#kings canyon national forest

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

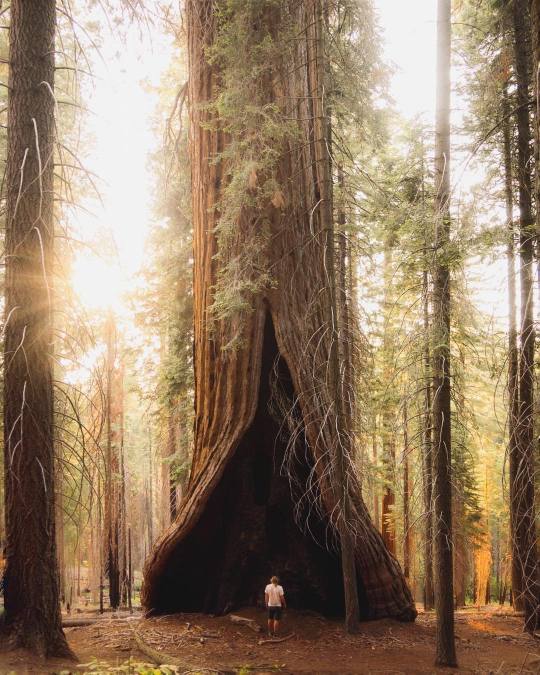

Kings Canyon National Forest, California.

October, 2018

#kings canyon#kings canyon national forest#national forest#clouds#california#nature#nature photography#landscape#landscape photography#travel#original photography#photographers on tumblr#photography#lensblr#wandering#the mountains are calling#wanderingjana

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The giant trees portion of my vacation is over (waves a tearful goodbye to the sequoias) and it’s safe to say that Sequoia and Kings Canyon National parks were the most beautiful place I’ve ever been. There are even more photos on the Nikon, but those will have to wait until I’ve gotten home. I only have a day and some change to explore the Bay Area before catching the train back home. I wish I had more time, even if I’ve already been gone for a good chunk of time.

#trees#landscape photography#wilderness#giant sequoias#sierra nevada#mountains#montane forest#sequoia and kings canyon national parks#waterfall#y’all I basically shed tears the whole time#it was exactly what I pictured in my mind#I kept saying wow over and over and I wouldn’t be surprised if j was starting to get tired of hearing it by the end#finally ticked this off the bucket list#would absolutely go again#now I need to make the most of this day and a half in California before heading back to the Midwest#it’s intimidating haha

233 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Park 🌳

#illustration#artist on tumblr#radarplz#sequoia national park#giant sequoia#kings canyon national park#california#walking the dog#forest#trees#sunbeam#duck tolling retriever#toller

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chasing sequoias in Kings Canyon, California

#kings canyon national park#forest#big trees#travel photography#amazing nature#travel#nature#travel destinations#california#beautiful nature

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shadowing The Sierras

A lot can happen in a week when you’re on the road. This time, the end came. The end to this chapter at least. I’m technically “off the road” for the winter, arriving near Bisbee, Arizona last night. My most recent post had me not even in California yet. The only thing to do is try for a Cliff Notes version, in which I visit my storage, visit the San Francisco Bay, double-back to the Sacramento…

#american road trip#barstow#california#camping#hwy 247#hwy 395#inyoken#Johnny Killmore#joshua tree#kings canyon#lucerne valley#mojave desert#motorcycle travel#national forest#national monument#national parks#sequoia#sonora desert#trailer traah#trailer trash

0 notes

Text

A Monthly Recap: September 2023

What a whirlwind month September has been! We kicked it off and ended it with travel, with lots of adventures sprinkled in throughout! Matt turned 33 – finally caught up with me – and we started getting into the fall feels in home and on the road! Buckle up for a somewhat lengthy roundup – we’ve been busy! Travel Planning This Month Trip planning this month was very concentrated on our…

View On WordPress

#Beavers Bend State Park#Buffalo River#Exeter Corn Maze#Grand Canyon#Kings Canyon#kings canyon national Park#Petrified Forest#Ponca#Roundup#sequoia national park#This Month#Travel#Yosemite

0 notes

Text

Bayverse squandered their "Earth is Unicron" subplot and so many characters.

It would have been so perfect to delve into the really freaky and disturbing lore that humans created across the world...

And found out it was real.

Not just King Arthur and Merlin, but the faint remains of Atlantis, the echoes of mad laughter from a revelry in ancient forests, the fox messengers of Inari traveling everywhere, strange and terrible shapes twisting beneath the ocean waves or off the coast of the Diego Garcia base, ghost towns filled with decrepit homes and buildings with the odd sense between hope and despair as they wait, national statues or ancient sculptures that are actually once living people and beings but transformed into marble and rock and sleeping until they feel the brush of the Matrix or the Allspark, wide and empty stretches of road with no one else and GPS glitches along with time (minutes that go on forever, every so slowly, painfully) as they pass the same canyon formation or homemade sign over and over and over-

I live and love the Other aus too much to give them up, so-

Give me a Mikaela Banes who has become a Dragon herself with the blessings by a Primordial (the Great Shadow, Carnage Incarnate, Unmaker's Mirror) that devoured worlds and remade them as she's the one that offered herself as tribute upon their altar.

Give me a Sam Witwicky who has seen the universe in all of its terrible and wicked glory, beastly and divine in the transcendent music that the Allspark weaves in its own song in the grand orchestra -he has seen, he has heard, and he cannot help but remember snippets beneath the breeze that rustles the trees and the soft patter of rain upon his bedroom window and haunts all his dreams and every waking moment because, despite his vocal adamance, he can never return to normalcy.

Give me Judy Taylor that tries to outrun the monsters in her family's shadows and the ghosts that howl for vengeance and protection in her childhood home by eloping with a Ron Witwicky with a similar madness in his own bloodline.

Give me a William Lennox whose luck is too uncanny, too fortuitous, especially in hindsight, as he feels the very signs his own grandmother would foretell as she hangs trinkets in the branches and leaves sweets on the porch.

("Long ago, Man made peace with Magic.")

#transformers#bayverse#transformers bayverse#mikaela banes#sam witwicky#judy witwicky#ron witwicky#william lennox#unicron#magic#fantasy#maccadam#horror#fic ideas#my writing#look the writers are going “Earth is a reflection of a god of chaos#then FEED ME#nature is already illogical and chaotic#i want the Cybertronians and modern humans to freak the fuck out that magic is real

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. Acadia National Park, Maine

2. American Samoa National Park, American Samoa

3. Arches National Park, Utah

4. Badlands National Park, South Dakota

5. Big Bend National Park, Texas

6. Biscayne National Park, Florida

7. Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Colorado

8. Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah

9. Canyonlands National Park, Utah

10. Capitol Reef National Park, Utah

11. Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico

12. Channel Islands National Park, California

13. Congaree National Park, South Carolina

14. Crater Lake National Park, Oregon

15. Cuyahoga Valley National Park, Ohio

16. Death Valley National Park, California & Nevada

17. Denali National Park, Alaska

18. Dry Tortugas National Park, Florida

19. Everglades National Park, Florida

20. Gates of the Arctic National Park, Alaska

21. Gateway Arch National Park, Missouri

22. Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska

23. Glacier National Park, Montana

24. Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

25. Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming

26. Great Basin National Park, Nevada

27. Great Sand Dunes National Park, Colorado

28. Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee & North Carolina

29. Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Texas

30. Haleakalā National Park, Hawaii

31. Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, Hawaii

32. Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas

33. Indiana Dunes National Park, Indiana

34. Isle Royale National Park, Michigan

35. Joshua Tree National Park, California

36. Katmai National Park, Alaska

37. Kenai Fjords National Park, Alaska

38. Kings Canyon National Park, California

39. Kobuk Valley National Park, Alaska

40. Lake Clark National Park, Alaska

41. Lassen Volcanic National Park, California

42. Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky

43. Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

44. Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

45. New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, West Virginia

46. North Cascades National Park, Washington

47. Olympic National Park, Washington

48. Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

49. Pinnacles National Park, California

50. Redwood National Park, California

51. Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

52. Saguaro National Park, Arizona

53. Sequoia National Park, California

54. Shenandoah National Park, Virginia

55. Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota

56. Virgin Islands National Park, United States Virgin Islands

57. Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota

58. White Sands National Park, New Mexico

59. Wind Cave National Park, South Dakota

60. Wrangell—St. Elias National Park, Alaska

61. Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, Montana & Idaho

62. Yosemite National Park, California

63. Zion National Park, Utah

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love my kid. He’s literally sitting here with me watching a silent hiking video with soothing music for an hour straight. Just some guy doing a hike from Inyo National forest to Kings Canyon National Park.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

RE-WRITING RWBY: F*CKING VACUO Part One.

Alright with the reveal of Vacuo and a "colonization arc" which made me facepalm so fucking hard. I might as well pull up my world-building pants and show up and show-out. So lets get fuckin' active.

(Art by Advarcher) Vacuo. Known to many around Remnant as the Kingdom That Embraces Freedom. This desert kingdom is the embodiment of Freedom of Expression. Showing that people can be happy here, aligned as one. Regardless of Gender, Sexuality, Race or Nationality. However beneath its surface the kingdom itself does hide a few secrets within the capital of Arthtar including a very much internalized hatred towards one of the kingdoms.

To start, during the Age of Antiquity. Vacuo was once a lush landscape filled with forests and life alike until its end came when Salem had led her uprising against the God of Light and Darkness ending Vacuo and sending it to what many survivors call it: The Age Of Sorrowful Darkness. Which many of the Great Mages of Vacuo had attempted to create or attempt to bring back any form of life what so ever. Only for it to fail...

Finally when all hope seemed lost, One of the Great Mages known as Arthtar would pour not just all of her magic but her very life force into a section of Vacuo thus spawning life. Even so the Titan of the Oasis' would also assist spawning many many Oasis' across the desert wasteland as a means of aid and succor, while the dust from the moon would hopefully bring the land back to what it once was.... or so many had thought.

Thus when Mantle had arrived to conquer Vacuo, did they open themselves up to their icy counterparts. Only to be met with flames of death and destruction. Despite this defense they were pushed back further and further to which the King of Vacuo called for aid from the recently defected Brumel and Vale for assistance to which they would answer the cry for assistance. Thus it was marked in the Great War as the Vacuan Offensive where many many battles took place and would birth Vacuo's elite guard. The Warriors Of Vacuo.

As many would fight and die, the King of Vacuo would go to meet with the Titan of Leadership and Justice in order to speak with them to grant permission for the Relic of Destruction. To which the Titan warned the King that should he use it they'd better be ready for the consequences to come... and thus desparate the King would use it during the Final Battle against the Mantleans which was in a stalemate currently.... thus...

It was remembered that day a GREAT CANYON was brought forth from that sword a canyon that irreversibly changed Vacuo... to which many call it the Badlands. Others call it a Kings Desperate Move.

However, even with such a great move the consequences to Vacuo did not end there. As many had died and the capital was damaged. To which those who survived the fighting stayed behind to help rebuild Arthtar to back into its glorious capital filled with flowing waters to represent the flow of time. Pathways leading to and from the desert representing the times of struggle and relief that comes with it, and lastly the very Capitol building of Samir Arthtar. Representing her brave sacrifice to bring back a piece of Vacuo's former glory.

Yet, even with the reparations Vacuo's damages were not done yet as years after companies would invade Vacuo for their dust supply, evicting many many tribes and families from their homes. Leaving the general public enraged most prominently the Schnee Dust Company as many Hunters disagreed with the SDC's motives for mining in Vacuo... others agreed with them.

Yet for a small section of Hunters they would not sit silently as the SDC took more and more from them. Thus the Great Dust Wars of Vacuo began against the entire kingdom of Vacuo and the Schnee Dust Company. Every bandit , hunter, or tribal warrior put aside their differences and agreed that a divided Vacuo is not a Free Vacuo. In which the war ended with a MASSIVE victory over their Atlesian counterparts who preferred order over freedom. Onto the very future while many do say that Vacuo has secrets for any researcher others wonder who is the REAL leader of Vacuo besides its Grand Councilman Theodore....

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roaring River Falls, Kings Canyon National Park

Explore:

#kings canyon#waterfalls#waterfall#travel#landscape#nature#original photography#wandering#lensblr#photography#photographers on tumblr#nature photography#california#wanderingjana

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

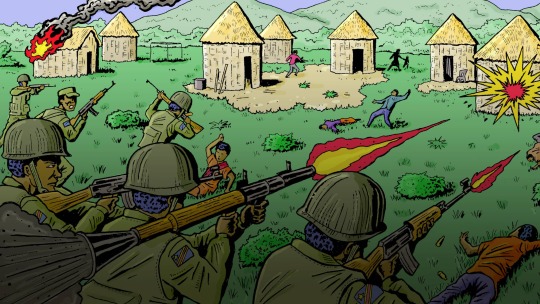

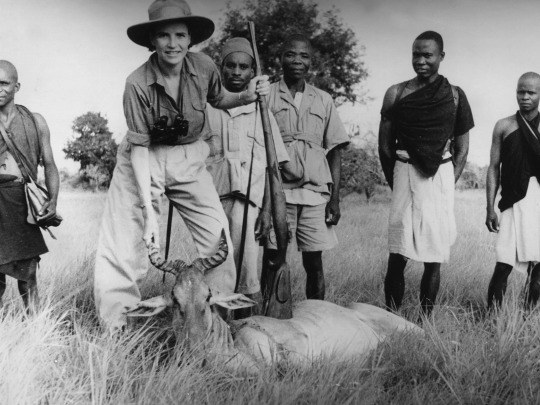

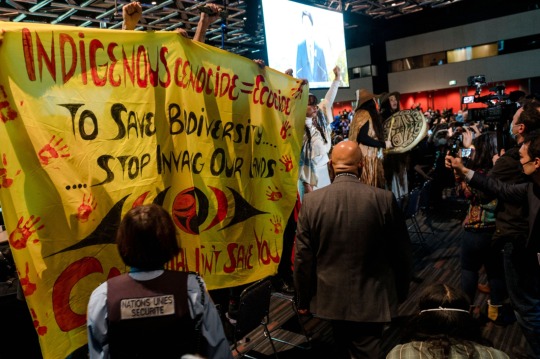

How the world’s favorite conservation model was built on colonial violence | Grist

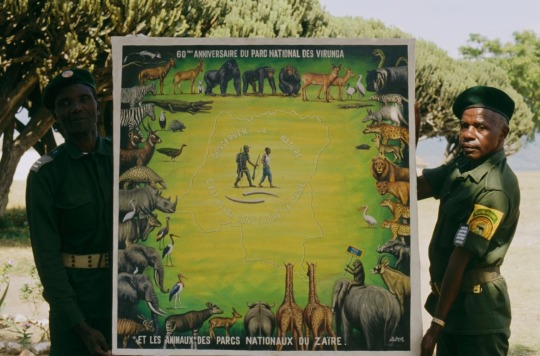

On a 1919 trip to the United States, King Albert I of Belgium visited three of the country’s national parks: Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the newly established Grand Canyon. The parks represented a model developed by the U.S. of creating protected national parks, where visitors and scientists could come to admire spectacular, unchanging natural beauty and wildlife. Impressed by the parks, King Albert created his own just a few years later: Albert National Park in the Belgian Congo, established in 1925.

Widely seen as the first national park in Africa, Albert National Park (now called Virunga National Park), was designed to be a place for scientific exploration and discovery, particularly around mountain gorillas. It also set the tone for decades of colonial protected parks in Africa. Although Belgian authorities claimed that the park was home to only a small group of Indigenous people — “300 or so, whom we like to preserve” — they violently expelled thousands of other Indigenous people from the area. The few hundred selected to remain in the park were seen as a valuable addition to the park’s wildlife rather than as actual people.

And so modern conservation in Africa began by separating nature from the people who lived in it. Since then, as the model has spread across the globe, inhabited protected areas have routinely led to the eviction of Indigenous peoples. Today, these conservation projects are led not by colonial governments but by nonprofit executives, large corporations, academics, and world leaders.

For much of human history, most people lived in rural areas, surrounded by nature and farmland. That all changed with the Industrial Revolution. By the end of the 19th century, European forests were vanishing, cities were growing, and Europeans felt increasingly disconnected from the natural world.

“With industrialization, the link with the natural cycle of things got lost — and that also led to a certain type of romanticization of nature, and a longing for a particular type of nature,” said Bram Büscher, a sociologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

In Africa, Europeans could experience that pure, untouched nature, even if it meant expelling the people living on it.

“The idea that land is best preserved when it’s protected away from humans is an imperialist ideology that has been imposed on Africans and other Indigenous people,” said Aby Sène-Harper, an environmental social scientist at Clemson University in South Carolina.

For Europeans, creating protected parks in Africa allowed them to expand their dominion over the continent and quench their thirst for “undisturbed” nature, all without threatening their ongoing expansion of industrialization and capitalism in their own countries. With each new national park came more evictions of Indigenous people, paving the way for trophy hunting, resource extraction, and anything else they wanted to do.

In the mid-19th century, European colonization of Africa was limited, largely confined to coastal regions. But by 1925, when King Albert created his park, Europeans controlled roughly 90 percent of the continent.

At the time, these parks were playgrounds for wealthy Europeans and part of a massive imperial campaign to control African land and resources. Today, there are thousands of protected national parks around the world covering millions of acres, ranging from small enclosures like Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis to sprawling landmarks like Death Valley in California and Kruger National Park in South Africa. And the world wants more.

Scientists, politicians, and conservationists are championing the protected-areas model, developed in the U.S. and perfected in Africa. In late 2022, at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal, nearly 200 countries signed an international pledge to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and waters by 2030, an effort known as 30×30 that would amount to the greatest expansion of protected areas in history.

So how did protected parks move from an imperial tool to an international solution for accelerating climate and biodiversity crises?

In the early part of the 20th century, the expansion of colonial conservation areas was humming along. From South Africa to Kenya and India, colonial governments were creating protected national parks. These parks provided a host of benefits to their creators. There were economic benefits, including extraction of resources on park land and tourism income from increasingly popular safaris and hunting expeditions. But most of all, the rapidly developing network of parks was a form of control.

“If you can sweep a lot of peasants and Indigenous peoples away from the lands, then it’s easier to colonize the land,” Büscher said.

This approach was enshrined by the 1933 International Conference for the Protection of the Fauna and Flora of Africa, which created one of the first international treaties, known as the London Convention, to protect wildlife. The convention was led by prominent trophy hunters, but it recommended that colonies restrict traditional African hunting practices.

“Conservation is an ideology. And this ideology is based on the idea that other human beings’ ways of life are wrong and are harming nature, that nature needs no human beings in order to be saved,” said Fiore Longo, a researcher and campaigner at Survival international, a nonprofit that advocates for Indigenous rights globally.

The London Convention also suggested national parks as a primary solution to preserve nature in Africa — and as many African countries saw the creation of their first national parks in the first half of the 20th century, the removal of Indigenous peoples continued. The convention was also an early sign that conservation was becoming a global task, rather than a collection of individual projects and parks.

This sense of collective responsibility only grew in the aftermath of World War II, when many international organizations and mechanisms, like the United Nations, were created, ushering in a new period of global cooperation. In 1948, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, or IUCN, the world’s first international organization devoted to nature conservation, was established. This would help pave the way for a new phase of international conservation trends.

By the middle of the 20th century, many countries in Africa were beginning to decolonize, becoming independent from the European powers that had controlled them for decades. Even as they lost their colonies, the imperial powers were not willing to let go of their protected parks. But at the same time, the IUCN was proving ineffective and underfunded. So in 1961, the World Wildlife Fund, or WWF, an international nonprofit, was founded by European conservationists to help fund global efforts to protect wildlife.

Sène-Harper said that although the newly independent African countries nominally controlled their national parks, many of them were run or supported by Western nonprofits like WWF.

“They’re trying to find more crafty ways to be able to extract without seeming so colonial about it, but it’s still an imperialist form of invasion,” she said.

Although these nonprofits have done important work in raising awareness of the extinction crisis, and have had some successes, experts say that the model of colonial conservation has not changed and has only made the problem worse.

Over the years, WWF and other nonprofits have helped fund violent campaigns against Indigenous peoples, from Nepal to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And amid it all, climate change continues to worsen and species continue to suffer.

In 2019, in response to allegations about murders and other human rights abuses, WWF conducted an independent review that found “no evidence that WWF staff directed, participated in, or encouraged any abuses.” The organization also said in a statement that “We feel deep and unreserved sorrow for those who have suffered. We are determined to do more to make communities’ voices heard, to have their rights respected, and to consistently advocate for governments to uphold their human rights obligations.”

“I think most of [the big NGOs] have become part of the problem rather than the solution, unfortunately,” Büscher said. “The extinction crisis is very real and urgent. But, nonetheless, the history of these organizations and their policies are incredibly contradictory.”

To Indigenous people who had already suffered from decades of colonial conservation policies, little changed with decolonization.

“When we got independence, we kept on the same policies and regulations,” said Mathew Bukhi Mabele, a conservation social scientist at the University of Dodoma in central Tanzania.

In 1992, representatives from around the world gathered in Rio De Janeiro for the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. The Earth Summit, as it has come to be known, led to the creation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as well as the Convention on Biological Diversity, two international treaties that committed to tackling climate change, biodiversity, and sustainable development.

Biodiversity is the umbrella term for all forms of life on Earth including plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi.

Although the Earth Summit was a pivotal moment in the global fight to protect the environment, some have criticized the decision to split climate change and biodiversity into separate conferences.

“It doesn’t make sense, actually, to separate out the two because when you get to the ground, these are going to be the same activities, the same approaches, the same programs, the same life plans for Indigenous people,” said Jennifer Tauli Corpuz, who is Kankana-ey Igorot from the Northern Philippines and one of the lead negotiators of the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity.

From left: The 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development, also known as the Earth Summit, brought together political leaders, diplomats, scientists, representatives of the media, and non-governmental organizations from 179 countries. Indigenous environmentalist Raoni Metuktire, a chief of the Kayapo people in Brazil, talks with an Earth Summit attendee.

In the years following the Earth Summit, biodiversity efforts began to lag behind climate action, Corpuz said.

Protecting animals was trendy during the early days of WWF, when images of pandas and elephants were key fundraising tactics. But as the impacts of climate change intensified, including more devastating storms, higher sea levels, and rising temperatures, biodiversity was struggling to gain as much attention.

“There were 100 times more resources being poured into climate change. It was more sexy, more charismatic, as an issue,” Corpuz said. “And now biodiversity wants a piece of the pie.”

But to get that, proponents of biodiversity needed to develop initiatives similar to the big goals coming out of climate conferences. For many conservation groups and scientists, the obvious solution was to fall back on what they had always done: create protected areas.

This time, however, they needed a global plan, so scientists were trying to calculate how much of the world they needed to protect. In 2010, nations set a goal of conserving 17 percent of the world’s land by 2020. Some scientists have supported protecting half the earth. Meanwhile, Indigenous groups have proposed protecting 80 percent of the Amazon by 2025.

How the world arrived at the 30×30 conservation model

Explore key moments in conservation’s global legacy, from the United States’ first national park in the 19th century to the expansion of colonial conservation areas in the early 20th century and the current push to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and oceans by 2030.

1872: Yellowstone becomes the first national park in the U.S.

1919: King Albert I of Belgium tours Yellowstone, Yosemite, and the Grand Canyon

1925: Albert National Park is established in the Belgian Congo

1933: One of the first international treaties to protect wildlife, known as the London Convention, is created by European conservationists

1948: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is established

1961: The World Wildlife Fund, a non-governmental organization, is founded by European conservationist

1992: The Earth Summit in Brazil creates the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

2010: CBD sets a goal of conserving 17% of the world’s land by 2020

2022: At the UN Biodiversity Conference, nearly 200 countries set 30×30 as an international goal

In 2019, Eric Dinerstein, formerly the chief scientist at WWF, and others wrote the Global Deal for Nature, a paper that proposed formally protecting 30 percent of the world by 2030 and 50 percent by 2050, calling it a “companion pact to the Paris Agreement.” Their 30×30 plan has since gained widespread international support.

But other experts, including some Indigenous leaders, say the idea ignores generations of effective Indigenous land management. At the time, there was limited scientific attention paid to Indigenous stewardship. Because of that, Indigenous leaders say they were largely ignored in the early years of international biodiversity negotiations.

“At the moment, we did not have a lot of evidence,” said Viviana Figueroa, who is Omaguaca-Kolla from Argentina and a member of the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity.

Some experts see the push for global protected areas as a direct response to community-based conservation, which grew in popularity in the 1980s, and saw local communities and Indigenous peoples take control of conservation projects in their area, rather than the centralized approach that had dominated during colonial times.

Some of the chief proponents of 30×30 bristle at the suggestion that they do not support Indigenous rights and say that Indigenous land management is at the heart of the initiative.

In response to a request for comment, a spokesperson from WWF pointed to its website, which outlines the organization’s approach to area-based conservation and its position on 30×30: “WWF supports the inclusion of a ‘30×30’ target in CBD’s post-2020 global biodiversity framework (GBF) only if certain conditions are met. For example, such a target must ensure social equity, good governance, and an inclusive approach that secures the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities to their land, freshwater, and seas.”

“People have cherry-picked a few examples of where the rights of locals have been tread upon. But by and large, in the vast majority of situations, what’s going on is support of local communities, really, rather than anything to do with violation,” said Dinerstein, who now works at Resolve, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit focused on environmental, social, and health issues.

But Indigenous advocates say if that were true, they would not keep pushing a model that has already led to countless human rights violations.

“Despite having this knowledge and knowing that people who are not contributing to the destruction of the environment are going to pay for these protected areas, they decided to keep on pushing the target,” Survival International’s Longo said.

The new 30×30 framework agreed to by nearly 200 countries at the UN Biodiversity Conference in December came after years of delay and fierce negotiation. The challenge is now implementing the agreement around the world, a massive task that will require buy-in from individual countries and their governments.

“What was adopted in Montreal is hugely ambitious. And it can only be achieved by a lot of hard work on the ground. And it’s a great document, but it is only a document,” said David Cooper, acting executive secretary of the UN’s Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Part of that work is figuring out what land to protect. And although Indigenous negotiators and advocates did manage to get language that enshrines Indigenous rights into the final agreement, they are still concerned. Over a century of colonial conservation has shown that it only serves the powerful at the expense of Indigenous peoples.

“European countries are not going to evict white people from their lands,” said Longo. “That is for sure. This is where you see all the racism around this. Because they know how these targets will be applied in Africa and Asia. That’s what’s going on, they are evicting the people.”

Dinerstein, however, would argue that European countries have less natural resources to preserve, but more financial resources to help other countries.

“There’s a lot that can be done in Europe,” he said. “So we shouldn’t overlook that as well. I’m just making the point that there’s the opportunity to be able to do much more in other countries that have much less resources.”

Cooper said that in addition to implementation, monitoring and ensuring that rights are upheld will be a crucial task over the next seven years. “There will need to be a lot of work on monitoring. There’s always a justified nervousness that any global process cannot really see what’s happening at the local level and can end up with supporting measures that are perhaps not beneficial at the local level,” he said.

Although Indigenous leaders are going to keep fighting to ensure that the expansion of protected areas does not lead to continued violation of their rights, they are worried that the model itself is flawed. “It’s inevitable that the burden is going to fall again on developing countries,” Corpuz said.

#colonial violence#languages#How the world’s favorite conservation model was built on colonial violence#colonialism#brazil#indigenous populations#Yanomami#bolsanaro#the amazon#amazon rainforest#natural resources#ecology

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forester Pass from the north, in the southeast corner of Kings Canyon National Park on May 22, 2022

#hiking#backpacking#trekking#mountains#pacific crest trail#pct#john muir trail#jmt#sierra nevada#kings canyon national park#national parks#photography#shot on iphone

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Centuries-old cypresses, planted by royal decree, still line miles of the Shu Roads in the lush hills of northern Sichuan. The roads were built about the same time as the Romans built the Appian Way. Photograph By Paul Salopek

This Ancient Marvel Rivaled Rome’s Intricate Network of Roads

Remnant slabs of stone laid more than 2,000 years ago pave forgotten trade and military byways across the mountains that divide northern and southern China.

— By Paul Salopek | Aril 21, 2023

Sword Gate Pass, Sichuan Provence, China“Over there!”

Discovery: For a decade, National Geographic Explorer Paul Salopek (Pictured above) has been walking the routes of human civilization worldwide. Now in China, he has stumbled upon remnants of an ancient network of roads. “They unspool like gigantic question marks over miles of jagged landscape,” he writes. Photograph By John Stanmeyer, National Geographic Image Collection

It is my walking partner Li Huipu. Li points to a line of cypresses near a highway that booms with the inescapable red cargo trucks of China. (All of modern China is a construction site.) A few miles farther on, she peers down from a concrete bridge into a steep, rainy mountain gorge. “It’s down there!” she calls out again. “See it?” She is a resourceful hunter. She a woman of Shu.

We are stalking the old Shu Roads.

What are Shu Roads—the Shǔdào?

They are squared slabs of stone—of slate? of granite?—about the size of small tabletops. Placed by hand in times long past, and numbering perhaps in the millions, they pave forgotten byways that cross the mountains dividing northern from southern China. Antique but sturdy paths. They unspool like gigantic question marks over miles of jagged landscape. They start and stop and fade into shadowed forests. Time machines. Broken mazes plied by phantoms. Sparse and solitary and moving. We try to walk them, Li and I, through the uplands of Sichuan Province.

In this way, we hopscotch through centuries. We skip between the chaos of the Warring States Period in Chinese history, circa the fourth-century B.C., and the distractions of the dynasty of TikTok.

Builders of the Shu Roads in Shaanxi Province confronted jagged obstacles such as Mount Hua Shan. Photograph By Tao Ming, Xinhua/Getty Images

The laying of the Shu Roads began when the Romans built the Appian Way—some 2,300 years ago—and for the same purposes: military control and trade. The vast Eastern Zhou empire was cracking apart. A subject kingdom called Qin, occupying much of modern-day Shaanxi Province, rose to power. It pushed new roads across the 12,000-foot Qin Mountains to attack a wealthy southern rival—the kingdom of Shu—centered in today’s Sichuan. Rich in salt, silk and iron, Shu expanded its own roads to better defend its mountain frontiers. But Shu lost in 316 B.C. And all these stone-paved roads, improved with post offices and caravan stops, became arteries of imperial integration. This was when China’s center of gravity lay in the highlands of the west, and not (as today) in the hot, low plains and cities of the east.

A hundred generations of traders commuted along the Shu Roads. They pushed “wooden oxen”—wheelbarrows. Armies fitted in leather armor marched atop the branching network of flagstones. Sometimes, they torched wooden sections of the road—miles of extraordinary plank walkways suspended from canyon walls—as they retreated. Farmers hustled their goods along the roads. (One segment was called the Lychee Road, dedicated to a royal concubine’s fondness of the fruit.) Poets and sages walked the roads. So did deposed kings, refugees, addled foreigners, and elderly farm women tacking against gravity under bundles of firewood. (A few last of these still walk the trails today.) In China’s relict wild mountains, giant pandas, red pandas, gnu-like takin, and six-foot salamanders also prowl the Shu Roads. Today these weedy paths go mostly nowhere.

A reconstruction of plank roads—an engineering feat more than two millennia old—hangs above Mingyue Gorge, in Sichuan Province. Photograph By Paul Salopek

We Start Our Trek in Li’s hometown, Chengdu, the ancient capital of Shu and the southern pole of the Shu Roads. Today it is a megalopolis of 16 million set in the lush Sichuan Basin. (This agricultural zone is exalted in classical Chinese literature as Tiānfǔ zhi Guó—the "Country of Heaven.") Li walks me by her childhood apartment. By her primary school. (“It’s much smaller than I remember.”) By the first McDonald’s in her neighborhood. She points out newer layers of Chinese franchises including Mixue Bincheng, a low-market bubble tea outlet launched with a $438 loan from the founder’s grandmother and now a billion-dollar company whose mascot, a rotund snowman, sings “I love you, you love me, Mixue Bincheng sweety!” to the public domain melody of “Oh! Susannah,” the minstrel song composed by Pennsylvanian Stephen Collins Foster in 1848.

Left: Eighth-century poet Du Fu spent years wandering the Shu Roads. Illustration Via Pictures From History, Bridgeman Images Right: Map

The Shu Roads welded north to south China. They also became tangents of longing. They delivered art. In the eighth century, Du Fu, a titan of the gilded age of Chinese classical poetry, survived on boiled tree leaves in a hut in Chengdu. Exhausted from escaping rebellions, constant joblessness, and years of itinerant wanderings along pitiless Shu Roads, Du Fu mocked his so-called-poet’s life:

Far from the market, my food has little taste,

My poor home can offer only stale and cloudy wine.

Consent to have a drink with my elderly neighbour,

At the fence I'll call him, then we'll finish it off.

His contemporary, the traveling bard Li Bai, lamented his journey into exile along the slippery roads up the Qinglin Mountains:

The Shu Road is as perilous and difficult as the way to the Green Heavens.

The ruddy faces of those who hear the story of it turn pale.

There is not a cubit's space between the mountain tops and the sky.

In Chengdu, the Shu Roads dream mutely under asphalt. Li and I hike toward their northern terminus some 400 miles away, to Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi Province.

— Tracing 2,000-year-old byways through rugged terrain in western China.

vimeo

Near Minyang we cross the ghostly path of a British traveler in a long Manchurian dress.

Sometimes Isabella Bird walked. Sometimes Bird rode a chair hauled by laborers who cushioned their aches with opium.

“A thousand years ago it must have been a noble work,” the British traveler wrote of a still-bustling Shu Road in The Yangtze Valley and Beyond, a record of her travels in western China in 1897. “It is nominally sixteen feet wide, the actual flagged roadway measuring eight feet. The bridges are built solidly of stone. The ascents and descents are made by stone stairs. More than a millennium ago an emperor planted cedars at measured distances on both sides, the beautiful red-stemmed, weeping cedar of the province . . . Each tree bears the imperial seal and the district magistrates count them annually.”

They still do.

To locate old Shu Roads, Li and I seek out colonnades of big trees linking village guesthouses and gritty truck stops. They aren’t cedars. They are cypresses (Cupressus). A few are 800 or more years old, and each one is tagged by the Sichuan reforestation bureau. In the wet mists of Sichuan their massive black boughs drip their own rain.

Isabella Bird wrote sympathetically of rural Chinese. She did complain about the 19th-century bureaucracy. Qing Dynasty officials demanded her passport every few miles, she grumbled, copying her particulars on clipboards of slate. This also still happens. At Wulian, an empty inn cannot host us. They aren’t registered to receive foreigners. Two police drive us to their station. They help us fill out the necessary paperwork.

“Why are you walking?” the older cop asks, skeptically.

“It's a walking project,” the younger cop reminds him. He rolls his eyes at his square partner. “It’s about walking.”

Marco Polo may have paced off Shu Roads in the 13th century. He supposedly journeyed from Beijing to Chengdu: “Having traveled those twenty stages through a mountainous country, you reach a plain on the borders of Manzi . . . where you see many fine mansions, castles, and small towns. The inhabitants live by agriculture. In the city there are factories, particularly of very fine cloths and crapes or gauzes.”

The first and only empress of China, the supremely brilliant and capably ruthless Wu Zetian, may or may not have been born on a Shu Road five centuries earlier. The northern Sichuanese city of Guangyuan claims her in any case. Its museum of mannequins celebrates the world’s “top 10 queens.”

We trudge on, Li Huipu and I. Stone paths scalloped by the hooves of long-dead pack horses point us north through dozy river towns and hamlets of geriatric farmers. Local place names contain characters for the words yi (post station) and pu (market station), suggesting waypoints along a great, dissolving road system of antiquity.

At Sword Gate Pass, we climb a Shu kingdom fortress so famed it has spawned its own Chinese proverb: “One man at the pass keeps 10,000 at bay.” Standing at the summit, I scan the green hills once again for telltale lines of cypresses, knowing that the world they once shaded came undone a century or more ago because no fierce battlements could keep out the whine of a car, or the thin wire of the telegraph.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weather: Pacific Northwest

Report generated at 2025-01-06 00:00:08.082701-08:00 using satellite imagery and alert data provided by the National Weather Service.

Dense Fog Advisory

WA:

Foothills of the Blue Mountains of Washington

OR:

Foothills of the Northern Blue Mountains of Oregon

Foothills of the Southern Blue Mountains of Oregon

North Central Oregon

Freezing Fog Advisory

WA:

Kittitas Valley

Beach Hazards Statement

OR:

Curry County Coast

South Central Oregon Coast

CA:

Coastal Del Norte

Coastal North Bay Including Point Reyes National Seashore

Mendocino Coast

Northern Humboldt Coast

Northern Monterey Bay

San Francisco

San Francisco Peninsula Coast

Southern Monterey Bay and Big Sur Coast

Southwestern Humboldt

Flood Warning

OR:

Coos

Winter Weather Advisory

ID:

Bear River Range

Southern Clearwater Mountains

NV:

Northern Elko County

Ruby Mountains and East Humboldt Range

Wind Advisory

CA:

Indian Wells Valley

Kaiser to Rodgers Ridge

Kings Canyon NP

Mojave Desert

Mojave Desert Slopes

Northeast Foothills/Sacramento Valley

San Joaquin River Canyon

Sequoia NP

South End of the Upper Sierra

Upper San Joaquin River

West Slope Northern Sierra Nevada

Western Plumas County/Lassen Park

Yosemite NP outside of the valley

High Surf Advisory

CA:

San Luis Obispo County Beaches

Santa Barbara County Central Coast Beaches

Ventura County Beaches

High Wind Watch

CA:

Central Ventura County Valleys

Lake Casitas

Lake Havasu and Fort Mohave

Lake Mead National Recreation Area

Los Angeles County Beaches

Los Angeles County Inland Coast including Downtown Los Angeles

Malibu Coast

Northern Ventura County Mountains

Ojai Valley

Orange County Inland

Palos Verdes Hills

Riverside County Mountains

San Bernardino County Mountains

San Bernardino County-Upper Colorado River Valley

San Bernardino and Riverside County Valleys-The Inland Empire

San Diego County Inland Valleys

San Diego County Mountains

San Gorgonio Pass Near Banning

Santa Ana Mountains and Foothills

Southern Ventura County Mountains

Ventura County Beaches

Ventura County Inland Coast

NV:

Lake Havasu and Fort Mohave

Lake Mead National Recreation Area

San Bernardino County-Upper Colorado River Valley

Fire Weather Watch

CA:

Calabasas and Agoura Hills

Catalina and Santa Barbara Islands

Central Ventura County Valleys

Eastern San Fernando Valley

Eastern San Gabriel Mountains

Eastern Santa Monica Mountains Recreational Area

Interstate 5 Corridor

Los Angeles County Beaches

Los Angeles County Inland Coast including Downtown Los Angeles

Los Angeles County San Gabriel Valley

Malibu Coast

Northern Ventura County Mountains

Orange County Inland

Palos Verdes Hills

Riverside County Mountains-Including The San Jacinto Ranger District Of The San Bernardino National Forest

San Bernardino County Mountains-Including The Mountain Top And Front Country Ranger Districts Of The San Bernardino National Forest

San Bernardino and Riverside County Valleys - The Inland Empire

San Diego County Inland Valleys

San Diego County Mountains-Including The Palomar And Descanso Ranger Districts of the Cleveland National Forest

San Gorgonio Pass Near Banning

Santa Ana Mountains-Including The Trabuco Ranger District of the Cleveland National Forest

Santa Clarita Valley

Santa Susana Mountains

Southeastern Ventura County Valleys

Southern Ventura County Mountains

Ventura County Beaches

Ventura County Inland Coast

Western San Fernando Valley

Western San Gabriel Mountains and Highway 14 Corridor

Western Santa Monica Mountains Recreational Area

Red Flag Warning

CA:

Calabasas and Agoura Hills

Central Ventura County Valleys

Eastern San Fernando Valley

Eastern San Gabriel Mountains

Eastern Santa Monica Mountains Recreational Area

Interstate 5 Corridor

Los Angeles County San Gabriel Valley

Malibu Coast

Santa Clarita Valley

Santa Susana Mountains

Southeastern Ventura County Valleys

Southern Ventura County Mountains

Western San Fernando Valley

Western San Gabriel Mountains and Highway 14 Corridor

Western Santa Monica Mountains Recreational Area

High Wind Warning

CA:

Calabasas and Agoura Hills

Eastern San Fernando Valley

Eastern San Gabriel Mountains

Eastern Santa Monica Mountains Recreational Area

Interstate 5 Corridor

Los Angeles County San Gabriel Valley

Santa Clarita Valley

Santa Susana Mountains

Southeastern Ventura County Valleys

Western San Fernando Valley

Western San Gabriel Mountains and Highway 14 Corridor

Western Santa Monica Mountains Recreational Area

Air Quality Alert

CA:

Calabasas and Agoura Hills

Catalina and Santa Barbara Islands

Eastern San Fernando Valley

Eastern Santa Monica Mountains Recreational Area

Los Angeles County Beaches

Los Angeles County Inland Coast including Downtown Los Angeles

Los Angeles County San Gabriel Valley

Malibu Coast

Orange County Coastal

Orange County Inland

Palos Verdes Hills

Riverside County Mountains

San Bernardino County Mountains

San Bernardino and Riverside County Valleys-The Inland Empire

San Gorgonio Pass Near Banning

Santa Clarita Valley

Santa Susana Mountains

Western San Fernando Valley

Western Santa Monica Mountains Recreational Area

0 notes

Text

The largest trees in the world are found in California's Sierra Nevada mountains, in the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. The giant sequoias in this area, specifically in the Giant Forest, are the world's most massive trees by volume.

The General Sherman Tree, located in the Giant Forest of Sequoia National Park, holds the title of the largest tree on Earth. It stands about 275 feet tall and is over 36 feet in diameter at the base.

These ancient giants are not just impressive in size but also in age, with some sequoias estimated to be over 3,000 years old. If you ever have a chance to visit, it's a truly awe-inspiring experience! 🌲

0 notes