#kevin huvane

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

81st annual Golden Globe Award

Meryl Streep poses at the Ballroom entrance of the 81st annual Golden Globe Awards at The Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills, California, on January 7, 2024.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kevin Huvane & Meryl Streep on the Red Carpet at the Golden Globes on January 7th, 2024.

#Kevin Huvane#Meryl Streep#Golden Globes 2024#Red Carpet#Golden Globes#January 7th 2024#The Beverly Hilton

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

🕯️ PART I: The Party That Should’ve Ended It All

How Creative Artists Agency’s 2013 Sundance bash blew the lid off Hollywood’s darkest machinery, and everyone just looked away.

---

🎭 The Moment That Was Too Loud to Ignore

January 2013, Park City, Utah. The Sundance Film Festival, a playground for Hollywood’s elite and dreamers alike. Amid the snow and indie premieres, the most powerful talent agency on the planet, Creative Artists Agency (CAA), decided to host a party at the Claim Jumper steakhouse. A supposedly exclusive, VIP night meant to impress clients, producers, and the press.

What happened was something else entirely.

Guests expecting polite mingling and scripted smiles instead found themselves trapped in a shockingly explicit sex-themed cabaret, courtesy of Simon Hammerstein’s burlesque troupe, The Act. Far from subtle, the show pushed the envelope. No, it ripped the envelope apart. It was raw, confrontational, and deeply unsettling.

---

🔥 What Went Down: A Parade of Depravity

Eyewitnesses reported:

A man on stilts, costumed as a giant rabbit, wearing a strap-on dildo (no joke).

A woman dressed as Alice in Wonderland, simulating sexual acts with said rabbit, in full view of the crowd.

Performers snorting fake cocaine off mirrors, grinding on guests, moaning audibly, and indulging in highly sexualized, public acts.

A woman licking the rabbit’s dildo as shocked attendees tried to continue networking.

Industry insiders pitching projects as if this was all normal.

This was not some side-show corner. It was immersive. Unescapable. And everyone was expected to participate: silently, or face professional repercussions.

---

😳 How People Reacted: Horror, Confusion, Silence

Naomi Foner, respected screenwriter and mother to Maggie and Jake Gyllenhaal, was blunt:

“I said to my agent, ‘Is this how you want to brand yourself? Pole dancers? Really?’” Source: LA Times

Oscar-winning writer Nat Faxon described the struggle of having “a conversation about my movie while that was going on right next to you.”

Guests like Stephanie Cregger called it “very creepy,” the kind of weirdness that sends a shiver down your spine, not a laugh.

And then there’s Nicole Kidman, a powerhouse actress and major CAA client, who fled the party, saying:

“I think I prefer it out here.” Page Six

If Nicole Kidman wanted out, that says everything.

---

🧻 The PR Spin: Corporate Gaslighting at Its Finest

CAA’s official response?

“The performance was more explicit than intended. We regret if this created an uncomfortable setting.” — The Independent

No apology. No named accountability. No promise of change. Just a corporate shrug, a vague regret, and a hope this blows over.

They did not own the decision to hire a Vegas burlesque act known for NSFW performances. They didn’t express remorse for the victims of trauma and abuse forced to attend this “party.” They simply minimized and moved on.

---

👤 Chris Andrews: The Silent Witness and Promoted Player

Agent Chris Andrews was there, front and center, watching it all unfold. No intervention. No walkout. Just cold, calculating silence.

And here’s the kicker: he would later become the agent of Sebastian Stan, whose public image is meticulously controlled and sanitized, a stark contrast to the chaos witnessed in 2013.

The PR machinery behind Sebastian’s pandemic-era “Covid Barbie” mess, featuring strategically timed relationships, pap walks, and damage control, all trace back to Andrews. We’ll unravel that mess in Part VI: The PR Relationship Industrial Complex™. Trust me, it’s a labyrinth of spin and manipulation.

🍷 And Then: Enter Harvey Weinstein

Harvey Weinstein himself attended the party, mingling, laughing, chatting with CAA heavyweights like Chris Andrews and Kevin Huvane.

This was years after multiple women had reported his predatory behavior to agents. Years after Mia Kirshner had been assaulted and told by her agent Lisa Grode to “forget about it.” Years after multiple warnings that should have stopped him in his tracks.

Yet here he was, a guest of honor.

“At CAA, at least eight talent agents were told that Mr. Weinstein had harassed or menaced female clients, but agents there continued to arrange private meetings.” — New York Times 2017

This was no secret. It was a deliberate choice to protect power over people.

---

🧠 Why This Matters

This party was not an isolated incident. It was a symptom of an industry-wide sickness: rape culture packaged as networking, performance, and “business as usual.”

CAA invited clients, many young, many vulnerable, into a space soaked in sexual degradation and coercion.

The message was clear:

Shut up.

Smile.

Network.

Or be erased.

The rabbit with the strap-on wasn’t the scandal. The culture of silence was.

---

🧷 TL;DR: The Night That Should’ve Broken Hollywood

WHAT: CAA’s 2013 Sundance party featured explicit sexual acts and burlesque performances.

WHO: Kevin Huvane, Chris Andrews, Nicole Kidman, and Harvey Weinstein were all there.

REACTION: Horror and disgust. High-profile guests like Nicole Kidman fled the venue.

ACCOUNTABILITY: None. CAA only issued a vague “regret” statement without taking responsibility.

MEANING: CAA didn’t just ignore abuse; they celebrated and normalized it on a gilded platter.

---

📸 The Photos

Only a few images slipped online (what Just Jared was allowed to show.) The rest? Locked away deep in CAA’s vaults, alongside the skeletons no one dares to drag into the light.

---

✍️ FINAL WORD

The casting couch got a costume change. That’s all. This was rape culture with choreography. And the industry? It applauded, poured another drink, and asked who you were repped by.

---

⏭️ NEXT:

PART II: Weinstein & the Enablers

Where we go from strap-ons to settlements. From agents silencing survivors to actresses being funneled straight into hotel rooms with a smile and a death sentence. CAA knew. Everyone knew. And no one stopped him.

#CAA#Harvey Weinstein#Chris Andrews#annabelle wallis#Sebastian Stan#alejandra onieva#Creative Artists Agency#sebastianstan#annabellewallis#alejandraonieva#pr relationships#PR Romances#Fake Couples

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

ᴛʜᴇ ᴍᴇɴᴛᴏʀꜱ ᴏꜰ ꜰᴀʏᴇ ɴᴏʟᴀɴ (aka my mentors in my fame dr)

with how much success faye nolan saw at a young age, it’s shocking yet relieving that she is never part of the dreaded “child star” conversations. part of it came from her parents, who always insisted that they or one of faye’s older siblings accompany her to sets, interviews, or events. the other came from well-known individuals in the industry who took it upon themselves to look out for the rising star, professionally and personally.

⋙ Robin Williams played the grandfather drosselmeyer to faye’s clara in a film adaptation of the nutcracker when she was just 12 years old, and the dynamic they shared on screen translated to real life. he would ease the still green actress’s nerves on set with his classic rapid-fire humor, even doing his famous genie lines. he remained a close figure in her life as she grew up. (storykeeper’s edit: in my dr he DOES NOT HAVE LBD. NOT HAPPENING. MY BABY WILL NOT SUFFER.) sometimes he would even volunteer himself to accompany her to an industry party when she was still a teenager to look after her and offer any connections he had.

⋙ Jason Isaacs would call faye a little sponge whenever he was asked about working with her on peter pan. he served as a liaison of sorts between the adult crew and inexperienced child actors — translating directions into things they could understand. faye took any and every crumb of acting wisdom he inadvertently bestowed upon her and her costars in stride. he helped her overcome the steep learning curve of on-set etiquette on a production as large as peter pan. faye would oftentimes come to him at various moments throughout her career seeking advice or insight on how to approach different roles and opportunities.

⋙ Tom Hanks met faye when she was 14 at the 2006 golden globes when she was nominated for (& won) the award for best actress in a motion picture - musical/comedy for her role in the film placeholder. he became a warm, paternal figure who (like williams) who was a comforting presence at the increasing number of industry events the young actress was expected to attend to further her career.

⋙ Dolly Parton and faye met through both her friendships with miley cyrus and taylor swift. she offered unforgettable advice when it came to advocating for herself (that granted faye didn’t necessarily listen until after her hiatus) & staying true to her songwriting when the actress was making her mark on the music industry.

⋙ Julia Roberts described the 12 year-old faye that she met at the world premiere of peter pan in december 2003 as “the cutest thing who’s gonna go far.” they were both managed by kevin huvane at CAA, and the iconic actress took the budding starlet under her wing. roberts was the one who taught faye how to move through the industry with grace while protecting her peace. when the inevitable gossip and slut shaming that is always thrown at young women in hollywood began to rain upon a teenage faye, roberts helped her cope and navigate through it with her head held high.

xo, 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐒𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲𝐤𝐞𝐞𝐩𝐞𝐫

#shifting#reality shifter#shifting blog#shifting realities#reality shifting#rosebudshifter#shifters#shifting community#shiftblr#shifting motivation#rosebud's fame dr#fame dr#fame desired reality#actress dr#actress desired reality#storytime

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

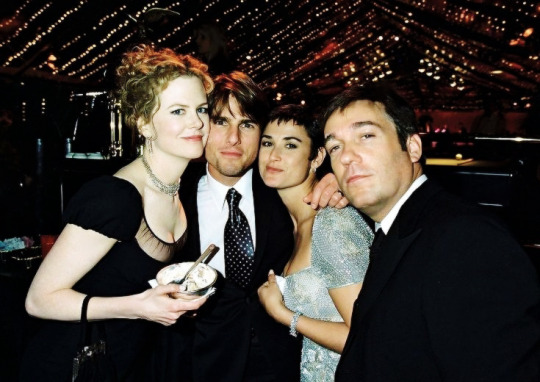

Nicole Kidman, Tom Cruise, Demi Moore and Kevin Huvane, 1997

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

CAA Sells Majority Stake to Francois-Henri Pinault’s Artemis

French billionaire Francois-Henri Pinault has successfully concluded his acquisition of a controlling interest in Creative Artists Agency (CAA). This significant move, executed through his family investment firm Artemis, positions Pinault to replace private equity firm TPG as the primary owner of one of Hollywood’s two major talent agencies.

Creative Artists Agency, renowned for its diversified services that broker deals for clients ranging from Tom Cruise to popular children’s toy brand Squish mallows, is now a part of Artemis’ extensive $40 billion asset portfolio. Artemis already boasts a remarkable array of holdings, including Kering, a luxury goods conglomerate encompassing prestigious brands like Gucci and Saint Laurent, as well as Christie’s auction house and Château Latour winery. While the transaction is still pending completion, it is set to value CAA as a whole at $7 billion. The precise extent of Artemis’ ownership stake remains undisclosed, but it is clear that they will hold a substantial majority share.

Global presence and Diverse Resources

In an official announcement, Creative Artists Agency ‘s current leadership triumvirate of Bryan Lourd, Kevin Huvane, and Richard Lovett have committed to retaining their positions within the company. The specific terms of their continued leadership were not immediately disclosed, but it has been confirmed that Bryan Lourd will assume the role of CEO following the closure of the Artemis transaction, the timeline for which remains unspecified. Jim Burton, who spearheaded the CAA deal, will continue to serve as the President of CAA.

In a joint statement, Lourd, Lovett, Huvane, and Burtson expressed their appreciation and admiration for Pinault and his team leaders Héloïse Temple-Boyer and Alban Greget. They praised Artemis as a strategic investor with a global presence and diverse resources across various areas that align with their clients’ interests. Additionally, they highlighted Artemis’ profound understanding of global brands and their growth support, coupled with a shared passion for creativity and innovation. The statement also acknowledged TPG for their strategic expertise, invaluable support, and enduring collaboration over the past 13 years, expressing a commitment to continuing their collaborative efforts on future projects.

The strategic move enables Creative Artists Agency to directly engage in European film

The decision to appoint Lourd as CEO aligns Creative Artists Agency with the organizational structure observed in other Artemis-affiliated companies. Lourd has consistently demonstrated his prowess in the industry over the past two decades, earning respect from both talent and management circles. Importantly, amidst the increasing speculation surrounding the Artemis deal in recent weeks, Lourd, Lovett, and Huvane have made it clear that they are committed to maintaining active involvement in the day-to-day affairs of their longstanding clients as hands-on agents, in addition to their leadership and managerial responsibilities.

This partnership between CAA and Artemis not only brings Kering’s renowned brands closer to the entertainment sector but also provides CAA with a significant presence in France. This strategic move enables Creative Artists Agency to directly engage in European film and television production. On the other hand, Kering has already made substantial strides in the film industry in recent years, cementing its status as a major sponsor of the Cannes Film Festival and launching the Women in Motion program, which celebrates inspiring female actors, filmmakers, and producers. It’s worth noting that Pinault, the driving force behind this venture, is married to actor Salma Hayek, a longstanding client of CAA.

Also read: Build Strength in your Business through Stakeholder Engagement

#creativeagency#branding#marketing#graphicdesign#digitalmarketing#creative#design#digitalagency#advertising#socialmediamarketing#marketingagency#socialmedia#webdesign#agencylife

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

CAA's Kevin Huvane Honors Late Brother With Project Angel Food Donation

An emotional and uplifting scene unfolded in front of CAA‘s Century City headquarters on Monday as power agent and co-chairman Kevin Huvane teamed with Project Angel Food to honor his late brother Chris Huvane. The ceremony — attended by CAA insiders, Chris Huvane’s colleagues at Entertainment 360, Project Angel Food CEO Richard Ayoub and Huvane family members — saw the unveiling a new white van…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Carlos Lopez, Kelly Sawyer, and Nicole Richie at a Pride Month celebration hosted by Carlos Eric Lopez, Kevin Huvan, and the Creative Artist Agency team in Los Angeles on May 30th, 2024.

0 notes

Text

Francois-Henri Pinault nears $7B deal for Hollywood talent agency CAA | Fortune

FINANCE HOLLYWOOD

French luxury billionaire nears $7 billion deal for Hollywood talent giant CAA, home to Brad Pitt

Francois-Henri Pinault is pursuing Creative Artists Agency, which also represents his wife, Salma Hayek.

BY LUCAS SHAW , KAMARON LEACH , AND BLOOMBERG

August 31, 2023 1:09 PM EDT

François-Henri Pinault and Salma Hayek Pinault attend the Kering Women In Motion Awards during the Kering and Cannes Film Festival Official Dinner on May 21, 2023 in Cannes, France. Anthony Ghnassia—Getty Images for Kering

French billionaire Francois-Henri Pinault is close to a $7 billion deal to buy a majority stake in Creative Artists Agency, the Hollywood talent giant that’s home to actor Brad Pitt and basketball’s Chris Paul, according to people familiar with the matter.

Pinault, whose family controls a luxury goods empire, is seeking the majority stake held by private equity firm TPG Inc., said the people, who asked not to be identified because the deal hasn’t been announced. Temasek Holdings Pte, the Singapore government’s investment firm, may also increase its stake in CAA by buying out China’s CMC Capital, the people said. While the deal could fall apart, the parties are expected to conclude negotiations in the next couple weeks.

The $7 billion valuation of CAA marks an increase from the $5.5 billion placed on the business last year when it acquired rival agency ICM Partners. Pinault, 61, is seeking one of Hollywood’s most stable and powerful institutions at a challenging time for media deals. Valuations of most media companies have slipped due to the collapse of pay TV, rising interest rates and strikes by writers and actors.

Yet the Pinault family sees CAA as a way to invest in the value of celebrities, and may be able to use some of those famous faces to bolster its other businesses. The family is the biggest shareholder in Kering SA, the owner of Gucci and other luxury brands. The Pinaults also control the auction house Christie’s and wineries via a holding company. Pinault’s wife, actress Salma Hayek, is represented by CAA.

Founded in 1975 by partners including Michael Ovitz and Ron Meyer, CAA has grown into the largest agency in Hollywood. It’s a top representative of actors, directors, writers, producers, athletes and musicians. Bryan Lourd, Kevin Huvane and Richard Lovett have run the agency since the mid-1990s when they were known as young turks. All three are expected to remain with the company.

Major Hollywood talent agencies have all raised money over the last decade to expand into new businesses. Endeavor Group Holdings Inc. has been the most aggressive, buying Ultimate Fighting Championship, Professional Bull Riders and, most recently, World Wrestling Entertainment Inc. Its talent agency, WME, now accounts for about a third of sales and profit. United Talent Agency, the third-largest firm, sold a stake to Swedish private equity firm EQT AB last year.

Rumors about CAA’s future have swirled for years because private equity firms don’t typically own companies for years and years. TPG first invested in CAA back in 2010 and acquired a majority stake in 2014. CAA hasn’t expanded as aggressively as Endeavor. It has focused on its core talent representation, as well as corporate consulting. It built one of the largest sports agencies in the world.

As part of the deal, the company may give agents with equity the chance to sell a small portion of their shares, according to the people, and will ask a select number to sign new contracts that will keep them at the firm for the next few years.

Ben...JUMP!

0 notes

Photo

Halle Berry, Kevin Huvane, Spike Lee, Ciara & Russell Wilson

Vanity Fair Oscar Party in Los Angeles 03/04/2018

https://www.facebook.com/Inspirationlovephotographycamera/

https://www.instagram.com/inspirationlovephotography

#halle berry#kevin huvane#spike lee#ciara#russell wilson#actress#aktorka#celebrities#celebrity#famous#famous people#zuhair murad#dress#short dress#red dress#vanity fair oscar party#vanity fair#los angeles#event#mycolage#mycolagemadzix6#inspiration#hotornotinspirationlovephotography#vanity fair oscar party 2018#hot or not#hotornot

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fan Question-and-Answer With Brad Silberling (The Director of the 2004 Lemony Snicket Movie)

1) How did you first become involved with the project after Barry Sonnenfeld had departed it? How different was his approach to yours in terms of the tone and overall plot? How much time did you have to prep your vision? I was in London in February of 2003 with Dustin Hoffman, promoting my film Moonlight Mile when I got a call from Walter Parkes at DreamWorks, asking if I was familiar with the Lemony Snicket series. I certainly was familiar with the growing phenomenon but I hadn't actually read the books. So I dashed off to Hamleys (which is a fantastic toy store in London) picked up the first 3 books and was immediately hooked and that began, for me, the two-year journey with the movie.

What everybody needs to understand is that the film Scott Rudin was producing and Barry Sonnenfeld was directing, was an exclusive production of Paramount's. I think what happened was that over the course of the budget growing and growing, which it had, Paramount decided to reach out for a studio partner and they reached out to DreamWorks. That meant that Walter Parkes and Laurie MacDonald (who were running DreamWorks for Steven Spielberg) would also then be coming on in a creative producing capacity. That was not acceptable to Scott Rudin and he stepped off immediately and Barry Sonnenfeld (who had not let the Men in Black 2 experience with Walter Parkes and Laurie McDonald on a great note) and so he essentially stepped off before he would have been shoved off. And was probably wise to do so. There was an existing script that I saw, as I told them with tremendous excitement that I very much wanted to do the picture. Daniel had written the adaptation and what was immediately apparent to me was that (as can happen for an author) I think he'd been so steeped in his books for so long; Daniel has a jazz improvisational skill set, he's so quick and so sharp, and I think frankly might have gotten a little bored with his original stories. So the script that I read which, was what they were going to be producing with Barry, was really madcap. It had elements of those first three stories but huge departures and lots of madcap elements. Maybe because I was a new convert, I was much more faithful in my vision to what he'd originally written and I was very stubborn about wanting to respond to these fantastic looks that I'd read. So the DreamWorks crew was in agreement and we knew we would be going off to start a new screenplay. One of the biggest elements was actually Lemony Snicket himself and in Daniel's script, Lemony was on-screen, he was a bit of an emcee and to me, the great mystery of those books was always that sense that Snicket was in shadow. Seen around the edges of the frame, never quite exposed and that was the idea of having him as the narrator only and just seeing brief glimpses of him top of the picture, in the middle of the picture, and at the end, so that was very much by design. But it's truly for the audience, I think that the two tones are each very legitimate. Barry did go on to do the Netflix series version and honestly, it is exactly what the original movie felt like and I was maybe attracted to an emotional undertone that I didn't quite feel present amidst all the other madcap comedy and that was what I was determined to bring to the film. So both are very legit, and the audience can always decide but I think you get no better sense of distinction between the two versions than the movie and the series. 2) Did you have any specific actors you wanted in mind when you began planning out the movie? I think Meryl Streep was really -walking in immediately to try to start putting the film together- the one actor I knew in my dream of dreams would be perfect for Aunt Josephine, so that was an early conversation with her agent Kevin Huvane. It happened that she had a daughter who was a tremendous fan of the books and so there wasn't a lot of convincing, she was very excited to join the effort. Other than Meryl, we knew what we needed out of these young actors and just dove into trying to find them. Emily Browning presented herself early on, my casting director Avy Kaufman has just got such a wide breadth of knowledge of up and coming actors from all over the globe and she also pointed us to Liam Aiken. Again, both very early candidates, both came in to meet me, Emily came in from Australia and Liam came in from the east coast and they got those parts really before there was any major contest. I think I had the idea for Billy Connolly because I just think Billy is such a huge warm unexpected presence and he seemed to make just great sense for that part. Likewise, Tim Spall, it's like when you think about the essence of Mr Poe and who that actor is going to be. He can just make you enjoy him bumbling and handing the kids off into horrendous situations, really standing in for all adults in a way. The rest was just meeting all these fantastic other comic and improvisational actors along the way. 3) Were you on board when the production considered filming in Wilmington, NC? If so, did you scout any location in that area? As someone who lived there for a long time, I love thinking about the alternate version of history where the film was produced there. Especially since, according to some articles from 2003, sets for the Sonnenfeld iteration had already begun construction there. Is that true? When I stepped in (along with DreamWorks) to start to build the movie from the ground up there was no Wilmington, North Carolina conversation. I think that had been a budgetary solution that was being explored back in the Rudin and Barry Sonnenfeld iteration, partly because of how the costs had grown so huge. At the time I knew we were going to basically be doing a mostly set-bound film. I sat in a room with Steven Spielberg and Sherry Lansing and Steven kindly asked me where I wanted to make the film. Jim Carrey was also in that room, and I said " I'd really like to take advantage of all of the incredible artisans here in Los Angeles given how handmade this film is going to be". Jim, of course, weighed in and said "absolutely, I would like to do it here as well" and so there wasn't much of a conversation at that point. So we did, between Paramount and then down in Downey at the old Boeing facility where they had made the space shuttle. Originally, I scouted a bit to the east coast and Rick Heinrichs and I very quickly just came to realize that to honor the illustrated, handmade quality of the world that Daniel had created, just stepping out into the real world was sort of going to fail the film. It was just a little bit too much in the here and now and so we committed wholly to constructing both our interiors and exteriors with some incredible forced perspective sets. We created our own Lake, on which we had four standing sets concurrently, so that was a bit of an exploration. Back east, we did use a photograph of a home on Constitution Avenue in Boston as the Baudelaire home but that's truly the only actual real-world location in the film. Just an addendum to the third question, no there were no sets under construction. Before the original production dissolved there were many set designs and some models that were created but there was no construction and so those never came to fruition. 4) Over the years a number of rumors about the movie have popped up on Internet sites and been accepted as fact by websites like Buzzfeed. Two of the most popular are that the Baudelaires' mother in the flashback sequences was played by either an uncredited Amy Brenneman or Helena Bonham Carter and that the ending of the film originally had Olaf tailing the children in disguise. Are either of these true? If not, were they ever planned to happen at any point? Yes, my wife Amy Brenneman is indeed the silhouette in the silhouettes of the Baudelaire parents and she's also photographed with my production designer Rick Heinrichs (who stood in for me for the Baudelaire father in the on-set photography). At the time she teased me because I'd had her also play a deceased mother in Casper, so she was convinced I was sending her message, but it was not the case. I just thought she would be perfect for that. No, I think that any concept of Olaf tailing the children in disguise again may have been some element from the original Rudin production. In our case, we were always were going to just be with the Baudelaires, who again triumph through adversity and who get to finally close their eyes and rest the end of the picture. Which is very much an image I had in my head from early on. So, no there was no alternate ending in the end that was envisioned. 5) Was having a narrator throughout the film a controversial decision or was it already agreed upon? What was it like trying to integrate him throughout the scenes to set the mood and storyline? I wouldn't say that the narrator was controversial, it was quite the opposite. For me, what was controversial and pretty much unacceptable was having Lemony Snicket on-screen, visible to the audience. It just seemed to betray the concept in the book and every time I would, as a reader, not really be able to picture where Lemony Snicket was but knowing suddenly that he was in a room with water filling up etc. Again, I wanted that to be mysterious, to feel like he was on the case and definitely a detective (somewhat in the future looking back at these events) but no, the studios were both very much in agreement. What was great was it allowed me to ask Jude Law whom I knew (and Steven Spielberg knew as well from A.I.). It made it easy to ask him to come in, both to do the narration but also the very fun day of shooting that I planned, with him in the clock tower and dashing about. Again still mostly in silhouette and unrecognizable, but that is indeed Jude. 6) Many of your films deal with issues of ordinary people struggling with the death/absence of loved ones, thrust into extraordinary situations. Is this a theme or concept you have actively sought out in your work? I had a great mentor back in graduate school who shared with me the truism that "we as filmmakers and artists, we're not really always aware of the stories that we will tell again and again in many different iterations but they are the stories that we are supposed to tell". So I have never actively sought out stories of loss or loved ones contending with the aftermath of loss. They have always been something that obviously I feel I have a kinship to and a knowledge of, but the amazing thing in filmmaking is stories find you as well as you find them. So when I was asked to take a look at these books, I felt a kinship with them and as I say that's where my vision probably varied pretty immediately from what the Rudin/Sonnenfeld film would have been. But again that was not something I was seeking out, it's just what happens. That was true of Casper, where Steven Spielberg in that case might tell you that he came to me with that because of this sort of emotional underpinning that I am often keen to have a film. But again, not something that I sought out so that is the great mystery of art. We have stories to tell and we will tell them many different ways but not necessarily consciously. 7) Your films run the gamut from independent dramas to big-budget PG-13 genre comedies, what do you look for in a project, as both a storyteller and director? I used to have journalists at press junkets begin an interview saying "wow this film is quite a departure for you" and then they would eventually stop because they would realize that each one of the films was a departure. And that's by design, I just go where there is a story that I feel insight to, that moves me, that excites me. And that can be a $2,000,000 movie or $150,000,000 movie, it does not matter. What matters is my having a sense that I know a secret and that I can share that secret with the audience and that this particular story gives me the language in which to share that secret. So I am always drawn to stories and unlikely and unusual canvases but it's always characters first and some sense of emotional truth. Whether that's a comedy, a fantasy, or an out and out drama. So that makes it a little difficult for people to second guess what I'm going to be up to next; it's what keeps me interested. 8) One of the scenes that spoke to me most in the film was the simple and intimate sequence between the Baudelaires in Olaf's attic bedroom after he slaps Klaus, where the idea of the letter that never came is first introduced. What I love about it is that it always felt very real and touching and the performances between Emily and Liam are particularly strong. What was it like, to bring this scene to life from a Directing perspective? The attic scene with the Baudelaires after Olaf strikes Klaus. I always knew that was going to be the emotional anchor. Certainly the legitimacy, emotionally of the children's plight in the film. I knew that in casting the actors I had, they would have the ability to play the honesty of that scene, the same way that you don't try to play for comedy in a comedy. You try to play the truth of an obstacle. Likewise, regardless of what our film was in terms of comedic tone and things that might be larger than life, the pain of Klaus in feeling betrayed by his parents, I knew had to come across. As well as Emily-as-Violet's tremendous care for her siblings. So that's what we went to work on with both the actors. I said to them both that "this has to come from a place of truth and you're going to do your own homework and find where you have had those betrayals." "You'll never have to share them with me but I'm going to know if you are just acting/pretending versus finding something really resonant and truthful for you". They both did a fantastic job. 9) Do you have any favourite moments during production? Not necessarily your favourite scene, but something that happened that you won't forget. There were plenty of unforgettable elements to our production. One I can point to, which somewhere is captured on film, was an accident. It was a malfunction when we were preparing Aunt Josephine's house for the hurricane sequence. Michael Lantieri (my on-set effects designer) was tasked with constructing a foundation that was raised for this house which could drop on cue but still not have the set collapse, in terms of just falling apart entirely. It needed to essentially have the first big drop that I could capture on-set before we would finish the rest off with our scale model at ILM when the house eventually falls. The central support was like a giant piston which would then give way on cue and there was an emergency stop; a certain stage below which the house was not supposed to drop on this gimble. I was on set with my camera and with a couple of other people, certainly no actors. This was not the day the house was going to be photographed yet, it was just a test. Sure enough, we rolled film and when the mechanism was fired, the entire thing dropped on this gimble and went well past the safety stop. It was quite a sight, you saw objects, people, everybody, suddenly suspended in the air before coming crashing down. It's a pretty remarkable piece of film and word got out to the studio very quickly that there had been a mishap on-set and my executives came down to make sure we were okay. I landed square on my bum, fortunately, I didn't break my tailbone but it was pretty exciting. We had a very dry assistant to the on-set effects guy who after the glass has shattered and everybody was speechless, he spoke up and simply said "and that's why we test it". So that was among the more memorable moments. 10) How did you manage to make Kara and Shelby Hoffman perform as well and convincingly as Sunny Baudelaire? Was there a time when they spontaneously acted out of the script that you liked their natural reaction the most and left it in the movie? What's remarkable about the Hoffman twins that everyone has to remember is that they were 14 months old when we began working with them. I mean that's incredible. Originally to try to help ourselves with the schedule I had cast a set of triplets and the challenge was always hoping and knowing that you really wouldn't have a sense of if they could work if they would have separation anxiety, or any of these things until you got there. As much we tried to set up playdates and get a sense of the original triplets, it was apparent on day one that there was going to be an issue. Their parents were lovely people who had literally moved home out to California from Washington DC to be able to do this but it was apparent that that was not going to happen. So we went to a very quick casting mode to try to come up with the replacements and those were the Hoffmans. Interestingly, just to show you the personalities of twins; Kara was definitely the more reticent of the two. Shelby loved to work, she was just a sunny happy kid and Kara was very bright but always a bit more sceptical about the work portion of it. So there's no doubt that Shelby has more screen time in the film but one of the challenges you have is the work hours; you cannot work little ones that age past a certain point. So you have to make the most of them and for me as a director that was about trying to get to what the story essence was of every moment with them and their interaction with either their siblings or with Olaf and even at that age treat them with the degree of respect. Which is to set up a good game of make-believe; these girls were so bright that they could. But of course, what you do is you let that camera roll because there may be some wonderful surprises, unexpected reactions/behaviours, and you as a director are a thief, you have to steal the best of those. Of course, you also have to remember that Sunny is subtitled and so the other advantage is that if there was a terrific reaction or some piece of behaviour, we could always write back to it. So there was some writing in post-production that we did just keying off of the work from the girls. Kara was really set off by the stand-in we had for the incredibly deadly viper (which we needed to be able to show scale and to rehearse with) she did not like that viper so that put her off work for have a good bit of time. We finally got her back but she did not trust certain elements on set, but Shelby always did. You know it's an unusual thing to have to build in naptime to the schedule of your actors and sure enough, there was a teamster dedicated to driving the girls around in a van to help with naptime so you can't beat that. 11) There are some recurring elements from the books that were played down in the film, such as Mr Poe's coughing fits and Klaus' glasses. May I ask why? It's funny, film is a very visceral medium and elements of sound and visuals are so strong and striking that often story can be told with them more quickly and effectively. The corollary to that is that once you've set up certain elements in film, if you keep going back to the well with those, because of how visceral they are they can become repetitive or annoying. So interestingly, Mr Poe's cough was something we discovered early on that simply felt like a bit of an annoyance and a stall; in that, it wasn't actually helping us. So that's the difference between film and prose on a page. Klaus' glasses were an interesting case, for the moment one sees them, brief as it is. I was particularly uncomfortable with how close in the illustrations Klaus' glasses looked to Harry Potter's, and I worried that it was going to feel derivative. So we made two decisions when was that yes, Klaus would have some glasses for reading but we designed them to be rimless and nose pinching, I thought they just looked fantastic. You have to remember that this was 2003/2004, sort of the height of the Potter fandom; it struck me that the on-screen character deserved his own identity and didn't want to seem like a Harry wannabe. So again, that was the visceral nature of film for me dictating let's go a different direction, which Daniel was completely supportive of. 12) What did the average day on set look like during filming? Lemony Snicket was a film where there really were no average days. It was like making many different movies, mostly driven by the different environments that we would be visiting in each of these sequences. So that meant again taking over most of the major sound stages at Paramount and then eventually in the spring of '04, moving down to Downey, to the Boeing plant. Downey was really home to not only Lake Lachrymose but also Briny Beach, Curdled Cave and then obviously the Aunt Josephine's demise sequence in the lake. So the exciting thing was that jumping into a new set was like jumping into a new movie and we had so many, so as a result there really was no average day. It was a very long schedule. The variables that you can consider; you've got 2 teenage actors who have a certain number of hours of schooling, you have infants who were 14 months as we began with very restrictive work hours, you had a lead actor who boasts close to 4 hours of make up each day. Jim also had (as most movie stars certainly did back in that moment) what's called a portal-to-portal deal where he was expected to be picked up and dropped off back home within a 12 hour period. The combination of those variables made for an incredibly challenging schedule so again no average. There were days when I just felt like I was a miner going into the mines with my cap on, to make more film. Every day was different, every day was exciting but it was a marathon, not a sprint. 13) Some pages from an early draft of the script were leaked and featured a subplot with an unidentified woman and two young children following the Baudelaires throughout the story. It's quite a big departure from the story in the first three books, how far into the process of making the film did this element survive? Even after you took over the film, were there any elements from later drafts of the script that ended up having to be changed or cut? Again, there were many departures in the Rudin And Daniel Handler draft, which Barry was going to direct, many of which I've already forgotten in specific. But they departed greatly from the books. Not sure exactly where that came from, though as I say, I think Daniel was enjoying riffing on his world, maybe wanting to do something new with that world. I had the advantage of being a new reader and so, as a result, I was much more of a fundamentalist and strict constructionist in really wanting to present more closely the world he had on paper. Our challenge was that we didn't want a film that was strictly episodic and so that is why while tackling the first 3 books we created a structure that ended with the Marvelous Marriage. As opposed to where it finishes at the end of the first book. We wanted to find a way for there to be sort of an overarching narrative. I can't speak to a number of the other sort of departures that were in the more madcap version of the script. 14) The score for that movie is perfect! Did you immediately think of Thomas Newman when planning the score? What was the process of working with him like? How did he present themes and ideas and what was the early creation process like on the score? I've always been one of Tom Newman's biggest fans and had always wanted to work with him. I believed in my bones the moment I came onto this picture that he would be the perfect man for the job. I had just seen the work he had done in Finding Nemo and once again was marvelling at his ability to create an emotional landscape that's genuine while also diving into new worlds. So I reached out to him straight away and he was very excited to come on and to join. There were really no cues left behind, regardless of rumours, the only cue I substituted on the stage (meaning the mixing stage) was indeed the train track cue. I found that the cue Tom created, which is represented on the soundtrack, didn't have the fullness and drive and dynamics that I wanted for that sequence and the suspense in that sequence. So I didn't believe it fully served the story purpose as well as it could have and that was the only cue that we had a difference of opinion on. But his incredible music editor was able to help construct the cue that made its way into the film. I decided late in post-production to try to create the credit sequence at the end of the film, which I'm very proud of. I wanted it to be essentially an emotional coda, almost a dream-like coda for the whole film where we leave our young characters asleep in the back of Mr Poe's car. The wonderful curtain goes up and then you head into these essentially two-dimensional shadow puppets. Tom had scored the whole picture (there's a lot of music in the film, we had so many sessions). So I didn't want to burden him with suddenly saying "oh, by the way, I've got a gigantic new cue for you to write". That said, I did want to let him know about it and Tom is a perfectionist and he's very proud, but he can also be his own toughest critic. So when I did tell him, he was like "oh man, I can't believe it, how am I supposed to accomplish that?" and I said to him "you don't have to". "I will work with Bill your incredible music editor we will cook up something from all this terrific score we have, we will do it". And sure enough, I believe it was the next day, maybe two days later, he called me and said: "well, okay, listen to this". Then he played me that awesome cue that begins once the last scene scores out and carries you through that whole sequence. It has a different flavour than a lot of the rest of the score, it sounded very exotic, it's perfect and it's just a fantastic vibe. So that's Tom Newman to the T; can't ever let it go, wants to contribute, and so we had a fantastic partnership. 15) As an Editor & Composer myself, I've always wanted to know the story behind the music edit on the Train Sequence. I'm curious what the creative reasons may have been for replacing most of the original track with segments of other parts of the score. Articles from the time, say that he had over 30 scoring sessions for the film spanning nearly a year, was there any other music that was recorded for the film but never used? Have there ever been any talks about releasing more music from the film? As to the process with Tom, it's really organic. I ran the picture for him to let him stew in the juices in the movie and then I would come over to his home studio and he would begin to play thematic elements to me. In some cases, he had a pretty clear idea of where those might live but other times not, which I loved. He would say "I'm feeling this and I don't know where it belongs but does this make sense to you and if it does let's find it together" and so we would hunt through the movie and see where some of these elements might live and see which ones would develop. The orchestral elements he will do last, he loves to pull together what he calls his "cats", his very specific musician friends to play some of the more interesting acoustic unusual elements that you often hear in Tom scores. He'll do those sessions now in his home studio but at that point in time he was still doing them over in a place called 'Village' in Santa Monica. Those are recorded and edited so that then going to the orchestral stage they exist to play against picture. So as he goes to conduct he can then listen to his orchestral takes meshed with the acoustic elements. It's an organic and really exciting way to work and super intimate just the two of you and then his music editor Bill, who is also wonderful. A great process. 16) You've mentioned before in interviews that there was a little bit of tension with the studio over cutting elements deemed "too dark" from the film. What, if anything, can you say about the post-production process and the conflicts in the editing room? To be more specific, what was the process of test screening, recutting and rescreening the film like? Were there any sequences, lines, or characters that had to end up being cut out of the film? On a film like Lemony Snicket, you are dealing with some very specific tensions. You're dealing with a very large budget, and larger budgets tend to mean that a studio hopes to capture as wide an audience as possible. And you had a property whose entire marketing campaign in book form was "Don't read this book, whatever you do, don't read further". You know, the sort of wonderful anti-sell that was so exciting and smart and inventive about the Lemony Snicket books. And interestingly, we knew from the beginning that there would be potentially some nervousness on the part of the studios. Though we tried to remind them at every turn that this is why these books are a hit and why you have a rabid fan base, because of that tone and that commitment to that tone. I actually did something in prep to try to help remind the studios, specifically Paramount, of this and I brought a bunch of young school-aged kids into my art department on a weekday afternoon and essentially videotaped a town hall meeting with them. I asked them questions and showed them artwork of sets I was going to build and what props were going to look like and essentially got them to reinforce that the darkest elements of Lemony Snicket were why they were there. I truly would say "well okay, yes, in the books Count Olaf murders any number of characters, he really actually kills Uncle Monty, but you don't want to see that in the movie" and the kids would yell "yes we have to!" So we cut and put together this presentation to give to the studios, to give them some courage to try to help them, but we knew it would be a challenge all the way through. And so certainly that was the case, it was a lot of hand-holding, in terms of the sort of wonderful darker handmade palette of the film. Because again, you're going back to the heart of fables and fairy tales which were not sunny. They were allowing young readers to kind of touch the darkness and then feel safe and feel smarter than. So we knew we had to walk that walk and fight that struggle in production which we did. Post-production was no different, I've never tested a movie more. And that was again because you understandably had studios with a major financial commitment who just wanted to make sure that it wasn't just the young people who were going to like the movie. They didn't want the parents of those kids coming to the film and feeling like we killed off the mom vote or the dad vote, down to the score. At one point there was concern that the score was too dark and I was very adamant that it was not only perfect for the movie but that once the score was allowed to be run (which would only happen when we finally mixed the film) that it was going to only provide, if you will, stronger scores. Indeed there was a night where we tested, side by side in 2 different theatres, the very same edit with a temp score that was deemed to be more playful (not all the way through, but a lighter score) and then Tom finally allowed me, for that test, to use his score. He was always understandably worried about what he would call "crib death". Which is sometimes if a composer scores a picture and they use the actual score at a test screening, if for some reason the test screening doesn't go well, scores have been known to be tossed. So he was desperate not to see that happen, but I said to him in the end, "I need your score because I need to prove them all wrong". We tested both, the very same picture with Tom's score, huge. More than 10% stronger final score in the tally and so everybody breathed a sigh of relief, the studios were both very supportive suddenly and off we went. Again though, this is normal for a major investment. If you're making a 2 million dollar or a 5 million dollar independent drama, you just don't have as many constituencies and you need to know this as a filmmaker. So I was not surprised, it's just a level of energy that one has to keep alive even while you're going through this marathon. You need to keep up the energy to arm wrestle and to try to protect the film. What's interesting is the whole notion of director's cuts. I think, without exception, I've never made a picture yet where (other than some small specifics) I've ever felt like my cut of the film is truly divergent from the release version of the film. They really do feel like my edit, and I know that holds true here, too. Part of what you're testing is the audience's patience as well. There are so many elements that we all love. We love to set up, we love the character setups, we love the world, but you are telling a story and engaging an audience as well. You do make some choices along the way for compression, that are about keeping the energy and flow of that narrative up for the audience. So that's not so much a studio saying, "lose that, lose that". It's your own metronome as a filmmaker and knowing that you need to not just get overindulgent in areas. 17) While I love the film's ending, some of it seems to have been cobbled together, with narration playing over reused clips from the film and shots from deleted scenes. Was this always the intent, and if not, what was your original plan for the ending? The ending narration for the film was designed from the get-go. I'd always intended to basically give that sense of how Lemony has to move on from each temporary hiding spot in trying to tell this tale and hand off his pages. So I had visited a clock tower in Lowell, Massachusetts when I was scouting with Rick and I said: "that is where Lemony should be in our film and that is where he should leave this instalment to be found". So that was always by design as well as then finally ending with Baudelaires seen driving away and being in the car with them. This is the great part about editing a film, as you know with films, you're directing on the page as you write, you're directing when you're on set, you're directing when you're editing. It's not a fixed proposition, discoveries are made and often they're just on instinct and ephemeral and I had a real instinct that I wanted to see their faces one more time in these particular vignettes. Even as Lemony is reminding you of their qualities together, their particular skills, their resilience, and so the idea of 'going around the horn', revisiting images, was discovered in post out of a pure emotional endeavour. There's an image of Sunny chasing after what looks like a little red ball and that was actually just the target that we had for Sunny, chasing after the tale of the viper. It was a clip that we didn't use and yet I loved how playful Shelby was and so we just used it and made it a little magical prop that was sort of like dashing off away from her. The shape, the narration, all of that was as intended but plugging back into these moments and re-visiting them from the film is something we discovered in the cutting room. 18) Before the Netflix tv show came out, a sequel was in development for many years, going through many different iterations. Including a direct sequel that picked up immediately after the ending of the first movie, and a potential animated reboot. Were you involved with any of these, and did you have any particular actors or visual ideas in mind? Within a month of the film's release, there was an early conversation about a sequel and that conversation was between DreamWorks and Paramount who had both financed the film. There were some real differences of opinions and there were certainly concerns about the budget; the original film was very expensive. Actually, the first time I met Sherry Lansing (the head of Paramount) to talk with her about making the film (much as it would have exhausted me) I asked her "why not make the first 2 films at the same time?" Just to essentially save money and have the economies of doing two pictures, amortizing some of the costs of sets. Because the books were clearly already a hit, so it wasn't a risk, it just seemed like a wiser move and Sherry interestingly felt too superstitious to do so. So by the time the movie opened and the studios got into conversations, there was just essentially dissent as to whether to specifically do a direct pick-up and again try to combine multiple books versus essentially committing to, for example, The Austere Academy as a standalone narrative. I think it was the elements of cost, obviously, Jim Carrey's fee was only going to grow, so I think the two parties couldn't quite decide what they wished to do. So over time, the option for the series made its way over 20th Century Fox. I think Paramount and DreamWorks ended up in a stalemate and so let it go and it moved over to Fox. Daniel was involved there. Nothing moved forward and so by 2006 I just had a crazy idea and I said to Daniel "you know, one thing that just might be fantastic would be if we get meta about this and basically try to move the series along in an entirely different art form". Meaning, say to the audience upfront that the actors have taken far too long in this dramatization and even potentially see Jim l storming out of the make-up trailer with his little tissue around his neck and being locked out of the soundstage. Lemony essentially telling us that "now, I'm afraid I need to tell you the story as it really was", and my pitch was let's go do it as stop motion. Let's literally step aside from these conversations of endless budgetary issues and actor scheduling issues. I think I was emboldened by the end credit sequence in the movie, which I just adored, and just reminded me that it's a very essential human story you're telling that's very artful and so why not? Why not, in a way say, that the first film was really just a dramatization but that it was going to continue down its real form. Daniel said "yeah, and then the next film can be told in an entirely different art form". So anyway, we were a little ahead of our time and nobody quite bit on that one but we just both thought that would have been a fantastic way to go. So things went nowhere until the dawn of streaming and when I saw that they were going to try to make the series and Barry was going to try, it did seem like the perfect venue. Because instead of having to fight the challenges of the episodic nature, in trying to combine books into a feature, the idea of being able to actually just go a book at a time, made great sense to me. So I was happy for the form finally fitting well and for Barry to be able to get his tone as he had always imagined it there, as well. 19) What was your favourite scene in the finished film? I don't know that I'd say that I have a true favourite scene in the film. I really adore all of what went into making the hurricane sequence. In imagination, in terms of craftsmanship, in terms of all of the cinematic tools put to work. So I would say, for sure, from the beginning of that sequence until the Baudelaires basically make their way over and the house tumbles down into the waters below. That's certainly amongst my favourites and was quite a piece of work to accomplish. 20) What was your favourite book of the series, and which one would you have liked to adapt most? I have a recollection of The Austere Academy and The Vile Village being particular favourites in the remaining books of Daniel's series. I just think the Austere Academy's characters and the emotional pain and truth of being put off into separate awful dingy living spots. Headmaster Nero and his endless horrendous violin concerts, it all felt true to teenage middle age and middle school challenges but it was so Lemony. So I had been very much a proponent of that being essentially a standalone picture if we had made an immediate follow up. I just also love that Vile Village felt like an old Universal horror movie to me in terms of that setting, the kids' ingenuity and having to break out of jail. That's a particularly strong Klaus story (can't always be about Violet all the time, Klaus has to have his day). So I really did love those, but so many of the other ones are great, those were just the standouts for me. 21) What were your visual and thematic inspirations for the film? What became immediately apparent to me was my desire to get down to visual graphic essentials. So essentially, that's very much a theatrical concept, that is why we knew we wanted to build our interiors and exteriors on set. It's painted backings, it's forced perspective work. Interestingly, you do connect with reference and inspiration in a way that's magical when you're preparing a film, I really believe you open yourself up and as you're getting a sense of it sometimes things fall in your path. The photographic work of the British still photographer Michael Kenna became kind of a Bible to me. He photographs real-world landscapes, he's done them in Japan, he's done them in the UK, very graphic, very essential, very few elements. They look incredibly theatrical because of how spare they are and how graphic. So I just started making photocopies of my favourites with Rick we would sit and break down what worked about them. It was the inspiration for Briny Beach, it was the inspiration for so many elements in the film. And again, in a sort of old stagecraft vein 'Night of the Hunter', the incredible Charles Laughton film, I screened again and again. I screened that for the art department, screened it for 'Chivo' (our cinematographer), I screened it with the cast. I just thought, in essence, we were doing a version of Night of the Hunter, which has some incredibly similar themes but for a wider audience. Some of the bold techniques of stagecraft and forced perspective miniature work in that film. Count Olaf sitting in the hallway at Uncle Monty's was a very specific homage I created to Mitchum in Night of the Hunter, that sense of sort of evil lurking and rocking in a rocking chair. 22) Did you have any contact with anyone developing the tie-in video games and the marketing? If so, what were they given as far as production assets go? Given that they had to start working on them in advance of shooting, was there anything they had to change as story ideas were dropped or reconfigured? I honestly didn't have a lot of contact with the video game production, which absolutely had to be underway, even as we were making the film. I can't say that any choices we made forced them to alter their plan, but we really were not collaborating. I know they were borrowing assets from our art department, and certainly trying to live within the design and palette of the movie. But we were so busy, just making the picture and getting it ready for its release that we really didn't get involved. I certainly didn't. So I can't really speak to that. 23) I think the best scene in the movie is the destruction of Aunt Josephine's house. What was the creative process of planning and shooting, such a breathtaking action sequence like? I spoke earlier about my affection for the Hurricane Herman sequence where Aunt Josephine's house gets torn apart. Essentially, as in many sequences that require incredible coordination between the art department, construction, wardrobe, and on set effects, I storyboarded the sequence to basically make sure everyone was dialled into what my planning was going to be. From that, we would then break down "yes, okay here's where the house -on camera- needs to fall to a certain point, here is where we're going to have a digital painting, here's where we're going to need this piece of on-set effects work with the hot gas leak". And then going through safety planning, what portion is the kids, what portion is not. Actually, what's remarkable is it was all eventually planned so well enough that a lot of the wider pieces of the kids trying to make their way uphill, even as the house is starting to come down, all of that was actually the kids. So it was just the most first-person experience I could imagine, being inside a structure like that, even if you're making incredible discoveries about your family that you've been waiting to get and suddenly that's happening in the tumult of a hurricane. So great fun to imagine and just tremendous artists who I was able to collaborate with to pull it off. 24) Given that your excellent suggested idea for a teaser trailer (as mentioned on the DVD), and the prototype version you made from the costume tests you shot, did you have any involvement with the film's marketing? What are your thoughts on how the film was eventually marketed? As I mentioned earlier, we knew marketing was going to be a constant tug of war but we really did believe that if you didn't honour the sort of wonderfully playfully dark anti-sell of the books it would be confusing to the audience. They might not really understand what the picture was going to be. So I wanted to take advantage of the wardrobe camera tests we were doing, to sort of give a direct to camera address of presenting these characters and the poise that they have, which was great fun. Yeah, myself, Jim Carrey, and certainly our producers remained very involved in the marketing of the film. Again, that's not to say that it wasn't without a lot of arm wrestling. I think in the end the studio was trying to kind of ride a line where they could play up what was playful and the film and not potentially alienate a family audience that might not know the books. Again, the bigger the investment, the more they want to capture a wide group. But we wanted to make sure that the varied tone that brought us all to the table was alive and intact, so it was it was a challenge. But it was one that all parties were understanding of each other's sides and Jim, along with me, knew why he was there and so we were very clear with the studio marketing team at Paramount and vice versa. So it was an iterative process, many iterations of trailers and one-sheets and so I was glad that I ate my Wheaties late in the game so we still had some energy to go through those discussions. 25) What is your favourite moment/element of the film which seems to get very little recognition by people? I don't know that there are particular elements in the film that I wish got more recognition. I certainly know there are elements that I wish I had more screen material to play with. I thought that the main dock at Lake Lachrymose when the Baudelaires first arrive, Rick Heinrichs, designed such an incredible set and I only wish that I'd had more material to play out on the streets of the town because it was just extraordinary what he did. Again, all in forced perspective. It's a true piece of artistry, so that's more my own regret. I wish there had been more material there for me to play with. I will always enjoy the day I had with Dustin Hoffman. Dustin and I had just done a film together and he was friends with Billy Connolly and I said "I think it'd be genius if you came and played a theatre critic and just come for the day and we'll get you in wardrobe and hair" and we had a blast. I do enjoy his presence in the movie, brief as it is, to the point that some people actually miss it, but it was very fun. I think if the audience knew the rings of challenges to get the film on-screen that we did, I think they'd be a bit dumbfounded but the nice thing is they don't have to worry about that. They get to just enjoy the film. 26) Given the success of the #releasetheSnydercut movement, have you ever considered revisiting the film in some way? Perhaps even putting together your own director's cut of the film? I don't really believe that there's a director's cut of the film that lives beyond where I landed. One of the great things in DVD culture and before that laserdisc culture( which I was a part of) is the ability to have all of those fantastic deleted scenes and other elements. But we do make choices in editorial for a reason, we're serving the best purposes of the picture. Now there are cases where films have sort of left the hands of those directors that audiences may not be aware of and studios have taken over. But as I mentioned earlier, I haven't had that experience and so while I really enjoyed the audience being able to take in some of the other really fun work that we did, the choices were made for a reason. I think a lot of the scenes with his terrible theatre troupe; that's a short film. It's funny, Ben Kingsley (who I did a film with) made a wonderful short for Marvel about a side character that he had played in Iron Man 3. Had we had the opportunity back then, that would have been what I would have loved to have done. There's so much material, those actors were so fantastic, and we just had a ball with all of Olaf's awful acting classes and the work being done by each of those. But again, they didn't serve the story and when I did my first passes on the sequences, things would just grind to a halt. We would be enjoying ourselves tremendously with what that work was but it's the challenge of balancing out editing an entire narrative. If was asked by the studio to sign off on a new director's cut, I wouldn't find myself putting that work in. We lost very few battles, one of them that we did was that the studios found Aunt Josephine's demise is too frightening, too visceral for audiences. Now we didn't literally see her face being eaten off by a Lachrymose Leech, but we did see her in the water slowly descending, her face disappearing beneath the surface. It's incredible work that we did with Meryl and with our leeches, and that's the only moment in the picture for me that both studios ended up agreeing that we really needed to alter. So that's why we had the sort of little banana resurfacing at the end to pay off the Sunny element. But I'm certainly not going to release a director's cut just to swap out the end of Josephine's demise. But if I were, that would be probably the element. Meryl was very sweet, she knew exactly what happened and she gave me a big hug. 27) Would you ever like to return to the world of Lemony Snicket and do you have anything in mind for the film's rapidly approaching 20th anniversary? Is there anything about the movie that you would do differently today? At this point in time Lemony Snicket feels like such a complete experience for me as it is. You just never say never as a storyteller but I am grateful for what was such a such a very complete and long experience. No specifics as of yet, the picture's release was in 2004 so no doubt as we get toward '24 we'll be looking at some elements. There may be some very fun pieces that we'll be able to pull back together, but nothing is planned as of yet. But when I think back on the film, I am grateful that the studios allowed us to make the picture the way we wanted to make it. That was for almost all intents and purposes in front of the camera, not a giant CG-laden mess. With incredible set construction, just more sets than we could count and painted backings. So many elements that today even back in 2003 and 2004; one would be really pressured to hand so much more of that over to visual effects. But real light on real surfaces always moves me and I can always smell when it is not that. So for the studio to back us on this crazy concept of doing it as a completely stage-driven movie without over-reliance on computer-generated visual effects is really one of the great victories of the movie. One that I'm still grateful for. That would not be something that I would change, it would be something that I would desperately hope to hang on to, but any new version of that film today would be under tremendous pressure to sort of bring it into the digital design world. 28) Are there any questions we should have asked? I think the only question I'm not seeing here, which may be answered on the DVD, but nonetheless was always of great enjoyment, was the element of improvisation. People have often asked, given Jim's presence in the film, what portions were improvised. I just had an instinct when I was shooting makeup and hair tests and wardrobe tests with Jim Carrey, that I wanted to get to know these different characters, these different iterations that Olaf was going try to pull off. What better moment than without the entire crew and without the entire expense of the production being up and running, but in a smaller setting to frankly just interview these characters. Normally when we shoot make-up, hair, wardrobe tests there is no sound recording it's just a visual. But I did ask to have the sound mixer present for the day and so I essentially sat by the lens and interviewed these different characters. We felt this magic happening even as we were doing it and so Jim and I looked at each other and knew. So essentially, once the dailies came in, we sat and kind of together wove together elements that we really thought worked for these characters and then wrote those back into the script. So they were not improvised on the day, they were improvised in preparation for the film and it was a really educational process. We had an iteration of Stefano that didn't work; it felt very on the nose and almost sort of Pirates of Penzance. We looked at the dailies and I just looked at Jim and I said "I think it's not it" and he was bummed but agreed. Then out came this incredible discovery that he and Bill Corso made in the makeup trailer of this strange bad comb-over with the mustache askew with Jim sort of doing a National Geographic fellow. I fell over and said "that's that" so we quickly got him onto the stage for me to interview him and that is where all that material comes from. That's one process that was magical in the film which many people who have watched the DVD carefully probably know but it was unique and a real gift to the various Olaf characters in the film.

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Chris Huvane is listed as Jensen's manager on Jensen's IMDB pro page. So he's definitely representing him now. If Jensen had some other women as a manager before, that means he changed the manager. He's also Danneel's manager. Think Becky and Danneel didn’t get along? Why switch agents within same company after all the years?

I just remember that Danneel had a show called Friends with Benefits that was canceled after one season. Rumor was Danneel was hoping to be the next Jennifer Aniston. The original Jennifer Aniston’s agent is Kevin Huvane and her publicist is Stephen Huvane. Yup, brothers. Now Chris is a partner/manager at 360 and I can see a future company emerging – Huvane, Huvane and Huvane, one stop shopping.

As for the change of management, I’ve always thought Jensen’s management from 360 or WME was kind of shitty so maybe it’s a good thing that he switch from Becky to Huvane, at least for the family connection to Chris’s more successful brothers, Kevin and Stephen. But jackles, Chris said that he and his brothers don’t discuss business with eachother in that Vanity Fair article. Yeah, riiiiiiight, sure Jan, just like the Baldwin brothers never discuss politics or religion at Thanksgiving.

I just want to know how Jensen convinced Chris to take on Danneel a client.

Jensen: Chris, you got to see my wife’s demo reel

Chris: If it’s from Baby Boot Camp, so help me God...

Jensen: No it’s from Supernatural where she plays two different characters

Chris: Isn’t it one character with two different names? Wait, when were you in Peaky Blinders? Wait, is that Jared playing a woman?

Jensen: No, that’s Danneel.

Chris: Noooo, pretty sure that’s Jared, though he’s usually better at this, like when he played Lucifer as a woman. And there’s no chemistry between the two of you in this scene. Did you two had a fight?

Jensen: You know what, you’re right. That’s Jared pretending to be Danneel pretending to play Jo.

Chris: I hear Dan Spilo is getting MeToo-ed.

Jensen: Yeah, so “Jared” is going to need a new manager

Chris: Sign him up!

Me: Hey, it could totally have happened this way.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

INSIDE a flimsy temporary office on a dusty movie lot here, a young man sits in front of a computer, showing off a three-dimensional rendering of the collapse of the World Trade Center. It was assembled by merging the blueprints for the twin towers — the before-picture, you might say — with a vast collection of measurements, including some taken with infrared laser scans from an airplane 5,000 feet above Lower Manhattan, just days after 9/11.

With a few clicks, Ron Frankel, who has the title pre-visualization supervisor for Oliver Stone's new 9/11 film, begins to illustrate the circuitous path that five Port Authority police officers took into the trade center's subterranean concourse, until the towers above them fell, killing all but two.

As Mr. Frankel speaks, behind his back a burly man has wandered through the door. He is Will Jimeno, one of the two officers who survived. He has been a constant presence on the movie set, scooting from here to there in a golf cart, bantering with the actor playing him and with Mr. Stone, answering questions and offering suggestions — a consultant and court jester. But he has never seen this demonstration before, he says, pulling up a chair.

Mr. Frankel, continuing with his impromptu show-and-tell, says the floor beneath Mr. Jimeno, Sgt. John McLoughlin and their three fellow officers dropped some 60 feet, creating a 90-foot ravine in the underground inferno. The difference between instant death and a chance at life, for each of the men, was a matter of inches.

Mr. Jimeno sits quietly, absorbing what he's just seen and heard. His eyes moisten. "I didn't know this," he says. "I didn't know this. I didn't know there was a drop-off here. This is an explanation I never knew about." He pauses. "We try not to ponder on it, because we're alive. But it answers some questions. That, really, played a big part in us being here." The countless measurements taken and calculations made by scientists and government agencies helped ground zero rescue workers pinpoint dangerous areas in the weeks after the attacks. The data also provided a fuller historical record of how the buildings collapsed and lessons for future architects and engineers.

Only a movie budgeted as mass entertainment, though, could harness all that costly information to reconstruct the point of view of two severely injured and bewildered men, who didn't even know the twin towers had been flattened until rescuers lifted them to the surface many hours later.

Their story, and those of their families, their rescuers and the three men killed alongside them, is the subject of Mr. Stone's "World Trade Center," which Paramount plans to release on Aug. 9.

The quandary that Paramount executives face is a familiar one now, a few months after Universal's "United 93" became the first 9/11 movie to enter wide theatrical release: How do you market a movie like this without offending audiences or violating the film's intentions? Carefully of course, but "there's no playbook," said Gerry Rich, Paramount's worldwide marketing chief. In New York and New Jersey, for example, there will be no billboards or subway signs, which could otherwise hit, quite literally, too close to home. And the studio is running all of its materials by a group of survivors to avoid offending sensibilities.

But Paramount, naturally, wants as wide an audience as possible for this film.