#julia angwin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My favorite piece of the week is this essay about standing up to dictators. It's what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called "Zivilcourage." www.newyorker.com/news/the-wee...

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion | Elon Musk’s Legacy: DOGE’s Construction of a Surveillance State - The New York Times

#authoritarian#authoritarianism#Donald Trump#Elon Musk#Us government#privacy laws#database#surveillance#data protection#DOGE#department of government efficiency#checks and balances#the government wants dossier files on people#JULIA ANGWIN#scary

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

So You Want to Be a Dissident? A Practical Guide To Courage in Trump’s Age of Fear.

— By Julia Angwin and Ami Fields-Meyer | April 12, 2025

A Protester Holding a Sign That Reads “Save Democracy.” Photograph by Jim Goldberg/Magnum

Once Upon A Time—say, several weeks ago—Americans tended to think of dissidents as of another place, perhaps, and another time. They were overseas heroes—names like Alexei Navalny and Jamal Khashoggi, or Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi before them—who spoke up against repressive regimes and paid a steep price for their bravery.

But sometime in the past two months the United States crossed into a new and unfamiliar realm—one in which the consequences of challenging the state seem to increasingly carry real danger. The sitting President, elected on an explicit platform of revenge against his political enemies, entered office by instituting loyalty tests, banning words, purging civil servants, and installing an F.B.I. director who made his name promising to punish his boss’s critics.

Retribution soon followed. For the sin of employing lawyers who have criticized or helped investigate him, President Donald Trump signed orders effectively making it impossible for several law firms to represent clients who do business with the government. For the sin of exercising free speech during campus protests, the Department of Homeland Security began using plainclothes officers to snatch foreign students—legal residents of the United States—off the streets, as the White House threatened major funding cuts to universities where protests had taken place. And for the sin of trying to correct racial and gender disparities, the government is investigating dozens of public and private universities and removing references to Black and Native American combat veterans from public monuments.

Meanwhile, Elon Musk, Trump’s aide-de-camp, has taken a chainsaw to the federal workforce, dispatching his deputies to storm agencies and fire workers who tried to stop his team from illegally downloading government data. Musk, who regularly takes to his social-media platform to harass government workers, has also incited an online mob against a blind nonprofit staffer who mildly criticized his work, and called for prison sentences for journalists at “60 Minutes” who questioned his shuttering of a federal agency.

More people who never aspired to be activists but oppose the new order are finding that they must traverse a labyrinth of novel choices, calculations, and personal risks. Ours is a time of lists—of “deep state” figures to be prosecuted, media outlets to be exiled, and gender identities to be outlawed.

Even the list of professions facing harsh consequences for their day-to-day work is growing. A New York doctor incurred heavy fines from a Texas court for providing reproductive health care. (A New York court refused to enforce the fine.) In Arkansas, a librarian was fired for keeping books covering race and L.G.B.T.Q. issues on the shelves. A member of Congress who organized a workshop to inform immigrants in her district of their rights under the United States Constitution was threatened with federal prosecution.

The climate of retribution has caused many to freeze: Wealthy liberal donors have paused their political giving, concerned about reprisal from the President. One Republican senator dropped his objection to Trump’s Pentagon nominee after reportedly receiving “credible death threats.”

Others who are under pressure from Trump have opted for appeasement: Universities have cut previously unthinkable “deals” with the Administration which threaten academic freedom—such as Columbia’s extraordinary promise to install a monitor to oversee a small university department that studies much of the non-Western world. A growing list of law firms has agreed to devote hundreds of millions of dollars in legal services to the President’s personal priorities, in the hope of avoiding punishment. Some in the opposition Party have even whispered concerns that if they protest too much, Trump will trigger martial law.

But fear has not arrested everyone. Hundreds of thousands of people demonstrated in all fifty states on April 5th, to register their discontent with the new government. For weeks, protesters have let out their fury at dealerships for Musk’s Tesla, contributing to a nearly thirty-per-cent drop in the company’s share price since January. Fired National Park employees scaled Yosemite’s El Capitan and draped an upside-down American flag—a symbol of distress—across one of the monolith’s cliff faces. In the well of the U.S. Senate, Cory Booker, a New Jersey Democrat, delivered a historic twenty-five-hour speech in defiance of Trump’s agenda, electrifying a party whose spirit had begun to ebb.

These early actions may feel limited, even anemic, to Americans who recall images of approximately four million Women’s March participants swarming cities across the nation, at the start of Trump’s first term. But data from the Crowd Counting Consortium, a joint project of the Harvard Kennedy School and the University of Connecticut which counts the size of political crowds at protests, marches, and other civic actions, indicates that there are many more demonstrations unfolding in the United States than there were at this point during the first Trump Administration. In the period between the 2017 Inauguration and the end of that March, the consortium tallied about two thousand protests. During the same period in 2025, it counted more than six thousand.

But the American approach to dissent will likely have to evolve in this era of rising “competitive authoritarianism,” wherein repressive regimes retain the trappings of democracy—such as elections—but use the power of the state to effectively crush resistance. Competitive authoritarians, such as Viktor Orbán, in Hungary, raise the price of opposition by taking control of the “referees”—the courts, the media, and the military. In the United States, many of the referees are beginning to fall in line.

We analyzed the literature of protest and spoke to a range of people, including foreign dissidents and opposition leaders, movement strategists, domestic activists, and scholars of nonviolent movements. We asked them for their advice, in the nascent weeks of the Trump Administration, for those who want to oppose these dramatic changes but harbor considerable fear for their jobs, their freedom, their way of life, or all three. There are some proven lessons, operational and spiritual, to be learned from those who have challenged repressive regimes—a provisional guide for finding courage in Trump’s age of authoritarian fear.

Americans have seen their government weaponize fear before. President Harry Truman directed a purge of the federal workforce amid Cold War paranoia, eventually ensnaring more than seven thousand workers suspected of holding “subversive” views. In the decades that followed, J. Edgar Hoover’s F.B.I. worked diligently to foster a sense of anxiety among Black civil-rights organizers, taking steps such as posting flyers to lure activists to a fake meeting where agents could take down their license-plate numbers. Muslim American and Arab American communities across the U.S. were intensely surveilled after September 11, 2001, by plainclothes detectives who spied on mosques and gathered names and personal details of students attending Muslim campus-group meetings.

One hears echoes of these earlier chapters in today’s political moment. Some demographics, including immigrants and Americans of color, have long been disproportionately subject to tracking, unwarranted surveillance, and suppression. “Institutions that have mostly felt themselves protected from political retaliation now find themselves feeling some of the vulnerability that marginalized communities have long felt,” Faiza Patel, the senior director of the liberty and national-security program at the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice, said.

But the fear now is different in kind. The sweeping scope of Trump’s appetite for institutionalized retaliation has changed the threat landscape for everyone, almost overnight. In a country with a centuries-long culture of free expression, the punishments for those who express even the slightest opposition to the Administration have been a shock to the American system.

There is hope, though. Political-science research reveals that autocratic leaders can be successfully challenged. Erica Chenoweth, a professor at Harvard University, has analyzed more than six hundred mass movements that sought to topple a national government (often in response to its refusal to acknowledge election results) or obtain territorial independence in the past century. Chenoweth found that when at least 3.5 per cent of the population participated in nonviolent opposition, movements were largely successful.

Chenoweth’s data also show that nonviolence is more effective than violence, and that movements do better when they build momentum over time—think a long-lasting general strike or wildcat walkouts, rather than a one-time action. Successful campaigns weaken popular support for an authoritarian leader by encouraging different sectors of society—such as business leaders, religious institutions, unions, or the military—to withdraw their support from a corrupt or unjust regime. One by one, the sectors defect, and, eventually, the leader may weaken and their government may fall.

Take South Africa, for instance, where, in the late nineteen-eighties and early nineties, white business owners who were feeling the pain of domestic and global economic boycotts turned their ire toward the ruling National Party government, pressuring leaders to come to the table with Mandela and end apartheid.

Or Serbia, where, during the demonstrations against Slobodan Milošević at the turn of the twenty-first century, a student movement managed to weaken the willingness of state security forces to use violence against them. Activists brought flowers and cakes to the police and military officers while they were standing guard. At the peak of the protests, when hundreds of thousands of people assembled alongside a general strike in Belgrade, Milošević ordered the police to disperse the protesters, but the police refused.

“All power-holders, even the most ruthless and corrupt, rely on the consent and coöperation of ordinary people,” Maria J. Stephan, who co-authored a book with Chenoweth titled “Why Civil Resistance Works,” said.

The key to challenging authoritarian regimes, Stephan said, is for citizens to decline to participate in immoral and illegal acts. Stephan, who co-leads the Horizons Project, a nonprofit that supports nonviolent movements against authoritarianism, has a phrase for this mind-set: “I think of it as collective stubbornness,” she said.

Danny Timpona stood at the front of a crowded room as a slide show of photos flashed on the projector screen behind him: A white Department of Homeland Security vehicle. A Black Chevy S.U.V. with tinted windows. Then close shots of uniform patches stitched with the insignias of various immigration-enforcement agencies—ice, Customs and Border Patrol, and Homeland Security Investigations.

It was a brisk night in early March. The audience of seventy-five people—packed closely into white folding chairs at a community center just outside Boston—had come to learn how to spot undercover immigration agents. Timpona, the organizing director for the community-organizing group Neighbor to Neighbor Massachusetts, initiated a pop quiz. As a new batch of images appeared on the screen, people shouted from their seats: “That one’s ice!” “That’s a police car!”

A few weeks earlier, Tom Homan, Trump’s cartoonishly tough-talking “border czar,” had pledged in a widely covered speech that he would soon bring “hell” to Boston in the form of immigration raids. Within days of Homan’s remarks, a coalition of Massachusetts immigrant-rights groups had begun training people across the state to approach suspicious vehicles and document their conversations with the agents inside before calling a hotline run by the coalition Luce to share as much information as possible.

Long a fixture of civil-rights and racial-justice campaigns in the United States, communal trainings for nonviolent action aren’t just about tactics; they also carry something of a spiritual message: Yes, you’ve signed up to take on a higher level of risk for the greater good, these group sessions convey. But you’re not doing it by yourself.

Many dissidents we spoke to said that, amid prolonged and cascading political crises, establishing a political home for yourself is a necessary ingredient for nurturing non-coöperation. Think of this as the equivalent of participation in a faith community that meets to worship—a regular practice to guard against loneliness and despair, and check in with others going through a similar experience.

Felix Maradiaga, a Nicaraguan opposition leader, was jailed in 2021, after announcing that he would challenge the dictator Daniel Ortega for the Presidency. Maradiaga had risen to prominence as an outspoken critic of Ortega’s corruption, including his channelling of public funds to his family and close allies through private business ventures and government contracts. Maradiaga, who was released from prison in 2023, says that dissent was most personally taxing when he felt most politically isolated. “I spoke openly against crony capitalism,” he said. “To my surprise, there were very, very few who spoke up.”

Maradiaga credits his ability to advocate against Ortega’s dictatorship in the years before his imprisonment to a community of support that he cultivated—both locally, through family and friends, and globally, through the World Liberty Congress, an alliance of antiauthoritarian activists from regimes, including Iran, Russia, Rwanda, and China. Now living in exile in the United States, Maradiaga serves as the director of the W.L.C.’s academy, which helps train activists fighting authoritarian governments around the world. Among the slate of protest tactics that he teaches, he says, none may be as important as finding your people: “Having a community is a powerful tool of resilience.”

A few weeks after the Boston-area ice-watch training, community preparation paid off when the network received a tip: men in suspicious vehicles had been spotted in front of a construction site where day laborers were working. Casey (whose name has been changed here), a local elementary-school teacher who had attended the community-center session, received a message with a request for volunteers to the location. By the time Casey arrived, others from the network had already engaged with the agents about their presence in the area and had filmed the interaction on their phones. The agents eventually drove away, but Casey stayed at the site for about two hours, before noticing some of the workers leaving through the back. Casey and a few other volunteers approached them with know-your-rights materials and offered them a ride home. The workers accepted both.

Homan has kept his promise, overseeing the immigration arrests of three hundred and seventy people in Massachusetts over a multiday operation in late March. But no one at the construction site was taken into custody or detained that day.

Taking part in non-coöperation or defiance doesn’t have to mean becoming a martyr or abandoning all personal defenses, particularly in the United States, where we still have plenty of legal and cultural support for freedom of expression. Even so, this moment calls for discretion.

“There’s never going to be zero risk,” Ramzi Kassem, a professor of law at the City University of New York and a co-leader of the nonprofit legal clinic clear, said. “You just have to decide how much risk you are willing to carry to continue to do the work you’re doing.” Worrying about amorphous dangers can be paralyzing. Instead, if you’re considering non-coöperation work, write up a plan for the worst-case scenario—what you’ll do if you get fired or audited, or find yourself in legal trouble. Reach out to a lawyer and an accountant, or others who could help you navigate complicated decisions.

Now is the time to clean up your life—your digital life and even, perhaps, your personal life. Dissidents describe a pattern: autocrats and their cronies use even the most minor personal scandal to undermine the credibility of activists and weaken their movements. “You have to be a nun or a saint,” a prominent Venezuelan political activist, who asked not to be named, told us. “If someone wants to find dirt on you, they will find it, so give them the least dirt possible.”

That includes deleting old social-media posts and using only trusted encrypted-messaging apps. Sadly, cleaning up might mean swearing off dating apps—or at least going the extra mile to verify that potential suitors are who they say they are. The right-wing activist James O’Keefe has been advertising on Facebook and X for people who will use matchmaking platforms to meet with targets and secretly record them. In January, he nabbed a Biden White House staffer, and last month his former organization, Project Veritas, used a similar technique against a U.S. Education Department worker.

Another key strategy, ironically, is compliance—as in compliance with as many laws as possible. Tax laws. Traffic laws. Sandor Lederer, who runs K-Monitor, a corruption-watchdog group in Hungary, recalled being investigated as part of an inquiry into multiple nonprofits by the government of Orbán, a close Trump ally. Lederer said that the organizations were targeted as part of the regime’s strategy to “never talk about the substance of the issues” that his anti-corruption group has raised but, instead, to find something to disable and distract dissidents. “It’s more about keeping us busy rather than shutting us down,” he added.

Lederer said that he resents having to be paranoid, but that now he does everything by the book. If a Ph.D. student wants to interview him for a project, he requires an e-mail from a university address, a letter from the professor, and other due diligence, to prove the request isn’t some kind of entrapment. “This is a bad way to live,’’ he said. “You always have to think who is going to trick you or fool you.”

That leads to the next strategy: compartmentalization—don’t share information with anyone you don’t really trust. Technically, compartmentalization can mean having separate work and personal devices such as phones and computers, so that if one is searched, the other remains untouched. But it’s a mistake to think technology is the only way that information leaks.

Those who defend women seeking abortions in U.S. states where it is illegal warn that when women are betrayed, it’s usually not through digital surveillance but, actually, through someone they know—a friend, relative, nurse, or current or former partner. This is where code words can be helpful, allowing you to talk about sensitive topics where you might be overheard.

But there is a fine line between discretion and self-censorship. The key is to pick your battles—fight about the speech you want to fight about, not the speech that isn’t important to you. “Be cautious, but don’t silence yourself,” David Kaye, a human-rights lawyer, said.

One night in February, shivering residents of Washington, D.C., gathered in front of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Performers in drag twirled and twerked in acrobatic formations as the swaying crowd shouted the lyrics of Chappell Roan’s dance ballad “Pink Pony Club.”

The scene was equal parts dance party and street protest. One day earlier, Trump had moved to seize control of the Kennedy Center’s board and programming, citing drag shows held there the previous year as his rationale. Trump had vowed on social media, “NO MORE DRAG SHOWS.”

It’s tempting, amid a mounting assault on the constitutional order, to dismiss revelry as a flimsy—even inappropriate—tactic to meet the political moment. In the combat theatre of American democracy, what meaningful advances could come of a few hundred people gyrating and raising hand-lettered signs on a street corner?

According to Keya Chatterjee, one of the organizers of the Kennedy Center event, there are some critical advantages to gatherings like this. Chatterjee believes that through the rising authoritarian tides, places where people can enjoy one another’s company are a beachhead where organizing can begin. “They want us to be so afraid,” she said. “And the only way to counter fear is with joy.”

In January, Chatterjee launched a new organization, FreeDC, with a goal of achieving what the District has never been able to obtain in decades of fighting: self-governance. D.C. has been seeking statehood for generations, but its autonomy has increasing relevance given Trump’s norm-defying efforts to consolidate power over the nation’s courts, Congress, and military and intelligence services. It’s much easier for federal authorities to deploy the military in a federal district than it would be in a state. That means that any civil resistance could be crippled in the nation’s capital. “When you have an authoritarian, it matters very much if you can organize in the capital,” Chatterjee said.

Chatterjee is trying to unite her capital neighbors through drag dance parties, happy hours, bracelet-making bashes, and drum circles. In each of the city’s eight wards, FreeDC organizing committees hold regular events with a stated mission to “prioritize joy.” Each committee aims to enlist as members 3.5 per cent of the ward’s population, or about thirty-one hundred people. Chatterjee knows that figure, generated by Chenoweth’s research, is not a guarantee of success, but it’s a tangible and achievable target.

It’s painstaking work. For the first few weeks, the organization was growing by four hundred people per week. Jeremy Heimans, the co-founder of GetUp!, Australia’s version of MoveOn.org, and a global organizing incubator called Purpose, describes the current moment as the least favorable environment for motivating large groups of progressives that he’s seen in twenty years. “This is probably the low-water mark in terms of both engagement and efficacy of mass movements,” he said.

Heimans points to an increasingly hostile digital landscape as one barrier to effective grassroots campaigns. At the dawn of the digital era, in the two-thousands, e-mail transformed the field of political organizing, enabling groups like MoveOn.org to mobilize huge campaigns against the Iraq War, and allowing upstart candidates like Howard Dean and Barack Obama to raise money directly from people instead of relying on Party infrastructure. But now everyone’s e-mail inboxes are overflowing. The tech oligarchs who control the social-media platforms are less willing to support progressive activism. Globally, autocrats have more tools to surveil and disrupt digital campaigns. And regular people are burned out on actions that have failed to remedy fundamental problems in society.

It’s not clear what comes next. Heimans hopes that new tactics will be developed, such as, perhaps, a new online platform that would help organizing, or the strengthening of a progressive-media ecosystem that will engage new participants. “Something will emerge that kind of revitalizes the space.”

There’s an oft-told story about Andrei Sakharov, the celebrated twentieth-century Soviet activist. Sakharov made his name working as a physicist on the development of the U.S.S.R.’s hydrogen bomb, at the height of the Cold War, but shot to global prominence after Leonid Brezhnev’s regime punished him for speaking publicly about the dangers of those weapons, and also about Soviet repression.

When an American friend was visiting Sakharov and his wife, the activist Yelena Bonner, in Moscow, the friend referred to Sakharov as a dissident. Bonner corrected him: “My husband is a physicist, not a dissident.”

This is a fundamental tension of building a principled dissident culture—it risks wrapping people up in a kind of negative identity, a cloak of what they are not. The Soviet dissidents understood their work as a struggle to uphold the laws and rights that were enshrined in the Soviet constitution, not as a fight against a regime.

“They were fastidious about everything they did being consistent with Soviet law,” Benjamin Nathans, a history professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of a book on Soviet dissidents, said. “I call it radical civil obedience.”

An affirmative vision of what the world should be is the inspiration for many of those who, in these tempestuous early months of Trump 2.0, have taken meaningful risks—acts of American dissent.

Consider Mariann Budde, the Episcopal bishop who used her pulpit before Trump on Inauguration Day to ask the President’s “mercy” for two vulnerable groups for whom he has reserved his most visceral disdain. For her sins, a congressional ally of the President called for the pastor to be “added to the deportation list.”

“You often need a martyr or someone very committed to act first,” Margaret Levi, a professor emerita of political science at Stanford University, said. As the crowd of dissenters grows, she said, it generates a “belief cascade,” which sweeps greater numbers into a greater sense of comfort and security when participating in acts of defiance.

The price for those who stand directly in the way of Trump’s plans may indeed grow steeper in the coming months and years. But these early acts, as much as they are oppositional, also point to a coherent vision of a just and compassionate society.

Even in their darkest hours, in the late nineteen-seventies and early eighties, when the K.G.B. sent many Soviet dissident leaders to forced-labor camps and psychiatric institutions, the activists continued writing their books, making their art, and publishing their newsletters. And, when they gathered, they raised their glasses in the traditional toast: “To the success of our hopeless cause.”

In 1989, the Berlin Wall came down. ♦

— Julia Angwin is a Pulitzer Prize-Winning Investigative Journalist, New York Times Contributing Opinion Writer and Founder of the Nonprofit Journalism Studio Proof News.

— Ami Fields-Meyer is a Writer and Senior Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School's Ash Center For Democratic Governance and Innovation. He Served as Senior Policy Adviser to Former Vice-President Kamala Harris.

#The Weekend Essay#The New Yorker#Julia Angwin | Ami Fields-Meyer#Dissidents#Donald Trump#Free Speech 🎤#Civil Protests#Protests

0 notes

Text

"It feels like another sign that A.I. is not even close to living up to its hype. In my eyes, it’s looking less like an all-powerful being and more like a bad intern whose work is so unreliable that it’s often easier to do the task yourself. That realization has real implications for the way we, our employers and our government should deal with Silicon Valley’s latest dazzling new, new thing. Acknowledging A.I.’s flaws could help us invest our resources more efficiently and also allow us to turn our attention toward more realistic solutions.

...

I don’t think we’re in cryptocurrency territory, where the hype turned out to be a cover story for a number of illegal schemes that landed a few big names in prison. But it’s also pretty clear that we’re a long way from Mr. Altman’s promise that A.I. will become “the most powerful technology humanity has yet invented.”"

--Julia Angwin for the New York Times, May 13, 2024

#thank you Julia Angwin for continuing to be the voice of reason amidst the techbro cacophony#tech#machine learning

0 notes

Text

The biggest question raised by a future populated by unexceptional A.I., however, is existential. Should we as a society be investing tens of billions of dollars, our precious electricity that could be used toward moving away from fossil fuels, and a generation of the brightest math and science minds on incremental improvements in mediocre email writing? We can’t abandon work on improving A.I. The technology, however middling, is here to stay, and people are going to use it. But we should reckon with the possibility that we are investing in an ideal future that may not materialize.

–Julia Angwin, "Will A.I. Ever Live Up to Its Hype?" The New York Times, May 15, 2024

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

This day in history

I'm on tour with my new, nationally bestselling novel The Bezzle! Catch me on SUNDAY (Mar 24) with LAURA POITRAS in NYC, then Anaheim, and beyond!

#20yrsago I just finished another novel! https://memex.craphound.com/2004/03/23/i-just-finished-another-novel/

#15yrsago New Zealand’s stupid copyright law dies https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2009/03/3-strikes-strikes-out-in-nz-as-government-yanks-law/

#10yrsago NSA hacked Huawei, totally penetrated its networks and systems, stole its sourcecode https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/23/world/asia/nsa-breached-chinese-servers-seen-as-spy-peril.html

#10yrsago Business Software Alliance accused of pirating the photo they used in their snitch-on-pirates ad https://torrentfreak.com/bsa-pirates-busted-140322/

#5yrsago Video from the Radicalized launch with Julia Angwin at The Strand https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FbdgdH8ksaM

#5yrsago More than 100,000 Europeans march against #Article13 https://netzpolitik.org/2019/weit-mehr-als-100-000-menschen-demonstrieren-in-vielen-deutschen-staedten-fuer-ein-offenes-netz/

#5yrsago Procedurally generated infinite CVS receipt https://codepen.io/garrettbear/pen/JzMmqg

#5yrsago British schoolchildren receive chemical burns from “toxic ash” on Ash Wednesday https://metro.co.uk/2019/03/08/children-end-hospital-burns-heads-toxic-ash-wednesday-ash-8868433/

#5yrsago DCCC introduces No-More-AOCs rule https://theintercept.com/2019/03/22/house-democratic-leadership-warns-it-will-cut-off-any-firms-who-challenge-incumbents/

#1yrago The "small nonprofit school" saved in the SVB bailout charges more than Harvard https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/23/small-nonprofit-school/#north-country-school

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

El DOGE de Elon Musk está construyendo un Estado de vigilancia, como nunca se ha visto en Estados Unidos... Trump podría disponer pronto de las herramientas necesarias para satisfacer sus numerosas quejas localizando rápidamente información comprometedora sobre sus oponentes políticos o sobre cualquier persona que simplemente le moleste... trabajadores federales también han sido informados de que el DOGE está utilizando IA para cribar sus comunicaciones con el fin de identificar a quienes albergan sentimientos anti-Musk o anti-Trump (y presumiblemente castigarlos o despedirlos). Esto supone un giro asombrosamente rápido de nuestra larga historia de aislar y resguardar los datos gubernamentales para evitar su uso indebido... Musk y Trump han derribado las barreras que pretendían impedirles crear expedientes sobre cada residente en Estados Unidos. Ahora, parecen estar creando un rasgo definitorio de muchos regímenes autoritarios: archivos exhaustivos sobre todo el mundo para poder castigar a aquellos que protestan... En los últimos 100 días, los equipos del DOGE han obtenido datos personales sobre residentes estadounidenses de decenas de bases de datos federales y, al parecer, los están fusionando todos en una base de datos maestra en el Departamento de Seguridad Nacional.... “La infraestructura para el totalitarismo llave en mano está ahí para una administración dispuesta a infringir la ley” (Julia Angwin , The New York Times)

#capitalismodevigilancia#controlsocial#controlsocialinquisicion#controlsocialinteligenciaartificial#elonmusk#democraciadecadencia#trumppolitica#trumppoliticaefectos#democraciaoligarquicaeeuu

0 notes

Text

“'I find my feelings about A.I. are actually pretty similar to my feelings about blockchains: They do a poor job of much of what people try to do with them, they can’t do the things their creators claim they one day might, and many of the things they are well suited to do may not be altogether that beneficial,' wrote Molly White, a cryptocurrency researcher and critic, in her newsletter last month... "Should we as a society be investing tens of billions of dollars, our precious electricity that could be used toward moving away from fossil fuels, and a generation of the brightest math and science minds on incremental improvements in mediocre email writing?" --Julia Angwin, NYT

0 notes

Text

AI Snake Oil is now available to preorder

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/ai-snake-oil-is-now-available-to-preorder/

AI Snake Oil is now available to preorder

We are happy to share that our book AI Snake Oil is now available to preorder across online booksellers. The publication date is September 24, 2024. If you have enjoyed reading our newsletter and would like to support our work, please preorder the book via Amazon, Bookshop, or your favorite bookseller.

We get two recurring questions about the book:

In an area as fast moving as AI, how long can a book stay relevant?

How similar is the book to the newsletter?

The answer to both questions is the same. We know that book publishing moves at a slower timescale than AI. So the book is about the foundational knowledge needed to separate real advances from hype, rather than commentary on breaking developments. In writing every chapter, and every paragraph, we asked ourselves: will this be relevant in five years? This also means that there’s very little overlap between the newsletter and the book.

AI Snake Oil book cover

In the book, we explain the crucial differences between types of AI, why people, companies, and governments are falling for AI snake oil, why AI can’t fix social media, and why we should be far more worried about what people will do with AI than about anything AI will do on its own. While generative AI is what drives press, predictive AI used in criminal justice, finance, healthcare, and other domains remains far more consequential in people’s lives. We discuss in depth how predictive AI can go wrong. We also warn of the dangers of a world where AI continues to be controlled by largely unaccountable big tech companies.

The book is not just an explainer. Every chapter includes original scholarship. We plan to release exercises and discussion questions for classroom use; courses on the relationship between tech and society might benefit from the book.

This is the first time we’ve written a mass-market book. We learned that preordering a book, as opposed to ordering after release, can make a big difference to its success. Preorder sales are used by retailers to decide which books to stock and promote after release. They help books get recognized on best-seller lists. They allow our publishers to anticipate how many copies need to be printed and how the book should be distributed. They are also used by online booksellers to make algorithmic recommendations. In short, pre-ordering early is the best way to support our work. You can preorder the book from your local retailers via Bookshop.org or on Amazon.

We couldn’t have written AI Snake Oil without the support of Hallie Stebbins, our editor at Princeton University Press. The book was peer reviewed by three experts: Melanie Mitchell and two anonymous reviewers. We also received informal peer reviews from Matt Salganik, Molly Crockett, and Chris Bail. All of this feedback helped us improve the book immensely, and we are grateful for the reviewers’ time and thoughtful attention. We are also grateful to Alondra Nelson, Julia Angwin, Kate Crawford, and Melanie Mitchell, who took the time to read the book and write blurbs.

Thank you to the over 25,000 of you who subscribe to this newsletter. We look forward to continuing to write the newsletter even after the book is published. Analyzing topical and pressing questions about AI using the foundational understanding we develop in the book has been one of the most rewarding parts of our work. We hope the book will be useful to you. Thank you for supporting us.

Preorder links

US: Amazon, Bookshop, Barnes and Noble. UK: Waterstones. Canada: Indigo. Germany: Kulturkaufhaus. The book is available to preorder internationally on Amazon.

#000#2024#ai#Amazon#artificial#Artificial Intelligence#attention#book#Books#Canada#Companies#courses#Developments#domains#finance#generative#generative ai#Germany#healthcare#how#how to#intelligence#it#justice#links#lists#mass#media#newsletter#oil

0 notes

Text

AI Black Box Under Siege: Researchers Revolt for AI Transparency

AI Transparency Battle Royale! Over 100 top AI researchers are throwing down the gauntlet, demanding AI transparency from tech giants like OpenAI and Meta. In a scorching open letter, they accuse these companies of hindering independent research with their restrictive rules. The argument? These supposedly "safe" protocols are actually stifling the very investigations needed to ensure these powerful AI systems are used responsibly! This isn't just academic whining. Researchers are worried that strict protocols meant to catch bad actors are instead silencing vital research. Independent investigators are terrified of account bans or even lawsuits if they dare to stress-test AI models without a company's blessing. It's like trying to warn people about a dangerous product, only to get sued by the manufacturer for hurting their reputation. “Generative AI companies should avoid repeating the mistakes of social media platforms, many of which have effectively banned types of research aimed at holding them accountable,”Authors of the letterTweet Who's Leading the Charge? A League of Extraordinary AI Watchdogs This isn't just a bunch of disgruntled researchers. This open letter is backed by a who's-who of AI experts, journalists, policymakers, and even a former European Parliament member. Let's break down the heavy hitters: - AI All-Stars: Think top minds from places like Stanford University, with names like Percy Liang gracing the letter. These are the folks who build the algorithms, not just theorize about them. - Investigative Journalists: Pulitzer Prize winners like Julia Angwin, famous for exposing tech's hidden biases, are signing on. They're not afraid to dig deep and uncover the flaws these shiny new AI tools might be hiding. - Policy Powerhouses: People like Renée DiResta from the Stanford Internet Observatory, who study the impact of AI on society, are demanding a seat at the table. They want to make sure these tools aren't used to manipulate elections or deepen inequalities. - Global Perspective: Marietje Schaake, a former member of European Parliament, adds international clout. This isn't just a US issue; the potential misuse of AI affects everyone and demands global solutions. Break Free Of Big Tech Control This rag-tag team of code-slingers, truth-seekers, and policy wonks might not wear capes, but they're fighting to ensure that AI serves the public interest, not just corporate profits. Tech Giants: Turning into the Evil Empires They Swore to Destroy? The letter throws some serious shade, accusing AI companies of emulating the secrecy that plagued early social media platforms. The examples are downright chilling: from OpenAI crying "hacker!" over copyright checks to Midjourney threatening artists with legal action The Midjourney saga is a prime example of how paranoid AI companies are getting. Artist Reid Southen dared to test if the image generator could be used to rip off copyrighted characters, and what did he get? Banned! Midjourney even went full-on drama queen in their terms of service, threatening lawsuits over copyright claims. Talk about an overreaction! This is just one example in a growing pattern – tech companies are clutching their precious algorithms, terrified of anyone peeking behind the curtain to find out what their AI creations are really up to. “If You knowingly infringe someone else’s intellectual property, and that costs us money, we’re going to come find You and collect that money from You,” Read the terms here “We might also do other stuff, like try to get a court to make You pay our legal fees. Don’t do it.”MidJourneyTweet The Battle for AI Transparency: Researchers vs. Corporate Control This is more than just disgruntled academics versus big tech. It's a clash of ideologies with the future of AI at stake. On one side, researchers are demanding open access and safeguards to protect us from biased or harmful AI. On the other, tech giants are clinging to control, treating potential misuse like it's some far-fetched sci-fi dystopia instead of a very real risk that needs serious scrutiny. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

The End of Trust

New Post has been published on https://www.aneddoticamagazine.com/the-end-of-trust/

The End of Trust

EFF and McSweeney’s have teamed up to bring you The End of Trust (McSweeney’s 54). The first all-nonfiction McSweeney’s issue is a collection of essays and interviews focusing on issues related to technology, privacy, and surveillance.

The collection features writing by EFF’s team, including Executive Director Cindy Cohn, Education and Design Lead Soraya Okuda, Senior Investigative Researcher Dave Maass, Special Advisor Cory Doctorow, and board member Bruce Schneier.

Anthropologist Gabriella Coleman contemplates anonymity; Edward Snowden explains blockchain; journalist Julia Angwin and Pioneer Award-winning artist Trevor Paglen discuss the intersections of their work; Pioneer Award winner Malkia Cyril discusses the historical surveillance of black bodies; and Ken Montenegro and Hamid Khan of Stop LAPD Spying debate author and intelligence contractor Myke Cole on the question of whether there’s a way law enforcement can use surveillance responsibly.

The End of Trust is available to download and read right now under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND license.

#bruce schneier#Cindy Cohn#collection of essays and interviews#Cory Doctorow#Dave Maass#Edward Snowden#EFF#Gabriella Coleman#privacy#Soraya Okuda#surveillance#technology#The End of Trust

1 note

·

View note

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: The OpenAI Coup Is Great for Microsoft. What Does It Mean for Us? by Julia Angwin

By Julia Angwin The OpenAI fracas most likely cements control of one of the most powerful and promising technologies on the planet under one of this country’s tech titans. Published: November 21, 2023 at 04:46PM from NYT Opinion https://ift.tt/K0jiUVM via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

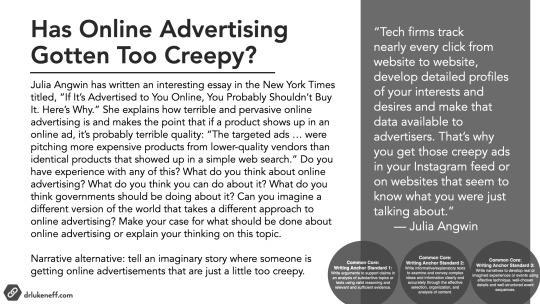

Has Online Advertising Gotten Too Creepy?

“Tech firms track nearly every click from website to website, develop detailed profiles of your interests and desires and make that data available to advertisers. That’s why you get those creepy ads in your Instagram feed or on websites that seem to know what you were just talking about.”

— Julia Angwin

Julia Angwin has written an interesting essay in the New York Times titled, “If It’s Advertised to You Online, You Probably Shouldn’t Buy It. Here’s Why.” She explains how terrible and pervasive online advertising is and makes the point that if a product shows up in an online ad, it’s probably terrible quality: “The targeted ads … were pitching more expensive products from lower-quality vendors than identical products that showed up in a simple web search.” Do you have experience with any of this? What do you think about online advertising? What do you think you can do about it? What do you think governments should be doing about it? Can you imagine a different version of the world that takes a different approach to online advertising? Make your case for what should be done about online advertising or explain your thinking on this topic.

Narrative alternative: tell an imaginary story where someone is getting online advertisements that are just a little too creepy.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The reality is that A.I. models can often prepare a decent first draft. But I find that when I use A.I., I have to spend almost as much time correcting and revising its output as it would have taken me to do the work myself. And consider for a moment the possibility that perhaps A.I. isn’t going to get that much better anytime soon. After all, the A.I. companies are running out of new data on which to train their models, and they are running out of energy to fuel their power-hungry A.I. machines. Meanwhile, authors and news organizations (including The New York Times) are contesting the legality of having their data ingested into the A.I. models without their consent, which could end up forcing quality data to be withdrawn from the models. Given these constraints, it seems just as likely to me that generative A.I. could end up like the Roomba, the mediocre vacuum robot that does a passable job when you are home alone but not if you are expecting guests. Companies that can get by with Roomba-quality work will, of course, still try to replace workers. But in workplaces where quality matters — and where workforces such as screenwriters and nurses are unionized — A.I. may not make significant inroads.

–Julia Angwin, "Will A.I. Ever Live Up to Its Hype?" The New York Times, May 15, 2024

0 notes

Text

Everything advertised on social media is overpriced junk

In “Behavioral Advertising and Consumer Welfare: An Empirical Investigation,” a trio of business researchers from Carnegie Mellon and Pamplin College investigate the difference between the goods purchased through highly targeted online ads and just plain web-searches, and conclude social media ads push overpriced junk:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4398428

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this thread to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/08/late-stage-sea-monkeys/#jeremys-razors

Specifically, stuff that’s pushed to you via targeted ads costs an average of 10 percent more, and it significantly more likely to come from a vendor with a poor rating from the Better Business Bureau. This may seem trivial and obvious, but it’s got profound implications for media, commercial surveillance, and the future of the internet.

Writing in the New York Times, Julia Angwin — a legendary, muckraking data journalist — breaks down those implications. Angwin builds a case study around Jeremy’s Razors, a business that advertises itself as a “woke-free” shaving solution for manly men:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/06/opinion/online-advertising-privacy-data-surveillance-consumer-quality.html

Jeremy’s Razors spends a fucking fortune on ads. According to Facebook’s Ad Library, the company spent $800,000 on FB ads in March, targeting fathers of school-age kids who like Hershey’s, ultimate fighting, hunting or Johnny Cash:

https://pluralistic.net/jeremys-targeting

Anti-woke razors are an objectively, hilariously stupid idea, but that’s not the point here. The point is that Jeremy’s has to spend $800K/month to reach its customers, which means that it either has to accept $800K less in profits, or make it up by charging more and/or skimping on quality.

Targeted advertising is incredibly expensive, and incredibly lucrative — for the ad-tech platforms that sit between creative workers and media companies on one side, and audiences on the other. In order to target ads, ad-tech companies have to collect deep, nonconsensual dossiers on every internet user, full of personal, sensitive and potentially compromising information.

The switch to targeted ads was part of the enshittification cycle, whereby companies like Facebook and Google lured in end-users by offering high-quality services — Facebook showed you the things the people you asked to hear from posted, and Google returned the best search results it could find.

Eventually, those users became locked in. Once all our friends were on Facebook, we held each other hostage, each unable to leave because the others were there. Google used its access to the capital markets to snuff out any rival search companies, spending tens of billions every year to be the default on Apple devices, for example.

Once we were locked in, the tech giants made life worse for us in order to make life better for media companies and advertisers. Facebook violated its promise to be the privacy-centric alternative to Myspace, where our data would never be harvested; it switched on mass surveillance and created cheap, accurate ad-targeting:

https://lawcat.berkeley.edu/record/1128876?ln=en

Google fulfilled the prophecy in its founding technical document, the Pagerank paper: “advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.” They, too, offered cheap, highly targeted ads:

http://infolab.stanford.edu/~backrub/google.html

Facebook and Google weren’t just kind to advertisers — they also gave media companies and creative workers a great deal, funneling vast quantities of traffic to both. Facebook did this by cramming media content into the feeds of people who hadn’t asked to see it, displacing the friends’ posts they had asked to see. Google did it by upranking media posts in search results.

Then we came to the final stage of the enshittification cycle: having hooked both end-users and business customers, Facebook and Google withdrew the surpluses from both groups and handed them to their own shareholders. Advertising costs went up. The share of ad income paid to media companies went down. Users got more ads in their feeds and search results.

Facebook and Google illegally colluded to rig the ad-market with a program called Jedi Blue that let the companies steal from both advertisers and media companies:

https://techcrunch.com/2022/03/11/google-meta-jedi-blue-eu-uk-antitrust-probes/

Apple blocked Facebook’s surveillance on its mobile devices, but increased its own surveillance of Iphone and Ipad users in order to target ads to them, even when those users explicitly opted out of spying:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/14/luxury-surveillance/#liar-liar

Today, we live in the enshittification end-times, red of tooth and claw, where media companies’ revenues are dwindling and advertisers’ costs are soaring, and the tech giants are raking in hundreds of billions, firing hundreds of thousands of workers, and pissing away tens of billions on stock buybacks:

https://doctorow.medium.com/mass-tech-worker-layoffs-and-the-soft-landing-1ddbb442e608

As Angwin points out, in the era before behavioral advertising, Jeremy’s might have bought an ad in Deer & Deer Hunting or another magazine that caters to he-man types who don’t want woke razors; the same is true for all products and publications. Before mass, non-consensual surveillance, ads were based on content and context, not on the reader’s prior behavior.

There’s no reason that ads today couldn’t return to that regime. Contextual ads operate without surveillance, using the same “real-time bidding” mechanism to place ads based on the content of the article and some basic parameters about the user (rough location based on IP address, time of day, device type):

https://pluralistic.net/2020/08/05/behavioral-v-contextual/#contextual-ads

Context ads perform about as well as behavioral ads — but they have a radically different power-structure. No media company will ever know as much about a given user as an ad-tech giant practicing dragnet surveillance and buying purchase, location and finance data from data-brokers. But no ad-tech giant knows as much about the context and content of an article as the media company that published it.

Context ads are, by definition, centered on the media company or creative worker whose work they appear alongside of. They are much harder for tech giants to enshittify, because enshittification requires lock-in and it’s hard to lock in a publication who knows better than anyone what they’re publishing and what it means.

We should ban surveillance advertising. Period. Companies should not be allowed to collect our data without our meaningful opt-in consent, and if that was the standard, there would be no data-collection:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/03/22/myob/#adtech-considered-harmful

Remember when Apple created an opt out button for tracking, more than 94 percent of users clicked it (the people who clicked “yes” to “can Facebook spy on you?” were either Facebook employees, or confused):

https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/02/facebook-says-apple-ios-privacy-change-will-cost-10-billion-this-year.html

Ad-targeting enables a host of evils, like paid political disinformation. It also leads to more expensive, lower-quality goods. “A Raw Deal For Consumers,” Sumit Sharma’s new Consumer Reports paper, catalogs the many other costs imposed on Americans due to the lack of tech regulation:

https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/A-Raw-Deal-for-US-Consumers_March-2023.pdf

Sharma describes the benefits that Europeans will shortly enjoy thanks to the EU’s Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act, from lower prices to more privacy to more choice, from cloud gaming on mobile devices to competing app stores.

However, both the EU and the US — as well as Canada and Australia — have focused their news industry legislating on misguided “link taxes,” where tech giants are required to pay license fees to link to and excerpt the news. This is an approach grounded in the mistaken idea that tech giants are stealing media companies’ content — when really, tech giants are stealing their money:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/04/18/news-isnt-secret/#bid-shading

Creating a new pseudocopyright to control who can discuss the news is a terrible idea, one that will make the media companies beholden to the tech giants at a time when we desperately need deep, critical reporting on the tech sector. In Canada, where Bill C-18 is the latest link tax proposal in the running to become law, we’re already seeing that conflict of interest come into play.

As Jesse Brown and Paula Simons — a veteran reporter turned senator — discuss on the latest Canadaland podcast, the Toronto Star’s sharp and well-reported critical series on the tech giants died a swift and unexplained death immediately after the Star began receiving license fees for tech users’ links and excerpts from its reporting:

https://www.canadaland.com/paula-simons-bill-c-18/

Meanwhile, in Australia, the proposed “news bargaining code” stampeded the tech giants into agreeing to enter into “voluntary” negotiations with the media companies, allowing Rupert Murdoch’s Newscorp to claim the lion’s share of the money, and then conduct layoffs across its newsrooms.

While in France, the link tax depends on publishers integrating with Google Showcase, a product that makes Google more money from news content and makes news publishers more dependent on Google:

https://www.politico.eu/article/french-competition-authority-greenlights-google-pledges-over-paying-news-publishers/

A link tax only pays for so long as the tech giants remain dominant and continue to extract the massive profits that make them capable of paying the tax. But legislative action to fix the ad-tech markets, like Senator Mike Lee’s ad-tech breakup bill (cosponsored by both Ted Cruz and Elizabeth Warren!) would shift power to publishers, and with it, money:

https://www.lee.senate.gov/2023/3/the-america-act

With ad-tech intermediaries scooping up 50% or more of every advertising dollar, there is plenty of potential to save news without the need for a link tax. If unrigging the ad-tech market drops the platforms’ share of advertising dollars to a more reasonable 10%, then the advertisers and publishers could split the remainder, with advertisers spending 20% less and publishers netting 20% more.

Passing a federal privacy law would end surveillance advertising at the stroke of a pen, shifting the market to context ads that let publishers, not platforms, call the shots. As an added bonus, the law would stop Tiktok from spying on Americans, and also end Google, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft’s spying to boot:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/30/tik-tok-tow/#good-politics-for-electoral-victories

Mandating competition in app stores — as the Europeans are poised to do — would kill Google and Apple’s 30% “app store tax” — the percentage they rake off of every transaction from every app on Android and Ios. Drop that down to the 2–5% that the credit cards charge, and every media outlet’s revenue-per-subscriber would jump by 25%.

Add to that an end-to-end rule for tech giants requiring them to deliver updates from willing receivers to willing senders, so every newsletter you subscribed to would stay out of your spam folder and every post by every media company or creator you followed would show up in your feed:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/10/e2e/#the-censors-pen

That would make it impossible for tech giants to use the sleazy enshittification gambit of forcing creative workers and media companies to pay to “boost” their content (or pay $8/month for a blue tick) just to get it in front of the people who asked to see it:

https://doctorow.medium.com/twiddler-1b5c9690cce6

The point of enshittification is that it’s bad for everyone except the shareholders of tech monopolists. Jeremy’s Razors are bad, winning a 2.7 star rating out of five:

https://www.facebook.com/JeremysRazors/reviews

The company charges more for these substandard razors, and you are more likely to find out about them, because of targeted, behavioral ads. These ads starve media companies and creative workers and make social media and search results terrible.

A link tax is predicated on the idea that we need Big Tech to stay big, and to dribble a few crumbs for media companies, compromising their ability to report on their deep-pocketed beneficiaries, in a way that advantages the biggest media companies and leaves small, local and independent press in the cold.

By contrast, a privacy law, ad-tech breakups, app-store competition and end-to-end delivery would shatter the power of Big Tech and shift power to users, creative workers and media companies. These are solutions that don’t just keep working if Big Tech goes away — they actually hasten that demise! What’s more, they work just as well for big companies as they do for independents.

Whether you’re the New York Times or you’re an ex-Times reporter who’s quit your job and now crowdfunds to cover your local school board and town council meetings, shifting control and the share of income is will benefit you, whether or not Big Tech is still in the picture.

Have you ever wanted to say thank you for these posts? Here’s how you can: I’m kickstarting the audiobook for my next novel, a post-cyberpunk anti-finance finance thriller about Silicon Valley scams called Red Team Blues. Amazon’s Audible refuses to carry my audiobooks because they’re DRM free, but crowdfunding makes them possible.

Image: freeimageslive.co.uk (modified) http://www.freeimageslive.co.uk/free_stock_image/using-mobile-phone-jpg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

[Image ID: A man's hand holds a mobile phone. Its screen displays an Instagram ad. The ad has been replaced with a slice of a vintage comic book 'small ads' page.]

#pluralistic#ad-tech#ads#surveillance ads#commercial surveillance#behavioral ads#contextual ads#link taxes#platform economics#enshittification#instagram#julia angwin#end to end

471 notes

·

View notes