#la scala theatre

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Today’s watch:

Carla Fracci, Dance in the heart. Carla Fracci, La danza nel cuore.

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#la scala#Italian ballet#prima ballerina#prima ballerina assoluta#romantic ballet#la scala theatre#la scala Milan#Carolina Fracci#Carla Fracci#la danza nel cuore#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Highlight of the Day - 03.08.2024

Apart from the hot summer and the peak of holiday season, the world is abuzz with lots of developments. As the last 24 hours were full of several important news, we chose to share 3 current highlights for today. Kamala Harris the to-be-Democratic-Nominee for President of USA The highlight news of today is that Vice President Kamala Harris was able to collect enough Democratic Party delegate…

#Actuality#Aerosmith Retires#Agenda 47#Amusement Park History#Brad Whitford#Cultural Milestones#Donald Trump#Dream on song#Elon Musk Legal Battle#Entertainment Updates#Harris vs trump#highlights of the day#Historic Events#Italy#Joe Biden#Joe Perry#Joey Kramer#Kamala Harris 2024#La Scala Theatre#learning by history#Legal News#Music Legends#Musical hits#Peace Out tour#Performing Arts History#Political News#President of USA#Project 2025#Rock And Roll Farewell#rock legends

0 notes

Text

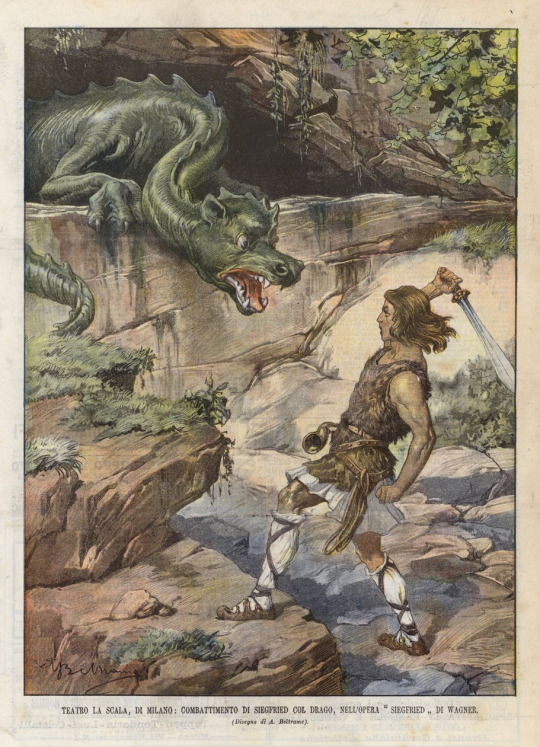

Siegfried Fighting with the Dragon by Achille Beltrame

#siegfried#dragon#art#achille beltrame#fafnir#fafner#dragons#richard wagner#milan#theatre#la scala#opera#der ring des nibelungen#the ring of the nibelung#german#germany#germanic heroic legend#norse mythology#germanic mythology#nibelungenlied#fáfnir#europe#european#mythical creatures#sword#gram#nothung#balmung#völsunga saga#sigurd

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jorge Grau | La Scala Theatre Ballet School (Scuola di Ballo del Teatro alla Scala)

#jorge grau#la scala theatre ballet school#scuola di ballo del teatro alla scala#balletphotography#ballet slippers

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The costumes inside laboratories of Teatro alla Scala/La Scala, Milan

[taken by Molteni Motta in 2013]

#costumes for don carlo extras in the second pic dawg ... watch me steal all these#theatre#la scala#costume#clothes#opera#*

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Become a Successful Singer

HINTS ON THE CULTIVATION OF THE VOICE.

By ENRICO CARUSO.

It has often struck me, in a lengthy experience as a singer, that there is one point in particular about the human voice which is far too little appreciated by the rising generation of aspiring vocalists, and that is its wonderful reciprocity. Tend it, nurse it, "feed it on a proper diet," and it will invariably comport itself in the most amiable manner possible. But neglect it, treat it as an organ which is best left to look after itself, and the voice will at once, in revenge for this callous behaviour, retaliate by behaving itself in a manner which is perhaps best described as of the "hooliganistic" order.

And yet, as an actual fact, but a very small percentage indeed of would-be singers ever really seem to think it worth their while to bear in mind this axiom, for axiom it surely is, that the voice requires proper care and proper exercise to keep it in its best form just as much as is a certain amount of exercise necessary to the maintenance of good health in every human being.

Unfortunately, however, there would seem to be a prevalent impression among many amateur and not a few professional singers that singing is an art which can be acquired in quite a short time. Thus, is it not curious that while many students of the piano or the violin will willingly devote years of strenuous and conscientious practice to the study of the technique of these instruments, would-be singers frequently seem to expect to learn how to use their voice to the best advantage after a period of vocal practice extending, maybe, over a year or so, but more often even over only a few months? This policy, I need scarcely remark, is absolutely ruinous to the future careers of young singers, for no matter how naturally talented any individual vocalist may be, he or she cannot possibly produce the best results as a singer unless the particular organs brought into play in the process of singing have been subjected to a proper and sufficiently long course of training. Since the days of the old Italian masters there can be no shadow of doubt that, musically, we have advanced considerably; but sometimes, when I think of the rather slipshod methods of cultivating the voice advocated by many so-called "professors" to-day, the thought impresses itself on my mind that the detailed principles of the old Italian masters who, above all other considerations, insisted on a long course of voice training as being the only possible means to the attainment of the best art, possessed more to recommend them than do many of the modern "artifices" of voice-cultivation proffered by many teachers of singing to-day.

In a short article, of course, it is obviously impossible to go in detail into all the rules which should be observed by singers who are prepared to undertake the task of cultivating their voices on a conscientious and sound basis. At the same time, I hope to be able to suggest various hints and wrinkles which should prove of real value to aspiring singers.

In the first place, therefore, let me say at once that it is the most fatal of all errors for a singer to make too much use of the voice, for the muscles of the larynx are so delicate that they cannot possibly stand the strain of the "learn-to-sing-in-a-hurry" methods of those who hope to attain the highest point of proficiency without devoting sufficient time to that "drudgery" which is absolutely essential to the real and perfect cultivation of the voice.

For this all-important reason I would counsel singers to see to it at all times that in the early days of their training they do not devote too much time to practice. If they will take my advice, until they become thoroughly proficient in "managing" the voice—a happy state of affairs which can only be acquired after long practice—they will at first never devote more than fifteen minutes a day—in the early morning is, perhaps, the best time—to practice. I can readily realise that this must seem a very short time to enthusiasts who are willing to give up all their spare time to the study of voice cultivation, but it is, nevertheless, quite long enough, for the slightest strain put upon the voice may retard a singer's progress by months, while, on the other hand, as I pointed out at the beginning of this article, if the singer will only bear in mind that the voice requires the most careful "nursing" of perhaps all the organs, and must on no account be strained, he will soon find that, though he may not be aware of any improvement in it, his voice is, nevertheless, slowly but surely improving and gaining in strength through his gradually-growing knowledge of technique.

Another point in the cultivation of the voice which I often think is not sufficiently strongly emphasised to-day is the fact that young singers can improve their methods in the most extraordinarily rapid manner by studying the methods of other and more experienced singers. In singing, as in the cultivation of the other arts, in time the student will get what he works for, but it is surely unreasonable for him to expect to sing effectively by his own inspiration. He will be wise, therefore, to seize every opportunity of studying as closely as possible the methods of those who have thoroughly mastered the technique of singing. For true art, of course, there must be more than technique, but I would point out that in singing there is no art without sound methods of execution, which, after all, to all intents and purposes constitute technique. In the cultivation of expression, technique, and sympathy in the voice, there is no better teacher than "a visit to the opera." Still, I make no doubt that of the hundreds of aspiring singers who visit the opera during the season but very few indeed would care to go through the years of drudgery as conscientiously as have those who seem to sing so easily and to combine the art of acting and singing at the same time with equal facility. After all, the highest art lies in the concealment of that art, and I take it that it is because a really proficient opera singer accomplishes his performance with such apparent ease that the difficulties of operatic singing are so little appreciated.

Still, as I have said, I am strongly of the opinion that young singers can learn much from studying the methods of operatic vocalists, that is to say, when they have mastered the rudiments of voice cultivation, into which I need not enter here, for my object is rather to show singers various methods by which they can attain the highest art when they have served a sufficient apprenticeship under masters whose duty it is to teach them the elementary rules of singing.

For my own part, I find that a singer's life, with its constant rehearsals and performances, is such a busy one that not much opportunity is allowed him for indulging in outdoor exercise. Many other enthusiastic singers doubtless find themselves situated in very similar straits, not perhaps on account of their public engagements, but through the "calls" made upon their time by business, social, or domestic duties. In the cultivation of the voice, however, a certain amount of exercise is essential to good health, as, by the same token, is good health a sine quâ non to the attainment of the highest art in singing. It may be of service, therefore, if I explain the rules I observe when I find the calls upon my time too numerous to enable me to get as much exercise as I should otherwise like.

No matter how busy I am, when I rise in the morning I invariably indulge in a few simple physical exercises, similar in character to those I used to practise when, as a young man, the time came for me to serve my king and country as a soldato, or, if I feel that these are becoming monotonous, for a few minutes I find practice with a pair of dumb-bells—not too heavy, by the way—very beneficial. But save these mild forms of relaxation I have, as a rule, to rest content with, in the way of outdoor exercise, an occasional motor drive. Nevertheless, I would point out that, in itself, singing, with its constant deep inhalation, is by no means inconsiderable exercise, though, to be sure, I am well aware that it cannot be so health-giving in its effects as actual exercise in the open air.

Yes, past a doubt, young singers can learn much about the highest art of the cultivation of the voice from watching the knowledge of technique of our best operatic artists, and from observing their methods of "managing" the voice. Still, to thoroughly grasp the progress of the opera-singer's art, it will be necessary for students to appreciate the fact that Italian singing has had two important culminating periods, each of which was illustrated by a group of great singers, the first of which was made up of pupils of Bernacchi, Pistocchi, Francesca Cuzzoni, and other contemporary teachers. These great singers brought the art of bel canto to as near a state of perfection as has ever been known. But one has to remember the conditions under which they sang.

Thus Victor Maurel writes:—"In the days of the schools of the art of bel canto the masters did not have to take truth for expression (l'expression juste) into account, for the singer was not required to render the sentiments of the dramatis personæ with verisimilitude; all that was demanded of him was harmonious sounds, the bel canto." In other words, all that the singer had to do was to sing, for the emotions themselves had not to be portrayed, the psychical character of the dramatis personæ not being taken into account.

In consequence, the perfection of the singer's voice was but slightly interfered with, as, at most, he had little or no acting to do, a conventional oratorical gesture or two being considered quite sufficient for the fashion of the period. And it is scarcely necessary to remark that the great singers of this period were skilful enough musicians to prevent such unimportant gestures, which hardly deserve the dignity of the name of acting, from being an obstacle to the high quality of their singing.

In the second period of Italian singing, however, the period which coincides with the Rossini-Donizetti-Bellini period of opera in its heydey, the conditions, we find, were greatly altered. The music at this time was at once more dramatic and more scenic, and although the singing was still bel canto, the opera singer of the period was called upon not only to sing well, but to sing dramatically, though it must be said that the music itself provided larger scope for the actor's art, in that it gave more favourable opportunity for specialising and differentiating the emotions.

In "The Opera Past and Present" we find the following intensely interesting allusion to these two great culminating periods of Italian singing:—"A comparison of these two periods of Italian singing indicates the direction matters have taken with the opera singer from Handel's time to our own. From then to now he has had to face an ever-increasing accumulation of untoward conditions; his professional work has become more and more complicated. From Rossini's time down to this the purely musical difficulties he has had to face have been constantly on the increase—complexity of musical structure, rhythmic complications, hazardous intonations.

"He has to fight against the more and more brilliant style of instrumentation, often pushed to a point where the greatest stress of vocal effort is required of him to make himself heard above the orchestral din; more and better acting is demanded of him, he finds the vague generalities of histrionism no longer of avail; for these must make way for a highly specialised, real-seeming dramatic impersonation; intellectually and physically his task has been doubled and trebled. Above all, the sheer nervous tension of situations and music has so increased as to make due self-control on his part less easy. The opera singer's position to-day is verily no joke; he has to face and conquer difficulties such as the great bel cantists of the Handel period never dreamt of."

It has ever been my contention that the conscientious artist should carefully read and re-read the whole libretto, so as to inform himself of the poet's purpose and meaning in the construction and development of the plot, as well as to ever bear in mind his conception of the composer's idea of how the poetry and the various aspects of mind of the characters should be aptly and effectively musicked and interpreted so as to awaken a kindred, or appreciative, feeling in the minds of his hearers.

Besides this, the opera singer who aspires to rise to great heights must possess a keen nervous susceptibility, for only a man or woman of high nervous temperament can reasonably hope to succeed as a lyrico-dramatic artist. Again, in the great operas a most severe strain is placed upon the leading singers, for while they are portraying various emotions—-Love, Hate, Rage, or Laughter—they have, at the same time, to watch the conductor with most minute care lest they fail in time and rhythm.

In fine, though I think but few other than really conscientious students of singing entirely appreciate the fact, the opera-singer of to-day is called upon to possess a far greater knowledge of vocal technique than was ever demanded of him before in the history of singing, as those "good and golden days"—golden only to the moderate performer with but little ambition—when the singer who perhaps scarcely knew more than a few notes of music could, nevertheless, still arouse the plaudits of the public are gone—never to return.

I hope, by the way, that it will not be thought that I have entered too technically into the requirements demanded from an aspirant to operatic fame to-day. I scarcely think, however, that I can have done so, for I feel sure every really aspiring vocalist would prefer to know the exact heights to which he must cultivate his voice either on the operatic stage or concert platform, or even for the drawing-room, that is to say, if he is ever to make a great name for himself in preference to resting content to remain one of the "moderates," of which the musical profession is altogether already too full, not because there is a lack of singers with good voices, but largely, as I have always maintained, because there is a far too prevalent tendency amongst singers these days to shirk the real hard work which must be accomplished before lasting success can be attained.

In conclusion, in order to allow singers' voices to develop in a satisfactory manner, let me counsel them never to attempt those selections in public the range of which taxes and strains them to the utmost, for when a singer "exceeds" his proper range injury to the throat is always liable to follow. Better rather, therefore, is it that a song should be transposed to a lower key if a singer is determined to attempt it than that the voice should be unduly taxed.

And now I will say addio, though I would add that it is my sincere hope that some of the few hints I have given on the cultivation of the voice and of the heights of excellence to which ambitious singers should aspire may prove of real value to those with sufficient pluck to face the task of studying the art of the cultivation of the voice in a really conscientious manner. Hard work accomplishes wonders where the voice is concerned. Let me, therefore, counsel singers never to despair of attaining a state as near to perfection as possible, for it is those who are most alive to their own imperfections who will assuredly "go farthest" in the singing world.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Errico Caruso#Enrico Caruso#lyric tenor#dramatic tenor#Metropolitan Opera#Met#La Scala#Bolshoi Theatre#Mariinsky Theatre#classical muscian#classical musicians#classical history#opera history#history of music#history#musician#musicias#diva#tenor#The King of Tenors

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Senza Puccini non c'è l'opera; senza l'opera, il mondo è un posto ancora più tetro di quanto il telegiornale della sera voglia farci credere.

William Berger

1 note

·

View note

Text

Marta Arduino and Nicola del Freo in La Scala’s production of Alexei Ratmansky’s reconstruction of Swan Lake.

Photo by Monica Bragagnoli

#swan lake#marta arduino#nicola del freo#la scala#ballet of la scala theatre#teatro alla scala#lago dei cigni#le lac des cygnes#alexei ratmansky#arduino#del freo#monica bragagnoli#bragagnoli

0 notes

Text

Full Length Ballet Performances

Cinderella

Instituto Nacional De Las Bellas Artes 🩰 Russian National Ballet

Coppelia

Paris Opera Ballet 🩰 Bolshoi Ballet Theatre

Don Quixote

The National Ballet Theatre of Ukraine 🩰Teatro alla Scala di Milano Marrinsky Theatre

Giselle

Bolshoi Ballet Theatre 🩰 Polish National Ballet 🩰 The Royal Danish Ballet 🩰 National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Mari El

La Bayadère

National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Mari El.🩰 Bolshoi Ballet Theatre

La Fille Mal Gardée

Serbian National Ballet

La Sylphide

The Royal Danish Ballet

Marguerite & Armand

The Royal Ballet

Mayerling

Stainslavsky Ballet

Nutcracker

The New York City Ballet 🩰Marrinsky Theatre 🩰 National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Marie.El

Romeo and Juliet

Ural Opera Ballet🩰 Bolshoi Ballet Theatre

Swan Lake

Kirkov Ballet 🩰 St Petersburg Ballet Theatre 🩰 American Ballet Theatre 🩰 Bolshoi Ballet Theatre

The Sleeping Beauty

Staatsballett Berlin 🩰 National Opera and Ballet Theatre of Mari El 🩰 Marrinsky Theatre 🩰 l'Opéra Bastille 🩰Teatro alla Scala 🩰 Bolshoi Ballet Act 1 Bolshoi Ballet Act 2

The Rite of Spring (Le sacre du printemps)

Marrinsky Theatre

I was born in the correct generation because I loved those photos so much, I decided to look up the ballet so I could watch it and there it was ! I have added other full length performances as well and for most of the pieces I have added different ballet companies (if I could find) just because different ballet companies means different choreography ( not always but certain companies are reowned for their distinct style)

Enjoy!

xo Daphne

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

This year (2024) the Opera season will open with the play La Forza Del Destino once again by Giuseppe Verdi. If you want to know more about the Opera, look here. You can watch it, as every year, on Raiuno on December 7th at 5:45 PM (GMT+1) [link here- you will need an Italian vpn to watch]. As for past year, you may listen to it on Rai Radio3 and watch it on Raiplay for 15 days after the end [link above are valid this time too].

7-8 Dicembre

Today (7 dicembre) is Milano’s patron day, Sant’Ambrogio, and the town is plenty of little-cozy-Christmas-like markets: these are called “Obej Obej” (it sounds like “obey” repeated twice) and are pretty famous in Italy. This name was given as a reminder of the time when the papal herald entered Milan and started giving gifts to the kids, and these kids yelled “oh bej oh bej!” that in Milan’s dialect means “oh nice oh nice!”.

Tonight will be also celebrated the opening of the Opera season at the theater La Scala, again in Milan. It’s generally a huge party with many famous people, both political and not, followed by many TVs (but it’s not broadcasted “live”, you have to be there to see it). This year the chosen play is “Andrea Chénier”.

Christmas lights and decorations mostly start showing up today and tomorrow (8 dicembre) - the Immacolata Concezione holiday (a religious holiday, but also a National holiday): people, staying home from work, start putting decorations in their houses and also Christmas shopping begins for real.

#curiosità curiosities#italy#italian#italiano#random italian stuff#culture#tradition#la scala#prima della scala#opera#plays#theatre#verdi#obej obej#sant'ambrogio#lombardy

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think of Yesenia Anushenkova and Elisabetta Nalin?

As usual… usual disclaimer: they are so youngggg, so who knows!

They’re both interesting however, Yesenia because she’s not the typical VBA grad, she graduated from Boris Eifman Academy in 2024, but… very interestingly, had joined the Mariinsky Ballet already as a trainee in 2023–and then made coryphee with VBA trained Alice Barinova—they’re often doing roles together. Fun fact, Yesenia l used to be in the same class as Darina Mooseva, who transferred to BBA, graduated in 2024, and is now at Bolshoi doing quite well for her first season, the two of them seem to still be friends.

The Italian Elisabetta is equally interesting, being a foreigner in Russia, I believe before her four years at vaganova she had studied at La Scala, and she ended at Bolshoi! She was in the same class as Alicia Barinova, and right next to her for the exam, since Kamila Sultangareeva moved to BBA, and was really featured in VBA graduation performances, she was the lead in the Spanish wedding and did Liliac Fairy for the first few performances before passing the role to Ekaterina Morotzova. At the Bolshoi she seems to be getting quite a lot of roles, alongside Kuprina (2023 grad) and her friend, Zakota, who also graduated in 2024 but was top of her class in the parallel class, who ended up at the Bolshoi with her. I recently saw she was rehearsing sulphide. The only thing I don’t love is how extremely hyperextended her knees and how extremely arched her foot is, when I watch clips I’m always afraid her knee will snap backwards and it might affect the lightness of her jumps. But the rest of her looks really strong and healthy, so I’m sure she can absolutely manage and has the muscles to protect herself, but visually sometimes it makes me afraid.

About their dancing… honestly I don’t have anything interesting to say? Sorry 😭 I don’t have anything to critique or praise, they’re just babies in their first official season! Lets see 🤷♀️

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#russian ballet#vaganova#vaganova method#vaganova academy#la scala#boris eifman#vaganova tecnique#mariinsky theatre#bolshoi theatre#Elisabetta nallin#YESENIA ANUSHENKOVA

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Umberto Brunelleschi, Woman in Sheer Dress with Bird of Paradise, 1920's

Umberto Brunelleschi (1879 - 1949) was born in Italy, but moved to France in 1900, where he became a printer, book illustrator, and set and costume designer. He contributed to several French fashion magazines, such as Journal des Dames et des Modes, Gazette du Bon Ton, and Les Feuilles d'Art. Between the two world wars he worked on set and costume designs for several theaters, including Folies Bergère in Paris, the Roxy Theatre in New York, and La Scala in Milan. Some of the books he illustrated are Candide (Voltaire), Contes du temps jadis (Charles Perrault), and Les Masques et les Personnages de la Comedie Italienne. Towards the end of his life he also did a number of erotica illustrations. (x)

#Umberto Brunelleschi#art deco#illustration#1920s#bird of papradise#sheer dress#book illustration#vintage#1920s illustrations#art#brunelleschi#fashion illustration#painting#risque#birds-of-paradise#art deco design#art deco illustration

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompt: Theatre (August 29) and Italy (August 30) from @into-the-jeggyverse

Word count: 435 words

Pairing: Jegulus (modern AU - genderfluid Regulus)

⚠️ Warnings: none

James was still in shock. He couldn't understand how Regulus managed to get tickets in the first rows at La Scala, the most beautiful theater in the world. Not only that, but it was also the most acclaimed show of the year. James bought himself a new tuxedo just for this occasion.

When they started dating, James revealed to Regulus that one of his biggest wishes was to go to Italy to see a show at La Scala. Regulus' great wish was a little simpler: to see Michelangelo's "David" in Florence. After four years together, the two simultaneously came up with the idea of fulfilling the other's wish. It had been a mutual surprise for their four year anniversary. James bought the tickets for Italy, Regulus secured invitations to La Scala. First they were going to see the show in Milan, and tomorrow morning they were going to leave for Florence.

James was arranging his bow tie in front of the mirror when he heard the bedroom door open, followed by a subtle and pleasant sound of heels. He turned his head and smiled when Regulus appeared in the hall, wearing a black dress with long sleeves, a wide skirt and gloves, similar to Dior dresses from the 50's. They also had a pair of green heels, matching with the necklace around their neck and their red lips.

"How do I look?" Regulus asked, and with audible emotions in their tone.

Ever since Regulus had discovered the complexity surrounding the idea of gender, they tried to find a way to express themselves in their complete truth. It was a long way to go, especially because of the way they were raised. Every time they felt the need to express their feminine side, Walburga's voice echoed in their head. Beside hers, however, there is another voice, a warmer one that supports and accepts.

"You're gorgeous, Regulus" James said and approached his partner to give them a kiss. "This dress fits you so well, I was right when I told you that you should buy it".

Regulus smiled and went to get their coat so they could leave. James looked at them from behind with eyes full of love. He couldn't wait to leave for Florence tomorrow. He had the ring ready for a year, and the plan was absolutely perfect. James would ask Regulus to marry him with "David" as a witness, after which they would watch the whole city from Piazzale de Michelangelo. Both were possessed by a type of magic that only a country like Italy could awaken in someone.

#microfics#dailyprompt#marauders era#james potter#james x regulus#jeggyverse microfic#regulus black#jegulus#jegulus microfic#dead gay wizards

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

On February 17, 1904, Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly premieres at the La Scala theatre in Milan, Italy.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opera on YouTube, Part 2

Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro)

Glyndebourne Festival Opera, 1973 (Knut Skram, Ileana Cotrubas, Kiri Te Kanawa, Benjamin Luxon; conducted by John Pritchard; English subtitles)

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle studio film, 1976 (Hermann Prey, Mirella Freni, Kiri Te Kanawa, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; conducted by Karl Böhm; English subtitles) – Acts I and II, Acts III and IV

Tokyo National Theatre, 1980 (Hermann Prey, Lucia Popp, Gundula Janowitz, Bernd Weikl; conducted by Karl Böhm; Japanese subtitles)

Théâtre du Châtelet, 1993 (Bryn Terfel, Alison Hagley, Hillevi Martinpelto, Rodney Gilfry; conducted by John Eliot Gardiner; Italian subtitles)

Glyndebourne Festival Opera, 1994 (Gerald Finley, Alison Hagley, Renée Fleming, Andreas Schmidt; conducted by Bernard Haitink; English subtitles)

Zürich Opera House, 1996 (Carlos Chaussón, Isabel Rey, Eva Mei, Rodney Gilfry; conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt; English subtitles)

Berlin State Opera, 2005 (Lauri Vasar, Anna Prohaska, Dorothea Röschmann, Ildebrando d'Arcangelo; conducted by Gustavo Dudamel; French subtitles)

Salzburg Festival, 2006 (Ildebrando d'Arcangelo, Anna Netrebko, Dorothea Röschmann, Bo Skovhus; conducted by Nikolas Harnoncourt; English subtitles) – Acts I and II, Acts III and IV

Teatro all Scala, 2006 (Ildebrando d'Arcangelo, Diana Damrau, Marcella Orasatti Talamanca, Pietro Spagnoli; conducted by Gérard Korsten; English and Italian subtitles)

Salzburg Festival, 2015 (Adam Plachetka, Martina Janková, Anett Fritsch, Luca Pisaroni; conducted by Dan Ettinger; no subtitles)

Tosca

Carmine Gallone studio film, 1956 (Franca Duval dubbed by Maria Caniglia, Franco Corelli, Afro Poli dubbed by Giangiacomo Guelfi; conducted by Oliviero de Fabritiis; no subtitles)

Gianfranco de Bosio film, 1976 (Raina Kabaivanska, Plácido Domingo, Sherrill Milnes; conducted by Bruno Bartoletti; English subtitles)

Metropolitan Opera, 1978 (Shirley Verrett, Luciano Pavarotti, Cornell MacNeil; conducted by James Conlon; no subtitles)

Arena di Verona, 1984 (Eva Marton, Jaume Aragall, Ingvar Wixell; conducted by Daniel Oren; no subtitles)

Teatro Real de Madrid, 2004 (Daniela Dessí, Fabio Armiliato, Ruggero Raimondi; conducted by Maurizio Benini; English subtitles)

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 2011 (Angela Gheorghiu, Jonas Kaufmann, Bryn Terfel; conducted by Antonio Pappano; English subtitles)

Finnish National Opera, 2018 (Ausrinė Stundytė, Andrea Carè, Tuomas Pursio; conducted by Patrick Fournillier; English subtitles)

Teatro alla Scala 2019 (Anna Netrebko, Francesco Meli, Luca Salsi; conducted by Riccardo Chailly; Hungarian subtitles)

Vienna State Opera, 2019 (Sondra Radvanovsky, Piotr Beczala, Thomas Hampson; conducted by Marco Armiliato; English subtitles)

Ópera de las Palmas, 2024 (Erika Grimaldi, Piotr Beczala, George Gagnidze; conducted by Ramón Tebar; no subtitles)

Don Giovanni

Salzburg Festival, 1954 (Cesare Siepi, Otto Edelmann, Elisabeth Grümmer, Lisa della Casa; conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler; English subtitles)

Giacomo Vaccari studio film, 1960 (Mario Petri, Sesto Bruscantini, Teresa Stich-Randall, Leyla Gencer; conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli; no subtitles)

Salzburg Festival, 1987 (Samuel Ramey, Ferruccio Furlanetto, Anna Tomowa-Sintow, Julia Varady; conducted by Herbert von Karajan; no subtitles)

Teatro alla Scala, 1987 (Thomas Allen, Claudio Desderi, Edita Gruberova, Ann Murray; conducted by Riccardo Muti; English subtitles)

Peter Sellars studio film, 1990 (Eugene Perry, Herbert Perry, Dominique Labelle, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson; conducted by Craig Smith; English subtitles)

Teatro Comunale di Ferrara, 1997 (Simon Keenlyside, Bryn Terfel, Carmela Remigio, Anna Caterina Antonacci; conducted by Claudio Abbado; no subtitles) – Act I, Act II

Zürich Opera, 2000 (Rodney Gilfry, László Polgár, Isabel Rey, Cecilia Bartoli; conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt; English subtitles)

Festival Aix-en-Provence, 2002 (Peter Mattei, Gilles Cachemaille, Alexandra Deshorties, Mirielle Delunsch; conducted by Daniel Harding; no subtitles)

Teatro Real de Madrid, 2006 (Carlos Álvarez, Lorenzo Regazzo, Maria Bayo, Sonia Ganassi; conducted by Victor Pablo Pérez; English subtitles)

Festival Aix-en-Provence, 2017 (Philippe Sly, Nahuel de Pierro, Eleonora Burratto, Isabel Leonard; conducted by Jérémie Rohrer; English subtitles)

Madama Butterfly

Mario Lanfranchi studio film, 1956 (Anna Moffo, Renato Cioni; conducted by Oliviero de Fabritiis; no subtitles)

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle studio film, 1974 (Mirella Freni, Plácido Domingo; conducted by Herbert von Karajan; English subtitles)

New York City Opera, 1982 (Judith Haddon, Jerry Hadley; conducted by Christopher Keene; English subtitles)

Frédéric Mitterand film, 1995 (Ying Huang, Richard Troxell; conducted by James Conlon; English subtitles)

Arena di Verona, 2004 (Fiorenza Cedolins, Marcello Giordani; conducted by Daniel Oren; Spanish subtitles)

Sferisterio Opera Festival, 2009 (Raffaela Angeletti, Massimiliano Pisapia; conducted by Daniele Callegari; no subtitles)

Vienna State Opera, 2017 (Maria José Siri, Murat Karahan; conducted by Jonathan Darlington; no subtitles)

Wichita Grand Opera, 2017 (Yunnie Park, Kirk Dougherty; conducted by Martin Mazik; English subtitles)

Teatro San Carlo, 2019 (Evgenia Muraveva, Saimir Pirgu; conducted by Gabriele Ferro; no subtitles)

Rennes Opera House, 2022 (Karah Son, Angelo Villari; conducted by Rudolf Piehlmayer; French subtitles)

#opera#complete performances#youtube#le nozze di figaro#the marriage of figaro#tosca#don giovanni#madama butterfly#madame butterfly#wolfgang amadeus mozart#giacomo puccini

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I will remember the extraordinary soprano Adelina Patti (1843-1919). Here we see this antique Postcard from 1898.

Spanish-born soprano who was one of the greatest of her century.

The Spanish-born soprano Adelina Patti was the most renowned singer in Europe and the United States for over 30 years. She was born in 1843, the youngest of three children, into a family of opera singers and musicians. Her parents were opera performers well known in Europe by the time of Patti's birth in Madrid, where they were on tour. Her Italian father was Salvatore Patti; her Spanish mother was Caterina Chiesa Barili-Patti , known before her marriage as Signora Barili. Caterina also had four children from an earlier marriage, and all seven of her children would enjoy successful careers as singers.

When Adelina Patti was four the family moved to New York, where her father became an opera house manager. Her half-brother Ettore Barili gave Patti voice lessons starting at age five; by the age of seven Adelina was recognized as a child prodigy and the next year she gave her debut concert at New York City's Tripler Hall. Audiences and critics at subsequent concerts were stunned by the maturity, range, and purity of her voice. Her success in New York led to a three-year tour of American cities, unprecedented for such a young child, from 1851 to 1854. A second concert tour followed in 1857. Patti's sister Amelia Patti was married to the renowned pianist Maurice Strakosch; he took care of Adelina while on tour and served as her manager, instructor, and accompanist. She received only a minimal education, although her family background and musical training made her fluent in Spanish, French, Italian, and English. Her parents and Strakosch continued training Patti in the demands of operatic singing until they felt she was prepared to sing opera professionally. They arranged for her critically praised debut in the title role of Lucia di Lammermoor at the New York Academy of Music in 1859; she was 16, and would perform in opera continually for the next half-century, enjoying a career that was decades longer than that of most opera singers. Soon after her debut Patti faced serious family crises, as her father's struggling opera house failed and her mother left the family in 1860 to return to Rome. Patti then began to provide much of the family's income through her performances.

She toured the eastern United States and the West Indies from 1859 to 1861. In 1861, she went abroad, under the care of her father and Strakosch, to perform in La sonnambula at the Covent Garden opera house in London. She was enthusiastically received in London, where she was to perform every autumn for 25 years.

Patti remained on tour in Europe virtually continuously for 20 years, not returning to New York until 1881. She played to crowded houses in Berlin, Brussels, Amsterdam, Vienna, Paris, and across Italy. The operatic roles she chose ranged from light comedy, which she preferred, to tragedy, but whatever role she appeared in, critics were universal in their praise of her acting ability and the emotive power of her voice.

While in Paris in 1866, through her friendship with Empress Eugénie , Patti met the aristocrat Louis de Cahuzac, marquis de Caux, who served as a personal servant to the French emperor Napoleon III. They wished to marry but the marquis was not allowed to retain his privileged position at the French court if he married a working woman. Since Patti would not consider giving up her career, de Caux eventually resigned his post. This freed the couple to marry in 1868, when the new marchioness was 25 years old and her husband 42; however, the marriage lasted less than a decade, and they obtained a legal separation in 1877. As Patti was by then a celebrity throughout Europe and the United States, her marital problems brought scandal to the opera world and were the subject of often sensationalistic newspaper articles in many of the countries she had performed in. In the divorce suit, de Caux charged Patti with an adulterous affair with her co-star, Italian tenor Ernesto Nicolini. She admitted to the affair, but maintained in her defense that de Caux was jealous, controlling, and violent, and that he allowed her no access to her substantial income. The divorce would be finalized in 1885, when de Caux was awarded a settlement of $300,000 from Patti. Freed at last from her unhappy marriage, Patti married Nicolini a few months later.

Despite her personal problems during the separation and divorce, Patti continued to travel widely. She did a concert tour on her return to New York in 1881, followed by two operatic tours of the United States. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, she was the most highly paid and most visible singer in Europe and the United States, receiving press coverage for her appearances as well as for her shocking personal life, legendary jewel collection, enormous wealth, and for her demanding, often capricious personality. She maintained homes across Europe, where she was friends with and frequently host to Europe's royalty and aristocracy. Her fame even led to mentions in contemporary literature and drama, such as Tolstoy's Anna Karenina and Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Patti gave a farewell performance at the New York Metropolitan Opera House in 1887. She and Nicolini then left for another extended tour abroad, performing in Spain and Argentina. In 1895, at age 52, Patti gave six farewell appearances at Covent Garden. She and Nicolini then went into semi-retirement on an estate in Wales called Craig-y-Nos Castle which Patti had purchased some years before, and where she lived with Nicolini prior to their marriage. Patti adopted Wales as the native land she had never truly had, and was respected by the Welsh for her generosity to charitable causes and to her poor neighbors.

Ernesto Nicolini died in 1898. Patti, age 56, remarried a year later. Her third husband, a Swedish aristocrat named Baron Rolf Cederström, was a former military officer who, at the time Patti met him in 1897, was director of the Health Gymnastic Institute in London. At the time of their marriage, Cederström was only 28; their age difference and his occupation made the renowned opera star once again the subject of a flood of news articles and gossip columns.

The urgings of Patti's American fans called her back to the stage in 1903, when she began her last operatic tour at New York's Carnegie Hall. Although Patti was by then considerably older than most opera singers were at retirement, audiences were still moved by her powerful performances. In 1906, at age 63, she made her formal farewell appearance at Albert Hall in London. She also made numerous recordings which have preserved her work and demonstrate the remarkable purity and range which captivated her admirers and which had once led the composer Giuseppe Verdi to call Patti the greatest voice he had ever heard.

Adelina Patti was called out of retirement to perform occasionally at charity events in Wales and England through 1914, when she left the stage for good at age 71. She spent the remaining five years of her life at Craig-y-Nos Castle, where she died in 1919, at age 76. At her wish, her husband buried her in the celebrity cemetery Père Lachaise in Paris. He eventually remarried, selling Craig-y-Nos Castle to the Welsh National Memorial Association which converted it into the Adelina Patti Hospital. The hospital remained in operation until 1986, when the castle and its grounds were turned into a national park and cultural center.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#aria#classical composer#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Adelina Patti#soprano#the nightingale#Covent Garden#His Majesty's Theatre#Metropolitan Opera#Met#La Scala#Paris Opéra#Leo Tolstoy#Anna Karenina#Oscar Wilde#The Picture of Dorian Gray#Royal Albert Hall#Carnegie Hall#classical musican#classical musicians#classical history#opera history#history of music

8 notes

·

View notes