being antisemitic because Hass exists ajiddfkdllfgl what's next, it's pro-suicide and homophobic because a character technically dies from being gay? but to me it's rather clear that it's unsympathetic lol, with the whole doomsday atmosphere (no music, just footsteps/marching and drums and screaming, it's meant to be threatening), the way the ensemble harshly criticises the most sympathetically portrayed characters we have seen so far (Elisabeth and Rudolf) for things that seem petty and harmless (having Jewish friends), and the extremely direct comparison drawn to N*zism (to indicate what such a movement would develop to) in many stagings. I don't know how to say this but somehow I've always assumed that "H*tler and n*zism = evil" is EXTREMELY common knowledge and it mystifies me when people like. Think it should have been stated more clearly in the show. Like, the show is working off the assumption that you know what it is and that it's bad because of the millions and millions of people they killed............. this is EXTREMELY common knowledge in Europe, not least in Germany and Austria lol.

So um yeah akwkldlf, sorry for the ramble, I just feel like the song can be poorly understood and criticised on shaky ground sometimes. I mean, I am not Jewish and not equipped to talk about whether it's triggering or traumatising to watch especially with lived or family experience of antisemitic violence... But I think for non-Jewish people there is a huge responsibility to be aware and vigilant of antisemitism, historically and in the present, and sometimes it needs to be hammered home for people to understand...

By that last point I also somewhat mean... I think you don't "get" to be triggered by it if you're not Jewish but perhaps otherwise affected by politics of hatred. Of course I'm not emotions police lol, but many Jewish people have intergenerational trauma AND have to live with extremely similar antisemitic rhetoric and culture to this day, so there I understand criticisms - and there is also a discussion to be had about how and to what extent it is ok to use and display Jewish suffering as a device to educate non-Jewish people.

But anyway, to my original point. This is something I've seen people say and I just... if you're queer and it makes you uncomfortable to see Hass because modern n*zis hate you and it's traumatic, I mean, it's valid to feel uncomfortable and you can choose not to watch it personally to avoid being triggered, but you don't get to call for it to be erased from the show for "problematic content" or for "escapism" or to make you feel better. It is there because the destruction of the 19th century world, and Rudolf's and Elisabeth's suffering, is intrinsically tied to the rise of such hateful politics and without that being shown there is no show. You don't get to make it something it's not, this show is not ONLY an epic gothic romance with imaginary boyfriend, it's a commentary on past, present and future politics in that it shows the dangers of conservatism, antisemitism, racism and illiberalism. Calling for or supporting censorship, or state emphasis on militarism/"destroying the enemy", or advocating hatred, violence or oppression against any group based on ethnicity, religion, race, political views, etc. are all political stances held by and propagated by various people today in various political contexts. And you are not immune to antisemitism or reactionary nationalism if you're queer or whatever, so you have the constant responsibility to think critically about your worldview and your politics!!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

@inklings-challenge here is my contribution to day 19's prompt, "amateur."

This is an excerpt from a Coregean novel, The Amateur Princess, as described here. It's not the brilliant extravaganza I had in my head, unfortunately (I tried something more detailed but it was too ambitious for my current capabilities), but hopefully it gets the idea across.

Loriston society seldom had anything notable enough to warrant the rapt attention of throngs of ennui-stricken aristocrats. They were already accustomed to the ways of the Coregean royal family. They yawned over the most sensitive of poets, whispered through the performances of musicians whose work was renowned on the Continent, and favored the world’s greatest thinkers with only a half-hearted “how do you do?” It required a truly exceptional human being to command the regard of these jaded creatures, and at last society had found such a one: the exiled Princess Grayce of the tiny nation of Anatavia, somewhere in the southeastern mountains of the Continent. No one quite knew where to locate this land on a map. But one could locate Princess Grayce any evening at the residence of the Duchess of Ampnowle, surrounded by admirers. For not only was Princess Grayce amiable and beautiful—golden-haired and blue-eyed, with a foreign, high-cheekboned face—but she also told the most engaging tales.

That night a crowd had gathered around, begging for an account of how she alone of her family had escaped from the turmoil that deposed her father the king and brought a usurper to the throne.

“It really is quite painful to recall it, I am afraid,” said Her Royal Highness in a tremulous voice. She spoke excellent Coregean with hardly any accent, for it was one of the languages of the court in her homeland. “Surely you can imagine what a heartbreaking thing it is to lose everything you love in one night.”

The nobility, none of whom had lost anything more devastating than a small fortune at the gambling table, groaned in exquisite sympathy.

Princess Grayce acknowledged their kindness with the slightest smile and a regal little nod.

“For your sakes,” she said, “I shall do my best.”

And she did. She related an account full of palace intrigue, concealed crown jewels, faithful retainers, a daring plan for escape, and a devastating betrayal, resulting in the Princess Grayce getting separated from her mother, brother, and sister while en route to safety in neighbouring Ivica, only to hear upon arrival of the tragic assassination of her father at the hands of the conquering King Jellick’s supporters, while the rest of the royal family remained missing.

Amid the cries and gasps of her audience, Princess Grayce had managed to maintain most of her composure, but it was at this point that Her Royal Highness’s eyes filled with glittering tears that trickled down her stately nose like fallen diamonds. For a time, she could hardly speak. The Duchess placed a gloved hand on hers and patted it with the tenderness of a mother. Not a soul in that room was unmoved by the sight of the Princess Grayce as her delicate form shook with sobs.

As she was starting to recover, a gentleman asked, “Where did you go next?”

She dabbed at her face with a lace-edged handkerchief. “I had nothing left but a locket that my parents had given me for my sixteenth birthday. I sold it and bought a train ticket to Vischland, which was as far away from Jellick’s influence as I could afford. From there, I earned my passage to Corege as a lady’s companion until I reached Loriston and made the acquaintance of the dear Duchess.” She smiled a feeble little smile at her hostess.

“But why,” persisted the gentleman, “did you not go to Ivica as you originally intended? Your elder sister is their queen; surely she would have taken you in.”

Princess Grayce said nothing. She clenched the arms of her chair and went white, then red.

When at last she spoke, it was with a note of reproach. “Do you not,” she said, “recall that Ivica itself is under threat? A party not unlike Jellick’s is gaining power, and my brother-in-law King Kostandin has pleaded with your own king for aid. How could I enter that country without causing greater problems for my dear Viera? I wouldn’t wish what I suffered on anyone, least of all my own sister. For her to accept me into her home now would be to acknowledge and give credence to…what happened in Anatavia, which would only send a message that if one deposition can be managed, so can another. I couldn’t go there.”

“Is that why you haven’t presented yourself at Rhosemore…Your Royal Highness?” asked the gentleman.

“Your gracious king,” said Princess Grayce, “has not yet invited me. Whenever he does so, I shall be delighted to accept. But at the moment I cannot intrude upon his hospitality. The generosity of the Duchess has already been more than I could have hoped for.” She went misty-eyed again but collected herself. “And if there are no further questions tonight…?”

Even the inquisitive gentleman had nothing further to add.

Princess Grayce rose and curtsied in the elaborate Anatavian fashion. “In that case, I shall retire for the evening, but I would be delighted to meet with you all again soon. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.”

And with a regal wave, she swept out of the room in a cloud of white lace.

#

Away in the Duchess’s finest guest bedroom, a golden-haired young lady had put aside her lace finery in exchange for a silken wrapper and had dismissed her maid (loaned to her by her boundlessly munificent hostess) for the evening. She sat for a time at her dressing table, studying her reflection in the glass in various attitudes, ending with disgust.

“Who does he think he is?” she muttered in tones quite unlike the silvery ones heard in the Duchess’s drawing room. “Thank heaven I remembered.”

Within the drawer of the dressing table lay the evening newspaper, folded as small as possible. Snatching this up, she strode near the fire and paced in front of it for a time, reading every article of world news as religiously as a university student “cramming” for an “exam.” Unlike a diligent student, however, she took no notes. When the final article had been pored over, the newspaper fluttered onto the grate and began to darken and shrivel into ashes.

“I’ll be ready for him tomorrow,” vowed Tresta Gild.

Nature had granted her the gift of total recall of anything she read, a talent which had served her well in her years as a confidence woman. From the time the identity of Princess Grayce had fallen into her lap, her knowledge of Anatavia and its former royal family, gleaned from every book, newspaper, or magazine on which she could get her hands, had increased until she had nearly encyclopedic knowledge of the subject—inasmuch as was written and published.

And much of the life of Princess Grayce, whatever had truly become of her, remained locked away in the memories of those close to her.

Cresta began to suspect that she had just met one of them.

#the chesterton challenge#The Blackberry Bushes#The Blackberry Bushes worldbuilding#my writing#The Amateur Princess#I think this is a story better suited to the capabilities of fictionadventurer than to me!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

more punch out headcanons

- I imagine every circuit has a person who tries to be friends or atleast on good terms w/ everyone. For the minor circuit it's Disco Kid, for the major circuit it's Bear Hugger, and for the world circuit it's Soda Popinski.

- Disco kid's very good at figure skating. He’s currently teaching SMM how to do it, with mixed results. Macho, like Doc has commented, can spin very well, but his landings leave a lot to be desired. Macho freaks out every time he does, afraid he'll ruin his pearly whites.

- So-called free thinkers (Glass Joe) when la Marseille starts playing

- SMM was born into a rich family. As a kid, he was able to practice any hobby he wanted to. Boxing was one he happened to have the most talent for. Like Macho Man, Disco Kid comes from riches as well. Unlike Macho man, however, Disco is as nice as can be, but doesn't take boxing as seriously.

- King hippo being 6 plus foot atleast + big n muscular as hell + resting bitch face + deep voice = accidentally intimidates people all the time. The funny thing is, however, he's actually the runt of his family. His ma n pop are 7 foot and 7'5 foot respectively

- The reason poor Von Kaiser is as traumatized as he is, is due to severe bullying at school because of his tics. that’s what happened in the slideshow; his trauma triggered from kids laughing at him.

- Von Kaiser 🤝 Piston Hondo

being bullied as kids over their tics

- King Hippo? More like King AUTISM

- Bear Hugger knows a lot about survival in the wild, and loves camping out. Once, he invited the whole WVBA on a big camping trip. Big mistake, several people (namely SMM, Aran Ryan and Don Flamenco) littered, used a ton of ozone unfriendly sprays to get rid of bugs and were either disgusted by (SMM and Don flamenco) or pestering (Aran Ryan) the animals. As a result of this fiasco, he only invites trusted people on his camping trips anymore.

- Piston Honda's dad is a poet, and taught his son all about all kinds of japanese proverbs, which is why Honda's always reciting them during intermissions.

- SMM’s crowd, when they’re not booing him or throwing produce at him, sometimes sing the song ‘’Macho Man’’ by the Village People at him. Why? Because it's funny and they're doing it ironically. SMM is completely unaware of this though; he thinks they're admiring him.

- SMM often hosts ''Best Circuit'' parties for the world circuit. Bald Bull and Mr. Sandman will stand in the corner awkwardly watching the others dance, while Aran and Soda absolutely KILL it on the dance floor. Aran will also often embarrass Macho in front of ladies he's trying to flirt with.

#punch out#disco kid#super macho man#von kaiser#king hippo#bear hugger#piston hondo#piston honda#aran ryan#soda popinski#bald bull#mr. sandman#since u guys enjoyed my other ones sm heres some more thoughts i have#i just rly love these funky little boxers :D

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

[T]hose maligning [Jewish] non- or anti-Zionists are not saying they are not Jews; it’s even worse than that. These critics argue that those who diverge from the Zionist platform are essentially anti-Jews, or counter-Jews, because for these enforcers, Zionism – meaning support for the state of Israel as a Jewish state – has become a more essential marker of Jewish identity than Jewish practice, or any other criteria.

[...]

[W]hat happens if we take the argument that anti-Zionism is antithetical to Jewishness seriously – in fact, more seriously than some of these Zionist or pro-Israel enforcers do? The problem with this argument is that it’s easily contradicted by Zionist history itself. Some well-known early Zionists would have enthusiastically agreed that they themselves were out of step with any notion of normative Jewishness.

Take, for example, the radical Zionist Mikhah Yosef Berdyczewski who identified himself as the “last Jew and the first Hebrew.” Or the Canaanites, a small but influential artistic and ideological movement in Palestine and then Israel in the 1940s and ’50s, founded by poet Yonatan Ratosh, who openly repudiated Judaism and Jewishness in favor of a new Hebrew nation – one that was explicitly not “Jewish.” To those familiar with the history of Zionism, it is well-known that many of these early Zionist ideologues viewed Zionism as the replacement for Judaism – not a complement or extension of it, nor a faction within it. Zionism as a political movement was, in effect, Judaism’s fulfillment, in the sense of completion; returning to the land of Israel was meant to make the Jewish religion superfluous. Even the most conventional Zionists of that era were devoted to the creation of a Hebrew – not necessarily Jewish – nation.

Debates about Judaism as a religion, and Jewishness as an identity, were central to early Zionist thought. For example, the foundational Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’Am argued for cultural Zionism, the idea that Israel should become a “spiritual center” for world Jewry, in parallel with the continued Jewish diaspora. On the other hand, one of the tenets of early Zionism, exemplified in its extreme by Berdyczewski and the Canaanite movement, but present in most Zionist ideology, was the “negation of exile” (or the “negation of the diaspora”) – the erasure of exilic existence (and its supposed ills) through the foundation of a state in the Jewish homeland. As one can see, the relationship of early Zionists to Judaism was often quite tortured and complex.

Today’s “heresy hunting” ignores, dismisses, or perhaps is simply unaware of the utterly radical, and revolutionary, nature of Zionism itself. It elides how Zionism often claimed to replace Judaism, which some viewed derisively as essentially a product of exile. It ignores recent Jewish history and culture, before most of American Jewry had become Zionist, and before statist Zionism was the dominant form of the Jewish national project. These simplistic thinkers who attack non-Zionist and anti-Zionist Jews don’t realize that the Zionism they take as coextensive with Judaism today was, for many of its architects, meant to be the alternative to Judaism.

On Jews, un-Jews, and anti-Jews from The Necessity of Exile: Essays From A Distance by Shaul Magid

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anon [Louis de Champcenetz?], The War of the Districts, or the Flight of Marat, Heroi-comical poem in three cantos (Paris: n.p., July? 1790)

Part 2 (of 5)

Epigraph:[1]

“Fert animus causas novarum [tantarum] expromere rerum/

Ridiculumque [Immensumque] aperitur opus, quid in arma furentem/

Impulerit populum, quid pacem excusserit urbi [orbi]?” Lucan.[2]

Preface one can read:

It is said that the great Homer did not disdain to write a heroic-comic poem; Batrachomyomachia, that is to say, the war of the frogs and the rats.[3] The districts will perhaps be upset that we presumed to compare them with such creatures; but poetry has its licence.

TASSONI, in Italy, wrote the poem Secchia rapita, that is, The stolen bucket.[4] Voltaire said of him:

“O TASSONI! In your long composition,

So lavish with verse yet sparing in force;

Shall I, in my strange fate’s condition,

Implore from your moody languors, recourse?”

We have endeavoured in this trifle to do the opposite of the Italian poet, & the districts will not hesitate to say that we have failed; which will be generous enough. [5]

BOILEAU wrote the Lutrin; POPE, The Rape of the Lock, & VOLTAIRE, The Civil War of Geneva. We took a lower tone than all these gentlemen. The verses of seven syllables run like prose, the rhyme returns constantly, & when we interweave it with art, it produces a pleasant effect. A poem of this kind is only valuable for its display of imagination & ease, which is grace [state?] of mind, as VOLTAIRE often used to say. In poetry, it is very difficult to be effortless. For the rest, we leave it up to the gentlemen of the districts to judge whether our talent has surpassed our intentions. Although this poem is comic, we would still prefer it made them cry rather than to see them laugh; which is horrible to admit, but we must not be hypocrites.

All Europe knows the adventure of the famous MARAT, & the arsenal that was deployed for and against him. So we will say no more about it: the poem will tell the rest. It should have appeared long ago if the plot of COUNTER-REVOLUTION had not delayed it.[6] We wished to land 50 well-armed ships of the line at night, between the Pont-Neuf and the Pont-Royal, and 60 thousand Croats by balloon on the plain of Grenelle. All of this kept us very busy, and for the success of such a bold project, we would have sacrificed this joke; but we can no longer do so with a clear conscience. We hope that this confession will reconcile our poem to messieurs [MM.] NECKER, BAILLY, LA FAYETTE, & the gentlemen of THE DISTRICTS, who fear the stings of ridicule less than the wounds of sabres & cannons. It is a good habit & a laudable caution. [7]

First Canto:

You who once sang of the fights

between the frogs & the rats,

On the banks of the Scamander;

Come, hasten to defend: [8]

Muse! Lend me your voice

I shall recount the exploits,

Of this formidable district

Where the valiant bourgeois,

So firmly upheld the rights

Of an incomparable Genius.[9]

Marat (1), this profound thinker

With his daily pen,

Wearied the gentle mood

Of this young Dictator, [3]

Whose Parisian glory

Is worth as much, upon my honour,

As his American glory.

NECKER the calculator,

Tireless borrower,

Found in him a censor.

BAILLY, this supreme mayor,

Had him always on his hands;

He cried out for condemnation,

And found no consolation.

These three famous personages,

Annoyed by so much outrage,

Gathered together one day:

Then, without further delay,

NECKER said to la FAYETTE;

“We must make a hasty move.

MARAT, this ugly writer,

Pours his venom upon us;

He’s a noisy rattlesnake.

He makes me look rather dim;

Already the rumours are spreading;

So in order to avoid that

We must finally arrest him”.

The Mayor adds his support

To the Genevan’s speech;

And with a troubled soul,

Complains to the young hero,

That MARAT, this king of fools,

Insults his livery and luxury

At every opportunity. [6]

“Drawing unjustified disdain,

Should I, without fanfare,

Wander through Paris

Like some minor part?

Luxury is essential for me

To dazzle the masses with pageantry.

So, without too much thought,

You must resort to locking

Up this malicious hack.

All things considered,

And the hero prepared,

He tells them in a proud voice:

“Gentlemen, I agree to all;

Your opinions are very sound.

MARAT, ceaselessly devotes himself,

To directing his criticisms,

Against our natural talents;

I will arm all my fighters,

Abduct this caustic writer,

And tomorrow he’s in jail.

Then the Trio kiss cheeks,

While holding each other’s hand,

Saying, ‘Until tomorrow’.

They are overcome with bliss.

Alas! How fickle man is!

What frivolous hope!

Their words make them happy;

Tomorrow, fate may turn.

BAILLY, preceded by a page

In his pompous attire,

Returns home briskly;

NECKER goes more slowly.

Like DUBOIS, his colleague,

LA FAYETTE proudly,

Mounts his white horse:

He is followed from behind,

By GOUVION & DUMAS (2),

And by four or five soldiers.

But this swift Goddess

Who ceaselessly flies without pause,

To warn humankind

Of good & bad designs;

Enters this church

where FRANCIS OF ASSISI reigns,

And addresses the brave warriors

of the Cordeliers District:

“BAILLY, NECKER & LA FAYETTE,

By a terrible pact,

Wish to abduct MARAT;

Tomorrow they intend

To execute this brilliant feat;

Fear everything, I repeat,

From this proud TRIUMVIRATE.

This having been said, the Messenger

Vanishes like a bolt of lightning,

Her feet tracing a graceful

Thread of light across the air.

The bourgeois quite dazzled, [8]

Are no less dumbfounded.

D’ANTON (3), immediately begins;

D’ANTON, firm president,

Even prouder than ARTABAN: [10]

“Why then this great silence?

Are we then cowards?

We have battalions.

MARAT, this patron Saint

Of the surrounding districts,

Will he be captured like some corsair,

For handing out lessons

To half-baked despots

Whom we no longer require?

What happens to liberty

If this crime is committed?

The battle is necessary;

His paper is good & fine,

It's a true PALLADIUM;

If he is forced to be quiet,

Gentlemen, it's the end of ILION. [11]

This display of erudition

Impresses the crowd;

They cannot decide:

When, making his move,

Mr FABRE D'EGLANTINE (4),

Adjusting his ugly face,

Rises up on his heels.

Acting all important,

Like a pompous French pedant.

Once, a lousy actor

From the regions & perfect scoundrel,

Who prides himself on doggerel;

He wrote a comic play,

Where, in a bombastic role,

Poor MOLÉ went quite hoarse.

Let's leave his portrait there,

And talk about the meeting.

“The speech of the great d’ANTON

Proves he is no coward”,

he says, with confidence,

“Here is the consequence:

If tomorrow we fight,

We’ll lose the battle.

I cannot deny

That MARAT is a genius,

Well-known across Europe;

But for one person,

despite the solace of philosophy,

Should we cripple ourselves,

And see a district defeated?

As for me, I must confess,

And I intend to be praised for it,

I cherish peace above all;

And if some ARISTOCRAT

Were to push me to blows,

I would be a good DEMOCRAT,

And would sue him.

With pen and ink,

No harm is done; [10]

But this gunpowder,

And these metal bullets,

All do such devilish harm,

And lead a miserable soul

Straight to hospital:

I know this commonplace.

Gentlemen, here is justice;

MARAT from us is requested,

Their wish must be respected;

(Let one perish for all)".

At these words, the great d’ANTON

Says to him: ‘THERSITES-faced, [12]

Your morality is poisonous;

Leave the church now,

Or fear the truncheon blows.

Gentlemen, can you believe this traitor?

Will such a revered district

Be dishonoured?

No, you fear it too much to be so;

I know your hearts well;

Come, we will be Victorious’.

NAUDET, famous captain (5),

Who one often sees on stage,

Winning countless battles,

With his mighty arm,

Assures them of victory;

Every bourgeois, convinced,

By his determined tone,

Was obliged to believe him. [11]

Father GOD, Cordelier (6),

Whose countenance is bellicose,

Tells them, in a tipsy voice,

While rolling up his sleeve:

“Having had breakfast,

I said my Sunday mass:

But I swear on my cord,

Not to touch another

Drop of communion wine,

Unless SAINT-FRANÇOIS, my patron,

For whom I preached a sermon,

Lends his assistance to

The followers of OBSERVANCE.

Gentlemen, we will help you,

Our fathers are good fellows

Once they have filled their bellies;

Victory will be ours”.

This somewhat bacchic speech,

Yet also quite heroic,

Lifts bourgeois hearts;

They immediately take a vote;

The warrior party prevails.

And this brave cohort

Disperses in a moment,

To arm themselves. [12]

Notes to the First Canto [10-14]:

(1) MARAT, former physician. Unlike PERRAUT, who became a good architect after leaving his first profession; MARAT did not become a good writer. Opium was his universal remedy when he practised medicine, & he lavishes it upon his readers with the same abundance. This is the power of habit; as Pascal is supposed to have said (that it is a first nature). It is he who writes L'AMI DU PEUPLE, a newspaper that devours all others, like the serpent of Aaron.[13]

We composed the following quatrain at a time when the districts defended themselves so well: it is addressed to the Parisians.

Your noble courage cannot be praised enough,

And you will always be lauded by GARAT;

Conquered by you, the King groans in bondage,

And you have saved MARAT.

(2) Messieurs GOUVION & DUMAS. The former is M. de LA FAYETTE’s henchman. He advises him, he leads him, he pushes him. He is a cunning, false, cold, insinuating, intriguing, impudent man. His friends find in him only the vice of drunkenness; the indifferent are not so indulgent. The other has almost the same faults; scælus; quos inquinat, æquat; but he does not get drunk.[14] This man, whose talents are ambiguous, and who, from an obscure, even dubious, birth, has risen to the rank of colonel, & who had replaced M. de GUIBERT in the council of war, had nothing more urgent than to throw himself into the revolution, mistaking ingratitude for patriotism.

(3) D'ANTON, lawyer for the Conseil du Roi. Zealous DEMAGOGUE, with more character than wit, & who believes MARAT to be a great genius. He was president of the Cordeliers district at the time of the famous adventure.

(4) There is nothing left to say about FABRE D'EGLANTINE in the poem. He is the author of the sequel to Le Misanthrope; a work lacking style, filled with declamations & bad taste. The character of the Misanthrope has some charm, but is exaggerated, likewise Philinte. MOLÉ prefers this comedy to that of MOLIÈRE. Trahit sua quemque voluptas [Each to their own]. [15]

(5) NAUDET, former sergeant in the French Guards; he is a gentleman, whose talent does not bother anyone, & who has nothing to reproach himself for except the clothes he wears. He is a captain in the National Guard.

(6) Father GOD served as a model for VOLTAIRE, for his Grisbourdon.[16] The praise is not slight.

[1] La Guerre des Districts, ou la Fuite de Marat, Poème héroi-comique, en trois chants, BnF (Rés), Receuil de Facéties en vers (2), p.3128. On the titlepage (after the Preface), ‘Fuite’ is changed to ‘Enlèvement’.

[2] “My mind moves me to set forth the causes of these new [great] events/And ridiculous [huge] is the task before me to show what cause/Drove peace from the city [world] and forced a frenzied nation to take up arms?", from Lucan, Pharsalia [aka De Bello Civil], bk1, p.66 (Loeb). Lucan’s epic poem tackled the civil war between Caesar and Pompey. Here, the poem’s author has subtly adapted the epigraph for its new Parisian context; the original Latin is indicated inside the brackets. Lucan’s poem had also been invoked during the 16th-Century French Wars of Religion, when its description of events as sacrilegious manifestations of insanity, struck a chord.

[3] This parody of Homer’s The Iliad is usually translated into English as ‘The battle of the frogs and the mice’. Despite ‘winning’, the ‘mice’ are driven off by Zeus with a Deus ex machina intervention of a crack troop of crabs. It is now generally ascribed to Pigres of Hallicarnassus rather than Homer.

[4] Allessandro Tassoni (1565-1635) was famous for this mock-epic poem, also known as The Rape of the Pail.

[5] It is unclear whether the ‘We’ [nous] here, refers to a singular or plural ‘we’, and thus a singular or double authorship.

[6] A clever double meaning and possible reference to Suleau’s Picardy adventure for which he was arrested, as mentioned in the introduction.

[7] The poem being parodied featured divine intervention, grandiose speeches, heroic genealogies and paradeigma. It is intended to be read aloud.

[8] A river in Troy that features in The Iliad.

[9] [CJ:you don’t actually say what a district is and when the change to sections happened (June 1790).]

[10] The expression, “Fier comme Artaban” comes from a character in Gauthier de la Calpranède’s historical novel, Cleopatra (1657). Its English equivalent might be ‘proud as a peacock’.

[11] Archaic name for Troy.

[12] A foolish, hunched character from Homer’s Iliad.

[13] This footnote acknowledges the growing influence of Marat’s paper. When Moses and Aaron appeared before the Pharaoh, Aaron turned his rod into a serpent to swallow the ‘serpent’ rods of Pharaoh’s sorcerers (Exodus 7:10-12).

[14] ‘Crime; those it contaminates, it makes equal’.

[15] Francois-Réné Molé (xx-xx) was an actor in the Comédie-Francaise.

[16] A character in La Pucelle. “Father God” appears to be an allusion to Danton.

#la fuite de Marat#Jean-Paul Marat#French Revolution#poetry#counter-revolutionary#General Lafayette#libel#Jacques Necker#Georges Danton#marat

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think a lot about water, in this time. […] Whisperings of rivers that greet the sea. The currents [...]. The saltiness of estuaries that ebb through the roots of mangroves. Waters that return to themselves, always different, streaming off, merging back, sinking in. […]

To refuse is usually understood as being-against: the Bartleby-an preference not to; refusal as strike, occupation, boycott, cancellation, retaliation, resistance, from passive evasions to spectacles of revolution. The no of refusal is a mode of survival: an impenetrable boundary, silent or shouted. It is a refusal to be killed or to succumb: the Indigenous refusal of colonial recognition, the Black refusal of white erasure and enclosure. But before refusal as dialectic, in the now unused meaning found in common Latin, refusal also meant to give back, to restore, to return.

Derived from re-, “back”, and fundere-, “to pour”, this meaning fell out of use, likely because conversational Latin was not transcribed but comprised of evolving and diverging dialects […]. The addition of refusal as return – a definition always already slipping away, consigned to hearsay and archival traces – disarranges refusal’s march towards the future [...]. An understanding of refusal as return [...] unsettles narratives of resistance that are framed only in opposition. [...] The idea of pouring back or watering expands the conceptualisation of refusal as an act of liberation. Refusal as return swells refusal’s imagination-otherwise [...]. Vast ecosystems flattened for plantations [...], raw minerals pulled from the ground and sea for the building of [...] war [...]. The ordering of land into resource [...] has been arbitrated by those who profit [...]. Return disavows final consolidation [...]. On the contrary, the past illuminates the limitations of capitalist time and the fallibility of colonial history. Return is a reckoning with what is presumed to be universal. [...]

As well as the being-against of refusal, return allows for a being-with, a sitting-with. [...] A return is an invitation to humble oneself to another approach. Being-with requires a pause from which to imagine otherwise, in all of its vastness and uncertainty. It is a moment between, where one is asked to hold onto many possibilities at once.

To be-with [...] needs a disposition of attentiveness, [...] an attunement, following I-Kiribati poet and thinker Teweiariki Teaero when he says, “two ears, one mouth, don’t talk too much. Learn to listen more,” or Fijian academic Unaisi Nabobo-Baba when she speaks of silence as a “pedagogy of deep engagement”. [...]

The immensity of the loss of people and ecologies to capitalist brutalities exceeds what we can comprehend. But as Indigenous and Black Studies scholars, artists, and ecologists show, so do the myriad, and insuppressible flourishings and alliances, the joyfulness and love, the lives lived otherways. Attunement leads us to the gaps and silences and soundings that run through everything, that connect the earth and all who live and die.

---

Text by: AM Kanngieser. “To undo nature; on refusal as return.” transmediale. 2021.

#tidalectics#carceral geography#archipelagic thinking#sacrifice zones and extractivism etc#caribbean#multispecies

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listen to our second single on Spotify here

"Richter und Henker" deals with communication and behavior, especially on social media these days, where dissenters get defamed: 'If you don't support my opinion, you're against me. Then you are stupid and I hate and insult you and won't listen to you anymore'. This can easily lead to a loss of objective discussions, which are crucial in a democracy. Irresponsible populists sow hatred and discontent in order to make political and monetary profit from it. Germany, the so-called land of poets and thinkers, is in danger of becoming the land of judges and executioners [ger: Richter und Henker] - and we've been through that before... In the video for the song, we perform in an old, run-down mansion, which symbolizes the impending decay of society. In the calm interlude, reason - personified by our young performer - is put up against the wall by an execution squad.

#napalmrecords #neuedeutschehärte #witzkivisions

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weiße Rose, Leaflet #2 [Summer 1942] [Weiße Rose Stiftung e.V., München. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.]

The Second Leaflet

«It is impossible to engage in intellectual discourse with National Socialism because it is not an intellectually defensible program. It is false to speak of a National Socialist philosophy, for if there were such an entity, one would have to try by means of analysis and discussion either to prove its validity or to combat it. In actuality, however, we face a totally different situation. At its very inception this movement depended on the deception and betrayal of one's fellow man; even at that time it was inwardly corrupt and could support itself only by constant lies. After all, Hitler states in an early edition of "his" book (a book written in the worst German I have ever read, in spite of the fact that it has been elevated to the position of the Bible in this nation of poets and thinkers): "It is unbelievable, to what extent one must betray a people in order to rule it." If at the start this cancerous growth in the nation was not particularly noticeable, it was only because there were still enough forces at work that operated for the good, so that it was kept under control. As it grew larger, however, and finally in an ultimate spurt of growth attained ruling power, the tumor broke open, as it were, and infected the whole body. The greater part of its former opponents went into hiding. The German intellectuals fled to their cellars, there, like plants struggling in the dark, away from light and sun, gradually to choke to death. Now the end is at hand. Now it is our task to find one another again, to spread information from person to person, to keep a steady purpose, and to allow ourselves no rest until the last man is persuaded of the urgent need of his struggle against this system. When thus a wave of unrest goes through the land, when "it is in the air," when many join the cause, then in a great final effort this system can be shaken off. After all, an end in terror is preferable to terror without end.

We are not in a position to draw up a final judgment about the meaning of our history. But if this catastrophe can be used to further the public welfare, it will be only by virtue of the fact that we are cleansed by suffering; that we yearn for the light in the midst of deepest night, summon our strength, and finally help in shaking off the yoke which weighs on our world.

We do not want to discuss here the question of the Jews, nor do we want in this leaflet to compose a defense or apology. No, only by way of example do we want to cite the fact that since the conquest of Poland three hundred thousand Jews have been murdered in this country in the most bestial way. Here we see the most frightful crime against human dignity, a crime that is unparalleled in the whole of history. For Jews, too, are human beings—no matter what position we take with respect to the Jewish question—and a crime of this dimension has been perpetrated against human beings. Someone may say that the Jews deserved their fate. This assertion would be a monstrous impertinence; but let us assume that someone said this—what position has he then taken toward the fact that the entire Polish aristocratic youth is being annihilated? (May God grant that this program has not fully achieved its aim as yet!) All male offspring of the houses of the nobility between the ages of fifteen and twenty were transported to concentration camps in Germany and sentenced to forced labor, and all girls of this age group were sent to Norway, into the bordellos of the SS! Why tell you these things, since you are fully aware of them—or if not of these, then of other equally grave crimes committed by this frightful sub-humanity? Because here we touch on a problem which involves us deeply and forces us all to take thought. Why do the German people behave so apathetically in the face of all these abominable crimes, crimes so unworthy of the human race? Hardly anyone thinks about that. It is accepted as fact and put out of mind. The German people slumber on in their dull, stupid sleep and encourage these fascist criminals; they give them the opportunity to carry on their depredations; and of course they do so. Is this a sign that the Germans are brutalized in their simplest human feelings, that no chord within them cries out at the sight of such deeds, that they have sunk into a fatal consciencelessness from which they will never, never awake? It seems to be so, and will certainly be so, if the German does not at last start up out of his stupor, if he does not protest wherever and whenever he can against this clique of criminals, if he shows no sympathy for these hundreds of thousands of victims. He must evidence not only sympathy; no, much more: a sense of complicity in guilt. For through his apathetic behavior he gives these evil men the opportunity to act as they do; he tolerates this "government" which has taken upon itself such an infinitely great burden of guilt; indeed, he himself is to blame for the fact that it came about at all! Each man wants to be exonerated of a guilt of this kind, each one continues on his way with the most placid, the calmest conscience. But he cannot be exonerated; he is guilty, guilty, guilty! It is not too late, however, to do away with this most reprehensible of all miscarriages of government, so as to avoid being burdened with even greater guilt. Now, when in recent years our eyes have been opened, when we know exactly who our adversary is, it is high time to root out this brown horde. Up until the outbreak of the war the larger part of the German people was blinded; the Nazis did not show themselves in their true aspect. But now, now that we have recognized them for what they are, it must be the sole and first duty, the holiest duty of every German to destroy these beasts.

If the people are barely aware that the government exists, they are happy. When the government is felt to be oppressive, they are broken.

Good fortune, alas! builds itself upon misery. Good

fortune, alas! is the mask of misery. What will come of

this? We cannot foresee the end. Order is upset and

turns to disorder, good becomes evil. The people are

confused. Is it not so, day in, day out, from the beginning?

The wise man is therefore angular, though he does

not injure others; he has sharp corners, though he

does not harm; he is upright but not gruff. He is clearminded,

but he does not try to be brilliant.

LAO-TZU

Whoever undertakes to rule the kingdom and to

shape it according to his whim—I foresee that he will

fail to reach his goal. That is all.

The kingdom is a living being. It cannot be constructed,

in truth! He who tries to manipulate it will

spoil it, he who tries to put it under his power will lose

it.

Therefore: Some creatures go out in front, others

follow, some have warm breath, others cold, some are

strong, some weak, some attain abundance, others succumb.

The wise man will accordingly forswear excess, he

will avoid arrogance and not overreach.

LAO-TZU

Please make as many copies as possible of this leaflet

and distribute them.»

– Inge Scholl, (1952), The White Rose. Munich 1942-1943, With an Introduction by Dorothee Sölle, Translated from the German by Arthur R. Schultz, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 1983, pp. 77-80

#flyer#pamphlet#book#weiße rose#hans scholl#alexander schmorell#christoph probst#sophie scholl#willi graf#kurt huber#weiße rose stiftung#united states holocaust memorial museum#inge scholl#dorothee sölle#arthur r. schultz#wesleyan university press#1940s#1950s#1980s

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

🔥

the dark ages were actually dark.

i've noticed a lot of people trying to downplay the dark ages and say that it was actually flourishing or some shit. now, to be clear, i'm talking about the time period immediately following the collapse of the western roman empire and mainly focusing on the lands within that former empire.

life got worse by almost every metric. people became poorer, had lower wages, less freedom, infrastructure fell into disrepair, medical expertise and sanitation declined, literacy declined, etc. worst of all, there was a dearth of culture in general. great thinkers, poets, artists, etc, were hard to come by. if you disagree, name me 5 great philosophers or poets from dark ages western europe. you can't.

now i'll admit it probably wasn't as bad as popular culture suggests. but still it was probably pretty bad. at least, it was worse than it was before.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

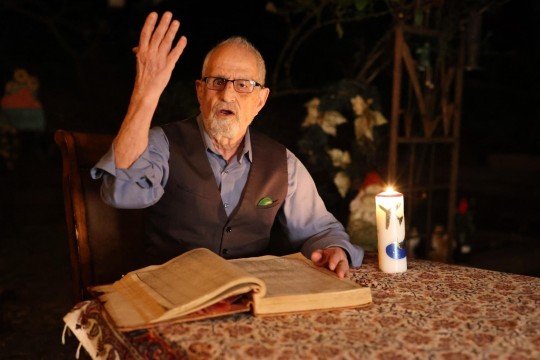

_*Experiences with Maha Periyava: Paul Brunton’s search for his Master*_

*Very Long but worth reading till the end.*

About the time of tiffin, that is, tea and biscuits, the servant announces a visitor. The latter proves to be a fellow member of the ink-stained fraternity, to wit, the writer Venkataramani. Several letters of introduction lie where I have thrown them, at the bottom of my trunk. I have no desire to use them. This is in response to a curious whim that it might be better to tempt whatever gods there be to do their best – or worst. However, I used one in Bombay, preparatory to beginning my quest, and I used another in Madras because I have been charged to deliver a personal message with it. And thus, this second note has brought Venkataramani to my door. He is a member of the Senate of Madras University, but he is better known as the author of talented essays and novels of village life. He is the first Hindu writer in Madras Presidency, who uses the medium of English, to be publicly presented with an inscribed ivory shield because of his services to literature.

He writes in a delicate style of such merit as to win high commendation from Rabindranath Tagore in India and from the late Lord Haldane in England. His prose is piled with beautiful metaphors, but his stories tell of the melancholy life of neglected villages.

As he enters the room I look at his tall, lean person, his small head with its tiny tuft of hair, his small chin and bespectacled eyes. They are the eyes of a thinker, an idealist and a poet combined. Yet the sorrows of suffering peasants are reflected in their sad irises. We soon find ourselves on several paths of common interest. After we have compared notes about most things, after we have contemptuously pulled politics to pieces and swung the censers of adoration before our favourite authors, I am suddenly impressed to reveal to him the real reason of my Indian visit. I tell him with perfect frankness what my object is; I ask him about the whereabouts of any real Yogis who possess demonstrable attainments; and I warn him that I am not especially interested in meeting dirt-besmeared ascetics or juggling faqueers.

He bows his head and then shakes it negatively. “India is no longer the land of such men. With the increasing materialism of our country, its wide degeneration on one hand and the impact of unspiritual Western culture on the other, the men you are seeking, the great masters, have all but disappeared. Yet I firmly believe that some exist in retirement, in lonely forests perhaps, but unless you devote a whole lifetime to the search, you will find them with the greatest difficulty. When my fellow Indians undertake such a quest as yours, they have to roam far and wide nowadays.

Then how much harder will it be for a European?”

“Then you hold out little hope?” I ask.

“Well, one cannot say. You may be fortunate.”

Something moves me to put a sudden question:

“Have you heard of a master who lives in the mountains of North Arcot?”

He shakes his head. Our talk wanders back to literary topics. I offer him a cigarette, but he excuses himself from smoking. I light one for myself and while I inhale the fragrant smoke of the Turkish weed, Venkataramani pours out his heart in passionate praise of the fast disappearing ideals of old Hindu culture. He makes reference to such ideas as simplicity of living, service of the community, leisurely existence and spiritual aims. He wants to lop off parasitic stupidities which grow on the body of Indian society. The biggest thing in his mind, however, is his vision of saving the half-million villages of India from becoming mere recruiting centres for the slums of large industrialized towns. Though this menace is more remote than real, his prophetic insight and memory of Western industrial history sees this as a certain result of present day

Trends. Venkataramani tells me that he was born in a family with a property near one of the oldest villages of South India, and he greatly lamented the cultural decay and material poverty into which village life had fallen. He loves to hatch out schemes for the betterment of the simple village folk, and he refuses to be happy whilst they are unhappy. I listen quietly in the attempt to understand his viewpoint. Finally, he rises to go and I watch his tall thin form disappear down the road.

Early next morning I am surprised to receive an unexpected visit from him. His carriage rushes hastily to the gate, for he fears that I might be out. “I received a message late last night that my greatest patron is staying for one day at Chingleput,” he bursts out. After he has recovered his breath, he continues: “His Holiness Shri Shankara Acharya of Kumbakonam is the Spiritual Head of South India. Millions of people revere him as one of God’s teachers. It happens that he has taken a great interest in me and has encouraged my literary career, and of course he is the one to whom I look for spiritual advice. I may now tell you what I refrained from mentioning yesterday. We regard him as a master of the highest spiritual attainment. But he is not a Yogi. He is the Primate of the Southern Hindu world, a true saint and great religious philosopher. Because he is fully aware of most of the spiritual currents of our time, and because of his own attainment, he has probably an exceptional knowledge of the real Yogis. He travels a good deal from village to village and from city to city, so that he is particularly well informed on such matters. Wherever he goes, the holy men come to him to pay their respects. He could probably give you some useful advice. Would you like to visit him?”

“That is extremely kind of you. I shall gladly go. How far is Chingleput?”

“Only thirty-five miles from here. But stay?”

”Yes?”

“I begin to doubt whether His Holiness would grant you an audience. Of course I shall do my utmost to persuade him.

But “”I am a European!” I finish the sentence for him. “I understand.”

” You will take the risk of a rebuff?” he asks, a little anxiously.

“Certainly. Let us go.”

After a light meal we set out for Chingleput. I ply my literary companion with questions about the man I hope to see this day. I learn that Shri Shankara lives a life of almost ascetic plainness as regards food and clothing, but the dignity of his high office requires him to move in regal panoply when travelling. He is followed then by a retinue of mounted elephants and camels, pundits and their pupils, heralds and camp followers generally. Wherever he goes he becomes the magnet for crowds of visitors from the surrounding localities. They come for spiritual, mental, physical and financial assistance. Thousands of rupees are daily laid at his feet by the rich, but because he has taken the vow of poverty, this income is applied to worthy purposes. He relieves the poor, assists education, repairs decaying temples and improves the condition of those artificial rain-fed pools which are so useful in the riverless tracts of South India. His mission, however, is primarily spiritual. At every stopping-place he endeavours to inspire the people to a deeper understanding of their heritage of Hinduism, as well as to elevate their hearts and minds. He usually gives a discourse at the local temple and then privately answers the multitude of querents who flock to him. I learn that Shri Shankara is the sixty-sixth bearer of the title in direct line of succession from the original Shankara. To get his office and power into the right perspective within my mind, I am forced to ask Venkataramani several questions about the founder of the line.