#kelvin-helmholtz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Stunning Kelvin-Helmholtz clouds at sunrise this morning. Looking towards Ireland’s Eye from Portmarnock Beach, Co. Dublin. These clouds have a distinct, wave-like pattern, almost like ocean waves in the sky. They form when there is a difference in wind speed or direction between two layers of air, creating a rolling, wave effect.

📸 by @ann.bruen @AnnBruen

#@ann.bruen#@AnnBruen#Kelvin-Helmholtz#Sunrise#Portmarnock#Dublin#Visit Ireland#Visit Dublin#Ireland#Photography

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kelvin-Helmholtz clouds. (Larger).

#cloud#clouds#kelvin-helmholtz#kelvin-helmholtz clouds#sky#atmosphere#troposphere#phenomena#nature#natural phenomena#atmospheric phenomena

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

We report: just a minute ago, the sky was a perfect blue, but now that we look again, all sorts of intruders have appeared. A little bit further west, the cloud cover is impressively dense. In the east, the horizon is still completely clear. We are giving it two minutes more.

#reports from unknown places#reports#digital art#illustration#sky#weather#artists on tumblr#image description in alt#clouds#cirrus intortus#altocumulus#and a big star is with us today#kelvin-helmholtz instability#although it is very small at the bottom here#(the wave pattern)

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOUND THE ONLINE DITHERING TOOL so here's my oq mimiz. old-ass qou who's been working in corru fluid dynamics since corrucystic tech has existed. heard the bright cousins invented powered flight that doesn't use the dull (????) and sprinted through the contrivance to see how that could possibly work. the only thing they were more excited to find out about than "orange dye" was "aerodynamics."

probably has worked with dullzkovik quite a bit and is kind of mad that he's a household name and they're not even though they invented, like, architectural circulation. mimiz thinks of themself as a little twisted (TM) with a vel's sense of humor, but they are incapable of being anything other than sunny and pleasant in person. this is lucky because they strongarmed their way into being an envoy for the tech sharing initiative.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kelvin-Helmholtz and the Sun

Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities (KHI) are a favorite among fluid dynamicists. They resemble the curls of a breaking ocean wave -- not a coincidence, since KHI create those ocean waves to begin with -- and show up in picturesque clouds, Martian lava coils, and Jovian cloud bands. (Image credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/NRL/Guillermo Stenborg and Evangelos Paouris; research credit: E. Paouris et al.; via Gizmodo) Read the full article

#coronal mass ejection#fluid dynamics#instability#Kelvin-Helmholtz instability#magnetohydrodynamics#physics#science#solar dynamics

59 notes

·

View notes

Note

trick or treat! 🧙

OHOHO! Happy Halloween! I could just give you a candy emoji but I prefer a more tangible treat in the form of a really cool cloud!

This one is called a fluctus! See those little bumps or waves at the top? Those are formed when wind above and below the cloud flows at different speeds. They’re pretty rare, especially an example as clear as this one.

That wave shape is quite visible, especially towards the right. In my top 10 cloud catches. Now you get to have it too.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

buddy the last 12 years of my life has been observations of KH

#kh#my posts#weather#this is about kelvin-helmholtz waves in clouds and fluids#please look it up bc theyre really cool they look like cartoon ocean waves in the clouds#my best friend made the joke first and i stole it lol#thank you dakota i love you dakota lets get married youre the best dakota#<- contractually obligated to write that

13 notes

·

View notes

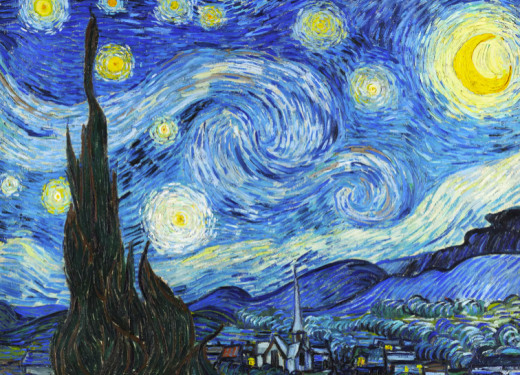

Photo

Spaceweather.com Time Machine - September 27, 2023

VAN GOGH WAVES IN THE MAGNETOSPHERE: When Vincent van Gogh painted "The Starry Night" in 1889, little did he know he was working at the forefront of 21st century astrophysics. A paper recently published in Nature Communications reveals that the same kind of waves pictured in the famous painting can cause geomagnetic storms on Earth.

Physicists call them "Kelvin Helmholtz waves." They ripple into existence when streams of gas flow past each other at different velocities. Van Gogh saw them in high clouds outside the window of his asylum in Saint-Rémy, France. They also form in space where the solar wind flows around Earth's magnetic field. "We have found Kelvin-Helmholtz waves rippling down the flanks of Earth's magnetosphere," says Shiva Kavosi of Embry–Riddle Aeronautical University, lead author of the Nature paper. "NASA spacecraft are surfing the waves, and directly measuring their properties."

This was first suspected in the 1950s by theoreticians who made mathematical models of solar wind hitting Earth's magnetic field. However, until recently it was just an idea; there was no proof the waves existed. When Kavosi's team looked at data collected by NASA's THEMIS and MMS spacecraft since 2007, they saw clear evidence of Kelvin Helmholtz instabilities. "The waves are huge," says Kavosi. "They are 2 to 6 Earth radii in wavelength and as much as 4 Earth radii in amplitude.” ...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do these clouds look like they are going to swirl like ocean waves rolling in a pattern?

Shot on 26-09-2024, Thursday in Mumbai.

0 notes

Text

Saw some wave clouds when I was running the other day.

0 notes

Photo

Kelvin Helmholtz clouds look kind of like waves. I saw some very early this morning.

897 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kelvin-Helmholtz clouds at dawn by Geraint Smith. (Larger).

#cloud#clouds#kelvin-helmholtz#kelvin-helmholtz clouds#sky#atmosphere#troposphere#phenomena#nature#natural phenomena#atmospheric phenomena#new mexico#america#united states

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

ayee could you match these cool wave clouds? (they're called kelvin-helmholtz clouds) ⋆.ೃ࿔☁️ ݁ ˖*༄

-plant gee

this gerard as these cool wave clouds !!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Besides the delightful penguins, Ukrainian polar researchers in Antarctica at Vernadsky Station wanted to share the cloud phenomenon behind them. The wavy clouds are caused by the "Kelvin-Helmholtz instability: when two flows with different densities and speeds meet, turbulence appears at their boundary."

#Ukraine#Antarctica#penguins#nature#clouds#Ukrainian scientists#weather#vernadsky station#vernadsky#national antarctic scientific center

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

feel free to add pictures if u wanna!!!!!!! i love clouds forever and ever and ever

#From your favorite autistic weather nerd. Please reblog#weather#wx#clouds#meteorology#mine is cirrocumulus btw :3

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

kelvin-helmholtz wave clouds in the right middle of that top line of clouds btw. if u even care

10 notes

·

View notes