#kantian ethics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A bit of train study to catch up with my readings

#no longer easing back into routine im fully in#studying for a Kantian ethics summer school but also for my completely unrelated state exam#girl blogging#alternative girl#chaotic academia#study blog#studyblr#tired academia aesthetic#academiacore#light acadamia aesthetic#train travel#kant#kantian ethics#philosophy#study with me#studyabroad#studyspo#study aesthetic#train#study inspiration#study abroad

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Guilt

The philosophy of guilt examines the nature, origin, and ethical implications of guilt as a complex emotional and moral phenomenon. Guilt is a feeling of responsibility or remorse for some offense, crime, or wrong, whether real or imagined. Philosophers explore guilt in the context of morality, psychology, and existentialism, seeking to understand its role in human behavior, ethical decision-making, and the development of personal and collective identity.

Key Concepts in the Philosophy of Guilt:

Definition of Guilt:

Moral Emotion: Guilt is typically defined as an emotional response to the belief that one has violated a moral or ethical standard. It is often distinguished from related feelings like shame, which involves a negative evaluation of the self, whereas guilt involves a negative evaluation of a specific action.

Types of Guilt: Philosophers and psychologists often differentiate between different forms of guilt, such as:

Personal Guilt: Feeling responsible for one’s own actions.

Collective Guilt: Feeling guilt for actions committed by a group to which one belongs.

Existential Guilt: A more generalized feeling of guilt tied to one’s existence or perceived failings in living authentically.

Ethical Implications:

Guilt as a Moral Compass: Guilt is often seen as a mechanism that helps individuals adhere to ethical norms. It can act as a motivator for moral behavior, encouraging individuals to make amends and avoid repeating wrongful actions.

Excessive vs. Deficient Guilt: The appropriate amount of guilt is a subject of ethical debate. Excessive guilt can lead to unhealthy psychological states, while too little guilt may indicate a lack of moral sensitivity.

Philosophical Perspectives:

Kantian Ethics: In Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy, guilt is related to the failure to adhere to one’s duty or the moral law. Kantian guilt arises from recognizing that one’s actions have violated the categorical imperative, the fundamental principle of moral duty.

Existentialism: Existentialist philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre explore guilt in the context of freedom and responsibility. Sartre argues that guilt (or "bad faith") arises when individuals deny their freedom and responsibility by conforming to societal norms or by failing to live authentically.

Psychoanalysis: Sigmund Freud and other psychoanalytic thinkers view guilt as a product of internal conflicts, particularly between the id, ego, and superego. Freud suggests that guilt arises from the tension between instinctual desires and the internalized moral standards of society.

Guilt and Responsibility:

Moral Responsibility: Guilt is closely tied to the concept of moral responsibility. Philosophers debate whether individuals should feel guilty only for actions they directly control or also for unintended consequences and actions by others (as in collective guilt).

Legal vs. Moral Guilt: Legal systems often distinguish between legal guilt, which is determined by the law, and moral guilt, which is a personal or societal judgment based on ethical standards.

Guilt and Redemption:

Amends and Forgiveness: The philosophy of guilt also explores the processes of atonement and forgiveness. Can guilt be resolved through acts of redemption or making amends, and how do these actions influence personal and social relationships?

Religious Views: Many religions address guilt and its resolution through rituals, confession, and forgiveness. In Christianity, for example, guilt is often linked to sin, and redemption is achieved through repentance and divine forgiveness.

Psychological Aspects:

Healthy vs. Pathological Guilt: Psychologists study the impact of guilt on mental health, distinguishing between guilt that is a healthy response to wrongdoing and guilt that becomes pathological, leading to depression, anxiety, or obsessive behavior.

Guilt and Empathy: Guilt can be seen as an expression of empathy, where an individual feels guilt because they understand and internalize the harm they have caused to others.

Collective and Historical Guilt:

Collective Guilt: This concept involves feeling guilt for actions committed by a group, such as a nation or community. It raises questions about the extent to which individuals are responsible for the actions of others and the moral implications of historical injustices.

Guilt and Memory: Philosophers explore the role of guilt in collective memory and historical consciousness, particularly in the context of war crimes, genocide, and colonization.

Guilt and Identity:

Formative Role of Guilt: Guilt can play a significant role in the formation of personal and collective identity. It can shape one’s moral self-conception and influence how individuals relate to their past actions and to others.

Guilt and Self-Perception: The experience of guilt often leads to self-reflection and can influence how individuals see themselves in relation to their moral values and the expectations of society.

The philosophy of guilt offers a deep exploration of one of the most profound aspects of human emotional and moral life. By examining guilt through ethical, psychological, and existential lenses, philosophers seek to understand how this emotion influences behavior, shapes moral responsibility, and contributes to both individual and collective identity. Guilt is not only a personal experience but also a social and historical phenomenon, with significant implications for ethics, law, and culture.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ethics#psychology#Guilt#Moral Responsibility#Ethical Emotions#Kantian Ethics#Existentialism#Collective Guilt#Psychoanalysis#Redemption#Forgiveness#Legal vs. Moral Guilt#Pathological Guilt#Historical Guilt#Guilt and Identity#Guilt and Empathy#Bad Faith

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terry Pratchett was a Kantian? This is literally just the second formulation of the Categorical Imperative: the Formula of Humanity.

“And sin, young man, is when you treat people like things. Including yourself. That’s what sin is.”

“It’s a lot more complicated than that –”

“No. It ain’t. When people say things are a lot more complicated than that, they means they’re getting worried that they won’t like the truth. People as things, that’s where it starts.”

“Oh, I’m sure there are worse crimes –”

“But they starts with thinking about people as things…”

(Granny Weatherwax, to Pastor Mightily Oats, Carpe Jugulum, Terry Pratchett.)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fuck Kant. I Kant do this presentation. (It’s due in 2 and a half hours so I have no choice in the matter, but my opinion stands)

obviously Kant doesn’t support utilitarianism because he would classify this as “good” even though it is generating distinctively unpleasant feelings.

#homme would never put me through this#Why must you be this way Immanuel#I am blaming this on Kant himself because I love my philosophy in lit teacher and it’s not his fault he has to give a final#Kant#immanuel kant#Kantian ethics

1 note

·

View note

Text

#immanuel kant#poll time#david hume#john locke#voltaire#mary wollstonecraft#rousseau#philosophy#ethics#enlightenment#kantianism#categorical imperative#196#categorical imperatives#morality#children

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

they call me the scannerrrrrrrrrrr

#hi ravie. havent seen you in a while#cherryart#oc tag its ravie#we learned this (kantian ethics) in school but you were too busy drawing an arctic fox#sfw furry

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

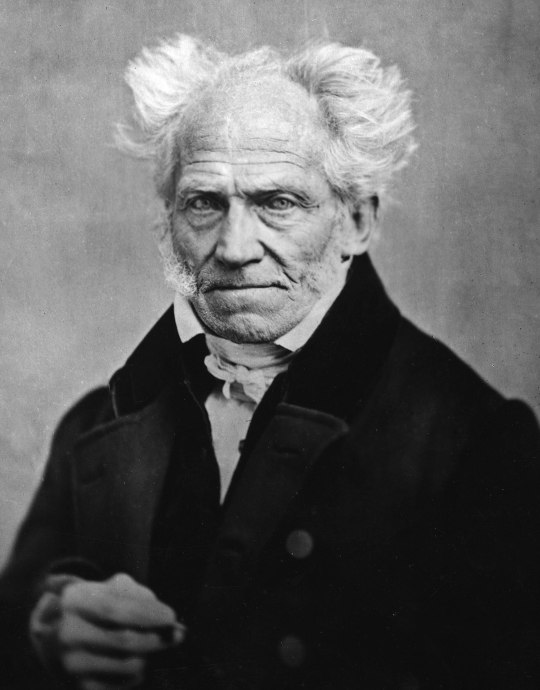

“A high degree of intellect tends to make a man unsocial.”

Arthur Schopenhauer was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation.

#Pessimism#Will and Representation#Metaphysics#Ethics#Existentialism#Philosophy of Mind#Kantianism#Aesthetics#Solipsism#Nihilism#Idealism#Compassion#Individualism#World as Illusion#Transcendental Idealism#Suffering#The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason#Eastern Philosophy Influence#Art and Beauty#Critique of Hegel's Philosophy#today on tumblr#quoteoftheday

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Duty

The philosophy of duty, often referred to as "deontology," explores the nature and basis of moral obligations and the principles that define actions as morally required or prohibited. In this framework, duty represents an ethical imperative to act in accordance with certain principles or rules, regardless of personal desires or outcomes.

Key Aspects of the Philosophy of Duty

Moral Obligation: Duty is often seen as an inherent moral obligation that individuals must follow to act ethically. Unlike approaches that focus on outcomes or character, duty-based ethics focus on adherence to rules or principles as the basis for moral action.

Deontological Ethics: Immanuel Kant is a major figure in duty-based ethics. He argued that moral laws are categorical imperatives, meaning they apply universally and unconditionally. According to Kant, actions should be performed out of respect for moral law, not based on their consequences.

Intention and Autonomy: In duty-based ethics, an individual’s intention is crucial. Doing something because it is one’s duty reflects moral autonomy, as opposed to being driven by external forces, emotions, or self-interest.

Universality: Deontology emphasizes the idea that duty is universal. Kant’s categorical imperative holds that one should act only according to maxims that can be universally applied, meaning actions should be considered acceptable if everyone were to act in the same way.

Rights and Justice: Duty-based philosophies often emphasize individual rights and justice. Duties define what actions we owe to others, and by respecting duties, we uphold justice, treating others with fairness and respect.

Conflicting Duties: One challenge in duty-based ethics is resolving conflicts between duties. For example, one may face a conflict between the duty to tell the truth and the duty to protect another person’s wellbeing. Different approaches to duty provide various solutions, sometimes allowing for exceptions, or ranking duties in order of importance.

Beyond Self-Interest: The philosophy of duty implies a transcendence of self-interest, prioritizing actions that benefit others or society, even at personal cost. Duty-based ethics emphasizes that one’s duty is to do what is morally right, even when it may conflict with personal desires or interests.

Duty in Different Philosophical and Cultural Contexts

Eastern Philosophies: In Hinduism, the concept of dharma represents duty aligned with moral, social, and cosmic laws. Similarly, Confucianism emphasizes social duty, particularly in relationships, where acting out of respect and fulfilling one’s role in society reflects virtue.

Existentialism and Duty: Existentialist thinkers challenge traditional concepts of duty by emphasizing individual freedom and choice. Jean-Paul Sartre argued that individuals must create their own values rather than conforming to pre-existing moral codes.

Modern Perspectives: Contemporary deontologists build on Kant’s ideas but often adapt them to address social justice and rights issues, such as the duty to protect human rights, environmental ethics, and global responsibility.

Duty and the Ethics of Care

While traditional duty-based ethics focuses on impartial rules, the ethics of care emphasizes duty within personal relationships, focusing on empathy, compassion, and the obligations that naturally arise in caring relationships.

The philosophy of duty invites us to act beyond immediate gain, considering what it means to act rightly and fulfill moral obligations for their own sake. In doing so, it shapes how we conceive our responsibilities to ourselves, others, and society.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ethics#Philosophy of Duty#Deontological Ethics#Moral Obligation#Kantian Ethics#Categorical Imperative#Moral Philosophy#Ethics of Care#Moral Autonomy#Duty and Responsibility#Rights and Justice

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello people. I have to rant about a really annoying experience i had recently.

In short, a woman in a discord server started saying some very rude things to me; i was talking about how to further the progress of human civilization by way of kantian ethics and therefore objective morality, applied in practice by marxist-keynesian economics and hobbesian monarchism, i barely began my explanation of morality (through several paragraphs of description) before this tgirl started throwing...and i mean no insult by this, bad faith arguments at me, in essence all her arguments boiled down to "your system of morality is flawed because i can imagine a person who is completely depressed, irrational, self-destructive, probably suicidal, indifferent and lazy, who wouldn't care too much about your arguments and wouldn't follow your morality system, and would also not really be interested in contributing to your society for even the sake of their own good! Gotcha!!", or at least that's what i understood, insisting also on absurd points such as "so something should not be done just because it is wrong?!" And i answered quite swiftly "yes, of course" and she went on to say more stuff, and comparing herself to this hipothetical person, about how she supposedly doesn't have goals (and then she went on to list her goals in life) and is irrational and she tried to use this as some sort of way to prove that she doesn't have to contribute to any bettering of human society somehow. Honestly, i can't even begin to explain why i DETEST this attitude, and i would use stronger words if i didn't want to stop myself from being disrespectful, like, it would be absurd to see the horrendous neoliberal hellscape we all find ourselves in, the imperialist purgatory, the self-destructive system of capital, to see the constant opression coming from conservatism, and to have this society call us "crazy bastards" for wanting to resist, for knowing higher morality that could lead humanity forward, and to just resign to saying "i am crazy and depressed and choose to do nothing productive about any of this!1!1!1"; it made me sick to my STOMACH, to know that there are other trans people in this world, who see even just a fraction of the self-destruction of this system, and do nothing at all "umm actually i am lead by whims" and just throw destructive criticism at someone who was reciting what seems to be the most productive method at arriving to a sustainable civilization. It's like she became exactly what the comservatives say we are, idiotic self-destructive degenerates who can do nothing right...

May god save us.

#feminism#transfem#lgbt pride#funny#socialism#lgbtq community#marxism#john maynard keynes#karl marx#vladimir lenin#thomas hobbes#monarchism#immanuel kant#kantianism#ethics#morality#anti capitalism#lgbt#against self-destruction#communism#left communism#socialist politics#social welfare#welfare states#marxism leninism#depression#tw sui talk#tw politics#tw rant#philosophy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Presentation on 93

Professors, friends, and esteemed guests,

I have the honour to present to you today an unparalleled book: Ninety-Three by Mr. Victor Hugo, whom we all recognise as a giant—not just of French letters, but of the world. To our great shame, although other works by Mr. Hugo are frequently read today, Ninety-Three, his last novel, has been largely forgotten; indeed, at this present moment no reputable publishing company is printing it in the English language.

I am here for the express purpose of reviving Anglophone interest in Ninety-Three. I consider this book a work of French Romanticism par excellence, for several reasons. First, it is an exercise of Hugo's literary theory, set forth as early as 1827 in the Preface to Cromwell, though never until now so perfectly demonstrated; second, in it we see the author’s reflections on a momentous point in history, the French Revolution, itself full of dramatic and philosophical potential. Additionally, the book is well-paced— which is perhaps the most difficult achievement of all for a work of this author. In sum, this book has everything that is required for a novel to ascend to the literary pantheon of the western canon: it has drama; it has depth; it is entertaining; it is true. Let us hasten, then, to place it where it deserves to be.

To understand the genius of Ninety-Three, one must understand the symbolic significance of its characters. But before I go any further, let us provide a general idea of the plot. In one sentence, it is a tale of the struggle between republicans and royalists in the Vendée (that is, Brittany), during the height of the Reign of Terror—hence the name, which is short for Seventeen Ninety-Three. Hugo divides the novel into three parts: At Sea, In Paris, and In la Vendée.

The story begins with a sort of prologue, an encounter between the republican Battalion of the Bonnet-Rouge and a Briton peasant woman and her three children, who are fleeing the war. They are quickly adopted by the battalion. We shall soon see why they are important. For the present our attention is redirected to the island of Jersey, an English possession, where a French royalist crew is preparing for a secret expedition. An old man boards the ship. He is in peasant dress, but by his demeanor seems to be an aristocrat. In the rest of At Sea we become acquainted with this jolly royalist crew—only to see them all perish in a naval battle before they ever reach the coast of France. Yet the old man escapes with the sailor Halmalo, and they land in Brittany in a little rowboat. He sends Halmalo off to rouse a general insurrection. Then, upon reading a placard, learns that his presence in Brittany has been known, and that someone named Gauvain is hunting him down, which sends him into a shock. Despite his dire situation, our protagonist is recognised by an old beggar named Tellemarch, who conceals him. We discover that he is none other than the Marquis de Lantenac, Prince in Brittany, coming back to lead the rebellion.

In the second part, In Paris, we are introduced to another character: Cimourdain. Cimourdain is a revolutionary priest, a man of iron will, with one weakness only: his affection for a pupil he had long ago, who was the grand-nephew of a great lord. At this period, however, Cimourdain dedicated himself completely to the revolution. Such was his formidable reputation that Cimourdain was able to intrude upon a meeting of the three terrible revolutionary men, Danton, Marat, and Robespierre, and cause his opinion to prevail among them. Robespierre then appoints Cimourdain as a delegate of the Committee of Public Safety, and sends him off to deal with the situation in Vendée. He is told that his mission is to watch a young commander, a ci-devant noble, named Gauvain. This name also sends Cimourdain into a shock.

Gauvain, in fact, is none other than the grand-nephew of the Marquis de Lantenac, in whose household the priest Cimourdain had been employed. Although they have not met for many years, there is a close bond between the master and pupil, and both adhere to the same revolutionary ideal. Hugo has set the stage. In the last part, In la Vendée, these epic forces are hurled against each other in the siege of the Gauvain family’s ancestral castle, La Tourgue. On the one side, we have the republican besiegers, Gauvain and Cimourdain, and on the other, the Marquis de Lantenac and his Briton warriors, the besieged. The Marquis has one last card to play: he has, as hostages, the children of the Battalion of the Bonnet-Rouge. For the safety of his party, he offers the life of the three children, whom he has placed in the chatelet adjoining the castle of La Tourgue, which will be burned upon attack. The republicans refuse. The siege begins, bloody for the republicans, hopeless for the royalists. At the last moment, by a stroke of fate the royalists contrive to escape, leaving behind an exasperated republican army, and a burning house. The republicans try to rescue the children, but find this impossible, as they can neither scale the walls of the chatelet, nor open the iron door that leads to it. As this is happening, the Marquis hears the desperate cries of the mother in the distance. Beyond all expectation, he returns, opens the door with his key, steps into the fire, and saves the children. Thereupon he is seized by Cimourdain, who proclaims that Lantenac will be promptly guillotined. Yet unbeknownst to Cimourdain, Lantenac’s heroic act of self-sacrifice set off a crisis of conscience in the gentle Gauvain, who fought for the republic of mercy, not the republic of vengeance. The final battle takes place in the human heart.

I will not divulge the ending. Already we can see that these characters are at once human, and more than human. “The stage is an optical point,” says Hugo in the Preface to Cromwell, “Everything that exists in the world—in history, in life, in man—should be and can be reflected therein, but under the magic wand of art.” Men assume gigantic proportions. They become ideas. The three central characters each represent a force. In the lights and shadows of their souls, we have symbols of the lights and shadows of a whole age. The fifteen centuries of feudalism, the Bourbon monarchy, the France of the past, when condensed into an object is the looming castle La Tourgue, and when incarnate is Lantenac. The twelve months of the revolutionary terror, the Committee of Public Safety, the France of the moment, is as an object the guillotine, as a man Cimoudain. The immense future is Gauvain. Lantenac is old; Cimourdain middle-aged; Gauvain young.

Let us look at each of these characters in turn.

I admit that Lantenac is my favourite character. In his human aspect he is impressive, and very compellingly written. Almost immediately upon introduction, he manifests a ferocious justice in the affair of Halmalo’s brother, a gunner who endangered the whole ship by his neglect, and who saved it in a terrifying struggle between vis et vir, between an invincible brass carronade and frail humanity. Lantenac awarded this man the Cross of Saint-Louis, and then had him shot. To the vengeful Halmalo, his justification is this: “As for me, I did my duty, first in saving your brother’s life, and then in taking it from him [...] He has failed his duty; I have not failed mine.” This episode sums up Lantenac’s character. True to life and true to the principle of romantic drama, Lantenac contains both the grotesque and the sublime, sometimes even in the same action. Like the Cromwell that inspired in posterity such horror and admiration, he shoots women, but saves children. He martyrs others, but is at every point prepared to be the martyr.

As an idea he is the ultimate embodiment of the Ancien Régime. Though himself unpretentious, Lantenac is perfectly aware of the role he must play. He demonstrates perfectly, unlike conventional aristocrats in literature, the principle of noblesse oblige and the justice of the suum cuique. He believes that he is the representative of divine right, not out of arrogance, but as a matter of fact. “This is the question,” he tells Gauvain in their first and last interview, “to be a Great Kingdom, to be the ancient France, [is] to be this magnificent land of system [...] There was something fine and noble in this system. You have destroyed it [...] like the miserable ignoramuses you are [...] Go! Do your work! Be the new man! Become pygmies! [...] But leave us great.” The force which animates Lantenac is his duty, merciless, towards the old monarchical order—until the principle was overcome by the man, who was still able to be moved by helpless innocence.

The first thing that Hugo felt it was necessary to know about Cimourdain is that he is a priest. “He had been a priest, which is a solemn thing. Man may have, like the sky, a dark and impenetrable serenity; that something should have caused the night to fall in his soul is all that is required. [...] Cimourdain was full of virtues and truth, but they shine out against a dark background.” There is an admirable purity about him: it is symbolic that we always see him rushing into the thick of battle, but never firing his weapon. He aids the poor, relieves the suffering, dresses the wounded. By his virtues he seems Christlike, but unlike Christ, his is an icy virtue, the virtue of duty, not love; a justice which knows not mercy—“the blind certainty of an arrow,” which imparts to this sublimity a touch of the ridiculous. It is a short step from greatness to madness. Still, there remains some humanity in Cimourdain, on account of his love for Gauvain. Through this love that he is able to live, as a man, and not merely as the mechanical execution of an idea.

On the surface Cimourdain has renounced his priesthood. But, Hugo reminds us, “once a priest, always a priest.” He is still a priest, but a priest of the Revolution, which he believes to have come from God. There is a similarity between Cimourdain and Lantenac, though they are on the two diametrically opposed sides of the revolution. Both are bound by duty to their cause. Both are ferocious. When Robespierre commissioned Cimourdain, he answered: “Yes, I accept. Terror against terror, Lantenac is cruel. I shall be cruel. War to the death against this man. I will deliver the Republic from him, so it please God." Quite appropriately he is represented by the image of the axe—realised in the guillotine erected in the final chapter. As with Lantenac, the Cimourdain of relentless revolutionary justice eventually finds himself face to face with the human Cimourdain, the spiritual father of Gauvain, the embodiment of mercy.

Gauvain at a glance seems to be a character of simple conception: his defining characteristic is an almost angelic goodness. He is also the pivotal point in the story: on one hand, he is the son of Cimourdain, a republican, and on the other, he is the son of the Gauvain family, Lantenac’s heir. Through him, we are reminded that the Vendée is a fratricidal war. Allusions abound in the novel, for example, when Cimourdain declared his brotherhood with the royalist resistors, a voice, implied to be Lantenac’s, answered, “Yes, Cain.” Gauvain finds himself caught in the middle of such a frightful war. At first, he was able to overlook his kinship with Lantenac, on account of the older man’s monstrosities, but with Lantenac redeemed by his self-sacrifice, it becomes impossible to ignore his threefold obligation: to family, to nation, and to humanity. It is because of this that duty, which seemed so plain to Cimourdain, rose “complex, varied, and tortuous” before Gauvain. The fact is, far from being simple, Gauvain's goodness is neither effortless nor plain, and we are reminded that the most colossal battles of nobility against complacency often happen in the most sensitive of consciences.

Indeed, the triumph of Gauvain is a triumph of the moral conscience, the light which is said to come from the great Unknown, over the dismal times of revolution and internecine strife, “in the midst of the conflagration of all enmity and all vengeance, [...] at that instant [...] when everything becomes a projectile [...], when [...] justice, honesty, and truth are lost sight of [...]” To Hugo, the Revolution is a tempest, in the midst of which we find its tragic actors, forbidding figures as Cimourdain, Lantenac, and the delegates of the Convention, some supremely sublime, some utterly grotesque, and many both: “a pile of heroes, a herd of cowards.” But, at the same time, “The eternal serenity does not suffer from these north winds. Above Revolutions, Truth and Justice reign, as the starry heavens above the tempest.” Gauvain finally comes to peace with this realisation, and we hear him saying, “Moreover, what is the tempest to me, if I have the compass? And what difference can events make to me, if I have my conscience?”

But Ninety-Three is, after all, a tragic book. We might ask whether it is not the case that Gauvain is too much of an idealist. He wishes to found a Republic of Intellect, where perpetual peace eliminates all war, and where man, having passed through the instruction of family, master, country, and humanity, finally arrives at God. “Gauvain, come back to earth,” says Cimourdain. To this Gauvain cannot make a reply. He can only point us upwards, by self-denial, and by his love, towards the ideal.

And the task of the novel is no more than this, this reminder of the reality of life. The drama was created, as the Preface to Cromwell declares, “On the day when Christianity said to man: ‘Thou art [...] made up of two beings, one perishable, the other immortal, [...] one enslaved by appetites, cravings and passions, the other borne aloft on the wings of enthusiasm and reverie—in a word, the one always stooping toward the earth, its mother, the other always darting up toward heaven, its fatherland.’” And did not Ninety-Three achieve this? The legend of La Vendée, like the stage, takes crude history and distills from it reality. Let us conclude with this passage from the novel itself:

“Still, history and legend have the same end, depicting [the] man eternal in the man of the passing moment.”

#victor hugo#ninety-three#quatrevingt-treize#1793#reign of terror#vendée#romanticism#essay#lantenac#gauvain#cimourdain#in an earlier draft I also compared Gauvain to Alyosha Karamazov in a passing comment but I had to take that out for the sake of time#also Cimourdain is definitely a Kantian but doesn’t seem that Hugo approves of Kantian ethics#on the other hand Hugo isn’t Aristotelian either#because in his works reason and the passions are always diametrically opposed#whereas Aristotle / St Thomas would have said that the passions could be trained by reason

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOT the Abraham v. God over Sodom and Gomorrah reference, this book is KILLING me

#Incredible#I’m really enjoying it!! And I’m sad I’m almost done :/#There’s been lots of justice#and that is well#But perhaps my favorite truth so far is Wanda’s realization that you have to do the work without knowing what reward may come#Idk if it’s accurate to call that virtue ethics exactly (it’s not Kantian is it??) but it’s a deliciously moral reason for doing something!#And it’s a lot better than vengeance lol#There’s a certain casting your bread upon the waters attitude about it#Also I am still holding out for some redemption arcs baby#*insert the meme about the fatal Christian need for redemption and reconciliation#Spinning silver#Peace reads books

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

im gonna get this essay out the way dead quick and then go get cinnamon rolls as a self-reward and then ill get back to being a real person ill be back in maybe 2 hours

#its only a 2000 word essay but its on ethics and ive been doing ethics against my will for 3 years im over it#i have all of kantian ethics and utilitarianism memorised i could pretty much do this essay blindfolded i just need to. do it#which i do not want to#i need to make a tag just to complain about exams tbh im prob so annoying about them whoops#cinn talks about his day#<- were sticking with my regular oversharing tag for now

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

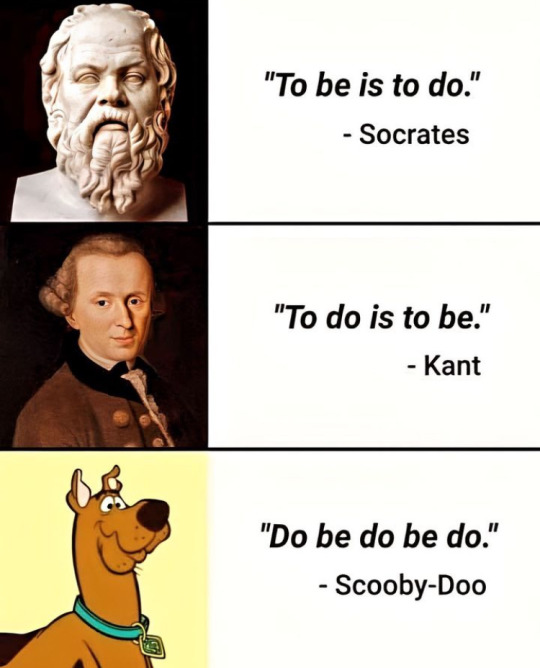

one is a beloved and respected philosopher, one is adored by children, and yet i am both

#immanuel kant#socrates#scooby doo#philosophy#ethics#kantianism#categorical imperative#to do is to be#to be is to do#196#morality

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

americans find all your local philosophy bros who love the trolley problem and bet them they can't reconcile utilitarianism and not murdering two thirds of the supreme court

#avoid kantians but do that the rest of the time too#find out which of them actually care about ethics and which ones just enjoy imagining scenarios where all characters are on equal standing#and they don't have to think about their own privilege#us politics#supreme court

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I LOVE PATHETIC FALLACY !!!! FUCK YEAH DUDE WHEN THE SUN COMES OUT !!!! FUCK YEAH !!!!!!!

2 notes

·

View notes