#avoid kantians but do that the rest of the time too

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

americans find all your local philosophy bros who love the trolley problem and bet them they can't reconcile utilitarianism and not murdering two thirds of the supreme court

#avoid kantians but do that the rest of the time too#find out which of them actually care about ethics and which ones just enjoy imagining scenarios where all characters are on equal standing#and they don't have to think about their own privilege#us politics#supreme court

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hawks and the Trolley Problem

I. What is the Trolley Problem?

The Trolley Problem is an ethical thought experiment, mostly testing outcomes and methods of achieving them. It goes like this:

There is a runaway trolley barreling down the railway tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person on the side track.

You have two options:

A. Do nothing and allow the trolley to kill the five people on the main track. B. Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will kill one person.

What is the right thing to do?

There are schools of thought that attempt to explain this problem. A common response is to divert the trolley, actively making the choice to kill one person to save five. In this scenario, you are making an active choice to kill someone for the ‘greater’ outcome, which assumes that the best outcome is to save as many as possible. We will call this choice the Utilitarian option.

The second option is to do nothing and let the five people die. Why? Because then it’s a matter of letting the trolley do what it intends to and not actually pulling a lever and condemning a person to death. By choosing inaction in order to not murder anyone, you could stay true to a moral of never killing anyone. This is the Kantian option.

Of course, the Trolley Problem is customizable - people add all sort of features, like instead pushing someone in front of the trolley to stop it, or including knowing someone in the line up of potential dead. It doesn’t even have to be a trolley - all it asks is what is the right thing to do? And, of course, what is the value of a human life.

II. What is Hawks’s Dilemma?

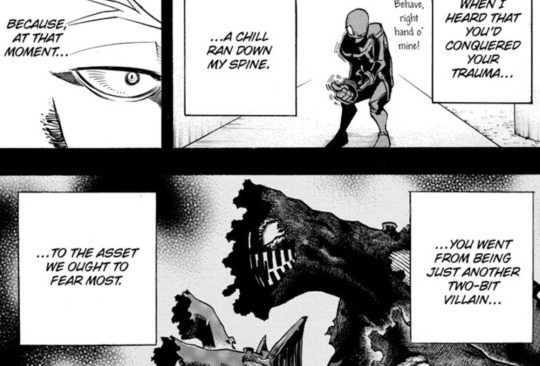

Hawks has infiltrated the Paranormal Liberation Front and managed to manipulate Twice into befriending him and providing him with information leading to a preemptive strike by the Heroes against the PLF. However, he feels that Twice is a greater harm than just an information source and thus has used his friendship to kidnap Twice, keeping him and his quirk away from a battlefield where he would easily be able to overwhelm the hero forces. Without Twice, the villains are far more easily beatable.

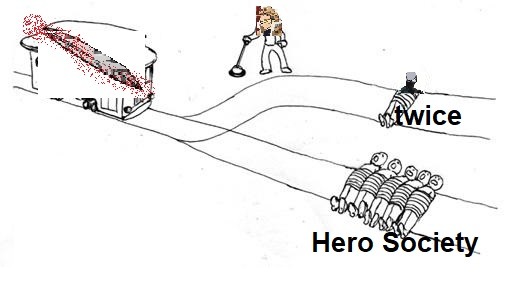

BNHA 263 ends with Hawks threatening Twice with his feather-knives and asking himself the question, internally: What is the right thing to do?

Let’s break the options down:

A. Hawks kills Twice to effectively ensure he cannot escape and help. The villains are not able to use his clones in the battle, leaving them vulnerable. Hawks ensures heroes survive the battle (assuming no unexpected things happen), and that the status quo the PLF want to topple is maintained. Low amounts of civilian casualties, hero casualties. The problems that caused this issue in the first place continue.

B. Hawks lets Twice go. Twice uses his clones to defend the PLF, ensuring more casualties for both the heroes, and possibly the PLF. Eventual massive civilian casualties. Status Quo is broken, system is broken - the problems that created this are addressed, either by further perpetuation or reduction.

There are also other factors.

Hawks knows Twice. Heroes are not typically supposed to kill villains. Hawks has referred to Twice as ‘good-natured’, and reflected it made it easier to accomplish this, yet he also seems surprised by how much Twice genuinely likes and trusts him. He also knows, on both sides, many of the people likely to die from this.

Miruko in 262 mentions that heroes hold back fighting villains - killing is not usually an action heroes are allowed or suggested to take.

And, lastly, Hawks’s choice is not solely his - up to now he has performed his duty as a tool to the Hero Public Safety Commission.

III. How the Hero System Would Tackle the Problem?

Let’s talk about what it means to be a hero.

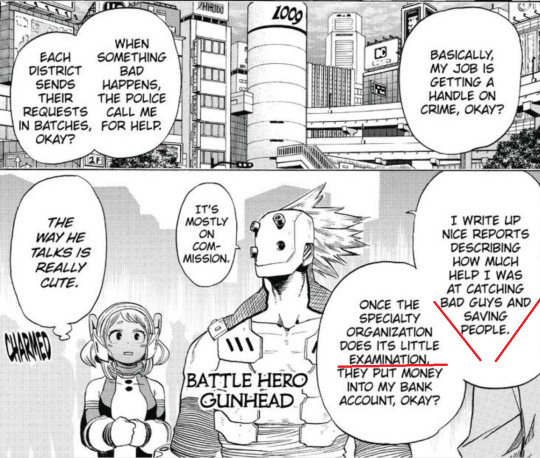

From what we’ve seen in the manga and spin off Vigilantes, there’s an actual calculation, maybe even algorithm in how heroes get paid. It is a clearly a numerical one.

The question is how exactly should anyone looking at a catastrophe begin to count the worth of human life? We don’t have exact confirmation, but it’s likely the ‘Specialty Organization’ is none other than the HPSC, or the Hero Commission as fandom likes to call them.

From previous encounters, we know that they are utilitarian in outlook, hence the way they sent Hawks to infiltrate the League. To the HPSC, the consequences of an action matter far more than the morality of the action itself. As a organization that, then, depersonalizes choices in terms of numbers and metrics, a simple calculation that five people over one intended casualty is acceptable.

Remember, the HPSC also comes out with ranks. Heroism is numbers to their system and they got the calculation.

In Japan, Professional Heroes are officially ranked by taking in account several factors such as the number of cases solved, general popularity, and level of social contribution. (bnha wiki)

In their view, Hawks would choose A. There’s no option for him otherwise. The HPSC continues to exist as long as everyone accepts their metrics and calculations. Lives, to them, have an internal quantifiable logic. So do hero actions.

Villains do, too, but only in ‘resolving’ them. As incidences.

IV. What are Lives Worth, Anyway?

The more factors we include in this problem, the more complications. A kantian viewpoint might come from someone in the Liberation Front - Twice’s quirk is amazing and far more valuable that most quirks. If we put Twice in the Trolley Problem, it’s unlikely that the five other people would have comparable quirks. Thus, simply on that basis, Twice’s ‘worth’ would be more than the others and no lever would be pulled.

For Hawks, it would be the action itself. Heroes do not kill, and while he has been conditioned into taking the HPSC’s metrics into the forefront of his decision-making all his life, the active choice to kill Twice would have consequences.

Hawks has already shown to struggle with guilt - besides the words he said after the Jeanist incident, manipulating Endeavor into coming with him just to use him as a shield against whatever the League had did disturb Hawks, just from facial expressions. He does even question that he has to perform immoral actions in order to do as the HPSC wishes. At the same time he has generally gone along with the idea that the ends justify the means.

It’s very obvious what would happen if any of us ever encountered a “trolley problem” in real life. We would panic, do something rashly, and then watch in horror as one or more persons died a gruesome death before our eyes. We would probably end up with PTSD. Whatever we had ended up doing in the moment, we would probably feel guilty about for the rest of our lives: even if we had somehow miraculously managed to comply with a consistent set of consequentialist ethics, this would bring us little comfort. ( Nathan Robinson, Current Affairs. 2017)

As I wrote this, someone mentioned The Good Place, a show that showed explored the Trolley Problem in depth. One of the conclusions it came to is that nevertheless of the circumstances it is horrifying. No matter the ethics, faced with such a problem, most people would not come away of it well. Hawks included because he is not a machine and is capable of feeling guilt either way.

If he kills Twice, he kills and betrays a friend, and saves the lives of hundreds of thousands or millions, and betraying people he has gotten to know over the course of months. But that’s a weight he’ll have to bear for the rest of his life, if he manages to survive. He’ll have to know he did what Heroes are avoidant to do; kill.

If he doesn’t kill Twice, Twice will help lead a revolution that, while addressing many of the issues Hawks sees with society, will kill Hawks’s thousands of colleagues and many innocents in the crossfire.

V. A Different Question?

The issue then is not what Hawks does, but why he has to ask this question of himself in the first place. The thing is that there are rarely only two options in any given situation.

The thing is situations are created. And so are choices. They do not come out of thin air. They are not in a self-contained vacuum. Twice was created, and so was Hawks, and so was the Commission. The choices Hawks faces right now are not removed from hundreds of years of other decisions, and powers that enact them.

If I am forced against my will into a situation where people will die and I have no ability to stop it, how is my choice a “moral” choice between meaningfully different options, as opposed to a horror show I’ve just been thrust into, in which I have no meaningful agency at all? Let’s think a bit more about who put me here and how to keep them from having diabolical power over others. ( Nathan Robinson, Current Affairs. 2017)

The thing about ascribing morality, too, to individual actions is it misses the powers of institutional forces upon our lives. What does that look like in BNHA?

It means we see Ujiko and not an Empire AFO has been building for at least a century to make sure there are systems in place creating noumus, and people like Shigaraki who exist in this world.

It means we see Endeavor and his heroism and brilliant record and not a system ignoring that a man who bought a woman to force her to have children in a genetic experiment is now the symbol of Peace and Stability for that system.

It means we see Twice as a regrettable casualty of society whose only option for acceptance was among murderers fulfilling a murder-empire and not a consequence of both AFO’s system and the Hero System to make sure people like him have no safe place in the world.

It means we see Hawks poised to kill Twice and not the organization that bought him as a child and raised him into a soldier who has to decide whether to kill one or many.

And once you realize that none of these questions, none of these options are fair or right in these terms - not the one for many, not the sparing to absolve personal guilt, you can ask the question what is right thing to do.

What I mean is maybe there shouldn’t be heroes or villains. None of that conflict should exist. There’s no rights in either view. Yes the hero system should be eradicated. But the lack of future Shigaraki envisions, and the dystopian plans AFO and Ujiko actually have, and the Liberation Army plan for, are also wrong.

Neither of the systems proposed have the right answer or the right to posit one.

The real answers are not in the right or wrongs. They’re in every other sentence. They’re in Jirou’s encouragement of Kaminari, in Shigaraki telling the League he wants them to be happy with what they love, in Keigo’s unsure smile as Jin looks at him and tells him he’s a good person for caring for his friends. The answers are in the love that ordinary people have for each other, that no manufactured conflict and institution can quantify or destroy. And that hopefully, someone will voice this.

VI. What will Hawks Answer?

The thing about this is that we aren’t sure if Keigo will fully make a decision right now. There’s a likelihood he will be interrupted. Or he will put off his decision-making and spare Twice for the moment, delaying his choice. And that’s just ignoring the fact that there isn’t one choice to make here; no, lots of them.

However, Keigo has made one personal life-changing decision in before; the HPSC has taken that choice and removed free will from it.

Self-sacrifice, after all, is both the will of the HPSC and Hawks’s true nature. If quirks are to show us the nature of the person, why not Hawks’s feathers, deceptively soft but deadly, maneuverable and revealing, and yet, ultimately consist of him breaking his only ability to fly free until he no longer can? What’s more self-sacrificial than breaking off pieces of yourself to save others?

The Good Place has an answer to the problem that accepts that no matter the options, and the questions, someone will lose something. Die maybe. The solution is that if someone must die, why not yourself?

The one comfort is that for all the lack of choices Hawks has been given in this situation - this is the one solution he can come up with on his own.

578 notes

·

View notes

Text

what is something vexing that you’re currently wrestling with?

what am i going to do with my life?

it’s a question i usually find pretty easy to avoid.

i choose classes to take, not based on how they will be helpful to me in the future, but on the basis of weird sporadic urges to learn things, that feeling of i-can’t-go-any-further-as-a-human-being-in-this-world-without-understanding-this-thing, whatever that thing might happen to be: real analysis. kantian ethics. the nitty-gritty philosophical foundations of probability. quantum mechanics. and up though now, everything else has filled in around those strange, urgent desires pretty nicely. i’ll graduate with a math major and a philosophy major almost less because i decided, i want an education in math and philosophy, and more because by chance i will have picked up all the classes needed to graduate. it’s all coming from where my heart is at right-this-very-second, and not at all from thinking about where i want to be three or seven or ten years down the line. so avoiding thinking about the future has been easy.

but while for the last two years i’ve been able to tell myself, i’m still young, i’ve barely started college, i have time—this summer hit, and suddenly those sweet-sounding words felt less satisfying. i might have time, but time passes.

the inside of my head sounds different, now. oh goodness, i’m halfway through my undergraduate education. oh goodness, i’ve taken half the classes i’ll take while i’m at mit. oh goodness, there are classes being offered next semester that won’t be offered again while i’m here, and i may or may not be taking them, i may or may not even know what they are. suddenly, it feels like the stakes are higher. because, sooner-and-sooner, i’m going to have to figure out what i’m /doing/.

granted, of course, i don’t mean “doing” in any grand sense. what i choose now does not determine what i’ll be doing for the rest of my life, or even the next year or six. i try to remind myself of this. people shift jobs and move and change a lot, and these days even the notion of a ‘career’ is dissolving. but still— i’m at least going to have to find something to do with myself to earn a living pretty soon. and while this is exciting, recently it has also been really, really confusing.

there’s thinking about your future work in the sense of figuring out what kind of work you want to be doing—what are you interested in, what kind of skills do you want to be using, what kind of space in your life are you willing to give it, what counts as fulfilling, what puts money in the bank? and this is not straightforward for me. there seem to be innumerable options, and sometimes none seem right, and sometimes all of them do, and i often just feel paralyzed by the sheer number of possible futures.

grad school?…in math? philosophy? logic? something else all together—linguistics? education? heck, architecture theory? theology?…or not grad school at all?—work, at a nonprofit? at a company? in finance or consulting? in please-anything-but-finance-or-consulting?…journalism? teaching? something in the government?…education policy? management? advocacy?… or maybe thinking about job titles isn’t even quite what i’m looking for?—the goal, after all, is not to cognize myself as being something but rather as doing something, and maybe that ‘something’ is a little complicated. maybe my work will be better described as a series of projects or undertakings than as a career, per se. or maybe these urges to learn things will continue and leaning into them will take me in some interesting directions, and i’ll figure it out. point being, i’m not at all clear on what i want to do.

but i’m also coming to find that i’m not sure why or when i can take “i want to” as reason for doing anything, and that includes my future work. this was something that i first came face to face with about in my kantian ethical theory class last fall— having a desire to do something isn’t sufficient reason to will it. on inspection, this is maybe obvious within any moral framework which calls some things impermissible: if you desire to do something impermissible, you still have an obligation not to do it. just wanting in general can’t be enough. and so i have this question: is there a moral system which is binding on me, and if so, what is permissible and impermissible within it? the problem is, i’m encountering so many ethical systems which have different demands and fundamentally different standards, and i’m not sure how to resolve the tensions or where to focus. i have the suspicion (or at least, recognize the possibility) that i have more moral obligations than i have intuition for, and these obligations might then actually influence the way i choose to live my life. but in what way?

for example, helping people in need is part of most ethical systems, but it shows up in different ways, and (glossing over the actual philosophical underpinnings) i’m left with questions. is the duty to help people just general? when are there specific instantiations of it? is there a quantitative aspect?— do i help the most people i can, or eradicate the most suffering i can? is there ever a point where i can stop? do i just do something intentionally in the world? and what do these conditions (“helping people”) really entail?—is this about saving human lives, or about reducing suffering, or helping make people healthy and their souls whole? and what people—those most in need? those easiest to save? those i know and see face to face? what’s the right relation to stand in with the big world, and with the little sliver of the world that i encounter, and are those different at all? what’s even idealism here, much less pragmatism, and which of those lenses am i supposed to look at my choices through?

i came across a paper by kieran setiya (a philosophy professor at mit!) this summer entitled “does moral theory corrupt youth?” (…is it philosophical clickbait?…are there any titles of philosophy papers which aren’t philosophical clickbait?… like i’m laughing, but also it caught me). in it, he writes about how we assume the epistemic standards for moral theory are identical to those of science, why this assumption is incorrect, and how we’re left without quite knowing what the epistemic standards for a moral theory could possibly be. and so, when we get exposed to all these different ways of thinking, presented on par with each other, each with their various pros and cons, in the process we lose sight of all of them. lose faith in morality in general, the way sometimes even devout students fall into deep doubt when taking comparative religion classes. because, it seems, how can you tell which one is right, and what does it mean if you can’t tell that? it’s a quick path to moral skepticism. i read the introduction to this paper and was like, yes! me! this is articulating something about where i’ve been at that i’d been finding hard to put to words. i’m trying desperately to not let these gaping feelings from epistemology numb me to morality in general, but it’s difficult.

(for what it’s worth, near the end of the paper, setiya offers thoughts on the epistemology of morality which might provide direction on judging ethical systems, but it’s not quite concrete enough to help me yet.)

it’s hard to think of the future when you’re in the young-confusing-haze where you don’t quite know what you believe, or where your priorities are, or even what you would want to do next summer, if given the chance to pick. there’s no point to hold firm to and everything just feels like it’s falling through space and breaking apart. and maybe it’s good and appropriate that the inside of my head is not a comfortable, quiet place to reside these days; maybe this is part of what college is for me. i’m thinking and my thoughts are changing and growing more nuanced, at least, if not more well-formed. but i can’t say i always appreciate the absolute overwhelming confusion and chaos.

of course, the future is coming whether i’m ready for it or not.

and there is something deeply exciting about that. i feel funny to know that i’ll know how my future life turns out, in the future. just not now. but—the lack of knowledge about what i’ll be like in the future no longer makes me feel insecure in my present feelings: even though my thoughts and opinions and choices might change in the future, doesn’t mean that i shouldn’t take myself seriously now.

and i’m starting, bit by bit, to feel like i can take myself seriously now. it’s a change; i didn’t used to feel this way. i felt like i was too young, too immature, changing so quickly that i couldn’t trust even the strongest feelings i had. but now—i might be unsettled, but i put enough trust in the conclusions i do come to to take action. i finally gave myself standing to set out long-term plans for myself. for example, while i haven’t decided yet whether i want to pursue a phd, i finally feel like i’m able to make such a decision legitimately, even if i change my mind later. similarly, i recognize that all these moral questions will likely settle differently for me in the future than they will now, but i finally feel like i should still act in accordance with genuine conviction i have now. and it’s freeing, and a little scary, but it feels proper, somehow.

i can feel myself growing.

0 notes